Titanium for reliable stability and space maintenance

Titanium for reliable stability and space maintenance

Precise patient-specific

3-D printing

Fully microstructured surface protects from tissue ingrowth

Titanium for reliable stability and space maintenance

Less surgery time due to perfect fit without shape adaptation

Precise patient-specific

3-D printing

Less surgery time due to perfect fit without shape adaptation

Calculation of augmentation volume (optional)

”I have been using the new Yxoss with a dense structure for the last 2 years and I can state that they are very effective and predictable devices for horizontal and vertical ridge augmentation. When associated with 70% of autogenous bone chips and 30% of DBBM their efficacy is comparable withthe one of traditional PTFE non-resorbable membranes, but much easier and faster to be installed.“

Prof. Massimo Simion

”I have been using the new Yxoss with a dense structure for the last 2 years and I can state that they are very effective and predictable devices for horizontal and vertical ridge augmentation. When associated with 70% of autogenous bone chips and 30% of DBBM their efficacy is comparable withthe one of traditional PTFE non-resorbable membranes, but much easier and faster to be installed.

Integrated implant positioning (optional)

Calculation of augmentation volume (optional)

Integrated implant positioning (optional)

Head-to-head comparison as assessed by Dr. Seiler and Dr. Ronda

Head-to-head comparison as assessed by Dr. Seiler and Dr. Ronda

Prof. Massimo Simion

Head-to-head comparison as assessed by Dr. Seiler and Dr. Ronda

The Australasian

Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery is the official scientific journal of the Australian and New Zealand Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons

Aim and Scope

The Australasian Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery is the premier forum for the exchange of information for new and significant research in oral and maxillofacial surgery, promoting the surgical discipline in the Oceanic region.

Oceania comprises 19 countries, spread over one-sixth of the globe, but with Australia and New Zealand being the dominant developed countries.

The Journal comprises peer-reviewed scientific reports, reviews, case reports of rare and unusual conditions, and perspectives; all of value for continuing professional development.

Information for prospective authors, including author guidelines, publication ethics, malpractice statements and patient consent forms are available for download from the Australian and New Zealand Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons homepage. All correspondence with the Editor is via editorajoms@anzaoms.org

Advertising Information

The Australasian Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery accepts paid advertisements from companies involved with the surgical discipline. For information on advertising guidelines and rates contact Ms Belinda Mellowes, Executive Officer, Australian and New Zealand Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons: eo@anzaoms.org Submit advertisements to ajoms@anzaoms.org

Disclaimer

The Australasian Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Editors and Editorial Board cannot be held responsible for error or consequence arising from the information contained in the Journal. The views and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian and New Zealand Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons, AJOMS Editor or Editorial Board. Neither does publication of advertisements constitute any endorsement of the products advertised. © 2025 ANZAOMS

Alastair Goss

• Emeritus Professor of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, The University of Adelaide

• Emeritus Consultant Surgeon, The Royal Adelaide Hospital Adelaide, SA, Australia

Andrew Heggie, AM

• Clinical Professor, Department of Paediatrics, The University of Melbourne

• Senior Consultant Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon, Royal Children’s Hospital of Melbourne Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Alexander Bobinskas

• Unit Director, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, The Canberra Hospital

• Associate Professor, School of Medicine, Australian National University Canberra, ACT, Australia

Website and Distribution

Belinda Mellowes

• Executive Officer, Australian and New Zealand Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons Sydney, NSW, Australia

AMPCo Production Editors

Laura Teruel

Kate Steyn

AMPCo Graphic Design

Peter Humphries

Catherine Offler

• Administrative Assistant to the Editor Adelaide, SA, Australia

Business Manager

Dieter Gebauer

• Senior Consultant in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Royal Perth Hospital

• Clinical Associate Professor in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, The University of Western Australia

Perth, WA, Australia

Members

Arun Chandu

• Senior Consultant in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Royal Dental Hospital of Melbourne

• Clinical Associate Professor of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, The University of Melbourne

Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Nigel Johnson

• Consultant Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon, Princess Alexandra Hospital

• Senior Lecturer in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, The University of Queensland

Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Paul Sambrook, AM

• Director Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, The Royal Adelaide Hospital

• Senior Lecturer in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, The University of Adelaide

Adelaide, SA, Australia

Darryl Tong

• Professor of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, The University of Otago

• Senior Consultant in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Dunedin Public Hospital

Dunedin, New Zealand

Andrew Watkins

• Supervisor of Training, John Hunter Hospital

• Senior Lecturer, Charles Sturt University Newcastle, NSW, Australia

Ex Officio Members

Jasvir Singh

• President, Australian and New Zealand Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons

• Consultant in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Prince of Wales Hospital

Sydney, NSW, Australia

Patrishia Bordbar

• Immediate Past President, Australian and New Zealand Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons

• Consultant in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, The Royal Children’s Hospital of Melbourne

• IAOMS Executive Representative – Oceania Region

Melbourne, VIC, Australia

John Harrison

• Regional Councillor for Oceania, International Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons

• Senior Consultant in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Auckland City and Middlemore Hospital

Auckland, New Zealand

Jocelyn Shand

• Clinical Associate Professor, Department of Paediatrics, The University of Melbourne

• Chair, Australian and New Zealand Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons Research and Education Foundation

• Head of Section of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, The Royal Children’s Hospital of Melbourne

• Vice President Elect, International Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons

Melbourne, VIC, Australia

56

EDITORIAL

November 2025

Volume 2 | Issue 2

Personal reflections on the progress of team management of oral and oropharyngeal cancer

Wiesenfeld D

60 SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

Retrospective analysis of surgically treated orbital fractures in a Western Australian hospital with a focus on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander outcomes

Hong L, Cooper T, Vujcich N, Ricciardo P and Bobinskas A

66

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

Does the degree of volume change after isolated orbital trauma have a relationship with rates and severity of ocular injury or demographic characteristics?

Narsinh P, Taneja K, Satheakeerthy S and Erasmus J

73 SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

Loss of fat associated with haematoma in the traumatised, reconstructed orbit

Spencer S, Gebauer D, Day R, Collier R and Khadembaschi D

78

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

Hyperbaric oxygen for therapeutic treatment of osteoradionecrosis

Gamage SN, Jensen ED, Cheng A, Goss AN and Sambrook P

84 PERSPECTIVE

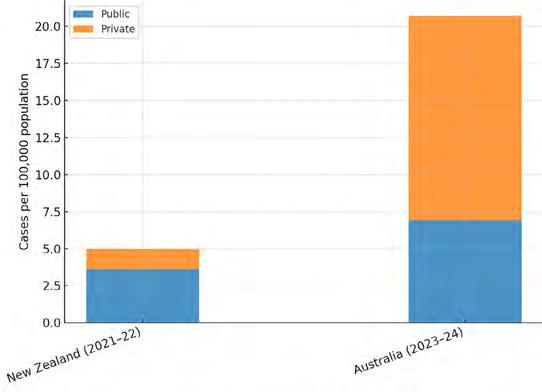

Disparities in orthognathic surgery between Australia and New Zealand

Roberts SL

88 SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

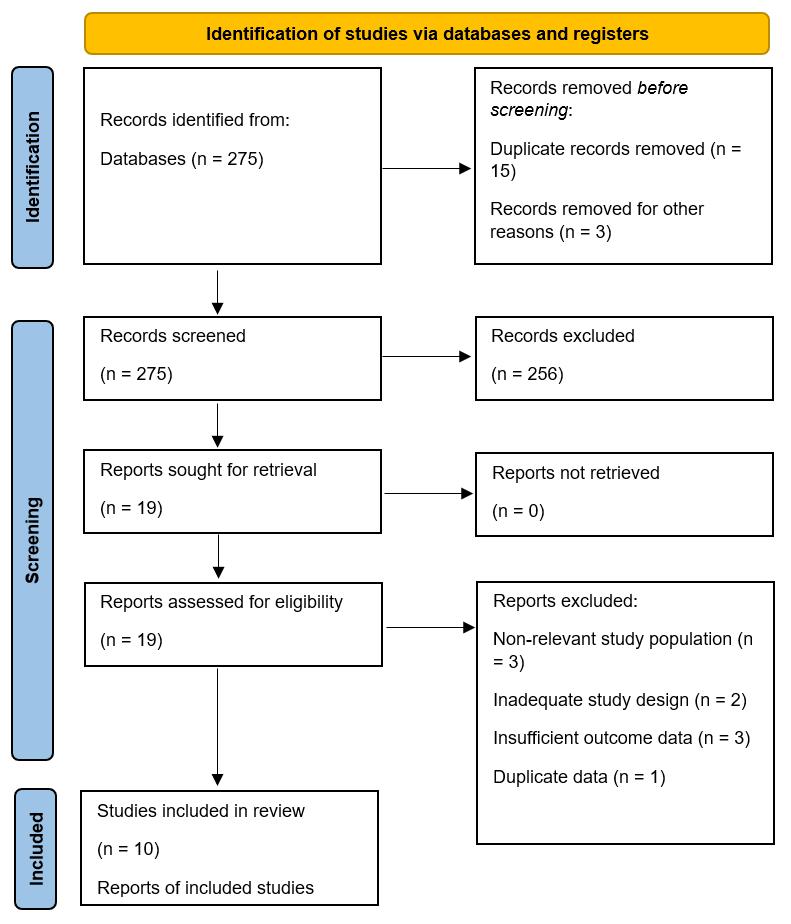

What indication criteria are applied to patients receiving total temporomandibular joint replacement? A systematic review

