AWARENOW

THE

WORLD'S OFFICIAL MAGAZINE FOR CAUSES

WORLD'S OFFICIAL MAGAZINE FOR CAUSES

ON THE COVER: CAREY COX PHOTO BY:

SHANI HADJIAN

AwareNow Magazine is a monthly publication produced by AwareNow Media™, a storytelling platform dedicated to creating and sustaining positive social change with content that inspires and informs, while raising awareness for causes one story at a time.

DEBORAH

ADAM

SONJA MONTIEL

LEADING

MYLES FRESNEL, ALEXANDER TAYLOR

RAUL ALVAREZ

DETERIORATING WITH

SYLVIA MIGNON, NSSC

GABY

HELEN

legacy: (n.) a lasting impact that transcends time, built not on what we keep, but on what we give

In the context of the Human Cause and AwareNow, legacy is not about wealth or fame—it’s about the influence we leave for those who come after us. It’s the courage to rewrite broken scripts and the strength to redefine what power and perseverance truly look like. Legacy lives in the choices we make today, the truths we speak, and the paths we clear for others tomorrow.

As we honor those who’ve come before, we must also ask ourselves: what are we building with purpose and intention? In a world that often looks forward without looking back, we must carry our histories as beacons to guide our future.

This month, Pride Month shines a light on the resilience and courage born of the 1969 Stonewall Uprising—a celebration of LGBTQ+ identity, rights, and progress. We also commemorate Juneteenth on June 19, marking the emancipation of enslaved African Americans and honoring a legacy of freedom and resistance. On June 20, World Refugee Day calls us to uplift the stories of those forced to flee persecution and displacement, reminding us of shared humanity and the urgency of global solidarity. And as African‑American (Black) Music Month continues, we honor the rich musical heritage that has shaped culture and culture’s shape, asserting that creative legacy is also a social legacy.

In June, legacy isn’t just a concept—it’s a call to action. It asks us to remember, to celebrate, to stand, and to build. To use the past not as a chain, but as a foundation. To leave behind more than memories—to leave behind momentum for the stories still unfolding.

ALLIÉ McGUIRE

CEO & Co-Founder of AwareNow Media

Allié McGuire began her career as a performance poet, transitioned into digital storytelling as a wine personality, and later produced the Hollywood Film Festival. Now, as co-founder of AwareNow Media, she uses her platform to elevate voices and champion causes, connecting audiences to stories that inspire change.

President & Co-Founder of AwareNow Media

Jack McGuire’s career spans the Navy, hospitality, and producing the Hollywood Film Festival. Now, he co-leads AwareNow Media with Allié, focusing on powerful storytelling for worthy causes. His commitment to service fuels AwareNow’s mission to connect and inspire audiences.

The views and opinions expressed in AwareNow are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official Any content provided by our columnists or interviewees is of their opinion and not intended to malign any religion, ethnic group, political group, organization, company, or individual. Stories shared are not intended to vilify anyone or anything. Their intent is to make you think.

* Please note that you may find a spelling or punctuation error here or there, as our Editor-In-Chief has MS and lost vision in her right eye. That said, she still has perfect vision in her left and rocks it as best as she can.

He

WEED FOUNDER OF THE SELF-WORTH INITIATIVE

BY DEBORAH WEED & NARRATED BY ALLIÉ MCGUIRE

Not everyone gets a Burt Kempner in their lifetime…

He was a wisdom keeper, a story sculptor, and a soul-seer.

Burt didn’t just listen—he heard. He could reach into the raw truth of your story, cradle it like a fragile jewel, and re flect it back as something breathtaking. Not polished to perfection, but burnished with meaning. Braver. Brighter. Real.

He was my mentor, yes. But more than that—he was a sacred mirror.

When I brought him my work, he didn't edit my voice—he amplified my soul.

When I was lost, he didn’t just guide me—he reminded me I already held the compass.

He loved deeply. Quietly. Steadily.

I saw it in how he held space for his wife through her health battles—every gesture steeped in tenderness.

I saw it in the way he continued forward after losing his son—though I know something shattered in him that day.

And now that he is gone, you might expect silence. But no.

There is a whisper that stays.

A whisper that says,

“Keep going.”

“Make it matter.”

“Polish it like the jewel it is.”

That whisper lives in every creative risk I take.

Written by Deborah Weed and Narrated by Allié McGuire

https://awarenow.us/podcast/the-whisper-that-stays

In every moment I dare to speak from the deepest truth.

In every time I ask myself “What would Burt say?”

He may have left the room... but not the conversation.

His words, his kindness, his soul prints— they’re etched into everything I create.

And I will carry him forward—not in mourning, but in momentum.

Because honoring Burt Kempner isn’t about pausing in grief. It’s about creating from it. ∎

Today (and every day), we have gratitude for Burt J. Kempner, a man who brilliantly captured and eloquently explored life with words. Burt was a dear friend who made us all pause with his words and reflect with his voice. He was and is a beautiful light in the constellation of the AwareNow family still illuminates.

Written & Narrated by Burt Kempner

https://awarenow.us/story/in-praise-of-childish-things

DEBORAH WEED

Founder of the Self-Worth Initiative www.awarenessties.us/deborah-weed

Deborah Weed is a whirlwind of creativity and motivation, passionately championing self-worth through her Self-worth Initiative. Her mission? To help families and their kiddos live authentically, energetically, and joyously! Deborah's journey began with a personal crisis: after dazzling in high-pro file roles like working on a $26 million pavilion for KIA Motors and being Citibank's Director of Development, she faced a misdiagnosis that left her bedridden for three years. Her discovery of a 1943 copper penny worth a million dollars turned her perspective around— if a "worthless" penny could be so valuable, so could she! Inspired, Deborah wrote and produced The Luckiest Penny, an interactive musical that teaches kids about self-worth. As a motivational speaker, Deborah brings fun and inspiration to everyone, proving that self-worth is a joyful, transformative adventure.

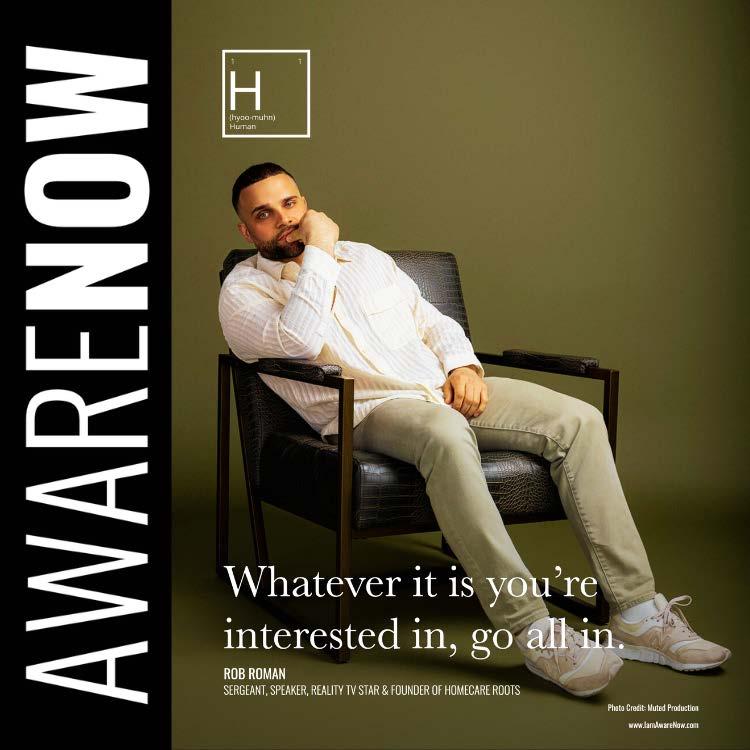

Whatever

it is you’re interested in, go all in.

ROB ROMAN SERGEANT, SPEAKER, REALITY TV STAR & FOUNDER OF HOMECARE ROOTS

There’s reality TV—and then there’s real life. Rob Roman knows both. From Got to Get Out on Hulu to Squid Game: The Challenge on Netflix, he’s proven his grit on screen. But off screen is where his impact truly lives. A decorated Police Sergeant turned founder of HomeCare Roots, Rob provides free, in-home nursing to medically fragile children across Georgia. For the families he serves, Rob isn’t a reality star—he’s their everyday hero.

ALLIÉ: Let's start by rewinding, shall we? Let’s rewind before Hulu, Netflix, and everything in between—growing up in New Jersey. Let’s go there. What drew you to serve your community as a police of ficer and ultimately become the youngest detective and sergeant in your department’s history?

ROB: Yeah, I mean—Jersey. Shout out to Jersey. We love New Jersey. New Jersey has my heart, my soul, my everything. So basically, where I started was fifth grade. 9/11 happened when I was in fifth grade. I was born and raised in a city called Hoboken, New Jersey—right across the river from the Twin Towers. My mom used to take the

If I had a superpower, it’d be my ability to make decisions, take risks, and trust myself.

ROB ROMAN SERGEANT, SPEAKER, REALITY TV STAR & FOUNDER OF HOMECARE ROOTS

ROB: (continued) I remember that day like it was yesterday. My mom picked me up from school very late because she was stuck in New York City. I remember going to the waterfront and seeing the Hoboken police of ficers go back and forth on boats, bringing people back—people covered in blood and everything you can imagine. As a fifth grader, I was just drawn to that. I didn’t know what was going on, but I knew the world was shaken up. I saw those of ficers as heroes. Hoboken was like the center of the world for me that day.

So, I designed my life to work in law enforcement. I graduated with a degree in cybersecurity—Bachelor of Science. I wanted to work for the FBI and do counterterrorism. That was going to be my thing. But I wanted to get experience first, so I started working for my city. And I just fell in love with it. I rose through the ranks quickly because it was my community—I went to school there, played sports there. I knew the city. So yeah, that’s how it all started.

ALLIÉ: Talk about a single day and moment that can change a life—so many lives were changed that day, yours included. Now, fast forward to a different kind of moment on a different kind of day—what was going through your mind walking onto the set of Gotta Get Out as a rookie surrounded by all these reality icons? What was that like?

