VERTICAL COALESCENCE

A MIXED-USE AFFORDABLE HOUSING SOLUTION FOR CHICAGO, ILLINOIS

AINSLEY LUDEMA

VERTICAL COALESCENCE

A MIXED-USE AFFORDABLE HOUSING SOLUTION FOR CHICAGO, ILLINOIS

AINSLEY LUDEMA | BALL STATE UNIVERSITY

I extend my deepest gratitude to my studio professor, Sarah Keogh, and my diploma project advisor, Miguel San Miguel, whose guidance and expertise have been invaluable throughout this journey. Your thoughtful critiques and unwavering encouragement have shaped not only this thesis but also my growth as a designer.

To my family, I owe endless thanks for your unwavering support and belief in me, which have carried me through the challenges of my education and the beginnings of my career.

Finally, to my friends and peers, thank you for your inspiration and countless conversations that have made this five-year journey all the more meaningful. Your support has been a constant source of motivation, and I am truly grateful.

I cannot thank you all enough.

CONTENTS

9

& PRECEDENTS 43

DESIGN 77 DESIGN DEVELOPMENT

CONCLUSIONS & REFLECTIONS

ABSTRACT

This thesis explores how a high-rise residential model can function as a vertical city, embedding community, wellness, and ecological aspects into its design. It prioritizes affordability and shared spaces in neighborhoods that span the vertical structure, challenging conventional notions of high-rise hierarchies. This thesis seeks to create a more humane residential model in which essential daily needs are seamlessly integrated throughout the building, reinforcing the idea that high-rise housing can function as a self-sustaining community.

Situated in downtown Chicago, this design demonstrates how high-density housing can be restructured to better support human needs, providing a more enriching framework for future urban living. Groups of residential units encourage communal living and strengthen the sense of community with shared kitchens and dining areas. Ecological strategies including light wells, wind chambers, green spaces, and rainwater collection are embedded within the design, enhancing both environmental performance and occupant well-being. By redefining the highrise as a vertical city, this thesis challenges outdated residential models, demonstrating how affordable urban housing can foster both environmental responsibility and a stronger sense of community.

INTRODUCTION

FIGURE 1.1: Diagram by Author. Created using Adobe Illustrator.

Vertical Coalescence

FIGURE 1.2: Diagram by Author. Created using Adobe Photoshop & Illustrator.

QUESTION

How can prioritizing inclusion and emotional well-being in vertical architectural design foster a harmonious community that integrates both human and non-human environments?

THESIS

By applying environmental design principles to vertical urban relationships, buildings can promote inclusive, emotionally supportive communities that encourage engagement with natural features and ecological processes.

STATEMENT

This project evaluates this thesis through the design of a mixeduse residential complex targeting households who currently find downtown Chicago unaffordable. Vertical Coalescence addresses the area’s high median contract rent and lack of after-office vibrancy by creating affordable housing options that attract and retain residents.

INSPIRATIONS

COPENHAGEN community-centric, sustainable urban housing

MADRID urban greening initiatives mitigating urban heat island effects

DUBAI pioneering highperformance skyscrapers in extreme climates

SAO PAULO environmental design in a sprawling, high-density city

FIGURE 1.3: Diagram by Author. Created using Adobe Illustrator.

Vertical Coalescence

HELSINKI

energy-efficient building design and integration of nature into the cold urban environment

TOKYO compact, efficient, and socially responsive urban living environments

SINGAPORE global leader in the integration of biophilic design principles with dense urban areas

MELBOURNE proactive climate adaptation through green infrastructure and urban cooling initiatives

FIGURE 1.4: Diagram by Author. Created using Adobe Illustrator.

Vertical Coalescence

The contemporary urban landscape presents a critical opportunity to mitigate rising social and ecological challenges through thoughtful design. As cities such as Chicago, Illinois evolve under environmental pressures, the role of architecture becomes vital in prioritizing occupant well-being within the built environment.

