AMY BENNETT

GIMME SHELTER

Robert Long ForemanEvery one of Amy Bennett’s paintings tells a story. Every panel that bears her mark is alive with more even than it first announces, as a certain strength animates her work, a force that is as elusive as it is powerful.

To describe that force, to put words to what we see in her work, can be tricky. To attempt it risks missing the point—because when we regard one of Bennett’s paintings there is no real need for us to elaborate on what we see there. She presents us with whole narratives, told through isolated moments. Everything we might want to know is there before our eyes.

In Island, a family is gathered at their kitchen table. We register tension in the way the father leans back on his elbow, how the daughter hunches in her chair. The mother tilts forward intently. The walls are almost bare. The cold colors of the top-right align with the parents; daughter and son blend with the warmth of everything else. The son sits halfway off his chair, as if prepared to sprint from the room.

We recognize this room. We know these people.

We could say more. We could imagine the scene as it plays out from that moment, and extrapolate the architecture of a narrative—words spoken, faces made, voices raised. But to do so would be redundant. It would feel false, for the whole story is immanent in this arrangement of bodies in space.

With their economy and scope, and with their laser focus on mere moments in the lives of their characters, Bennett’s paintings function much the way short stories do. Of all the literary genres, it is the one her work has the most affinity with, as it operates within the most similar constraints.

A short story must be brief, zeroing in on just a few moments in time, and charting a course between them to give an impression of vastness. A character’s whole life is understood by way of a handful of scenes, much the way in each of her paintings Bennett portrays one moment, one scene, accessing a great volume of feeling, and staggering depth, while operating within even stricter limits. Here there is no passage of time, no beginning, middle, and end. There is only the constant present of the painting.

In The Lonely Voice, his book-length study of the short story, Frank O’Connor explains that a story’s writer seeks to represent the entirety of a life in a handful of pages, often a mere few thousand words. The writer must select, with exact precision, the fragments of a character’s experience they will gather, to give the reader all they need to understand this fictive person. “But,” he writes, “since a whole lifetime must be crowded into a few minutes, those few minutes must be carefully chosen indeed and lit by an unearthly glow.”

In the presence of Bennett’s work, we feel the warmth of that glow. Her paintings are vehicles for powerful stories, told in the instant one meets a viewer’s eye.

But we might call what we see in Bennett’s scenes not stories but situations, or predicaments. For while every painting engages with narrative, it also stands back from it. It implies a story. It gives us evidence of one. It shows us clues that we observers use to forge a coherent whole, to extrapolate the lives of those depicted there.

Girls walk through a campsite, in Cool Kids, some hand-in-hand. The scene is placid, if not idyllic, and despite how it is populated with human figures it is not without a sense of loneliness. RVs and

sedans crowd the natural world these people have surely gone there to bask in. They move with the comradely leisure of vacationers, but they are flanked on both sides by the vehicular debris of modernity. Maybe they are headed for the woods, but on the path ahead all we see are more cars. Perhaps that is all they will find. Perhaps the kids will not escape what they have gone there to leave behind—including the strains put on the bonds that hold them together.

The figures in Bennett’s paintings live with the same modern tensions and contradictions that we, the living, do. We want to be in nature, but we reach it in a car. We long for company, but we want to be alone. We dwell in neighborhoods but pack ourselves into houses and apartments, venturing out only when we must.

We are the family in Bunker, who have retreated into a bomb shelter. It is cold in there, and grey—and yet it is cozy somehow. The father, mother, son, and daughter find warmth in dire circumstances, closeness in a crisis. We see it in the girl’s acute posture, in the way mother and son huddle near one another. In their bodies and the spaces between them we see and feel the unearthly glow.

Persistent in Bennett’s work is the suggestion of crisis, whether it is an existential threat that has forced a family to safety underground, or the sort of everyday calamity that’s suggested by the resigned posture of the mother in Snacks, who leans back against a shelf in apparent exhaustion. The light that streams into the scene warms it, while also telling us this woman’s hard day of childrearing is far from over.

Contact between people is never neutral in these paintings. It is always freighted with meaning, danger, and great possibility. Between the tensely arranged people in Booking, and the drifting bodies in Sink or Swim, magnetic fields vibrate. Even the glimpses we get of people in isolation have a gravity that tugs at us.

The world of Bennett’s paintings is one that has not fallen from grace so much as it has just begun to fall. The source of her work’s tremendous power, the heart that keeps its blood pumping, that gives it life, is the way the figures in her work are always carrying on with their lives despite everything.

