AWARENOW

THE WORLD'S OFFICIAL MAGAZINE FOR CAUSES

A CATALYST FOR CHARACTER AND CHANGE

A CATALYST FOR CHARACTER AND CHANGE

AwareNow Magazine is a monthly publication produced by AwareNow Media™, a storytelling platform dedicated to creating and sustaining positive social change with content that inspires and informs, while raising awareness for causes one story at a time.

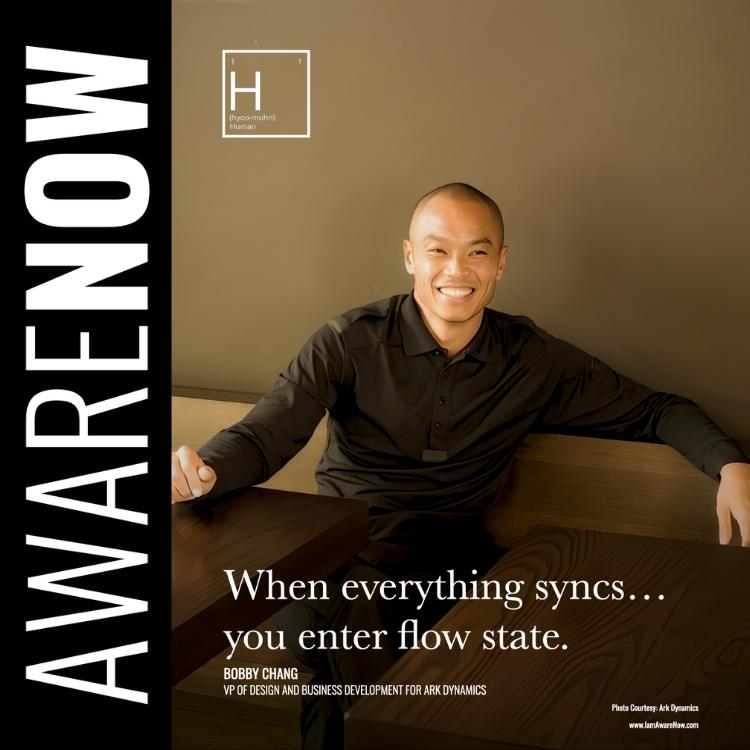

BOBBY

VISION

PAUL

“It’s not whether you get knocked down, it’s whether you get up.”

Vince Lombardi

In this edition of AwareNow, we turn our attention to sports — not just as games won or records broken, but as a lens into the human experience. Beyond the roar of the crowd and the numbers on the scoreboard are stories of mental health struggles, triumph over adversity, identity reclaimed, and resilience redefined.

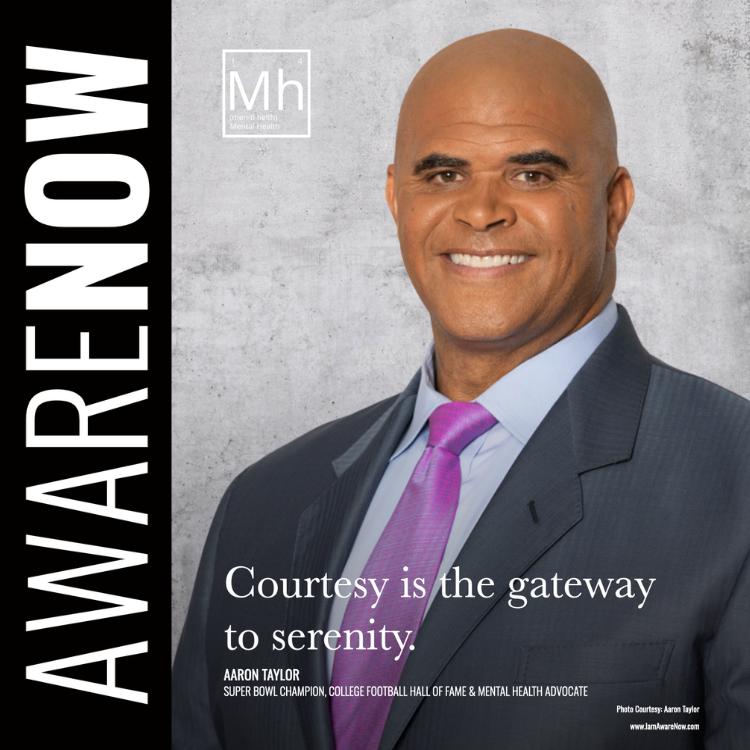

Our cover story with Aaron Taylor reflects this truth, as he opens up about the mental toll of the NFL and the journey beyond the Super Bowl. His story reminds us that the real battles aren’t always on the field.

AwareNow Sports exists at this intersection of athletic excellence and the human cause. From the Super Bowl to the Paralympics, from playgrounds to professional arenas, every athlete carries a story that transcends the field of play.

Always aware. Always free. AwareNow… More than ever.

ALLIÉ McGUIRE

CEO & Co-Founder of AwareNow Media

Allié McGuire began her career as a performance poet, transitioned into digital storytelling as a wine personality, and later produced the Hollywood Film Festival. Now, as co-founder of AwareNow Media, she uses her platform to elevate voices and champion causes, connecting audiences to stories that inspire change.

McGUIRE

President & Co-Founder of AwareNow Media

Jack McGuire’s career spans the Navy, hospitality, and producing the Hollywood Film Festival. Now, he co-leads AwareNow Media with Allié, focusing on powerful storytelling for worthy causes. His commitment to service fuels AwareNow’s mission to connect and inspire audiences.

The views and opinions expressed in AwareNow are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official Any content provided by our columnists or interviewees is of their opinion and not intended to malign any religion, ethnic group, political group, organization, company, or individual. Stories shared are not intended to vilify anyone or anything. Their intent is to make you think.

* Please note that you may find a spelling or punctuation error here or there, as our Editor-In-Chief has MS and lost vision in her right eye. That said, she still has perfect vision in her left and rocks it as best as she can.

For more than a decade, Tri Bourne chased greatness on the beach—rising through the ranks as a professional beach volleyball player and representing Team USA in the Olympics, and redefining what resilience looks like in sport. But this isn’t just a story about volleyball. It’s about grit and grace, about the power of choosing your moment instead of letting the moment choose you. In this conversation, we look back on the climb, sit with the weight of the goodbye, and look ahead to what comes after the game— fatherhood, freedom, and the fire that still burns.

ALLIÉ: Tri, let’s start at the beginning—not necessarily with the first medals or the major match points before or after being part of the AVP or playing in the Olympics. Do you remember the moment when volleyball stopped being just something you did and started becoming a part of who you are?

TRI: Right. It's interesting looking back on it now, because when you're younger, you don't realize that that's what you're doing, right? You're creating this identity for yourself. I think if you knew that, maybe you'd go about it a little bit

“The circumstances are out of my control, so I can't stress out about that.”

TRI: (continued) with youth national team stuff when I was 16 or 17. So back then, it was just like something to do, something to play. But I think, obviously, when I went to college, I started getting notoriety and that's when it kind of clicked that what I'm doing on the court has a bit of a bigger impact outside of just myself. I'm representing a university and that kind of thing. And then when I went pro, I was on my own. And so I had that hint of playing for something bigger than myself, but now it was like, I get to start from scratch and make this professional career whatever I want it to be. And what that ended up being was just like, I wonder what it's like to be a world-class professional athlete. That's been my dream. I wonder what that is. And I had a realization that I didn't need to actually be the best athlete in the world to experience what it's like to be a world-class athlete. Obviously, there are some opportunities that you have to earn by winning and all that, but I could go about my business in that way. And when I decided that, I think that's when my identity started to kind of get glued to volleyball and I started to realize that, wow, this is like a big life move and a big thing that's going to set up the foundation for the rest of my life—the person that I've become on and off the court. And I think the biggest part in hindsight, looking back, is the challenges, the highs and the lows, and how I treated those, and how I learned from the lows, learned from the wins as well. But yeah, I think it started probably right when I realized that I had the potential to go professional and once I set on that course, I started building this new person.

ALLIÉ: It became part of you. Not just what you did, but part of who you are. So—14 years at this, on tour, playing in the sand with both the weight of dreams and also that constant grind of the reality of it all. When you look back, Tri, what was the hardest thing to carry?

TRI: Letting go of control, I think, was probably the biggest thing. With a lot of my successes, I gained this crazy confidence, but the circumstances changed year to year, month to month. So it got very frustrating with this almost perfectionism mindset where I wanted everything to go the right way and I visualized it going a certain way. And so when it didn’t, it was really hard. But then time and time again, I had to learn those lessons of it's not in my control. The circumstances are out of my control, so I can't stress out about that, and that's what was hard for me.

Then I got the biggest lesson, which was getting the autoimmune disease, having to step back from the sport in my prime for two years. That was a life changer because I had to spend so much time in my own head. I didn't have that outlet of the sport, of the exercise, the adrenaline, and all that. So that was probably the time where I made the biggest leaps in terms of realizing that my circumstances, my story, is just different from everyone else’s, and that's neither good nor bad. It just is what it is. And I had to really lean into my own story and being unique and special in my own way. So I think that's what it probably is.

ALLIÉ: Yeah, for sure. Control—it’s a hard thing to let go of.

TRI: Yeah, let go of the reins…

ALLIÉ: Letting those reins go is hard. So let’s go to the flip side of that then. Over the course of these 14 years, what's something from the game that you'll always hold close to you?

TRI: I think something I showed myself was just perseverance and resilience, and I learned a lot. And I don't have regrets, but obviously I’d do things differently in hindsight because hindsight is usually 20/20, right? But I think just the perseverance, the strength to go through the highs and the lows, and to maintain the integrity and always come back out of the lows and find the positives eventually, and always try—at least—to have high values and virtues and have

TRI: (continued) my actions follow those values, it just gave me a lot of confidence in my ability to overcome whatever is next. Whether it's having kids or whatever life throws at me, it gives me confidence going forward because I was able to face those challenges and go through them—not try to get around them or act like they weren't there, but just own it, face it. It's my challenge. It's my unique story. There's no comparison. I think I can use that going forward, and what might be even more valuable of all is that I can maybe pass it down to other people and I can help others with it.

ALLIÉ: Yeah, I know. And that's the course, right? It's never around, above, or below—you have to go through it.

TRI: Yeah, you can't dodge it. It'll just follow you until you face it.

ALLIÉ: Yeah, non-dodgeable. Let's make that a term. I'd like to switch gears for a moment. Gabby's been by your side through all of this—from the climbs through the chaos, from Naia's first steps to Mox's first breath. What does it mean to share this journey with her? Not just as your wife, but as your partner. What does it mean to you?

TRI: I think now that it's over—you know, when I'm in it, we're just kind of going for it. But when I get to step back and really look at it, and right now, obviously being at the end of my career, it's looking back a lot and just realizing that I had it so good. Somehow she found value in pursuing this life that was about me pursuing my dream. And I think that's probably rare. I think if she wasn't feeling fulfilled in that, then I would've had to pivot and things would've gone differently. And maybe I’d feel like I had more to give, but I just feel super grateful. And we're as close as ever—even closer—as we have kids.

I know that the stresses get higher, but because of the highs and lows we've gone through, there's just no hesitance in our commitment and our next steps together or whatever it might be. It's like, we're just fully committed to this life together. It's all we know and it's all we want to know. And she carried a lot of the heavy-burden stuff that I didn't have the energy to carry—whether it was calling the doctors for me, remembering what they said, taking notes, or reminding me of things. And she never really cared about what I did on the court. She just wanted me to go out there and “do what you want to do. You enjoy it, so go do it.”

But when you come back, I don't really care if you won or lost. She cares less. So that took pressure off of me, it allowed me to play free and just do it for my own reasons and then come back and be home. And then also, I got to have a kid while having a career as well because she's holding it down. And so it's cool, and the thing I'm most excited about now is kind of supporting her in that reverse role to whatever extent she's excited to work—which she’s really excited about right now. So it's cool. We get a little trade-off and now I kind of get to see how she did it, how to return the favor, and hopefully do it well.

ALLIÉ: That's awesome. We know life is all about balance, but when you have a relationship like the two of you have, it’s about just keeping that balance and—

TRI: Yeah. I just feel super grateful, like I hit the jackpot.

ALLIÉ: Yeah. Well, I think you both lucked out very much to find each other. So let’s go back to you, Tri. Stepping away at 35—not because you have to, but because you choose to—what was it that gave you the clarity and the will to retire while you’re still at the top?

TRI: Just turned 36, by the way. So now I'm on the back half. But it's been a long time coming, and I feel like whatever life's energy was working to give me this clarity, it's been a slow burn. And I push through a lot—I’m very determined once I set myself a goal and I think that I'm capable of it. So I think that life realized, we're going to have to give this guy a lot to make him see the clarity and stop, which maybe if I'm not as hardheaded going forward and I learn from this, I won't need such hard lessons that life has to bring me. We'll see.

I accomplished more than I ever could've imagined, and so anything else would just be kind of selfish—I just don’t need it.

TRI: (continued) But I think it's like this respect for the body. If it keeps getting hurt, obviously I'm not being my best version of myself. I'm stressed out for long periods of time. I'm just not comfortable. I'm not being my best version of myself. And then that sacrifice started turning into not allowing me to do my best on the court. And then it's like, okay, now I'm just selfishly doing this. It's not helping my family. I'm not necessarily going to achieve these dreams if the body's not on board.

The family is fully committed to it, but it's my responsibility. Them not telling me it’s time to stop puts it on me. It's my responsibility to know when to stop and what's best. And just realizing that the body’s good—it just kind of gave it. In terms of competing at the level I like to compete, the body gave me all it could for that particular style of training. And then the family gave me all the time I needed as well.

