ESTEBAN VICENTE

ESTEBAN VICENTE

ESTEBAN VICENTE AND THE PASTORAL TRADITION

By Daniel Haxall, Ph.D.

In a 1946 review for The Nation, Clement Greenberg—the influential critic who helped propel Abstract Expressionism to the forefront of Modern Art—wrote: “what characterizes painting in the line Manet to Mondrian...is its pastoral mood.”1 Defining the pastoral rather conventionally, Greenberg described it as “the preoccupation with nature at rest, human beings at leisure, and art in movement.”2 For Greenberg, a “feeling of pastoral security” provided the space and distance required to develop new forms of artistic expression. Critical of “falsely pastoral” art that recycled previous styles and engaged social issues directly, he concluded, “even today one must look still to avant-garde pastoral art to see revealed the most permanent features of our society’s crisis.”3

Historically, the pastoral defined a type of poetry concerned with the activity of shepherds, dating to Theocritus and Virgil in the third to first centuries B.C.E. Considering Greenberg’s predilection for the avant-garde, his evocation of classical literature may seem peculiar, as the virtues of animal husbandry, leisure, and naturalism appear to be at odds with the critic’s penchant for abstraction, pictorial flatness, and artistic purity. However, Greenberg’s formalist conception of avant-garde art parallels many aspects of the literary trope, and he was not alone in relating modern art to the pastoral.

In 2013, for example, the art critic Carter Ratcliff considered the term useful for understanding Esteban Vicente’s oeuvre, particularly as a framework that “transcends the opposition of tragedy and comedy.”4 Ratcliff located familiar attributes of the pastoral within Vicente’s art, notably harmony and beauty, and he positioned this bucolic imaginariness within Vicente’s urban “sophistication.” Accordingly, Ratcliff felt, Vicente rejected the utopianism that compelled the urban pastorals of the early avant-garde, focusing instead on aesthetics and pictorial values.5 This sensibility was pervasive among the New York School, and for artists like Vicente the formal devices and rhetorical strategies of the pastoral corresponded with the attributes that drew him to abstraction.

New York School Retreats

Although the bucolic tradition may seem historically distant from Vicente’s milieu, pastoral imagery regularly appeared through all aspects of the New York School, from literature and theater to visual art. John Ashbery, Frank O’Hara, and James Schuyler employed pastoral tropes in their poetry and developed urban variants of the pastoral through rustic excursions and “nostalgia for a rural past.”6 Pastoral imagery similarly recurred in theatrical performances in New York City during this time, including in Paul Bowles’s Pastorela (performed January 13, 1947) and in The Seasons, with music by John Cage, choreography by Merce Cunningham, and set/costume design by Isamu Noguchi (performed May 18, 1947).

In the decades following World War II, the visual artists of the New York School embodied the pastoral by leaving the city for a simpler, more rural experience. Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner purchased an old farm in East Hampton, Long Island, in 1945. Willem and Elaine de Kooning relocated to East Hampton in 1963 and 1971 respectively. Arshile Gorky frequently visited a farm in Virginia in the 1940s before converting a barn in Connecticut into his studio in 1945. A trip to the Pollock-Krasner residence in Long Island impacted the artistic trajectory of Helen Frankenthaler, and Robert Motherwell lived in East Hampton for eight years (1944–52) before the couple married and began spending summers in Provincetown, Massachusetts. These locations offered a retreat from the urban experience, as well as abundant contact with nature. The artwork produced in response to these environs frequently evoked the pastoral, either directly, as reflected by the titles of paintings by Willem de Kooning and Gorky, or suggestively through mood and allusion, as in Frankenthaler’s Cool Summer (1962). Sensuously executed and brilliantly colored canvases, including Krasner’s The Seasons (1957), attest to the appeal of escapism and the benefits of light, space, and nature while formulating modernist abstractions.7

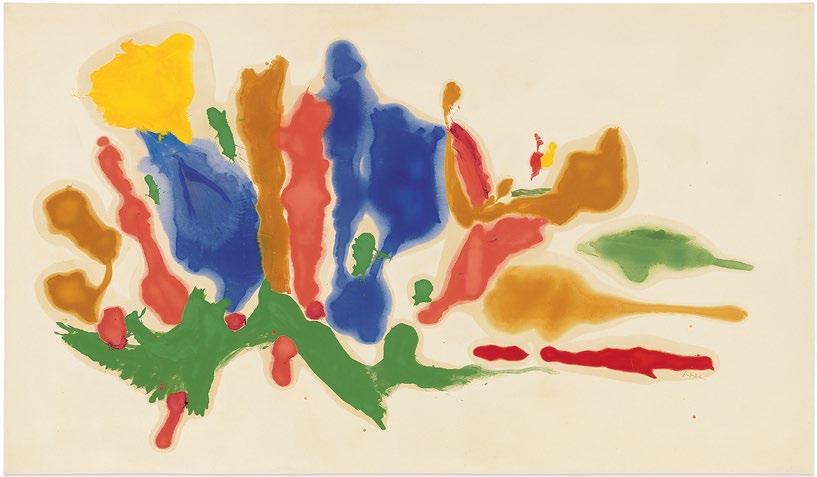

Helen Frankenthaler, Cool Summer, 1962, Oil on canvas, 69 3/4 x 120 inches (177.2 x 304.8 cm).

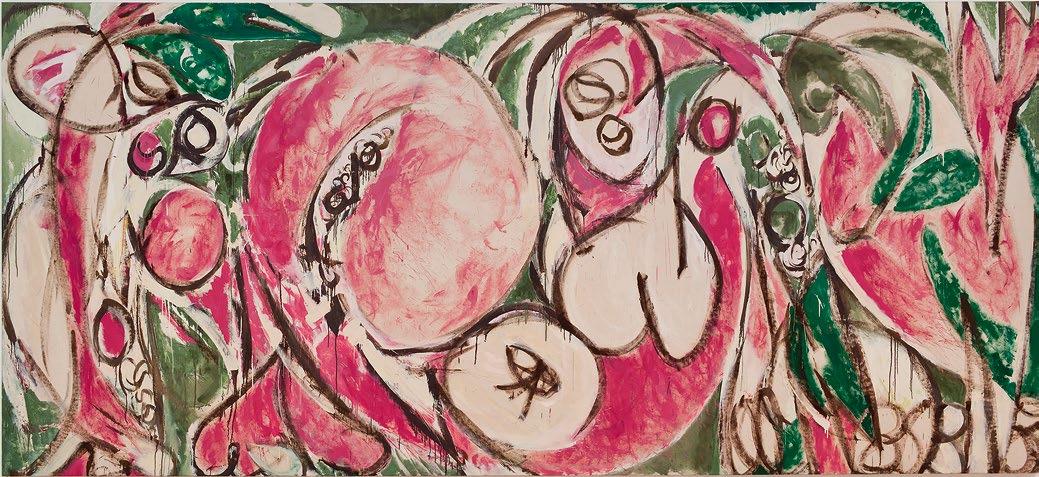

Lee Krasner, The Seasons, 1957, Oil and house paint on canvas, 92 3/4 x 203 7/8 inches (235.6 x 517.8 cm). The Whitney Museum of Art, New York, NY.

