QUEST

The Inaugural Issue

FEATURED TOPICS

COACHING & PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNERS

ISLAMIC EDUCATION

LEARNING & ASSESSMENT

AI & DIGITAL LEARNING

JOURNAL OF EDUCATION ACTION RESEARCH IN THE UAE

COACHING & PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNERS

ISLAMIC EDUCATION

LEARNING & ASSESSMENT

AI & DIGITAL LEARNING

This journal represents a significant step forward in our collective journey to enhance education through the practical insights and experiences of educators in the UAE. It stands as a testament to our belief that the most impactful educational improvements often emerge from the grassroots from the dedicated efforts of teachers committed to refining their practice for the benefit of their students.

Education action research is a powerful tool for professional development and institutional growth. By exploring the challenges and opportunities within their classrooms, educators engage in a reflective process that not only improves their teaching but also contributes to the broader educational landscape. This approach fosters a culture of collaboration, where educators learn from one another and elevate the quality of education as a community.

The commitment to this form of inquiry reflects a pursuit of excellence. Teachers engaged in action research are not content with the status quo; they actively seek out ways to improve, innovate, and adapt to the evolving needs of their students. This ongoing quest for improvement aligns with our broader mission to deliver education that meets the highest standards.

Underlying this process is a deep sense of responsibility and integrity. Educators who engage in action research do so with a commitment to ethical practice, ensuring that their work not only benefits their students but also upholds the principles of honesty and transparency.

‘Quest’ provides a platform for sharing these valuable insights, offering educators across the UAE and beyond the opportunity to learn from one another's experiences. The research featured here has the potential to influence educational practices and policies on a wider scale, driving meaningful change and contributing to the advancement of education in our region and beyond.

HAMMADEH

Board Member of Al-Futtaim Education Foundation Chairman of Deira International School Board & Universal American School Board

“In today's educational landscape, we face significant questions that demand urgent answers—questions that I believe are greater in scope and urgency than any time in the last 30 years.”

It is with great pleasure that I introduce the inaugural issue of Quest: The Journal of Education Action Research in the UAE. This journal aims to share and celebrate the spirit of enquiry and innovation in educational practices across the UAE.

In today's educational landscape, we face significant questions that demand urgent answers questions that I believe are greater in scope and urgency than any time in the last 30 years. Outdated curricula fail to meet the evolving needs of the twenty-first century, while pedagogical and assessment methodologies struggle to keep pace with modern educational objectives. The dawn of Artificial Intelligence poses both opportunities and challenges for teaching and learning, requiring thoughtful adaptation and integration into educational practices. Moreover, the impending crisis in teacher recruitment highlights the need for sustainable and effective strategies to attract, retain, and support educators who are the backbone of our educational system.

Quest features articles written by action-based researchers from the CEAR Research Schools Alliance. Over the last year, teachers across Dubai have engaged in school-based action research to develop their practice. Their work explores a wide range of critical issues from coaching and leadership to English Language Learners (ELL) provision showcasing actionable research findings that aim to enhance learning outcomes through evidence-based practices.

I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks to the Al-Futtaim Education Foundation Board for their unwavering support in the creation of CEAR. Their commitment to fostering educational excellence has been instrumental in advancing action research in UAE schools. It is also important to acknowledge and thank the University of Birmingham (Dubai) who have supported their researchers in designing and carrying out their research.

I invite you to delve into the insightful contributions within these pages. Whether you are a practitioner seeking innovative teaching methods, a researcher exploring new frontiers in education, or a policymaker advocating for evidencebased reforms, Quest aims to inspire and inform.

The Research School Alliance (RSA) is a collaborative network of schools in the UAE that have partnered with CEAR to advance educational practices through action research and innovation.

A special mention goes to the University of Birmingham Dubai’s Action Research Network for conducting insightful workshops on developing action research in schools, as well as to our industry connections for helping our researchers comprehend the broader implications of their work.

Sarah Smith, Deira International School

Introduction

This study considers the impact of using coaching as a professional development and reflection tool amongst educators. Using Deira International School as a case study, it assesses the benefits of coaching for middle leaders and teachers and the impact it has on the quality of teaching and learning. Often professional development offered within education can be generic and dictated for all teachers leaving little room for personalisation and ownership. This generalised approach to professional

development is supported by Knight (2019) who recognises that professionals are rarely motivated when they have little autonomy. A one-size-fits-all model of change rarely provides helpful solutions. Recognising this, Deira International School had begun to establish a coaching culture and looked at the opportunity to integrate coaching within their professional growth and reflection cycle to further enhance bespoke professional development for leaders and teachers, aiming to create a more personalised approach where teachers take ownership of their

development.

This study explores the impact of a facilitative coaching method on professional growth and the quality of teaching and learning, aligning with Knight’s (2019) advocacy for autonomy and tailored solutions in professional development.

Deira International School has adopted a facilitative coaching approach, which van Nieurweburgh (2012) characterises as ‘one to one conversation that focuses on enhancement of learning and development through increasing self- awareness and a sense of personal responsibility, where the coach facilitates self-directed learning of the coachee through questioning, active listening and appropriate challenge in a supportive and encouraging climate.’ This method empowers teachers to lead their professional conversations, engage in critical reflection of their practices and create their own path forward. The value of this approach is supported by Devine et al. (2013), who suggest that coaching is a powerful tool for personal change and learning. Central to this coaching approach is the facilitation of learning, which hinges on active listening, inquiry and provision of both challenge and support, skills that are pivotal for the successful implementation of the new approach to professional development at Deira International School.

Coaching is recognised for providing educators with time for reflection, focusing on individual priorities, offering a safe space for exploration, and delivering a personalised approach to leadership development (van Nieuwerburgh et al., 2020). Furthermore Sardar and Galdames (2017) believe that school leaders who receive coaching support report a perceived improvement in their performance. Knight (2019) reinforces this viewpoint, suggesting that the personalised nature of coaching is crucial for its success.

Therefore, the literature suggests that

coaching, as a personalised, reflective practice, is instrumental in fostering professional growth and enhancing the quality of teaching and learning.

Initially, all coaches received a two-day training course to equip them with necessary skills to facilitate quality and effective coaching conversations. To support the coaching process, coaching wheels were developed as a visual tool to aid reflection and discussion. These wheels incorporated elements related to high-quality teaching and learning and key attributes of effective teachers which aligned directly to the school’s priorities. All teachers were allocated a personal coach for the academic year. A professional growth cycle was created where coaches met their coachees for formal meetings at least three times throughout the year. These meetings were spaced out to allow for reflection and application of new strategies. Prior to each meeting, coachees would reflect on the coaching wheels, identifying both strengths and areas in which they could further develop. Additionally, coachees updated their Professional Development Padlet, a digital portfolio capturing their research, reflections, training and progress against their areas of development. Coaching conversations were conducted; focused on the reflection from the coaching wheels. These conversations were instrumental in pinpointing an area of focus for the next cycle, thereby fostering a continuous loop of reflection, dialogue and professional growth.

This study used a mixed method approach to gather data, with a questionnaire that was distributed to 56 staff members and analysis of quality assurance data based on 76 members of staff. The questionnaire utlised a scaled score to measure the impact of coaching on reflection and the development of teaching practice or leadership. The quality assurance analysis measured the percentage

of improvement within teaching and learning across an academic year.

Positive feedback was received from teachers regarding their coaching experience. They identified that the coaching conversations help them to reflect critically on their current practice and enables them to move their practice forward. The quality assurance shows a positive trend in teaching and learning data.

