AWARENOW

THE WORLD'S OFFICIAL MAGAZINE FOR CAUSES

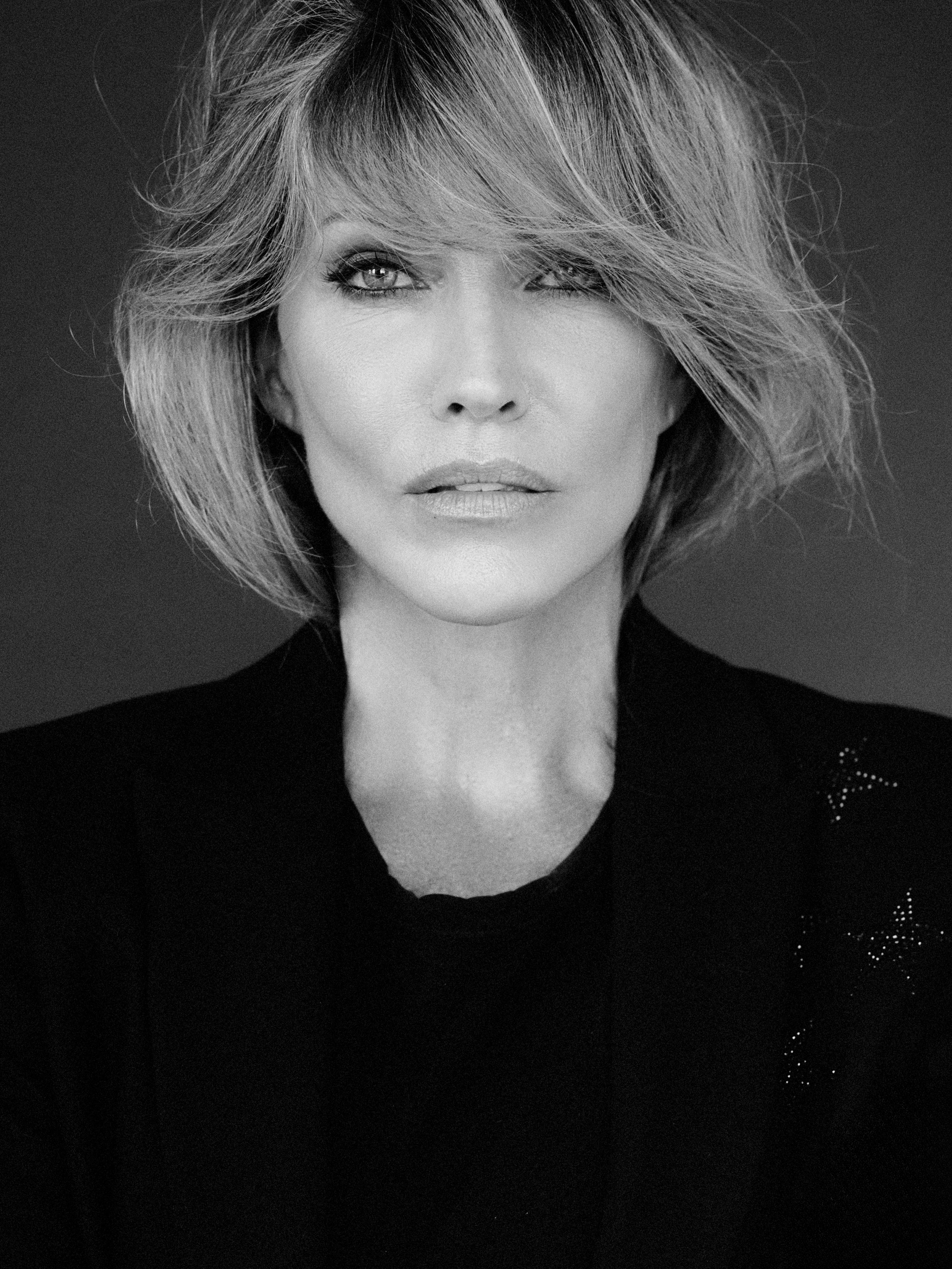

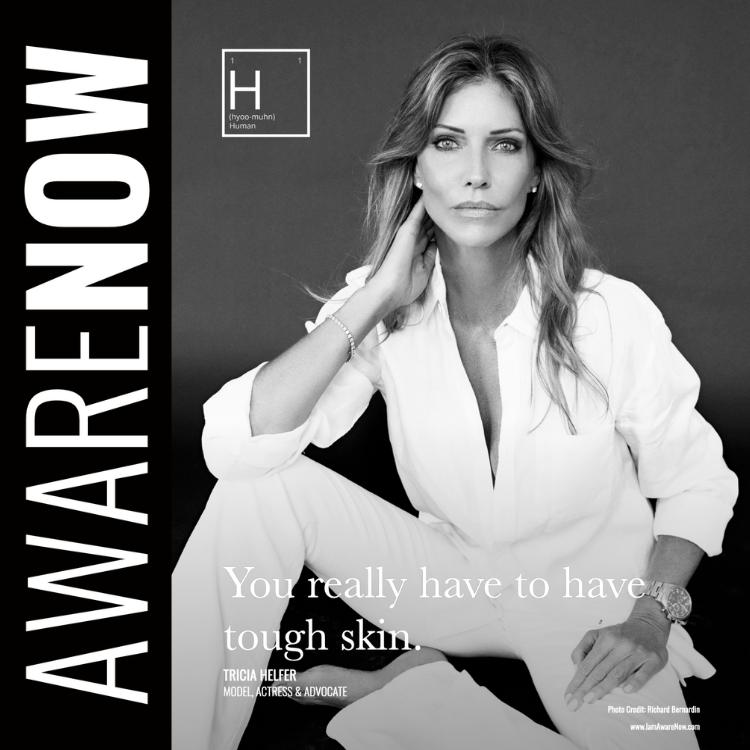

ON THE COVER: TRICIA HELFER PHOTO BY: RICHARD BERNARDIN

AwareNow Magazine is a monthly publication produced by AwareNow Media™, a storytelling platform dedicated to creating and sustaining positive social change with content that inspires and informs, while raising awareness for causes one story at a time.

