SOAP

® ANT AND INSECT BAIT

Powerful disease protection for your fruit and vegetable crops with a fraction of the copper found in other copper fungicides.

The soft-bodied insect specialist. on contact in a wide range of

A summer and dormant oil. Controls all life stages of insects and mites, and supresses powdery mildew. from the ground up.

A durable iron phosphate crop protection from slugs

A durable, fast acting spinosad bait, active against a variety of ants, cutworms, spotted wing drosophila and wireworms in a wide range of crops.

We’ve passed the one-year mark of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the rug was pulled out from under the industry at a crucial time of year. While the rules for gatherings, businesses and foreign labour continue to shift regularly, the uncertainty with which the 2020 growing season began was, thankfully, lessened in 2021.

To help mitigate this in our own way, Fruit & Vegetable hosted the first Canadian Fruit & Vegetable Summit in March. We created the Summit to provide growers with up-to-date production tips and industry insights to start the season off on the right foot. With three panels featuring growers, researchers, provincial crop specialists and processing organization representatives from across Canada, there was certainly an abundance of experience and knowhow on display.

In a happy bit of synergy, the United Nations General Assembly designated 2021 the International Year of Fruits and Vegetables. According to the U.N., this was done

pandemic on the industry last year, and how producers and other sectors plan to approach the coming year with this in mind.

I admit to being surprised by how optimistic the speakers were about the future of their operations and the industry more broadly. It can be easy to get caught up in the negatives and challenges – especially when some are so complex and require so much change. But, as discussed by Evan Fraser, director of the Arrell Food Institute at the University of Guelph, and Pascal Forest, president of the Quebec fruit and vegetable processors’ organization, rising awareness of sustainability, food sovereignty and quality, and the importance of fruits and vegetables to a healthy diet are all beneficial in achieving a bright future.

If you’re interested in checking out the Canadian Fruit & Vegetable Summit, the recorded panels are now available to watch at fruitandveggie. com/virtual-events/canadian-fruitvegetable-summit/. In addition to the three live sessions, be sure to check

Some challenges are complex and require so much change.

as an opportunity to raise awareness on the important role of fruits and vegetables in human nutrition, food security and health. As the purveyors of fruit and vegetables to Canadians and export markets, you are essential to this goal.

With the COVID-19 pandemic lingering into this year, food systems will continue to shift to match changing demands and consumer desires. Two major topics of the Summit were the impacts of the

out the two on-demand sessions, as well. Ag editor Bree Rody discusses spotted-wing drosophila with AAFC knowledge and technology transfer specialist Jesses MacDonald, and ag editorial director Stefanie Croley chats with Evan Elford, OMAFRA’s new crop development specialist.

Whatever your challenges are this season – weather, labour, markets or otherwise – here’s hoping you’re able to tackle them and come out on the other side successfully. •

519-429-3966

905-655-6626

519-410-4854

519-429-5175

Broad-spectrum disease control that lasts.

You go to great lengths to protect your apples. So does new Merivon®. It’s the advanced fungicide that helps maximize yields with broad-spectrum disease control and two modes of action. But it doesn’t stop there. Merivon also offers unique plant health benefits and extended residual. Because like you, Merivon was made to go the distance. Visit agsolutions.ca/horticulture to learn more.

A new mental health awareness training program specifically for farmers will soon be available to rural and agricultural communities across the province through a partnership of the Ontario Federation of Agriculture (OFA), the University of Guelph and Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA), Ontario Division.

In the Know is a mental health literacy program developed at the Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph, created specifically to educate the agricultural community. The halfday training will be delivered online until public

health measures allow for in-person delivery.

The course provides education on topics such as stress, depression, anxiety, substance misuse and how to start a conversation around mental well-being. CMHA Ontario will be working closely with the OFA, the province’s largest general farm organization, to ensure maximum outreach and benefit to Ontario’s agricultural community.

In the Know training is being made available through CMHA branches thanks in part to a generous donation from Trillium Mutual Insurance.

In late February, MarieClaude Bibeau, minister of agriculture and agri-food, announced the membership of the Canadian Food Policy Advisory Council, a central component of Canada’s food policy.

The Canadian

Food Policy Advisory Council’s 23 members bring together diverse expertise and perspectives from across the food system, including the agriculture and food sector, health professionals,

academics, and nonprofit organizations. Members also represent Canada’s geographic and demographic diversity.

