REVOLUTIONARY NYC

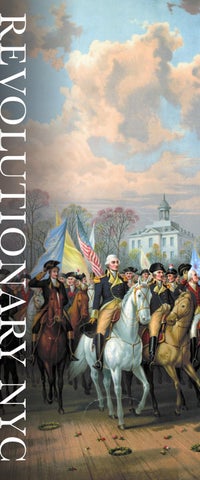

The NYC Revolutionary Trail is a three-mile/ five-kilometer (90-minute) journey through Lower Manhattan that highlights 16 sites important to the American Revolution, created by the Gotham Center for New York City History and sponsored by the Downtown Alliance. Visit all 16 locations or choose your own adventure for a walking tour that will have you following in the footsteps of those who founded the United States. Along this tour, you’ll learn how New York was not only the “city at the heart of the American Revolution” but also the place where the war began and ended. You’ll visit historical sites like Trinity Church, the Loyalist parish where Alexander Hamilton is buried; Federal Hall, the site of the first congress where George Washington was sworn in as president; and Bowling Green, where the invasion of North America began in the summer of 1776. You’ll also learn about sites of significance that no longer exist, like Fort George, the military headquarters of the thirteen colonies; Golden Hill, where the first bloodshed at the hands of Redcoats occurred; and Hanover Square, where the most famous (and infamous) printers of this era operated. The supplemental app provides 75 minutes of audio narration for the historical walking tour, spanning from 1763 to 1789. Download the app to access additional site information, character profiles and select video, as well as bonus text and imagery.

In 1763, Britain secured North America as the largest part of its new global empire by defeating France in the Seven Years’ War. New York served as British military headquarters during the conflict, a global war, and became the “general magazine,” or supplier, of His Majesty’s Army. Many had already come to see New York as “London in miniature,” but during those years, the city emerged as the unofficial capital of British North America. It had the only large permanent garrison on the continent and the greatest number of soldiers and royal officials. It also had the only monthly connection to England by ship and the second-biggest seaport and population. It was the largest consumer of British wares, and the center of news, fashion and opinion. Home to perhaps the richest merchants and landlords on the seaboard, it also had the reputation of being a model colony, rumored to be the King’s favorite.

But after 1763, New York was thrown into a depression, like Boston, Philadelphia and the other port cities. To help pay off nearly a century of wartime debt—and to keep colonials subordinate—Parliament strengthened the mercantilist economy, taxing goods the colonies had to import, policing trade with rivals, restricting local currency and loosely forbidding settlement on Native land. Over the next decade, more legislation followed. Much of it was repealed. Yet by 1776, a third of the population in big towns like New York was still living in poverty. With the bid for independence, New York became the scene of the first large military engagement, and what would remain the largest battle of the war. It became, once again, British military headquarters during the Revolution, only to emerge as the nation’s first capital.

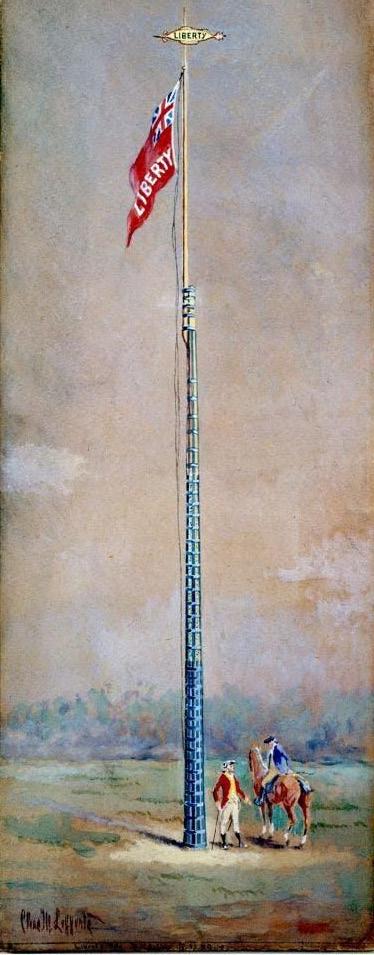

Image: This early 20 th c. painting by Charles MacKubin Lefferts, Battle of Golden Hill, NY, Jan 19,1770 , depicts the first blood shed in the American Revolution. The exchange with British soldiers left dozens severely injured, outraging rebels in Boston, who held a protest in solidarity which now mistakenly gets this attribution (the Boston Massacre).

(State Street and Battery Place)

Nearest subway stop: South Ferry ( 1 ); Whitehall Street/South Ferry (R, W)