ROB: Yes, I like to say I was at an advantage—because I didn’t know. I laugh about it now, but I didn’t know who they were. We weren’t told it was going to be half reality stars, half rookies. We were just told: you’re going to walk into this mansion with 19 other people. Good luck. We were kind of given the rules, but I didn’t know I was among people like Spencer Pratt and Val from Dancing with the Stars. I didn’t recognize them because I’d never watched their shows. So to me, they were just regular people.

I found out very quickly—like, after a day—who they were. And it actually ignited me more. I thought, okay, I’m with people who do this for a living. These are seasoned. If I really want to win this money, I’m going to have to earn it. I’m a competitor, so it raised the stakes. But yeah, I didn’t know who they were at first. People laugh now—especially with TikTok—because Spencer Pratt’s all over TikTok with his wife, Heidi. And everyone’s like, “Oh my goodness, Spencer Pratt!” But I just know him as ‘Spence’. He’s not “Spencer Pratt from The Hills” to me.

ALLIÉ: Yeah. At the end of the day, people are people.

Okay, I’m switching gears again. Let’s go to HomeCare Roots. You founded HomeCare Roots with a mission—a powerful one. Can you tell us what led you to start this company and why providing care for children and families means so much to you?

ROB: I want to say first that life is about making decisions. Most people have a lot of ideas but don’t execute. I don’t have anything special about me. I like to say this—I’m as normal as they come. I’m just an average person. But if I had a superpower, it’d be my ability to make decisions, take risks, and trust myself.

This business I started—I love it. It has my whole being. It’s the best thing I’ve ever done. And I’ve done some pretty cool stuff, but this is the best—hands down. It started with a TikTok. Crazy, right?

Long story short, I started making TikToks in 2020 to relieve the stress of law enforcement. I was a SWAT operator for five years. COVID hit. There was a lot going on. I just wanted something fun. That led to You Bet Your Life with Jay Leno—they found me through TikTok. That led to Squid Game. And on Squid Game, I met some of my best friends in the world. One of them was a guy named Brad, who has had a home healthcare agency in Georgia for 15 years. He’s kind of a pioneer—because when you think of home health, you think geriatrics. But he focused on helping children with medical and complex disabilities. For a year and a half, me, him, and two others just traveled the world together. We were inseparable.

One day, Brad said, “You guys should come down to Georgia and start this business. I’ll help you. It’s a lot of paperwork, but I’ll help.” So we did. We took a leap of faith. I left New Jersey. My partner left St. Louis. Our other partner left Canada. The three of us—who met on Squid Game—started this home healthcare agency.

ROB ROMAN SERGEANT, SPEAKER, REALITY TV STAR & FOUNDER OF HOMECARE ROOTS

“You can spiral down—panic attacks, anxiety, depression, alcohol… or you can spiral up.”

ROB: (continued) It’s 100% Medicaid-funded. Medicaid pays our company. We hire nurses who go into the homes of children with medically complex disabilities. Most are non-verbal, wheelchair-bound, suffer from seizures—they have incredibly difficult lives. And the parents, typically moms, are doing everything they can. Just having a child is dif ficult. I know I was a handful for my mom. Now imagine that plus a disability. So, we’re here to help lift that weight. But yeah —it all started with a TikTok that led to Squid Game, and now I’m in a business that feels destined for me.

ALLIÉ: Isn’t it interesting how all these connections come together? Like—Squid Game?! And now this incredible work. I’ll say, I wish I’d known you a long time ago. I’m a mother of six. One of our children had special needs. And I didn’t have the care or support of a program like yours. So let me pause to say, as a mom who knows that world— thank you.

ROB: Yeah, you’re welcome. And people don’t know—most people don’t know this service even exists. Even in Georgia, people don’t realize Medicaid provides home healthcare. I didn’t do it in Jersey because there’s a lot of red tape. I didn’t know how to get started. Brad helped me navigate all that—the policies, the procedures. Now we serve the entire state of Georgia. And every state has something like this. But parents don’t know. It’s hard. When we meet a parent and tell them, “Hey, we’ll send a nurse into your home completely free. Oh, and we’ll pay you to do the work you’re already doing for free”—they don’t believe it. But it’s real. And it’s an incredible service. I just wish everyone knew about it.

ALLIÉ: I do too. I wish I had when I needed it. The fact that you’re doing this work—it’s awesome. Thank you. So, as someone who’s navigated extreme pressure in so many ways—on national television, in the line of duty—how have your experiences in law enforcement shaped the way you lead, serve, and show up for people, whether in the community or on set?

ROB: I’ll say this: my business is my favorite thing in the world. But law enforcement is the greatest career on earth— because it sets you up to navigate the rest of your life, if you do it the right way. I worked for one of the greatest departments in the world. They trained me right. They gave me experiences, mentors.

In law enforcement, you show up to everyone’s worst day. We live in a dark corner of the world. No one calls us to say, “Come to the birthday party.” Every call is someone’s trauma. Five days a week, every week, for 25+ years. So, you reach a point in your career—especially in inner cities—where you have to figure out: How do I navigate this trauma? You can spiral down—panic attacks, anxiety, depression, alcohol… or you can spiral up. For me, I built a toolbox.

Number one is a support system. I have the best parents in the world. I have the best friends in the world. I made sure I attracted those good friends. Number two is therapy. I have an outside person who doesn’t know anything about me and doesn’t judge me. And I just talk to that person. Number three is faith. I’m a Christian. I go to church every week. I read the Bible. I didn’t become a Christian until I was 26 years old because I was navigating this world of trauma. That ultimately helped me the most. It’s having that faith, having a therapist, having family and friends… and then going on adventures. Reality TV, to me, is an adventure. It’s something else I get to do in this beautiful life that I get to live.

Exclusive Interview with Rob Roman https://awarenow.us/podcast/got-to-give-back

ROB: (continued) So, pressure doesn’t really get to me. There’s a lot of negative and bad that goes on in the world, right? If I have the ability to freely move my body and my mind is okay and healthy, I can do literally anything I want. And if I fail, who cares? I have people who love me. That’s how I navigate all this.

ALLIÉ: I love how you say it’s not just one thing—it’s a mix of all these different things. Let’s go here… You’ve now had your feet planted firmly in two worlds—entertainment and service. Looking forward, what’s next for Rob Roman? What mark do you ultimately hope to leave, whether on screen or off?

ROB: I will say, I’ve thought about this a lot. I want to be—and I’ll give you two answers. First, I want to be remembered as someone who made people’s lives better because they met me. No matter how or in what way, if we met—when we crossed paths—and you think of Rob Roman, I want you to think, “Ah, you know, he was funny, or he helped me, or he inspired me...”, or there was just something I did that left your life a little better because you met me. That’s my overall 30,000-foot view of how I want to be remembered.

What’s next in terms of what I’m going to do? My number one focus is growing my business. I want to reach as many families in the state of Georgia as humanly possible, help them, and continue to cultivate those relationships.

And I also want to do more reality TV. I mean, I love competing—it’s fun. I can’t stress enough just how fun it is. Whatever it is you’re interested in, go all in. Have fun. Do it. Experience it. Fail, win, lose—just navigate this human experience we’re all having. So, I want to do more competition shows. I want to grow my business. And I want to have more adventures.

Really, my favorite part about all of this is meeting people. Again, in law enforcement, I was surrounded by incredible mentors—amazing people who took me under their wing and helped me navigate that. With Squid Game, I met some of my best friends in the world and my business partners. With Got to Get Out, I’m now incredibly close with half the cast. I mean, when I go to California, I stay at Val’s house from Dancing with the Stars. People lose their minds when they hear that—I stay with Val and Jenna. I hang out with their son. Steven from the show comes out with us. That’s what life is about, right? Life is about having good people around you, serving them, and—hopefully—things come back to you.

So yeah, that’s what’s next for me: grow the business, get on more shows, and live more life. ∎

