Miami Beach Convention Center

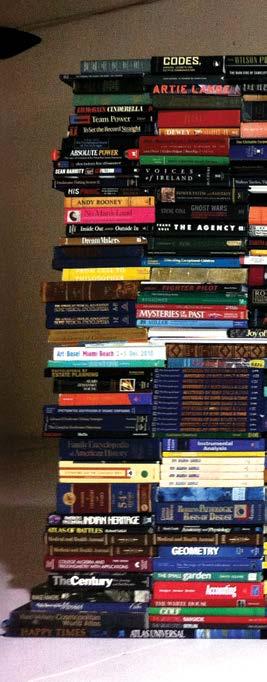

December 5 - 7, 2025

Miami Beach Convention Center

December 5 - 7, 2025

el calendario del mundo del arte inicia la temporada 2026 entre ferias y bienales donde estaremos presentes. Miami, México y Madrid se preparan para sus semanas más intensas, cada una con una escena propia y en plena efervescencia. La semana del arte en Miami se proyecta como un punto de convergencia donde el arte latinoamericano gana cada vez más terreno; mientras que ZONA MACO consolida a México como eje continental; y ARCO Madrid reafirma su papel en Europa. Además, las ferias de Estados Unidos, LA Art Show y Art Palm Beach abren realmente el año, marcando el pulso del mercado internacional entre propuestas experimentales y un coleccionismo cada vez más sofisticado.

En Latinoamérica, las recientes ediciones de ArtBo y Un_Fair —ambas en Bogotá—, junto con ArteBa en Argentina, marcaron la antesala de una temporada diversa y dinámica. En este mismo espíritu, la Bienal de Bogotá se consolidó como un espacio de reflexión sobre los cruces entre arte y comunidad, desplegando una gran logística para hacer partícipe a la ciudadanía del arte contemporáneo.

Sin embargo, en medio de esta efervescencia y los miles de preparativos que acompañan cada feria, surge una pregunta inevitable: ¿qué pasará con la seguridad de las obras? La reciente vulneración del Museo del Louvre —con el robo de las joyas de Napoleón— reactivó las alertas sobre la seguridad patrimonial a nivel global. Si una institución de tal envergadura puede ser vulnerada, se hace evidente la fragilidad de los sistemas de resguardo y la urgente necesidad de revisar las estrategias de protección que sostienen a museos, colecciones y espacios culturales.

Pero volviendo a los eventos de arte, desde el sur del continente, la Bienal de Cuenca emerge como un espacio de pensamiento crítico que dialoga con los desafíos ambientales y sociales de nuestro tiempo. Su enfoque curatorial que entrelaza arte, territorio y memoria, refuerza la importancia del arte como herramienta de reflexión y resistencia en América Latina.

Arte Al Límite participa como medio oficial de la Bienal, reafirmando su compromiso con la difusión del pensamiento artístico regional. Además, hemos publicado entrevistas exclusivas en nuestro sitio web con los 17 curadores asistentes, quienes abordan los desafíos de la práctica curatorial y los nuevos modos de entender el arte contemporáneo en contextos latinoamericanos.

En esta edición ofrecemos una pincelada de esas miradas y procesos: una selección de artistas del continente que, desde diversas estéticas y discursos, nos recuerdan la importancia del arte visual como lenguaje vivo, capaz de cuestionar, transformar y abrir horizontes en tiempos de cambio.

the art world’s calendar for 2026 begins with fairs and biennials in which AAL will take part. Miami, Mexico, and Madrid are gearing up for the most intense weeks, each with its own vibrantly effervescent scene. Miami Art Week is expected to serve as a hub where Latin American art has increasingly gained more ground, while ZONA MACO solidifies Mexico’s position as a continental powerhouse, and ARCO Madrid strengthens its role in Europe. Moreover, the fairs in the States, such as the LA Art Show and Art Palm, will truly kick off the year, setting the tone for the international art market with experimental proposals and increasingly sophisticated art collecting.

In Latin America, recent editions of ArtBo and Un_Fair, both in Bogota, along with ArteBa in Argentina, served as a prelude to a diverse and dynamic season. In the same spirit, the Bogota Biennial was consolidated as a space for reflection on the intersections of art and community, unfolding great logistics to make the citizens active participants in contemporary art.

However, amid this lively scene and the thousands of arrangements that come along with all fairs, an unavoidable question arises: What will happen to the safety of the artworks? The recent Louvre heist, resulting in the theft of jewelry that belonged to Napoleon, raised alarming concerns about the safety of cultural heritage around the world. If an institution of such magnitude can be compromised, the fragility of security systems and the urgent need to review the protection strategies for museums, collections, and cultural spaces become evident.

Returning to art-related events, in the southern part of the American continent, the Cuenca Biennial promises to emerge as a space for critical thinking that reflects on the environmental and social challenges of our time. Its curatorial approach, which brings together art, territory, and memory, reinforces the importance of art as a tool for reflection and resistance in Latin America.

Arte Al Límite will participate as an official media partner of the Biennial, reaffirming its commitment to promoting regional artistic thought. Additionally, we will publish exclusive interviews on our website with the 17 participating curators, who will discuss the challenges of curatorial practice and explore new ways of understanding contemporary art in Latin American contexts.

In this edition, we offer a glimpse of those perspectives and processes, featuring a selection of Latin American artists who, using diverse aesthetics and discourses, remind us of the significance of visual arts as a living language, capable of questioning, transforming, and opening new horizons in changing times.

e n un mundo donde la tecnología redefine la percepción de la identidad, esta exhibición invita a una reflexión profunda sobre la relación entre los rostros humanos, la privacidad y el poder en la era digital. Con el enfoque y la mirada en la colección permanente del Museo Arte Al Límite y enriquecida con la participación de artistas invitados, se propone un diálogo crítico y multifacético a través de obras en pintura, escultura, dibujo, fotografía y video, complementadas con experiencias inmersivas e interactivas.

Desde tiempos históricos, los artistas han trabajado con el rostro casi como un acto premonitorio, manipulando y transformando su imagen para explorar identidad, poder y vulnerabilidad. Desde retratos que cuestionan la apariencia y la percepción hasta obras que anticipan las implicaciones del control visual, estos creadores han sido pioneros en el uso del rostro como medio de expresión y subversión.

i n a world where technology redefines the perception of identity, this exhibition invites a deep reflection on the relationship between human faces, privacy, and power in the digital age. With a focus on and dialogue with the permanent collection of the Museo Arte Al Límite, and enriched by the participation of guest artists, it proposes a critical and multifaceted conversation through works in painting, sculpture, drawing, photography, and video, complemented by immersive and interactive experiences.

Since historical times, artists have worked with the human face almost as a premonitory act—manipulating and transforming its image to explore identity, power, and vulnerability. From portraits that question appearance and perception to works that anticipate the implications of visual control, these creators have been pioneers in using the face as a medium of expression and subversion.

En la actualidad, esta tradición se encuentra en tensión con los avances tecnológicos, que permiten la recopilación y manipulación masiva de datos biométricos, poniendo en riesgo nuestra privacidad y autonomía.

La muestra confronta al espectador con las preguntas esenciales acerca de la autenticidad, la autorepresentación y la vulnerabilidad en un entorno donde los datos biométricos —reconocidos como los identificadores más íntimos y reveladores—, son utilizados tanto para empoderar como para controlar.

Desde los rostros que identifican y delimitan hasta los algoritmos que los interpretan y manipulan, la exhibición revela la ambivalencia del rostro como arma de poder y espejo de nuestra verdadera naturaleza.

La exposición busca estimular la reflexión sobre qué significa una “identidad real” más allá de los marcadores biométricos, invitando al público a cuestionar las implicaciones éticas y sociales de la tecnificación de la identidad.

“El rostro como medio y reflejo”, es una provocación artística y social que busca empoderar a los visitantes para que cuestionen su propia relación con su identidad biométrica, promoviendo un pensamiento crítico sobre el futuro que estamos construyendo en la intersección entre humanidad, tecnología y poder. Y el poder personal de preservar al máximo nuestra privacidad e identidad.

Marisa Caichiolo, curadora.

Today, this tradition is in tension with technological advances that enable the massive collection and manipulation of biometric data, putting our privacy and autonomy at risk.

The exhibition confronts viewers with essential questions about authenticity, self-representation, and vulnerability in an environment where biometric data—recognized as the most intimate and revealing identifiers—are used both to empower and to control.

From faces that identify and define to algorithms that interpret and manipulate them, the exhibition reveals the ambivalence of the face as both a weapon of power and a mirror of our true nature.

The exhibition seeks to stimulate reflection on what a “real identity” means beyond biometric markers, inviting the public to question the ethical and social implications of the technologization of identity.

“The Face as Medium and Reflection” is an artistic and social provocation that aims to empower visitors to question their own relationship with their biometric identity, promoting critical thinking about the future we are building at the intersection of humanity, technology, and power—and about the personal power to preserve, as much as possible, our privacy and identity.

DIRECTORES

Ana María Matthei

Ricardo Duch Marquez

DIRECTOR COMERCIAL

Cristóbal Duch Matthei

DIRECTORA DE ARTE Y EDITORIAL LIBROS

Catalina Papic

PROYECTOS CULTURALES

Camila Duch Matthei

EDITORA

Elisa Massardo

DISEÑO GRÁFICO

María Nestler

CORRECCIÓN DE TEXTOS

Javiera Fernández

ASESORES

Benjamín Duch Matthei

Ricardo Duch Matthei

Milagros Duch Matthei

Felipe Duch Matthei

REPRESENTANTES INTERNACIONALES

Julio Sapollnik (Argentina)

REPRESENTANTE LEGAL

Orlando Calderón

TRADUCCIÓN

Adriana Cruz

SUSCRIPCIONES

info@arteallimite.com

IMPRESIÓN

A Impresores

DIRECCIONES

Chile / Francisco Noguera 217 oficina 30, Providencia, Santiago de Chile. www.arteallimite.com

PORTADA

Love shines so bright (Jorge), 2025, óleo sobre tela, 134 x 134 cm.

