Kultura: Municipal Halls of the BARMM

Paglulunan: The Development of Arkitekturang Pilipino

Proyekto: Cor Jesu Oratory

Kultura: Municipal Halls of the BARMM

Paglulunan: The Development of Arkitekturang Pilipino

Proyekto: Cor Jesu Oratory

The UAP journal has inherent opportunities as the official repository, publication and exhibition reading material for the creative expressions of Filipino architects in the Philippines and on the global stage. Taking lessons learned from the past and acknowledging that the technological and cultural advances have already altered editorial content, the UAP Journal will undergo a process of change and development-an evolution. The journal is evolving so that its content, brand, voice, and visuals can keep up with the contemporary times.

The evolved journal will have diverse contents from scholarly articles, to essays, project features and news. This varied content allows us to feature more architects and expand readership. This allows more architects to express themselves creatively thru writing and content creation making the journal more inclusive. The evolution continues with the introduction of three main sections of the journal, namely: Karunungan, Proyekto and Kultura. We hope that through these sections, more architects will be enticed to contribute content and expand the readership of the journal beyond the membership.

In this issue are 10 articles written and delivered by architects both in the country and abroad. For this first issue, our theme is on The Filipino Brand. This theme seeks to celebrate the distinctive Filipino design and touch that makes us unique, distinguishable, and globally competitive. We would like to thank all the contributors for sharing your insightful study, research, and projects.

We firmly believe that by evolving the UAP journal, we can express our architectural identity into new platforms. It allows acceptance and showcases the influence of contemporary times while not forgetting its roots and heritage. We enjoin everyone to welcome the evolution of the new journal and embrace its new identity as ARQUITEKTURA - The official journal of the United Architects of the Philippines .

We wish everyone an inspiring and rewarding reading. Arquitektura Team

The fast-paced lifestyle nowadays makes people rush every time and expect instant results. There are times that we need to sit back, relax, and update ourselves through media related to our profession. This does not entail work but more of inclusivity and information dissemination. As architects, we are creative and critical thinkers, we need continuous inspiration and information.

It is evident that we are one of the best architects in the world and we have proven this numerous times. Top architectural firms in the world would most likely include Filipino architects who are instrumental in creating architectural icons from concept-making down to its execution. We have established ourselves as a talented lot, globally competitive and very resilient with whatever challenges are thrown at us. This is what makes us different and distinguishable -- we can easily adapt yet still manage to excel. Let us break out from the stigma of being a backdoor platoon. It is time to step up as we are Filipino Architects who can show the world that we belong up there.

There are so many ways to keep people informed, entertained, and educated. The line of communication has evolved throughout the times, indeed, technology made information faster and people closer.

“ARQUITEKTURA”, as the official journal of the United Architects of the Philippines is in line with the times but still very much grounded on tradition. The authors have ensured that the maiden issue will be focusing on us, the world-class Filipino architect, and our branding. This is one effective tool to showcase who we are, what we can do and how much we matter as architects in both our home country and overseas. We should all capitalize that we use all platforms to show everyone how unique, talented, and vital we are in nation building all across the globe.

We are Filipino Architects and “ARQUITEKTURA” is for all of us.

Ar. Armando Eugene C. De Guzman UAP National PresidentMetamorphosis is a change of physical form, structure, or substance. Just like how a caterpillar evolves into a butterfly, this rebrand is a part of the evolution of the UAP journal to suit the ever-changing and growing industry. I am delighted and honored to be part of the first issue of Arquitektura and be able to congratulate the team behind this project. Envisioned to capture all segments of the market, this journal is no longer just for local consumption; it shall now be a globally-recognized architectural journal that is filled with the Filipino brand and culture.

With this new audience, we hope to present astonishing projects, articles and the like by professionals in the architecture field. Again, congratulations to the entire editorial staff and to the contributors that made this rebrand possible. I am looking forward to holding a copy of the first issue of Arquitektura during the upcoming 47th UAP national convention.

Ar. Richard M. Garcia, FUAP, AA, PALA, PIEP National Executive Vice PresidentWarmest congratulations to the team that brought this year’s UAP Journal uniquely branded as Arquitektura, being the symbol and the face of our organization’s scholarly and creative works in the global front. The Professional Development Commission has successfully gone leaps and bounds in its effort to showcase to the members and to the general public a topnotch product that promotes that distinctive Filipino brand in the design arena.

We have barely explored the realm of the 21st Century and producing a material that ushers us into understanding its cross-border elements and how Filipinos can exhibit their artistry and global products is truly something that we as architects must be very proud of.

Let Arquitektura cascade to us new and interesting insights on Filipino Architecture and let it also learn from us as we contribute to the call for world-class outputs that are feature-worthy and deserving to land on the pages of this journal.

Again, my hats off to the team and may you be able to sustain this victory for our organization and for our profession. Let this product continue to spread the good news about our very own Filipino architecture. Mabuhay kayo at mabuhay ang mga Arkitektong Filipino!

Ar. Jonathan V. Manalad, PhD., UAP, PIEP Secretary General

Incorporating the rich history and traditions of Mindanao into a modern and contemporary interpretation of the Taboan.

Karunungan

Envisioning resilient, comfortable and secured walkable facilities and infrastructure in highly urbanized areas.

Paglulunan

An exploration of the forces that led to the continuous development of Philippine Architecture.

Signalling the rebirth to one of the nation’s enduring symbols.

Exploring concepts on spaces that heal.

K-Farm

Gianfranco Galagar

Exploring the role of today’s architects in public architecture.

Justine Eduave

Embracing uniqueness and the diversity of the Filipino in a modern place of worship.

20 24

Gloryrose Dy-Metilla

Kultura

Kawayan Journey

Anthony Sarmiento, Jed Michael de Guzman

Architect Jed Michael de Guzman’s kawayan journey.

CDO Heritage Zones

Aimeelou Jean Demetrio

Insights on Kagay-anon culture, heritage, and historical identity.

Aimeelou is a Cagayan de Oro city-based architect and an active officer of UAP CDO Bay Area Chapter. Coming from a family affiliated with the Philippine Culture and Local History in Mindanao, she has interests in history, anthropology, performing arts, graphic design, and illustration. Stumbling on a German version of Tadao Ando’s book of sketches sparked her love for architecture. Since then, she continues to gain experience exploring and learning more about design and other operations within the field of architecture. In her senior year, she was awarded Best Thesis in the Architecture Department for her undergraduate thesis, Visage of the Lumad: Proposed Northern Mindanao Lumad Heritage Center. In 2013, she graduated from Mindanao University of Science and Technology (MUST) with a Bachelor of Science in Architecture degree. Before becoming a registered and licensed Architect in January 2016, she was an apprentice to Ar. Edwin Uy and Ar. Jonathan Sogoc. She was a freelance architect for many years before becoming a College Instructor for the University of Science and Technology of Southern Philippines (USTP) in Cagayan de Oro City under the College of Engineering and Architecture (CEA). She is currently the Cluster Head for the History and Theory of Architecture subjects in the Department of Architecture for the Undergraduate Program Bachelor of Science in Architecture.

Allan SilvestreAllan is the Project Architect of Poblacion Market Central. He joined PCTAN Architects and Associates in 2012 as an intern. At 22 years old, he gained his professional license that elevated him to Junior Architect. He is also a corporate member of the United Architects of the Philippines – Davao Alpha, as well as the Philippine Institute of Architects

– Davao Section. Currently, he is one of the company’s Associate Architects. Outside of his project work, Allan is a homebody who loves reading books, doing handicrafts and a certified plant lover.

