SHANNON FINLEY

POWER PLANTS OF COLORS

Sebastian Preuss

The art historian T.J. Clark came up with a fitting parallel for how we view classic avant-garde artwork in today’s art world. In his 2001 book, “Farewell to an Idea,” he characterized modernism as the antiquity of our own era. As was once the case with Greek classicism, modernism has a canon of forms that no one—least of all an artist—can get away from. Whether this inevitable entanglement is programmatic in nature, is rooted in the visual memory of the unconscious, involves pictorial impetuosity, or is drawn from a storehouse of quotations is of no import. Modernism functions as our cultural and visual fertilizer.

And just as the true-to-life naturalism of Greek and Roman art maintained its presence for more than two thousand years, repeatedly surging forth only to subside once again, so have the formal disruptions, abstractions, reductions, and other innovations of modernism. Ever since cubism and Russian constructivism, since De Stijl and the Bauhaus, modernism has provided a universal language that is understood everywhere and that can be utilized by everyone, according to their personal preferences. The writer and curator Roger M. Buergel converted Clark’s revealing insight into a probing question: “Is modernism our antiquity?” In 2007, that was one of his three “leitmotifs” for the documenta 12 exhibition, which he curated in Kassel, Germany.

All these thoughts came to mind two years ago when I viewed the exhibition of Shannon Finley at the Mies van der Rohe Haus in Berlin. This renowned institution for contemporary art is situated in the Haus Lemke, the final building that Ludwig Mies van der Rohe designed in Germany (1932–33) before he emigrated to the United States. The architect created, with basic elements and on a moderate scale, something both prodigious and precious, a veritable jewel of modernism, on the outskirts of Berlin.

Mies planned many buildings for presenting art and housing collections; unfortunately, not all of his plans came to fruition. He had specific ideas about how pictures and sculptures should be displayed to their best advantage, either in inhabited spaces or within a museum. His architectural designs had an aura—something he expected from paintings and sculpture as well. The energized space of the Mies van der Rohe Haus heightened the exquisiteness of Finley’s paintings. And in return, the building took on a youthful aspect.

