My e-mail has just been humming over the past month or so with the latest agriculture funding announcements from the federal government. And it’s been a crazy busy time for the funding of horticultural projects.

It all started with an announcement from the feds in late February involving funding for cover crop research, specifically in the area of processing vegetable production. More than $230,000 in funding was presented to the Ontario Processing Vegetable Growers through the Canadian Agricultural Adaptation Program (CAAP), a five-year program aimed at helping Canadian agriculture adapt and remain competitive.

A few days later, a second announcement arrived detailing more than $300,000 in financial support being provided to P.E.I. Juice Works Ltd. to help the company develop and produce a wild blueberry juice. A small amount of the money would be sourced through CAAP with the rest coming from the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency, Innovation P.E.I. and P.E.I.’s Growing Forward Innovation Program.

A few weeks later, P.E.I.’s potato industry received a $350,000+ shot in the arm to help the P.E.I. Potato Quality Institute expand its facility. The funding came through the feds, the province’s agriculture ministry and the P.E.I. Potato Board.

The next day, on the opposite side of the country, it was announced that B.C.’s cranberry sector would be receiving more than $200,000 to test new varieties and provide growers with the necessary information to increase productivity and profitability. That funding also came through CAAP.

But just a few days later, in late March, the Canadian government’s 2012 budget was released, outlining more than $300 million in cuts to Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, most occurring in the Canadian Food Inspection Agency area. Given this turn of events, I thought the horticultural funding announcements would dwindle down to normal rates. I was wrong.

By mid-April, the federal government’s money tree must have been in full bloom because $2.5 million in funding was announced for Canadian Prairie Garden Puree Products Inc., a Manitoba food processing plant that produces vegetable purées for soup and baby food. This was the first project to be funded under the Agricultural Innovation Program, described as the next phase of Canada’s Economic Action Plan.

A few days later, New Brunswick’s potato growers received news they would be receiving financial aid from both the feds and the province for “excess moisture” conditions that occurred in 2011. Payments of $182 per acre are available to potato growers who can demonstrate they incurred significant additional costs from spraying and other work associated with the disaster. The funding is being delivered through the federal/provincial AgriRecovery fund with additional financial assistance possible through AgriInsurance, AgriStability and AgriInvest.

Mere days later, an announcement came through that the Saskatchewan Food Industry Development Centre had received $200,000 for new processing equipment to provide additional capacity for fruit growers

May 27-29, 2012 – Canadian Institute of Food Science & Technology National Conference, Niagara Falls, Ont. Visit www. cifst.ca

June 28, 2012 – The Stokes/Veseys/Hort Nova Scotia Annual Golf Tournament, Berwick Heights, N.S. Visit www.hortns. com

July 4-5, 2012 – Southwest Crop Diagnostic Days, Ridgetown College, Ridgetown, Ont. Visit www.diagnosticdays.ca.

July 11, 2012 – Potato Growers of Alberta Gold Tournament, Paradise Canyon Golf Resort, Lethbridge, Alta. Visit www. albertapotatoes.ca.

and clients.

A little less than a week after that, Hinterland Wine Company Ltd. in Prince Edward County announced it had received a small amount of funding through the AgriProcessing Initiative to help purchase new equipment to enhance wine flavour, maintain greater product quality control and provide shorter production times. A portion of the $42,000 is to be repaid to the government.

And these are just the announcements up until late April. Here’s hoping the gravy train for hort continues.

In other news, the provincial agriculture ministers met with federal ag minister Gerry Ritz in late April to discuss the newest phase of the country’s agriculture policy framework. The group decided to focus on innovation, competitiveness, market opportunities, adaptability and sustainability within the sector, and is calling for stronger partnerships between government and the private agriculture industry.

Meanwhile, University of Guelph professor and agriculture economist John Cranfield is calling for more government funding to be spent on agriculture research as it is falling behind that of other countries.

If the most recent funding announcements from the federal government are any indication, that won’t be happening soon. Instead, it would appear funding proposals involving hot-button items, such as innovation, marketing, competitiveness and sustainability will be receiving government backing. And, if your projects aren’t fitting within these parameters, they might not be funded.

July 12, 2012 – FarmSmart Expo, Elora Research Station, Elora, Ont. Visit www. uoguelph.ca/farmsmart/expo.

July 12-14, 2012 – Canadian Fruit & Vegetable Tech X-Change, 1195 Front Rd., St. Williams, Ont. Visit www. fruitvegtechxchange.com.

By Hugh McElhone

Late blight is an important topic that scares us all, and its devastation of tomato crops can be widespread, says Dr. Tom Zitter, a plant pathologist with Cornell University based in Ithaca, N.Y.

The epidemic that occurred in U.S. tomato crops during 2009 was unique because it began so early in the season and occurred so evenly over such a large geographical area, something that never happened before. Another feature of the epidemic was that a new genotype of the pathogen was responsible – US-22 – and was capable of infecting both tomatoes and potatoes. To be sure, the principal genotype affecting potato at that time – US-8 – was also present in New York State, but affected only limited potato acreage. Genotype US-8 is limited to potato and most likely originated from infected tubers used for seed for the 2009 crop.

So why is late blight important? asks Dr. Zitter. When he and Dr. Bill Fry began their 2009 study, the disease had likely got its start in Florida in May 2008, then started working its way north.