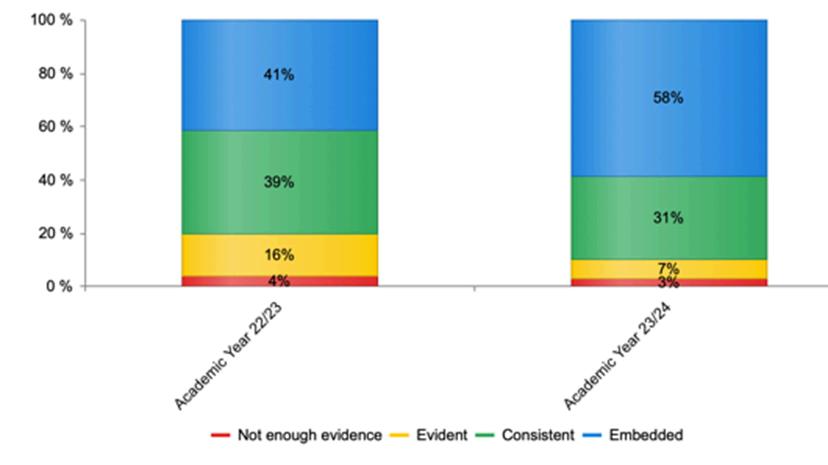

The quality assurance analysis indicated a 14% increase over a year in highly effective strategies for teaching and learning being embedded into lessons and an average rating of 4.11/5 from teachers regarding coaching’s role in enabling critical reflection and improvement in teaching practice.

Figure 1

Quality Assurance Data Analysis for the Academic Year 2022-2023 and 2023-2024

Figure 2

Scaled Score Analysis of Teacher’s Responses Regarding the Effectiveness of Coaching as a Reflection Tool

Figure 3

Scaled Score Analysis of Teacher’s Responses Regarding the Effectiveness of Coaching in Further Developing their Practice

Conclusion

The outcomes of the study confirm the value of coaching in educational settings, promoting a culture of reflective practice and continuous improvement. Limitations include the influence of various factors on teaching and learning data, the study’s focus on a single school with an existing coaching culture, and the variability in coaching consistency due to different coaching styles. Implementing a coaching program for professional growth has allowed for a more personalised approach, positively impacting teaching and learning for individual teachers. The study suggests that coaching is an effective tool for professional enhancement and reflective practice in education. Which is supported by the findings of Devine et al. (2013), van Nieuwerburgh et al (2020) and Sardar and Galdames (2017)

Devine, M., Meyers, R., & Houssemand, C. (2013). How can coaching make a positive impact within educational settings? Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 93, 1382-1389

Knight, J. (2019). Why Teacher Autonomy is central to coaching success. Educational Leadership, 77(3), 14-20.

Sardar, H , & Galdames, S (2017) School leaders’ resilience: Does coaching help in supporting headteachers and deputies? Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice, 11(1), 46-59.

van Nieuwerburgh, C (2012) Coaching in education: Getting better results for students, educators and parents London, UK: Karnac

van Nieuwerburgh, C., Barr, M., Munro, C., Noon, H., & Arifin, D. (2020) Experiences of aspiring school principals receiving coaching as part of a leadership development programme International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 9(3), 291-306

In the field of teacher education, the search for effective strategies to support student teacher development is ongoing. This case study explored the impact of a coaching style approach to feedback for International Postgraduate Certificate in Education (iPGCE) student teachers during school placements, examining how coaching feedback influences their progress and development.

The study aimed to determine if student teachers recognise coaching as a feedback style: if school-based mentors feel confident using coaching as a feedback style and if both students and mentors find coaching useful for the development of trainees. The sample consisted of four mentors and three student teachers, with data collected through questionnaires before and after mentors received coaching training (from The Educational Coach).

Before the training, the majority of participants had only a vague idea of what coaching entailed. Post-training, 100% could accurately define coaching and mentors reported a significant increase in their confidence in providing coaching feedback. This shift highlights the importance of adequate training in equipping mentors with the necessary skills to effectively employ a coaching approach.

Initially, student teachers preferred feedback that balanced encouragement with constructive criticism. After experiencing coaching, all student teachers identified coaching as the most helpful feedback style.

One student reflected:

“Coaching can be frustrating because sometimes we are just looking for someone to give us answers. However, what we learn through coaching feedback has a more lasting impact on our development.”

This shift demonstrates the benefits of coaching, aligning with Korthagen and Vasalos’ (2005) findings on the value of reflective practice.

Mentors initially acknowledged the potential of coaching but expressed concerns about student teachers' inexperience hindering their ability to generate ideas independently. Post-training, mentors observed that coaching fostered a greater sense of ownership and confidence in student teachers, as they actively engaged in reflection and critical analysis. This transformation supports Tschannen-Moran and Hoy’s (2007) findings that coaching benefits both new and experienced teachers.

The study revealed that with proper training, mentors could confidently implement a coaching style, and both mentors and student teachers recognised its value. The positive reception of coaching feedback by student teachers, and the increased confidence among mentors, suggest that integrating coaching into feedback mechanisms can significantly enhance teacher development.

Schools and universities linked with iPGCE programs could benefit from adopting coaching strategies and providing comprehensive coaching training for mentors. Future research should consider a larger sample size and a mixed-method approach to gain more in-depth insights.

The implementation of a coaching style approach to feedback has a profound, positive impact on the development of iPGCE student teachers. By fostering reflective practice, enhancing mentor-mentee relationships and boosting self-efficacy, coaching emerges as a powerful tool in the professional growth of future educators.

Korthagen, F A , & Vasalos, A (2005) Levels in reflection: Core reflection as a means to enhance professional growth Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 11(1), 47-71.

Tschannen-Moran, M , & Hoy, M W (2007) The differential antecedents of self-efficacy beliefs of novice and experienced teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(6), 944-956.

Helen Wallis, Deira

Professional growth and development are critical for sustaining high standards in education. One method increasingly adopted to foster this growth is coaching. Coaching involves personalised, one-on-one interactions aimed at developing an individual's skills, performance, and career progression This research article explores whether coaching encourages a professional growth culture within educational settings, focusing on the perceptions and experiences of staff at Deira International School (DIS)

development methods often focus on formal training sessions, while coaching provides a more individualised approach that can address specific needs and goals.

Deira International School has been implementing a coaching model for professional development, reflection, and growth for the past two years. Professional reflection coaching with the line manager focuses on pedagogical developments. Professional growth coaching, with a coach outside the department, focuses on individual growth and development.

The rationale for this study stems from the need to understand the effectiveness of coaching at DIS as a tool for professional development. Traditional professional development methods often focus on formal training sessions, while coaching provides a

more individualised approach that can address specific needs and goals. This study aims to evaluate if this personalised approach translates into a culture of continuous professional growth among staff, ultimately benefiting the educational environment.

This study utilised a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative data from surveys and qualitative insights from focus group interviews. The surveys were designed to measure staff perceptions of coaching, their sense of agency, and the impact on their professional development. Focus groups provided deeper insights into these perceptions and allowed for the exploration of themes that emerged from the survey data.

Participants included teachers and middle leaders from DIS. The survey used Likert-scale responses converted to numerical values for quantitative analysis, while the focus group discussions were transcribed and analysed thematically.

The survey data revealed strong support for the coaching system, with 82.2% of respondents agreeing that the coaching design at DIS effectively supports teachers in driving their own development. This high level of buy-in aligns with existing research that emphasises the necessity of staff engagement for successful professional development programmes (Blackman,

2010; Zwart et al., 2009).

Quantitative data showed that middle leaders had slightly higher mean scores compared to teachers regarding their engagement in professional growth. Newer staff members, with less than one year at the school, exhibited the highest enthusiasm for coaching, which may reflect their initial exposure to the system and its perceived benefits.