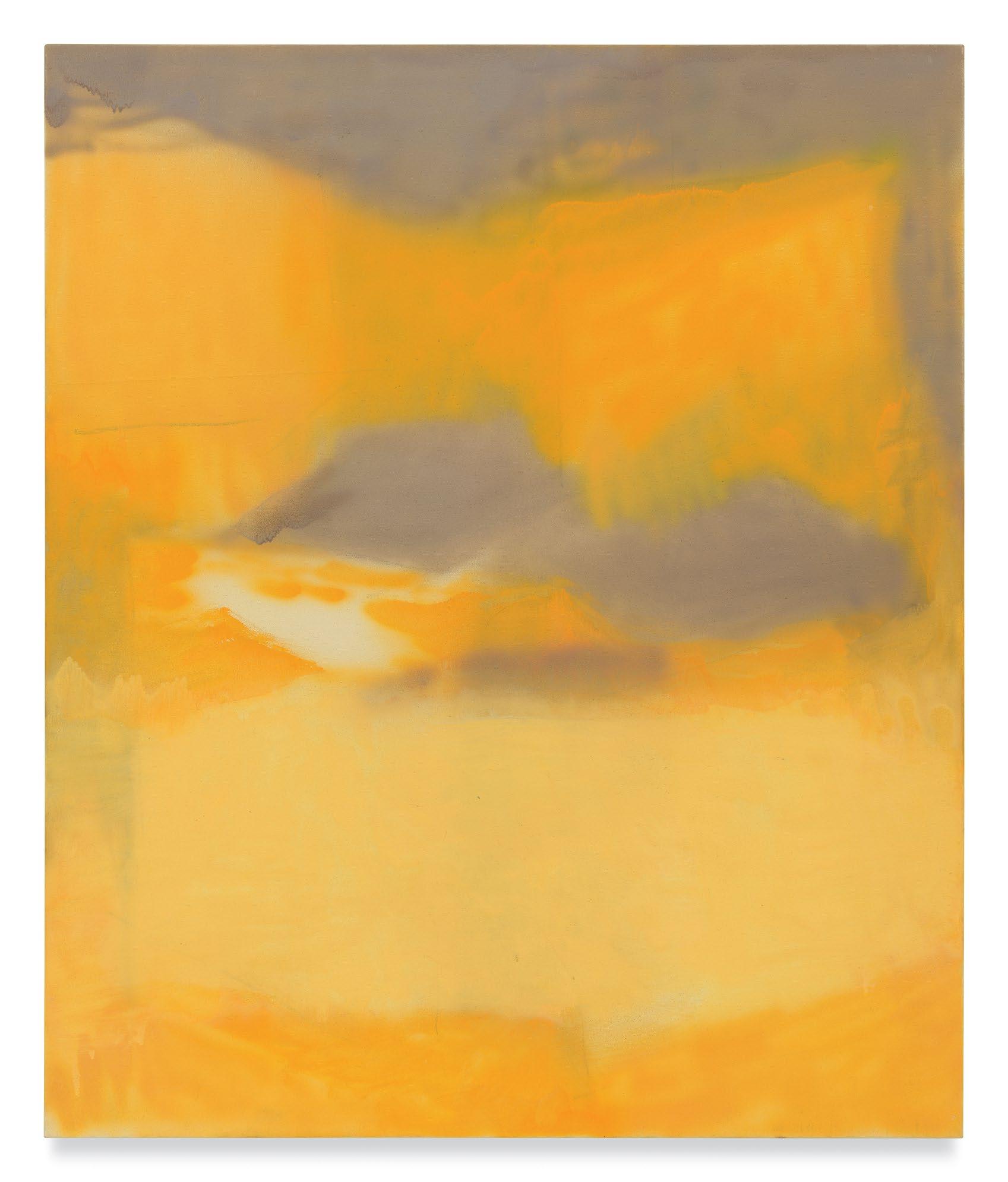

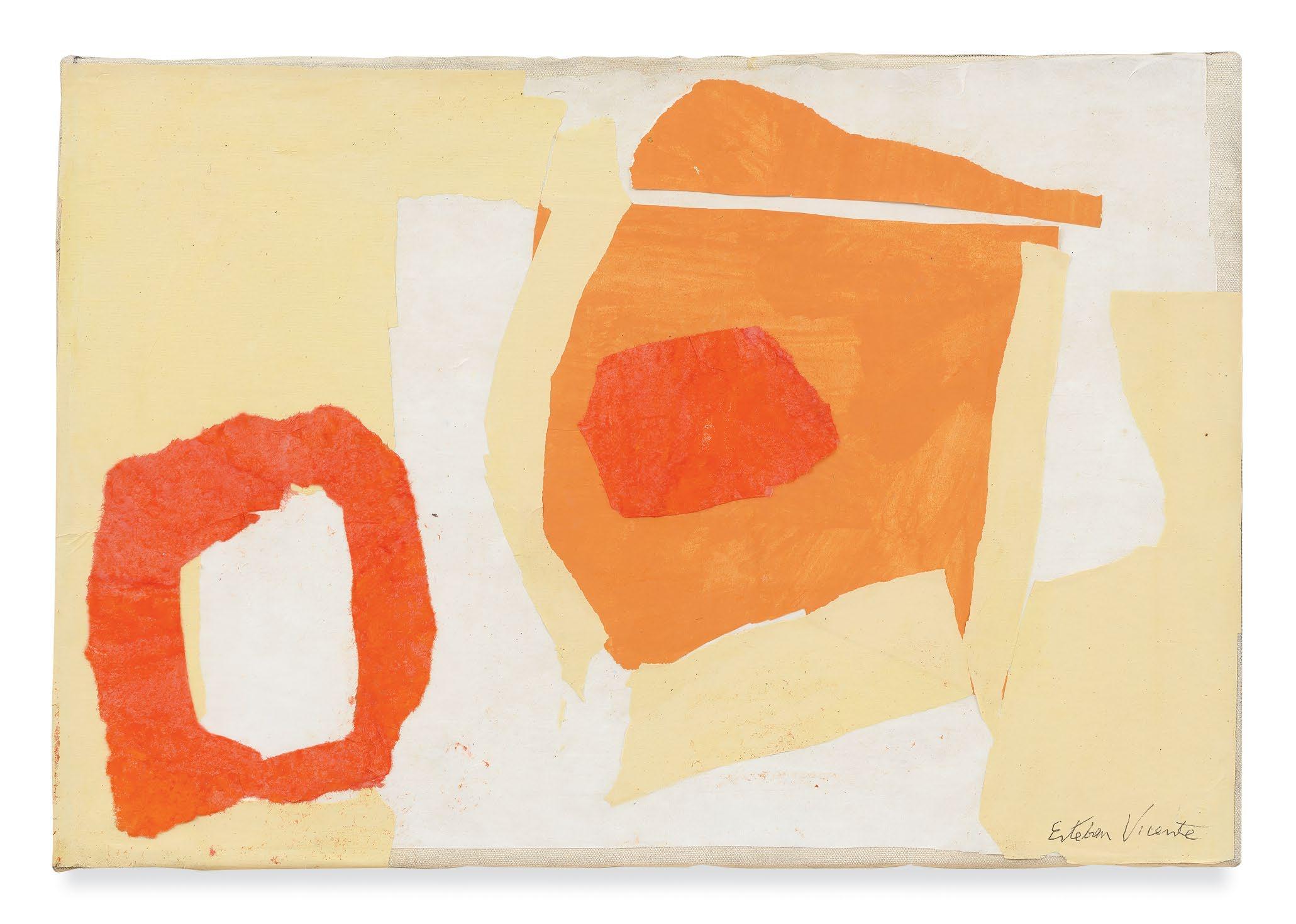

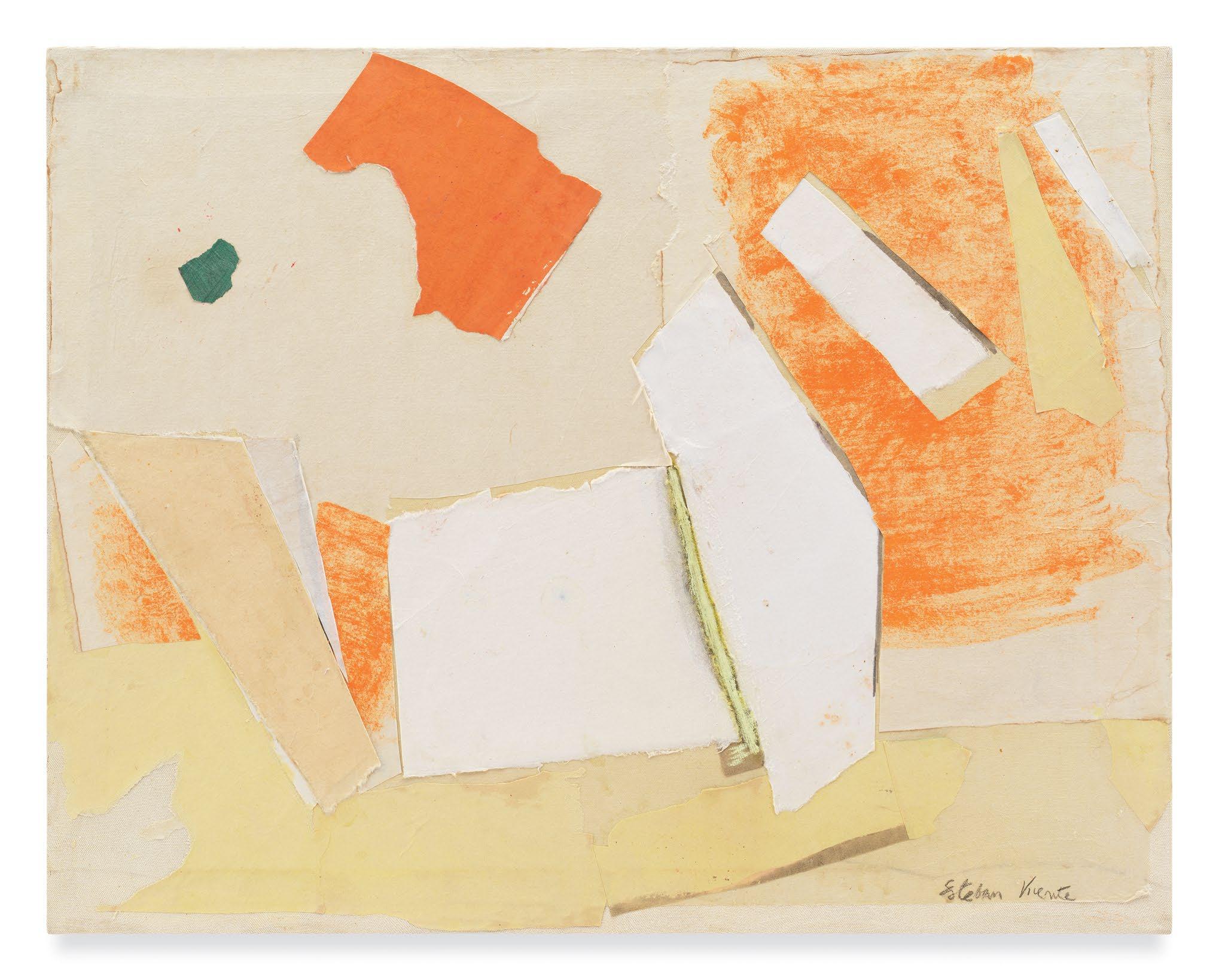

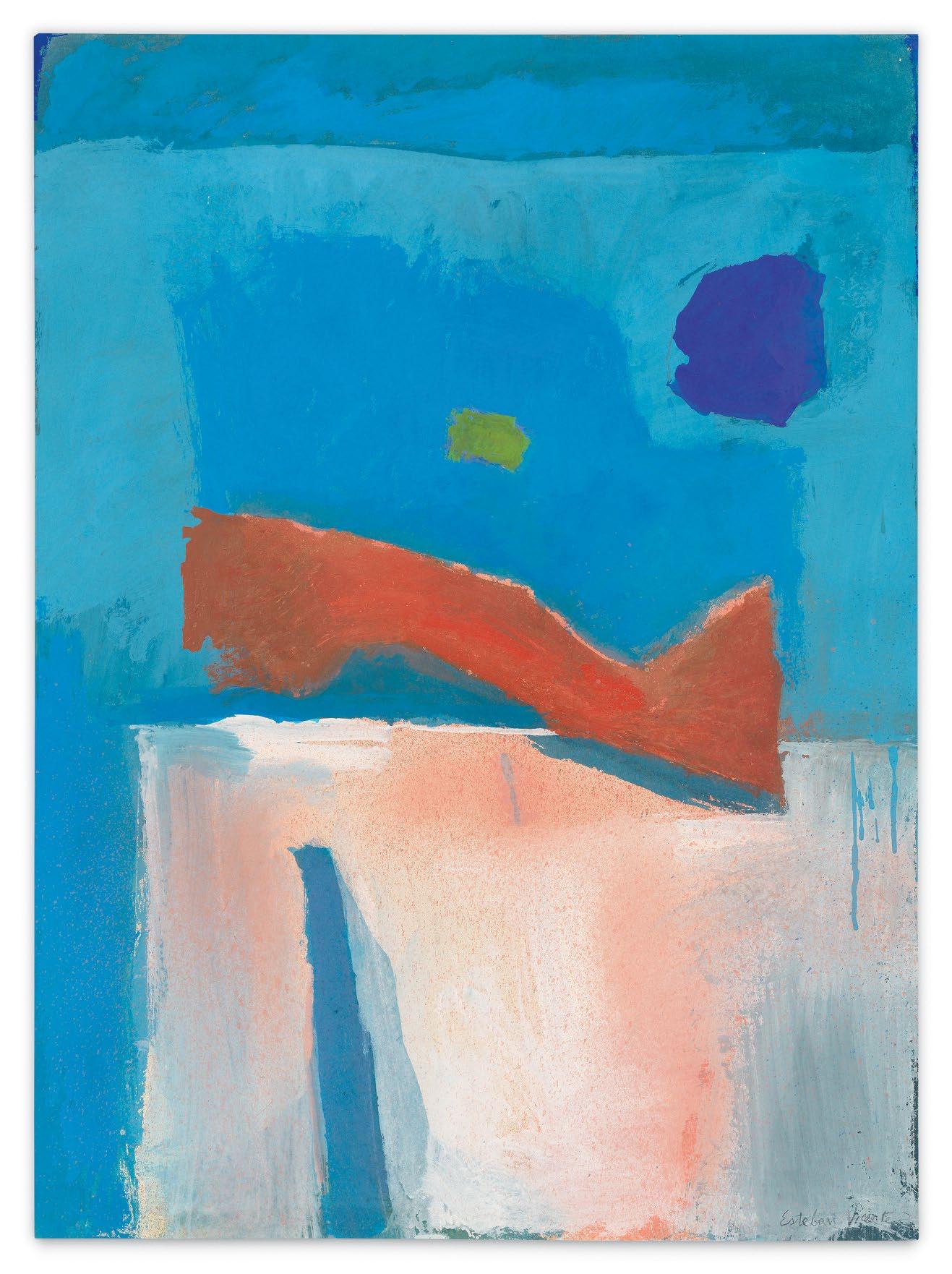

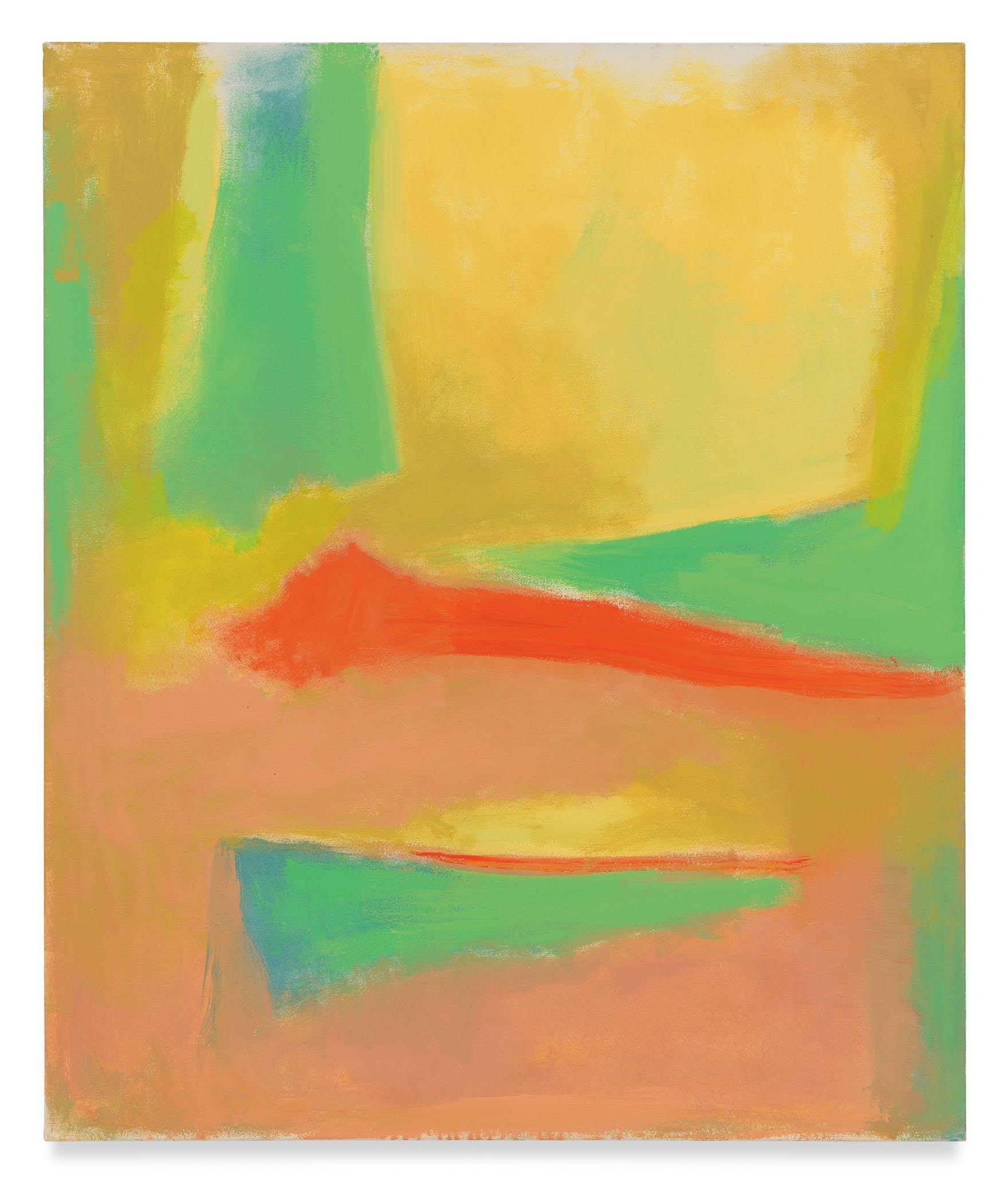

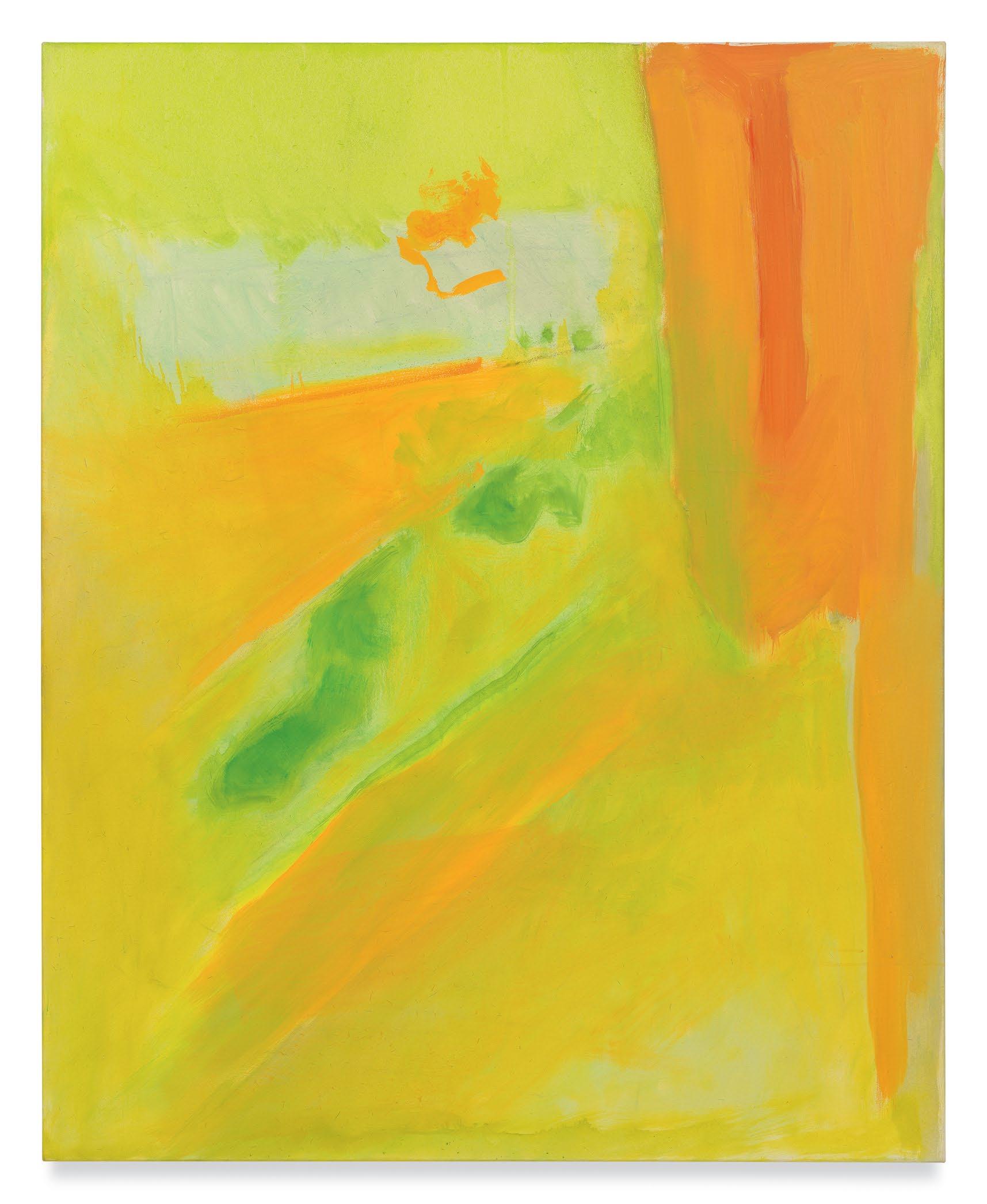

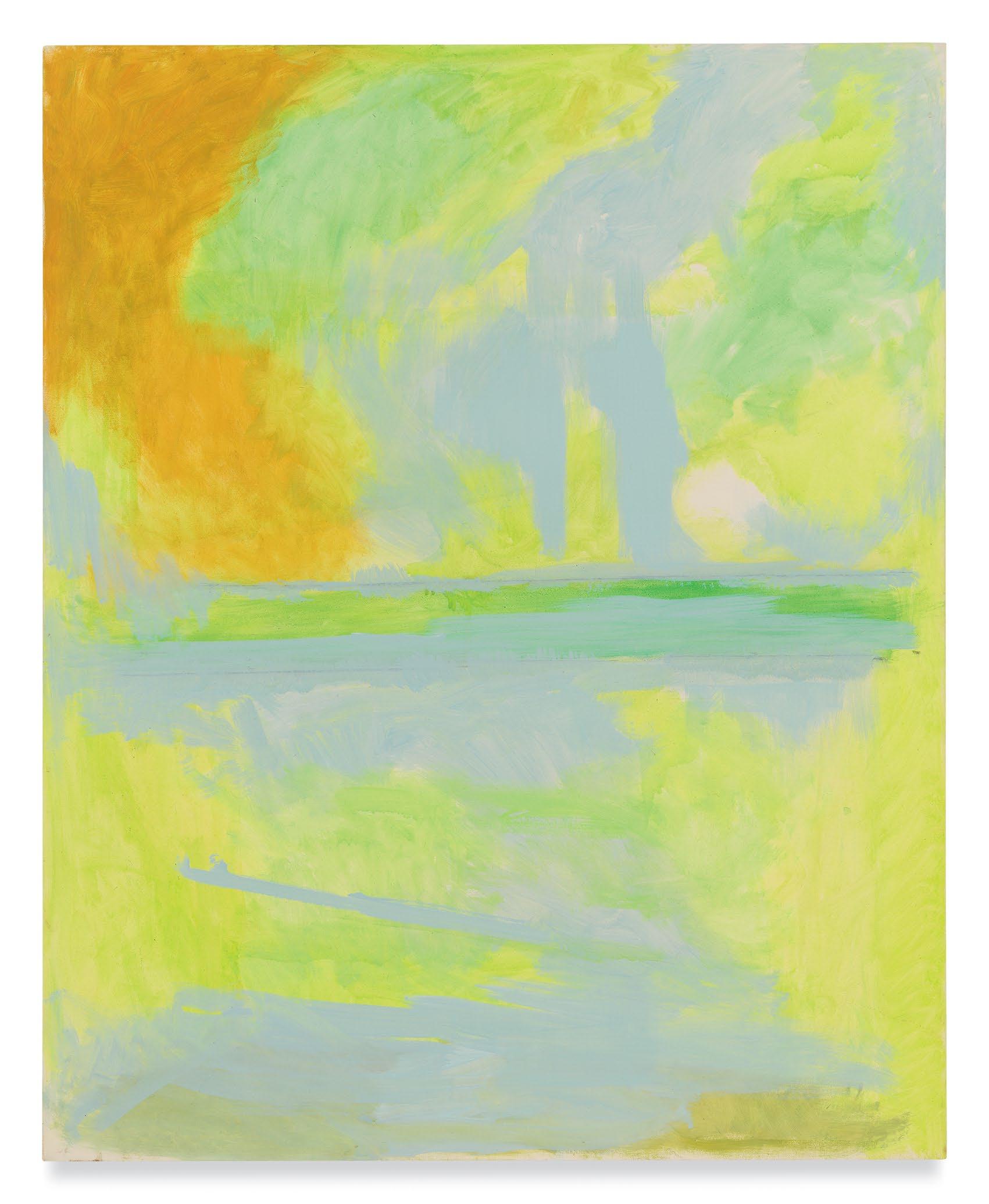

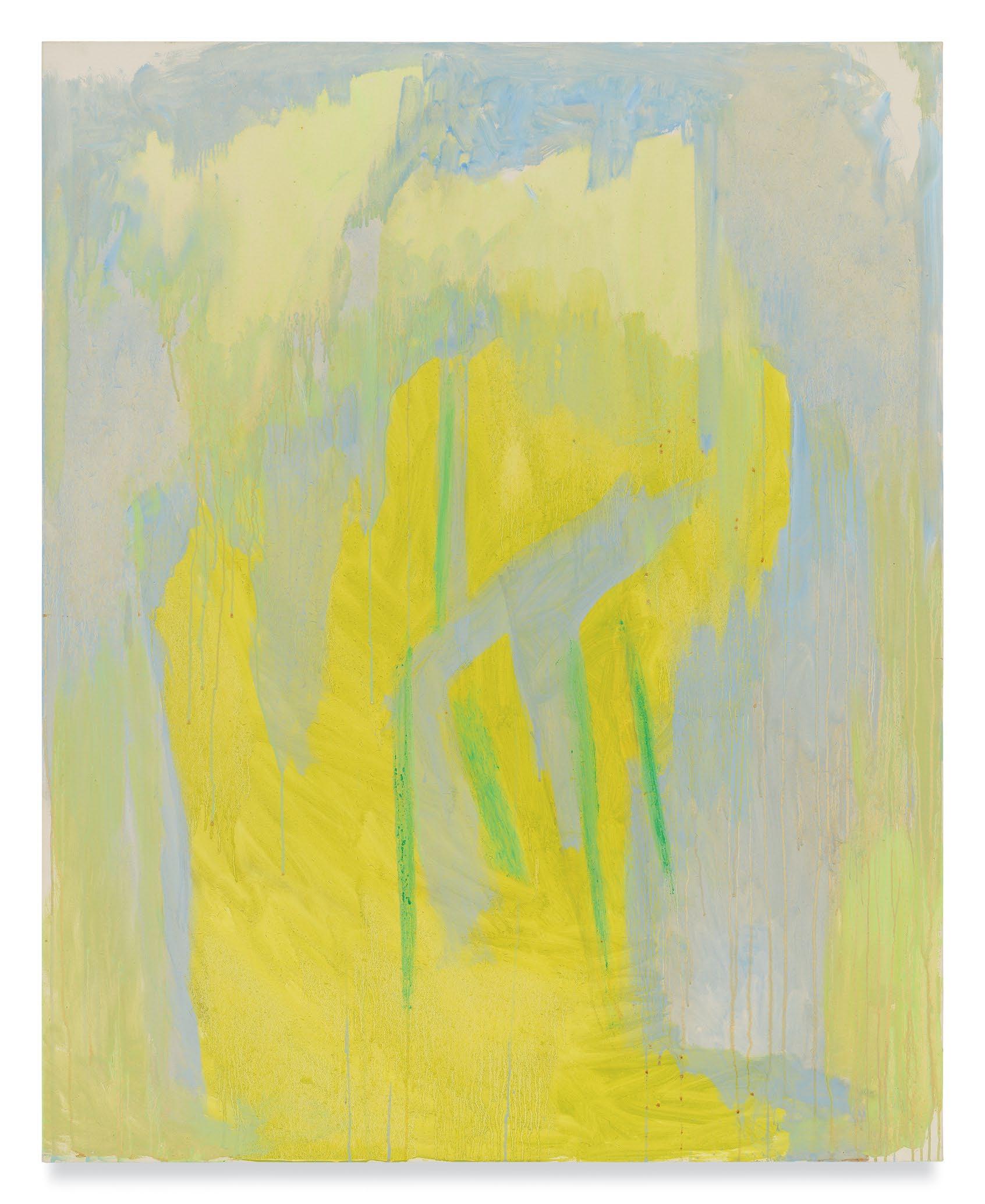

Like many of his New York School brethren, Vicente vacationed on Long Island, and in 1964 he purchased a farmhouse in Bridgehampton. There, he established a studio where he worked during the summer while tending to his large garden. Vicente created many compositions that evoked the sensations of his new home, including the collage Bridgehampton (1965), with its natural palette and forms that were reminiscent of the property’s outbuildings.8 The soft yellows and greens of later paintings, including Untitled (1996) (p. 57) and Untitled (2000) (p. 63), capture the light and coloration of spring vegetation, while Untitled (1999) (p. 61) reads as one of Vicente’s most literal landscapes, with a green horizon punctuating a verdant field and evocations of overhanging foliage in the top left corner. The foreground batch of ocher immersed in the greenery of Untitled (1996) (p. 55) suggests the partitions of flower beds, while the distant massing of tones in Untitled (1996) (p. 53) recalls groupings of flowers and other vegetation in his garden. Interconnecting forms, whether they are the paper collage elements of Monday Afternoon (1964) (p. 19) or patches of charcoal in Untitled (1989) (p. 31), conjure the joining of stone walls or pathways. Further references to agrarian landscapes predate Vicente’s purchase of the farmhouse in Bridgehampton, including in Water Mill (1964) (p. 17), where the stacking of forms and layering of pigment mimic human interventions in nature, such as the constructions of mills and fences. Indeed, cultivated land was a key element of the classical pastoral, as its picturesque order was in opposition to the sublimity of untamed nature. While the vivid central hues of Water Mill subtly contrast with the muted earth tones of its background, the rich palette and horizontal orientation of Vicente’s contemporary paintings, including No. 7 (1961) (p. 13) and Genesee (1963) (p. 15), further reflect Vicente’s lifelong study of nature, regardless of his location. For example, a residency at the Honolulu Academy of Fine Arts inspired collages like Marvell, Hawaii (1969) (p. 21), with deep blues evocative of the ocean and forms reminiscent of the island’s topography. While the spirit and tonality of these works suggest the bucolic, the pleasures derived from Vicente’s efforts stem from his sensuous handling of materials and nuanced explorations of light.