Restrooms: Yes

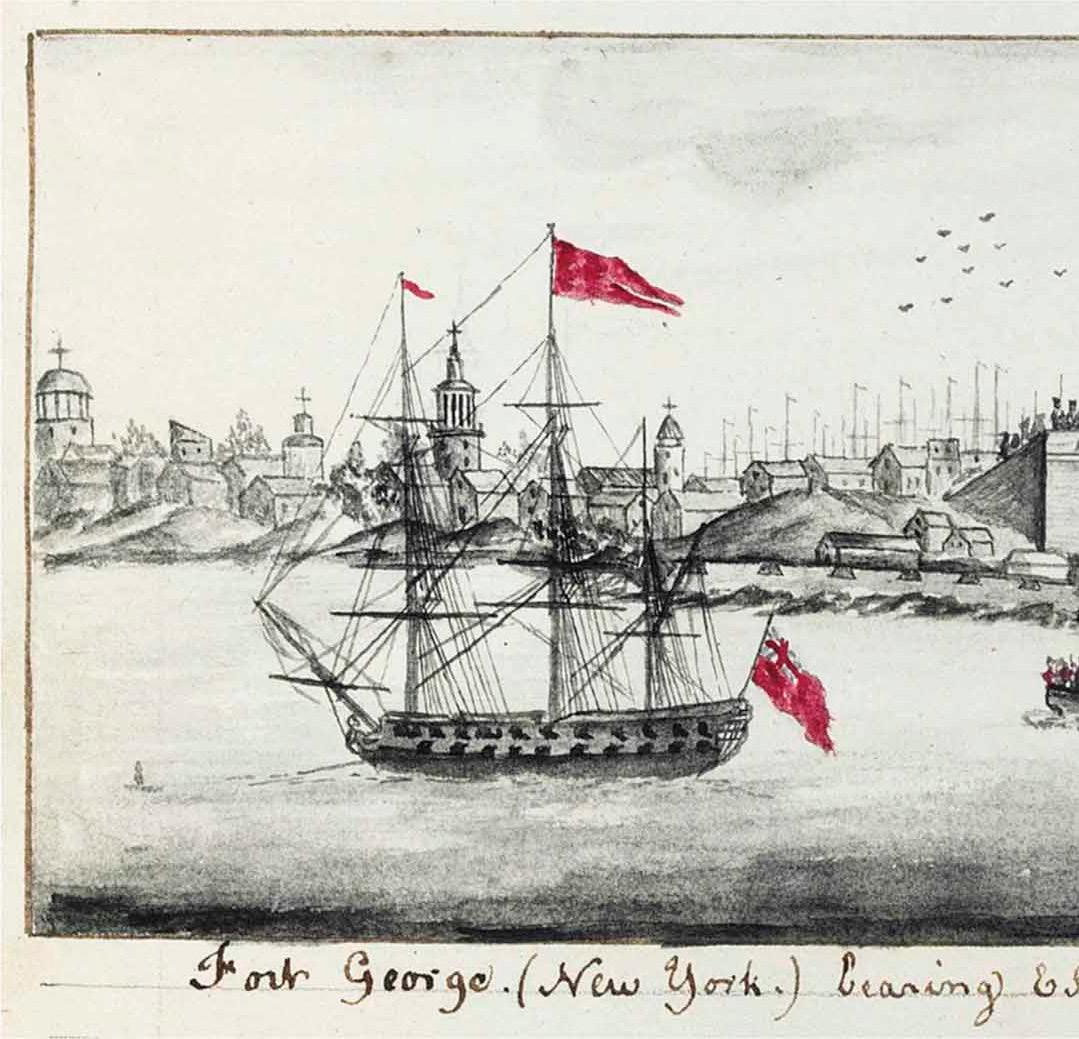

As New York’s value to the king grew, so did its military fortification. The city’s location at the end of the Hudson River provided greater access to North America than any port below Canada, and its deep-sea harbor was also closer than Boston to the West Indies, the most lucrative part of the empire. So, naturally, Britain made sure it was protected. The old wooden Dutch fort at the southern end of Manhattan was built up into New York’s largest structure, an imposing stone fortress that loomed over the city (sitting roughly in the footprint of today’s Museum of the American Indian). They also strengthened the “battery” around it, walls of cannon mount facing the harbor.

As the major symbol of British rule, Fort

George was a repeated site of protest during the Imperial Crisis ( 1763 to 1775 ). The governor, appointed by the king, lived inside with an entourage of 200 soldiers. The richest landowners and merchants lived outside in “crown town,” in grand mansions along Broad Way, the elite promenade leading north to the main barracks, the largest complex of housing, at the other end of the city. In between lay Federal Hall, where the ruling families sat in the colonial legislature, and the Commons, where rebels drew staggering crowds to protest in this era. The first major uprising came in 1765 , when a mob smashed nearly every window on Broadway while marching from the Commons, near the barracks, to Fort George, linking up with thousands of unemployed maritime workers from the waterfront. It was the largest and most violent demonstration in the colonies in that famous year. Thereafter, British military commanders feared a genuine revolution in New York, and local officials, in turn, feared they might impose a dictatorship.

(Coenties Slip between Pearl Street and Water Street)

Nearest subway stop: South Ferry ( 1 ); Whitehall Street/South Ferry (R, W)

Restrooms: No

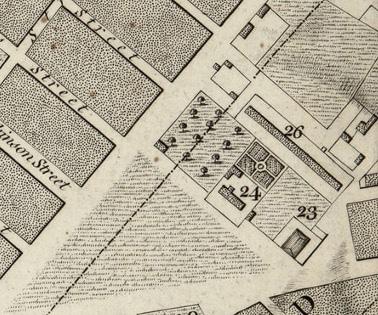

Image: Detail from The Plan of the City of New York in North America by British military officer Bernard Ratzer, created in 1766 to 1767 and printed in 1770 .

New York was second only to Philadelphia and London itself as the busiest port in the empire. Maybe a quarter of the city’s workforce belonged to its trade. So, in many ways, it was here on the colonial waterfront, memorialized at Coenties Slip, that America’s revolution began. While Parliament’s laws hurt everyone, maritime labor felt the pain most acutely. Beggars filled the streets, as the workers in the overcrowded East Ward, New York’s worst slum, fell into more than a decade of poverty. It was these Sons of Neptune who provided the strongest and most violent resistance during the Imperial Crisis.

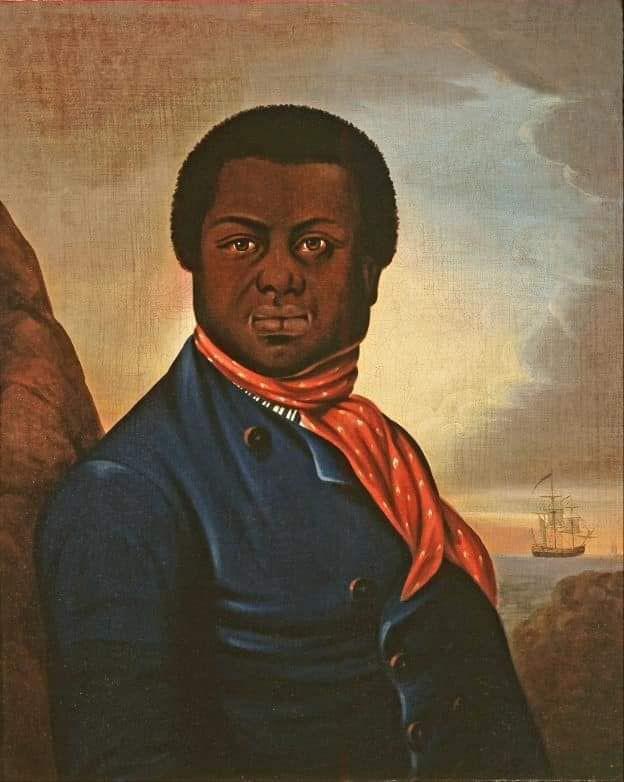

As in other ports, they were also the first to rebel. The merchants and printers who eventually bid for independence were often pushed by this more radical group, which spearheaded at least twenty-eight riots in the years to come. Unlike the more famous Sons of Liberty, who met at the Burns Coffee House (now a Starbucks at the corner of Thames and Broadway), these Sons of Neptune also looked more like New York. No city was more diverse — strolling the colonial waterfront, you could hear dozens of languages, European as well as traders and diplomats from eastern Indigenous nations and the Akan-speaking regions of West Africa. New York had more slaves than any city in the north, and they were heavily segregated and policed after the Revolt of 1711 and the Conspiracy of 1741 . But here on the waterfront, one found the greatest amount of racial mixing on the docks and the maze of taverns, brothels and gambling dens that lit up the East Ward at night. The neighborhood became a hotbed of democratic and insurrectionary sentiment, reflecting in particular the harsh, short lives of the “Jack Tars,” who defined the culture. Badly paid and treated worse at sea, these mariners also had to watch constantly for “press gangs” on shore who prowled the streets, kidnapping men to work for months, years or longer (as was the case with 40 percent of the British Navy).

( 3 Hanover Sq.)

