AWARENOW

THE WORLD'S OFFICIAL MAGAZINE FOR CAUSES

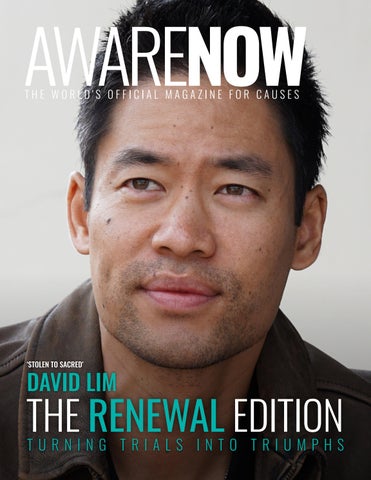

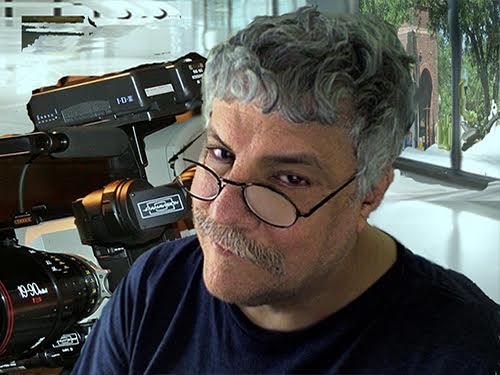

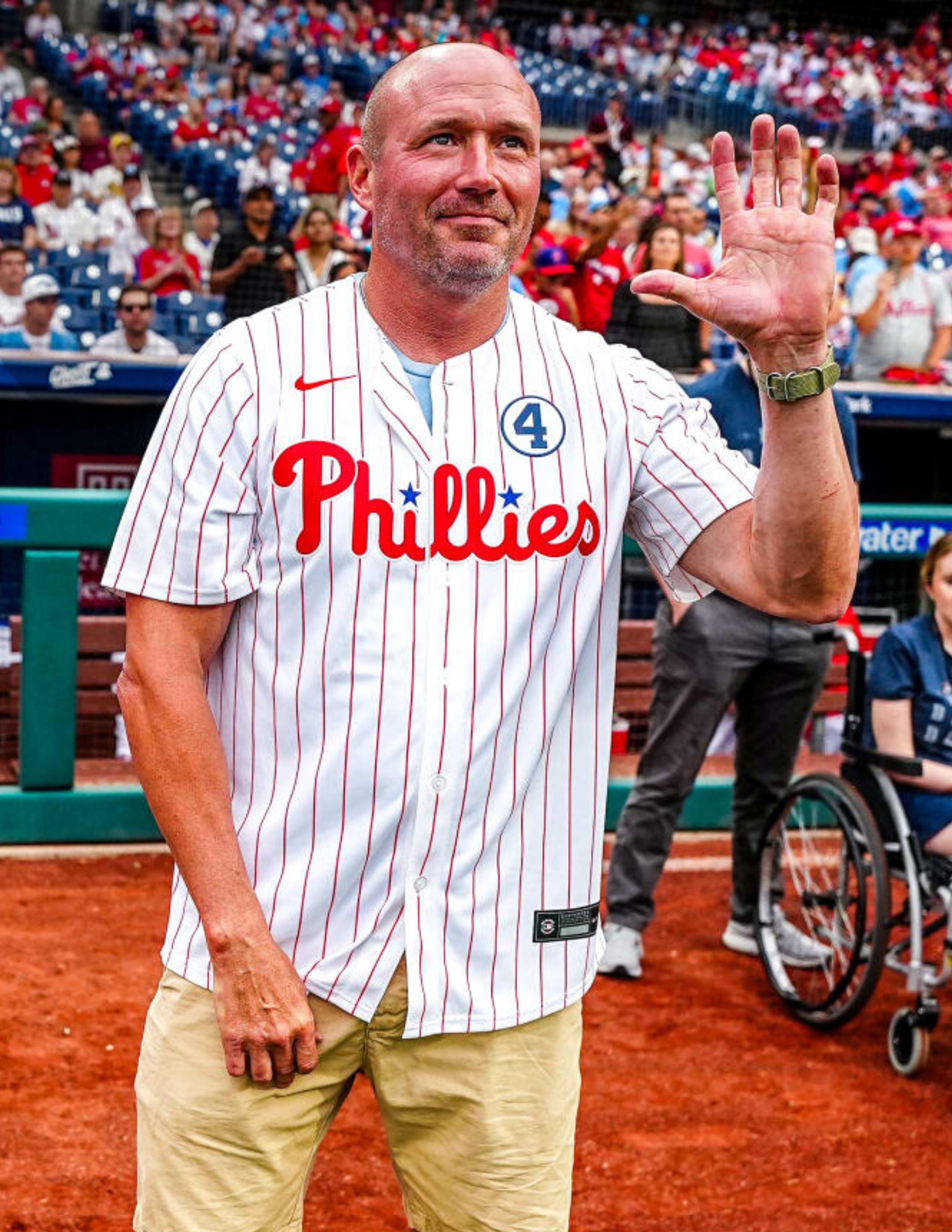

DAVID LIM

ON THE COVER: DAVID LIM PHOTO

BY: JONATHAN DAVINO

AwareNow Magazine is a monthly publication produced by AwareNow Media™, a storytelling platform dedicated to creating and sustaining positive social change with content that inspires and informs, while raising awareness for causes one story at a time.

IN PRAISE OF CHILDISH THINGS

BURT KEMPNER

THE GENTLE RHYTHM OF THE NIGHT

PAUL ROGERS

STOLEN TO SACRED

DAVID LIM

FROM DIAGNOSIS TO DISCOVERY

ASHLEY PIKE, PH.D. 7

ADAM

HEARTCHARGED, ERIN MACAULEY

STROKE OF MADNESS

MICHAEL & MATT STICK, NSSC

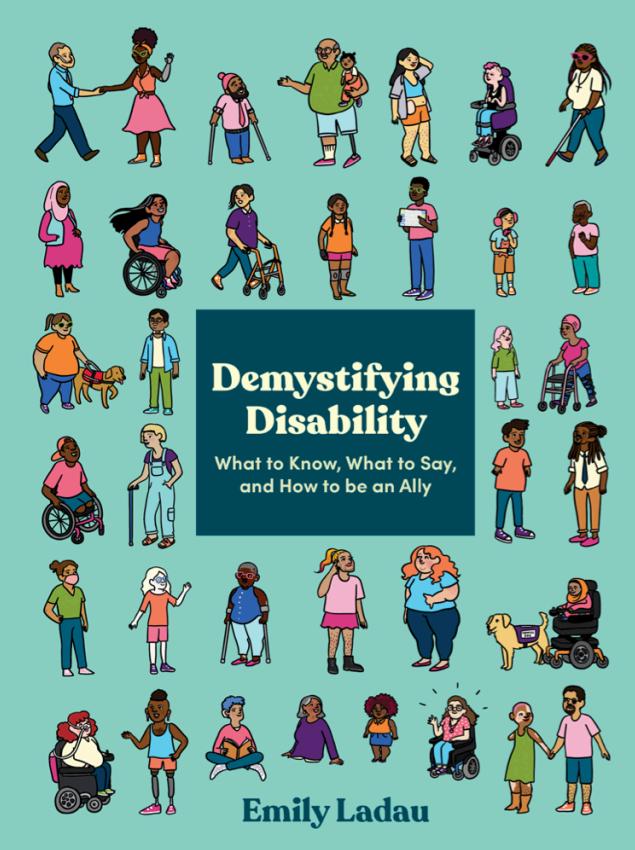

MORE THAN MEETS THE CHAIR

EMILY LADAU, CHANGE FOR BALANCE

RENEWING THE LOVE OF LEARNING

DR. REBECCA WINTHROP, SONJA MONTIEL

LUCILE MOREHOUSE, TANITH HARDING

MUSIC & RESILIENCE

ALLISON CHENG, GABY MONTIEL

THE PAGES THAT HELD ME

JACKIE GATES

AUTISM ISN’T THE ENEMY

DR. TODD BROWN

HEATHER CHERVENY

MIKE BROWN

ALEX SEARLE

renewal: (n.) the act of restoring, reviving, or becoming new once

To renew is not simply to begin again—it is to begin differently. It is the quiet revolution that takes place in the soul after the storm has passed, when we sift through what’s broken to find what still holds beauty, meaning, and truth. Renewal is born not in ease, but in aftermath. It is forged in fire, shaped by loss, and powered by an unwillingness to stay down.

In this edition of AwareNow, we explore the alchemy of adversity—the way sorrow can shape strength, and how struggle, when embraced, can become the seed of something greater. Featuring the extraordinary David Lim, whose life is a living testament to the ascent from limitation to liberation, we turn our focus to the human capacity to rebuild, reimagine, and rise.

