OFFICINA* Annex

ISSN 2421-1923

N.07 June 2025

OFFICINA* Annex

ISSN 2421-1923

N.07 June 2025

edited by Maria Antonia Barucco

Organised by:

DIPARTIMENTO DI CULTURE DEL PROGETTO

With:

Under the patronage of:

Archivio delle Tecniche e dei material per l’architettura e il disegno industriale

scientific coordinators

Maria Antonia Barucco, Rosaria Revellini in collaboration with Anna Lorens, Laura Patachi with the support of Adriana Casalin, Igor Crotti, Enrico Marconato, Giada Ros and the coordination of International Office, Università Iuav di Venezia

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor EACEA can be held responsible for them.

OFFICINA* Toolbox

editor-in-chief Emilio Antoniol graphic design Margherita Ferrari

Proprietario

Associazione Culturale OFFICINA* via Asolo 12, Conegliano, Treviso

e-mail officina.rivista@gmail.com

publisher Anteferma Edizioni

Printing Press Up, Roma Tiratura 200 copie

Copyright Creative Commons License AttributionNon commercial - Share Alike 4.0 International

The publisher relieves itself of any responsibility regarding violations by the authors of intellectual property rights relating to published texts and images.

Glass is a material that spans centuries and cultures, but it is also language and knowledge. Its evolution is based on the ability to observe, transmit and transform knowledge. This applies as much to the gestures of master glassmakers as to experimentation, new production and design processes, even industrial ones.

No breakthrough, no true innovation, can take place without knowledge sharing. Designing with glass (in the design, craft, architectural, industrial or artistic fields) means first and foremost learning from those who have gone before us, but it also means valuing those who bring new ideas and outlooks, and engaging in dialogue with those who are involved in research.

OVER-TIME GLASS, is the first Venetian Erasmus+ BIP project entirely dedicated to glass. OVER-TIME GLASS is a challenge: we are in Venice to make innovation, to create a confrontation between students, teachers, researchers, craftsmen and professionals. OVER-TIME GLASS is a bridge between the history of glass and the future of glass design, it is interdisciplinary and is dedicated to the designers and glassmakers of the future.

This publication is, in fact, a collection. It brings together the lectures held during OVER-TIME GLASS by passionate and knowledgeable international faculty, is illustrated with photographs taken during the intensive week in Venice, and features selected pages from the students’ notebooks – project journals where sketches, notes, ideas, and visions converge. A living document of the exchange between generations, cultures, and practices, all united by the material of glass.

Maria Antonia Barucco

Over-Time Glass

Introduction by Maria Antonia Barucco

Blurred transparencies by Aki Ishida

Glassblowing and Glassworking by Edward Schmit

History, colours and innovations by Emilio Francesco Orsega

The Murano Glass Museum by Rosa Chiesa

Travelogue I

Through physics and chemistry by Stefano Centenaro

The humble side of glass by Laura Patachi

Toward “new” glazing shells by Rosaria Revellini

Details make perfection by Anna Lorens

Travelogue II

Like the Lion by Maria Antonia Barucco

Travelogue III

AREA DIDATTICA

E SERVIZI AGLI STUDENTI

FONDAZIONE

UNIVERSITARIA IUAV

CLUSTER

GLASS

VALORIZZAZIONE DELLA

CULTURA DEL VETRO: PROGETTI, STORIA, INNOVAZIONI, PROCESSI E STRUMENTI

Glass is a material with extraordinary characteristics: used for thousands of years, it is open to future innovations. OVER-TIME GLASS is dedicated to discovering the glass cultures that characterise the unique territory of Venice professors, lecturers and staff: Maria Antonia Barucco , Elti Cattaruzza , Adriana Casalin , Stefano Centenaro , Rosa Chiesa , Igor Crotti , Aki Ishida, Anna Lorens , Enrico Marconato , Emilio Francesco Orsega , Laura Patachi , Rosaria Revellini , Maximiliano Romero , Giada Ros , Edward Schmid , Matteo Silverio glass@iuav.it IG: @iuav_glass

Maria Antonia Barucco, Università Iuav di Venezia

Erasmus is one of the European Union’s most successful and visionary programs. It enables students to carry out part of their academic journey abroad, with both organizational and financial support. The Erasmus+ Blended Intensive Programmes (BIP) represent a significant innovation: by combining physical mobility and virtual learning. BIP allows more students to access flexible, inclusive, and interdisciplinary international experiences.

OVER-TIME GLASS, like all Erasmus+ BIPs, is a short and intensive program that applies innovative methods of learning and teaching. OVER-TIME GLASS purposes a collaboration between professors and glassmakers from different countries: the invited speakers, lecturers and glassmakers showed remarkable generosity and enthusiasm, matched by the motivation of the students involved.

From an organizational point of view, Iuav has registered a high level of interest in both the programme and its central theme: the number of applicants was three times higher than the number of available places. This is a clear indication of how much interest students have in Erasmus opportunities and, more specifically, in studying, designing, and working with glass.

Venice is a campus city: its international outlook is ori-

ented toward the future, while its foundations are as solid as the centuries-old tradition of Venetian glass.

OVER-TIME GLASS also posed a challenge: a transnational and transdisciplinary team worked together to explore the future of glass and the future of Venice.

The project had a tangible impact: not only on the students of design-related disciplines, but also on the city itself, and in particular on the island of Murano, which was invited to engage in a new and thoughtprovoking dialogue with the designers and glassmakers of tomorrow.

As the lead institution, the Università Iuav di Venezia brought together its educational and research efforts to create a shared platform for international exchange on the material, cultural, and technological values of glass. Iuav is one of Italy’s oldest and most respected schools of architecture and design, with deep ties to Venice and the Veneto region.

Its GLASS cluster, composed of professors, researchers, students, and industry partners, promotes sustainable and innovative approaches to glass in architecture and design. Iuav also hosts specialized archives, a rich materials library, and Europe’s largest architectural library, making it an ideal context for the development of such a program.

Partnering with Iuav was the Faculty of Architecture at Warsaw University of Technology (WAPW), a renowned academic institution in Poland’s capital that combines excellence in teaching with strong links to the professional world. WAPW emphasizes critical thinking, architectural theory, and experimentation. Anna Lorens, coordinator of the first-year English division, also brings her expertise in the relationship between heritage, material culture, and contemporary glass design. At WAPW, glass is not simply a building material, but a conceptual one, offering students a medium through which to explore ideas of transparency, fragility, and transformation.

The third partner, the Faculty of Architecture and Urban Planning at the Technical University of ClujNapoca, is located in the multicultural heart of Transylvania and offers a six-year integrated program in architecture, as well as a doctoral school. While glass is not a formal research focus, the faculty encourages interdisciplinary exchange and active participation in international projects. Laura Patachi, who coordinates Erasmus+ exchanges, led the school’s involvement in OVER-TIME GLASS, building on previous experiences of cross-cultural collaboration. The project was also an occasion to reconnect with the historic links be-

tween Transylvania and Venice, once united by the craft of glassmaking.