The Council will advise Bibeau on current and emerging food-related issues that matter to Canadians. This advice will reflect the integrated and complex nature of Canada’s food system, and support improved and sustainable health, social, environmental and economic outcomes.

Efficient and complete burndown of annual grasses and broadleaf weeds. When it comes to controlling weeds, you don’t have time to mess around. That’s why there’s Ignite® herbicide. It provides proven and complete burndown of annual grasses and broadleaf weeds within 7 to 10 days in a range of crops, including tree fruit, blueberries and grapes. And as an additional bonus, Ignite also prevents sucker growth. So what are you waiting for? Visit agsolutions.ca/ignite today.

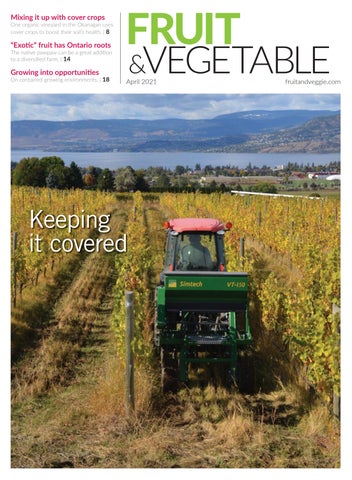

One organic vineyard in the Okanagan attributes their healthy soil to cover crops.

BY TOM WALKER

Growing cover crops in vineyards is an increasingly popular practice for Canadian grapegrowers. They have a long list of positives for viticulture but cover crops have been particularly successful for one Okanagan grower.

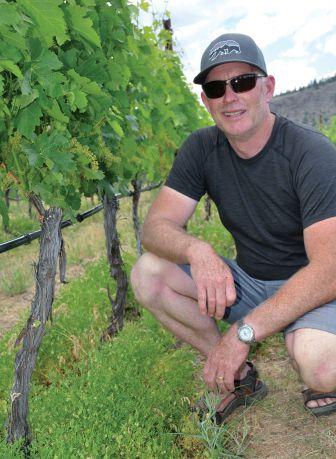

Gene Covert did not have to add any nitrogen to his vineyard last year and he plans to do the same this year as well. “We did really extensive soil testing in the fall of 2019 and decided that we had enough fertility in the soil that we would go for it,” says Covert, who owns Covert Farms, an organic vegetable farm and a 32-acre organic vineyard and winery, just north of Oliver, B.C. “We figured if we saw that the vines were suffering, we could add some compost during the summer, but we didn’t need to.”

ABOVE

Covert says the results of soil tests from late November 2020 show he will be able do the same for the 2021 season. According to him, the health of his soil is largely due to the cover crops he has been growing over the past five years.

Growing a crop to cover the soil next to a harvest crop has a long list of advantages. Cover crops can help protect the soil from erosion, reduce soil compaction and moderate temperatures. They can improve soil structure and soil health, particularly by adding organic matter. They can improve the water penetration and water holding capacity of the soil as well as improve the biodiversity of the vineyard, which may support beneficial insects. And overall, they contribute to nutrient supply.

Having a vegetative cover between vine rows or in “alleyways” is a pretty standard practice for grape growers, particularly in B.C., where there is an industry-led sustainability certification program and upwards of 30 per cent of all vineyards follow organic principles. But what sets Covert Farms apart is their use of under-vine crops.

“We started with the under-vine plantings five years ago, partly to cut down on the six tilling passes we were doing for weed control,” Covert explains. “Now that we have stopped tilling, that’s a huge saving – not only in time and fuel, but it is also better for the environment. The more we work with cover crops, the more benefits we see.”

Covert has a plant mix that he has developed over time that suits his sandy soils and the desert-like summer conditions of the south Okanagan valley.

“Getting a mix that works for your conditions and the role you want it to play in your vineyard is important,” says Kathryn Carter, tender fruit crop specialist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA). She says many Ontario growers will alternate cover crops and sod between rows, but are moving more cautiously into under-vine plantings. “With our heavier soils and more moisture than B.C., we have to be careful that a cover crop is not too vigorous to interfere with the vines.”

In Prince Edward County, Ont., where growers bury their vines in winter, they need a cover crop they can easily pull back in the fall to dig in their vines and establishes quickly again in the spring, Carter adds.

Different cover crops play different roles in your vineyard. If you are looking to improve soil structure and mitigate compaction, grasses, clovers and radishes will help. Legumes produce nitrogen, and if your goal is to crowd out weeds, winter rye and buckwheat are your best bets.

