7 minute read

Domes of Revolution Andrea Di Stefano y Aleksandra Jaeschke

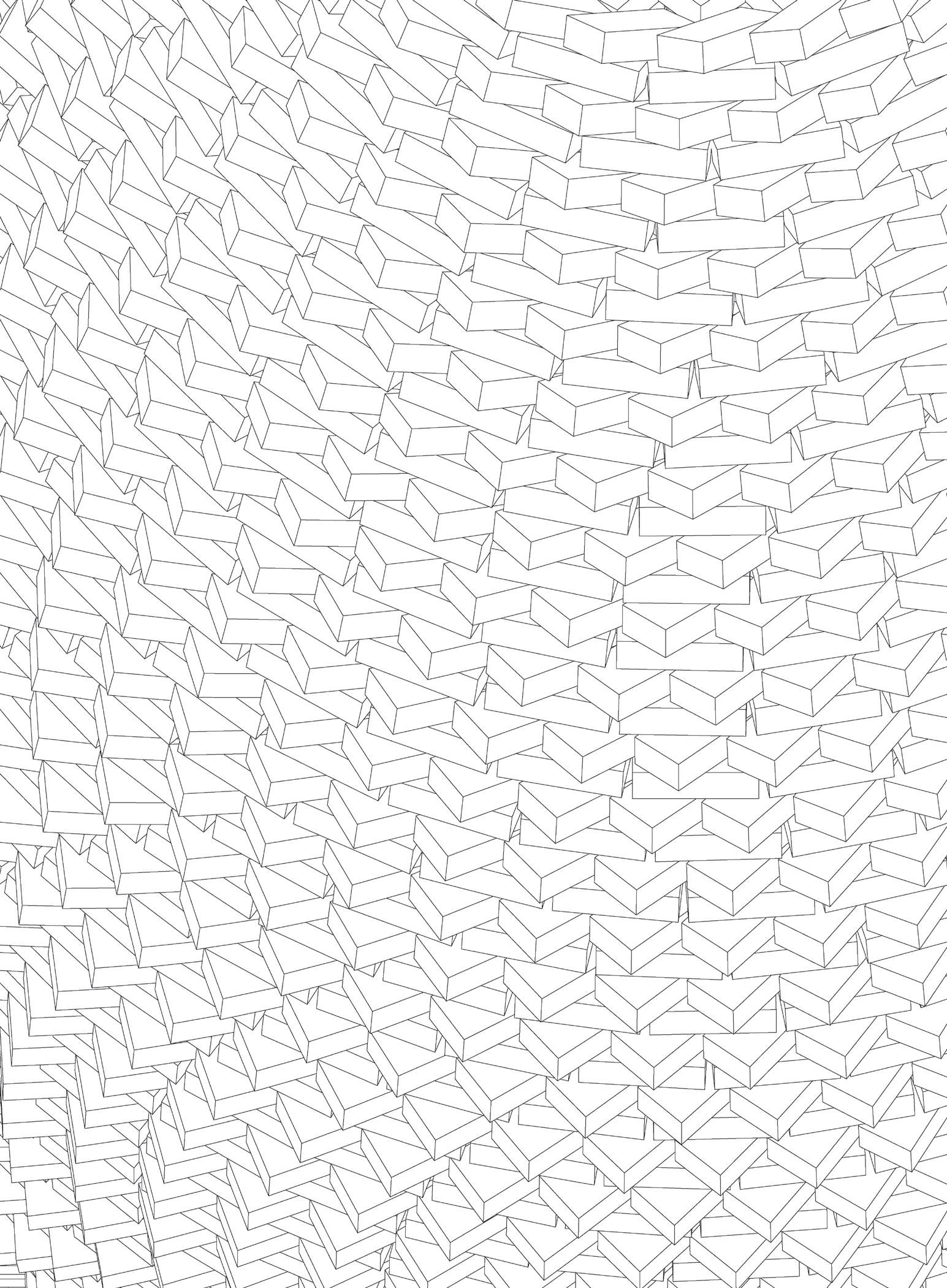

UTDT EAEU, Programa en Arquitectura y Tecnología 2014, Taller. Spliner, axonometría, sector

