VINCENZO AGNETTI: WORKING TOGETHER

IS A POLITICAL ACT

Bruno Corà

I have always thought the experiences Vincenzo Agnetti embarked upon along with some of his artist friends had an implicitly ‘political’ foundation and meaning to it. Working together with others in fact, as Agnetti often did, was not only tantamount to uniting skills, techniques, opinions, points of view or other needs while existing, but above all to experiencing creation and knowledge together, thus viewed as civil acts, i.e. those of inhabitants of the civis and therefore from polítēs: citizen, derived from the polis, the city. Moreover, the episodes of sharing in the conception and realisation of shared works always included a phase of dialectical confrontation both in theory and in executive practice, where it must be assumed that there were genuine ideational equivalence and operational complementarity.

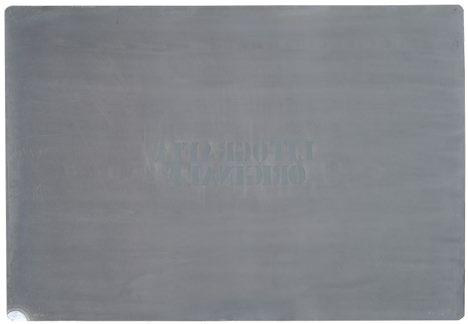

My belief, moreover, is also based of a number of concrete episodes in which I was able to gauge, first hand, the intensity of the emotional relationship developed by Agnetti towards friends such as Enrico Castellani, Paolo Scheggi or Gianni Colombo, during their reflections on aspects of the configuration of the works in exhibition situations. This was the case with the exhibition Vitalità del negativo (1970), when each of the four artists had to give shape to the environments that they had conceived and designed yet still had to define in situ. I recall that, with a certain participatory fervour, Agnetti also coupled his enthusiasm and sensitive complicity in the decision-making process of every one of them when defining their space. In particular, prior to that exhibition phase, Agnetti had already made a shared work with each artist: with Castellani it was the famous Litografia originale [Original Lithograph’] (1970), by means of a metal printing plate on whose two faces the creative partnership emerged – on Castellani’s part with a tautological intervention bearing the words litografia originale, in tall, reversed letters, and on Agnetti’s part with his own critical text surmounted by a diagram of Cartesian axes in white, with a broken zigzag line showing a process of growth. With Colombo, he had worked on the programme Vobulazione e bieloquenza NEG [Vobulation and NEG Bieloquence], a ten-minute television short (made for the Telemuseo exhibition at Eurodomus 3 in Milan, curated by Tommaso Trini) after constructing his NEG. Specifically, while Colombo’s operation consisted of the elaboration of a

basic pattern (the white perimeter of a square) transmitted on a TV kinescope and driven by a vobulatore (an electronic instrument which deforms TV signals by varying the frequency and amplitude of the deflection unit on the horizontal plane), obtaining a programme of dimensional commutations on the pattern itself through very slow transitions between slow, rapid and superfast,

Agnetti’s operation was based on speech (or other sound) completed in the negative with the NEG (his pause detector), thus a foray beyond the auditory threshold that uses silence as its reference point.1

With Scheggi, Agnetti had worked that same year on the creation of the Trono [Throne] (1970), exhibited at the Mana Art Market gallery of Nancy Marotta – the consort of artist Gino Marotta – on Via del Fiume in Rome, and they had likewise devised yet never physically created the work Tempio [Temple] due to the untimely death of the Tuscan artist in 1971.2 And

1 Text published in the catalogue Vitalità del negativo in the section dedicated to Gianni Colombo.

2 An edition of this work was produced in 2021 through the publication of the preparatory drawings in Vincenzo Agnetti, Paolo Scheggi, Il Tempio. La nascita dell’eidos, texts by B. Corà, G. Agnetti, C. Scheggi and others, Forma Edizioni, Florence 2021.

