The Sumba community inhabit the Indonesian island called Sumba. Some of us work as farmers in the fields but, in my village, most are weavers. One of our cultural icons is the traditional fabric known as “tenun Sumba.” Every Sumba woman, during her free time after working in the fields, dedicates her daily routine to creating kain tenun Sumba.

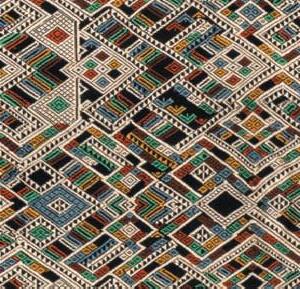

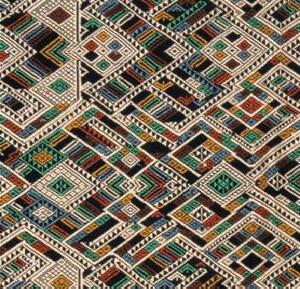

Its three common colors are red (from the Morinda root), blue (from indigo leaf extract), and black (from mud and color-binding concoctions). These three colors are fundamental to our daily life. Blue originates from the sky. Red symbolizes bloodshed. Meanwhile, black represents how life always has two sides, good and bad. Some motifs in our weavings stem from folk tales, like the motif of Ular Pakiku Iyang, which means “snake with a fish tail.” This motif originates from a story in the ancient Sumbanese community that depicts honesty. If you are a snake, you must be consistent as a snake—don’t be half snake and half fish.