Together, the three institutions made OVER-TIME GLASS not just a short-term educational initiative, but a real community of learning. Projects like this highlight the power of shared knowledge in shaping the future. Just like glass itself (transparent yet solid, ancient yet constantly reinvented) this program fosters connections that go beyond disciplinary or national borders. Innovation in glass is only possible through collaboration, and collaboration begins with listening, exchanging, and building together.

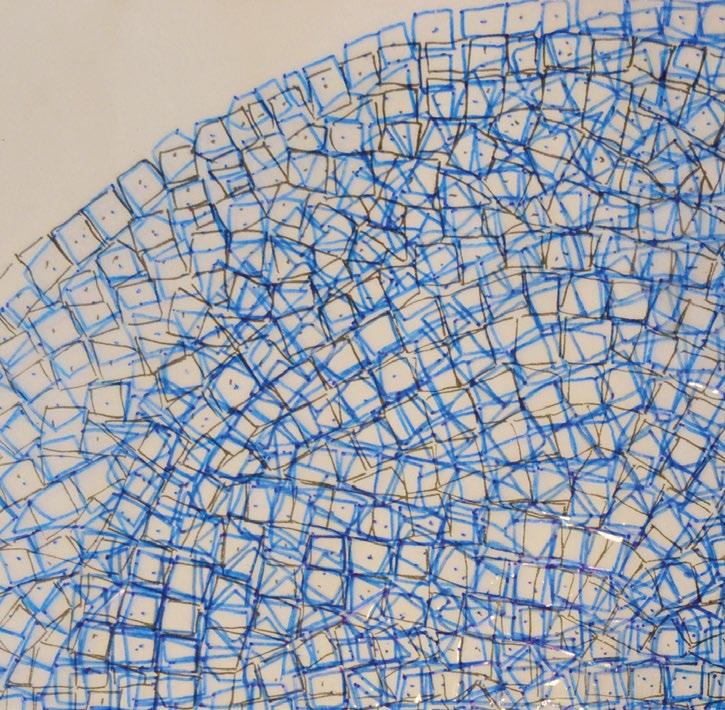

One symbol of this spirit is the image chosen for the OVER-TIME GLASS poster: a photograph of a particular type of Venetian glass known as avventurina. This material, developed centuries ago, contains tiny metallic particles suspended within the glass, creating a shimmering, starry effect. Complex to produce and still lacking a fully codified scientific method, avventurina is made following ancient practices and recipes—an “adventure” in itself, as its name suggests. It is the perfect metaphor for the journey we undertook with this Erasmus+ BIP: rooted in tradition, open to the unknown, and animated by curiosity, experimentation, and the desire to explore the material’s full potential.

AKI ISHIDA

Architect, Author, and Director of Graduate Architecture, Sam Fox School, Washington University in St. Louis.

Glass is often seen as a neutral, transparent medium – a passive boundary between inside and outside. Yet in contemporary architecture, glass is anything but neutral. It is material and metaphor, solid and light, structure and illusion. In my research and practice, I explore these complexities – how the physical properties of glass shape our spatial experiences, and how its symbolic meanings shift across time and cultures.

In my lecture, I introduced key themes from my book Blurred Transparencies in Contemporary Glass Architecture: Material, Culture, and Technology, which examines how glass transcends the binary of visible/invisible. The book analyzes six architectural case studies to show how transparency is never just optical – it is cultural, political, and deeply embedded in technological contexts. Historically, glass was a rare and precious material. Its production was protected by the Venetians for centuries. The lore of glass is rich with symbolism: the glass slipper in Cinderella, the magic mirror in Snow White, or Alice’s journey Through the Looking-Glass – each reflecting social values, desires, and fears. In modernity, glass came

to represent both progress and fragility. The Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, the Crystal Palace, and modern sanatoria all used glass to express ideals of hygiene, control, and enlightenment.

The Zonnestraal Sanatorium in the Netherlands (1928) offers an early and emblematic example in early modernist architecture. Designed with thin concrete and expansive glass, it offered tuberculosis patients access to light and air in the forest. Its transparent curtain walls were not merely aesthetic –they embodied a belief in healing through exposure and openness. But the building was also designed to be impermanent, reflecting the transitory nature of its purpose. Glass here was both a membrane and a metaphor: lightweight, luminous, and ephemeral.

The Javits Center in New York (1986) introduces a political and symbolic dimension to the materiality of glass. Often associated with the term “glass ceiling”, this vast convention center became a focal point of public imagination during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Hillary Clinton’s campaign chose the building as the setting where she was expected to “shatter” that ceiling – an invisible

barrier to professional advancement for women and minorities first described in 1978. Her electoral loss left the metaphor poignantly intact: the ceiling remained, visibly transparent yet structurally impenetrable.

This symbolic use of glass speaks to the paradox of transparency in architecture – and society. A glass surface may suggest openness while quietly enforcing exclusion. At the Javits Center, this paradox is reinforced through light itself: by day, the glass reflects the sky; by night, it mirrors the illuminated interior. The boundary shifts depending on the viewer’s position, echoing the shifting dynamics of visibility, access, and power in public space.

This paradox becomes even more vivid when we consider light. At night, the Javits Center’s interior lighting causes the glass to reflect inwards; during the day, it mirrors the sky. Its appearance is not fixed but dependent on context – just like access and visibility in public space. My third case was the Toledo Museum of Art Glass Pavilion by SANAA. Built in 2006, it is a masterclass in material innovation. Using lowiron laminated glass curved into continuous walls, the pavilion ap-

pears ethereal – like air held in suspension. Mechanical systems are hidden in the roof or integrated into transparent cavities along the perimeter. Even the ducts are made of glass. This building redefines transparency as spatial porosity: rooms are layered like bubbles within a larger glass envelope, allowing light, views, and air to flow seamlessly. What unites these projects is not just their use of glass, but their critical engagement with what glass means. Transparency is never fixed. It is shaped by optics, perception, context – and power. Glass can democratize, but also exclude.

Glass is anything but neutral: it is material and metaphor, solid and light, structure and illusion

up in landfills, despite its long decomposition time. We must consider the environmental and social costs of using glass purely for symbolic effect. Can we design with glass more responsibly – both materially and culturally?

A building may appear open, while its economic barriers remain intact. Projects like Columbia University’s Manhattanville campus use glass façades to signal public openness, yet price points often make the interiors inaccessible.

The environmental dimension of glass also demands critical attention Though often praised as recyclable, architectural glass is rarely reused. Contaminants, coatings, and embedded frames make recycling complex. Most flat glass ends

Glass fascinates because it transforms: from sand to sheet, from vision to metaphor. Its evolution in architecture reflects our evolving ideals. But its future depends on how we reconcile performance with meaning, desire with responsibility. As students and future architects, your task is not just to use glass –but to question it.