VINCENZO AGNETTIENRICO CASTELLANI. MAZZOLI/MODENA

[FOR FLASH ART ITALIA, NO. 100, NOVEMBER 1980, PP. 49–50]

Two friends, two travelling companions for a quarter of a century, two opposites come together in a remarkable exhibition at the Galleria Mazzoli in Modena, which does not set out to promote “new” artists in particular, but focuses more on the artistic values of the century.

Vincenzo is outgoing, verbose, irascible and caught up in his own vitality, while Enrico is introverted, taciturn, phlegmatic and often maintains a quite Olympian detachment. Vincenzo is intelligent and shows it with relentless dialectics; Enrico is intelligent and shows it with a sphinxlike silence. Vincenzo is a volcano of ideas, whereas Enrico is locked in an almost manic stillness.

Vincenzo is claustrophobic, Enrico agoraphobic. Vincenzo always needs someone to listen to him, Enrico needs someone to listen to. Vincenzo is versatile in the field of art: from calculators that shoot out letters of the alphabet, to photography, Bakelites, performances, sculpture, literature and more; Enrico has developed no more than a few themes, of which he focuses on just one relentlessly. Vincenzo hardly ever repeats the same work: he has to create continuously; Enrico believes only repetition to be the expression of an acquired truth. Vincenzo has an almost adventurous ‘private’ sphere, while Enrico has a very reserved ‘private’ sphere. Vincenzo has an almost reserved ‘public’ sphere, while Enrico has – or rather had – an adventurous ‘public’ sphere. Enrico and Vincenzo tolerate each other indulgently when they are incautious. Enrico and Vincenzo complement each other, both as individuals and as artists.

So, having said that, it is neither unusual nor contradictory to see them exhibiting together, and if there is contradiction, that’s all just part of the real reality of life.

Agnetti presents seven papers painted in opaque black, from which various images stand out as if from prehistoric graffiti: sunny scenes, rough landscapes with vaguely anthropomorphic shadows, twists and tensions cast upon them. These are works of extraordinary effectiveness and evocation, with no precise pattern or guiding line to inspire them, if not the consistency with itself in the freedom to explore in all directions.

Instead, Castellani presents eight white reliefs. So much has been written about his work that it would seem pleonastic to add much, particularly by me who witnessed the birth and development of his work over twenty years ago. But such works always trigger emotions. This time, seeing them hanging, I compared them to the vital rhythm of breathing: the chest rising, expanding in volume as it inhales oxygen and then thins, flattening out as it exhales. There is no need to invent this harmonious rhythm (if anything, we might modify its duration: closer in breathlessness and slower in quiescence), indeed it is impossible, on pain of death.

ENRICO CASTELLANI AND

VINCENZO

AGNETTI

THE POWER OF THE MONTAGE AND THE OPPORTUNITY OF THE WORK OF ART IN THE AGE OF MECHANICAL REPRODUCTION

Over the last five years of his life, Walter Benjamin (Berlin, 1892 –Portbou, 1940) dedicated himself to defining the destiny of art in the context of the radical transformation, in terms of communication and production and how it was triggered, contaminated and corrupted by the diffusion and maturation of the languages of photography and cinema. Benjamin identified in reproducibility the origin of a mutation in the relationship between original and copy, and the disruption of the traditional relationship between art and its audience. The idea of a definition of art in industrialised society and in the system of mass communication of the nascent ‘society of the spectacle’ had already been at the heart of some of the philosopher’s previous speculations, but it only took shape explicitly in the mid-1930s with the essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, in particular through the development and definition of the concept of the ‘loss of aura’. In the complexity of this intuition, the image emerges of the crowd of the modern and contemporary metropolis as capable of definitively supplanting the solitary individual in contemplation, thus driving any subsequent criticism well beyond the sphere of aesthetics and towards the human condition. The work provided a prognosis for the future – a term used by Benjamin himself in the opening pages of the essay – through a perspective developed during the years of the rise of the European dictatorships, in the tragic period of the consolidation of illiberal or oppressive social and economic systems.