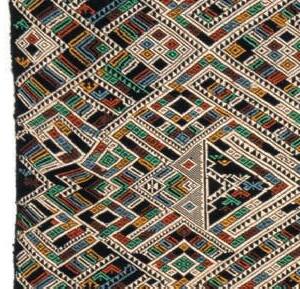

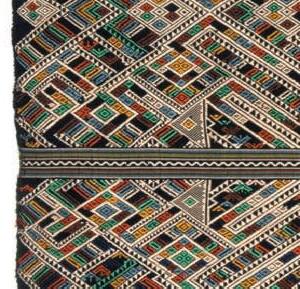

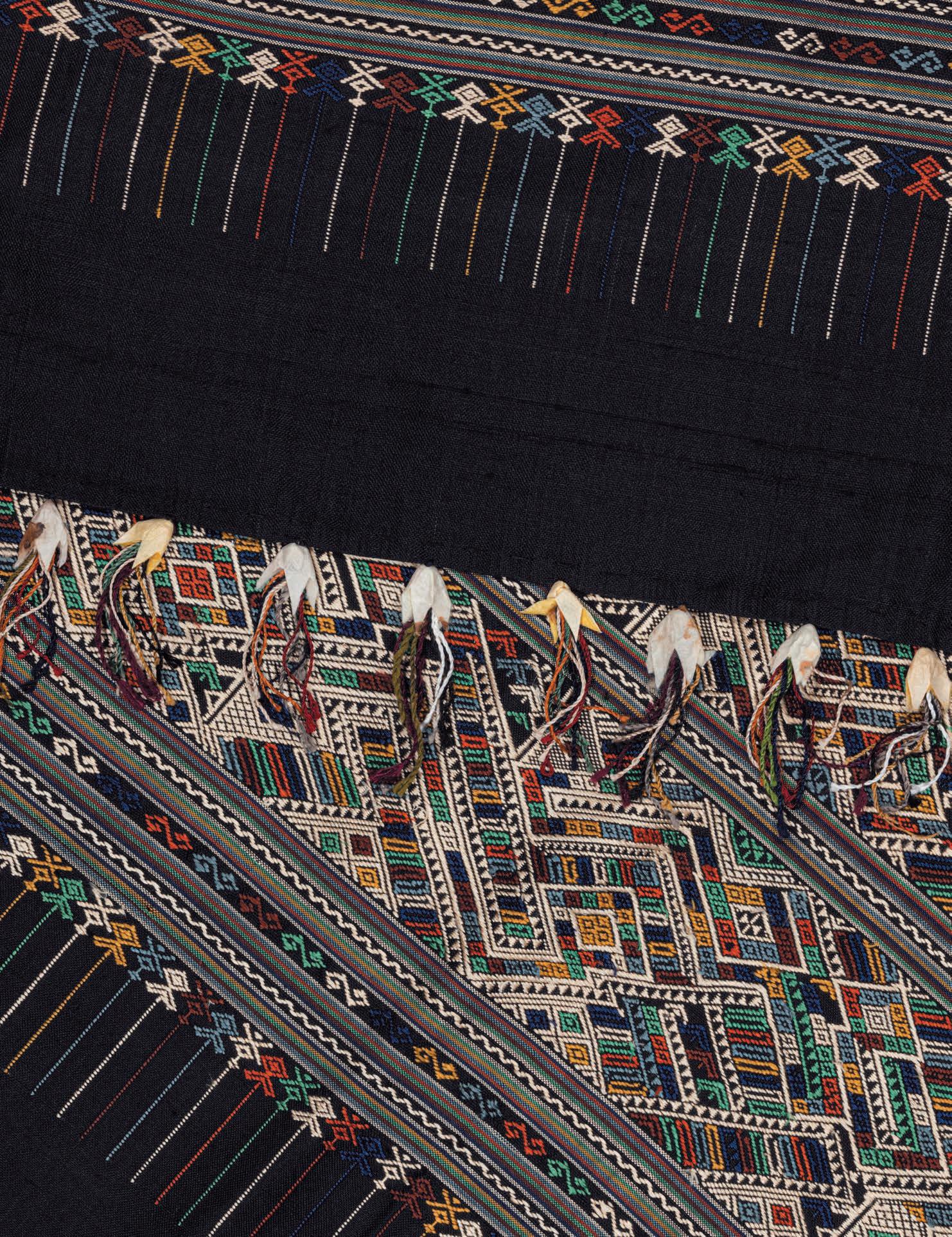

Sumba consists of four regencies: East, Central, West, and Southwest Sumba. I come from East Sumba—the one region where weaving is still a daily job—specifically from Raja Pau village. The distinctive technique used to make the Sumba sarong involves two types of weaving: ikat and songket. In ikat, the threads are tied and dyed according to a predetermined pattern before they are woven. On the other hand, songket uses a technique called pahikung, where the threads are lifted one by one to create a pattern using pre-arranged thin sticks. Hinggi, an ikat-weave garment, is typically worn by men, while songket weaving is commonly worn by women in the form of a lau (sarong). However, because of modernization, it’s common to see both men and women wearing hinggi or lau according to their needs, as practiced by designers.

Our woven fabrics originally came from Raja Pau and later spread to other regions. The primary factor behind this relatively rapid dissemination, in my view, is marriage. If a woman from Raja Pau village gets married elsewhere, her daily habits and routines automatically carry over to her new location. It’s from here that the pahikung technique began to be introduced in other areas and expanded, still within the realm of East Sumba. As a result, several motifs from different regions share similarities.

During the Dutch colonial period, Sumba woven fabrics were given as souvenirs by the local king to missionaries who visited the island. This explains why so many Sumba textiles have been found in collections in the Netherlands. In the 19th century, these textiles had no commercial value within Sumba itself. They were exclusively reserved for ceremonial use, such as weddings and funerals. The economic value of East Sumba woven fabrics began to become manifest when they were utilized for barter with Dutch traders, who recognized their quality and craftsmanship.

It can take up to one year to make a single piece, especially in the ikat technique. The natural dyeing methods require the fabric to be left in the open air for a long period after the immersion process so that the color can become richer. The same applies to the final fabric: the longer it is stored, the brighter the color will be.

Certain traditional motifs are considered both important and sacred. For example, in the ikat technique in East Sumba, there are three designs that have deep meanings. The first is the Ratu Wilhelmina motif, because it was created during the Dutch colonial era. The second, in the shape of a lion, served as a seal or stamp used for agreements and transactions between the Sumbanese people and the Dutch. The third is the Manumara motif, depicting a chicken flapping its wings. A leader or king can offer protection and guidance to the entirety of East Sumba society, resolving any issues through consultation and consensus. The fairness of the king’s judgment is represented by the chicken flapping both wings equally.

There is a motif shaped like a human figure raising both hands; its name is Namawulu Tau Nama Bakul Wamata, Nama Liabar Rukahilu, which means “God who sees and hears everything.” So, there is a religious element in Sumba woven fabric. For these motifs, our people gained inspiration from dreams, which were then applied to the fabric. This is because they believe that motifs from their dreams come from God. Even to this day, there are weavers who believe that, if the motif from the dream is not immediately created in the weaving, they may fall sick. And, if they do, in traditional medicines, we learn what ingredients to use from our dreams!

