STEFANIE VON WIETERSHEIM

1815 to 1852

Lovelace by name, lovely by nature. Ada Lovelace has skin like alabaster. Hair like mahogany. A clear sideways gaze. Her left hand, with a slim gold ring, rests on the buckle of the girdle around her sumptuous white silk dress with wide Snow White neckline. The slim beauty is crowned with a classical-style headband.

This portrait of Lord Byron’s daughter was painted by Margaret Sarah Carpenter in 1836. And the appearance, yes, the beautiful illusion of a highly decorative aristocrat is deceptive. You see, the German Informatics Society is not showcasing this stunning painting without good reason: Ada Lovelace is regarded as the first ever computer programmer.

Computers in the first half of the nineteenth century? Invented by a woman born in the year of Napoleon’s final downfall? How is that possible? Quite simply, Ada Lovelace is an example of our deeply rooted prejudices against women, especially attractive and expensively dressed ones. She reveals shows how deceptive images can be; how we are used to seeing the surface first and foremost, especially where women are concerned. And yes, if all we have are their portraits, with no interviews or videos to help us know them better, then we relegate women like the elegant Ada to the same category as women whose lives were taken up with embroidering wall screens, playing the spinet, and learning French. And in the best case, they were disposable assets for fathers and men on the marriage market. Given this, the story of Ada Lovelace is all the more fascinating—the first programmer, mathematician, and inventor, after whom numerous women’s empowerment programs are named today, but who is still far from a household name.

Ada Lovelace (shown left in an 1836 painting by Margaret Sarah Carpenter) received advanced science tuition from a young age and later developed a machine for processing information.

Ada, Lord Byron’s daughter, painted as a 20-year-old in 1835 in this watercolor portrait by Alfred Edward Chalon.

19, she fell in love with her tutor and tried to run away with him, but the affair fizzled out. Instead, she gave in to the expectations of her social class and married mathematician William King, ten years older than she was, just a month after meeting him in July 1835. Family duties had a disastrous effect on her research.

Marriage, sex, and running a house and family became a huge obstacle for Ada’s studies as a private scholar, since she had three kids in four years. While her husband appreciated her intelligence and supported her work, he could not prevent her from wearing herself out between her solitary studies, the births of two sons and a daughter, and her duties running various households. We can still imagine today how hard her life as a scientist and a woman must have been at a time when that role was not accepted by society. She once admitted to her colleague Mary Somerville that her marriage was unhappy because she had so little time for math and music after tending to the children. And, noblesse oblige, she also enjoyed playing the harp and violin and had serious ambitions as a singer. Amid this burnout Ada threw herself into several love affairs, became a compulsive gambler on horses, racked up debts, sold the family jewelry, and, to cap it all, eventually, fell seriously ill with anorexia. In the early 1840s, she became addicted to opium and alcohol. The children were sent to their grandmother in this difficult home situation. Bedridden and dying of cancer, she spent the last years of her life developing a sophisticated “secure” betting system based on advanced mathematics. When she died in London in 1852 aged just 36, her family was surprised to learn she wanted to be buried next to her father, the famous Lord Byron: the man who had always been absent from her life.

ANDRÉ-MARIE AMPÈRE (1775 to 1836) Physicist and mathematician

NAPOLEON BONAPARTE (1769 to 1821) Emperor of France

LORD BYRON (1788 to 1824)

Poet (and Ada’s father)

CARL FRIEDRICH GAUSS (1777 to 1855)

Mathematician

GEORGE BOOLE (1818 to 1864) Mathematician and philosopher

CHARLES DICKENS (1812 to 1870)

Writer

Would be called “gifted” today and was the first person to devise computer programming

Never really knew her father, the famous poet Lord Byron (1788 to 1824), because her mother left him when Ada was just a few months old

As a 12-year-old mathematics genius, she invented steam-powered wings that would lift people off the ground

At the time, as a woman she was forbidden to access libraries or universities, so her husband William King copied books for her there

1 2 3 4 5 6

Suffered from anorexia and was addicted to opium, laudanum, chloroform, and alcohol

Featured as the heroine in Friedrich Christian Delius’s 2009 novel “The Woman for Whom I Invented the Computer”

1815: Born Augusta Ada Byron, known as Ada Lovelace, the sole legitimate daughter of the poet Lord Byron

1815: Her parents separated; her mother, Anne Isabella Noel-Byron, encouraged Ada’s interest in science and math