CONTRAPORTADA

Roberto Mardones, 2025, vista Museo Arte Al Límite.

VENTA PUBLICIDAD +56 9 99911933. info@arteallimite.com marketing@arteallimite.com

Derechos reservados

Publicaciones Arte Al Límite Ltda.

España | Spain

Por Julio Sapollnik. Crítico de Arte (Argentina)

Imágen cortesía del artista.

Representado por Gaelerie BHAK.

n 2024, el Centre Pompidou-Metz presentó la exposición “Lacan, cuando el arte se encuentra con el psicoanálisis”, conmemorando cuatro décadas de la muerte de Jacques Lacan. La muestra se propuso reinscribir la potencia de su pensamiento en el campo estético, evidenciando cómo sus conceptualizaciones sobre la mirada, el deseo y el objeto pueden operar como marcos de lectura de las prácticas artísticas contemporáneas.

Lacan mantuvo una relación estrecha con el arte de su tiempo y al mismo tiempo, elaboró una reflexión que desbordó los límites cronológicos del siglo XX. Su aproximación a las obras no se redujo a la descripción iconográfica ni al análisis formal: introdujo un giro conceptual que situó a la obra de arte como un dispositivo activo, capaz de interpelar al sujeto espectador. Como expresó en sus seminarios: No es el ojo del contemplador el que se dirige a la obra de arte, sino que es la obra de arte la que atrae la mirada del contemplador. En esta formulación se condensa una de las operaciones más fecundas de su pensamiento: desplazar el eje de la experiencia estética desde la intencionalidad del sujeto hacia la agencia del objeto.

Esta perspectiva ofrece un marco especialmente fértil para aproximarse a la obra de Salustiano García, cuya poética visual parece materializar con precisión ese diálogo silencioso.

Las imágenes de Salustiano se caracterizan por un equilibrio perturbador entre belleza formal y tensión afectiva. Las figuras, aisladas sobre fondos monocromáticos intensos, revelan una interioridad que no se enuncia explícitamente, pero que se impone con fuerza a la mirada del espectador. Esta potencia expresiva está indisolublemente ligada a un proceso técnico riguroso: el característico fondo rojizo de sus obras proviene de la aplicación sucesiva de más de cuarenta capas de pintura. Esta construcción técnica no solo genera profundidad visual, sino también densidad simbólica, otorgando a la superficie pictórica un espesor temporal que remite a la lenta sedimentación de un afecto.

i n 2024, the Centre Pompidou-Metz hosted the exhibition “Lacan: When Art Meets Psychoanalysis” to commemorate four decades since Jacques Lacan’s death. The exhibition aimed to reaffirm the significance of Lacan’s ideas in the realm of aesthetics, illustrating how his concepts of the gaze, desire, and the object can serve as a framework for interpreting contemporary art practices.

Lacan had a deep relationship with the art of his time, and his ideas about it have transcended the constraints of 20th-century history. His approach to artwork went beyond simple iconographic descriptions or formal analyses. Instead, he introduced a conceptual shift that positioned art as an active device capable of challenging viewers. In his seminars on the gaze, Lacan argued that it is not simply the eye of the beholder that turns toward the work of art; rather, the artwork itself has the power to draw and structure the beholder’s gaze. This formulation summarizes one of the most fertile insights of his postulates: shifting the focus of aesthetic experience from the subject’s intentional act to the agency of the object.

This perspective provides a particularly effective framework for analyzing Salustiano García’s work, in which his visual poetry seems to embody this silent conversation.

Salustiano’s images are notable for their unsettling balance between formal beauty and emotional tension. The figures, set against bold monochromatic backgrounds, expose an inner world that does not overtly pronounce itself, but firmly compels the viewers’ gaze. Such expressive power is inextricably tied to a rigorous technical process. His signature reddish backgrounds are created through the successive application of over forty layers of paint. His technical construction not only generates visual depth, but also symbolic density, giving the pictorial surface a temporal thickness that evokes the gradual settling of an emotion.

Love is pop (Zahara con kimono y pistola), 2024, óleo sobre tela, 138 x 138 cm.

Para Salustiano, el rojo no es simplemente un color: “es la metáfora visible de la energía vital. Es el color del cuerpo, del calor, de la respiración. Cuando lo aplico sobre el lienzo no pienso en una simbología abstracta, sino en algo profundamente físico: en la piel iluminada por dentro, en la vibración que hay antes del movimiento, en el temblor que antecede al gesto. Es un color que respira y que hace respirar a quien lo mira. Por eso no lo uso como fondo, sino como atmósfera: el espacio donde la figura vive, donde la carne y la piel tienen un sentido concreto. En español decimos rojo o colorado, y ambas palabras provienen del latín coloratus, de colorare, ‘dar color’. En cierto modo, el rojo encarna el acto mismo de pintar: el instante en que la materia cobra forma”.

Podemos imaginar que este “nuevo colorado” surge del blanco pleno de la tela o de la superposición de panes de oro: una asociación libre que sugiere la transmisión vital que simboliza “el ardor, la belleza, la fuerza impulsiva y el eros libre y brillante”, como señalan Jean Chevalier y Alain Gheerbrant.

Uno de los elementos recurrentes en su pintura es la presencia del círculo, símbolo que desde la antigüedad ha estado asociado con la necesidad de amparo. El círculo protector ha adoptado la forma de sortijas, brazaletes, collares, cinturones o coronas; objetos que, más allá de su dimensión ornamental, actuaban como estabilizadores que mantenían la cohesión entre el alma y el cuerpo. Salustiano define esta forma de manera poética: “una línea que se repliega sobre sí misma hasta encontrarse. No hay límite, sino plenitud; no encierra, sino que contiene y acoge. Es la manifestación de una armonía que se renueva sin cesar, la expresión de un optimismo profundo y silencioso”.

Y agrega: “cuando este formato comenzó a aparecer en mi obra, coincidió —y no por casualidad— con el nacimiento de mi hijo Horacio. Comprendí entonces que aquella forma perfecta se había revelado también en mi vida: la línea de mi existencia, tras un largo recorrido, parecía unirse por fin consigo misma. Entendí que tanto el arte como la vida se miden por su capacidad de contener amor, una forma verdaderamente perfecta donde se integran la emoción y el orden”.

Cuando trabaja con la temática floral, Salustiano se distancia deliberadamente de su carga simbólica tradicional: “Las flores que represento poseen una textura mineral, casi petrificada. Son como plantas

For Salustiano, red is not merely a color, it is a “visible metaphor for vital energy. It is the color of the body, heat, and breathing. When I apply [red] on a canvas, I am not thinking of an abstract symbolism, but something profoundly physical: skin lit from within, the vibration that comes before movement, the tremor that precedes a gesture. It is a color that breathes and makes everyone who see it breathe as well. Therefore, I do not use it as a background; I use it as an atmosphere—the space where figures live, where skin and flesh hold specific meaning. In Spanish, we say rojo [red] or colorado [lit. ‘colored’, often used to describe red tones]. Colorado comes from Latin coloratus, the participle of colorare, meaning ‘to give color’. So, in a way, red embodies the act of painting, the moment that matter takes shape.”

We can imagine that this ‘new red’ emerges from the pure white of the canvas or from the overlapping layers of gold leaf. This free association suggests a vital transmission that symbolizes ‘ardor, beauty, life force, and free and brilliant eros’ as Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrant would argue.

A recurring element in his paintings is the presence of circles, which have been associated with the need for protection since ancient times. Protective circles take the forms of rings, bracelets, necklaces, belts, and crowns, objects that, beyond their ornamental value, serve as stabilizers to maintain the cohesion between body and soul. Salustiano has a poetic definition for this shape: “A line that folds back on itself until it meets. There is no limit, only fullness; it does not enclose, but rather contains and welcomes. It is the manifestation of an ever-renewing harmony, the expression of a deep and silent optimism.”

He further adds: “When this format began to appear in my work, it coincided—and not by chance—with the birth of my son, Horacio. I realized then that this perfect shape had also revealed itself in my life: the line of my existence, after a long journey, seemed to finally come together. I understood that both art and life are measured by their ability to contain love, a truly perfect form where emotion and order are integrated.”

When he works with floral motifs, Salustiano deliberately departs from their traditional symbolic meaning: “The flowers I represent have an almost petrified mineral texture. They are like prehistoric

prehistóricas detenidas en el tiempo, que buscan perpetuarse más allá de la vida orgánica. En ellas hay una voluntad de eternidad silenciosa, la misma que habita en los rostros tallados de la Isla de Pascua, en las esfinges egipcias o en un insecto inmovilizado dentro de una gota de ámbar”. El artista detiene en la imagen una apariencia de eternidad que él define: “como si no pasara el tiempo”.

En otras obras, la figura de una adolescente empuñando un arma tensiona el campo interpretativo. Una lectura superficial podría proyectar violencia o amenaza. Sin embargo, el gesto pictórico no busca clausurar el sentido ubicándose como espejo iconográfico, sino abrir un espacio de connotaciones inquietantes. No se trata de un significado unívoco, sino de la presentación de un instante suspendido, un “significante cero”: algo que ha ocurrido o que está por ocurrir.

Esta potencia expresiva se refuerza con la elección de modelos únicos, en contraposición a la tradición de retratos colectivos encarnada en obras paradigmáticas como La familia de Carlos IV de Francisco de Goya o Las Meninas de Diego Velázquez. La unicidad del modelo intensifica la escena de interpelación: frente a la figura, el espectador carece de mediaciones y se enfrenta directamente a la mirada de la obra. El resultado no es una relación empática ni narrativa, sino un encuentro asimétrico en el que el sujeto queda, en cierta medida, desposeído de su posición dominante para permitir que la imagen inscriba emociones con una nueva caligrafía interior.