Anthony Demin Sarmiento, is a graduate of Architecture at Mapua Institute of Technology, and is having his graduate school in Urban Design at the University of Santo Tomas – Graduate School. He also studied at Bamboo U, Bali, Indonesia a university specializing in Bamboo Design and Construction. Ar. Sarmiento is a registered and licensed Architect, Environmental Planner and Master Plumber. He is an active officer of the United Architects of the Philippines and a member of the Philippine Institute of Environmental Planners, he also holds an International Associate membership at the American Institute of Architects. He had worked with the architectural office of Arch. William V. Coscolluela and Ar. Felino Palafox Jr. who has been his mentors. At present he is the principal architect of Genius Loci Architects, an architecture and parametric design consultancy firm. Also, he is passionate about architecture education and research as he currently teaches at the National University College of Architecture. He also speaks Deutsch (German) and Nihongo (Japanese). He is a professional watercolor artist and a violinist.

firms in the Philippines, Archion Architects. After leaving Archion in 2020, he joined the government workforce as an architectural design consultant for the governor of Marinduque, where he was exposed to different public officials in the province and provided architectural advice and solutions to selected projects. He is currently pursuing his master’s degree at the University of the Philippines-Diliman to expand his knowledge so that he can share his learnings to new generations of Architects.

Justine is an architect who hails from Cebu Institute of Technology-University. She is part of Zubu Design Associates where she handled the Cor Jesu Oratory project. As part of the team handling Cor Jesu Oratory during the contract documentation of the interiors and construction supervision phase, she is proud to have worked with and collaborated with the other designers, contractors, and suppliers throughout the project. For Justine, it was a humbling experience to have been part of the collaboration team to design, plan, and execute the structure up to its inauguration day and even during post-construction.

Bryll is a licensed Architect, Master Plumber, and a qualified Safety Officer. He is a member of the United Architects of the Philippines Manila Centrum Chapter and currently an architectural private practitioner, and a parttime professor at the National University – Baliwag campus. He obtained his bachelor’s degree at National University-Manila in 2016 and became a design architect at one of the premier architectural

Trained in Bali under Elora Hardy and BambooU, he extends his passion and knowledge of Bamboo to support his advocacy of a sustainable Philippines. He believes that by spreading what he learned means that giving the Filipinos to thrive in more ways than one. He shows how diverse Bamboo can be in terms of design, while demonstrating how to care for it and get to know its properties so we may be able to utilize all its strength while overcoming obstacles that may come with working with it. His holistic approach to training allows for participants to fully understand the scope of the Bamboo, while his love for it and our nation fuels passion and eagerness to learn.

Aimeelou Jean Demetrio Anthony Sarmiento Bryll Edison Par Jed de Guzman Justine EduaveGerard Lico is a Professor and Director of the Research Office at the College of Architecture, University of the Philippines Diliman. He practices architecture as a heritage conservation professional and designer of institutional buildings. He is a prolific author of publications on Filipino architecture and cultural studies, curator of architectural exhibitions, and director of documentaries on Philippine architecture.

He has been involved in the conservation of landmarks such as the Manila Metropolitan Theater, the Rizal Memorial Coliseum, and the core buildings of the University of the Philippines campus in Diliman. He also served as a consultant of conservation planning initiatives for other local and national heritage sites across the country. Apart from presently serving as Consulting Architect for the City of Valenzuela, he heads a multidisciplinary, research-oriented design consultancy practice.

Gianfranco Galagar is a UAP architect who has been working in Hong Kong for the past four years and has worked in various offices on projects with a focus on social agenda. His twoyear involvement with Avoid Obvious Architects provided him experience for a more bottom-up approach to the practice. He was part of the team that designed K-Farm, a public urban farming educational and wellness park that won the American Institute of Architects Urban Design Honor Award and Sustainability Award. He was also involved in the writing of Adventures in Architecture for Kids, a book that introduces architecture and design thinking

to children through design exercises in the hopes that these future generations will lead the future with a designer’s mindset. Currently, he works at Domat Community and Architecture, a not-for-profit practice which aims to work with people who cannot usually afford architectural services.

Rose is an architect and the Director of Swito Architectural Designs and BalayBalay3D Architecture. She is a product of University of the Philippines Mindanao – BS Architecture in 2009 wherein she garnered the Best Thesis Award and shortly after she won the Red Point National Thesis Award, an award given to exemplary undergraduate Architecture thesis in the Philippines. In 2018, she finished the Design Summerschool from the College of Architecture and Urban Planning in Tongji University, Shanghai, China, and then her Masters in Urban and Cultural Heritage from the Melbourne School of Design, University of Melbourne, Australia with an Australia Awards Scholarship. Currently finishing her Doctor of Philosophy in Management at the University of Mindanao.

She has been a United Architects of the Philippines North Davao Chapter President 2015 - 2016, Balangkasan Chair for Area D in 2016, and Editor of Area D Committee of UAP Journal under the Commission on Professional Development 2019 -2020 and a member of the International Council on Monuments and Sites or ICOMOS.

Currently, she is the founding partner of Swito Designs Architects. A studio is focused on Cultural Sensitivity in Design

and Urban and Cultural Heritage. The firm is currently working on the Department of Tourism Region XI Cultural Complex and Bangsamoro Ministry of Interior and Local Government Infrastructure Projects and international projects.

Apart from being an architect, she is also the Editor in Chief of Filipina Architect Resource Magazine, an online magazine she created during the pandemic.

Louie Nandro M. Vito is a Filipino Architect from San Mateo Rizal, Artist, Educator and a community Architect with specialization in Wellbeing Architecture by designing holistic approaches for the people who really matter most. He also specializes in Creatives and in handling corporate Events.

He has experience working in various Local and international companies for more than a decade and doing community service as a Consulting Architect for some Local Government Units in Luzon.

He is an active member of Rotary Club San Mateo Central, National Real Estate Association of the Philippines and United Architects of the Philippines, and became the President for UAP QC Elliptical Chapter in the year 2012 as the young President of the record.

A faculty instructor at Central Colleges of the Philippines for a year and for National University Manila for almost Nine Years and a pioneer for National University Fairview for two years.

Louie Vito

The search for Arkitekturang Pilipino has been a quest undertaken time and again by many architects of generations past and present. It has boggled the minds of both practitioners and scholars, each quest in search of singular typological examples. Many posit that the quintessential Filipino architecture may be seen in the bahay kubo, or the bahay na bato of yore. But even these examples fail to fully encapsulate the complexities of the Filipino spatial experience as it was and has become. Moreover, the multi-faceted experience of an archipelagic nation, which has witnessed the arrival of many influences, betray a development that may be better appreciated beyond a distillation into one or two building types and spaces. Rather, it would be better seen as spaces in relation to the forces that have shaped them, allowing us to see not only spaces, but places.

After all, architecture goes beyond merely demarcating and creating spaces. It is a practice of paglulunan or placemaking—where raw spaces are inhabited by people and imbued with meanings and memories. Architecture thus becomes artifacts that encapsulate the spirit, values, and sensibilities of the people that produced them.

Architecture can be a mirror into the lives and contexts of ages past; and with an understanding of these, we can better know the built environment, its ethos, and the people who inform its being. Upon gaining this true essence of Arkitekturang Pilipino, we may learn and better participate in the process of placemaking, and from there, preserve Filipino places for the future to inherit.

Arkitekturang Pilipino: A History of Architecture and the Built Environment in the Philippines is a two-volume work outlining a transdisciplinary approach to the development of the Philippine Built Environment. The book covers the history of Filipino architecture from early history to the contemporary built environment and shows a rich visual narrative of Filipino architecture through time. The book also highlights the development of the Philippine architectural profession, and the field of heritage conservation in the Philippines.

Arkitekturang Pilipino: A History of Architecture and the Built Environment in the Philippines is a two-volume work outlining a transdisciplinary approach to the development of the Philippine Built Environment. The book covers the history of Filipino architecture from early history to the contemporary built environment and shows a rich visual narrative of Filipino architecture through time. The book also highlights the development of the Philippine architectural profession, and the field of heritage conservation in the Philippines.

Architecture began as a response to nature. Man needed to shelter oneself and to provide a suitable venue for the activities of the day, giving rise to creative responses for addressing spatial requirements. Our Austronesian lineage imparted a primeval affinity towards the water—and the communal nature of maritime life. This in turn informed the development of our vernacular architecture, which gives premium to multi-functional, shared spaces.