1835: Married mathematician William King, just a month after meeting him

1836-1839: Birth of her three children, Byron, Ralph Gordon, and Anne

1830s: Worked with Charles Babbage on his mechanical calculator; in-depth math studies

1852: Died of cancer at 36, in poor health and addicted to drugs

Mid-20th century: Rediscovered as a visionary pioneer of the computer age

1970s: The programming language Ada was named after her

Today: Hosts of awards and initiatives are named after her, including the Lovelace Medal, the Ada Lovelace Award, and the cryptocurrency ADA; the Ada Lovelace PhD program at the University of Münster provides funding to up to three female mathematicians or computer scientists every year

In the 1970s, the programming language Ada was named after Ada Lovelace. Today, plaques, comics, and memes confirm her rediscovery as a tragic mathematical heroine.

1865 to 1950

The young woman stands in a photography studio, wearing a sumptuously draped gown and train, with velvet leg-of-mutton sleeves and crocheted lace front. She is leaning against an ornate Victorian-style throne chair and looks slightly uncomfortable.

It is the year 1880, and the 15-year-old girl with the neat center parting, tightly laced stays, and hand resting on her right hip looks positively imprisoned. In a dress, in a room, in a life. We sense a certain reluctance in this person, who had long regarded herself as an “ugly child.” What viewer of this photo would have imagined that the young New Yorker Elsie de Wolfe would rent asunder the grandiose fabrics of the Gilded Age around her and carve out a reputation as a self-assured lesbian career woman in interior design in the USA and Europe? Like so many women of her generation and background, the daughter of an American doctor, who had spent part of her childhood in Edinburgh, seemed destined for a conventional life after leaving school. Elsie was even a debutante at the court of Queen Victoria in 1883, at that time the pinnacle of social ambition for American mothers who dreamed of marrying their daughters to an English lord. But unfortunately—or was it fortunately?—for Elsie, her father left her a mountain of debt when he died in 1890 and she had to find a way to finance her life if she rejected marriage as a solution. In a rather unusual response to fate, she decided to become an actress. In 1891, she played the title role in a New York production of Thermidor by French playwright Victorien Sardou and thenceforth earned her living in the theater. In 1901, she founded her own company, with which she toured London and later Broadway. The personal and professional soon came together in the best possible way when she met Elisabeth “Bessie” Marbury at a party in 1892. Ten years Elsie’s

Out with fuss and frippery: Elsie de Wolfe, the first interior designer in the USA, totally changed the lifestyle of a whole generation.

JUST AS IMPORTANT

ELSIE DE WOLFE

Considered the first professional interior designer in the USA, she did not embark on her career until the age of 40 and achieved overnight fame for her interiors for the first women-only “Colony Club.” She was nicknamed “The Chintz Lady”

Lived openly in a lesbian relationship for over four decades and, at 61, entered a marriage of convenience to diplomat Sir Charles Mendl

Invented a feminine, light style of interior design in eighteenth-century revival style, which spawned decades of imitations. She introduced leopard print fabrics, green and white stripes, black and white schemes, mirrored walls, and wickerwork textures in her interiors. In the 1970s Karl Lagerfeld furnished his apartment with chairs and a sofa from one of her house projects

1 2 3 4

During the First World War, opened Villa Trianon at Versailles, which she had restored, as a hospital for wounded soldiers and became a nurse

Was forced to leave Villa Trianon during the German occupation in 1941, but returned there after the war and lived there until her death in 1950

5 6

Kept fit in old age with a regime of morning calisthenics, yoga, and headstands, followed strict diets, and embraced cosmetic surgery

7

Sometimes dyed her hair blue or purple to match her outfits, often carried a little dog around, and was the inspiration for the Elsie Rooftop Bar on New York’s Broadway

8

Was photographed in her couture dresses by the most famous photographers of her time, including Horst P. Horst and George Hoyningen-Huene; her style became so famous that Cecil Beaton once attended one of Elsa Maxwell’s parties dressed up as Elsie de Wolfe

9

When she saw the Parthenon for the first time, cried: “It’s beige! My color!”

