Stinkweed

The Failures of AmeriFlora ‘92

CeciliaBartter May 6th, 2024

Architecture of World Fairs // Professor Rugare

Table of Contents

I. Introduction

II. AmeriFlora as Exhibition Design Typology

III Failures of the Event

IV. Post-Event and Modern Context

V. Bibliography

I. Introduction

World exhibitions, beacons of modernity and pillars of progress. They bring prestige and thrill to a city, along with all the problems of capitalist modernity and ideals These exhibitions have continued to grow in scale and capital over the past two-hundred years, adapting to (or at least claiming to) the modern and increasingly technophilic world. America has hosted about eleven of these in total, with the last being held in New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1984[1] , a full 40 years ago. Though, is this really the entire story? In 1992, Columbus Ohio held its first and only international horticultural exhibition. This exhibition, known as AmeriFlora ‘92 (Or AmeriFlora) was to be held as a massive showcase of botanical art and design in celebration of the bimillennial anniversary of Columbus Voyage. Though today, it is most known as being a financial and cultural disaster, mostly forgotten to even residents of Columbus. Many issues arose during the six-month stint of festivities, including pushback from both indigenous and black communities, as well as lower than expected attendance causing massive fiscal loss. Things are not all doom and gloom, however, for all its faults, the showcase did bring about some lasting art and change for the surrounding area, creating public lands and better social equity of the direct community. While not in name and certainly not in pop culture, a “World Fair” AmeriFlora meets all the design criteria, and issues present, to be considered a global exhibition.

II. AmeriFlora as Exhibition Design Typology:

In order to consider AmeriFlora as having all the artistic and architectural elements of a World Fair, one must first understand what makes an exhibition in the first place Though much has changed visually in the course of these shows being held, many of the overarching themes have remained the same. Exhibitions are held to showcase industrial, scientific, and cultural items and developments in an edu-tainment setting[2] . It is also important to note that these global events require global participation, inviting numerous countries to celebrate and put forth their own accomplishments. Looking specifically at exhibitions around the end of the 20th century and into the 21st, much of the design language and theming became centered in an attempted biophilia and viewed from a sustainability lens (please not this paper is not about how implicitly ridiculous calling exhibitions “sustainable” is, this is simply the main theme they have adopted over the past few decades.) Art and architecture has become marketed as more about human connection to the environment and the state of said world[1] . It is from this that the connection can begin to be easily made between a sought-after “natural” exhibition and a horticultural one, a connection that only becomes stronger as the architecture and urban layout of AmeriFlora is examined.