In the previous page, Mosaics of St. Mark’s Basilica made of colored glass tesserae and gold leaf. E. Marconato

Above, Students preparing travel notebooks during their stay in Venice. E.

Below, Leaded stained glass window made by Nicola

EDWARD T. SCHMIDT

Artist, Educator, and Author of Glassblowing Books.

I was born in 1964 in Chicago – the very year the Studio Glass Movement began. We’ve both come a long way since. My first encounter with glassblowing happened in 1972 at the Jamestown Glasshouse, a colonial site in Virginia. Watching molten blobs of glass transform into elegant forms felt like witnessing magic. I was eight, and I was hooked.

I didn’t touch molten glass myself until 1984 at the University of Illinois. I had to fulfil a humanities credit and saw a course called “Introduction to Molten Glassworking.” One gather from the furnace, and I was fully immersed – heart, hands, and heat. That same year I studied abroad in Austria, and the cultural shift opened new ways of seeing and thinking – experiences that still inform my work.

I went on to earn degrees in German (1987) and Fine Arts (1988), and that’s when I encountered the Pilchuck Glass School in Washington State. It was a hotbed – literally – of creativity, with glass enthusiasts from all over the world. There, I first met the Venetian Masters: Lino Tagliapietra, the Rosin brothers, Pino Signoretto. Their speed, skill, and team-based approach blew open the doors of possibility.

Watching them was like watching alchemists at work. These encounters forged a bridge between Murano and American studios, transforming closed-door tradition into collaborative dialogue. It was controversial in Murano, but the masters believed it was better to share than to take secrets to the grave. I couldn’t agree more.

After completing my MFA at The Ohio State University in 1990, I started teaching – and quickly realized my students needed better resources. At the time, there were no instructional books on glassblowing. So, I wrote one. Ed’s Big Handbook of Glassblowing (1993) was followed by Advanced Glassworking Techniques (1997) and an updated beginner’s guide in 1998. All are handwritten, hand-illustrated, and self-published. These books have reached glass artists, schools, and universities around the globe, and have been translated into Chinese and French. They’ve opened doors for me and helped others unlock the mysteries of glass.

Currently, I’m working on a trilogy of books dedicated to Venetian glass: an introduction to Murano’s rich tradition , a volume on goblet-making, and another on

cane and murrine techniques. I’ve spent time in Murano, working with families who’ve shaped glass history for centuries. Many of the old masters are now gone, and younger generations often choose different paths. It’s bittersweet: so much knowledge is vanishing, but that’s all the more reason to document and share what remains.

My own work has taken many forms over four decades. I make Helixes , DNA-inspired glass sculptures; large-scale poppy installations for gardens and public art; and a series of sculpted glass hands, born from the moment my daughter Ailia came into the world. Those small, dimpled baby hands became gifts to the doctors – and then, an entire body of work. Hands are tools, but also vessels of meaning. One piece, Silence is Golden, features the full American Sign Language alphabet in glass. Not everything I make is solemn. I once created The Offensive Players Chess Set , where pawns flip each other off – yes, an obscene gesture – to poke fun at the game’s seriousness. Humor has its place in the hot shop too.

In 2022, I was invited by the GlazenHuis Museum in Lommel, Belgium, to create an exhibition

called The Holy Grail , inspired by my instructional books. I illustrated glassmaking techniques directly on windows and tables in their stunning steel-and-glass space. Visitors could follow the steps behind each piece, and I demonstrated in the hot shop, making connections that now extend across Europe.

I believe the “Golden Age of Glass” is now. Never before has there been such global diversity in styles, communities, and cross-cultural learning. The internet, residencies, and education have transformed access to knowledge that once passed only through apprenticeships. Artists collaborate across borders. Techniques once guarded are now shared. But this moment is fragile. Rising fuel costs and climate concerns make hot glasswork a luxury – and a responsibility. If we want this movement to endure, we must innovate together: develop cleaner practices, share infrastructure, reimagine how and why we work with glass. The moment is bril-

liant, but also fleeting. What we do now determines if this golden age becomes a lasting legacy – or a lost opportunity.

Some Murano factories closed during the recent gas crisis, but others survived through collaboration and adaptation. I believe partnerships between artists, de -

I believe the “Golden Age of Glass” is now. Never before has there been such global diversity in styles, communities, and crosscultural learning

signers, and Venetian Masters can spark new vitality. Educational projects like OVER-TIME GLASS aren’t just cultural – they’re structural: they shape the future by connecting past and present, tradition and invention.

Sharing knowledge, building community, keeping the flame alive –that’s how we make glass matter.

EMILIO FRANCESCO ORSEGA

Professor of Chemistry, Ca’ Foscari University of Venice.

Talking to a group of young, curious minds about glass is not only a pleasure – it’s a privilege. Because glass, as ancient as it is, is still a wonder to explore. It’s science, it’s art, it’s culture. It’s a material born from sand, heat, and light. And it has been part of human history for over 5,000 years.

The story begins – maybe – in Mesopotamia, or Egypt, or Phoenicia. We don’t know exactly where the first bead was made, but we do know how: by melting sand mixed with a flux, then letting it cool into a new, magical state – glass. Unlike crystalline solids, glass has no long-range order; it’s an “amorphous” solid. That may sound like chemistry, but what it really means is that glass is neither fully liquid nor fully solid. It’s unique.

The discovery of fluxes – like natron or plant ashes – was a turning point. These substances lowered the melting point of silica, allowing ancient people to work with fire more efficiently. And this brings us to one of my favourite stories. According to Pliny the Elder, Roman author of Naturalis Historia, glass was discovered by accident when Phoenician merchants cooking on a beach used blocks of natron to support their

pots. The fire, sand, and soda reacted, and a transparent stream of glass flowed out. A legend? Surely. But a powerful one – because it captures the simple genius behind this material: sand, soda, and fire. Once glass could be shaped, another revolution followed: color. Ancient artisans added minerals and metal oxides to give glass its hues. Cobalt made it deep blue, manganese gave violet tones, iron offered yellows and greens, copper brought aquamarine or even deep reds. They may not have known about atoms or wavelengths, but they understood light, and they mastered it. Some of their most beautiful results – like red glass made with gold nanoparticles –were examples of empirical nanotechnology long before the word even existed.

From the sands of Egypt to the furnaces of Murano, glass evolved hand in hand with civilization. It was blown into shape in the Roman Empire, turned into mosaics in the Byzantine world, painted in cathedrals from Paris to Barcelona. In Venice, it reached perfection. Venetian “cristallo” became the clearest, purest glass in the world. Techniques like lattimo, millefiori , and filigrana created

objects of stunning beauty and precision. Venice didn’t just make glass – it ruled its secrets, shaping commerce and aesthetics across centuries.

