the style of time

the early 1900s 19 the 1910s 35 the 1920s 53 the 1930s

75 the 1940s

99 the 1950s

121 the 1960s 155

the 1970s 177 the 1980s

197 the 1990s

217 the 2000s

245

the style of time

the early 1900s 19 the 1910s 35 the 1920s 53 the 1930s

75 the 1940s

99 the 1950s

121 the 1960s 155

the 1970s 177 the 1980s

197 the 1990s

217 the 2000s

245

T ime is a great mystery: a mutable, expanding, or disap pearing principle belonging to an uncertain dimension— one that, more than any other, depends on the perception of one’s mind. Yet it also appears concrete, marked by the passing of hours, days, and years. Probing this mystery has presented a significant challenge to mankind, which, over the centuries, has felt the need to assign specific deadlines to something in continuous flow. The path toward capturing the minutes and seconds has coincided with phases of scientific evolution, allowing for the manufacture of in creasingly reliable timepieces that were also attuned to changes in custom and aesthetic canons.

A watch is a work of technical mastery. It also constitutes an artifact that blends art with science, creating what over the years has become, and remained, an object of desire.

In fine and applied arts, “style” defines the combination of formal traits that make an object distinctive, tracing it back to a specific era, or even to the person who first introduced them.

Certainly, a watch can also be viewed as a product whose stylistic code is linked to the aesthetics of a particular era, and judgment upon its taste must be read through the frameworks that belong to that era.

Consider, for example, the timepieces that emerged during the 1920s, conveying the linearity of Art Deco through their rectangular cases. In order to adapt to the tastes, which preferred straight lines, the traditional circular structure of the watch underwent a significant change. Up to that point, the circle had constituted, with few exceptions, the “shape” of

The historical period now called the “Belle Époque” was characterized by optimism, faith in progress, and joie de vivre. The period from the last decades of the nineteenth century up to the outbreak of the First World War was marked by political peace and widespread economic well-being. The world, or at least a portion of it, was savoring the euphoria of festivities that seemingly had no end. Instead, they would be tragically interrupted with the beginning of conflict in 1914. In this context of peace and economic growth, invention and advances in tech nology and science were, compared to past epochs, unparalleled. The incandescent light bulb patented by Thomas Edison in 1880 allowed for the spread of public electric lighting in cities. Studies by Gug lielmo Marconi led to the invention of the radio; Alexander Graham Bell forever changed commu nication by patenting the telephone; and Louis and Auguste Lumière astounded audiences with their first film screenings.

The transport sector had expanded enormous ly; in 1913, the railway network had reached one million kilometers (620,000 miles), and the first cars sped along the streets, to the amazement of passers by. Maritime transport also experienced extensive development, with the construction of transatlan tic liners able to accommodate travelers in comfort and luxury; on these cruise ships, time was spent among dances, tennis matches, gala dinners, and various forms of entertainment. Between the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, technological discoveries, welcomed with great enthusiasm, also inspired the world of art, be coming the subject of the ballet Excelsior, conceived by Italian choreographer Luigi Manzotti and set to music by the composer Romualdo Marenco. It celebrated the triumph of science through eight scenes in which the allegorical figures of Light and of Civi lization battle Obscurantism on the stage.

