evelyn_richter_carrera

evelyn.richter.c@gmail.com

evelyn_richter_carrera

evelyn.richter.c@gmail.com

todo aquel que esta involucrado en el mundo de las visuales ha visto grandes cambios respecto a la manera de crear, dar a conocer y, por supuesto, comercializar las creaciones en los últimos años. Pero ¿cuáles son los motivos?, ¿cuáles son los factores que han generado este cambio rápido, imparable y posiblemente sin retorno? Muchos hablan de causas como el auge de las redes sociales y crecimiento del comercio electrónico en la pandemia, mientras otros lo asocian a problemas económicos en el globo producto de las guerras, del crecimiento del mercado del arte asiático, en contraste del americano.

Luego de la pandemia, el mercado del arte, tal como lo conocíamos, sobrevivió con dificultades. Entre las ferias de arte, prácticamente todas redujeron sus formatos, permitiendo así el ingreso de nuevas galerías y propuestas. Las galerías, por su parte, se redujeron o simplemente dejaron de asistir a estos mega eventos del mundo comercial por el gran gasto que implican y por el poco retorno que lograban con esta inversión. Si lo pensamos, el valor del stand, el traslado de las obras, la estadía y alimentación, el personal de apoyo, la difusión, y muchos otros, generan gastos interminables para situarse en un espacio donde la venta puede ser inexistente, ¿qué está pasando entonces en el mundo mercantil del arte?

Las galerías están adoptando nuevos formatos. Varias ya tomaron la difícil decisión de cerrar sus espacios físicos para dedicarse a la venta directa con sus clientes, llevándolos a los talleres de los artistas, asociándose con otros galeristas para compartir espacios de exposición, o moviéndose al mundo en línea. Este cambio ha perjudicado a las grandes y emblemáticas ferias. Algunas galerías se han asociado entre sí para, de manera paralela, competir con las ferias a través de inversiones más acotadas, con mejores retornos o, simplemente, por la versatilidad que les permite este formato, en cuanto a fechas y lugares.

Sabido es que nos encontramos en un fuerte periodo de transición. El avance de las nuevas tecnologías y el impacto de las redes sociales ha cambiado la forma que teníamos de entender el comercio y podemos observarlo en todo nivel. Sin lugar a dudas, estos debates y cuestionamientos deberían ser parte de la temática y las discusiones que inunden las calles de Miami en la semana del arte este año para Art Basel, así como las de España en 2025 cuando se celebre la aclamada Art Madrid. Esperamos que los conversatorios de los expertos aborden estas nuevas problemáticas, para ver qué rumbo tomará el mercado del arte y cómo podemos apoyarnos en estos nuevos desafíos.

Parte de los cambios y de las transiciones del mundo se reflejan en las páginas de esta edición. Nos encontraremos con reflexiones sobre la guerra, como en la obra de José Manuel Ciria; la importancia de la naturaleza, en la obra de Ángela Copello; y las reflexiones sobre la historia de la humanidad, en los trabajos de Carlos Castro Arias, Rodolfo Oviedo y Mustapha Romli.

anyone who is involved in the visual art world has seen great changes in the way creations are made, disseminated and traded over the recent years. But what are the reasons? What are the factors that have made this quick, unstoppable and possibly irreversible change? Many speak of causes such as the surge of social media and the growth of e-commerce during the pandemic, while others relate it to financial issues around the world due to war and the development of the Asian art market over the American.

After the pandemic, the art market that we knew struggled to survive. Virtually all art fairs reduced their size, as new galleries and proposals entered the scene. In turn, galleries also downsized or simply stopped attending the mega events of the trade world due to the large cost involved and the low return on investment. If we think about it, the value of the stands, transportation of artworks, accommodation and food costs, support staff, marketing, and many others create endless expenses to participate in a space where sales can never come. What is happening to the world of art trade?

Galleries and taking on new formats. Many have made the hard decision to close their physical spaces to bet on direct sales to their clients, taking them to artist studios and partnering up with other galleries to share exhibition spaces, or even jumping to online sales. This change has affected great and iconic art fairs. Some galleries have partnered to compete with fairs through smaller investments, better returns, or just because of the versatility this format allows in terms of dates and locations.

It is evident we are undergoing a marked transition period. The advent of new technologies and the impact of social media has changed the way we understood trade; we can see this at every level. Without a question, these debates and questions should be part of the theme and discussions to hit the streets of Miami this year during the week Art Basel is on, as well as those of Spain in 2025 when the acclaimed Art Madrid takes place. We hope that expert panels address these new issues to see what path the art market will take, and how we can support each other through these new challenges.

Some of the changes and transitions that the world is experiencing are featured in the pages of this issue. You will find reflections on war in José Manuel Ciria’s work, the importance of nature in Ángela Copello’s, and the history of humanity in the works of Carlos Castro Arias, Rodolfo Oviedo and Mostapha Romli.

Miami Beach Convention Center

December 6 - 8, 2024

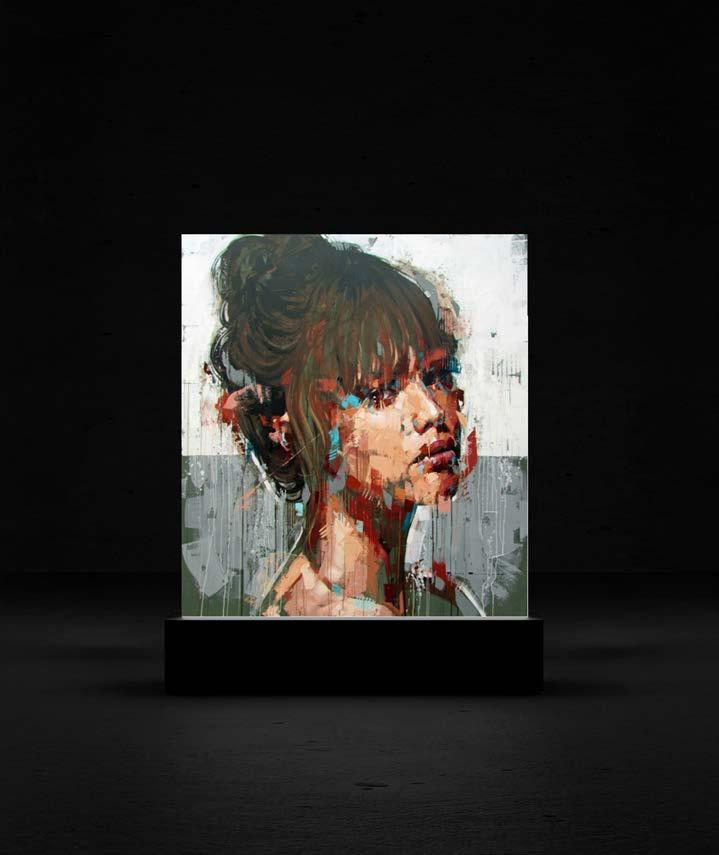

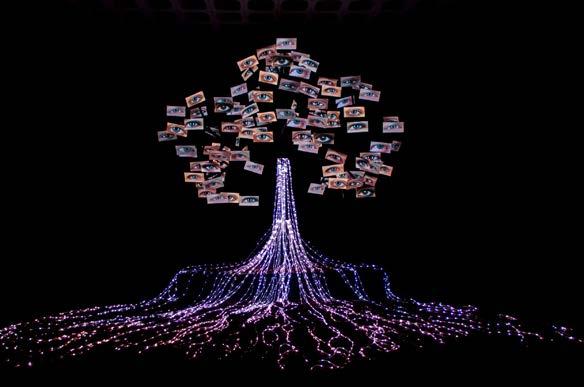

Luciano Colman (Argentina, 1968). En sus obras y desarrolla proyectos que combinan arte y tecnología para conectar con el público y transformar diversos espacios. Se ha especializado en la integración de luz, tecnología y sonido, aportando una perspectiva única a sus proyectos.

Su experiencia como DJ, músico y productor lumínico le ha permitido explorar nuevas formas de expresión artística, especialmente en la creación de puestas en escena para recitales, eventos y obras de teatro. Su trabajo se ha presentado en importantes muestras en Miami y Buenos Aires, incluyendo las ferias MAPA y Affair. Además, ha expuesto en destacados lugares dentro de Córdoba, su ciudad natal; y participa en la colección del Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Corrientes.

Su obra El Árbol de la Vida, es una experiencia audio visual de 4 metros y medio de altura por 4 metros de diámetro, incluye 120 pantallas LED, generadas a partir de una pantalla desarmada en mini-pantallas que representan las hojas del árbol, todo sincronizado para crear una experiencia visual única. Además, en la misma exhibición, presentó la instalación interactiva Talk to God.

djlucianocolman

lucianocolman@hotmail.com

DIRECTORES

Ana María Matthei

Ricardo Duch Marquez

DIRECTOR COMERCIAL

Cristóbal Duch Matthei

DIRECTORA DE ARTE Y EDITORIAL LIBROS

Catalina Papic

PROYECTOS CULTURALES

Camila Duch Matthei

EDITORA

Elisa Massardo

DISEÑO GRÁFICO

María Nestler

CORRECCIÓN DE TEXTOS

Javiera Fernández

ASESORES

Benjamín Duch Matthei

Ricardo Duch Matthei

Milagros Duch Matthei

Felipe Duch Matthei

REPRESENTANTES INTERNACIONALES

Julio Sapollnik (Argentina)

REPRESENTANTE LEGAL

Orlando Calderón

TRADUCCIÓN

Adriana Cruz

SUSCRIPCIONES

info@arteallimite.com

IMPRESIÓN

A Impresores

DIRECCIONES

Chile / Francisco Noguera 217 oficina 30, Providencia, Santiago de Chile. www.arteallimite.com

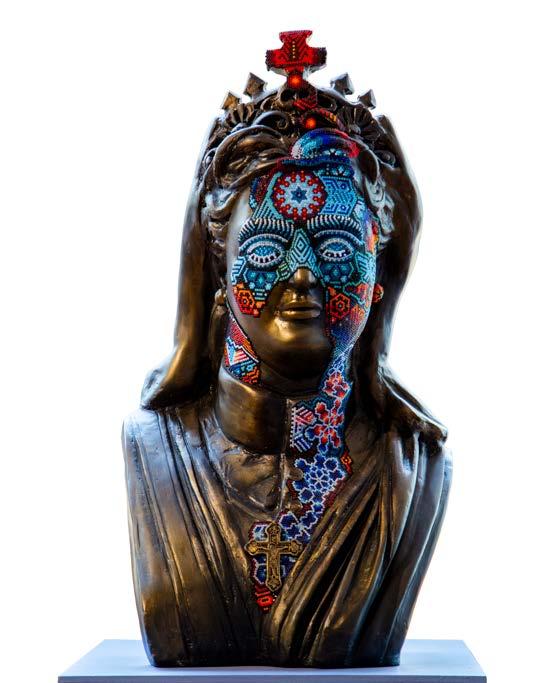

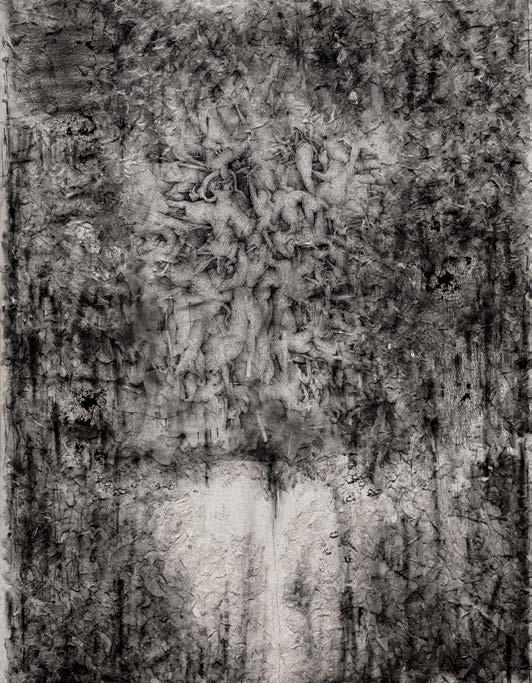

PORTADA

Ángela Copello.