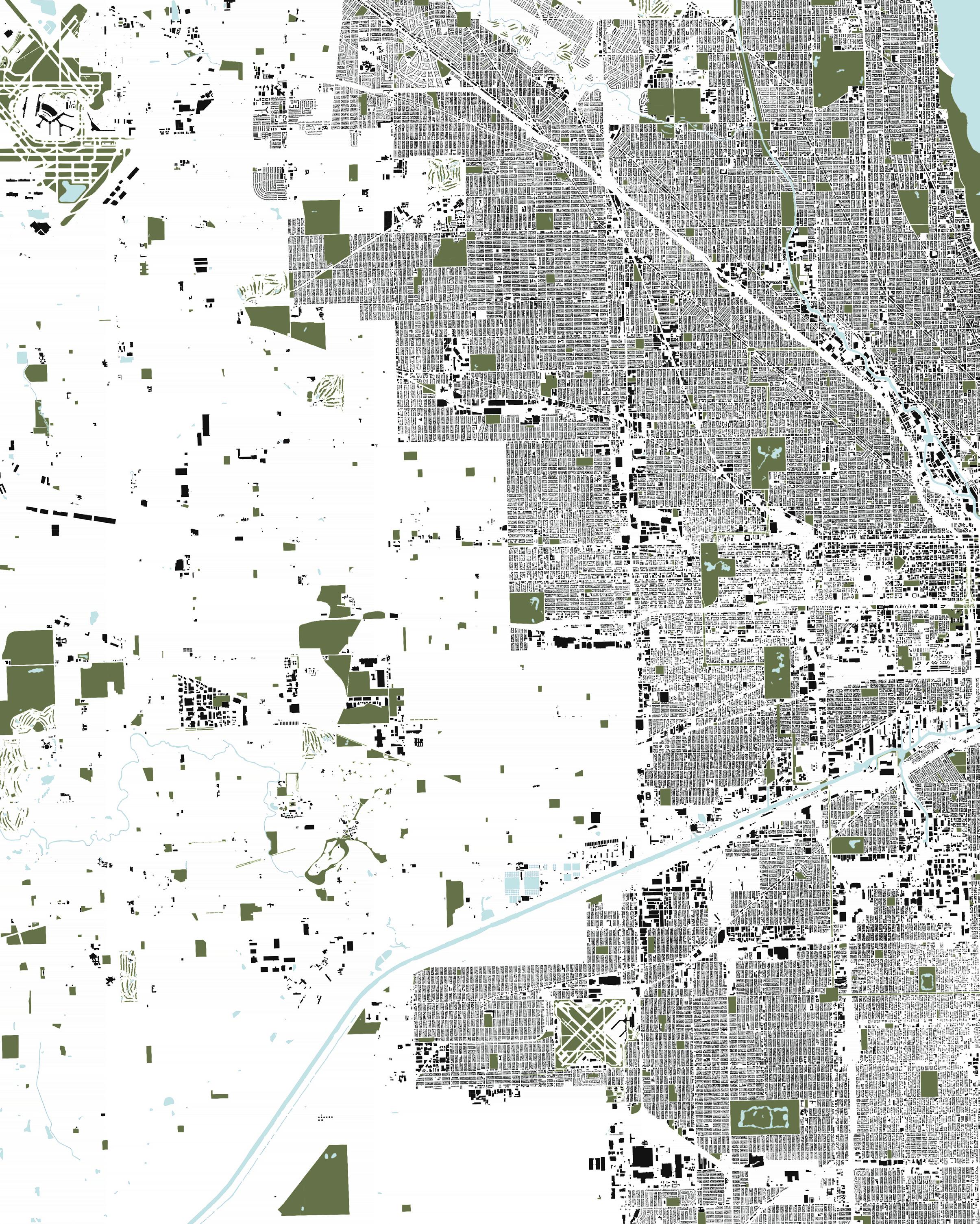

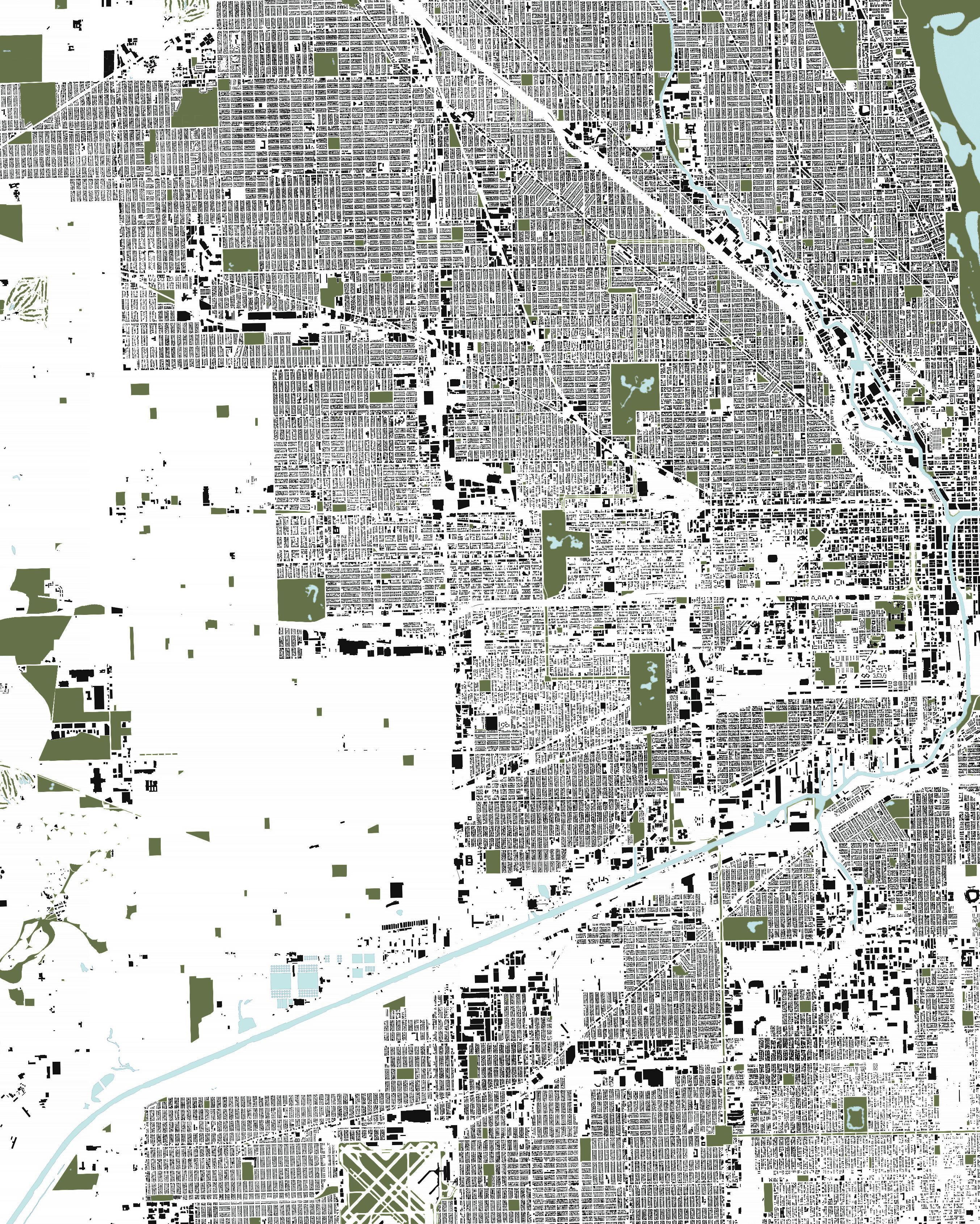

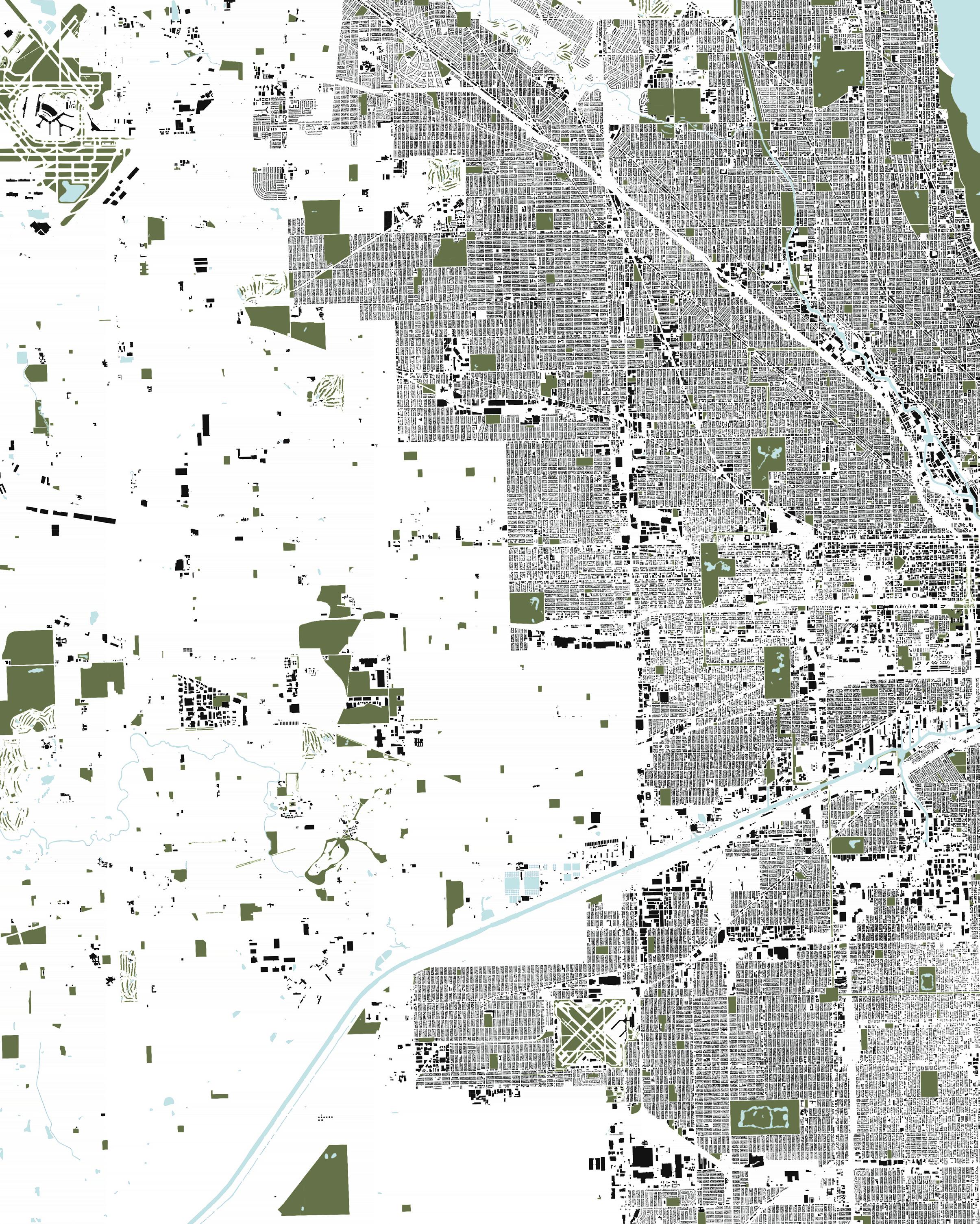

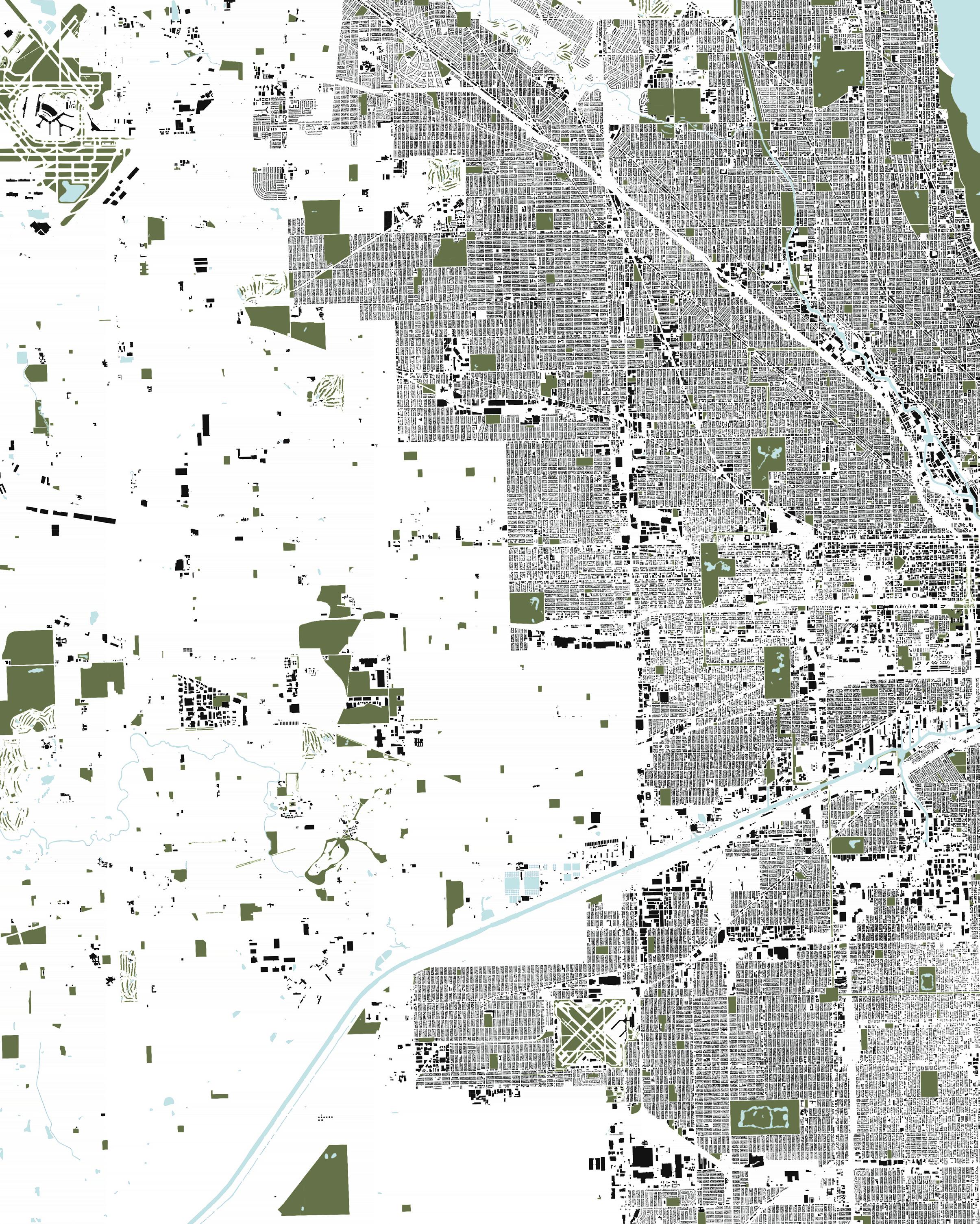

The site for this project is located in downtown Chicago at the intersection of East Van Buren Street and South Wabash Avenue. This area is filled with vacant office spaces and expensive apartment prices, making it inaccessible for college graduates to live in. This inaccessibility results in a large number of commuters by train and/or bus who work in the downtown area and leave the area vacant after office hours. Through an exploration of both income levels throughout Chicago and apartment pricing rates, this project, in the form of a mixed-use high-rise building, will examine an affordable housing solution for this downtown vacancy. The final architectural project will prioritize inclusion and emotional well-being in an environmentally-conscious design that aims to foster a harmonious community in downtown Chicago.

By analyzing the work of design professionals and precedent studies, this research aims to establish a holistic approach that balances the creation of equitable, community-focused living environments with environmental performance. The resulting project seeks to push the boundaries of the environmental

design of a mixed-use high-rise building, offering a blueprint for resilient and human-centered urban development. By applying environmental design principles to vertical urban relationships, this design will promote inclusive, emotionally supportive environments that encourage engagement with natural features and ecological processes.

This project resonates with me because I plan to explore these topics thoroughly throughout my career as an architect. I have had experience working in both an international architecture firm specializing in biophilic design and a firm in Chicago that specializes in designing for underserved communities. Each of these experiences has informed my ambition for architectural design, and I aim to explore these passions through this project. This design will address current issues in Chicago, including its lack of public green roofs and the absence of culture and after-office-hours excitement in the downtown area.