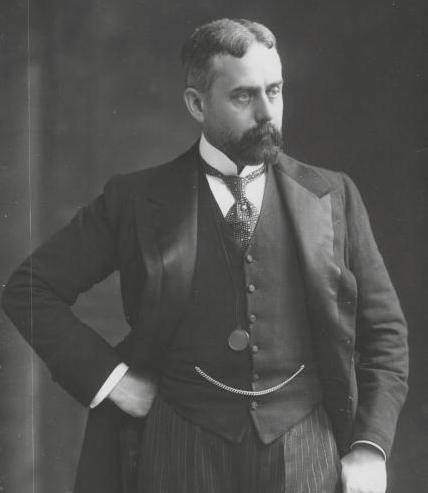

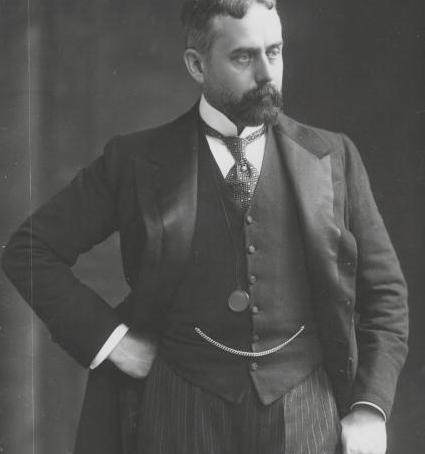

Gilbert Parker, Canadian-born author and British politician, shown circa 1905.

“Illumination of the Main Entrance to the Paris Exhibition,” from a watercolor by Tony Grubhofer, 1900.

early 1900s

The universal expositions and world’s fairs held irregularly in various cities in Europe (London, Par is, Barcelona, Milan, Turin) and the United States (St. Louis, San Francisco) were the perfect context for showcasing innovations in technology, science, and art to the general public.

The Exposition Universelle held in Paris in 1900, whose theme was “le bilan d’un siècle” (the “assessment of a century”), attracted thousands of people to the French capital looking to admire the works of art, the decorative style of Art Nouveau in both architecture and the applied arts, and, of course, the marvels of the Eiffel Tower, inaugurated one year earlier.

In this context of widespread comfort, political se curity, trust in progress, and industrial and commercial development, the upper middle class faced life with ex uberance and panache, convinced that they were liv ing in a happy, carefree era that would endure forever.

The worldly opportunities offered by city life were innumerable, and every occasion required the appropriate dress: ceremonial or ball gowns were worn for important festivities, as well as for going to the theater, opera, ballet, and even the cabaret.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the clothing sector could rely on a giant market extending throughout Europe and the United States. The most significant center of production was cer tainly Paris, where fashion ateliers and the most renowned jewelers resided on Rue de la Paix and Place Vendôme.

If ladies frequented the ateliers of Charles Worth or Paul Poiret to have the most elegant

A pocket watch by Girard-Perregaux, a Tourbillon with Three Gold Bridges, was awarded a gold medal at the 1889 Paris Universal Exhibition. It would provide inspiration for a wrist model made in 1991.

The decade spanning 1910 to 1920 was one of the most shocking in history. Even prior to the world conflict that would engulf Europe and the rest of the world between 1914 and 1918, the period was animated by great social unrest. The political balance was growing ever more precarious due to nationalist tensions and ex tremist attitudes, while demonstrations by suf fragettes, fighting for recognition of their voting rights and to achieve parity with men generally, intensified in both legal and economic realms.

At the same time, there was a great ferment in the world of art: the decade was especial ly intense, full of variety and dynamism, and characterized by a complex articulation of styles rather than uniformity. In this eclectic period, the sinuous, interweaving lines of Art Nouveau met with the rigorous, geometric lines of the art movements anticipating Art Deco. Prevailing among the wealthy classes in con -

trast to this aesthetic were historic avant-garde movements that had just been developing from the early years of the twentieth century, which had a rousing, innovative power to them; these included Symbolism, Fauvism, Cubism, Fu turism, Expressionism, and Dadaism. In many cases, they were also fueled by political ideolo gies, which would lead to a profound transfor mation of the artistic lexicon. These currents were also all conceptually intertwined with oth er cultural, scientific, technological, and philo sophical events that had a significant influence on society at the time and, indeed, would mod ify it profoundly. Sigmund Freud’s The Interpre tation of Dreams had been published in 1899, and the innovative readings of the psyche offered by Freudian studies influenced the work of the Symbolists, anticipating Surrealism. New con cepts of reality, representation, and memory

May 6, 1910. The Duke of Roxburghe visits Buckingham Palace following the death of King Edward VII.