VENTA PUBLICIDAD +56 9 99911933. info@arteallimite.com marketing@arteallimite.com

Derechos reservados

Publicaciones Arte Al Límite Ltda.

Por Elisa Massardo. Lic. en Historia y Estética (Chile) Imágenes cortesía de la artista. Argentina

Representada por Oda Arte.

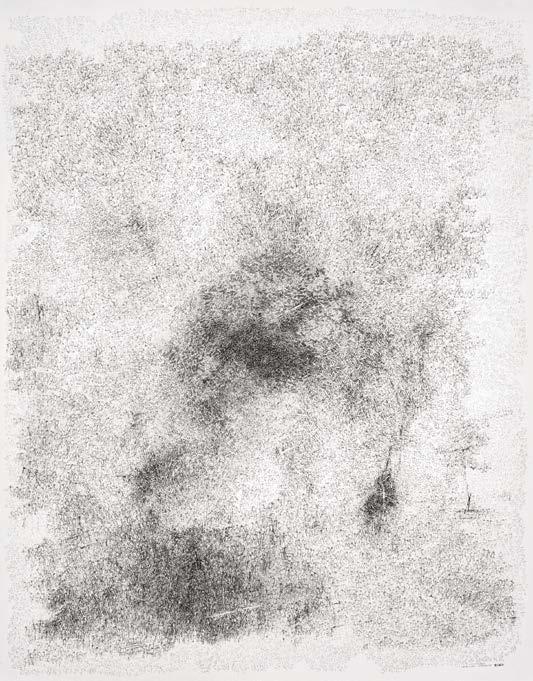

una vida ligada al paisaje y a la naturaleza llevaron a Ángela Copello a disfrutar del entorno sin intervenciones. Así, desde que comenzó a dedicarse a la fotografía, trabajó realizando imágenes para libros sobre el entorno natural, parques y jardines. “El contacto con la naturaleza me transmite la idea de vida y muerte en un círculo virtuoso”, explica la artista, quien ve estos ciclos con la holgura del renacer, del cuidado y de la espera.

Como fotógrafa, conoce bien los tiempos, las variables que se pueden controlar y aquellas espontáneas que surgen de cada toma. Para Ángela, la naturaleza es el origen de la vida y es consciente de lo positivo que es el contacto entre el ser humano y ese mundo que, en el romanticismo, se presentaba como un espacio enorme y amenazante, difícil de descubrir y de gobernar. Espacio que hoy, sin embargo, se ha dominado de manera brutal, eliminando muchas veces aquellos elementos positivos que trae implícito el contacto con “la sensación del viento, el olor de la tierra húmeda, o la visión de un mar inmenso”.

Desde ahí, Ángela Copello coincide con las nociones del posthumanismo que promueve “la idea de que los seres humanos son solo una de las muchas formas de existencia y que nuestras relaciones, con otros seres”, asumiendo que se debe respetar al resto de las especies. En sus fotografías, podemos observar cómo la naturaleza predomina y gobierna los espacios, independiente de las historias que puedan esconder estas hojas y plantas que protagonizan sus trabajos. Observamos un mundo donde la intervención humana pareciera desaparecer cada vez más, en una especie de mutación que invierte el sentido actual del mundo.

¿Cómo surge la necesidad de exponer a la naturaleza en primeros planos? La idea de fotografiar la naturaleza en primeros planos me permite descontextualizarla del paisaje, tratando de crear una conexión más profunda y consciente con el entorno. Intento crear una experiencia visual más íntima, resaltando la belleza intrínseca de elementos naturales. Un fragmento puede evocar sensaciones de misterio o introspección y, al aislar una sección del paisaje, este puede adquirir un simbolismo específico que en su contexto original puede perderse. Las imágenes en primer plano humanizan a los sujetos naturales, acercándolos a nuestra experiencia visual y emocional; los elementos individuales de la naturaleza adquieren mayor protagonismo.

alife surrounded by landscapes and nature led Ángela Copello to enjoy the unadulterated environment. Since she started working as a photographer, she has been creating images for books about the natural environment, parks and gardens. “Being in touch with nature communicates the idea of life and death in a virtuous circle to me,” the artist comments, explaining she understands these cycles in the phases of rebirth, care and waiting.

As a photographer, she knows these phases well, the variables that can be controlled, and the unknowns that spontaneously arise for each shot. For Ángela, nature is the origin of life, and she is aware of how positive the connection between humans and the natural environment can be. During the Romantic era, the environment was represented by vast and threatening spaces that were difficult to discover and rule. However, nowadays the environment has been brutally dominated, often undermining the positive elements that come with feeling “the touch of the wind, the smell of damp earth, or the sight of an endless sea.”

In light of this, Ángela Copello agrees with posthumanist notions that promote “the idea that human beings are just one of the many forms of existence” and that out “relationships with other beings” must be respectful of other species. In her photographs, nature prevails in the spaces and rules them, regardless of the stories that the plants and leaves that are prominently featured in her pieces might hide. We see a world where human intervention seems to disappear more and more, in a sort of mutation that reverses the current state of the planet.

How did the need to put nature in the foreground come about?

The idea to photograph nature in the foreground of my work allows me to decontextualize it from landscapes in an attempt to establish a deeper and more aware connection to the environment. I try to create a more intimate visual experience that highlights the inherent beauty of natural elements.

A fragment can evoke feelings of mystery or introspection and, by isolating a section of a landscape, it can acquire a specific symbolism that might have been missed in its original context. Foreground images humanize nature subjects, bringing them closer to our visual and emotional experience. Thus, individual elements of nature take on greater prominence.

Con los primeros planos, puedo transmitir una sensación más potente de textura, forma y color, que quizá se perdería dentro de un entorno más complejo. Además, este recurso me permite transformar un objeto natural en una pieza casi escultórica.

¿De qué manera consideras que el arte puede ayudar a generar consciencia sobre el cambio climático y por qué?

El arte tiene el potencial de ser una herramienta poderosa para movilizar y motivar a las personas respecto de la importancia de cuidar a nuestra tierra. Puede despertar conciencia y generar emoción para que el público sienta una mayor urgencia y responsabilidad en cuanto a esta necesidad.

El arte nos pone frente a una realidad que nos conmueve y nos interpela. Mi trabajo habla acerca de la supervivencia y sobre cómo la intromisión perjudicial del hombre en la naturaleza, junto a la desidia política, generan un enorme daño.

En la serie El poder del l í mite – Kudzu muestras la realidad dual de la naturaleza. La apropiación de una especie a través de otra; el mundo parasitario. ¿Cómo llegaste a esta investigación? Mi serie anterior, Edén, comenzó con la búsqueda de bolsones de flora nativa que permanecen vírgenes dentro de cultivos intensivos, cercanos a pueblos y ciudades. Mi idea no era mostrar ese diálogo, sino plasmar un universo donde querer quedarse, donde encontrar un origen, donde uno puede tener un diálogo con uno mismo y con algo superior. Fue buscando escenarios para esta serie que me crucé con el kudzu ( Pueraria lobata ), una enredadera perenne, originaria de Oriente, que se introdujo en los Estados Unidos en 1876 y fue promovida por el gobierno como una “planta maravillosa” para alimentar al ganado. Hoy cubre más de un millón de hectáreas. Cuando el Kudzu invade, cubre otras especies hasta ahogarlas. Es capaz de transformar paisajes enteros, es un ejemplo de la dualidad de la naturaleza. La belleza del Kudzu es, paradójicamente, su peor enemiga: representa un recordatorio vívido de la importancia de comprender y controlar las consecuencias del hombre en el ecosistema. Viajé al sudeste de Estados Unidos para fotografiar ese paisaje a la vez maravilloso y macabro.

With foregrounds, I can convey more powerful feeling for texture, shape and color, that might have been lost in a more complex environment. Additionally, this resource allows me to transform a natural object into an almost sculptural piece.

How do you consider that art can help raise awareness of climate change and why?

Art has the potential of being a powerful tool to mobilize and motivate people about the importance of taking care of our land. It can awaken awareness and stir emotions to make the public feel a greater sense of urgency and responsibility for this need.

Art confronts us with a reality that moves and challenges us. My work speaks on survival and how humans’ damaging intrusion into nature, as well as political apathy, causes great harm.

In the series El poder del límite – Kudzu (The Power of Limits – Kudzu), you show the dualistic reality of nature: the appropriation of one species through another; the parasitic world. How did you come to this topic?

My previous series, Edén ( Eden ), started with a quest for patches of native flora that remained undisturbed within intensive farming crops, close to towns and cities. My idea wasn’t to showcase that conversation, but to capture a universe where we would want to stay, find an origin, have a conversation with ourselves and with a higher power.

While looking for locations for this series, I found a kudzu (Pueraria lobata) , a perennial vine native to the East that was introduced in the US in 1876 and advertised by the government as a “wonderful plant” to feed livestock. Today, it covers over a million hectares.

When Kudzu invades, it covers other species until it drowns the out. It is capable of transforming entire landscapes; it is an example of the duality of nature. The beauty of Kudzu is that it is paradoxically its own worst enemy: it represents a vivid reminder of the importance of understanding and controlling the consequences of humans’ actions in the environment. I traveled to the south east of the US to shoot that landscape that is both marvelous and macabre.