DETOUR TO THE EIFFEL TOWER

DAMIAN WASHINGTON

MORE THAN SKIN DEEP

PAUL S. ROGERS

HELLO BEAUTIFUL

TRICIA HELFER

I AM NOT A BURDEN

KAM REDLAWSK

HOPE

ADAM POWELL BEYOND

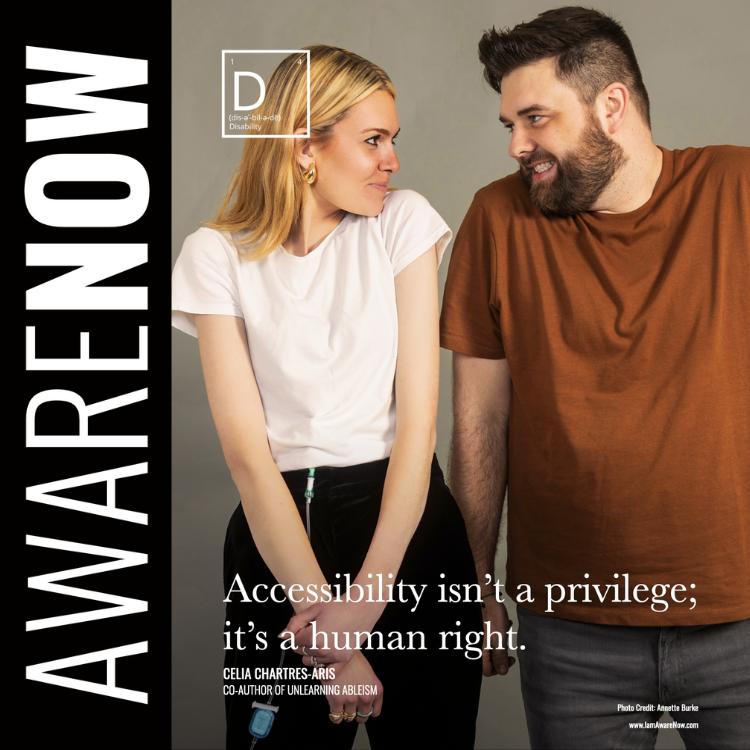

UNLEARNING ABLEISM

CELIA CHARTRES-ARIS, JAMIE SHIELDS

BREAKING MISCONCEPTIONS

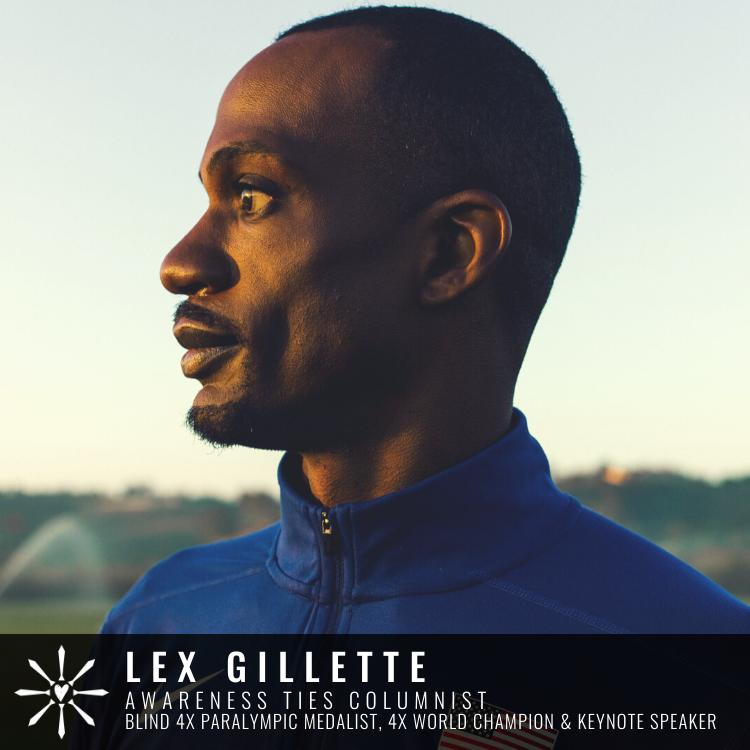

LEX GILLETTE

THE ART OF RESILIENCE

ROXANNE MESSINA CAPTOR

HEALING IS HARD

JACK MCGUIRE

A

SINA SINBARI MAKE

DANIELLE TODD, MAKE FOOD NOT WASTE

SHOUKEI MATSUMOTO

BEAUTIFULLY DANGEROUS

YULY GROSMAN

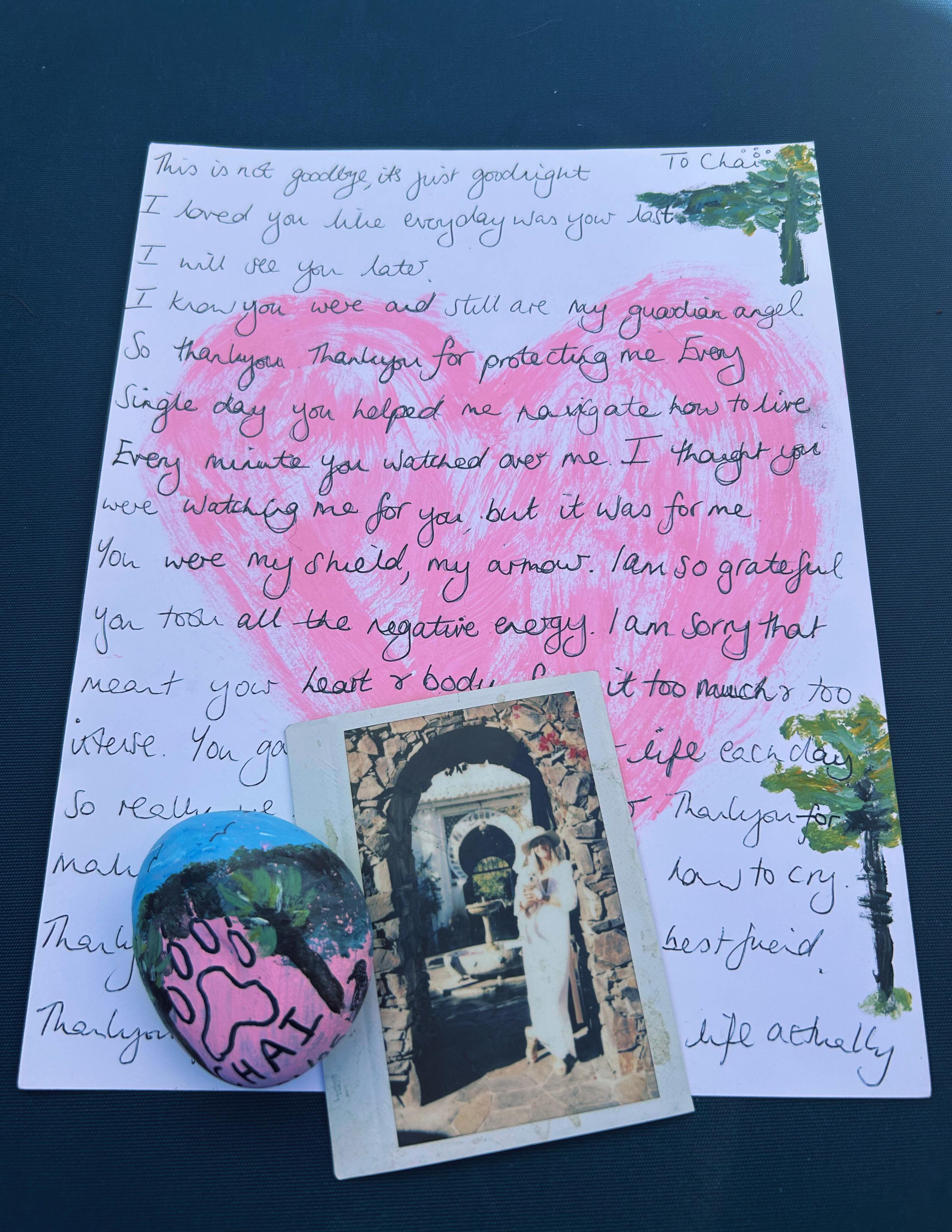

GRIEF

ELIZABETH BLAKE-THOMAS

SAME HERE

ERIC KUSSIN, ERIN MACAULEY

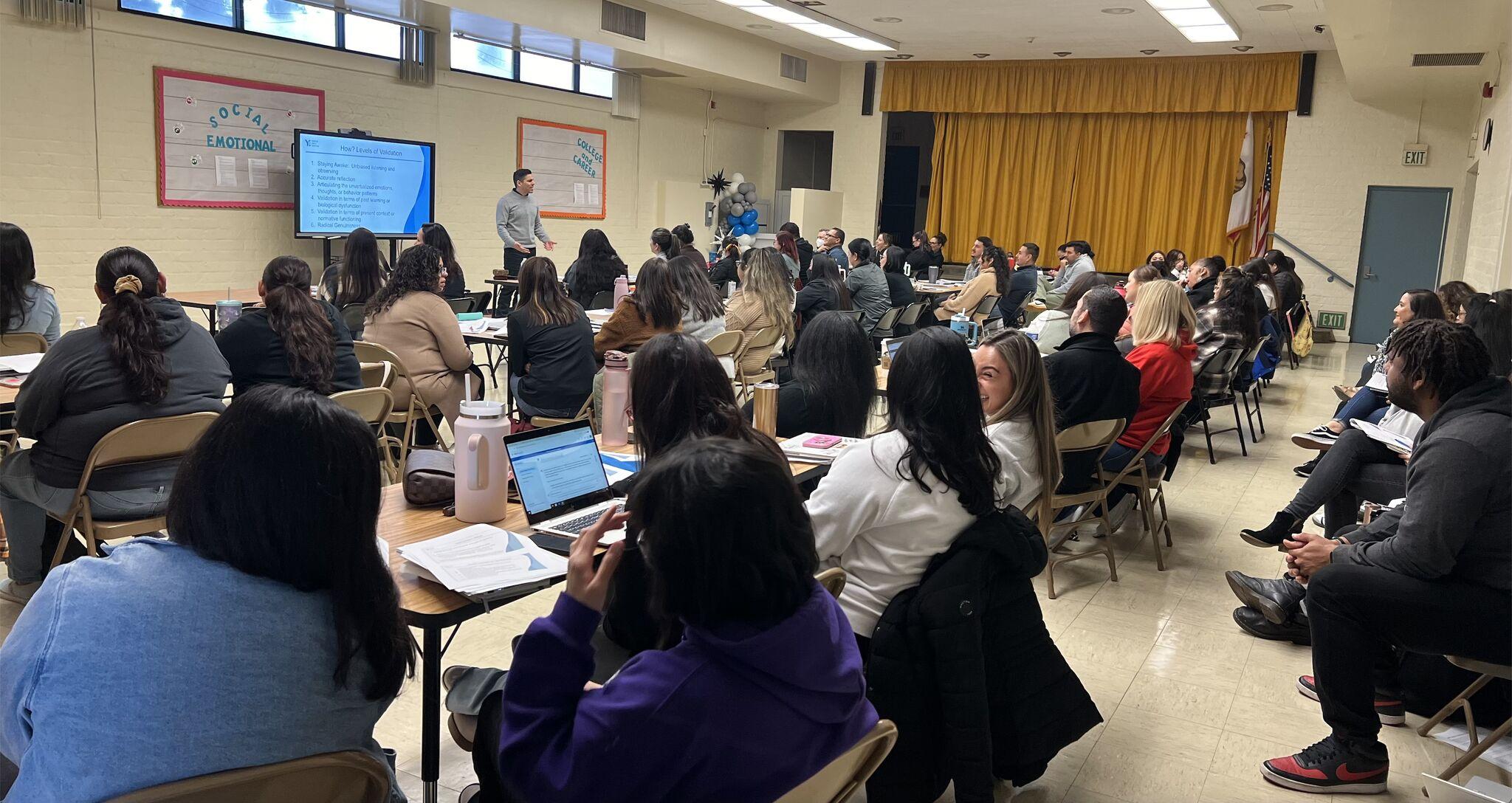

VALIDATION IN EDUCATION

DR. MARCUS RODRIGUEZ

KEVIN HINES

Everything has beauty, but not everyone sees it.

Confucius

beautiful : (adj.) The presence of light found not in perfection, but in purpose — where strength meets service and the human spirit shines through

Beauty is often hard to find under the weight of the world. Yet it is here, quiet but constant. Found in the hands that help, the hearts that hold, and the souls that serve. It’s in the courage to keep going when life asks you not to. It’s in the strength to see others before yourself, and in the grace that comes from doing good even when no one is watching. This edition is a reflection of that beauty. Not the kind framed in glass or filtered through lenses, but the kind made through struggle, sacrifice, and service. The kind that lives within us all, waiting for the light of purpose to bring it to life.

AwareNow, more than ever, we must remember how beautiful the world truly is — even in dark times. To see beyond the shadows and believe in the light within ourselves, and within one another. To have faith in what connects us all: the power, the purpose, and the promise of The Human Cause.

CEO & Co-Founder of AwareNow Media

Allié McGuire began her career as a performance poet, transitioned into digital storytelling as a wine personality, and later produced the Hollywood Film Festival. Now, as co-founder of AwareNow Media, she uses her platform to elevate voices and champion causes, connecting audiences to stories that inspire change.

President & Co-Founder of AwareNow Media

Jack McGuire’s career spans the Navy, hospitality, and producing the Hollywood Film Festival. Now, he co-leads AwareNow Media with Allié, focusing on powerful storytelling for worthy causes. His commitment to service fuels AwareNow’s mission to connect and inspire audiences.

The views and opinions expressed in AwareNow are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official Any content provided by our columnists or interviewees is of their opinion and not intended to malign any religion, ethnic group, political group, organization, company, or individual. Stories shared are not intended to vilify anyone or anything. Their intent is to make you think.

* Please note that you may find a spelling or punctuation error here or there, as our Editor-In-Chief has MS and lost vision in her right eye. That said, she still has perfect vision in her left and rocks it as best as she can.

I’m walking a 5K from my crib to the Eiffel Tower and back again, because I can.

DAMIAN WASHINGTON COMEDIAN, ACTOR, VLOGGER & MS ADVOCATE

When my dear friend, Damian Washington, told me he was walking a 5K from his home in Paris to the Eiffel Tower and back—for me (Allié), for our film ‘Because I Can’, and for our MS community—I was moved beyond words. I laughed through tears as I watched and listened to him narrate each moment with humor, honesty, and heart. This walk wasn’t just his—it was ours, step by step, proof that together, no distance is too far when walked with purpose and love for your community. Here is what Damian shared on his walk…

I’m walking a 5K from my crib to the Eiffel Tower and back again, because I can.

The homie Allié McGuire is running a 5K. She’s doing this race and really invited a bunch of her friends in the MS community, and a bunch of supporters and caregivers, to join her.

Thar she blows, right there. (Eiffel Tower seen in the distance.)

Ah, my usual route—‘barreé’—it’s closed for construction. So just like with multiple sclerosis, if I’m gonna do this, I’m gonna have to find another way to make it happen.

Alright, we should be back on track now.

So just like I said, you know, MS takes away your ability to do things like you thought you were gonna be able to—like going to the bathroom, or just living a regular, normal life, or your vision, or your energy.

Literally, there are 20 things that can be wrong with you when you have MS that I can’t really think about right now because I’m walking and trying to film this video all at the same time.

The point is, if you are determined, you can still get to your destination.

There she go, right there. (Eiffel Tower seen in the distance.)

One of the things you do when you have MS is you make adjustments. So, I have on a layer, and I had to take that layer off so I wouldn’t get too hot—because heat sensitivity is a thing. (Takes off one of his layers and ties it around his waist.)

And this video would not be going on very well if I got overheated, and my knees didn’t work, and my balance didn’t work. So I just had to make sure to take off a layer so that it would be down here and ‘tied on me’, instead of ‘on me’ making it all hot—because ooo, child, this’d be a much shorter video than it is.

When you have a condition like this, there are so many unseen things with its thumb on the scale. So people like to call it an ‘invisible disease’, but I know I see it. And the people around me, I know they feel it as well.

One gorgeous thing about this town is that there are plenty of public benches here. So I’m just gonna have a nice little seat on one. They said they was gonna do the 5K, but you know, she said you could take as long as you need to get it done. Yeah, I’m gonna take my time—give myself some grace.

Inch by inch,

AwareNow Podcast

DETOUR TO THE EIFFEL TOWER

Feature Story by Damian Washington https://awarenow.us/podcast/detour-to-the-eiffel-tower

One of the MS homies says, “Yard by yard it’s hard, but inch by inch it’s a cinch.” Okay. So I just had to give myself a little rest, because inch by inch, baby.

Boom, there you go, right there.