Starting from a piece of stretched string pulled around a nail fastened to the ground to inscribe a circle, the graduated compass used to draft, measure, and control the dimensioning of buildings, has been for thousands of years the principal instrument in architecture, to the point of becoming the symbol of world order. It was the only device used in all phases of architectural production, from the concept to the construction. Allowing the transfer of information across scales, and with consistency from one space to another, it positioned design and construction in perfect continuity. Architectural jargon itself confirms it: to inscribe a hexagon in a circle, one would use a sesta (ancient Italian word for compass) and mark six chord lengths along its circumference to achieve precise geometric constructions. The word sesto, which meant intrados, is still used in Italian to name different types of arches: round (tutto sesto) or segmental, stilted, and pointed (sesto ribassato, sesto rialzato, sesto acuto). Likewise, to build an arch or a dome, blocks would be placed along a curve (assestamento) to eventually put the structure under compression (assestata). Usually a dome would be built using a wooden centering, and whenever the temporary framework could not be utilized due to practical limitations or lack of material resources, compass-like devices were used directly during the construction process. This was possible because, geometrically, a dome is a rotational solid determined by the movement of the instrument itself, and, most importantly, because a true dome can support its own weight throughout all stages of construction. Unlike a temporary framework, which acts as a medium between design and construction, the use of a mobile compass establishes an immediate relationship between the project and the artefact. Paraphrasing Guattari’s definition of the diagram, the compass “works directly with the realities it refers to”(1). It is the antithesis of representation: a device that contains in itself the abstract order of the revolving solid, it is simultaneously used to physically organize the materials that constitute the final construct. In these same terms, Filippo Brunelleschi, the inventor of geometric perspective, described the use of the compass as a reduction of reality to a discrete, calculable, and therefore manoeuvrable dimension. In order to build what remains the largest brick dome ever constructed, he designed a self-supporting structure that did not require a fixed framework. Further into the construction process, a mobile device was developed to gradually relocate a string-based three-arc system of reference to different heights. This allowed the virtual reconstruction of the basic geometry: a solid, generated by a catenary curve revolving about its axis. Understanding form as a reflection of the perfect order of nature, Brunelleschi attributed an ordering potency to the catenary. The structural diagram emerges as a calm force that organizes an entire material universe, from the scale of the city to that of every single brick that constitutes it. The actual structure of the cupola of the building is made by two interconnected domes, which were lobed to match the octagonal drum on which they sit. Contained between them is the catenary diagram that underlies the entire construction. Simply by tracing arcs in space with strings, the structural diagram drives the positioning of eight ribs, controls the exact surface curvature of the lobes, defines the correct angle of bricks, and guides the spiralling rib embedded in the brickwork in order to resist asymmetrical lateral loads. The same diagram is locally differentiated to distribute voids that facilitate the drying of masonry, generate corridors and staircases, introduce light, and induce airflow. The dome of Santa Maria del Fiore is conceived as an architectural machine that synchronizes the mechanics of nature, the artefact together with its functioning, and the apparatus employed in its construction. The outcome is a masterpiece, in which the political, the technological, and the aesthetic find a new agreement to coexist in harmony: the construction of an ethical perspective for the people of Florence.

Advertisement

Even if minor, the history of the building compass has been marked by significant moments: from the ethereal three-arc system developed by Brunelleschi to the massive wooden compass used by Alessandro Antonelli to build the dome of the Basilica di San Gaudenzio in Novara. The rise of modern engineering and industrialization of construction processes rendered this centuries-old technique practically obsolete. Nevertheless, it has been preserved until our days in vernacular architecture. It is still used to build traditional Italian brick ovens, and to construct Nubian and Egyptian adobe structures. In fact, it was in Egypt that Hassan Fathy reclaimed the compass to turn it into the pivotal point of his social and architectural project for New Gourna, as it both facilitated self-construction and guaranteed typological consistency and high environmental standards. Drawing from this experience, the Italian architect Fabrizio Carola developed a range of compass-generated spatial configurations during a long period of professional activity in Mali. Working with pointed domes obtained by shifting the hinge of the compass away from the centre of rotation, Carola expanded the formal repertoire, and refined the compass to produce series of domes of various scales, rendering it reconfigurable to generate families of different domes with one compass only. As the focus of investigation shifted from the design of form to the engineering of the formation process, structural intelligence, construction logics, and spatial organization acquired further continuity. While restrained by the structural, geometric and assembly logics, Carola’s compasses generated a wide range of formal configurations, rich in spatial qualities and larval functional opportunities. Along these lines, the evolution of the compass developed by studio AION in recent years opens up a new spectrum of control parameters, rendering each movement measurable. Through this, the compass has become more flexible and programmable. Associated with a digital parametric model, it now becomes possible to evaluate the performance of particular solutions in terms of lighting, acoustics, ventilation, and structural behaviour. With the introduction of a rotating brick guide fitted with a protractor to track the exact angle of each block, variations in porosity and complex surface patterns have been achieved. Ultimately, with the insertion of a second hinge along the main arm, it has been possible to subdivide the dome into a variable number of convex and concave lobes of varying dimensions and degrees of swelling, hence creating buttresses, niches, and isolated environments. The endless formal solutions that are made possible thanks to the new compass open the structure to external contingencies, moving away from the limitations of the original geometric primitive. This expanded regime offers often surprising formal possibilities and design opportunities, and further evolution can be expected due to the incorporation of developments in the field of robotics. The research conducted at ETH by Fabio Gramazio and Matthias Kohler suggests, for example, that the use of drones can allow for higher regimes of flexibility and accuracy of control. However, the lesson offered by great masters of the past shows the vanity of formal virtuosity if an ethical horizon is missing. As a plethora of virtuous performers and apologists of the techno-sciences testifies, this constitutes an urgent aesthetic and political matter. If, as Marx pointed out, virtuosic performance is either free or servile, that is, either revolutionary or functional to the dominant regime of signs, the virtuoso’s activity risks to have no other product than the execution of work and achieve no other objective than public recognition. Virtuosity belongs to the public realm and shares with political actions a “sense of contingency” that involves “the immediate and unavoidable presence of the other”(2). Its emptiness is openness and is immediately filled by the contingent. To explore the contingent, to create the collective, and to eventually contribute to “the invention of a people”(3) is today the virtuoso’s task.