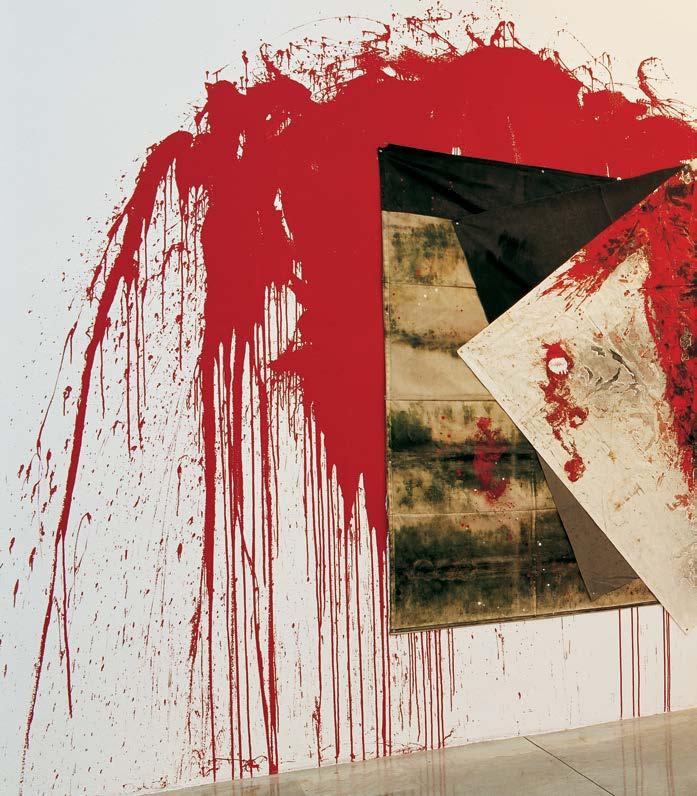

Por Elisa Massardo. Lic. en Historia y Estética (Chile) Imágenes cortesía del artista. España

el horror no se puede graficar de manera literal. Ni con palabras, ni con dibujos. Varios artistas a lo largo del siglo XX han planteado que la mejor forma de exponer las aberraciones que han ocurrido (y siguen ocurriendo), contra el ser humano, es de forma metafórica. Algo que genere impacto, que no sea armónico, que perturbe, que cueste entender lo que estás viendo y tengas que pensar al respecto, reflexionar sobre el color y las formas, mientras ves aquello que es realmente inentendible, así como el genocidio, la guerra o las millones de muertes de civiles por causas político-económicas. Así comienza la obra cruda y totalmente política de José Manuel Ciria.

“Somos animales políticos, quizás más conscientes desde la Revolución Industrial. La abstracción, nunca ha sido el mejor vehículo para expresar ideas concretas”, señala mientras reflexiona sobre la guerra de Ucrania en una obra de gran formato. Pintura, capas de pintura de color rojo intenso, “tiene tanta intensidad y dolor que consigue empatar con la atmósfera grave y deprimente del Guernica”, explica.

Nació en Manchester, en sus palabras, “la ciudad más fea del planeta”, pero siente que carga con la cruz española, aquella que implica que un problema grave te persigue de forma perpetua. Cuando le pregunto sobre su infancia, rápidamente recuerda aquel momento fatídico de la niñez que, lamentablemente, muchas personas vivieron con, sí, una profesora del colegio. “Me destrozó la vida, había que copiar una lámina con un elefante metido en una trampa y un tigre dientes de sable. En la pared del aula, había un gigantesco corcho donde la profesora pegaba con chinchetas los dibujos de todos los alumnos. Yo fui a buscar mi pequeño trabajo y no lo encontré. La profesora había enmarcado el papel con una cartulina naranja y lo había colocado en otra pared solo y apartado del resto, aquello me marcó. Me gusta bromear que me causó bastantes daños cerebrales”, explica.

Y es que la incomprensión sobre lo que es el arte es enorme en todo el mundo. La añeja idea de la mímesis que el hiperrealismo ha traído de nuevo al mundo; la vieja idea de que la representación debe ser lo más fidedigna a la realidad; la vieja idea de que el artista debe ser evaluado constantemente por sus pares, por agentes del arte, por el mercado. La idea de que la pintura ha muerto, pero de forma permanente escuchamos decir: “la pintura volvió con todo”, ¿de qué estamos hablando?

Seguimos profundizando en la vida de Ciria y explica que llegó a España cuando tenía 8 años y medio. “Me encuentro desubicado, pero tuve la suerte de tener un profesor magnífico que tenía la sensibilidad y las ganas de empujar a sus alumnos en la dirección donde objetivamente más desta-

horror cannot be represented literally. Not with words nor with drawings. Throughout the 20th century, several artists have postulated that the best way of exposing the abominations that have happened (and keep happening) against human beings is metaphorically. It must be something impactful, something that is not harmonic, that is disturbing, that makes it hard to understand what you are experiencing and forces you to think about it, reflect on the color, the shapes, while you look at something beyond comprehension like genocide, war, thousands of civilian deaths due to political and economic causes. That is how José Manuel Ciria’s crude and utterly political work starts.

“We are political animals, perhaps a more aware since the Industrial Revolution. Abstraction has never been the best vehicle to express concrete ideas,” he states, as he ponders on the war in the Ukraine on a large-scale piece. Painting, coats of bright red paint with “such intensity and pain that it manages to match the serious and depressing atmosphere of Guernica,” he explains.

He was born in Manchester, which, in his own words, is “the ugliest city in the planet,” but he feels that he bears a Spanish cross, the one that implies that a serious problem that forever follows you. When I ask him about his childhood, he quickly recalls a fateful moment that unfortunately many have experienced with none other than a school teacher. “I ruined my life. We had to copy a picture with an elephant in a trap and a saber-toothed tiger. On the classroom wall, there was a giant cork board where the teacher put up the all the students’ drawings with thumbtacks. I went to look for my assignment and I didn’t find it. The teacher had framed the piece of paper with orange cardboard and put it on another wall by itself, aside from the rest, and that shaped me. I like to joke that it caused me quite a bit of brain damage,” he explains.

Misunderstanding what art really is happens widely all over the world. There are these old ideas that the mimesis in hyperrealism has brought to the new world: the old idea that representation must be as faithful to reality as possible, the old idea that artists must be constantly assessed by their peers, art agents, and the market. The idea that painting is dead, and yet we are constantly hearing: “Painting is back with a bang.” What are we talking about?

As we continue delving into Ciria’s life, he explains that he arrived to Spain when he was 8 and a half years old. “I found myself displaced, but I was fortunate to have a superb teacher who had the sensitivity and desire to push students in the direction where they objectively excelled the

caban, tanto en asignaturas como en deporte”. Claramente, él nunca hizo gimnasia, se pasaba las clases haciendo dibujos con los temas que iban pasando en cada asignatura, aún y cuando trataran sobre religión o tuviera que subirse en banquetas para llegar a la parte superior de la pizarra. “Siempre he pensado que esta profesión me cayó como un castigo. No tuve que decidir nada, no tuve elección”, explica, mientras recuerda que hay una obra que lo impactó de niño: Saturno devorando a su hijo, de Goya, “¿Cómo con unos pocos pigmentos se puede representar el terror de una pesadilla?”

En esta entrevista exclusiva, seguimos profundizando en los conceptos que atraviesan sus pinturas.

¿De qué forma los acontecimientos políticos van marcando tu obra?

Hay algo importante. Cuando Hitler, después de haber sido rechazado cuatro o cinco veces por la Academia de Bellas Artes austriaca, años después manifestó que todo pintor que utilice el verde para representar el cielo y el azul para representar la hierba, debería ser esterilizado. Si la brutalidad de la cita te conmueve y te sientes agredido espiritualmente, es incomprensible que puedan existir artistas, después de la gran revolución del periodo de entreguerras del siglo pasado, que quieran volver a colocar los colores en su lugar natural. Nadie debería, jamás, volver a pintar un cielo azul, en un simple posicionamiento político. Para mí es fácil decirlo, siendo abstracto y habiendo admirado a los fauvistas.

¿Cómo vincular la política a tu pintura?

Me gusta que sigamos con el mismo tema. Con lo que acabo de narrar ahora, puedes entender mi visión y creo que es generalizada. En el arte, la política se posiciona en otro lugar diferente al que lo hace en la sociedad civil actual. No es izquierda, ni derecha, no se trata de partidos ni de ideologías, no es algo de simpleza filosófica. Pienso que de la misma forma que los artistas durante gran parte del siglo XX pensaron que podían transformar la sociedad, cuando sabemos que se produce siempre el movimiento inverso, no importa querer ser ingenuo o naïf, intento percibir firmemente que podemos volver a un punto de partida, en el que nuestro pensamiento de artistas y de todo el resto de actividades, seamos capaces de transformar el mundo. Es una cuestión de abrir los ojos y nuestra mente para organizarnos de otra manera. O conseguimos superar la democracia o será el fin de nuestra era.

En mi pintura, intento muchas veces representar sentimientos, posturas, ideas u obsesiones que tengo en la cabeza, aunque repito, lo abstracto

most, both in subjects and in sports.” He clearly never did gymnastics, he spent his time in class drawing the contents of each subject, even for religious subjects, or even if he had to climb on stools to reach the top of the board. “I have always thought that this profession fell on me as a punishment. I didn’t have to decide anything, I had no choice,” he explains, as he remembers a piece that shocked him as a child: Saturn Devouring His Son by Goya. “How can a few pigments represent the terror of a nightmare?”

In this exclusive interview, we continue to delve deeper into the concepts that run through his paintings.

How do political events shape your work?

There is an important fact. Hitler, years after being rejected four or five times by the Austrian Academy of Fine Arts, stated that any painter that used green to depict the sky and blue to represent grass should be sterilized.

Unless you are moved by the savagery of the quote and feel spiritually attacked, it can be hard to understand that there can be artists after the great revolution of the period between the wars of the last century who want to return colors to their natural place. Nobody should ever paint a blue sky just as a political stance. For me, it’s easy to say, because I’m an abstract painter and I admire Fauvists.

How do you link politics to your work?

I like we’re still on the same topic. With what I just told you, I think you can understand my vision, and I believe it is generalized. In art, politics are positioned in a different place than in our current civil society. It’s not left-wing or right-wing. It’s not about parties or ideologies. It’s not something of philosophical simplicity. I think the same way artists during most of the 20th century thought they could transform society. However, we know that the opposite always happens. Regardless of whether it seems naive, I try to firmly believe that we can go back to the starting point, where our thinking as artists and as people from all other activities is that we are capable of transforming the world. It’s only a matter of opening our eyes and minds to organize ourselves differently. Either we manage to overcome democracy or it will be the end of our era.

In my painting, I try to represent feelings, stances, ideas or obsessions I have in my head. As I said, abstraction is not the best place to do it,

no es el lugar idóneo para ello, pero además, tengo grupos de trabajo enteros dedicados a la política, como la serie Palabras. A la vez hay sendas carpetas llenas de collages donde los protagonistas son la política, la cultura y la religión. Llevo años trabajando con estos objetivos.

En un mundo donde el arte contemporáneo se basa en las investigaciones mostradas a través de formas conceptuales y abstractas, ¿cómo sientes que tu pintura tiene sentido ante el espectador?

Yo no tengo ese tipo de preocupación, me ha venido dado. A pesar de que nací en 1960, me considero hijo de mayo del 68, por lo que de joven, cuando decidí ser artista, necesitaba dotarme de una plataforma de sustentación donde pudiese organizar mis propias ideas. Aparecieron en los años 80 una serie de notas, observaciones y búsquedas de lo que quería pintar e investigar, para aceptarme a mí mismo como artista. Todo ello, fue recogido en el Cuaderno de Notas – 1990, que durante esa década provocaría el desarrollo de mi primera Plataforma Teórica A.D.A. (Abstracción Deconstructiva Automática).

Estas siglas de A.D.A. empezaron a bailar, la voluntad y la obsesión era crear un nuevo marco de pensamiento en pintura. Al final las letras se recolocaron en D.A.A. y después inmediatamente cobraron sentido, conectándolas con las investigaciones que estaba llevando a cabo, Dinámica de Alfa Alineaciones, un aparato diferente que resulta ser una máquina de rayos X para dominar todos los elementos que conforman estructuralmente una pintura. Después llegaría una tercera plataforma A.A.D. de voluntad figurativa. Parece un oxímoron decir que me considero un pintor conceptual. Creo que cuando un espectador se enfrenta a mi trabajo, percibe con bastante claridad que detrás de la superficie existe un inmenso entramado de pensamiento e investigación.