So, there just wasn't much else to gain and I felt like going forward is kind of just a little bit selfish, because we can create more opportunities for Gabby and I can be there more for the family. But also, it's almost like an egotistical chase for more accolades and success when life's clearly telling me, hey, it's time to shift. So it's just a matter of listening.

But there are so many signs now, and I have done enough self-work to realize it is just time. I can hear the messages, I can hear the signs, I know that I'm good. I accomplished more than I ever could've imagined, and so anything else would just be kind of selfish, it feels like, and I just don't need it. Like, let's move on. We don't need to beat a dead horse, as they say.

ALLIÉ: I just think that speaks volumes about you—not only as an athlete, but as a person, as a father, as a husband. How does it feel to reclaim your narrative on your own terms? Because so many people go and go and go, and then it’s like “uhh,” but you’re just saying, no—it’s my choice. How does that feel?

TRI: Yeah, it does feel good. I definitely feel a sense of relief and excitement knowing that I took the time to think about it and give myself the opportunity, at least, to step out on my terms. Because I was able to do that, now I get to make an announcement, I get to spend the month on my gratitude tour—I’m calling it My Last Few Weeks—just thinking back and being grateful and sending messages of thanks to whoever I can. And I get to enjoy it and I get to celebrate the end of this.

Because I chose to do it early enough, it wasn’t forcing the sport to keep sending me out. And then, you know, the writing's on the wall and people can see like, what are you doing? So, it feels good and it feels like another move where I am doing the right thing, not necessarily the thing I 100% want to do, it's just the right thing, which doesn't always feel good. Like, it's hard for me to retire and see everyone else continue and whatnot, but I know it's the right thing because I've done the self-work and I know that I want to live a life of following those values of mine.

ALLIÉ: So awesome, Tri. Just a couple more questions. Now that the jersey is coming off, who is Tri now without the sport, the stats, or the sand? Who is Tri?

Exclusive Interview with Tri Bourne https://awarenow.us/podcast/the-final-serve

TRI: Yeah, it’s a good question. I'm definitely in a state of open-mindedness. I don't necessarily want to force that definition or try to define who I am, but continue to just live a life of my values and observe who I am outside of volleyball rather than trying to force it and control it. There are so many of these lessons that I learned in sport that I know are going to translate and have given me this confidence.

I don't know why I'm confident, I don't know what I'm going to do, but I'm confident in my ability to adapt and figure it out. But I know that I’ve got to be patient and I’ve got to just let it come to me and take the time to let the muddy water settle and kind of meditate on it. But it's a cool feeling too because for the first time I'm not going to be a volleyball player—I'm only going to be a man of my values, which is family and all that. So it'll be a good headspace to be in, I think, if I can really be present, which takes a little bit of work.

ALLIÉ: Yeah, it does—especially since you've been so regimented for so long to say, “this is my next, this is my next.” But it's not your next, it's your now. What is your now? And you have full control of that now.

So we looked at now—looking forward—how do you hope those kiddos, Naia and Mox, will one day tell the story of the man you became after the game? What do you want them to say of you?

TRI: I think my best version of parenting is kind of like sport—it’s me just being present. That's when my best version of myself comes out in sport, and so I kind of translate that into life and especially parenting. If I can be there, giving them my attention, I trust myself to tell them the right things, to do the right things. I don't know what those are all going to be, but I think if they're looking back and saying that, “he was just there for us, present, and he gave us his attention”—that's my best chance of them really loving how I raised them. ∎

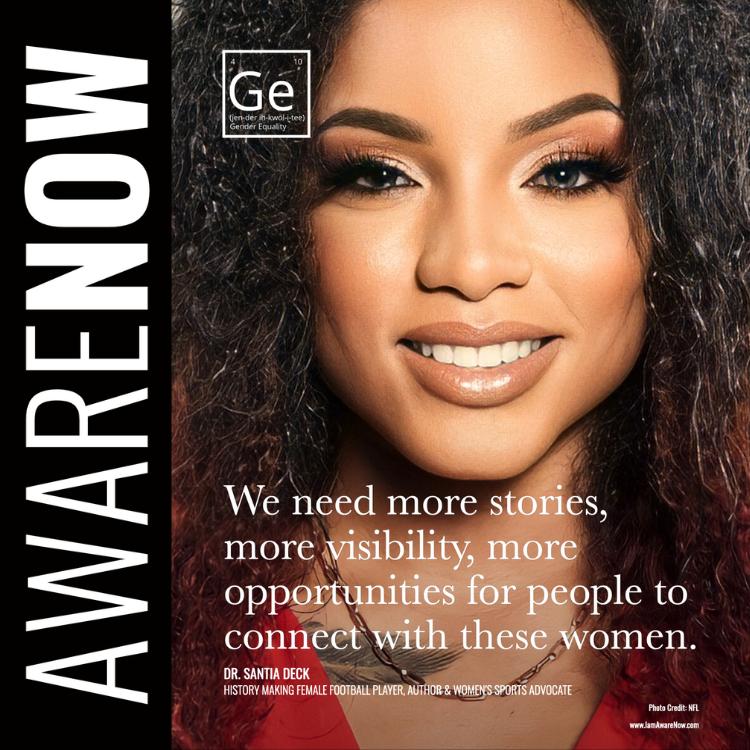

Santia Deck doesn’t just break records—she breaks barriers, builds businesses, and redefines what it means to be a modern athlete. From her days as a collegiate track star to becoming the highest-paid woman in professional football, and now a founder, author, and advocate, her journey is as dynamic as it is disruptive. In this conversation, we talk about what sports taught her, what success means now, and how she’s using her platform to create space for other women to rise.

ALLIÉ: Let’s start here, Santia. Before the contracts, the companies, and the millions of followers—there was a girl on the track who wanted to prove something.

SANTIA: Absolutely.

ALLIÉ: When you look back now at that moment—at that girl—what do you think sports unlocked in you that changed

“That ‘do or die’ mentality from sports carried over into my entrepreneurial life and built this relentlessness in me.”

SANTIA: I love that question. I’d say it gave me the ability to persevere, to handle trials and conflict, to work within a team, to understand leadership, and to sometimes put other people’s needs ahead of my own. It taught me humility, too. I owe so much to that little girl who started at five—not knowing what world she was stepping into. All I knew was I wanted to be as fast as a cheetah. I never imagined it would lead me here today. I’m just grateful.

ALLIÉ: And that’s a big word—humility. Sports is certainly steeped in it.

SANTIA: Absolutely.

ALLIÉ: You’ve broken records, launched brands, and built platforms. But I imagine some of the most important things you’ve built came from moments no one saw. So, when it comes to your character, Santia, what did being an athlete build in you—specifically you?

SANTIA: Wow. These are great questions. I think my journey through sports was… unique. I was very good— sometimes maybe too much so—because I was laser-focused on my end goal. Back then, that goal was to be an Olympian. If something didn’t align with that, it was a distraction, and I cut it out. I even ended friendships in high school because I felt they were pulling me away from the Olympics.

That focus became one of my strongest traits, and it’s still with me today. If I have a goal, that’s where all my attention goes. Anything outside of that just isn’t a priority, and if I have to cut it off, I will. I was also the kind of kid who didn’t understand procrastination—my mom loved that. I knew that if I wanted to go outside and play with my friends, I had to get my work done. Sometimes I’d work weeks ahead just so I could enjoy that time without worrying about homework. I was always doing extra, studying harder, and making sure every assignment was finished early.

There’s a good and bad side to that. The bad side is not knowing when to stop—when to tell myself, “You’ve done enough.” I’m always looking at the goal. But in business, that drive has been a huge asset. If I want something, I’ll find a way to get it, no matter what it takes. That “do or die” mentality from sports carried over into my entrepreneurial life and built this relentlessness in me. I understand what it takes to reach a goal, and I’ll do it—even if it comes at a cost. But I’ve learned rest is important too. My husband has been a big influence there. He’s taught me to breathe, unwind, recover, and then apply what I’ve learned before jumping back in. As entrepreneurs—especially women entrepreneurs —I think we often feel like we have to prove ourselves by doing more and more until we burn out. I’ve burned out several times, both as an athlete and as a business owner.

I’ve had to go back and talk to that younger version of myself—the one who believed in going harder, faster, stronger. I tell her, “Yes, that mindset was drilled into you, but it’s okay to rest. It wasn’t okay then to ignore it, and it’s not okay now.” Coaches rarely emphasize recovery and rest, but it’s just as important as training. Now, I make myself take walks, step away from the computer, and take a few hours off when I need to.

So, yes—I may have gone on a little rant—but what I’ve really carried from sports is that relentlessness, that resilience, and the ability to focus. Those are my biggest takeaways.

“The truth is, if I don’t know who you are, I can’t be a fan.”

ALLIÉ: I think little Santia and little Allié need to take a walk together and just relax.

SANTIA: Yeah.

ALLIÉ: Because little Allié doesn’t pay attention to all that—and she needs to listen up. Okay, let’s talk about Winning Her Way. You’re creating a space for female athletes to be seen, heard, and—big word here—valued.

SANTIA: Yes.

ALLIÉ: Valued not just as players, but as people… people with power. What fueled that mission for you? Because it’s one thing to make your own mark—but what made it important for you to help other women make theirs?

SANTIA: It actually started during an interview I did with a former NBA player. He asked me what I thought needed to change in women’s sports for it to move forward. I went straight into storytelling—because I believe it’s everything.

We all know the big names: Serena, Simone Biles, Caitlin Clark, Angel Reese. But there are so many more incredible athletes—in Nigeria, Vietnam, and all over the world—who are just as amazing, but don’t have the platform. The truth is, if I don’t know who you are, I can’t be a fan. I’m not buying your merch, I’m not coming to your games, I’m not sponsoring you—because I don’t even know you exist. You can’t have five or ten athletes carrying all of women’s sports. We need more stories, more visibility, more opportunities for people to connect with these women.

In men’s sports, you can know everything about an athlete—where they were born, their star sign, what their parents did. With women’s sports? That’s rare. Outside of Serena Williams, whose story we know thanks to a recent movie, I couldn’t tell you much about the parents of Simone Biles, Juju Watkins, Angel Reese, or Caitlin Clark. And if I can’t relate to you, if I can’t see myself in you, it’s harder to become a fan.

So I explained all this, and he just laughed and said, “Nobody cares about women’s sports.” That lit a fire in me. I thought, “Be the change you want to see.” That’s when Winning Her Way was born.

I started interviewing amazing female athletes from all over the world—different levels, different backgrounds. It grew into a platform with social media, newsletters, and a media hub, all dedicated to amplifying these voices. And it’s not just for the stars—it’s for the underdogs, the high school girls, anyone who deserves to be seen and heard.

Part of this is personal. I have a twin brother, so I saw the differences in what he got versus what I got. It never felt good. My mom did her best to shield me from it, but I still noticed—like when he could walk into a sports store and find everything he needed, while I struggled to find sports bras, supplements, or even shoes in female sizes. Those moments stick with you.

So Winning Her Way is my way of helping the next generation of girls feel seen, valued, and supported—so they know their stories matter, too.

ALLIÉ: To your point—if you want to be the change, you have to rewrite the narrative. You have to use the power of storytelling to make people feel. And I love that you’re helping female athletes navigate life beyond the field.

“I looked in the mirror and realized: I don’t completely know who I am without sports.”

SANTIA: Yes. That’s important.

ALLIÉ: Because there are identity shifts… we are so often what society sees us as, and nothing more. So—identity shifts, business moves, mental health struggles—was there a moment when you had to redefine who you were outside of sports?

SANTIA: Absolutely. One of my most painful memories was in 2022, tearing my ACL. To this day, I’m still not 100% over it. It’s a grieving process—and honestly, I don’t think athletes ever truly get over it, especially when it happens unexpectedly, without you doing anything “wrong.” When it’s out of your control, it cuts deeper.

At the time, I was at the height of my career. I was lined up for a Coca-Cola Super Bowl commercial, playing in the Super Bowl Celebrity Game, doing all these big things right as flag football was blowing up. And then—gone. It was dark. I had a shoe company, I was an influencer, I had my “plan B” ready… but I didn’t realize how much of it was still tied to being an athlete.

I looked in the mirror and realized: I don’t completely know who I am without sports. I’d been an athlete since I was five. The person I’d been my whole life was suddenly… gone. And even if you recover physically, mentally you’re never quite the same. You don’t cut as hard, you don’t move as freely—the wildness and freedom you had before is just… different.

So, I had to ask myself, “Who are you outside of this?” It took time, faith, and an incredible support system to realize: you’re more than an athlete. You’re an author, a wife, a friend, a daughter… You’re someone with a voice, with values, with purpose beyond the game.

I thought my purpose was to inspire little girls to play sports. Now, sports will always be part of me, but I see a bigger picture: financial freedom, using my voice, impacting people through my character and what I stand for. Since then, I’ve written my book More Than an Athlete, met my husband (something I never would have made time for while competing), built new friendships, and faced some truths about the wear and tear sports had put on my body. I had to ask—do I want to be able to pick up my grandkids decades from now? That meant changing how I live now.

It’s still not easy. I still cry sometimes. It really is like a death—you grieve, you adapt, and you keep going.

ALLIÉ: Yeah. And that’s such a powerful comparison—that there’s a grieving process. It’s like getting a scar. It may fade, but it’s always part of you.

SANTIA: Absolutely. When I look at my knee, I see it—and it’s a reminder. I think about the athletes who don’t have what I had—no platform, no plan B—and the mental chaos they must go through. It’s like going to war. It’s PTSD. Your brain can’t comprehend that you’re no longer under the lights, hearing your name, living that life. One day you’re an athlete, the next you’re a “regular” citizen. Nobody prepares you for that.