The target clientele for this design are people aged 25-35 who are not currently able to afford living in downtown Chicago. Access to affordable housing in Chicago’s downtown could revitalize the area by drawing younger residents and creating a more vibrant after-office-hours environment. This project aims to provide a framework for environmental, affordable living in Chicago. This information will be shared both in a verbal presentation (April 2025) and online for public reference.

FIGURE 1.5: Diagram by Author. Created using Adobe Illustrator.

Vertical Coalescence

THE CHICAGOAN ROUTINE

The everyday existence of Chicagoans unfolds in a seamless flow following the city's nine-to-five rhythm. A typical day begins on Chicago’s train lines, where commuters pack into cars and navigate their way to work. They emerge from the trains and step into streets alive with movement as they finish their commute to high-rise offices on foot.

For lunch break, office workers seek out local restaurants for a quick bite or gather along the river to catch a moment of sunlight. These routines are punctuated by errands and coffee breaks. As the workday ends, they return to their neighborhoods, leaving the downtown quiet and void of people.

This familiar pattern can be challenged and improved upon by reimagining the downtown residential structure not as an isolated housing block, but as a more integrated community. By incorporating green spaces vertically and weaving shared amenities throughout, the urban residential complex can encourage continuous use beyond the 9–5 window.

This solution creates opportunities for residents to live, work, and socialize in the same environment, bringing life back to the city’s core after business hours and offering a more balanced, accessible, and humane urban lifestyle.

FIGURE 1.6: Diagram by Author. Created using Adobe Illustrator.

