Mitch Speed

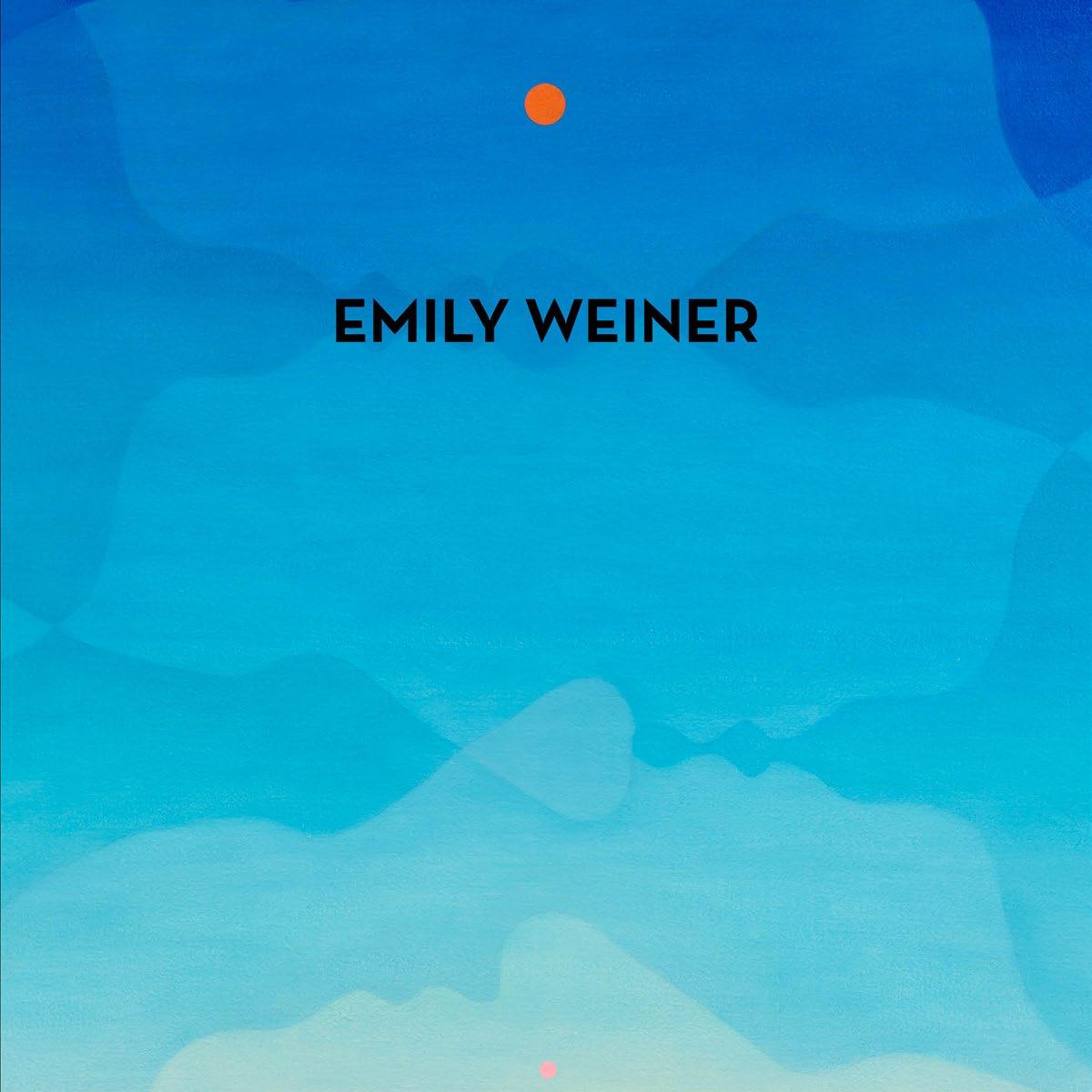

Among the many startling aspects of Emily Weiner’s recent paintings is their way of overlaying multiple orbits. Almost always, her compositions torque around a central pivot point. Often this role is played by a moon—crescent or full. At other times, this job is undertaken by the mirrored f-holes of a violin body, which hover in the pictures like inkblot insects. Once in a while, Emily’s compositions are cinched together by a rabbit’s glancing eye.