Desde esta perspectiva, la pintura de Salustiano puede entenderse como un espacio privilegiado para explorar la eficacia estética de la mirada. La obra no es objeto de contemplación pasiva, sino agente de un acontecimiento subjetivo. Su potencia no reside únicamente en la destreza técnica ni en la belleza formal, sino en su capacidad de instalar una escena en la que el espectador se ve implicado como partícipe involuntario.

En tiempos en que la imagen circula a gran velocidad y se consume en la inmediatez, la pintura de Salustiano propone un gesto radical: detener, intensificar y devolver la mirada. Como formuló Lacan, no somos nosotros quienes observamos la imagen: es ella quien —desde su silencio cargado de tiempo y deseo— nos observa y nos constituye.

plants frozen in time, seeking to hold on beyond organic life. In them, there is a desire for silent eternity, the same that dwells in the carved faces of Easter Island, in the Egyptian sphinxes, or in an insect immobilized inside a drop of amber.” The artist captures in the image an appearance of eternity that he defines as: “as if time were not passing.”

In other works, the figure of a teenage girl wielding a weapon creates tension in the interpretive field. A superficial reading could intuit violence or threat. However, the depiction does not seek to constrain meaning by acting as an iconographic mirror. Instead, it aims to open up a space filled with unsettling connotations. It is not a matter of presenting a single meaning, but rather a suspended moment, a ‘zero signifier’ that suggests something has happened or is about to happen.

This expressive power is enhanced by the choice of unique models, contrasting with the tradition of group portraits found in iconic works such as The Family of Charles IV by Francisco de Goya or Las Meninas by Diego Velázquez. The uniqueness of the model heightens engagement with the scene: confronted by the figure, the viewer lacks mediation and is directly confronted by the gaze of the piece. The result is not an empathetic or narrative relationship, but an asymmetrical encounter in which the subject is, to a certain extent, dispossessed of their dominant position. This shift allows the image to convey emotions with a new inner expressiveness.

From this perspective, Salustiano’s painting can be understood as a privileged space for exploring the aesthetic effectiveness of the gaze. Artwork is not an object of passive contemplation, but rather the agent of a subjective event. Its power lies not only in technical skill or formal beauty, but in its ability to create a scene in which the viewer is involved as an unwitting participant.

In times when images circulate at a high speed and are immediately consumed, Salustiano’s painting proposes a radical gesture: to pause, intensify, and return the gaze. s Lacan would put it, it is not we who observe the image: it is the image that—from its silence laden with time and desire—observes us and constitutes us.

EE.UU. | USA

Por Nicole Ahumada. Lic. en Artes Visuales (Chile)

Imágenes cortesía de la artista.

Represantada por Normal Royal.

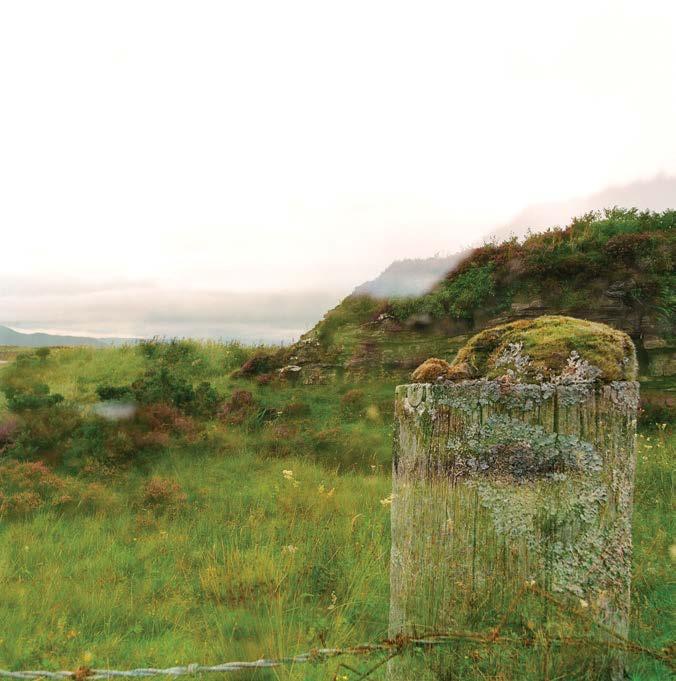

l a artista y terapeuta Deanna Miesch explora en su obra fotográfica la memoria, la percepción y el tiempo a través de la superposición de imágenes.

Su práctica, enraizada en la intuición y el riesgo, vincula el gesto artístico con la experiencia terapéutica, revelando una mirada que concibe la fotografía como un espacio de tránsito entre el cuerpo, la emoción y la imagen. En esta conversación, Miesch reflexiona sobre la dimensión simbólica del error, la relación entre técnica y azar, y la forma en que la práctica artística y la clínica se entrelazan en una misma búsqueda de sentido y presencia.

¿Qué rol simbólico tiene la figura de la superposición fotográfica en tus temáticas?

Las exposiciones múltiples a menudo permiten que me haga una idea más clara de un lugar o de un individuo. Se sienten más como memorias o el proceso de recordar, similar a los sueños. Pueden sentirse como portales, ventanas que no podemos ver, pero quizás sí sentir. Claro está que en una fotografía de exposición simple se detiene el tiempo. En cambio, las exposiciones múltiples parecen más bien revelar el tiempo. Me hacen sentir más. Solía dedicarme a la fotografía urbana, pero después de leer un artículo sobre la creencia de las tribus de nativos estadounidenses de que una fotografía puede robar una parte del alma, empecé a alejarme de esa práctica. En los últimos veinte años, me he centrado más en los paisajes, pero también abordo otros temas, dependiendo de dónde me encuentre. Los retratos dentro de un paisaje—literalmente dentro de un paisaje gracias al uso de las exposiciones múltiples— dan la sensación de que una persona ha absorbido un lugar, o viceversa. Los lugares históricos me entusiasman y, aunque a veces fantaseo con tener el lugar para mí sola, muchas veces disfruto que haya gente en esos espacios. Creo que este tipo de imágenes en particular se asemejan a cómo me imagino que se siente viajar en el tiempo.

artist and therapist Deanna Miesch explores memory, perception, and time in her work through overlapping images.

Her practice—rooted in intuition and risk—ties artistic gestures to therapeutic experiences, revealing a perspective that regards photography as a transitory space between the body, emotions and images. In this conversation, Miesch reflects on the symbolic meaning of mistakes, the relationship between technique and randomness, and how artistic and technical practices intertwine in the pursuit of meaning and presence.

What symbolic role does the figure of photographic superposition play within your themes?

Multiple exposures often give me a better sense of a place, or a person. They feel more like memory, the process of remembering, akin to dreams. They can feel like portals, windows we can’t see, but may feel. A single exposure photograph, of course, stops time. Multiple exposures seem to reveal time itself. They make me feel more.

I used to do street photography but after reading an article that discussed the Native American view that a photograph can steal a part of one’s soul, I began to pull back. I have focused more on landscape in the last twenty or so years, but other subjects come into play, depending on where I am.

Portraits within a landscape—literally within a landscape in multiple exposures—feel like a person has absorbed a place, or vice versa. Historic places are exciting to me, and while I may fantasize about having a place all to myself, I often enjoy having people in the spaces as well. Those sorts of images, in particular, can feel like what I imagine time travel might be like.

¿Cómo abordas la selección de lo que consideras “fotografiable”?

¿Hasta qué punto te importa el procedimiento técnico o tecnológico que acompaña a esta decisión?

Una de las cosas sobre el uso de la película fotográfica es que es cara y, por ende, se siente más valiosa. Con una cámara de formato medio (una Hasselblad 500C/M durante las últimas dos décadas), estoy limitada a solo 12 exposiciones. Es decir, realmente tengo que querer tomar una foto. La cámara es pesada y voluminosa, tengo que sacarla del bolso. Cualquiera que esté conmigo tiene que tenerme mucha paciencia, ya que hay muchos factores que juegan en mi contra. Así que espero hasta que mi voz interna me hable lo suficientemente fuerte como para superar esos obstáculos. Puede ser que traiga mi cámara, pero eso no necesariamente significa que la vaya a sacar del bolso. A veces, incluso los lugares más bonitos no ameritan ni una sola foto.

Hace poco comencé a fotografiar con una cámara panorámica Linhof Technorama 617S III, una cámara preciosa, tan solo un poco más pesada que mi Hasselblad, aunque es más grande. También utiliza película de formato medio o 120 mm, pero cada foto equivale a tres fotos en una cámara de formato medio. Por lo tanto, estoy limitada a cuatro fotos. Estoy increíblemente entusiasmada con esta cámara, pero también tiene sus limitaciones. Una de las ventajas es que a menudo puedo terminar un rollo de una sola vez. Eso significa que es menos probable que olvide qué tipo de película hay en la cámara. Puedo hacer unas cuantas fotos y luego cambiar el rollo de color a uno blanco y negro, o cambiar fácilmente el ISO de la película.

Siempre me ha gustado la idea del “panorama global”, utilizando la misma horizontalidad elongada de las pinturas. Poder conseguir esto en fotografía es emocionante. Además, puedo hacer tantas exposiciones dobles como quiera, simplemente eligiendo no avanzar. La Hasselblad requiere más esfuerzo: hay que colocar una placa obturadora, quitar la parte trasera de la cámara, avanzar, todo para engañar a la cámara.

En términos generales, ¿cuál es el principio rector que subyace a tus obras?

Quiero que el espectador pueda vislumbrar otro mundo, que se detenga y se esfuerce un poco. Quiero que sienta y que experimente, aunque sea solo un poco, lo que yo experimento.