Dr. Zitter’s first encounter with this strain was on June 24, 2009, when a colleague brought him some samples to identify the pathogen on the leaves. The plants came from the garden section of a local big-box store.

That same afternoon, Dr. Zitter visited the four big-box stores in Ithaca and found their tomato plants were infected with late blight, but no infection was found at five local garden centres that had grown their own plants or had received them from other suppliers. He advised some customers against buying them at the big-box stores and also spoke with the store managers, who said they got the plants on consignment. They said they would speak to the supplier and ensure the plants were removed by Saturday.

Dr. Zitter returned to the same stores the next Saturday and the plants at that provider were gone. He felt reassured, but only briefly. When the other stores around the state realized they had a problem on their hands, some centres put their plants on sale for half price. “By that time we already knew we had an epidemic; the genie was out of the bottle. By the middle of August of that same year the

disease spread was statewide,” he says.

Potatoes usually get late blight first but in 2009 it was the tomatoes, and the primary source for spreading the disease was the unknowing home gardener. The onset was very early in the season and the environmental conditions were highly favourable for late blight from New York up into Maine.

Commercial growers had to go on a crash course of spraying every four to five days, as did organic growers, who were actually able to control it by removing infected plants and using regular sprays of copper, he says.

Homeowners could not respond in such a manner and lost all of their plantings to late blight.

Of the late-blight strains that existed in 2009, Dr. Zitter says there was homogeneity that existed among the isolates since they represented the same clonal lineage. “You could almost put a bar code on the genotype because they were identical, they all behaved the same way, which is critical for identification.”

He adds that strains today have a much wider host range, with different genotypes,

Researchers at Cornell and other universities are developing new cultivars that are resistant to or offer good tolerance to early blight, late blight as well as this disease, Septoria leaf spot.

asexual reproduction and clonal lineages. These lineages may be more aggressive toward both tomato and potato. “With the new techniques that are available today, we can test a sample and within 24 to 48 hours we can tell what genotype it is,” he says.

In terms of the host range for late blight, it can infect plants such as petunia, hairy nightshade, tobacco and pepino (all members of the Solanaceae plant family) to name a few. This is a very wide host range and Dr. Zitter says that when he does greenhouse tours he always checks petunias in addition to tomatoes to be sure that late blight is not present.

“This is not the same disease that your father or even your grandfather knew because back then they were dealing with only US-1 (mating type A1) and it was only a concern for commercial potato growers,” he says.

During the early part of 2000, US-7 and US-8 were the main concern in potato and were of the A2 mating type. For tomato growers the lineages of concern were US-11 and -17 (both A1 mating type), with a limited preference for potato. All of these lineages showed resistance to the fungicide Ridomil, which had been the silver bullet available in the early 1990s when US-1 prevailed.

Fast forward to present day when growers need to be aware of the potential concerns for US-8 (A2, potato only), US-22 (A2, both crops), US-23 (A1, both crops) and more recently US-24 (A1, potato only). Fortunately US-22, -23, and -24 are all sensitive to Ridomil as determined by the Fry lab.

“Also, with many new chemistries, there are a plethora of new products available to help in emergency situations. Just make sure you rotate your chemicals,” he says.

Unfortunately, says Dr. Zitter, conditions on the battlefield have changed since the arrival of US-22, the strain that has infected both tomato and potato crops in the eastern United States and southern Canada from 2009 to 2011. “The isolate does have some staying power and can be expected this year

as well,” he adds.

“When it was first identified, US-22 was found to be sensitive to Ridomil, and if we had known the genotype then, we could have advised growers to use one spray of Ridomil, which would likely have stopped it dead in its tracks. That’s why it’s so critical to know what genotype is at work in your field or in your greenhouse,” he says.

For potato growers, applying Ridomil alone in-furrow is not labelled for this use because it is difficult to get even coverage on the seed piece, but if mancozeb is applied to the seed tubers it will reduce the risk of the disease spreading from tuber to tuber prior to planting. “This is important not only for them but for tomato growers as well given the number of genotypes that move from one crop to the other,” he says.

Also new to the field since 2010 is US-23, which infects both potato and tomato rather aggressively, and is expected in 2012. It is sensitive to Ridomil. In 2011, it was first reported in Connecticut, then on Long Island, after a transplant grower was told he had late blight and reacted by destroying all of the plants that displayed the symptoms but keeping the ones he thought were clean. Shortly thereafter the inoculum on these plants reproduced and eventually spread to a number of New England states, and as far south as Pennsylvania.

“With US-22, US-23 and US-24, the big scary point we don’t know yet is about sexual reproduction because when you get the two mating types in the same field you certainly have the potential of their sexual mating and recombining into a different assortment. Subsequent oospore production means they have the potential to overwinter, which growers in Ontario might face on an annual basis. In New York, we used to see late blight about every five years, but that has changed in the last few years,” he says.

As to the future, Dr. Zitter says there are many unknowns. The organism is changing

and the bottom line is that the plant breeders really need to focus on developing plants resistant to late blight.

For tomato growers and homeowners looking through seed catalogues, they want tomato cultivars that have both Ph2 and Ph3 genes for maximum late-blight resistance. “If it’s just Ph2 you can expect that late blight will develop,” he says. Some resistant varieties developed with both genes have performed well, including Mountain Merit and Defiant PhR for large reds, and Mountain Magic F1 for large cherry (a Saladette or Compari type).