Javanese people have a concept known as cokro manggilingan. Life is seen as a big wheel, where things can go smoothly for a while and then not. We don’t know when or how the change will happen. But then life will start to get better. The process repeats over and over as the wheel turns. Because of this, I believe that classical local wisdom will not completely disappear; it may diminish or evolve over time but, as long as the community exists, it won’t be lost entirely. So, when I speak about the future of Yogya batik, I remain optimistic.

The development of batik in Yogyakarta is closely tied to the Keraton, the seat and dwelling place of the sultan and his family. The complex is home to a museum of Javanese artifacts and, as both an institution and a physical entity, the Keraton is recognized by the population as the beating heart of local culture. It has adopted elements from the people’s culture and, reciprocally, the people have drawn inspiration from the Keraton.

The Keraton holds a significant position in shaping batik as a cultural icon. First, fabric is usually pre-processed by boiling. Then comes outlining or drawing the patterns in wax. The cloth is next subjected to the wedel process, or the first coloring stage, usually using blue dye. Then certain parts are left open to allow new colors to mix in, while other parts are covered with more wax to prevent mixing with previously applied colors. The last step is to remove the wax by boiling. It’s important to note that the process I’ve described applies specifically to the traditional, classic batik of Yogyakarta.

The Keraton recognizes only three types of royal batik attire and excludes the sarong or shawl, which the general population have worn. All royal and common batik attire carries significant symbolic meaning. The most essential motifs are semen parang kawung gringsing poleng, and nitik. Because of its nobility and cultural centrality, the Keraton does not simply appropriate batik motifs that have developed in the community. Instead, the motifs undergo a process of distillation, interpretation, and symbolism.

Certain rules apply: In the Keraton, the semen ageng motif is used in its complete form; when used by people outside the Keraton, certain parts are omitted. This rule is based on

oral tradition and people still follow it for various socio-cultural reasons. Another motif that still has clear restrictions on its usage is the parang. It would be inappropriate for me to wear the parang motif when visiting the Keraton. Although batik in the Keraton has a concept known as batik larangan (forbidden batik), observance of it is really just a matter of remembering traditional cultural rules. There are no legal consequences for defying it, only social sanctions.

Rulers or kings have often created their own designs. For instance, when King Hamengkubuwono VII (r. 1877–1921) received an award from Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands, he created the bedoyo batik, which documented this historic event through its patterns. Sultan Hamengkubuwono IX (r. 1939–1988) created the sudoro werti motif, which aimed to formalize a specific dance of that period.

In the Keraton of Yogyakarta, it was customary for princesses to possess skills in both batik-making and dancing. The dances and associated costumes have three levels. At the highest level, there is Bedoyo Serimpi, a ritualized dance performed by nine female dancers. There are no restrictions on the costumes worn, they may even be identical to those worn by the king as royal regalia. The corresponding male dance, Lawung Ageng, symbolizes fertility. In this dance, the sixteen dancers wear the largest kawung motif in the Keraton. In the Wayang Orang dance, all costumes worn have parang motifs, as in Yogyakarta it is part of state ritual. (Another city, Solo, has its own cultural traditions of Wayang Orang.) In the performance of Wayang Orang, the most important batik costume is worn by the character Batara Guru. No other characters are allowed to start work on their makeup until Batara Guru has begun applying makeup.

For the Keraton, batik represents more than just a piece of clothing; it holds deeper meaning and serves as a form of expression. This is why traditional, classic batik motifs generally carry aspirational symbols. I believe that batik has the power to boost self-confidence and bring about positive outcomes, apart from its aesthetic beauty. It all depends on our ability to direct hopeful energy towards the batik motifs or the fabric itself.

leraang (diagonal), meant to represent knife patterns, is also exclusive to the royal court; the lereng parang motif (lereng is the Javanese word for slope) is inspired by the waves of the Java seas. Parang means “knives” and represents resilience, and in previous eras the motif was worn only by the royal court; single leaf semen, signifying spring or sekar jagad, which is meant to celebrate the diversity in Indonesia; the ceplok kawung motif; and the Semenan motif, mountains, garuda (mythical birds), and native animals.