— the 1910s

emerged from the research of Henri Bergson, collected in the publications Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness (1889) and Matter and Memory (1896), which also opened new paths in the perception of time. Albert Einstein’s revolutionary theory of rela tivity, first published in 1905, suggested, to artists of the Cubist and Dadaist current, potential future perspectives on reality. Mechanical innovations in flight and automobiles fascinated the Futurists, whose aesthetic projected itself toward the new, just as it was intent on severing links with the past.

A geometric, antinaturalistic style was born of these trends, already orienting itself toward simplified shapes and broken lines. Elegant, accurate, and precious in terms of material se lection and other respects, this aesthetic influ enced the production of home decor, artifacts, jewelry, and, of course, watches. This last cat egory in particular was freed from restrictive floral harmonies to embrace this new linearity.

in its capacity for creative expression, Coco Chanel must be named as a protagonist. Chanel had opened a boutique in Deauville in 1913, followed in 1915 by another shop in Biarritz, where she dressed ladies who had fled Paris and found refuge in resorts. A great entrepreneur, she was able to offer clothing produced in one of the few fabrics available: jersey. Her garments were not “war clothes,” however, but dresses, albeit rendered with a stronger linearity. They were sought after for their workmanship and cut, with ladies of the aristocracy competing for them at very high prices.

In wartime, the scarcity of available materi als led fashion to bend toward a more austere style, embracing new demands for practicality and frugality and using a limited range of col ors with a prevalence of dark shades for both men and women. When considering changes in fashion, not only in terms of its function but

Many men joined the army, and, from 1914 until nearly the end of the decade, they wore only military uniforms. Military apparel was not only accepted, but even recognized as mascu line and preferable to bourgeois refinements; the latter bordered in some cases on dandy ism, an excessive attention to detail and care for one’s appearance. For the futurist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the appearance of virility in a man enhanced his capacity for seduction, as the artist’s writing attests: “There is no lover that a beautiful woman can have but a soldier, fully armed, returning from the front and soon again to depart. His boots, spurs, and bandolier are essentials for love. The jacket, the tailcoat, the tuxedo, and the frock coat are made for the seat, the armchair. They evoke the library, the slow defloration of untouched books, the greenshaded lamp, the fetid breath of moralists, professors, critics, philosophers, and pedants. These are, in fact, the husbands that I crown consistently thus: the enemies of divine speed, all.” 1

1 F.t marinetti, Come si seducono le donne e si tradiscono gli uomini , in Pautasso, Guido Andrea (ed.), “Moda Futurista. Eleganza e seduzione,” Abscondita, Milano 2016.

Immediately after the war, men’s clothing would return to the three-piece suit. If at the beginning of the century the less-formal suit of a well-to-do man was worn only for loung ing around the house, the three-piece suits in the early years of the second decade, dubbed “lounge” suits, were becoming more noticeable and more popular than the men’s dress worn before 1910, establishing the frock coat. Espe cially after the war, a slow but persistent, more casual alternative to formal clothing began to appear. Trousers were tapered at the ankle and shorter, while collars were high on the neck and starched. The lounge suit was often worn with a bowler or wide-brimmed felt hat, though upper-class men continued to wear top hats. In the evening, dark tailcoats were paired with white vests, and the tuxedo, though less for mal, was considered an acceptable form of el

Tiffany & Co., Pendant Watch Necklace, c. 1910. Women’s pendant watch with circular steel dial, signed Tiffany & Co., with Arabic numerals and steel hands. Green guilloché enamel is applied to the bezel and blue guilloché enamel to the case, which features rose-cut diamonds in millegrain settings. Its chain is made of tapered links coated in blue and white enamel.

egant attire. Born as a complement to military uniforms, the trench coat entered gentlemen’s wardrobes after the war, and over time it would become one of the first unisex clothing articles.

One item would enter this revolution of taste and style to become the very symbol of progress and modernity: the wristwatch. While watches for men’s waistcoat pockets and pendant watches for women were still the standard, the prewar years were already witnessing a series of newborn watches that distanced themselves

In 1919, the Treaty of Versailles was signed, bring ing an end to the First World War and restoring peace. The decade to follow, stretching to 1929— the year of the stock market collapse and onset of the first great economic crisis—would be termed the années folles: the “crazy years.” This period was characterized by a joyful, exuberant atmo sphere.