In a broader sense, the pictures cycle around layered sensory and symbolic modes. They signify and they reverberate: Look at them in a series, and you see icons and forms looping, like notes in music. They suggest an autonomous iconographic history, albeit one strangely plugged into the world and history we know. Paradoxically, each image bridges a split perception: On one side, we have the realm of symbols, on the other, a resonant capacity, shared between the body and musical instruments. In this way, vision is drawn into cross-sensory alignment: The eye is nudged toward sound, and the mind creeps toward metaphor. Every painting draws strength from its perpetually off-register position.

To follow these paintings where they are capable of taking us, I’ve been entertaining a neologism: psych-rock mysticism. The term came to mind after I scrutinized the white rabbit in Magician’s Assistant (2025). Shown in profile, the little animal seems to gaze directly at us. I’m pretty sure he’s also looking everywhere at once (a clever allusion, maybe, to the scope of interests in Emily’s body of work). The rabbit’s inner ears are a warm pink. And, like a bracketed punctuation mark, his eye is framed by two of the aforementioned f-holes, rendered in a midnight blue that is almost black. In

violins, these shapes facilitate the outward passage of sound waves. Embedded in this pictorial space, they suggest that the act of looking entails a sonic under-dimension. Paintings can hint at things like this. They can remind us of perception’s compound nature.

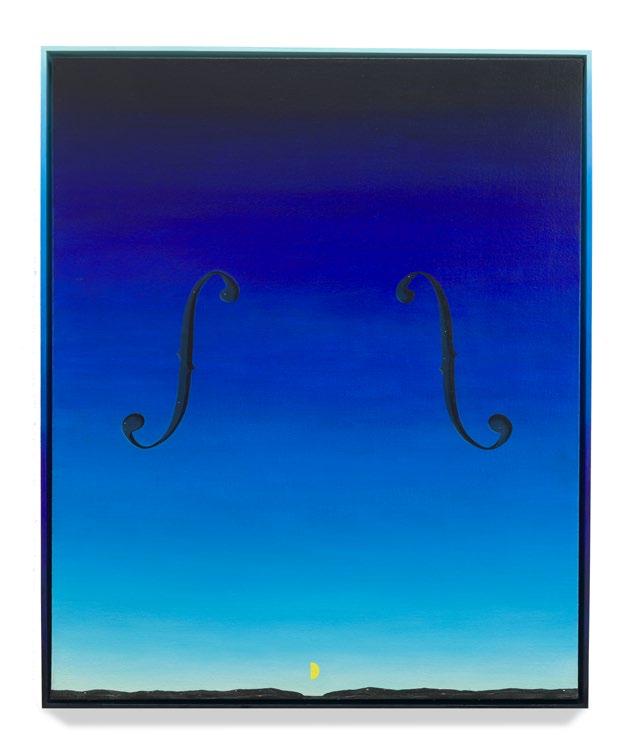

Over and over again, eye and ear, image and tone converge. Signs drift and become affixed to new meanings. In Resonance (2025), the f-holes return. Now they hang in a darkening sky. On close inspection, the shapes are three-dimensional and bedazzled with little stars. In an odd way, this suggests empathy. It’s as if, noticing a sky rendered dimensionless by light pollution, the f-hole shapes decided to rectify this absence. This magical implication pushes and pulls with the work’s formal rigor. Beneath the floating black shapes, there is a thin band of silhouetted landscape, which must be a nightfall desert.