(Eiffel Tower seen just behind him.)

See, it’s right there.

I mean, I would get closer, but my knees and my legs—just my overall fatigue—it’s just like, “Yo, bro, you know you’ve got to make it back home, right?”

So, in order to honor that and still make my 5K, I’m just like, “Yeah, how about you just turn back around and go back home while you still can son?”

Also, Allié’s doing this all at once. Like, bro, I’ve been stoppin’. I’ve been sitting on benches. I’ve been taking breaks to sit here and think of things to say.

She’s doing this all at once—like it’s a thing to do. But of course it is, because she wants to. And if she wants to, and she can, why not?

Because she can.

Also, I can too—which is why I’m even making this video in the first place.

Shout out to Allié McGuire.

Shout out to all the MS patients out here who’s in my feed. Peace, joy, and love to you. ∎

If you don’t already follow Damian, you should. Find him on Instagram: @damianwashington

PAUL S. ROGERS

The Genie never answers the phone, as the Genie answers to no one.

In society beauty has been packaged and sold as a commodity. There is a clear line dividing those who have and those who don’t have beauty. Social media doubles down on surface polished appearances, carefully curated images, flawless skin and picture-perfect smiles. Being “perfect” and “beautiful” have become interchangeable ideas designed to keep us locked into an overconsumerist pursuit of happiness.

With all this interference it is easy to forget what beauty truly is. True beauty, which is more than skin deep, has little to do with symmetry or perfection. It is born of character, kindness and authenticity. It is more preoccupied with the way a person makes others feel when they are near. When beauty is more than skin deep, it transforms from something superficial into something far more enduring.

We have all met people whose presence lights up a room without any need for glamour or fanfare. Instead, it is their laughter, compassion, and willingness to listen that make them magnetic. They remind us that beauty is not a possession but a gift we offer through the way we live and love. Surface charm may catch the eye, but it is the depth of spirit that captures the heart.

True beauty often shines brightest in ordinary acts. A smile given to a stranger, patience with someone struggling, encouragement given when another is on the edge of giving up. These are the brushstrokes that paint a true portrait of beauty. Such gestures will never make the headlines, yet they ripple through the lives they touch. When we look back on the people who mattered most to us, it is rarely their physical appearance we recall, but rather how they treated us, how they believed in us, and how they made us feel valued.

This deeper kind of beauty stands outside the ravages of time. It grows rather than fades. Physical features inevitably change but age has a way of softening the sharpest edges and gracing us with lines that tell stories of laughter, tears, and resilience. A person who nurtures compassion, integrity, and courage becomes more radiant with every passing year, because their beauty springs from an internal source that cannot diminish.

When beauty is more than skin deep, it becomes an act of service. It reaches beyond the self and seeks to uplift others. The most beautiful people are often those who have walked through hardship and chosen to let it make them softer rather than harder. They carry a quiet strength, a grace that inspires, because they know what it means to stumble and rise again. Their scars are not blemishes but remind us that even in brokenness, beauty can be found. In Japanese culture this is celebrated in “Kintsugi.” Kintsugi is a traditional repair method for broken ceramics using gold to join the fragmented pieces together. This process creates something uniquely imperfect but also far more beautiful.

This understanding not only changes the way we see others but also ourselves. Instead of striving for the unattainable ideals set by society, we can cultivate beauty that grows from within. Every time we choose forgiveness over resentment, hope over despair, generosity over selfishness, kindness over being right we add to our inner light. That light not only illuminates our own path but also becomes a beacon for others who may be walking in darkness. This is why being of service to others also lights our own paths more clearly.

Written and Narrated by Paul S. Rogers https://awarenow.us/podcast/more-than-skin-deep

“We

This kind of beauty is available to everyone, not just the select few. We do not need wealth, fame, or flawless features to embody it. It is found in authenticity and having the courage of showing up as who we truly are. It is choosing to contribute to something far greater than ourselves.

When we start to view beauty in this way, our perspective shifts. We see beyond appearances, valuing people for the stories they carry, the battles they’ve fought, and the light they shine. We become less critical of ourselves, recognizing that our worth is not tied to perfection but to presence. And we begin to live with greater intention, knowing that every word and action can add to the beauty of the world around us. ∎

PAUL S. ROGERS

Transformation Expert, Awareness Hellraiser & Public Speaker www.awarenowmedia.com/paul-rogers

PAUL S. ROGERS is a keynote public speaking coach, transformation expert, awareness hellraiser, life coach, Trauma TBI, CPTSD mentor, train crash and cancer survivor, public speaking coach, Podcast host “Release the Genie” & best-selling author. His journey has taken him from corporate leader to kitesurfer to teacher on a first nations reserve to today. Paul’s goal is to inspire others to find their true purpose and passion.

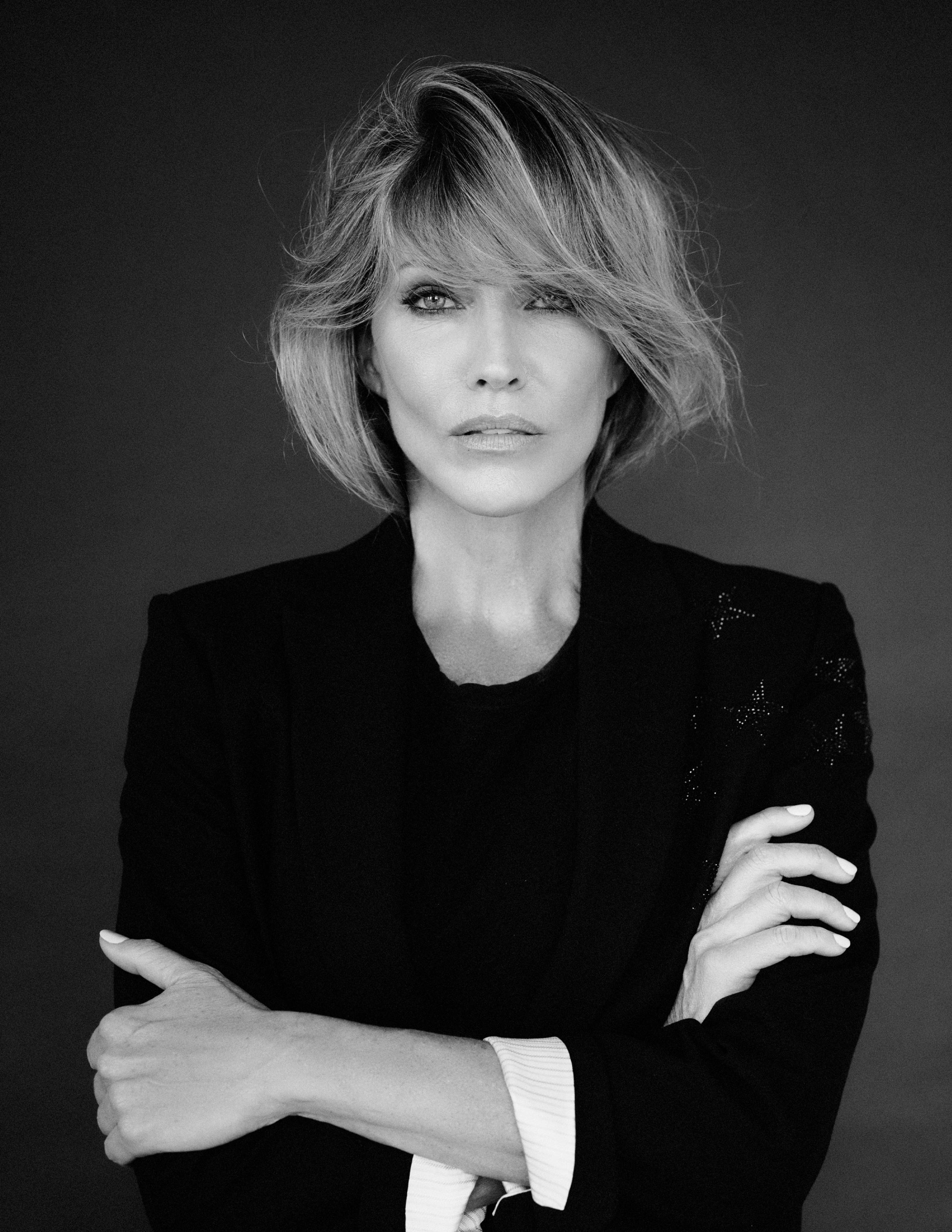

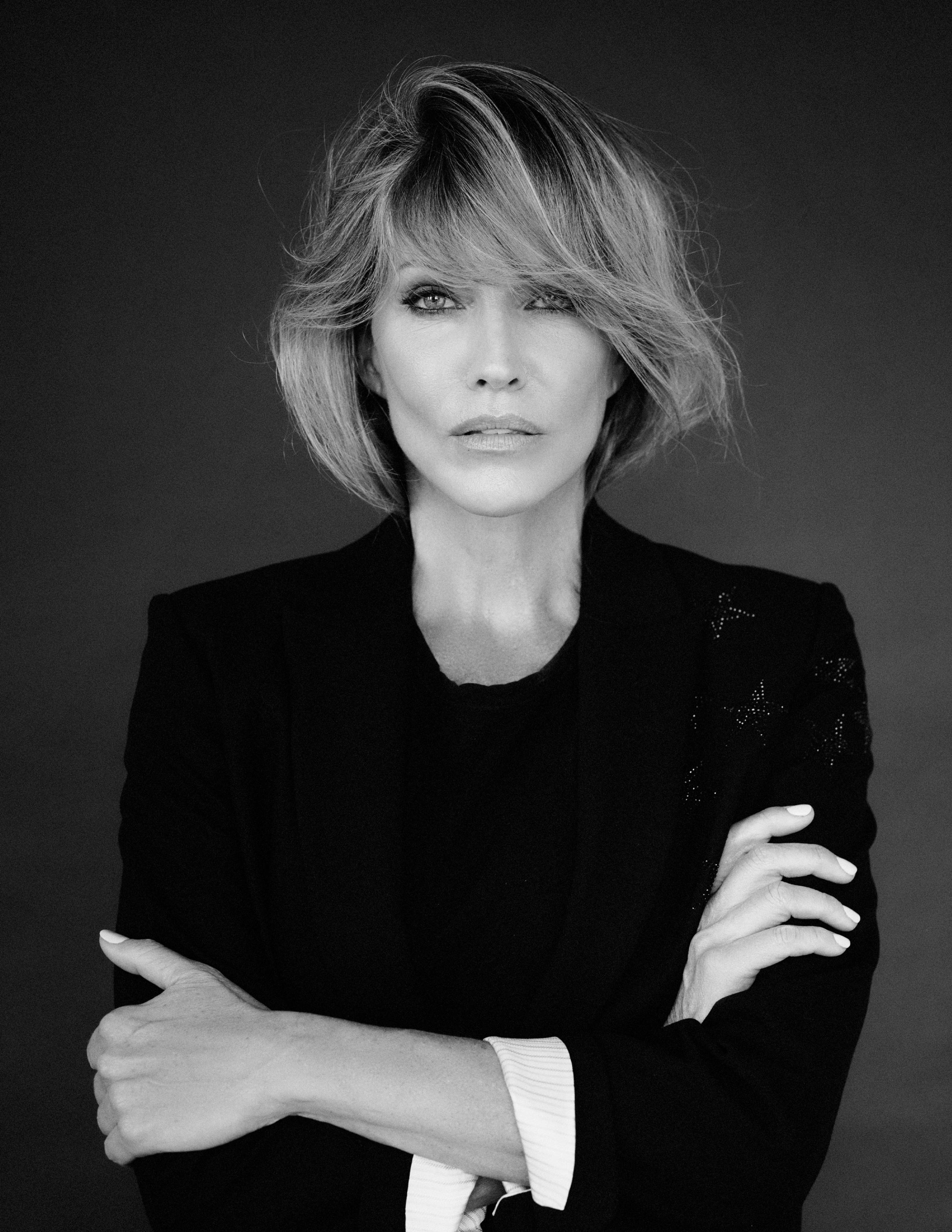

Beauty is often seen, but rarely felt—until empathy enters the frame. For actress and advocate Tricia Helfer, beauty is about more than appearance, it’s about awareness. From portraying a woman rediscovering her worth after breast cancer in Hello Beautiful, to standing up for animals whose voices often go unheard, Tricia reflects a truth we often forget: empathy is the bridge between strength and softness. Here she opens up about the power of compassion and its ability to redefine what it means to live beautifully.