In terms of the nature of coaching, 93% of respondents agreed that coaching was collaborative and developmental rather than judgmental. This perception underscores the supportive environment that coaching aims to create, distancing itself from traditional evaluative methods

Focus group discussions provided deeper qualitative insights Staff members consistently highlighted the value of having dedicated time and space for reflection during coaching sessions. This finding aligns with previous research indicating that reflective practice is a key component of effective professional development (Day, 1999; Hargreaves, 1994; Harwood & Clarke, 2006).

However, the introduction of a second coach, who was not the staff member’s line manager, revealed some mixed feelings. While 77.8% of respondents felt safe voicing their views in these coaching conversations, this was a noticeable decrease from the 93% who felt positive about coaching with their line manager. This suggests that the trust and relationship built with direct managers enhance the effectiveness of coaching, highlighting the importance of carefully selecting and pairing coaches to ensure optimal comfort and openness.

An interesting finding was the discrepancy in perceived agency between professional growth coaching and professional development coaching. Only 71.1% of

respondents felt that professional growth coaching allowed them agency in their development, a decrease of over 10% compared to professional development conversations with their line managers. This suggests that while coaching is beneficial, its structure and the nature of the coaching relationship can significantly impact staff perceptions of their autonomy and empowerment. The decrease in perceived agency indicates a potential area for improvement in the coaching model. It underscores the need for further investigation into how different coaching frameworks affect staff's sense of ownership over their professional growth. Addressing this could involve enhancing the training for coaches to better facilitate agency and ensuring that coaching practices are consistently reviewed and refined based on staff feedback.

Overall, the results indicate that coaching fosters a professional growth culture, but its effectiveness is influenced by the specific implementation and the relationships involved. Ensuring that staff feel both supported and empowered through coaching is essential for maximising its benefits and fostering a culture of continuous professional development.

The study confirms that coaching fosters a professional growth culture at Deira International School, but several improvements can enhance its effectiveness. Coaching sessions with line managers are highly effective due to the established trust between staff members and their head of department. To improve, it is essential to ensure that line managers are involved and adequately trained to provide supportive, developmental feedback that aligns with the school’s goals for professional growth. Mixed feelings about non-line manager coaches highlight the need for careful coach selection. Coaches should be chosen based on their ability to build trust and offer constructive

feedback, with continuous professional development to enhance their coaching skills. The study also found a lower sense of agency in professional growth coaching compared to professional development coaching. To address this, coaching sessions should encourage teachers to take ownership of their development by setting personalized goals and leading discussions about their growth needs. Structured opportunities for reflection should be included in coaching sessions, using tools and frameworks that help teachers critically evaluate their practices and identify areas for improvement. Regular feedback from participants is crucial for the iterative improvement of the coaching process. Soliciting this feedback and conducting periodic evaluations of the coaching programme’s impact on professional growth and student outcomes will ensure that the programme remains responsive to the needs of the staff. Additionally, fostering a collaborative coaching environment by organising group coaching sessions or peer observations can enhance the overall impact of coaching by creating a supportive network among teachers.

In conclusion, while coaching is effective at Deira International School, focusing on trust, empowerment and continuous feedback will maximise its benefits, creating a more supportive and effective professional development environment.

Blackman, A. (2010). Coaching as a leadership development tool for teachers. Professional Development in Education, 36(3), 421–441.

Day, C (1999) Developing Teachers: The Challenge of Lifelong Learning London, UK: Falmer Press

Hargreaves, A (1994) Changing Teachers, Changing Times: Teachers’ Work and Culture in the Postmodern Age London, UK: Cassell

Harwood, T , & Clarke, J (2006) Grounding continuous professional development (CPD) in teaching practice. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 43(1), 29–39

Zwart, R C , Wubbels, T , Bergen, T , & Bolhuis, S (2009) Which characteristics of a reciprocal peer coaching context affect teacher learning as perceived by teachers and their students? Journal of Teacher Education, 60(3), 243-257

any, this point will ‘ring true’ and sents the perception of teachers and s in schools worldwide (Badri et al., If this sounds familiar, consider the ing: Shanghai, Hong Kong, Singapore ritish Columbia are recognised as the ighest attaining institutes worldwide. do they have in common? Professional opment is placed as the number one area for school improvement plans and hool improvement is built from PD. ning bodies, policy makers and leaders a clear message to these schools: student ng is what matters most, effective ssional learning is the best way to ve student learning, and evaluation and ntability will help embed the ssional learning in schools and ensure ality (Jensen et al., 2016).

anded as ‘CPD Pathways’, six action rch areas have been identified by the l leadership team based on feedback he Dubai School Inspection Board inspection in 2024 and emerging s that have been identified throughout hool year. A combination of middle and leaders have been selected to plan, ment and lead these six action research ts. All teaching staff will be part of this t, where each participant will make own choice for the ‘pathway’ they would like to contribute towards and will actively participate in research that will present tested suggestions that contribute towards the school development plan.

Action research and PD are naturally entwined, as effective PD is powered through prior research and the findings and suggestions of others (Whitworth & Chiu, 2015). Research group leaders will have 4 x 90-minute internal PD sessions to guide the group members through the project. Each session has been planned to supplement specific stages of the research project. The launch session will explore pre-existing literature and narrow down the specific research question, and later sessions will consider the method, data collection, result analysis and concluding points, along with future suggestions. Each internal PD session will be supplemented by the group members using time throughout the school day to action next steps in the research project and collect data.

This model generates smaller group sizes, which in-turn create a university ‘seminar style’; increase accountability, are driven by middle leaders; and allow staff choice. It is predicted that this will create a PD structure with high staff engagement during the internal PD sessions as well as increasing the contribution of staff completing PD taking place throughout the school day.

71 primary classroom and specialist teachers will participate in the study. Group sizes range from 10-15 participants, based on the choices that the participants made for the action research pathway which was of most interest to them.

Whilst each of the six action research studies will collect data in a variety of

Figure 1

methods, this study, focussing on the use of action research to support engagement in whole school PD, will use survey results collected before and after the action research projects and post study one-to-one appraisal meetings to review the perception, engagement and impact of this approach to PD.

Prior to the action research project, a staff CPD survey was completed by 71 primary classroom and specialist teachers.

Figure 1 demonstrates that prior to the action research (AR) project 81% of teaching staff found the current model for internal PD to often provide engaging sessions. This number remained the same after the AR project, however the percentage of teachers who acknowledged internal PD to ‘always’ be engaging rose by 8%, to reflect 25% of all staff responses. Of the 13 responses which reflected ‘sometimes’ or ‘rarely’, 11 of these responses came from Arabic or Islamic teachers and remained the same both prior to and following the AR project.

Figure 2 highlights that PD was recognised as having an impact by 86% of staff prior to the AR and by 88% of staff after the AR project. A larger percentage increase can be observed between the number of staff who perceived PD as ‘always’ having an impact on their teaching, which rose from 15% to 27%.

Figure 3 demonstrates that a small minority of staff (14%) ‘often’ completed PD throughout the working day prior to the AR project. This number increased to 28% following the AR project. Additionally, there was a reduction in the number of staff who ‘rarely’ completed PD (25% prior to AR, 14% post AR).

Staff responses when asked: ‘Do you feel engaged during internal PD sessions?’

Figure 2

Staff responses when asked: ‘Do you feel that internal PD has an impact on your teaching practice?’

Figure 3

Staff responses when asked ‘How often do you complete PD outside of the internal PD allocated slot?’

In preparation for the end of year one-toone appraisal meetings staff completed a selfperformance review. Within this they were asked to reflect on their PD. A significant number of staff identified that the AR project had impacted on their teaching practice and reflected on this as “one of the highlights of the academic year”, as well as “bringing energy and passion to post-inspection, term 3 " . Furthermore, responses indicated that staff “enjoyed the opportunity to be part of a project with a whole school impact” and others reflected that they preferred the smaller group size PD, as opposed to whole school, as it helped to “increase their active engagement” and “prevented them relying on others to answer questions”.