Después de tantos años trabajando, ¿qué es para ti ser pintor?

Percibo mi profesión como una suerte de misión mesiánica. Me tomo muy en serio, primero, no defraudarme a mí mismo y, después, no defraudar a ninguna de las personas que me han apoyado. Como encima, estoy dotado de un ego de formato considerable, no contento con crear una sola plataforma teórica cuyo fruto era ser una máquina de dictar pinturas. Quise dotarme de un nuevo pensamiento, y durante años, a partir del 2000, empecé a desarrollar nuevas ideas. He intentado incluso encontrar apoyo entre todos los críticos de arte que conocí en aquel momento y que lamentablemente no terminaban de entender mi aspiración. Así, un amigo de toda la vida, que me acompaña (Juan Stefa), puntualiza que debo hacer memoria e incluir la palabra “exigencia”. Es cierto, siempre he sido muy exigente con mi trabajo.

but I have entire bodies of work dedicated to politics, such as the series Palabras (Words) or the large folders I’ve created with collages where politics, culture and religion take on a leading role. I’ve been working with these goals for years.

In a world where contemporary art is based on research shown through conceptual and abstract means, how do you feel your painting makes sense to the viewer?

I don’t have that kind of concern, it came organically. Although I was born in 1960, I consider myself a child of May 68, so as a young man, when I decided to become an artist, I needed to provide myself with a platform where I could organize my own ideas. In the 80s, a series of notes, observations, and explorations of what I wanted to paint and investigate in order to accept myself as an artist appeared. All this was compiled in Cuaderno de Notas – 199 0 (Notebook – 1990) which back then led me to develop my first ADA Theoretical Platform (Automatic Deconstructive Abstraction).

Those initials, ADA, started to dance, and the will and obsession was to create a new thought framework for painting. Ultimately, the initials were reorganized to make DAA, and they immediately made sense, connecting them to the research I was conducting, Dynamics of Alpha Alignments. This was a different device that ended up being an X-ray machine to dominate all the elements that structurally make up a painting. Then came a third AAD platform of figurative will. It seems like an oxymoron to say I consider myself a conceptual painter. I think that when viewers encounter my work, they clearly perceive that behind the surface there is an immense web of thought and research.

After so many years working, what does it mean to be a painter for you?

I see my profession as a sort of Messiah’s mission. I take it very seriously to first, not to let myself down and, second, not to let down any of the people who have supported me.

As I am also endowed with a considerably large ego, I wouldn’t have been content with creating a single theoretical platform whose outcome was to be a machine for dictating paintings. I wanted to give myself a new way of thinking, and for years, starting in 2000, I began to develop new ideas. I even tried to find support among all the art critics I met at the time, who unfortunately did not fully understand my aspiration. A life-long friend of mine (Juan Stefa), who is with me, pointed out that I should remember to include the word “demand.” It’s true, I have always been very demanding with my work.

Por Ricardo Rojas Behm. Escritor y Crítico (Chile)

Imágenes cortesía de la artista. Representada por Building Bridges Art Exchange.

reconocer el curso de acción que va tomando nuestra existencia es una incógnita que en contraste a una ecuación matemática puede tomarnos la vida entera despejar. Una faena complementaria a lo dicho por Giorgio Agamben: “La verdad no se encuentra en los hechos, sino en la interpretación de los mismos”. Lo que presupone una construcción del entorno en la que querámoslo o no, se transforma en una mixtura ecléctica, donde reconocemos en el arte esa verdad ineludible, en la que Carla Viparelli, artista visual italiana, se entrega por completo con su particular visión. “Nací en Nápoles. Una ciudad poderosa, una bomba a los pies del Vesubio. Una metrópolis y un lugar arcaico, sus raíces son indomables y los cimientos de los rascacielos nunca podrán sofocarlas. El estudio de Nápoles está en los Quartieri Spagnoli, un barrio obrero muy característico de alta densidad. Por otro lado, siempre he tenido la necesidad de vivir inmersa en la naturaleza, pero no la busco como evasión de la realidad, sino como lección de un entorno más verdadero. La ciudad a menudo engaña. Creo que es importante poder experimentar las dos formas de vida. Pudiendo elegir de vez en cuando la que te hace sentir más vivo”.

¿De qué manera los cuadernos donde recopilas ideas de proyectos y bocetos forman parte de ese postulado donde el arte es un viaje de conjuntas experiencias y conocimiento?

No hay dualismo entre el arte y la vida. Para mí, el arte es una forma de ser, que siempre me ha acompañado. Es un flujo sensorial y mental que registro en cuadernos que recogen las instantáneas, las imágenes fijas, como detectores constantes de datos hidrológicos. El arte no tiene principio ni fin, ni

unlike a math equation, identifying the path our existence should follow is an unknown that can take us our entire lives to solve. Giorgio Agamben spoke on this endeavor: “Truth is not found in the facts, but in their interpretation.” This implies a construction of the environment that, whether we want it or not, transforms into an eclectic fusion where we recognize an inescapable truth in art. Carla Viparelli, Italian visual artist, surrenders completely to this with her own vision: “I was born in Naples, a powerful city, a bomb at the foot of Mount Vesuvius. It is a metropolis and an archaic place; its roots are unbreakable and skyscrapers will never suffocate it. My studio in Naples is located at Quartieri Spagnoli, a traditional and highly populated working-class neighborhood. Conversely, I’ve always needed to live surrounded by nature, but I don’t seek it to escape reality, but rather as a lesson in a more ‘truthful’ environment.” Cities can often be deceitful. I think it’s important to experience both lifestyles and occasionally choose the one that makes you feel the most alive.”

How are your sketchbooks compiling your ideas and sketches part of the notion of art being a journey of shared experiences and knowledge?

There is no duality between art and life. For me, art is a way of being that has always been with me. It is a sensory and mental flow that I record in my sketchbooks with snapshots and static images, like perpetual trackers of water data. Art has no beginning nor end; it doesn’t start nor end with

empieza ni acaba conmigo. Soy una estación de paso. El arte es colectivo, ya que genera incesantemente una comunidad supranacional que cambia y evoluciona en tiempo real. El arte es a la vez un medio y un fin: es una forma de estar en el mundo que transforma cada objeto en un proyecto.

Esta artista exhorta la realidad con un quehacer artístico que, en definitiva, se convirtió en un motivo para existir y que se fue incubando desde su infancia, cuando su padre le obsequió una caja de pinturas al óleo, y de ahí en adelante se fueron añadiendo una serie de exponentes del arte universal que decretaron un antes y un después en su obra. Eso sin contar aquellos que, por así decirlo, fue absorbiendo casi por osmosis, por el hecho de tener como telón de fondo la emblemática ciudad de Nápoles.

¿Qué puedes decirme sobre tus referencias artísticas?

La referencia artística que determinó un punto de inflexión para mí fue Joan Miró, a quien conocí mientras estudiaba para un examen de Historia del Arte Contemporáneo en la Universidad de Nápoles. Estudiando entendí el mecanismo de su visión, descifré su lenguaje. Miró tenía una función didáctica. Fui a Barcelona, a la Fundación Miró, y a partir de entonces comenzó una experiencia consciente del arte. Otro momento importante fue cuando me enfrenté al cuadro «Flandern» de Otto Dix en Berlín: allí no fue didáctica sino impacto total: la desesperación de la guerra que devuelve el sentido profundo de estar en el mundo. Para mí, las referencias más significativas proceden de la filosofía: Kant, los presocráticos, Platón, la metafísica.

me. I’m a transit station. Art is collective, as it never ceases to create a supranational community that changes and evolves in real time. Art is both means and end: it’s a way of being in a world that transforms all objects to projects.

This artist enliven reality with her artistic endeavor, which became her reason for existence and has brewed since her childhood, after her father gave her a box of oil paint. Since then, a series of icons of world art have inspired her, marking a clear before and after in her work. Some other referents she absorbed unintentionally, almost by osmosis, just from her having the emblematic city of Naples as her backdrop.

What can you tell me of your art inspirations?

The one that represented a turning point for me was Joan Miró, who I learned about while I was studying for a contemporary art history exam at the University of Naples. By studying, I understood the inner workings of his vision; I decoded his language. Miró had a didactic function. I went to Barcelona, to the Miró Foundation, and from there I experience art more with awareness. Another important moment was when I saw Fladern by Otto Dix in Berlin. In that case, it wasn’t about didactics, but total impact: the despair of war that restores a deep sense of being in the world. For me, my most significant referents come from philosophy: Kant, Pre-Socratic philosophers, Plato, metaphysics.

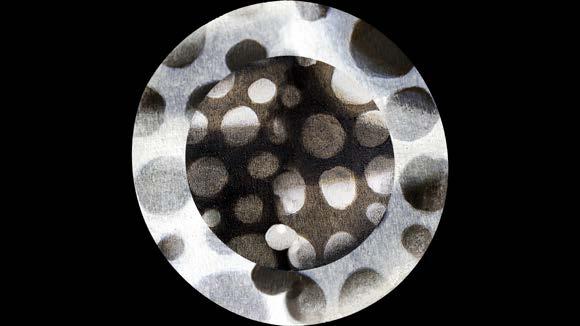

En tu vasta trayectoria, ¿cómo logras unir esta doble pertenencia entre el pensamiento científico-filosófico y el pensamiento artístico o estético?

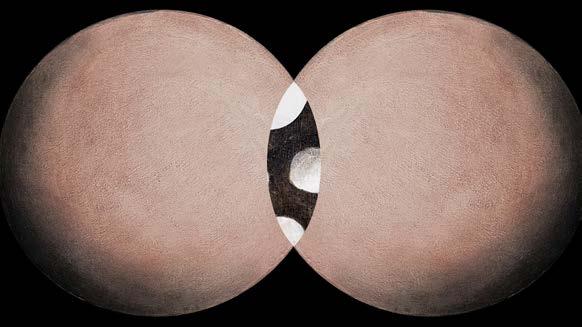

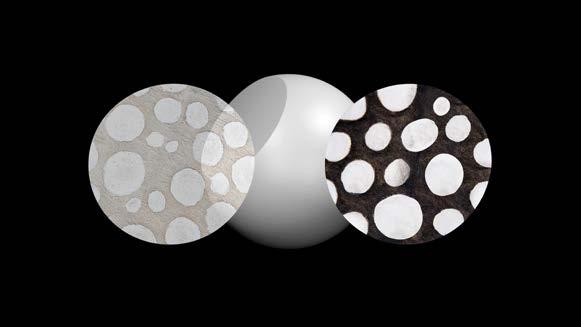

Cuando profundizo en un tema, como el silicio en Silicosophy, paso horas y horas estudiando. Y cuanto más estudio, más descubro mundos. Descubro similitudes inesperadas como, por ejemplo, entre el comportamiento de los átomos de silicio y el de los aficionados que hacen cola para entrar en el estadio. Y la conexión y superposición de diferentes órdenes de realidad es la base de mi investigación figurativa, que es por tanto multidimensional.