Researchers at Cornell, other universities and some commercial breeders are working on new cultivars that are resistant or offer good tolerance to early blight, late blight as well as Septoria leaf spot. New crosses are being developed that confer high levels of genetic resistance for early blight and Septoria leaf spot that will allow for disease control with minimal or no fungicide applications, especially if a two-year rotation out of tomato is practised. He hopes new hybrids will be on the market in the next two years.

A national website, www.usablight.org/, is regularly updated by national contributors to pinpoint where late blight is currently reported, and growers are encouraged to log in. The site will even send messages to cellphones to tell growers when late blight is in their area. “It is timely information that you can use, and by the time it is posted, you will actually know what genotype it is so you can determine what kind of corrective action to take,” he says.

For updated information on the use of TOMcast ™ for determining the need for sprays to control early blight, Septoria leaf spot and anthracnose, visit the site at www.weatherinnovations.com/tomcast.cfm.

The competition at the Ontario apple cider contest remains fierce with strong competitors perfecting the right blend to please the palates of judges and consumers alike. This year’s competition saw a surprise upset by last year’s underdog taking first place this year at the Ontario Fruit and Vegetable Conference, Niagara Falls, Ont.

“Last year we placed third and, while it was nice to get an award, I figured we could do better. There’s always room for improvement,” said Ray Ferri, of Al Ferri & Sons Country Apple Store on Heritage Road in Brampton, Ont.

The store was named for their father, Aldo, and the sons Ray and Jim are the third generation to operate the farm their parents bought in 1945.

Their family members also deserve great credit for keeping the farm and store in topnotch condition, says Ray.

“I don’t know who to begin to thank,” he said. We couldn’t do what we do without our family, he added.

“I’m very pleased with this year’s contest, and we intend to keep running it, with the Ontario Apple Growers sponsoring it,” said Leslie Huffman, apple specialist for the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA).

“My goal in organizing the competition is to highlight the great product that our cider makers produce, and to encourage continual improvement in cider making,” she said.

“We had nine entries this year, and although I was not a judge, I tasted them

By Hugh McElhone

all, and think they had improved from last year … it’s the balance and taste that make a winning cider. I know the top ciders were very close, and I’m glad I wasn’t a judge,” she added.

Balance and taste are paramount to Ray and Jim.

“The cider submitted this year (to the contest) was similar to last year, an offthe-shelf jug. I adjust every batch to taste and I always go for the same taste. It is difficult to say there’s any difference other than the growing conditions for each year, although the age of the apples does have an effect,” said Ray.

“The cider is always made for our customers. Consistency is what drives sales. Winning a contest like this, well, that is icing on the cake,” he added.

“I’d like to mention the feedback I get from people when I tell them about the cider competition,” added Huffman. “Many mention how they really like the cider, and think the competition is a good idea, and some even volunteer to judge,” she said.

“I was pleased to see the positive com-

ments on Twitter around the competition this year (at the OFVC), as several judges and participants were talking about the competition and cider in general,” she added.

Long before this apple cider competition began, Ray and Jim remember well their father buying the farm’s first cider press in 1975 when apple prices were depressed.

To help feed the young family, their father started pressing apples into some really good cider that the customers enjoyed and remembered. Following in Aldo’s footsteps, his sons carry on the family tradition today and produce some really great apple cider, the sort of cider that was recently awarded as the best in Ontario.

“We feel proud about this recognition, though this is really a win for my mother and my father who started this business and who taught us how to do it right,” says Ray.

“Their pictures hang in our store to remind us who started this business and where we came from,” he concluded.

DuPont™ Altacor® insecticide delivers long-lasting insect control in caneberries, grapes, pome and stone fruits, tree nuts and now, blueberries too. Say goodbye to oblique-banded leafroller, codling moth, grape berry moth, climbing cutworm, oriental fruit moth and others. Powered by Rynaxypyr®, Altacor® sweeps away these damaging pests, with minimal impact on bees and beneficials to protect your high-yielding, high-quality crops.

Questions? Ask

By Hugh McElhone

As many cole crop growers know, clubroot can be very destructive to the brassica family, says Dr. Mary Ruth McDonald, professor of plant agriculture at the University of Guelph, Guelph, Ont. This large family includes such familiar members as rutabaga, kohlrabi, cabbage, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, mustard, bok choy and even rapeseed.

Clubroot is not caused by a fungus but rather by protozoa, which helps explain why the fungicides designed for other soil-borne diseases do not work well for clubroot. The resting spores can lie dormant in the fields for a very long time and awaken when cole crops are planted.

“It tends to thrive when you have a warm, wet climate and acidic soil,” she says.

Once awakened from its dormant phase, the disease soon produces zoospores that swim through water-soaked soils to find and infect the plant’s initial fine root hairs, Dr. McDonald explains. There they rest and produce a fresh flush of new zoospores. This fresh flush later attacks the primary root of the main plant where they nest and multiply again. The protozoa cut off and divert the root energy and nutrients to themselves, leaving the plant with a clubroot. This causes stunting or death for infected plants.

For many years, crop advisors have recommended avoiding infested, wet fields and doing a long crop rotation every five to seven years. Another tactic is to increase the soil pH to 7.2 or above. These measures work for many growers but not all, she says.

In a controlled laboratory environment, University of Guelph graduate student Hema Kasinathan has run trials with canola, an immediate brassica relative of rapeseed, through the paces of temperature, pH and soil moisture.