When the world feels heavy and uncertain, choosing to hold hope is not naïve—it is necessary. It is an act of quiet defiance. Positivity, in times of turmoil, becomes a tool of transformation. Not blind optimism, but a clear-eyed decision to seek the good, speak the truth, and move with heart.

This issue is not about forgetting what we’ve endured. It’s about honoring it—and using it. Because the hardest roads often lead to the most luminous destinations. And those brave enough to walk them carry something sacred: a story that might just light the way for someone else.

May this edition be a reminder: the hardest chapters can lead to the most powerful stories. And when written with intention, courage, and hope—those stories change the world.

ALLIÉ McGUIRE

CEO & Co-Founder of AwareNow Media

Allié McGuire began her career as a performance poet, transitioned into digital storytelling as a wine personality, and later produced the Hollywood Film Festival. Now, as co-founder of AwareNow Media, she uses her platform to elevate voices and champion causes, connecting audiences to stories that inspire change.

JACK McGUIRE

President & Co-Founder of AwareNow Media

Jack McGuire’s career spans the Navy, hospitality, and producing the Hollywood Film Festival. Now, he co-leads AwareNow Media with Allié, focusing on powerful storytelling for worthy causes. His commitment to service fuels AwareNow’s mission to connect and inspire audiences.

The views and opinions expressed in AwareNow are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official Any content provided by our columnists or interviewees is of their opinion and not intended to malign any religion, ethnic group, political group, organization, company, or individual. Stories shared are not intended to vilify anyone or anything. Their intent is to make you think.

* Please note that you may find a spelling or punctuation error here or there, as our Editor-In-Chief has MS and lost vision in her right eye. That said, she still has perfect vision in her left and rocks it as best as she can.

It’s been lonely not being him.

BURT KEMPNER

WRITER & PRODUCER

“When I became a man, I put away childish things.” - 1 Corinthians

Why do so many of us abandon our playfulness as we grow older? Do the cares of the world grind us down? Is it the burden of responsibility and responsibility's frequent best friend: worry? Imagine taking the best aspects of our earlier years -- curiosity, daring, receptivity to the new -- and reintegrating them without the youthful baggage of impetuousness, self-centeredness and impatience. (Yes, sometimes my inner child could be an absolute brat.)

So how would this re-invigorated person act, think, feel, work, worship or, last but nowhere near least, play? I want to be that person. It’s been lonely not being him, I've been realizing how many good things from my youth I've let slip away and I'm trying to give them a loving welcome back. I may return to Never Never Land yet, even if I have to back in rather than fly over. ∎

Written and Narrated by Burt Kempner https://awarenow.us/podcast/in-praise-of-childish-things

BURT KEMPNER Writer & Producer www.awarenowmedia.com/burt-kempner

BURT KEMPNER is a writer-producer who has worked professionally in New York, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and Florida. His work has won numerous major awards, and has been seen by groups ranging in size from a national television audience in the United States to a half-dozen Maori chieftains in New Zealand. Spurred by his love for inspiring young people, he started writing children's books in 2015. Learn more about Burt and his books at his website: www.burtkempner.com.

Sometimes, beginning again is simply returning to the same place with more light, more love, and a little more of your true self.

PAUL S. ROGERS TRANSFORMATION

‘RELEASE

Release

why

Gina are halfway there.

Repetition is the heartbeat of life. An inaudible rhythm of eb and flow. It is stable and how we measure our lives. If we are fortunate, we get to see a great number of these cycles during our lifetime. We practice things over and over; walking, speaking, loving, forgiving, until they become part of who we are. Even when we feel stuck, repetition is doing its quiet work beneath the surface.

Think of a small seed. It doesn’t bloom overnight. It takes water, sunlight, time and yes, repetition. A little nourishment each day. The same simple actions, again and again. And then one day, almost without notice, something shifts. A green shoot. A beginning. A small renewal, born from steady care.

We are often impatient and want to see big changes in the form of sweeping moments of clarity and breakthroughs. But more often, these moments come in the slow turning of repetition. In showing up, again and again, even when it’s hard. In choosing kindness, patience or hope, just one more time. Renewal isn’t always about starting over; it’s about coming alive like the small seed. In the same place, but with new eyes and perspectives.

Renewal is a shift in mindset, a healing of the heart, a return to joy. It’s not always dramatic. It can be subtle, quiet, almost imperceptible. Renewal is not erasing the past; it’s building something new on its foundation. Renewal often comes through repetition. A person might repeat a daily walk and suddenly realize they feel lighter, more present. A writer may show up to the same blank page every morning until one day, a new idea takes flight. A relationship may go through the same conversations, the same struggles, until one day, there’s understanding. There is no specified time limit for renewal to happen.

In a very noisy world driven by the hunger of bigger and better, it takes the spaces between words, those silences, to appreciate the often underestimated power of small, repeated actions. It is the small things which actually are the big things. A quiet morning routine. A gratitude journal. A moment of mindfulness. A single kind word spoken every day. These aren’t grand gestures, but they accumulate and invite renewal.

Repetition gives us structure, and within that structure, we find space to grow. As a high school rugby coach, I use and run many drills to improve technique. This is done to build muscle memory, so when the time comes for action, the body already knows what to do and does not hesitate. In this case, repetition is deliberate and developmental. I constantly challenge our senior players to find some new nuances to the drill, which they can benefit from.

Similarly with our own lives. When we commit to a process or a practice, we often find that we aren’t just repeating; we’re evolving and renewing.

One of the most uplifting truths is that you can come back to the same place and be a different person. You can walk the same path, have the same conversation, do the same thing but from a place of growth, wisdom, or healing. You can read a book or listen to a song many times and suddenly find something new.

AwareNow Podcast

Written and Narrated by Paul Rogers

https://awarenow.us/podcast/the-gentle-rhythm-of-growth

“Be encouraged that you don’t have to start over to begin again.”

That’s the magic of the overlap between renewal and repetition. It tells us that we don’t have to constantly reinvent ourselves or escape our lives to find new meaning. Sometimes, what we need is already here. Sometimes, showing up again is the transformation.

Nature teaches us this truth. Trees lose their leaves each fall and grow them back in spring. Tides come in and go out. Birds migrate and return. And in these repeating patterns, there’s always renewal. Not one season is exactly the same. Not one sunrise is identical to the last.

We spend so much time resisting the flow of life. But if we just stop for a moment and allow ourselves to go with the flow, we will find new places we never even knew existed.

If your life feels repetitive, take heart. That repetition may be quietly preparing you for something new. And if you’re feeling the spark of renewal, nurture it with daily care, with small steps. Repetition isn’t the opposite of change; it’s the doorway to it. Renewal isn’t a complete restart, it’s a reawakening from within.

Be encouraged that you don’t have to start over to begin again. Sometimes, beginning again is simply returning to the same place with more light, more love, and a little more of your true self. ∎

PAUL S. ROGERS

Transformation Expert, Awareness Hellraiser & Public Speaker www.awarenowmedia.com/paul-rogers

PAUL S. ROGERS is a keynote public speaking coach, transformation expert, awareness hellraiser, life coach, Trauma TBI, CPTSD mentor, train crash and cancer survivor, public speaking coach, Podcast host “Release the Genie” & best-selling author. His journey has taken him from corporate leader to kitesurfer to teacher on a first nations reserve to today. Paul’s goal is to inspire others to find their true purpose and passion.

I still feel like I’m in the beginning

DAVID LIM ACTOR AND DESIGNER

Best known for his role as Officer Victor Tan on CBS’s S.W.A.T., David Lim is no stranger to action and intensity. But behind the scenes, a deeply personal journey began when a home burglary left him and his wife, Marketa, without the sentimental pieces that once told their story. Instead of replacing what was lost, they chose to create something new—launching a handcrafted jewelry line, Maya David, born of grief, love, and a desire to make beauty out of pain.

ALLIÉ: Let’s get started at the beginning of what is a rather new chapter for you. You and Marketa turned something heartbreaking—a burglary that took more than just things—into something beautiful with Maya David. Can you take me back to that moment when it happened and what it was like to lose not just the jewelry, but the memories those pieces held?

DAVID: I think that was definitely the toughest part. Obviously, when you experience a burglary or a break-in, your

DAVID LIM ACTOR AND DESIGNER

“This is going to tell my story… of resilience, of turning something heartbreaking into something beautiful.”

DAVID: (continued) that had so much sentimental value tied to them—family heirlooms, things we had gifted each other over the years for anniversaries, our wedding, things we had collected on our travels that reminded us of all the beautiful places we’d been.

So that was definitely the hardest part. It took us some time to process and grieve, but then it did shift. We just started asking ourselves, “Okay, what if we don’t replace these things—spend the money and just get new ones? What if we…”—and we started to get a little curious as well—“What if we don’t replace them? What if we teach ourselves how to make jewelry? What if we go down this path?”