1859: Born December 20 in New York City as Ella Anderson de Wolfe, daughter of Canadian-born doctor Stephen Etienne De Wolfe and his wife Georgiana, née Watts Copeland

Late 1870s: Attended a girls’ college in Edinburgh and was a debutante at the court of Queen Victoria

1880s–1900s: Actress in New York

1905: Took up interior design; decorated the Colony Club in New York—the city’s first women’s club, founded by suffragettes

1903: Bought Villa Trianon in Versailles, together with her partner Elisabeth Marbury and Anne Tracy Morgan

VICTORIEN SARDOU (1831 to 1908) French playwright

From 1905: Built a career as the first professional American interior designer

1913: Publication of the influential design book The House in Good Taste

After 1918: Awarded the Croix de Guerre and the Legion of Honour for her work with wounded soldiers in the First World War

1926: Surprising marriage to Sir Charles Ferdinand Mendl, attaché at the British Embassy in Paris

1933: Death of her longtime partner Elisabeth Marbury

1950: Died on July 12 in Versailles; urn buried at Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris

HENRY CLAY FRICK (1849 to 1919)

US industrialist and art collector

PIERPONT MORGAN (1837 to 1913) US entrepreneur

OSCAR WILDE (1854 to 1900) Writer

PIERRE DE NOLHAC (1859 to 1936) Curator of the Palace of Versailles

JOSEF HOFFMANN (1870 to 956) Austrian architect and designer

CONDÉ MONTROSE

NAST (1873 to 1942) US publisher

DOUGLAS FAIRBANKS (1883 to 1939) Actor and film producer

1876 to 1972

Lying totally naked on the forest floor for your girlfriend to take photos? Giving polyamory a try? Living openly as a lesbian? If a woman in today’s Western societies openly says she wants to love a woman—or even several—it’s really no longer a big deal for most people around her.