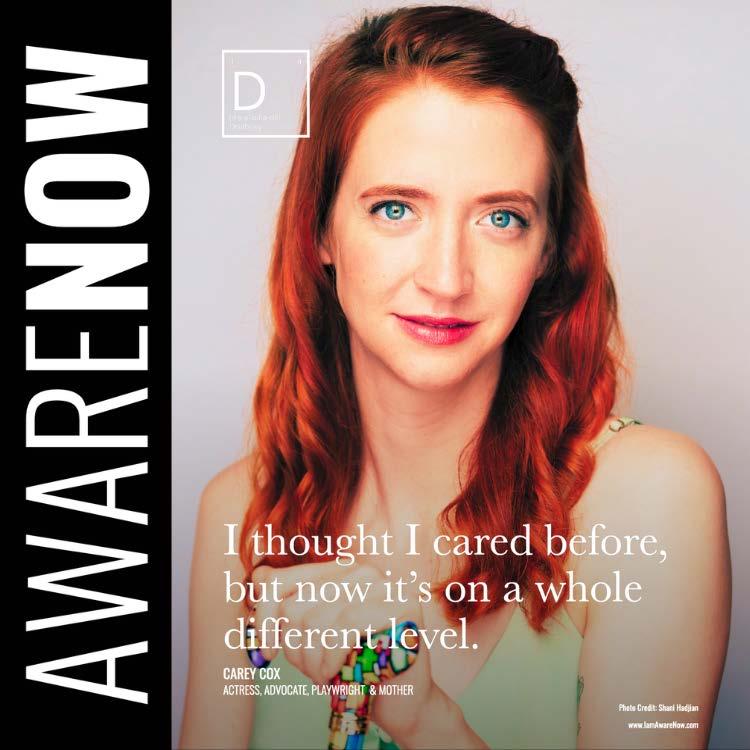

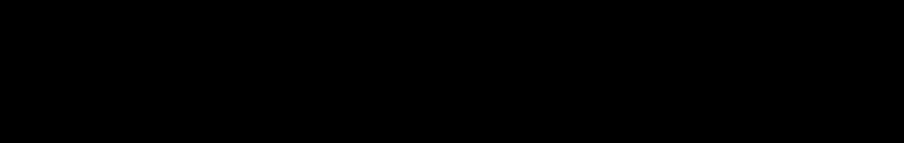

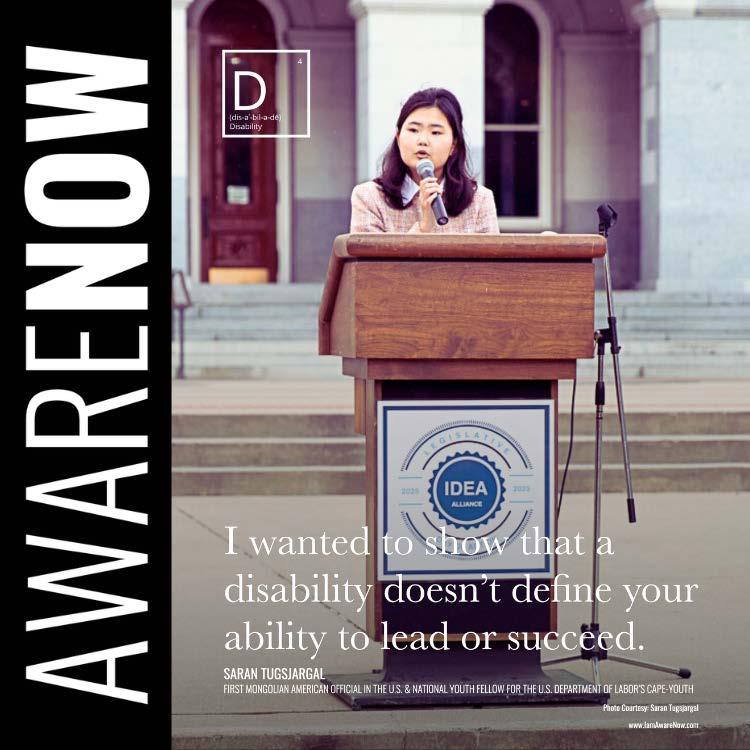

In a world quick to label and limit, Carey Cox defies definition. Actress, advocate, playwright, and now mother, Carey brings authenticity to every role she inhabits—on screen and off. Known for her portrayal of Rose Blaine in Hulu’s The Handmaid’s Tale, she’s not just acting; she’s rewriting the narrative. Diagnosed with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, Carey doesn’t hide her disability—she leads with it. As the final season of The Handmaid’s Tale comes to a close, Carey enters a new chapter, both professionally and personally. With the release of her indie film Where Did The Adults Go? and the arrival of her first child, Carey’s voice in the industry feels more vital than ever.

ALLIÉ: Thank you, Carey, for joining me here to share this space and share your story.

CAREY: Well, thank you. That was so kind. That was such a nice intro.

“My history with The Handmaid’s Tale goes back to when I was a teenager.”

CAREY: Thank you. I always like to say that it comes after a long history of many people working to make spaces for people like me, so I always like to acknowledge that this has been something that people have been working at for a long time. I feel bad because, up until I started identifying as a disabled person and a disabled actor, I wasn't really even aware of all of the years of advocacy and the climb that's been happening for so long to be welcome in not just acting spaces and story writing spaces, but every space as disabled people. So it's very kind to get to wear these descriptions now, and I owe it to a lot of people who came before me.

ALLIÉ: Carey, your journey as an actor has spanned stages and screens, but The Handmaid’s Tale marked a cultural moment—especially with the introduction of your character, Rose. What did it mean to you, personally and professionally, to step into Gilead with a limp, a cane, and your full self?

CAREY: Oh, gosh. Well, it was amazing. My history with The Handmaid's Tale goes back to when I was a teenager. My mom gave my sister and me the book, and it was my sister's favorite book. My sister passed away about 10 years ago, so getting to do this journey now, I often think about her and what she would be saying about this and me getting to be a part of it.

It had such an impact on her at the time and then had such an impact on me. I was somebody who was a little scared to watch the show at the beginning because of how relevant it is and because I’m a very sensitive person. So I had to do a big catch-up. I’d only seen a little bit of season one when I had the opportunity to audition, and so I did this long binge in my room—basically crying for weeks, just watching this show all at once. And that was such a great way to absorb it because I couldn’t escape the world. I was fully immersed in this world for so long, and it was all I could think about and all I could talk about.

And it means so much because Rose doesn’t exist in the book, and the TV show covers so much—it goes so beyond this incredible book. And there’s a scene earlier in the show that I think a lot of people may have missed, where you see a lot of disabled people being executed in a flashback to the beginnings of Gilead, when June is first picked up and becomes a Handmaid. And that was a question that was then unexplored in that way. We didn’t see a story specifically of what happened to specific people (with disabilities)—we just knew it was something that existed in this world. And it’s something that has happened. It happened before and during World War II.

There’s a wonderful documentary—Disposable Humanity. My husband is a producer on this. Everybody should check it out. It’s about the eugenics movement and the execution of a lot of disabled people at the beginning of and right before World War II. And it’s something that’s forgotten a lot—about that part of history. So then getting to explore that through Rose, who is in this privileged position, and the audience has been left to kind of draw conclusions about her place in society and how she was able to survive and get to this point… It’s kind of the unexpected story. It’s more complex than you would think that a portrayal of a disabled person in this world would be, because it’s that story of “What’s right for me doesn’t work for thee.” It’s the exception to the rule. It’s what privilege can do for somebody.

So it’s very interesting. And the audience—it’s been very cool to read about the conclusions that fans have drawn, the connections that they’re making, and what Rose’s life in Gilead would look like if she wasn’t privileged then, versus what her life in pre-Gilead America would have looked like. There’s a lot of discussion about that—What’s a better life for her? Does she enjoy privileges in Gilead that she wouldn’t have even in pre-Gilead America? It’s been very interesting to hear what people have to say about that.

ALLIÉ: You were pregnant while filming this final season—a poetic parallel, perhaps, to The Handmaid’s Tale’s themes of birth, power, and identity. What was it like actually carrying a new life while portraying Rose in a world so deeply shaped by the politics of motherhood?

“It made me wonder about my own place and my own identity, becoming a working person who was going to have a baby.”

CAREY: It's very interesting. While I was going into this season and talking with casting and producers about how that would work and how long into the pregnancy I could film—because everything was lining up down to the wire towards the end—they worked with me so beautifully to make sure that I could film my final scenes before I was at a point where I couldn't travel anymore, because it’s filmed in Toronto and I live in New York. Luckily, it's a very easy plane ride, but there would have been a point when it would have been too dangerous for me to travel.

For my last episode, they allowed Joe, my husband, to come with me just in case we were to have a Canadian citizen. He was there kind of watching everything. And I just felt so lucky at the time that I had this team who was so willing to work with me, because an actor's job is difficult in that it's inconsistent. We never know when the next job is going to come. Everything is so up in the air. There's a lot of uncertainty, and things like locking down health insurance can be a little bit difficult. But the thing that is wonderful about it is the flexibility. My husband and I have been able to be home with the baby. We've kind of been able to set our own hours in that way. And then when we have a job, the flexibility there—of people being able to work with us and accommodate us—that's something that a lot of people don't have.

I've been reading horror stories about people being fired when they've become pregnant and a reason being given so they can't pursue any sort of legal protections. We have friends who have maternity and paternity leaves that are like two weeks long, three weeks long—if they even get them—or they're unpaid. You know, we don't do a ton to support pregnant people in our country. And then to play a character who, again, has privilege, but her powers are so limited. She really can't still speak her mind, even when she's with other wives in social situations. She doesn't fit in, and she feels meek and timid—to then have more power in a way because of being pregnant, or at least to have more visibility, and to feel like the pregnancy at least allows her more survival.

Again, nothing is simple. At the same time as the pregnancy giving her this kind of spotlight, there's this scene where it's almost like a Madonna treatment. I don't ever want to give too many spoilers, but she's de finitely put on this pedestal as soon as she becomes pregnant. But then there's still so much vulnerability in that, because it's a society that—I mean, when we see the Handmaids give birth, it's their own home births. And the ritual of it puts women in danger. And the idea that women are seen as vessels for new babies is complicated. So it's power—but is it really power? I mean, there were so many questions and so many different things to explore. It made me wonder about my own place and my own identity, becoming a working person who was going to have a baby. But one of the best things about being on that set is there are so many wonderful examples of people who've done exactly that. And one of my favorite days on set was when we were filming a big group scene. Again, it's aired already, but I don't want to spoil it for people who haven't seen it. But it was a day when I got to meet so many other cast members, and it was American Thanksgiving. So we were all sitting around having a Thanksgiving dinner and talking about pregnancy. We went back and forth talking about people's experiences having babies or being pregnant while filming, while on set.

It's such a common thing for actors to go through—and particularly on this show. There are so many examples of people who have done that, who've made it work. They have been filming and then run back to their trailer to pump or to breastfeed and then go back and shoot more scenes. Just the blending of life and art… it was very cool. I felt very lucky, and I was very protected. They really took care of me, especially when some of my pregnancy symptoms were getting a little hard to manage. I was so supported by everybody. In particular, Yvonne. There was one time I had to go to the hospital because I had some pain that didn't seem normal. It ended up being normal—I mean, that's with so many things about pregnancy. I find out, okay, this is normal—it doesn't feel like it, but it’s okay. But she looked out for me, and she really advocated that I have a separate little space and an air mattress. She made sure—because she'd been through it herself—and she felt protective in that way. So everybody was wonderful, and I was very grateful.

CAREY COX ACTRESS, ADVOCATE, PLAYWRIGHT & MOTHER

ALLIÉ: You’ve spoken openly about transitioning to auditioning as a disabled actor. What was that internal shift like for you—not just professionally, but emotionally?

CAREY: It's like you suddenly find this sense of belonging, and this wonderful, vibrant world, and it feels like, why didn't I know this was here all along? But then the fact that you didn’t know it was there says something still about what everyone else is missing out on—and all of these wonderful, wonderful people who, I mean, disabled people in general—have a lot in common with parents in having to be flexible and creative and adapt. And that is a skill that so many people can benefit from. In the disabled writing, acting, producing, and directing community, there are so many talented people with unique perspectives that the rest of the world is missing out on.