Mian M, Woliansky M, Sklavos A, Sreedharan S and Kumar R

94 REVIEW ARTICLE

The use of autologous fat grafting in temporomandibular total joint replacement surgery: a systematic review

Liu A , Vu LC, Zhao DF and Dimitroulis G

101 CASE REPORT

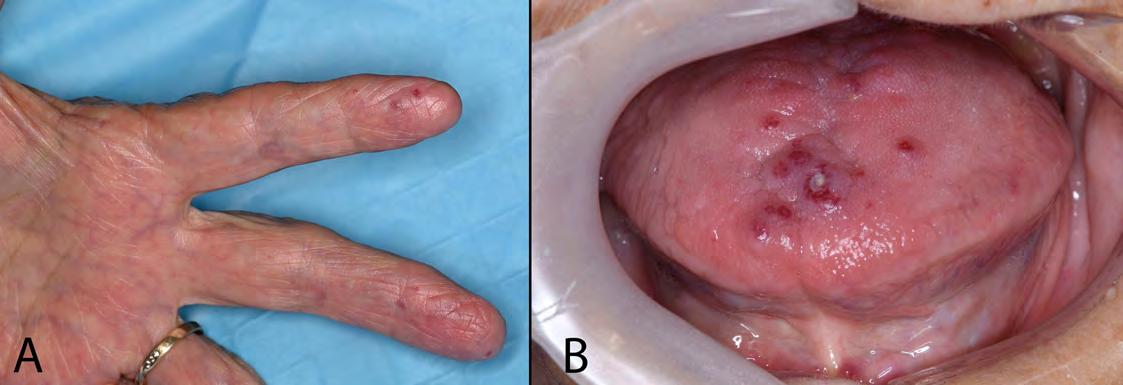

Case report of a life-threatening bleed from oral hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia

van Kuijk M, Singleton C, Ke L and Singh T

Maxillo Facial Imaging (MFI) is Australia's leading dental radiology providersolely focusing on CBCT, OPG and Lat Ceph

The highest quality imaging & workups

Oral & Maxillofacial Radiologists

State-of-the-art imaging technology

Exceptional patient care

Convenient locations

24 hour turn around reporting service*

Oral and oropharyngeal cancer, predominately mucosal squamous cell carcinoma, provide significant challenges to health care worldwide. There is a wide variation in the incidence and prevalence of these cancers, particularly between developed and developing countries. The aetiologies of these cancers include tobacco and alcohol use, and the chewing of betel nut with various additives. Human papilloma virus (HPV) infection is recognised as a sexually transmitted cause of oropharyngeal cancers; it is identified by the presence of P16 protein as a surrogate marker in the formalin-fixed histological specimen.

The management of these cancers requires a highly skilled multidisciplinary team including medical, nursing and allied health participation. Treatment can often be disfiguring and interfere with essential functions including speech and swallowing. There are significant psychological impacts of treatment, which must be considered as part of care. There have been many improvements in patient care and disease management during my professional career over nearly fifty years. A key element of this improvement has been the concept of the multidisciplinary team. Team members all have expertise and novel experiences to enhance care. Developed from their wide-ranging education and life experience, the team must consider and prioritise the needs of the patient, their families and carers.

Common to all the treating specialties are the concepts of risk stratification, the development and acceptance of treatment protocols, striving for early diagnosis and tailoring care for the individual patient based on their unique circumstances and needs.

Dedicated nurses have always been indispensable in the operating theatres; assisting and facilitating surgeons to complete their procedures. In the wards, we have a cohort of expert nurses to provide physical and emotional care to patients to manage their recovery, wound care and initiate the plans for discharge. A new type of nurse has been introduced as the backbone of the team: the cancer nurse coordinator (CNC), who helps the patients and their families through an often-bewildering course of intensive treatment, and medical clinical attendances. The CNC works full-time rather than the three-monthly rotations that junior doctors experience and is therefore more available to assist in the patient’s whole cancer journey.

Major advances have been made in the understanding of radiation biology and the technical aspects of accurately planning and delivering the required doses to tumours while sparing uninvolved

ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC MEETING

6-8 AUGUST 2026 CHRISTCHURCH/OTAUTAHI NEW ZEALAND

The ANZAOMS 2026 Annual Scientific Meeting will be held in the beautiful Otautahi/ Christchurch, New Zealand. The 2026 ASM promises to deliver an engaging and thought-provoking scientific program alongside a dynamic exhibition and social program.

CALL FOR ABSTRACTS OPEN 7 December 2025

OPEN 9 February 2026 CALL FOR ABSTRACTS CLOSE 23 March 2026

PROGRAM RELEASED 11 May 2026

BIRD CLOSES 8 June 2026 ANZAOMS 2026 ASM 6 - 8 August 2026

tissues, thus reducing treatment-related morbidity and improving the chances of control. Included in these advances are intensity modulated radiation therapy, volumetric modulated arc therapy, and concurrent treatment with chemotherapy. The indications and protocols for adjuvant treatment, either radiation alone or concurrent chemoradiation are well documented and accepted internationally. Palliative radiotherapy is a versatile low morbidity treatment option for patients with advanced and incurable disease, either through disease extent or patient frailty. The dose and frequency provided can be modified to suit the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status scale.

Concepts of medical oncology in the management of oral and oropharyngeal cancers have changed dramatically with the inception of immunotherapy. Diligent controlled multicentre prospective studies and clinical trials are showing promising results in both the neoadjuvant and locally advanced inoperable cohorts with mucosal head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. The role of concurrent chemoradiation protocols using platinum-based chemotherapy is well established and accepted in the adjuvant setting with standardised case selection and protocols.

Standardised pathology reporting for head and neck cancer has led to improved risk stratification, prognostication, guidance for the need of elective neck dissection and selection of adjuvant therapy. Factors to be considered are disease clearance margins, depth of invasion, perineural and lymphovascular invasion within the primary tumour and evidence of extranodal extension from the neck dissection specimen. The evidence of HPV association of oropharyngeal cancers using the surrogate P16 protein has a significant bearing on treatment de-escalation and prognosis for these patients.

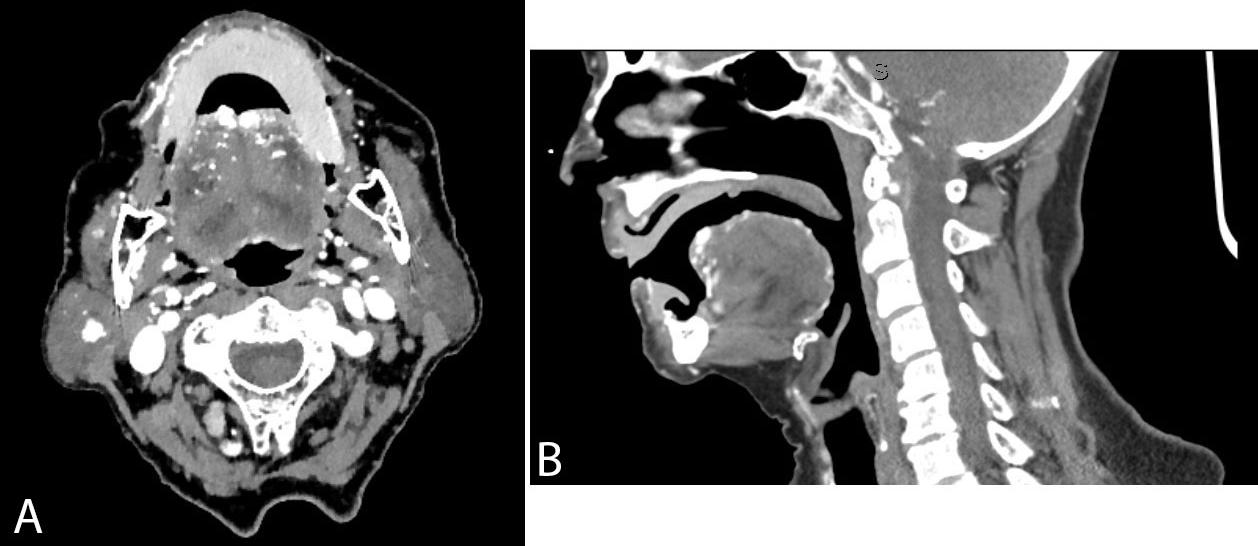

Computer tomography (CT) imaging, preferably with contrast, is essential for both pre-operative assessment of the neck and chest and ongoing surveillance. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), especially with enhancement, aids significantly in soft tissue and bone marrow assessment and is very useful for surveillance of the neck. Ultrasound can be used to guide fine needle or core biopsy of nodal disease and is helpful for assessing the tumour thickness of tongue and other soft tissue lesions.

Positron emission tomography (PET), often combined with CT scans, has revolutionised the assessment of metastatic, especially nodal, disease in head and neck cancer care and can be used for surveillance as well as pre-treatment staging.

“Early diagnosis saves lives” is more than a slogan. All involved in oral cancer care know that small tumours are easier to manage than advanced stage tumours. Education for general medical and dental practitioners in oral cancer diagnosis is essential to improve patient outcomes, equally community education is vital so that patients can recognise that a persistent ulcer or sore in your mouth needs attention. Community awareness has been of great assistance with skin and bowel cancer diagnosis as well as smoking reduction campaigns. Acknowledging that skin and bowel cancer are more common than oral cancers, we still need to increase awareness at the national and local levels; including photographs on cigarette packets is a start but not nearly enough.