1 Felix Guattari, Molecular Revolution - Psychiatry and Politics (Penguin Books, 1984) 2 Paolo Virno, A Grammar of the Multitude, For an Analysis of Contemporary Forms of Life (Semiotext(e) Foreign Agents Series, 2004) 3 “Art must take part in this task: not that of addressing a people, which is presupposed already there, but of contributing to the invention of a people.” Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2. The Time-Image (University of Minnesota Press, 1986)

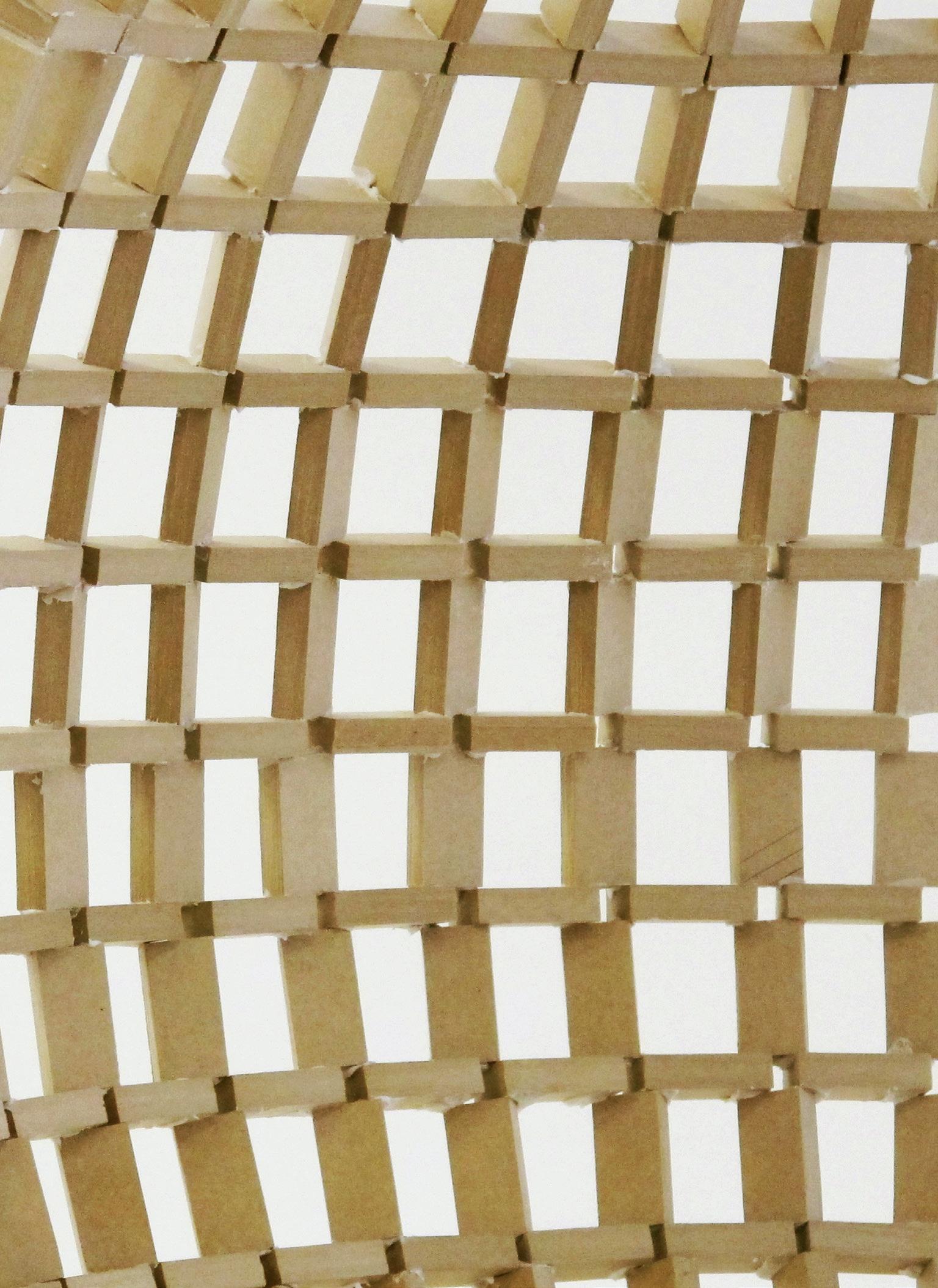

UTDT EAEU, Programa en Arquitectura y Tecnología 2014, Seminario Taller. Mind the Gap Patterns, modelo material, sector

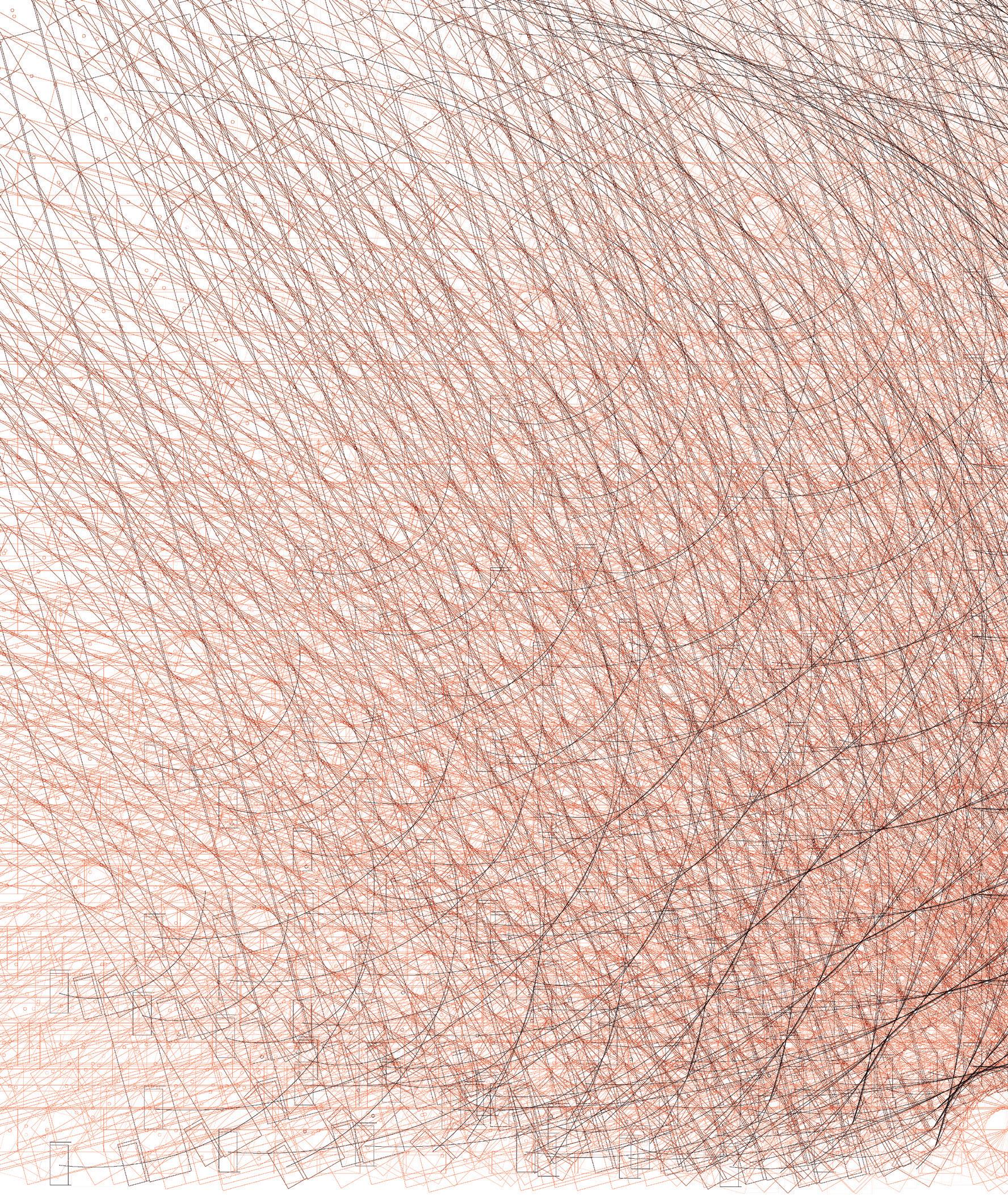

Matriz de dispositivos de control geométrico. Dibujo de Ciro Najle, Francisco Cadau, Victoria Della Chiesa