Exploras el lado estético de la ciencia y la estética del cambio, de una realidad a otra, y la belleza en el acto de modificación y representación “humanizando” aquello que simula no tener vida. En ese contexto, ¿cómo definirías la belleza de nuestros compañeros cotidianos: teléfonos celulares, paneles solares, vidrio, microchips, sales o geles de silicona?

La expresión “estética del cambio de una realidad a otra”, representa muy bien mi trabajo. El silicio es un emblema ideal de todo esto porque, por un lado, es un elemento que existe en la naturaleza (arena, diatomeas, cola de caballo, etc.) y, por otro, es el componente fundamental de toda tecnología de la información porque, convenientemente tratado, es capaz de transmitir una cantidad infinita de información. Por tanto, el mismo elemento está en la base, tanto de una cadena de procesos naturales como de una cadena de procesos tecnológicos artificiales. Es una piedra filosofal capaz de generar mutaciones alquímicas.

In your long career, how do you manage to connect this dual belonging to both scientific-philosophical thinking and artistic or aesthetic thinking?

When I delve into a topic, like I did with silicon in Silicosophy, I spend hours and hours studying. The more I study, the more I discover worlds. I discover unexpected similarities between the behavior of silicon atoms and that of the fans standing in line to enter the stadium, for instance. The connection and overlapping of different orders of reality is the basis of my figurative research, which therefore is multidimensional.

You explore the aesthetic side of science and change, from one reality to another, as well as the beauty in modification and representation, “humanizing” what seemingly has no life. In that context, how would you define the beauty of our daily companions: cellphones, solar panels, glass, microchips, silicon salts or gels?

The expression “aesthetics of change from one reality to another” represents my work very well. Silicon is an ideal emblem of all this because, on the one hand, it is an element that exists in nature (sand, diatoms, horsetail, etc.) and, on the other hand, it is the fundamental component of all information technology because, when properly processed, it is capable of transmitting an infinite amount of information. Thus the element is at the core of both a series of natural processes and artificial technological processes. It is a philosopher’s stone capable of creating

Es similar a la glándula pineal de Descartes, en la que res cogitans y res extensa, pensamiento y naturaleza, encuentran su equilibrio. Todo esto es para mí la belleza: una iluminación, una revelación, una intuición profunda que llega sin que la hayas buscado y que te hace ver las cosas de otra manera.

Has extrapolado el concepto de “Zona Franca” incursionando en un ámbito mercantil, económico/geopolítico para multiplicarlo en otros contextos de carácter semántico, geológico, filosófico, metafórico, ¿de qué forma eso se conecta con Mimesis o Silicosofia u otros proyectos vinculados con la naturaleza, revelando identidades ocultas a través de símbolos y metáforas?

Me fascina el hecho de que la dinámica del mundo natural revele mecanismos profundos que también funcionan en otros contextos, como la política, la historia, la lógica, la lingüística, entre otros. La filosofía y el arte, con métodos diferentes, tienen la capacidad de investigar y profundizar en estas leyes comunes de funcionamiento, que yo llamo “los secretos de la naturaleza”. Me interesa ir más allá de la apariencia de lo múltiple para captar similitudes y conexiones a veces imprevisibles entre realidades diferentes.

Tomando el paralelismo entre pensamiento y naturaleza. ¿Cómo integras lo análogo con lo digital o performances como “Falso movimiento”? El encuentro con las nuevas tecnologías ha sido decisivo en mi investigación artística. Forman parte del proceso creativo de cada una de mis obras, ya sea en la fase de diseño, en un óleo, o como producto

alchemical mutations. It is similar to Descartes’ pineal gland, where res cogitans and res extensa –thinking and nature– find a balance. Beauty is all this to me: enlightenment, a revelation, a profound intuition that comes unsought and makes you see things in a different way.

You have extrapolated the concept of “Free Trade Zone” by venturing into a mercantile, economic/geopolitical sphere and replicating it in other contexts of a semantic, geological, philosophical, metaphorical nature. How does this relate to Mimesis, Silicosophy, or other projects linked to nature, revealing hidden identities through symbols and metaphors? I’m fascinated by the fact that the dynamics of the natural world reveal profound mechanisms that also work in other contexts, such as politics, history, logic, and linguistics, among others. Both philosophy and art, though with different methods, have the ability to research and explore these common laws of operation that I call “nature’s secrets.” I’m interested in going beyond the appearances of multiplicity to catch similarities and sometimes unpredictable connections between different realities.

Bearing in mind this parallel drawn between thinking and nature, how do you bring together analog with digital or performances like False Motion? Encountering new technologies has been decisive in my artistic research. They are part of the creative process of all my artwork, whether in the design phase of an oil painting,

artístico final o, incluso, en la animación de vídeos. Para hacer una animación en vídeo parto de mis obras «físicas» (dibujos o pinturas). El tratamiento digital las pone en movimiento como por arte de magia. A menudo, durante el proceso, extraigo algunos momentos del flujo de la animación, los aíslo y los pinto. Y así cierro el círculo que empieza con la destreza manual, pasa por la electrónica y luego vuelve a la destreza manual. Es como tener muchas más herramientas a mi disposición: no sólo la pintura, sino también el software, el gesto, la acción escénica. De este modo, la elección de la mejor manera de expresar una visión o un concepto es más amplia y, en consecuencia, el resultado es mejor.

¿Crees que con tu obra invitas a las generaciones futuras a mirar al pasado y aprender de las experiencias? Pensando en rescatar la belleza de realidades venideras?

Claro que sí. Creo en el injerto. El pasado genera el futuro cuando se injerta adecuadamente, como una planta. Mi trabajo representa este injerto de innovación en la tradición. El presente no existe, sino que hay un principio de equilibrio constante entre lo que ha sido y lo que será. Leonardo da Vinci describe así el agua de un río que fluye: “lo último de lo que se fue y lo primero de lo que vendrá”.

En esa afluente, Carla Viparrelli corre con ventaja, por el simple hecho de considerarse, según sus propias palabras: una artista indepen-

the end product, or even in video animation. For the latter, I start with my “physical” work (drawings or paintings). Digital processing makes then move, as if by magic. Throughout the process, I take some moments from the animation, I isolate and paint them. That is how I end the cycle that starts with a manual craft, goes through a digital process, and then goes back to manual. It’s like having many tools at my disposal: not just painting, but also software, gestures, and stage performance. This way, the choice of the best way to express a vision or concept is broader and, consequently, the result is better.

When it comes to salvaging the beauty of future realities, do you think you encourage future generations to look at the past and learn from experience through your work?

Of course. I believe in propagation. The past begets the future when properly propagated, like a plant. My work represents this propagation and merger of innovation and tradition. The present does not exist, instead there is a principle of constantly active balance between what has been and what will be. Leonardo da Vinci thus describes the water of a flowing stream, “that has gone before and the first of what is still to come.”

In that stream, Carla Viparrelli flows ahead, by the simple fact of regarding herself as an artist who is, in her own words, indepen -

diente que no procede de una postura ideológica, sino de una trayectoria espontánea construida automáticamente, pavimentando su propio camino por consonancia y convibración. Esta última entendida como una fuerza dinámica que la impulsa desde la filosofía al arte, asumiendo una doble pertenencia en la que no podemos dejar fuera a la bullente Nápoles, una metrópoli que, al ser su lugar de origen, es el motor de partida de donde surge esa intensidad que la caracteriza.

A esto le adicionamos un bagaje cultural en el que resplandecen los influjos de grandes filósofos tan prominentes como Aristóteles, con el que comparte una cosmología ligada a la naturaleza o Physis, que es el principio del movimiento y del cambio. Ciertamente, una permuta determinada por la convicción de que ella es una estación de paso. Porque el arte es un “bucle infinito”, que no tiene ni principio ni fin y su vida continúa girando en torno a ese axioma incuestionable.

Carla Viparelli no es sólo otro eslabón o ensamblaje más, ya que como artista está atenta al cambio y sabe adaptarse a nuevas formas de expresión, articulando un relato vivo de donde emergen la intuición, la creación y ese sinfín de conexiones con las que intenta responder nuevas interrogantes, las que después de largos periodos de reflexión se transforman en elocuentes proyectos artísticos con los que espera despejar algunas de las tantas incógnitas que el arte y la vida traen en su misteriosa alforja.

dent from ideological stances, and prefers a spontaneous course built automatically, paving her own path by consonance and covibration , which can be regarded as the dynamic force that drives her from philosophy to art, taking on a dual belonging. In this, we cannot leave out the bustling Naples, a metropolis that, as her place of origin, is the starting point from which arises the intensity that defines her.

Moreover, there is a cultural heritage with bright influxes of great and prominent philosophers such as Aristotle, with whom she shares a worldview linked to nature –or physis , the source of movement and change. She certainly adheres to the conviction that she is a transit station, because art is an “infinite loop” with no beginning or end, and her life keeps spinning round that unquestionable axiom.

Carla Viparelli is not only another link or cog. As an artist, she is mindful of change and knows how to adapt to new forms of expression, articulating a living story from which intuition, creation and endless connections emerge. Through these, she tries to answer new questions and, after long periods of reflection, they are transformed into eloquent artistic projects with which she hopes to clear up some of the many unknowns that art and life bring in their mysterious bag.

Por Elisa Massardo. Lic. en Historia y Estética (Chile) Imágenes cortesía de la artista.

Representada por Judas Galería.

hace poco un amigo, hombre heterocis, me comentaba que ahora le da miedo tener citas y relaciones sexuales porque puede ser denunciado posteriormente. Respondí de forma inmediata que las mujeres estamos acostumbradas a vivir con miedo. Me miró y sonrió comprendiendo que el miedo pareciera ser parte de la sociedad actual, donde hemos normalizado la violencia independiente del género, a tal punto que preferimos vivir con desconfianza y temor, exagerando los cuidados para evitar dolores profundos. Aún así, la violencia y el abuso existen.