La fotografía análoga requiere más esfuerzo y dinero, pero me recompensa mucho más. Hay más de mi mano en el proceso. A veces la gente se pregunta por qué no utilizo la fotografía digital y, sin duda, podría conseguir resultados similares. Supongo que parte del atractivo reside en el hecho de que creo un objeto, un objeto mágico. Para mí, tiene más esencia de vida y deseo de vivir.

How do you approach the choice of what is ‘photographable’? To what extent is the technical or technological procedure that accompanies this decision important to you?

One thing about using film is that it’s expensive so it feels more precious. With a medium format camera (for the last two decades it’s been a Hasselblad 500C/M), I am limited to 12 exposures. I really have to want to take a picture. The camera is heavy and bulky, I have to take it out of the camera bag. Anyone I may be with has to have a great deal of patience with me. There are all these elements playing against me, so I wait until the voice inside me is strong enough to overpower those elements. I’ll carry my camera, but that doesn’t mean it’s coming out of the bag. Even quite lovely places won’t necessarily warrant a single shot.

I recently began shooting with a Linhof Technorama 617S III Panoramic camera. It’s the most beautiful camera, and only slightly heavier than my Hasselblad, though it is bigger. It also uses medium format or 120 mm film, but each shot is the equivalent of three shots on a medium format camera. So, I am limited to 4 shots. I am incredibly excited by this camera, but it has limitations as well. One of the perks is that I can often finish a roll in one sitting. That means I’m less likely to forget what kind of film is in the camera. I can take a few shots, and then switch from color to black and white, or change film speeds easily.

I have always been into the idea of “the big picture”, using the wide, elongated formats in painting. Being able to achieve this in film is thrilling. I can also take as many double exposures as I like, simply by not advancing. The Hasselblad requires more effort—putting in a film slide, removing the back of the camera, advancing, all to trick the camera.

Broadly speaking, what is the main guiding principle behind your pieces?

I want the viewer to get a glimpse of another world, I want the viewer to slow down and work a bit. I want the viewer to feel, and I want them to experience even a little bit of what I experience. Analog photography takes more effort and expense, but it gives me so much more reward. There is more of my hand in the process. Sometimes people are confused why I don’t shoot digitally, and, certainly, I could achieve similar results. I suppose part of the lure is the fact I am creating an object, a magical object. It has more essence of life and living to me.

Teniendo en cuenta las otras disciplinas en las que participas, ¿cómo se relaciona la práctica terapéutica con las claves visuales que sustentan tus composiciones? Me he centrado en la resolución de traumas de una forma u otra durante treinta años: arteterapia, EMDR (desensibilización y reprocesamiento por movimientos oculares) y CRM (modelo integral de recursos). En la última década he utilizado CRM en lugar de EMDR, ya que considero que es más fácil de aplicar para mis clientes y más eficaz y eficiente. El CRM es más intuitivo y resuena mejor con mi enfoque hacia el arte y la arteterapia como procesos intuitivos. Creo que una buena terapia ayuda a las personas a aprender a escucharse a sí mismas, a escuchar su instinto, a distinguir entre la voz de la sociedad o la familia y la propia voz. Asumir riesgos suele ser parte del proceso y de la creación artística. Es una forma de dejarse llevar, jugársela, dejar una huella, arriesgarse. La fotografía análoga acepta tanto la perfección como la imperfección, la causa o el efecto, la naturaleza versus la crianza como parte de las experiencias de vida. He aprendido mucho de mi práctica de arteterapia y de mi práctica artística. Hay belleza y beneficios en el difícil trabajo de asumir riesgos emocionales y artísticos. Quiero que el espectador experimente algo del riesgo, la liberación, la aceptación y la alegría de mi práctica artística. En la fotografía análoga, al menos para mí, siempre hay un riesgo. Con las exposiciones múltiples intento que el espectador vea más. El trauma limita la perspectiva; literalmente te da una visión de túnel. No puedes ver el “panorama general”. O me siento mal o me siento bien; no hay término medio. Los modelos de procesamiento del trauma te ayudan a conectar con tu cuerpo para que puedas sentir todas tus emociones. Ayudan a aceptar la paradoja y realmente te dan una perspectiva más amplia. Exteriorizan lo que ocurre en tu interior. Es muy difícil sentirte centrado cuando tu mente no para de dar vueltas. Los seres humanos somos criaturas complejas, somos falibles. No podemos evitar el dolor: ocurrió, sigue y seguirá ocurriendo, pero no tiene por qué definir quiénes somos. Somos un todo, somos todas las partes. Trabajo con muchos medios y cada uno de ellos parece llevarme en una nueva dirección. Es otra capa de quién soy, nunca he sido de las que se quedan con una sola cosa. Ensamblaje, escultura de bronce, escultura de cerámica, collage, dibujo, fieltro, pintura, fotografía. Trabajo con lo que me apetece. Crear arte me mantiene cuerda, lo cual es claramente importante si quiero ayudar a los demás. Es importante que practique lo que predico. Escucharme a mí misma, a mi instinto, es fundamental. Encontrar formas de soltar el control, salir de mi cabeza, ser libre en mi vida, todo esto me ayuda a funcionar en el mundo, a funcionar en la sociedad y también es lo que hace que el arte sea bueno. Es un ciclo, uno alimenta al otro. Siempre que he cometido un error en mi vida ha sido inevitablemente porque no me he escuchado a mí misma, he dudado. Así que cuando pienso en sacar la cámara del bolso, lo hago.

Considering the other disciplines you’re involved in, how does therapeutic practice connect with the visual cues that sustain your compositions? I have focused on trauma resolution in one way or another for thirty years: art therapy, EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization Reprocessing), and CRM (Comprehensive Resource Model). I’ve used CRM versus EMDR in the last decade as I feel it is both easier for my clients to do and it’s more effcient and effective. CRM is more intuitive and resonates more with my approach to art making and art therapy as intuitive processes. I believe good therapy helps people to learn to listen to themselves, listen to their gut, distinguish between a societal or familial voice and one’s own voice. Risk taking is often a part of art making, and art processes. It’s a way of letting go, rolling the dice, making a mark, taking a shot. Film accepts perfection or imperfection, cause or effect, nature or nurture as part of the experience of living. I have learned a great deal from my art therapy practice and artistic practice. There is beauty and benefit in the diffcult work of emotional risk and artistic risk taking. I want the viewer to experience some of the risk, release, acceptance and joy in my artistic practice. In analog photography, at least for me, there’s always a risk. With multiple exposures, I’m trying to get the viewer to see more. Trauma limits one’s perspective; it literally gives you tunnel vision. You can’t see the “big picture.” It’s either, I feel bad, or I feel good; there’s no middle ground.

Trauma processing models help you to get in your body so you can feel your feelings—all of them. They help you to accept the paradox, they literally give you perspective. You are externalizing what’s happening inside. It’s really hard to feel grounded when your head is reeling. We are complex creatures, humans. We are fallible. We can’t avoid pain: it’s happened, it’s happening, and it will happen, but it doesn’t have to define who we are. We are all of it, we are all the parts.

I work with many mediums, and each one seems to take me in a new direction. It’s another layer of who I am. I’ve never been one to stick with one thing. Assemblage, bronze sculpture, ceramic sculpture, collage, drawing, felting, painting, photography, I’ll work with whatever I feel like. Art making keeps me sane, which is clearly important if I want to help others. It’s important that I practice what I preach. Listening to myself, my gut, is crucial. Finding ways to let go of controls, get out of my head, be free in my life, all of this helps me to function in the world, function in society, and it is also what makes good art. It’s a cycle, one feeding the other.

Whenever I have made an error in my life it has inevitably been when I didn’t listen to myself. I second guessed myself. So when I think, take the camera out of the bag, I do.

Inglaterra | England

Por Elisa Massardo. Lic. en Historia y Estética (Chile)

Imágenes cortesía del artista.

Representado por Normal Royal.

“Quiero que los espectadores se detengan a contemplar más de cerca”