Vertical Coalescence

$90,000 INCOME

$100,000 INCOME

MEDIAN HOUSEHOLD INCOME

For many young residents, this cyclical existence is limited by the barrier of affordability. Living beyond the city’s core necessitates longer commutes and reduced access to the vibrancy of downtown. By fostering affordable housing opportunities within the heart of Chicago, this dynamic could be transformed. Younger residents may find themselves more deeply integrated into the urban fabric, their daily routines enriched by shorter commutes and increased opportunities to engage with the city’s cultural and social offerings.

Uplifting this experience requires a combination of reducing economic barriers and designing spaces that align with their aspirations—housing that combines accessibility with community, enabling residents to find both convenience and connection within the pulse of the city. In this way, the everyday journey through Chicago’s downtown can evolve from a functional routine into an inspired way of life, reinforcing the city’s role as a hub for innovation and inclusivity.

FIGURE 1.7: Diagram by Author. Created using Adobe Illustrator.

Vertical Coalescence

MILLENIUM PARK

tourist destination

programmed events

few spontaneous uses

GRANT PARK

PRITZKER PARK

designed for large festivals limited neighborhood-scale use underutilized poorly maintained unwelcoming

LOCAL GREEN SPACES

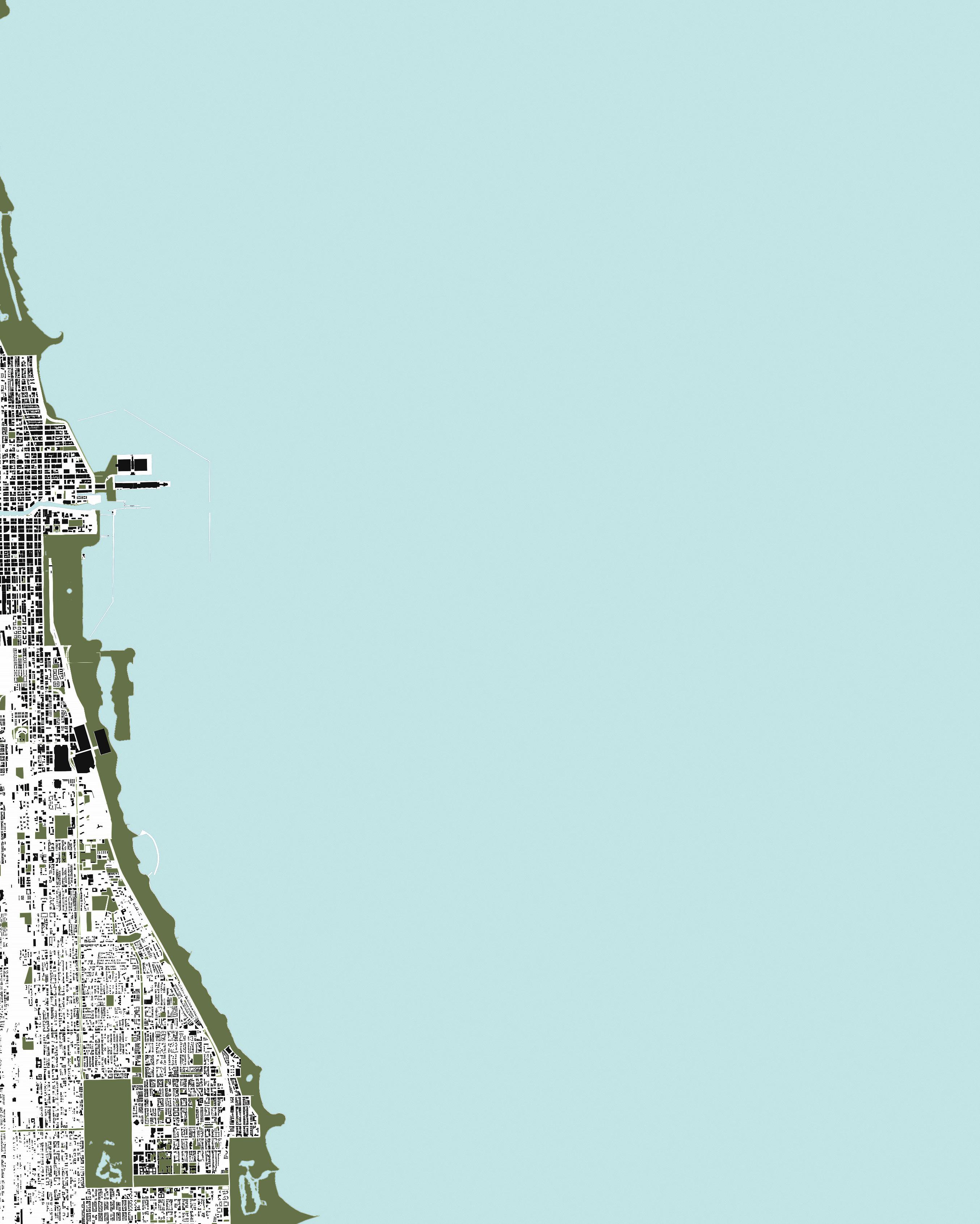

This map shows the site in relation to three well-known parks located nearby— Millennium Park, Grant Park, and Pritzker Park. While this might seem like an abundance of green space, Millennium and Grant Park primarily serve tourists and city-wide events. Millennium and Grant Park are beautiful, but they’re not the kinds of places locals casually stop by on a daily basis. Although Pritzker Park is smaller and more approachable, it is often poorly maintained and uninviting.

What’s missing here is local green space. Downtown Chicago lacks small, accessible parks designed for everyday use by people who live or work downtown.

FIGURE 1.8: Diagram by Author. Created using Adobe Illustrator.