That kind of curiosity, coupled with really wanting to turn this experience into something positive if we were able, led us to Maya David being born—hand-making our own jewelry. It was a way for us to heal. We enjoyed it, and we found meaning in it. That’s really how it all started.

ALLIÉ: Well, I think it's really beautiful because you took a situation where you were the victim and then became the victor. After that loss, to your point, instead of trying to replace what was stolen, you created something brand new. So, when did the shift happen from grief to creativity? Did you already know how to make jewelry? Or did this situation teach you something brand new?

DAVID: The latter—we had no idea how to make jewelry. We just knew that we loved it and had collected it over the years. Both my wife, Marketa, and I have always been creative. She’s been modeling and has lived all over the world practically her entire life. And me—being an actor—that’s another creative outlet, you know? Storytelling is artistic.

We had no clue—just as I had no clue when I became an actor, or before that, when I became a loan officer and didn’t know anything about mortgages. I think it’s just creativity and curiosity and taking on new challenges.

It really just started with that thought—that curiosity—and me hopping down to the local arts and crafts store, the local bead store, bringing home some supplies and materials and saying, “Hey, I don’t want to just spend money and replace these things. I want to make them. I want them to carry meaning. I want them to be more personal and more beautiful because I created them myself. This is going to tell my story… of resilience, of turning something heartbreaking into something beautiful.”

That’s how it all started. But no, we didn’t know anything about it. Self-taught. Learn as you go. Similar to my acting journey—you learn as you go and use all your resources. There are so many resources today with the internet and books where you can teach yourself anything you want to learn. I’ve always been open to that sort of thing—learning new things. And when you find something you’re passionate about and motivated by, you can really take it far.

ALLIÉ: I love that this is your theme. This is your through line, right? Like you said—when you started acting, you didn’t know. You just tried it. And you didn’t know anything about loans, but there you were—a loan officer.

DAVID LIM ACTOR AND DESIGNER

“It’s just about you and what you want to create… and how you want people to feel when they wear it.”

DAVID: Yeah. That’s the thing… We’ll see what’s next.

ALLIÉ: Well, I think it’s fantastic. Let’s talk more about this. Each piece in Maya David’s line is, as you said, handmade by you both, inspired by your travels and love for the natural world. Is there one piece, among the many, that holds the most meaning for you—something that tells a story that perhaps only the two of you know?

DAVID: That’s tough because, like I said, we want all of our pieces—everything we create that’s on our website—to carry some type of meaning or story. That’s why we made it. Either it reminded us of somewhere we’d visited, something that left a mark on us, a time in our lives, or just this journey of the burglary turning into a business.

But if I had to pick one, I’d probably say the very first bracelets I made. They were probably not done perfectly, but they were just simple black onyx bracelets. I made a his and a hers—one for myself and one for Marketa. And to us, that symbolized new beginnings. It represented a fresh start, a way to heal from the traumatic experience. And if you know your stones, onyx symbolizes protection, courage, and strength. These are all things we try to really infuse into our pieces.

ALLIÉ: That is beautiful. Now, let’s talk about Victor. While most people know you as Victor Tan on S.W.A.T., this jewelry line reveals a different side of you, David. One that’s perhaps slower, more intentional, more personal. How do these two parts of your life—the action part and the artistic—inform one another?

DAVID: I think, surprisingly, they’re not that different. Because with acting and jewelry design at the core, you’re telling a story. One is for the screen, and one is through your design—something that’s a wearable piece of art.

Obviously, one is action-packed, fast-paced, just like you said. And then when we get in the jewelry studio, it slows down. It’s therapeutic. It’s just about you and what you want to create with these materials and how you want people to feel when they wear it.

So, not as different as you might think—even though, at surface value, they seem like two very different things.

ALLIÉ: Right, right. One and the same, kind of. So, the fact of the matter is that you’ve worn many hats—engineer, model, actor, now designer. Through all of these roles, what is the one thing you’ve carried with you, no matter where life has taken you?

DAVID: I think that curiosity I mentioned earlier, but also, I’ve always—ever since I can remember—dreamt very big. I’ve always believed that anything is possible.

When I think back on my journey—getting a degree in engineering, one of the most challenging degrees—I can’t tell you how much time I spent in the lab while my friends were out partying. Then going from that degree to becoming a

DAVID LIM ACTOR AND DESIGNER

Exclusive Interview with David Lim https://awarenow.us/podcast/stolen-to-sacred

DAVID: (continued) loan officer, knowing nothing about mortgages, to deciding I wanted to become an actor—coming from a family with no artists or entertainers, being a shy kid—not knowing anything about getting into the entertainment industry. And now, to jewelry design.

But I always thought that if I worked hard and believed in myself, I could do it—or at least realize my potential in whatever outlet that was. Whether it was acting or jewelry design, something good would come of it. For me, it always came down to hard work, dedicating yourself, and making the necessary sacrifices to become successful at whatever you choose. That’s the common through line. So, when I give advice to other actors or friends, I say: you have to work hard, dedicate yourself to your craft—whatever that is—and believe in yourself.

ALLIÉ: I love that. And I love how, in all these different chapters of you, there’s that self-made, self-determined quality that carries through. So, I guess my final question for you—back to all these chapters, the story of you—what is it that you want people to take away from the story of you, David? From all the different hats and roles—if you had a gift to give someone, what piece of advice or part of your story do you hope shines through?

DAVID: Wow, that’s a great question—deep. And I think I’m still very early on in my career. I just turned 41. I have a lot of career and a lot of story left to tell. I still feel like I’m in the beginning chapter. Once I get to the middle and toward the end, I could probably answer that a little better. But I just hope to inspire others to chase their own dreams and believe that things that maybe don’t seem possible actually can be done. That’s how I felt when I became an actor—I didn’t know if it was even possible. I didn’t really see anybody who looked like me having success in this industry. Maybe now, that young version of myself can have someone who looks like him and think—or she can think —that this might be possible. Whether it’s acting or anything else. You want to be an entrepreneur, an engineer, a loan officer, a jewelry designer—whatever it is.

I heard something recently that really stuck with me: “You grow so that you can give.” And I’ve grown a lot—certainly over my eight-year journey on S.W.A.T., my 15 years in Los Angeles, and this shorter journey with Maya David. One day, I hope I can share the things I’ve learned—with my kids, with others, with people I don’t even know who may be watching or who are fans. ∎

ASHLEY PIKE, PH.D. POSTDOCTORAL

When science meets lived experience, something extraordinary happens. Ashley Pike is both subject and scientist—living with multiple sclerosis while actively researching it. Diagnosed in 2008, her path has taken her from the exam room to the research lab, where her curiosity and compassion converge. As a postdoctoral fellow in the UAMS Helen L. Porter and James T. Dyke Brain Imaging Research Center, Ashley explores the brain’s white matter not only through the lens of data but through the heart of personal insight. In this interview, she shares her journey from veterinary technician to neuroscientist, opening up about the mental fatigue of graduate school, the beauty hidden in brain scans, and the need to redefine what a “cure” for MS really means.

ALLIÉ: Let's just start at the beginning of you and your work with MS. Tell me about your relationship with MS.

ASHLEY: So, I live with MS. I was diagnosed in 2008—17 years ago now. I was working as a veterinary technician at the time. Even before my diagnosis, I was really into medicine. I’d spend time Googling, asking questions like, how can we stop pets from coming in for the same treatments over and over? How do we stop diabetes or kidney disease?

ASHLEY PIKE, PH.D.

“My current research looks at how changes in the brain from MS affect cognition over time.”

ASHLEY: (continued) Eventually, I realized I wanted to get to the root of things—I call it being preemptive. That curiosity led me into research. My first research job was in cardiovascular science. I cared for 40 pigs, seven days a week. I loved them—they were like my little children. After that, I worked in breast cancer research. When I got into graduate school for biomedical research, I connected with a professor doing MS research. We had a great conversation, and I thought hard about it. In vet medicine, we didn’t do much neuro work. If something got too complicated, we referred out. I didn’t know much about the brain or spinal cord.

But I live with MS. I thought this could be cool. So, I got into MS research and haven’t looked back. It’s been fulfilling to come into research and take on a role in advocacy and activism, too. That’s where I am now.

ALLIÉ: I think it’s fascinating that you live with MS and you're working on it from both sides. I really appreciate that.

ASHLEY: Before I got into research, many of my coworkers didn’t even know what MS was. I was often shunted aside or treated like I was inferior. It was a tough time. I believed I’d end up in a wheelchair and that I didn’t deserve much because of how others perceived me.

When I started grad school, I had a conversation with my professor where I admitted I didn’t know if I wanted to pursue academia. I wasn’t a traditional student. I’d been working in a clinic for ten years. I wasn’t in my twenties anymore. Academia is a long road, and I didn’t know how MS might affect me—especially before I even knew what mental fatigue was. I limited myself. But during grad school, I met incredible people who supported me. The narrative shifted from "you’re nothing because you have this disease" to "I commend you for researching a disease you live with." That full 360 was powerful. It brought me to tears. Being seen as an inspiration is still surreal to me, especially considering the trauma I carried.