Nearest subway stop: Wall Street/William Street ( 2,3 ) Restrooms: No

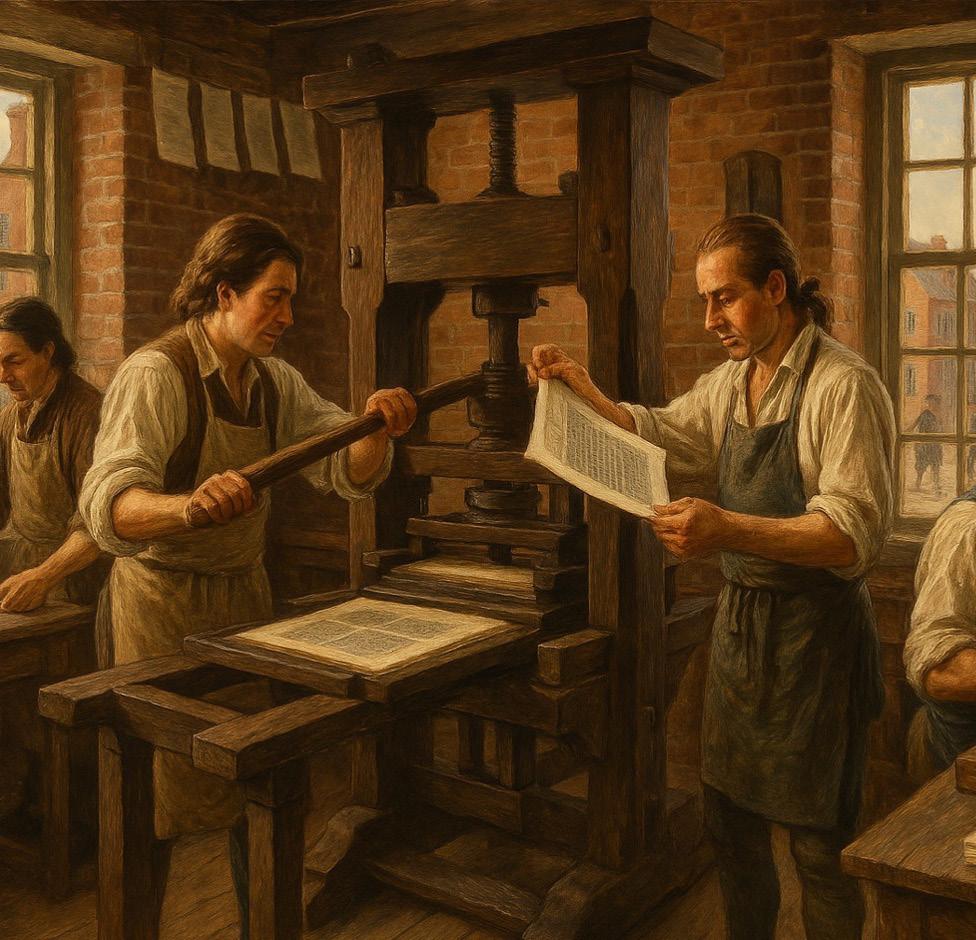

Hanover Square, or “Printers’ Corner,” was the leading media hub in colonial America. With ships arriving directly from London after 1755 , New York was often the first to receive and publish news from Europe, which then circulated north via Boston and south via Philadelphia. Generally moderate but rarely impartial and desperate for business, printers gave a new voice to dissent in these years by publishing anonymous broadsides that rebels plastered on trees and walls or passed around taverns. Even more importantly, they created the first communications between the colonies, which had previously existed as strangers. Essential to organizing protests, printers also built a sense of nationalism, making “Americans” of “Englishmen.”

Image: Woodcut depicting NYC’s infamous “Tory printer” James Rivington hung in effigy, published by himself in Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer, April 20,1775. King George III made him the official printer of British North America during the Revolution. Historians now believe he spied for Gen. Washington.

The Stamp Act was perhaps the most galvanizing event for printers: Imposing a tax on an already fragile, nascent business and tighter regulation on the small, heavily censored realm of news and opinion. Although the measure was never really enforced and ultimately repealed, the other regulations that kicked off a depression remained, and the following Townshend Acts taxed paper and other imported goods. The first of these new laws was also the most radical. It suspended New York’s legislature for refusing to house and feed the city’s unrivaled number of soldiers. It was “the first official act of disobedience” in the colonies and the most severe punishment by England until the Boston blockade seven years later, which sparked the Revolution. Figures like James Parker and John Holt were important figures during this period, much like Hugh Gaine and James Rivington would become later, when the colonists split into Patriots and Loyalists.

(49 Fulton St.)

Nearest subway stop: Fulton Street ( 3 ,2 , A, C, J, Z)

Restrooms: No

For decades, New Yorkers saw the Redcoats flooding their city as emblems of prosperity. But now they represented hated foreign rule and pressure on rent and wages. Isaac Sears only fueled tensions. The old privateer was the radical link between the Sons of Liberty and the Sons of Neptune, dubbed the “king of the mob” or “Sam Adams of New York”. In 1766 , he began erecting “liberty poles,” or tall white pines strictly reserved for British Navy masts, near the main barracks (where City Hall is today). Adorned with political messages, they were designed to provoke the soldiers who used the Commons. Troops had already destroyed several before New York’s legislature was “suspended” in 1767 . But the standoff resumed after colonial leaders allied with James DeLancey imposed another tax in 1769 , for quartering Redcoats. Tensions mounted daily on the street, as rebels forced vendors not to serve any soldiers and the commanders often restricted them to barracks. At Fort George, the new governor, who had promised to demilitarize the city after the Great Riot of 1765 , feared that General Thomas Gage was planning to “introduce a military government.”

Soon, teenagers plastered the city with an open letter calling New York to “arms,” describing the so-called Quartering Act as the “Design of Tyrants” meant to “enslave a free People.” Its author was another sea captain who had privateered for the British, Alexander McDougall. He followed with a second broadside, framing DeLancey’s tax as a kind of conspiracy, meant to establish oligarchy and dictatorship. McDougall added that ordinary New Yorkers were now paying for the soldiers’ “whores and bastards,” alluding to “Holy Ground,” an elite red-light district near the barracks (so named because it sat on land belonging to Trinity Church, where the Anglican minority that ruled New York worshipped). Enraged, soldiers responded by exploding the rebels’ liberty pole. Days later, Sears cornered a group of Redcoats near the waterfront. Gathering a crowd, he pursued them to Golden Hill, where soldiers drew bayonets. Dozens were severely injured, and the event was followed by another violent exchange on the Nassau Street docks the next day. No one died, but the altercations marked the “first blood shed in the Revolution” and outraged comrades in Massachusetts, instigating the more famous Boston Massacre.

Nearest subway stop: Fulton Street ( 3 ,2 , A, C, J, Z)

Restrooms: Yes

Image: Detail of William Elliott, Lord Rodney’s flagship Formidable breaking through the French line at the Battle of the Saintes, c. 1784-87. This painting of the greatest British naval victory in the war gives the closest approximation in scale of the 1776 invasion of New York. Over six weeks, 421 ships appeared in the harbor, carrying 30,000 soldiers. It was the largest amphibious assault until World War II.

Facing mass resistance and losing revenue once again, Parliament repealed most of the regulations and taxes it had imposed during the second wave of legislation—except for tea.