Vertical Coalescence

SITE CONTEXT

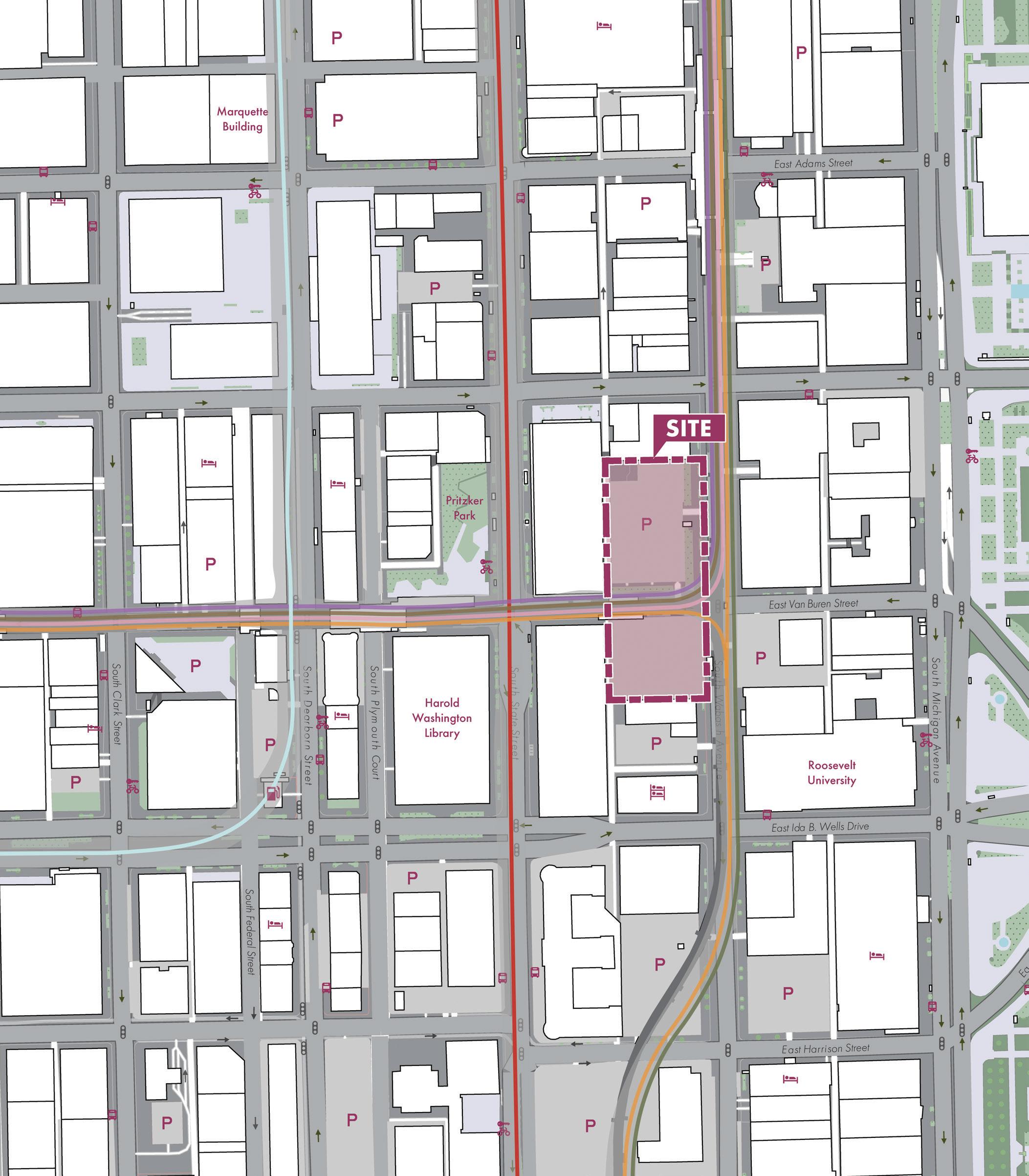

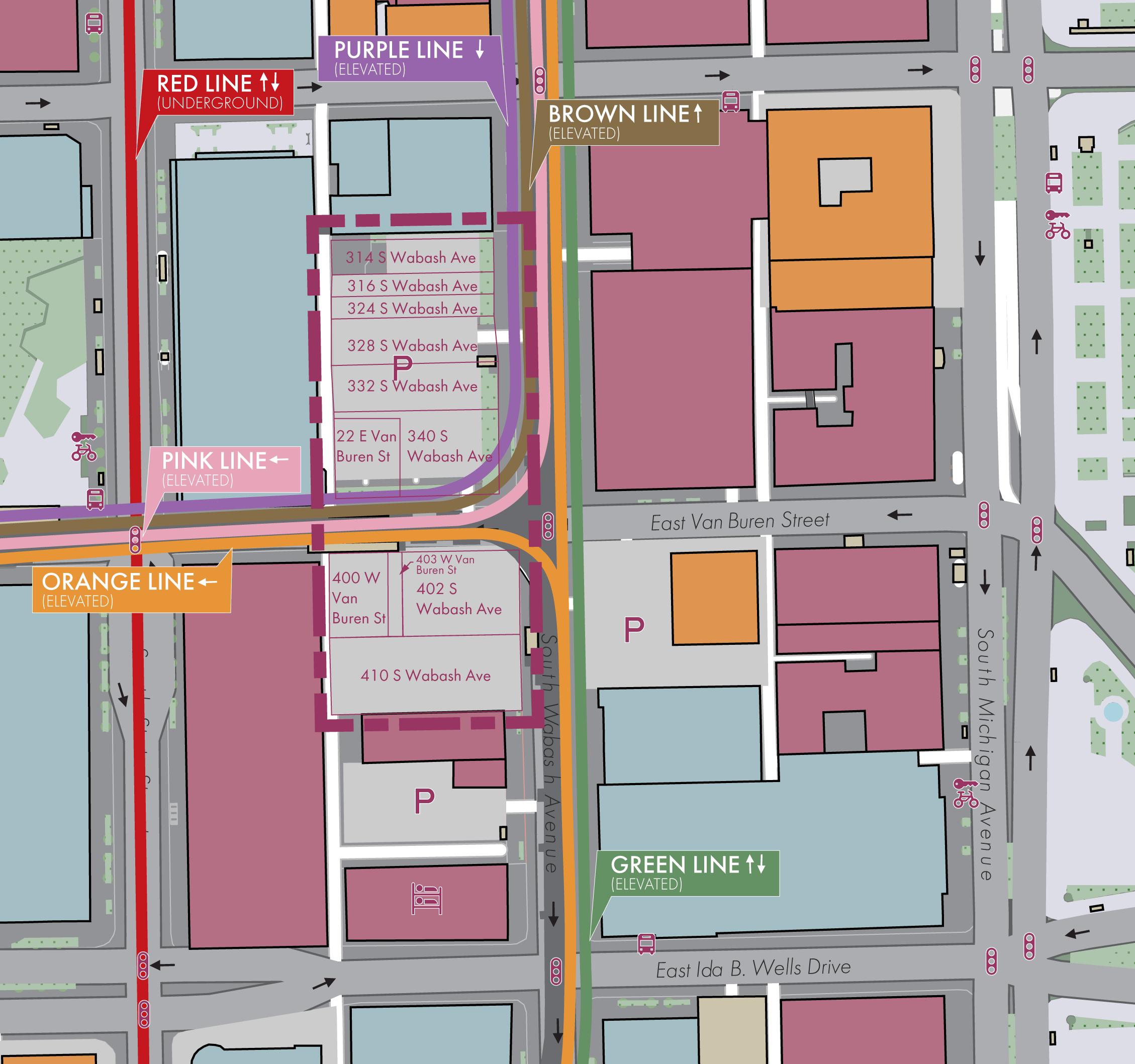

This site is in downtown Chicago, at the intersection of East Van Buren Street and South Wabash Avenue. This portion of the city is very dense, although the site is located a block west of Grant Park, which borders Lake Michigan. Green space decreases significantly as building density increases outside of Grant Park. The site is near the famous Harold Washington Library, as well as Roosevelt University and the Art Institute of Chicago. The majority of the surrounding structures are of commercial or institutional use.

People here navigate the city using a combination of bike, bus, and train. The site is located on either side of the elevated CTA train tracks, specifically the purple, brown, pink, and orange lines, which travel throughout the entire city and its suburbs. The green and red lines run adjacent to the site. All of these trains are accessible from stops located 2-3 blocks away. Noise levels originate primarily from the elevated train tracks and nearby intersections.

HAROLD WASHINGTON LIBRARY

PRITZKER PARK

ELEVATED TRAIN TRACKS

SITE

FIGURE 1.9: Diagram by Author. Created using Adobe Illustrator.