Exclusive Interview with Dr. Santia Deck https://awarenow.us/podcast/winning-her-way

SANTIA: (continued) And that’s why I do what I do. Because honestly, I don’t know where I’d be without the support I had. The weight of it—it’s so heavy. It’s hard to even explain.

ALLIÉ: The fact that you can speak to it—you can name it, call it grief—instead of wrestling with some nameless thing… that’s powerful.

SANTIA: Yeah.

ALLIÉ: Sorry, we’re getting deep…

SANTIA: No, you’re good. This is good. It’s a conversation that needs to be had.

ALLIÉ: It does. Okay—one more thing for you today, Santia. From cleats to crowns, you’ve walked a path no one else has. We all have our own path, but yours—right now, in this season of your life—what does the “W” word, what does winning look like to you?

SANTIA: That definition has changed a lot for me over the last five to ten years. For me now, winning is about impact —how much of a difference you can make in the world.

In sports, your impact used to be physical. Now, it’s about finding other ways to create that same level of influence. For me, that means helping one million athletes build their brands, understand financial literacy, and create a legacy off the field—so they have a plan B and aren’t lost when the game ends.

I also want to help take women’s sports from $1 billion to $100 billion. I know—it sounds crazy. But if the most powerful leaders in women’s sports came together and pooled our resources, I truly believe it’s possible. I hope to be a small wave in that ocean—while also making sure athletes know who they are, what their purpose is, and that they’re more than an athlete. I want them to feel seen, heard, and understood. To realize they have the power to impact more people than they can imagine—and that their worth isn’t in stats, points, or touchdowns. It’s in who they impact and how they change the world. ∎

