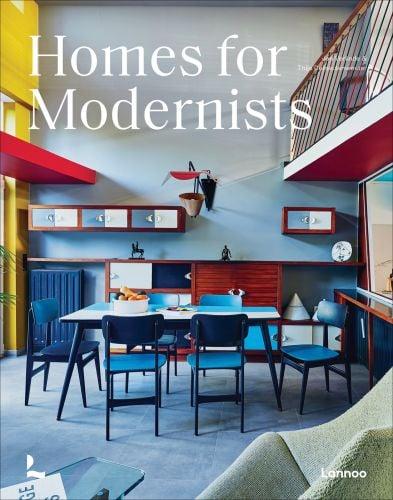

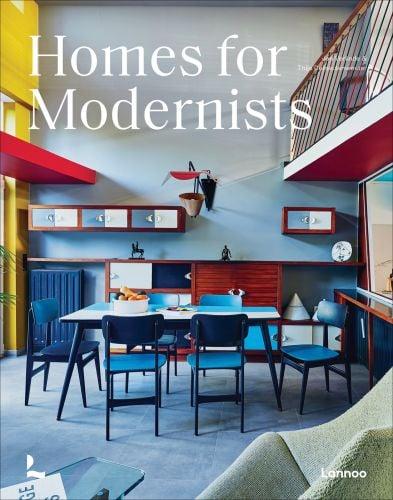

Homes for Modernists

Jan Verlinde & Thijs Demeulemeester010 Hortus Horta.

020 Modernist colouring book.

030 Modern Times.

040 The Love Boat.

050 Roaring Waregem.

062 Stynen in the House.

072 Family Affair.

082 Mad Mansion.

092 Fifties Time Machine.

102 Postmodern monument.

112 Out of Respect for Gaston.

122 Poetry in Concrete.

132 Monumental challenge.

144 Casa Ronda.

156 Into the Wild.

164 That Seventies Flow.

178 Concrete Paradise.

188 Modernissimo.

198 In Concreto.

210 Simplicity is a Virtue.

Homes for Modernists

Jan Verlinde & Thijs DemeulemeesterVilla Carpentier, Victor Horta's country house in the rolling hills of the Flemish Ardennes, is

a masterpiece of art nouveau – with a matching garden.

Brussels-based power couple Michel and Olga Gilbert are avid collectors of homes by art nouveau architect Victor Horta, who could be called the Belgian Antoni Gaudí. Villa Carpentier in Ronse brings their tally of Horta homes to four. The picturesque country house in the Flemish Ardennes was built between 1899 and 1901 for textile baron Valère Carpentier, who mainly used it as a holiday getaway and hunting pavilion. Horta (1861-1947) not only designed the residence, but also – unusually for him – mapped out the garden as well, although it had later been left to grow wild. Olga Gilbert recently refurbished the overgrown garden with carefully chosen plants and shrubs. The villa has been meticulously restored. That was destined to succeed, with Michel Gilbert’s unmistakable passion for Horta’s legacy. Villa Carpentier was built in the same period as Horta's own studio home in Brussels, now the Horta museum. The villa is a typical example of art nouveau: a Gesamtkunstwerk which dozens of artisans and artists worked on, including Emile Fabry and Albert Ciamberlani. In terms of style, the home leans more towards the arts and crafts movement than the art deco style that Horta would evolve towards later in his career. Strictly speaking, the house is not modernist in design, but the best-known Belgian architect of the 20th century could not be absent from Homes for Modernists. www.victorhorta.be

nl

In een immofolder stootten Joris Verdoodt en Gino Bulcke toevallig op een Gentse woning van Gaston Eysselinck (19071953). Woning Lambrechts uit 1939 was niet beschermd, dus het koppel had hun handen vrij om er hun stempel op te drukken. Maar dat deden ze – gelukkig – niet. Bijna alles lieten ze intact zoals in Eysselincks tijd. Inclusief de keuken en de badkamer, die heel compact zijn naar hedendaagse comfortnormen. ‘We deden geen enkele structurele ingreep in de woning. De circulatie en de ruimtes zijn helemaal zoals de architect ze bedacht’, zegt Gino Bulcke. ‘De woning is ook niet geïsoleerd zoals men het nu voorschrijft. Maar dat kon ook niet zonder de originele architectuur te verminken.’ De puristische aanpak van Joris en Gino gold niet voor het losse meubilair. Ze wonen niet in een perfecte tijdscapsule, ook al staan er wel zeldzame buisstoelen van Eysselinck.

Toen Gino en Joris ze kochten, stond de woning 10 jaar leeg. Ze kon een grondige opfrisbeurt gebruiken. Er waren sinds 1939 enkele ongelukkige ingrepen gebeurd, maar die bleken gelukkig terug te schroeven. Onder een laag plastiekverf uit de jaren 50 troffen Joris en Gino bijvoorbeeld het originele geschraapte cementpleister én de oorspronkelijke verfkleuren terug. Rotte ramen werden vervangen, een rustieke baksteenschouw werd afgebroken, allemaal om de originele ziel van het huis opnieuw bloot te leggen. Dat vergde jaren van engelengeduld én oneindig veel speurwerk in het archief van Eysselinck. ‘We hebben zelfs een achttal andere woningen van hem bezocht’, aldus Joris. ‘Een woning restaureren sluit vele interieurkeuzes uit. We hebben ons aangepast aan het huis. Niet omgekeerd.’