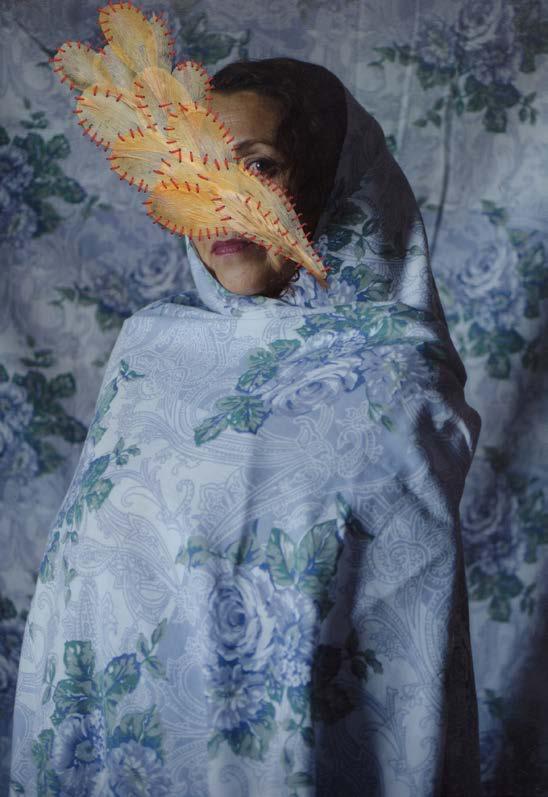

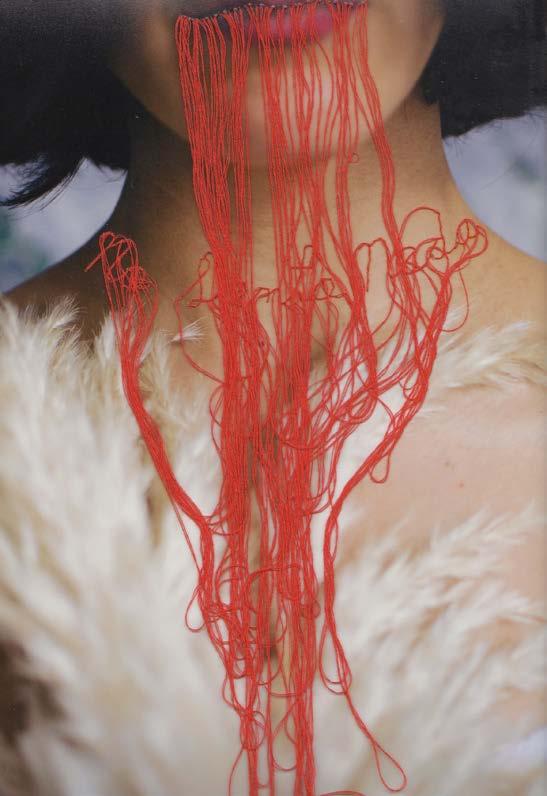

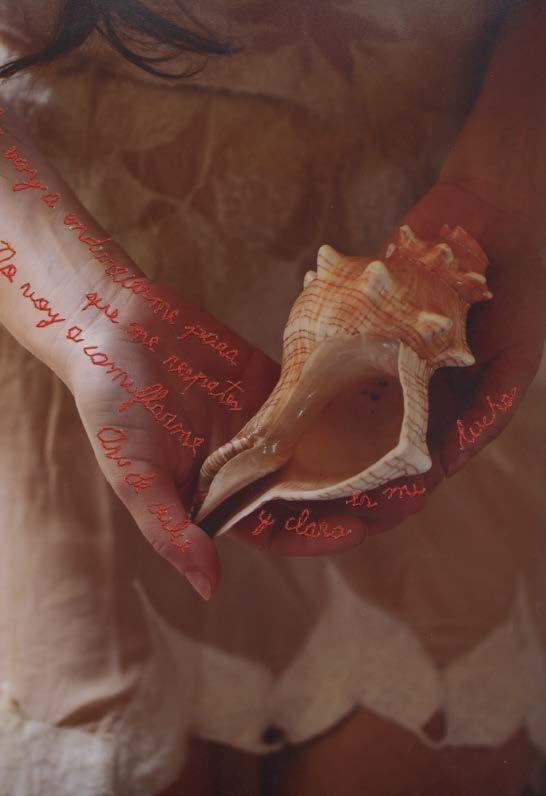

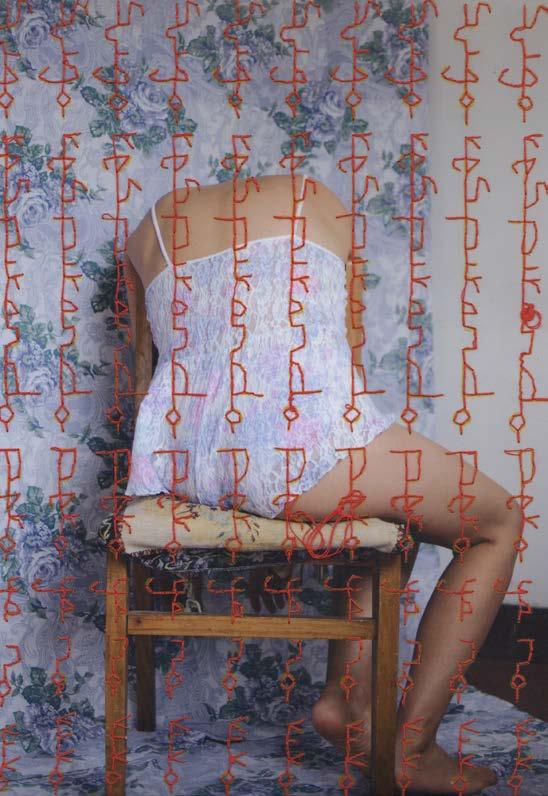

Carolina Agüero siempre ha trabajado sobre el género femenino y el abuso. En su obra, 74 nudos, por ejemplo, cuenta historias y testimonios reales de mujeres que fueron abusadas y violentadas en el espacio doméstico, sufriendo de “violencia silenciosa” de manera permanente, normalizando las agresiones y el sufrimiento. El bordado en sus fotografías entra de manera directa, cada puntada invita a visibilizar el dolor en todas sus formas, “la acción de repetir cada palabra es casi una representación de castigo que nos han inculcado, (desde colegio, si nos portábamos mal, nos hacían repetir 100 veces la misma palabra) Romper y atravesar la aguja en el papel es casi un acto performático; el enhebrar la aguja con el hilo rojo, atravesar el papel, rasgarlo, dejar esos nudos al aire y que se note la imperfección, es el acto de casi dejar al desnudo nuestra verdad”, explica la artista.

Para esta serie de trabajos, Carolina realizó un trabajo directo con las retratadas, quienes compartieron sus historias. Todas atravesadas por el silencio y el dolor de haber sido abusadas por sus padres o familiares; maltratadas por sus parejas; acosadas en el espacio público y privado. ¿Qué pasa cuando la violencia se normaliza a tal punto que es imposible desprenderse?

Y todo a través del cuerpo

Así como el dolor, el cuerpo es la esencia del trabajo de Carolina Agüero, quien a través de la fotografía intervenida logra expresar y narrar diversas historias permeadas siempre por la violencia, ya sea de género, ya sea histórica. “Me gusta observar el cuerpo humano, indiferente de su género. Saber qué pasa dentro de su propia representación como ser. Me pregunto ¿cuáles serán sus cicatrices más ocultas?, ¿cuales son sus dolores más profundos?, ¿cómo se siente al liberar sus emociones? En base a estas pequeñas observaciones y cuestionamientos, he llegado y dirigido la mirada al cuerpo porque es la mejor representación de nuestra existencia”.

Así, en 2013 comenzó trabajando Metamorfosis: 100 cuerpos de mujeres, donde reúne a mujeres de diferentes edades y retrata parte de sus cuerpos, creando un espacio íntimo, casi clínico y minimalista. A cada una de ellas les pidió que escribieran en un cuaderno lo que sentían: “¿por qué se desnudaban?, ¿cómo se sentían después de la sesión? Ya que en algunos casos se mostraban sus cicatrices en partes íntimas, lo

recently, a hetero-cis male friend told me he is scared of dating and sex because he can be reported after. I immediate answered that women are used to living with fear. He looked at me and smiled, understanding that fear seems to be a part of our society nowadays, and we have normalized violence, regardless of gender, to the extent that we would rather live with distrust and fear, and be overly cautious to avoid deep pain. And yet, violence and abuse still exist.

Carolina Agüero has always addressed the female genre and abuse. In her piece 74 nudos (74 knots), for instance, she narrates the stories and real testimonies of women who were abused in the domestic sphere suffering a constant “silent violence” where aggressions and suffering became the norm. The entrance of embroidery in her photographs is direct. Each stitch is an invitation for pain in all its forms to become visible: “repeating each word is almost the representation of a punishment we have been given (at school, if we misbehaved, we were made to repeat the same word 100 times). Severing and piercing paper with a needle is almost a performance act; threading the needle with a red thread, piercing the paper, tearing it, and leaving these knots visible so imperfections can show, is almost like barning our truth,” the artist explains.

For this series, Carolina worked directly with the portrayed women who shared their stories. They all experienced the silence and pain of being abused by their parents or relatives, mistreated by their partners, harassed in public or private spaces. What happens when violence is normalized to the point that it is impossible to become detached?

Everything through the body

Just like with pain, the body is the essence of Carolina Agüero’s work. Through intervened photographs, she manages to express and narrate different stories imbued with violence, whether gender-based or historical. “I like looking at the human body, regardless of gender, knowing what happens within its representation as a being. I wonder, what are its most hidden scars? What are its deepest pains? How does it feel when freeing its emotions? Based on those small observations and questions, I have turned my attention to the body because it’s the best representation of our existence.”

That is how, in 2013, she started working on Metamorfosis: 100 cuerpos de mujeres (Metamorphosis: 100 female bodies), which gathers women of different ages and captures part of their bodies, creating an intimate, almost clinical and minimalist space. She asked each of them to write what they felt in a notebook: “Why did they get naked? How did they feel after the session? This because, in some cases, the women showed

que era un tabú en ese momento. Les daba pudor exponerse, pero el acto de posar las hacía sentir vivas. Comencé a reflexionar que existe un gran porcentaje de mujeres dañadas, con heridas guardadas que sufrían violencia constante”, y este trabajo la llevó a profundizar en las historias más allá de la fotografía, para impregnar la imagen de una narrativa que sea capaz de reflejar la sórdida realidad de cualquier persona, porque sí, cualquier persona puede ser víctima de abuso o haberlo sido.

Y quiso dirigir este nuevo proceso a algo más sutil. Más privado. Las historias eran muy fuertes, por lo que empezó a tomar registro de detalles, o desenfocar la toma. Las retratadas comenzaron a pedirle ir a su casa, a sus espacios más íntimos. Para darle continuidad a la serie, mantuvo la escenografía: una sábana planchada con rosas grandes, casi perfectas, con un color frío que “te hace sentir en armonía y en cuidado”. Además, ocupó luz natural de mañana o de atardecer, “para generar esa atmósfera ficcionando la propia realidad, hermoseando lo que ya estaba dañado. Todo se dio muy orgánico”.

La infancia en el centro de la problemática

Luego de 5 años, llegó a Carolina una solicitud: hacer una sesión especial de fotos a una niña de 12 años, al aire libre, junto al mar. Había sido abusada por su tío. Pensaron que una sesión fotográfica podía ayudarla a liberar ese dolor. El dolor más fuerte que ha retratado Carolina. “No trabajo con niñeces, con menores de edad. En toda la sesión ella fue acompañada por su madre. Pero ese mismo año llegó una ola de violencia y femicidios en Chile y Latinoamérica. El tema sigue estando bastante fuerte y profundo”, explica.

A esto, se suma la triste historia de Noa Pothoven. Una niña de 11 años que fue abusada sexualmente. A los 14 años fue víctima de violación. El estrés postraumático, la depresión y los problemas alimenticios la acompañaron desde ese momento y no le permitieron vivir en paz nunca más. Solicitó la eutanasia, ya que vivía en Holanda, pero se la negaron por ser demasiado joven, con la intención de que el tratamiento psicológico haga efecto. Pero su decisión de morir estaba clara. Se negó a recibir alimentos y bebidas, hospitalizada en su propia casa, falleció con tratamiento paliativo. Sus padres la acompañaron. El dolor del abuso sexual y la violación puede ser así de grande.