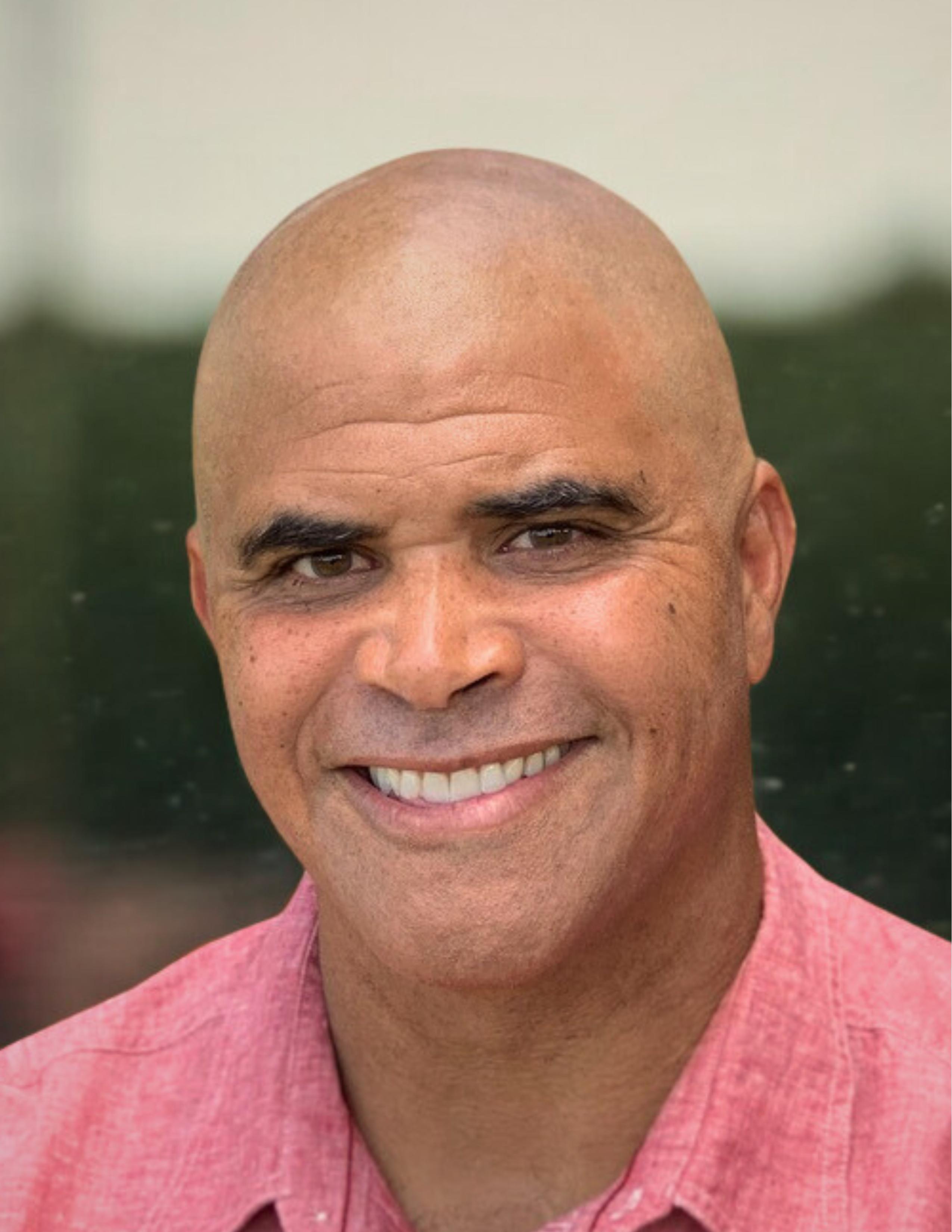

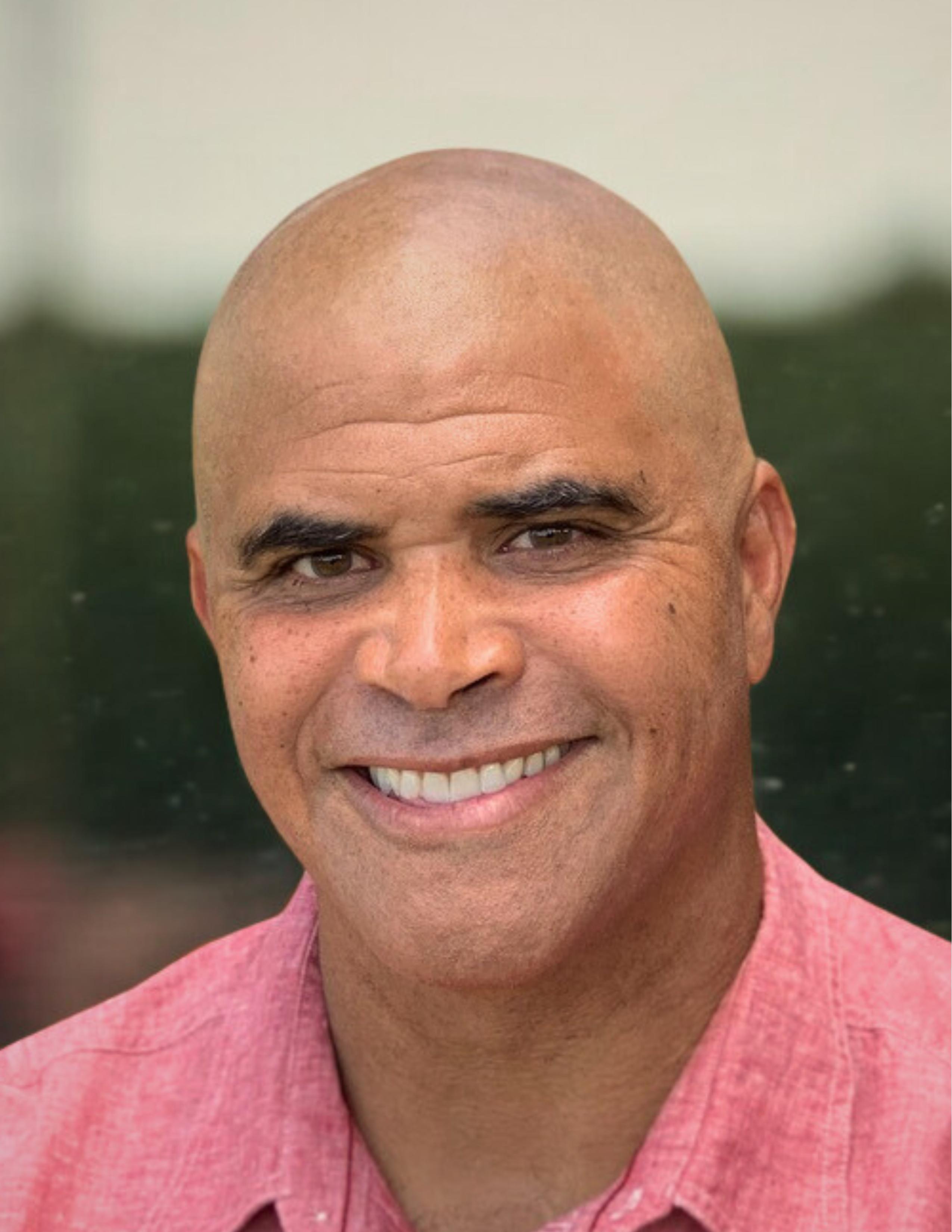

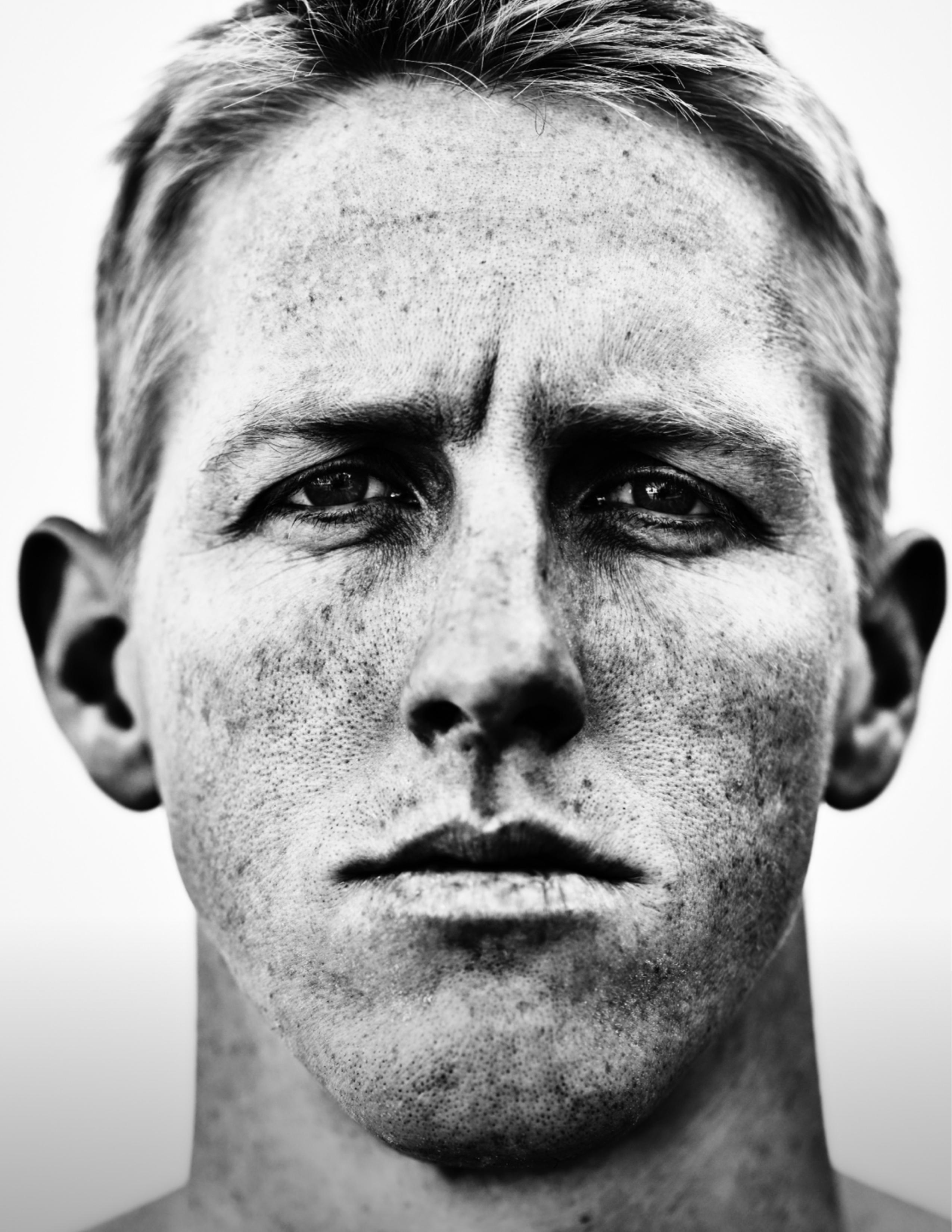

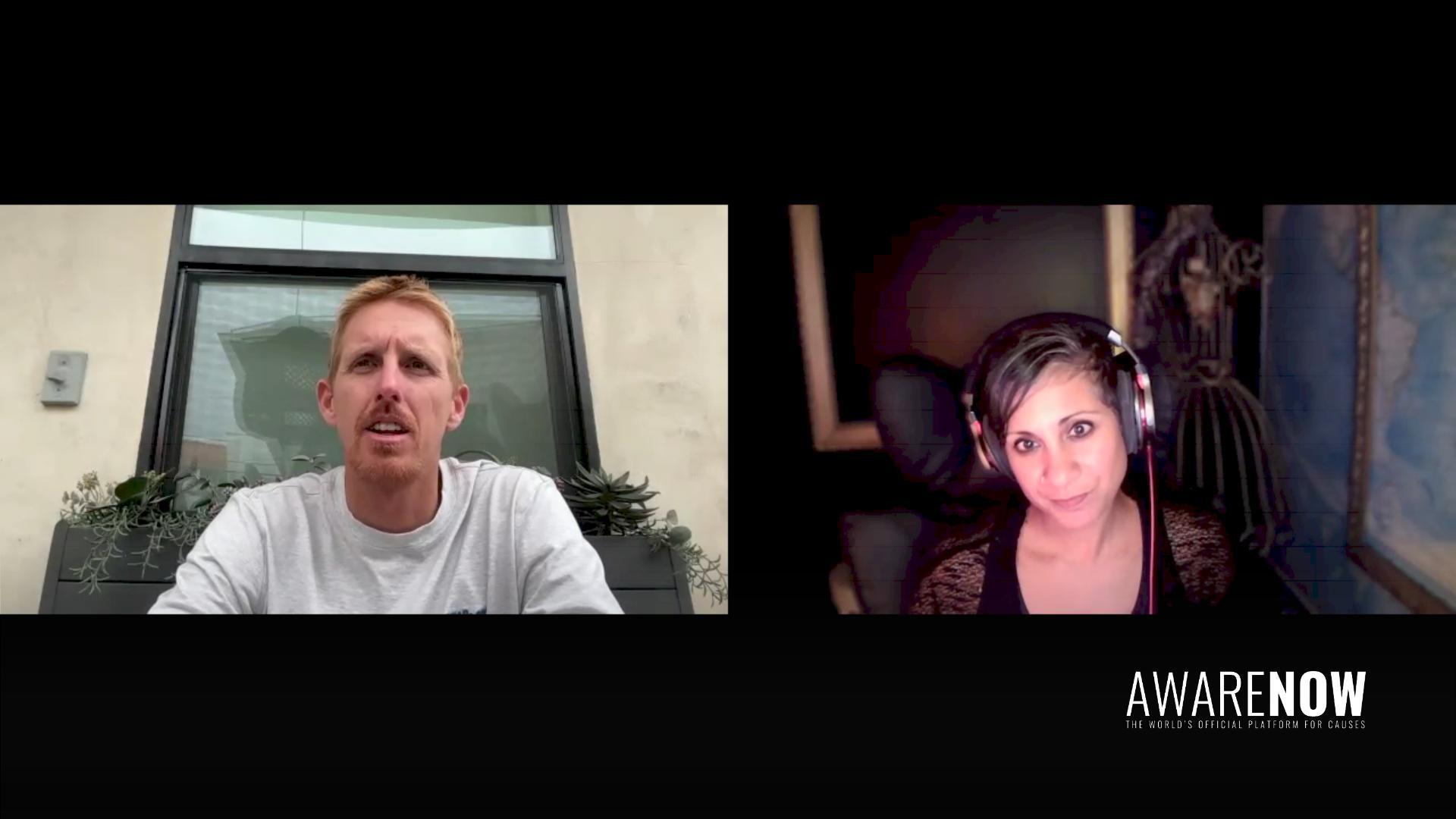

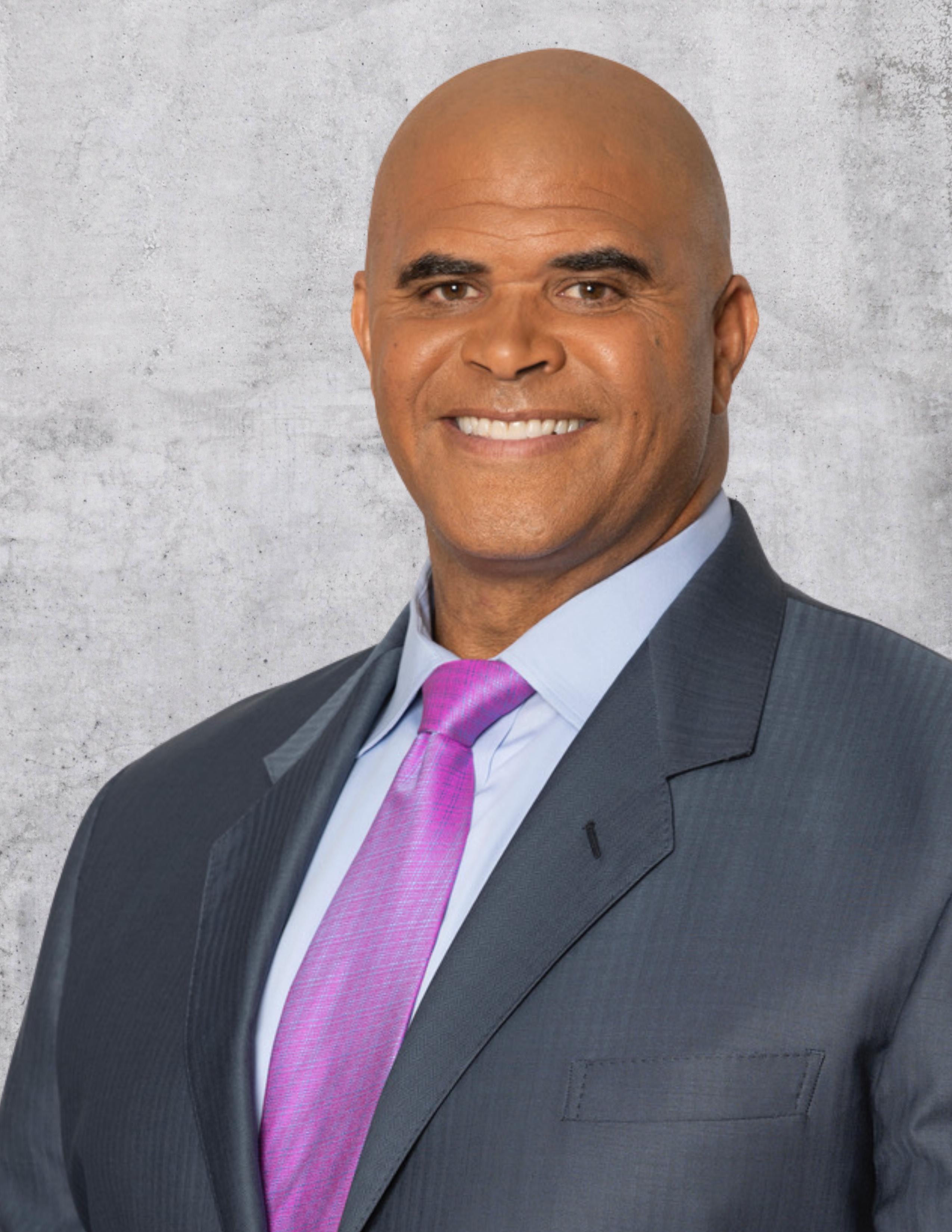

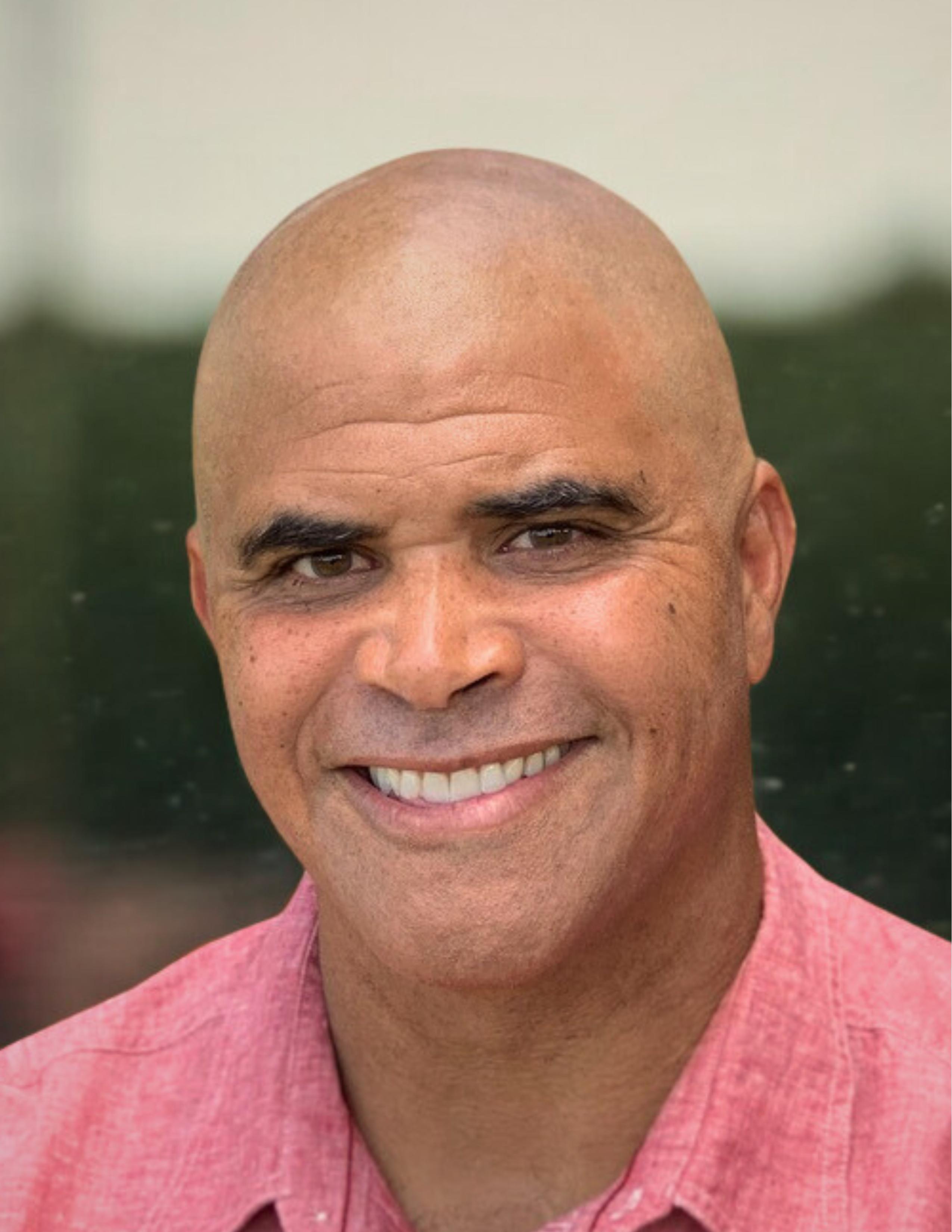

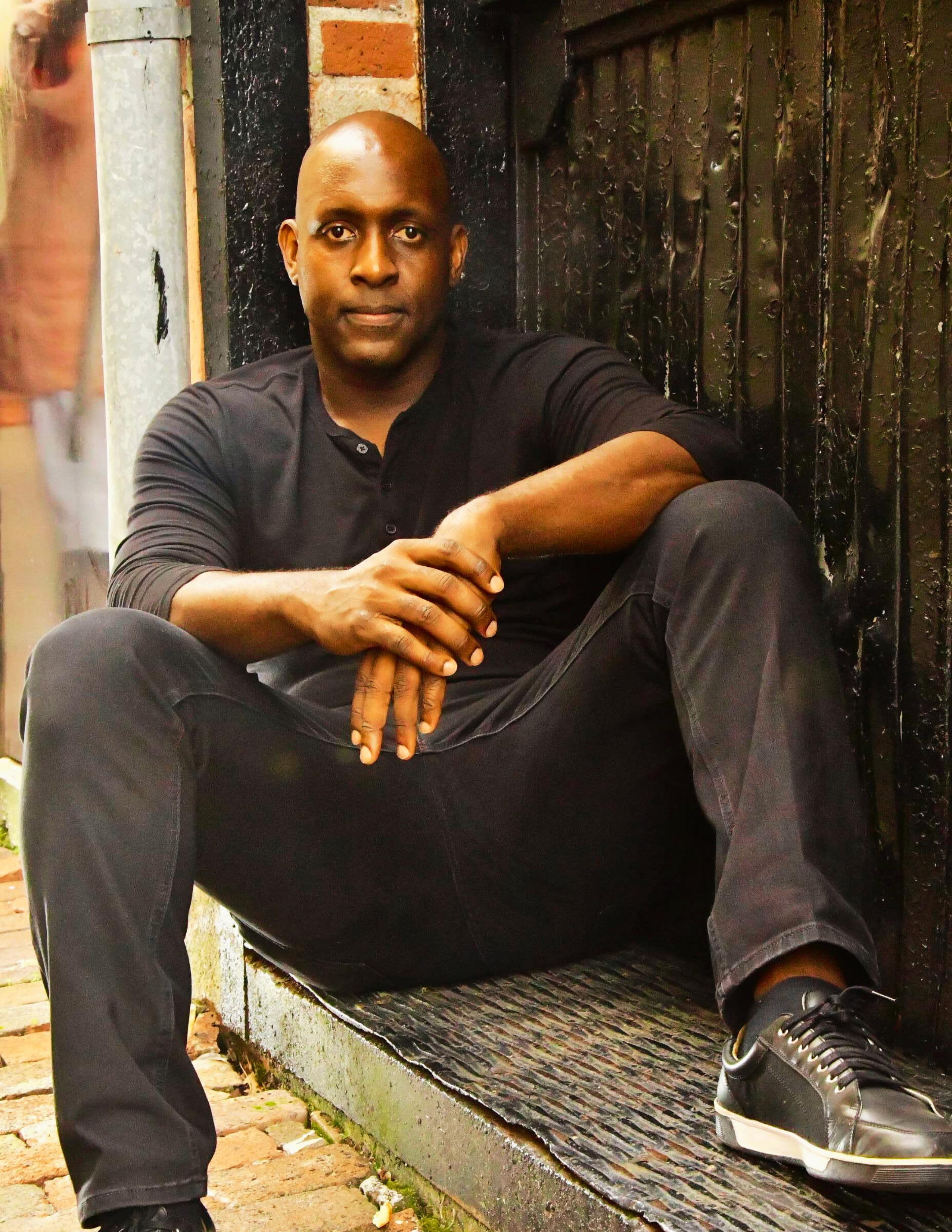

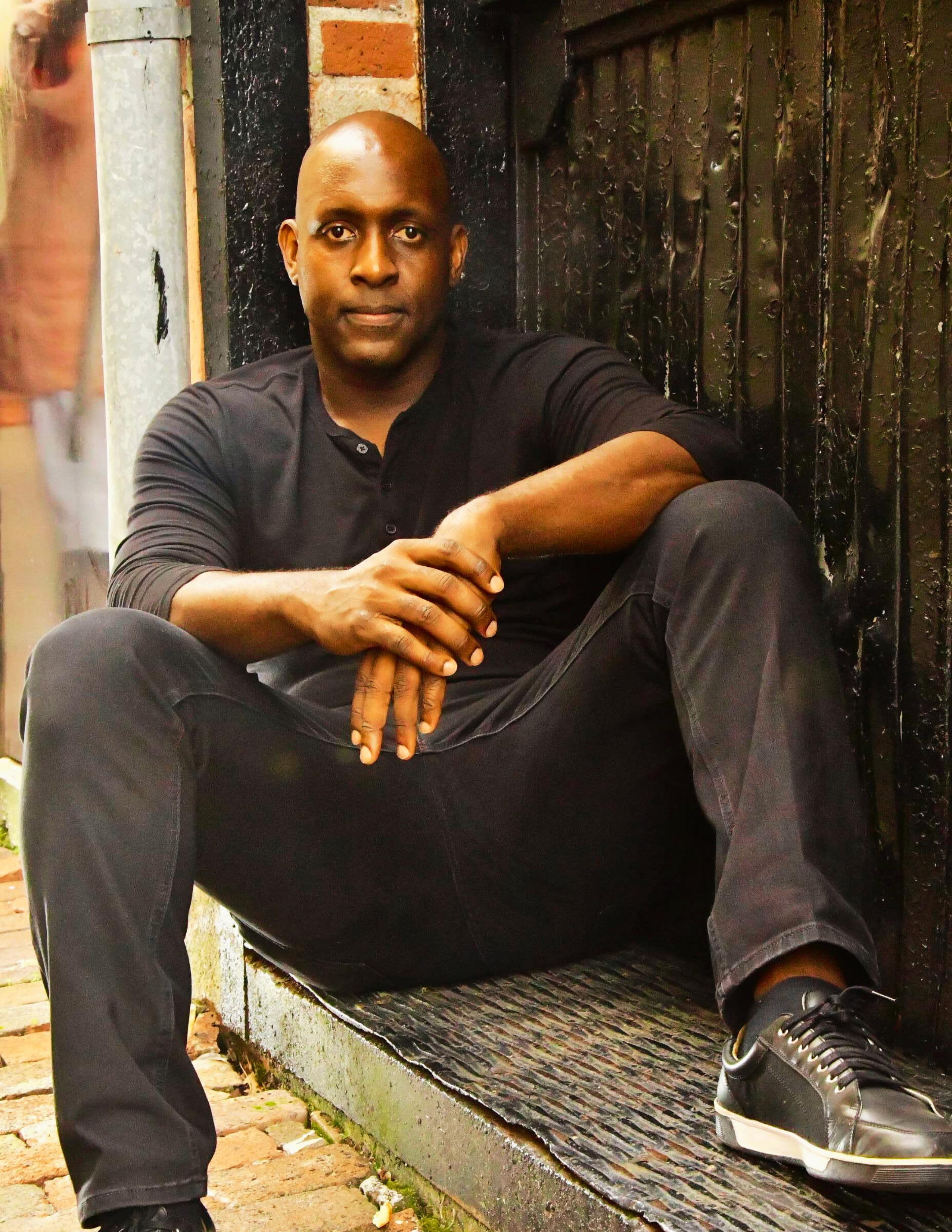

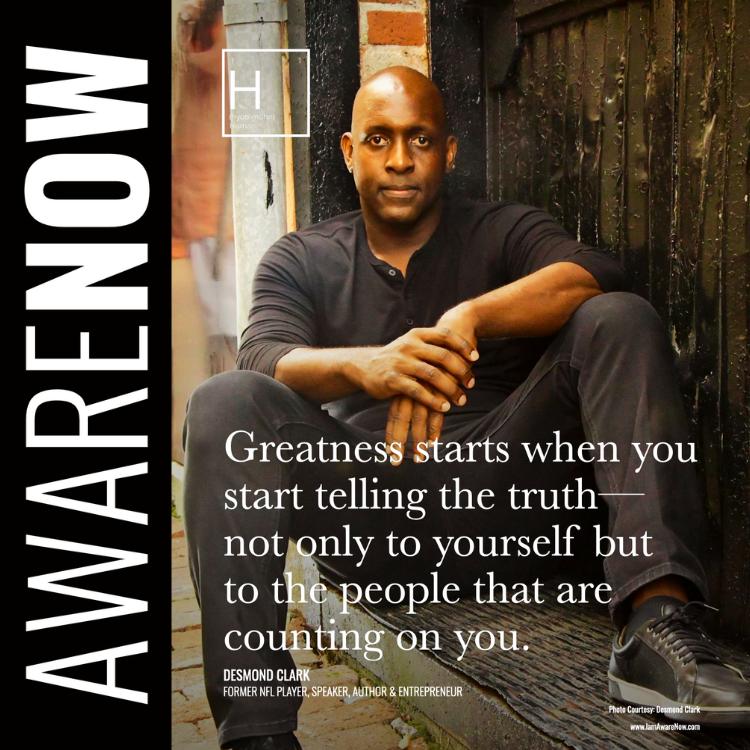

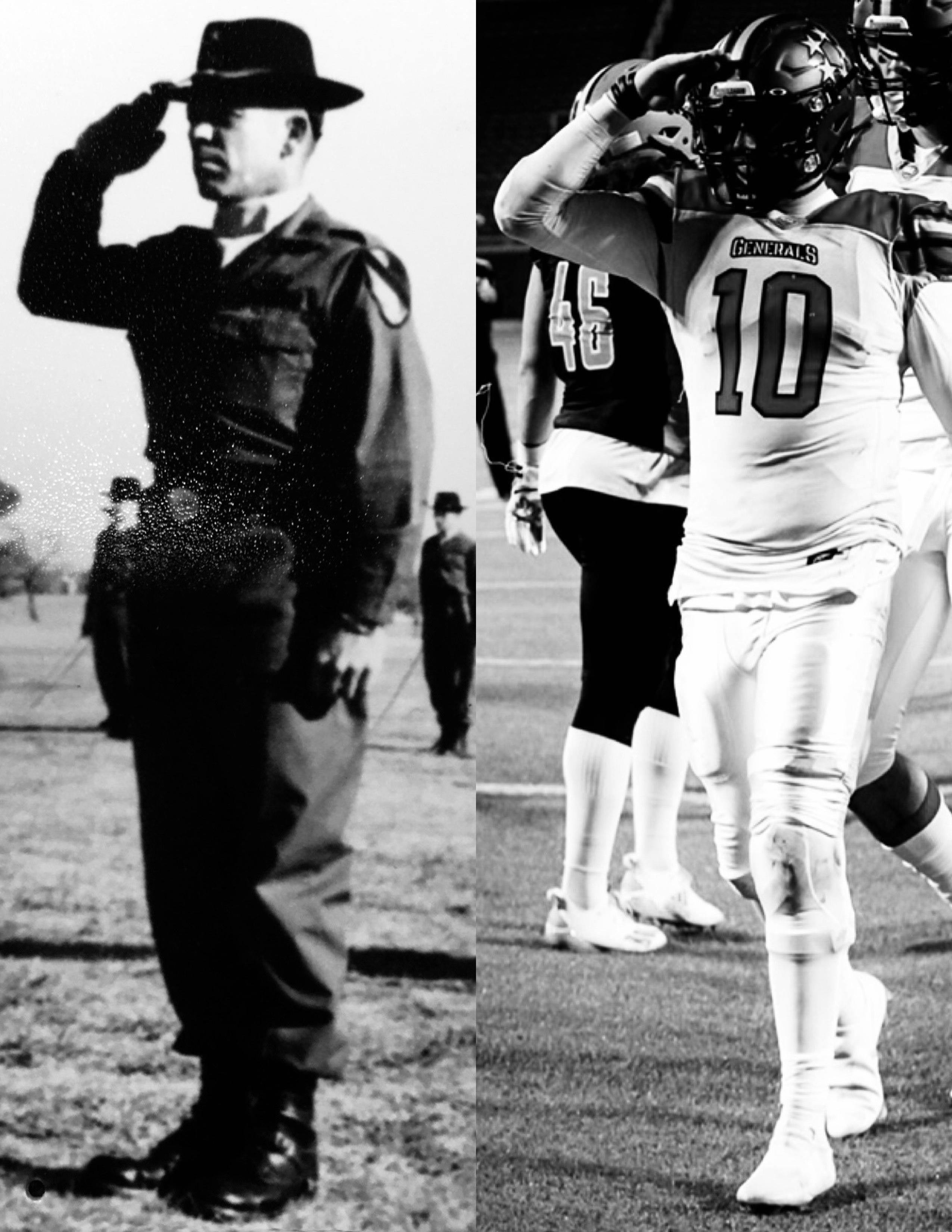

Aaron Taylor is a College Football Hall of Famer, Super Bowl champion, and one of the most respected voices in the game. A two-time All-American at Notre Dame and Lombardi Award winner, he went on to play in the NFL before injuries ended his career early. But Aaron’s most powerful work began off the field—becoming an advocate for mental health and redefining what strength looks like beyond the helmet and pads.

ALLIÉ: Let’s start here—with me admitting the truth: I’ve never won a Super Bowl. Most people haven’t. You, my friend, have. So, take me back to that moment. What did it actually feel like to reach the peak of what so many people dream about?

AARON: That’s a great question. The simple answer? It felt weird. Surreal. Unlike anything I had ever experienced. I started playing sports when I was six or seven—officially, anyway. I’d been playing in the backyard since I was probably two. But I had never won a championship at that level. I’d won high school championships. We’d finished as high as number two in college. But every kid who plays football has that dream—posters on the wall, daydreams in

“It was the last thing I would have ever asked for, but it turned out to be the first thing that truly worked in getting me back to myself.”

For me, at 28, that moment came in the 1996 season—technically January 1997—against the New England Patriots. We had a two-touchdown lead late in the game and were in our “four-minute offense,” trying to run out the clock. I remember Brett Favre taking the snap, dropping to one knee, and with less than 30 seconds left, we knew for certain we had won. Confetti started to fall, and it was like a surreal slow-motion montage of everything I’d worked for: every offseason workout, every winter conditioning session, summer training, four or five knee surgeries—all of it.

It felt like standing on top of Mount Everest. That was it. We did it. No next week. No “one step closer.” Just… done. NFL Films even caught me pirouetting through the confetti because I instantly became a little kid again. Ironically, much of my professional career hadn’t been joyful—it was work, pain, and stress. I’d lost the intrinsic joy I’d had as a kid. But for those brief 30 to 45 seconds, all of that melted away. I was that eight-year-old boy again, living the manifestation of his childhood dream.

ALLIÉ: Thank you for sharing that. I felt every detail right along with you. I imagine that after a moment like that, there must have been a strange kind of silence—when the noise fades, when the cameras stop flashing. They say when you’re on top, there’s only one way to go. So when you think back to after the win, Aaron, what was a moment when things began to slide? Because we can’t stay in that euphoric space forever.