Vertical Coalescence

SITE CONTEXT

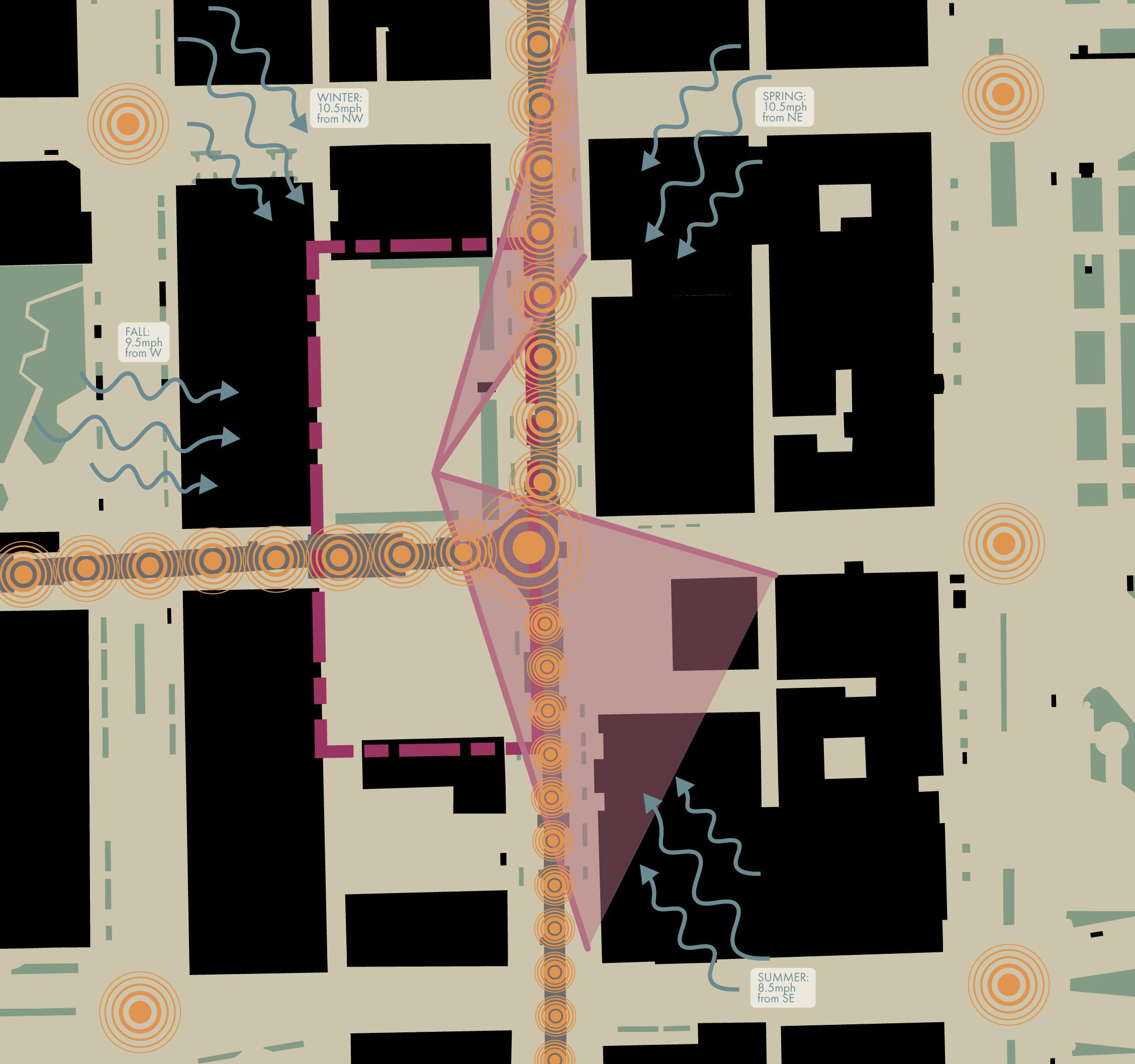

Desireable views, combined with daylighting opportunities, will orient the structure’s glazing on each level. Noise from the adjacent elevated train tracks will need to be accounted for through a strategic building envelope. Seasonal wind directions present opportunities for passive cooling during certain months of the year. A lack of surrounding permeable surfaces supports the future integration of ecological features. The resulting environmental high-rise will consider all of these aspects in a solution that best responds to its surrounding environment.

GRANT PARK

SITE ANALYSIS: LAND USE & TRANSPORTATION

Vertical Coalescence

FIGURE 1.10: Diagram by Author. Created using Adobe Illustrator.

SITE ANALYSIS: WIND, NOISE, VIEWS, & PERMEABILITY

FIGURE 1.11: Diagram by Author. Created using Adobe Illustrator.

SITE NARRATIVE & DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS

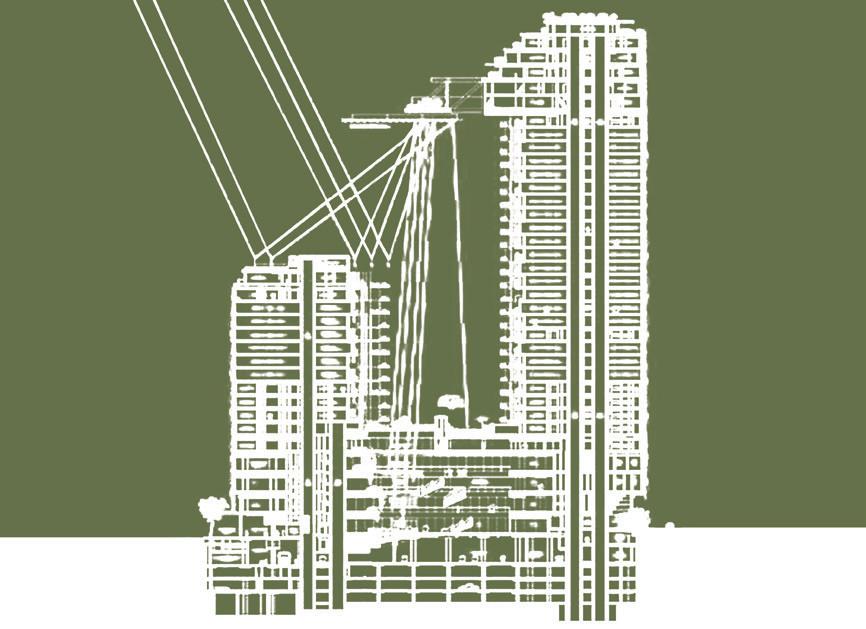

FIGURE 1.12: Diagram by Author. Created using Rhino & Adobe Illustrator.

Vertical Coalescence

RESEARCH & PRECEDENTS

ISSUES

OF

METRICS, EFFICIENCIES & RESILIENCIES

In response to rising environmental pressures, designing buildings that integrate sustainable strategies becomes increasingly crucial. By considering spatial context and a holistic assessment framework, this research seeks to establish how design decisions may enhance energy efficiency, reduce reliance on active systems, and promote human well-being. These metrics ensure that environmental design achieves long-term sustainability goals within urban landscapes and strengthens the connection between people and nature. This research will provide a method to evaluate passive systems and materials that can optimize the performance of a high-rise building, aiming for net-zero energy consumption while maintaining resilience and efficiency throughout its lifespan.