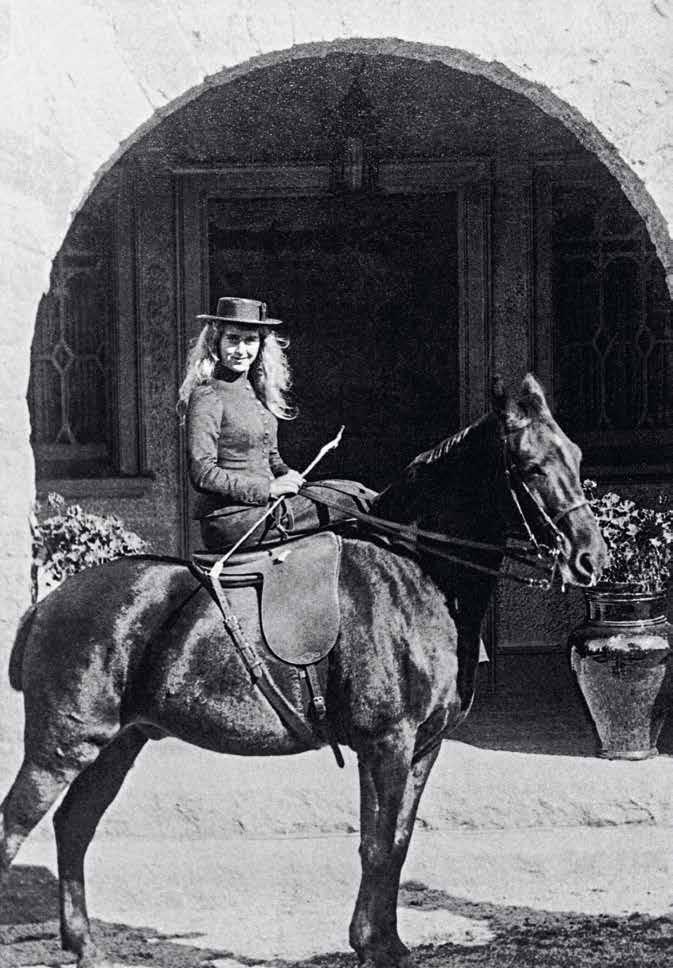

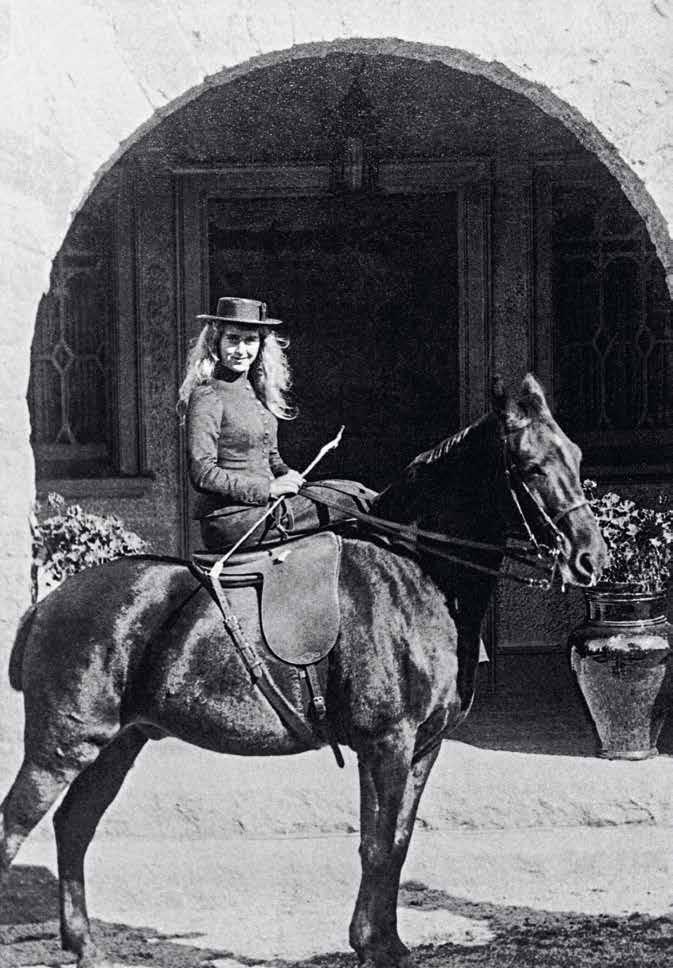

Love is love, no matter who the object of that passion is. A hundred years ago, in Europe and the US, a millionaire’s fortune and immense courage were the minimum requirements for embracing that lifestyle. The alternative could be ending up in jail or an asylum, being shunned by society, and disinherited. Being born into immense wealth and staying that way was a huge help for American poet Natalie Clifford Barney, born 1876, when she moved from the US to Paris around the turn of the century to live openly as a young lesbian woman. The effervescent heiress with striking blonde hair and intense blue eyes, educated in the USA and Europe, refused to play along with the rules of being a debutante—even in Washington, where the motto was: “Snag the right husband, make your ambitious parents happy, and your life will be a success!” By age twelve, the daughter of the art-loving, but also snobbish and tyrannical railroad heir Albert Clifford Barney and his artist wife Alice already knew she loved women. Scandalously, athletic Natalie rode around on a man’s saddle, took off her annoying petticoats in the carriage, and adored the sport of fencing, and she had no interest whatsoever in her father’s plans to marry her off to an English lord, which remained his

From the USA to Paris: Heiress Natalie Clifford Barney launched a literary salon and became known as a polyamorous lesbian author. She is seen here posing with her dog in 1910 (left), and in around 1908 (above).

Thornton Wilder made pilgrimages there, as did Rainer Maria Rilke, art collector Peggy Guggenheim, and painters Tamara de Lempicka and Marie Laurencin. The salon became so famous in the neighborhood that the neighbors took to meeting on the sidewalk before it started, just to watch the parade of rich people in limousines, beautiful female couples, people wearing Greek robes, famous opera singers, and members of the Académie Française.

So how did a rebellious, extremely wealthy American woman end up carrying on the centuries-old tradition of the famous literary salons in Paris?

“I was an international person myself, and since I had a beautiful house, I thought I should help other international people meet each other. The other literary salons weren’t international,” she once explained in an interview. “Newcomers who didn’t know what to do with themselves could come here. Americans found translators for their works. I gave afternoons for French or American poets so others

Sapphic ritual dances in Natalie Clifford Barney’s garden, around 1895: The poet provided a generous setting for the dramatic arts, music, and literature. Isadora Duncan and Mata Hari also performed at her events.

1898 to 1991

How can it be that an artist who was well-known and successful during her lifetime has been forgotten—and even her work has sunk into obscurity? How can it be that her paintings, which capture the spirit of their time like novels, are nowhere to be seen and are no longer traded on the art market?