AARON: It’s interesting—the greatest silence I felt after the Super Bowl was the silence of my girlfriend, watching me receive the phone number of another woman right in front of her because I was so intoxicated. I can say that now with a smile—and even a little joy—only because I was a glorious, beautiful train wreck. It certainly wasn’t one of my proudest moments, but it represented just how far away from myself I had drifted.

The NFL doesn’t require you to live that way, but it certainly invites it. I wasn’t disciplined or strong enough to resist those temptations. Thankfully, I didn’t cross even more lines or take it further than it already had gone. But that moment was emblematic of what would eventually become my fall from grace—when I shut it all down completely.

When you retire from the NFL—or from anything where you’re part of an elite unit—there aren’t many people on the planet who know what you know or can do what you do. You have this rare skill set, you’re compensated extremely well, and you love what you do. When all of that goes poof in an instant, you’re left in a vacuum you’ve never experienced before. For the first time in my life, I felt insecure, unsure of what was next.

The football world is highly cadenced—nothing is planned further than three months out, maybe six at most. Suddenly, I had no idea what was coming. At 28, being “all grown up” felt harrowing. So, I did what many respectable, “successful” people do—I started drinking a lot of Wild Turkey, five or six nights a week, trying to fill the void.

I was hugely depressed. I had no sense of purpose, no identity. My income stream was gone. I’d lost my community— the locker room. And without that, I didn’t feel I had a reason to get out of bed. I floundered. I tried to recreate what I’d lost in all kinds of ways, but here’s the truth: when we go from Point A to Point B in life, transition requires transformation. We have to become something different than we were before. And that isn’t always fun, and it’s not always easy.

For me, the turning point came when I hit my own version of rock bottom—failed relationship number 277. That was my opportunity to go inward, to rip my chest open, to really examine what was driving my poor decision-making. That process slowly helped me start making my way back to the path I’m on now—or at least closer to it. It was the last thing I would have ever asked for, but it turned out to be the first thing that truly worked in getting me back to myself.

ALLIÉ: Wow. What a journey. And to your point, to be this in one instant—and then, in the very next, not at all—that’s a hard reconciliation. Your identity, your purpose—or the sudden lack thereof—had been something you’d never had to go looking for before. It was always there. You’d had a career most people would define as the pinnacle of success. But sometimes, the moments that define us don’t look like success at all. They look messy and scattered. They’re quieter, far more complicated. Could you talk for a moment, Aaron, about one of those moments—one of those invisible lows—you rose from?