Effective environmental design in the urban setting requires an analysis of passive cooling strategies and how they interconnect. This holistic, multilevel approach strengthens relationships between people and nature while emphasizing maximum energy efficiency. Cheshmehzangi’s SWOT analysis provides guidance on which passive cooling systems to explore further and how they may account for each other’s strengths and weaknesses across various scales. The environmental design of a mixed-use high rise in Chicago, Illinois requires a site-specific synergistic approach to lessen dependency on active

energy systems over extended periods. Select precedents work alongside this research to inform the design of resilient, energy-efficient buildings. The findings will integrate to develop a comprehensive understanding of sustainable architecture. In the design for Menara Mesiniaga in Petaling Jaya, Malaysia, T.R. Hamzah and Yeang conducted an in-depth analysis of passive cooling strategies and their long-lasting beneficial impact on the surrounding environment and the structure itself. This design incorporates various ecological features, including vegetated ramps, terraces, and vertical landscaping, to benefit user experience and allow opportunities for interaction with nature throughout the structure. Menara Mesiniaga expands upon this biophilic design by using the stack effect for passive cooling, allowing warm air to pass through the structure’s sky courts, vegetation, and shading devices as the air is cooled (see Figure 2.1). The cool air flows throughout the structure, interacting with the internal cooling system and allowing the building’s core, located adjacent to the exterior, to be

1. Ali Cheshmehzangi and Ayotunde Dawodu, “Passive Cooling Energy Systems: Holistic SWOT Analyses for Achieving Urban Sustainability,” International Journal of Sustainable Energy 39, no. 9 (2020): 823, GreenFILE.

Vertical Coalescence

FIGURE 2.1: Diagram by T.R. Hamzah & Yeang 1992, edited by author using Adobe Photoshop. Downloaded from https://www.archdaily.com, accessed August 2024.

completely free of active systems. Passive ventilation maximizes efficiency by allowing systems to focus on consistently inhabited areas. The design strategically places two sizes of sun-shading devices to maximize daylighting effects. Thinner louvers are positioned closer to the building's facade, allowing wind to pass through, while thicker louvers are set farther away to provide shade for larger areas as needed. This research on passive ventilation strategies is beneficial to the design of an environmental high-rise building through the study of how to use wind as a passive cooling method and maximize its efficiency. The careful incorporation of daylighting through a series of solar studies will be advantageous, as shown through T.R. Hamzah and Yeang’s thorough research for Menara Mesiniaga. These studies will work to reduce the use of active systems whenever possible and assist the project in pursuing net-zero energy goals.

The Academy for Global Citizenship, designed by SMNG A Ltd. and Farr Associates in Chicago, Illinois, expands upon this research by incorporating hightech sustainable features within a six-acre learning, wellness, and sustainability hub. Its program includes a K-8 public charter school, early childhood education center, community produce market, health center, and a café. The Academy for Global Citizenship incorporates over 500 kW of solar panels, 50 geothermal wells, grey water catchment, and natural water purification, all of which helped it become the 25th project in the world to achieve

a Living Building Challenge certification. This intensive guideline for sustainable design requires designers to consider wellness features alongside ecological metrics. The project addresses these strict parameters through a sustainable vegetable farm, nature pathways, and community gardens spread across the campus (see Figure 2.2).

FIGURE 2.2: Diagram by Author. Created using Adobe Photoshop.

ENVIRONMENTAL DESIGN ISSUES

By examining innovative design techniques at the intersection of environmental design and social dynamics, this research aims to understand how environmental features can improve mental well-being and foster social interactions among occupants. Thoughtful integration of natural elements and social spaces can uplift users’ experiences and create a supportive sense of community, as displayed by the design strategies of successful projects by Ateliers Jean Nouvel and PLP Architecture. This focus on the overlaps of nature and socialization is crucial for a project that seeks to meet sustainable goals while prioritizing its occupants' social engagement.

In “Environment in Buildings Series-3: Architecture and Psychology,” Canter explores the revolution and intertwinement of architecture and psychology as ‘environmental psychology’ and ‘architectural psychology. He explains that this new discipline “deals with architectural or environmental variables, things which the people who build and design our environment must manipulate; on the other hand, it deals with psychological behavior, people's thoughts, feelings, and actions.” 2 This intersection between two distinct fields analyzes how interactions with the built environment influence human behavior and emotion through various study methods. Canter describes several studies that examine the relationship

between factors such as room shape or noise levels on behavior patterns and levels of occupant comfort. He describes a study by Robert Sommer that focused on optimal distances between seating areas and how people chose to congregate based on various distances between sofas. Canter’s explanations of various stimuli, such as light, temperature, and noise levels, reveal how architects may promote well-being from a psychological perspective. He concludes that, while these findings are proving beneficial when designing spaces for various purposes, more specific research development is needed to outline a series of specific formulations to tackle specific existing and future design problems.

Successful design must aim to uplift user experience. A design focusing on human comfort necessitates a complete understanding of how people navigate space and interact with one another based on environmental conditions. Considering how natural and artificial elements affect occupant mood, productivity, and behavioral patterns will impact this project throughout all design phases. Natural stimuli such as greenery, natural light, and open-air features may positively affect users' behavioral patterns if incorporated meaningfully. The built environment immensely impacts how people use space and feel within it.

In “How Green Facades Affect the Perception of Urban Ambiences: Comparing Slovenia and the

2. David Canter, “Environment in Buildings Series-3: Architecture and Psychology,” Built Environment 1, no. 3 (1972): 188, JSTOR.

Netherlands,” Kozamernik explores the impact of green facades on urban environments, specifically in temperate climates, through a comparative study between Slovenian and Dutch residents. The study assesses both the public and architecture and urban planning students through an online survey and reveals that, in general, people perceive greener urban environments as more pleasant. While overarching differences are found between age groups and between countries, denser greenery is decidedly preferred. Kozamernik compares varying amounts of vertical greenery systems and how humans perceive them, concluding that when an appealing environment surrounds people, they are drawn to it and encouraged to spend more time there. She writes that “one of the key findings is the importance of not only the presence, but also the amount of vegetation in the urban context. Based on the results it can be concluded that the public opinion favors a larger share of vegetation in the urban environment.” 3

This research demonstrates how urban aesthetics are enhanced significantly by using green facades. Green spaces are preferred for group activity, encouraging occupants to enhance their connection to nature and experience improved wellbeing. This research will benefit the design of an environmental high-rise aiming to incorporate green elements, such as facades, living walls, and planters, to enhance a sense of community within social settings.

One Central Park in Chippendale, Australia, was designed by Ateliers Jean Nouvel with significant environmental ambitions. This project benefits occupant well-being through access to and views of natural elements. The design incorporates strategically placed vertical plantings on the exterior of the building. This greenerycovered façade allows natural light to fill interior spaces and encourages people to gather in the bright, comfortable spaces within. One Central Park incorporates an innovative system of 320 reflective mirror panels on a cantilever to address shading issues and improve natural lighting on the structure's interior and exterior (see Figure 2.3).

One Central Park provides an inspiring study of vertical greenery and an innovative solution for inadequate daylighting. These findings confirm that by incorporating natural elements such as green facades and working to optimize social spaces, the high-rise design can achieve its goals of sustainability while fostering a vibrant community.

3. Jana Kozamernik, Martin Rakusa, and Matej Niksic, “How Green Facades Affect the Perception of Urban Ambiences: Comparing Slovenia and the Netherlands,” Urbani Izziv 31, no. 2 (2020): 98, JSTOR.

FIGURE 2.3: Diagram by Ateliers Jean Nouvel September 2014, edited by author using Adobe Photoshop. Downloaded from https://www.archdaily.com, accessed September 2024.

SOCIAL & CULTURAL ISSUES

This section explores the intersection of social and cultural issues within the design process, focusing on how architecture can foster community-based relationships and promote equity. By examining affordable housing models, this research investigates how intentional socialization spaces can improve occupant well-being and encourage inclusivity. Adaptable communal environments that address the challenges of limited living space prove successful when privacy and interaction are balanced. This exploration informs the environmental design strategies of a high-rise by emphasizing how design elements can encourage shared experiences among residents. As users feel a sense of belonging, the social and physical health of the entire community is enhanced, reinforcing a positive cycle of social equity and well-being.