Man’s first experience of architecture was with crafting ways to shield themselves from harsh environmental conditions. In the Philippines, early inhabitants made homes out of caves and crafted ephemeral lean-tos for use when out foraging or hunting. Later, the development of communities across the country gravitated towards living near bodies of water, which afforded better access to basic needs for survival and the development of agricultural methods allowed for food security and drove people to go search for more fertile lands, wherever they may be. Water travel developed and became a means upon which communities grouped and orchestrated themselves, developing a culture around the barangays which bore them to new lands. The rigors of maritime travel created a system of communal living which secured and sustained the boat communities and was later carried on to life back on dry land. The early barangganic societies became the basis for social arrangements and dictated how space would be allotted among people.

Our notions of vernacular architecture find their roots here; the affinity for shared spaces used for many functions. The multi-use space of the bahay kubo and other houses on stilts across the archipelago developed uniquely according to the necessities and constraints (ecological or otherwise) of their specific cultural communities and locales. The archipelagic nature of the country, coupled with its almost inhospitable conditions of raging typhoons, humid days, and constant earthquakes mean that the country’s architecture must be able to respond to these adverse conditions. Vernacular architecture is built on the ability to intuitively harness one’s surroundings to create spaces. Hence, while similar in essence, Philippine vernacular architecture exhibits different materialities and morphologies. The introduction of Islam and Muslim culture into the islands contributed

Philippine vernacular architecture’s sensibilities stem from Austronesian maritime living—being in close proximity to the water or residing on boats with communal arrangements. This in turn created an affinity for shared, multi-use spaces for the conduct of everyday activities.

The vernacular sensibilities are carried on to life in other conditions such as in mountain dwellings, as seen in the Ifugao fale, which uses wooden boards for its walls and floors to allow for better heat retention during cold weather, as opposed to lowland dwellings made of thatch or woven bamboo, which provide a climatic permeability; ideal for warm, humid conditions.

The Spanish colonial condition introduced notions of urban life within the cuadricula, and the vernacular houses evolved into the arquitectura mestiza or hybrid architecture of the bahay na bato. The shift in the cultural and economic environment of Filipinos is enacted in the encounter of colonial control and native ingenuity in architecture.

Philippine vernacular architecture’s sensibilities stem from Austronesian maritime living—being in close proximity to the water or residing on boats with communal arrangements. This in turn created an affinity for shared, multi-use spaces for the conduct of everyday activities.

The vernacular sensibilities are carried on to life in other conditions such as in mountain dwellings, as seen in the Ifugao fale, which uses wooden boards for its walls and floors to allow for better heat retention during cold weather, as opposed to lowland dwellings made of thatch or woven bamboo, which provide a climatic permeability; ideal for warm, humid conditions.

The Spanish colonial condition introduced notions of urban life within the cuadricula, and the vernacular houses evolved into the arquitectura mestiza or hybrid architecture of the bahay na bato. The shift in the cultural and economic environment of Filipinos is enacted in the encounter of colonial control and native ingenuity in architecture.

to a unique development of vernacular architecture. It created places infused with Islamic sensibilities and informed by the rigors of a maritime Muslim culture, assimilating with the local cultural and spatial structures that have been established prior to its arrival in certain areas.

Morong Church, Rizal. Grand churches developed a local flair through the meeting of the friar’s fleeting memories of European and Mesoamerican churches, and the talents and capabilities of local artisans. Coupled with a uniquely volatile environment in the path of earthquakes and typhoons, the earthquake baroque churches emerged.

The colonial encounter, beginning with Spain in the 16th to 19th century, and later with America in the 20th century, brought sweeping, if not severe changes to the Philippine cultural landscape. To an extent, the colonial encounter gave birth to the idea of a Filipino nation—the various archipelagic polities forged into one political body under Hispanic, then American rule. In the process, the notions of nationhood would emerge among the local population, as they begin to recognize and form an identity which may only be realized with independence.

The arrival of colonists to the country introduced a new spatial order—characterized by a dynamic built on domination, segregation, and control. This was enforced through rigid social hierarchies along racial lines, the assertion of cultural superiority, and later, the imposition of an encompassing techno-scientific agenda to regulate colonial bodies. Even in this case however, the process of resistance and counter-cultural interactions betray the fact that the Filipino is no mere recipient, but an active player in shaping its identity and places.

Hispanic towns and cities were dominated by the cuadricula or grid street system, which allowed for colonial administration to be meted with military efficiency. The intense environmental conditions of the country forced colonial architecture to adapt, taking on the essential vernacular architecture and reinterpreting it with local materiality. Thus, the quintessential Filipino-Hispanic bahay na bato, at its core would be a wooden house on stilts dressed with a veneer of stone at its base. The strictly regimented spaces of

Western residential architecture are appropriated for the social order of the local population. While bearing many rooms, the Filipino-Hispanic residential archetype (which also defined the institutional and commercial archetypes of the period) would be composed of multiple shared spaces, defined by their relative permeability shrouded with Spanish and European finery. Colonial church design gave way to sprawling and buttressed development over soaring architectural forms. Churches were contrived from vague memories of Hispanic examples, reinterpreted with the variety of Chinese and other Southeast Asian influences that converged in the Philippines. The baroque architectural sensibility boded well with Filipino tastes, creating earthquake baroque architecture. Even the introduction of technological feats such as steel and concrete construction, for example, were meant as a response to the unique conditions of the country.

A short-lived Independence was achieved from Spanish rule, to be eclipsed by the arrival of American forces. The American colonial encounter would be remarkable for the use of techno-science to control Filipinos within spaces, enforcing medical interventions on the unfit, native bodies. Moreover, the technological advancement of the period and the American imperialist agenda were garbed with the veneers of neoclassicism. The exercise created buildings which are imbued with the legitimacy of classical antiquity—expressed in ferroconcrete— to project a democratic lineage which the colonial authority wished to impart on the native population as an act of altruism.

Among the requisites of a sustainable, independent nation was the greater inclusion of capable and competent Filipinos in the colonial bureaucracy.

Laguna Provincial Capitol, Sta. Cruz, Laguna. American colonial authority was exercised through state architecture built in the image of imperial classicism. Through mission revival and neoclassical architecture, the colonial government enforced its power across the archipelago. Eventually, this would be subverted by the pensionado architects with the introduction of Filipino elements in their own designs of state buildings.

Crystal Arcade, Escolta, Manila. Art deco became an outlet for Filipino architects to incorporate local imagery more apparently into their designs. As the nation grew closer to independence, the built environment was changed into an image of decadence and hope for the future.

Laguna Provincial Capitol, Sta. Cruz, Laguna. American colonial authority was exercised through state architecture built in the image of imperial classicism. Through mission revival and neoclassical architecture, the colonial government enforced its power across the archipelago. Eventually, this would be subverted by the pensionado architects with the introduction of Filipino elements in their own designs of state buildings.

Crystal Arcade, Escolta, Manila. Art deco became an outlet for Filipino architects to incorporate local imagery more apparently into their designs. As the nation grew closer to independence, the built environment was changed into an image of decadence and hope for the future.

Specifically in the Bureau of Public Works, the return of the pensionado architects who were trained in the United States and Europe, demonstrated the cultural sophistication that signified the Filipino’s readiness for independence and acceptance into the family of nations. The inclusion of native architects in the state building program coincided as well with the rise of art deco and greater economic prosperity, bringing significant changes to the lifestyles of Filipinos. Art deco became a manner for local architects to better explore the nation’s architectural character, allowing a generation of Filipino architects to express their local identity in anticipation of independence.

The intersections of local vernacular knowledge and experiences produced a unique, creative response to the colonial encounter. Jubilation over impending emancipation was overshadowed by the clouds of war, which brought widespread destruction to the country, destroying the work of many generations. Though many aspects of the nation’s architectural heritage were lost in the war, the promise of independence generated a renewed sense of hope. As the Philippines rose from the ashes, the world now welcomed a new and independent Filipino nation.

Now an independent nation amongst other sovereign states, the Philippines needed to assert itself on the international stage, while reeling from wartime destruction. Modernism provided a welcome way to address the growing need for functional and lyrical spaces devoid of colonial associations. While homogeneity was the ultimate form of modern architecture, the concurrent need to assert one’s individuality and identity in architecture was a primary goal of the post-war years. Through modernism, local architects asserted and explored notions of Filipino identity in the built environment, adapting the international style to the tropical environment of the country.