AARON: Man, there are so many. But the easiest one that comes to mind is the moment I decided to give up drugs and alcohol. Looking back, I didn’t drink or use because of the way it made me feel—though that’s what I thought at the time. I drank and used because of the way it prevented me from feeling.

I come from a long line of alcoholics on my father’s side. Addiction runs in my family. We like what we like, and there’s no middle ground—no gray area. It’s all or nothing. In recovery, they say, “One is too many, and a thousand is never enough.” That was certainly true for me—not just with drugs and alcohol, but with food, bread, sugar, Netflix… anything. I like what I like.

I’d mentioned that failed relationship. In that mess, we tried the on-again-off-again thing, but it was more of an emotional hostage situation than a relationship—probably for both of us. She had cheated on me with her ex-fiancé, and I was the rebound guy. We were both in bad places. At one point, she said she thought she had a drinking problem, so I took her to a meeting at a church and dropped her off. The women there came out, hugged her, and took her in. I remember thinking, Yeah, good cover story.

About a week later, she called and said, “Hey, just wanted to thank you for taking me to the meeting. I’m an alcoholic, and I’m going to try recovery. I’m doing this for me. And… I’ll be honest—this will probably be the last time we speak. But there’s one more thing I want you to know.”

I said, “Yeah? What’s that?”

She said, “You and I drink and use the same.”

Allié, the deafening silence that followed those words changed the course of my life forever. I heard her. And in that instant, every piece of my life—the doubts, the questions, the masks, the charade, the pretending, the desperate hope that no one would find me out, the imposter syndrome, the constant management of my image—just fell away. That sentence stuck with me. It rang in my ears.

The next day, I went to the gym and sat on a treadmill talking to a mutual friend. I told her about the conversation, and she said, “You know, my husband used to go to a recovery meeting up on the hill in our neighborhood. If you’re interested, I can give you his number.”

Now, my first thought was, Go talk to strangers? I just won a Super Bowl. I’m on TV right now. I’m an NFL guy—I’m not walking into a meeting full of people who live under park benches drinking out of paper bags. But for whatever reason, I said, “Okay.”

That was Monday. I called him Tuesday. He invited me to his garage—heaven, as it turned out. That garage became the place where I learned how to be human again. It’s where I dropped the facade, learned how to be Aaron again, and became a good teammate again—to myself, to my community, to my friends, to my employers. It’s where I let go of the lie, got honest, became willing, made amends, and started cleaning up the wreckage of my life. Some moments, some phone calls, matter more than others. Looking back, that one quiet moment didn’t look like much from the outside. But everything that came after it changed everything.

I’m grateful for all the pain I had to go through to earn the opportunity to walk into that garage. I’m grateful for those guys who laughed at me—but laughed with me—when I introduced myself by saying, “Yeah, my name’s Aaron, and I don’t think I have a drinking problem, but I’m here to explore it.” And they said, “Yeah, man, that’s new. Sit down.” It was that kind of, Sit down, rook. We got this. We’re the vets in this room. You’ve got two ears and one mouth. Shut your mouth, and use your ears. And keep coming back.

And I did. I owe everything I have in my life today to that. I’ve got a life I wouldn’t trade anything for. If you gave me a magic wand and told me I could change my job, my house, where I live, my kids, my looks—anything—I wouldn’t change a thing. Because everything I have is a gift. It’s all a blessing. My wife and kids might not always say that’s true, but in my heart of hearts, that’s how I feel. That moment was a turning point I will never forget.

“The truth is, we don’t see the world the way it is. We see it the way we are.”

ALLIÉ: I think it’s really beautiful to say that such a degree of grace can be found in a garage. You know, Aaron, you and I have come from different worlds, and yet they’re the same in one regard: strength. Strength that was all about grit, about wins, about pushing through at all costs. Perhaps you’re like I am—the older I get, the more I’ve realized that kind of strength can’t carry you forever. So, my question for you now is this: what does strength look like for you today? Not the NFL version, but the kind that gets you through an ordinary Friday. What is strength to you now?

AARON: Give me a second… I’m gonna find this quote someone sent me because it’s so dang good and it sums up exactly what I’m about to say: “The problem is not that there are problems. The problem is expecting otherwise and thinking that having problems is a problem.” —Theodore Rubin.

The Buddhists like to say that pain is inevitable, but suffering is optional. And for me, the suffering in my life comes when I’m unwilling to accept things as they are—when I want them to be different. When I want my wife to act a certain way. When I expect my kids to follow every instruction perfectly. When the reds, the blues, the purples— whoever it is in the world—don’t line up with my preferences, that’s when I’m the most anxious. That’s when I suffer. When I’m able to let things go and let the world be what it is, I’m good.

Being a college football analyst for CBS Sports is a long season—it’s a grind. But I’m wired for that. I like it hot and intense, like a meteor—boom! But I also need a carrot at the end of the stick. For many years, that carrot was heading down to Baja. I love the area north of Cabo—it’s remote, quiet.

One morning, I was on the beach meditating. The sun was rising behind me over the Sierra Lagunas, painting the sky pink and orange. Out front, the ocean was alive—whales spouting so close it felt like you could walk across their backs. It was idyllic, serene.

And then—out of nowhere—I see this one guy walking along the beach with about ten dogs. Turns out he rescues them, which is a big deal in Baja where spaying and neutering aren’t common. But these dogs? They were unruly. Barking like crazy. And here I am, all Zen, and this dude is wrecking my serenity.

So I’m sitting there, watching him, thinking all kinds of thoughts… and I start getting tight. Irritated. Two or three minutes into this, I catch myself and think, Oh my God. This is what I do. I’m literally surrounded by beauty and peace, and I’m zooming in on this tiny speck of negativity. That realization hit me like a brick: I don’t see the world the way it is—I see it the way I am.

Both things were true in that moment—serenity, sunrise, whales, meditation… and a man rescuing dogs. But the world I chose to live in for those few minutes was the negative one—focused on the interruption instead of the blessing. I wasn’t present.

So now, whenever I get too full of myself—caught up in politics, what’s happening in the world, my neighbors, the this and the that—I try to remember that story. I ask myself, How can I shift my focus? What else is true right now?

When my wife wants something from me but doesn’t verbalize it—God bless her soul—and I’m feeling frustrated, I try to pause and remember all the things I love about her. And in that moment, those little pet peeves that come with a 16-year marriage just don’t carry the same weight they used to.

The truth is, we don’t see the world the way it is. We see it the way we are. That’s why it’s critical to be intentional about where we place our focus and attention—and therefore our time and effort. Because when we control where our focus, attention, time, and effort go, we give ourselves the power to change our fate.

ALLIÉ: I love that—and I love how you just said, What else is true about this moment? What else is true about my wife? What else is true here in the serenity on the beach? Because there were so many other things that were true— not just the dogs. That’s powerful. I feel like we’re already talking about some deep stuff, but I want to go even deeper.

ALLIÉ: (continued) Let’s talk about something like anger. And now, this is me as a woman saying this, but I feel like— society in general—a lot of men use anger as a socially acceptable mask for everything: sadness, fear, vulnerability. Has that ever been true for you?

AARON: Has it ever not been true for me? I think the truest part about that is the awakening to that dynamic. For me, when I’m afraid… when I’m scared… when I feel uncertainty… when I’m sad—I don’t like those feelings. They make me feel vulnerable. And I’ve been hurt in my life when I’ve felt vulnerable. You know when I don’t feel vulnerable? When I’m big. Mad. Angry. The big guy.

I think a lot of men either watch, learn, or just figure out that anger is a safety valve—a mechanism. I, like many people, absolutely default to anger. The first thing I actually feel might be fear or sadness, but the first thing I show is anger. Because when I’m angry, I feel strong and powerful. I’ve got the ax in my hands and I’m ready to swing. When I’m afraid, I feel weak—and who wants to feel that way?

It’s a process. Especially knowing how our brains work when we’re in a fear state—when cortisol or adrenaline kicks in and fight-or-flight takes over. Those chemicals take 15 to 20 minutes to process. And if we reinforce them with more negative thoughts, we can turn a molehill into a mountain in no time.

Take road rage, for example. Somebody cuts me off in traffic—this is what I do: I start playing it out in my head. What if I got out of the car at the next light and said this, and then he said that… And before I know it, I’m six miles down the road, having a full-blown argument in my head about something that’s never going to happen.

But here’s the truth: that driver cutting me off isn’t just about traffic. It’s about the times in my life when I’ve felt disrespected in ways that were much deeper and much darker. When I was sexually abused. When I was physically violated. When I was abandoned. I hated how that felt.

So, no—this guy in traffic isn’t putting his hands down my pants. But my brain, this giant association machine, recognizes that feeling and says, We know this feeling. We don’t like it. We need to protect you from it. That’s what being “triggered” is—something small that reminds us of a bigger danger our brain never forgot. It’s survival instinct. We don’t want the saber-toothed tiger jumping out of the bushes, so when we hear bushes rustling, we run. The trick is having a plan to respond to our triggers instead of just reacting to them.

I’m as guilty as anyone of using anger to mask my true emotions. And I’ll take it one step further, Allié—I’m the lovable big guy. I don’t want to come across like a jerk, so instead of being openly angry, I go passive-aggressive. I get sarcastic. I’ll slice you up with words and make it seem like I’m joking, but underneath there’s anger. For me, sarcasm is a warning sign. It’s been my default style of humor for years. I’m really working to correct that—to find more creative ways to be funny that don’t cut people down. Because for me, sarcasm has always been a double-edged sword. And truth be told, I’ve used it to cut a lot more than I’ve ever used it to bless.

ALLIÉ: I love that—just becoming so self-aware. For you, recognizing For me, sarcasm is this. For me, this is. And then creating from that set of knowings so we can take the appropriate action. I also love how you talked about the difference between responding and reacting. A reaction and a response are two very different things—one’s a kneejerk reflex, the other has intention behind it.

So, I’ve heard it through the grapevine that you’ve got a name for that voice inside your head—by the name of Ernie. Mine, I’ll share, is the editor… and she’s a real piece of work. So my question for you now, switching gears a bit: what do you do when Ernie is loud and relentless? What brings you back to center, Aaron?

AARON: First of all, I want to give a shout-out to Ernie. He’s got a bad rap. Granted, he’s always trying to f*ck sh*t up. He’s always trying to ruin a good thing. He never appreciates how good he’s got it. He also doesn’t have a lot of confidence, so he’s always trying to stand out and call attention to himself, just so you’ll tell him he’s a good boy… that he matters… that he’s seen. He means well, but, man—oh, man—it’s best if he stays in his room. I try to keep Ernie in his cage as much as I can because he likes to muck things up a little bit.

Ernie is my alter ego—my shadow piece. It’s the part of me I try to hide, repress, and deny… but it’s back there, pulling levers. What I’ve realized over the years is that he’s also persistent, energetic, and outgoing. There are some positive qualities to my ego—to my shadow. When I’m at my best, I try to draw on Ernie and that part of me I’ve worked so hard to stuff down.

AARON: (continued) Because whatever we repress continues to evolve and pop up. As the saying goes—whatever we resist, persists. I think I first heard that from Neale Donald Walsch in Conversations with God. When we hide, repress, or deny those shadow parts, they still find their way out. So now I’m trying to keep Ernie out in front of me— let him work for me instead of against me. And look—this may sound crazy to some people listening. I’m not saying I hear voices or talk to Ernie—it’s a metaphor. A way to describe those different parts of ourselves and the masks we wear to stay safe and navigate the world.

Here’s the thing—we all talk about “the hole” in ourselves, always looking for something to fill it so we can become whole. What I’m finding, in my current trajectory, is that what’s been missing… is me. All of me—including Ernie. This part of me that developed as a safety mechanism, as a way to navigate a challenging childhood. But just as much a part of me as Ernie is the benign, benevolent version—the one people write articles about. Ernie and Aaron are the same cat. And I think part of this journey for all of us is learning to integrate those pieces to be okay with everything we are and everything we’re not. Our wholeness is what makes us integral. That’s integrity—our thoughts, our words, our actions—all in alignment, even with the parts of us we might not want friends, neighbors, or loved ones to see.

ALLIÉ: There’s a specific word you used there—integral. Because when we think of integrity, we do need to integrate the verb of it, not just sit with the noun of it. We have to bring together these different parts and pieces of ourselves to form the whole version of who we are.

AARON: So what’s the flip side? I’m curious now—I’m going to flip this. Now we’re doing this podcast together. What’s the flip side of your editor? Is it discernment? Is it the ability to parse through information and pull out what’s helpful? What’s the positive side of the negative piece of your editor?

ALLIÉ: Yeah… I guess the editor always wants to make sure everything is done to a certain degree of excellence— and won’t have it any other way. So I have to remind her that I’m human. Allié is human. And that’s okay with me. I’ve got to convince her that it’s okay with her, too. So yeah, she can be a bitch, but most of the time we get along. And to your point—recognizing that I need her to do the work I do. But at the same time, I’ve got to remind her it’s okay not to be perfect… Because there’s no such thing.

AARON: Thank you for that.

ALLIÉ: Well, yeah—Ernie and the editor. I tell you what, we need them. We need to love them.

AARON: Yeah… they’re probably going to hook up for drinks after this.

ALLIÉ: Of course they would. Let’s talk now about showing up. Aaron, you’re showing up in very powerful ways—not just for yourself, but for so many others. A couple of examples come to mind: through Radical Hope, you’re helping young people find connection and support around mental health. And with the Joe Moore Award, you’re honoring the kind of grit and unity that doesn’t always get accolades or make headlines. So my next question is, what connects these two parts of your work? What do they say about the legacy you’re building off the field?