These questions arise when looking at the works of British artist Doris Zinkeisen. Like her sister Anna, she captured the lifestyle of the upper-class bohemian set on canvas between the 1920s and 1950s, just as Evelyn Waugh and Nancy Mitford did in their novels: Glamorous portraits of artists, society ladies, and industrial magnates radiate from the picture frames, and women with bobbed hair and red lips in elegant gowns gaze resolutely into the new century. And then, as we continue to look at Zinkeisen’s pictures, the emotional shock: images of corpses in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp after the end of the war, scenes of naked, emaciated survivors being washed by fat women dressed in white, paintings of wounded soldiers being transported by the Red Cross in Ostend and prisoners of war being fed at Brussels airport. How does all this fit together? And why do we know so little about this artist, who became a style icon herself, was an outstanding show jumper, and volunteered as a nurse? Maybe it is because Doris Zinkeisen did not break with figurative painting at the start of the twentith century like many of her contemporaries, and also took on well-paid jobs in theater and showbusiness. Still, as a realistic society painter, she became a star in England—like the Hungarian-British portrait

Society painter, theater and costume designer, later war artist: From the 1920s onward, Doris Zinkeisen became a publicly visible artist in England.

Self-portrait from 1929.

Like her sister Anna Zinkeisen, also an artist, Doris Zinkeisen was one of the “new feminine beauties” and was also viewed as a creative style icon by the press. (right)

painter Philip Alexius de Lázló—during a time of social, political, and economic instability.

Doris Zinkeisen’s early success also had to do with the fact that, from childhood, she always did what she loved most and was best at: painting. Born two years before the turn of the century into a middle-class family in Scotland, she—like her sister Anna—did not attend any formal school, but spent much of her youth drawing and painting. From 1909, she attended Harrow School of Art and in 1917, as an outstanding graduate, received a scholarship for the Royal Academy Schools in London. At that time, women were a minority in art schools, because at the start of the 20th century, there were debates about whether it was proper for women to take the essential life drawing classes with male nude models. Naked men or not, it was difficult for female artists to carve out a serious career and earn money with their art. For example, Dame Laura Knight was admitted to the Royal Academy in 1936 as the first woman since the painters Angelica Kauffmann and Mary Moser, who had co-founded the Academy in 1768.

Zinkeisen in her studio. Through her work as a costume and stage designer in theater and film, interior designer, and consultant to the stars, she helped shape what we would now call pop culture before World War II. (below)

Doris and Anna Zinkeisen were fortunate that as art students, their talent was noticed not just by teachers, but also by newspapers. It did no harm that the striking sisters looked just like the “flappers” who were all the rage in the 1920s: young women with short skirts and short hair, listening to jazz and confidently breaking the “rules of good behavior.” The Zinkeisen sisters were the perfect fit for a world of stages. It was also actor and theater manager Nigel Playfair who introduced Doris Zinkeisen to the world of theater. She soon created portraits of actors including Elsa Lanchester and designed stage sets and costumes, for example for Noël Coward’s hit musical “On with the Dance.” She created thousands of costume designs for the major London theaters, often present at fittings, supervising how the cut and fabric worked in the overall production. Even as a portrait painter, Doris considered the art of mise-en-scène: she was inspired by medieval and ancient Egyptian art, designed matching outfits for her models, and made sure the men and women posing for her looked flattering, powerful, and noble.

When the British film industry developed the “talkies” in the 1930s, attracting millions of viewers, Doris Zinkeisen was one of the creative minds who visually defined the new medium after the silent film era. She designed costumes for about 20 films and wrote a script for the production “The Blue Danube: A Rhapsody”. Since everything was shot in black and white, Zinkeisen had to experiment with the effects of fabric qualities and color shades and use them accordingly. She focused not only on costume design, but also helped the stars with full-scale makeovers, taking care of hair styling, makeup, speech training, and their appearance as a whole. Doris Zinkeisen was thus even credited with stimulating the British textile industry during the economically difficult interwar years. This was because the clothes worn in movies at that time were an important part of the appeal of movie theaters and fueled the audience’s desire to buy. Zinkeisen became so well known to the general public that she was in demand as an interview partner for styling advice, even modeling her own best designs. In 1930, The Morning Post called her “one of the best-dressed women of today.” An excellent show jumper, she competed in major competitions and won the Supreme Hack

1927 to 2024

After a tragically failed marriage, she went straight from a psychiatric hospital into the world of fashion—and became the secret queen of New York. Or, at least, the queen of the New York of clothes, by which America’s rich, beautiful, and powerful still define themselves to this day, rather as Tuscan aristocrats once did in the city-states of the Renaissance.