But what truly amazes me is how glass connects everything: science and art, past and future, matter and light. It’s humble – made of sand –and yet capable of infinite transformation. It’s everywhere around us: in windows, in screens, in labs, in artworks. And every piece of glass carries within it a fragment of human ingenuity and curiosity.

As a chemist, I study what glass is made of. As a teacher, I love to explain how it works. But above all, I love to see what happens when students ask questions, experiment, discover. Working with glass is not just about knowing its composition – it’s about feeling its rhythm, understanding its behavior, imagining what it can become. That’s why interdisciplinary projects like OVER-TIME GLASS are so important. They bring together knowledge, creativity, and people – from Venice to the world.

To those of you who are just starting to explore this material: don’t be intimidated. You don’t have to know everything. Glass is a lifelong companion. It teaches pa-

tience, precision, and joy.

You will fail sometimes – it’s part of the process. But then one day, something melts right, flows right, cools into exactly what you imagined. That moment is priceless.

Working with glass is not just about knowing its composition: it’s about feeling its rhythm, understanding its behavior, imagining what it can become

Remember: the glassmakers of the past weren’t just artisans – they were innovators, researchers, inventors. Today, you can be one too. Whether you work in a studio, a lab, or a classroom, the flame is yours to keep alive.

Let’s keep glass glowing – together.

ROSA CHIESA

A visit to the Murano Glass Museum offers a journey through centuries of artistic innovation, technological mastery and cultural transformation, filtered through the story of glassmaking. During the lecture, participants explored key pieces from the museum’s rich collections, focusing on particularly significant objects and the knowledge systems they embody. The museum is located in the Palazzo Giustinian, a historical Gothic residence that underwent a transformation into a civic archive and museum under the direction of Antonio Colleoni and Vincenzo Zanetti in the year 1861. In 1862, Abbot Zanetti established the glass school attached to the museum, with the aim of providing education for glassmakers through the conservation and study of techniques and models from the past.

The tour starts in the archaeological section, where the origins of glass in Mesopotamia, Egypt and Syria are examined. Among the various theories posited on the origin of glass, Pliny the Elder (c. 23–79 AD) relates in his Naturalis Historia that the discovery of glass occurred by accident. The accidental discovery of glass is attributed to Phoenician traders, who, upon heating sand from the river bank in proximity to blocks of natron (a natural soda ash), witnessed

the unexpected reaction of the two substances.

The earliest objects in the collection, which covers a very wide interval between the 1st century BC (where the glassblowing technique is attested) and the 4th century AD, are blown glass cinerary ollae and other grave goods, rings, bracelets, bowls and mould-blown glasses. The balsam jars, which are distinguished by their use of polychrome ribbon technique in both blown and moulded glass, serve as a significant exemplar of ancient forms and techniques that would inform the work of 19th-century Murano glassmakers.

During the medieval period, and the Renaissance that succeeded it, glassmakers in Murano developed extraordinary methods of colour and decoration. An exemplary instance of the technique of fusible enamels applied and fired on crystal surfaces is the Coppa Barovier (c. 1470), a deep blue vessel with vivid enamel portraits. This technique was present in Murano since the 13th century, spreading rapidly and being in great demand outside the island until 1500. During this period, the discovery of crystal, a clear, impurity-free glass that rivalled rock crystal, whose introduction is attributed to Angelo Barovier, revolutionised production. Subsequently,

lattimo, a white glass analogous to porcelain, which emulated Chinese ceramics, gained popularity.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the art of glassmaking in the Italian island of Murano reached an unprecedented level of technical mastery, particularly in the creation of crystal objects known as “flying hand” pieces. The artisans demonstrated a high level of expertise in filigree techniques, employing threads of white or coloured glass that were embedded in transparent crystal. These threads were utilised to create intricate motifs, such as twisted (retortoli) or criss-crossed (reticello) patterns. New surface treatments such as ice glass (created by immersing hot glass in cold water), diamond point etching and aventurine (glass with metallic inclusions that shine like stars) exemplified technical innovation and creative flair.

The museum’s collections of mirrors and chandeliers serve to illustrate Venice’s status as the capital of luxury.

The monumental glass deseri (table decorations) and sumptuous light fittings demonstrate how glass objects were designed with strong symbolic meaning, representing the power, wealth and taste of European courts.

A dedicated section is dedicated to glass beads, a tradition of signifi-

cant commercial importance to Murano. Since the 14th century, beads have functioned as a medium of exchange in global trade with Africa, the Americas and Asia. The production process demanded a high level of precision and creativity, qualities that continue to inform Murano craftsmanship in the present day.

The section dedicated to the 19th-century revival examines how Murano survived a profound production crisis by reinterpreting ancient forms.

in 1921 and gained renown for its collaborations in the furnace with artists and designers. The oeuvre of Vittorio Zecchin, Carlo Scarpa and Tapio Wirkkala exemplifies a range of forms, from the essential to the expressive, and features the adoption and adaptation of ancient techniques. The pulegoso glass, invented by Na-

The Murano Glass Museum should be regarded not merely as a place to admire objects, but as an institution through which to comprehend glass as a cultural system

The rediscovery and perfection of Murano glass is attributed to figures such as Vincenzo Moretti, who attained mastery in both technique and the formal imitation of the originals, leading to the creation of decorative vases and plates that reconnected Murano to its Roman and Byzantine heritage.

The tour concludes in the 20th and 21st centuries, featuring designers, artists and innovative companies, from the historic Barovier & Toso and Venini to SAIAR Ferro Toso and Carlo Moretti. An exemplary case study is Venini, which was founded

poleone Martinuzzi in the 1920s and exhibited at the 16th Venice Biennale, is characterised by the thousands of air bubbles imprisoned in the thick, sculptural glass, which transformed a “physical imperfection” into an artistic signature. The submerged, developed by Flavio Poli, involves the layering of colours in a manner that results in their submersion within a state of transparency.

Contemporary artists such as Laura Diaz de Santillana, Yoichi Ohira, Toni Zuccheri and Lino Tagliapietra have pursued the path of innovation, helping to shape the identity of

Murano glass by also opening it up to international perspectives.