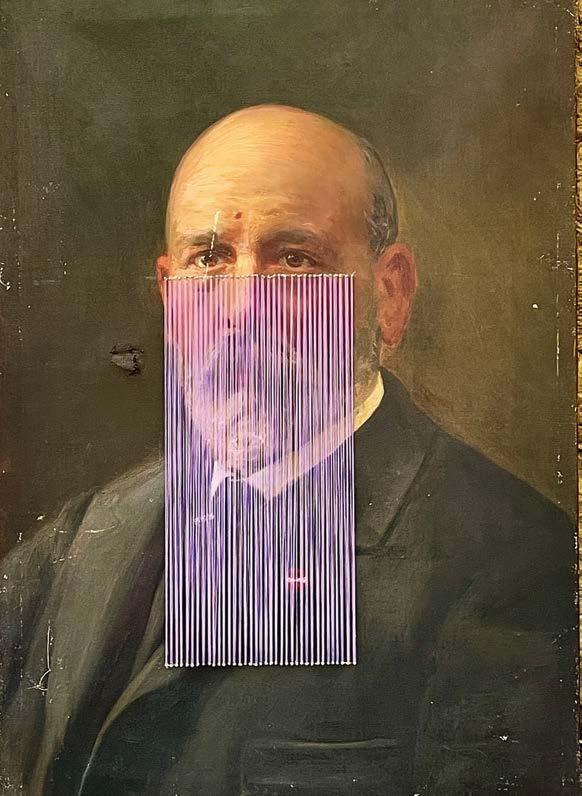

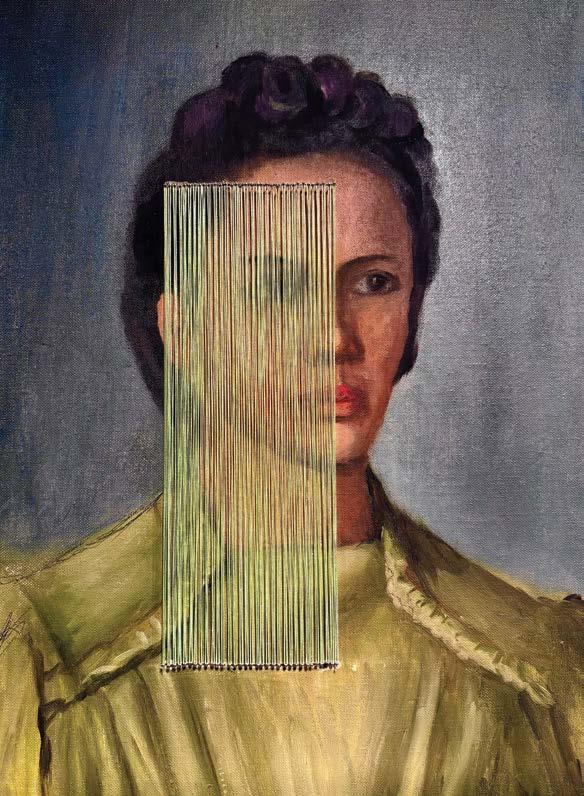

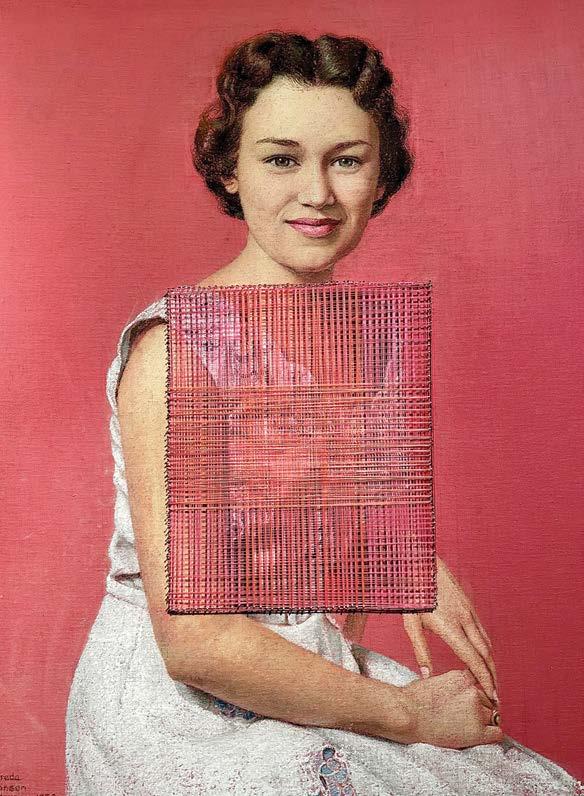

anivel familiar no existen recuerdos sobre la primera persona que empezó a trabajar con ropas y cestas, siempre creadas en forma artesanal, con el cuidado y el tiempo que amerita cada pieza. En este entorno creció Samir Faris, con una herencia cultural proveniente del Líbano e Inglaterra. Así, a pesar de haber estudiado Historia, para el artista la creación manual era algo inevitable y este conocimiento técnico lo fue mezclando con una reinterpretación del lenguaje visual del arte, ya sea a través de pinturas, dibujos y objetos de arte. “Me interesa más el componente espiritual de lo que observo. No pretendo que mis obras tengan un énfasis político o conceptual. Me interesa mucho más la estética”.

En sus obras, el uso de la perspectiva es fundamental, la variación de la imagen de acuerdo al lugar desde donde la mires; el manejo de los hilos; la imaginación alterada por el movimiento. Trabaja con paisajes, pero también con retratos y diversos elementos que van demostrando este interés por la armonía del color, la intensidad de la mirada y la potencia que se obtiene de las técnicas mixtas.

En Ambient Scapes, hay tensión entre la naturaleza tangible del hilo y la inmaterialidad de la imagen. ¿Qué te interesa explorar en esta dualidad entre lo físico y perceptual?

Cuando alguien observa mis obras, quiero que tenga una experiencia 3D, en vez de solo una 2D. Quiero que la percepción de mi arte cambie a medida que el espectador se mueva en la sala. Me fascina cómo funciona la perspectiva. Al trabajar con hilos físicos, puedo hacer que la imagen se levante del papel; puedo hacer que luzca como si flotara.

Esta idea de la perspectiva, ¿cómo se incorpora dentro de la dimensión performativa del proceso creativo?

En definitiva, la percepción lo es todo para mí y para mi obra. A medida que el espectador se mueve en la sala, quiero que vea cómo cambia la imagen en función de la perspectiva. Desde distintos ángulos, la imagen puede parecer un fantasmagórica o un bloque sólido. Además, la forma en la que creo capas con diversos hilos de algodón hace que la imagen cambie de color o tono según la posición. Quiero que las imágenes cambien de aspecto físico cuando el ángulo cambie porque me parece que las hace cobrar vida.

¿Qué relación estableces entre tus obras y la tradición de pintar paisajes? ¿Crees que tu obra dialoga o reinterpreta ese género desde otra perspectiva?

Creo que constantemente dialogo con los paisajistas del pasado. También creo que modernizo ese lenguaje visual, tal como mi lengua hablada se relaciona con un idioma antiguo, pero lo actualiza. Este es un componente importante de la historia del arte: trabajar con las tradiciones y métodos del pasado y buscar brindarles una nueva dirección. Respeto mucho a los artistas del pasado. Y, cuando es posible, incorporo obras físicas mediante imágenes antiguas, como en mi serie titulada Portrait Structures.

La descripción de tu trabajo menciona la influencia del impresionismo y el campo del color. ¿Cómo interactúan esas referencias históricas con tu propio material y lenguaje contemporáneo?

¿Puedes creer que los impresionistas franceses emergieron hace aproximadamente 150 años? Hoy en día, los impresionistas franceses y su obra constituyen lo que yo denomino un “destino turístico”. Sin embargo, cuando ganaron protagonismo hace muchos años, eran bastante radicales con sus métodos y conceptos. Representaron un cambio extraordinario en la historia del arte.

“I want my viewers to stop and take a closer look”

i n his family, no one remembers who began working with tapestry looms and basket weaving, crafts that have always been made artisanally, with the care and time each piece deserves. Samir Faris grew up in this environment, rich in cultural heritage from both Lebanon and the UK. Despite studying history, the artist feels an unavoidable connection to manual crafts. He has merged this technical know-how with reinterpretations of art’s visual language through painting, drawing, and the creation of art objects. “I am more interested in the spiritual element of anything I look at. I do not intend for my artwork to have any political or conceptual emphasis. I am much more interested in aesthetics.”

In his works, shifting viewpoints are fundamental, as images change depending on the angle and the way he manipulates the threads, transforming imagination through movement. He works with landscapes and portraits, incorporating elements that evince his fascination with harmony and color, with the intensity of perspective, and the depth that can only be achieved through mixed media.

In Ambient Scapes, there is a tension between the tangible nature of the thread and the immateriality of the image. What interests you about exploring this duality between the physical and the perceptual? When someone looks at my artworks, I want them to have an experience that is associated with the 3D rather than only the 2D. I want the perception of my art to change as the viewer moves around the room. I am very interested in the idea of how perspective works. By working with the physical threads, I can raise the image away from the paper; I can make the image look as if it is floating.

How does this idea of perspective fuse into the performative dimension of your creative process?

Of course, perception is everything to me and my artwork. As the viewer moves around the room, I want them to see how the image changes with the perspective. From different viewpoints, the image can appear as if it is ghostlike in one position and from another position it can appear to be a solid block. Also, the way that I create layers using various cotton threads will change the color or tone depending on the viewpoint. I want the image to physically change as the viewpoint changes. I believe that it makes the image alive.

What relationship do you establish between your pieces and the tradition of landscape paintings? Do you feel your work dialogues with or reinterprets that genre from another perspective?

I believe that I am constantly dialoguing with the landscape artists from the past. I also believe that I am modernizing that visual language also, just as my spoken language relates to the language of the past, but updates it. That is an important component to Art History: to work through the traditions and methods of the past and look for new directions. I have much respect for the artists of the past. And, whenever possible, I actually incorporate the physical artworks by using vintage and antique images in my series Portrait Structures.

The description of your work mentions the influence of impressionism and color field painting. How do these historical references interact with your own material and contemporary language?

Can you believe that the French Impressionists first came to attention approximately 150 years ago? Today, the French Impressionists, and their artworks, are largely what I call a ‘tourist destination’. However, when they first came to prominence all those years ago, they were quite radical with their methods and concepts. They really represented an extraordinary change in the history of art.

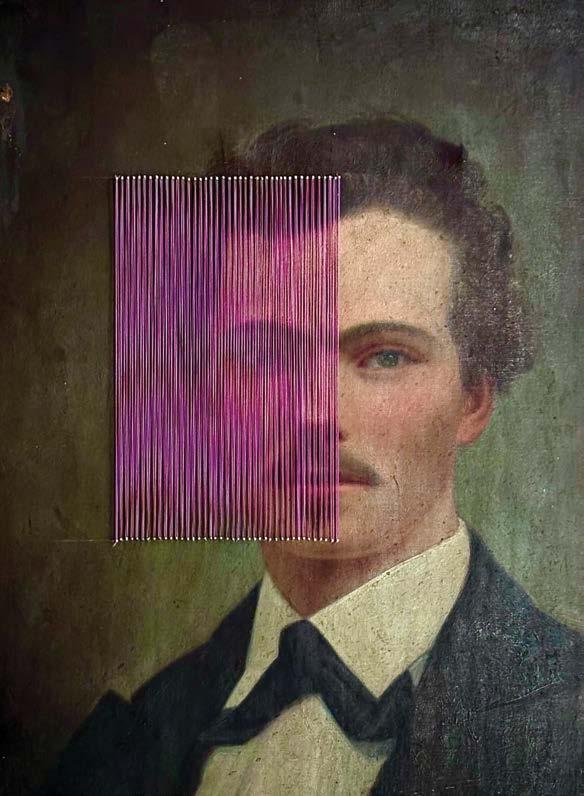

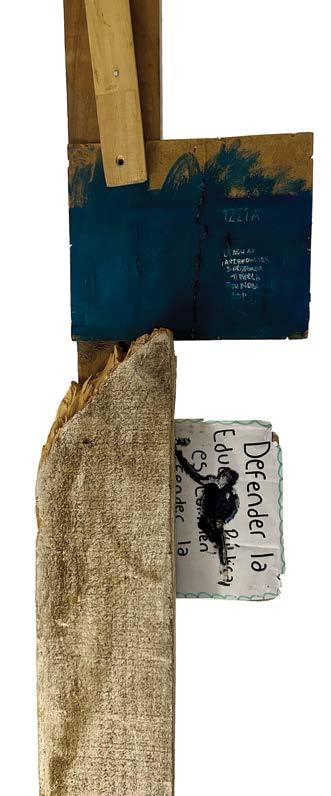

The Melancholy Gent , 2025, técnica mixta, objeto encontrado, hilo y aguja, 38 x50 cm.