Mehdi Sharifi, research scientist at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s (AAFC) Summerland Research and Development Center in B.C., has worked with Carter in the past to screen cover crop mixes that would be suitable for Ontario vineyards. “It’s a topic that everybody is interested in, but it’s a lot of work,” Sharifi says. “For the studies I am doing in the Okanagan right now, I have 280 separate plots on the go at once.”

Covert Farms has three different seeding regimes: one for fall, early

ABOVE

ABOVE

spring, and early summer. A no-till seed drill is used and, while most Okanagan vineyards have overhead irrigation as well as drip, Covert gets by with just their drip system. “We are essentially dry-farming our alleyways,” he says. “We know that a mix of plantings is better for dry conditions, and a mix also provides a balance between soil bacterial and fungal development.” Winter peas, lentils, triticale, daikon radish and hairy vetch go into the alleyways in the fall and are terminated in early summer before they seed out. June is usually rainy in the Okanagan, so Covert says it’s a good time to reseed with warm season legumes

and C4 grasses that will last through the summer.

“I have five different species of lentils that I seed under the vines in the spring, as that is when I get the best take,” Covert says. “That under-vine crop is probably augmenting about half of our nitrogen and the rest is coming from the alleyway plantings.” He also adds some Oriental mustard. “That gets me an early growth, and I think mustard helps with cutworms.”

Depending on the effect he is looking for, Covert says he either mows the vegetation at very low RPMs to break off the stems, or uses a roller crimping implement to crush down the plants. “The rough overstory really helps to release nutrients slowly, while giving some shade to the vine roots from the summer heat,” he explains.

Sharifi says that while the practice of cover cropping is extensive, there is not a lot of research on the actual changes they cause in the vineyard. “We need to study the effects that cover crops have on yield, grape quality – including sugars and phenolics – and their role in disease and pest control,” he says. “I know that Covert Farms has seen a reduction in powdery mildew in some of their blocks. We need to work more to understand the mechanism that is supporting that.” He adds that with climate change, it is also important to understand how cover crops support the vines in the heat of summer and help with cold hardiness in the winter.

“Cover crops check off a lot of boxes for us in terms of soil health and reducing our need for inputs, especially nitrogen,” Covert says. “As we learn more over time, we are finding that multi-species cover crops are a lot more than the sum of their parts.” The vineyard also follows regenerative practices and grazing animals between the vines compliments the cover cropping.

Covert says soil testing gives him an indication of what is going on. “The tests are gratifying, but the real validation is the vine health and vigour through the season,” he says.

One thing he knows for sure is that the experimentation will continue. “A lot of the reading I have been doing lately says to not scrimp on the seeding; the biomass is important. I have different seeding rates in different blocks, and some that were 20 to 30 per cent higher seemed to be perfect,” Covert explains. “Now we just have to do it again.”•

Regenerative agriculture is a term used to describe agriculture that not only sustains ecological health but improves it over time. Though many farmers have aspired to achieve some version of this for decades, the term itself has gained new traction in recent years due to its potential to mitigate the effects of climate change. Despite that, no clear or specific definition exists which catalogues a complete list of practices and techniques.

More recently, regenerative agriculture has been lauded for its ability to reverse the effects of climate change through its focus on promoting soil health and sequestering carbon. To this end, the Organic Council of Ontario (OCO) recently conducted a feasibility study that examined the various programs currently emerging on the market that measure, certify and verify regenerative and regenerative organic agricultural practices and their potential for adoption in Ontario. Programs assessed include the Regenerative Organic Certification (ROC), the Ecological Outcome Verification (EOV), the Soil Carbon Initiative (SCI) and more.

The final report for the Regenerative Programs

and Incentives Feasibility Study compares and summarizes each program and its potential barriers, benefits and implications for Ontario’s producers and consumers.

Regenerative certification programs vary in their approach, but most measure or quantify similar ecological attributes of a farm, including increasing soil health and carbon sequestration, biodiversity and ecosystem health, increased animal welfare and economic resilience; some also include worker fairness.

Certain programs build organic standards, such as the Regenerative Organic Certification (ROC), which acts as an umbrella for high level certifications. ROC uses organic certification as a baseline, and incorporates additional existing certifications for things like animal welfare and worker fairness in a tiered system to avoid duplication. Although a farmer may achieve bronze, silver or gold status, the program provides

an overarching label that aims to incentivize and communicate the highest standard for certifications currently available. This program appears to have the most potential and success with brands, larger producers and processors who depend on labelling to build trust and create value, which smaller producers can achieve via direct communication to consumers. It is also available to all producers and food processors, with program costs reflected in a capped percentage of gross certified product profits.