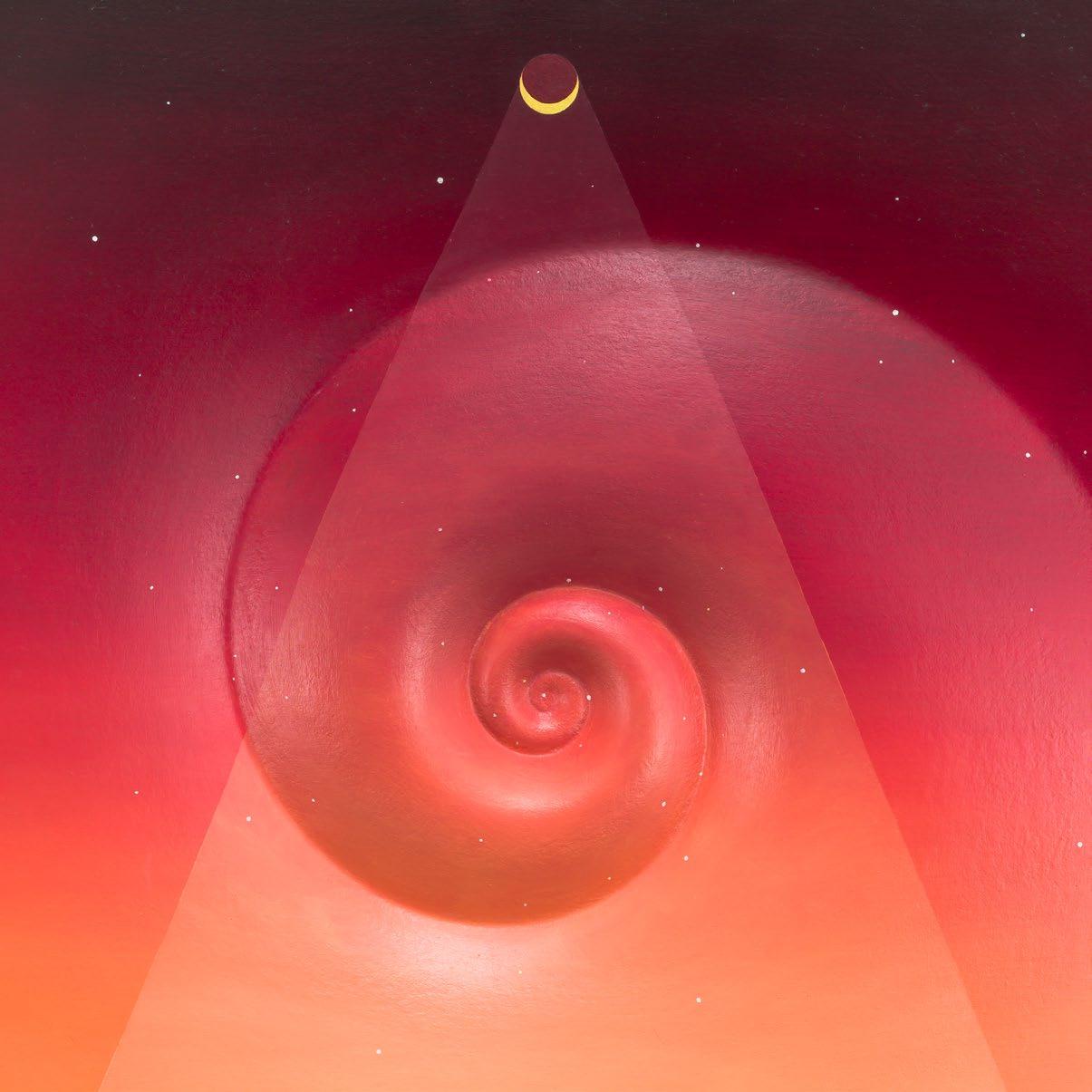

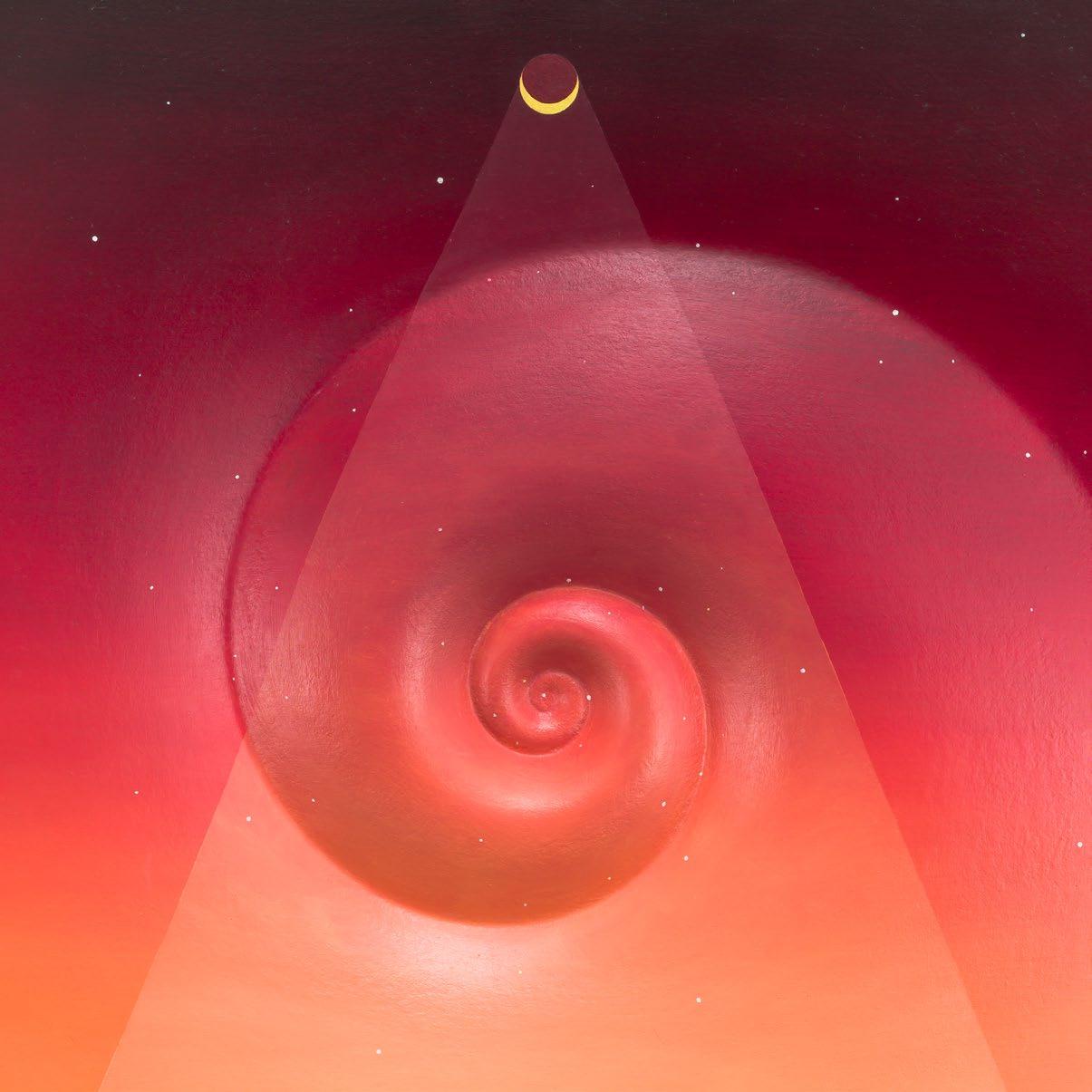

There is a balance in these works between cosmic suggestion and comedy. The latter peeks out through the sidelong presence of certain forms. Let’s look at Guidance (2025). Here, we’re hit smack in the face by a range of oranges, which suggest a deranged Alejandro Jodorowsky scene. The image’s centrifugal point is a black keyhole shape. This might be the ghost of René Magritte. But it could also just be a keyhole—end of story. In any case, the work is painted on medium-density fiberboard (MDF), which has been shaped to mimic a swelling spiral, with the keyhole resting upon the largest and lowest bulge in that formation. This swelling also calls to mind figures from medieval painting— those wide-eyed saints whose bodies register no division between the divine and the cartoonish.

Several years ago, I was lucky enough to witness a moment in which Emily’s practice took important steps toward its current form. We were deep in the Canadian Rockies, where we were artists in residence.1 We were taking long hikes through the mountain ranges and doing readings on mimesis: that strange process of identification, through which one thing comes to be understood, or comes to understand itself, in the form of another, and in doing so unlocks hidden powers. The magic of studying that material in that overwhelming place, continues to smoulder in Emily’s paintings. Another word

1 The residency, which took place at The Banff Center, was led by Silke Otto-Knapp and Jan Verwoert and was called “A Paper, A Drawing, A Mountain.” These discussions were a direct result of our residency seminars.

for that smouldering is studio work, which is also devotional, in that it bridges immersed focus and a wonder-driven relationship to the world and its meanings.

That line of inquiry has led to a perception of signifiers as innate shape-shifters. Were people to close their eyes and imagine the works in this exhibition playing out as a film montage, they would witness bits and pieces of the painter’s vocabulary morphing, as these things always do in our minds.