When I look at MS research, I’m not trying to cure myself. I’m not even trying to understand why I have MS. I focus on helping others living with MS who may not have access to information or may be going through what I did. Knowledge is power. If we can empower people with tools to improve their quality of life while living with MS, then I feel that’s my role.

ALLIÉ: Let’s talk about the visual representation of your research. It’s equal parts brilliant and beautiful. I know it’s the output of your work, but can you share the story behind that visualization?

ASHLEY: You’re seeing the pretty parts of science… Science is mostly boring and emotionless. But here at our teaching hospital, we have an "Art from the Heart" initiative, where you can take your research and express it through art—poetry, sculpture, any medium.

My current research looks at how changes in the brain from MS affect cognition over time. I’m studying how specific white matter tracts predict long-term cognitive behavior. There’s an open-source program we use that recently added a new feature I’d been hoping for. It allowed me to map out different white matter tracts that make up a brain’s connectome and show how the brain compensates for damage.

One of the participants in my cohort—who I’m now close friends with—also has MS and works where I do. She’s also active in advocacy, and we often travel together to D.C. to meet with legislators, which is where I met you. I was inspired to feature her in this visualization. I used her favorite color, purple, with some orange to represent MS awareness. Each strand represents an axon, and the colors show different tracts associated with the cingulum bundle.

I want to understand how MS-related changes in the brain—beyond what’s visible in clinical imaging—lead to cognitive impairments. There are no effective treatments for cognitive impairment in MS. And more than half of MS patients on disability are there because of cognitive issues, not physical ones. That’s a red flag. My goal is to develop more individualized clinical approaches. MS isn’t linear; symptoms vary dramatically. A high-functioning patient may still struggle significantly, but if their neurologist compares them to someone worse off, their issues may be dismissed. I want to change that. We use the term "cure cycle" to describe treatment approaches, even though MS has no cure at this time. The goal is to improve quality of life. If we can do that, we’re doing something right.

ALLIÉ: I love this. As someone living with MS, I really feel the importance of what you’re doing. Let’s talk about that word —"compensatory." It’s fun to say, but it also holds a lot of meaning.

ASHLEY: Yes! Think of it like this: if you break your leg and need crutches, the crutches are compensatory. They’re not your legs, but they help you walk.

Or picture a road map. You’ve got three routes to work: the interstate, the highway, and the backroads. If the interstate is jammed and the backroads are flooded, you take the highway. If all three are blocked, you’re stuck. But if even one alternate route works, you can still get to work.

In MS, lesions block the brain’s "main roads." The brain reroutes signals through secondary pathways. These subservient tracks weren’t designed to take over, but they can fill in temporarily. That rerouting takes effort. So yes, it could explain mental fatigue. You’re using more of the brain to achieve the same function, and that requires more energy. More blood flow. More ATP. That’s something I’d love to study further.

ALLIÉ: That makes so much sense. Maybe that’s where fatigue kicks in—the brain is doing more work to compensate.

ASHLEY: Absolutely. Think of a new extension cord—tight, efficient wiring. Over time, if it gets bent or damaged, it has to use other wires. Less efficient. More energy is needed. That’s the brain on MS.

Exclusive Interview with Ashley Pike, Ph. D. https://awarenow.us/podcast/from-diagnosis-to-discovery

ASHLEY: (continued) When I started grad school, I didn’t even know what mental fatigue was. Now I feel it deeply. I come home completely exhausted. And sure, my work in veterinary medicine was hard, but this—this is another level of mental strain. It’s constant problem-solving. There’s no ‘done’. It’s like an eternal book club my husband says. And yes, we know fatigue, depression, and mood can impact cognition. But I think the way the brain compensates could also be a contributing factor. It’s a question worth answering.

ALLIÉ: Definitely. You’re doing brilliant and beautiful work. For me, when I was first diagnosed, my neurologist, Dr. Robert Pace, helped shift my fear into fascination. Maybe it’s a coping mechanism, but being curious about MS helped me face it. Do you feel that way too?

ASHLEY: Honestly, my fascination started before my diagnosis. In vet tech school, I loved learning about white blood cells and the immune system. I geeked out over virology—like how the influenza virus changes to survive. That blew my mind. I think that fascination helped me separate emotion from science. In the clinic, I was compassionate, of course. But when a dog came in after being hit by a car, I focused on stabilizing vitals, not the trauma. That mindset helped me in research.

With MS, I don’t sit around thinking, "Wow, this is so cool." I see it every day. I focus on how we stop it. Friends often ask, "Are you working on the cure?" And I say, no. I used to feel bad about that, but I’ve made peace with it. There are brilliant people working on a cure. I focus on improving quality of life now. Because even if a cure comes tomorrow, it won’t give people back what they’ve lost.

Everyone’s path is different. For one person, a ‘cure’ might be returning to work. For another, it’s being seen and supported by their community. Reducing stress, feeling heard—these things matter. Less stress means less disease burden. It’s all connected.

ALLIÉ: Yes, interconnected—that’s the word. All these systems play off each other. I love that you’re redefining the concept of a cure. It’s not one-size-fits-all.

ASHLEY: Exactly. A global cure would be amazing—no one else getting diagnosed. But we still have millions living with MS now. And many are suffering. Healthcare has changed. Appointments are shorter. Patients with chronic illness need to be heard. Not just for emotional support, but to feel seen. People living with MS aren’t seeking attention—they’re seeking connection.

If one person can feel less alone because of what we share, that’s powerful. We’re not looking for sympathy. We’re looking for a path forward. Together. ∎

1. Your presence gives others strength.

Someone feels stronger because they saw you out there - doing life your way.

2. You help people feel less alone.

You’ve been someone’s quiet comfort, even when you had no idea. in the way you listen. In the way your presence softens a room.

3. You inspire without trying.

Through your patience, your presence, your quiet power - you lift others. You’ve said things they still think about.

4. You prove it’s possible.

You think you’re just getting through the day. But to someone else, you’re proof that strength & dignity can look like this.

5. You shift perspectives.

Not because people feel lucky to walk when you can’t, but because seeing you move, live, smile, speak your mindmakes them question the limits they’ve placed on their own life.

6. Someone feels safer when you’re near.

7. You’re not a burden.

You are more special than you realize. There are others who think so much more of you than you think of yourself! People wish for your company more than you think they do. ∎

When it comes to living with Type 1 diabetes, Laura Pavlakovich knows the weight it carries—not just physically, but emotionally. A Southern California native diagnosed as a child, Laura spent years hiding her devices, her diagnosis, and parts of herself just to feel “normal.” But in the face of isolation, she created connection. As the founder of You’re Just My Type, Laura is redefining what support looks like—leading with honesty, empathy, and a whole lot of heart.

ALLIÉ: Let's begin by your beginning. You grew up in Southern California, a beach girl diagnosed with type 1 diabetes as a kid. Can you take me back to that time? What do you remember most about the early days of navigating a diagnosis that I imagine would change your life?

LAURA: Yeah, it's so crazy, right? Because when you're five years old, you have no idea that what just happened to

Of course, I couldn’t grasp

LAURA PAVLAKOVICH FOUNDER OF YOU’RE JUST MY TYPE

“All of a sudden, I was that girl. Yeah, I was the ‘diabetic girl’. It was awful.”

LAURA: (continued) Everything I know has been told to me by my mom, but the symptoms of type 1 diabetes are all pretty textbook: frequent urination, rapid weight loss, and extreme thirst. My mom said we would walk to school together every day, and one day, she noticed that I could no longer walk up this small hill we always climbed—I was getting too weak. That was the first thing that made her think, What is going on? This is so weird. Then I started wetting the bed, and she thought, This is also very strange. She knew something was wrong. She had no idea what it was, but she knew I was getting sick and got really scared.

She took me to my pediatrician—this was back in 1996, when things were so different. Thank God she took me when she did. The pediatrician said she would do a fasting blood test and told my mom to take me home, not give me any food or water for 12 hours, and bring me back the next day.

Most people don’t know this, but before you’re diagnosed with type 1, your blood sugar is extremely high because your body isn’t producing any insulin. That’s why you're so thirsty all the time. My mom told me I was screaming bloody murder because I needed something to drink, and I was starving. But the doctor had told her she couldn’t give me anything.

So she brought me back the next day. They did the blood test, and my pediatrician came out and said, “Your daughter has type 1 diabetes. Drive straight to Children’s Hospital. There’s a team of specialists waiting for you.”

Now, of course, we all know you can take a blood sugar reading with a meter in five seconds. Literally—five seconds. So, all of that felt very unnecessary. I feel worse for my mom, having to go through that. But I have this really distinct memory of being in the hospital, playing with a Hello Kitty toy, and looking up while my mom was on the phone with my dad, hysterical, telling him I had this diagnosis. I remember thinking, “Something really bad is happening.”