When Betty Halbreich died at the age of 96, she had followed her first predictable life as a society wife with a second life, in which she simply did what millions of women around the world do for a living: selling clothes. In a department store. The petite American woman with the quickfire wit of a sitcom writer and finely chiseled Audrey Hepburn-style profile became famous for persuading US President Ford to carry his wife’s dresses home like a dutiful husband. Betty Halbreich dressed Meryl Streep and Cher as professionally as Miss No Name, and selected the wardrobe for the film heroines of “Sex and the City” and “Gossip Girl.” Lena Dunham, a Betty fangirl, was delighted to be photographed with her—as were some unknown women on Madison Avenue who were admirers of the grande dame. But despite all the glamour, Betty Halbreich remained a no-nonsense woman. She advised even the world’s wealthiest women to save money and proclaimed in her books: “Don’t wear your wardrobe—wear yourself.”

A chin-up New York legend: Personal shopper Betty Halbreich was in her forties when she turned her passion for fashion into a successful career.

No one could have predicted that Betty Samuels, from Chicago’s wealthy Jewish

»IN

bourgeoisie, who married happy-go-lucky Sonny Halbreich in a whirlwind at 19, would reinvent herself as a businesswoman after their dramatic breakup. But her story is genuinely one of female emancipation. A transformation. A second coming of age. A post-separation liberation. Maybe this story could only happen in New York, the city of big money and people aspiring to be better, smarter, and cooler than anywhere else. And yes, as crazy as it sounds, “Bäddi” only became an icon in her 80s and 90s, surrounded by all those Botoxed, lifted, and spray-tanned women. Another Iris Apfel. A silver-haired legend.

AM THERE AS A WITNESS.«

In the 1930s, this only child had clothes, not children, as playmates. From an early age in the Hyde Park community in Chicago, where many families had German origins, the little girl quite simply found dressing up enchanting—velvet negligees, high heels, and glittering jewelry belonging to her mother Carol, who looked like a lighter, prettier version of Diana Vreeland. Betty adored her parents’ walk-in closets, put on her mother’s clothes, and paraded around in them. Enveloping herself in her mother’s clothes made her feel close to her, precisely because the glamorous woman was so often absent. All the more reason, then, for her daughter to find solace in the magical world of highly polished Mary Jane shoes and Peter Pan collars, which proved an effective cure-all for her school-induced stomach aches. Her art-loving mother, who had been given a white marabou jacket by US photographer Victor Skrebneski and wore a hat trimmed with cherries in winter, was the ultimate style icon for little Betty. And so it was no surprise that Betty—who would herself grow up to be a beauty—developed her own unique style. Small and slender, with the expressive face of a silent film star, witty and quick-thinking, she soon became a celebrated debutante who was set to conquer New York.

Refuge: in blue Her beloved family apartment on Park Avenue was Betty Halbreich’s home from the 1940s and the place where she welcomed guests in her highly cultured, old-fashioned manner until shortly before her death.

Shortly before her wedding in 1947, she had said to her husband: “I can’tgo with you to New York! I am frightened and not ready.” But the young beauty went through with the marriage despite her cold feet, became an Upper East Side housewife, better known as a socialite, and had two children, John and Kathy. “From a childhood to a child bride to a childish mother,” she later wrote in descrikption of this post-war period. A career? That was never an option for her, on the grounds of either education or social class. Instead, she and her husband immersed themselves in the world of elegant high-rises on Central Park. She hosted dinner parties for 12 to 14 people in the blue dining room of her eight-room apartment on Park Avenue, created huge flower arrangements, and drove all over town to buy beeswax candles that matched her tablecloths. She loved her children, of course, but found the daily routine with them rather boring. Shopping became her way of filling the inner void.

This was the golden era of department stores, with doormen, tea salons, and exclusive fur collections: owned by men but ruled inside by women. Before Betty Halbreich’s time, three businesswomen—now largely forgotten—were the visionaries of American department stores. There was Hortense Odlum, who ran Bonwitt Teller as “Woman President” in the 1930s after her husband put her in charge. After the Second World War, Dorothy Shaver was the driving force behind true American luxury fashion at Lord & Taylor, earning a jaw-dropping $1.5

THEY WERE PIONEERS, ARTISTS, POLITICIANS, AND ACTIVISTSand yettheir namesare almost forgottentoday.

From the inventor of modern Bluetooth technology and the first democratically elected president of parliament to the creative mind behind the legendary “I Love New York” slogan, this Callwey book presents outstanding female pioneers who once made a huge impact, and brings them back into the spotlight. Captivating portraits and fascinating facts trace their extraordinary life stories, enhanced by voices of prominent people of today who remind us of their importance.