AARON: I think, at my core, if there’s one thing unquestionable about me, it’s my resilience. I don’t know what I did to earn it, to have it—or maybe I’m just temporarily holding it—but it’s there, and it’s always been there. Throughout my life, I’ve had people who reminded me of that, who nurtured it, who fed it when it was hungry.

I’ve lost 13 people I loved to suicide. I’ve lost a couple dozen more to deaths of despair—both from my football circles and from recovery. I don’t know why they didn’t have that same resilience. I’m just grateful that I do. And my life hasn’t been easy—not for me, not for any of us. Part of me suspects that’s the point.

Why we’re here is to be born perfect, then encounter things that make us question that perfection. We spend our whole lives trying to work our way back—only to realize we were perfect all along. Whether we accept that or not, that’s the journey. There’s divinity in that for me.

Hope is a verb. It requires action. I’ve found ways to take action—sometimes just by telling my story, leading with vulnerability. That’s a superpower of mine. It’s like, I’ll show you mine if you show me yours—but in healthy, loving ways. So whether it’s the Joe Moore Award, Radical Hope, this podcast, or any other work I do—I just want to be a good teammate and be a meaningful part of something worthwhile. Everything I’ve ever done—my family, my sports career, my time with you right here—fits into that. When I can do that, all the other noise just falls away.

“I think about that moment—the fear, the uncertainty—and how close I was to walking away from everything that came after.”

AARON: (continued) As hard and raw as this part of me is, it’s the best part of me. It’s the most authentic part of me. But it’s not easy to get on CBS and talk college football like this. I’m grateful, though, that I can talk college football— because that gives me the platform, the visibility, and the time to talk about things that matter more, that men are more than a third-and-seven.

Hope. Resilience. Being a good teammate… I’ve had mentors who changed my life forever. Joe Moore, my offensive line coach, taught me that I always had five more in me—that no matter how hard things got, I could always do five more reps. Bill Z, my longtime mentor, gave me a roadmap for happiness and serenity—how to forgive myself and others, how to lead, how to be grateful, how to be humble in the most glorious, grandiose sense.

My high school head coach, Bob Ladouceur, taught me to believe in myself and my potential. My mom—on my first day of football practice at De La Salle—gave me one of the most important lessons of my life. We had just moved. I was a D and F student. I’d been kicked out of the house. I wasn’t on my way to being a college football Hall of Famer or Super Bowl champ—not even a high school graduate.

That first practice? I got my ass chewed out. I was going the wrong way. I didn’t know what I was doing. I’d never really played organized football. I came home in tears and told my mom, “I’m sorry. I know we moved here for this, but I can’t do it. I can’t go back.”

Leading up to that, she had asked me what I wanted to do with my life. I’d said, “I don’t know… play pro football,” but I didn’t really believe it. That day, she looked at me and said, “You’ve got to figure out if what you want is worth the price you might have to pay for it. If the answer is yes, you have to find a way to get up and go to practice. If the answer is no, that’s okay—but you have to be honest with yourself.” Then she shut the door.

I wish you could have seen me sitting there on the edge of that bed, Allié. I didn’t know how I was going to go back… but I did. And I got my ass chewed again. But I made a block or two. I went back the next day, made another couple blocks. I kept going. And it turned out—I was pretty damn good at football. I just didn’t know it yet.

I think about that moment—the fear, the uncertainty—and how close I was to walking away from everything that came after. I had no idea what was possible, what I was capable of, the people I’d meet, the experiences I’d have, the money I’d make, the lives I’d touch, the people who’d touch mine. None of it. But I had hope. And I want other people to have that, too.

I want the world to know there are things each of us can do—in as little as five minutes—that can help us feel better and perform better in the moments that matter most. They don’t cost a thing. They just require willingness, honesty, and a little elbow grease. And my observation? When I’ve done that—and when others have, too—somehow, some way, things get better. And I ask you, Allié… how does it get better than that?

ALLIÉ: That’s a big word. It’s one of my favorites with just four letters—hope. Because sometimes you feel like you have nothing… but at the end of the day, you can always have hope. No one can take that away.

AARON: I’ll say this about hope—optimism is the belief that somehow things will get better. Hope is the belief that there are things we can do to make things better. There’s a big difference. Optimism is about desire—it relies on things happening outside our control. Hope? Hope’s a verb. It’s about action. It’s believing there are steps we can take to make our lives better—and that puts the ball back in our court. That’s true for everybody.

ALLIÉ: One hundred percent. Because we do always have the opportunity to remake, to course-correct. As long as we’re alive—if there’s still a chance, there’s still hope. And I want to shift one more time…

AARON: Oh, here we go. You want to go darker than this? Damn, Allié.

ALLIÉ: Okay, let’s go to the other side of it. Recently you were featured in a very powerful episode of Remade with Koby Stevens and Villa Licci. I want to talk that and specifically, what does the word remade mean to you?

AARON: That was a cool moment—the whole day, really—and how I got connected with Bill McCullough, the producer. He knows a good buddy of mine, Lonnie Paxton. Lonnie’s got his fingers in all kinds of things. We both played in the NFL—not together—but we know a lot of the same people, we’ve worked out together. It was just this beautiful confluence of all these circles of my life—football, recovery, transformation—coming together. What remade brought up for me immediately is the idea that the power of shared experience is transformational. That moment for me was being able to share—completely different sets of circumstances, sure—but a shared human experience. No different than me and your “editor” and my “Ernie.” Your lived experience and mine may seem worlds apart—you’re female, I’m male, you’re small, I’m big, different races, different genetics, different paths. But is it really different?

To me, being remade is like when a vase breaks and is repaired with gold lines—an art form from the East. The vase is damaged, but the gold creates something new with its own unique beauty. It’s not what it was before, but it’s equally beautiful—just in a different way. Being remade is the Humpty Dumpty of humanity. We fall off the wall, shatter into pieces, and if we’re lucky, we have people around us—and the courage within ourselves—to find the gold in our lives, piece it back together, and keep moving forward.

ALLIÉ: I love that. I love it so much. Just a couple more questions—on the lighter side. If every single thing you ever did on the field disappeared, and the only thing left was how you showed up as a father, a friend, a man—what would you want people to remember about you?

AARON: That’s a really good question. And honestly, I try to live my life with that in mind. I’ve always said—when I die, if the thing I’m best known for is how I played football, then I’ve been a colossal failure.

One of my mentors, Bill Z—who I mentioned earlier—helped me understand that football is part of who I am, but not the biggest part. It’s a launch pad, a piece of the puzzle. He told me that in my fifties, everything would start to come together—just like it did for him—and that’s when I’d be able to affect the most change. Here I am at 52, finding that to be true.

My wife, my kids, my friends—they’d probably say, “At times he was difficult… but he was always worth it in the end.” And if I make it to the pearly gates—assuming God doesn’t bring up spring break in ‘92—I think He might say I was a pretty good teammate. Someone you’d want on your team. Maybe not the most talented, but someone who helped you win, helped you get more of what you wanted, and made the journey better. I hope people would remember that we laughed a lot, cried a lot, and grew together. I try to bring that into everything I do.

Right now, I’ve got four months of the year where I get to laugh, have fun, and get paid to be on scholarship talking sports on television—and my opinions don’t even have to be right. Then I’ve got the other eight months, which fund my philanthropic habit—where I get to be purposeful, feel significant, be part of a community, and do something bigger than myself.

However we each do it, I believe having income, identity, purpose, significance, and community—those are the five pillars of fulfillment. They’re a foundation for an amazing life. None of those things have anything to do with football, but all five were there when I was playing—just a little more muted than I’d have liked. Good thing I’ve been an exathlete a hell of a lot longer than I played because I’m getting the opportunity to try to flip the script there.

ALLIÉ: That is awesome. Before we wrap up today, one more thing, Aaron. Not everyone who feels lost looks lost. Sometimes you can be surrounded by love, by success—and still feel like you’re not at home in your own skin. So my last question for you today is for someone sitting in that space right now—what would you say to them? And again, not as a former pro athlete, but as someone who’s been there and made it through—what would you say?

AARON: I love the way you framed that question—that not all people who are lost look lost. My response would be this: feelings aren’t facts. The way we feel about our circumstances, our lives, or the people around us isn’t necessarily the way they actually are. That’s really important for me to remember when life is sending eight-man blitzes and I’ve only got five people to pick them up. Feelings aren’t facts.

Here’s what’s true—our thoughts are electrical signals running through complex neural pathways in our brains. Based on the type of thought we have, our brain releases chemicals. If we have good, healthy, positive thoughts, our brain releases positive chemicals, and we feel good. If we have negative, fearful, or uncertain thoughts, our brain releases chemicals accordingly—and then we start to feel afraid.

Exclusive Interview with Aaron Taylor https://awarenow.us/podcast/where-grit-meets-growth

AARON: Our bodies translate those chemicals, and shortly after, that’s what we experience as emotion. Just because I think the guy cutting me off in traffic is disrespecting me doesn’t necessarily mean that’s the case. So the real question becomes: when we feel lost, how do we lash ourselves to the mast when the seas get rough? For me, there are many ways—but prayer, meditation, and service are my anchors.

When I’m at my worst, I’m usually focused outward on what everyone else is doing—but only in terms of how it affects me. That’s self-centeredness. So when I feel lost or unloved—even if I’m surrounded by love—one of the most effective ways I’ve found to flip the script is through simple acts of service.

For me, courtesy is the gateway to serenity. That can be as small as letting a car merge in front of me, giving up a parking spot, holding the door open for someone who’s way too far away, or telling them not to rush. Complimenting a stranger’s tie or pocket square. These little things get me outside of myself. And here’s what I’ve noticed—whenever I start to feel better, I can usually look back and pinpoint the moment it began: the moment I made the decision to take action, to be of service. Because in those moments, I’m reminded that I have value. That regardless of how I feel about myself or whatever messages the world has sent me, I do have something to offer.

I think, deep down, that’s what all of us are trying to figure out—on this big rock in the middle of nowhere—whether our lives have meaning, whether we matter, whether we make a difference. So if you’re out there feeling lost—if you’re losing hope but want to be reminded there are good things and good people out there—turn your focus outward. Think about what you can bring to a situation rather than what you can get from it. Practice kindness, acceptance, and courtesy. See if that starts to shift your perspective—just slightly—so that your attention is on how you do matter, how you do make a difference, how people are appreciative and grateful for exactly who you are. That’s integrity. That’s becoming the integral person you’ve always been, even if you’ve forgotten it for a while.

Courtesy is the gateway to serenity. So if you’re struggling, look outside yourself. Find someone to help—and in doing so, you’ll be reminded of who the hell you’ve been all along. ∎

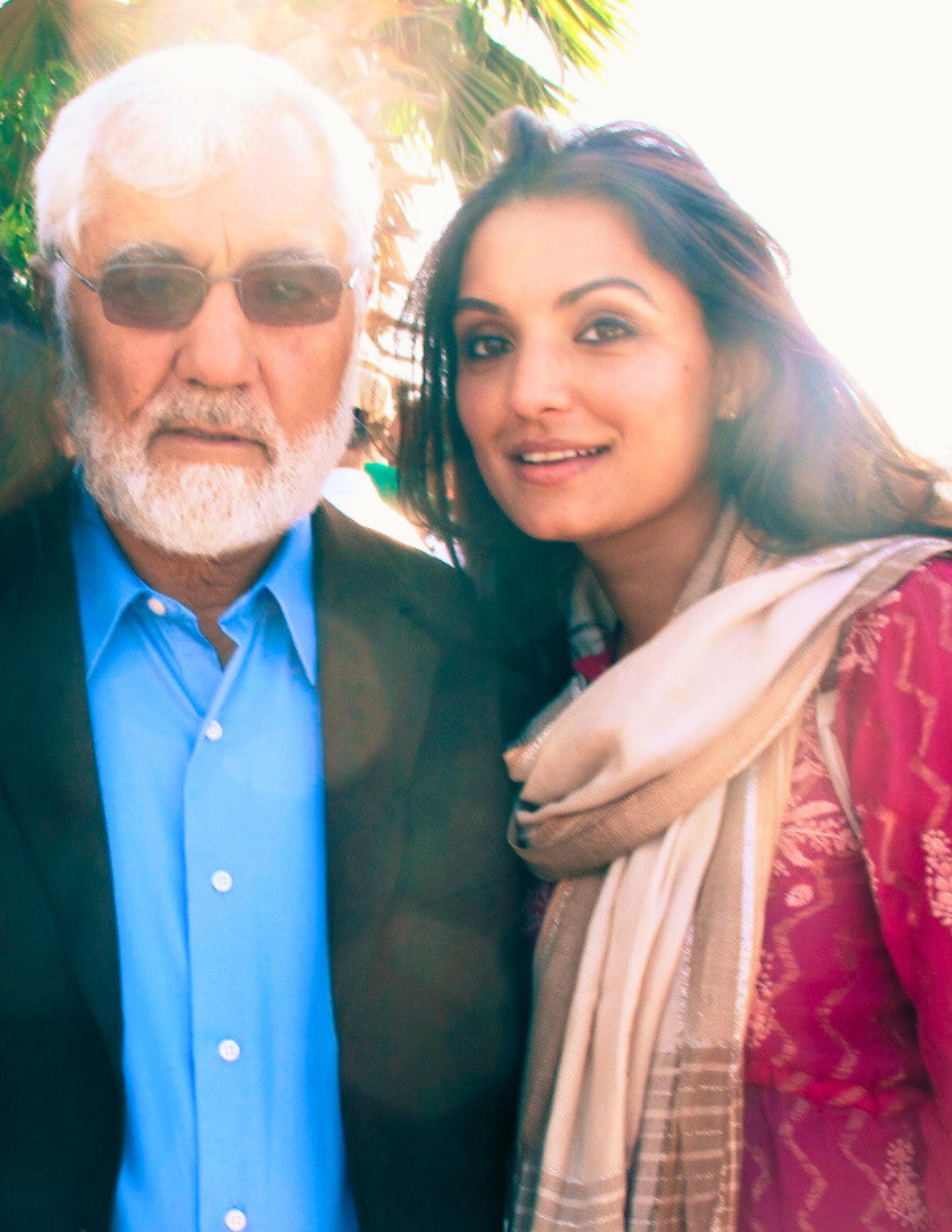

DR. LEEDA RASHID ALAMEDA HEALTH SYSTEM HOSPITALIST

BY DR. LEEDA RASHID

On July 22, 2025, the San Francisco County Board of Supervisors introduced a resolution officially recognizing Afghan American Heritage Month. The San Francisco Bay Area has been home to me since my family arrived here as refugees in 1986. I took my first walk along the ocean at China Beach. I ate my first hot dog here. I fell in love with San Francisco.