‘Restoring a house excludes many interior choices. We adapted to the house, not the other way round.’

C’est en feuilletant une brochure immobilière que Joris Verdoodt et Gino Bulcke sont tombés par hasard sur une maison gantoise conçue par Eysselinck (1907-1953). Comme la maison Lambrechts, qui date de 1939, n’était pas classée, le couple aurait pu y imprimer son cachet. Mais il ne l’a heureusement pas fait. Joris et Gino ont pratiquement tout laissé intact, comme à l’époque d’Eysselinck. Y compris la cuisine et la salle de bains, qui sont très compactes, mais conformes aux normes contemporaines. « Nous n’avons réalisé aucune intervention structurelle. Les circulations et les espaces sont tout à fait comme l’architecte les a imaginés », commente Gino Bulcke. « La maison n’a pas non plus été isolée comme on le prescrit aujourd’hui. C’était impossible à faire sans défigurer l’architecture originale. » L’approche puriste de Joris et Gino ne s’est pas appliquée au mobilier libre. Ils ne vivent donc pas dans une capsule temporelle… encore que l’on trouve chez eux des chaises tubulaires très particulières d’Eysselinck.

Lorsque Gino et Joris ont acheté la maison, elle était vide depuis dix ans et avait bien besoin d’un rafraîchissement. Quelques interventions malheureuses avaient eu lieu depuis 1939, mais aucune ne s’est avérée irréversible. Par exemple, Gino et Joris ont trouvé sous une couche de peinture plastique des années 1950 l’enduit en ciment gratté et les couleurs de peinture d’origine. Les châssis pourris ont été remplacés, un manteau de cheminée rustique a été démoli et l’âme de la maison a été redécouverte. Cela a nécessité des années et une patience d’ange, sans compter un important travail de recherche dans les archives de l’architecte. « Nous avons même visité huit autres de ses maisons », dit Joris. « Restaurer une maison exclut bien des choix d’aménagement. Nous nous sommes adaptés à elle. Pas l’inverse. »

That Seventies Flow.

Although she was actually looking for an interbellum home, Ellen van Antwerpen fell head over heels in love with this James

Bond-like villa, built in 1978 by architect Etienne De Pessemier.

Ellen's surname is a misnomer; she does not, in fact, live in Antwerp proper, but near where she grew up: on the outskirts of Schilde, a wooded suburb. An entrepreneur who runs the baby concept store Babyluff, Ellen came across a brick villa after a tip from the founder of Immodôme, an estate agency that often has architectural heritage for sale. Ellen had actually been dreaming of an interbellum house, but this funky 1978 villa designed by Etienne De Pessemier also ticked a lot of boxes. Known for his spacious residential villas with unusual interior-exterior relationships, De Pessemier founded architecture firm Arcon. He also designed the open-air school in Brasschaat and the brutalist Customs building that was demolished to make room for the Cadiz district in Antwerp. The villa includes several typical features of De Pessemier: spaciousness, abundant light, the floating stairs and the oversized, rhythmical fenestration. Since the structure, materials and circulation were in fine condition, Ellen Van Antwerpen and her husband changed nothing there. They came up with a smart, affordable solution for the white kitchen: they covered the existing Formica cabinet fronts with a leather-look foil. What Van Antwerpen particularly liked was that the home had lots of nooks and crannies. As a former visual merchandiser, she had no trouble furnishing it with her personal mix of vintage, pop art and curiosities.

Simplicity is a virtue.

As a renowned design dealer, Alexis Vanhove was very familiar with who Christophe Gevers (1928-2007) was. When the studio home of that legendary Belgian designer and interior architect went up for sale in 2020, Alexis and his wife didn't take long to decide.

The house in Ohain, in Walloon Brabant, is a self-portrait of Gevers and of his unique way of working. In order to understand him better, you first have to take a look in the basement. That's where Gevers had his studio full of machines and tools, with which he made prototypes, scale models and products. Along the way, he discovered the simplest, most efficient and most poetic solutions for his products and interiors. He was well-known in Brussels for his interior architecture in large bank buildings and famous restaurants such as Canterbury, Marie Joseph and Au Vieux Saint Martin. Sadly, few of his private and public interiors have remained intact. And that's exactly what makes his studio home so unique. Built in Ohain in 1962, this is where you see Gevers experimenting with the space, in dialogue with nature, which was his greatest source of inspiration. In his own house, it is striking to see just how refined simplicity can be. The whole house is filled with simple but well-crafted details, realised in the simplest of materials. 'Look at that hand-painted serving hatch. Or the banister rail, made from ships rope. The brickwork library, where the shelf supports consist of bricks that jut out. The carport, consisting of two simple tarps. The fireplace, which is actually just a row of metal tubes with spaces in between. The kitchen cabinets, made from U-shaped profiles, into which plexiglass sliding doors are fitted,' says Vanhove. 'And have you seen his system for hanging pictures? He affixed doubleglass panels to the walls, which can be unscrewed to put photos or works of art between. It doesn't get any simpler.'

a collection of belgian modernism christophe gevers 1962

interior architect architect’s house canterbury au vieux saint martin