New York’s rebels were the first to respond, blocking distribution at the waterfront, and here at the Seaport, you can see where they staged their own “tea party” after Parliament made the highly demanded product a monopoly in 1773 (to bail out the East India Company). Boston’s more famous action, however, led to another wave of legislation, the so-called “Intolerable Acts,” which closed Boston’s harbor, restricted Massachusetts’ power of self-rule and forced all the colonies to house and support England’s Redcoats. Protest now shifted radically to a bid for independence. But where New York had inspired rebels a decade earlier over the Stamp Act crisis, now they began calling it “Tory-town,” because it was the last to vote for this dangerous measure. New York was perhaps the most violently divided city in the colonies. But its division mirrored the

split across the seaboard, where rebels had no more than an estimated 40 percent of support. Suddenly, the Revolution began to resemble what historians now call “America’s first civil war.”

After shots were fired at Lexington and Concord, rebels drove New York’s government onto British warships in the harbor, raiding the fort and barracks, driving opponents into exile and imposing loyalty oaths on the neutral. The city fell under martial law; every white man and Black slave ordered to build fortifications around its waterways. It would be more than a year before London invaded. But New York was central to British military strategy: John Adams expressed the rebels’ opinion, calling it the “key to the whole continent.”

The Battle for New York in the summer of 1776 would remain the largest of the war. Most of the city’s 25,000 residents fled, expecting disaster. They woke up one morning in June to find 100 ships in the harbor. Over the next six weeks, 327 followed, carrying 32,000 soldiers in all. It was the largest naval invasion until World War II. At the Seaport, you can see where they disembarked in Tompkinsville, Staten Island, before starting the fight in Gravesend, Brooklyn. It was a horrible, embarrassing defeat for General Washington. But under the cover of a random heavy fog, a group of skilled deep-sea fishermen (Native, Black and white) led the remnants of the Continental Army over a mile of treacherous East River currents, saving America’s bid for independence from destruction at the very start.

Image: This portrait of a Black sailor by an unknown artist is a reminder of the Marblehead Mariners—a group of free whites and slaves who prevented Gen. Washington and the rest of his army from British capture at the very start of the Revolution. The Battle for New York, which remained the largest of the war, boxed rebels into a corner in Brooklyn Heights. These skilled guides carried them silently across the East River while 421 British ships lay in the harbor.

(Peck Slip and Water Street)

Nearest subway stop: Fulton Street (2, 3, A, C, J, Z)