Thirty years later, Theodor Wiesengrund Adorno (Frankfurt, 1903 –Visp, 1969), in Aesthetic Theory, further problematised Benjamin’s thesis on aesthetic perception, bringing the question back to the realm of the relationship between subject and object, opening up to the renewed reflections that had begun to characterise the debate on art after its publication and that are re-emerging forcefully today: suffice to think of their declination as regards the theme of artificial intelligence applied to art.

In the wake of The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, the shift from uniqueness to infinite and standardised repeatability, having been theorised, led to an inevitable reflection involving every artist right up to Castellani and Agnetti. Despite stylistic differences in their artistic and existential endeavours, Castellani and Agnetti both investigated the relationship between form and concept, between uniqueness and repetition. While the former sought an idea of spatial infinity in the modular repetition of surfaces, the latter experimented with the concept of replication and variation through the written word and the symbolic meaning of the object. Agnetti’s written pictures corresponded to that expansion of the concept ushered in by Adorno:

[Kosuth and the other conceptual artists] have limited themselves to merely indicative actions, presenting texts written by others, usually linguists or structuralists. On the contrary, I use my thoughts alone; I present works that are texts in themselves, and that, as Adorno says, stimulate the dilation of a concept.1

Agnetti then also adds that: “A concept must necessarily be a text, otherwise it doesn’t work. Now, other objects with conceptual value may

1 M. Perazzi (interviewer), ‘Non dipingo i miei quadri. Il “Concettuale” Agnetti cerca di spiegarsi’, in Corriere della Sera, Milan, 20 February 1972.

2 Ibid.

also be constructed [...] with a written word it is much easier to fabricate a propositional discourse, i.e. a propositional beginning which has an effect that may also be fabricated by the observer.”2

For his part, Castellani went beyond the very concept of the object-picture, which has always been poorly theorised. In fact, Castellani’s works may never be considered objects in the strict sense, nor might they indeed be categorised as such: they can be defined as places, so much so that in 1967 the artist created a work that could be entered and walked through – Ambiente bianco [White Environment’) – working on space through three-dimensional surfaces, using conceptual oppositions in terms, repeating gestures and undertaking highly artisanal operations.

Enrico Castellani and Vincenzo Agnetti met in the early 1950s, when they attended evening classes together at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts. One of the fundamental aspects of their relationship is represented by their experience with the magazine Azimuth, founded in 1959 by Castellani and Piero Manzoni. Azimuth was not just a magazine, but also a gallery (Azimut) and a workshop of ideas that, through a new artistic concept, aimed to open up a dialogue with the international avant-garde. Azimut/h stood out by virtue of its innovative vision, which aimed to dismantle the traditional concept of the unique and unrepeatable work of art, anticipating many of the reflections that would emerge from within the conceptual movement over the following years. In this context, Castellani and Agnetti, and of course Manzoni, debated the themes of conceptual art, reproducibility and the redefinition of the very status of the artwork, leading them to reflect in particular on the relationship among seriality, language and visual perception. Castellani’s methodical and rational approach thus combined with Agnetti’s linguistic and theoretical speculation, creating a fruitful dialogue that would influence both artists over the years to come.

For Agnetti, the concept of multiple was not just a question of technical reproducibility, but a way of investigating the relationship between originality and seriality. In fact, his work appears to be pervaded by the tension between the uniqueness of the concept and the repeatability of the work. An emblematic example is Feltri [Felts’) – works on industrial fabric

on which incisive and lapidary phrases were impressed to create a short circuit.