The role of HPV is widely accepted in the development of oropharyngeal cancer, as well as genital and anal cancers. Support of HPV vaccination for young people before commencing sexual activity

will help reduce the incidence of HPV-related cancers and possibly eradicate this cancer. It is predicted that HPV-related cancers in all sites will disappear in the next 30 years.

Advances in diagnostic imaging and staging have led to improvements in our understanding of the anatomical requirements for complete resection of the tumour with clear margins. The availability of skilled reconstructive surgeons with advanced techniques for both reconstruction and rehabilitation have allowed for more extensive excisions when required, and for better functional and aesthetic rehabilitation. Modern surgical techniques combined with virtual surgical planning allow for increased collaboration between ablative and reconstructive surgeons to achieve functional results using free tissue transfer that were not previously considered possible, including dental rehabilitation. Despite current advances, patients still face the challenges of interference with speech, swallowing and deformity when they present with advanced disease. Neoadjuvant immunotherapy may be a future opportunity for us to reduce the morbidity and improve aesthetic outcomes of surgically excising advanced tumours.

We have active allied health teams that support our endeavours to manage patients. Speech pathologists and dietitians collaborate to manage feeding, especially when long term difficulty with swallowing is anticipated. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) feeding is appropriate for medium and long term feeding challenges when safe swallowing is affected by the tumour, its removal or radiotherapy. Pre-operative PEG feeding can also be used to assist patients who present as malnourished to improve their recovery after treatment. Clinical psychologists and social workers play a major role in assessing patient suitability for proposed treatment and assisting them to deal with the challenges that major surgery and prolonged hospitalisation present. The clinical psychologist can also assist

with long term survivorship issues. Patient support groups have been established by hospitals and community organisations to assist patients through their lived cancer experience and provide for self-help opportunities through sharing their experiences with other cancer survivors who face similar problems.

The complexity and availability of treatment for patients with oral cancer have changed and expanded over the course of my clinical career. Treatment options and success rates have improved. Patterns of disease and aetiology have changed with a reduction of smoking in the community, the adoption of habits from other countries through migration and the recognition of a growing cohort of non-smoking, non-alcohol drinking females who develop non-HPV-related oral tongue cancer.

June 2025

David Wiesenfeld AM

Deputy

Editor AJOMS

Professor David Wiesenfeld AM played a key role as Deputy Editor in the foundation of the Australasian Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery (AJOMS). His incisive reviews of submitted papers helped establish the high scientific level of AJOMS. His contributions will be missed, and we wish him all the best in his retirement. We are pleased to announce that Dr Alexander Bobinskas has joined Professor Andrew Heggie AM as a second Deputy Editor of AJOMS

Alastair Goss

Editor-in-Chief AJOMS

Author contributions

David Wiesenfeld AM: Conceptualization, investigation, original draft, reviewing and editing.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares that they have no conflicts of interest.

doi: 10.63717/2025.MS0053

Surgical Training

Advanced workshops, complex case discussions and cu ing-edge implant techniques.

Practical Perks Community

Priority access to AOMI events and exclusive local study clubs for surgeons only.

Professional Status & Leadership

Faculty tracks, leadership roles and the prestige of belonging to a surgeons only global network.

Member Value 20% member discount on AOMI education programs

Hong L (BSci, MD)1; Cooper T (BDSc, MBBS, MPhil, FRACDS(OMS))2,3; Vujcich N (BDSc, MBBS, FRACDS(OMS))2; Ricciardo P (BDSc, MBBS, FRACDS(OMS))2; Bobinskas A (BOH(DentSci), GradDipDent, MBBS, FRACDS(OMS), FRCS(OMFS))4

Orbital fractures are a frequently encountered type of maxillofacial injury, constituting up to 25% of isolated facial fractures.1 Epidemiological investigation across Asia, Europe and America consistently reveal that individuals sustaining orbital floor fractures are predominantly young males.2-6 From an Australian perspective, orbital fractures in Indigenous patients have only been studied as a subset of broader maxillofacial or ocular injury studies.7,8 Although these reports provide satisfactory case numbers, they lack comprehensive information about patient demographics and do not delve into detailed analyses of orbital fracture presentations.

It is estimated that there are over 980 000 Indigenous Australians in Australia, representing 3.8% of the total Australian population. Of these, approximately 120 000 live in Western Australia (WA), comprising 4.4% of the total WA population.9 Prior literature has highlighted a higher proportion of head injuries and mandibular fractures in the Indigenous Australian population.10-12 However, no datasets have focused on orbital fractures.

This study aims to review the epidemiology of orbital fractures and identify trends in patients undergoing orbital reconstruction in WA, with a specific emphasis on identifying potential differences between the Indigenous Australian and non-Indigenous populations.

A retrospective review was conducted on all cases of orbital reconstruction performed by the oral and maxillofacial unit at the

1Intensive Care Unit, Royal Perth Hospital, Perth, WA, Australia; 2Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Royal Perth Hospital, Perth, WA, Australia; 3Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Fiona Stanley Hospital, Perth, WA, Australia; 4Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Canberra Hospital, Canberra, ACT, Australia. Corresponding author: Lewis Hong ✉ lewish1807@gmail.com | doi: 10.63717/2025.MS0042

Purpose: Orbital fractures are a common type of maxillofacial injury, accounting for up to 25% of isolated facial fractures. This retrospective study examines orbital fractures requiring reconstruction in Western Australia (WA) over a five-year period, with a focus on differences between Indigenous Australians (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, hereafter referred to as Indigenous Australians) and non-Indigenous populations.

Methods: Data from 142 patients who had undergone orbital reconstruction at a tertiary trauma centre were reviewed, revealing that young males were predominantly impacted, with a median age of 33 years. Assault emerged as the leading cause of injury, especially among Indigenous Australians, who represented 17% of the study population, higher than their 4.4% representation in the WA population.

Results: Key findings include a significantly higher incidence of assault-related orbital fractures among Indigenous Australians (83% v 47%; P < 0.01) and higher rates of “lost to follow-up” in the Indigenous Australian group (46% v 24%; P = 0.04). No significant differences were observed in the timing of surgery, injury severity, or post-surgical outcomes between Indigenous Australians and non-Indigenous patients. The study underscores the need for targeted prevention strategies, such as reducing assault rates, and improving follow-up compliance through potential interventions that may include telehealth, enhanced health education for local medical officers and involvement of Aboriginal liaison officers.

Conclusions: These findings highlight the disparities in orbital fracture aetiology and follow-up care between Indigenous Australians and non-Indigenous populations. Further research is recommended to validate these findings and explore interventions.

Keywords: trauma | oral and maxillofacial surgery | orbital fixation | orbital fracture

* Indicates statistical significance for a P value less than 0.05.

Royal Perth Hospital (RPH), between January 2016 and December 2020. The study protocol was approved by the RPH Human Research Ethics Committee and the Aboriginal Health Council Ethics Committee (RGS0000005043).

Using the unique patient identifier, demographic attributes such as self-reported ethnicity, gender, age and residential address were obtained from the electronic patient management system. The paper files of these patients, including outpatient clinic notes, operation records, ward and emergency department notes, and discharge summaries were then reviewed.

The Modified Monash Model was used to determine if a patient came from an urban or rural area. As per the model, a patient was characterised as originating from a rural area if their residential address fell within territories categorised as Modified Monash 2 or higher, with each number above 2 signifying a higher degree of remoteness.13

Presenting signs and symptoms were identified as the latest documented before surgery. Total length of post-operative followup was calculated from day of surgery to the day of last review. A patient was deemed discharged if the outpatient clinic notes had formal documentation saying so, otherwise a patient was noted as ongoing with review. As per hospital policy, patients were categorised as “lost to follow-up” if they did not show up to at least two scheduled follow-up appointments.

Data were processed using Microsoft Excel and, where statistical analysis was performed, either the Fisher Exact Test or two-sample T-test was used with a two-tailed P value of less than 0.05 being deemed as statistically significant.

Table 2. Mechanism of injury and time from injury to surgery

Between January 2016 and December 2020, 142 patients underwent orbital reconstruction at RPH. Of these, 103 were male and 39 were female. Seventy-nine patients came from urban areas, while 54 came from rural areas, and 9 were international residents. In terms of ethnicity, 88 patients were of European descent, and there were 24 patients of Indigenous Australian heritage. The median age at the time of injury was 33 years, with 33.1% falling between the ages of 30 and 39 years, and 30.3% between 20 and 29 years (Table 1).

The most prevalent cause of orbital injuries was assault, accounting for 76 cases, followed by motor vehicle accidents and sport/ recreation-related incidents, each with 21 cases. There was no significant difference based on location. Notably, there was a significantly higher incidence of assault as the cause of injury within the Indigenous Australian patient population relative to non-Indigenous patients (83% v 47%; P < 0.01) (Table 2). When accounting for gender, the highest rate of assault as reported cause of injury was seen in Indigenous Australian males (88%) with the second highest seen in Indigenous Australian females (75%) (Table 3).

Most surgeries took place between 8 to 14 days after the injury, which was not significantly different when accounting for location or indigeneity (Table 2). Only 21 cases involved an isolated orbital fracture with no other facial injuries present. In other cases, ocular injuries were found in 75 cases, soft tissue injuries in 59 cases, and other facial fractures in 58 cases (Table 4). Among presenting issues, peri-orbital bruising was most frequently documented, affecting 100 patients, followed by diplopia in 89 patients. Acute vision loss was noted in 18 cases, and gaze restriction in 66 cases (Table 5). There was no significant difference for presenting issues or associated injuries when accounting for location or indigeneity.