ALLIÉ: As October is Breast Cancer Awareness Month, let's begin today with a conversation about a film you recently starred in. In Hello Beautiful, you step into a story rooted in survival, self-image, and rediscovery. Now, while you yourself haven't faced breast cancer, what did embodying that experience teach you about the kind of beauty that endures beyond appearance?

TRICIA: I have not experienced breast cancer myself, but I know people who have. I actually had a very good girlfriend diagnosed with breast cancer while I was filming that show—she was 50 years old. And she purposely didn't tell me while I was filming because she didn't want to upset me. She was concerned about me filming as opposed to

I don’t think I’ve ever placed selfworth on beauty, but it is very hard to come from a modeling background and be in the acting field and not have it creep in…

TRICIA HELFER MODEL, ACTRESS & ADVOCATE

TRICIA: (continued) answering your question, but when filming it, I was portraying a version of a woman for whom this was her real story. So much of her platform since has become about the acceptance of the change in your external beauty during something like this. She was and still is a model, and she says she based so much of her selfworth on external beauty—and that’s understandable when that’s how you make your living and how the world sees you because of your job.

For her, I tried to put myself into her eyes and tell her story. But of course, it can’t help but be reflective of my own life, seeing that I’ve had a similar story to hers. I don’t think I’ve ever placed self-worth on beauty, but it is very hard to come from a modeling background and be in the acting field and not have it creep in, even if you know consciously and subconsciously that that’s not what it’s about. So, I don’t know if I learned anything specifically during the filming that I didn’t already inherently know, but it certainly put it at the forefront—something that needs to be continually worked on within myself, for sure.

ALLIÉ: Let’s talk about the fact that empathy sits quietly at the center of that story—a woman seeing herself through new eyes. As someone who’s spent years in an industry that celebrates the external, how has your own definition of beauty evolved into something more internal and intentional? How has that definition changed for you over the years?

TRICIA: I think it’s a constant struggle. To be completely frank, I think I’m struggling more with it now at this time in my life than I did throughout my youth. The ageism in Hollywood is affecting me more now—feeling that external pressure. I grew up on a farm, among hard workers, where not much emphasis was placed on looks aside from normal human nature. It’s a hard question because you talk about empathy, and the theme of the movie is her accepting herself and her change in herself, but it’s also about what society puts on you. You really have to have tough skin.

I remember I got into an argument with somebody I don’t even know. I had posted a photo of myself—it had nothing to do with looks—but this person made it about that. People do that all the time. I think empathy is more about having kindness toward each other and toward ourselves. I’m probably my harshest critic. I go through waves. It’s not like I’m all-knowing now and because I’ve done this movie, I’m immune to those thoughts. Of course, I know external beauty

TRICIA: (continued) isn’t what’s important—I know that inherently—but I’m not immune to it. It’s a constant struggle, and I can only hope that with age comes wisdom, that I’ll get over that hump and never be bothered by another comment or by looking in the mirror and seeing changes. But have I mastered it? No. Am I trying? Hell yeah.

In Hello Beautiful, beauty is stripped away because of health. There’s so much more that’s not just about external beauty—it’s about vitality. It’s not only about losing hair or weight. It’s about feeling like your life is ebbing away. You’re not able to walk up the stairs without being exhausted. So it’s not just about beauty per se—it’s also about health and struggling with the fact that you’re not healthy.

ALLIÉ: Yeah—of what you once had but no longer have. What do you do with that?

TRICIA: How do you deal with it? And will you ever get it back? If you survive, will you get it back? Will it be altered permanently? Specifically with breast cancer and mastectomies—when I was researching for this role, my mother had recently passed away from colon cancer, so it was all very close to home. When researching, I discovered there’s a much higher likelihood that if a couple is married or in a relationship, it will end in divorce or separation than with any other cancer. There’s that element of a woman feeling she’s lost something that will keep her mate attracted to her.

With Christine, the real woman my character Willow is based on, that’s one of her platforms—to bring awareness and acceptance to the flat-chest movement. Some women who go through mastectomies can have reconstructive surgery, but some can’t. Some experience complications, others can’t afford it or can’t take the time off work. Christine had complications and no longer has enough tissue for reconstruction. That’s part of her advocacy—to redefine femininity and beauty beyond reconstruction. I was amazed when I found out how much higher the divorce rate is. It was staggering.

ALLIÉ: That’s wild. To have to sit with that—I think it comes back to realizing we can’t ever be the version we were. We can only be the version we become.

TRICIA: And try to learn how to accept that and be happy with where you are.

ALLIÉ: Absolutely. You were talking about Christine’s platform—what about yours? You’ve used your platform to protect and uplift animals, lending your voice to those who have none. In what ways does your work in animal advocacy echo the same empathy that draws you to human stories of healing and resilience? Where’s that through line in all this?

TRICIA: Having empathy for others—for someone going through something—translates to animals too. Animals are feeling, thinking beings. It amazes me that parts of science still debate whether animals have emotions or recognize us after time away. Of course they do. A lot of my work focuses on animal testing—pushing for legislation to ban cosmetic testing on animals. It’s outdated and unnecessary. We now have computer modeling and cell-based testing —there’s no reason to keep using animals. So, for me, it’s about empathy. Thinking of another being—what they’re going through. If I can use my platform to bring awareness to causes I believe in, then I think it’s my responsibility to do so.

ALLIÉ: In your work as an actress, you’ve portrayed light and dark—goddesses, villains, survivors—so many different characters. When you strip all that away, what part of you do you hope audiences recognize across all those roles? What’s your signature?

TRICIA: I don’t really know. I do play a lot of bad characters. A character may know they’re doing something wrong but still do it anyway. You have to come at it from their perspective, so I always try to find the vulnerability—something that explains why they’re doing what they’re doing. Not saying it’s right, but maybe it makes it understandable. I’ve been told that I usually find some sort of vulnerability—again, it goes back to empathy. There’s something people can empathize with. They might disagree, but they can still understand. That’s usually what I try to find, even if it’s subtle or hidden in the performance. For me, that empathy often bleeds through, even if the audience doesn’t consciously notice it.

Exclusive Interview with Tricia Helfer https://awarenow.us/podcast/hello-beautiful

ALLIÉ: I love the artistry of that—those little nuances of how you pull that emotion and embody it in your roles. So, one more thing I want to discuss today. This month’s edition of AwareNow is called The Beautiful Edition. Let me ask you personally: when was the last time you said, out loud or not, “Hello Beautiful” to a moment, a person, or a cause that reminded you why empathy really matters?

TRICIA: It wasn’t the exact words “Hello Beautiful”, but the sentiment was the same. I said something similar to one of my sisters—Tammy, my oldest. She’s been taking care of our father, who’s very ill with Alzheimer’s. She’s really taken on the caretaker role since our mother passed away, putting her own life on hold in many ways. I was with her recently, and after seeing all that she does, I said to her, “You’re a rock star, and I want to make sure you’re okay.”

Going back to the film, there’s sometimes not enough attention paid to caretakers—and that was something Christine wanted to focus on in the movie as well. So, I asked my sister, “Are you okay? Is there anything I can do to support you?” I live in another country, so I can’t be there often. She said, in her typical way, “No, I’m good.” But I wanted her to know that I see her—that I see what she’s doing for our family. That, to me, was “Hello Beautiful” to her. ∎

KAM REDLAWSK

STORY BY KAM REDLAWSK

I am NOT A BURDEN.

I am NOT A BURDEN.

I am NOT A BURDEN.

Disabled people are NOT A BURDEN.

Feeling like a burden can create everlasting shadows of worthlessness & shame. As an adoptee, I’ve felt the relics of being a burden since I was abandoned. I was frequently reminded I was unwanted, bought & paid for, which required sacrifices I should only feel lucky for. This is where adoptee stories typically end. Our lives & stories are reduced to an unwanted burdensome child, and our story finishes with how amazing the adopters must be. The conversation about the system orphans have had to endure, the trauma, pre-and post-adoption, and the many kinds of abuses potentially inflicted is never acknowledged by society & adoptive families. The shimmering romanticism of adoption is preferred, nobody wants to hear our side.

As a disabled person, I’ve felt the familiarity of being seen as a burden through the consistent responses to my disability. I’m considered useless, incapable, with sadness forever fixated over my head like a pitiful halo, accompanied by the amazement of what a saint my partner must be for “sacrificing his life”. Society feels the need to remind me of how inferior & undesirable I am, and that it’s exceptional that someone took on such a broken person. “You’re lucky!” is the glint in people’s eyes when they see us, not, “You’re looked upon inhumanly & limited access by society. I’m sorry.”

These labels have unjustly deemed me as the paltry one; as if this is the only redeeming thing about me after 46 years of life—the unwanted with “too many problems” to include or love. Meanwhile, much of who I am is sidelined without a blip of curiosity beyond identities I never asked for.

As an orphan and a disabled person, I’ve felt I’ve had to constantly prove my worthiness in order to be, and continue to be, loved & to deflect the burden I am. These feelings infiltrated me since the beginning, creating a ruthlessly selfcritical person. But after 46 years, this has become tiring. I am not a burden. And neither are you. ∎

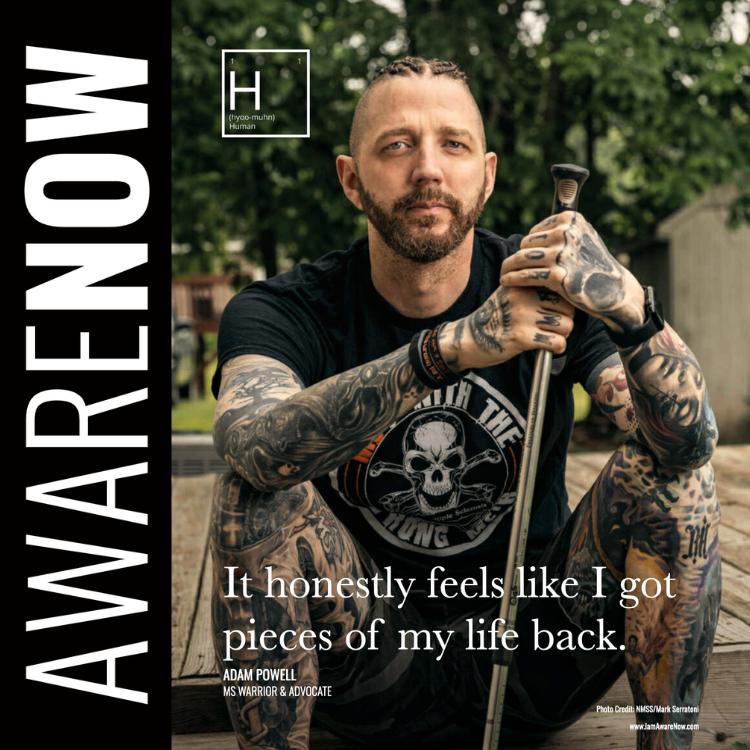

When life told Adam Powell to stop, he found another way to go. Living with multiple sclerosis, Adam learned early on that strength isn’t about how far you go — it’s about how you keep going. Now, with neural sleeves helping him move in ways once impossible, his journey continues as proof that hope is more than a feeling — it’s a force in motion.