Stylistic explorations ranged from the literal to the poetic interpretations of local design sense in the built form. For many, the dictum of “form follows function” that characterized modernism yielded spaces that were spartan within but outwardly unique and at times unconventional, through the use of tropical sun-shading devices such as brise soleil, pierced screens, and deep overhanging eaves. The best examples of Filipino modernist spaces are delicately balanced form and function—aesthetics, practicality, and economics. Often however, many other examples across the archipelago ended up with structural functionality becoming the paramount concern, leaving aesthetic merit behind.

Department of Agriculture, Diliman, Quezon City. Post-war architecture was characterized by modernism, which architects used as a means to break away from the vestiges of the colonial past. The clean lines and bold geometry of modernism was infused with design elements that adapted the international style to the local tropical environment—and afforded the inclusion of unique designs such as carabao-head brise soleil or sunbreakers.

Architecture as Self-Actualization

Department of Agriculture, Diliman, Quezon City. Post-war architecture was characterized by modernism, which architects used as a means to break away from the vestiges of the colonial past. The clean lines and bold geometry of modernism was infused with design elements that adapted the international style to the local tropical environment—and afforded the inclusion of unique designs such as carabao-head brise soleil or sunbreakers.

Architecture as Self-Actualization

Modernism’s potential for expressing Filipino identity found great opportunities in state architecture. The wave of government constructions needed for housing the expanding state services and functions provided a welcome recipient for direct interpretations of Filipino architectural forms. Perhaps, the largest examples of these may be found throughout the post-war and Marcos eras, defining the local architectural milieu. Nativist tendencies in architecture were further intensified with the state-sponsored architectural agenda under the Bagong Lipunan program of the authoritarian regime. Modernism’s limits as a tool for expressing individuality and forward-thinking were tested in this period, resulting in various edifices to serve the caprices of the regime. Cracks began to appear in the machinery of the regime, owing to the various abuses and atrocities it has committed, ultimately causing its downfall. Likewise, the homogenizing tendencies of modernism became more apparent; thus a new stylistic development emerged to better express and appreciate local identity. A return of appreciation for ornament and interest in historical references drove a romantic way forward for Filipino architecture. Thus, the singularity of modernism gave way to the plural expressions of postmodernism.

Postmodern exploration persists in contemporary urban scenography. The wealth of historical references and architectural possibilities offer a wide trove from which notions of Filipino architecture may be better defined, given emphasis, informed, and built upon. An appraisal of the contributions of the past to the current possibilities and realities of Philippine architecture must be staked, so that the process of placemaking may continue to flourish more meaningfully.

Accompanying a contemporary wave of architectural nostalgia, the recognition of our shared heritage becomes a matter of interest. The process of heritage conservation is a negotiation of narratives among various stakeholders. It is a process of navigating tangible layers of history and intangible values of a building to distill which elements matter to the people, and which facets they wish to conserve and pass on to the next generations. Heritage builds on the architectural pedigree of a place, which serves as a springboard from which we can assert, reify, and cherish our shared identity and cultural memory.

Heritage conservation, more than the preservation of the tangible remains of the past, is a preservation of the knowledge and sensibilities that have long informed the creation of the Philippine built environment. As Filipino architects, we are now called to create buildings which preserve, build on, and propel Philippine architectural identity to new grounds.

San Miguel Headquarters, Mandaluyong, Metro Manila. With the pitfalls of modern architecture becoming apparent, architects ventured into creating works with romanticized influences, references to the past, and sustainability in mind.

San Miguel Headquarters, Mandaluyong, Metro Manila. With the pitfalls of modern architecture becoming apparent, architects ventured into creating works with romanticized influences, references to the past, and sustainability in mind.

Buildings and places are historical records that reveal the creative responses of individuals and society towards nature, technological advances, and power structures. Architecture is no silent witness to the push and pull of history. It is an accomplice to the development and demise of peoples through time. Its accounts wait to be heard and understood by those willing to listen to the unraveling tale within. Thus, as a product of human genius and even folly, the built environment is never neutral. Understanding the complexities that informed—and continue to shape—the development of the built environment would allow us to learn from the past; and take Philippine Architecture to new possibilities and potentialities today and in the future.

Philippine architecture is richly multifaceted, just as the Filipino nation as a whole is a wealth of diverse cultural, historical, and geographic influences. Due to its geographic location and archipelagic permeability, the Philippines has been a locus of exchange and cross-cultural encounter, producing a multitude of architectural expressions.

As a tangible intersection of various influences, the Philippine built environment has developed its own unique architectural response to the forces of nature, societal movements, and cultural constructs. Thus, to ask if Filipino architecture does exist is moot; rather, the question should be how it came to be. The same applies to the search for a singular Filipino cultural identity devoid of external stimuli. Development is a product of a long and arduous process of encounter, assimilation, and response with various forces at play: fueling the enrichment of knowledge and sensibilities, which in turn inform the built environment.

Thus, we must take a critical look at these different forces that have driven, and continue to drive, the development of Filipino architecture and the built environment. It is through an appraisal of the circumstances—socio-cultural, political, natural, even personal—vis-a-vis our spaces and places, that we get to better appreciate how our built environment, with its rich plurality, has come to be. After which, we may be able to share it with the next generations.

Mactan International Airport Terminal 2, Mactan, Cebu. Contemporary architecture continues to explore the notions of Filipino identity in placemaking, informed by the developments in the local context and its interface with global movements. Arkitekturang PilipinoIn 2020, at the ons et of the pandemic, the UAP Area B put forward the call for architects to be creative problem-solvers in society through its Assembly. Although it was often said that Filipinos were resilient, we rather believed that on our side was GRIT or “tapang ng loob”, which is how we have kept going despite disasters. To be resilient however means to have a vision to bounce back and not merely survive.

Words are cheap, and there is a need to take action after the jam-packed assembly program, from the speakers to their topics. This was how the Beyond Grit national conceptual competition was launched. To prepare for it, a collaboration was further created with the UP Resilience Institute by the setting up of a series of workshops wherein we learned more about design thinking and participatory design as well as the problem tree analysis and the allied topics.