Overall median follow-up duration was 49 days. Follow-up duration was significantly higher in the non-Indigenous population compared with the Indigenous Australians, being nearly three times longer (61 v 24 days; P = 0.03) (Table 5). A significantly higher proportion of Indigenous Australian relative to non-Indigenous patients were “lost to follow-up” (46% v 24%; P = 0.04). There were no significant differences in terms of post-operative follow-up duration or rate of “lost to follow-up” based on location. Thirteen patients required revision or removal of hardware after surgery. There was no significant difference for post-surgical outcome between the Indigenous Australian and non-Indigenous populations (Table 5).

This retrospective study aimed to identify the trends in orbital trauma requiring repair over a five-year period in WA, with a particular

emphasis on the Indigenous Australian population. The overall findings mirror previously published results, showing that the highest numbers of these traumatic injuries occur in young to middle-aged males of European descent.1-8 However, Indigenous Australian patients comprised 17% of the study population, which is higher than the overall Indigenous Australian population of 4.4% in WA, suggesting that there may be a potentially higher occurrence of orbital trauma in the Indigenous Australian population.9

Our results support assault being the leading cause of orbital bone fractures, followed by traffic accidents and sports activities. These findings are consistent with several studies, indicating universal trends or a strong association between the mechanism of assault and orbital fractures.2-7 Among the Indigenous Australian patients, there was a significantly higher incidence of assault compared with nonIndigenous individuals.

Oberdan and Finn observed similar trends on assault in Indigenous Australian individuals and identified a higher rate of assault on women in their study on mandibular fractures in Far North Queensland, suggesting a possible link to high rates of interpersonal/ domestic violence.11 Our study found no significant difference in incidence of assault for Indigenous Australian women when compared with other groups; however, there appears to be higher rates of violence in Indigenous Australian women versus nonIndigenous women in our study, which may not have been adequately captured due to low Indigenous Australian female patient numbers.

The data overall further support the notion that Indigenous Australian individuals are more vulnerable to assault.

No significant differences were noted in the timing of surgery between urban, rural, Indigenous Australian, and non-Indigenous comparisons, indicating adequate accessibility to maxillofacial services. The overall pre-operative findings and associated injuries did not significantly differ when comparing Indigenous Australian to non-Indigenous patients, suggesting that injuries sustained in the Indigenous Australian population are not inherently more severe.

In terms of post-operative follow-up, the rate of being “lost to followup” was significantly higher in the Indigenous Australian population. Location did not seem to be a contributing factor, as the rate of follow-up for rural and urban patients (both Indigenous Australians and non-Indigenous) did not significantly differ. This underscores a disparity in compliance with follow-up for the Indigenous Australian population, emphasising the need for services to address this issue.

In summary, our study illustrates some discrepancies between the Indigenous Australian and non-Indigenous populations concerning orbital floor fractures, in particular the need for improved prevention strategies to mitigate injury, such as reducing rates of assault, and improved follow-up services. One method of reducing rates of assault was described by Dorman and colleagues, where they demonstrated a remarkable reduction in the incidence of ocular trauma in Indigenous communities following the implementation of alcohol management plans in Far North Queensland, which prohibited the possession and consumption of alcohol in most Indigenous communities.14 However, they also rightfully acknowledged that implementing such measures was a potential infringement on civil liberties based on ethnicity.

Implementing health technology, such as telehealth, to enhance compliance with follow-up is a promising approach with well studied benefits both locally in Australia and globally.15-17 However, it is unclear if these benefits would be applicable to orbital trauma, partly due to the importance of, and difficulties in, performing an accurate clinical examination. Such health technologies still require patient compliance in attending appointments to be effective. While proven to be beneficial for rural areas, geographical isolation did not appear to be an issue for our cohort, as indicated by the non-significant differences in rural and urban patient follow-up rates, suggesting that other factors may be influencing follow-up for Indigenous Australian individuals.

Enhanced health education during hospitalisation and in clinic settings regarding the risks of patient-led discharge and the potential benefits of follow-up (including addressing ongoing diplopia with eye exercises or referral to an optometrist for corrective lenses and monitoring visual acuity) may also help with follow-up compliance. Involving relevant allied health staff such as the Aboriginal liaison

officer to aid in this task as well as helping address issues that hinder follow-up could be of benefit. Cheok and colleagues18 have shown routine involvement of an Aboriginal liaison officer within the orthopaedic multidisciplinary team to be effective in reducing the risk of self-discharge in Indigenous patients, with those who selfdischarged doing so only after critical aspects of their care were met.

Providing a guide of concerning symptoms to monitor for in a patient’s discharge summary and having the patient follow-up with their local general practitioner may also be a simple alternative as it leverages the strong patient–clinician relationships that exist at the local level. This is supported by the preference shown by some Indigenous Australian patients who opt for their local Aboriginal medical service over a hospital for assistance.19

Limitations of this study include a small sample size, partially attributed to focusing on operated orbital fractures rather than all fractures. The retrospective nature introduces potential bias due to non-standardised measurement of diplopia (clinician-dependent), possibly leading to intraoperative bias. As there was no standard proforma for assessment, some examination findings may not have been adequately documented. All assessments were conducted by a maxillofacial registrar or higher. A prospective study further investigating this issue would be valuable to validate findings and track trends in response to enhanced use of health technology.

In summary, this retrospective study highlights trends in orbital trauma, underscoring differences between the Indigenous Australian and non-Indigenous populations in WA. Notably, assault remains the predominant cause, with a heightened prevalence observed among Indigenous Australian individuals. Additionally, there is an apparent gap in compliance with post-operative follow-up, particularly among Indigenous Australian individuals. Further research and targeted interventions, particularly within the Indigenous Australian community, such as involving Aboriginal liaison officers or the local general practitioner for follow-up, would be of benefit to improve outcomes for individuals sustaining orbital fractures.

Hong L: Acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, writing –original draft, writing – review and edit.

Cooper T: Conceptualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and edit.

Vujcich N: Writing – review and edit.

Ricciardo P: Writing – review and edit.

Bobinskas A: Writing – review and edit, supervision.

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

This study did not generate any original data that can be shared.

1 Alvi A, Doherty T, Lewen G. Facial fractures and concomitant injuries in trauma patients. Laryngoscope 2003; 113: 102-106.

2 Seifert LB, Mainka T, Herrera-Vizcaino C, et al. Orbital floor fractures: epidemiology and outcomes of 1594 reconstructions. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2022; 48: 1427-1436.

3 Gosau M, Schöneich M, Draenert FG, et al. Retrospective analysis of orbital floor fractures--complications, outcome, and review of literature. Clin Oral Investig 2011; 15: 305-313.

4 Shere JL, Boole JR, Holtel MR, et al. An analysis of 3599 midfacial and 1141 orbital blowout fractures among 4426 United States Army Soldiers, 1980-2000. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004; 130: 164-170.

5 Chi MJ, Ku M, Shin KH, et al. An analysis of 733 surgically treated blowout fractures. Ophthalmologica 2010; 224: 167-175.

6 Chiang E, Saadat LV, Spitz JA, et al. Etiology of orbital fractures at a level I trauma center in a large metropolitan city. Taiwan J Ophthalmol 2016; 6: 26-31.

7 Cabalag MS, Wasiak J, Andrew NE, et al. Epidemiology and management of maxillofacial fractures in an Australian trauma centre. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2014; 67: 183-189.

8 Ashraf G, Arslan J, Crock C, et al. Sports-related ocular injuries at a tertiary eye hospital in Australia: a 5-year retrospective descriptive study. Emerg Med Australas 2022; 34: 794-800.

9 Australian Bureau of Statistics. Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians [website]. Canberra: ABS, 2021 . https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/ people/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples/ estimates-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islanderaustralians/30-june-2021 (viewed Oct 2023).

10 Australian Government Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Hospitalised injury among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people; 2011–12 to 2015–16. AIHW, 2019. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/injury/ hospitalised-injury-among-aboriginal-and-torres-st/ contents/table-of-contents (viewed Oct 2023).

11 Oberdan W, Finn B. Mandibular fractures in Far North Queensland: an ethnic comparison. ANZ J Surg 2007; 77: 73-79.

12 Diab J, Flapper WJ, Moore MH. Facial fractures in Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations of South Australia. J Craniofac Surg 2023; 34: 1207-1211

13 Australian Government Department of Health, Disability and Ageing. Modified Monash Model. Australian Government Department of Health, Disability and

Ageing. https://www.health.gov.au/topics/rural-healthworkforce/classifications/mmm (viewed Oct 2023).

14 Dorman A, O’Hagan S, Gole G. Epidemiology of severe ocular trauma following the implementation of alcohol restrictions in Far North Queensland. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2020; 48: 879-888.

15 Mathew S, Fitts MS, Liddle Z, et al. Telehealth in remote Australia: a supplementary tool or an alternative model of care replacing face-to-face consultations? BMC Health Serv Res 2023; 23: 341.

16 Kichloo A, Albosta M, Dettloff K, et al. Telemedicine, the current COVID-19 pandemic and the future: a narrative review and perspectives moving forward in the USA. Fam Med Community Health 2020; 8: e000530.

17 Gajarawala SN, Pelkowski JN. Telehealth benefits and barriers. J Nurse Pract 2021; 17: 218-221.

18 Cheok T, Berman M, Delaney-Bindahneem R, et al. Closing the health gap in Central Australia: reduction in Indigenous Australian inpatient self-discharge rates following routine collaboration with Aboriginal Health Workers. BMC Health Serv Res 2023; 23: 874.