Conclusion

It is evident from the results that this model of PD has had a positive effect on staff engagement in PD; the impact of PD on staff teaching; and encouraged staff to complete PD outside of the allocated weekly timeslot. A significant contributing factor in this seems to be the preference of staff to complete smaller group PD sessions, as opposed to whole school PD (Guskey & Yoon, 2009). The results also support the work of (Jensen et al., 2016)) who suggests that middle leaders should be utilised as they are key

drivers for internal PD, becoming the link between the aims of the leadership team and the realities of the classroom teachers. This is most notable in the increased percentage of staff who ‘often’ completed PD throughout the school day and not only in the weekly allocated PD slot.

The opportunity for staff to contribute directly towards whole school initiatives has also supported an increase, particularly with reference to the frequency of PD taking place throughout the school day. Recognising that the AR they are completing is having an effect on themselves and colleagues helped to engage staff to consider, in depth, the different steps and suggestions they would make about their specific action research projects.

Badri, M , Alnuaimi, A , Mohaidat, J , Yang, G , & Al Rashedi, A (2016) Perception of Teachers’ Professional Development Needs, Impacts, and Barriers: The Abu Dhabi Case Sage Open, 6(3)

Guskey, T. R., & Yoon, K. S. (2009). What Works in Professional Development? Phi Delta Kappan Magazine, 90, 495 - 500

Francis, E M (2016) Professional development: A wicked problem LinkedIn. Retrieved from https://www linkedin com/pulse/professional-development-wickedproblem-erik-m-francis

Jensen, B , Sonnemann, J , Roberts-Hull, K , and Hunter, A (2016) Beyond PD: Teacher Professional Learning in High-Performing Systems. Washington, DC: National Center on Education and the Economy

Whitworth, A , & Chiu, J (2015) Professional Development and Teacher Change: The Missing Leadership Link. The Journal of Science Teacher Education, 26(2), 121-137.

Roua Alhalawani, Hartland International School

Introduction

Acquiring proficiency in a new language is a multifaceted journey that extends beyond the classroom. For English language learners (ELL), this journey is often marked by unique challenges and opportunities. A key factor affecting the learning paths of ELL pupils is the decision to withdraw them from certain classes to provide language support sessions, aiming to boost their

language proficiency. These intervention sessions lay the foundation for developing English language skills, enabling pupils to engage and succeed in the mainstream curriculum. This article examines the impact of ELL class withdrawals on their language proficiency.

The small-scale study explores Year 9 English language learners’ experiences and feelings associated with class withdrawal at Hartland

International School, located in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. The English as an Additional Language (EAL) department provides ELL sessions in place of Modern Foreign Languages (MFL), Arabic (if exempt), and Prep period to language learners who are new to English or developing their English competency. Ultimately, the outcome of this study aimed to offer practical insights to enhance teaching practices and support mechanisms for

pupils in ELL programs, as well as their integration into mainstream subjects.

To begin with, EAL/ELL is not an assessed subject, nor does it hold the status of a mainstream subject in the national curriculum. In Leung and Davison's (2001) terms, ELL is described as “a diffuse curriculum area” meaning that it is integrated across various subjects and aspects of school life. Also, ELL pupils are not a homogenous group; factors such as “first language development, culture, ethnicity, previous schooling history, and socioeconomic status” must be considered (Department for Education and Skills, 2007).

Trzebiatowski (2017) explains that ELL pupils can feel safer and valued in small group interventions also known as class withdrawal sessions. Gardner (2007) identifies four stages in the development of second language acquisition: elemental, consolidation, conscious expression, and automaticity and thought. The final stage, automaticity and thought is applied when the learner thinks in the language they are vocalizing. ELL intervention sessions can assist in reaching the automaticity and thought phase.

Vygotsky (1986) argued that “what one can do in cooperation with others today, one can do alone tomorrow.” In an ELL classroom, learners might initially struggle to articulate their understanding of new concepts in English. However, through interactions with ELL teachers, pupils can acquire the language skills needed to express their comprehension effectively.

What is the impact of class withdrawal on pupil progress and language proficiency?

The sample of this research study consisted of 13 Year 9 pupils who responded to an anonymous survey. The survey comprised 15 questions, including a mix of openended and closed-ended questions. Most questions were multiple-choice to facilitate responses from language learners. The survey was conducted during an afternoon lesson in Term 2. The questions were thoroughly explained before the pupils completed the survey independently.

Feedback from Pupil’s ELL experience included:

“I am happy that I do not attend some subjects and attend ELL instead.”

“I think I need to continue but reduce it slightly. Since I need to practice writing skills.”

“It is great but would like to attend 2 French classes and 2 ELL classes instead.”

“I want to have more ELL lessons because I want to prove my skills.”

“I would like more speaking lessons and more practical vocabulary. I want to read more in lessons and analyze it, Write more essays and WHW paragraphs.”

A key factor affecting the learning paths of ELL pupils is the decision to withdraw them from certain classes to provide language support sessions, aiming to boost their language proficiency.

“I think it is helpful for students who has some problems with language. For me it is good, because I never studied in British Schools.”

“My English is improving gradually and if you compare my English level now with the one I came to Hartland with, I think it has improved a lot.”

“It’s a really informed English class for people that has to learn English. I will encourage people to come in ELL about their learning.”

Participants viewed class withdrawals as an immediate and positive approach to tackling the language barrier. Some participants believe that increasing the number of language support sessions will improve their outcomes in mainstream integration. There were different views on the duration of class withdrawals, some wanted less, and others wanted more. Furthermore, participants identified speaking lessons as the most enjoyable. Listening and writing lessons were ranked as the second most enjoyable. Most notably, writing lessons were identified as the area with the greatest improvement, significantly aiding ELL pupils in developing their English language skills. Additionally, vocabulary was ranked as the second-highest level of improvement.

However, roleplays, online reading, and mini-projects received fewer votes. Overall, the responses indicate that ELL sessions are a strong supporting mechanism, enhancing pupils' confidence and motivation to succeed linguistically and academically. It is essential to continue praising and motivating pupils’ linguistic and academic progress as they may use their language barrier as an excuse for underachievement in the mainstream (Mistry & Sood, 2012).

The study offered valuable insights into pupils’ perspectives, highlighting their strengths, concerns, and needs. Notably, it helped inform tailored support and promoted crossdepartmental communication and collaboration. WongFillmore (1985) suggests that teachers must try to scaffold and break down their language instructions to avoid pupils’ constraints of learning the second language. Graf (2011) states that the most effective ELL provision involves partnership teaching between language specialists and classroom teachers. Every mainstream teacher contributes to literacy development. Integrating SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound) language objectives into lesson plans is strongly recommended. ELL specialists are encouraged to

share exemplary speaking, writing, and vocabulary tasks across mainstream subjects to support ELL integration. Furthermore, this research study has guided the development of more rigorous ELL exit writing criteria, focusing on transcription, grammar and vocabulary, punctuation, overall text and structure, presentation, and evaluation and improvement. This writing criteria outlines SMART objectives designed to improve writing skills in ELL by targeting specific areas that require improvement. Applying these writing criteria in mainstream classes can enhance writing skills, ensuring that language improvement strategies are integrated across all subjects, ultimately contributing to achieving high standards in writing proficiency. Lastly, this research study had its limitations. For instance, with only 13 respondents, it may have lacked sufficient statistical power to draw robust conclusions or generalize findings to a larger population of English Language Learners (ELLs).