ALLIÉ: Focusing on your MS journey from diagnosis day until now, remind me how long it’s been since that day?

ADAM: It's been just over six years. It was June of 2019.

ALLIÉ: Okay, so just over six years. As you and I both know, while there are many obstacles that MS presents, especially with primary progressive multiple sclerosis, which you have, what is the one that has been the most frustrating for you today?

ADAM: The biggest one, and one I still fight to this day, is my legs and trying to walk. After I was diagnosed, it was five months before I was in a wheelchair, and I was in that wheelchair for about nine months. Then I started doing my best to get out of it and walk again. I’ve been able to, and now I just keep moving that along as best I can. It's not

ALLIÉ: Try really hard to walk this badly. Let’s talk about the fact that you’ve come a long way since that diagnosis. What led you to discover Neural Sleeves? I want today to be a sleeve conversation. How did you discover it, and what was your first experience with it?

ADAM: I discovered it years ago, when they first got FDA approval. It’s been on my radar for a long time. I remember reaching out to them early on and saying I was interested, but I needed two of them. There was no point for me to have only one because one leg is bad and the other is worse. They were just launching their first products and said they couldn’t do that at the time. So, I kept an eye on it. I happened to go to a conference in Branson, Missouri, back in August—Modified by MS, hosted by Matthew Price. He does a lot for the MS community. This was his second big conference. I went down to Branson, Missouri. I actually spoke down there too, which was cool. Cionic happened to be there and had a table set up with vendors. I was like, oh, this is awesome. It’s been on my radar for years. Now I can actually talk to them. Now I can try them out.

As soon as the day of talks was over, I remember my friend Michael Zink raced out there to beat me so he could be the first one to try them out. He did, and it helped him. He’s pretty mobile, but he gets a problem where, the more he walks, the more his drop foot comes in, so it can help him in the long run.

I tried it on, and they let me have both sleeves. We got dialed in—it doesn’t take long—but we were trying to get the right amps to each muscle to make my foot raise the right way. It’s really cool what you can do with those. So, we finally got all eight sets of electrodes set, four on each leg. All your major muscles—hamstrings, quads, shins, calves —it’s firing them all. I took a walk without it turned on, just the sleeves on, and walked down the hall. I was stepping in front of myself, getting this hitch in my knee, hunched over—just my normal walk. Like I said, I try really hard to walk that bad, but I still walk, and I’m proud of that.

When I got to the other end, they turned it on, and I just started walking. It felt good—smoother. I felt like I was walking better. I didn’t have as much shaking or ataxia. My foot wasn’t crossing over the other. It felt really good to me, which I was super proud of. One girl said, “Oh my God,” and other people were like, “Holy cow.” I thought, wow, this is really good. Then I saw the video of it, and it blew me away. You see my normal walk, and then my walk with it—and this was the very first time I ever had it on. My posture was completely upright again. I didn’t realize that while walking, but when I saw the video, I thought, oh my God, I’m walking almost normally. I would’ve liked to wear them more, but so many people wanted to try them because they saw what it did for me. They were like, holy crap, this is amazing. Right then, I was sold.

ALLIÉ: So, you were sold when you saw the results. What about the moment before you put them on? I’m wondering about the balance between skepticism and hope before you had proof.

ADAM: I was actually pretty hopeful because in physical therapy I’ve done a lot of electrical stimulation, and it’s helped me—like the RTI bike. When I wasn’t walking, we used the RTI bike to help fire my muscles in the sequence of riding, so they got moving again. I’ve done TENS units. When I was learning sit-to-stand, I used TENS to help me come up onto my ankle. I’m used to the stimulation and have seen a lot of results from it. The latest before that was TSS—Transspinal Stimulation. My therapist came back from a conference and told me about it. It was originally made for spinal cord injuries, sending electric signals through the spinal cord to trigger responses. She said, “Why wouldn’t it work for MS?” and asked if I wanted to try. I said, hell yes, let’s do this.

I was her guinea pig, and it’s such a strange sensation. The only way I can describe it is it feels like an electric woodpecker on your neck. As I was walking, I felt like I could shoot lightning out of my fingertips. It’s very weird to get used to. It’s mobile, but she had to carry the whole thing on a cart next to me because I was hooked up to wires. It made me walk better. Again, it took away my ataxia. I wasn’t shaking, I was walking straighter, my stamina was better. We did a little the first day, a little more the next, and by the third time I used it, I walked out to my car without stopping or using my stick. That was huge. The residuals were awesome.

“I golfed an entire 18 holes and walked almost four miles that day. There’s no possible way I could’ve done that without the sleeves.”

ADAM: (continued) So, when I went into the Cionic experience, I was very hopeful because I’ve seen what electrical stimulation can do. It had been on my radar for so many years that I was pumped to see what this could do. There was zero skepticism from me.

ALLIÉ: On the opposite side of skepticism—in your words, you’ve described these Neural Sleeves as a game changer. Was it that first time you tried them, or another moment later, when you realized they were helping you do something you hadn’t been able to do in a long time?

ADAM: Honestly, it was right when I tried them for the first time. That little two-minute video clip was the only time I had them on then. I was in Branson, finished up my trip to Colorado, and by the time I got home, the sleeves were already there. I had my appointment to get them set up and then I was off. What’s great about this company is they’re small and new—many people don’t know about them. I posted that video on my social media and it got about 70,000 views. It blew up. The company saw it and said, “We’re going to make you an ambassador,” and they gave me the sleeves. Even if they hadn’t, I was buying them anyway.

I had them set up and went outside. I walked without them first, then with them, and you could see the difference. The next day, Friday, I went outside and did something I’d never done—I walked down my driveway, down the road three houses, turned around, and came back without my stick. That was something I had never done before. When I was learning to walk again, I’d have to rest four, five, six times. I carried a tripod stool because I had to sit and rest. But this time, I just got up, walked, and did it.

The next day, Saturday, we had a golf outing for one of my good friends who passed away last year. I wanted to support his wife and kids. I figured I’d maybe play three holes and get some funny footage of me swinging and falling over. I golfed an entire 18 holes and walked almost four miles that day. There’s no possible way I could’ve done that without the sleeves. Being new to them, I was experimenting with the app, turning up my shin setting as I got tired so it would raise my foot more. The batteries last about eight hours—I wore them for ten and a half because I turned them off when I wasn’t walking. Afterward, even when they died, I still walked safely without my stick. The residuals trained my muscles and reminded them what to do. I couldn’t believe I golfed 18 holes. I just golfed another 18 this past Saturday. I don’t even like golf.

ALLIÉ: Like it or not, you’re going to be a golfer now, just because you can.

ADAM: I’m going to be a golfer now, just because I can. Exactly.

ALLIÉ: I’ve seen the video—it’s incredible to witness. Seeing is believing. But it’s one thing to see it; it’s another to feel it. Not just physically, but mentally and emotionally. Let’s talk about that.

ADAM: It’s been a whirlwind. That walk to my neighbor’s house without my stick was one of the longest walks I’ve taken—it was incredible. Being able to golf that day, to support my friend’s family, that was amazing. Even little things, like going to a restaurant and leaving my stick in the car, feel huge. The bartender said, “Something’s different.” I told her, “Yeah, I don’t have my stick.” She said, “What? I’ve never seen you without it.” Those small moments are amazing. Same thing when I walked into the store without my stick—it’s the little victories.

ADAM: (continued) They also have a cycling mode. At first, it only engaged my quads and hamstrings, not my feet, which I needed, so they adjusted it. I told them what I needed, and they listened. That’s one of the best parts—they care. I post about it, and the founder comments personally. They engage and support their users.

ALLIÉ: The way it should be. Finally, it is.

ADAM: Exactly. I’ve been talking about it a lot. I know at least six or seven people in the MS community who’ve gotten them now. Whenever I’m online, that’s the first thing people ask me about—the sleeves.

ALLIÉ: It’s absolutely amazing. You’ve said that with the sleeves, you’ve been able to bike six miles, golf, and do things that once felt impossible. What goes through your mind when you’re out there moving freely, doing something MS once took from you? What’s Adam’s heart saying to that?

ADAM: I feel amazing. It honestly feels like I got pieces of my life back. Things I never thought I’d do again, I’m doing. It gets my mind spinning—what else can I do? How much more can I walk? At next year’s Walk MS, will I walk the whole mile without my sticks? I’m always asking, what’s next? Let’s keep pushing and show others that there’s something out there that can help them. If I have to be the mouthpiece for that, I’m all for it. I love that.

Exclusive Interview with Adam Powell https://awarenow.us/podcast/wearing-your-hope-on-your-sleeves

ALLIÉ: I can’t think of a better mouthpiece than you, Adam. You’re not just wearing technology—you’re wearing hope. For those who feel stuck in the symptoms of MS and unsure if progress is possible, you’re living proof. If you could look them in the eyes and tell them something about why it’s worth trying, what would you say?

ADAM: It’s the same message I always share: just do something. Try to be a little bit better than you were yesterday, no matter what that looks like, no matter what stage you’re in—because I’ve been in all of them. If you can’t do sit-tostands and you do one, that’s a huge win. Tomorrow, do two. If you can’t straighten your leg, and you do, that’s a win. Keep trying to be a little better tomorrow than you were today. It’s that simple. It’s hard, but it’s simple. You have to have the mindset before you can do it physically. I say that from experience. When I was learning to walk, I was hunched over a walker, braced from thigh to toe, throwing one foot in front of the other and hoping it landed right. I just kept repeating that for years, and now I can walk. The sleeves are just an addition to that hard work. I put in the years, and now I’m taking pieces of my life back. It’s incredible.

They’re actually comfortable. I barely know I’m wearing them. The battery pack is small, lasts about eight hours, and clips to your thigh. It’s amazing. I can’t say enough about it. Like I said, I’m always wondering what else I can do now, how much more I can push. I’m still fine-tuning everything—getting the electrodes in the perfect spot and figuring out what works best for me. It’s so user-friendly. You can control everything from an app on your phone and change it whenever you want. It’s awesome.

ALLIÉ: With MS, we’re always looking for new tools. It’s not curable yet, but until it is, we manage what we can—and find the tools that help us do it better. This is clearly one of those tools. It’s worked for you and could for so many.

ADAM: I hope so. I remember one guy at the conference—probably in his early sixties, diagnosed only a few years ago—his foot didn’t lift off the ground when he walked. It dragged every step. He tried the sleeves, and suddenly he was walking almost normally. He looked at me, almost in tears, and said, “I haven’t walked like this in years.” That’s what it’s about—getting that sense of normalcy back, being able to do what we used to do. I never thought I’d be able to do this. No way.

ALLIÉ: And yet you can—and you are.