El movimiento impresionista se caracterizó por trazos visibles, el énfasis en los cambios de luz en sus representaciones y la convergencia de diversos puntos de vista, solo por mencionar algunas de las cosas que alteraron con la nueva dirección que propusieron. En particular, me interesaba centrarme en cómo creaban una crudeza visual al hacer que sus trazos se tornaran evidentes a la vista. Sin embargo, también introdujeron una forma nueva de representar efectos visuales y tonales con capas de colores. Por primera vez, el público general podía ver cómo el color y el tono se construía gradualmente ante ellos. La magia de la contemplación se desarrollaba paso a paso, frente a sus ojos. Evidentemente, quería encontrar una manera de interpretar esa habilidad que desarrollaron los impresionistas. Por ello, si un espectador promedio contempla mis obras en persona, se puede dar cuenta de que no uso un solo color para crear un efecto. Tal como los impresionistas, agrego hilos en capas, de forma tal que creo una nueva estética de color, incluso trabajando con colores contrarios. Por ejemplo, para lograr un tono de verde específico, superpongo capas de hilos cafés, amarillos y azules, ya que combinándolos puedo obtener el verde que busco. Luego, dependiendo del punto de vista, ese verde puede lucir más azulado o café según el ángulo. De esta forma, puedo emular el mismo efecto visual en mis obras que los pintores impresionistas franceses descubrieron hace muchos años. Me parece que ese tipo de concepto es muy interesante. No pretendo ser tan talentoso como los impresionistas famosos, pero me enorgullece haber encontrado una forma de introducir la superposición de hilos de colores de la misma manera en que estos artistas de antaño superpusieron capas de pintura.

¿En qué punto decidiste incorporar cuerpos y rostros en tus obras y por qué se produjo este cambio?

Como soy un gran aficionado de la historia del arte, naturalmente tiendo a buscar y coleccionar pinturas y dibujos antiguos, así como fotografías de otras épocas. Llamo a estas obras “fantasmas”, y algunas veces me hablan de una forma especial y me tienden un puente de contacto con épocas lejanas. Empecé a incorporar algunas de estas imágenes en mi obra hace unos seis o siete años. Me emociona trabajar con antigüedades y objetos antiguos para reinterpretar ese lenguaje visual. Sin embargo, no todas la imágenes antiguas se pueden reinterpretar de esta forma. He arruinado algunas intentándolo, pero de momento los éxitos superan con creces los fracasos.

¿Crees que el bordado mejora o anula la existencia del cuerpo en tu obra?

En Portrait Structures, busco crear una especie de velo estético. Quiero que los espectadores se detengan a contemplar más de cerca. En ese sentido, creo que estoy mejorando los retratos. No busco anular o negar nada, ya que me parecería una falta de respeto con las imágenes originales.

Por último, ¿qué papel crees que tiene el tiempo en tu proceso, tanto en la repetición del bordado o en la forma en que tu obra se revela gradualmente ante los espectadores?

Siento que si te tomas el tiempo de crear una obra de arte, ese esfuerzo se repaga en el tiempo que toma contemplarla y considerarla. Si produces algo con un espíritu meditativo, el resultado exudará la misma cualidad. Nunca puedes ser responsable de la interpretación de tu obra por parte del público, pero siempre espero que los espectadores, como yo, busquen algo más profundo y gratificante, que entiendan mis métodos y respeten el posible tiempo que toma desvelar la maravilla tras la propuesta visual. Soy romántico por naturaleza, así que espero que la audiencia pueda disfrutar el respeto y la admiración que infundo en mis obras, tal como yo admiro las creaciones de los artistas de la historia.

The impressionist movement was characterized by visible brush strokes, an emphasis on the effects of changing light in their depictions, and their concentration of varied points of view, to name just a few things they altered with their new direction. In particular, I was interested in focusing on how they created a new visual rawness by allowing their brushstrokes to show. However, they also introduced a new way of presenting visual effects and tonal effects by layering color. For the first time, the average viewer could see how color and tone were built right before their eyes. The magic of viewing was developed step by step in front of you. Naturally, I wanted to find a way to interpret that ability that the impressionists developed. So, if the average viewer sees my artworks in person, they can witness that I do not just use a single color to create an effect.

Much like the Impressionists, I layer my threads in such a way as to create a new kind of color aesthetic sometimes by working with opposing colors. For example, to make a particular green tone for my artworks, I layer a brown thread, a yellow thread, and a blue thread. Combined, these threads can create the type of green I seek. Then, depending on the angle of the view, that same green might look bluer from one angle, or browner from another angle. In this way I can emulate the same visual effect in my artwork that the French impressionist painters first discovered in their work many years ago. I find that kind of concept very exciting. I do not pretend to be as talented as the famous French impressionists, but I am proud of myself that I figured out a way to introduce the layering of colored threads in the same way that those painters of yore layered their brushed paints.

At what point did you decide to incorporate bodies or faces into your work, and what is the reason for this variation?

Because I am a big aficionado of art history, I have a natural tendency to seek out and collect old paintings and drawings, as well as photographs from other eras. I refer to all of these paintings, drawings, and photos as ‘ghosts’. These ghosts can sometimes speak to you in a special way and bridge a contact from many, many years. I started to incorporate some of these actual objects about 6 or 7 years ago. I find it exciting to work with antiques and vintage things and reinterpret that visual language. Not every antique image can be reinterpreted in this way. I have ruined some antiques in this way, but so far, the successes outweigh the failures.

Do you think embroidery enhances or nullifies the existence of the body in your work?

I seek to create a type of aesthetic veil with regard to my Portrait Structures . I want my viewers to stop and take a closer look. So, in that regard, I think I am enhancing a portrait. I do not seek to nullify or negate anything, as I would consider that a disrespect to the original.

Finally, what role does time play in your process—both in the repetition of the embroidery gesture and in the way the work slowly reveals itself to the viewer?

I feel that if you take time to make a work of art then it repays you in the amount of time it takes to consider something. If you make something in a meditative spirit, then the end result will exude something meditative. You can never be responsible for how someone will view your artworks, but I always hope that those viewers, like myself, who seek something deeper and more fulfilling, will understand my methods and respect the amount of time it takes to possibly unveil the wonder behind the visual concept. I am an old romantic by nature, so I hope my viewers will also enjoy the respect and wonder that I infuse in my artworks, just as I wonder and respect the creations of those artists in history.

Colombia | Colombia

Por Lucía Rey. Académica e investigadora independiente (Chile)

Imágenes cortesía del artista.

Representado por Adrián Ibáñez Galería.

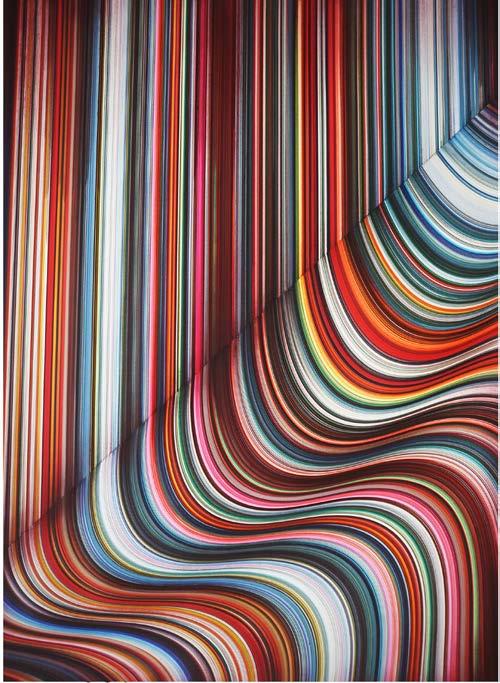

Inmanencia y ritualidad para una temporalidad contemplativa

“Como

está fuera del tiempo, se trata de lo que los griegos llamaban lo eterno, lo a-ídion, entendido no como una realidad abstracta que reposa en sí misma y está separada de nosotros, sino como esa tensión, que hace que la realidad (lo ente) se desoculte”

E. Grassi

l as obras de Wilmer Useche contienen sutilmente la cita de una tensión contemporánea entre la creación con materialidades manufacturadas en el oficio disciplinar y la tentación visual de percibirlas como productos digitales, algorítmicos. En el acercamiento a las obras se va desplegando una profundidad cromática tramada entre horas reflexivas cargadas de una potencia proveniente de un ojo arquitectónico. Esta visión entrenada del artista es lo que le permite componer, entre lo micro y lo macro, imágenes que pueden señalizar fenómenos ópticos de la fotográfica urbana acelerada, muchas veces no captable con una visión corriente. Así, las imágenes que emanan de sus obras pueden llegar a formar figuras simbólicas, abstracciones geométricas como también transportarnos a la física cuántica y la teoría de cuerdas.