It becomes frustrating every time someone does something incredible, and it feels like only our community takes notice of it. We have to create our own projects. We have very few people in our community who have enough power to make social or political change. We have to be very loud, and there are still a lot of people who aren’t listening. So it’s bittersweet, finding that community.

ALLIÉ: How has identifying as a disabled actor changed the way you see yourself and your place in this industry?

CAREY: Yeah, it's interesting, and it's changed a lot. I'm somebody who—I question everything. I'm kind of an overthinker, to a fault, I think.

At the beginning, there was this desire to not change too much before I started identifying as a disabled actor and seeking out those spaces and looking for the people who were looking for me. Before I even knew that those people were out there, I was doing a lot of hiding or trying to hide my disability, trying to pass, because there was this resistance and this fear of what I would lose. I’d been very fortunate in my theater career up until then. When I was in grad school, I was working at a professional theater linked to the PlayMakers Repertory Company, and I got to play so many different roles—I got to do Chekhov and Shakespeare, but then also do Theresa Rebeck, and got to play loud characters and quiet characters and villains and heroes and romantic partners. I got to do physical theater, and I was afraid of what I'd be losing in that, to have to be open about my disability.

The fact is, I did lose a lot of variety in how I was seen and how I could be cast. But it was a relief to be seen, and it was a relief to feel like, “Oh, there are people looking at me, and I don't have to hide this anymore.” I can be my true self, and I can tell this part of my story. But after a while, it does kind of hurt your feelings, almost, to be pigeonholed and defined by that. We find there are so many stereotypes—especially if disabled people aren't given the opportunity to write their own stories—then you see a lot of the same kind of story over and over again. You see a lot of the same kinds of characters being written—characters who are defined by their disability, or the story is always some inspirational thing.

What I would start to find is, I would get an audition where it was maybe for a non-disabled character. My agents are so wonderful about trying to push any role, not just roles that are written as disabled, but I would find myself going, “I'm not going to get this part because the person in this scene has to yell at me.” There would be little things where I just know—they're not going to cast a girl who uses a cane or a wheelchair in this role because they're not going to want the main character to yell at them. Because what is that going to look like?

You're just so aware of the way that you are perceived. Over the 10 years or so that I've been exploring this identity, I'm coming to this place of really being able to appreciate when I can play a part that's a full person. The disability stories are still really important to be told, because there's such a lack of education about it. But it's wonderful when we can be disabled people and also be full characters—and disabled can be flawed and complex. That's one of the wonderful things about Rose. And especially right now, what's been interesting to see—again, it's so hard to talk without spoilers—but I can just say there's been a flip. It's been interesting to see a flip in how people have perceived her, and I don't think that flip would have been possible if people weren't seeing her as a person first and a character first, and a person with a disability second. Even though I love disabled- first language—again, I go back and forth. It's very complicated. You want to be able to lead with your disability, but then also lead with your personhood. I tend to fluctuate on what feels most important. I go back and forth and back and forth, and I overthink about everything. But it is complicated.

ALLIÉ: As an actor, you star in major productions like The Handmaid’s Tale to independent films such as Where Did The Adults Go. But to bring so many different stories to life you wear many different hats. In the short film, Adoptive, by you and your husband, Joseph Kibler, you both serve as the writers, directors and producers. If you would, for those who have not yet had the pleasure of seeing Adoptive, please share the story behind this brilliant short story.

CAREY: Oh, thank you. Well, it started out as a concept for a pilot that we wanted to pitch as a full TV show. And then, when the Easterseals Disability Film Challenge revealed that their genre for filming last year was buddy comedy, we thought that was perfect for us—because our lives kind of look like a buddy comedy, the way that Joe and I get through the world. And then we felt like it was a good opportunity to explore what we wanted to talk about in our pilot through a short, kind of condensed thing.

And so, it's a story of a disabled couple who want to adopt. They are indulging in some THC treats, because it's fun for them—they're just regular people. And they also use it for some pain relief, and they're having a good time. Then they realize that they’ve mixed up the days of when they're having their adoption home visit, and it's too late to turn back in their THC journey. What it does is stoke their paranoia that's been under the surface—about how they'll be perceived as disabled parents.

So, it's kind of this silly comedy of them trying to hide the things in their apartment that reveal them to be disabled people, and at the same time trying to compensate for their disabilities. Like there's a moment when I take my master's degree and stick it in the hallway so it's the first thing the person sees when they walk in. We were just trying to talk a little bit about that—and about how we knew we would feel when we went on the parenting journey, which then for us started not too long after that, in having our own biological baby.

This idea of, I can do it, I can do it—but I also shouldn’t have to. I shouldn’t have to hide it. But I think I’m going to in this moment because I know I might be judged for it. And then there’s a nice reveal at the end, where they realize that they didn’t have to worry that much. We wanted to explore that feeling of relief that we do feel when we are in what we sometimes call “crip spaces,” you know—when we know that we don’t have to hide or explain things away.

CAREY: (continued) We were inspired by that because we were doing some research into adoption for our pilot idea. We knew that we wanted to start a family, and we knew that we wanted to begin the journey the—quote, unquote— “traditional way.” In just looking at what all the options would be, we found how complicated adoption is. And in our media, it’s so often depicted as this kind of wonderful thing—which it often is—but there are so many other sides to it. And there are a lot of people who, on all sides of the journey, carry some trauma from it.

And in terms of adoption as an industry—it’s an unregulated industry in this country. And the way that it intersects with disability is really interesting, because a lot of children who end up in the adoption process or in the foster system have disabilities. And then a lot of parents who want to adopt might have disabilities. I mean, there are a lot of disabled people who just want to adopt—because disabled people are people like anybody else. But then also, people who might be on an infertility journey might come to adoption not as an alternative, but as a different and wonderful, valid, separate path—and then find that they’re so discriminated against. It’s very difficult to be approved for adoption as a disabled person. And a lot of disabled people wait years and years and years.

We read one story of a disabled couple who went through the process for about eight years, and then finally, about a month after they were approved, the father passed away. So it took them so long to get approved that there were medical complications that happened. And it was just a really sad story about how long they had to wait and what they missed out on then because of that. So we want to explore that in our pilot.

Luckily, after creating our short film, we received a grant from the Easterseals Disability Film Challenge to now create a pilot/web series based on our original pilot. So we’ll be doing that later this year. We’re going to be directing and producing and writing and acting in it, and then trying to get a lot of our community involved—both in front of and behind the camera—to really explore, in so much more depth, this issue. But at the same time, we’ll be looking at it through a comedic lens, because we find that it’s fun for us. We love comedy, but also, people can learn in a way that almost doesn’t feel like learning—or being preached to—or uncomfortable. Comedy is such a great tool in that way. So we’re so excited.

ALLIÉ: Becoming a mother is a story in and of itself. How has your perspective changed since Milo was born? What’s something unexpected you’ve learned about yourself in this new role?

CAREY: Oh my gosh, there’s so, so much to it. It’s like, where do I even begin? My day job for years now—I’ve done waiting tables and all sorts of other day jobs—but since I moved to New York, it was nannying. I worked for a babysitting company where people could request you, and you could go for just a couple of days and babysit. It was very flexible, and so it meant I got to babysit like 60 different families all across Manhattan and Brooklyn for years.

I love children. I’ve always felt very protective of children and got to meet so many and learn so much. So going into pregnancy, I felt like I was going to have a step up, right? I’m going to know some things. I’m going to be a bit prepared. But then there are so many things that you’re not prepared for.

The main thing I wasn’t prepared for was the level of how much you love your baby. I mean—and this is not universal, I’m not going to speak for everybody—but my experience was, I felt this indescribable love for him immediately that went beyond anything I’ve felt before. I mean, the closest is my love for my mom, my love for my husband. It was—I talk about craving my baby or feeling like he is a piece of my body. And when time has gone by without being around him, I feel like something is missing. I feel very grateful that that clicked for me like that because it can be helpful in some ways.

But then it also created this intense anxiety that goes... I mean, I lost sleep because I would just be watching him at night. I would worry about every little thing. So when I felt like, with other people’s children, “Oh, I know what I’m doing, this is normal, I’ve seen this with other babies.” Suddenly when it’s my kid, nothing feels normal. I’m Googling everything—you know, which I’m not supposed to do. We’ve reached out to the pediatrician about so many little things

“All of these things that I have cared about on an intellectual level before, now I suddenly care about on a visceral level.”

CAREY: (continued) that just end up being normal. And that’s been a challenge. But at the same time, I’m also talking with a prenatal expert therapist about this, which I’m so lucky to be able to do. She’s described it as the anxiety being “heart-opening”, because it’s created in me this sense of responsibility, and this sense of fierce protectiveness that now doesn’t just apply to him.

So, I find that when I read about things in the news about babies in parts of the world not being allowed baby food because the trucks are being held off—humanitarian aid being held from babies—or when I hear about children in parts of the world being made to do physical labor to build our smartphones… All of these things that I have cared about on an intellectual level before, now I suddenly care about on a visceral level. Where it almost feels like—yes, I know I’m just one person, and I can’t do that much, I don’t have that much power—but there’s this instinctive feeling like, “But I’m the grown-up now. I should be able to do something. It’s my role now to protect these vulnerable creatures.”

So it’s been very, very interesting—the level, the depth of care that I didn’t know I was capable of. Because I thought I cared before, but now it’s on a whole different level. And I hope there’s something I can do with it that’s productive.

I know that it helps me be a better mom. But I also hope it can make me a better person, when we’re able to reenter the world more and we’re not so much in our little bubbles. It’s been this hard thing, but also a gift at the same time. That’s what’s surprised me.

And also just—confidence. I feel so much more confident as a person. I don’t waver as much in what my opinions are or what I know that I need to do.

ALLIÉ: It's a very grounding experience, isn't it? And I hear you a hundred percent when you're speaking about these babies and kids in these other places where you are not and that are not yours. When you become a mother and you look at the world through a slightly different—no not ‘slightly’ different, but very different—lens, you look at these children and you can see your own child in them. So I feel you in that level of anxiety where it's just a different connection that is not only to your own child, but to the world.