Restrooms: No

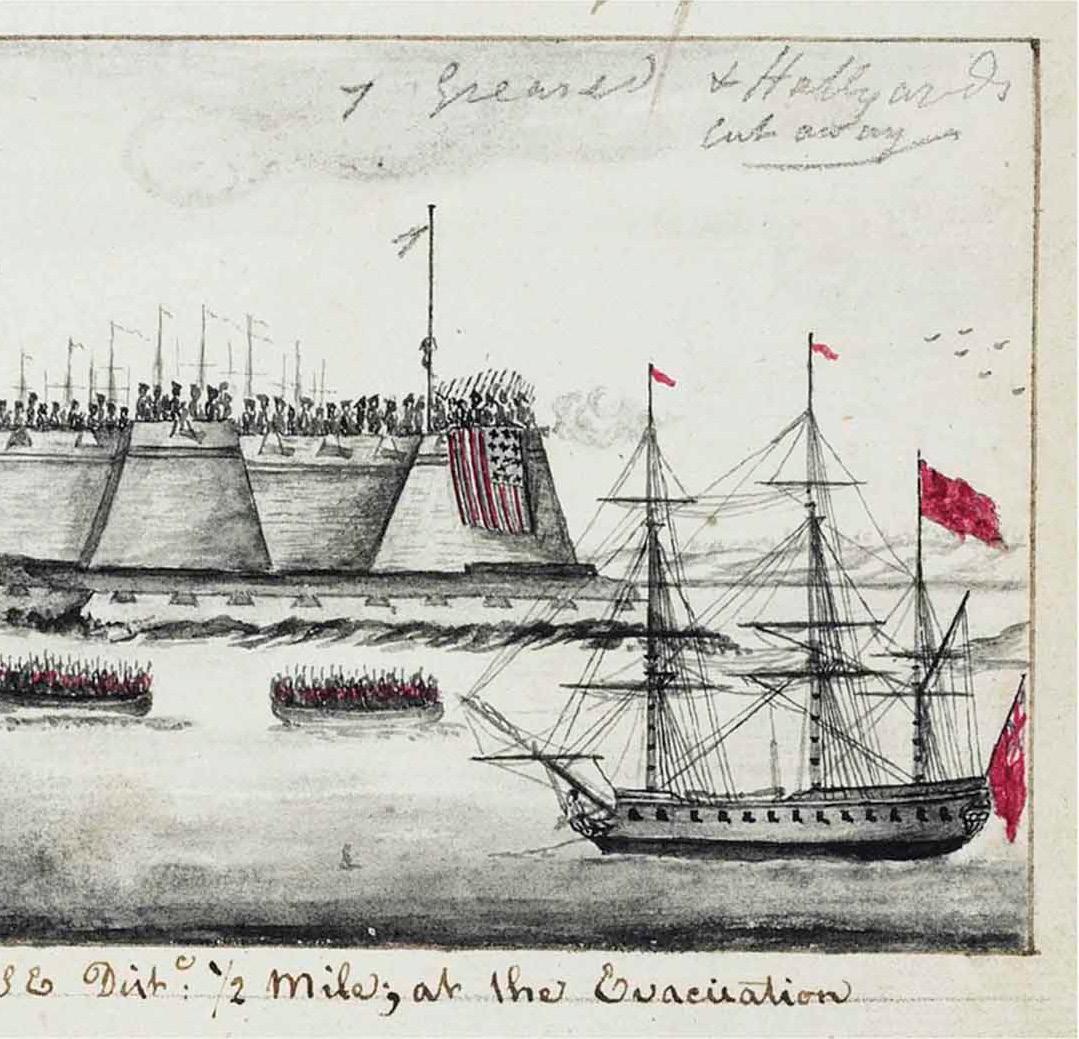

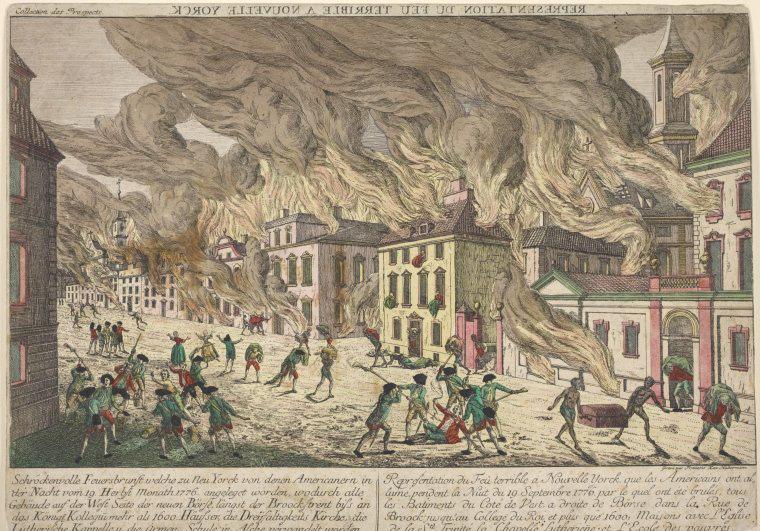

Here at the city’s first public market (where some think Washington began his escape from New York), one can assess what British victory meant for the region. New York remained Britain’s headquarters during the war, its only uncontested stronghold. And for many, especially the slaves who joined their ranks, it became an “island of freedom.” But life worsened steadily for all but the most elite. An enormous fire, likely set by rebels, destroyed maybe a fifth of the city in September 1776. In the ashes, “Canvas Town” emerged: a giant open-air refugee camp, running along the west side. Over the next seven years, scores of loyal, neutral and even rebel figures came in search of asylum; nearly a third of the war’s 772 battles and skirmishes were fought in New York State alone. The city’s population soared from 5,000 to 50,000. Homelessness and overcrowding peaked. Resource depletion caused prices to jump eightfold. Record cold winters froze the harbor. Epidemics killed untold numbers. And raids turned the surrounding metropolitan region into a “lawless no-man’s-land.” New York saw the worst poverty and death it has ever known during this period, the least known part of its history. Even the wealthy ruling families complained, excluded from government and living under often-brutal martial law. As such, loyalty gradually eroded across the region.

(72 Park Row)

Nearest subway stop: Brooklyn Bridge City Hall (4,5,6); Chambers Street (J, Z)

Restrooms: No

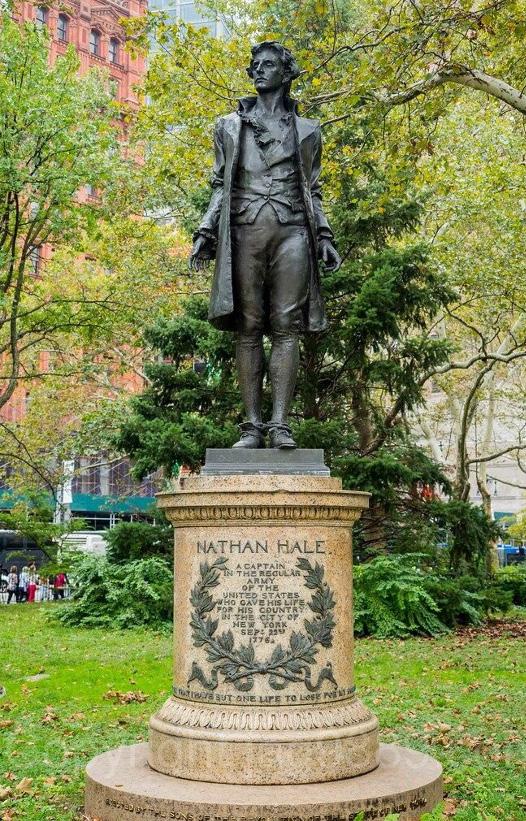

This hidden sculpture in City Hall Park honors the Revolution’s most famous spy and one of its earliest martyrs— 21-year-old Nathan Hale, who was hanged in a Midtown field shortly after the Battle of 1776. But New York was the center of espionage until the war’s end. It remained British headquarters, the only consistent stronghold, and Washington kept a large number of Continentals staged outside the “Neutral Ground” in today’s Westchester County, near-obsessed at times with the hope of recapture. His lieutenants also recruited several men and women (free and enslaved) for a spy ring in Manhattan and Long Island that has become more famous in recent years. Some argue this group marked the birth of U.S. intelligence gathering. But the military quickly learned that women and slaves functioned as the real data leak in New York. They had a looser rein to move goods or visit family, and they were also privy to conversation in taverns and private rooms, all of which made them far more common — if anonymous — “spies.” And the spying went in both directions. New York’s rebel governor, and Washington himself, complained bitterly of “tories” in their midst.

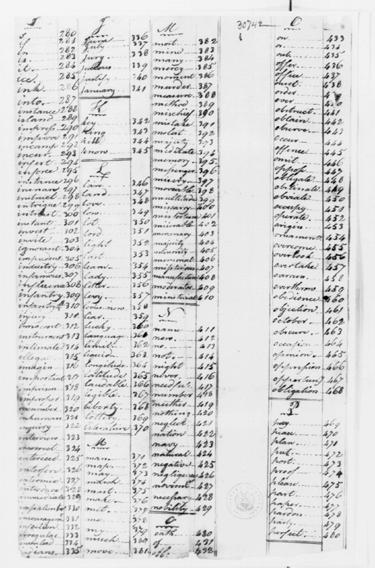

Image: Washington’s papers, deciphering the code of his spy ring in greater New York (Manhattan/Long Island).

Nearest subway stop: Brooklyn Bridge City Hall ( 4,5,6 ); Chambers Street (J, Z)

Restrooms: No

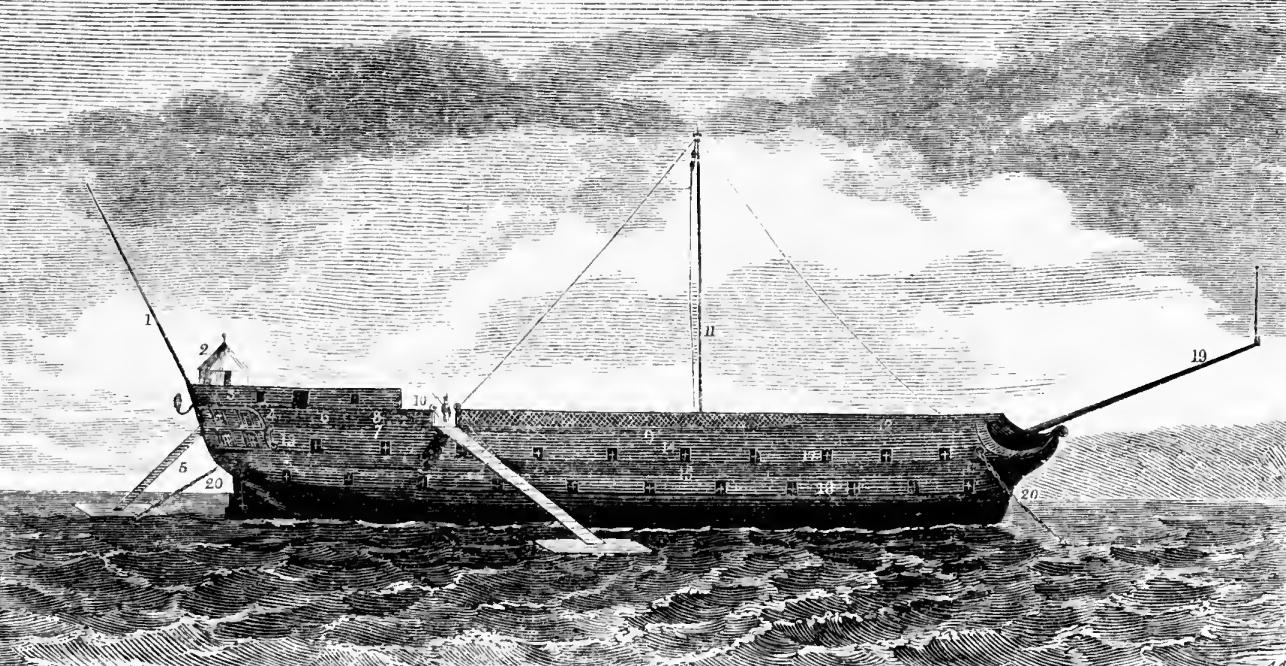

Image: The Jersey Prison Ship, moored at Wallabout Bay near Long Island, in the year 1782. From “Recollections of the Jersey Prison Ship,” by Thomas Dring.