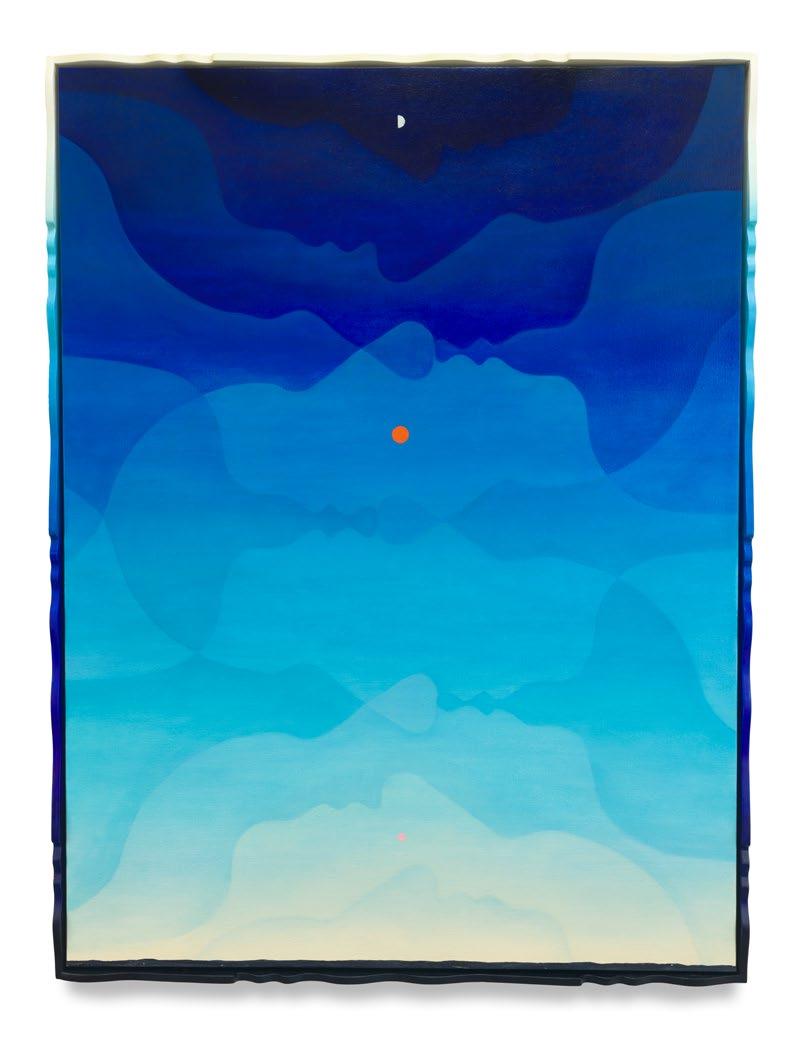

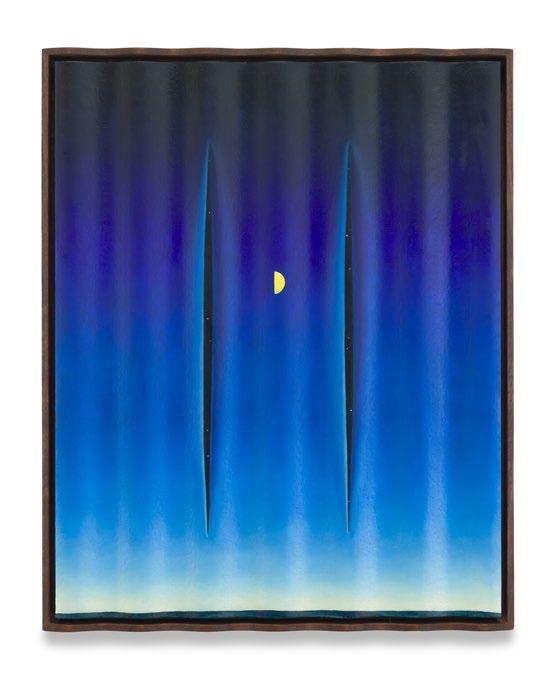

Double Slit (2025), for example, finds a royal blue plane cut twice along its vertical axis. Lucio Fontana’s sliced canvases come quickly to mind. It is the context provided by the painting’s broader compositional and physical structure that animates this play of signs, that gives it life as a theater of the mind. Along Double Slit ’s top edge, color darkens, as if the sky is turning into squid ink; down below, the opposite occurs, as blue becomes yellow-white. Again, a crescent moon hovers.