CAREY: Definitely. It's beautiful to feel that there are new levels to that, and I hope that it just continues to get deeper. But at the same time, it's painful and very sad. You wish that you could do more. It's also pointed out further to me about how we really need the collective to be able to make change. I mean, we hear, especially in our country, so many stories of one person making a difference, but we really need every person with a parent heart and anybody with a beating heart to come together to make change.

ALLIÉ: With having kids comes having books for kids. In a post of yours, one book you have that you asked your husband, Joseph, to read Milo had you both in tears (and me) as he read to your son. It was titled ‘The Wonderful Things You Will Be’. When you think about yourself and the wonderful things you are and will be (as a mother, a wife, an actress, a playwright, a visual artist and an advocate), what wonderful thing do you hope people will remember about you and your legacy?

Exclusive Interview with Carey Cox https://awarenow.us/podcast/full-presence

CAREY: Oh, gosh, that’s—so, it’s not up to me, you know? That’s what’s so, so interesting. People will take what they take. I just hope that people would be able to see that I tried. And I want to feel like I tried.

Joseph and I both—he was born with HIV, and he lost his twin brother when they were infants to HIV. And I lost both of my siblings—my brother when we were teenagers to cancer, and then my sister years later to an accident that I kind of can’t talk about so much. But we both—and then having a diagnosis—I was in the hospital when I was a teenager with a collapsed lung, and that was related to my disability. My time in the hospital went on and on and on. And so we carry with us this sense of mortality. We’ve always kind of carried that, even as young people, this sense that life is short.

We have this drive to make the most of every day, and to accomplish and to connect to people. And we feel—we guilt ourselves over some things. But we also need to learn how to slow down and be in the moment and appreciate the slow and the quiet times, because those are so important. And that’s what life is really about—for yourself and your own experience of life. And Milo, our baby, is really helping us to remember that—and that it’s okay to slow down. For myself, I want to find that balance of being able to get the most out of my own small existence here for myself, which means slowing down and taking things one step at a time. But then I also want to leave an impact where I’ve created as much as I can, connected as much as I can, and tried to help people as much as I can. And I will always be falling short of that. Like, in the middle of the night, when I’m feeding Milo, I’m trying to catch up. I’ve been trying for years now—and not making a lot of progress—to learn Spanish and to learn ASL, so that I can connect to more people and be more valuable in different spaces. It’s a goal, and it’s a journey. I might never get there, but I’m trying.

So, if anybody were to be able to recognize that we’re trying, I guess that would be it. We’re very good at saying, I think, that we don’t have it figured out—what we’re supposed to be doing with this life. At least we stay open. And we try to stay open and humble and flexible to what that means, and what the right way to live is. ∎

BRYAN SCOTT PROFESSIONAL FOOTBALL

When Bryan Scott steps into a room full of young athletes, he brings more than his résumé as a professional football player—he brings purpose.

It’s not about the stats or the highlights. It’s about the human moments. The quiet ones when a kid who’s been doubting their worth starts to believe in something—sometimes for the first time. “Might not change everyone’s path,” Bryan says, “but if I change one… that’s enough for me.” That’s the heartbeat behind every talk he gives, every hand he raises to say, “I see you. I believe in you. Let’s figure this out together.”

Bryan’s approach isn’t built on preaching. It’s built on presence. He doesn’t show up to hand out advice—he shows up to listen, to engage, and to help young people find their ‘why.’ For Bryan, it’s not about making them follow in his footsteps, it’s about helping them take their own. Whether it’s in a locker room, a classroom, or a community center, he’s there to ask the hard questions, share the honest answers, and ignite the kind of con fidence that doesn’t depend on trophies but on truth. Raising your hand isn’t always about having the answer—it’s about showing up. Bryan Scott stands up for youth by standing with them, shoulder to shoulder, reminding them that their story matters and their

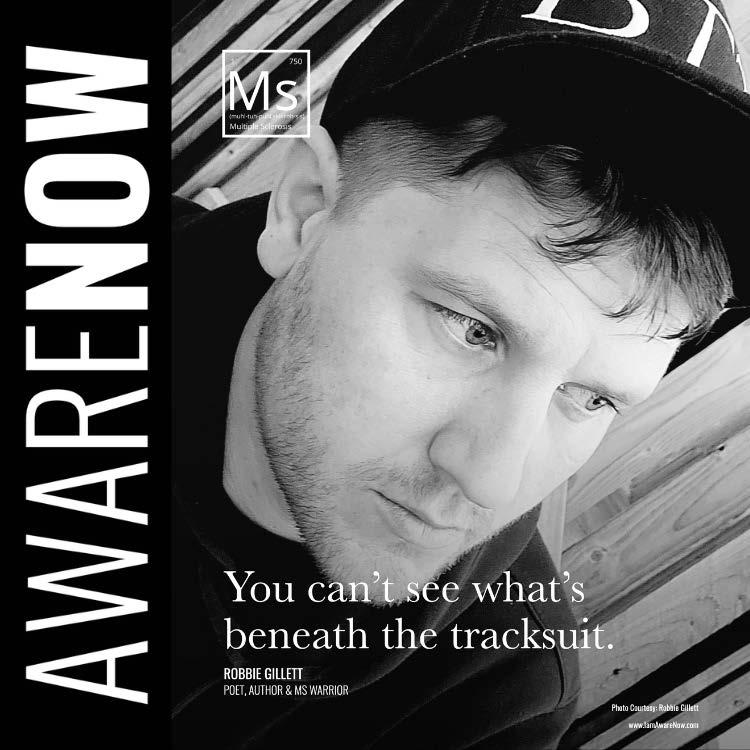

Robbie Gillett didn’t plan on becoming a poet. But after an MS diagnosis turned his world upside down, he found himself reaching for something to hold onto—something beyond the fatigue, the depression, and the invisibility of it all. Encouraged by his wife, Robbie began writing. What started as a private thought diary became public poetry— raw and resonant. Under the name “Beneath the Tracksuit,” he gave voice to the quiet battles many face but few speak of.

ALLIÉ: Robbie, can you take us back to the day when everything changed? What do you remember about that moment when your body first signaled that something wasn’t right—when something was wrong?

ROBBIE: It was really scary. I was at work—I was a kitchen fitter—and I was in a block of empty flats, building a kitchen by myself. I knelt onto a unit to put the feet on, and I was stuck there. I couldn’t move. My arms wouldn’t move, my legs wouldn’t move. I had a drill in one hand and was holding myself onto the unit with the other—and I couldn’t move. It was the weirdest sensation I’ve ever felt in my life. I was just stuck there for five, six, seven, eight

But they added it all up and said, “Yeah, you’ve got MS.”

ROBBIE: (continued) And then, just as quickly as it happened—which felt like a lifetime—things started to come back. Fingers, toes, head… I could move again. But before that, I couldn’t shout, couldn’t talk. I couldn’t do anything. I was just stuck there. And that was it. I stood back up, and I was absolutely fine. Nothing seemed wrong with me. It was the weirdest feeling ever.

ALLIÉ: You just became like a statue all of a sudden? Just—frozen?

ROBBIE: Yeah. It was really surreal. And when I started explaining this to doctors, they said it wasn’t a typical MS relapse. That’s why they couldn’t give me a diagnosis of MS at first. They said relapse symptoms happen over a month—they come and go. But mine was just like that. And all my symptoms that followed were really intermittent. Like, my hand would curl sharply and stay that way for half an hour, and then it would be fine again. But it wasn’t consistently stuck like that.

The headaches too… At first, the headaches were like being hit with something really hard. They’d last for hours and hours, and I’d curl up. They thought maybe it was migraines, but migraine tablets weren’t working. So, at first, it was all just weird. Nobody had the right answer.

They sent me off for scans—thought I’d had a stroke. Then an MRI showed one little lesion in the brain. Just one. And all that damage I’d felt—caused by one tiny lesion. One plaque. Nothing in the spinal cord, nothing else in the brain. So, they said it could be CIS—I think that’s what it’s called—where it’s just one episode. That might not be the right name. I’m terrible with the names. Something isolated anyway. That’s what they thought it might be.

But six months later, symptoms persisted. The claw stayed longer, the headaches got worse, and I was always fatigued—just battered. I felt battered. Like my body had been ripped apart.

Then they sent me back for another MRI. There were more lesions in the brain. And then came the lovely lumbar puncture, which I completely melted down during. The anxiety—I couldn’t do it. I had a panic attack. It was the most horrifying thing I’ve ever been through. It’s weird, because it’s just a needle—right? But I’m fine with anything, as long as you don’t tell me about it. But when they started saying, “I’m going to fold you in half slowly…” and they started going through all the steps—that’s when I panicked. Full anxiety attack.

But they added it all up and said, “Yeah, you’ve got MS.” It was a year to the day, pretty much.

ALLIÉ: “You’ve got MS.” These aren’t words that are easy to hear. Let’s talk more about other words—your words. You’ve described your early writing since diagnosis as a thought diary that evolved into poetry. My question for you now, Robbie, is: What did you discover about yourself in that process? Through this poetic exploration, what did you uncover about you?

ROBBIE: I started writing, I think it was six or seven years after my diagnosis, when I was mentally struggling. Symptoms had started getting really bad. I’m in a wheelchair quite a lot, I ride a scooter, I have to self-catheterise at night and things like that. So, things were getting really bad. And I needed a way to vent.

I really found myself, artistically, dealing with my pain. It was amazing. Because I was taking these negative thoughts from here (points to head) and turning them into something else over there (gestures)—and that changed everything. Suddenly it wasn’t a bad thought—it was a good poem. It still explained the same thought I was having, but now it wasn’t trapped in me—it was out there. It helped me communicate.

I’m not alone in this.

ROBBIE: (continued) It’s brilliant, really, because the way I talk and the way I write are two completely different people. I talk slang, very casual—I’m just me. But when I write, I really try to be artistic with the words. I love that. I love it so much. I never did that in school. But now I’ve found this talent—this passion, if you like. I write a lot. And I don’t just write about mental health anymore—I write about everything.