In conclusion, the Murano Glass Museum should be regarded not merely as a place to admire objects, but as an institution through which to comprehend glass as a cultural system. The book reveals how materials, tools and gestures are embedded in the histories of trade, design and innovation. The institution provides a source of inspiration for students of architecture, design and art, whilst also imposing a responsibility upon them to preserve, re-imagine and evolve this extraordinary heritage.

previous page,

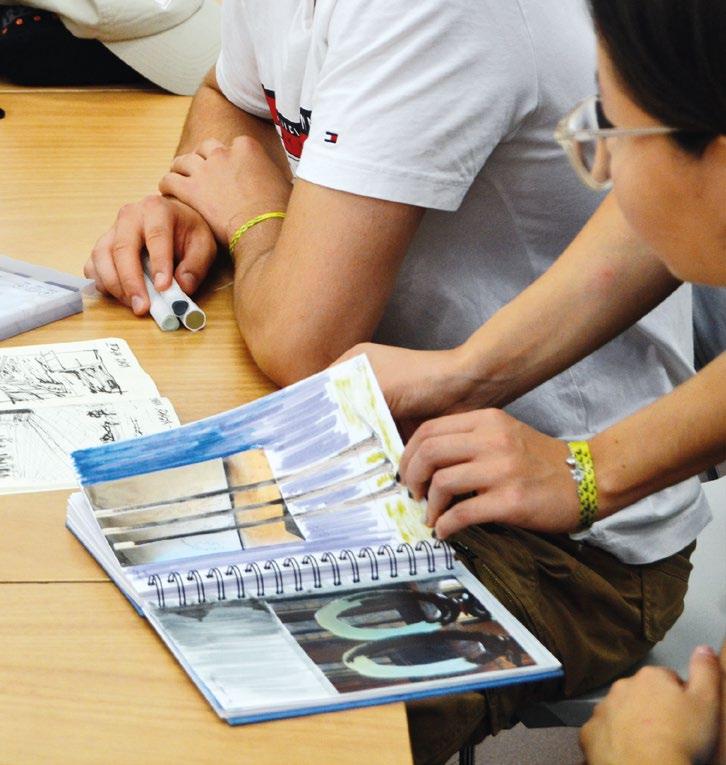

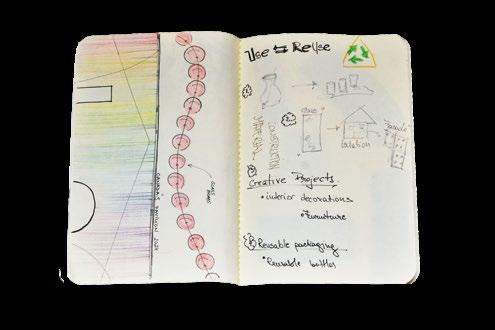

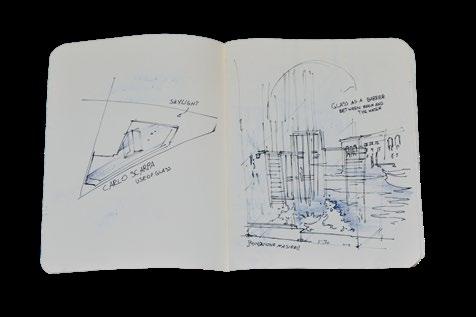

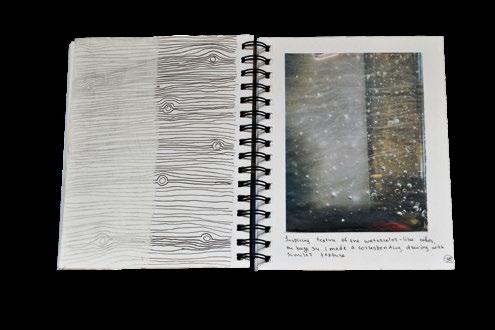

Each student completed the Erasmus+ BIP by producing a personal sketchbook: a visual diary of the grand tour through Venice and Iuav, exploring the many faces of glass. From Murano furnaces to Iuav labs, from design studios to contemporary exhibitions, every place offered new discoveries. These sketchbooks became not only exercises in observation, but design tools, capturing forms, colors, and techniques. “The sketch is immediate thought, not yet fully thought. It reveals much of an architectural practice and a vision of the world” (Gluglielmo Baglioni).

In these pages, tradition meets innovation. Each student carries a personal map of discoveries and future design ideas shaped by Venice.

The students who participated in OVER-TIME GLASS are: Iulia Maria Chiorean, Kinga Dopierala, Roberta Lucia Fit, Maria Iuga, Cecile Marie Lucille Jouault, Anna Klymiuk, Gabriela Magdalena Krawiec, Yaroslav Krivchenkov, Magdalena Laszkiewicz, Antonia Elizabeth Luca, David Cristian Morar, Inkar Okhazzova, Stefania Oltianu, Alessia Pasqualetti, Simone Pella, Weronika Pikulinska, Nicoleta Popa, Antonio Al-

exandru Rindunica, Elisa Scapin, Viola Schiavoni, Ekaterina Smirnova, Camelia Teposu, Emmanuel Edgar Wiech, Julia Maria Wieczorek, Amelia Joanna Zalowska.

Some photos of the students’ sketchbooks during the week in Venice. E.

STEFANO CENTENARO

PhD in Chemistry and Materials for Cultural Heritage, researcher in glass science.

From the Stone Age to the Bronze Age, from meteoritic iron to nanomaterials, the history of materials has always shaped human civilization. Today, we may be living in what scientists and industry experts define as the Glass Age – a period where glass is not only ubiquitous but central to technological innovation and sustainable design. My lecture explores the physical and chemical foundations of glass, its historical evolution, and its contemporary relevance, especially in the context of Murano, a place where tradition and innovation continue to meet.

We begin by addressing a basic yet profound question: What is glass?

From an artistic perspective, Murano glassmakers often describe it using paradoxes – solid and liquid, permanent and ephemeral, decorative and functional. From a scientific standpoint, the most widely accepted definition is that glass is a noncrystalline solid that undergoes a glass transition – a gradual, reversible change from a viscous to a rigid state as temperature decreases. Glass formation usually begins with silica (SiO2), a network-forming oxide capable of creating a continuous amorphous structure. In artistic glass production, particularly

in Murano, purified silica sand is combined with modifiers like sodium carbonate (Na 2CO3) and calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Sodium lowers the viscosity of the melt, making it workable at lower temperatures, while calcium improves chemical durability by stabilizing the disrupted silica network.

But glassmaking is never as simple as mixing a few ingredients. During melting, chemical reactions produce carbon dioxide bubbles. To ensure clarity, refining agents –such as antimony trioxide or metal nitrates – are added to promote the formation of larger bubbles that rise more quickly and capture smaller ones. This process, governed by Archimedes’ principle and buoyancy forces, is crucial to producing bubble-free artifacts, especially in the rapid working times typical of Murano furnaces.

The lecture examined how glass can be synthesized through alternative methods, such as sol-gel processing or chemical vapor deposition, both of which allow for lowtemperature fabrication of glass materials and coatings used in optics, electronics, and architecture. These techniques demonstrate the technological versatility of glass far beyond traditional hot-working.

Another key topic is color – an essential feature of Murano glass. Color in glass arises mainly from selective absorption of light, due to the presence of transition metal ions or nanoparticles. Yet, perception is not only about material composition. It also depends on the type of light, the way light interacts with the object (reflection, transmission, scattering), and the anatomy of the human eye. For example, birds can perceive ultraviolet light, while dogs see fewer colors but process images at higher frame rates than humans.