Terry Peterson applies this exploration of social and cultural issues in “A Vision for Change” by analyzing the Chicago Housing Authority's Plan for Transformation. He explains how the ten-year initiative to overhaul Chicago's public housing system aims to replace old structures with mixed-income communities to introduce more low-income families into the broader urban fabric, focusing on ending the cycle of concentrated poverty and social isolation. The plan's core goals include transforming isolated lowincome developments into mixed-income

communities. Peterson explains the plan as “a blueprint to overhaul the physical structures as well as the mindset surrounding public housing.” 4 This framework ensures equal access to public services across all income levels, provides comprehensive public healthcare and career training, and addresses the systemic barriers that hinder impoverished communities from achieving self-sufficiency.

Peterson advocates for the Chicago Housing Authority’s Plan for Transformation and is confident that the plan will transform public housing into inclusive neighborhoods. The environmental design of a mixed-use high-rise in Chicago must consider this plan and address current social issues affiliated with access to affordable housing communities in the area. Creating equitable and accessible housing solutions for underserved communities in Chicago is incredibly important. This project will explore the process of designing for underserved and underprivileged communities to establish equitable, affordable housing solutions for underserved communities.

Through three distinct case studies in “Preserving Community through Radical Collaboration: Affordable Housing Preservation Networks in Chicago, Washington, DC, and Denver,” Howell explores a community-based approach to social equity that works alongside government agencies rather than against them. This approach, described as “radical collaboration,” 5 consists of an inclusive

Terry Peterson, “A

Kathryn Howell and Barbara Brown

“Preserving

decision-making process that directly engages residents in the decision-making process for housing projects targeting underserved communities. It builds an inclusive and empowering framework for housing solutions, giving a voice to those most affected by housing challenges. “Radical collaboration focuses not just on the ongoing engagement among diverse actors, but also on the way that this horizontal collaboration can restructure traditional power relationships to coproduce more equitable outcomes.” 5 It plays a vital role in preserving access to affordable housing and decreasing displacement rates. Howell’s research exhibits that traditional approaches to affordable housing fail to address the complexities of rising house costs and gentrification, and she advocates for using local knowledge alongside expert resources, such as data and policy tools. The research concludes that local resources, such as tenant-led housing or neighborhood-based preservation initiatives, can be utilized during the design and construction phases; utilizing existing community assets can lead to more sustainable housing solutions tailored to the community's specific needs.

Howell’s research benefits the design of a mixed-use high-rise building by developing a rehabilitative framework for underserved and underprivileged communities. Her research on radical collaboration addresses current social issues related to affordable housing access, focusing on community-led

decision-making processes. This study benefits a project striving to give a voice to underserved and underprivileged communities most affected by housing challenges. This project will empower affected communities while continuing to shape a more comprehensive view of affordable housing solutions.

In Building a Better Chicago: Race and Community Resistance to Urban Redevelopment , Gonzales highlights how redevelopment projects can displace long-term residents and ignore their contributions to their neighborhoods. Redevelopment projects are often framed as productive revitalization, but the underlying gentrification can go unnoticed due to strategic marketing. “Developers market possibility for those who can afford it, but signs of redevelopment promising a 'better and new Chicago' raised questions for marginalized communities.” 6 Gonzales examines marginalized Black and Latino communities within the complexities of urban redevelopment and explains how traditional growth-based models can lead to gentrification and displacement, contrasting with her recommended assetbased approach. She views ‘collective skepticism,’ strategic mistrust marginalized communities use to challenge inequitable power dynamics, as a tool for positive change within marginalized communities. Gonzales uses the case studies of Greater Englewood and Little Village, two Chicago neighborhoods, to show how collective skepticism can be applied effectively as a mechanism to

6. Teresa Irene Gonzales, Building a Better Chicago: Race and Community Resistance to Urban Redevelopment (New York: New York University Press, 2021), 3.

produce greater accountability from city developers to achieve more equitable outcomes.

Gonzales’ research coincides with Howell’s comparative study, emphasizing the need to leverage the community's strengths to drive development that challenges gentrification and displacement. These studies show that community engagement must go beyond surface-level involvement to benefit marginalized residents truly. Gonzales' research benefits project exploration that aims to empower residents by giving them a decisive voice and ensuring longterm access to affordable housing. This environmental design will incorporate affordable housing with a focus on creating inclusive, resilient habitation that aligns with the values of the surrounding community. This may be achieved by incorporating mixed-use spaces and cooperative housing models that promote economic development, encouraging the asset-based model, and empowering community members to challenge inequitable power dynamics to retain affordable housing access.

De Jakoba Social Housing in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, is an example of affordable housing with socialization and equitability at the forefront of the design process. This project by Studioninedots encourages interaction among community members through staggered balconies that offer slight views between homes, fostering a sense of connection even for individuals

living alone. The building’s volumetric form was initially extruded as a box and then bent inwards to comply with local zoning regulations, creating a series of wavy balconies, which encourage socialization among occupants (see Figure 2.4). The design achieved a ‘campus-like’ setting that fosters interaction and community engagement. It addresses social issues by providing affordable housing and promoting a culture of equity within the community, housing residents from diverse demographic backgrounds.

This project influences the environmental design of a mixed-use high-rise by demonstrating how architectural features can enhance socialization and interaction within affordable housing communities. Creating opportunities for interaction among people from different racial and socioeconomic backgrounds will serve as a reference for community support, an essential aspect of equitable design.

Residential Complex Le Lorrain in

Vertical Coalescence

FIGURE 2.4: Diagram by Studioninedots December 2023, edited by author using Adobe Photoshop. Downloaded from https://www.archdaily.com, accessed October 2024.

Brussels, Belgium is another precedent for affordable housing that creates intentional spaces of socialization and community growth apart from the occupants’ restful home spaces. This project, designed by MDW Architecture, incorporates various types of housing and social spaces with a clear circulation path to navigate between collective areas (see Figure 2.5). These social spaces allow residents to get to know each other and become a close-knit community. Small residential spaces offer privacy and promote self-reflection, balancing solitude and community engagement and prioritizing occupants’ mental and physical health. This precedent provides solutions for limited living space and emphasizes the integration of versatile socialization areas that improve community dynamics.

This research into social and cultural issues emphasizes the role of intentional design in promoting equity and fostering community relationships. This will significantly impact the project approach, which aims to integrate adaptable social spaces within an environmental framework. This research will guide the creation of environments that encourage interaction, accommodate privacy, and foster a sense of belonging in community residents. Precedent studies highlight the need for communal areas that enhance social and physical well-being. This finding reinforces the idea that successful residential buildings blend individual needs with collective engagement opportunities. This understanding will

guide the design process to ensure the final design supports vibrant, inclusive communities through thoughtful spatial organization.

Integrating environmental principles in the design of a mixed-use highrise provides a pathway to achieving both environmental sustainability and social equity. Incorporating natural elements, sustainable systems, and high-performance technology makes it possible to create resilient buildings prioritizing environmental goals and occupant well-being. The precedent studies and professional insights explored within this research highlight the potential for environmental design to promote inclusive, community-centered spaces that enhance social equity while achieving long-term sustainability goals. Moving forward, this research will guide the development of a high-rise design that not only satisfies energy efficiency metrics but also strengthens the connection between people and the natural environment.