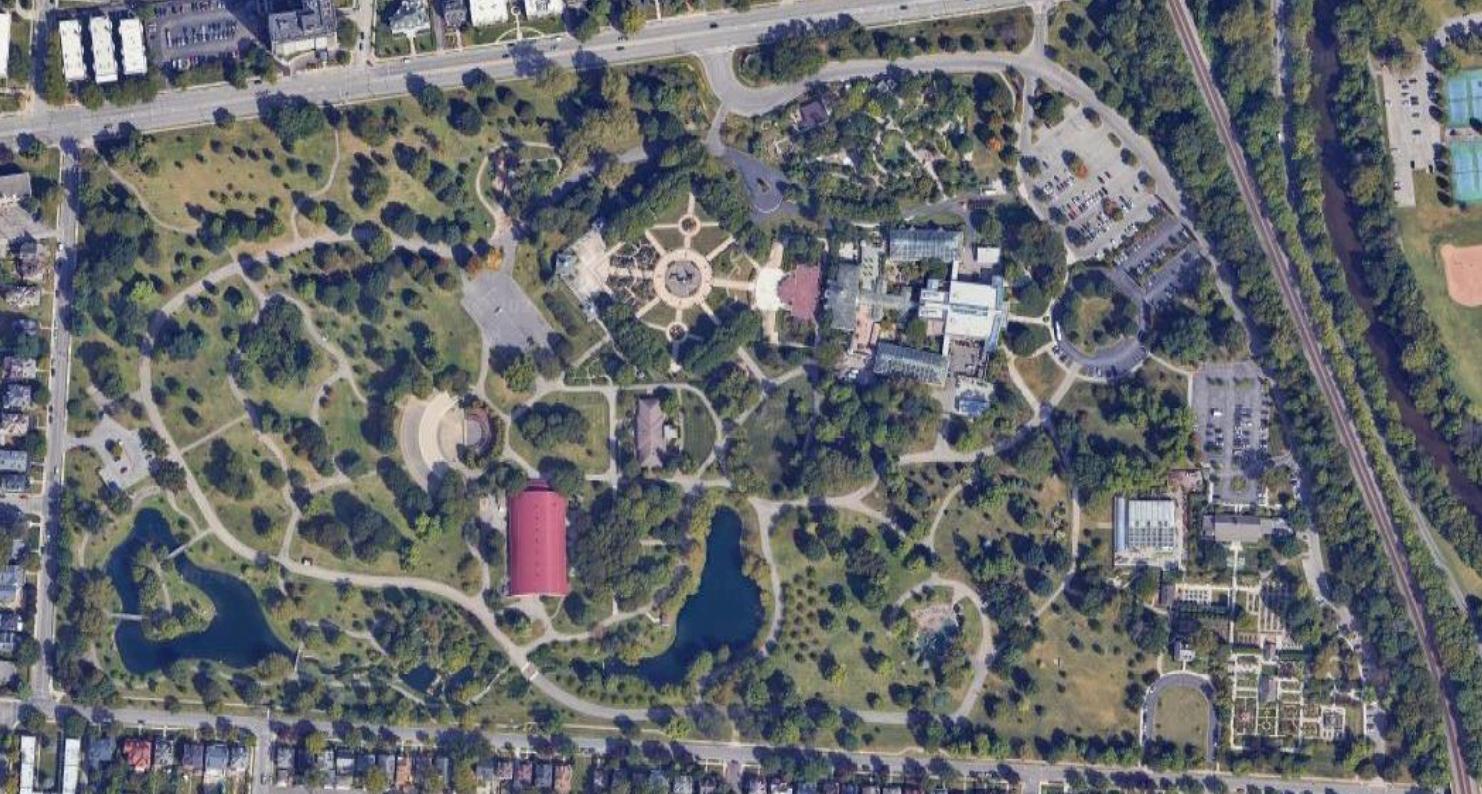

Though few maps of the grounds exist today, one can make some pretty good inferences about urban placement from the site today and from viewing the mass communal cataloging from visitors to the exhibition.

The roughly 90 acres of park was fully furnished by over 25 countries. Each who developed their own pavilions and exhibits, right beside contributions from various business, industry, and governmental pavilions[3] . In total contributions of all types of creative projects, around 50 countries total participated[4] . The then newly renovated Franklin Park Conservatory can be seen laid out axially from a central diamond-shaped courtyard in the center of the space, featuring a sculptural piece representing the three ships, Nina, Pinta, and Santa Maria which were used in the Columbian voyage. The main exhibition building, the Conservatory itself, is in a beaux arts victorian style, a very similar style to that adopted by early American fair planners[1] , albeit with more modern structure and an obvious greenhouse typology. Paths are also seen to be arranged in several districts, with a consumer shopping area, a world showcase, and even a food court[4] .

One man can be credited with the extravagance of the event, turning it from a flower show to (an attempted) global icon to recement Columbus’ place on the map. Scott Girard was invited to design the show after his previous twenty three years working closely with the Walt Disney Company as a landscape architect in Orlando, Florida. The designs he set out align very closely with both Disney parks and world exhibitions (unsurprisingly so as the two are very closely intertwined). Entertainment was priority number one, followed by food, and then clean restrooms. It was only after these “basic” needs were met that the general public would be open to education, in an entertaining way of course[5] . It is also quite exhibition-istic to have the end goal of exposing the general public to something of cultural significance, primarily bourgeois European values– how many Ohioans, or people for that matter, care about flowers? Evidently not many, seeing as the event made a negative profit.

Not even horticulturalists seemed to appreciate the extravance. Many said it was way too “Disney” in nature and most of the international pavilions were just, absolutely terrible. “Egypt had some temples and sand. Germany had a train set. The Chinese exhibit was filled with geraniums, and Italy featured five-foot pyramids in remembrance of the Aztecs” said Marco Polo Stufano, the horticultural director of Wave Hill[5] . There were also daily parades with more than 50,000 performers and an amphitheater featuring shows from big names like Dolly Parton and Boyz II Men[3] . Many of the gardens’ quality were also hit by a significant lack of sponsors and lack of care in general The United States

Agriculture Department even refused to lift its extensive ban on foreign-grown plants for the outside displays[5] , which was a major reason why so many of the “international” displays were so spare and americanized (though this could also be a metaphor for colonization and immigration). Many of the gardens also featured sponsor signage that would make even Venturi cringe. The massive scale of this strange project and the sheer extravagance of it all really bring into question who was this for.

III. Failures of the Event

Arguably the largest issue within the entire event was the fact it happened and how, as well as by extension who, it was marketed towards. Flower shows can be traced back to the 1830’s and victorian-age high society[6] They have a storied history in Europe but have held much less value in the United States. While it is certainly not uncommon for an exhibition to contain “subtle” themes of bourgeois high society “saving the common man” by exposing the masses to what was considered to be more high brow elements of modernity, it feels strange continuing to push those ideals into the new millennium. It is interesting to note that while looking at photos released of the event, the occupants are all white[7] In all fairness to the marketing of the event, this could be simply the pictures they chose to include but it still stands to reason that this was not an event for everyone. Most men can be seen in suits and ties, women in elegant dresses and colorful coats, clearly the majority of attendees were middle class and higher. This is accentuated by the fact that tickets for the event ran for about twenty dollars per person[3] (forty five dollars in 2024). AmeriFlora was very intentionally and clearly marketed towards upper middle class white Americans and Europeans