I was in kindergarten at the time, and everything changed. I went to a really small private school. We didn’t have a school nurse, but my mom would come to school every day at lunchtime to test my blood sugar and give me a shot. Suddenly, I had to bring a lunchbox packed with Post-it notes on every single food item listing how many carbohydrates each one had. I got to have snacks throughout the day that other kids didn’t get to have. And I knew I was different.

Of course, I couldn’t grasp the full scope of the disease, but I became ‘the different one’. I was the only kid with it. So, all of a sudden, I was that girl. Yeah, I was the ‘diabetic girl’. It was awful.

ALLIÉ: So every day, she would come and give you a shot at school. Every day from your diagnosis on, you've had to calculate everything that goes into your body. That's a lot of math to do constantly.

LAURA: And I hate math. But we lived really close by. And again, we were so fortunate because she had a job that allowed her to do this. Otherwise, I don't know what we would have done without having a nurse there.

I maybe would have had to switch schools, but she said she knew I learned pretty quickly what I needed to do. One day, my mom called the school and she's like, “I'm gonna be right around the corner, but just let's try something. When Laura comes in today for me to test her blood sugar, just tell her that I can't make it and see what she does.” And she said, “If you need me, I'll be right here. I just really wanna see.” And so I came in and they said, “Your mom can't make it.” And I was like, “Okay.” And I took the thing, tested my own blood sugar, got a shot and from probably around the same year I was diagnosed or the following, I kind of just took over with the physical stuff.

“I don’t have the energy to explain it to all of these new faces.”

ALLIÉ: I just can't… back to that part of the story you shared about that terrible 12-hour fasting test, I cannot imagine my child screaming because they’re thirsty. And to think that things have changed for the better, but not probably enough.

LAURA: A lot of parents think their kids don’t have type 1 diabetes but rather symptoms that sound a lot like flu symptoms. So, parents give their kids liquids like 7-Up or drinks with electrolytes like Gatorade, but these things that are raising their blood sugar so high and causing them to be in way worse shape by the time of diagnosis. It’s never easy for the parents.

ALLIÉ: Let's fast forward to a moment here. Because you've shared that in high school, someone actually ripped off your insulin pump, not knowing what it was?! I can only imagine that moment. I mean, some scars are visible, but this must be an invisible scar for you. Can you walk me through that experience? Bring me back to that moment.

LAURA: It's so interesting because that memory was blocked in my head for a long time, and it actually took a lot of therapy for me to remember that happening.

So, I was put on an insulin pump when I was really young, kindergarten or first grade. That was like my life. I had my insulin pump on me at all times. Then when I went to high school, I switched from a really tiny private school where everyone knew me to a huge public high school with 2,200 kids. I think only four of us at that entire high school had diabetes. Back then, insulin pumps looked like pagers. This was still in the early 2000s. They had a long tube connected to a reservoir of insulin into an infusion set in your body. There you have a little cannula inside your body. Well, someone just came up thinking it was a pager and they're like what's that and they took the pump off my pocket and the site ripped out of me.

Again, I blocked it out of my memory because it was so traumatizing. When that happened, I honestly don't remember the exact moment, but I went home and I told my mom, “I'm getting off the pump right now.” I was 14-years-old, and I said, “I don't want this anymore. I don't want people to see it on me. I don't want them to ask me questions…” I'm getting emotional just talking about it. I was like, “I just don't want to be that girl. I've been that girl this whole time. I finally got to a good place at that school. I don't have the energy to explain it to all of these new faces.” And that just put this little sense of I guess we can say shame. I would hang out with new friends and unhook my insulin pump before we'd hang out, which is a very dangerous and terrible thing to do because that's what's giving you insulin throughout the day. I remember I would unhook it and then be like, “Okay, I'm normal right now.” I got to hang out with my friends, and I'd have nothing visible on me for them to know. Of course, I'd get really sick because my blood sugar would be so high without insulin.

ALLIÉ: But being sick was worth it to you at that age, just so you could fit in. Yeah?

LAURA: A hundred percent.

ALLIÉ: Those are big things to deal with. So, you talk about the emotional toll of diabetes sometimes being even harder than the physical part. Can you just talk me through that?

LAURA: When people think of diabetes, first of all, there's a lot of misinformation. There's a lot of stigma. There's type 1, there's type 2, and there's a million types in between that also people don't know about. And when people think of it, in my opinion, it's like, “Numbers, oh, you have to count your carbs. It's a lot of food counting, and it's shots.” And I wish that's all it was.

LAURA PAVLAKOVICH FOUNDER OF YOU’RE JUST MY TYPE

“Diabetes is one of the most expensive diseases to live with. Insulin is the eighth most expensive liquid in the world.”

LAURA: (continued) I have this new metaphor of how to describe what it's like having type one diabetes. And I'm sure this is similar for a lot of people with chronic illnesses. But when I was trying to process, I would get in these really depressive spirals when I would think about having diabetes for the rest of my life. And the way I could finally put it into words is that it felt like I was dropped into the deep end of an ocean. And the only way to survive is by treading water through your hands and legs the whole time, but there's no shore. So you're not swimming to somewhere you can ever rest. You're just treading so you don't die. And if you stop, you drown… You can't stop. And people can swim by you and think you're fine because they think you're swimming (not treading). “Look at her! She’s having this great time.” But you can't rest, and you can't really explain. It's hard to understand unless you've lived it. It's so invisible. And people only think it's easy because us as a type one community, we make it look so easy as we walk around unintentionally hiding the actual burden.

So yes, I have to count every single carbohydrate that goes into my body. I have to test my blood sugar throughout the day. I have to take an insulin injection every single time I eat. Every time my blood sugar goes low, I have to eat sugar. If I exercise, I have to plan for that, too. It’s like a video game where the stakes are your life—too much insulin can kill you, not enough can kill you. And I’m the one who has to make that call. We’re not doctors. Kids aren’t doctors. It’s a wild disease.

And I don’t think people really understand the scope of it. It’s hard to ask for help. And it’s nearly impossible not to feel like a burden. I think every single type 1 I’ve met shares that same feeling. You’re on a hike with friends and suddenly have to say, “We need to stop right now—my blood sugar’s low.” Or you’re at work, in a meeting, and you’re seeing double because of your blood sugar. I went to a comedy show the other night where they made everyone lock up their phones, and I had to have a whole conversation with the staff explaining that I can’t be separated from mine—it tells me my blood sugar in real time.

On top of all that, we have to be our own advocates with insurance companies. Diabetes is one of the most expensive diseases to live with. Insulin is the eighth most expensive liquid in the world. So we’re already fighting mentally, emotionally, physically—and then we have to fight the doctors, the insurers, and big pharma just to afford the medication that keeps us alive. It’s a layered mental prison.

Over time, I think I got really good at dissociating. I’d tell myself: just don’t think about it. You can’t think about it. It’s day by day—get through today, then tomorrow. But my weak point is this thought I keep coming back to: I’ve already had this for 30 years… and there’s no end in sight.

You go to get a massage to relax, and you’re wondering if your phone’s going to beep during it—do you turn it off and risk not waking up if you go low? Massages can make your blood sugar drop. You go on vacation and it’s all new food —new carb counts you don’t know, possibly a new language, time zone shifts. You have to change settings.

It’s a disease you cannot escape. You don’t get a break. It’s relentless. And no one knows, because we’re walking around with these little devices on us—and to everyone else, we look fine. But it’s hard to understand what it really takes.

ALLIÉ: I hear you 100%. It’s different for me—because I don’t have diabetes—but I do have multiple sclerosis. And to your point, I loved the metaphor you used. People see you in the middle of the ocean swimming and think, “Oh, she’s having a great time.” But they don’t know you’re just trying to survive.

ALLIÉ: (continued) So, Laura—when was the moment that shifted things for you? When did you realize that the mental health side of this needs to be part of the conversation, and that you wanted to do something about it?

LAURA: After high school, I went to this photojournalism program that focused on injustice and poverty. It was volunteer work in developing countries, and I was really young—just 17. It was life-changing. I came home to Redondo Beach with this moral obligation to change the world. But I felt lost. I wanted to photograph something meaningful. People were like, “Take photos of the ocean or dolphins,” and I remember thinking, this isn't it. But nothing about diabetes crossed my mind at that point.

Then in 2016, I was at a wedding talking to the photographer, a mom who barely knew me. She started telling me about her four-year-old son who was just diagnosed with type 1. She said he cried himself to sleep at night because he felt like he was the only person in the world with it. She told me, “I can only show him computer statistics so many times before it stops meaning anything.”

And I swear, in that moment, it clicked: this is it. I’m going to take photos of people with type 1 and share their stories. I wanted to give that little boy a book of faces instead of stats. Real people, not just numbers. That’s how You’re Just My Type began.