“Su historia sacude hasta lo más profundo: habla de no querer vivir, de la imposibilidad de superar el trauma y el daño del abuso. Sus escritos son tan intensos y dolorosos que erizan la piel, invitando a una reflexión sobre ella y sobre las muchas mujeres que aún sufren en silencio”, señala Carolina y desde ahí surge la frase: “Por fin voy a ser liberada de mi sufrimiento porque es insoportable”, en honor a su muerte e historia; así como, “en realidad ya hace tiempo que no vivo, sobrevivo, e incluso eso casi no lo hago. Respiro, sí, pero ya no vivo”.

scars in intimate places, which was taboo at the time. They were embarrassed to expose themselves, but the act of posing made them feel alive. I started thinking that there is a large percentage of broken women, with scars hidden away, that suffered from violence constantly,” and his work led her to delve deeper into the stories, beyond photography, to imbue images of a narrative capable of reflecting the sordid reality of any person, because indeed anyone can be a victim or have been a victim of abuse.

She then sought to channel this new process towards something more subtle. More private. Stories were very heavy so she started recording the details, blurring shots. The women portrayed started asking her to come to their houses, their most intimate spaces. To give the series continuity, she kept the staging the same: an iron bed sheet with big roses, almost perfect, with a cool color that “makes you feel in harmony and cared for.” She also used natural light in the morning or at dusk “to create an atmosphere of make reality fiction, to make what’s broken beautiful. Everything happened very organically.”

Childhood as the center of the issue

After 5 years, Carolina received a request: to make a special session outdoors next to the sea for a 12-year-old girl. She had been abused by her uncle. They thought that the photo session might help her feel free of that pain. That was the most acute pain Carolina has portrayed. “I don’t work with children, with minors. She was with her mother during the entire session. But that was the year a wave of violence a femicides came to Chile and Latin America. The issue is still quite heavy and deep,” she explains.

The sad story of Noa Pothoven came to add to this. She was an 11-year-old girl that was sexually assaulted. At 14 years old, she was raped. Post-traumatic stress, depression and eating disorders followed from there and never let her live at peace. She requested to be euthanized, as she lived in the Netherlands, but she was denied for being too young, in the hopes that the psychotherapy might work. However, her decision to die had been made. She refused food and drink, was hospitalized in her own house, and died in palliative care. Her parents were with her. The pain from sexual abuse and rape and be than great.

“Her story shakes you to the core, the not wanting to live, not being able to move on from trauma and the damage of abuse, her story and her writing are son profound and painful it makes your hair stand on end. In these lie a reflection of her and many more women that suffer in silence,” Carolina states. Noa’s words come to mind: “I will be released because my suffering is unbearable,” honoring her death and her story. “I have not really been alive for so long, I survive, and not even that. I breathe but no longer live.”

Por Anubis Burgos. Periodista (Chile)

Imágenes cortesía del artista y de Sergi Battle. España

Representado por Pigment Gallery.

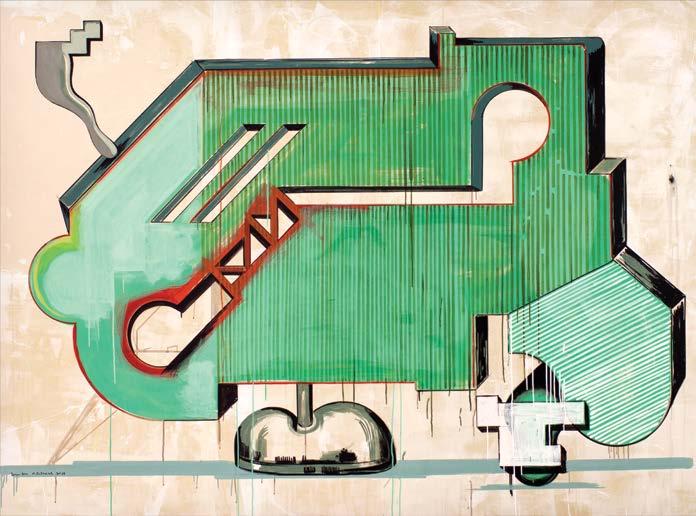

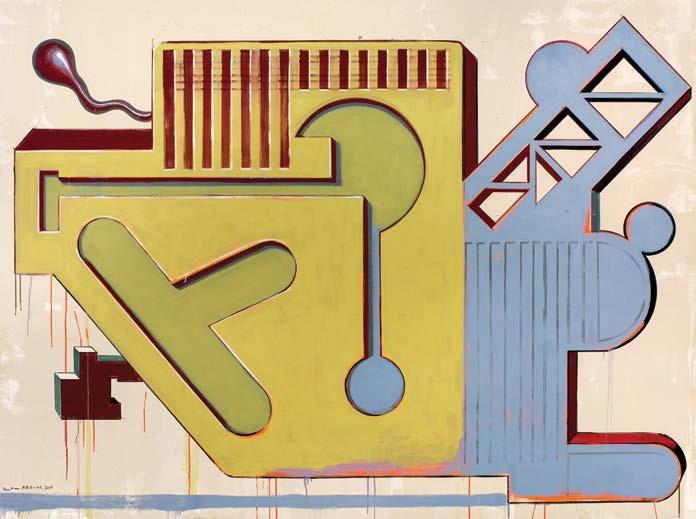

nuestra infancia nos define. Antes de la adolescencia, niñas y niños son increíbles artistas, pero un día escuchan que el arte “no sirve para nada” y, de paso, que “lo hacen mal”. La gran mayoría se frustra y nunca más vuelve a ese preciado regalo de la libertad imaginativa. La sociedad les arrebata abruptamente la posibilidad de ser creadores. Al menos, eso piensa Jordi.

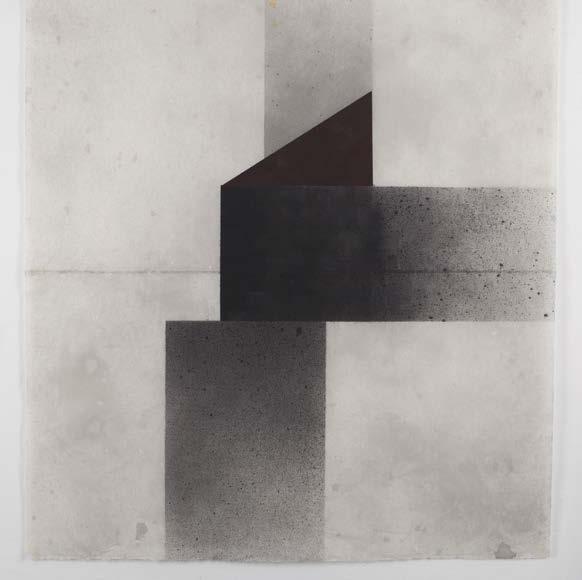

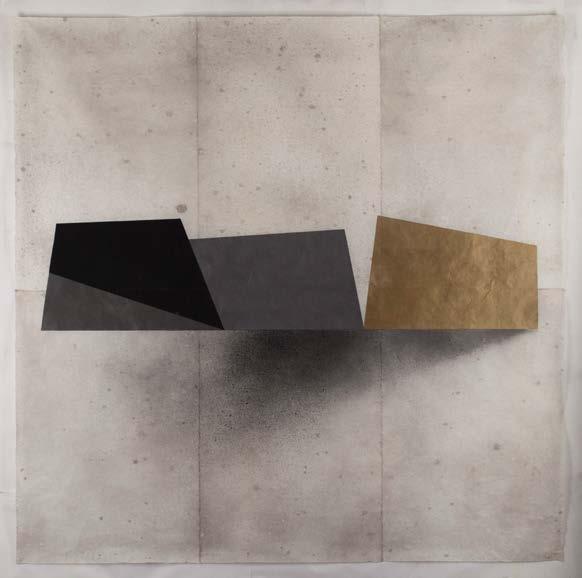

Su proceso creativo se basa en la observación y escucha activa de lo cotidiano y en las formas que se encuentran tanto en yacimientos arqueológicos, como en nuestra tecnología de punta. Estas formas inspiran sus cuadros al óleo, los cuales son un homenaje al enorme legado de la pintura del pasado.

Para Jordi estas pinturas desafían el tiempo. Las formas que utiliza son herramientas que se encuentran a lo largo de las civilizaciones, desde lo sagrado a lo tecnológico y que nos han permitido evolucionar hasta nuestros días. Hoy son parte de un patrimonio colectivo (aunque, asegura, hay quienes se creen dueños de estas formas arquetípicas) “Estamos donde estamos gracias al arte. Siempre insisto en la importancia de guardar silencio, para estar atentos y, sobre todo, compartir. Mi trabajo se nutre de la calma”.

Aunque las pinturas al óleo constituyen una parte intrínseca de Jordi, el papel oriental es otro de sus pilares al momento de plasmar una obra. Su fragilidad le permite presentar un elemento central en sus creaciones, donde las formas son envueltas en una atmósfera de ingravidez, como si el tiempo y el espacio se detuvieran y, al mismo tiempo, intentaran inundar el campo de visión de quien la contempla.

Hasta Nueva York llega la belleza de Girona

Para Jordi su ciudad natal era gris. “No era más que un puente para cruzar a Francia. Incluso Picasso se detuvo unos días antes de viajar a París por primera vez. Girona conversa con vestigios del imperio romano y la huella de una comunidad judía llena de cabalistas, los cuales plasmaron sus creencias por todo el barrio antiguo”.

A los 14 años, el pintor gironí Isidre Vicens lo acoge en su taller, transformando por completo su mundo pictórico y su manera de ver la vida. “Todo lo que aprendí sobre arte me lo enseñó él, era un humanista y un libre pensador con una pedagogía excepcional”, declara. Después de tres años se mudó a Barcelona, donde terminó sus estudios de Bellas Artes en la Facultad de Sant Jordi.

our childhood defines us. Prior to adolescence, children are incredible artists, but one day they hear that art “is good for nothing” and, besides, that “they are doing it wrong”. Most get frustrated and never return to the precious gift of creative freedom; society abruptly robs them of the possibility of becoming creators. At least that’s what Jordi thinks.

His creative process is based on observation and active listening of dayto-day aspects and shapes he finds in both archaeological sites and in our state-of-the-art technology. These shapes inspire his oil paintings, which pay tribute to a legacy of the great painting of the past.

For Jordi, these paintings challenge time. The shapes he uses are tools found across different civilizations, from sacred to technological tools that have allowed us to evolve to the present day. Today, these are part of a collective heritage, although, he assures, there are some who believe they own these archetypes: “We are where we are thanks to art. I always stress the importance of being silent, being mindful and, above all else, sharing. My work is nurtured by calmness.”

While oil paintings constitute an inherent part of Jordi’s work, Japanese paper is another of his pillars while creating artwork. The frailty of this material allows him to present a central element in his creations, where shapes are surrounded by an atmosphere of weightlessness, as if time and space were standing still and, at the same time, trying to overflow viewers’ field of vision.

The beauty of Girona reaches New York

For Jordi, his native city was gray. “It was merely a bridge away from France. Even Picasso stopped a few days before traveling to Paris for the first time. Girona has remains of the Roman Empire and the traces of a Jewish community full of Kabbalists, who spread their beliefs all over the old quarter.”