19 Nolan-Isles D, Macniven R, Hunter K, et al. Enablers and barriers to accessing healthcare services for Aboriginal people in New South Wales, Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18: 3014.

Narsinh P (MBBS, BDS, FRACDS (OMS))1; Taneja K (BMed, BDS)2; Satheakeerthy S (MBBS, MTrauma)3;

Orbital fractures that are commonly seen by oral and maxillofacial surgeons can be associated with a multitude of injuries to surrounding structures, including the globe, brain and cervical spine.1 Severe ocular injuries are estimated to occur in 2.7–13.7% of isolated orbital trauma cases.2 Jamal and colleagues reported a 10% incidence of major or blinding injuries and a 6% rate of traumatic optic neuropathy with zygomaticomaxillary fractures.3 Brown and colleagues found that 17.1% of patients had concurrent globe injuries associated with isolated orbital fractures.4

The burden of orbital trauma can be high, with pooled trauma registry data of 102 887 patients in Germany showing that 11.1% of patients sustained facial trauma.5 Orbital walls are estimated to be fractured in 30–40% of all facial fractures.6,7 Orbital fractures represent onefifth of all facial fractures in New Zealand.8-10 American data showed a 47% increase in orbital fracture presentation over an 11-year period leading to 2017, and that 40% of ocular admissions were due to orbital fractures.11

Clinical parameters as outlined by Burnstine, or visual assessment of fracture size guide the reconstructive surgeon on orbital fracture management.12,13 With access to high quality imaging techniques, three-dimensional (3D) orbital volume measurements are now being calculated to determine orbital volume changes that occur after trauma. Studies have indicated that orbital volume increases by more than 1.62 cm3 are an indication for orbital reconstruction to prevent enophthalmos.14 Studies also indicate that volume measurements have a repeatability of 95%, adding to their validity.15 However, there is no data assessing if there is an association between volume changes after isolated orbital trauma and ocular injuries or other demographic characteristics.

Purpose: This study aims to establish if there is a relationship between the degree of volume change after isolated orbital trauma and the rates and severity of ocular injury or demographic characteristics, which is a topic not previously investigated.

Methods: A retrospective analysis of 109 isolated orbital trauma cases presenting to the maxillofacial surgery department in Christchurch, New Zealand was completed. Ocular injuries and demographic data related to the fractures were analysed against orbital volume changes calculated using OsiriX MD software.

Results: Volume change versus ocular injury analysis was not significant (P = 0.55). The average volume increase in the orbital reconstruction group was 2.17 cm3 versus 1.07 cm3 in the nonoperative group. The total rate of ocular injury was 21.1% with 10.1% sustaining severe injuries.

Conclusions: No association between the degree of volume change after isolated orbital trauma and the rate or severity of ocular injury was found. In this retrospective analysis, 47.7% of the cohort were not formally assessed by ophthalmology, potentially leading to an under-reported incidence of ocular injuries. Findings therefore correlate with those formally assessed by ophthalmology. The severe ocular injury rate of 10.1% is consistent with international literature. Demographic analysis versus volume change showed no significant relationship.

Our study aims to determine if there is a relationship, linear or nonlinear, between the degree of volume change after isolated orbital trauma and the rate and severity of ocular injury. We hypothesise

1Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department, Te Whatu Ora Christchurch Hospital, Christchurch, New Zealand; 2Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department, Auckland Hospital, Auckland, New Zealand; 3Western Health, Melbourne, VIC, Australia.

Corresponding author: Pritesh Narsinh ✉ priteshnarsinh@hotmail.com | doi: 10.63717/2025.MS0045

computed

that after isolated orbital trauma, increased orbital volumes would have lower rates of ocular injury compared with non-displaced fractures or fractures with a volume decrease. If this hypothesis is true, it may aid in streamlining ophthalmology referrals based on imaging, as we may be able to determine fracture patterns in three dimensions associated with higher rates of ocular injury. This is a topic that has not been assessed in the literature. Our secondary aims are to assess if volume changes after isolated orbital trauma have any association to ethnicity, age, mechanism of injury and fracture patterns.

A retrospective analysis of all orbital fractures that presented within the catchment of the Canterbury District Health Board (CDHB), Christchurch, New Zealand from 5 January 2018 to 5 June 2021 was undertaken using the maxillofacial surgery department’s trauma registry.

Mild: no intervention required

Chemosis

Commotio retinae

Traumatic iritis

Traumatic mydriasis

Macular haemorrhage

Iridodialysis

Moderate: non-surgical intervention required or ophthalmic follow-up

Proptosis

Corneal abrasion

Raised intraocular pressure

Ptosis/moderate lid issues requiring non-surgical treatment

Exotropia

Intra-retinal haemorrhage

Iris sphincter tear

Conjunctival laceration

As per the New Zealand Health and Disability Ethics Committees’ requirements for ethical approval, local health board institutional ethical approval was obtained for patient consent, data release and analysis as carried out in the study (approval number: RO21172).

Two hundred and eighty-four patients were identified as having sustained fractures involving orbital walls during the study period. Patients who met the following inclusion criteria were included in the study: (i) patients with isolated orbital fractures either single or multi-walled, (ii) patients aged 10 years and over, and (iii) patients with complete computer tomography (CT) imaging of both orbits. Patients were excluded if they had bilateral orbital fractures or if orbital fractures (either single or multi-walled) were associated with additional facial fractures. Of the 284 patients, 109 patients met the inclusion criteria (38.38% of the initial cohort).

Orbital fractures were subsequently classified using the Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen (AO) classification system into medial wall, orbital floor, orbital roof, lateral wall or combined orbital fractures.

For the 109 patients identified, clinical notes were reviewed and demographic data collected pertaining to patient gender, age, ethnicity, mechanism of injury, side of injury and fracture pattern. The presence of diplopia and ocular injuries sustained was also collected. Ophthalmic examinations were initially carried out by emergency physicians, followed by maxillofacial junior medical officers. A normal ophthalmic examination was defined as normal or symmetrical visual acuity, normal pupillary responses, symmetrical pupillary size, and free range of extraocular muscles. Any presence of orbital trauma resulted in a phone consultation with the ophthalmology department. Abnormal examinations or any concerning features on examination led to a formal ophthalmology review. This pathway of referral was

Severe: vision threatening or requiring surgical management

Orbital compartment syndrome/ lateral canthotomy

Globe rupture

Traumatic optic neuropathy

Retinal detachment

Vitreous haemorrhage

Hyphaemia

Lens dislocation

Iridodialysis/cyclodialysis

Traumatic cataract

Choroid rupture

Entrapment

Table 1. Ocular injuries categorised into mild, moderate and severe

deemed safe and appropriate at our centre but has the potential to under-report the true incidence of ocular injuries, particularly those mild in nature, as not all the patients in the cohort were reviewed by ophthalmology. Those with ocular injuries as determined by ophthalmology had their ocular injuries graded as mild, moderate or severe based on grading systems from American studies by Zhong and colleagues2, and Rossin and colleagues.16 Mild injuries were those requiring no follow-up, moderate injuries those requiring non-surgical intervention or ophthalmology follow-up, and severe injuries being vision-threatening or ocular injuries requiring urgent surgical management. Examples of graded ocular injuries are outlined in Table 1. Patients were categorised based on their most severe injury. We excluded minor ocular signs such as periorbital oedema/ ecchymosis, subconjunctival haemorrhage and infraorbital nerve paraesthesia from the mild injury category. Periorbital lacerations were also excluded.

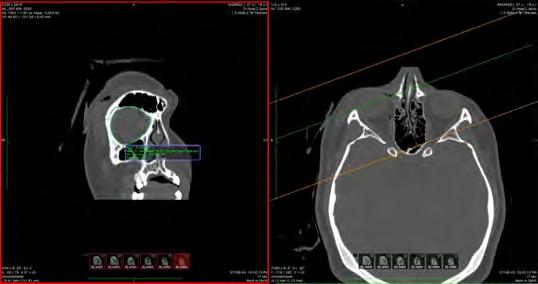

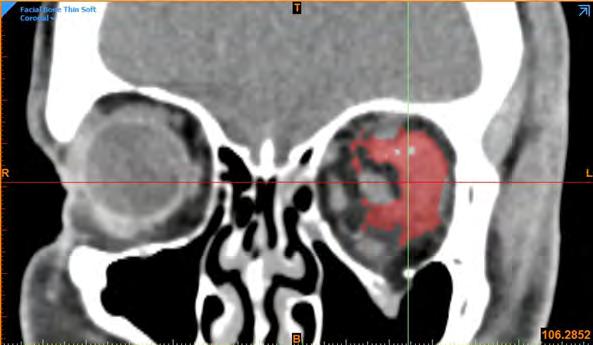

Once the retrospective analysis was completed, we measured the volumes of the left and right orbits for the 109 patients. We used the OsiriX MD software suite.17 Multi-planar reconstruction techniques were used to visualise and assess the orbital volumes. All CT scans were taken using Siemens Somatom force, drive or flash scanners. All fractures were imaged using a non-contrast scanning protocol with tube rotation time of one second, a pitch of 0.8 with 100 kV and 600 mAs. The Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine data were procured for analysis. The axial, coronal and sagittal planes were meticulously aligned with consistent anatomical landmarks to facilitate a multi-planar reconstruction conducive to the precise anatomical segmentation of the orbit, as depicted in Figure 1

Selected landmarks for this alignment included the orbital apex, the superior aspect of the nasolacrimal duct, and the lateral wall of the orbital rim. The volumetric analysis was undertaken to calculate the volume in cubic centimetres (cm3) by multiplying the number of voxels within the region of interest by the volumetric size of each voxel.