It started small. I was nannying and working in restaurants, but I started calling up my friends from diabetes camp and asking if I could take their photos. My mom had created a support group called the South Bay Hot Shots, so I had connections to people with type 1. I always had these little glimpses of belonging, but they were fleeting. You’d see your camp friends for a week, then not again for another year.

We started interviewing people. We asked the same set of questions: “What mental health advice would you give?” “What’s something you thought you couldn’t do with type 1, but you proved yourself wrong?” It built this beautiful, healing community. Then COVID hit, and I couldn’t photograph people in person anymore, so I put out a Google Form: Send in your photo and your story from wherever you are. And we blew up. People from Finland, Bangladesh, India, China— stories from all over the world. Tens of thousands of followers.

“That’s what this community is… It’s a place to breathe.”

LAURA: (continued) In 2021, my nanny job ended and I was completely burnt out. Drowning, honestly. But I had this wild idea: what if we did an in-person event? Everyone said, “Laura, what are you thinking? It’s COVID, everything is canceled.” But I just knew. People needed this now more than ever. So we hosted our first event for young girls with type 1—ages 8 to 17. Every volunteer was a woman with type 1. We had a behavioral therapist, a social worker, a yoga instructor, a nutritionist, an artist… all with type 1. It was like a mini mental health summit.

It was beautiful. Afterward, I thought maybe this would just be for young girls. But the community said, “No, no. We all need this.” Adults, boys, older generations—everyone. So we kept going. Now, we call these gatherings “life rafts.” When you find someone who gets it—even just one person—it changes everything. You don’t have to attend a big event. You don’t need 40 other people in the room. One person who truly understands is enough to help you catch your breath.

That’s what this community is… It’s a place to breathe. A place to rest your limbs after all that treading water. And then start again, with just a little more strength than you had before.

ALLIÉ: And I love how you said a moment ago—how the project started with photos so people could actually see it. This is what it looks like. This is what I look like. For that little boy, it wasn’t about numbers. It was about seeing faces.

LAURA: Exactly. Not just statistics—we're real. And we're everywhere.

ALLIÉ: So, I guess my last question is this: you've created such an incredible space where people now truly feel seen and understood. Is there a single moment—or maybe a story—that makes you sit back and think, this is why I do this?

LAURA: My number one was during one of our toddler-specific events.

Exclusive Interview with Laura Pavlakovich https://awarenow.us/podcast/just-my-type

LAURA: (continued) We started hosting events for type 1 toddlers, but really, they were for the parents. These parents are suffering. They need to be around other parents who are going through the same thing to feel the same kind of relief we get. The kids? They’re just two, three, four years old—they don’t fully understand what’s going on yet. We’d rent out a little gym or play space so the kids could just run around. We’ve been doing them for a few years now, and I think it was in the second year that this moment happened. Two little girls were on the same monkey bars, and I noticed they had their devices in the same spots. I thought it was just too cute, so I started filming them. One of the girls is swinging, and mid-swing, she looks over and sees the other girl’s insulin pump. She just stops. She drops down, runs over to me and says, “That girl has diabetes—just like me.” She was emotional. I looked at her and said, “They all have diabetes. Just like you.” And in that moment, I realized: this is for them now. These kids are going to grow up in a world where they’ve never been the only one. They’ve never been “the different kid.” They’ve had 15 or 20 other kids who go to events with them every few months. They'll grow up never feeling alone. I can’t believe I got that moment on camera. It chokes me up every single time.

Another moment that stands out: we have adults who come to our events completely alone. They’ve never met another person with type 1 in real life. They show up bravely, all by themselves, not knowing anyone. At one of our events in downtown L.A., I saw this guy walk in—I’d never met him before. He walked into the room, looked around at everyone… and he saw. He saw the pumps, the CGMs, the sites. It’s L.A., so a lot of people are in tank tops and t-shirts. You can see everything. I walked up quietly, introduced myself, and he looked at me and said, “Everyone here has type 1?” I nodded. “Everyone here has type 1.” And I watched him exhale for the first time. Because until you experience that kind of community, it’s like you’ve been speaking a language no one else understands. Then, suddenly, you’re in a room where everyone speaks it. They get you. No explanation needed. And the relief that comes with that—it’s massive.

ALLIÉ: Yes. What you’re saying—it's just as true for adults as it is for kids. We all have this deep need to be seen and understood. I’ve had conversations like this within the MS community. When I’m with others who have it, I don’t have to explain anything. And that’s such a gift—because explaining is exhausting. To just be… in a space with people who get it… that’s everything. Community really is everything. Your people—your people—are everything.

LAURA: Exactly. Community is everything. We all just want to belong. Every human being is searching for that— somewhere we belong. That’s something we take really seriously at You’re Just My Type. Because even within the type 1 community, it can still feel hard to find your place. Some groups feel exclusive. You might not see yourself represented. So for us, it’s simple: your diagnosis is your ticket in. It doesn’t matter your age, your race, your gender, your sexuality— none of that matters. If you have type 1, you belong here. No questions asked. No explanations needed. That’s what we want to give people. A place where they don’t just feel seen—they are seen. Always. ∎

ADAM POWELL

EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW WITH ADAM POWELL

Living with MS means carrying a weight most people can’t see—and finding the strength to move forward anyway. For Adam Powell, that strength isn’t just in surviving; it’s in creating a life that speaks louder than the diagnosis. As someone who shares this journey, I sat down with Adam for an honest conversation about what it means to live fully when every day brings new challenges. Together, we talk about adversity, advocacy, and the choice to stand tall when it would be easier to fall. As my sister says, “I’m not dying with MS. I’m living with it.” And Adam is living proof of what that can look like.

ALLIÉ: Because it’s a good place to start, let’s go back to the beginning of your life with MS. Please share the story of your diagnosis day.

ADAM: All right, so I officially got diagnosed on June 17, 2019. But the very first symptoms I had weren’t like most people who say, “I’ve had MS for 15, 20 years.” That wasn’t the case for me. My first symptoms showed up around October of 2018. I was working for UPS in Columbus, helping open a new building. I had just bought new boots, and

When I got diagnosed, I could still walk… but within five months I was in a wheelchair.

ADAM POWELL MS WARRIOR & ADVOCATE

“My first MRI showed over 30 lesions in my brain and more than a dozen on my spine and neck.”

ADAM: (continued) Then came Christmas, which at UPS is absolutely insane, as I’m sure you know. I’d come home from work and feel like my legs were cold, numb, and just... off. But again, I told myself, “Of course they do. I’ve been outside in the cold for 12 hours.” So, I wrote that off too.

Then Christmas Eve comes along. I’m at my sister’s place, and suddenly I get this awful groin and lower back pain. I could barely walk for three days. I remember she gave me a TV, and it sat in my car for three days because I couldn’t carry it up the stairs to my apartment. That’s when I thought, “Something is wrong.”

I actually went to the doctor, which is rare for me—I’m not a big doctor guy. The doctor thought it was a hernia and referred me to a specialist. So I went. The specialist said it wasn’t a regular hernia, but a “sports hernia,” which to this day I still don’t fully understand. He sent me to physical therapy. The therapy helped—my groin and back pain got better. The therapist thought it might be a pinched nerve from all the physical labor I’d done over the years. That kind of made sense... except usually that kind of nerve pain only affects one leg. Mine was in both.

At work, I started noticing I needed to touch things more to keep my balance. My legs felt heavy. At therapy, I kept asking, “Why can’t I balance on this board anymore?” I could always do that. By April, the therapist said, “I think you should see a neurologist.” And I was like, “Why?” I didn’t know anything about MS. I didn’t know anyone with MS. She said she thought I might have it, and I was like, “Oh. Okay… What’s that?”

So I saw a neurologist. Within two months, I had a diagnosis: primary progressive MS. Just like that. It was fast. I was taken off work immediately. I had been with UPS for 12 years, and just like that—I was done.

ALLIÉ: That’s wild. I mean, me myself living with relapsing remitting MS, it started small. But for you, it was just all in —right away.

ADAM: It was a very hard pill to swallow, especially because I didn’t know anything about MS. I had to Google it just to figure out what it even was. But reading the definition online doesn’t really explain it—it’s different for all of us. My first MRI showed over 30 lesions in my brain and more than a dozen on my spine and neck.

ALLIÉ: Oh my gosh.

ADAM: Yeah. What I’ve since learned is that those lesions take months to form—so clearly I’d had MS for a while, but it had been dormant. Then in October, I lost my best friend—basically my brother. That stress just unlocked something. After that, it all went downhill.

ALLIÉ: And the fact that you had noticed things… but just kept writing them off…

ADAM: Exactly. That was October. By December, I was finally going to the doctor. So it wasn’t a long timeline. When I got diagnosed, I could still walk, just not for long distances. But within five months I was in a wheelchair. That quickly.

“I mean, I lost everything. My career, my ability to play sports, my independence. I couldn’t walk.”