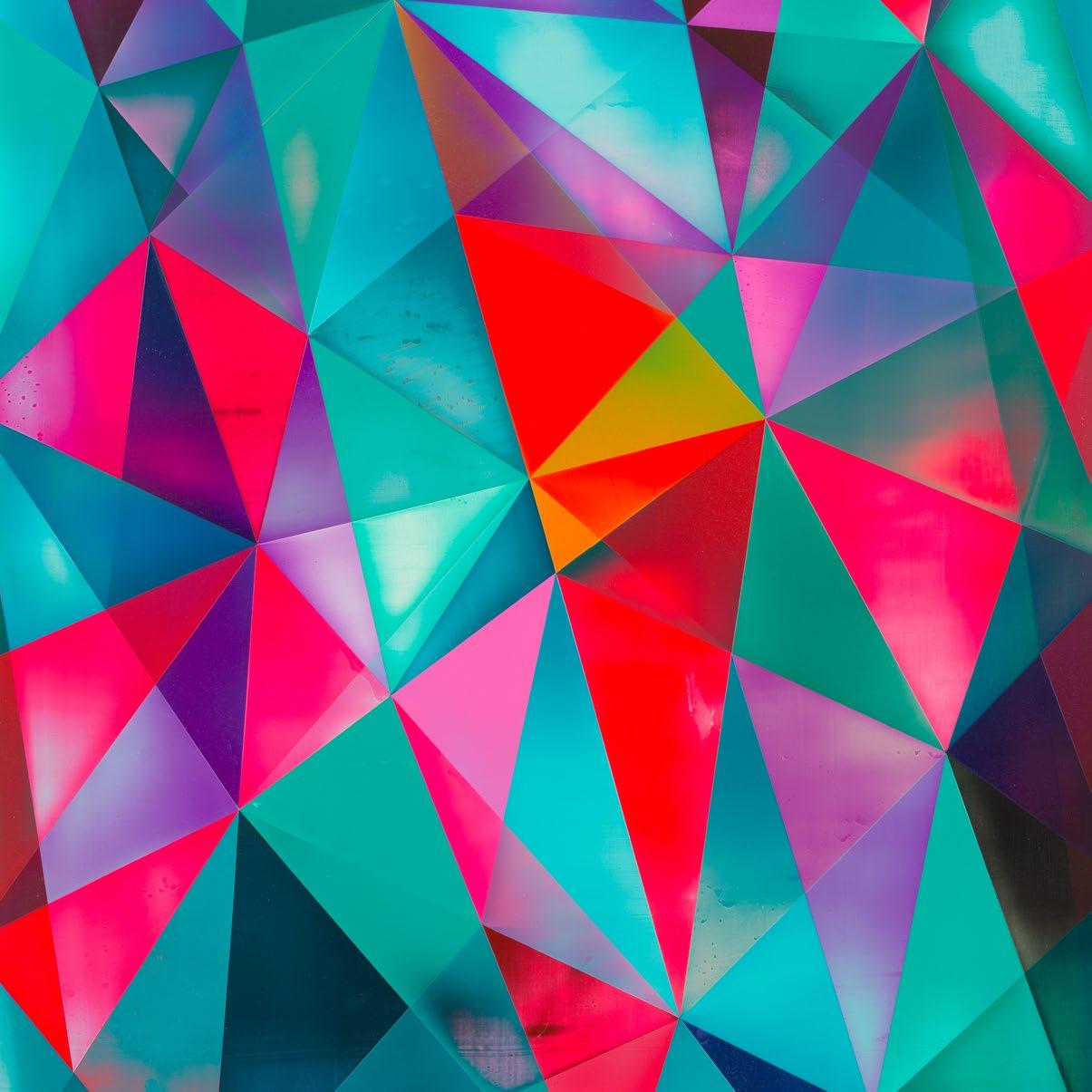

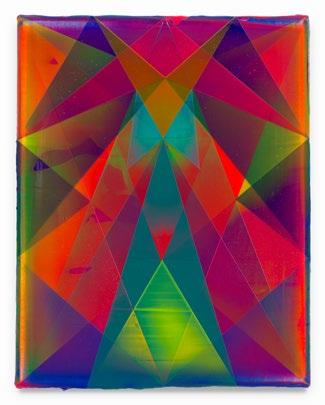

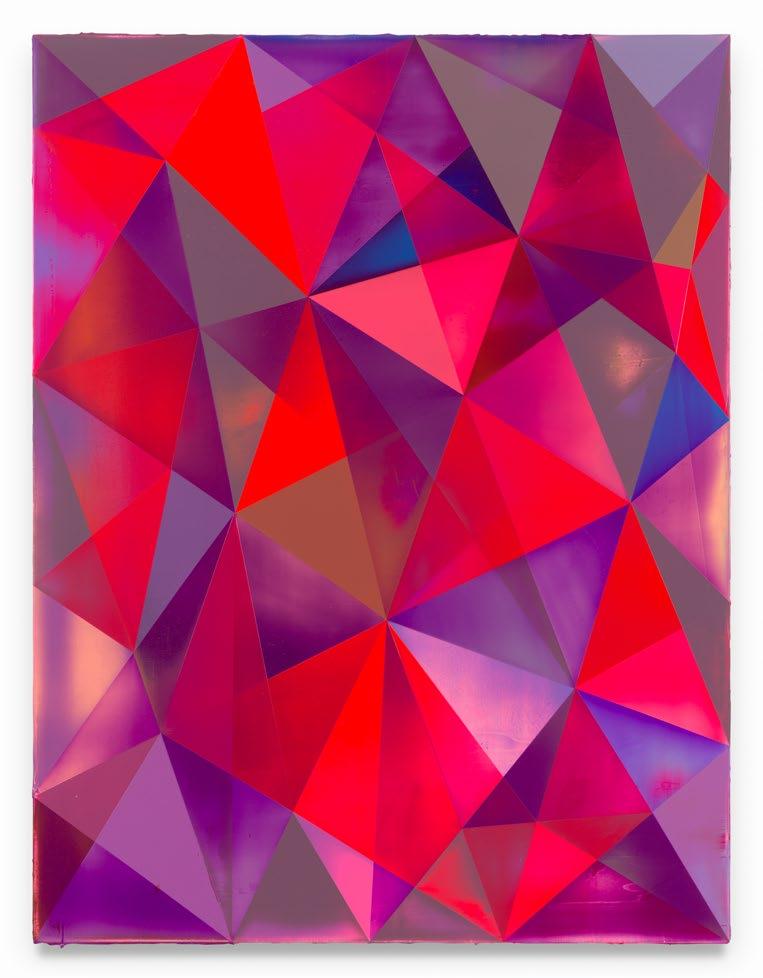

Finley’s painterly strategy achieves spectacular impact, with no need to make effusive gestures. It defines a space without overwhelming it. His is a manner of painting that restricts itself to fundamental elements and derives from them an abundant wealth of expression. It is a style of painting that, with its geometrical patterns and crystalline structures, takes on a timeless appearance even as it proves to be utterly contemporary. The longer one contemplates these pictures, the more intensively they begin to glow and the more painterly qualities they come to reveal. Finley’s surfaces are most often transparent, which allows the colors to shimmer from the depths of the painting. There is a magical play of shadow; chromatic fogs become discernible, then dissipate; signals are emitted by luminous, even glaring triangles. In between, opaque surfaces provide individual sections with hermetic coverings that enhance the depth of the overall composition. Finley is conducting an endless experiment, and from the fundamental elements of his artistry, namely geometry and color, he develops an almost inexhaustible spectrum of interacting forms.