Under the rebels, New York became a “garrison city.” Under the British, it was a city of prisons. Thousands were captured in 1776 , but by the end of the war, almost 30,000 were imprisoned, most held in New York. With the housing shortage, almost every church, warehouse and building owned by accused rebels or sympathizers became a jail. Conditions were utterly brutal, if standard for that era. Upwards of 18,000 died from neglect, torture or execution — nearly four times as many as the battlefield. New York became the home of the Revolution’s dead. Largely unremembered now, printers spread the news across the colonies, diminishing British support even further among the neutral and loyal. This barred window, tucked behind NYPD headquarters, is the last remnant of a huge sugarhouse that is rumored to have been one such tomb. But the darkest was the HMS Jersey, a retired warship anchored in Wallabout Bay, nicknamed “Hell.” For many years afterward, the skulls of “America’s first P.O.W.s” covered the beach “like pumpkins in autumn,” bones washing up across the region.

(Centre Street and Chambers Street)

Nearest subway stop: Brooklyn Bridge City Hall ( 4,5,6 ); Chambers Street. (J, Z)

Restrooms: No

Image: Adam Sherriff Scott’s painting, commissioned in 1933, depicts the arrival of 60,000 Loyalists who mainly disembarked in New York at the end of the war. There are very few images depicting similar numbers of refugees created during the Revolution, most of whom fled to New York as it was the only consistent British stronghold.

New York struggled to house, feed and clothe the huge influx of soldiers in Washington’s army in 1776 . But such needs became almost impossible when the city’s population exploded during the war. The public almshouse that once stood above the Commons only served a fraction of the poor. Far more ended up in the debtors’ prison next door, built during the Imperial Crisis. And the occupation merely brought greater hardship. The British attempted, but proved unable, to provide adequate food, water, shelter, medical care and employment. When they failed to meet those needs, people went outside the law. Canvas Town, the open-air camp named for the cloth that covered burnt frames of the mansions of the West and Dock wards, became a home for not just wartime refugees, escaped slaves and “ladies of pleasure,” but huge numbers of unhoused soldiers and their families. The Revolution became a vortex, with the constantly mounting demand on basic necessities like food and wood fueling raiding parties and vigilantism, exacerbated by Little Ice Age winters and epidemics of cholera and smallpox. By the end of the war, observers marveled at the destruction. Even outside New York, where there had once been dense forests and teeming fisheries, the city looked physically exhausted.

(248 Broadway)

Nearest subway stop: City Hall (R,W); Brooklyn Bridge City Hall ( 4,5,6 )

Restrooms: No

Between 1778 and 1780, the British managed to regain control of huge swaths of the colonies, launching incursions into the rest. Yet it struggled to hold on to any region but New York, and the war carried on, grinding down public will and support. The British vowed to restore the rule of law, but it only deteriorated under their control. And now their own soldiers contributed to the violence and corruption further eroding loyalty and neutrality. Still, British soldiers fared poorly, too. Here at the barracks that once engulfed the northern side of City Hall Park, 500 Redcoats were housed 20 apiece in tiny rooms. But New York rarely had less than 10,000 soldiers, forcing most to live in tents or huts in upper Manhattan, surviving on

This detail from Bernard Ratzer’s 1769 map of New York shows the main barracks. Longer than a modern block (420’ x 20’), it was the largest building in the city, housing 800 men. Like Fort George, the massive structure at the southern end of town, it symbolized New York’s identity as British military headquarters for North America. During the occupation, another three were built.

contaminated water and dried wells, or in makeshift camps along the East River, where sailors in the crowded slum often resorted to hammocks and lean-tos. British officers praised the rank and file, but the Redcoats were often highly disillusioned. Many were again banned from the city’s taverns, now because of heavy drinking—an escape from boredom and brutality. At first, many were paid better than at home (which meant a dozen European countries, not just England). But it decreased over time. And death meant an unmarked grave, thousands of miles from loved ones. British leadership was also demoralized — they expected an easy victory, having previously built a global empire while fighting powerful rivals like the Spanish, French, Dutch, Swedes and the Kalmyks. But while rebels spent most of the war in retreat, the British were engaged in a guerilla war over a vast territory with almost no partners, facing unprecedented costs and much greater debt than colonials ever faced. Very soon, they faced challenges across the empire in old conquests like Ireland and new ones like India.

(209 Broadway)

Nearest subway stop: Fulton Street ( 3 ,2 , A, C, J, Z)

Restrooms: No

Image: The Death of General Montgomery in the Attack on Quebec, December 31,1775, John Trumbull.

Image: Monument to Richard Montgomery at St. Paul’s Chapel; the first Revolutionary monument in the U.S.

St. Paul’s Chapel is New York’s oldest public building. It’s also the site of the nation’s first Revolutionary memorial. The stonework on the central face of the building honors Richard Montgomery, a U.S. major general who died in the failed effort to annex Canada in 1775. Montgomery was an odd choice for martyrdom. Irish-born, he served in the British Army, only moving to America in 1773. His partner in the campaign, Benedict Arnold, had a strange arc, too. An early hero of the Revolution, Arnold became its greatest villain after defecting in 1780. But allegianceswitching was not unusual in the Revolution. As in most wars, people weighed the odds and bet on each side as the contest seesawed, ultimately putting their families first.

(89 Broadway)

Nearest subway stop: Wall Street (4, 5) Restrooms: No

The original Trinity Church punctured the New York skyline.

Trinity was founded in 1696 and represented England’s church of state (New York, as diverse in faith as it was in ethnicity, had no established religious institution). Queen Anne gifted Trinity 215 acres of Lower Manhattan, making it one of the wealthiest churches in North America. By 1750, most of New York’s upper class had joined its congregation. On the basis of that success, it built two more chapels on Broadway for the Anglican minority. It was no coincidence that its 172-foot spire could be seen from every point in the region.