At 14 years of age, the Gironí painter Isidre Vicens welcomed him to his studio, completely transforming his visual world and his way of viewing life. “He taught me everything I learned about art. He was a humanist and free-thinker with an exceptional pedagogy,” he states. Three years later, he moved to Barcelona, where he finished his fine arts studies at the Sant Jordi Academy.

Pures Ombres , 2023, gouache y tinta china sobre papel japonés, 155 x 145 cm.

Hace prácticamente 10 años atrás, en el otoño del año 2015, realiza una estancia en New York. Aquella experiencia transforma su trabajo. Conoce de primera mano las obras de artistas como Sol Lewitt, Fred Sandback, Agnes Martin y Ellsworth Kelly. Con esa vivencia entendió por qué el arte es necesario en nuestra sociedad. Según dice el propio artista “es la clave para poder expresar las emociones, el conocimiento, e iluminar los caminos que nos permitan avanzar.

Insumiso

Con vehemencia, dice que le gustaría compartir un dato. “A los 18 años planté cara al Estado español negándome a realizar el servicio militar, me declaré insurrecto por razones éticas y puramente humanitarias”. Esta cruzada, menciona, le otorgo ese primer impulso hacia un abismo imaginario: el vértigo de la caída libre. Recuerda el año 1985 como “uno de esos grandes acantilados de Caspar Friedrich”.

Aún no había cumplido los 9 años cuando el renacimiento italiano lo abdujo por completo, seguramente por el hecho de sus idas y venidas a la tierra natal de su madre, muy cerca de Nápoles y por ser heredero de una familia de artistas, que por desgracia nunca conoció. Pero el mundo se compone de arte y, en sus momentos más solitarios y sombríos, lo acompañó el impresionismo francés, la pintura catalana y artistas como Miró, Picasso, Tàpies, e incluso los norteamericanos Pollock y Rothko. “La principal influencia de mi adolescencia, sin lugar a dudas fue Tápies. Cómo no. En aquella época era omnipresente y su sombra muy alargada. Sin duda un pintor repleto de simbología y belleza, aunque él se empecinó a crear un arte basado en lo antiestético”.

Observar una obra Martoranno

A Jordi le interesan dos cosas. La primera, es que el proceso de creación transforme su conciencia y su actitud. La segunda, es más difícil. Busca que su arte envuelva la experiencia y mirada del espectador, mientras él mismo se reconoce en las obras. Quiere que ese sentimiento se vuelva atemporal, precisamente por el contenido arquetípico y, a veces, simbólico de las exposiciones.

Su carrera es extensa. Los reconocimientos le llegan desde todas partes, pero compara sus intenciones con un espejo, en el que cualquier persona puede mirar su reflejo y percatarse de la gravedad, en tanto la Tierra sigue girando como las manillas del reloj. Entonces se quedan ahí, estáticos. El color gris de fondo le recuerda sus días más solitarios, pero la Tierra sigue girando. Y mirando el punto focal, vuelven a esa época de su vida: todo gris.

Almost 10 years ago, in the fall of 2015, he was an artist-in-residence in New York, an experience that transformed his work. He got to see the work of artists such as Sol Lewitt, Fred Sandback, Agnes Martin, and Ellsorth Kelly in the flesh. Through that experience, he learned why art is necessary for our society. As the artist said: “it is the key for expressing emotions, knowledge, and shed light on the paths that allow us to move forward.

He vehemently states he would like to share a story. “When I was 18 years old, I defied the Spanish government by refusing to do military service. I declared myself an objector for purely ethical and humanitarian reasons.” This crusade, he mentions, gave him a first push towards an imaginary abyss: the vertigo of free falling. He recalls 1985 as “one of Caspar Friedrich’s great cliffs.”

He was not yet 9 years old when Italian Renaissance fully absorbed him, probably due to his comings and goings to his mother’s homeland, near Naples, and for being the heir of a family of artists, whom he unfortunately never knew. But the world is made up of art and, in his loneliest and gloomiest moments, he was surrounded by French impressionism, Catalan painting and artists such as Miró, Picasso, Tàpies, and even the Americans Pollock and Rothko. “My main influence during my teenage years was definitely Tàpies. How couldn’t he be? At the time he was omnipresent and he casted a large shadow. He was undoubtedly a painter full of symbolism and beauty, although he was determined to create an art based on the unaesthetic.”

Examining artwork by Martoranno

Jordi is interested in two things. The first, he wants his creative process to transform his own awareness and attitude. The second is harder. He aims for his paintings to surround viewers’ gaze and experience, as they recognize themselves in them. He wants that feeling to become timeless, especially due to the archetypal and sometimes symbolic content of his artwork.

His career has been long. Acknowledgments come from everywhere, but he compares his intentions with a mirror: any person can see their reflection and notice the seriousness, as the world keeps spinning around like clock handles. And there they stand still. The gray from the background reminds them of their loneliest days, but the world keeps spinning. Once they find the center point, they go back to that time in their lives where everything was gray.

Por Lucía Rey. Académica e investigadora independiente (Chile) Imágenes cortesía del artista. Representado por Building Bridges Art Exchange.

De

l as obras aquí presentes hacen parte de la exposición From Origins to Horizons, expuesta en el Museo de Arte de las Américas (AMA) en Washington D.C. En ella, el artista salvadoreño plantea visualmente la pregunta por la noción de origen y horizonte en América, atravesado por la memoria latente del largo proceso de aculturación en Indoamérica llevado a cabo en la colonización. El artista elabora, simbólicamente, las heridas abiertas de Abya Yala, a través de recursos plásticos que remiten a huellas y coordenadas de memorias eclipsadas por la sombra de la modernidad.

Estas obras están en el espectro estético de la dialéctica negativa (Th. Adorno), donde se encuentran, en la misma imagen, la figuración de las herramientas de Occidente a partir del extractivismo de la savia de los pueblos originarios. En este sentido, las obras pictóricas de la muestra están hiladas por la persistencia de las hojas de oro sobre pigmentos naturales (como el añil o índigo, encajes, tierras, arenas, hoja de banano, maíz o de maguey), contrastando el valor de la sacralidad colonial y el oro con el sentido profundo de lo sagrado para los pueblos originarios, encontrado en la madre tierra. Esta dialéctica busca poner en contraste y también reflejar al espectador el cómo esta penetración ha ido constituyendo, culturalmente, los valores del mundo occidentalizado.

the pieces featured here are part of the exhibition From Origins to Horizons, shown at the Art Museum of the Americas (AMA) in Washington DC. In it, the Salvadorian artist questions, through visuals, the notion of the origin and horizons of America, exploring the latent memory of the lengthy process of acculturation of indigenous peoples throughout colonization. The artist symbolically crafts the open wounds of Abya Yala through visual resources that refer to the traces and coordinates of memories eclipsed by the shadows of modernity.

These pieces fall under the aesthetic spectrum of negative dialectics (Th. Adorno) and they simultaneously feature depictions of Western tools used for the exploitation of the essence of native peoples. In this sense, the artworks in the sample are linked by the recurrence of golden leaves on natural pigments (such as indigo, lace, soil, sand, banana, maize or agave leaves), contrasting the value of the sanctity of colonial times and gold with the profound importance of the sanctity of mother earth for native peoples. This dialectic seeks to highlight and convey to viewers how the advance of colonization has culturally built the values of the Western world.

Los colores con los que trabaja están en la gama de grises, rojos, blanco y dorados. Los grises de las telas interactúan con el gris del aluminio (reciclado) de los objetos escultóricos que cohabitan dentro de la misma exposición. Es un gris que nos lleva a pensar en el cemento y en el plomo de las balas, que son figuradas como forma de maíz. Este juego figurativo, entre bala y maíz, nos transporta a la reflexión sobre el extractivismo, el ecocidio y el genocidio colonial, en donde la bala cobra más significado que el alimento y la propia vida, recordando el maíz como figuración de lo sagrado para los pueblos precolombinos, que se confunde con la figura de la bala; siendo el maíz símbolo de vida, se transfigura estéticamente con la necropolítica de un mundo gris.

De ahí emerge el color púrpura, un tipo de rojo, que indica el significado católico sacro de fidelidad a la Iglesia hasta la muerte y también de la “pasión de Cristo”. Lo encontramos acá señalando la sangre derramada de generaciones de indoamericanos que han defendido las tradiciones que protegen la Pachamama. Asívemos, por ejemplo, en la obra “Pentêkostê hêméra” una flor de lis

His chosen colors include hues of gray, red, white and gold. The grays in the textiles interact with the gray of recycled aluminum of the sculptures that cohabit within the same exhibition. These grays remind us of cement and lead in bullets, which are depicted in the shape of maize. This figurative interplay between maize and bullet leads us to reflect on colonial exploitation, ecocide, and genocide. Bullets thus become more important than this grain or even life itself, as maize, a symbol of sanctity and life for pre-Hispanic peoples, is mistaken for bullets and it is aesthetically transfigured with the necropolitics of a gray world.

Then, a purple hue –a type of red– emerges to allude to the sanctity of Catholicism and undying loyalty to the Church, as well as the “Passion of the Christ” in the spilled blood of generations of native peoples that have defended the traditions to protect Pachamama. An example of this can be found in the piece “Pentêkostê hêméra” depicting an inverted fleur-de-lis

(antiguo símbolo de iluminación) invertida con un fondo gris (aunque no fue pintada intencionalmente). El día de pentecostés en los escritos bíblicos, habla de la recepción del fuego unificador del “Espíritu Santo”, que acá, sin embargo, parece indicar más que al cielo al inframundo de la minería, causante de tanta devastación en América Latina. Las obras pictóricas de esta muestra enfocan desde la abstracción cartografías de territorios colonizados como un recurso simbólico que el artista retoma en diversas obras en su trayectoria.

La mímesis simbólica de las obras escultóricas hacen tener un impulso de confundir estas balas con alimento, que con sus títulos inscriptos en el aluminio configuran su dirección hacia el interior del espectador, como balas de inyección de memoria que traen al corazón el dolor colonial junto a la desacralización de la tierra y de la vida, para recibir a cambio una cruz que penetra nuestra cultura como una espada de hierro. Esta espada completa la constelación mnémica de las heridas abiertas y se hace presente como objeto escultórico que no permite diferenciar si es espada o cruz.

(symbol of enlightenment) on a gray backdrop, although the symbol was not painted intentionally. According to biblical texts, Pentecost is about the coming of uniting fire of the Holy Spirit. In the piece, however, it does not seem to refer to the skies, but rather the underworld of mining, the cause of so much devastation in Latin America. The paintings in the sample are centered around abstract cartographies of colonized territories, a symbolic resource that the artist repeats throughout several pieces in his oeuvre.

The symbolic mimesis in the sculptures tend to make us mistake bullets and foods, and their aluminum engraved titles are directed towards viewers as memory injection bullets that carry the pains of colonization and the desanctification of the earth and life to, in turn, welcome a cross that pierces our culture like an iron sword. This sword completes the symbolic constellation of open wounds and takes on the form of a sculpture that makes it hard to distinguish sword from cross.

De la serie Maiz, “Hijos del sol no del hierro”, 2024, aluminio