In this controlled environment, research was conducted on a soil pH range of 5 to 8, with air temperatures of 10 to 30 C. It was soon discovered that plants at 10 and 30 C did not fare well and were dropped from the study. The remaining canola trials were assessed six weeks after inoculation when there was plenty of disease available.

As in previous studies, the researchers found that 25 C was optimal for clubroot development, and even at the high pH level of

8, the plants still suffered a 40 to 50 per cent infection rate. The canola plants grown in the same pH soil, but at 20 C, received a 20 to 30 per cent incidence of clubroot.

“These results demonstrate that while raising the pH helps, it will never get you zero infections, if other conditions favour disease development,” she says.

Overall, researchers found that raising the pH, with cool air temperatures of 10 to 15 C, helped lessen the incidence of injury. Cool soils, however, were ideal in delaying the onset of clubroot, so if possible plant the crop early, says Dr. McDonald.

Of the clubroot fungicide trials, Dr. McDonald says the bio-fungicides worked best in 2009 but not so well in 2010.

“The results have been variable and nothing is really consistent,” she says. “That might be because we needed higher rates or more water.”

More fungicide research needs to be done.

As for varieties resistant to clubroot, Guelph researchers have been appraising four resistant cabbage cultivars from Syngenta. Other resistant varieties available include bok choy, Brussels sprouts and broccoli.

The standard varieties are highly susceptible to clubroot but resistant strains are on the market and they perform well. Tolerance in 2011 fell for the resistant broccoli hybrids planted in the same field two years in a row. It displayed some clubroot but it still yielded four times more than the susceptible variety

in the check plot.

The resistance bred into the new plant varieties is most impressive but will it stand the test of time? “In Europe, they have a resistant line of canola but over the years they have seen this broken down,” says Dr. McDonald.

Each year, a number of resistant cultivars developed from seed companies become available.

“I know the seed prices are expensive,” she says. “If you don’t have a clubroot problem and traditionally have little disease pressure, then there is no advantage. But if you do, the new resistant varieties are well worth the cost.”

The bottom line is to maintain good management practices and use fungicides wisely and effectively regardless of what you plant. As well, go back to the original recommendations of planting in well-drained fields, and increase your pH to 7.2 or higher as it will reduce your disease pressure. For brassicas such as bok choy, try to plant early in cool soil. For all crops, always use a long-term rotation, even with the resistant varieties that should be rotated wisely.

In the future, Dr. McDonald says researchers are looking at the resistant cultivars as well as the mechanisms of resistance to determine what genes are involved and which ones can be identified. The results from the 2011 research is available on the OMAFRA website.

For more information, visit www.plant. uoguelph.ca/index.html.

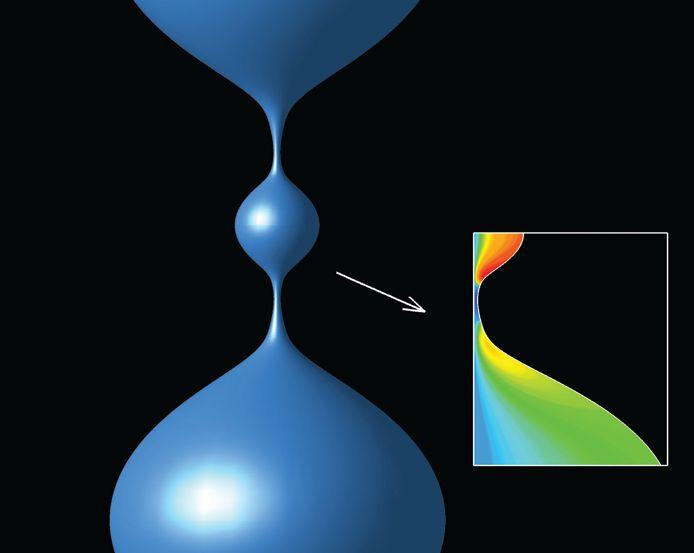

Chemical additives that help agricultural pesticides adhere to their targets during spraying can lead to formation of smaller “satellite” droplets that cause those pesticides to drift into unwanted areas, Purdue University researchers have found.

Carlos Corvalan, an associate professor of food science, said understanding how the additives work together means they could be designed to decrease the health, environmental and property damage risks caused by drift. Corvalan; Osvaldo Campanella, a Purdue professor of agricultural and biological engineering; and Paul E. Sojka, a Purdue professor of mechanical engineering, published their results in a February issue of the journal Chemical Engineering Science.

“When we spray liquids, we have what we call main drops, which are drops of the desired size, and we can also have smaller satellite drops. The smaller drops move easily by wind and travel long distances,” Corvalan said. “Now that we know better how additives influence the formation of satellite droplets, we can control their formation.”

When liquids are sprayed, they start in a stream and eventually form drops. As the liquids move farther in the air, drops connected by a thin filament start to pull apart. That filament eventually detaches and becomes part of the drops that were forming on either side of it. Satellite droplets form in the middle of filaments of pesticides containing

Mr. Blair Bossuyt, Eastern Canada Sales Manager, Nufarm Agriculture Inc. is pleased to announce Mr. Remy Lyczko has joined Nufarm in the new position of Technical Specialist – Horticulture. Remy, will be the lead contact for technical information on all of Nufarm’s growing Specialty and Horticultural Product Line in Canada.