A period of great prosperity began in Europe at the end of the armed conflict, supported in part by strong economic growth. After the war, the world seemed almost intoxicated by items of entertain ment that technological development had made available: the radio, born during the Belle Époque, had been perfected, and the gramophone became more widespread, making it possible to listen and dance to jazz from overseas, while motion pictures with sound garnered worldwide fame for the wonders of Hollywood.

Paris became the undisputed European capital

of entertainment, with cabaret and café chantant, where they danced the Charleston and one could attend the Revue Nègre. The latter’s undisputed star was American-born dancer Joséphine Baker, who performed in revealing costumes that were scandalous for the era.

The period was marked aesthetically by Art Deco, an architectural and decorative style char acterized by shapes and geometric elements, punc tuated through use of color. Deco would be an aes thetic typical of the applied arts until the end of the 1930s, albeit with the addition of various subtle differences to accommodate changing times.

The Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Indus triels Modernes (International Exhibition of Modern

People in elegant attire dancing at a formal party, late-1920s.

Decorative and Industrial Arts), inaugurated in Par is on April 28, 1925, signified the official birth of the grand, complex style of L’Art Déco. While the aes thetics of Art Nouveau were complex, opulent, and by then redundant, Art Deco was clear and linear. Its sources of inspiration were many, especially in figurative art: the rich colors of the Fauves; the Cubists’ engagement in the study of form, which in turn was inspired by African ethnographic art, geometric Mayan art, and artifacts from ancient Egypt; and the paintings of Futurist artists, exalting in the speed and advancement of machines.

The applied arts also produced a wide range of objects that together formed a true Deco style, and it was not unusual for artists of this style to express themselves in various settings, from figurative arts to stage design, from illustration to clothing and jewel ry design. Providing another source of inspiration were the visionary fantasies of the Ballets Russes. Be ginning in 1910, the dance company, founded by Russian impresario Sergej Diaghilev, would stage the most popular shows of its time in Paris. The in tention was to eliminate the fluid lines of Art Nou veau and distill designs into their primary geometric essence, creating a new construction of volumes and eliminating any apparently useless ornament, thus creating a cleaner, more stylized and symmetrical line than what jewelry prior to that moment had.1

new faster, more dynamic pace of life, which required greater freedom of movement. Men no longer had starched collars; instead, they adopted soft collars and one- or two-button suit jackets. These were often worn without a vest, which was replaced with the more comfortable pullover sweater. The English and the style of Savile Row still served as a primary reference for elegance in men’s fashion. Prince Edward, who would ascend the throne as Edward VIII in the decade to follow before abdicating, exemplified this style. The prince loved suits with a comfortable cut, with jackets and loose trou sers in tweed, with a houndstooth, pinstripe, and, of course, Prince of Wales pattern. From Germany came the broken suit, a trend started by German statesman (and, for a brief period in 1923, Chancellor of the Weimar Republic) Gus tav Stresemann, consisting of a single-breasted black jacket, a gray vest, pinstripe trousers, and a light-colored tie.

The end of the First World War heralded a pe riod of excitement, creativity, and joie de vivre In this decade, clothing also adapted to the

“Oxford bags,” on the other hand, serve as an example from more transgressive fashions. These were snug trousers with a high waist and high cuffs, with bottoms that could be as wide as one hundred and fifty centimeters (sixty inches). Made of flannel and paired with a fitted, color ful jacket, they were mostly worn by the “bright young things” belonging to the upper classes of British and American society, who were known for their carefree lifestyles. In the postwar period, sports activities gained a great deal of popularity at all levels of society and strongly influenced the style canon. Two of the most popular sports, especially among well-to-do classes, were golf and