Su cuidadosa elaboración técnica, transporta al artista, entre papeles de algodón, telas, reglas, patrones y plantillas a investigaciones sensibles que van impregnando la obra y que van tomando forma en las intensidades con las que el artista permite la fluidez del error y de lo imprevisto, en equilibrio con su meticuloso trabajo gráfico, entre bolígrafos, rapidógrafos, rotuladores y/o acrílicos.

Esta escena del taller comparte muchos elementos con un taller de costura, lo que no es algo intrascendente, pues el emplazamiento del espacio creativo del artista da cuenta de sus coordenadas compositivas. Se encuentra así en esa intimidad del tiempo del hacer creativo, entre materiales similares a los de la costura, pues trabaja desde el valor de la manufactura textil, indicando la fuerza de lo artesanal. Puede verse como una metáfora, ya que su confección va hacia la abstracción imaginal de los tejidos y urdimbres, elaborando figuraciones de hilos que componen unidades simbólicas.

En su trayectoria ha investigado colores textiles precolombinos con la intención de aportar creativamente al rescate de esa memoria ancestral, muy inspirada en patrones geométricos y mundos míticos fuera del tiempo lineal. Posiblemente, esta investigación del arte textil haya trazado en lo invisible puentes hacia un imaginario cromático contemporáneo. Muchas veces, lo contemporáneo parece una novedad, pero lo que se verifica en el estudio es que en los fondos de las más diversas culturas palpitan las mismas inquietudes y figuraciones vivientes en la psique, reapareciendo temporalmente, pero revestido de lenguajes técnicos específicos. Aquí, Useche añade intensidades lumínicas que citan la luz y la óptica digital, y compone figuraciones sutiles, casi transparentes, de hilos que unen vibratoriamente la realidad en lo imperceptible.

Immanence and rituals for a contemplative temporality

“Since it is outside of time, it is what the Greeks called the eternal, the a-ídion, understood not as a static abstraction apart from us, but a tension in which reality (beings) come into unconcealment”

E. Grassi

wilmer Useche’s artwork subtly references a contemporary tension between creating with materials from traditional crafts and the visual temptation to perceive them as digital or algorithmically produced. Engaging with his work reveals a rich depth of color woven over hours of careful reflection, showcasing the strength of an eye informed by architectural know-how. This trained sensitivity of the artist allows him to compose images that, at both micro and macro scales, evoke optical phenomena found in fast-paced urban photography, which are often difficult to capture with a more traditional view. The images that emerge from his work range from symbolic figures to geometric abstractions, but they are also reminiscent of quantum physics and string theory.

His thoughtful and technical creations guide the artist through sensory explorations among cotton papers, canvases, rules, patterns, and templates. These elements immerse his work and allow the artist to embrace the intensity in the fluidity of mistakes and unforeseen factors, balanced with his meticulous graphic work among pens, stylographs, fine liners, and acrylics.

This studio setting resembles a sewing workshop, which is significant because the environment in which the artist creates enhances the understanding of his compositions. In the intimacy of his creative process, surrounded by materials akin to those used in sewing, he celebrates textile production and highlights the importance of manual craftsmanship. This method of creation can be seen as a metaphor, because his confections embody an imaginative abstraction of textiles and warps, creating figurations of threads that build symbolic units.

Throughout his career, he has researched pre-Hispanic textiles to, through his artistic contributions, salvage ancestral memories—traditions that are heavily inspired by geometric patterns and mythical worlds that transcend linear time. Perhaps this examination of textile art has erected an invisible bridge towards more contemporary chromatic imagery. Oftentimes, the contemporary seems like a novelty, but upon further analysis, the foundations of the most diverse cultures resonate with the same latent concerns and vivid representations of the psyche. These themes might reappear temporarily, but disguised in different specific technical languages. In this regard, Useche adds luminous intensity to hint at light and digital optics, and builds subtle, almost transparent, figurations of threads that sync the vibrations of reality to the imperceptible.

Al ser un autor formado antes de la expansión de la digitalización, tiene la posibilidad de crecer y conocerse artísticamente a través del oficio disciplinar, que es un bagaje atesorado como conocimiento artesanal, proveniente del dibujo arquitectónico, que luego logra desplazar hacia el campo de las artes. Este desplazamiento le permite construir un lenguaje propio, en cruce estético con diversas disciplinas. El tejido visual de estos hilos de color son testimonio de las posibilidades de la sensibilidad y la imaginación “profundamente humana”, estableciendo un punto de inflexión, creativa y crítica hacia los procesos de generación de imágenes digitales construidas con algoritmos. En este sentido, lo que pulsa en estas obras son mensajes que atraviesan la temporalidad lineal acelerada del progreso tecnológico. Son obras que toman tiempo en su realización, mismo tiempo que simbólicamente puede transportar hacia una desaceleración contemplativa, a un horizonte abstracto de sentido cuántico, tan trascendente como inmanente, mismo que ha sido testimoniado desde lo múltiple a través del arte ritual de los pueblos originarios de América y que sigue pulsando transgeneracionalmente.

El acto repetitivo del trazado cromático a través de plantillas puede ir abriendo un estado hipnótico, no solo en quien “contempla” la obra, sino también en quien la realiza. Recordando que la contemplación no es lo mismo que la observación habitual de la cultura visual contemporánea. La contemplación (en su etimología de raíz latina contemplatio , que viene de templum : un espacio para la observación o un lugar sagrado) se refiere a la comprensión de la realidad viva, a detenerse para permitir que la obra hable y entregue conocimiento sobre sí misma. Simbólicamente, este trazo marcado por la repetición milimétrica transporta mnémicamente a una determinada actitud ritual inspirativa en el artista. Pues no es una máquina quien las “genera” e “imprime”, es un cuerpo sensible, que se permite en la creación artística habitar un mundus imaginalis (H.Corbin), un mundo intermedio entre el cielo y la tierra, entre lo visible y lo invisible, trayendo sincrónicamente de este espacio, que podríamos llamar “sagrado”, la inspiración creadora, como furor que inmanentiza la obra, dándole sentido y fundamento poietico que traslada el no ser al ser.

As an artist trained before the surge of digitalization, he had the opportunity to grow and develop artistically through his disciplined craft—a treasure trove of artisanal knowledge derived from architectural drawing—which he then managed to transfer to the field of the arts. This movement has allowed him to develop a language of his own that aesthetically merges different disciplines. The visual tissues of the colored threads are proof of the possibilities of ‘profoundly human’ sensitivity and imagination, thus constituting a turning point for creativity and criticism of last-gen digital image creation through algorithms. In this sense, his artwork pulsates with messages that question the accelerated linear time of technology-driven processes. These are works that take time to complete, the same time that can symbolically transport us toward a contemplative deceleration, to an abstract horizon of quantum meaning, as transcendent as it is immanent, which has been witnessed from multiple perspectives through the ritual art of the indigenous peoples of America and continues to pulsate transgenerationally.

The repetitive act of tracing colors through templates can induce a hypnotic state, not only in those who contemplate the work, but also in those who create it, noting that contemplation is not the same as mere observance of contemporary visual culture. Contemplation (from the Latin root contemplatio , which comes from templum : a space for observation or a sacred place) refers to the understanding of living reality, to pausing to allow the work to speak and impart knowledge about itself. Therefore, symbolically, these lines, defined by millimeter-precise repetition, imply a specific, inspirational, ritualistic attitude in the artist. It is not a machine that ‘generates’ and ‘prints’ these images; it is a sensitive body that allows itself, through artistic creation, to inhabit a mundus imaginalis (H. Corbin), a liminal space between heaven and earth, visible and invisible, bringing creative inspiration to this time-space, which we might call ‘sacred’. In this frenzy , his artwork becomes immanent, filled with meaning and a poietic foundation that transforms non-being into being.

Por Ivón Figueroa Taucán. Magíster en Teoría e Historia del Arte.

Imágenes cortesía de los artistas.

La valla metálica como símbolo de nuestro tiempo

desde hace 15 años, Antonia Wright y Rubén Millares desarrollan una práctica artística en común, a pesar de que sus formaciones artísticas son muy diferentes. Antonia inició su carrera a través de la poesía y la performance, a la que se dedicó por casi una década, abordando problemáticas sobre género y la autonomía del cuerpo. Rubén Millares creció tocando guitarra y batería, estudió contabilidad y finanzas, y se propuso buscar el balance entre ambas áreas, trabajando con el sonido, la luz, la música, el video y la serigrafía. Su colaboración parte desde una trayectoria biográfica compartida: tienen padres cubanos y crecieron en la misma área de Miami. En consecuencia, sus temas de trabajo recurrentes son la crisis de la migración a nivel global y la defensa del derecho a la protesta. Las vallas de acero iluminadas con LED, instaladas tanto en el espacio público como al interior de museos y galerías, son elementos centrales que caracterizan una serie de su producción visual.

The barricade as a symbol of our time

antonia Wright and Rubén Millares have worked together for over 15 years, although their backgrounds in artistic training differ greatly. Wright began her career in poetry and performance addressing gender issues and bodily autonomy for nearly a decade. In turn, Rubén Millares grew up playing guitar and drums, and later studied accounting and finance. Resolved to find balance between both worlds, he utilizes sound, light, music, video and screen printing in his work. The collaboration between these two artists stemmed from their shared life experience: their parents are Cuban and they brought up in the same area in Miami. Consequently, the most recurrent themes in their work are the global migration crisis and their advocacy for the right to protest. Steel barricades lit with LEDs –installed in both public spaces and within galleries and museums– are the central elements of one of the series they produced together.

¿Cómo llegaron a la idea de trabajar con vallas de acero?