Remy brings a wealth of experience to Nufarm with his recent work as a Field Research Specialist and Principal Investigator at Vaughn Agricultural Research Services, in Branchton, Ontario. In this position Remy, has gained immeasurable experience in all horticulture crop research and the upkeep of several types of orchard crops. Remy is a graduate of the University of Guelph with a Bachelor of Science in Agriculture, majoring in Agroecosystem Management.

Remy looks forward to visiting Nufarm retailers and customers in discussing and servicing your 2012 requirements.

cell: 226-820-6223

email: remy.lyczko@ca.nufarm.com

By Brian Wallheimer

surfactants and polymeric additives, which help the pesticides wet and adhere to plant surfaces. The surfactants reduce surface tension and force round drops to flatten, helping them cover more surface area on a sprayed plant’s leaves. The polymeric additives reduce viscosity – liquid resistance – making the pesticide flow easier. Polymeric additives also keep the drops from bouncing off plant surfaces.

“Each additive is designed to improve the characteristics of the main drops,” Corvalan said. “But there is a side effect.”

When both additives are present in a pesticide, the surfactant pushes more liquid toward the filament. The reduced viscosity allows liquid to flow more

easily in that direction, resulting in a well-defined satellite drop forming in the filament.

“When you put both additives together, there is a synergistic effect. The force induced by the surfactant that was opposed by viscosity is no longer so strongly opposed, and this combined effect can result in the formation of satellite droplets,” Corvalan said.

Drifting of agricultural pesticides not only increases waste and cost for farmers but also can cause health, environmental and property damage, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The results show that carefully modulating the strength, concentration or ratio of surfactants to polymer additives can mitigate or eliminate the formation of unwanted satellite droplets.

Corvalan is now transferring the results obtained from agricultural research into food processing and rocket propulsion work. He said drop size uniformity is as important for fuels sprayed into rocket combustion chambers as for the production of food emulsions.

By Hugh McElhone

Despite their reputation, the vast majority of nematodes are not only considered beneficial but also as organisms vital for maintaining soil and plant health, says Becky Hughes, University of Guelph, New Liskeard, Ont. The microscopic worm-like organism has thousands of classifications but a few hundred species are considered plant parasites.

“When you think of a nematode you tend to think of the ones that live in the soil such as the root knot and root lesion nematode. The one of concern for garlic growers is the bulb and stem nematode that also eats leaves and lives within the bulb,” she said. The persistent pest, identified as Ditylenchus dispsaci, was identified in California in the 1960s and in Ontario some 10 years ago. This pest threat was initially thought limited but it has caused significant damage in recent years and some growers have lost whole crops. Intensive research into how widespread this pest is in Ontario began about two years ago. This particular nematode lives in the plant and feeds on the leaves, stem and bulb so it can be easily spread with the seed or any other part of the garlic plant or dried plant debris. It can also survive for years in the dried trash stuck to dirty tractors, equipment and storage boxes. When access to soil is available, the pest can return to the soil and live for many years without a host. Heavy clay soils give it greater longevity compared to sandy loam. There are also a number of strains or races of this pest. Looking at the signs and symptoms, Hughes

says it causes stunting and yellowing plants that die prematurely throughout the season. If the plant was infested at planting time, it will likely appear as a dwarf with a thick distorted stem and small leaves. The bulbs can be without symptoms, however, the root plate can rot separating the bulb from the root system. This condition causes the bulb to rot, and the advent of secondary infections such as fusarium, hampers pest identification. Plants with this condition are easily identified by their yellowed, dwarf appearance and when pulled, easily break off from the base

Looking at the life cycle, Hughes says the pest actually burrows from the leaf down to the bulb and root plate where it develops and feeds. As the bulb rots and the pest reproduces, juvenile nematode offspring move into the soil and swim to a new place to live. These juveniles swim well not only in wet soils but also in the film of water on plant tissue and the soil surface. “It really only takes one infected plant to infest a field,” she said

“To make things complicated, bulb and stem nematode has a wide range of hosts. It will grow in corn, bean, rye, onion, peas, corn and strawberry crops. It also has a range of 300 to 500 species. To complicate things more there are about 30 known races

ABOVE: An example of a field infected with bulb and stem nematode. The infected plants turn yellow, then brown, then shrivel up and die.

and likely more that attack a specific host or specific group of hosts. We have found that the race that attacks onion and garlic tends to stick to the onion family and does not attack field crops like canola or alfalfa. And there is one race that attacks garlic and strawberries that is totally unrelated. We still don’t know all of the races that are out there,” she said

In 2010, working with the Garlic Growers Association of Ontario (GGAO), they created a study to track the extent of infestation across the province and to identify the prominent races. Nothing similar has been done since 196

In this study, researchers collected 10 garlic bulbs from growers across Ontario. Growers in turn, completed a questionnaire on seed sourcing and cropping practices.

“When we started collecting samples some of the garlic looked too nice but that changed later in the season,” she noted

Infected bulbs were sent to the lab to identify the race of nematode. In a misting chamber, the nematodes will actually crawl out of a dug garlic bulb after about 24 hours, and the technicians can then identify and count their numbers in solution, she said

From their survey results, the research team collected 123 samples from 79 farms in 33 counties. Of these samples, 59 per cent were of the Music variety, and 73 per cent of all the samples had bulb and stem nematode

Of note, Hughes said there tended to be a higher infestation rate in south-central Ontario where the highest number of samples were collected. She also noted that 18 per cent of the Music variety had no nematode infection.

“They were clean,” she said.