Pastoral Poetics

In addition to providing repose and inspiration, nature offered a structural tool during the heyday of abstraction. As Clement Greenberg suggested in “The Role of Nature in Modern Painting,” the logic of nature organized modernist art, beginning with Cézanne and Cubism. He believed that artists, by “describing and analyzing” the natural world in a “simplified way,” discovered the internal structure of the picture plane.9 Vicente acknowledged as much in an interview with Irving Sandler, describing how his development progressed from drawing on observations grounded in nature to making a study of cubist structures. By reconciling the two, he discovered the possibilities of abstract painting.10 Insisting that his abstractions were not translations of known images, Vicente described them as “interior landscapes,” ones developed through a “long process” of struggle and analysis. Where an “accumulation of experience” informs the “subject” of these “interior landscapes,” Vicente’s interest in the “capacity of color to become light” informs his pastoral projections.11

Harmony constitutes a central component of the pastoral, and a language of reductivism often provides the space and structure necessary to achieve it. The balanced simplicity of the rural existence, rather than the bucolic setting itself, became a rhetorical means of projecting an ideal reality, leading the critic and poet William Empson to describe the pastoral as “putting the complex into the simple.”12 As Empson and others observed, limitations—aesthetic or otherwise—maintain the capacity to reconcile oppositions and balance the discordant.13 Vicente embraced similar notions as an artist, restricting his palette while preferring to mix colors himself. He avoided what he called the “fanciful” in favor of “control,” writing that “art is based on order.”14 Vicente embraced restraint and avoided the Baroque, typically limiting the number of forms on his canvases, whether they were painted or collaged. The spareness of Untitled (1978) (p. 23), coupled with the ethereal placement of forms, illustrates this approach, while the cubist structure and reductive palette of Untitled (1996) (p.49) produces an intimate quietude. Indeed, the integrity Vicente locates within singular paper cutouts or softly layered tones focuses the eye on color harmonies, as he was careful to avoid “superficial” gestures that might rupture such repose.

Pastoral order gained further clarity through its “dialectical methodology,” a rhetorical device that dates to Virgil’s Bucolics. 15 Scholars contend that the “pastoral achieves significance by oppositions,” distinctions not limited to country and city, functioning instead as an allegorical trope wherein variances of scale, form, and identity can be contrasted.16 Vicente mastered similar formal dichotomies, situating paper edges, chromatic hues, painterly marks, and irregular shapes within balanced and subtle oppositions. He

acknowledged the personal impact of this practice, locating what he called a “valuable serenity” within the medium of collage.17

There is the white paper inviting me to unload my vision, my feelings, to find a new plastics reality. Like the gardening of the earth the surface gets richer and more sensuous; the limited area becomes intimate, luminous, an entity, and for moments it seems that the highest level of satisfaction will be attained.18

By retreating into an abstraction structured on nature’s order and attributes, Vicente created new pictorial realities predicated upon harmony, beauty, and pleasure, engaging the pastoral tradition in modernist terms.

Notes

1. Clement Greenberg, “Review of Exhibition of Hyman Bloom, David Smith, and Robert Motherwell,” The Nation (26 January 1946); reprinted in John O’Brian, ed., Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 2, Arrogant Purpose, 1945–1949 (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1986), 51.

2. Greenberg, “Review of Exhibitions,” 51.

3. Greenberg, “Review of Exhibitions,” 52.

4. Carter Ratcliff, “Urban Pastoral,” Arts & Antiques 37, no. 1 (Winter 2013–14): 74.

5. Ratcliff, “Urban Pastoral,” 75.

6. Timothy Gray, “Review: Process and Plurality in New York’s Urban Pastoral,” Contemporary Literature 44, no. 2 (Summer 2003): 367.

7. For more on Krasner’s relationship to the pastoral, see my essay: Daniel Haxall, “Lee Krasner’s Pastoral Vision: Collage and the Nature of Order,” Woman’s Art Journal 28, no. 2 (Fall/Winter 2007): 20–27.

8. Elizabeth Frank, Esteban Vicente (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1995), 71.

9. Clement Greenberg, “The Role of Nature in Modern Painting,” in Partisan Review (January 1949); reprinted in O’Brian, ed., Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 2, 272–73.

10. Irving Sandler, “A Tape-Recorded Interview with Esteban Vicente at His Home in East Hampton, August 26, 1968,” Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, 19-20.

11. Esteban Vicente, “Painting Should Be Poor,” Location 1, no. 2 (Summer 1964): 70-71.

12. William Empson, Some Versions of Pastoral (London: Chatto & Windus, 1935), 23.

13. Paul Alpers located precedents for Empson’s concept of the pastoral in Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Paul Alpers, “Empson on Pastoral,” New Literary History 10, no. 1 (Autumn 1978): 105.

14. Vicente, “Painting Should be Poor,” 70.

15. John Van Sickle, “Studies of Dialectical Methodology in the Virgilian Tradition,” Comparative Literature 85, no. 6 (December 1970): 884-928. See also his The Design of Virgil’s Bucolics, 2nd. ed. (London: Bristol Classical Press, 2004).

16. David Halperin, Before Pastoral: Theocritus and the Ancient Tradition of Bucolic Poetry (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983), 65-68.

17. Esteban Vicente, “Collage as Painting,” It Is 1 (Spring 1958): 41. For more on Vicente’s collages, see my essay: Daniel Haxall, “Unlimited Possibilities: Esteban Vicente and the Art of Collage,” in Concrete Improvisations: Collages and Sculpture by Esteban Vicente (New York: Grey Art Gallery and New York University, 2011).