The effectiveness of class withdrawals for academic development and English proficiency was explored from the pupils’ perspectives. The responses suggest that class withdrawals positively

Figure 1

Pupils' responses on ELL activities, home study, and practice frequency

Pupils’ feedback on their favourite aspects of ELL lessons

impact ELL pupils' language acquisition and development, though the reasons, individual preferences, and attitudes toward learning may vary. This research study has offered practical insights to improve teaching practices and support mechanisms in ELL and mainstream subjects, particularly focusing on enhancing writing proficiency. Based on this research study, it is worth exploring other research topics related to this area, such as teachers’ perspectives on ELL provision and mainstreaming ELL pupils, developing and testing EAL training for classroom teachers at GCSE level, and assessing ELL pupils’ readiness to succeed without language support.

Department for Education and Skills (2007). Secondary National Strategy for School Improvement. Ensuring the Attainment of Pupils Learning English as an Additional Language A Management Guide London, UK: Department for Education and Skills

Gardner, R. C. (2007). Motivation and second language acquisition. Porta Linguarum, 8, 9-20

Graf, M (2011) Including and Supporting Learners of English As an Additional Language. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Leung, C , Davison, C (2001) “England: ESL in the Early Days ” In Leung, C , & Davison, C , & Mohan, B (Eds ), English as a Second Language in the Mainstream, Teaching Learning and Identity (pp 153–165). Harlow: Longman.

Mistry, M & Sood, K (2012) Raising standards for pupils who have English as an Additional Language (EAL) through monitoring and evaluation of provision in primary schools, Education 3-13, 40(3), 281293.

Trzebiatowski, K (2017) EAL: Excluded by Inclusion Retrieved from: http://valuediversity-teacher co uk/eal-excluded-by-inclusion/

Vygotsky, L. S. (1986). Thought and Language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

Wong-Fillmore, L W (1985) Second language learning in children: A proposed model. In R. Esch & J. Provinzano (Eds.), Issues in English language development (pp 33-42) Rosslyn, VA: National Clearinghouse for Bilingual Education

Joanna Galvin, Hartland International School

Action Research Overview

This study addresses the challenge of linguistic complexity in math assessments for English Language Learners (ELLs). Complex vocabulary and sentence structures in math exam questions can hinder ELL comprehension and performance (Abedi & Lord, 2001). This problem is significant because it potentially undermines the accurate assessment of ELLs' mathematical abilities, leading to underperformance that doesn't reflect their true capabilities. By investigating the impact of simplified math language on ELL performance, this research aims to identify effective strategies for enhancing ELL understanding and academic achievement in mathematics.

The study was conducted at Hartland International School, focusing on Year 8 ELL students. The problem of linguistic complexity in math assessments is ongoing and significant, as it affects ELLs' ability to demonstrate their mathematical knowledge accurately. If not addressed, this issue may continue to create barriers for ELLs in math

education, potentially leading to lower academic performance and reduced educational opportunities. By simplifying the language in math exam questions, we aim to benefit ELL students by allowing them to better showcase their mathematical abilities without being hindered by language barriers.

Previous research has highlighted the impact of linguistic complexity on ELL performance in math assessments. Abedi and Lord (2001) found that complex vocabulary and sentence structures are major obstacles for ELLs in understanding and solving math problems. Language simplification strategies, such as using familiar words, short sentences, and active voice, have been shown to enhance ELL understanding (Abedi & Lord, 2001; Robertson, 2011).

Additionally, providing language support through visual aids, manipulatives, and glossaries can support ELL comprehension and achievement (Robertson, 2011). The integration of content and language is crucial, with collaboration between teachers and ELL specialists being essential in simplifying

question language while preserving academic rigor (Alt et al., 2014; Robertson, 2011). Providing supplementary language resources and instruction can further support ELL understanding and performance in math assessments (Robertson, 2011).

This study employs action research to address the problem of linguistic complexity in math assessments for ELLs. Action research is particularly suitable for this context as it allows for direct implementation and evaluation of language simplification strategies in a real classroom setting, promoting immediate benefits for students and enabling iterative improvements based on feedback.

How does the linguistic complexity of math exam questions affect ELL comprehension and performance? What specific language simplification strategies are most effective in enhancing ELL understanding and achievement? How can teachers implement language simplification in math exams while maintaining content rigor?

The research involves administering both original and language-simplified versions of math exams to Year 8 ELL students. Thinkaloud sessions with ELLs are conducted to gather qualitative data on their thought processes while solving problems. Additionally, quality assurance discussions with the Math department ensure that the simplified assessments maintain content rigor. The study focuses on Year 8 ELL students at Hartland International School.

Data Collection

Data was collected through: Administration of original and languagesimplified versions of math exams.

Think-aloud sessions with ELL students. Quality assurance discussions with the Math department.

The analysis includes:

Quantitative analysis of exam scores (limited due to small sample size and assessment window constraints). Qualitative analysis of think-aloud student feedback and teacher reflections. Comparison of original and simplified exam questions, quality assured by the math department.

While the study is ongoing, preliminary results indicate: ELLs performed significantly better on language-simplified math exams. Teachers reported increased ELL student confidence with simplified exams. Effective simplification strategies were identified and compiled into a comparison chart, which was positively received by the math department.

The preliminary findings align with previous research on the impact of linguistic complexity on ELL performance (Abedi & Lord, 2001). The results suggest that language simplification can be implemented without compromising math content.

The simplified exams may benefit not only ELLs but also struggling native English speakers.

Ongoing collaboration with the math department is crucial for implementation. Some students have requested that tier 3 subject-specific vocabulary not be simplified, as they feel they will have to learn it twice (e.g., probability/chance).

Language simplification in math exams can significantly enhance ELL understanding and academic performance. Teachers and ELL specialists can adopt effective simplification strategies while maintaining content rigor. However, the study has limitations, including a small sample size limited to one year group and a limited time frame to show significant increases in performance. Future actions include:

Ongoing collaboration with the math department on termly assessments.

Support with assessment design.

Collaboration with other departments using the same model throughout the next academic year.

Abedi, J., & Lord, C. (2001). The language factor in mathematics tests. Applied Measurement in Education, 14(3), 219-234.

Alt, M , Arizmendi, G D , & Beal, C R (2014) The relationship between mathematics and language: Academic implications for children with specific language impairment and English language learners Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 45(3), 220-233

Robertson, K. (2011). Math instruction for English language learners. Colorín Colorado. Retrieved July 17, 2024, from https://www colorincolorado org/article/math-instruction-english-language-learners

Marwah Tarabichi, Deira International School

This action research investigates the effectiveness of various memorisation strategies on Quranic verse memorisation among Year 6 non-native Arabic speakers. The problem addressed is the challenge faced by non-native speakers in memorising the Quran, an essential component of Islamic education. This research is crucial as it seeks to identify strategies that can improve memorisation despite language barriers, enhancing educational outcomes and student engagement.

At Deira International School, Year 6 nonnative Arabic speakers often struggle with Quran memorisation due to language barriers. This problem is ongoing and affects students' ability to meet curriculum requirements. Without intervention, students may continue to face difficulties, leading to disengagement and poor academic performance in Islamic studies. Effective memorisation strategies can bridge this gap, benefiting students by improving their memorisation skills and fostering a better understanding of the Quran.

Previous studies highlight the importance of repetition and the use of audio-visual aids in language learning (Al-Harbi, 2020; Roediger & Butler, 2011). Gamification has also been explored as a motivational tool in education (Deterding et al., 2011). However, the specific impact of these strategies on Quran memorisation among non-native speakers remains under-researched. This study aims to fill this gap by comparing rote learning and gamification techniques.

Methods

Action research was chosen for its practical approach to solving educational problems. The research questions are:

1.