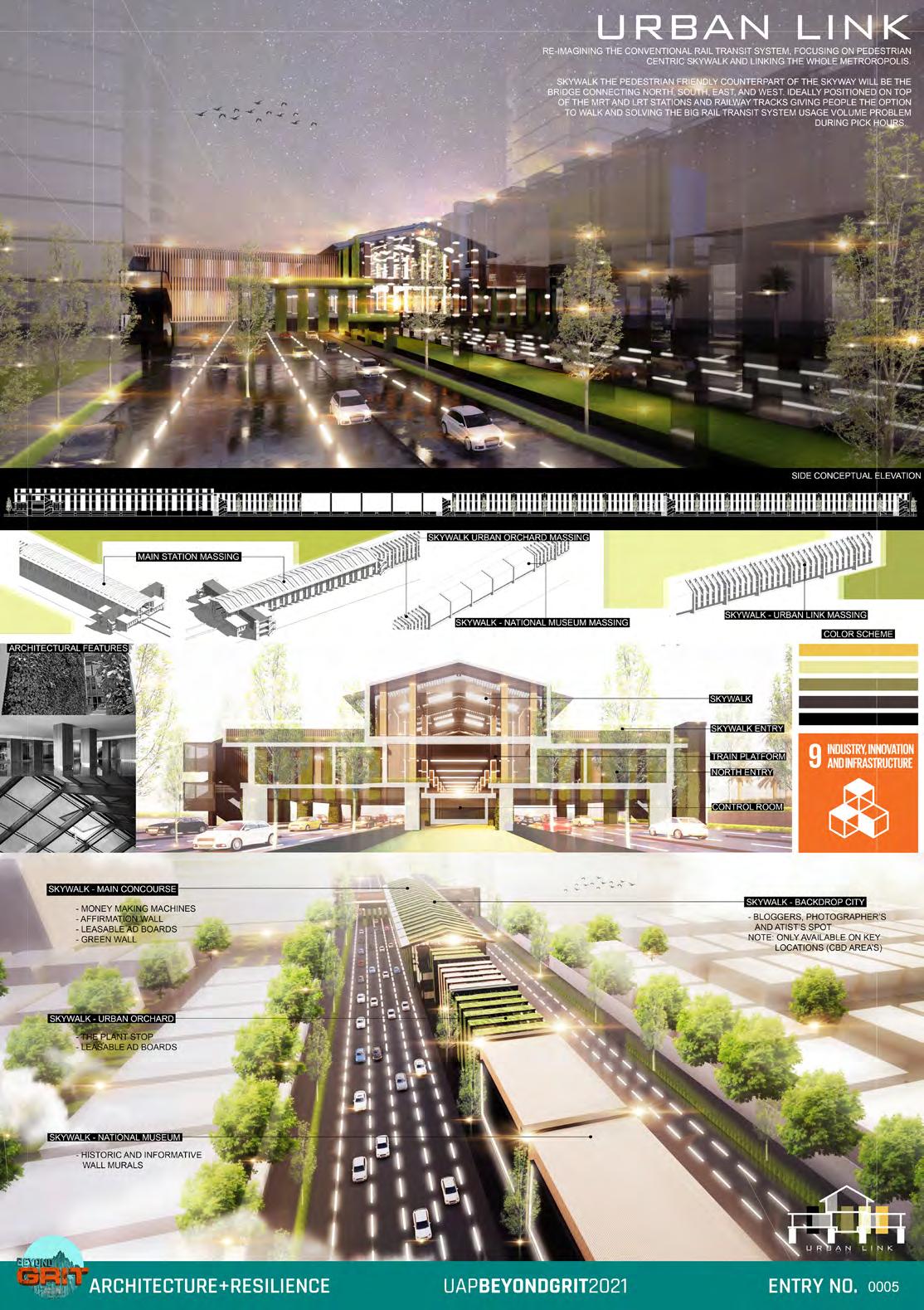

As a result, thirty signed up to join the competition, of which 7 have been finalists. The first prize was awarded to Bryll Edison Par, a member of the United Architects of the Philippines Manila Centrum Chapter and currently an architectural private practitioner, a part-time professor at the National University – Baliwag campus, and a student at the Integrated Graduate Program (Master of Architecture – Urban Design Studio Lab) of the University of the Philippines – Diliman. He proposed the “Urban Link”, which is a mobility design intervention for commuters. Residing in the city allowed Ar. Par to experience the limited provision for comfortable and secured walkable facilities and infrastructure which he surmised stunted the economic growth, produced automobile dependency and an offshoot of problems like pollution and discomfort for the majority of city residents

One of the problems in Metro Manila is traffic congestion, prominent in main avenues and roads in the city. The dependency of people on automobiles has existed since the past centuries with wide road networks developed to help the mobility of the trade of resources for commerce, and at the same time to give comfort to the travel of different status groups. As time went by, more vehicles were manufactured for the growing urban need that adopts this system leading to traffic congestion and chained problems like air and noise pollution. In this case, more road networks got constructed, even though there were very few plans and developments addressing the shortage of pedestrian-friendly infrastructures. The main problem with Metro Manila is the imbalance between vehicle-oriented road networks and pedestrian-friendly walkways. People choose to use private vehicles and public transport because of safety, security, and comfort. It also serves as a status symbol discriminatory to the majority who can’t afford to own cars and other private vehicles.

Eliminating the problem of pedestrians, solving traffic congestion, addressing pollution and climate change, promoting renewable energy, and providing disaster-resilient infrastructure are the key points considered in conceptualizing Urban Link. Urban link is an ambitious design solution for the modern generation of road networks, public transport systems, and pedestrian infrastructure design. It allows people to have the freedom to choose from waiting in long lines in public transport terminals (e.g., MRT, LRT, UV Express services, and Busses) or avoid the depressing traffic-congested road networks.

The big challenge with the conceptualization of Urban Link is the lack of available areas for pedestrian infrastructure development at the ground level. Road networks and sidewalks for pedestrian access in Metro Manila were already permanent. Another challenge in the crafting stage of the design is the flooding in most areas in the city, disabling pedestrian capability to pass during disasters. In addition, safety, security, comfort, and ambiance were concerns in the current condition of pedestrian infrastructures. They are the reason why people choose automobiles and public transport over walking.

The design of the Urban Link revolves around one of the United Nation’s sustainable development goals (SDGs). Industry, innovation, and infrastructure were the driving force of urban growth. Most of the time, we forget that the cause of urban development is the people. We must prioritize them in all our design of infrastructures and incorporate innovative solutions that will give people the power to maximize their full potential and expand the capability of the industry to grow and evolve. Urban Link features Skywalk or the pedestrian-centric counterpart of the Skyway project of the government. The Skywalk is strategically located on top of the MRT and LRT lines and stations with a fully air-conditioned facility, using renewable energy through kinetic tiles or power generated from footsteps. Through this, people can choose from waiting in long lines in public transport stations and the freedom to walk safely in an area equipped with a full-blown security system (e.g., CCTV Camera). Elevating the walkway also addresses the accessibility problem during a typhoon with flooding on the ground level. Several accessory concepts were also included such as the use of green walls, affirmation walls for mental health and positive mindset, and reverse vending machines in all station entrances and exits to give people the ability to get paid from returning and recycling their plastic bottles and caps.

The Skywalk is composed of four main parts. First is the Main Concourse or the entry and exit point of the system. Second is the Urban orchard with vegetations increasing the fresh feel in the area and promoting the plant exchange concept where people can take plants in exchange for another. The third is the museum part with murals explaining history and culture. Last is the Backdrop City or the marketing arm of the Urban Link beside the digital billboards at its exterior, located at concourses of stations of central business districts and high-end shopping malls that aim to attract bloggers and photographers alike to use the facility with provided backdrops done by well-known and new artists. Through social media hashtags and location tags, the Urban Link will reach a wider audience. The Skywalk connects all parts of Metro Manila through a pedestrian system that promotes inclusivity and true resiliency.

By Ar. Gerard Rey Lico, PhD

By Ar. Gerard Rey Lico, PhD

The fate of the Rizal Memorial Sports Complex almost ended tragically in 2016 if not for the vigilance of heritage groups. Nearly destined to face the wrecking ball, the Complex faced the threat of destruction in 2016 when the Local Government of Manila, which owns the property, expressed their interest in transforming the property into a mixed-use development through a partnership with a private company. Through public consultations and stakeholder discussions, the Philippine Sports Commission (PSC), which operates the sprawling sports complex, decided against the sale of the property. The continued existence of the complex was assured in April 2017, when the National Museum of the Philippines and the National Historical Commission of the Philippines jointly declared the Rizal Memorial Sports Complex as a National Historical Landmark and Important Cultural Property, recognizing the significance of the sports complex in the history and heritage of the country. This declaration was secured through the efforts of multisectoral advocacy groups, who lobbied against the property’s sale and conducted the necessary research and documentation to support their cause. Today, the Rizal Memorial Coliseum stands proudly as the product of multi-sectoral efforts to conserve our built heritage.

A Postcard photo of the Rizal Memorial Coliseum, formerly the Rizal Memorial Tennis Stadium which opened in 1940.

The Rizal Memorial Sports Complex was envisioned to fill Manila’s need for a national sporting venue described as “an imposing structure which shall be known the world over for its beauty, its size, and its practical utility”. (R.N. Perley, 1918, 357-58)

Inspired by the prestige of the Osaka City Municipal Playground, which was built to host the 1923 Far Eastern Championship Games, Filipinos were set to embark on building their own. A Playground and Recreation Commission was formed, tasked to “further the cause of athletics in the Philippines”. First among the recommendations of the Commission was “to provide an athletic stadium for Manila to be used as a public playground and athletic field capable of seating 30,000 people.” (Macaraig 1929, 367) This launched the movement to construct a “great national playground to be named Rizal Stadium.” (Laubach 1925, 389) Rizal was a leading figure during the struggle against Spanish colonialism and advocated modernization and Western education.

Designed by Juan Arellano, then Consulting Architect of the Bureau of Public Works, and sitting member of the commission, the plans called for a stadium with a seating capacity of 30,000 at the cost of one million pesos.