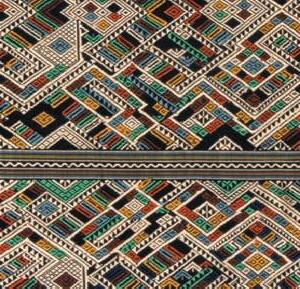

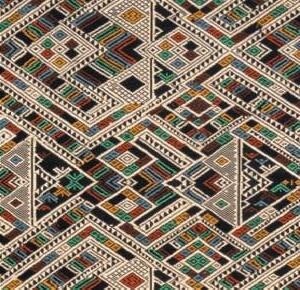

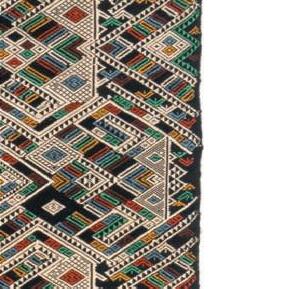

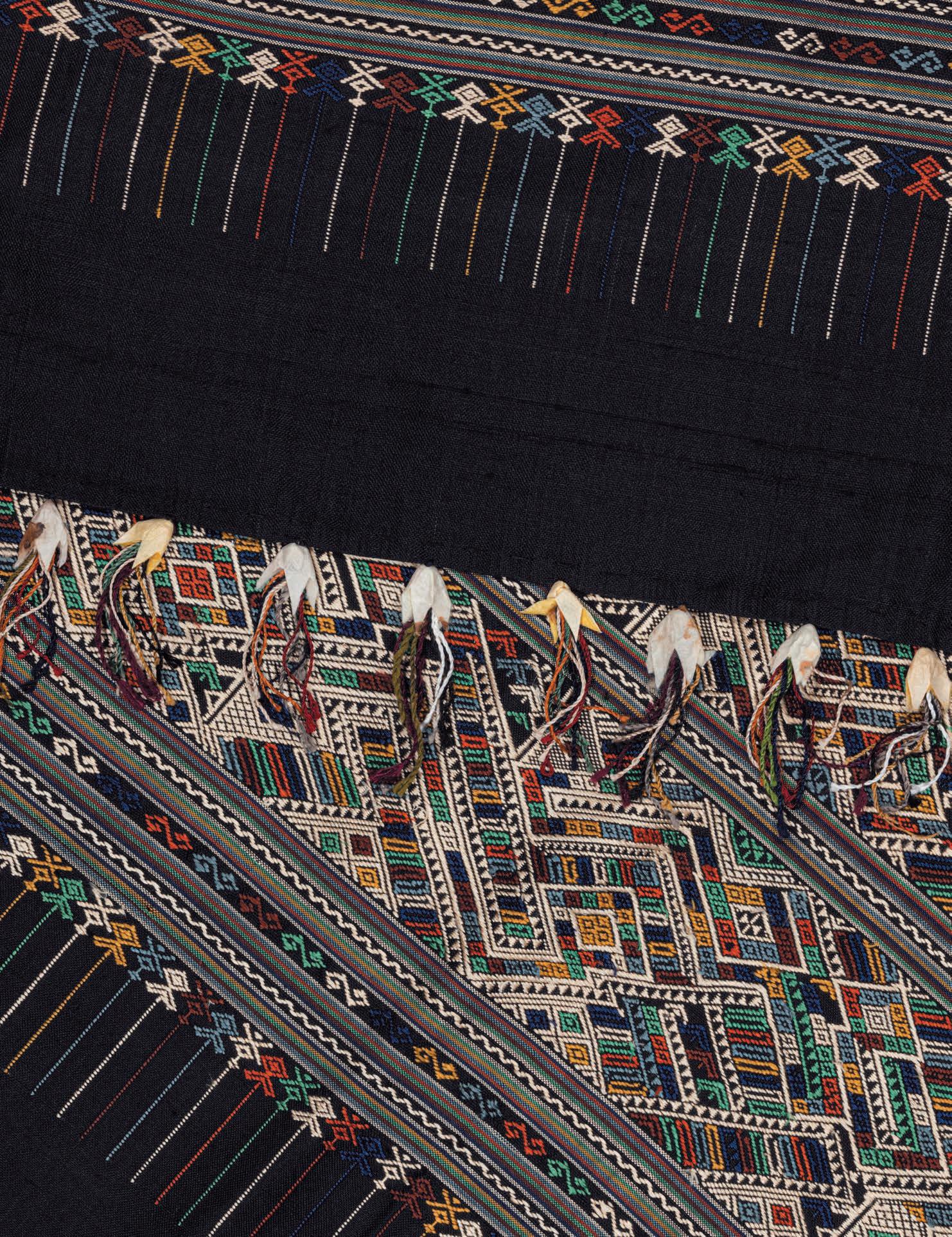

symbols within the geometric shapes of the design. This textile features naga (mythical serpents) as well as diamond-shaped lanterns. The ends are completed with fringe enclosed in silk cocoons styled to resemble flowers (above and right).

Ottoman textiles—whether employed in costumes, wall hangings, draperies, or in such practical items as wrapping cloths, bath towels, napkins, shaving aprons, bedspreads, even turban dust covers—were sumptuously embroidered. They were the product of an extraordinary and dynamic needlework culture that was handed down from mother to daughter over the centuries, evolving to perfection.

Ottoman interiors were airy and minimalist, with generously sized windows, broad divans, and not a stick of free-standing furniture to clutter up the space. It was left to embroideries, cushions, carpets, and kilims to infuse rooms with color, pattern, and texture.

Peşkir (pronounced “peshkir”) were hand towels or napkins, central to everyday life throughout the Ottoman world. They were rectangular lengths of fine, hand-spun linen or cotton in white or ecru, usually around half a meter long. Most were woven at home on small handlooms by the daughters of the house, who painstakingly embroidered each end with rows of needlepoint compositions before stowing them away in their dowry chests. The trade of professional peşkir makers and embroiderers also flourished.

Favorite needlepoint motifs were stylized but instantly recognizable flowers, birds, fruits, houses boasting pretty lattice windows and kiosks (open pavilions), landscapes filled with gardens, and even rainbows. They evoked a magical world of gentle living through infinite stitches in colored silk or glittering gold and silver thread. Those textiles made for everyday use were relatively simple but,

if a towel or napkin was intended for a gift or to be offered to a prestigious guest, it became a veritable work of art.