What specific memorisation strategies are effective in enhancing Quranic verse memorisation?

2.

How do student perceptions of memorisation techniques align with empirical findings in the literature?

3.

How do individualized approaches address students' unique challenges in Quranic memorisation?

The study involved 28 Year 6 non-native speakers. Initially, students completed a survey to assess their current memorisation status and challenges. The research comprised two cycles: the first using rote learning (listening and repeating verses), and the second using gamification (Quizizz for arranging transliterated words). Each cycle lasted two weeks, and the number of verses memorised was recorded at the end of each cycle.

The participants were 28 Year 6 students at Deira International School, all non-native Arabic speakers. The sample was chosen to represent a typical classroom environment where students face similar memorisation challenges.

Data were collected through pre- and post-intervention surveys, observations, and the number of verses memorised during each cycle. Qualitative feedback was also gathered from students regarding their perceptions of the effectiveness of each strategy.

Quantitative data were analysed by comparing the average number of verses memorised across different strategies. Qualitative data were examined to understand student preferences and perceived effectiveness of the strategies. The analysis aimed to identify the most effective memorisation techniques.

Figure 1 Student Preference of Rote Learning vs. Gamification

Table 2

Analysis of Rote Learning vs. Gamification

Quantitative analysis showed that students memorised an average of 1.17 verses using rote learning, compared to 0.31 verses using gamification. Qualitative feedback indicated a preference for repetition (32%) over gamification (21%). These results suggest that rote learning is more effective for Quran memorisation among non-native speakers.

The findings align with existing literature that supports the efficacy of repetition and audiovisual aids in memorisation (Al-Harbi, 2020; Roediger & Butler, 2011). However, the study also revealed a divergence between student perceptions and actual efficacy of gamification, suggesting a need for further exploration of this strategy. The research highlighted the importance of consistent and structured intervention sessions to maximise effectiveness.

Quran memorisation among Year 6 non-native speakers is most effective using the rote learning technique. While gamification did not significantly enhance memorisation, it holds potential for improving retention. Future research should explore additional gamification techniques and focus on retention strategies. This study contributes to improving teaching methods and curriculum development in Islamic education.

Al-Harbi, A. S. (2020). The impact of audio-visual aids on pronunciation and retention among young learners Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 23(1), 112-120

Deterding, S , Dixon, D , Khaled, R , & Nacke, L (2011) From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining “gamification”. In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments (MindTrek ’11) (pp. 9-15). New York, NY: ACM.

Roediger, H L , & Butler, A C (2011) The critical role of retrieval practice in long-term retention Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15(1), 20-27

Exploring effective pedagogical methods and practices and developing fair and comprehensive assessment practices

Abigail R. Gardiner, Deira International School

One of the aspects of teaching with the highest impact is the cycle of feedback, during which teachers give information to students about their performance, relative to defined targets and learning outcomes. Within this aspect, it has been found that all methods of feedback delivery are highly effective (Educational Endowment Fund, 2021), however it is important that feedback is “timely, specific and actionable” (Hattie & Timperley, 2007).

With not only the students’ progress as a priority, it is also essential to take into consideration that within our school, as well as the culture of schools in general, it is often fed back that teachers feel overwhelmed by the marking that is required in terms of written feedback; therefore, influenced by prior research and inspired by other schools within out community, it was decided as a school that, in order to have a higher impact on both the

improving pupils’ progress and reducing teachers’ workload, it would be beneficial to begin to implement verbal feedback in our school.

A forward-thinking school in the United Arab Emirates that is a pioneer of developing pedagogical practice, Deira International School prides itself on being open to adapting traditional teaching ‘norms’ to suit the needs of both teachers and students. Historically, teachers within the school have found it difficult to meet the expectations of written feedback and have questioned its value when there is often limited time within the curriculum for next steps to be completed.

With the successful implementation of a marking policy centred around verbal feedback, both the children and teaching staff will benefit, the intention being that teachers providing support and challenge in the moment will allow children to make more rapid progress towards and beyond Age Related Expectations; additionally, we would see a positive impact on teachers’ well-being once the policy has been successfully implemented across the school.

Identified as the most suitable method in this study, action research allowed us to hone in on the specific issue, investigating and trialling ways to address and solve the problem, and subsequently acting on this for timely impact. Subsequently, the specific research questions were:

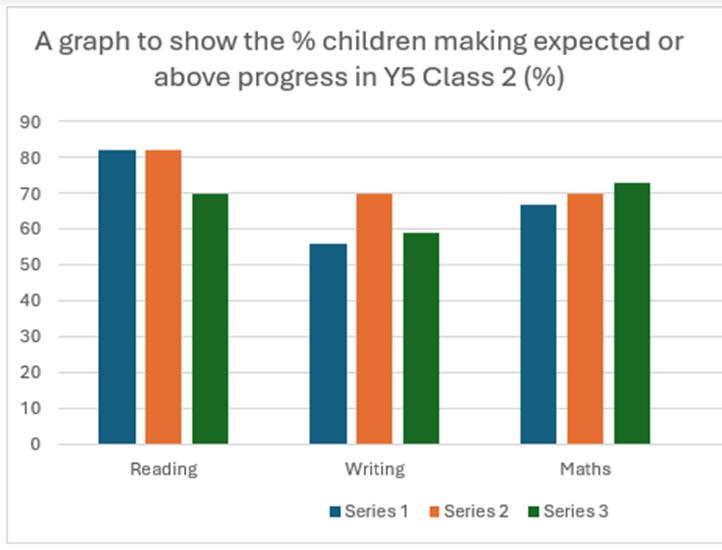

What is the impact of verbal feedback on children’s progress in Reading, Writing and Maths?

How can verbal feedback be integrated in a way to have the most impact on pupil progress?

Following the initial introduction, the working party then met on a three-week

cycle to review strategies and discuss and adapt practice based on which were the most impactful, would be adapted, modifying the Marking and Feedback Policy on a continual basis.

Each member of the Marking and Feedback party took a sample with which they trialed methods of verbal feedback, consisting of two Year 5 classes of 26/27 children and 10 children within the Islamic department of the school.

The methodology of this research incorporated both quantitative and qualitative data, in the form of online forms for both staff and students to complete and analysis of summative data. This was used to not only to assess the impact on children’s progress, but also to gain deeper insight into how the new strategies had impacted staff and students’ perceptions.

The data was then analysed by comparing the progress data of the two Year 5 classes at two points throughout the year, before and after the research project, subsequently reflecting on in which areas the implementation of verbal feedback had been most impactful and how other areas could be adapted. Additionally, children’s responses

with regards to receiving verbal over written feedback were positive:

“I like the verbal feedback system because I get to do it in time unlike the next step I usually don’t find it”.

or above expected progress throughout the academic year in class 2

The impact of verbal feedback on children’s progress across the year was overall positive but inconclusive between Term 2 and Term 3, which was the point at which verbal feedback was introduced. However, 100% of the children who responded to the survey responded to the question “Do you think that receiving verbal feedback helps you to learn and make progress?” with yes or sometimes, which demonstrates the positive impact it has had on children’s attitude to feedback.

Within the sample groups, children responded positively to verbal feedback, and in-class observations have shown that feedback is more timely and personalised,

with children making better progress within each lesson. As is the case in many aspects of learning, there is natural fluctuation within children’s progress across the year, which may explain why the results do not show significant positive impact on children’s

Figure 3: The % of children making expected or above expected progress throughout the academic year in class 1

progress. The time constraints of the study may also have limited the results; over a longer period, we would hope to see children making above expected progress.

Staff have also reacted positively to the impact verbal feedback is having on their workload, and next academic year, it may be beneficial to increase the number of staff members in the working party to further refine practise and discuss impact.