18. Vicente, “Collage as Painting,” 41.

Siva, 1960

Oil on canvas

38 x 50 inches

96.5 x 127 cm

No. 7, 1961

Oil on canvas

27 x 36 inches

68.6 x 91.4 cm

Genesee, 1963

Oil on canvas

48 x 64 inches

121.9 x 162.6 cm

Mill, 1963

Water

Oil on linen

36 x 40 inches

91.4 x 101.6 cm

Monday Afternoon, 1964

24 x 30 inches

Mixed media collage

61 x 76.2 cm

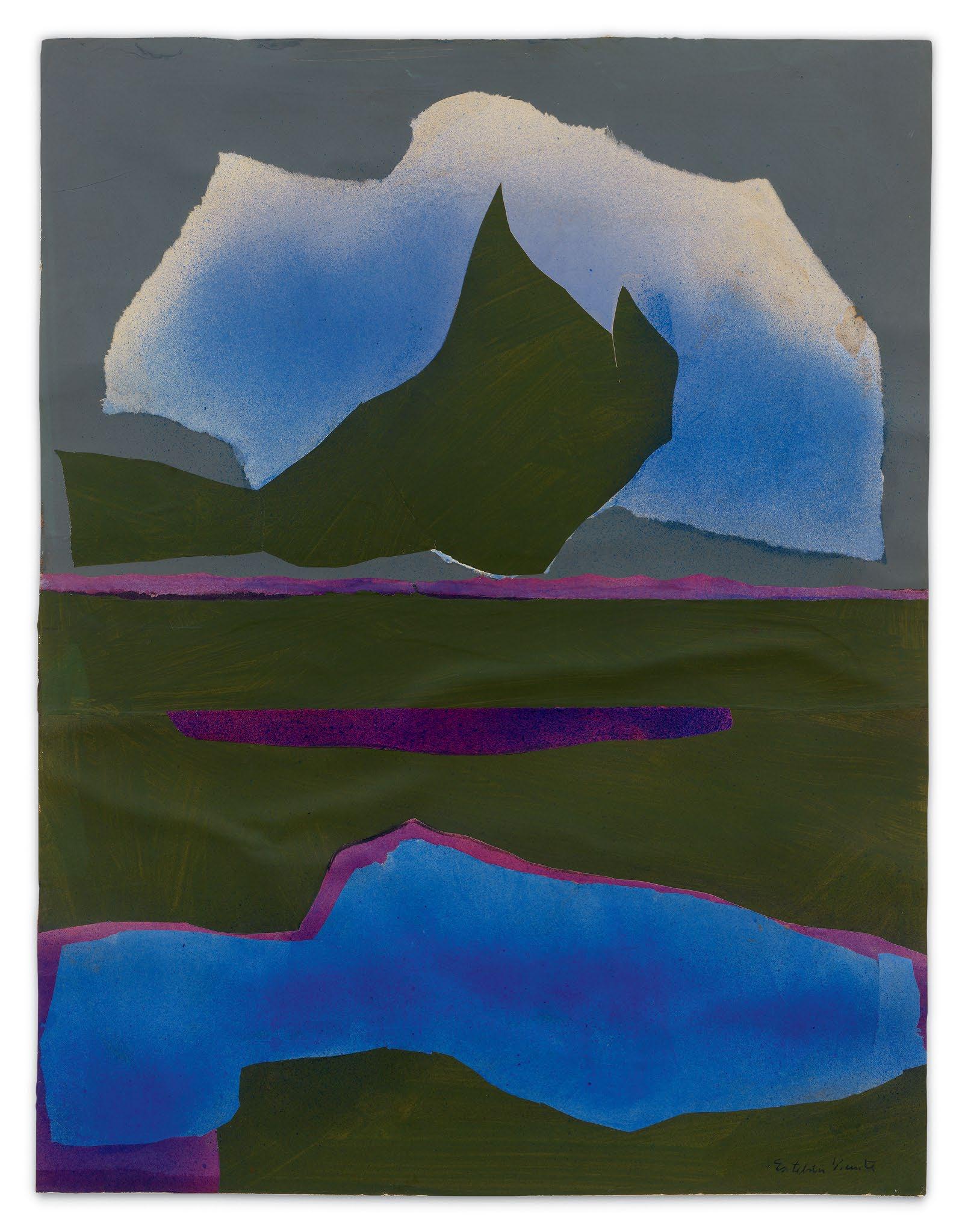

Marvell, Hawaii, 1969

Mixed media collage

52 x 40 inches

132.1 x 101.6 cm

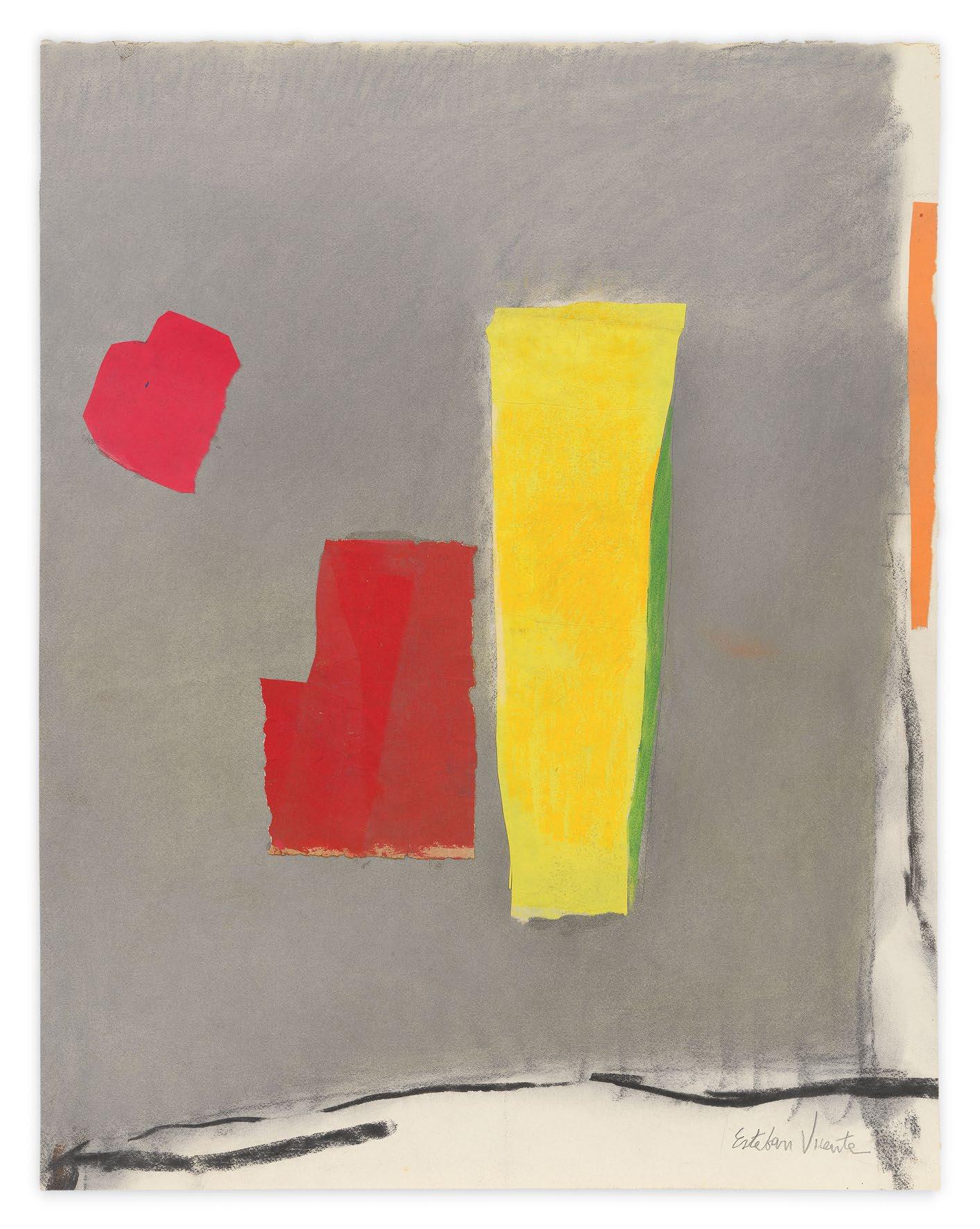

Untitled, 1978

Mixed media collage

33 x 26 inches

83.8 x 66 cm

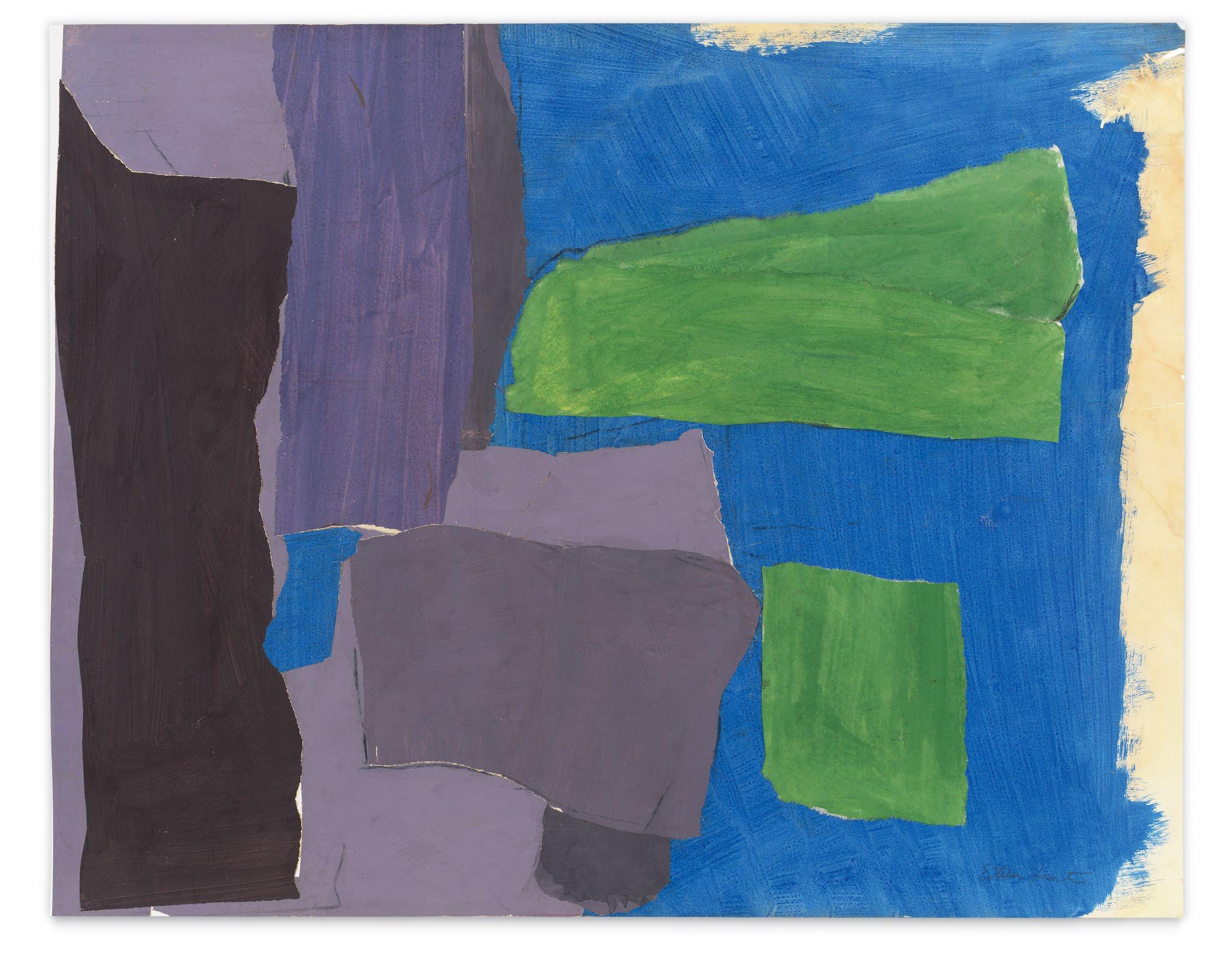

Untitled, 1981

Mixed media collage

30 x 44 inches

76.2 x 111.8 cm

Sideways, 1983

Oil on canvas

42 x 50 inches

106.7 x 127 cm

Untitled, 1988

Mixed media collage

26 x 34 inches

66 x 86.4 cm

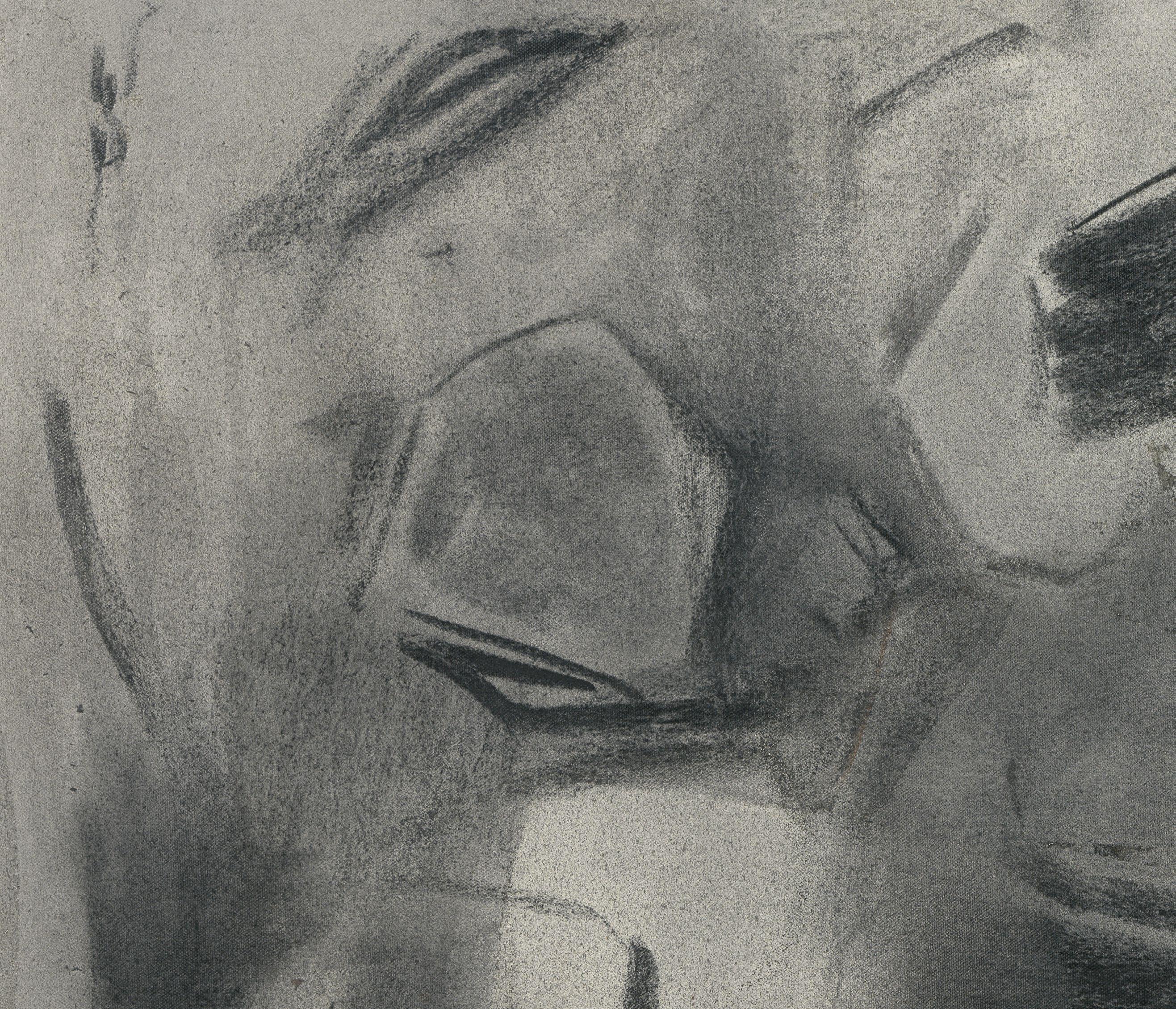

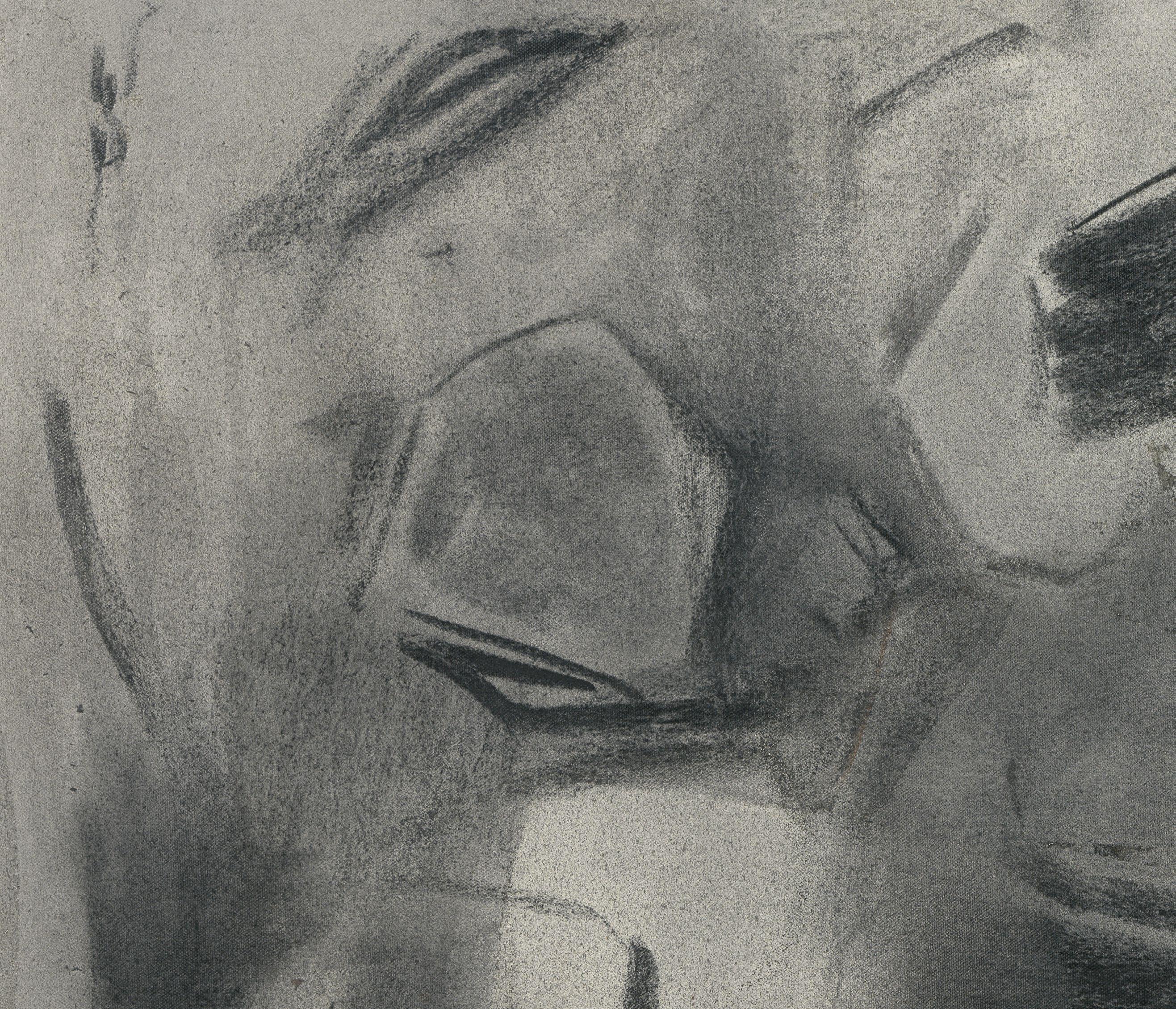

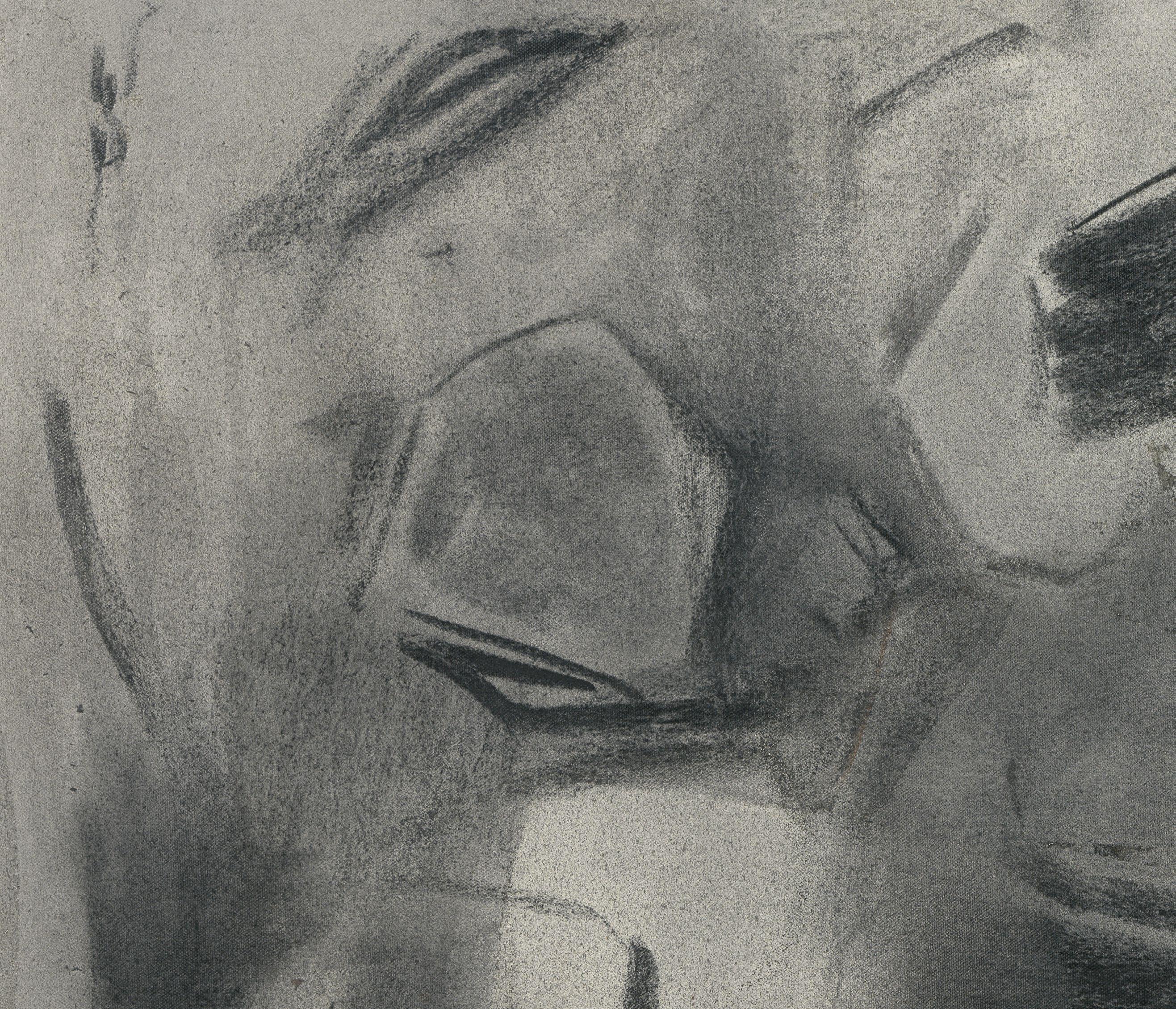

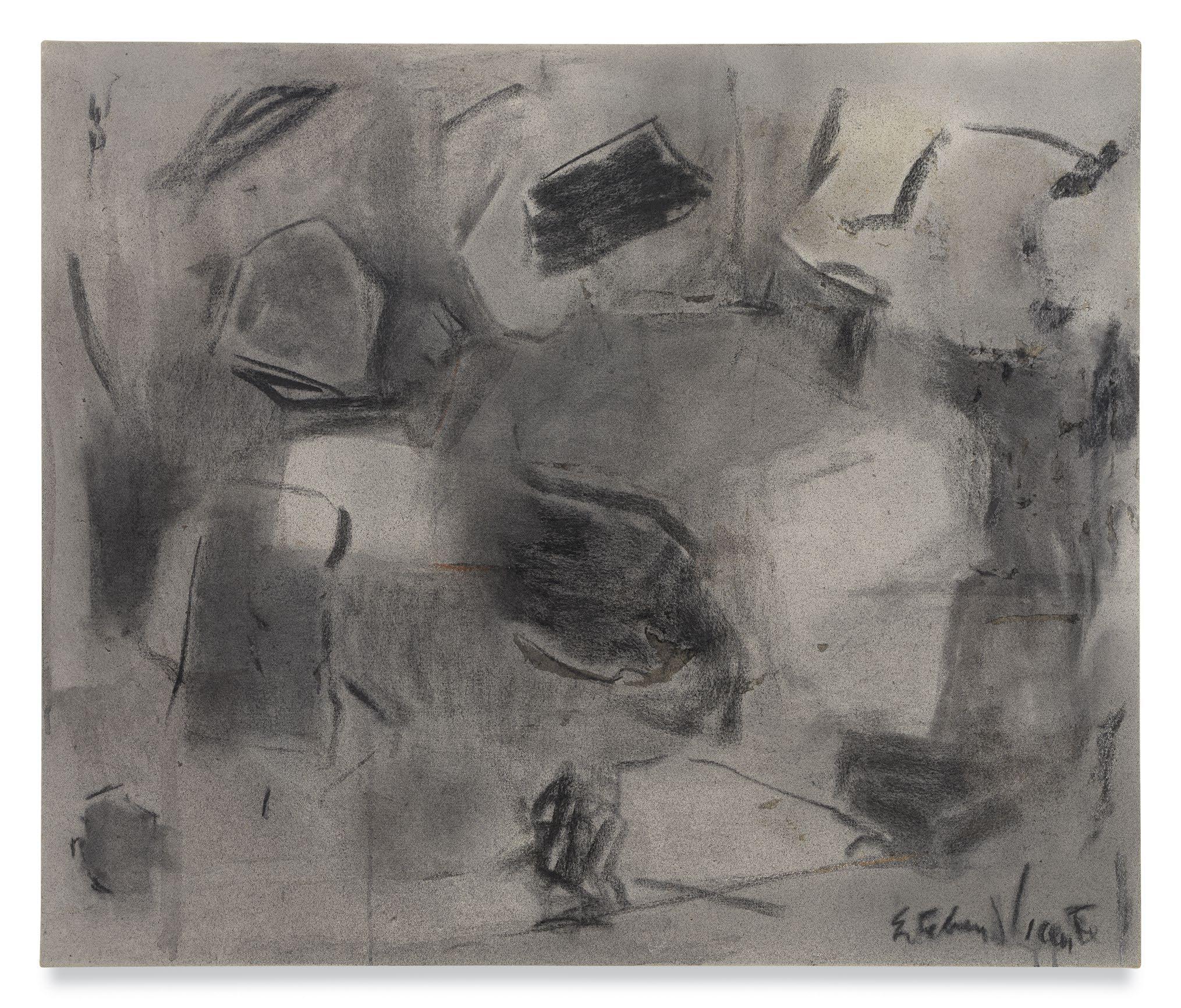

Untitled, 1989

Charcoal on canvas

32 x 38 inches

81.3 x 96.5 cm

Untitled, 1991

Mixed media collage

20 x 32 inches

50.8 x 81.3 cm

Untitled, 1991

Oil on canvas

44 x 62 inches

111.8 x 157.5 cm

Plurality, 1993

Oil on canvas

42 x 50 inches

106.7 x 127 cm

Instinctive, 1994

Oil on canvas

50 x 42 inches

127 x 106.7 cm

Sight, 1994

Oil on canvas

50 x 42 1/8 inches

127 x 107 cm

Untitled, 1994

Mixed media collage

15 x 22 inches

38.1 x 55.9 cm

Untitled, 1994

Mixed media collage

22 x 28 inches

55.9 x 71.1 cm

Untitled, 1994

Mixed media collage

19 x 28 inches

48.3 x 71.1 cm

Untitled, 1996

Mixed media collage

21 x 25 inches

53.3 x 63.5 cm

Untitled, 1996

Mixed media

19 x 24 1/2 inches

48.3 x 62.2 cm

Untitled, 1996

Oil on canvas

32 x 45 inches

81.3 x 114.3 cm

Untitled, 1996

Oil on canvas

42 x 50 inches

106.7 x 127 cm

Untitled, 1996

Oil on canvas

50 x 42 inches

127 x 106.7 cm

Experience, 1998

Oil on canvas

52 x 42 inches

132.1 x 106.7 cm

Untitled, 1999

Oil on canvas

52 x 42 inches

132.1 x 106.7 cm

Untitled, 2000 Oil on canvas

52 x 42 inches

132.1 x 106.7 cm

CHRONOLOGY

1903

Esteban Vicente is born on January 20 in Turégano, Spain, in the region of Castile y Léon. He is the third of six children of Toribio Vicente Ruiz and Sofia Pérez y Alvarez. His father, a Civil Guard officer, is also an amateur painter.

1904–1917

His father resigns from the Civil Guard to take up a post as a property administrator with the Banco de España in order to bring up his children in Madrid, Spain. Esteban studies at a Jesuit school. From the age of four, he accompanies his father on visits to the Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain.

1918

Vicente enters the Military Academy but leaves after three months. He then enrolls in the Escuela de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid, Spain, at the age of fifteen. He studies sculpture there for three years.

1922–1928