Crecimos asistiendo constantemente a protestas con nuestros padres. Aprendimos que la protesta es un derecho esencial, y ambos mantuvimos esta práctica en nuestra vida adulta. Hemos notado, además, que ahora las manifestaciones son más prevalentes que nunca. Algunas de las manifestaciones más grandes están teniendo lugar en países donde protestar es ilegal. Cuando estallaron las protestas de Black Lives Matter en los Estados Unidos, comenzamos a analizar las imágenes de prensa de estos sucesos y nos dimos cuenta que casi todas las fotos mostraban vallas metálicas. Casi todo el mundo asocia estas vallas con conciertos o desfiles y, por ende, se les percibe como parte de festividades. Sin embargo, en el contexto de protestas, es cada vez más común que la policía las utilice.

Por este motivo, investigamos las vallas metálicas y examinamos los manuales de la fuerzas policiales para entender su uso previsto. Descubrimos que están diseñadas para camuflarse con el entorno, lo que explica su apariencia de acero sin lacar, pues se tornan inconspicuas. A pesar de su robusta apariencia, son livianas y fáciles de transportar. Su principal función es pasar desapercibidas mientras controlan y conducen las multitudes. Decidimos iluminarlas para hacer obvia su presencia y así demostrar lo generalizado que se ha vuelto su uso en espacios públicos. Nuestro objetivo es dirigir la atención a lo que hemos observado y concientizar al público sobre estos mecanismos de control tan comunes. ¿Podrían profundizar en la discursividad asociada al uso de la luz en sus esculturas?

En general, las barricadas se utilizan para generar una noción de orden. De hecho, al leer los manuales policiales, siempre se hace referencia a esto. No obstante, al ser tan livianas, a menudo las toman y se arrojan a la policía. Entonces, creo que su función es ambigua. ¿Nos protegen o nos controlan? ¿Será que provocan más violencia en las protestas?

How did you land on the idea of working with steel barricades?

We grew up attending demonstrations constantly with our parents. We learnt that protest was a crucial right, and we maintained this practice into adulthood. We’ve observed that protests are now more prevalent than ever. Some of the largest demonstrations are occurring in countries where protesting is illegal. Then the Black Lives Matter protests emerged in the U.S. We began closely examining news images of these events and noticed that nearly every protest photo contained steel barricades. Most people associate barricades with concerts or parades. They’re seen as part of festive activities. But in protest contexts, police are increasingly deploying them.

We researched barricades, reviewing police manuals to understand their intended use. They’re designed to blend into the environment, which explains their unpainted steel appearance. This makes them inconspicuous. Despite their sturdy appearance, they’re lightweight for easy transport. Their primary function is to remain unnoticed while controlling and directing crowds. We decided to illuminate them, making their presence obvious and demonstrating how pervasive they’ve become in public spaces. Our goal was to draw attention to what we had observed, to make the public aware of these ubiquitous control mechanisms.

Could you elaborate on the idea behind the use of lighting in your sculptures?

Normally, barricades will be used to create an idea of order. If you read the police manuals, it’s always about it. But they’re very light and oftentimes, they can be used and thrown back at the police. I think their purpose is ambiguous. Are they protecting us, or are they controlling us? And are they causing more violence in protests?

Vimos una imagen de las manifestaciones en Hong Kong donde los protestantes usan a su favor las vallas metálicas que coloca la policía. Las atan y arman estructuras para protegerse. Subvierten el uso previsto de las vallas, que es controlar los cuerpos en una protesta. Así, tomamos una imagen y en una de las piezas comenzamos a trabajar con la iluminación, cubriendo las vallas con luces LED. Una vez iluminadas, se vuelven tan brillantes que verdaderamente revelan la frecuencia con la que se usan en las calles. Es como si la luz las hiciera casi inevitables.

¿Qué contextos políticos específicos dialogan con esta serie? Creo que es una muestra bastante atemporal. Comenzamos a trabajar en estas obras en el 2020, cuando emergieron grandes manifestaciones en América Latina. En ese marco, nuestra obra se volvió muy relevante de súbito. Tuvimos instalaciones en la playa, en el mar, por ejemplo, lo que transmutó el contexto de las barricadas después de que ya habíamos trabajado en esta obra. El arte tiene el potencial para prolongar esta conversación más allá del ciclo de noticias. En cuanto a si estas obras provocan un nuevo tipo de protesta, es ambiguo, y cuantificarlo resulta difícil. Sí son generativas, en el sentido que suscitan conversaciones en torno a estas problemáticas. Eso es lo que puede engendrar el arte; puede detener el tiempo y originar debates que lleven a alguien a protestar, donar dinero, o participar en la política. Es una especie de portal diferente. Tratamos de enfocar esta noción, y las vallas representan objetos inanimados que la condensan. Se pueden aplicar a cualquier situación de protesta. Se nos ha acercado gente de todo el mundo, gente que usa las vallas a su modo. Casi todos los países tienen su propia versión. Siempre

We saw an image from the Hong Kong protests. And there, protesters use the barricades that are put up by the police. They’ll zip tie them together and will create a structure to protect themselves. They subvert this intended use of what the barricades are supposed to be, which is to control bodies in protest. So, we took one image. One of the pieces that we started working with light was that we would take the barricades and cover them with LED lights. With the light, they become so bright that they really talk about how often they’re used on our streets. The light almost makes them unavoidable.

What specific political contexts interact in this series?

I think it’s a very timeless piece. We started making these works in 2020. There were big demonstrations in Latin America. Suddenly, our piece became very relevant. We did it out on the beach, on the water, for example, changing the whole context of these barricades after we had already been working on this piece. Art has this potential to continue the conversation longer than a news cycle. In terms of whether these works cause a new type of protest, it’s ambiguous, quantifying that is difficult. But it’s generative in that it causes more conversations about these issues. That’s what art can do. It can stop time and create these conversations that may lead someone to protest, donate money, or get involved politically. It’s a different type of portal.

We try to shift to a point, and the barricades do that by using this inanimate object that condenses the idea down. It can be applied to any protest situation. People from all over the world have come up to us and applied it on their own. Almost every country has had their form

se ven barricadas. Incluso hoy, con la situación migratoria, con las deportaciones en Estados Unidos, hay protestas en todas partes. Las vallas son muy relevantes; pensamos que son un símbolo de nuestro tiempo. Hablan de seguimiento y control, pero también de resistencia. Asimismo, es importante la subversión de este objeto: algo concebido para usarse contra ti se invierte y se usa en contra de la autoridad.

¿Consideran las cargas simbólicas e históricas de los lugares donde instalan sus esculturas al momento de decidir trabajar en ellos?

Absolutamente. Siempre que nos invitan a realizar una instalación investigamos la historia de las protestas en esa zona. Nuestras instalaciones son in situ. Cuando nos invitan, encontramos el mejor uso y diseño para la obra, dependiendo de la arquitectura del espacio. Luego, estudiamos la historia del lugar o lo que ocurre con la política del entorno. A veces, surgen temáticas medioambientales. En una oportunidad creamos una obra en la que emergieron problemas sobre el medioambiente y nos subimos a un árbol con las barricadas. Eso fue articulado como respuesta a las protestas en Atlanta. Siempre analizamos la arquitectura para crear una obra específica para el espacio. Después, tratamos de usar las imágenes que hemos visto en las protestas y las aplicamos en el espacio. Por ejemplo, realizamos una instalación en Museo Lowe de la Universidad de Miami, donde tenían una viga enorme a 4,5 metros de altura. Como a menudo los protestantes usan las vallas metálicas como escaleras, apilándolas, nosotros replicamos esta disposición en el edificio para demostrar cómo se usan las vallas en protestas reales. Esta obra celebra nuestro derecho a protestar dado que, ahora mismo, nos lo están quitando.

of this. Every time, you will see a barricade. Even today, with the migratory situation, with deportations in the US, protests are happening everywhere. It’s very relevant. We think of the barricade as a symbol of our time. It’s about surveillance and control, but also resistance. The subversion of that object is important—an object supposed to be used on you is turned around and used against the authority.

When a location is decided, do you take into account the history and symbolism of the sites for your installations?

Absolutely. Whenever we’re invited to do one of these, what we’ll do is research the history of protests in that specific area. They are site-specific works. When we’re invited, we figure out what the best use and the best design is for the work, depending on the architecture of the building. Then the history of the place and what is going on in that moment politically. It could be environmental. We had one we did that brought in environmental issues, and we went up into a tree with the barricades. That was in response to the Atlanta protests.

We always look at the architecture of each space to make it site-specific. Then try to use the imagery that we’ve been seeing in protests and apply it to a space. For example, we did one at the Lowe Art Museum at the University of Miami, and they had a big column that was up 15 feet in the air. The protesters used these barricades as stairs a lot of times. They stack up this way like a ladder. We went up and over the architecture of the space to show how they are used in actual protests. This piece is about celebrating our right to protest because as we speak, they’re taking it away.

Por Julio Sapollnik. Crítico de Arte (Argentina)

Imágenes cortesía de la artista.

Representada por Galería Imaginario.

gloria Matarazzo realiza una operación poética con la imagen: la transforma, la reinventa, la libera de sus ataduras representacionales. Sus fotografías, intervenidas digitalmente, ejercen una atracción hipnótica que detiene el tiempo. No es posible recorrerlas con ligereza: exigen permanecer. Invitan a una contemplación activa, donde la mirada, en un inicio confiada, es pronto interrumpida por un elemento inesperado que reconfigura el conjunto. Esa dislocación no produce desconcierto, sino un goce estético: el espectador deviene explorador, constructor de sentido.

Matarazzo cultiva una estética de la lentitud. En un mundo saturado de imágenes instantáneas y consumo visual acelerado, su obra propone lo que Shōzō Uchida llama “estética del intervalo”, donde la belleza surge de la pausa, de lo que no se dice, de lo que no se muestra del todo. De este modo, la artista se inscribe en una tradición contemporánea que, como defiende Byung-Chul Han, reclama una “política del cuidado” frente a la hipertransparencia y el exceso de positividad visual: “Contemplar es resistir al imperativo de producir”.