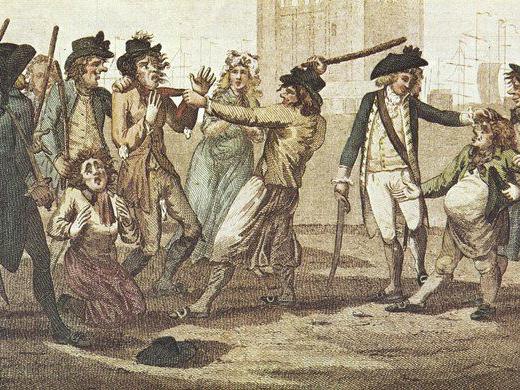

Contrary to myth, Loyalists were not generally rich or elite: Trinity was an exception. Loyalists were not “Tories,” either. Most were Whigs. No one wanted absolute monarchy or total imperial rule. But in the late years of the Imperial Crisis, the ministers who represented England’s church of state became the figures rebels most hated and deeply feared. Samuel Seabury is a famous New York example. But Trinity’s rector, Charles Inglis, was an even more powerful one. A moderate, he became the voice of a far more radical loyalism during the war, alongside Ben Franklin’s estranged son William, calling for what might be called total civil war, a position which unnerved even the British. For that reason, most of Trinity left for Nova Scotia and other parts of the empire when peace negotiations began in 1781, along with 60,000 hardliners, many under warrant for execution.

(1 Bowling Green)

Nearest subway stop: Bowling Green (4, 5)

Restrooms: No

Image: Pulling Down the Statue of King George III, N.Y.C. by Johannes Adam Simon Oertel, though historically inaccurate, shows the King’s statue being torn down by the mob in Bowling Green.

Bowling Green is New York’s oldest park, used by the colonial elite to relax, play cricket and, yes, bowl. But its location outside the fort made it a frequent spot for rebel protest. The most famous example occurred in 1776. After Parliament repealed the Stamp Act, the city built an enormous sculpture of King George III on the empty pedestal (fountain) you see here now. It was the only statue of the monarch in North America, leafed in gold. But a mob pulled it down on July 9, after hearing the Declaration of Independence, then paraded the body like a criminal through New York’s streets before sending the 4,000 pounds to a foundry where a group of women rebels melted the lead into 42,088 bullets to fire on His Majesty’s Army. So it was only natural that New Yorkers gathered here again on November25,1783, to celebrate the end of British rule and Washington’s triumphal return to the city. The event became known as Evacuation Day, a major holiday in New York that was celebrated until World War I.

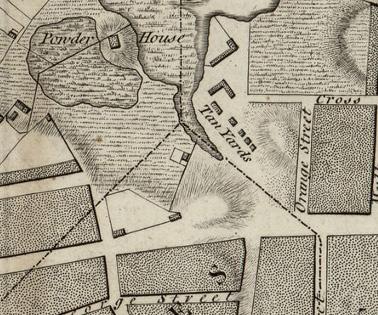

The museum that looms over this plaza today is a reminder of the war’s devastating effect on Native Americans, too—especially for the Iroquois League in upstate New York. The six Haudenosaunee nations were the most powerful Indigenous alliance on the continent, but they divided over the Revolution. After the British-aligned Mohawk, Onondaga, Cayuga and Seneca crippled the rebellion in western New York, Washington ordered General Sullivan to lead one of the biggest and least-known campaigns of the war. Thousands were killed and more than 40 villages were destroyed. But peace was no better for the “Patriot Indians.” A frenzy of land sales and settlement in upstate New York followed the end of the Revolution. Groups like the Oneida, Tuscarora, Mohican, Wappinger and Munsee were among the very few to support the rebels. They were forced onto reservations in or near Canada, alongside the “Loyalist Indians.” Their contribution to victory was also erased.

A notable exception is the monument for the Stockbridge Massacre in today’s Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx. As the U.S. spread across the “frontier,” extending slavery as well, paintings, illustrations, memorials and texts increasingly whitewashed the highly diverse profile of both armies in the Revolution.

(54 Pearl St.)

Nearest subway stop: Whitehall Street (R, W); Bowling Green (4,5)

Restrooms: Yes, 9 a.m. – 4:30 p.m.