ADAM: And I plan to keep going. ∎

What happens when one man refuses to accept the limits society places on others? For Jake Weiner, that question became the catalyst for ZOOZ Fitness—a space where people of all abilities are not only welcomed but celebrated. In this conversation, Jake opens up about the personal journey, the challenges, and the humanity behind creating an inclusive fitness revolution that’s transforming lives and reshaping an industry.

ALLIÉ: Every moment can begin a movement. What was your moment, Jake—the one that made you realize that the fitness industry wasn’t just overlooking people with disabilities, it was leaving them behind—and that you had to do something about it? What was that moment?

JAKE: I want to rewind slightly because I think it helps pave the roadmap to that moment in particular. I grew up doing martial arts and sports, so movement has always been a part of my life. Movement is medicine, and I was taught at a very young age that we should move—and move often. I have two brothers, so we were always sporty and active. A love of movement and exercise and building community around that was instilled in me early on.

“For me, I had a deep passion for fitness and for helping people who were being left out of that world.”

JAKE: (continued) running through all of it: I kept noticing that the people I worked with weren’t active. They weren’t moving their bodies. So it wasn’t just that the fitness industry wasn’t inclusive—it was that these individuals weren’t being given opportunities to move at all. That was the lightbulb moment. All of my experiences came together, and I realized there was a need. They weren’t accessing the gyms I was, or the sports that gave me so much life. And that was the aha moment when I thought, something needs to happen. Who’s going to do it? Me.

ALLIÉ: Founding something as unique as ZOOZ couldn’t have been easy. Let’s to back to the start. What doubts or barriers did you face, and how did you find the strength to keep going when it felt like the world wasn’t quite ready?

JAKE: I think with any entrepreneur, there are tons of doubts and anxieties—imposter syndrome, the whole thing. I can remember vividly when I had that aha moment. I was sitting with my wife and my family, saying, “I think I want to start something like this.” I didn’t know what it would be called or look like yet, but I knew I wanted to work with this population.

My family and friends kept saying things like, “There aren’t enough clients for you,” or, “The population’s not big enough,” or, “I don’t know if these folks can work out.” There was just a lot of doubt—not about the people themselves, but because fitness and disability didn’t seem to merge in people’s minds. So as a hopeful business owner, I wondered: Can this work? Can I make a living? Will there even be clients? It definitely wasn’t easy, but I’ve always liked to reframe things. I love perspective—seeing things through someone else’s eyes. For me, I had a deep passion for fitness and for helping people who were being left out of that world.

Even when things got tough, I kept coming back to that. COVID was one of those moments. In 2019, we opened our first brick-and-mortar gym. Then in 2020, COVID hit—and I also had my first son. It felt like the universe was testing me. But I stayed focused. For me, it’s all about mindset. I was determined to make this happen and ensure that our mission came to life. Someone had to lead the ship.

ALLIÉ: Yeah—if someone was going to step up and actually do it. From what I’ve read and seen, ZOOZ isn’t just about building muscle; it’s about building confidence, connection, and community. Can you share a moment or story from the gym that captures what inclusion really feels like?

JAKE: There are countless stories. The biggest one for me happened recently during our second Spartan Race. We took 11 athletes and 16 coaches. One of the athletes had only been training with us for a few weeks. On the course— a 5K in the desert, full of obstacles and heat—he had a moment of panic. He was overwhelmed, saying, “What am I doing out here?” My coaches and I talked him through it. At the end, he came up to me and said, “Thank you so much for this experience, but also thank you for having ZOOZ Fitness. Thank you for making a place where I can feel included—where I don’t have to be worried about my anxieties or stressors.”

He also struggles with anxiety in public places, like malls. ZOOZ became a space where he feels safe, confident, and connected. These events—like Spartan races—aren’t built for folks with disabilities. Yet there he was, completing one. That’s inclusion to me: creating spaces that weren’t made for our athletes and making them accessible, not because they can’t do it, but because they can when given the right support.

JAKE WEINER FOUNDER OF ZOOZ FITNESS

ALLIÉ: Absolutely. And inclusion can mean so many different things to different people. So, let’s talk about another word—athlete. It carries so much cultural weight. How have your athletes at ZOOZ redefined that word for you, and for everyone who steps through your doors?

JAKE: Words are powerful. When I started ZOOZ, the term client didn’t sit right with me. It felt transactional. I wanted something empowering. The word athlete does that. When people hear it, they might picture a professional, someone who’s fit, fast, and strong. But to me, an athlete is anyone who works hard, who shows up, who moves their body with intention. When we call our participants ‘athletes’, something shifts. They start believing it. They carry themselves differently. Their parents hear it and see it too. It’s a mindset—yes, you’re athletic, yes, you’re strong, yes, you’re capable. That’s powerful.

I’ll share a quick story. About eight years ago, I was at a resource fair talking to parents. A father came up to me and asked, “Do you train professional athletes?” I said, “No—but here’s how we define athlete.” I explained that everyone who works hard and moves with purpose is an athlete. He paused, thought about it, and said, “So if I trained with you, I could be an athlete too?” His face lit up. He had a son on the spectrum, and it was a moment of realization— that inclusion through language can be transformative.

ALLIÉ: That’s such a good point. We talk about the boxes society puts us in, but rarely about the ones we can check for ourselves. I did some research and saw that you have a background in psychology, marketing, and judo—a fascinating combination. How do all those disciplines come together in the way you train, motivate, and empower your athletes?

JAKE: ZOOZ has grown so much. I started it over ten years ago with just me and an idea. Now we have an incredible team that’s taken it further than I ever imagined. Early on, it was about two things: movement and community. Those two words are still the foundation of everything we do.

The psychology background helps with understanding behavior and motivation—how people change, what drives them. Marketing taught me how to communicate and connect. And judo taught me discipline, respect, and how to fall and get back up. Those lessons come together in how we coach. Our number one goal is positive movement. Every new athlete and every new coach hears that from day one. We want every experience to be positive. I’ve been lucky to have amazing coaches in my life. My dad was my judo instructor—which came with its challenges—but he taught me about community, consistency, and grit. That’s stayed with me for more than a decade of running ZOOZ.

ALLIÉ: That’s amazing. It’s clear that ZOOZ is more than a gym—it’s a movement. What’s the most surprising or humbling impact you’ve witnessed as your community has grown?

JAKE: Honestly, I’m always amazed that we keep getting referrals. That might sound strange, but it’s humbling. Every time a parent tells another parent, or an athlete brings a friend, it reminds me that we’re making a real impact. The bottom line for us isn’t profit—it’s people. We’re expanding into a larger space right now because of our waitlist. It’s bittersweet—it’s wonderful that so many people want to join, but it also means I can’t help everyone immediately. Every gym should be inclusive, but that’s not yet reality. Until it is, we’ll keep doing what we do—growing, adapting, and making room for everyone who wants to move.

ALLIÉ: What does it do for you personally to see someone go from “I can’t” to “I can”?

JAKE: It’s the greatest feeling in the world. I always say this isn’t a job—it’s a calling. If someone offered to buy my business for a hundred million dollars, I’d probably say, “Can I still work for you?” because there’s nothing else I’d rather do. I get to live my passion—to move, to teach, to inspire—and also support my family. That’s everything.

Exclusive Interview with Jake Weiner https://awarenow.us/podcast/beyond-the-barriers

JAKE: (continued) Every day, I see victories. A new box jump. An added five pounds on a sled push. A 90-second dead hang. Those moments of progress—big or small—are everything. I leave every day with gratitude. I remind our coaches that this isn’t just work. It’s purpose. Every session is an opportunity for someone to win.

ALLIÉ: Yeah—and even the smallest wins can mean the most. If the entire fitness industry were listening right now, what would you say to them about inclusion—what it really looks like, and why it matters?

JAKE: Great question. I think a lot of people get inclusion wrong. For us, it’s simple: everyone should have access to everything. The words no and can’t don’t exist at ZOOZ. I tell our coaches that it’s our job to figure out what each person needs in that moment. That might mean adapting equipment, changing the coaching style, or creating a new way entirely.

That’s where many fitness professionals miss the mark. Inclusion isn’t about lowering expectations—it’s about raising creativity. Every athlete is different. Even the same athlete can have different needs day to day. So it’s about being present and making movement accessible for everyone. ∎

When we talk about equality, we often forget one of its biggest missing pieces: disability. For many, ableism is a word they’ve never heard, yet it shapes how millions of people live, work, and are treated every single day. Today, I’m sitting down with Celia Chartres-Aris and Jamie Shields, two unapologetic truth-tellers who are breaking the silence and giving us the language—and the courage—to finally unlearn ableism.

ALLIÉ: For those who don’t yet have the pleasure of knowing you, please introduce yourselves in your own words.

CELIA: Hi, I’m Celia Chartres-Aris, pronouns she/her. I wear many hats, but one of the biggest is as one half of Disabled By Society with Jamie. We’re a 100% disabled-owned and disabled-led organisation working around the world to dismantle ableism across governments, private companies, and the charity sector. We do this through training, auditing, consultancy, and research. We also host the award-winning podcast Unlearning Ableism and lead projects focused on embedding inclusion in policy and culture.

Right now, we’re here because of our upcoming book, Unlearning Ableism, a collaboration of our work and the voices

JAMIE SHIELDS CO-AUTHOR OF UNLEARNING ABLEISM

JAMIE: I’m Jamie Shields, pronouns he/him, the other half of Disabled By Society. I’m registered blind, autistic, and ADHD, and I’ve spent my life disabled by society. I struggled for years to find employment, then somehow ended up in recruitment—hiring others when I’d always been the one turned away.

I went from headhunting to leading a global disability and accessibility network. That shift happened through lived experience—realising I wasn’t alone. I’m also a content creator, which is how Celia and I met through the first UK LinkedIn Creator Programme.

It wasn’t love at first sight—it was bestie at first sight. She was the yin to my yang, the person I could say the unsayable to. Together we wrote Unlearning Ableism: The Ultimate No-Nonsense Guide to Understanding Disability. Two and a half years later, our baby is almost here.

ALLIÉ: We grow up hearing words like racism and sexism, but ableism still stops people mid-sentence. If someone hears that word for the first time, how would you describe what ableism feels like—not as a definition, but as a lived experience?

JAMIE: It’s alienating, frustrating, and disappointing. When we talk about isms, we understand what racism and sexism mean because we’ve been taught about them. But no one teaches us about ableism, even though disability is the one group anyone can join at any time.

We’re all one accident or diagnosis away, yet society ignores it. Ableism isn’t one incident—it’s a constant thread. It’s the barriers, the backhanded compliments, the “you’re amazing for doing that” comments. It’s the missing ingredient in every inclusion conversation.

CELIA: I echo that. I’d also say it’s upsetting. When I share that I have a terminal illness and I’m in multiple-organ failure, people instantly give me pity—and in the same breath, they’ll say something deeply offensive without realising it. It’s that clash: sympathy on one side, prejudice on the other. Together, those two things other you completely. You stop being seen as human.

What’s most painful is that I expect it now—and I’m surprised when it doesn’t happen. That’s how far we have to go. When people say “reasonable adjustments,” I ask, “What’s unreasonable?” We thank people for giving us our rights when we shouldn’t have to.

If you’re unsure what ableism looks like, try this: replace the word disability with race or gender in whatever you’re about to say. Would you still say it? If not, that’s ableism.

ALLIÉ: You’ve both talked about the silence that allows ableism to keep spinning. What was the moment that turned quiet frustration into action—the moment you said, enough?