Develops friendships with the poet Juan Ramón Jiménez and members of Generation of 1927, an influential group of poets that included Rafael Alberti, Jorge Guillén, Pedro Salinas and Federico García Lorca. He also befriends the future film director Luis Buñuel, the writer and publisher Ernesto Giménez Caballero, and the painters Juan Bonafé, Francisco Bores, and Wladyslaw Jahl. He shares a studio on the Calle del Carmen with the American painter James Gilbert; their friendship continues until Gilbert’s death in the 1970s. He holds his first exhibition in 1928 with Bonafé at the Ateneo de Madrid, Madrid, Spain.

1929

Goes to Paris, France. Lives in a hotel and later shares a studio with the painter Pedro Flores. Earns a living retouching photographs and working on stage sets at the Folies Bergère. Visits Picasso at his studio on the rue La Boétie and participates in the Salon des Surindépendants. Meets the young American Michael Sonnabend, who later becomes his art dealer in New York, NY. Spends time in London, United Kingdom, where he visits the painter Augustus Johns and members of his circle.

1930–1934

He moves to Barcelona, Spain, and through his dealers, Joan Merli and Montse Isern, exhibits at the Galeries Syra. Returns to Paris, France (1930–31), thanks to a grant from the Junta para la Ampliación de Estudios for study abroad. Meets the Surrealist painter Max Ernst through an English friend, Darcy Japp. Again exhibits in the Salon des Surindépendants. Has one-man shows in Barcelona, Spain, at Avinyó (1931), Syra (1931), Busquets (1934) and Catalònia (1934). Exhibits in Madrid, Spain, in the salon of the Heraldo de Madrid (1934).

1935

In Barcelona, Spain, he marries Estelle Charney (Esther Cherniakofsky Harac), a young American studying at the Sorbonne. They spend a year on the island of Ibiza, Spain.

1936

Returns to Madrid, Spain, in July at the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. Works at camouflage in the mountains near Madrid before leaving for America. Lives on Minetta Lane, in Greenwich Village of New York, NY.

1937

His daughter Mercedes is born. Thanks to the painter and critic Walter Pach, he has his first solo show in New York, NY, at the Kleemann Gallery. At the request of Fernando de los Ríos, the Spanish ambassador to the United States for the Republic, he works at the consulate in Philadelphia, PA, until the end of the Spanish Civil War in 1939.

1939

Returns to New York, NY. Has his second individual exhibition at the Kleemann Gallery.

1941

Participates in a group show at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, PA.

1942–1946

He becomes an American citizen in 1942 and lives at 70 Grove Street in New York, NY. Teaches Spanish at the Dalton School and works as an announcer for Voice of America during World War II. His daughter, Mercedes, dies in 1943. Lives at 280 Hicks Street in Brooklyn, NY, and works in a studio at 43 Greenwich Street in Greenwich Village. He divorces Estelle Charney in 1945. He teaches painting at the University of Puerto Rico in San Juan, Puerto Rico from 1945–1946.