A fascinating example is the Lycurgus Cup, a Roman glass vessel made in the 4th century CE. When lit from the outside, it appears green; when lit from within, it turns deep red. This dichroic effect is caused by the presence of tiny colloidal particles of gold and silver dispersed in the glass. These nanoparticles interact with light in complex ways, combining absorption and scattering phenomena that modern physics is still studying. The cup demonstrates how ancient artisans, without knowing modern optics, intuitively created early nanostructured materials. Finally, the issue of glass recycling was addressed – an increasingly

relevant topic in the transition toward sustainable production. In ancient Rome, clear glass was remelted to create new vessels, while colored fragments were used for mosaics. Today, container and flat glass represent the majority of Europe’s production – over 40 million tons annually. Recycling helps reduce energy consumption and raw material use, but challenges remain.

Murano glass, for instance, often contains mixed compositions, non-glassy inclusions, and polychromatic fragments, making it harder to process in standard recycling loops.

– aims to address these challenges by combining scientific analysis, digital mapping, and close collaboration with master artisans.Studying glass in Venice is not just about technique – it’s about immersing yourself in a culture of material knowledge, artistic excellence, and interdisciplinary dialogue.

But glassmaking is never as simple as mixing a few ingredients. During melting, chemical reactions produce carbon dioxide bubbles

Still, the message is clear: glass is a permanent material, and with thoughtful design and responsible strategies, it can be recycled infinitely without losing its properties.

Research projects such as Murano Pixel , to which I contributed before starting my PhD, aim to address these challenges by combining scientific analysis, digital mapping and collaboration with master craftsmen. Murano Pixel is also a publication (Anteferma Edizioni, 2023)

Whether you come from architecture, design, chemistry, or conservation, the world of glass will offer you complexity, beauty, and a sense of wonder that spans centuries. Welcome to the Glass Age.

LAURA PATACHI

Lecturer, Technical University of Cluj-Napoca, Faculty of Architecture and Urban Planning.

In Venice, glass was a guarded secret: a luxury, the privilege of an elite, and the center of a highly controlled craft tradition. In Transylvania, glass took a different path — becoming a popular medium, accessible and humble, yet culturally powerful. Here, painted glass icons offered ordinary people a space for both faith and expression. They allowed religious and personal stories to be told through simple materials, beyond the reach of political and social constraints.

The tradition of reverse glass painting ( pictură pe sticlă) emerged as a form of resilience. Even under oppressive regimes where freedom of expression was limited, these sacred images offered a margin of autonomy — a spiritual and artistic territory protected by devotion. The vision and dedication of enlightened religious leaders and patrons, like Father Zosim Oancea in Sibiel, helped preserve and develop this tradition into a form of popular heritage that survives and thrives today. In the dialogue of OVER-TIME GLASS, this encounter between the elite craftsmanship of Murano and the folk art of Transylvania offers a precious lesson: glass, regardless of its context, remains a medium of light, fragility, and narrative.

Whether in the shimmering chandeliers of Murano or the intimate icons of Sibiel, glass carries voices across time, borders, and cultures. Located in southern Transylvania, the village of Sibiel hosts Romania’s most important collection of painted glass icons. The Museum Priest Zosim Oancea , founded in 1969, preserves around 600 examples of this folk art, thanks to the vision of Father Zosim Oancea. A former political prisoner and parish priest, Oancea led the restoration of the local church and encouraged villagers to donate traditional items, including many icons painted on glass. These icons are a unique expression of Romanian spirituality and artistic resilience. Born in the 18th century, this practice spread in rural areas through self-taught artists who used simple tools and natural pigments. The reverse painting technique, influenced by Central European glassmaking and Orthodox iconography, transformed fragile glass sheets into luminous images of saints, the Virgin Mary, or the Holy Trinity. Initially popularized after the miraculous weeping of a wooden icon in Nicula, glass icons soon became widespread in homes and farms, offering everyday protection and comfort.

Painting on glass was a family activity, a fusion of craft and devotion. Thin and imperfect glass gave these icons their distinctive light and texture. Over time, the compositions became more personal, adding symbols from peasant life and folk beliefs. While initially spiritual objects, these works later gained recognition as expressions of popular culture and artistic authenticity. What is really interesting is that the artists introduced original compositions enriched with folkloric motifs, personal observations, and realistic elements drawn from everyday rural life. As a result, the glass icon evolved into a medium not only of religious expression but also of social commentary, reflecting the collective values, concerns, and aspirations of the peasant communities that produced and venerated them.

In the face of industrialization and communist repression, Father Oancea’s museum helped preserve this tradition. These icons were collected, studied, and displayed in museums both within Romania and internationally. Today, Transylvanian painted glass icons are regarded as one of the most significant contributions of Romanian culture to global artistic heritage, valued for

their aesthetic qualities as well as their ethnographic and historical importance. The tradition of glass icon painting continues to be practiced in specialized centers across Romania, with new experts in the restoration of these works trained annually.

Still today, pictură pe sticlă stands as a symbol of cultural resistance, proof that glass – humble yet radiant – can carry stories of faith, identity, and collective memory. What connects these two geographies (Venice and Transylvania) is not style or hierarchy, but the shared ability of glass to narrate, preserve, and transcend. In Venice, it reflected cosmopolitan splendor; in Transylvania, it gave form to a spiritual vernacular.

rooted in territory, yet open to the world.

For students and designers, this is not a comparison of opposites, but an invitation to understand glass beyond its surface: to recognize its potential as both art and testimony.

Thin and imperfect glass gave these icons their distinctive light and texture. Over time, the compositions became more personal, adding symbols from peasant life and folk beliefs

The OVER-TIME GLASS project embraces this diversity of voices. It highlights how different traditions (elite and popular, crafted in secrecy or shared in devotion) can converge in the same luminous material. Murano’s chandeliers and Sibiel’s icons both tell stories

ROSARIA REVELLINI

Architect, PhD in Technological architecture and research fellow at Università Iuav di Venezia.

Transparent building envelopes define an interior and an exterior without establishing a sharp boundary, marking a physical threshold that is not always perceptually evident. In the architecture field, the challenge primarily lies in achieving high energy performance while also ensuring the privacy of those occupying interior spaces.

In contemporary architecture, both at small and large scales, there is growing experimentation with “new” glazed envelopes that use advanced techniques and technologies. These solutions improve a building’s energy efficiency while also providing adjustable opacity to ensure privacy when needed. A notable example is the public toilets designed in Tokyo by architect Shigeru Ban. The concept of a transparent enclosure for a space dedicated to privacy, especially in urban public areas, may appear paradoxical. However, it is made feasible through specific technologies that render the glass opaque when the door is locked. These small enclosures employ switchable glass that transitions between transparency and opacity (on/off) using Polymer Dispersed Liquid Crystal (PDLC) technology,

thanks to a film placed between two glass panes that activates or deactivates via electrical current. In the broader domain of smart or dynamic glass, the reflective properties of the material change when subjected to external stimuli such as electricity, heat, or light. Smart glass can be categorised into active and passive types: the former responds to electrical stimuli and can be controlled either manually or automatically; the latter reacts only to non-electrical stimuli and cannot be manually adjusted. Further research and experimentation should also focus on photovoltaic (PV) glass and solar control films application (SCF) to windows and glazed façades. PV glass combines traditional glazing with integrated solar cells, enabling electricity generation from sunlight while optimising the envelope’s performance, especially where structure modifications, such as the roof, are not feasible. These cells, typically made from thin-film photovoltaic materials like amorphous silicon or cadmium telluride, maintain a degree of transparency.