The substance of that “everything” changes from panel to panel, and the paintings in Shelter are, like the best short stories, not without ambiguity. In Year Long Day, we see a house in the middle distance, one of its walls made transparent. Revealed inside are a woman and a child. The kid is eating breakfast, cereal box on the table. The woman faces the opposite direction, hunched forward. Does she lean from exhaustion, or is she absorbed in what’s on the screen? Is the child digging into the food or having a crying fit? Does the woman wish to be anywhere but there, or is this what domestic bliss looks like? We know what we see there matters, for it is made conspicuous by the absence of the external wall. The blue of the television dominates the scene, a magnet for our eyes, like an anchor that has been dropped there from another world.

But if every one of these paintings is like a short story, then what moment in the story does each one portray? When, in the course of its narrative, does the image take place?

Much has been written about the trajectory of a short story, its movement from rising action to climax to falling action. The climax is often marked by a turning point. The protagonist comes to a realization, makes a fateful decision, or finds they have changed thanks to forces out of their control.

Bennett’s scenes do not depict these epiphanic bursts of revelation. She locates us at another point in time, when trouble is still on its way, when pieces are being put in place before the match begins. The tension is not yet on the table; the threat has not announced itself. We are there in the uncertainty of the moment that comes before the moment of crisis, when no one—except for us, looking on—knows if the road ahead will be smooth or perilous.

It will be perilous. Trouble will find these people. The gathering in Dinner Guests will be a tense one. The indications are there: see the man who sits rigid with his back to the arriving guests, in contrast with not only the one who greets the newcomers, but the dog who stands by the table, eager to be fed the scraps he is owed.

We know, because we are looking at them, that something will happen to all of the people in Bennett’s paintings. And the paintings entice us to identify with those who appear in them. Her work invites our empathy, because for all we know we are in much the same predicament as the one we see contained in the frames.

We can be certain, in fact, that we are with them in the thick of things. Indeed, it seems that Bennett has always been painting the world we find ourselves in now, with crises looming on the horizon and others at our backs. She does her work with an understanding that for all of us a challenge, if not great peril, awaits us around the next corner. She shows us these people with their ever-present troubles. Through them she allows us to catch glimpses of ourselves.