ALLIÉ: I love that. I love how your words became your salve—a treatment of sorts. Let’s talk about more words though. Let’s talk about three words, specifically.Your name ‘Beneath the Tracksuit’ says so much without having to say much at all. What does it mean to you personally, Robbie? And why did you choose to share that part of yourself publicly? Let’s start with the name.

ROBBIE: So, at that point, my poetry wasn’t out there at all. But I wrote a poem about how people look at you. It was a thought process I was having. All the poems came from thought processes. And the final line of that poem was: “You can’t see what’s beneath the tracksuit.”

I wear tracksuits all the time. They’re comfy. Easy to get on and off. Ideal for me. They hide the FES wires, the foot splints, the hand splints, the wraps. They hide everything. They’re a gem. But the idea is: You can’t see what’s happening underneath. The mental health. The MS. The daily struggles. It’s all hidden beneath the tracksuit. It’s inside. So, that’s where the name came from. It was the last line of a poem—before I ever started sharing.

The idea to share? It wasn’t mine. I didn’t want to put my emotions out there. I was stuck in the stigma. You know— men don’t talk. That kind of thing. It was personal. But my wife, Donna Marie, it was her idea. She said, “Share it. You could help people.” I said, “No. I don’t want anyone to read or hear what I’ve written in this book.” She said, “I think you should share it. You’re teaching people it’s okay to talk. You might help someone.” So eventually, I said okay. It took a while. But I did.

ALLIÉ: And it takes something, doesn’t it? A kind of bravery. What was it like the first time you put your poetry out into the world? What was the response? How were you feeling?

ROBBIE: I was scared. Really anxious. I didn’t want to share it worldwide. I didn’t want it going out to the masses. So, I thought, If I could just show the people I know—just show them what MS is like—maybe I could invite people in along the way.

I shared in MS support groups, and people responded, “Oh my gosh, this is telling my story. Straight away.” Then I joined more groups, and people said the same: “You’re saying what I’m feeling. This is my story. You could’ve written this for me. Thank you for saying what I can’t say.” That was amazing. Within a month of sharing my first poem, MS Focus Magazine in America reached out. They wanted to publish my poem and do an interview. It was crazy. I remember thinking it would be nice to have as many followers as I had friends—like 200. Within a couple of months, I had 3,000. It was really good. But I was still really anxious. Still am. Every time I share a post or a poem, I spell check everything. I’m not the best at spelling, so spell check is my best friend. But I like that I get anxious—it shows I care. It proves to me that I care. It’s not just fear of embarrassment—it’s about wanting to do it right.

ALLIÉ: And at the same time as that anxiety and fear, I imagine there’s a sense of freedom. That’s the win—for you and for the person who hears it. They feel seen. They feel connected.

So let’s talk about Donna Marie. You said she encouraged you to start writing. How has her support shaped your journey, both as a poet and as someone living with MS?

ROBBIE: She’s been behind me the whole way. At first, when I was diagnosed, I was very selfish with it. I thought, “This is happening to me. What’s happening to me?” I shut down and tried to deal with it by myself. But she was there —supporting me the whole way. And now, I’m more open. I talk to her when I’m struggling. She’s still right by my side.

And as a poet—people see me on stage, in photos or videos—but there’s always an army behind me. And leading that army is Donna. I have her in my corner. She brings my books, sets up my stands and props, helps calm my anxiety, does the bar runs to get me a cup of coffee. Because MS is draining. Fatigue wipes me out.

Exclusive Interview with Robbie Gillett https://awarenow.us/podcast/beneath-the-tracksuit

She listens to all of my work—even the painful pieces. To the ones about suicide or depression, she listens to them again and again while I refine the wording. That can’t be easy. Imagine hearing the person you love say they’re sad— over and over again. But she’s a gem. I wouldn’t have done this journey without her. I tell her that all the time.

ALLIÉ: Well said. She’s always in your corner… I’ve listened to a few of your pieces on Spotify and truly loved them. So, let me ask something a little more personal, Robbie. Is there a favorite piece or favorite line from something you’ve written? A one-liner that you say to yourself, “If there’s one thing I want people to hear—this is it.”

ROBBIE: Oh, that’s a hard one. There are a few… “My Strength Must Survive”—that one sticks with me. The first letters are MSMS. That’s actually the title of one of my poems. Another is: “I may be damaged, but I’m not broken.” I’ve got scars in my brain—but I’m still all right. I may be damaged, but I’m not completely broken. I can still… I still can. But if I had to choose just one: “You can’t see what’s beneath the tracksuit.”

ALLIÉ: Last question, Robbie. If you could write a letter to yourself the day you were diagnosed, what would you say?

ROBBIE: I’ve just got chills. I wouldn’t even know where to start… But I think I’d say: “No matter how hard it gets, you will be okay.” It has gotten hard… really deep at times. I’ve dealt with a lot of negativity in my brain. But it’s always been all right. I’m here now. I had a good day today. I’ve been weak, I fell a few times, had a headache—but I had a good day. And I’ll take a good day. Also, I think another reason I started writing is because I wish I had someone like me when I was diagnosed. I wish I’d had the words I needed back then. But I didn’t look for anyone. I kept myself hidden.

ALLIÉ: Exactly… And you find when you open up, it’s not just for you—it’s for others too. Even if you didn’t know they needed you… they did. And I can tell you, Robbie, that your words—people need them.

ROBBIE: It’s a weird feeling, sharing. People tell me all the time, “Thank you—you make me feel less alone.” But they do the same for me. Because when I share my words, and someone says, “I know exactly how you feel,” they actually do. They understand. That’s really important. Even now, when I share a new poem and someone says, “You’ve got me there. That’s how it is for me today...” That’s amazing.

I’m not alone in this.

It makes me feel validated, not just crazy. This is real. It’s happening—and not just to me. ∎

ORIGINAL

POEM BY

ROBBIE GILLETT

My struggle may seem managed, Some might say my strength makes stresses minimal, Simple.

My smile may seem magnificent, Smiles mask so many signs. My smile magically stores my struggle. My sickness making scars, My scrambled motor skills, My shipwrecked mental state, Masked.

So many struggles may shatter me, Still my strength must survive,

Many stereotypicals make struggling mental states more severe. My supporters make struggling minor, Some make smiles memorable. Support may secure my stability, May save me.

Staying mentally strong must suffice. My sanity may spiral, Mental state may suffer, My serenity may struggle, My strength must survive.

Mistaken speech misaligns self motivation, Shabby movements stupidly make standing more strenuous. Menacing spasms make significantly more stresses, My sleep misses so many stages. Many symptoms may seem mighty strange, Multiple Sclerosis might seem magnificently stranger, Multiple Sclerosis makes simple measures severely monstrous, Still my strength must survive.

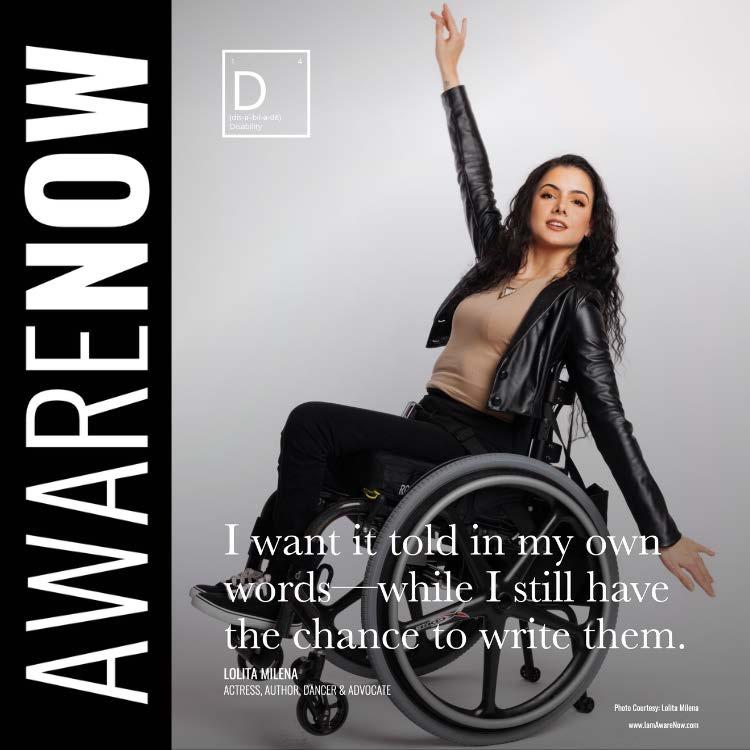

From Siberia to the stage, Lolita Milena’s story is one of unimaginable resilience and undeniable talent. Paralyzed at the age of two due to an act of abuse in foster care, she has never let her wheelchair define her path—only refine her purpose. Today, as an actress, author, dancer, and advocate, Lolita is breaking barriers in the entertainment industry and beyond. Through every role she plays and every story she tells, she offers the world a deeper understanding of strength, identity, and what it truly means to rise.

ALLIÉ: Let’s start out this way. Before we dive into your artistry and advocacy, I’d love to just go back to the beginning. For those just meeting you now, can you share a bit about where your story started—from the early days in Siberia to the moment everything changed for you at just two years old?

LOLITA: So, a lot of my beginning that you just described was told to me, because I personally don’t have any firsthand recollection of it. But from what I know—from records and all the tellings from police to my parents—I was born

ACTRESS, AUTHOR, DANCER & ADVOCATE

“I spent nine months with that family before the foster father, in a fit of rage, broke my spinal cord at the T12 area.”

LOLITA: (continued) I lived in Russia for approximately two-ish years before a foster family in Ohio brought me and another child to the United States with the intention to adopt us. The reason they had chosen to go that route instead of adopting children in the U.S. was because it was more lenient process-wise to bring children over from another country. They kept getting denied in the U.S.—which honestly should’ve been a bit of a foreshadowing moment for people.

I spent nine months with that family before the foster father, in a fit of rage, broke my spinal cord at the T12 area. I was then immediately placed with my current family, who adopted me when I was five years old. I was their foster child from ages two to five. They specialized in emergency placements for traumatized, disabled, and special needs children. I gained eight sisters and a brother. All of us have some form of disability, whether it’s mental or physical. And life basically started when I entered that home.