There are marked differences between the elaborate palace peşkir glittering with gold thread and their modest country cousins, yet peşkir were nonetheless always part of Turkish life. After a meal, an ewer of water and a bowl were brought to the guest. As one servant poured, diners would wash their hands with fragrant soap, while a second servant offered the peşkir—held out respectfully with both hands— so the guest might use the unembroidered middle part and admire the exquisite needlework. In a letter home sent in 1716, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu wrote admiringly, “After dinner, water was brought in a gold basin, and towels of the same kind as the napkins, which I very unwillingly wiped my hands upon.”

In my own life, I caught the tail end of this tradition and saw treasured examples from my grandmother’s time unused and still folded up in her 200-year-old dowry chest. In my childhood, it was a teenager’s duty to offer a fresh towel to visiting guests at home, albeit a modern, fluffy version.

With the advance of the textile industry, looms and hand-spun fabrics disappeared like so much else. But, as in the past, one can still find two types of hand towel in Türkiye: soft cotton towels with loop piles known as havlu, believed to have originated in the old Ottoman capital of Bursa, and flatweave cotton or linen peşkir hand towels. They are mass produced, of course, but both are available online or in shops. The tradition lives on.

13.5”

21”

© 2025 Hali Publications Ltd.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means – photographic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems – without permission of the publishers.

Published and produced by Hali Publications Ltd., 6 Sylvester Path, London E8 1EN, United Kingdom www.hali-publications.com info@hali.com

Editor: Ben Evans, Hali Publications

Managing Editor: Malin Lonnberg, Hali Publications

Editorial Consultant: Lyssa C. Stapleton

Art Direction and Design: Pamela Berry

Textile Photographer: Desmond Brambley

Collection Manager, Archivist, and Photographer: Amanda Lempke

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data: a catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781898113744

Cover: Photo by Gentl and Hyers, taken in Peru

Back cover: Photo by Adrian Gaut, taken in Southwest China

The study of the textiles featured in this publication was based on high-resolution photographs. Every effort has been made to correctly attribute the objects. We apologize for any errors and will make the necessary corrections in future editions upon being informed.