From their recommendations, “a good crop starts with clean

seed, and it’s a good idea to get a sample of your seed tested by the University of Guelph before you plant it,” she said. For cleaner fields, Hughes said Cutlass oriental mustard does a good job of nematode suppression. She also suggested a minimum four-year crop rotation with no Allium crops until the race of the nematode can be identified. “We suspect it’s all the same race of bulb and stem nematode but we’re not sure at this time,” she said. Keep infested seed separate from clean seed both in the field and in the storage area, and always plant the clean seed on the higher ground. Thoroughly clean and disinfect your equipment and the storage area when finished. Some growers might consider using the hot-water seed treatment. Hughes said she is no expert in this treatment so could make no recommendations, however, directions are available on the Internet and some careful growers have had good success. “The bottom line for all growers in the industry is to always consider growing clean seed,” she said. Hughes said the basics for the virus-free seed being developed in their laboratory starts at micro-propagation with clones established in culture by tissue or bulbils. These are tested for pathogens, and if clean, plantlets are established and multiplied

For stock plant maintenance, the clones of these stock plants are grown during the winter in the greenhouse. For production, plantlets are planted in a screened greenhouse and single clove bulbs are harvested in August, she said

Based on the results of their garlic study with the growers, and their laboratory work to test the efficacy of virus-free seed, Hughes says they hope to assist growers in the management of their crops with the proper identification of the problem.

Electronic nose knows when cantaloupe is ripe

Have you ever been disappointed by a cantaloupe? Too ripe? Not ripe enough? Luckily, researchers from the University of California, Davis, might have found a way to make imperfectly ripe fruit a thing of the past. The method will be published on March 30 in the Journal of Visualized Experiments (JoVE).

“We are involved in a project geared towards developing rapid methods to evaluate ripeness and flavour of fruits,” said paperauthor Dr. Florence Negre-Zakharov. “We evaluated an electronic nose to see if it can differentiate maturity of fruit, specifically melons. The goal is to develop a tool that can be used post-harvest to better evaluate produce, and develop better breeds.”

When fruit ripens, it develops a characteristic volatile blend, indicating its maturity. Traditionally, the gold-standard of evaluating these volatiles has been gas chromatography, but it takes up to an hour to analyze a single sample, which makes it impractical to use outside the lab. Dr. Negre-Zakharov and her team wanted to determine if the much cruder – but much faster – electronic nose would be able to determine if the melon they used in the experiment was ripe. It was.

“It’s quite encouraging technology for the purposes of determining maturity,” she said.

The project is part of the Specialty Crops Research Initiative, funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which was “established to solve critical industry issues through research and extension activities.”

Dr. Negre-Zakharov and her team are working on quantitative methods of evaluating fruit ripeness in the hopes that it will help the industry produce better-quality produce.

“It’s very impressive that the electronic nose system can do a type of gas chromatography in about a minute. Also, the sample preparation is as easy as making a smoothie at home. Such a user-friendly system could greatly help analysis efficiency in this field,” said JoVE science editor, Dr. Zhao Chen.

The next step is to take the electronic nose out into the field to determine if it can still ascertain fruit maturity with all of the background smells interfering – like soil and air quality. Though the team has already tested the device in the field, they have not yet analyzed the results.

Because the very nature of the project is

to give people useful tools, the researchers decided to publish in JoVE, the only peerreviewed science journal to publish all of its content in both text and video format.

“We thought that the best way to get people to adopt the method was showing a video, instead of publishing a text,” said Dr. Negre-Zakharov.

To watch the full video article, click here: http://www.jove.com/video/3821/fruitvolatile-analysis-using-an-electronic-nose.

The P.E.I. Potato Quality Institute (PQI) has expanded its facility in the West Royalty Industrial Park to offer local potato farmers more efficient disease testing, thanks to investments made by the federal and provincial governments, and industry partners.

This new expansion will allow for the addition of a potato disease testing facility and improve efficiencies for Island potato farmers.

The Government of Canada, through the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency, has invested $190,833 to help with the purchase of new equipment for the facility. The Government of Prince Edward Island, through the Department of Agriculture and Forestry, the PQI and the P.E.I. Potato Board, has also contributed a combined investment of $381,667 to assist with required building renovations to facilitate the new testing procedures.

It’s hoped the investment will allow the P.E.I. Potato Quality Institute to offer improved services to farmers, helping small and medium-sized businesses to continue to create jobs and economic prosperity, said government representatives. It’s also hoped lab improvements will assist with ensuring healthy potato seed stocks for growers and allow the industry to be more competitive in global seed markets.

“We welcome this collaboration with both levels of government that will help our industry move forward with the most recent advances in testing technology,” said Gary Linkletter, chair of the P.E.I. Potato Board. “This will facilitate our participation in export markets and improve our testing procedures used to maintain crop health. We appreciate the government investment at the

P.E.I. Potato Quality Institute and are pleased that they recognize the contribution that our industry makes to the provincial economy.”

British Columbia cranberry producers are benefiting from a $218,500 investment in research to test new cranberry varieties and provide growers the information they need to increase their productivity and profitability.

The investment will help the B.C. Cranberry Marketing Commission (BCCMC) select the most promising new cranberry varieties for B.C. conditions, and determine the best growing mediums and horticultural practices for each new, higher-yielding cranberry variety. Much of this research will be conducted at the newly established Cranberry Research Centre in Delta, B.C.