Subsequently, a three-dimensional model was generated to provide a visual representation of the volume within the osseous boundaries of the orbit, as depicted in Figure 2

To ensure uniformity in calibration and methodology, a single researcher (KT) was tasked with measuring the left and right orbital dimensions across the entire patient cohort.

Using the measured 3D volumes, orbital volume ratios (OVRs, %) were calculated using the volume of the traumatised orbit/volume of the unaffected orbit × 100.18 OVRs are proposed to allow for a more clinically accurate estimate of volume change after trauma by quantifying the percentage change in orbital volume.19 All 109 patients had volume measurements completed by orbital segmentation. All variables were analysed against volume change of the fractures to see if any association was present after isolated orbital trauma.

Analysis was completed with one-way ANOVA (with post hoc testing) with STATA 17.0 as well as sensitivity analysis using bootstrap resampling methods.

The average OVR for the 109 patients was 107.61%. As per Table 2, combined orbital floor and medial wall fractures had the largest OVR (115.45%), followed by isolated orbital floor fractures (107.3%) and isolated medial wall fractures (105.11%). The average orbital volume

Table 2. Orbital volume ratios (OVR) subclassified to fracture pattern and orbital volume increases in cm3

increase for the cohort was 1.60 cm3. The volume increase was 2.17 cm3 in the operative group versus 1.07 cm3 in the non-operative group. The OVR in the non-operative group was 105.99% and 108.3% in the operative group.

Of the cohort, 52.3% had a formal ophthalmology consultation and examination. The total rate of ocular injury was 21.1% (Table 3). Mild ocular injuries accounted for 6.4% of cases, moderate 4.6% and severe 10.1%. Volume change versus ocular injury analysis was not significant as determined by one-way ANOVA (P = 0.55). There was no appreciable relationship between volume change and ocular injury prevalence or severity. Table 3 outlines ocular injuries subcategorised into mild, moderate and severe. Of the severe isolated injuries listed in Table 3, the retrobulbar haemorrhage and muscle entrapment cases required urgent surgical intervention and the retinal detachment required urgent intraocular surgery.

Table 4 shows the relationship between ocular injuries and percentage orbital volume changes (classified into orbital volume decreases, 0–5% increases, 5–15% increases and greater than 15% increases). The 5–15% volume increase group, which included 45% of the cohort, had the highest ocular injury rates, with a 24.5% total ocular injury rate and a severe ocular injury rate of 14.3%. The lowest ocular injury rate total was in the volume decrease group at 14.3%, closely followed by the greater than 15% increase group at 16.7%. The lowest prevalence of severe ocular injury was in the 0–5% increase group at 3.6%, followed by the greater than 15% increase group at 5.5%.

As shown in Table 3, 56.9% of fractures were left-sided. Isolated orbital floor fractures made up 62.4% of cases, isolated medial wall fractures (23.9%), combined

and medial wall (10.1%), orbital

roof (2.8%) and isolated lateral wall fractures (0.9%). There was a statistically significant difference between groups as determined by one-way ANOVA (P = 0.01). A Tukey post hoc test revealed that volume change was statistically significantly higher in the combined floor and medial wall group compared with the floor alone group (8.14% ± 2.53%; one-way ANOVA, P = 0.015) or the medial wall alone group (10.3% ± 2.81%; one-way ANOVA, P = 0.00). However, there were no statistically significant differences with orbital roof and lateral wall fractures.

As per Table 3, males represented 68.8% of the cohort. The ethnic background was 67.0% New Zealand European, 19.3% Māori, 3.7% Pacific, with other groups making up the remaining 10%. The Indigenous Māori population is over-represented in the study population, as census data for the catchment area from 2018 indicated that Māori represent 9.9% of population, New Zealand Europeans 77.9%, and Pacific 3.8%.20 Volume change versus ethnicity was not significant (one-way ANOVA, P = 0.88). The mean cohort age was 41.4 years, with a range between 10 and 98 years.

The leading mechanism of injury was interpersonal violence (35.8%), followed by falls (24.8%) and sporting injuries (20.2%). Motor vehicle accidents accounted for only 4.6% of isolated orbital fractures. Volume change versus mechanism analysis was not significant (oneway ANOVA, P = 0.43).

Of the fractures, 47.7% underwent operative management with a mean time to surgery of 8.09 days. A one-way ANOVA showed a statistically significant difference in volume change between individuals who underwent surgery versus individuals who were not surgically treated. Post hoc testing revealed that individuals who had surgery had a 3.3% ± 1.5% difference in volume change compared with individuals who did not have surgery (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.03).

Diplopia on presentation occurred in 37.6% of patients, with 56.0% having no diplopia. There was no documentation for 6.4% of patients.

Volume change versus diplopia analysis was not significant (one-way ANOVA, P = 0.55). The rates of diplopia were higher in individuals requiring surgical management with 49.1% of individuals requiring orbital reconstruction having diplopia.

To account for anatomical variation between left and right orbits, a sensitivity analysis using bootstrap resampling methods was performed. This involved generating 1000 individual pseudo-datasets by resampling the original data and recalculating with models under different assumptions of variability between left and right orbits up 1%, 2.5% and 5% (equating to three bootstraps). The conclusions remained consistent across these scenarios, indicating that the observed differences in orbital volume are robust to changes in the assumed side-to-side variation.

The literature has shown that larger volume changes after orbital trauma can lead to sequalae such as enophthalmos.14,18,19 However, it is unknown if volume changes have a relationship with other factors such as ocular injuries or demographic characteristics such as ethnicity, age or mechanism of injury.

We found no statistically significant relationship between the degree of volume change after orbital trauma and the rate or severity of ocular injury. Of the cohort, 47.7% was not formally assessed by ophthalmology, potentially leading to an under-reported incidence of ocular injuries. The maxillofacial surgery department at Canterbury District Health Board has a good working relationship with the ophthalmology department, who, due to departmental constraints, are unable to see every orbital trauma patient for ocular assessment. Patients with a clinically normal eye examination are deemed at low risk of a clinically significant ocular injury and after phone consultation with ophthalmology are followed up by maxillofacial surgery alone. The standard follow-up for non-operative or operatively managed orbital fractures in the maxillofacial surgery department after initial assessment is at one, three and six weeks.

Our study acknowledges that with our retrospective analysis, the true incidence of ocular injury may be underestimated as every patient in the cohort was not assessed by ophthalmology. However, the ocular injuries potentially missed are likely to be mild in nature, as the cohort patients have multiple follow-ups with maxillofacial surgery where any concerning features would lead to an ophthalmologic referral for assessment. The moderate and severe ocular injury rates are less likely to be underestimated, but we acknowledge that the study’s findings relate to a cohort that had a formal ophthalmology examination. Any prospective analysis in this area would require all patients to undergo a formal ophthalmic examination to reduce the chance of an under-reported incidence of ocular injury.

The process of measuring orbital volumes, as well as anatomical variation between left and right orbits, can impact the accuracy of orbital volume measurements (OVMs). OVMs are often conducted by manual segmentation or planimetry, which involves outlining the orbital cavity based on known landmarks on serial slices on CT images.19 The accuracy of OVMs was assessed by comparing volume on CT images versus cadaveric analysis. The average difference between CT image and direct measurements was 0.40 ± 1.13 mL.15 The disadvantages of planimetry include the segmentation being

time intensive and that operator error or bias could occur.19 To ensure uniformity in calibration and methodology, a single researcher was tasked with measuring the left and right orbital dimensions across the entire patient cohort.

Normal anatomical variation also exists in individuals when volume is measured between the left and right orbits. Tandon and colleagues analysed 121 skulls and found an average orbital volume of 26.7 mL with an average difference of 0.8 mL or 2.9% between orbits.21 Statistical analysis using bootstrap resampling methods for our cohort indicated that the observed differences in orbital volume are robust to changes in the assumed side-to-side variation.

Our demographic analysis of gender, age and mechanism of injury had no significant association with volume change after orbital trauma. As anatomical segmentation for 3D volume measurement is time intensive, our cohort consisted of relatively small numbers. We acknowledge that this makes the study prone to Type II errors when analysing our cohorts’ lack of demographic trends. There were, however, consistent trends when comparing to local and international literature.

IPV was the leading cause of injury in our cohort while MVAs accounted for only 4.6% of isolated orbital trauma. These trends are similar to those found in the maxillofacial surgery department in Auckland, New Zealand.9 Over a five-year period of isolated orbital reconstructions, they found 83% of patients were male, 49.5% were aged between 18 and 30 years, IPV accounted for 45.6% of cases with MVAs only representing 2.9% of cases.9

In comparison to international data from New York, USA in those sustaining isolated orbital trauma, males made up 73.7% of the cohort, falls (44.1%) was the most common mechanism followed by IPV (21.5%) and MVA (19.9%).2 An epidemiological analysis of isolated orbital blowouts from Naples, Italy showed an average age of 48 years and MVA accounting for 30% of fractures versus 25% from IPV.6 In comparison to international literature, IPV accounts for a higher rate of isolated orbital trauma in New Zealand while MVA are a significantly lower cause.