ABOVE

Others take a different approach, focusing on outcomes rather than standards-based practices, like the Savory Institute’s Ecological Outcome Verification (EOV) and its “Land to Market” label. The EOV measures the outcomes of good land stewardship, specifically focusing on soil health metrics to verify positive practices. Where this program proves to be strongest is its potential for customization: progress is measured against a baseline of initial data and observations collected from the participant’s specific land plot and compared with an established local reference area. In general, this program measures continued land regeneration and ecosystem improvement through various metrics and individual assessments. A drawback to this program is that it is currently only applicable to pasture-based systems including meat, wool, dairy, and leather production. EOV is currently conducting pilot studies to expand production types that can take part in the program.

Other programs that depend on self-reporting through online platforms are also in the works, including the Soil Carbon Initiative (SCI) and the Canadian Agri-Food Sustainability Initiative (CASI). Both have the goal of communicating best practices across the value chain and creating connections while boasting flexibility and usability for producers. Both programs are currently in their beginning stages, but they are expected to be launched within the next few years.

Among the significant barriers to adoption of these programs are time, cost and a lack of resources and education. Without widespread adoption and recognition of the program labels, however, these programs will do little to provide a significant market incentive to Ontario producers.

All of these programs have one thing in common; their ability to aid producers in making important management decisions. The need for accurate record-keeping and monitoring of the land’s health helps to build connection and awareness. As well, the diligent records and observations required may be highly valuable management tools that demonstrate progress over time and potentially highlight the need for changes or improvements.

Programs measuring regenerative and regenerative organic practices can certainly exist alongside organic certification or, as mentioned above, organic certification can act as a baseline requirement. Both the ROC and EOV have officially stated they are not in competition with one another, but working towards the same goal to provide producers with the ability to communicate practices that may not be measured in organic certification. In fact, some producers are taking part in multiple programs at once.

One niche that regenerative certification programs can fill is highlighting more climate-friendly agriculture in Ontario and the world. Programs that measure and certify are a clear way to communicate positive practices, especially throughout the value chain. Campaigns targeting consumer awareness of the positive effects of regenerative and regenerative organic practices will drive the demand and market for more climate-friendly products, possibly moving the needle in the right direction to capture agriculture’s potential to help reverse climate change.

To read the final report of OCO’s Regenerative Programs and Incentives Feasibility Study along with other published reports, including the Certification Supports for Small-Scale Producers Report, go to www.organiccouncil.ca/downloads/.

The Organic Council of Ontario (OCO) represents more than 1,400 certified organic operators, as well as the businesses, organizations, and individuals that bring food from farm to plate. OCO works to catalyze sector growth, support research, improve training, increase data collection, encourage market development, protect the integrity of organic claims, and inform the public of the benefits and requirements of organic agriculture. •

Experts agree that pawpaw makes a great addition to a diversified farm.

BY JODI HELMER

A tree producing fruit that tastes like a combination of mango and banana might seem best-suited to a tropical climate, but the common pawpaw (Asimina triloba) is native to southwestern Ontario; it can also be grown in southern British Columbia and Quebec.

Although the pawpaw is considered one of the oldest native fruits in North America, wild plants are teetering on the brink of extinction. Growers, recognizing the potential in the sweet, custard-like flesh of the fruits, are helping bring the pawpaw back.

“There are over 45 selected varieties and improved cultivars on the market,” says Evan Elford, new crop development specialist for the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural

Affairs (OMAFRA). “In Ontario, we have a few growers experimenting with improved cultivars, but most of the work being done is on native seedlings selected from wild plantings.”

In the past two years, Elford has fielded calls from growers interested in establishing commercial pawpaw production, but the cultivated orchard setting is still an emerging industry.

Ken Taylor started growing pawpaws at Green Barn Farm in Notre-Dame-de-l’Île-Perrot, Que., 25 years ago, but it took a lot of trial and error to produce viable nursery stock.

“I brought seeds in but most didn’t germinate, so

ABOVE Pawpaw trees at the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada research station in Harrow, Ont. INSET A small cluster of pawpaw fruit just starting to grow.

Most people seek help when they need it.

shouldn’t be any different

It’s time to start changing the way we talk about farmers and farming.