ADAM: (continued) I’d never missed work before. That just wasn’t me. So I didn’t understand how disability worked. I was trying to figure out what to do with my time, but also—do I still have my benefits? How am I going to get paid?

So in November, I tried logging into the UPS benefits portal, and it wouldn’t let me in. I was using the same password. I didn’t get it. So I called and they said, “Oh yeah, you can’t access it because you don’t have insurance. You haven’t had insurance since October 11.”

So over a month before, I had lost my insurance—and I didn’t even know it.

ALLIÉ: What must have been going through your mind? Here you are, losing your ability to walk...

ADAM: Well, I hadn’t lost it yet. But that’s what made me lose it. I didn’t know what stress could do. I didn’t know anything about MS. I didn’t realize how bad stress could be. But I spent hours every day on the phone trying to fix it. It took about a month. Between my employer, the insurance company, and my doctors, it was a mess.

It turned out my first neurologist—who was terrible—had taken me off work, but he kept telling the insurance company I was fine. So from their side, they were like, “Why isn’t he working then?” Meanwhile, I’m being told I can’t work. It was a mess. I lost my insurance, couldn’t get Ocrevus—which at the time was the only approved drug for primary progressive MS—and couldn’t get my next MRIs. Eventually, I switched doctors, but the old guy kept coming back to haunt me. By the time it all got sorted, I had gone from using a cane to needing a wheelchair. It all happened so fast.

ALLIÉ: You moved through those stages so quickly.

ADAM: Yeah.

ALLIÉ: You’ve said that MS has changed everything—but also, somehow, nothing. I love that. I want to hear more. What have you lost with MS—and what have you found?

ADAM: I mean, I lost everything. My career, my ability to play sports, my independence. I couldn’t walk. I was 37—in the prime of my life. I loved working, going to concerts, partying, playing sports… and suddenly it was all gone. Just disappeared. I had to cope with that. But over time, MS opened my eyes. It changed how I see the world. It forced me to slow down and really see things. I stopped taking life for granted.

Once I was finally able to drive again, I went on a cross-country road trip. I visited seven national parks. I met up with other people living with MS along the way. That’s something I never would have done when I was still working. I would’ve taken a week off, maybe gotten some tattoos, gone to a few concerts, then gone right back to work. But MS slowed me down—and gave me a new perspective.

ALLIÉ: The curse... and the blessing at the same time.

“I’d rather deal with pain and walk, than be pain-free and unable to move.”

ADAM: Exactly. But it was a tough road. After the insurance debacle, I finally got back into physical therapy. I had stopped driving because I didn’t trust my feet. Driving was my job—I knew I couldn’t do it anymore. So I tried getting hand controls put in my car. Things were going okay for a while…

Then March 2020 hit. COVID shut the world down. I couldn’t leave my house for four months. I couldn’t walk, couldn’t drive—and honestly, I was terrified. I had this new disease. I was on an immunosuppressant drug. I didn’t know what would happen if I got COVID. So I stayed home.

Those four months were the darkest, most depressing time of my life. I was grieving what my life used to be, questioning if it could ever be anything again. And it’s messed up to say, but during that time, I had to consciously kill my old self—grieve the version of me that was gone—and start over. That’s what I did.

When things opened up again, I hit PT hard. I told myself, “I’m not the guy in the wheelchair. I will do everything I can to get out of it and stand on my own two feet again.” And I did. I still do. Every day.

ALLIÉ: That’s the constant reminder we give ourselves. It’s the MS warrior mantra. But there’s this part of your story that really struck me... you talked about pain—not just life being painful, but that pain for you is constant, and if it wasn’t there, you wouldn’t be able to walk. That blew my mind.

ADAM: Yeah, and it blows most people’s minds when I explain it. You know how doctors ask, “What’s your pain level, one to ten?” I’ve always hated that question. But now? My pain is never below a seven. It might go up, but it never goes down. It’s 24/7. Mostly in my lower legs—ankles, feet—and lessens a bit moving up to my knees and hips. I also have what they call the MS hug. I feel like I’m constantly wearing a corset, just being squeezed.

But I need that pain. My brain doesn’t know where my legs are anymore. Without that pain, I have no feedback. I’ve learned how to recognize the pain patterns—like if I bend my legs a certain way, I feel a certain kind of pain, and that tells me where my legs are in space. If I take painkillers, or even smoke weed to dull the pain, I lose that feedback— and then I can’t walk.

One of my friend's kids, she's 11 years old. They were talking about it and how crazy it is that my brain doesn't know where my legs are. And her theory was that my legs and my brain were in a relationship. Then they broke up and my legs ghosted my brain. And I was like, that is actually brilliant.

ALLIÉ: So the pain is like a messed-up compass for your body.

ADAM: Exactly. A terrible compass—but a necessary one. That’s how we adapt with MS. It’s not a normal way to live, but it’s still living. I’d rather deal with pain and walk, than be pain-free and unable to move.

ALLIÉ: My sister always says, “I’m not dying with MS. I’m living with it.” So Adam, what does living with MS mean to you—not just surviving, but really living?

ADAM: It means doing as much as I can while I can. With the aggressiveness of my MS, I know it’ll get worse. I’ll deal with that when the time comes. But right now? Every day, I just try to be a little better than the day before.

Exclusive Interview with Adam Powell https://awarenow.us/podcast/defying-all-odds

ADAM: (continued) It’s turned me into an advocate, a fundraiser, a public speaker. All things I never imagined doing. I just spoke at Baker College, and I’ve been invited to speak at an MS conference in Missouri. I’ll be on a panel talking about how I got out of the wheelchair.

Really, it’s just stubbornness. That’s what got me through. And I want to be that person for someone else—so they don’t have to go through it alone like I did. I run a monthly support group for people newly diagnosed—three years or less. It’s a safe space to ask questions, vent, just be heard. I didn’t have that when I was first diagnosed. I would’ve loved it. So now I create it for others.

ALLIÉ: Absolutely. Let’s talk about that. You do so much advocacy and create space for others to feel seen and supported. But when the crowd clears and it’s just you—what helps you feel supported and seen?

ADAM: Honestly, my parents. They’re incredible. When I couldn’t walk or drive, they did everything for me. They never complained, but I felt guilty. That guilt pushed me to get back on my feet—literally. My sister’s amazing too. And a lot of the people I’ve met online—on Facebook, TikTok, Instagram—they’ve become more like family than some of my old friends. I lost a lot of friends after my diagnosis. I get it—it’s a tough thing for people to process. It makes them question their own mortality.

But I found my tribe. And that keeps me going. I do a lot of Zoom calls, and I’ve met many of these folks in real life now during my travels. It’s a beautiful thing to meet someone in person after only knowing them as a little square on a screen.

ALLIÉ: It’s that connection. Especially with invisible illnesses, the isolation can be crushing. But when you find your people… Adam, you’ve been handed something most people wouldn’t know how to carry. For a while, you didn’t. But you figured it out. Today, you not only carry this diagnosis—you carry others too. You support them. You give them hope. So, my last question is: What gives you the strength to carry on—not just for yourself, but for others?

ADAM: That’s tough. I think, honestly, it’s just stubbornness again. I’ve never let anyone tell me what to do—and I wasn’t about to let MS tell me either. I still fight with it every day. I’m in pain all the time. Walking still sucks. But I don’t focus on that anymore. I focus on what’s next—my next talk, my next event, my next walk. I always give myself something to look forward to. Looking back doesn’t do anything for me now. So I keep looking forward. That’s what keeps me going. ∎

It’s not because I deny my realities but because I embrace them.

BETHANY KEIME CO-FOUNDER OF HEARTCHARGED

Hannah and Bethany Keime are a force to be reckoned with. I like to refer to them as the Bionic Sisters as they both have ICD’s, or defibrillators, fitted. Hannah was 16 and Bethany was 21 when they had them implanted for the deadly heart condition they were both diagnosed with (HCM or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy). Rather than sit and wallow, these girls are taking the world by storm, setting up a not for profit called HeartCharged, being massive advocates and changing the face of advocacy work. In this conversation I sit down with these incredible sisters to discuss their diagnosis, advocacy work they have done and what’s next.

ERIN: Hannah and Bethany thank you both so much for allowing me to interview you both, two of the most inspiring women I know! You were named as The Fresh New Faces of HCM Patient Leadership. How important is it to you to receive recognition like this as it shows what you’re doing is working?

HANNAH: Thank you for asking. Now that it’s happened, I think being the “Fresh Faces of HCM Patient Leadership” has been the goal all along with our work through our non-profit organization, HeartCharged.

We were diagnosed with HCM, or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a deadly chronic heart condition, when we were teenagers. And that was somewhat by chance because no one even realized we had symptoms. So when we got that surprise diagnosis, we of course started googling HCM and all we could find for people our age were children who had died. Honestly, just a little over a decade ago, most people with cardiomyopathies didn’t make it to adulthood. There was little information for us as young people. We came across maybe one Facebook group which was for much older people that we certainly couldn’t relate to and was a little depressing for us as teens. Then there were people who wanted to charge you a lot of money to get vital information and that didn’t sit right either. I guess right then we knew what we didn’t want to be and what didn’t help us.