“Cranberry farmers deeply appreciate this support and the recognition of the importance of our facility,” said Todd May, commissioner of the BCCMC. “This acknowledgment further reinforces the dedication and financial commitment of our farming families toward the future of the cranberry industry in British Columbia.”

The BCCMC has been a part of the province’s cranberry farming since 1965. The commission regulates the transportation, processing, packing, storage and marketing of cranberries grown in B.C. It also supports the industry by providing production research, grower education, and promotional activities for domestic and foreign markets.

In work that could cut back on insecticide use, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) scientists have found a way to distinguish aphids that spread plant viruses from those that do not.

The researchers used protein biomarkers to differentiate between virus-spreading and virus-free aphids. The findings mark the first time that protein biomarkers have been linked to an insect’s ability to transmit viruses.

Agricultural Research Service (ARS) scientists Michelle Cilia and Stewart Gray have found they can identify disease-carrying aphids by examining the types of proteins in their cells.

The researchers knew from previous

work that for aphids to pick up and transmit viruses, the virus must be able to interact with specific aphid proteins that direct movement of the virus through the insect and back into a plant during feeding. By studying greenbug aphids in the laboratory, they discovered that the lab-raised insects’ ability to transmit yellow dwarf viruses was linked to the presence or absence of nine biomarker proteins found in the insect cells.

They then analyzed greenbug aphids collected from cereal crops and non-cultivated fields and found the aphids consistently transmitted yellow dwarf virus only when they carried most, if not all, of the nine proteins. Field samples were collected by ARS colleagues John Burd and Melissa Burrows. The aphid does not need all nine proteins to spread the virus, but there are some that are essential.

The discovery in the lab was published in the Journal of Virology, and the field population study was reported in Proteomics. The findings are expected to lead to development of a test to identify potential disease vectors. Cilia and Gray also are collaborating on an expanded effort to test whether biomarker-predictor proteins can be found in other insects.

The Prince Edward Island Potato Board is making a hot potato cool. In an effort to raise awareness of the health benefits of the vegetable, showcase recipes and boost consumption of the potato, the P.E.I. Potato Board has launched a marketing campaign anchored by P.E.I. native and Olympic bobsleigh gold medallist Heather Moyse.

Marketing initiatives, which are now in store and online, feature

branded bag packaging – complete with tear-away recipe cards, and nutritional information; cooking video vignettes with Heather Moyse and a local chef; as well as promotional speaking engagements with Heather Moyse.

Heather Moyse was at the Canadian Produce Marketing Association Trade Show held in Calgary, Alta., in mid-April, unveiling the new bag packaging, as well as speaking about her journey as a brand ambassador and Canadian athlete. In addition to winning her bobsleigh gold medal at the Vancouver 2010 Games, Heather has represented Canada in rugby and cycling competitions.

“The combined efforts of our new marketing campaign are designed to entice and educate the consumer on the benefits of the potato,” said Greg Donald, general manager of the P.E.I. Potato Board. “As we move into the spring and summer seasons, there is no better time than the present to remind Canadians of Prince Edward Island potatoes.

“Engaging Heather Moyse as an ambassador for our brand was an obvious choice. In addition to her Islander status, Heather’s achievements demonstrate how a healthy balanced diet that includes potatoes can contribute to optimal physical strength and endurance.”

As a means to further educate the public about potatoes, the P.E.I. Potato Board features a website geared to consumer interaction, complete with teacher resource guides.

Prince Edward Island is Canada’s largest producer of potatoes, with approximately 330 growers in the province. While 44 per cent of the Island’s crop stays in Canada for consumption, 35 per cent is shipped to the U.S., and 21 per cent goes out to 28 other countries around the world.

New Holland recently released three new narrow row tractors for use in rows of vineyards, orchards, and nut groves.

TheTD4040F (76 PTO hp) and T4060F (92 PTO hp) and the super-narrow T4060V (92 PTO hp) models combine power and manoeuvrability with the narrow width and low height needed to work under vineyard and tree canopies and in close quarters.

The TD4040F features an open platform and foldable mid-roll bar, a 195 cu. in. fourcylinder engine, 4WD front axle and choice of a 12x12 or 20x12 (creeper) SynchroShuttle mechanical transmission. The open operator platform is suspended on isolation mounts for low vibration and offers controls that are easy to identify and use.

The T4060F (92 PTO hp) and supernarrow T4060V (92 PTO hp) are available with or without a cab, and feature more transmission choices, including a 16x16 transmission with mechanical or power shuttle or the 32x16 Dual Command transmission with power shuttle and park lock. On cab units, two electro-hydraulic midmount valves with 10 couplers control up to five functions, accommodating the needs of a wide range of mid-mount and front-mount implements used on specialty tractors.

The T4060F is the only narrow tractor on the market to offer New Holland’s SuperSteer FWD axle for short FWD row-torow turning.

The factory-installed New Holland Blue Cab, standard on T4000V and T4000F Series tractors, offers climate control. A filtration package features anti-pollen filters for

external and recirculated cab air, and a cab pressurization fan as standard equipment. Anti-pollen filters in the cab roof block particles down to 0.3 microns in size. Filters are included in the internal recirculation vents as well, helping to remove foreign particles introduced when doors and windows are opened. The Blue Cab maintains higher cab pressurization and draws in 20 per cent more outside air.

www.newholland.com

New liquid potato seed-piece treatment launched

Bayer CropScience is introducing Titan Emesto, a liquid insecticide and fungicide potato seed-piece treatment for protection against major insects and diseases.