ALLIÉ: That is incredible. I don’t think there are many people who can say they were born in a barn.

LOLITA: Well, I mean, there was a very famous man 2,000 years ago who was born in a barn.

ALLIÉ: This is true. So, you and him. And there we go… Let’s switch gears a bit. After everything you just shared— everything you endured so early in life—I think it would’ve been really easy and understandable to shrink back from society. But you didn’t shrink. You went forward—onto a stage, into a spotlight. So, I guess my question now is: what is it that called you to perform?

LOLITA: Well, when you say I didn’t shrink—it was more so that I had a family that was so understanding. The majority of my siblings went through worse than I did, and in their own way, they didn’t want to see someone so young back away from society and from what they could be.

So, I was a very timid and shy kid for about a minute—until I developed my voice. I learned English. I had very broken English. Russian, too. It was all very broken. I don’t remember any Russian anymore—so no Russian for me. But after I came out of my shell and started talking to anyone who would listen (in stores, with my mother or my sisters), we went to see a show at the Ballet Theatre of Ohio. It was Sleeping Beauty.

In the theater I grew up attending, there was an ADA section. So, I was just dancing in circles in my wheelchair—and the ballet instructor took notice. She approached my parents after the show and offered me a position with the dance company. I went on to be with them for about five to six years.

ALLIÉ: That is amazing. So it was Sleeping Beauty that got you started. Do you remember what it felt like? I mean, it was quite some time ago and you were quite young, but do you remember what that moment felt like—the very first time you danced in front of an audience?

LOLITA: It was opening night. We were getting ready to go to the theater, and my older sisters loved to tease me. I think that’s just what siblings do. I had no idea what the term ‘stage fright’ meant. I didn’t know it was a thing.

I was writing and creating stories by six years old.

LOLITA: (continued) I had been doing really well in rehearsals, but my sisters teased me, saying, “You’re going to get this thing called stage fright, because you’ll be performing in front of 3,000 people.” It was opening night, and the Nutcracker was a huge deal every season.

I was sitting in this 1850s wheelchair, about five times too big for me, and I was playing with my dress, thinking, I don’t know what this is going to feel like. Will it feel like a scary movie? A bad dream?

I got through Act One, left the stage, and I remember thinking, “Well, nothing happened. I had fun.” I told my father that on the drive home, and he said, “That’s how you know you were born to do it—because you didn’t get stage fright. That’s how you know this is for you.”

ALLIÉ: Beautiful. Let’s talk about your home growing up—with nine other siblings, many of them fellow foster youth. That must have created a world full of layers and different perspectives. So, here’s my question: what role did storytelling play in your household?

LOLITA: To begin with, I didn’t grow up with all nine at one time. The oldest three were my parents’ biological children. They were grown by the time I came into the home—had children of their own, had all moved out.

So, I mostly grew up with the foster kids—all girls. And when it comes to storytelling, they each had different senses of humor, and they were all different versions of dark. That’s where I got my dark sense of humor. But I appreciated that, because I learned where to draw the line with humor. I think a lot of people—even big-time comedians—can struggle with that. It’s not their fault; it’s just different perspectives. But I’m very grateful I learned where to draw the line, especially now that I’m an entertainer myself.

As for storytelling, it was everywhere. They all had different movies and books they liked. My sister who’s deaf—once she found out I knew how to read—made sure I got into Marvel, DC, Harry Potter, all the fantastical things. Other sisters loved horror films. My mom accidentally took me to see Saw when I was four years old—she thought it was a cop thriller (oops). I had sisters who loved comedies and would sneak me into their bedroom at night to watch White Chicks.

So, if I wanted a scary movie—I had sisters for that. If I wanted comedies or deep dramas—I had others for that too. My mother and I bonded over movies. My father and I bonded over books. Stories were everywhere in my house, whether they liked it or not.

ALLIÉ: I love that—stories in all different forms and formats. So, how did storytelling help shape your own voice?

LOLITA: I was writing and creating stories by six years old. I had all those dollar store journals filled from cover to cover with short stories. It helped me realize how big I could make my world—that my world didn’t have to have a final atmosphere to it.

Most of my stories today come from dreams. My brain starts creating stories with beginnings, middles, and ends, and all I have to do is wake up and write it into a script or a novel. That started around age 10 or 11. My father once said, “That’s how you know it’s a gift—when it comes so naturally, you can’t stop it.”

Writing helped me through a lot of hardships. I could write stories with the endings I wanted—not the endings reality gave me. It’s how I tackled obstacles creatively. By age 12, it had become a huge outlet for me.

ALLIÉ: Yes—and especially as a child dealing with trauma, that outlet becomes a way to gain control. You become the one holding the pen.

Exclusive Interview with Lolita Milena https://awarenow.us/podcast/writing-her-own-role

ALLIÉ: (continued) You’ve been outspoken about the need for authentic disability representation in media. So, when you look at the roles you’ve played—and the ones you dream of playing—what’s the story that hasn’t been told yet that you’d like to bring to life?

LOLITA: I actually have that story in the works already. I’ve been discussing it with some production people, so I don’t want to give too much away. But I’ve been brewing it for five and a half years—it’s my baby. I tell my family, if I can only make one movie before I die, it’s going to be this one. I want to showcase strength—speci fically in paraplegics. Not just mental strength. I grew up with Professor X, Bentley the turtle from Sly Cooper, Barbara Gordon from DC—all these characters in wheelchairs who compensated with intelligence. And that’s not a bad thing. But I used to wonder —why can’t there be physical strength too?

I loved The Dark Tower and the character of Odetta. She had physical strength. I want to bring that kind of layered strength into storytelling. I think mainstream media doesn’t touch on that often—or they did once and then went back to the same formula. I want to prove these “niche” ideas can work on a big scale.

ALLIÉ: I love that. There’s such a difference between check-the-box representation and authentic representation. So, uh—can you get this going soon? Because I would very much like to watch it.

LOLITA: Tell them. Tell Hollywood. I’ve been trying—please!

ALLIÉ: All right—we’ll see what connections we can make here. Just one more question for you, Lolita. You’ve turned so many chapters of your life into art—through movement, through words, through all those journals you’ve filled, through film. But what chapter are you writing now, in your own personal life story? Maybe one the world hasn’t seen yet. What would that chapter look like?

LOLITA: Right now, I’m putting all my memories into one cohesive manuscript. I started doing that when the realization hit me that—even though I’m adopted—my father, my adopted father, had ALS. He was starting to develop memory issues. For my father, his brain was everything. He was IQ-wise a genius. And I think the scariest thing for him was losing that.

It hit me after I graduated high school that I don’t know my medical history. So right now, my personal mission is to get my life written down—as I remember it—before I no longer can, or before someone else tries to change that narrative. I want it told in my own words—while I still have the chance to write them. ∎

PAUL S. ROGERS

‘RELEASE

Release the Genie fact: The Genie can cut through a hot knife with butter.

In the fast-paced world we live in, it’s easy to become absorbed by day-to-day responsibilities, material goals, and personal achievements. Yet, at the end of our journey, it is not our possessions, titles, or accolades that remain but the legacy we leave behind.

A great way of seeing if your life is where you want it to be is to change your perspective and reverse engineer your life. You can do this by starting with what you would want people to say about you at your funeral.

A legacy is more than just what people say about us after we’re gone. It’s the indelible mark we leave on others through our actions, values, and most importantly, how we make others feel. It’s the ripple effect of kindness, courage, leadership, and love that continues long after we’ve moved on. Everyone leaves a legacy, whether realizing it or not. The ultimate question is “Is it one of inspiration or regret?”

So how do we live tomorrow, today? One way is by living with an awareness of your legacy. This awareness gives your life a sense of purpose and direction. It encourages you to reflect on the person you want to be and how you want to be remembered. This clarity can help guide your decisions, relationships, and priorities. Instead of being driven solely by success, by the need to be right or by survival, you begin to live intentionally; rooted in your core values and vision.

Living tomorrow now shows up in the way you treat others, how you show up in relationships, and how you contribute to your community. A kind word, a listening ear, a helping hand; these small moments can profoundly impact someone’s life. Your legacy may be a student you mentored, a child you raised with love, or a friend you supported through a tough time. When you uplift others, you create a chain reaction that continues far beyond your own influence. Be on the lookout for the small signs of tomorrow’s nodded approval.

Life is not without its challenges, but your legacy is defined by how you face them. Adversity can either break you or build you into someone stronger, wiser, and more compassionate. Those who transform pain into purpose leave a powerful legacy of resilience. It shows others that even in the darkest times, there is hope, strength, and an opportunity to grow. Your honesty and vulnerability can help others feel less alone and more hopeful.

Your legacy can serve as a beacon for those who come after you. Whether you’re a parent, teacher, leader, or friend, your choices become a living example. By living with integrity, empathy, and perseverance, you model what it means to live a life of value. Your story can become the spark that ignites someone else’s dreams and helps them believe in their potential.

Your values are how you live your life and are the foundation of your legacy. It is easy to lose your way and become distracted. A moment of self reflection can change all that and let you focus on what matters most to you. Let those values shine through in your daily actions. When you align your life with your core beliefs, you naturally inspire others.

AwareNow Podcast LIVING TOMORROW TODAY

Written and Narrated by Paul Rogers https://awarenow.us/podcast/living-tomorrow-today

“Your legacy is not written in your will; it’s written in your everyday actions.”

The people closest to you like your family, friends and coworkers are deeply affected by your presence. Show up, be present and engaged. Listen deeply. Celebrate their wins. Support them in failure. And be a consistent source of encouragement. These moments of presence often become the most cherished memories.

Contribute to causes greater than your own comfort or gain. Whether you volunteer, mentor, advocate, or simply perform acts of kindness, these efforts create ripples of good that outlast you. Service adds depth and richness to your life and strengthens your connection to humanity.

Holding onto grudges or regrets weighs down your spirit and diminishes your legacy. Forgiveness sets both you and others free. Get into the habit of loving generously and this will become the most enduring gift you can offer. A legacy built on love leaves a lasting imprint on hearts.

Your legacy is not written in your will; it’s written in your everyday actions. It’s not something you build at the end of your life; it’s something you create moment by moment. Each choice you make is a brushstroke on the canvas of your legacy.