BETHANY: After a few years of advocating in our city and state for better outcomes for young heart patients, I felt deeply impressed to go onto social media, specifically Instagram where young people go, with who we were. We had each other but that was the extent of our community. I knew there must be others out there. I said I’m going to take some pictures where people can see the defibrillator I had to get implanted bulging out. And pictures of the meds I had to take. And pictures showing my gratitude and life. And almost instantaneously the thousands who now make up our HeartCharged community started finding us. It started with another young girl afraid of what having an implanted defibrillator would do to her body. Seeing mine and talking with me, she accepted that life-saving treatment basically because of a hashtag that led her to us. Then came a young man in Scotland that never met anyone else with our shared condition. In fresh ways, we were connecting with the new generation of heart warriors. Helping people is our reward and we love getting feedback knowing we are doing just that.

HANNAH: True, but also it’s nice to come into your own and be acknowledged, especially since it helps expand the impact. Some people definitely just dismissed us at first as two young girls doing very different types of posts. Other heart warriors, especially younger ones or their moms in particularly, were thrilled with our fresh approach.

We are being our authentic selves—young women who advocate and create.

HANNAH KEIME CO-FOUNDER OF HEARTCHARGED

“It’s as if we heard the words hypertrophic cardiomyopathy followed by a million doors closing around us and we were left searching for the doors still open to us.”

HANNAH: (continued) There were certainly some people who thought you had to stay in the box to reach people but that obviously wasn’t true. We definitely didn’t feel welcomed among people who should have been advocating besides us. Maybe we were being too real or having too much fun doing it. But since day one, we have been reaching people who had felt alienated and the general public by the millions, which isn’t easy when you are talking about a semi-depressing topic people would generally prefer to ignore.

Now, though, we have a seat at the table, a hard-earned and I’d say well-deserved seat. Our impact is vast and people embrace it. Then this last year, we received a huge recognition. We were short-listed by renowned judges and then selected by our peers from 150 global heart organizations to receive the Global Heart Hub Excellence Award. Wow. I was in Dublin for the annual meeting and when they called HeartCharged it was overwhelming and I could definitely feel it in my heart. We had already captured the attention of the public and now we felt the respect of others for what we were doing and acceptance of how we were doing it in a fresh way.

ERIN: Can you talk a little about your diagnosis and what it meant for you being diagnosed at such a young age?

HANNAH: Great question. It’s interesting the impact of a diagnosis in relation to what stage in life you’re at and how it comes about. As to the stage in life, if you’re a baby, the burden is on the parents and you know no other life. As an adult, you may have already realized your own mortality. But we were teenagers. I just started my freshman year of high school. Bethany was in her senior year. Our life before our diagnosis never hinted at a disabling condition. We were at a time in life where they tell you the future is yours and you are supposed to step out and grab hold. And then our condition took hold of our future, in a number of ways.

BETHANY: And I think there is a lot to be said about what precipitates the diagnosis. For some people, there is a large event, like a cardiac arrest or a car accident. And you are forced to acknowledge a trauma. But here we are, young girls, and we thought we were healthy and we didn’t have an event. Just our aunt got a diagnosis and said we should be checked. We get checked and suddenly our whole paradigm had to shift.

HANNAH: I had symptoms which I had told to my pediatrician but he kept telling me I was fine. I fainted a few times and had abnormal heartbeats and chest pains. Then I go to a cardiologist, just to check, and she says she doesn’t know how I hadn’t dropped dead yet. I was playing varsity basketball and doing competitive dance. She told me I wasn’t going to do that any more.

BETHANY: There I was in my senior year of high school and I’ve just started a prestigious pre-professional ballet program. I had been training 5 to 6 days a week since Kindergarten. I was making my lifelong dream come true. And I was told I could ‘continue for now’ and then ‘dance at 60%’, as if that would keep me working. We seriously went from having a world of possibilities to stepping into the unknown. It’s as if we heard the words hypertrophic cardiomyopathy followed by a million doors closing around us and we were left searching for the doors still open to us.

HANNAH: So true, Bethany. And the childhood, or teens, we still had left, well, they kind of got ripped away from us. My diagnosis definitely matured me. I’m 14 and realizing I’m facing my mortality. Then I was taking medications and

CO-FOUNDER OF HEARTCHARGED

HANNAH: (continued) doing procedures for old people and seeing the cardiologist with old people and was told the only activities I could do were basically ones for old people. And on top of that, we didn’t know how to make plans for the future or really if we should.

BETHANY: So much unknown. And this at the time in life when people start figuring out their future. And ours is now this great unknown. Then when Hannah was still in her teens, she goes into sudden cardiac arrest in her sleep and is only alive because they had implanted a defibrillator in her which shocked her back to life. So she’s looking at life from the other side of death. Like she said, that will mature you and your outlook.

HANNAH: Plus we still looked the same, which was healthy. People around us don’t understand. This disease is now a big part of my identify and I’m needing to forge it into my new reality. But I didn’t have friends who could relate to that reality. I’m thankful they couldn’t, but that didn’t make it any less isolating.

BETHANY: And somewhat depressing. Even though I don’t think we realized it at the time. We’ve always maintained gratitude as a huge part of who we are and why we do what we do. But still, we have created some posts to show our journey and we compile these videos from back when we were first diagnosed. We watch them and we cry. I cry thinking about it. I cry for those little girls and mourn the lives and futures that died when they got that diagnosis.

ERIN: Hannah, you wrote and directed a short film about a young girl dealing with HCM that was accepted into the Disability Film Challenge. Was the story based on your own experiences to raise more awareness around this diagnosis?

HANNAH: I’m grateful for this question. It totally ties into where my life went after my diagnosis. I had been heavily involved in dance and sports and then told I couldn’t continue. When you’re on a team, you get together most every day. You spend hours and hours together each week. That’s what you do and who you are. Those are your friends. And, poof, they were all gone and I found myself with a lot of free time which I couldn’t fill with the activities I used to.

I started watching more TV and films and realized some important things. I realized the power of media and how powerful film and television is. I realized there was a complete lack of representation, especially for young heart patients. I loved seeing the stories but none of the characters ever acted like me. Also hope wasn’t as apparent as I think it is in real life or that it should be. Anyway, I was simultaneously lured into the industry because of the power it held and determined to change the industry because of the power it had yet to capture for the patient community.

I eventually got my filmmaking degree from Full Sail University. One goal I had going in was to present heart patient life, not just to represent ‘my people’ but also to let the general public know that young people have, and too often die from, heart conditions so that more young people would get checked and everyone would know warning signs. I wanted people to be educated enough to take action, but not too scared to act. When I was able a few years ago to participate in the Disability Film Challenge, of course, I told the story of a young heart patient. Now the finished film has to be 5 minutes or less and finished from writing the script to filming and editing in five days. I had a $0 budget and a cast of 4, my best friend, her mom, my sister, and me. We had certain rules we had to follow and certain items we had to include. So definitely a ‘challenge’.

The story I wrote was inspired by my own experiences. Hey they say write what you know. But obviously there is more to my tale than a 5-minute film. Excitingly, I just won a grant to produce another short film which will be a bit longer and that makes me happy because there’s so much more to tell. The main character is a young girl dealing with HCM as well. The new film will delve into a different aspect of living with an invisible disability. However, the challenge film was about friendships. It also included a boyfriend which right there makes it not autobiographical.

I actually see myself in both characters. There is the friend who is loyal despite you having other interests or people in your life or a disability or diagnosis. And there’s the girl with the limitations who is being left behind by able-bodied friends. I loved bringing an invisible disability viewpoint to the challenge. Also out of the 150 films submitted, no one else focused on heart disease and that deserve space. Heart defects are the leading birth defect. Also I wanted to show what true empathy and friendship would look like, and it is in no way the same as pity.

HANNAH: (continued) Since I released it, there have been a tremendous number of positive responses and even older white British men said they felt seen in this movie. The heart community definitely loved the representation and I realized I made a good decision going to film school. Now to find someone who made a good decision and became a venture capitalist…

Hearing so many people saying thank you for telling this story has inspired me. I wrote it where you had this ideal, great friend. And I could write it now because I do have some great friends now though from my experience in high school, my outlook then would have been less optimistic. Also I wanted optimism with a diagnosis. Too often if there is any type of heart patient story on TV, the person dies or goes into a coma. With HCM now, we can have the same chance of living, though we need treatments and care to do so. Part of that care requires standing up for ourselves in medical situations and part in personal situations. We deserve better than this girl had in her relationship with her boyfriend. We have value and add value to a relationship.

ERIN: You are big advocates for children to be screened for heart conditions. Have you found that through your work more children are able to be screened now?