Titan Emesto features a coloured formulation to ensure growers can uniformly and safely apply it to potato seed-pieces to maximize pest control and yield potential. The product provides fusarium protection, seed-borne rhizoctonia control, activity on silver scurf and insect control.

“Titan Emesto is a co-pak of Titan, the broadest spectrum potato seed-piece insecticide, and Emesto Silver, a new potato seed-piece fungicide with two new modes of action protecting against major diseases,” says David Kikkert, portfolio manager for horticulture with Bayer CropScience. “Growers will benefit from the outstanding protection provided by Titan Emesto against fusarium tuber rot including current resistant strains, seed-borne rhizoctonia, silver scurf, Colorado potato beetle, leafhopper, aphids and flea beetle, and reduces the damage caused by wireworms.”

Key benefits include:

New coloured formulation that facilitates safe and uniform application

New fungicide chemistries for potato seed-piece treatment. Two new modes of action contributing to the fight against disease resistance.

Fusarium tuber rot control (including current resistant strains)

Control of seed-borne rhizoctonia (black scurf, stem and stolon canker)

Activity on silver scurf ( Helminthosporium spp. )

Insect control

Low dose rate

“To achieve optimal disease and insect control, growers must ensure good uniform coverage of the potato seedpiece,” says Andrew Dornan, field development Rep for Eastern Canada with Bayer CropScience. “Our coloured formulation is a unique feature making it easy for growers to see and experience the difference Titan Emesto makes.” www.BayerCropScience.ca

Encompassing: Row crops, orchard, vineyard, greenhouse, floral and tobacco sectors.

The following businesses feel you’d benefit by attending the Tech X-Change so they’re paying $5.00 of your admission fee. Simply clip a coupon and come and see us in St. Williams in July.

1195 Front Rd., St. Williams, Norfolk County, Ontario

According to a new Farm Credit Canada (FCC) Farmland Values Report, the average value of farmland in Ontario increased by 7.2 per cent during the second half of 2011. In the two previous six-month reporting periods, farmland values increased by 6.6 per cent and 2.4 per cent, respectively. Farmland values have been rising in Ontario since 1993 and reached a peak increase of 8.2 per cent in the last half of 1996. The FCC report provides important information about changes in land values across Canada and is available at www.farmlandvalues.ca.

In comparison, the average value of Canadian farmland increased by 6.9 per cent during the last six months of 2011, following gains of 7.4 per cent and 2.1 per cent in the previous two semi-annual reporting periods. Overall, farmland values increased in nine provinces and remained unchanged in Newfoundland and Labrador. Saskatchewan, which has 40 per cent of Canada’s arable land, experienced the highest average increase at 10.1 per cent. Saskatchewan results appear to be in line with the pace of price increases in the U.S. where double-digit growth in farmland values have been reported in several corn and soybean states including Iowa, Kansas and Nebraska. Two contributing factors to the value increase in Saskatchewan are the current and anticipated strength of commodity prices, combined with land values that previously increased at a slower rate than in other areas of the country.

“Low interest rates, in relation to inflation, and higher farm income levels have recently led to significant increases in farmland values in some provinces,” says Michael Hoffort, FCC senior vice-president of portfolio and credit risk. “FCC’s analysis indicates that farmland value trends are sensitive to both interest rates and crop receipt trends. With interest rates expected to remain at historic lows until 2013, it will be especially important

Farmland values across Canada increased in nine provinces and remained unchanged in Newfoundland and Labrador. Saskatchewan, which has 40 per cent of Canada’s arable land, experienced the highest average increase at 10.1 per cent.

to monitor trends in crop and livestock receipts in the coming year. These factors combined with strong demand from expanding farm operations and increasing interest by non-traditional investors have all played a role in the continuing trends toward higher farmland prices.”

Canadian farmland values have risen steadily during the last decade. The highest semi-annual average national increase was 7.7 per cent in 2008. The last time the average value decreased was by 0.6 per cent in 2000. The average national price of farmland has increased by about 8 per cent annually since the general upswing in commodity prices began in 2006. That’s about twice the rate observed in the first part of the decade.

Recent long-term projections from Agriculture and AgriFood Canada provide a positive outlook for Canadian agricultural producers.

“A more affluent population in emerging economies like China and India is driving the global demand for food which results in crop and livestock prices that have remained above historical averages,” says Jean-Philippe Gervais, FCC senior agriculture economist. “This helped propel the value of farmland to record-highs in North America. It will be important for producers who want to sell or buy farmland to keep an eye on possible variations in Canadian farm income in the coming years.”

The FCC Farmland Values Report has been published since 1984. To view previous reports, visit www.farmlandvalues.ca.

Higher performance and expertise. THE PERFECT FIT FOR YOUR HORTICULTURAL BUSINESS.

More and more, fruit and vegetable growers are discovering the advantages of high-performance horticulture products from Dow AgroSciences. Our products and expertise will help you control pests and improve profit. Get exceptional insect control with DelegateTM – registered in potatoes. Control powdery mildew with QuintecTM Protect your produce with DithaneTM DG RainshieldTM NT, the world’s most trusted protectant fungicide. Grow your high performance business with horticulture products from Dow AgroSciences. Accomplish more. Call 1.800.667.3852 or visit www.dowagro.ca.