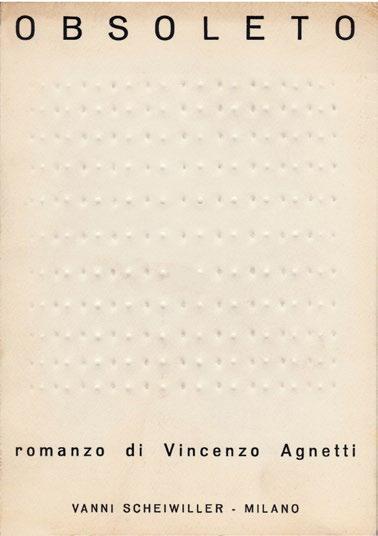

In this sense, a fundamental work is above all Obsoleto [Obsolete’), one that plays on the concept of loss of function and meaning. Could it be Obsoleto like Castellani’s Obelisco [Obelisk’)?3 A work from 1970 that also toys with the concept of loss of function and displacement of meaning. Obsolescence, understood as the surpassing of an object over time, is closely bound up in the reflection on the loss of aura in the age of mechanical reproduction. Obsoleto, as an anti-novel, marked the start of the Denarratori [De-narrators’) series by Vanni Scheiwiller in 1968, with a print run of 1,000 copies and a relief cover obtained thanks to the use of a matrix designed by Castellani. Obsoleto is the usual, the private object of the aura. But it is also a strategy to “overcome an unchangeable moment,”4 a way to elaborate “the strangest conceptions, a sort of revaluation of the usual expired things.”5

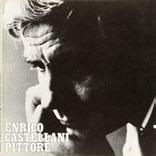

Again in Macchina Drogata (the ‘Drugged Machine’) also by Agnetti, created in 1969 using an Olivetti Divisumma calculator, a technological device subtracted from its original function and transformed into an aesthetic and conceptual object, the themes of the multiple and the variation, of repetition and seriality, emerge forcefully. The machine allowed the artist to affirm difference through similarity. The serial element is therefore not limited to mere material reproduction, but becomes a vector for an investigation into the nature of the work of art. The altered consumer product becomes political, insofar as it contributes to the fixation of an obsolete, discounted, outdated lexicon, triggering hesitation in the face of the mystifying process. His interest is not in the form but in the limits of language: “Thus, a work is valid only if it is identified in a concept for other concepts in a chain until the completion of that mental bridge (intuition, emotion and reasoning) is formed between the work and the onlooker,”6 driving fruition beyond the text and beyond the work of art itself. The machine, ‘drugged’ and thus rendered unusable for calculations, becomes an activator of the spectator faced with the reversal of logic between man and machine. Agnetti also uses the meaning of the obsolete and the usual to talk about Castellani’s work. In Enrico Castellani pittore, a book published by Achille Mauri in 1968 – contained in a box set together with a PVC multiple and initially intended for large-scale distribution – it comes up with regard to the sequence of serial and artisanal work: decomposition and recomposition, fusing and creating. These aspects are further emphasised by the photographic support. Especially the shots by Giorgio Colombo, also in consideration of the graphic approach adopted by the photographer himself, further contribute to emphasising these points and to underlining the repetition of ways and gestures.

As Agnetti writes:

Something was already happening. The painting not to be painted, for example. [...] Before being stretched over the frame, the canvas already had its own path that would eventually become the ensuing painting. And the path (the artist’s work) had already planned the depth that the surface and the arrangement would apparently have to occupy. It is not the work. It is the product that comes out of the material, but the work that removes the material. It occupies it; it replaces it. The frame itself has already been programmed by

3 Enrico Castellani, Obelisco, 1970, frame in chromed metal, elastic strip and sound device, 250 x 80 x 80 cm.

4 V. Agnetti, Obsoleto, with embossed cover by Enrico Castellani and Vanni Scheiwiller, Milan, 1968, edition of 1,000 copies.

points and the points by nails and vice versa. These wood and nails represent the means of a module manifesting; the paintings may all appear the same, constructed in series. The paintings may appear different, by dilating or contracting the module.7

In Castellani’s work, the concept of multiple – or rather, of differently repeating repetition – emerges through the exploration of the modularity of relief canvases. His works, created using nails and underlying structures that alter the classic tension of the canvas surface, were conceived as variations on the same formal principle. Each surface, although unique in its configuration, could be understood as part of a larger whole, suggesting a boundless extension of the pictorial space.