The combination of PV and smart (electrochromic) glass is known as photovoltaic-chromic glazing. This

technology is designed to adapt to daily weather variations, enhancing solar heat gain control and daylight management within buildings.

Regarding solar films, UNI EN 15752-1:2015 identifies a wide range of options based on function: lowemissivity, UV-reduction, privacy, safety, and solar control. These are thin, adhesive layers applied to interior or exterior glazing surfaces, offering a passive solution to regulate sunlight, heat, and UV radiation—thereby reducing glare, solar heat gain, and cooling energy demand. However, SCF performance is influenced by several variables, including glass type and size, local climate, film placement, solar orientation, shading systems, the efficiency of HVAC systems, and building maintenance. For instance, SCFs perform better in hot climates and when applied to large glazed areas. Exterior films are more effective than interior ones, as the latter may re-radiate absorbed heat into indoor spaces. Despite their benefits, drawbacks include increased demand for artificial lighting and heating, particularly in colder climates due to reduced daylight transmission and solar gain.

One of the main limitations re-

mains costs, which exceed traditional glazing ones, though often justified by projected energy savings. Aesthetic concerns, particularly regarding PV glass, are another factor: dark solar cells embedded in the glass may limit its use in historic building retrofits, where appearance is critical. Moreover, PV glass can increase heating and lighting loads needed to maintain indoor comfort.

Continued experimentation in this field could enable transparent surfaces to be used even in particular contexts (such as historic sites) where energy efficiency and privacy could demand glassbased solutions.

In addition, the way in which a glazed envelope is designed and constructed can also contribute to these effects. For example, the use of curved and undulating glass façades – as seen in the Casa da Música in Porto by OMA – creates a deep transitional buffer space that mediates between inside and outside. This spatial filter not only

ensures continuity with the reinforced concrete envelope but also allows natural light to enter in a softened, non-intrusive manner. Ultimately, these innovations return a sense of “magic” to glass, a material whose history has always been imbued with wonder.

There is growing experimentation with ‘new’ glazed envelopes that use advanced techniques and technologies [..] to improve buildings’ energy efficiency and ensure privacy when needed

previous

ANNA LORENS

Architect, Product Designer (incl. Sirulighting_Venezia), Assistant Professor at Warsaw University of Technology, Faculty of Architecture.

Glass is the most ephemeral and durable material, as fragile as resilient and invisible. No other material has as many properties as glass— transparency, reflectivity, translucency, gradient, color, refraction, and cooperation with light, provoking optical illusions. Glass is present in architecture and everyday objects as a symbolic, almost invisible frame. The transition between landscape and opaque building walls has been sought for centuries to blur the inside and outside. Thanks to its haptic qualities, the medium of technology is sometimes the most valuable because it presents much while remaining invisible.

From the perspective of an architect and product designer, analyzing and understanding the potential that is obtained in a material is crucial. It allows us to see the possibility of moving between scales – both from architecture and the object, but also the location of the object in the landscape – at the level of perception, application, and emotions it can arouse.

“My working method has more often than not involved the subtraction of weight. I have tried to remove weight, sometimes from people, sometimes from heavenly bodies, sometimes from cities;

above all I have tried to remove weight from the structure of stories and from language… I have come to consider lightness a value rather than a defect.” (Italo Calvino, Six Memos for the Next Millennium , 1988)

This is what Italo Calvino wrote about language as the primary way man communicates with the world. Referring to the lightness of glass as a material, in a phenomenological sense, it can be seen as the only material that, thanks to the play of light, in design imperfections resulting from craftsmanship is a ‘living language, in motion, requiring constant updating and discovery, like the world, like the landscape, like the environment. For design work on glass to have a holistic dimension, confronting it with research into the material, searching for revaluation methods, and, conversely, showing students what results can be achieved in practice is, in a sense, inseparable. At the same time, students can conclude why this research is being done. This approach was the starting point for organizing the OVERTIME GLASS Erasmus+ BIP. Students had great opportunity to visit with us: artistic glass factories on the island of Murano, sev-

eral delightful places, including the little-known and inaccessible to tourists secret Palazzina Masieri designed by Carlo Scarpa, Negozio Olivetti, and even an old workshop entrusted with the reconstruction of the mosaic in the Basilica of San Marco. In international teams they made designs of objects and architectural elements in glass, along with documentation of sketches, photos, and visualizations. This was all thanks to the invaluable supervision and hard work of the team of organisers and collaborators, starting from the offices to all the lecturers and industry experts who were involved.

The designs were made as part of the Erasmus+ BIP initiative under the supervision of Prof. Maria Antonia Barucco (Università Iuav di Venezia), me (Anna Lorens - Faculty of Architecture, Warsaw University of Technology), Prof. Laura Patacchi (Faculty of Architecture and Urban Planning, Cluj-Napoca). Then, to follow the initiative and the recently established Student Scientific Circle under my supervision – we showed the results of our work at the Light Fair in Warsaw. It was a unique opportunity to show projects and research to various audiences and show students how to confront work in the global

environment.

Some refere to time, its passage, transience, and freezing.

Considering the thread of the impact of human life on Earth and how this presence can be marked “life after life”.

From the perspective of a designer, analyzing and understanding the potential that is obtained in a material is crucial. It allows us to see the possibility of moving between scales [..] at the level of perception, application, and emotions it can arouse

From the perspective of a designer who remains fascinated by the relationship of glass to the landscape, in the composition of recycled glass (algae and sand), in visual representation – reflectivity, transparency, the dimension of emptiness framed in an object, and above all, the transmittance of light in various intensity and color, as honestly and truly as almost air, fog or rain, I believe that the ability to combine craft, technology, material sensitivity with environmental conditions is key; in the form of minor architecture, building systems, or the object itself, with the passage of time and what we can record in that time is the path that best marks the impact of design on earth and of which the above projects are a perfect representation.

When designing the first collection of lamps for the Venetian brand Siru, – Muzzle, I tried to convey in the name and form of glass blowing through the cage – the etymology of the Polish word, where “muzzle” meant a portable lantern – a symbol of carrying light in the understanding – the light of knowledge. Just as a craftsman shares his work with a designer, we - designers and educators share our knowledge and should conduct experiments at universities – this is an inseparable mission. Let the workshop described above remain an example of best practices.

MARIA ANTONIA BARUCCO

Associate professor of Technological architecture at Università Iuav di Venezia.