While the crowd is mostly white and over sixty five, before the exhibition commenced the park was primarily used by the large black and POC communities of Columbus’ East side. Members of the black community were outraged since they “felt like this was the only black thing that was ours… we have only one pass for the whole family ” Gloria McClendon, who owned a house in Franklin Park south[5] . In exchange for losing their only third-space, residents got landscape front yards. Theoretically, the loss of the park for a few months in the name of education should be a reasonable relinquish, especially if they were getting it back in better condition. However, the focus of the show quickly changed from education and horticulture to entertainment and profit-seeking. “The day I saw the show, I cried… I realized what a phony world

it had become. They took everything of true value and just destroyed it” said one resident[5] Barricading the park and forcing residents to pay to get in was seen by many as appropriation and gentrification alike. There was also confusion and outrage over the acquisition of the heavily used park space as opposed to investing to rehabilitate an existing urban wasteland like the penitentiary (which later became the now arena district). At the beginning there was an attempt for reparations by way of planned set-asides for minority contractors, however that was ruled unconstitutional by federal courts[5] . There was also significant native pushback, which was in no way helped by the prodding of the design board. The Sioux tribe was contacted to build teepees on the site[5] to supposedly celebrate the “founding of America”, yet the Sioux people did not live in teepees, but rather straw and willow bark shelters or large holes dug into hills and covered with stick roofs. Eventually, with enough prodding, An Iroquois from New York came and built a longhouse for the Native American Peoples’ Garden[5] . This garden was also considered to be the best one on site, featuring native plants There was also substantial pushback from native communities on the fact this was a celebration of the colonizing of america and genocide of millions of people, with several city and country-wide boycotts taking place. One of the only educational exhibits was a pared-down version of the Smithsonian’s “Seeds of Change” which focused a lot more on corn, potatoes, and sugarcane, than it did on the complete wipe-out of native populations and mass enslavement of African people. Over the past 28 years

there have also been several movements to remove the statue enshrining the voyage of conquest, yet it remains an abstractionist eyesore

Beyond racial and cultural insensitivity as well as poor design, even the weather was not on the side of the event. The summer of ‘92 was one of the wettest Columbus had ever experienced, with nearly half a foot falling on one day in July[8] . It is said the torrential downpours flooded goldfish out of the lagoons and killed many of the plants The expected stint of the program was two weeks of education but after profits had not been met and several sponsors pulled out, it was extended to six months of sensationalism and consumer frenzy. The financial performance caused pushback from residents who were dreading paying off city debt via taxing, especially after a similar event cost

residents $1.7 million only three years before[5] . At the time of closing, the event had only attracted about two million people, quite shy of the four million goal

In almost comically ridiculous fashion, when the event closed before Columbus Day of that year, many residents were in no mood to celebrate as old cultural wounds had reopened. There was even a moored slave ship recreation on the Scioto river – who on earth ever thought that was a good idea. The ship, which was removed in 2014, equally saw declining attendance over the years. Deconstruction of the site also took much longer than expected, extending far into the winter months and only opening back up in mid 1993[8] .

IV. Post Event and Modern Context

AmeriFlora was a failure, there is no question about it. Not only did it incur massive fiscal loss, but it also drew several scars in minority communities that continue to ache decades later Things are not all doom and bloom, however The design council did keep the promise of returning the much improved park to the community after the event. Franklin Park Conservatory reopened to the public on March 20th, 1993 and has become a central local spot ever since. The conservatory itself houses afterschool programs for the community, as well as hires locally for countless jobs ranging from botanical to educational. The newer infrastructure like power and water lines has also allowed the community to grow and thrive around it Last year in 2023, Columbus finished refurbishment of the old train station directly south of the park into a local cafeteria-style eatery (while this may sound like gentrification or acquisition it is important to note that all of the restaurants are local businesses to the area and all of the owners are people of color). AmeriFlora ‘92, while not in name, holds all the qualifications to be considered a world exposition, especially the backlash. While rather hated during the performance and shortly after, the architectural and urban changes caused by the mass renovation of the site greatly improved the surrounding community and even Columbus as a whole.

30 years later, AmeriFlora is not remembered as a disaster (though it was) but rather an unforgettable summer that brought about a beautiful park for the community of Franklin Park. Though it is interesting to note that typically the t community-forward architecture tends to come from a lack of buildings.

V. Bibliography

1 Findling, John E., and Kimberly D. Pelle. 2008. Encyclopedia of World's Fairs and Expositions. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc

2. Findling, John E. May 3, 2024. world’s fair. Encyclopedia Britannica

3. Hughes, Bill. March 22, 1992. Setting Sail to Discover Ohio’s AmeriFlora ‘92: The horticultural and floral exhibits celebrate America’s quincentennial. Los Angeles Times

4. Darbee, Jeff. August 24, 2020. City Quotient: The Legacy of AmeriFlora. Columbus Monthly

5 Raver, Anne August 6, 1992 GARDEN NOTEBOOK; AmeriFlora; An Odd Hybrid Struggles. The New York Times.

6. March, 2016. A Brief History of Flower Shows. New Forest & Hampshire County Show

7. Various Photographers. 1992, republished April 18, 2017. Remember AmeriFlora?. The Columbus Dispatch

8. Staff Writer. April 20, 2017. AmeriFlora was our ‘Seeds of Change’. The Columbus Dispatch