I grew up just across the Bay in Alameda, less famous than its neighboring city, but just as formative. Alameda, along with the cities of Santa Clara, Sacramento, San Diego, Los Angeles, and others, has also adopted or is planning to adopt similar resolutions to honor the Afghan men and women who have made California their home.

What I know about my Afghan-American community is this: most of us came to the U.S. as refugees, many fleeing the Soviet-Afghan war of the '80s, the civil war of the '90s, or more recently, the Taliban’s return to power. We weren’t just escaping war, we were fleeing persecution, instability, and the erasure of our futures. Building a life here hasn’t been easy. It’s taken immense effort, moments of deep loneliness, and the quiet, often invisible work of becoming “Afghan-American.”

It's an interesting journey to have a hyphenated identity, but aren't we all split in some form or another? Navigating the playground of identity, who we were, who we are, and who we wish to be isn't a story of this community alone. It's indeed the American journey. It's the single mom with an aspiring singing career. It's the young cashier with his PhD on the horizon. It's the entrepreneur caregiving for a sick parent at home. It's all of us, finding ourselves in the greatest democratic experiment in the history of mankind and doing the work to keep its delicate balance. America is not a monolith, and when we forget this truth, we chip away at the very essence of what it means to be a democracy; a nation strengthened, not divided, by its many ‘Hyphen-American’ identities.

I urge you to visit an Afghan restaurant if you ever get the chance. Say hello to the owner or the server. You’ll meet some of the kindest, most hard-working, hospitable, and genuinely funny people you’ve ever encountered and you’ll eat the best rice and kabob on the planet. Coupling the survival instinct with the opportunity, you will see that besides serving great Kabob many Afghans you meet have moved on to become lawyers, engineers, doctors, policy makers, teachers, and good neighbors. We are known for this resilience internationally, and we have shaped the California around us with it.

Over the years, I’ve left California for school, for work, for love, even just to get away. And yet, I’ve always come back. Despite its frustrations, its imperfections and maybe because of them, it’s still home. Seeing this acknowledgment hit me harder than I would have expected, especially since I’m not sure I would’ve said I needed it if someone had asked. But it turns out I did. There’s something profoundly moving about feeling seen, truly seen, in the place you’ve called home. I think that’s something we can all understand. Today, as I reflect on what this recognition means to me, I’m reminded of why I keep returning: because California, in all its complexity, still makes space for stories like mine… that’s something to celebrate.

In a political climate where we’re too often pulled into fear-driven identity politics; where we’re told to see our neighbors as threats and “the other” as the problem, it feels especially powerful, even courageous, for these counties to take this step. It’s as if someone is quietly saying aloud what many of us already know to be true: that America’s strength lies in its diversity, in the beautiful, complicated tapestry of its immigrant stories.

In 1986, my father, a professor of law, a judge, and a political refugee with everything at stake had to choose between resettling in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Australia, or the United States. He didn’t hesitate. With his wife and four children, he boarded a plane to America with no debate and no doubt. He believed in this country then, and I still believe in it now. ∎

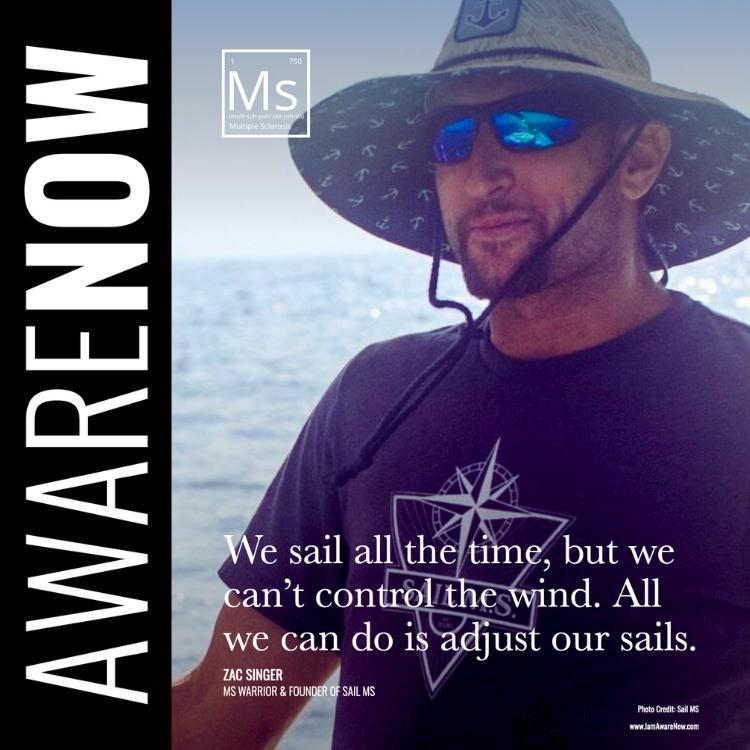

We sail all the time, but we can’t control the wind. All we can do is adjust our sails.

ZAC SINGER MS WARRIOR & FOUNDER OF SAIL MS

Captain Zachary "Zac" Singer is the founder of Sail MS, a nonprofit born from his own journey with multiple sclerosis. A licensed tugboat captain with a life spent at sea, Zac transformed his diagnosis into a mission—using the power of sailing to offer freedom, connection, and healing to others with MS. Through Sail MS, he merges maritime skill with deep purpose, helping others navigate their own uncharted waters.

ALLIÉ: Zac, you've spent your life on the water commanding tugboats and navigating the unknown. After your MS diagnosis, how did the ocean become more than just your workplace? How did it become your medicine?

ZAC: Well, it really comes down to me not fully realizing how much being a sailor was a part of me. It was kind of just my world. Once I took a break from that and didn’t know if I’d ever be able to do it again, I realized it was truly part of my identity. I was in an existential crisis of sorts: Who am I? What am I doing? Where am I going? On top of that were the fears of having MS and possibly being disabled in the future—really uncharted waters. I think that’s something most people with MS go through. If you’ve worked within a team-oriented environment, like the military, there’s an added level of existential threat because you lose part of your identity along with your occupation. Over half the people diagnosed with MS stop working within five years. Whether that’s psychological or physical, I know at least in the beginning—and throughout living with MS—that the psychological aspect is the biggest battle to undertake for all of us.

ALLIÉ: Oh, agreed one hundred percent. Let’s talk about the beginnings. Starting Sail MS wasn’t just a professional pivot. It was deeply personal as someone living with MS. What was the moment you knew you had to do this—not just for yourself, but for others?

ZAC: I actually knew the minute I was diagnosed. At that exact moment, I already knew I was going to do this. I don’t know how, I don’t know why, but I had carried this idea in my head for a long time—doing something like this with different groups of people. When the MS diagnosis came, everything clicked. The puzzle pieces came together. Now, after running Sail MS for nearly five years, I know there’s real magic in it. It doesn’t even have to be sailing specifically. It has to do with bringing together a purpose-driven group, all living with a common and difficult threat. It creates a bond that’s just magical from the very beginning. People are allowed to be vulnerable with each other, and then you’re locked into a boat for seven days—about 300 square feet of living space for seven or eight people. You get to know each other very well, very quickly, and more often than not, you leave bonded in a truly special way.

ALLIÉ: Speaking of those bonds, you became close with Cisco, who joins us. Cisco, I want to hear your story. How did your experience with Sail MS create a pivot, a change, a shift in how you dealt with your own life and diagnosis?

CISCO: First off, I had no experience sailing. I never wanted to go into the ocean. I barely knew how to swim. When I connected with Zac four years ago, it forced me to face fears and obstacles at every step. It made me realize I’m capable of doing pretty much whatever I want. That’s why I’m sitting here on a balcony in Greece right now. It made me look inward to discover who I am, what I’m capable of, and strengths I didn’t know I had.

“We talked about the illusion of immortality. MS lifts that veil.”

ALLIÉ: Like you said, it helped you look inward. Not to be too punny, but the sea helped you see what was within you. And Zac, you said it’s not only about a common diagnosis, but also a common threat. That parallel is so powerful: Cisco, you had never sailed before—just like you’d never lived with MS until the diagnosis. With both, you had to figure it out.

There’s something symbolic about sailing—charting a course, adjusting to the wind, facing storms. I’d like to hear from both of you on this. Zac, if you’ll go first: how does the act of sailing reflect what it’s like to live with MS?

ZAC: It really is the best metaphor. We sail all the time, but we can’t control the wind. All we can do is adjust our sails. That drives home the fact that none of us can control what’s happening. We might think we have control, but it’s an illusion. When I was diagnosed, I went to a psychologist for six months to wrap my head around it. We talked about the illusion of immortality. MS lifts that veil. You realize, Wow, anything can happen. That’s true for everyone, but most people live under the illusion that life is predictable.

When you’re sailing, you never really know what the wind or weather will bring, or how you’ll get where you’re going. You have to flow with it. And then, on a sail trip, there’s structure: we wake up, tackle tasks together, sail four or five hours, anchor, and settle in. What’s special is the presence. On these trips, I might see someone glance at their phone for five minutes in an entire week. It’s so rare. People are really present with themselves and each other. That’s powerful, especially when living with a disease that brings so much fear and makes it hard to live in the present. That’s where the magic happens.

ALLIÉ: So it’s about the opportunity to be present with each other—that real, raw connection. Cisco, let’s come back to you. How did you see the symbolism between sailing and MS? And also—let’s be real—what made you decide to get on a boat when you couldn’t even swim?

CISCO: I’m either crazy or not very smart. The first time I met Zac, he said, “Just come down to the dock. No pressure. You don’t have to sail—just watch us leave.” It was only a ten-minute drive, so I went. Next thing I knew, I was on the boat—and loving it.

Soon I was taking my first sailing class. My instructor told me, “Be careful, Cisco. Once the ocean gets its hooks in you, it won’t let go.” He was right. When I don’t sail for a while, I don’t feel right. Even when my MS symptoms flare— tiredness, balance issues—I’d still go out because I didn’t want Zac out there alone with new people. By the end of the day, I’d be exhausted, like after a workout, but my symptoms would feel minimized.

Symbolically, there are so many parallels. As Zac said, being present is key. Out there, you’re just connected—with the people on the boat and with the ocean. There’s no motor noise, just water and wind. You feel a sense of serenity. And you know everyone is either teaching or learning, but you’re all there for each other.

ALLIÉ: I love that—everyone’s in the same boat, literally and figuratively. So, Cisco, how would you compare your relationship with MS before Sail MS versus now?

Exclusive Interview with Zac Singer https://awarenow.us/podcast/the-wind-within

CISCO: One of my recent realizations is that MS will always be with me, and I have to work with it. Like the wind, you can’t control it—you adjust. I think of it like packing MS in my suitcase when I travel. As long as I respect it, live as healthy as I can, and slow down when I overdo it, we’re good. Before Sail MS, I read an old journal entry from about a year earlier. I had written, Maybe this is as good as it gets. That shocked me. After I met Zac and started sailing, my life flipped 180 degrees. Now I’m in Greece. The first time I came was two years ago, alone. I was scared, but I went. Sometimes you just have to take that leap of faith.

ALLIÉ: That’s awesome. Zac, we’ve heard Cisco’s transformation. What transformations do you hope others experience when they step aboard Sail MS?

ZAC: This past season, I had two newly diagnosed participants. One was a 36-year-old British Army Ranger diagnosed just three months earlier. When you get that diagnosis, you decide: victim group or fighter group. Am I going to let this dictate my life? Or am I going to fight tooth and nail?

If you’ve lived with MS for five years or more and you choose to board Sail MS, you’re automatically a fighter. People in a victim role wouldn’t choose to fly across the world and live on a sailboat with strangers for a week. For newly diagnosed participants, though, they’re still figuring out who they are. My goal is to help them see themselves in that fighter role. They’re surrounded by people who’ve already chosen that path. It solidifies their identity as warriors.

We had a woman, Patty Jean, who calls her MS “Massive Strength.” She’s lived with it for 30 years and lost her husband two years ago. She had more or less given up. Two years ago, she came with us—hesitant at first—and told me afterward it was the best experience of her life. She’s since returned for two more trips, restarted her coaching work, and reignited her life. That’s what Sail MS is about: helping people transform victimhood into victory.

ALLIÉ: I love that. You’re not just navigating boats—you’re helping people navigate life with MS. So, Zac, a personal question: when the waters get rough in your own journey, what keeps you steady?

ZAC: Breathing, first and foremost. I’ve learned how to breathe since being diagnosed, and I’m still learning. That, and the community we’ve built. Knowing those people are there for me—it’s uplifting. This community keeps me steady. ∎

Learn more about Sail MS: https://sailms.org Find & follow on Instagram: @sailingms

Every one is a part of everyone.

Miles to go before we sleep…