While this Erasmus+ BIP was taking place, news arrived of an important discovery. It helps us better understand and interpret Venice. In my opinion, it also helps us reflect on the role of those who approach glass with curiosity, whether professionally or, even better, as students. Through the comparison of chemical data describing lead isotopes, and thanks to increasingly extensive and detailed archives, it has been confirmed without doubt that the Lion of Venice, standing on one of the two columns in St. Mark’s Square, is in fact a zhènmùshòu . It is a Chinese lion, made between 609 and 907 AD. Between 1260 and 1270, after the loss of Constantinople, Venice adopted the winged lion as a political and state symbol. Considering Venetian travels, trade, and diplomatic skills, it is plausible that the Venetians were aware of the distant origin of their Lion. During the Tang Dynasty, zhènmùshòu guarded the most important Chinese tombs. They were monstrous creatures resembling lions and dragons. It is unclear when the Lion arrived in Venice. But it was certainly in Venice by 1295, during the period of Nicolò and Maffeo Polo’s travels to China, the father and uncle of the famous Marco Polo. Few zhènmùshòu still exist. Many

were destroyed after the Tang period. Probably, when the Lion began its journey to the Venetian lagoon, it was already a prestigious, rare object full of meaning. Venice could neither ignore nor diminish its significance. Perhaps, by choosing this Eastern lion as their symbol, transforming a zhènmùshòu into a symbol of Saint Mark and the Serenissima itself, the Venetians created what is, in every respect, the most beautiful symbolism of the Lion of Venice.

Venice is like its Lion.

It does not stand still; it moves, it travels. The Lion on the column in St. Mark’s Square seems ready to take flight. The “marching Lion” is depicted by Carpaccio and in many other sculptures, fabrics, and paintings. The Lion’s back paws rest on the lagoon, while the front paws touch the mainland. In this way, it represents Venice’s essence. A place from which to depart towards distant paths. A meeting point between land and water. Venice connects distant places and people.

Venice does this not only through careful governance and economic strategy, but by connecting cultures and knowledge, arts and crafts, techniques and technologies, innovations and traditions. And, from my point of view, also very different

types of glass: the artistic and artisanal glass is related to the more industrial glass and the most advanced technical innovations. This logic of connection and multiplication of perspectives lies at the heart of the Erasmus+ project and its vision for Europe. A continent that grows not by closing knowledge within borders, but by building new knowledge through a network of cultures, schools, disciplines, and generations. Venezia Città Campus is a great project. This Erasmus+ BIP contributes to it, showing how relevant it is to dedicate education and research to glass. Studying glass today does not mean attending a single laboratory, however specialized. It means crossing a network of knowledge. No single furnace can contain all the knowledge required. Instead, there are many artisanal and scientific laboratories in Murano, Venice, and its territory. The strength of the GLASS cluster of Università Iuav di Venezia lies in this plurality of approaches and skills. It is a network that brings together researchers, professors, companies, artisans, designers, architects, and students. An ecosystem of study and design that allows glass to grow, not only as an excellent product but as an international cultural and scientific platform.

The news of the Lion’s origins, and its coincidence in time with OVER-TIME GLASS, reminds us of the role of Erasmus+ BIPs in European Union programs and in the Venezia Città Campus project.

Studying glass today does not mean attending a single laboratory, however specialized. It means crossing a network of knowledge

Venezia Città Campus moves precisely in this direction. It makes Venice a place to stop, to study, to meet, to debate, and to generate innovation. A hub of collaboration between universities, institutions, companies, and communities. A city without gates, without borders, without pause, in constant movement of welcome and departure. A city of citizens who are never still, citizens of the world who recognize themselves and meet in Venice, working on future projects and building new connections between ancient and new. Glass is like the Lion.

Venetian glass is not just a symbol of all this. It is a true material for study and for design in architecture, art, design, fashion, and above all, cultures. Venice is a center of excellence where knowledge about glass grows. But also a place for experimentation, hybridization, and contamination.

Studying glass means studying light, transparency, resistance, and form. It means studying the relationship between artisanal tradition and industrial advanced production, between heritage and the future. This is why Venezia Città Campus can become an international hub for the study and design of glass. A place where students and researchers from all over the world meet to deepen technologies, languages, and materials. A place where glass returns to the center as a cultural and environmental resource.

OVER-TIME GLASS was a valuable opportunity for international exchange and dialogue: in just a few days, between Venice and Murano, a temporary community of students, professors, researchers, and professionals came together, united by a shared passion for glass, design, and knowledge.

We would like to thank the lecturers who generously shared their lessons, reflections, and visions with the students: Aki Ishida, Edward Schmit, Emilio Francesco Orsega, and Stefano Centenaro. To them goes our deepest gratitude, along with an invitation to consider OVERTIME GLASS as a prototype: a first step toward continued collaboration and the forging of new, shimmering glass projects.

This cultural and educational exchange—an experience of design and inspiration—was made possible thanks to the generous collaboration of many organizations who contributed with openness, enthusiasm, and vision. We would like to thank the Officina Cultural Association, the Consorzio Promovetro Murano, rehub, Artigianato Muranese, the Proto and all the offices of the Basilica of San Marco, the FAI – Fondo per l’Ambiente Italiano and the staff of the Olivetti Shop in Piazza San Marco, the Iuav staff who welcomed us at the Tolentini Library, and the Gallerie dell’Accademia.

A special thanks goes to the BarMan studio, which opened the doors of Palazzina Masieri, to Adriana Casalin for welcoming us into the ArTec materials library, and to Maria Gatto, Claudia Capunao, and Gianluca Zucconelli of the Iuav International Office, for their invaluable support.

Finally, our heartfelt thanks to Anna Lorens and Laura Patachi, whose enthusiasm gave shape to all of this, turning it into an intense and generous Erasmus+ BIP project.

Here it is possible to find any information and news about Cluster GLASS activities: www.sites.google.com/iuav.it/iuavcluster/glass www.instagram.com/iuav_glass/

The OFFICINA* association was founded in January 2015.

The cultural project was born in 2013 thanks to the drive of the three founding members, doctoral students in New technologies for the territory, the city and the environment (field of Architectural Technology) at the Iuav University of Venice, who started the first initiatives of the group within the ArTec laboratory (Archive of Techniques and Materials for Architecture and Industrial Design). During the first year of activity the OFFICINA* group grew with the participation of new doctoral students and research fellows, thus giving consistency to the project which in the first months of 2015 was transformed into a cultural association.

This has as its primary intent to put the world of research in communication with that of the company, the profession and more generally the community, in order to establish and promote a dialogue and discussion on topics related to architecture and building technology.

The main areas in which it operates are the redevelopment of the existing, environmental, economic and social sustainability, the valorisation of the territory and technological innovation, with particular attention to issues related to energy efficiency and the appropriate use of materials and construction technologies.

For information: www.officinajournal.it officina.rivista@gmail.com