A meaningful legacy isn’t about being remembered by everyone. It’s about being remembered by someone whose life is better because you are/were in it. ∎

PAUL S. ROGERS

Transformation Expert, Awareness Hellraiser & Public Speaker www.awarenowmedia.com/paul-rogers

PAUL S. ROGERS is a keynote public speaking coach, transformation expert, awareness hellraiser, life coach, Trauma TBI, CPTSD mentor, train crash and cancer survivor, public speaking coach, Podcast host “Release the Genie” & best-selling author. His journey has taken him from corporate leader to kitesurfer to teacher on a first nations reserve to today. Paul’s goal is to inspire others to find their true purpose and passion.

“Mental health first aid should be as common as knowing CPR.”

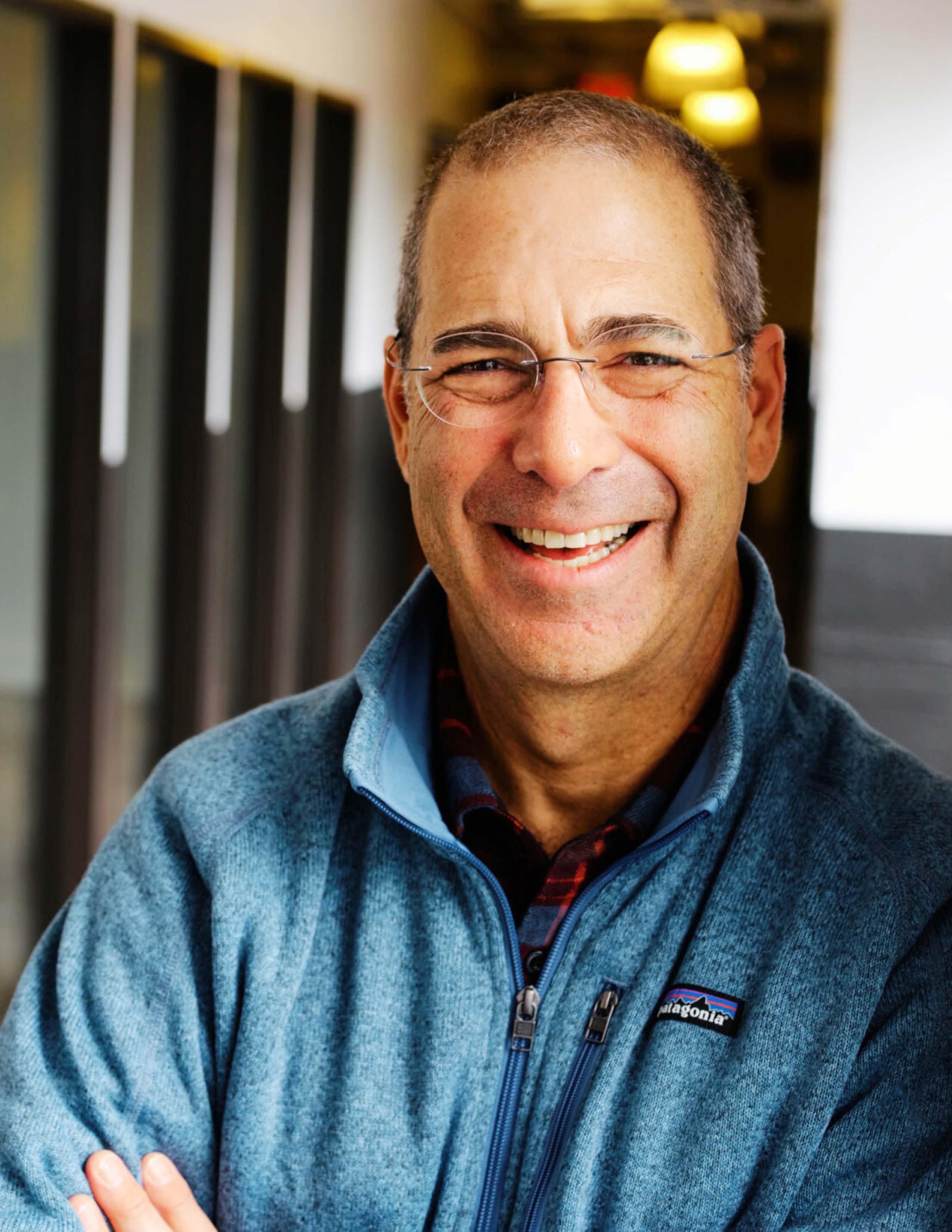

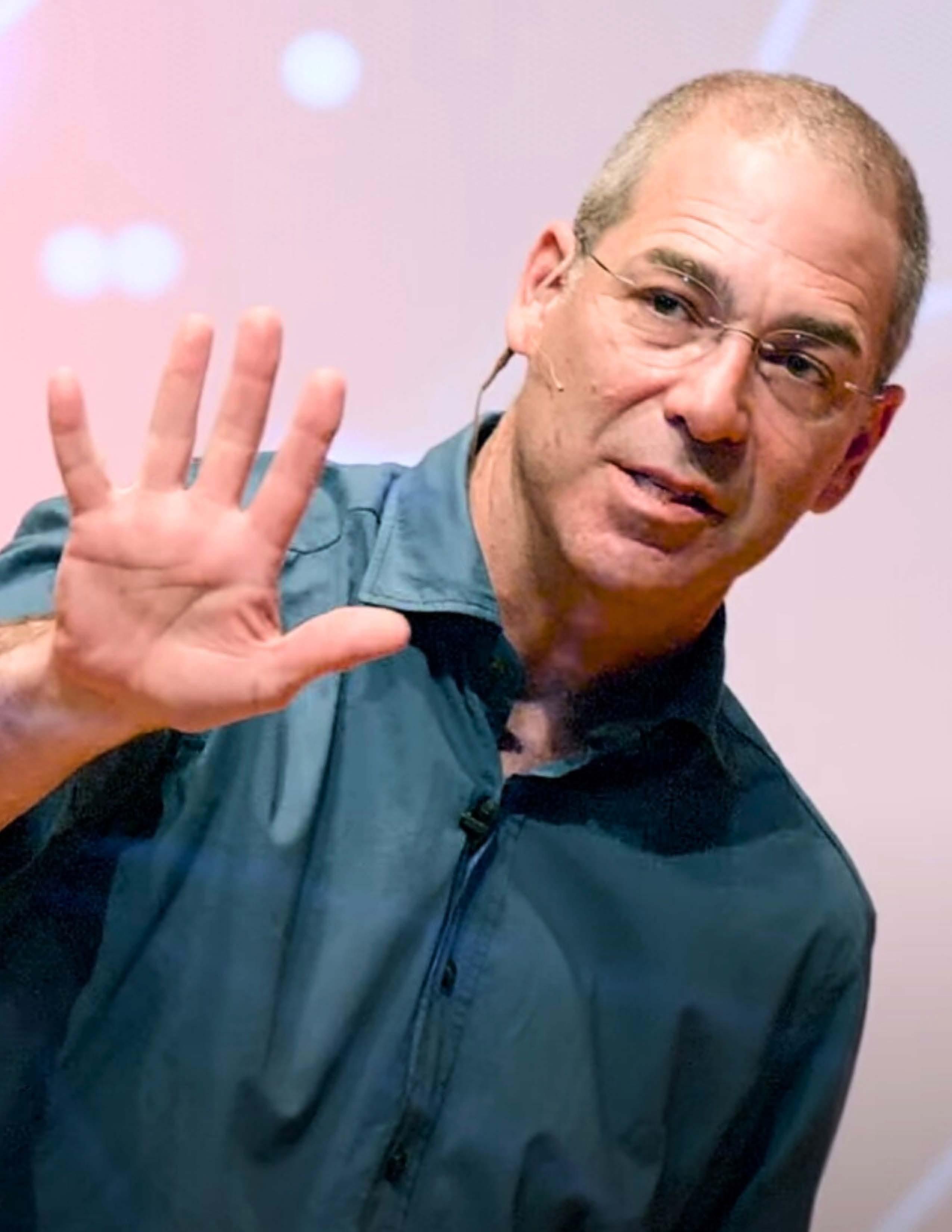

ADAM NEMER FOUNDER OF SIMPLE MENTAL HEALTH

From leading major health insurance companies to launching Simple Mental Health, Adam Nemer has never been afraid to ask bold questions—and seek better answers. As someone who’s wrestled with his own mental health, he’s putting his personal and professional experience to work for the benefit of others. Adam is empowering leaders by providing a new lens to look through when it comes to mental health.

ALLIÉ: You've worked at the highest levels of the healthcare industry, Adam. So first question for you today, what was the moment, whether a story or a statistic, that pushed you from managing a system to wanting to change things up, to reinvent it a bit?

ADAM: You know, I worked at an amazing organization, Kaiser Permanente, and the ethos of this organization, what they teach you is always trying to innovate in how we're delivering healthcare. So I was trained as an executive to

“When senior leaders normalize the topic of mental health... not just lives change, performance improves.”

ADAM NEMER FOUNDER OF SIMPLE MENTAL HEALTH

ALLIÉ: So let's talk more about these races that you were off to in creating Simple Mental Health. You intentionally stripped away the red tape and built something rooted, dare I say, in trust. What's the first barrier that you had to dismantle, not for any of your clients or people that you work with, but within yourself to make this vision real?

ADAM: The thing that holds us all back in the space of mental health, mental well-being and why the less than a half of us who need help get help, it's all about stigma; just these long term societal historical stigmas that we've just embedded in our organization. And there's things that we can do to normalize the topic of conversation in the workplace and there's some very remarkably simple things that you can do. And it's all about what I learned, it didn't happen for me on purpose. I didn't want this to happen and I didn't go about trying to do this, but what my lived experience taught me was that when a senior executive at a company is open and honest about what's going on with their mental health on a daily basis, like everyone in my organization knew I was struggling and I would be in a budget meeting for a multi-billion dollar health plan and say, “Guys, I got to walk out. I'm having an anxiety attack.” I got to go for a walk. That level of transparency.