Our fracture patterns followed a similar trend as Jung and colleagues who found 59.4% of fractures to be isolated orbital floor, 23.7%

medial wall and 15% had combined floor and medial wall defects in 2415 patients in South Korea.22

Our rates of ocular injury are consistent with previous literature. Severe ocular injuries are estimated to occur in 2.7–13.7% of isolated orbital trauma patients.2 The rate of severe ocular injury in our cohort was 10.1%. There was no appreciable relationship between volume change and ocular injury prevalence or severity. Zhong and colleagues had a 12.5% rate of severe ocular injuries when looking at 186 isolated orbital fracture patients in New York, USA.2 Terrill and colleagues, in Loma Linda, USA, found a 11.2% rate of major/severe ocular injury with a 2.9% rate of globe rupture.23 Our cohort had a 1.83% rate of globe rupture.

In conclusion, we found no association between the degree of volume change after isolated orbital trauma and the rate or severity of ocular injury, a topic not previously investigated. The total ocular injury rate of 21.1% and severe ocular injury rate of 10.1% are consistent with international literature. The main limitation of this retrospective analysis was that 47.7% of the cohort were not formally assessed by ophthalmology, potentially leading to an under-reported incidence of ocular injuries, particularly those mild in nature. Findings therefore correlate with those formally assessed by ophthalmology. Demographic analysis versus volume change showed no significant relationship.

Narsinh P: Lead author, literature review, data collection, data analysis, article write up.

Taneja K: Orbital volume analysis. Satheakeerthy S: Statistical analysis. Erasmus JH: Supervisor.

Abbish Kamalakkannan (BSc (Adv) (Hons I) PHD) for statistical support. This research did not receive funding from any sector; public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

This study did not generate any original data which can be shared.

1 Chow J, Parthasarathi K, Mehanna P, et al. Primary assessment of the patient with orbital fractures should include pupillary response and visual acuity changes to detect occult major ocular injuries. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2018; 76: 2370-2375.

2 Zhong E, Chou TY, Chaleff AJ, et al. Orbital fractures and risk factors for ocular injury. Clin Ophthalmol 2022; 16: 4153-4161.

3 Jamal B, Pfahler S, Lane K, et al. Ophthalmic injuries in patients with zygomaticomaxillary complex fractures requiring surgical repair. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2009; 67: 986-989.

4 Brown MS, Ky W, Lisman RD. Concomitant ocular injuries with orbital fractures. J Craniomaxillofac Trauma 1999; 5: 41-48.

5 Seifert LB, Mainka T, Herrera-Vizcaino C, et al. Orbital floor fractures: epidemiology and outcomes of 1594 reconstructions. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2022; 48: 1427-1436.

6 Troise S, Committeri U, Barone S, et al. Epidemiological analysis of patients with isolated blowout fractures of orbital floor: correlation between demographic characteristics and fracture area. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2024; 52: 334-339.

7 Moore BK, Smit R, Colquhoun A, et al. Maxillofacial fractures at Waikato Hospital, New Zealand: 2004 to 2013. N Z Med J 2015; 128: 96-102.

8 Nguyen E, Lockyer J, Erasmus J, et al. Improved outcomes of orbital reconstruction with intraoperative imaging and rapid prototyping. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2019; 77: 1211-1217.

9 Anand L, Sealey C. Orbital fractures treated in Auckland from 2010-2015: review of patient outcomes. N Z Med J 2017; 130: 21-26.

10 Buchanan J, Colquhoun A, Friedlander L, et al. Maxillofacial fractures at Waikato Hospital, New Zealand: 1989 to 2000. N Z Med J 2005; 118: U1529.

11 Iftikhar M, Canner JK, Hall L, et al. Characteristics of orbital floor fractures in the United States from 2006 to 2017. Ophthalmology 2021; 128: 463-470.

12 Burnstine M. Clinical recommendations for repair of isolated orbital floor fractures: an evidence-based analysis. Ophthalmology 2002; 109: 1207-1210.

13 Hwang K, You SH, Sohn IA. Analysis of orbital bone fractures: a 12-year study of 391 patients. J Craniofac Surg 2009; 20: 1218-1223.

14 Garcia Garcia B, Ferrer AD. Surgical indications of orbital fractures depending on the size of the fault area determined by computed tomography: a systematic review. Rev Esp Cir Oral Maxilofac 2016; 38: 42-48.

15 Diaconu SC, Dreizin D, Uluer M, et al. The validity and reliability of computed tomography orbital volume measurements. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2017; 45: 1552-1557.

16 Rossin EJ, Szypko C, Giese I, et al. Factors associated with increased risk of serious ocular injury in the setting of orbital fracture. JAMA Ophthalmol 2021; 139: 77-83.

17 OsiriX MD [software]. Version 12.0. Pixmeo SARL. http:// www.osirix-viewer.com (viewed Dec 2023).

18 Choi SH, Kang DH, Gu JH. The correlation between the orbital volume ratio and enophthalmos in unoperated blowout fractures. Arch Plast Surg 2016; 43: 518-522.

19 Sentucq C, Schlund M, Bouet B, et al. Overview of tools for the measurement of the orbital volume and their applications to orbital surgery. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2021; 74: 581-591.

20 Health New Zealand Te Whatu Ora. Canterbury Wellbeing Index. https://www.canterburywellbeing.org. nz/our-population/ (viewed Mar 2024).

21 Tandon R, Aljadeff L, Ji S, et al. Anatomic variability of the human orbit. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2020; 78: 782-796.

22 Jung EH, Lee MJ, Cho BJ. The incidence and risk factors of medial and inferior orbital wall fractures in Korea: a nationwide cohort study. J Clin Med 2022; 11: 2306.

23 Terrill SB, You H, Eiseman H, et al. Review of ocular injuries in patients with orbital wall fractures: a 5-year retrospective analysis. Clin Opthalmol 2020; 14: 28372842.

Spencer S (MBBS, BDS)1; Gebauer D (BDSc, MBBS(Hons), FRACDS(OMS), Mast Clin Dent)1; Day R (MBiomedEng, BEng)2; Collier

Khadembaschi D (BDSc, MD, MPhil)3

Orbital reconstruction following facial trauma is a challenge for oral and maxillofacial surgeons. Accurate reconstruction of the bony orbital vault is predictable with careful technique assisted by fine slice computed tomography (CT) imaging and bioengineering adjuncts. The cosmetic and functional outcome is also dependent on the behaviour of the orbital soft tissues, which include fat, ligaments and the extraocular muscles. Symmetrical globe position is the desirable outcome of orbital reconstruction but may not be achieved despite adequate anatomical reconstruction of the bony orbital cavity.

It has been four decades since Bite and colleagues1 described various aetiologies for enophthalmos, each contributing to an imbalance between soft and hard tissue volumes. These aetiologies included displacement of orbital tissue from the bony orbit, tethering of the globe posteriorly by entrapped tissue, fat necrosis with decreased soft tissue volume, and posterior soft tissue fibrosis.

In the era of patient specific implants (PSIs), appreciation of the status of the orbital soft tissues is highly significant. It has been observed that the accuracy of reconstruction of orbital fractures was not significantly associated with the degree of post-operative enophthalmos.2 A review comparing PSIs to conventional implants for the reconstruction of orbital fractures3 failed to show a benefit from using PSIs when assessing post-operative diplopia, enophthalmos and orbital volume. A prospective study by Zimmerer and colleagues4 found that 4.2% of patients with adequate post-traumatic reconstruction of orbital blowout fractures had unfavourable globe positions > 2 mm, and 3.5% had both diplopia and unfavourable globe positions > 2 mm. There appears to be a process that may involve necrosis, fibrosis or atrophy, with or without ligamentous disruption, to account for cases where poorer than expected outcomes are observed.

The aims of this retrospective cohort study were to:

use automated segmental volumetric analysis software to analyse the orbital soft tissue compartments of injured and reconstructed orbits, with intact orbits as a control;

evaluate if there is a fat volume reduction in traumatised, reconstructed orbits compared with intact orbits; and

evaluate if the presence and volume of a haematoma correlates with fat volume change in traumatised, reconstructed orbits.

R (BEng(Hons))2;

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to measure orbital fat volume loss in traumatised reconstructed orbits with haematoma.

Methods: A retrospective cohort study identified subjects with orbital fractures and associated orbital haematoma managed by the oral and maxillofacial surgery service in Western Australia between January 2013 and 2023. Subjects required orbital reconstruction and post-operative computed tomography to proceed to segmental volumetric analysis. Volume change in orbital tissue compartments was analysed using a two-tailed paired t-test. A Pearson correlation test was used to assess whether a linear relationship between haematoma volume and fat volume change existed.

Results: Twenty-two subjects had orbital reconstructions with associated haematoma and underwent segmental volumetric analysis. A statistically significant orbital fat volume reduction of 1.84 mL (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01–2.67 mL, P < 0.001) in reconstructed orbits was observed. Correspondingly, 3.07 mL (95% CI, 2.48–3.66 mL, P < 0.001) less orbital fat volume was observed in reconstructed orbits than their respective contralateral orbits on post-operative scans. No statistically significant correlation between orbital haematoma volume and orbital fat volume change was observed (P = 0.24).

Conclusions: Fractured orbits with associated orbital haematoma demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in orbital fat volume following reconstruction. This reduction in orbital fat volume did not correlate in a statistically significant manner with haematoma volume.

The primary null hypothesis is orbital fat compartment volumes of traumatised, reconstructed orbits with haematoma remain stable and comparable to the contralateral intact orbit. The secondary null hypothesis is there is no correlation between haematoma volume at the time of injury and fat volume change over time.

1Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Royal Perth Hospital, Perth, WA, Australia; 2East Metropolitan Health Service, Perth, WA, Australia; 3Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Fiona Stanley Hospital, Perth, WA, Australia. Corresponding author: Samuel Spencer ✉ sam.r.spencer@gmail.com | doi: 10.63717/2025.MS0054

Keywords: atrophy | fat haematoma | orbital reconstruction

Ethical approval for this retrospective cohort study was granted by the Royal Perth Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (protocol 10.04.23, PRN RGS0000005554) and this research was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Operative orbital fractures at the Fiona Stanley Hospital, Fremantle Hospital and Royal Perth Hospitals were identified retrospectively by reviewing the theatre management systems for orbital reconstruction over a 10-year period from January 2013 to January 2023. Medicare item codes and operative logs maintained by the oral and maxillofacial surgery departments at each site for governance were interrogated. Subjects were excluded if they were under the age of 18 years at the time of operation. CT scans were reviewed for the presence of orbital haematoma. Subjects with operative orbital fractures with orbital haematoma and both diagnostic and post-operative CT scans proceeded to volumetric analysis.

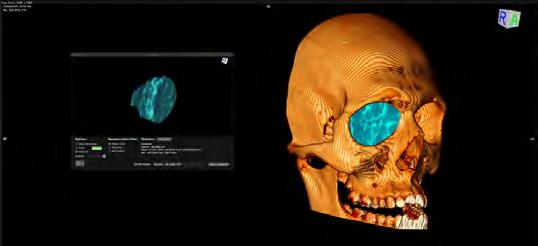

CT data was imported into Materialise Mimics Innovation Suite (Materialise NV, Leuvin, Belgium). A sphere was manually placed to approximate the globe volume by marking three points on the globe and adjusting the sphere for size and position in three planes. The orbital rim anatomy was demarcated with the spline function. The manual identification of these landmarks was found to have good intra-observer and inter-observer reproducibility when tested on a sample of cases. Custom python scripts were used to isolate the orbital volume. The bony vault was delineated using an automated wrapping function, with parameters to capture herniated soft tissue and close small defects, including fissures and foramina, in the bony orbit. The anterior orbit was closed off with a linear wrap across the orbital rim. The volume within the wrapped bony vault and orbital rim after subtracting the globe was deemed the orbital volume (Figure 1). Using the contralateral intact orbit as a control allowed for the titration of orbital volumes over serial scans, ensuring any variation associated with CT protocol was minimised.

The various orbital tissue components of fat, muscle, blood and air were intersected by Mimics software using selected Hounsfield

Unit thresholds (“masks”) to allow automated segmental volumetric analysis of each component per orbit (Figures 2 and 3).

As it was not possible to reliably distinguish between haematoma and muscle on CT scan by threshold alone, the haematoma and muscle volumes were combined as a single segment for the automated volumetric analysis. Assuming no haematoma of the contralateral non-injured orbit and equal extraocular muscle volumes between orbits, orbital haematoma volume was calculated by subtracting the muscle volume of the non-injured (contralateral) orbit from the combined muscle–haematoma volume of the injured orbit. To ensure the integrity of this automated method, a random sample of haematomas was manually segmented by bioengineer RC, with a Pearson correlation coefficient finding of 0.91, representing good correlation between both methods (Figure 4).

The evolution of orbital fat volume was assessed using two methods:

The injured orbital fat volume was compared over time using serial scans, up to a period of six months post-operative. This method was limited by the possible effect of fat compartment oedema in the acute injury and post-operative phases.

The injured orbital fat volume was compared with contralateral intact orbital fat volume in a post-operative scan, up to six months post-operative.

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 30 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Volume change in various tissue compartments over time was analysed using a twotailed paired t-test. A Pearson correlation test was used to determine

subjects had their initial scan within two weeks (median 2 days) of injury.

Fourteen subjects had two CT scans available for serial volumetric analysis, with a mean duration between scans of 26 days. The remaining eight subjects had more than two CT scans available for serial analysis, with a mean duration between scans of 170 days. Nineteen subjects had isolated orbital fractures, whereas three were associated with non- or minimally displaced non-operative ZMC fractures. Of the pure orbital fractures, 12 involved multiple orbital walls (floor and medial wall) whereas seven were isolated orbital floor fractures. Twenty of the orbital haematomas were intraconal, whereas two subjects had both intraconal and extraconal haematomas. A summary of subject demographics and injuries is reported in Table 1

Following reconstruction, the mean difference between intact orbit and injured orbit volumes was 0.02 mL, suggesting a satisfactory reconstruction of bony vault anatomy. Mean orbital haematoma volume was 6.93 mL. As anticipated, there was a marked regression of haematoma volume within the first month.

whether a linear relationship between haematoma and fat volume change existed.

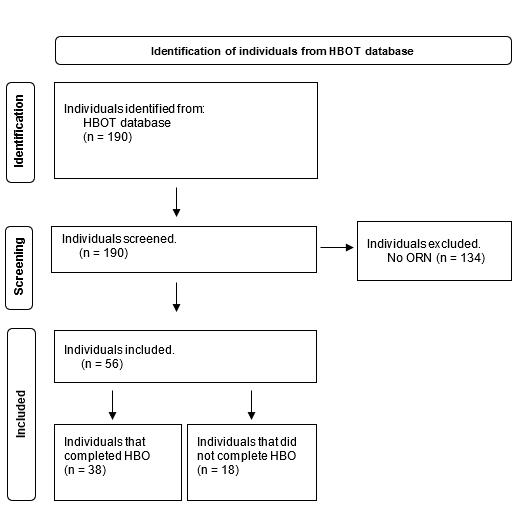

Over the study period (from 2013 to 2023), 488 subjects were identified as having had an orbital reconstruction. Of these, 25 (5.1%) subjects were found to have orbital haematoma and at least one diagnostic and post-operative scan allowing for serial orbital volumetric analysis. Two subjects had such poor quality CT scans (including thick slices > 2 mm, significant motion artifact and scatter) that accurate soft tissue segmentation was not possible and these subjects were excluded. Additionally, one subject had an associated grossly displaced zygomaticomaxillary complex (ZMC) fracture that had been previously operated with a post-operative deformity and thus was also excluded. Of the 22 remaining subjects, there were 47 CT scans available for volumetric analysis. Males accounted for 18 of the 22 subjects and the average age was 38 years. The majority of orbital fractures were caused by assaults, followed by falls and workplace injuries. At least 8 subjects underwent emergency canthotomy with cantholysis in the emergency department for signs of orbital compartment syndrome.

Eighteen of the 22 subjects had their initial CT scan on the day of injury, while the remaining four

Table 1. Subject demographics, mechanism of injury, fracture pattern and haematoma location

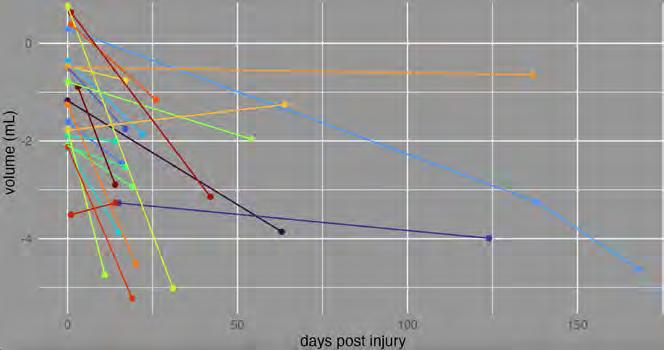

Orbital fat volume of the non-injured contralateral orbit did not change in a statistically significant manner across serial CT scans (P = 0.85), with a mean volume difference of only 0.04 mL (95% CI, -0.47 to 0.39 mL). Conversely, a statistically significant mean orbital fat volume reduction of 1.84 mL in the injured orbit was observed (95% CI, 1.01–2.67 mL, P < 0.001).

Twenty of the 22 injured and reconstructed orbits demonstrated a reduction in fat compartment volume on serial scans (Figure 5). An increase in fat volume, as evident in two cases, may be attributable to pronounced iatrogenic inflammation of the orbital soft tissues post-operatively, resulting in transient fat compartment oedema.

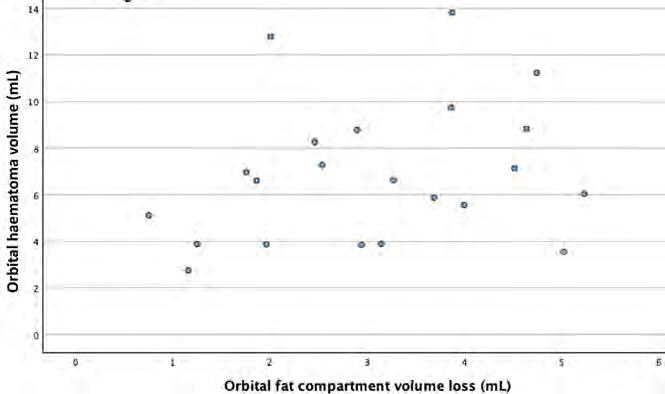

Comparison of the injured and intact orbital fat volumes in the post-operative scan revealed a mean orbital fat volume loss of 3.07 mL (95% CI, 2.48–3.66 mL, P < 0.001). Importantly, this statistically significant change was consistently demonstrated to be a relative deficit in fat volume in the reconstructed orbit, as demonstrated in Figure 6

The Pearson correlation coefficient between haematoma volume and change in orbital fat volume was 0.26 (P = 0.24), indicating no statistically significant correlation between haematoma and fat volume loss (Figure 7).

It is quite possible that what has been observed amounts to intraconal orbital fat necrosis and fibrosis in the setting of orbital haematoma. It remains unclear from this study if the orbital fat volume depletion was due to fat atrophy, necrosis, fibrosis or inadvertent fat removal during surgery.