1947–1948

Returns to New York, NY. Lives and works at 138 Second Avenue. Forms friendships with the painters Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Franz Kline and Barnett Newman, and the critics Harold Rosenberg and Thomas B. Hess. He marries the literary critic and educator María Teresa Babín in 1948.

1949

Teaches at the University of California, Berkeley, CA, and begins to work in collage.

1950

Sets up a studio at 88 East 10th Street. His studio is on the same floor as de Kooning’s studio. Chosen by the critic Clement Greenberg and the art historian Meyer Shapiro for the show Talent 1950 at the Kootz Gallery in New York, NY. Participates in the Annual exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY. Has a solo show at the Peridot Gallery in New York, NY. Establishes lasting friendships with the painters Balcomb Greene, Aristodemos Kaldis, Elaine de Kooning, Mercedes Matter and Ad Reinhardt, and the sculptors David Hare, Ibram Lassaw, Philip Pavia, and George Spaventa.

1951

Helps organize and participates in the historic 9th Street exhibition. Included in the seminal work on the New York School by Thomas B. Hess, Abstract Painting: Background and American Phase. Works daily in his studio and receives visits from Philip Guston, Earl Kerkham, and Landes Leitin, as well as from the art collector Ben Heller. Chosen for the first group show of the New York School sent to France and Japan. Named director of summer courses at the Highfield Art School in Falmouth, MA, on Cape Cod.

1953

Elaine de Kooning’s article “Vicente Paints a Collage” is published in Art News. Vicente has one-man shows at the Allan Frumkin Gallery in Chicago, IL, and the California Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco, CA. Teaches during the summer at Black Mountain College in Black Mountain, NC. Other teachers include the poets Charles Olson and Robert Creeley, the composers Stefan Wolpe and John Cage, and the dancer Merce Cunningham. Among his students is the painter Dorothea Rockburne. He exhibits in several collective shows throughout the United States.

1955

Has solo show at the Charles Egan Gallery in New York, NY, a gallery that also exhibits work by Giorgio Cavallon, Joseph Cornell, Willem de Kooning, Kline, Reuben Nakian, and Jack Tworkov. Participates in several collective exhibitions.

1957

Has one-man show at the André Emmerich Gallery in New York, NY. Accepts a teaching position at New York University, New York, NY, where he remains until 1964. Considered by Harold Rosenberg to be one of the “leaders in creating and disseminating a style...[that] constituted...the first art movement in the United States.”

1961

Divorces María Teresa Babín and marries Harriet Godfrey Peters. Lives in Gramercy Park of New York, NY.

1962

Awarded a grant from the Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Los Angeles, CA. Teaches at the University of California, Los Angeles, CA, and Yale University, New Haven, CT.

1964

Founding member of the New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture, together with Mercedes Matter, Charles Cajori, and George Spaventa. With his wife, Harriet, buys a Dutch colonial farmhouse in Bridgehampton, NY. Sets up a studio there and plants a flower garden.

1965

Artist-in-residence at Princeton University, Princeton, NY, where he has an individual show. Travels to Mexico.

1966 Travels to Morocco.

1967

The death of his friend Ad Reinhardt deeply affects him.

1969

He is artist-in-residence at Honolulu Academy of Fine Arts, Honolulu, HI. Selected to exhibit in The New American Paintings and Sculpture: The First Generation, curated by William Rubin at The Museum of Modern Art in New York, NY.

1972

Josh Ashbery writes in Art News that Vicente is “widely known and admired as one of the best teachers of painting in America.” Moves to West 67th Street, New York, NY. Makes a second trip to Morocco.

1973 Teaches at Columbia University, New York, NY.

1975

He accompanies Harriet on a Jain pilgrimage to India.

1979

First solo show at the Gruenebaum Gallery in New York, NY.

1982 Travels to Türkiye with Harriet.

1983

Leaves his studio at 88 East 10th Street for a new one on West 42nd Street in the heart of the theater district.

1984

Receives an honorary doctor of fine arts degree from the Parsons School of Design in New York, NY.

1985

Receives the Saltus Gold Medal from the National Academy of Design of New York and an award from the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters as “one of the most gifted painters of the first generation of Abstract Expressionists,” with “a sensibility trained in Europe with the express purpose of opening the eyes and ears of Americans to the peculiar beauty around them.” Travels to Spain.

1987

Has a major retrospective in Madrid, Spain at the Fundación Banco Exterior de España: Esteban Vicente, Pinturas y Collages, 1925–1985, and also exhibits at the Yares Gallery in Scottsdale, AZ. Continues teaching at the New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture and maintains contact with students, artists, and friends of all ages.

1988

Receives the Childe Hassam-Eugene Speicher Purchase Award from the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters in New York. He exhibits at the Galería Theo in Madrid and is included in eight group shows, among them Aspects of Collage, Assemblage and the Found Object in Twentieth-Century Art at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York.

1989

Has a solo show of recent oil paintings and collages at the Berry-Hill Galleries in New York, NY.

1990

Has two one-man shows in Spain. Participates in the exhibition, Drawing Highlights: Eric Fischl, Roy Lichtenstein, Esteban Vicente, at the Parrish Art Museum in Southampton, NY.

1991

Receives the Gold Medal in Fine Arts from King Juan Carlos and Queen Sofía at the Prado Museum. Has a street named after him in Turégano, his hometown, in honor of his distinguished career as an artist. Teaches master classes at the Parsons School of Design and has six individual showings, including one at the Centro de Exposiciones y Congresos in Zaragoza, Spain, and another at the Galerie Lina Davidov in Paris.

1992

Travels to Spain to attend the opening of a solo show at the Palacio Lozoya in Segovia, Spain. Has three one-man shows in the United States: at the Berry-Hill Galleries in New York, NY, the Louis Newman Galleries in Beverly Hills, CA, and the Guild Hall Museum in East Hampton, NY. A selection of his work is chosen for the show Paths to Discovery: The New York School, at the Baruch College Gallery in New York, NY. He continues to teach master classes at the New York Studio School and the Parsons School of Design.

1993

Elected a member of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters at the age of ninety and awarded an honorary doctorate in the arts from Long Island University’s, Southampton College in Southampton, NY. Receives a Lifetime Achievement in the Arts Award from the Guild Hall Museum in East Hampton, NY.

1994

His most recent works are shown at the Century Association of New York, New York, NY. Celebrates his ninety-first birthday with an exhibition of his latest works at the New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture in the company of past and present students. Travels to Spain to visit family members, among them, his sister María, and attends the opening of his one-man show at the Galería Elvira González in Madrid, Spain. Five Decades of Painting opens at the Riva Yares Gallery in Santa Fe, NM.

1995

There is a major retrospective of his collages at the IVAM, Centre Julio González, in Valencia, Spain. Hudson Hills Press publishes the monograph Esteban Vicente by Elizabeth Frank. Vicente has exhibitions of recent works at the Riva Yares Gallery in Scottsdale, AZ, and the Berry-Hill Galleries in New York, NY. The Glenn Horowitz Gallery in East Hampton, NY, shows a selection of small collages and unique divertimentos.

1996

The exhibition Esteban Vicente, Collages 1950–1994 travels from Valencia, Spain, to the Patrick and Beatrice Haggerty Museum of Art, Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI. Vicente has solo shows

of recent works at the Riva Yares Gallery in Santa Fe, NM, and the Galería Elvira González, Madrid, Spain. He returns to Spain with Harriet for a family visit. In the fall, he moves his studio to 1 West 67th Street, next door to his apartment. He abandons the use of the spray gun.

1997

He paints twenty works in three months in his new studio. Receives visits from friends William Maxwell and Susan Crile, among others. His longtime friend Willem de Kooning dies. Writes an article in de Kooning’s honor in the ABC (Madrid). Holds exhibitions at The Century Association in New York, NY, the Riva Yares Gallery in Scottsdale, AZ, and Berry- Hill Galleries in New York, NY. Restoration work is begun on the future Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Esteban Vicente, sponsored by the Diputación Provincial de Segovia, Segovia, Spain. The board of trustees of the museum is created, and the painter and his wife make a formal donation of 148 works.

1998

The retrospective Esteban Vicente, Obras de 1950–1998 opens at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid, Spain. The exhibition later travels through Spain, to Santiago de Compostela (Auditorio de Galicia), Valladolid (Museo de la Pasión and Monasterio de Nuestra Señora del Prado) and Palma de Mallorca (Fundación Pilar I Joan Miró and Casal Solleric). He receives the Premio Castilla-León de las Artes. He attends the opening of the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Esteban Vicente in Segovia, Spain, where a permanent collection of his artwork offers a broad view of his entire career. He continues supervising his students’ work at the New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture, New York, NY, where he began teaching in 1964.

1999

At the age of 96, he continues painting every day. Travels to Spain with his wife, Harriet, where they are awarded the Gran Cruz de la Orden Civil de Alfonso X el Sabio for their contribution to art. Vicente is also named “Segoviano del Año” and awarded the Premio Arcale by the city of Salamanca. Has a one-man show at the Riva Yares Gallery in Scottsdale, AZ. A permanent room devoted to his works opens at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain. All these

honors, together with his participation in several exhibitions, mark the culmination of his recognition as an important figure in twentiethcentury Spanish art.

2000

Spends the winter in Bridgehampton, NY, rather than New York for the first time. Does several drawings and sketches. Has one-man shows of drawings and collages at the Galería Elvira González, Madrid, Spain, and the Berry-Hill Galleries, New York, NY. The magazine Reviewny devotes its Lifetime Achievement Award issue (July) to Esteban Vicente. In November, a retrospective exhibition, Esteban Vicente Esencial, is held at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Esteban Vicente, Segovia, Spain.

2001

On January 10, the artist dies at his home in Bridgehampton, NY, shortly before his ninety-eighth birthday. Complying with his wishes, his ashes are buried in the garden of his museum in Segovia, Spain. His death coincides with the homage that was planned for him earlier by the New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture, New York, NY, of which he was a founding member and teacher for thirty-six years. The book A Mis Soledades Voy, consisting of famous Spanish poems illustrated with engravings by Esteban Vicente, is exhibited. The book, which he had worked on until shortly before his death, is also shown at an exhibit in the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Esteban Vicente, Segovia, Spain, with the title El Color Es la Luz: Esteban Vicente 1999–2000. Included in the catalog are his writings on art. The show later travels to the Museo de Bellas Artes in Bilbao, Spain, and the Monastery of Nuestra Señora del Prado in Valladolid, Spain. A retrospective of his work is held at the Heckscher Museum of Art in Huntington, NY, in September. That same month, an exhibition devoted to various aspects of his work opens at the Monastery of Silos in Burgos, Spain, a space that regularly shows an important selection of major contemporary Spanish art.

SELECT COLLECTIONS

Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Oberlin, OH

American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, NY

The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL

Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, MD

Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA

Blanton Museum of Art, University of Texas, Austin, TX

Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY

Brunnier Art Museum, Iowa State University, Ames, IA

Buffalo AKG Art Museum, Buffalo, NY

Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown, OH

Carl Van Vechten Art Gallery, Fisk University, Nashville, TN

Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, TX

Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, DE

Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, MI

Eli and Edythe Broad Art Center, University of California, Los Angeles, CA

Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI

Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA

Grey Art Museum, New York University, New York, NY

Guild Hall, East Hampton, NY

Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY

Hirshhorn Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Honolulu Museum of Arts, Honolulu, HI

Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH

Housatonic Museum of Art, Housatonic Community College, Bridgeport, CT

Hudson River Museum, Yonkers, NY

Institut Valencià d’Art Modern, Centre Julio González, Valencia, Spain

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA

Memorial Art Gallery, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

Museo Colecciones del Instituto de Crédito Oficial, Madrid, Spain

Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Esteban Vicente, Segovia, Spain

Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao, Bilbao, Spain

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain

Museo Patio Herreriano de Arte Contemporáneo Español, Valladolid, Spain

Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, IL

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

National Academy of Design, New York, NY

National Gallery of Art, Corcoran Collection, Washington, D.C.

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, Australia

Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO

Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase College, State University of New York, Purchase, NY

The Newark Museum of Art, Newark, NJ

New Jersey State Museum, Trenton, NJ

Palm Springs Art Museum, Palm Springs, CA

Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, NY

Patrimonio Nacional, Madrid, Spain

Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, NJ

Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA

Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, MA

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY

Syracuse University Art Museum, Syracuse, NY

Tucson Museum of Art, Tucson, AZ

University of New Mexico Art Museum, Albuquerque, NM

Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT

Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN

Weatherspoon Art Museum, University of North Carolina, Greensboro, NC

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY

Williams College Museum of Art, Williamstown, MA

Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, MA

Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

ESTEBAN VICENTE

4 September – 25 October 2025

Miles McEnery Gallery 520 West 21st Street New York NY 10011

tel +1 212 445 0051 www.milesmcenery.com

Publication © 2025 Miles McEnery Gallery

All rights reserved Essay © 2025 Daniel Haxall

Associate Director Julia Schlank, New York, NY

Daniel Haxall is Professor of Art History at Kutztown University of Pennsylvania. A graduate of Villanova University, Haxall completed his doctorate at the Pennsylvania State University. A former fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum and Institute for the Arts and Humanities, he publishes on diverse topics in contemporary art including abstract expressionism, collage, the African diaspora, and the intersection of art and sport. Like the New York School, Haxall has embraced the pastoral, renovating an old farmhouse and gardening with his wife and young son.