CELIA: Mine came when I switched careers. I trained in law and had a job offer rescinded after disclosing my chronic health condition. It was a human-rights law firm, which made it worse. They told me I “wouldn’t be a good fit” now that they knew about my personal challenges.

I’d been bedridden for nearly two years and it had taken everything to apply. That call broke me—but it also lit something. My friends said, “Use that anger.” And I did. If that hadn’t happened, I’d still be in law. It was my “enough” moment—the one that changed everything.

JAMIE: For me, I hit rock bottom. I bounced from job to job, labelled needy or dramatic when I asked for support. On paper, it looked like I didn’t care about my career, but the truth was I just wanted to be accepted.

CHARTRES-ARIS CO-AUTHOR OF UNLEARNING ABLEISM

JAMIE: (continued) I sank into depression, internalised ableism, and shame. When I lost the job I’d held the longest, I felt worthless. My partner told me, “It’s not you—it’s them.” That sentence saved me. Eventually, I found an employer who said, “What can we do to support you?” instead of “You don’t fit.” That moment changed everything. It reminded me that anger can fuel change.

ALLIÉ: The book invites people to shake things up, but that can make others uncomfortable. When someone says, “I didn’t mean it that way,” how do we move conversations from defensiveness to discovery?

JAMIE: That’s where unlearning starts. We’re not teaching people to be anti-ableist overnight—we’re helping them see that their “good intentions” can still cause harm.

We’ve all learned certain ways to speak about disability from society. Unlearning means accepting that we’ll get it wrong sometimes and being willing to do better.

It’s not about blame—it’s about awareness. In the book, we share humour and honesty because this isn’t about shame; it’s about shifting perspective. When you start to see disability as part of the human experience—not an exception—you begin to unlearn ableism.

CELIA: Exactly. We chose the word unlearning because this isn’t about acquiring new information—it’s about letting go of old conditioning. Since ancient times, societies have seen disabled people as weak or lesser. That’s why we think the way we do.

It’s not your fault, but it is your responsibility to unlearn it. Our book takes readers on that journey—understanding where these ideas came from, what they mean, and how to replace them with empathy and intention.

We also knew our own voices weren’t enough. Jamie and I are both white and live in a country with healthcare access many don’t have. So we invited 37 contributors from around the world to ensure real intersectionality.

No two disabled people are the same. Inclusion isn’t a five-step checklist; it’s individual and human.

ALLIÉ: You both talk about giving people permission—to get it wrong, to learn, to feel.

JAMIE: We’re human. We learn through mistakes. Even as disabled people, we don’t get a handbook. We only recognise ableism after we’ve lived it long enough to feel the toll it takes.

Unlearning Ableism helps people see that internalised ableism can be trauma. It’s the voice that says, “I’m not enough.” The book walks readers through awareness, action, and change—chapter by chapter. You can pick it up anywhere and walk away more confident than you were before.

We’re not here to name and shame; we’re here to celebrate growth and progress, one choice at a time.

CELIA: And it’s also a book for disabled people themselves—to feel seen and supported. Having Jamie in my life changed mine. I was advising prime ministers on inclusion while mentally tearing myself apart at home. He helped me unlearn that self-punishment.

We wrote this book so disabled readers could hear our friendship in its pages—a safe space where you’re allowed to cry, to get angry, to stop pretending it’s easy. It’s not about loving every part of disability—it’s about finding pride in identity, even when it’s hard. If I could wave a wand and cure my illness tomorrow, I would. But that doesn’t mean I’m not proud of who I am.

ALLIÉ: Before the book is out, there are people listening who want to be allies but don’t know where to begin. What’s one small act anyone can do today to start unlearning ableism?

JAMIE SHIELDS CO-AUTHOR OF UNLEARNING ABLEISM

Exclusive Interview with Celia Chartres-Aris & Jamie Shields https://awarenow.us/podcast/unlearning-ableism

CELIA: Listen to disabled people. That’s the first step. Whether online, in your organisation, or through books—hear our voices before you speak for us. There’s a fine line between allyship and taking up space. Be an ally, but when it’s time to pass the mic, let go of it.

During the London 2012 Paralympics, the marketing campaign called athletes “superhuman.” Many thought it was empowering, but it wasn’t—it othered us again. Nothing about us without us. So start with listening.

JAMIE: I love a quote Celia always says: “Start by doing what’s necessary, then do what’s possible, and suddenly you’re doing the impossible.” Start by learning. Connect with disabled creators. Read. Reflect. When we include disabled people, we build a better world for everyone. When I was a kid, I wanted to be a fireman. (You can’t be a fireman when you’re blind—thanks, Fireman Sam!) I never imagined I’d co-found a company or write a book. But here we are, proving that what once seemed impossible is not.

ALLIÉ: You’ve said, “Disabled people are not unicorns who appear during a full moon.” When you imagine a world where ableism has been unlearned, what does that look like?

JAMIE: It’s a world without barriers. A world where my nephew, who shares my condition, can apply for jobs or navigate websites without obstacles. It’s a world where we can share our experiences without fear or shame—a world of freedom and expression. Our job is to make ourselves redundant—to make this work unnecessary because accessibility has become instinctive. That’s the dream.

CELIA: For me, it’s a world where you don’t wake up wishing you could peel yourself out of your body and live as someone else. It’s where disability is no longer seen as tragedy or heroism, but simply humanity. Where we stop saying “differently abled” and start saying “disabled” without shame. Accessibility isn’t a privilege; it’s a human right. I want a world where we don’t have to fight to stand on the same pitch, where inclusion is the baseline, not the battle.

JAMIE: A world where we don’t have to be thankful for meeting the bare minimum. Where getting an accommodation at work isn’t something we feel grateful for—it’s just normal. ∎

Learn more about Ceila & Jamie’s work online: www.disabledbysociety.com Want the book? Of course you do… Get it here: https://awarenow.us/book/unlearning-ableism

October is Blindness Awareness Month, a time to educate, advocate, and celebrate the capabilities of people who are blind and visually impaired.

The truth is, the world wasn’t built with us in mind, but we continue to navigate, innovate, and thrive within it. Advocacy matters because awareness leads to understanding, and understanding leads to inclusion.

Yes, blindness presents challenges, but it doesn’t define who we are. We read using braille, large print, and audio. We enjoy accessible games like braille UNO, Monopoly, and Scrabble. We compete in sports such as goalball, blind soccer, and beep baseball. In the kitchen, braille measuring cups and talking thermometers help us prepare meals independently. And with today’s technology, smartphones, computers, and screen readers, we can access information, communicate, and create just like anyone else.

The resources available to our community are incredible, but advocacy is how we ensure more people know they exist. When we amplify access, we empower independence.

Blindness Awareness Month is a reminder that we all have a role to play as allies, educators, and changemakers in building a world where everyone, regardless of sight, can live boldly and freely. ∎

LEX GILLETTE x Paralympic Medalist, 4x World Champion & Keynote Speaker www.awarenowmedia.com/lex-gillette

LEX GILLETTE has quickly become one of the most sought after keynote speakers on the market. Losing his sight at the age of eight was painful to say the least, but life happens. Things don’t always go your way. You can either stay stuck in frustration because the old way doesn’t work anymore, or you can create a new vision for your life, even if you can’t see how it will happen just yet. His sight was lost, but Lex acquired a renewed vision, a vision that has seen him become the best totally blind long and triple jumper Team USA has ever witnessed.

ROXANNE MESSINA CAPTOR WRITER, DIRECTOR, PRODUCER & FILMMAKER

In a world that often confuses power with permanence, Roxanne Messina Captor reminds us that true influence is measured in impact, not applause. An Emmynominated writer, director, and producer—and a three-time breast cancer survivor—she has spent her life turning challenge into creation, and policy into possibility. From mentoring under Francis Ford Coppola to leading California’s arts movement as Chair of the California Arts Council, Roxanne continues to prove that when creativity meets courage, culture changes.

ALLIÉ: You've influenced California's creative landscape in ways few others have, bridging art, policy, and storytelling. Roxanne, when you think about what fuels your creative drive after decades in this industry, what remains your why?

ROXANNE: Well, I think you said it—storytelling. Above and beyond, every project has a story that needs to be told. I tend to always be attracted to what's underneath, because we see things on the surface, and what is on the surface is not always what lies beneath. Thematically, I think most of my projects search for that. What is really going on? What

ROXANNE MESSINA CAPTOR WRITER, DIRECTOR, PRODUCER & FILMMAKER

“When you face breast cancer—especially more than once—you realize that passion, resilience, and perseverance, the same qualities that make you an artist, are the ones that get you through it.”

ROXANNE: (continued) I was talking to somebody about M3GAN, and I said, yeah, I'd love to do a sci-fi kind of thing but character-driven like that was. You had these two AI characters, but they were real characters—they had arcs, highs, and lows. That's what drives me. Then the project finds its home. Certain projects should be theater, others film, others television. Now, fortunately, we have this great medium of streaming—a cross between TV and film— which is why we see so many actors making that shift. It’s fantastic because it's all art. When I was head of the San Francisco International Film Festival, we did an exchange with the Cuban Film Festival. What was amazing there was Fernando Birri, the father of Latin American film. He's well-known as a filmmaker, but he had a gallery opening of his artwork and paintings. In the United States, we tend to put people in little boxes. It was so rich to see that he’s just an artist—not just a filmmaker, not just a painter, but an artist. At different times in your life, you want to explore your creativity in different mediums. That’s the exciting part—constantly creating and letting that mind-body experience out.

ALLIÉ: That's so beautiful—the way you speak about creativity as an evolving ecosystem where expression isn’t confined to a single channel. As chair of the California Arts Council, you’ve helped shape how creativity sustains the state’s identity and economy. What do you believe policymakers often overlook about the real power of the arts, and how are you working to change that narrative?

ROXANNE: Great question. I’ll start with a slogan I’ve used many times: Let’s put art in the hands of children, not guns. I used that in a series I did called The Salon, which was set in a hair salon full of great characters. Harry, one of the characters, was a ghost who comes back to the salon and causes havoc—but the show also carried a theme of gun legislation. So it had this balance of lightheartedness and depth—what some call dramedy—with a deeper message. Again, I’m always looking for what’s underneath. We’re fortunate to have an amazing governor, who appointed me to the Arts Council, and he is passionate about art. He believes, as I do, that art is the great equalizer— that it serves and unites communities. I can give two examples. First, one of my films premiering at the Newport Beach Film Festival, Rhythm and Harmony, studies famed jazz musician Stanley Clarke and his three-year residency at Santa Monica College. I was able to include some of my students in the production. In the film, Stanley says, Art is a great equalizer. I believe that completely. When I was dancing and in theater, we used to go into underserved communities to do performances and workshops. We’d get all the students up to dance or play theater games. Teachers would tell us, “You did more in 40 minutes to break down barriers than we’ve done all year.” That’s the power of art. It transcends everything… borders, politics, even war. If more Washington politicians understood that, we might have fewer wars. There’s too much ego.

ALLIÉ: I completely agree. Let’s shift gears to something more personal. You’ve faced breast cancer three times, yet your creative output never stopped. You once told your doctor, “I don’t have time for cancer.” What did those moments teach you about purpose, perspective, and the urgency of art?