These pictures trigger a wide range of associations, so there are diverse pathways for approaching them. One inevitably thinks of the abstractions of early modernism. Finley’s paintings bring to mind the manifold facets of cubism; the dynamic geometrical patterns of Robert Delaunay; Bruno Taut’s prismatic glass pavilion at the Werkbundausstellung in Cologne, Germany, in 1914; the crystalline acuity in the compositions of Lyonel Feininger; and the reverence felt for crystal by the founder of anthroposophy, Rudolf Steiner. Whoever recalls all these resonances in pictorial and historical memory will automatically see Finley’s painting in this context. The associations of other viewers might tend more toward op art, toward the artwork of Victor Vasarely or Bridget Riley; they would also think of abstract tendencies since the 1970s, from artists such as Imi Knoebel, Peter Halley, and others. Or of artists who began in the late 1990s to respond to Russian Constructivism, the Bauhaus,

Robert Delaunay, Champs de Mars: The Red Tower, 1911/23. Oil on canvas, 63 1/4 x 50 5/8 inches (160.7 x 128.6 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, Joseph Winterbotham Collection.

Lyonel Feininger, The Lady in Mauve, 1922, Oil on canvas, 39 x 31 3/4 inches (100.5 x 80.5 cm). Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, Spain.

Victor Vasarely, Cheyt-M, 1970, Tempera on canvas, 107 x 106 1/4 inches (271.8 x 269.9 cm); vertical axis 150 13/16 inches (383 cm). The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY.

and the classic abstractions of that era with irony and distorting appropriation. In Germany, mention could be made of Anselm Reyle, Tomma Abts, Markus Amm, Bernd Ribbeck, Gerold Miller, and many others; also situated in this setting would be international figures such as Jim Lambie, Monika Sosnowska, Martin Boyce, or Eva Rothschild.

It is a legitimate procedure inherent to customary art-historical methodology to perceive Finley in contexts such as these. Works of art give rise to associations, and every individual is free to pursue such correlations at will. But in the case of Finley, the reference to the modernist tradition is not entirely appropriate. He was born in 1974 in a small Canadian city in the vicinity of Toronto and grew up there. The classic modernism of Europe was at a great remove; so was the contemporary art scene in New York. When Finley began to study art at Nova Scotia College in Halifax in 1993, other influences were more important. Primacy was assigned to conceptual art, but that was already occasioning misgivings in Finley. In painting, it was Frank Stella who, with his flowing geometrical configurations, served as a pivotal point of reference. Finley was likewise deeply influenced by the postmodernist abstractions of Peter Halley and several other North American neo-geo artists.

But above all, Finley became intensively involved in the 2000s with the visual worlds of the digital

revolution: computer games, digitally edited music videos, 3D design, virtual reality, website design, and much more that was derived from the aesthetic of computer-oriented popular culture. All of that became a part of life for him and served as a primary source of forms, perspectives, pictorial depths, fragmentations, and the differentiated possibilities offered by geometry. The interplay between design at the computer and painting on the canvas became more natural to Finley. He gave no thought to Delaunay, Taut, and the Bauhaus while he was in Halifax or in New York, where he completed his art studies at Cooper Union and earned a living through web design.

In 2005 Finley visited Berlin, planning to stay for a month, and in 2006 he moved there. The move set many things in motion, he says. In Berlin, for the first time, he heard people referring to the Bauhaus or to Rudolf Steiner upon viewing his pictures. He began to occupy himself with European modernism. And he finally had enough space to actually paint in a studio.

His career picked up speed. He continued to use computers when he was drawing or experimenting with colors and forms. As technology improved, computer images became ever easier to handle. At the same time, Finley constantly refined his painting technique and made use of the possibilities offered by new acrylic paints, achieving increasingly differentiated results.