In terms of my own practice, feedback is much more personalised and my focus has shifted from making sure feedback is evidenced to ensuring that it is meaningful. With further refinement, others within the school will be able to draw on our knowledge and implement a more meaningful approach to feedback, as well as beginning to introduce coaching methods to support.

Education Endowment Foundation (2021) Feedback Retrieved from https://educationendowmentfoundation org uk/educationevidence/teaching-learning-toolkit/feedback

Hattie, J , & Timperley, H (2007) The Power of Feedback Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112

Emma Jones, Hartland International School

In the realm of secondary education, exam anxiety is a pervasive issue that affects a significant portion of students, with estimates ranging from 20% to 40% globally (von der Embse et al., 2018). This anxiety, characterized by physical, emotional, cognitive, and behavioral symptoms, can severely impair academic performance, leading to lower test scores and overall achievement (Segool et al., 2013). This action research investigates the potential of starter tasks to alleviate exam anxiety by easing students into the testing process, thereby improving their performance. Addressing this issue is crucial because high levels of test anxiety not only hinder academic success but also impact students' self-esteem and longterm educational outcomes. By exploring and implementing strategies to reduce exam anxiety, educators can create a more supportive and effective learning environment, ultimately fostering better academic and emotional well-being among students The significance of this problem is underscored by research indicating that high anxiety increases cognitive load and reduces working memory capacity, further exacerbating the challenges students face during exams (Owens et al , 2012) Therefore, understanding and mitigating exam anxiety is essential for enhancing student performance and overall educational experience. Recognizing that increased teacher workload and reduced instructional time are major concerns for educators, I chose to explore the use of starter tasks. Implementing new strategies often comes with the risk of additional demands on teachers or cutting into essential teaching time, both of which are

undesirable and challenging to manage. By integrating starter tasks, I aimed to find a balance that allows for addressing exam anxiety effectively without imposing extra burdens on teachers or sacrificing the comprehensive coverage ofthe curriculum. This approach ensures that the strategy is practical and sustainable.

As a secondary mathematics teacher at Hartland International School, I have observed firsthand the detrimental effects of test anxiety on my students. Many students report feelings of dread, mental blocks, and an inability to perform under exam conditions. They have regularly made comments that they can perform skills in class but not under test conditions and that their mind goes blank during testing, prompting me to investigate alternative factors that influence test performance outside of preparedness and mathematical ability Students display agitation around testing and regularly ask if a score will

By exploring and implementing strategies to reduce exam anxiety, educators can create a more supportive and effective learning environment, ultimately fostering better academic and emotional well-being among students.

contribute to their report grade, and visibly relax when the answer is no. Outside of my observations or student demeanor, I recorded test scores for my year 10 class that were lower than I expected from observing their interaction with material and work completed in class. Whilst indeed they were adjusting to GCSE standard of questions, the disparity between their classwork and test scores also encouraged me to evaluate the impact of exam anxiety on this class and explore methods that could mitigate it.

The prevalence of test anxiety is significant (von der Embse et al., 2018). Factors contributing to this anxiety include fear of failure, lack of preparation, high stakes testing environments, and pressure from parents and teachers (Putwain, Woods & Symes, 2010) and symptoms of test anxiety can be physical, emotional, cognitive, and behavioural, all of which can impair academic performance by increasing cognitive load and reducing the working memory capacity available for problem-solving during tests (Owens et al., 2012). Research indicates that test anxiety levels peak in middle adolescence and are generally higher in female students compared to male students (Hembree, 1988). Implementing strategies to reduce test anxiety is crucial for improving students' academic outcomes and their overall educational experience.

Research on test anxiety highlights several effective strategies for alleviating its impact on students.

Relaxation Techniques such as deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, and mindfulness meditation have been shown to reduce physiological symptoms of test anxiety (Rice et al., 2006).

Positive self-talk is a strategy which correlates with higher levels of selfesteem, better stress management, and improved academic performance (Burnett, 1999).

Study Skills Training enhances students' confidence by teaching effective study and time management skills, which can subsequently lower anxiety levels (Putwain & Best, 2011).

Practice Tests are another valuable tool; regular exposure to test-like conditions helps desensitize students to the testing environment, thereby reducing associated fears (Cassady & Gridley, 2005).

Starter Tasks simple, low-stakes activities at the beginning of tests can ease students into the testing process, reducing initial anxiety and mental blocks (Pekrun et al., 2002).

There were two stages to my investigation. Firstly, I surveyed several students across KS3 and KS4. This was to establish how prevalent exam anxiety was within Hartland International School and discuss student ideas on testing to identify formats which may work for effective exam-anxiety reducing starter tasks.

I then identified two formats for starter tasks. The first was silent closed-book tasks formally marked by peers using a mark scheme. This was designed to replicate the test experience. The second was informal starter tasks focusing on exam style problemsolving, a skill surveyed students said made them nervous in tests. Progress was monitored through post-test surveys which monitored anxiety levels and student perception of the strategy tried, and quantitative test results themselves.

My initial survey to identify the prevalence of exam anxiety asked 67 students (40 in Year 8 and 27 in Year 10) for their opinions. I then examined strategies with a focus group of my Year 10 mathematics class at Hartland International School. This mixed-ability group, targeting grades 5-8 at the GCSE level, and included 19 students 17 females and 2

males. The students in this group had previously demonstrated lower-thanexpected assessment scores and exhibited low confidence in test situations.

Year 8 and 10 were surveyed using a Microsoft teams form. Included in the form was the Nist and Diehl (1990) short questionnaire (Figure 1), which is designed to determine whether a student experiences a mild or severe case of test anxiety. The questionnaire scores range from 10 to 50, with a low score (10-19) indicating little to no test anxiety. Scores between 20 and 35 suggest the presence of some test anxiety characteristics, likely at a manageable and potentially beneficial level. Scores above 35 indicate a severe and unhealthy level of test anxiety, requiring attention and intervention. This tool is useful for identifying students who may need additional support to manage their test anxiety effectively. Questions were also asked to identify which situations considered a test, and how students perceived their ability and performance in mathematics.

Two testing formats were used with the year 10 focus group. The first was a 10-minute test done in test conditions at the end of a

lesson. Students sat a test before the first starter activity (peermarking) was trialed and after,

with change in scores tracked. They were also given a questionnaire before the trial and after. This included a variation of the Nist and Diehl questionnaire to track anxiety and asked student opinion of the starter task strategy itself. This survey also revealed that students did not take these unofficial 10minute tests as seriously as the official termly tests that would be reported on, and so I used the official termly test as the metric for quantitative tracking of progress for the second starter activity (problem-solving focus) moving forwards. Again, students were given a questionnaire before and after to track anxiety levels and opinions.

When analysing the initial student survey of students, I found that 17% of students across the two year groups are considered to have unhealthy amounts of test anxiety as per this testing metric.

When considering whether this is representative of both year 8 and year 10, I found the proportion of students with a score indicative of unhealthy amounts of test anxiety was similar in both (15% in year 8 and 22% in year 10). This indicates test anxiety is prevalent in Hartland International School across ages and regardless of whether students are undertaking an offical exam course.

2: Key Reasons for Student’s Test-Related Nervousness

After employing this strategy, there was what I consider to be a significant increase in test score although no significant changes to anxiety levels. This improvement in score may be because 87% of students found recall questions in starter tasks helpful for practicing exam techniques and 100 % of students found it beneficial to know how marks are allocated for these tasks. Low percentages of students (20-60%) indicated peer marking to be of value in replicating the text experience or encouraging better exam technique. Despite this, only around half of students (53%) felt able to apply skills learnt to starter tasks.