ROXANNE: When you face breast cancer—especially more than once—you realize that passion, resilience, and perseverance, the same qualities that make you an artist, are the ones that get you through it. And I used humor a lot. When I got it the second time, I said, “If this were a TV series, it would’ve been canceled years ago.” My doctors and nurses knew me as the no time for cancer lady. I had a green light on a CBS movie and was writing a series I had sold to ABC—I didn’t have time! I’d be working from the hospital with my computer and papers everywhere. The nurses

ROXANNE MESSINA CAPTOR WRITER, DIRECTOR, PRODUCER & FILMMAKER

“When I read a script, I see it. When I listen to music, I see it. So his advice to tell the story through images became foundational for me.”

ROXANNE: (continued) would come in and say, “Are we disturbing you?” I’d say, “Yeah, you were supposed to take care of me an hour ago. I’m busy now.” My doctor told me later, “Your attitude got you through it.”

I had an amazing oncologist, Dr. John Link—world-renowned, a researcher, and a compassionate listener. When I told him I wanted a holistic approach, he said, “Okay, I have an acupuncturist and homeopath on staff.” He didn’t dismiss me—he worked with me. I told him from the beginning, “I’ve had a great life. If you tell me I’m dying tomorrow, I’ll deal with it.” One night, the chemo cocktail had me hallucinating. At 3 a.m., I was shaking my husband, yelling, “How much money do we have? I want my half now! I’m moving to France to drink wine and eat great food.” He’d calmly say, “Okay, honey, can you wait until morning when the banks open?” (Laughs.) That’s how I coped—humor and gratitude.

I’ve since helped other women navigate treatment and insurance. Once, I met a woman in tears because her insurance wouldn’t cover more chemo. I told her about legal advocates for breast cancer patients, called for her, and got her connected. You have to advocate for yourself—and for others when they can’t.

ALLIÉ: Such a powerful reminder—sometimes advocacy for others becomes part of our own healing.

ROXANNE: Exactly. And I have to give my husband credit. When I was running the San Francisco International Film Festival, we used to go to Cannes. One year, he surprised me with a trip through southern France—Lyon, the wine regions—all my chemo dreams come true. (laughs) And I didn’t have to wake him up at 3 a.m. that time!

ALLIÉ: You could toast him until 3 a.m. instead. I love that. You were mentored by Francis Ford Coppola, one of the greatest storytellers of our time. What was the most valuable lesson you took from that mentorship, and how has it shaped the way you mentor the next generation?

ROXANNE: He taught me that filmmaking, like dance, is a mentorship art—you learn from masters. He’d always say, Plays are words. Film is moving pictures. That stuck with me. As a dancer, I was already visual. When I read a script, I see it. When I listen to music, I see it. So his advice to tell the story through images became foundational for me.

He also taught me perseverance and resilience—two things essential in this industry. The path isn’t linear. It’s full of highs and lows. Passion is what sustains you. I tell my students, the résumé might look impressive, but what’s behind it hasn’t been easy. You have to love it enough to endure the journey. I was honored to receive the Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres from the French government for my work in the arts—because that’s what I am, an artist. And when you’re an artist, you have to keep creating. It’s like popcorn—it brews inside you until it bursts out.

ALLIÉ: I love that metaphor—the art that’s waiting to pop. And you’re right, passion can’t be substituted. You either have it or you don’t.

Exclusive Interview with Roxanne Messina Captor https://awarenow.us/podcast/the-art-of-resilience

ROXANNE: Exactly. There’s a great line from Peter O'Toole: “I’m not an actor, I’m a movie star.” Some people are obsessed with the red carpet and forget what it takes to get there—all the unseen work underneath it.

ALLIÉ: That brings us full circle—back to what’s beneath the surface. Speaking of which, one of your new films, Rhythm and Harmony, explores rhythm, legacy, and the language of music. How do you personally define harmony— in life, leadership, and art—especially in these chaotic times?

ROXANNE: Gene Kelly once told me, Always balance your personal life with your work life. It’s not easy—especially when you’re passionate—but I try to keep that advice in mind. To me, that’s harmony. And Stanley Clarke says in the film, Art is a great equalizer. I’ve always believed that. Whether through music, dance, theater, or film, art brings people together. It dissolves barriers. When I was dancing, I could walk into any class anywhere in the world and feel at home. We all spoke the same language. That’s harmony—no borders, no divisions. I wish Washington would figure that out. (laughs)

ALLIÉ: They all need to get into a dance class together!

ROXANNE: Maybe! Though the visuals might be terrifying. (laughs)

ALLIÉ: Last question—having survived, led, and created through so many chapters of your life, what does beauty mean to you now—not as something seen, but something lived?

ROXANNE: Wow, that’s a great question. I think beauty is when you let your soul out. When your soul shines through, it shows in your face, in your movement, in your presence. Dance embodies that mind-body connection—and when your soul is fully expressed, you can feel it and others can too.

That connection between artist and audience… that’s beauty. ∎

JACK MCGUIRE CO-FOUNDER OF AWARENOW MEDIA

ORIGINAL POEM BY JACK MCGUIRE

Not drinking is hard.

Healing is hard.

Growing is hard.

Being emotionally strong is hard.

Owning my mistakes and forgiving others is hard.

Being a parent is hard.

Some days, just waking up is hard.

Communicating is hard.

Being the example I want my kids to follow is hard.

Showing up for everyone all the time is hard.

Letting myself cry is hard. And yeah… not having that drink is still hard.

But here’s the truth— The ‘hard’ is where the wins are.

Not drinking means I’m choosing to live longer for my kids and my wife.

Healing means I’m breaking cycles instead of repeating them.

Learning to express my emotions means I’m not letting pain control the room. Forgiving means I’m setting myself free.

Parenting—while still hard—is the most rewarding fight I’ll ever show up for.

So yeah, life’s hard.

But I’m done focusing on the weight of it.

I’m choosing the worth of it.

Because in a world full of hard things… I choose to see the good. I choose to fight forward.

I choose to stay aware. I choose the positive view. I choose love.

Sina Sinbari’s story is not defined by what cancer took from him but by what it gave him: perspective, purpose, and an unshakable faith in resilience. In the midst of hospital stays, loss, and relentless treatments, he discovered that battles can hold unexpected blessings. Today, he shares how struggle became the canvas for strength and hope.

ALLIÉ: Nobody forgets the day they hear the words, "You have cancer." Sina, to start us out, tell us about your life before the diagnosis and what happened leading up to that day.

SINA: Sure. I’m from Laguna Niguel, Southern California, and I basically had a normal lifestyle. I was in high school and hoping to play volleyball at the highest level in college. Before, I was more of a student-athlete. After high school, I went to community college, played there for a year, and then transferred to the University of Charleston in West Virginia. When I was home for the summer, I was training a lot. I had a bit of a chip on my shoulder because I was transferring to a new school and wanted to do great things—to finally have my opportunity to play, make my family proud, and make myself proud. I was really excited for that next chapter.

I live-streamed her funeral from the hospital that day. I was 21.

SINA SINBARI COLLEGIATE ATHLETE, CANCER SURVIVOR & AWARENOW AMBASSADOR

Courtesy:

ALLIÉ: And then something happened—something didn’t go according to plan. Take us through what happened. How did you end up getting this diagnosis?

SINA: That’s a great question. I started having a lot of back pain once I came home for the summer. I was in the transfer portal, had committed to Fairleigh Dickinson University, and was super excited. I came home ready to train, but my back kept hurting—really bad pain that wouldn’t go away. I was still lifting, playing, going to the beach—but it just kept getting worse. I tried everything: rehab exercises, physical therapy, ibuprofen—nothing worked. It got to the point where I’d take four or five ibuprofen just to sleep at night. That’s when my family and I knew something wasn’t right. A physical therapist finally said, “You should probably get this checked out.” They thought it might be a cyst or hernia. But when I went to the emergency room, everything changed.

ALLIÉ: And that’s where the diagnosis came in. What was the exact diagnosis?

SINA: At first, they had no idea what kind of cancer it was. I went to the ER by myself, thinking it was just my back. When the doctor saw me, he immediately knew it wasn’t a hernia or cyst—it was something much more serious. He told me, “I’m sorry, but it’s cancer. We just don’t know what type.” They kept me in the local hospital for a few days for biopsies, but they couldn’t determine the exact type. They thought it might be lymphoma, but it wasn’t. Once UCLA doctors reviewed my scans and labs, they identified it right away—a very rare form of sarcoma called desmoplastic small round cell tumors. Only about 36 people a year get this diagnosis. I couldn’t even pronounce it at first. I’d never been hospitalized before—not even for a broken bone. So to hear that I had a rare, aggressive cancer was surreal. It took about two weeks from hearing “you have cancer” to knowing exactly what kind it was.

ALLIÉ: That’s wild. And the fact that you went to the hospital by yourself, just to get your back checked out, and all of a sudden you hear the C-word—alone.

SINA: Yeah.

ALLIÉ: I noticed something when you said “they looked at our scans.” I love that—that sense of community and care. Speaking of that, you and your grandmother shared something deeply emotional—being in the same hospital at the same time. Your mom had her son on one floor and her mother on another. What was that like for all of you?

SINA: It was definitely an interesting and emotional time. I was very close with my grandma—she was always there for us, like most grandmas are. She had gotten sick around the same time my back pain started, and she was actually admitted to the hospital just a few days before I went to the ER. She was on the first floor, and when I was admitted, I was on the third. My mom would visit her on one floor and then come see me on another.

When I was discharged, I went down to visit her, and she said, “I miss you, where have you been?” I didn’t want her to know about my diagnosis—she was already sick, and I didn’t want her worrying about me too. So I told her I’d just been busy with volleyball. After a few days, she went home, and so did I. But she entered hospice shortly after. I was upstairs in my room recovering, and she was downstairs in hospice care. It was a strange and heavy time—balancing my diagnosis with her decline. She passed away shortly after I started my first round of chemotherapy—in fact, I began chemo the same day as her funeral.

That was hard. I wanted to go to the funeral, but mentors and friends told me what she would’ve wanted—for me to start treatment immediately. So that’s what I did. I had long hair back then, and before treatment, I told my dad to buzz it off—a mental preparation for the battle ahead. I live-streamed her funeral from the hospital that day. I was 21.

ALLIÉ: That’s a lot to carry—your first chemo treatment and your grandmother’s funeral. You told me once you spent 185 days in the hospital that year. I imagine that gave you a lot of time—and a lot of perspective. Tell me about one of those moments—the nine-year-old boy you’ll never forget.

Every round of chemo felt like two steps back, one step forward.

SINA SINBARI COLLEGIATE ATHLETE, CANCER SURVIVOR & AWARENOW AMBASSADOR

“He reminded me that even in hard times, we can be light for someone else. I still think of him when I want to quit —he motivates me to keep pushing.”

SINA: Yeah, that was Zaya—they called him Z. I was on the pediatric floor at UCLA, even though I was older, because my oncologist led the pediatric department. Z was nine and struggling—he didn’t want to take his meds, didn’t want treatment. One day, the nurses asked if I’d talk to him. I said absolutely.

He loved Stranger Things, which was a little scary for me, but I told him, “If we walk a few laps around the floor, I’ll watch an episode with you.” That got him moving. The nurses were so happy—he started cooperating, taking his medicine, and opening up. We became friends. Even after I finished treatment, I’d visit him, sometimes bringing friends who’d play music or make him laugh. He loved football, so I asked some of my old teammates to send him videos. Sadly, by the time I brought them, he was in the ICU and unconscious. His mom told me he never got to see them, but she was so grateful.

Going to his funeral—the first of a friend—was tough. But Z changed me. He reminded me that even in hard times, we can be light for someone else. I still think of him when I want to quit—he motivates me to keep pushing.