1 rauLet, syLvie, Art Deco Jewelry , Rizzoli International Publications Inc., New York 1985.tennis. Knee-length breeches like knickerbockers or plus fours 2 , worn with thick socks, laceup shoes, and a simple sweater or shirt, made up the golfer’s uniform, while long trousers, a shirt, V-neck sweater, cap, and shoes, all strictly white, formed that of the tennis player. The overcoat was an indispensable component in the elegant man’s wardrobe; it became sportier and more fitted in this period, often made with fur or satin lapels. In more formal settings, the tuxedo became the most popular garment, especially a shawl-collared model worn by Prince Edward, while the tailcoat, still in vogue, was worn un buttoned, its tails a few centimeters (a couple of inches) longer than in the past.

In this context favoring comfort, where sports wear thrived alongside more formal clothing, the pocket watch with a gold chain shining on one’s waistcoat (a sign of a certain social status) was joined by new offerings.

Pocket watches were still very popular, especially when combined with elegant suits. However, they took on carré, octagonal, and rectangular shapes, in line with Art Deco’s dictates opting for geomet ric lines. Cases were made of rock crystal (which was transparent and allowed the properly assem bled “skeleton,” or squelette, of the movement to be seen) or of onyx, or their surfaces were decorated with enamel applied in linear shapes and bright colors, ever aligned with the look of the time. So-

Watch Brooch, Cartier, Paris, 1925. Platinum; gold; onyx; coral; “huit-huit-” and rose-cut diamonds; black, green, and white enamel; black silk cord. The (mobile) case is enameled with polychrome Persian decoration on both sides. The length of the watch brooch is 6 cm. Oval LeCoultre movement, Caliber 103. Damaskeening decoration, rhodium-plated, with 19 jewels, a Swiss anchor escapement, bimetallic balance, and Breguet hairspring. Cartier Collection.

called savonnette models, also known as “hunter” watches, were introduced, whose dial was covered by a smooth outer case; others were offered in a demi-savonnette (demi-hunter or “half-hunter”) ver sion, with an opening in the center of the lid, al lowing the wearer to see the time while keeping

2

These were knee breeches that had four extra inches of fabric below the knee (hence the name); but instead of stretch ing over the leg, they were tied around the knee with a band, blousing out over the band.

Movado Ermeto watch. The case is decorated with fine red and gold lacquer work depicting an Eastern landscape, embellished at its center with a cabochon ruby. Its sliding panels open to reveal a square dial with Arabic numerals.

the dial protected. Retractable models were made to be carried in one’s trouser pocket (no longer just that of a waistcoat) and in ladies’ handbags, like Movado’s Ermeto.

Introduced in 1926, the Ermeto was conceived as a travel watch. Its name, meaning “sealed” in Greek, derives from the fact that the movement and the dial are enclosed within an openable out er case, protecting them from dust and shock. In 1927, Movado made this model even more unique with an ingenious patent: a “rack-winding” system which wound the watch whenever the outer case was opened and closed. Alongside the traditional pendentif, a watch worn as a charm on a precious chain, and the widespread watch brooch, all the major fashion houses at the time were placing on the market women’s wristwatches of all shapes (oval, rectangular, tonneau, hexagonal), embellished with gems, on pearl bracelets, or bands of

velvet or moiré silk. New mechanisms allowed in creasingly thinner cases to be made. In 1924, for example, Jaeger-LeCoultre created the Duoplan movement. Its parts were arranged on two planes, making it possible to design small-scale watches.

Rectangular, carré (square), and tonneau (bar rel) shapes were favorites in men’s watchmaking, and many options were made available to gentle men opting for the new instrument in this decade. Patek Philippe, for example, introduced the Gon dolo in the early 1920s, which came with a rect angular, cushion, or round case, as well as the first split-seconds wrist chronograph in 1923. In 1925, the manufacture, ever dedicated to research, introduced the first wristwatch with a perpetual calendar and a wrist model with a minute repeater, a complication that the maison had produced through its masterful skill in pocket watch manufacture.

Purse watch, 1920s. Two-part slide-open silver case. Spring system for vertical placement. Hand-wound mechanical movement.