To recognize that just like anyone else, sometimes we might need a little help dealing with issues like stress, anxiety, and depression. That’s why the Do More Agriculture Foundation is here, ready to provide access to mental health resources like counselling, training and education, tailored specifically to the needs of Canadian farmers and their families.

make adjustments as needed,” Kottegoda says.

The systems are effectively a turn-key production system for retailers. All store staff need to do is harvest and package the plants for purchase. Herbs and microgreens can be sold as plugs for replanting at home or harvested and packaged for immediate consumption.

Sobeys isn’t the first grocer in the world to embrace the system. InFarm has more than 1,200 locations in 10 countries, double the number a year ago. It recently partnered with Amazon-owned Whole Foods to roll out the system in the UK.

Contained farming systems are also being used to help farmers put down roots in places that would otherwise be unsuitable for production. Green Lion Farm Ltd. of Armstrong, B.C., expects to have 16 growing machines from CubicFarm Systems Corp. of Vancouver in operation this spring. Green Lion owners Mark and Lesley Van Deursen saw CubicFarm’s growing machines as a way to add herbs and leafy greens to their existing organic forage operation and contribute to local food security.

“We’re just really passionate about sustainable agriculture,” Lesley Van Deursen says. “We feel like it has really good potential for growing lots of things in the future and really, promisingly impact food security issues.”

The insulated growing chambers are about the size of a 40-foot shipping container. The operating system is embedded in the walls, freeing the interior space for a conveyor that carries more than 250 growing trays along an undulating path under lifegiving light and nutrient-rich water. Workers access the crop at one end, harvesting mature plants and restocking trays with plugs for the next growing cycle. The system is ideal for plants no more than 10-inches tall, with tray configuration matched to crop.

The custom-made growing chambers are cost-effective for a small producer, averaging between $125,000 and $175,000 each. Production ranges from 6,240 heads of lettuce every 21 days or 20,640 plugs of herbs every 10 days. The productivity delivers sufficient cash flow to cover capital and operating costs. It’s also simple to operate, with adjustments to the growing environment made through the GrowLink farm management app.

“You can set up these container-style growing systems anywhere in the world and you don’t need the landbase,” Van Deursen says. “It really is quite awesome to be able to supply our local grocery store chains and restaurants with domestic produce.”

While the compact nature of the CubicFarm systems helps the Van Deursens make better use of their land in the interest of local food security, it also operates just a half-hour drive from one of the largest organic vegetable farms in the Okanagan. VegPro International Inc. of Quebec acquired 700 acres near Vernon, B.C., in 2017 to grow salad greens for markets in Western Canada. One of the site’s key attractions was the temperate climate and low pest pressure.

Container systems are independent of soil or natural light, preventing organic certification. Demand for organic produce means soil-based systems aren’t going away. Field producers shouldn’t fear the new alternative, according to Lenore Newman, director of the Food and Agriculture Institute at the University of the Fraser Valley in Chilliwack. Newman is also a member of B.C.’s government-appointed food security task force that examined the potential of agritech in meeting future needs.

“It’s not great for the field producers who are in the same category,” she says. “[But] the truth is, there’s a lot of field crops that are not going to work inside. So it’s not like field producers will be short of things to grow.”

The key opportunity for contained growing environments is closing the distance food has to travel to people’s tables. This is most evident for crops commonly consumed year-round, a demand now met by imports.

“It’s very interesting how fast the technology is evolving, and it does open up the potential that Canada could be self-sufficient in fresh greens, small fruits, small vegetables,” Newman says. “Everyone’s playing to see what will be the winning combination of size, location, crops.”

While there’s plenty of research that supports one-acre facilities in places like Japan and the Netherlands, there’s far less research into the economics of shipping containers or hyperlocal systems, such as InFarm.

James Eaves, an agricultural economist and professor in Laval University’s department of management, has studied the economics of vertical farms versus greenhouse production. Research three years ago found that start-up and operating costs are similar, while the gross profit is slightly higher for vertical farms. Reductions in LED lighting costs have only added to the advantages for high-value crops, making contained systems more attractive than greenhouses in many contexts.

“Throughout history, growers have always paid a very high premium for improvements in control. This is why I believe the indoor growing will disrupt much of the greenhouse market in Canada over the next decade,” Eaves says. “I’m hoping stakeholders see the writing on the wall before we lose the opportunity to lead in that new and incredibly large future market.”•