With regard to Castellani’s approach, it is no coincidence that Agnetti remarked: “So we finally manage to exploit it [...] we are witnessing the construction of the unconstructed and unconstructable painting.”8

Already in Azimuth, Castellani himself had laid down the programmatic path of overcoming composition and colour as a spurious problem, to be considered non-essential to the development of art and its artistic conception. And even earlier, in his essay Totalità dell’arte oggi (The Totality of Art Today), he stated unequivocally that:

To speak of monochrome art means in fact to give great importance to the eternal aspect of a movement that is not at all aestheticising [...]. The truth is that monochrome was painting’s last chance to stand apart from the other arts; the surface that it has from time to time described, alluded to, suggested, that has been the theatre of idylls and dramas and vaniloquies, is now silent. A single-colour curtain has fallen on the last act of painting, and it would be futile to linger upon it in mystical contemplation. [...] It is well known that

5 Ibid.

6 V. Agnetti, ‘Trasduzione e sub-valore’, in Data, No. 2, Milan, 1972.

7 Enrico Castellani pittore, with a PVC multiple by Enrico Castellani, text by Vincenzo Agnetti, photographs by Giorgio Colombo, Franco Angeli, Ugo Mulas and Uliano Lucas, published by Achille Mauri Editore, Milan 1968, edition of 1,000 copies.

8 Ibid.

movement is a particular prerogative of today’s art, and that structure is an essential element of movement, but differentiating them makes us fall into the anecdotal, and so movement becomes figurative, i.e. illusory, and time remains extraneous to it. On the other hand, I prefer the engine that moves nothing to any virtual volume, as long as it is well streamlined, a vibrant animated object of power; an ugly painting thrown at supersonic speed remains what it is, and soon disappears from view, but a work that exists by virtue of its physical movement reverses the terms of our problem because, using the scenographic procedure, it tends to regulate time artificially and therefore to falsify its entity, where we give importance to time as the medium of communication itself. My surfaces in canvas or plastic laminate or other materials – plastically dematerialising through the lack of colour as a compositional element – tend to modulate, accepting the third dimension that makes them perceptible; light is now an instrument of this perception: they are abandoned to its randomness, contingent to form and intensity. But no longer part of the domain of painting, sculpture or architecture, being able to assume the character of monumentality or to resize its space, they are the reflection of that total interior space, free of contradictions, to which we tend, and therefore they exist, as objects of instantaneous assimilation, the duration of an act of communication; before time confines them to their material precariousness.9

Another significant example of Castellani’s relationship with the concept of the multiple is Litografia originale [Original Lithography],10 created in 1968 for Edizioni Ariete Grafica by Beatrice Monti della Corte and Giuliana Soprani, considering a statement by Agnetti on the back and meditating on a piece of packaging that has equal value as an object, exactly as in the case of the book Enrico Castellani Pittore. Litografia originale demonstrates the artist’s interest in the transposition of sculptural experimentation into a reproducible format, thus approaching the reflection on the reproducibility of artworks. The lithograph preserves the imprint of language, but its serial nature introduces a new dimension

9 E. Castellani, ‘Totalità nell’arte d’oggi’, 1958–59, in Zero, No. 3, Düsseldorf, 1961; in F. Sardella, Enrico Castellani. Scritti 1958–2002, Abscondita, Milan, 2021.

10 Enrico Castellani, Litografia originale, with a declaration on the back by Vincenzo Agnetti, lithographic plate in zinc, 99 x 69 cm, Edizioni Ariete Grafica, Milan, 1968, edition of 99 copies.

to the concept of uniqueness and repetition, redefining the boundaries between the original and the copy.

Whereas in Castellani’s case the modularity of the surfaces suggests a potentially infinite extension of the work, without however removing its aura, Agnetti instead exploits the concept of repetition as a process of reflection on the loss and recoding of meaning.