After employing this strategy, there was what I consider to be a significant increase in test grade although also a somewhat significant increase to anxiety levels. High proportions of students (79%+) saw the value in problem solving questions in starter tasks and wanted to do this more, despite identifying these as an area they lacked confidence in. Despite this, only just over half of students (57%) felt able to apply skills learnt to starter tasks

The student surveys indicate that starter tasks have been instrumental in increasing confidence with specific skills and techniques. A significant majority of students reported that these tasks helped them develop a better understanding of the subject matter and improved their exam techniques. This positive feedback is supported by improved test scores, showing that the strategies are effective in enhancing academic performance. However, despite these tangible improvements, students' self-belief in their ability to perform well in exams remains disproportionately low This disparity between the data and students' perceptions suggests that while starter tasks are beneficial, additional measures may be necessary to boost students'

confidence in their overall exam performance. Addressing this issue is crucial, as fostering a stronger belief in their abilities could further enhance students' academic success and reduce exam-related anxiety.

With academic successes in mind, I will of course continue to integrate effective strategies into my starter tasks. Recall will be a regular feature with discussion of mark schemes and mark allocation. I will aim to ensure I include a more difficult problemsolving question to encourage development of this I will not prioritise peer marking of work as the students did not express that they saw value in this

However, with anxiety scores largely remaining the same, if not rising, I need to take a more holistic approach to test taking and integrating strategies seen in class to the test environment I will place greater emphasis on linking starter tasks with actual exam scenarios, being even more explicit with my language, to help students make the connection between practice and performance. I also plan to take a more holistic approach, linking in with the wellbeing department in school so conversations around text anxiety and strategies to deal with it happen much earlier in the year. I will discuss in-test relaxation techniques and breathing exercises in class with students, so they are equipped with an anxiety toolkit to use if ever the nerves hit.

To summarise, students generally see the value in recall tasks during starter activities and gain confidence with key skills in that context. However, there is a struggle to connect starter tasks with exam performance fully. While grades have improved, anxiety levels have not significantly decreased, suggesting that while starter tasks are beneficial, they are not a complete solution to test anxiety.

Burnett, P C (1999) Children’s self-talk and academic performance Educational Psychology, 19(1), 79-89.

Cassady, J C , & Gridley, B E (2005) The effects of online formative and summative assessment on test anxiety and performance Journal of Technology Learning and Assessment, 4(1), 4-30

Hembree, R (1988) Correlates, causes, effects, and treatment of test anxiety Review of Educational Research, 58(1), 47-77

Nist, P. A., & Diehl, M. (1990). Test Anxiety Questionnaire. Retrieved from http://web.ccsu.edu/fye/teachingresources/pdfs/test anxiety questionnaire pdf

Owens, M , Stevenson, J , Hadwin, J A , & Norgate, R (2012) Anxiety and depression in academic performance: An exploration of the mediating factors of worry and working memory School Psychology International, 33(4), 433-449

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W., & Perry, R. P. (2002). Academic emotions in students' self-regulated learning and achievement: A program of qualitative and quantitative research Educational Psychologist, 37(2), 91-105

Putwain, D. W., & Best, N. (2011). Fear appeals in the primary classroom: Effects on test anxiety and test grade Learning and Individual Differences, 21(5), 580-584

Putwain, D W , Woods, K A , & Symes, W (2010) Personal and situational predictors of test anxiety of students in post-compulsory education British Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(1), 137-160

Rice, K G , Leever, B A , Christopher, J , & Porter, J D (2006) Perfectionism, stress, and social (dis)connection: A short-term study of hopelessness, depression, and academic adjustment among honors students Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(4), 524

Segool, N K , Carlson, J S , Goforth, A N , von der Embse, N , & Barterian, J. A. (2013). Heightened test anxiety among young children: Elementary school students’ anxious responses to high-stakes testing Psychology in the Schools, 50(5), 489-499

von der Embse, N , Jester, D , Roy, D , & Post, J (2018) Test anxiety: Effects, predictors, and correlates: A 30-year meta-analytic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 227, 483-493

Neil Brown and Mathew Prosser, Victory Heights Primary School

This article reviews an action research pilot study into how to effectively show children’s learning progress during the course of lessons at a British Curriculum primary school in Dubai, awarded Outstanding status by the Dubai School Inspection Board (DSIB), 2024. Whilst the school showed outstanding progress through its summative data and external assessments, it was noted by the inspectorate that it was not always clear whether, during the course of a lesson, children were making clear progress against the learning goals of that session. The Authors, along with the senior leadership of the school, believed this to be an important consideration and one which merited further investigation. By reflecting on what progress looked like in a lesson for teaching staff, the project also looked to consider how the pupils understood their learning goals and how they could reflect on their learning journey towards them.

The setting for this research was an independent private British-Curriculum primary school in Dubai, UAE, the school is a fee-paying school with 1006 children on roll for the academic year 2023/24. Specific consideration of how to judge progress within the context of a lesson had been discussed prior to this research project but no in-depth analysis had yet taken place.

The action research project considered multiple texts but cited the work of three in particular. These were: Unlocking student success: The power of success criteria,

relationships and clarity (Egan, 2023) which advocates the value of producing focused learning goals for each lesson and also the use of clear visuals to help children understand the progress they have made. How can we demonstrate rapid progress in our lessons? (Williams, 2016) which champions the effectiveness of well-embedded progress checks; and Top 5 tips to show progress in lessons (Sargent, 2015) which promotes the use of child-led progress checks supported by strong teacher questioning.

We chose to use Action Research as our research method as its flexibility offered us the ability to make changes throughout the pilot based on what we were observing. This was particularly useful during a short pilot such as this where any pause to reconsider a wholescale approach would have been costly in terms of data collection.

The project had 3 main areas of focus: Redefining Success Criteria- to be clear, concise and focused around a specific verb. These had to be easily and thoroughly understood by the cohort of pupils so they could ultimately review their learning progress against them within the context of the lesson.

Introduction of Pupil Pit Stopsdesignated checkpoints where children were asked to consider their progress against the Success Criteria (Learning Goals) of the lesson.

Use of a Reflection Visual- A simple template on which children could mark 3.

their perceived progress (against the specific Success Criteria) during the course of a lesson.

Our participants were:

4 Year 5 classes

Year 4 class

1 Year 3 class

1 Arabic class

1 Islamic class

1 Year 2 STEAM class

Foundation Stage 2 classes were also included in the pilot but with a focus on their assessed progress rather than their perceived progress Due to their age, FS children did not complete the data collection tasks and therefore are not represented in the data

Our data was the following:

Qualitative: Teacher Verbatim about the effect of the pilot study and Child verbatim about their experience of the pilot study.

Quantitative: Results form a short weekly impact survey completed by the children.

Our analysis focused on the returns of a weekly online survey which children completed at the end of each week of a 3week pilot period. The children were asked to provide a score out of 5 for the following questions:

1.

How well do you understand the ‘Working model’? This is an internal reflection model which represents different levels of understanding: Paddling - Emerging knowledge; Snorkeling- solid grasp of fundamentals; Diving - Expanding knowledge; Deep Sea Diving - Deep understanding with thirst for further learning.

2. How confident are you at showing 3.

How confident are you that you made progress against your Success Criteria?

progress using your Reflection Visual?

Any score of 4 or 5 was considered a ‘Promoter’. A score of 1 or 2 was considered a ‘detractor,’ whilst a score of 3 was considered ‘indifferent’. Children having confidence in being able to reflect and adjudge their progress would be high ‘promoter’ scores for each question by the end of the pilot period. This qualitative data was then supplemented by the consideration of child and staff verbatim which the project coordinators collected at the end of the project by asking the question “What are your thoughts about this research project?”