Basking, 2023

Oil on panel

15 3/4 x 19 3/4 inches

40 x 50.2 cm

Bite Your Tongue, 2023 Oil on panel

9 x 11 inches

22.9 x 27.9 cm

Bunker, 2023

Oil on panel

3 1/2 x 3 1/2 inches

8.9 x 8.9 cm

Couples, 2023

Oil on panel

7 x 9 inches

17.8 x 22.9 cm

Cravings, 2023

Oil on panel

4 x 7 inches

10.2 x 17.8 cm

Flashes, 2023

Oil on panel

3 3/4 x 7 1/2 inches

9.5 x 19.1 cm

Island, 2023

Oil on panel

5 x 9 inches

12.7 x 22.9 cm

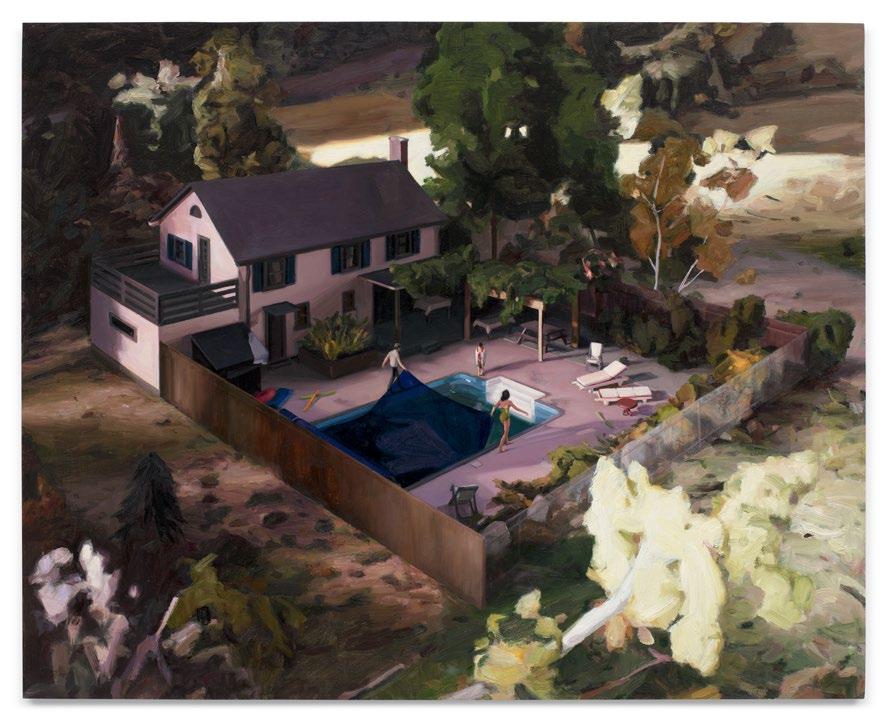

Pool Blanket, 2023

Oil on panel

15 3/4 x 19 3/4 inches

40 x 50.2 cm

Sink or Swim, 2023

Oil on panel

4 x 5 inches

10.2 x 12.7 cm

Snacks, 2023

Oil on panel

3 1/2 x 3 1/2 inches

8.9 x 8.9 cm

Year Long Day, 2023

Oil on panel

23 3/4 x 29 3/4 inches

60.3 x 75.6 cm

Beached, 2024

Oil on panel

10 3/4 x 13 inches

27.3 x 33 cm

Booking, 2024

Oil on panel

3 x 6 inches

7.6 x 15.2 cm

Cool Kids, 2024

Oil on panel

11 x 13 3/4 inches

27.9 x 34.9 cm

Dinner Guests, 2024

Oil on panel

8 x 10 1/8 inches

20.3 x 25.7 cm

AMY BENNETT: HOW WONDROUS TO WATCH OURSELVES

Elizabeth BuhePropping up her head with her hand, Wilhelmina felt the compacted earth under her blanket press back against her bare arm. She barely noticed the stomp stomp of hikers passing by. They were the Cool Kids. Not Wilhelmina, separated by the merciful presence of a burly little bush. Despite her black one-piece, she wasn’t sunbathing. She was reading. Campers should unplug, relax. Engage in something analog. So, she did. She even forgot about her own kids. Let someone else watch them for once. If they stayed away, maybe she could even finish the chapter. Theirs was the small trailer, anyway. No room for a crowd. The creeping advance of the shade didn’t even bother her.

The scene stops here. Cool Kids is a painting, not a story. It presents a snapshot rather than a narrative unfolding over time. Our eyes move through the painting, noticing the station wagon’s crooked parking job; the impossibly smooth blue tarp pinned below a wooden table; or that the touch of one girl’s outstretched hand goes unreciprocated by another, who recoils a bit. All of these things happen simultaneously. Then, our imaginations take over. The provocation of the painting’s plot tension begs us to think temporally: What happened just before? What will happen next? How many times has this scene, or a similar one, played out? How many times will it in the future? Are scenes like this actually happening everywhere all the time?

In her exhibition, titled “Shelter,” Amy Bennett presents outdoor scenes of summertime leisure and straight-on views into a single room, all pregnant with narrative tension. They are familiar, homey, comfortable. They are also deeply weird. In Bite Your Tongue, a sister camping scene to Cool Kids, a reclining woman does not actually lie on her folding lounge chair but levitates above it,

her ponytail pulled downward by gravity. Almost always, someone’s back is turned toward us. Elsewhere, as in House Guests or Couples, people pass through doors, caught at that threshold between inside and out. It is as if these figures allegorize the shifts that Bennett’s works stage (effortlessly, it seems, but this too is a deceit) between spaces and conceptual realms: between the presence and absence of historical memory, between first and third person, between nostalgia and critique. All of these entail a shift of perspective that we, as viewers, clock as a twist in the gut.

It is well known that Bennett makes her paintings from intricate three-dimensional models of miniature scenes that she constructs in her studio. Doing this materializes the intangible memories or moods that inform a scene’s contours and provides a distancing effect that, Bennett has said, keeps her at arm’s length from the scene’s intimacies. She sometimes photographs the model to test out different spatial positions and the views these open up, but for the most part she does not paint from the photographs. She occasionally refers to them, however, to render a

scene’s light consistently. One reason Bennett’s working method is important is that it shows her paintings to be built on a mediated idea of reality—the model—that she has made herself, rather than accepting, uncritically, images that circulate in our popular image economy.

Likewise, any memories the paintings seem to disclose are not direct transcriptions of Bennett’s experiences, but fictional composites. The paintings indicate this intermediary level of artifice. Their distribution of light, for instance, is unnatural. Scenes are spot lit in an area of particular narrative significance, while framing trees or furniture remain in relative darkness.