In his Feltri series, the lettering and flavour of which are not unlike those of Litografia originale, the idea of seriality is linked to a deconstruction of language and the object, in a process reminiscent of Benjamin’s reflection on the transformation of art in modernity. Castellani, on the other hand, uses reproducibility in an exquisitely artisanal way as a tool to expand the perception of space and form. As he himself states:

monochrome painting or painting in the absence of colour, painting of a surface that is treated solely and almost mechanically, seems to be the adequate and necessary response in a new society that is experiencing the crisis of individuality; where the person is numerically identified, but where the person as a subject has increasingly limited spaces for expression.11

In the work Litografia originale, it is expressly stated that the matrix goes beyond the construction of the original product and through the dimension of quantity. The work becomes a conductor, a medium, yet without losing its pre-eminence. Are we defining the aura of the multiple here? The zinc plate created by Castellani to produce multiples finds meaning in Agnetti’s own words:

The matrix object, in fact, also manifests itself in the possible reproduction; but inevitably ends up justifying only the consequential value of the reproducible. Therefore, it is no longer the debasement of a starting point (original lithography) consumed in the potential repeatability, but the value of the possible used to the detriment of repetition. An ideal multiple, reflexively reflective, in the form of uniqueness to further exacerbate the reference to primary art. In short, matrices with an established party. So let us say it frankly once again: demystification is achieved by mystification.12

Precisely as a result of the considerations regarding Benjamin’s thinking in artistic practices, a reflection began on the possibilities of denying the artistic object and on the concept of the work ‘without works’,13 accepting that the aura – the attribute par excellence of the work of art – could pass from the work to the artist. In these terms, it would be the artist who decides to appropriate an object with his gesture, shifting its register and meaning, just as Castellani did by conceiving works such as Il muro del tempo (The Wall of Time), Obelisco and Asse di equilibrio (Balance Beam) with metronomes or scales weighing letters.14 Benjamin had also explored the link between medium and profane illumination, the utopian instant or duration of the image, the transformation of an experience of thought into an image of thought. This is the call to the operationalisation of the imagination: an unpredictable and infinite construction that requires the perpetual

11 E. Castellani, ‘Il problema del colore, 1965–66’, in F. Sardella, Enrico Castellani. Scritti 1958–2002, cit.

12 V. Agnetti, in Enrico Castellani, Litografia originale, cit.

13 O. Paz, L’apparenza nuda. L’opera di Marcel Duchamp, Adelphi, Milan, 1990.

14 Enrico Castellani, Il muro del tempo [The Wall of Time], 1968, installation of eight metronomes each

iteration of movements that are initiated, contradicted, unprecedented in the continuous possibilities of change, variation and shifting. The construction takes place on two distinct levels that involve the arrangement to expose the relationships between things and the montage. The assembly is always handcrafted, manual and instrumental, and produces differences and relationships, so much so that the appearance and technical structure of the creation is akin to playing with Lego, practising DIY or other forms of assembly.

Following this line of thought, the recent reinterpretation of the essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction by Georges Didi-Huberman (SaintÉtienne, 1953) appears illuminating, especially when compared to the dialectic of multiples and the reproducibility of the works of Enrico Castellani and Vincenzo Agnetti. In the definition of aura: “the unique appearance of a distance, however close it may be,”15 the concepts of distance and appearance remain fixed, while the concept of ‘one’, of ‘unique’ is subverted. The strength of the image therefore lies in the fact that it is never the only image, but rather it is to be found in the montage. In other words, the strength lies in

the multiplicity, the differences, the connections, the relationships, the alternatives, the alterations, the constellations, the metamorphoses. In a word, in the montages.16

set to a different frequency; Obelisco, cit.; Asse di equilibrio, 1971, installation of five scales, each bearing an aluminium tube or a wooden beam.

15 W. Benjamin, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, in Illuminations, Hannah Arendt (ed.), Mariner Books, Boston, 2019.