Just as the violin and the guitar—which makes a full-form cameo in Magnifier (2024)—are built for vibration, these paintings are built to convey the same. Interference (2025) has two focal points on the picture’s central vertical axis. Each forms the center of a raised ripple formation. It’s as if two small stones had been plunked into the picture plane. The ripples disturb a crepuscular sky, framed by rising specter hands. The latter are as much signals of divinity as they are reusable compositional elements: They are cousins, maybe, of the cutout shapes that Henri Matisse rearranged from painting to painting or the serialized human figures in Auguste Rodin’s Gates of Hell .

Lately, Weiner has been producing formed supports for her paintings in collaboration with the woodworker Ari Kardasis, whose role is to transfer her shapes into mathematical formulas, which are then executed by a CNC router. This process brings old-style guild work into the digital present. It gives us paintings that bring instruments to mind, underlining the physicality of sound.

Custom frames, made through the same collaborative process, become active thresholds between interior and exterior space. Often shaped into rhythmic, wave-like contours, they metabolize the energy of their respective images. Their shapes give tactile form to the virtual tremors of the surface

and underline the kinship of those forms with everything inside or outside of the frame. The wave, after all, is a structure that touches every scale of experience—from the visible vibrations of a struck drumhead to the invisible frequencies that structure our lives. The frames, then, act as a relay between distinct and overlapping realities: the interior world of sign and sensation, and the ambient real world, which is equally governed by vibrating systems. These frames tend toward one of painting’s oldest dialectical tensions—drawing a boundary around illusion and perforating it.

In this way, too, Emily’s work enters into an old, maybe theological, conversation about image-making. Like the carved frames of Renaissance altarpieces or Byzantine icons, her frames are handmade, tailored, and insistently object-like. But while premodern frames anchored devotional narratives, these frames converse with modernism’s self-conscious formalism.

Gone is the directive to make myths. In its place, there is a rich grammar of forms—spheres, spirals, motifs cribbed from astrological and alchemical vocabularies—that seem more interested in tuning the picture’s rhythm than transmitting doctrine. In certain cases, the form recedes into an even more radical modernism. The result is a kind of proto-symbolic abstraction. Snake (2025), a near monochrome of choral pink, is a case in point.