There is an art historical precedent for recognizing the constructed nature of reality and the way images circulate around us like a tissue of quotations referring to yet other texts and images. It comes, of course, from the Pictures Generation of the 1970s. These artists, by re-presenting images that already existed—Sherrie Levine of Walker Evans’s sharecropper, Richard Prince of the Marlboro Man—shifted our approach to viewing and interpreting images away from seeking a “truth” behind the image. Thus, the old-timey bakery of Bennett’s Cravings is not a nostalgic throwback to a bygone America but a quip about prepackaged notions of desire. While Bennett’s three-dimensional constructed models make the Pictures Generation precedent explicit (even as she uses paint rather than a reproducible medium such as photography), in my view the mediated nature of our daily activities and their representation have always been a fundamental component of her practice. All of this was widely assimilated before Bennett began painting: The critic Douglas Crimp and the gallerist Helene Winer’s exhibition “Pictures,” the breakout show for the Pictures Generation artists, took place in 1977, the year of Bennett’s birth.

Thus, Bennett’s works are not just technically brilliant repositories of painted form; they are texts that query the circulation and sedimentation of images, or perhaps memories, and how these come to snag us. In his essay for the “Pictures” show, Crimp called out the retreat of first-person

perspective against the onslaught of media saturation, which has arguably become all the more intense in our current era of social media. But Bennett’s answer to what replaces first-person experience would seem to be different from what Crimp saw as the inescapable mediation of pictures. Bennett’s painting suggests more than one point of view. More specifically, it points to that moment of recognition when two points of view, first person and third person, reverse or slip. For what seems to be at the core of Bennett’s art is not commercial imagery but the highly subjective content of memory—its blunted corners, fuzzy edges, shortfalls, and permutations— situated at that margin between what is particular to her and what we all share. The oscillation between first and third person is what happens in the process of discovery when we look at Bennett’s paintings, and is a technique she draws from a different medium, still: the short story.

In our conversation, Bennett mentioned that she had been reading Lucia Berlin, a writer known for her wry humor and the extreme economy with which she evoked banal or grim situations. Berlin is a virtuoso at twisting her story at just the right moment, flipping the narrator’s voice to divulge a different point of view. Indeed, one story is aptly called “Point of View.” In it, Berlin avers that no one wants to hear the compulsive details of a woman’s trip to the laundromat, preparation of creamed peas, or floral bath. However, “you’ll listen … only because it is written in the third person” … and the narrator will make this person “so believable you can’t help but feel for her.” This is the great power of a shift in perspective, a power with which Bennett imbues her paintings. Trained at the New York Academy of Art, she learned anatomy and perspective by working from live models, so her figures have a sense of life even though they are painted from miniatures. We relate and wonder—about exhaustion, parenting, isolation, the anticipation of catastrophe. It is not just that the paintings invite us to empathize with other people, real or imagined, as much figurative art does. It is that they seem keyed to elicit the shocking shift in worldview that comes when we see things, for the first time, through another’s eyes. After that, nothing, and everything, is the same.

This means there is a humanism in Bennett’s paintings that exceeds the detachment of their underlying postmodernism. The paintings are alert to storytelling, loss, and memory’s mutual presence and absence—what the art historian Michael Ann Holly has called “melancholy” in relation to the discipline of art history. The tug of curiosity we feel at Wilhelmina’s (as I’ve styled her) insistent reading in Cool Kids or at the prone woman sunbathing well into the night in Basking is also the initial moment that I fathom being that woman, feeling what she feels. Western philosophy tells us that the formation of identity requires the presence of another against whom we define ourselves, yet Bennett’s pictures probe the overlaps, rather than the separations, between our experiences that permit such imaginative leaps. That moment when “her” metamorphoses into “I” is an ethical proposition about being that is deep at the heart of Bennett’s painting practice. Looking at the paintings yields any number of responses, among them, to borrow yet again from Berlin, would be “how wonderous to watch ourselves.”

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

AMY BENNETT SHELTER

16 MAY – 3 JULY 2024

Miles McEnery Gallery

525 West 22nd Street New York NY 10011

tel +1 212 445 0051 www.milesmcenery.com

Publication © 2024 Miles McEnery Gallery

All rights reserved

Essay © 2024 Robert Foreman

Essay © 2024 Elizabeth Buhe

Publications and Archival Associate

Julia Schlank, New York, NY

Photography by Dan Bradica, New York, NY

Catalogue layout by Allison Leung

ISBN: 979-8-3507-3038-8

Cover: Year Long Day, (detail), 2023