16 G. Didi-Huberman, Illuminazione, immaginazione, montaggio, Paginette, Festivalfilosofia, Modena, 2008.

Piero Manzoni, Tavole di accertamento, 1958

otto fotolitografie, prefazione originaria firmata da Vincenzo Agnetti

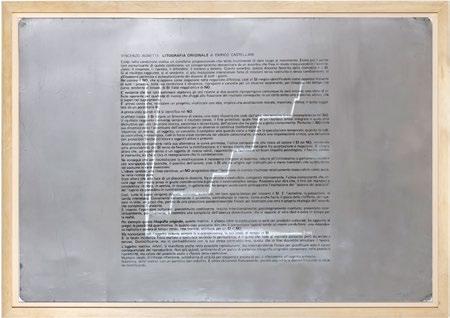

VINCENZO AGNETTI LITOGRAFIA ORIGINALE DI ENRICO CASTELLANI

In a static state, there is a proportional corollary that seeks in vain to trigger movement. Then there is the communicative bearer of this condition; a behaviour named by an adverb that unequivocally establishes its acceptance: to remain, to repeat, to defend, to systematise.

This adverb, this discourse favoured by convenience is YES. Yes to the result achieved, yes to the product, yes to the intentional revolution made up of motion without substance and without change; yes to the permeated and self-enhancing implementation of everyday discourse.

On the other hand, NO, which opposes in the form of negation in the actual denial – i.e. it negates the YES, better identified as the brake opposing all processes – is dynamic in its condition: it re-proposes and cancels in view of an accelerating becoming; of an integrating over time of a curve tending towards the linear, of YES (false negations) and NO.

It is evident that in their algebraic sum, the actions related to the two adverbs in any case produce an initial zero; a state of active refusal of something new that escapes the achievement of the achieved result; in a certain sense an active no-state that is overcome through the act of overcoming.

It is also obvious that enacting a project or vitalising an idea implies a moral, material and intimate acceptance: one sealed by a peremptory YES.

At first glance, therefore, YES may be identified with NO.

However, YES remains a phenomenon of tiredness, an illusory state that falls from above, one which merely ends its incompleteness with NO.

The result achieved always involves the result itself, the primitive end: the end of a result that is by now integrated, a destructive act for historical reduction, assimilated and long forgotten, of the action which led to that fulfilment. Therefore, the NO dynamic avoids the accentuation of the abstract for a becoming in a constant state of transformation.

In short, an event, an object or a concept is complete only when

temporal speculation is lacking; when the constructive, renewing root – i.e. the vital force contained in the communicating medium – leads to a critical approach, a denunciation with its own active and present physical projections (writings and objects).

Historically, analysing the curve of the premise in its alternation, the only component that manages to isolate YES from NO, influencing the provisional nature of YES so much as to favour mystification, is the onset time that elapses between acceptance and denial. It is thus clear that a valid experiment or research object may easily have a positive psychological impact, the right fascination for the moment, whether one is in a state of resignation or rejection.

It follows that in order to neutralise mystification, we need to integrate to the maximum, to reduce to the infinitesimal or at least with theoretical overlaps, to carry out the positive of the action, i.e. that YES that gives rise to more or less transient intervals, which subdivide the various inventions into custom.

The ideal thing would be a continuous line, a progressive NO where the yes-chronic iteration would be relatively negligible, as occurs in pure research.

So then, in the light of a discourse in the making, between the constructed and the constructible, when historically compared, the only component that to this day is not taken into proper consideration is precisely the much-named time. We might even say that the purpose of making something known – be it in a book, a shop window, a museum, a gallery, etc. – has always been based on the exaltation of the ‘pleasure of the pleasing’ and ‘understood to be possessed through rumination’.

Thus all works are expanded, coloured, haloed in their spacetime to come down on the YES side. It is the acrimony, the palpation, the self-interested vanity. Obviously, by preserving the product and controlling the reserves, the game of re-offering and repeating oneself to the elite also comes easy: a game that, starting from parasentimental projection, ends up as a genuine strategy of the absurd that contaminates the present.

And meanwhile the cultural operator – the pre-constituted constituent, the intentionally intuited; the psychologically blackmailed and intellectually, positively presented – is forced into the complicity of a forgetful absence that opposes the true give-and-take over time in reality.