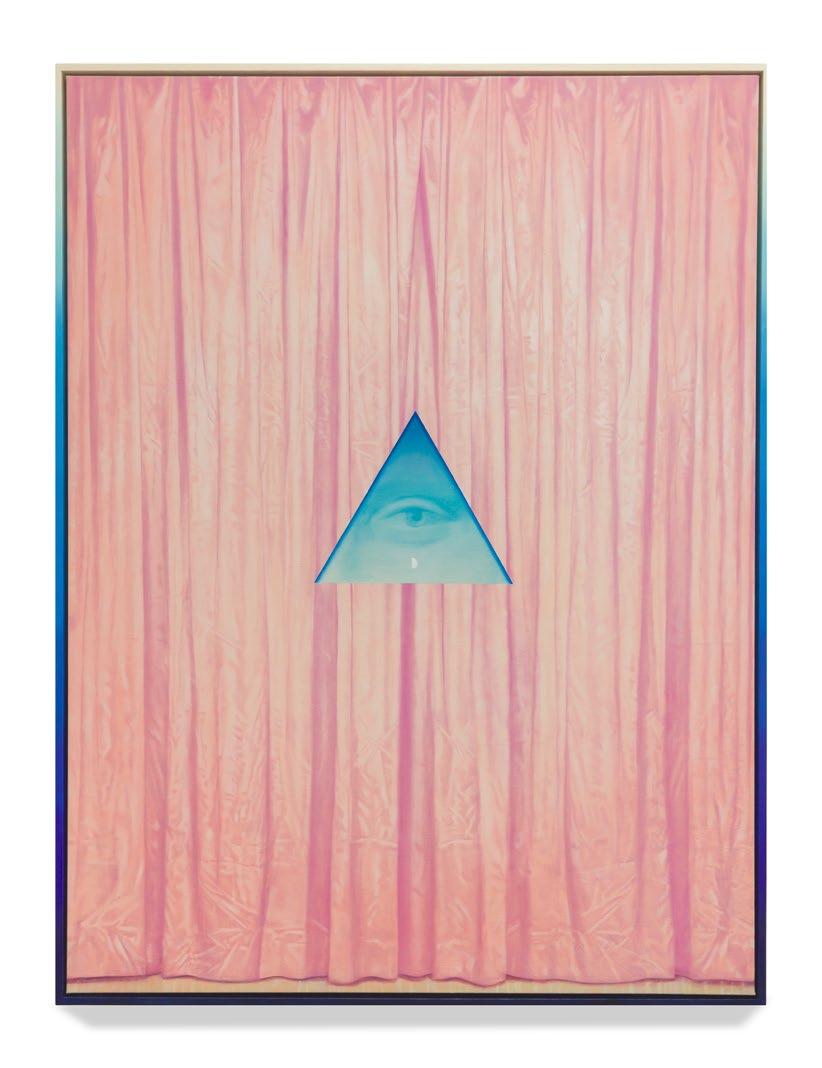

In Marionettist (2025), carmine drapes fall symmetrically along either side of the frame. They are unmistakably fabric. At the same time, given their exacting execution, they seem like simulations. From behind these curtains, those ghostly hands reemerge. Again, their pose recalls a medieval blessing, even as both the title and the composition suggest puppetry. Questions come to mind: What is being performed here? Who is pulling the strings? In place of an answer, we get a silent aria.

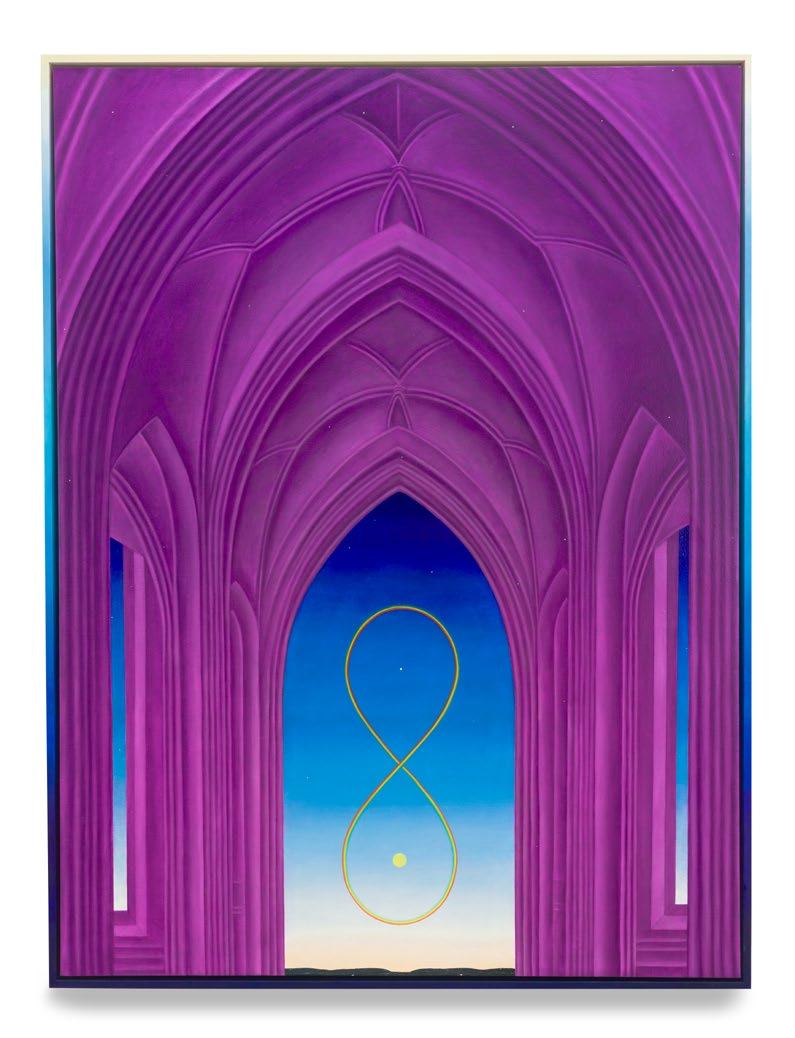

If precision forms the magnetic charge of these paintings, it is surreal dissonance that makes the magnetic attraction last. Passing Through (2025) presents the interior of a cathedral, its surface the color of electric grape juice. Gothic arches, pictured from a low interior perspective, recede into the distance. Instead of leading toward an altar, the structure opens onto sky. The light is post-sunset.

de

canvas, 42 x 37 inches

of the

x 94 cm). Tate Modern, London, United Kingdom, Purchased with assistance from the Art Fund (Eugene Cremetti Fund), the Carroll Donner Bequest, the Friends of the Tate Gallery and members of the public 1985.