Initially slated for completion in time for the 7th Far Eastern Championship Games scheduled in May 1925, the sports complex’s construction lagged due to a lack of funds. By 1927, the 400-meter track and field and two swimming pools were opened for public use. Work on the other structures in the complex dragged on. By 1934, the baseball, swimming, track-football

stadia were ready for use for Manila’s hosting of the 10th Far Eastern Championship Games. However, the coliseum was not finished in time and was completed in 1940.

The complex was designed in the Streamlined Art Deco style, taking cues from nautical and aeronautical forms, coupled with sparing use of geometric patterns executed in precast ornaments and grill works. First opened for public use in 1927, the Swimming Stadium or natatorium has a capacity of 4,000. It contains two swimming pools measuring 50 by 20 meters and another measuring 20 by 6 meters. The first one is used during competitions while the other is primarily for children. The Track-Football stadium has a 400-meter cinder running track and a soccer field. It is provided with a flood lightning system for night events and can seat 30,000 people. The Baseball Stadium has a seating capacity of 15,000 and is provided with an electrically operated concrete scoreboard. Finished in 1940, the Coliseum, originally known as the Tennis Stadium, had a capacity of 10,000 and is the only covered stadium in the Rizal Memorial Field. It contains a shell tennis court and a removable wooden platform for basketball, boxing, wrestling, volleyball, and other sports. It was provided with a boxing ring, Olympic wrestling platforms, glass-banked and steel-framed basketball goal standards, any of which facilities may be set up or dismantled in a few hours. The coliseum also boasted an electric scoreboard and timing device for boxing and basketball, skylights and electric lightning system for day and night events, and a ventilation system which reduces inside temperature and removes vitiated air through the use of large electric blowers.

The Rizal Coliseum before the conservation and rehabilitation, taken in 2019. A large freestanding concrete canopy built in the 1980’s shrouds the lobby in darkness The lobby—dark, decrepit, and drab. Notable are the rounded pylons with a peculiar cut-out shape. This was later found out through archival research to be cylindrical ornamental lamps.In its pre-war heyday, the sports complex was host to a plethora of national and international sporting events. Beyond sports, other events of national importance that happened in the sports complex include the unification of the Nacionalista Party in 1934, the acceptance of Manuel Quezon and Sergio Osmeña as the respective Presidential and Vice-Presidential candidates of the same party for the 1935 elections, to name a few. In the years before the Second World War, the Sports Complex served as the premiere venue for the events of the PAAF, the National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA), the University Athletics Association of the Philippines (UAAP).

In the analysis of Stephan Huebner, the stadium was part of the visual politics of modernity under a colonial power structure, a demonstration of progress through the “blessing of Protestant American modernity.” He asserts that: “…the stadium visually underlined the transformation of the Philippines from a ‘backward’ country into a modern one. Filipino politicians reject colonialism but not Western civilization itself.” (Huebner 2016, 86)

As the country was marching towards independence during the Commonwealth era, Arellano, in his design for the buildings of the Rizal Memorial Sports Complex, turned away from Neoclassicism—which was strongly associated with American colonial rule—and embraced the progressive language of deco streamlining. Streamlining was modernist in inclination, eliminating ornamental excesses to highlight the mechanistically smooth building skin and reverence to the machine. Stylistically and ideologically, the streamlining was an opportunity to distance himself from the classical tradition with the erasure of classical ornaments and simplification of form. In this way, the stylistic departure manifested his rejection of American colonialism with his bold move towards the streamlined aesthetics and rejection of American imperialism.

The 1945 Battle for Liberation witnessed the massive decimation of Manila’s urban built heritage and the irreplaceable treasures of colonial architecture. The complex was part of the final stronghold of the Japanese Imperial Army. It was the site of a decisive

battle between the 12th and 5th cavalry divisions of the American troops weeding out the 2nd naval battalion of Japanese soldiers holding garrison in the concrete structures of the sports complex. As the war came to a bloody end in Intramuros, the sports complex’s concrete shell, sustaining heavy damage, barely survived. Despite the seemingly impossible task to resuscitate war-ravaged Manila, the city rose again, and the rehabilitation of the Rizal Memorial Sports Complex was akin to a phoenix rising from the ashes.

The Philippines became an independent republic in 1946. Amidst the reconstruction and return to normality, the country hosted the 1953 Philippines International Fair in Luneta, which heralded to the world the 500-year progress of the Philippines and its recovery from the war. Participated in by ten foreign countries, this served as a showcase of national spectacle where the Philippines presented itself as a progressive, democratic nation embracing modernity. Concurrently, the reconstruction of the Rizal Memorial Sports Complex was in full swing. This regenesis would give the site a new life and meaning -- taking on a different symbolic mantle. It was to be the bearer of Filipino resilience and post-war recovery.

The culmination of this display of post-war national self-actualization was the country’s hosting of the Second Asian Games in 1954. The event served as the successor to the Far Eastern Championship Games in advocating the Pan-Asian diplomatic relations through sports. While brewing tensions between the democratic and communist nations overshadowed the event, the 2nd Asian Games served as an opportunity for the Philippines to project itself as a new nation of the free world. The Philippines’ hosting of the 1954 Asian Games was the first big international sporting event that the new Republic would undertake in its post-colonial existence.

Owing to its unparalleled capacity as a collection of large venues, the Rizal Sports Complex was host to local, national, and international events. Annual collegiate sporting events of the NCAA and UAAP continued to be held here, along with the games of the Manila Industrial and Commercial Athletic Association (MICAA), which was the forerunner of today’s Philippine Basketball Association (PBA).

Other non-sporting events have also found a home in the Rizal Memorial Sports Complex. The Rizal Coliseum in particular, was the largest indoor venue of the period and was host to many local events and international shows, such as the concert

On the exterior, the color palette was carefully selected by revealing the layers of accretionary paint and archival research. A generous amount of exterior façade lighting highlighted and celebrated the building’s character-defining elements. Lines, planes, ornaments, and curves of the streamlined modern architecture were bathed in the warm glow of LED lights.

In the spirit of Art Deco opulence, the central lobby wall was clad in luxuriant cream-colored travertine, while the base was clad in Rojo Cebuano Philippine marble. Together, they resonated with the original red terrazzo floor, which had a reddish concrete base with cream marble chip inlay.

On the exterior, the color palette was carefully selected by revealing the layers of accretionary paint and archival research. A generous amount of exterior façade lighting highlighted and celebrated the building’s character-defining elements. Lines, planes, ornaments, and curves of the streamlined modern architecture were bathed in the warm glow of LED lights.

In the spirit of Art Deco opulence, the central lobby wall was clad in luxuriant cream-colored travertine, while the base was clad in Rojo Cebuano Philippine marble. Together, they resonated with the original red terrazzo floor, which had a reddish concrete base with cream marble chip inlay.

of Jose Iturbi, exhibition bout of Rocky Marciano, the Holiday on Ice which was an ice-skating performance that premiered on April 29, 1955, and was a charity benefit for the Anti T.B. Society and Boys Town. Numerous other commencement exercises such as those of the Philippine Women’s University and the College of Physical Education, as well as various benefit performances were held at the Coliseum throughout the 1950s.

Rizal Memorial Sports Complex, especially the Rizal Coliseum’s preeminence as the multipurpose venue of Manila and its neighboring towns was unchallenged in subsequent years as it was perhaps the only indoor venue sizeable enough to accommodate a large audience, until the creation of other venues outside the city of Manila, such as the Loyola Center, now known as the Blue Eagle Gym, which opened in 1949, and the Araneta Coliseum which was inaugurated in 1959, both in Quezon City. One of the last major events before its steady decline into the 1970s, was the concert of The Beatles in 1966, which had an audience turnout of 80,000, one of the largest for the band’s concerts.

The Southeast Asian Games (SEA Games), regional counterpart to the Asian Games, paved the way for the Rizal Memorial Sports Complex to again return to the fore with the Philippines’ hosting of the 11th installment of the Games in 1981, and the subsequent hostings of the 16th SEA Games in 1991, and the 23rd SEA Games in 2005, and its counterpart 2005 ASEAN Para Games. As the de facto national stadium, Rizal Memorial Sports Complex had been the go-to venue for the hosting of international sporting events, but it was proving more and more inadequate, as was apparent in the opening and closing ceremonies of the 2005 SEA Games being held at the Quirino Grandstand in Luneta instead. In the years between hostings, the sports complex served as the training grounds for the national athletic teams who represent the country in international sporting events. The prominent games of its original collegiate and professional league residents have since transferred to the newer, better maintained, and far more adequate venues.