Beneath the top layer of every picture are five, ten, sometimes even more layers. Finley’s process is meticulous. Completing a painting can take three to five months. The initial forms, which are developed digitally as a rule, are masked; the paints are applied with a palette knife. (He uses brushes for retouching only.) Finley photographs each completed layer. Then, at the computer, he explores various possibilities for how things can proceed further with respect to color and form. He then returns to the canvas, does the preliminary masking, and paints in an analogue manner. When he completes the new layer, he engages in further digital examination and experimentation, then resumes the analogue painting.

Through the thin, superimposed layers, the pigments in the acrylic gel react with each other. Finley frequently strips away the paints so that the lower layers shine through. This causes his paintings to appear astoundingly transparent and deep. With each step that a viewer takes toward a Finley

painting, the impression changes. When standing close, the viewer sees that the transparency is sometimes engendered by bright streaks. Or by degrees of black shadowing, which Finley has used with particular intensity in several paintings in his most recent series, now on display at the Miles McEnery Gallery. In many places, he has left the black shadowing as it was, but here and there he has overpainted it with vivid colors within whose surfaces the clouding remains discernible. These complex superimpositions are conveyed to the viewer with emphatic immediacy. Instances of glowing and dimming, resplendent shimmer and dull mist, radiant coloration or earthy nuances can all occur simultaneously, exciting our vision, drawing our gaze into the depths of the pictures, stimulating our nerves, or generating contemplative quiet.

Likewise, the dynamic circular formations and the crystalline tempest of the clash of lines spur ocular delight and induce movement. The totality is a marvelously abundant pictorial experience, a visual source of energy. One could say that these pictures are color-operated power plants.

In terms of their content, Finley’s paintings are completely open. Viewers are invited to make their own optical discoveries; to pursue their own associations; to give free rein, in accordance with their personal taste and art-historical background, to the recollection of classical modernism.

“My focus is on finding a language that functions for everyone,” says Finley. Thus, his pictures grant viewers the freedom to look and think, a salutary prerogative in an art world that is increasingly dominated by multiple obsessive discourses. Geometry does not provide the content of Finley’s works, but it can be used as a structure into which his everyday visual experiences, as well as feelings and moods, flow. The titles of the pictures that sound so technical and scientific point toward physical phenomena and the digital sphere, but they also indicate how everything is becoming intermixed today. Finley gives absolutely no credence to the belief that artificial intelligence can function in art without personal subjectivity and human inspiration. His paintings demonstrate this conviction in an impressive and incisive manner.

Sebastian Preuss is a senior editor of the art magazine “Weltkunst.” He lives in Berlin. Translated from the German by George Frederick Takis.

78 3/4 x 63 inches

200 x 160 cm

Mondrian’s Garden, 2024

Acrylic on linen

59

150

Counterspace, 2025

Acrylic on linen

x 71 inches

x 180 cm

11 7/8 x 9 1/2 inches

30 x 24 cm

Destroyer, 2025

Acrylic on linen

Engadin, 2025

Acrylic on linen

47 1/4 x 35 1/2 inches

120 x 90 cm

Mine Craft, 2025

Acrylic on linen

59 x 45 1/4 inches

150 x 115 cm

59

150 x 115 cm

Polygoner, 2025

Acrylic on linen

x 45 1/4 inches

11 7/8 x 9 1/2 inches

30 x 24 cm

Sender, 2025

Acrylic on linen

150

Shadow World, 2025

Acrylic on linen

59 x 47 1/4 inches

x 120 cm

Signal Surfer, 2025

11 7/8 x 9 1/2 inches

30 x 24 cm

Acrylic on linen

Starburst, 2025

Acrylic on linen

47 1/4 x 35 1/2 inches

120 x 90 cm

150

Vector Flow, 2025

Acrylic on linen

59 x 45 1/4 inches

x 115 cm

150

We Dance, 2025

Acrylic on linen

59 x 45 1/4 inches

x 115 cm

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

SHANNON FINLEY MUTATIONS

26 June – 15 August 2025

Miles McEnery Gallery 515 West 22nd Street New York NY 10011

tel +1 212 445 0051 www.milesmcenery.com

Publication © 2025 Miles McEnery Gallery

All rights reserved

Essay © 2025 Sebastian Preuss

Photo Credits

p. 5: © The Art Institute of Chicago / Art Resource, NY/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

p. 5: © Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza / Scala / Art Resource, NY / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

p. 5: © The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation / Art Resource, NY

Associate Director Julia Schlank, New York, NY

Photography by Dan Bradica, New York, NY anna.k.o., Berlin, Germany

Catalogue layout by Allison Leung

ISBN: 979-8-3507-5070-6

Cover: Shadow World, (detail), 2025