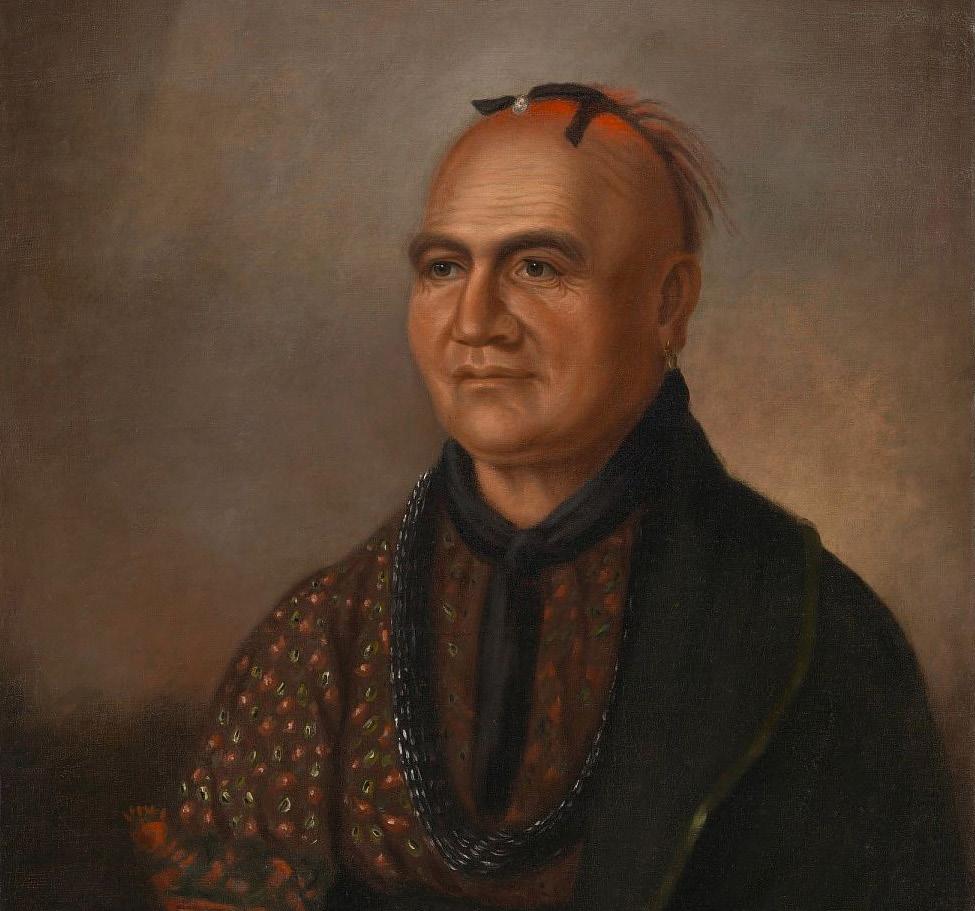

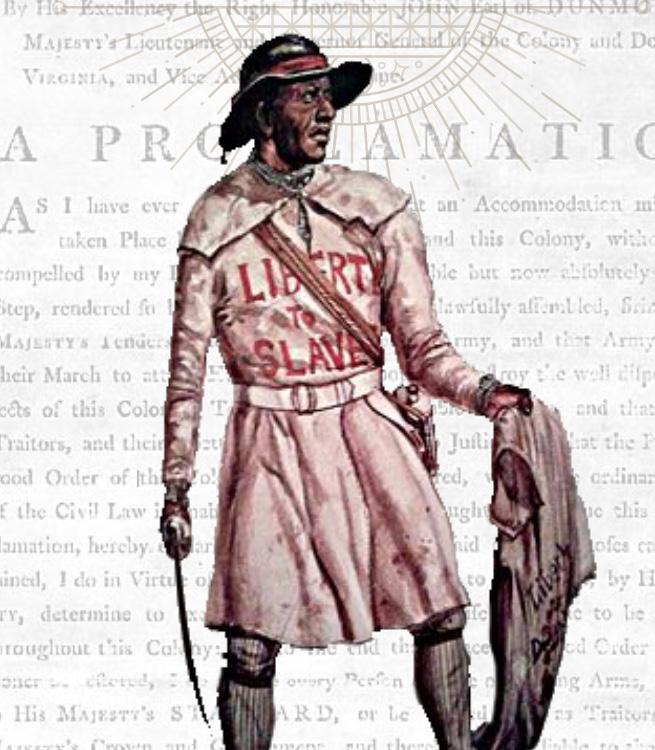

Image: Colonel Tye was one of the most famous of the Black Loyalists.

Fraunces Tavern began as the home of the Delanceys and, later, the marquee restaurant of the British colonial elite. Today it is best known as the site where General Washington delivered his farewell address, and it was later used as the “first White House” during the years New York served as the first capital from 1784 to 1791 . But in the last months of the war, it saw a much less recognized chapter of the Revolution, the Birch Trials, an emancipation that would not be equaled until the Civil War. It was New York’s former governor, Lord Dunmore, who offered the enslaved freedom

if they abandoned their rebel masters in 1775 . Around 20,000 took up the call, and roughly half came to metropolitan New York, making harrowing, dangerous journeys from across the colonies. Black soldiers guarded the entrance at King’s Bridge in the “Negro fort,” and they served the British in great numbers. Figures like Stephen Blucke, who commanded the Black Pioneers, or Colonel Tye, whose guerillas struck up and down northeastern New Jersey, terrified rebels and upset neutral and loyal slave-owners, too, who feared the divide-and-conquer strategy was destabilizing. It was. But after peace talks began, kidnappers began filling New York’s streets, grabbing “runaways” and the minority of free people alike. Boston King, a Black Loyalist, described the horror of watching men, women and children taken in broad daylight. Guy Carleton, the last commanding general of British North America to sit in New York, ordered a commission that safeguarded the liberty of 3,000 (including Harry Washington, enslaved to George Washington). It proved a sore point in the negotiations and decades-long legal battle. But London arranged for repatriation, and even, in some cases, land and pensions. Most of the Birchers went to Nova Scotia, where they established some of the first Black churches. Others went to German kingdoms and England, where they later set up a free colony in Sierra Leone.

Image: Washington’s farewell address.

(Stone Street and Mill Lane)

Nearest subway stop: Wall Street/William Street (2,3)

Restrooms: No

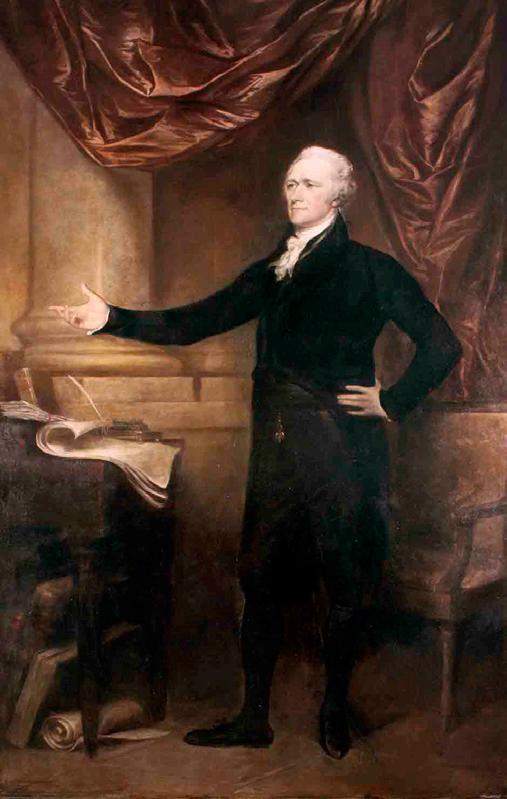

Alexander Hamilton converted to rebellion under the influence of Hercules Mulligan as a King’s College student in New York, and then served as Washington’s unofficial chief-of-staff during the war. He returned after the peace, and got a law degree within months, opening his first office at 57 Wall St. (now gone), before relocating to 69 Stone St. and later Exchange Place. It was here the hugely influential founder wrote most of “The Federalist Papers,” a series of op-eds that attempted to convince the largely anti-Federalist state to cast its pivotal vote for ratification of the Constitution. Those articles were published nearby at Hanover Square, the nation’s first media capital, and down the street from the government’s new home, Federal Hall.

Hamilton also set up the country’s first bank and helped its first manumission society, too, here in New York. But his reputation in these years was built mostly on the lesser-known part of his career, the reintegration of the Loyalists. While 60,000 fled, perhaps 450,000 remained, and Hamilton built a lucrative practice challenging the laws that stripped them of property and civil rights. His case against Elizabeth Rutgers laid out arguments the Supreme Court later used to claim judicial supremacy. But Hamilton also noted, rightly, that colonials had often switched allegiances during the Revolution, and more importantly that America needed capital, with the U.S. economy arguably in a 1930s-scale depression. His argument went national.

(26 Wall St.)

Nearest subway stop: Wall Street Station (4,5); Wall Street/William Street (2,3)

Restrooms: No

Federal Hall is New York’s most-visited Revolutionary site, marking the spot “where America’s democracy was born.” It was originally England’s colonial legislature, built using stone from the old Dutch palisade meant to keep out the Lenape (the “wall” that would become Wall Street). It expanded into a three-story building that towered over Broad Street, the main commercial thoroughfare, and was the meeting place for the Stamp Act Congress, the first gathering of leaders from across the colonies. During the war, it served as a prison for elite P.O.W.s like Nathan Hale. Afterward, it was the home of the Articles government, as well as the Supreme Court, various executive offices and the U.S. Congress. But, most famously, it is the place George Washington was sworn in as the first president of the United States. The building you see today is not the original. The original, designed by Pierre Charles L’Enfant, was demolished in 1812 . But today’s Federal Hall stands on the exact site, with roughly the same dimensions, and was completed in 1842 as the Custom House for the Port of New York. Today, Federal Hall National Memorial is a historic site and museum operated by the U.S. National Park Service.