Recognizing the 2017 declarations of the National Museum and the National Historical Commission of the Philippines, in April 2019, the Philippine Amusement and Gaming Corporation (PAGCOR) remitted Php 842.5 million to the PSC

for the rehabilitation its facilities for the SEA Games, including 250 million earmarked for the Rizal Memorial Coliseum. This allowed for a much-needed comprehensive rehabilitation of the coliseum, including the installation of a centralized air conditioning system, the installation of new stadium seating, and the total refurbishment of toilet and locker facilities, among others. The author, owing to his prior experience with the works of Juan Arellano, was commissioned as consulting architect for the rehabilitation of the Rizal Memorial Coliseum in the early half of 2019. For the reader to visualize the extent of the building’s deterioration, the building’s condition will be discussed.

Not having undergone a comprehensive renovation since 1954, the Coliseum had deteriorated into a shadow of its former self. The roof was leaking in places, bleachers were rotting; the walls revealed multiple layers of peeling paint. Once ventilated by large machine blowers, these have since broken down; exhaust fans gathering dust. Over the years, minor modifications have been made—wooden mezzanine floors in some rooms added for office space, makeshift partitions, spectator wire fences, concrete flood barriers, and a large, freestanding concrete canopy fronting the façade. The piecemeal changes and haphazard repairs slowly disfigured the iconic art deco character of the building. Over decades of its use as a sporting facility, its poor maintenance resulted in its slow deterioration: with its outdated facilities, dimly lit interiors, and poor ventilation.

With its historico-social context and significance in mind, the interventions were specifically laid-out to highlight the character defining elements of the building and ensure the integrity of the structure. The objective of the rehabilitation was two-fold: first, to upgrade the existing facilities to suit the needs of modern sporting events; and second, to restore the heritage value of the building by returning it to its streamlined deco roots. This entailed comprehensive research on the history and significance of the complex, color studies, defects analysis, and a careful study on the effects of the proposed interventions. Some interventions required a cautious approach, such as the boring of holes in the slab for ducting; and the partial removal of a section of bleachers to make way for a service entrance to the arena.

A FIBA-compliant lighting system was installed at the arena floor to allow for international television coverage of live sporting events. The arena floor served as staging area for various equipment, supplies, and stockpiles during construction. Retractable seating (red seats) were installed to increase capacity while allowing for flexibility. Tubular air-condition ducting was installed—echoing the machine aesthetics of the streamlined modern architecture. DilapidationIn addition to the challenges of rehabilitation, the Philippine Sports Commission designated the Rizal Memorial Coliseum as one of the venues for the 30th Southeast Asian Games slated to open on November 30, 2019. This condensed the rehabilitation time frame from an ideal 12 months, down to four months. Key components and materials had to be sourced from local, readily available suppliers. Imported materials, such as the air-conditioning system had to have a guarantee for timely delivery from their suppliers. Towards the end of the third month, over 400 workers were on-site, working 24/7 in three shifts.

In July 2019, to engage the public in the process of rehabilitation, a fence exhibit was launched along the board-up fence of the site while rehabilitation works were on-going. The exhibit featured archival photographs of the Rizal Memorial Sports Complex, a timeline of its history, and a brief bi-lingual introduction to the complex’s origins and significance. This exhibit was intended to re-introduce the public to the building, generate anticipation for the rehabilitation, and to place government heritage conservation efforts into the public consciousness.

As the rehabilitation commenced, the first priority was to remove all debris, and dismantle all the unnecessary additions that have accrued over the years—light frame partitions, wooden mezzanines, defunct vents and exhaust fans, uncharacteristic gates and metalwork, obsolete seating, and old sporting equipment. The freestanding concrete canopy, which was thought to be built in the 1980s, was demolished as it diminished the aesthetics of the façade and blocked sunlight from entering the main lobby. As they were slated to be replaced to make way for air-conditioning, most of the windows were removed.

By far, the largest component of the rehabilitation was the installation of a centralized air-conditioning system, which is composed of indoor air handling units (AHUs), outdoor air-cooled condensing units (ACCUs), and the air distribution system or (ducting). The installation of the system required rooms to be cleared and repurposed to accommodate AHUs. Wall and slab openings were created to accommodate vents, ducting, and facilitate return airflow.

A steelworker grinds the newly-fabricated gates at the arena space. The destijl-inspired chevron design was adapted from the original gates at the lobbies to achieve a unified, cohesive aesthetic.The installation of the ACCUs required the erection of an independent steel platform—a long, elevated deck along a narrow alley on the side of the Coliseum, hidden from view from the façade. The steel deck serves as a platform for the outdoor condensing units. Its erection proved challenging, as its supports were constrained by the space provided: the narrow alley. The footings of both the Coliseum, and the adjacent badminton hall made the placement of footings for the support difficult. The soil was composed of infill, as the site had formerly been part of a creek. Further limiting the support placement was the design constraint: that the alley had to be passable by delivery trucks and service vehicles.

A solution was arrived at by designing the elongated platform to have only one row of support columns instead of two. This avoided the complex and irregular footing and support configurations. The steel deck was to be cantilevered from the support and reinforced with a diagonal brace. The remaining width of the alley was enough for service vehicles to pass.

To seal the space and prevent the escape of cooled air, existing door, window, and roof openings were sealed or gasketed. The large roof louvers were covered with ribbed pre-painted galvanized steel roof sheets. Metal gates at the lobbies were replaced with glass doors and glass curtain walls. Exhaust fans were removed. Windows were replaced.

Large cylindrical ducts were suspended from the roof trusses, distributing cooled air evenly all throughout the venue. Since the ducts were to be exposed in the interior, a circular profile was selected so that the ducting would be visually compatible with the streamlined moderne style of the building and adhere to the poetry of machine aesthetics.

The rehabilitation required a total overhaul of the electrical and plumbing systems of the building; as well as the introduction of a Fire Detection and Alarm System (FDAS), to enhance the safety of the building users, and to conform to modern building standards and codes. Existing electrical lines, lighting, and panel boards were removed; as the new electrical system was designed to accommodate higher electrical loads, owing to the installation of the air conditioning, and new pumps, water heaters, and lighting systems.

After the removal of the dysfunctional exhaust fans, a copious amount of natural light began to pour into the space for the first time in years.

Care was taken to restore the original terrazzo floor at the lobbies. The floor was sanded, polished, and re-sealed to reveal its natural shine and luster.

The toilets and locker rooms were entirely re-done to rehabilitate the image of the coliseum in the popular imagination.

After the removal of the dysfunctional exhaust fans, a copious amount of natural light began to pour into the space for the first time in years.

Care was taken to restore the original terrazzo floor at the lobbies. The floor was sanded, polished, and re-sealed to reveal its natural shine and luster.

The toilets and locker rooms were entirely re-done to rehabilitate the image of the coliseum in the popular imagination.

An all-new LED sports lighting system was installed, replacing the old metal halide lamps which took several minutes to achieve full illuminance. The new system was brighter, conformed to the standards set by the International Basketball Federation (FIBA), and energy efficient. Emergency lighting was introduced to facilitate orderly exit during power interruptions and emergencies.

The storm drainage system was also redesigned. Investigation into the roof leaks pointed to the insufficient drainage from the roof gutters as the cause. Roof drainage was organized and improved by the installation of a system of downspouts, catchment basins, and drainage lines. Likewise, new clean water and sanitary lines were installed to complement the new configuration of toilet and shower facilities. A new water cistern and septic tank were constructed to meet the new demand. To comply with the requirements of the Fire Code, a new FDAS was installed, which includes sprinklers, dry standpipes, and fire hose reels.

The architectural requirements revolve around conserving the heritage value of the building and restoring its art deco character. Character-defining elements—the lobbies, the façade, grillwork, and terrazzo flooring were identified to be conserved, while new spaces such as toilets, showers, and locker rooms, were to be treated in a modern interpretation of art deco.