Special thanks to Andrew Stein, Jennifer Stein, Eren Johnson, and The Harriet and Esteban Vicente Foundation, Blauvelt, NY

Figure Image

p. 4: © 2025 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / Photography by Rob McKeever, courtesy Gagosian

p. 5: © 2025 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / Digital image © Whitney Museum of American Art / Licensed by Scala / Art Resource, NY

All photos on the following pages are courtesy of The Harriet and Esteban Vicente Foundation

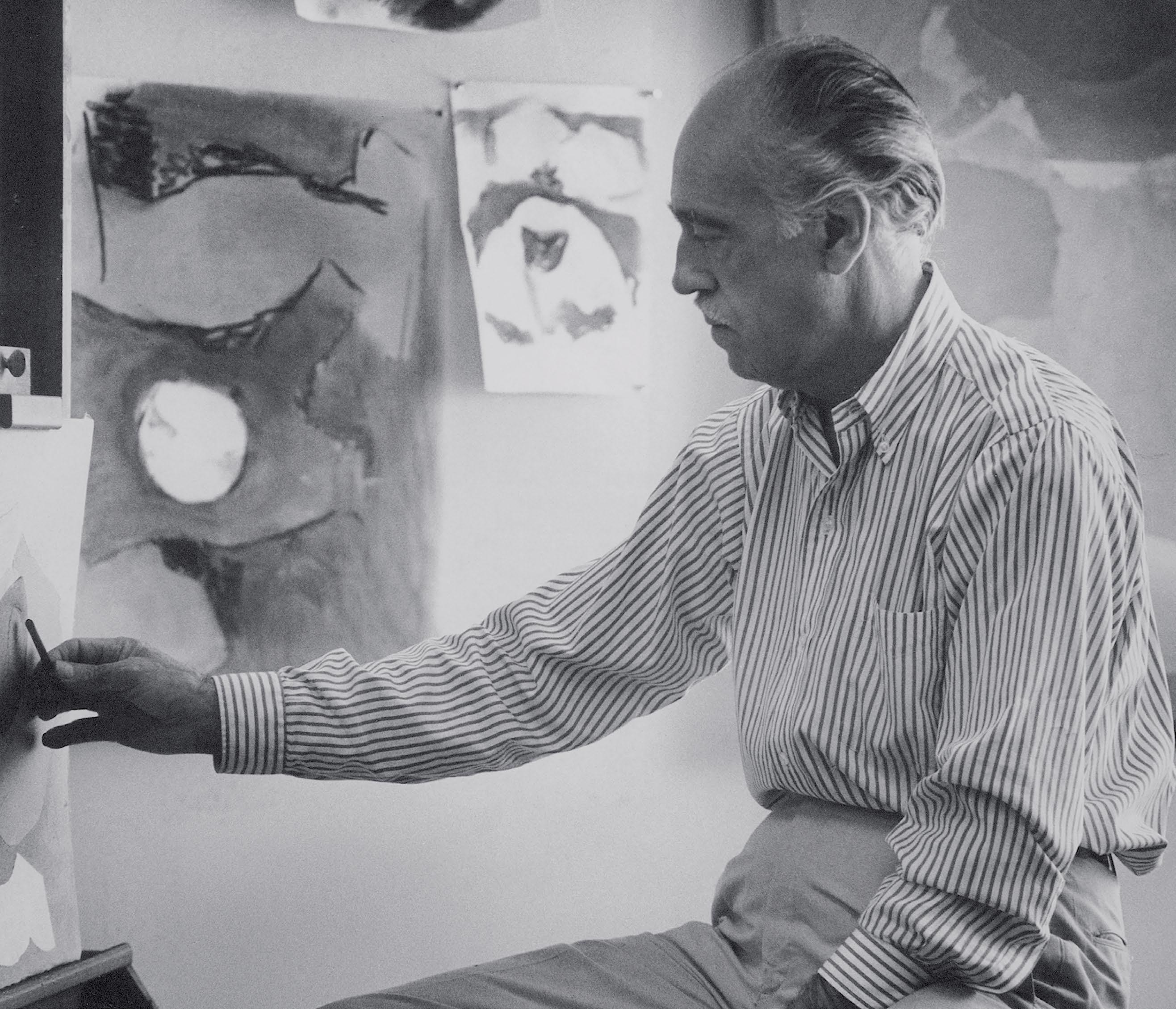

p. 2: Esteban Vicente working in his studio, Honolulu Academy of Arts, Honolulu, HI; photo by Francis Haar.

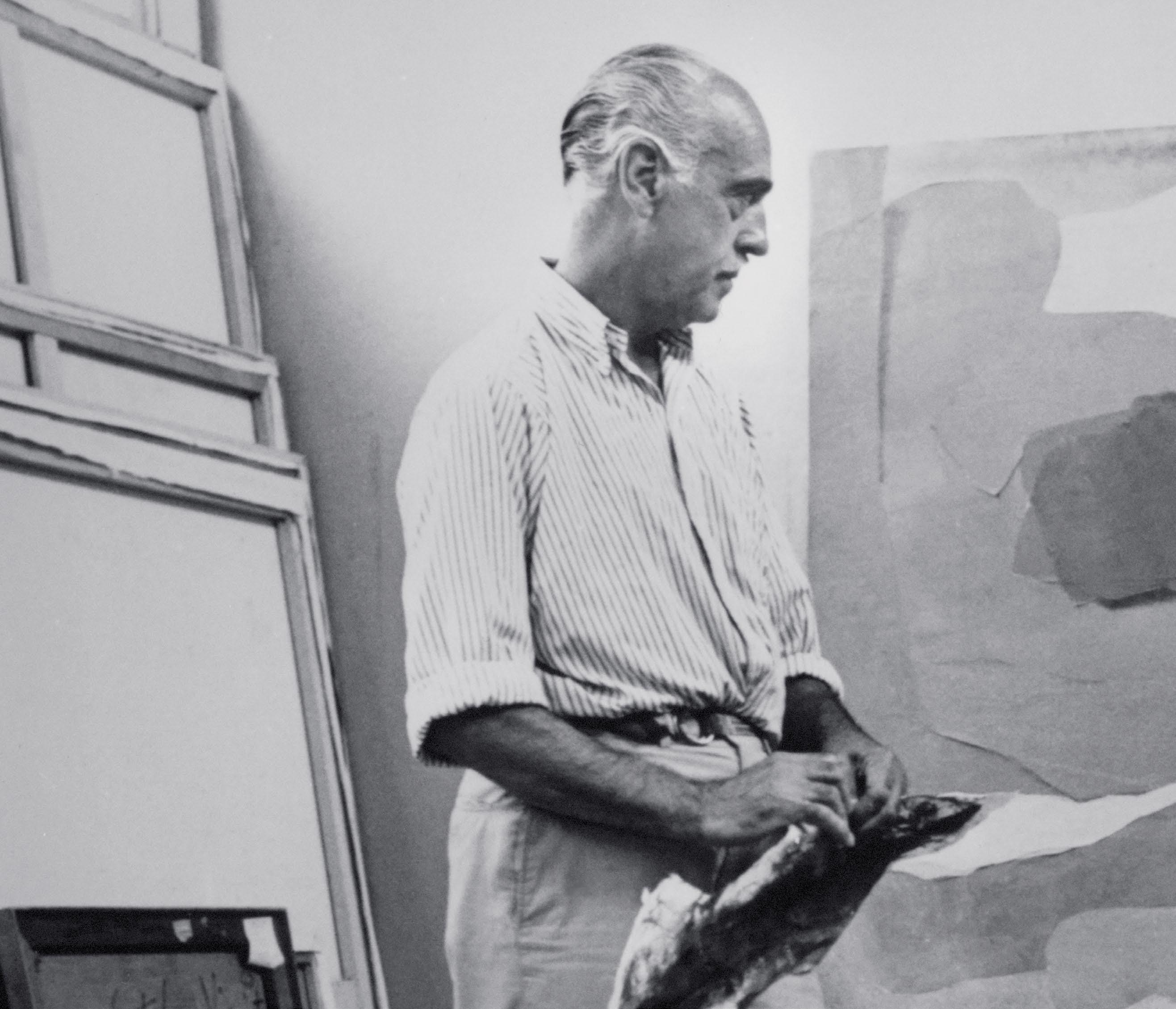

pp. 8–9: Esteban Vicente working in his studio, c. 1968; photographer unknown.

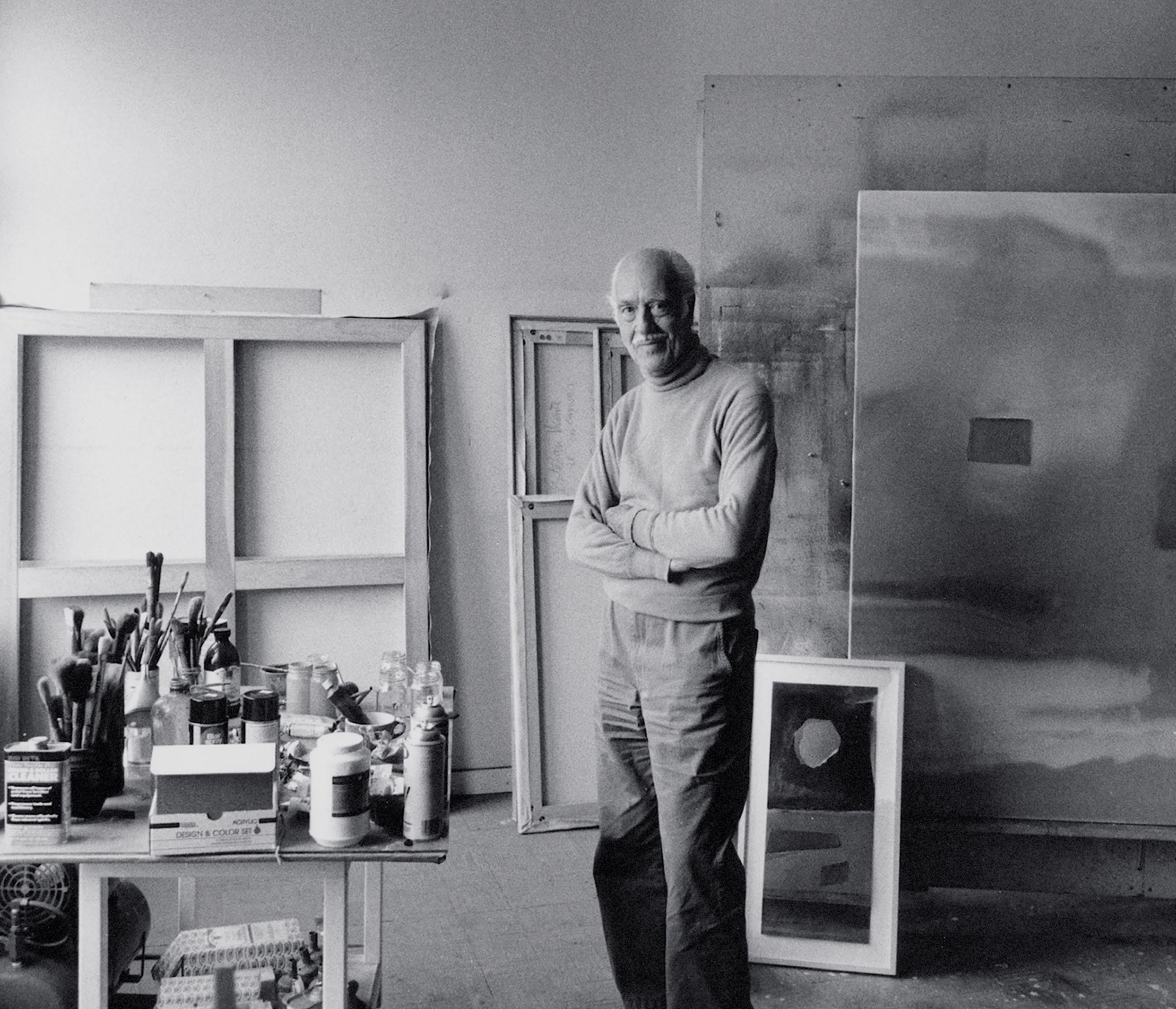

p. 64: Esteban Vicente standing in his studio, “The Armory,” New York, NY, February 1989; photo by Roberto Otero.

Photography by Dan Bradica, New York, NY Christopher Burke Studio, New York, NY

Color separations by Echelon, Los Angeles, CA

Catalogue layout by McCall Associates, New York, NY

ISBN: 979-8-3507-5139-0

Cover: Genesee, (detail), 1963 Endsheets: Untitled, (detail), 1989