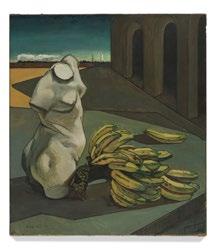

Giorgio de Chirico comes to mind, and right behind him some unnamed fresco painter gone rogue, turning from gospel toward a freer, chromatic liturgy. The space is devotional, but its subject is pure color.

It would seem a miscalculation, here, to make a distinction between irony and reverence. Liturgical architectures and motifs are made strange, in these paintings, with humour accentuating religiosity. Even the most canonical references are re-encoded, altered through shifts in scale, placement, or texture. In the same breath, Emily’s pictures hold this gravity, and wit.

Mitch Speed is a Berlin-based writer, whose criticism has appeared in Frieze, Camera Austria, Momus, Artforum, ArtReview, Mousse, Spike, amongst other publications. In 2019 his study of Mark Leckey’s video artwork Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore (1999) was published by Afterall Books, as part of their One Work series. His recent essay collection Closeness Eats Time was published in 2025, by Brick Press, and his next book is forthcoming from Floating Opera Press.

24 x 22 x 1 1/2 inches

61 x 56 x 4 cm

61 1/2 x 46 1/2 x 2 inches

156 x 118 x 5 cm

14 x 11 x 1 3/4 inches

36 x 28 x 4 cm

21 x 17 x 1 3/4 inches

53 x 43 x 4 cm

Emergence, 2025

Oil on linen in painted wood frame

50 1/4 x 36 1/4 inches

128 x 92 x 4 cm

Excavation, 2025

Oil on linen in painted wood frame

61 1/2 x 46 1/2 x 1 1/2 inches

156 x 118 x 4 cm

61 1/2 x 46 1/2 x 1 1/2 inches

156 x 118 x 4 cm

Guidance, 2025

Oil on shaped MDF in walnut frame

21 x 17 x 1 3/4 inches

53 x 43 x 4 cm

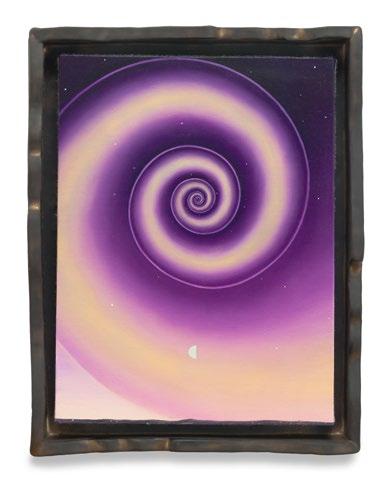

Interference, 2025

Oil on shaped MDF in walnut frame

21 x 17 x 1 3/4 inches

53 x 43 x 4 cm

Magician’s Assistant, 2025

12 x 10 3/8 x 1 1/2 inches

31 x 26 x 4 cm

Marionettist, 2025

Oil on linen in painted wood frame

61 1/2 x 46 1/2 x 2 inches

156 x 118 x 5 cm

Passing Through, 2025

61 1/2 x 46 1/2 x 2 inches

156 x 118 x 5 cm

Resonance, 2025

Oil on linen in painted wood frame

35 x 29 x 1 1/2 inches

89 x 74 x 4 cm

12 x 10 x 1 1/2 inches

31 x 25 x 4 cm

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

NOW EVE, WE’RE HERE, WE’VE WON

26 June – 15 August 2025

Miles McEnery Gallery

511 West 22nd Street

New York NY 10011

tel +1 212 445 0051 www.milesmcenery.com

Publication © 2025 Miles McEnery Gallery

All rights reserved

Essay © 2025 Mitch Speed

Photo Credits

p. 7: © Public Domain

p. 7: © 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome / © DACS, Photo: Tate

Associate Director

Julia Schlank, New York, NY

Photography by

John Schweikert Photography

Jessie Watts Photos

Catalogue layout by Allison Leung

ISBN: 979-8-3507-5009-6

Cover: Ad Infinitum, (detail), 2025