As rehabilitation work began, color studies were undertaken to determine the color palette of the building from different periods. The color palette selected by the client was a selection of greys and whites—which could be seen from pre-war archival photographs and videos of the complex. The grey palette provided subtlety and nuance, while highlighting the decorative elements without appearing garish. The painting of the façade was carefully matched from archival photos, taking care to be faithful to the original design, as it forms the most iconic and recognizable part of the building.

Special attention was given to the design of the lobby, which had most of the original art deco lauanit ceiling intact. The ceiling was treated for termite control, and portions of it were repaired. The terrazzo flooring was restored, polished to a smooth finish. As the layers of paint were stripped

off, a layer of scagliola or faux marble was uncovered. It must be noted that one of the key principles of art deco is opulence. Perhaps due to budgetary or time constraints, natural marble was not installed during the Coliseum’s construction in the 1930s. Unfortunately, the scagliola was damaged. It had some chipping and missing fragments. Time constraints did not allow for a careful recreation of the technique used to facilitate its restoration. It was decided that this would be concealed with natural stone slabs. This would serve as an “upgrade” from the faux-marbling, and would serve as a protective layer for the time being until the technique to repair the scagliola could be found. Two large porthole windows were uncovered at the lobby, sealed off in concrete. This was “re-discovered” from archival photographs, which showed them prominently. They were subsequently restored to bring back the streamlined modern character of the lobby.

The original grillwork of the building was given proper care. Alterations were removed, and damaged portions were repaired. New spectator gates at the arena level were fabricated, deriving their design from the original gates at the lobbies. Interior lighting at the lobbies and corridors was designed to exude opulence and reflect the geometricism of art deco. Missing art deco lighting at the columns of the main lobby entrance and the two road-facing side lobby entrances were custom-fabricated using fiberglass and brass strips to recreate their original design based on archival photographs and postcards. Warm lights and increased luminance on the interiors had a transformative effect on the spaces, visually enlarging them while enhancing the luxuriant aesthetics of art deco.

As the lobby’s centerpiece, a large brass emblem was installed to welcome guests, to serve as a backdrop for selfies, and to underscore the character of the building. An art-deco inspired wayfinding and navigation system—a necessity in modern sporting venues—was designed to complement the new configuration of the building, so that guests could find their way to the restrooms, and to their seats. To conceal the new downspouts installed and reduce its visual impact, metal corbels were installed at the top of the downspouts, deriving from the concrete corbels at the base of the metal flagpoles.

As the opening of the SEA Games approached, media coverage intensified, focusing on the readiness of the

Completed in time for the 30th Southeast Asian Games, the coliseum reopened on November 30 for the Gymnastics event, where Filipino athlete Carlos Yulo won a gold medal. Spectators are re-introduced to the newly-rehabilitated coliseum, basking in the light, comfortable in the new seats and air-conditioning, and with all-eyes on the game.organizers and venues to host the event. Concerned that the venues would not be completed in time, the media aired footage of the on-going rehabilitation projects at the Rizal Memorial Sports Complex and at the PhilSports Complex.

Several incidents during the run-up to the games— athlete’s delayed check-ins at the hotel, the lack of transportation to the venues, insufficient provisions for food and water, and frustrating unpaid volunteer work—had put the Philippine Sports Commission (PSC), and the Philippine SEA Games Organizational Committee (PHISGOC) under flak. Senator Franklin Drilon questioned the cost of the cauldron to be lit for the games, stating Php 55 million is an extravagance that is so unnecessary, and somebody had to answer for this… A classroom costs P1 million, so we could have built 56 classrooms if the money of the people was not abused.

Citing that without concrete post-Games plans for the facilities, the new and rehabilitated venues could turn into white elephants.

As the Rizal Memorial Coliseum transformed through its rehabilitation, sports officials, the media, and the general public began to take notice. Article after article, news reports sprung up, praising the on-going rehabilitation. On social media, posts about the Rizal Memorial Coliseum went viral. The story of the transformation of the Coliseum was a much-needed bit of good news for the beleaguered Sports Commission. The coliseum re-opened on December 1, 2019, hosting the Gymnastics event with an attendance of about 3,000 people. On its opening day, 19-year-old Filipino gymnast Carlos Yulo clinched the gold medal, besting other ASEAN athletes for the prize; marking the triumphant revival of the Rizal Memorial Coliseum: a testament to Filipino excellence.

The Rizal Memorial Sports Complex demonstrates Filipino skill, ability, and achievement. Owing its design to Juan Arellano, the sports complex’s architecture demonstrated that the Philippines was finally ready for its long-awaited independence. With its rehabilitation, its continued role in international soft diplomacy, pop culture, and sportive camaraderie are ensured. Coming full circle, the Stadium’s own cathartic rehabilitation signals its own rebirth as an

“Tabo”- a vernacular term more recognized in the provinces, is a local Market Day held weekly in the town center bustling with farm produce and people who are out to market in an open area setting called the “Taboan”. The activity creates social encounters and build relationships among the “suki” which makes the experience more meaningful and special. This very experience is what the architect attempts to create amongst the building users and thus, inspired the core concept of the “Poblacion Market Central”, also known as PMC.

Nestled the city center, PMC stands prominent with its industrial-style façade, bare concrete finishes and exposed structural elements that reflect the simplicity of a traditional “Taboan”. Due to its prime location where the property value is very high, every square inch of the lot area must be fully utilized to its highest potential. A lower ground floor was therefore provided and planned to house the main building utilities, as well as ensure that the ratio of parking space requirements- which posed as one of the major design challenges, is met. This allowed for the allotment of all the upper floors for rentable commercial units. With carefulplanning and a series of consultations, the designers were also able to provide architectural and engineering solutions for possible flood problems at the lower ground floor.

Occupying the main ground floor are mainly restaurants and antique shops. Slightly elevated from the street level, the main ground floor creates a sense of separation from the busy street traffic and the sidewalk. The second floorhouses small retail shops of jewelries and souvenir items- all highlighting the good quality of Mindanaoan craftsmanship. Service shops like banks, dental clinics and salons are also provided to complete the customers’basic needs and leisure experience.

Like the “Taboan” in rural areas, the project uses an energy-efficient and cost-effective approach that minimizes electrical load by harnessing natural light and ventilation. The monitor roof of the building is equipped with industrial fans that draw out hot air, allowing continuous fresh air to continually flow through the hallways and other common spaces of the building. Several studies were conducted by the engineers for various ways to achieve a comfortable microclimate for the users without using conventional air conditioning system. This also made the spaces safer in this pandemic period of the Covid-19 virus.

Main Entry Stair Poblacion Market Central, Food HallAdditional energy efficient measures such as LED lights, water-saving toilet fixtures, and rainwater harvesting were also implemented to improve the sustainability of the project.

For lower maintenance cost, the building has minimal applied finishes. Bare concrete walls and columns, exposed slab soffits, visible utilities and polished floor dominate the general look of the structure. Accent metal works with green creeper and landscaping were also implemented to soften the overall structure and act to filter the harsh sun.

Aside from the rich local products that contrast with the simple exposed concrete structure of the building, colorful architectural appliqués were incorporated to make the building livelier and fuller of character. Traditional patterns from the different tribes of Mindanao inspired the ethno-modern graphical designs highlighted on the metal works, columns, and most of the interior spaces. Murals painted by local artists expressing the beauty of the city also adorn the interiors. The PMC Food Hall, designed in collaboration with DDC Architectural Studio, also reflects the vibrant and festive culture of Mindanao.

Set to be Davao’s next dining, shopping and lifestyle destination, PMC will become the new home of Aldevinco Shopping Center, one of Davao’s finest Commercial Development with a history spanning over 50 years. The owner, Alsons Dev, aims to continue the legacy of promoting local and Mindanao culture, heritage and identity as well as taking pride to the third-generation shop owners of Aldevinco Shopping Center for the continuous support over the past few decades.

PMC will also highlight wide selections of local foods that are carefully curated in a fun and stimulating ambiance. Through this, PMC aims to incorporate the rich history and traditions of Mindanao into the modern and contemporary culture that we have today.

View of the elevator and stairs from the second floor Ground floor atrium area Second floor hallway during the Mindanao Art 2021

Project Name

Year Completed