EDUARDO SOUTO DE MOURA CASA

EDUARDO SOUTO DE MOURA

Born in Porto (Portugal) on 25 July 1952.

From 1975 to 1979 he collaborated in the architectural practice of Álvaro Siza.

From 1981 to 1991, he was assistant professor in his alma mater, and later began to serve as professor in the Faculty of Architecture in the University of Oporto. Own office since 1980. He has been visiting professor at the architectural schools of Paris-Belleville, Harvard, Dublin, ETH Zurich, Lausanne, Mendrísio and Mantova. He has participated in numerous seminars and given many lectures both in Portugal and abroad. His work has appeared in various publications and exhibitions.

In 2001 received the

FRANCESCO DAL CO

Born 29 December 1945 is an Italian historian of architecture. He graduated in 1970 at the University Iuav of Venice, and has been director of the Department of History of Architecture since 1994.[1] He has been Professor of History of Architecture at the Yale School of Architecture from 1982 to 1991 and professor of History of Architecture at the Accademia di Architettura of the Università della Svizzera Italiana from 1996 to 2005. From 1988 to 1991 he has been director of the Architectural Section at the Biennale di Venezia and curator of the architectural section in 1998. Since 1978 he has been curator of the architectural publications for publishing House Electa and since 1996 editor of the architectural magazine Casabella.

Heinrich-Tessenow-Medal in Gold, in 2011 he received the Pritzker Prize, in 2013 the Wolf Prize and in 2017 the Piranesi Prize.

In 2018 received the award “Leone d’oro” in La Biennale di Venezia. In 2019 received the award “Arnold W. Brunner Memorial Prize 2019, American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, U.S.A. In 2022 received the Doctor Honoris Causa La Sapienza, Rome, and Member of the French Academy of Architects; Paris.

In 2023 the Gold Medal from Circulo de Bellas Artes de Madrid.

In 2024 he received the insignia of Commander of Arts and Letters, awarded by the French Minister of Culture, at the French Embassy in Portugal, Lisbon; Praemium Imperiale Award 2025.

Dominique Machabert is a journalist, author, and teacher of architecture. From his encounters with Álvaro Siza (Pritzker 1992), Eduardo Souto de Moura (Pritzker 2011), and other representatives of the Porto School, he has written and translated numerous texts, positioning himself more as a storyteller than a specialist, and serving as the voice in France for a movement which, through its discretion, has become an essential expression of contemporary architectural production.

DOMINIQUE MACHABERT

FRANCESCO DAL CO

NON-PEDIGREED ARCHITECTURE

In 1961, the Sindicato Nacional dos Arquitectos in Lisbon published Arquitectura popular em Portugal, two volumes containing the results of the Inquérito survey carried out between 1955 and 1960 into the regional characteristics of architecture in Portugal. As we read in the Introduction, the conclusions reached by the book are unequivocal: não existe, de todo, uma “Arquitectura portuguesa” ou uma “casa portoguesa” (there is no such thing as a typical Portuguese architecture or a typical Portuguese house). And yet, Arquitectura popular em Portugal is often mentioned as the premise of the style characterizing Portuguese architecture during the past decades and decreeing its success. This is a rather paradoxical outcome. The key contribution made by Arquitectura popular em Portugal was to resolve, as far as Portugal was concerned, a lack of knowledge preventing people from realizing that the archetypes feeding contemporary architecture, which uses the vague term “tradition” in its spoken language to stand for equally generalist terms like vernacular, spontaneous, anonymous, or indigenous, are actually part of the endless world of nonpedigreed architecture described by Bernard Rudofsky (ArchitectureWithout Architects, 1965).

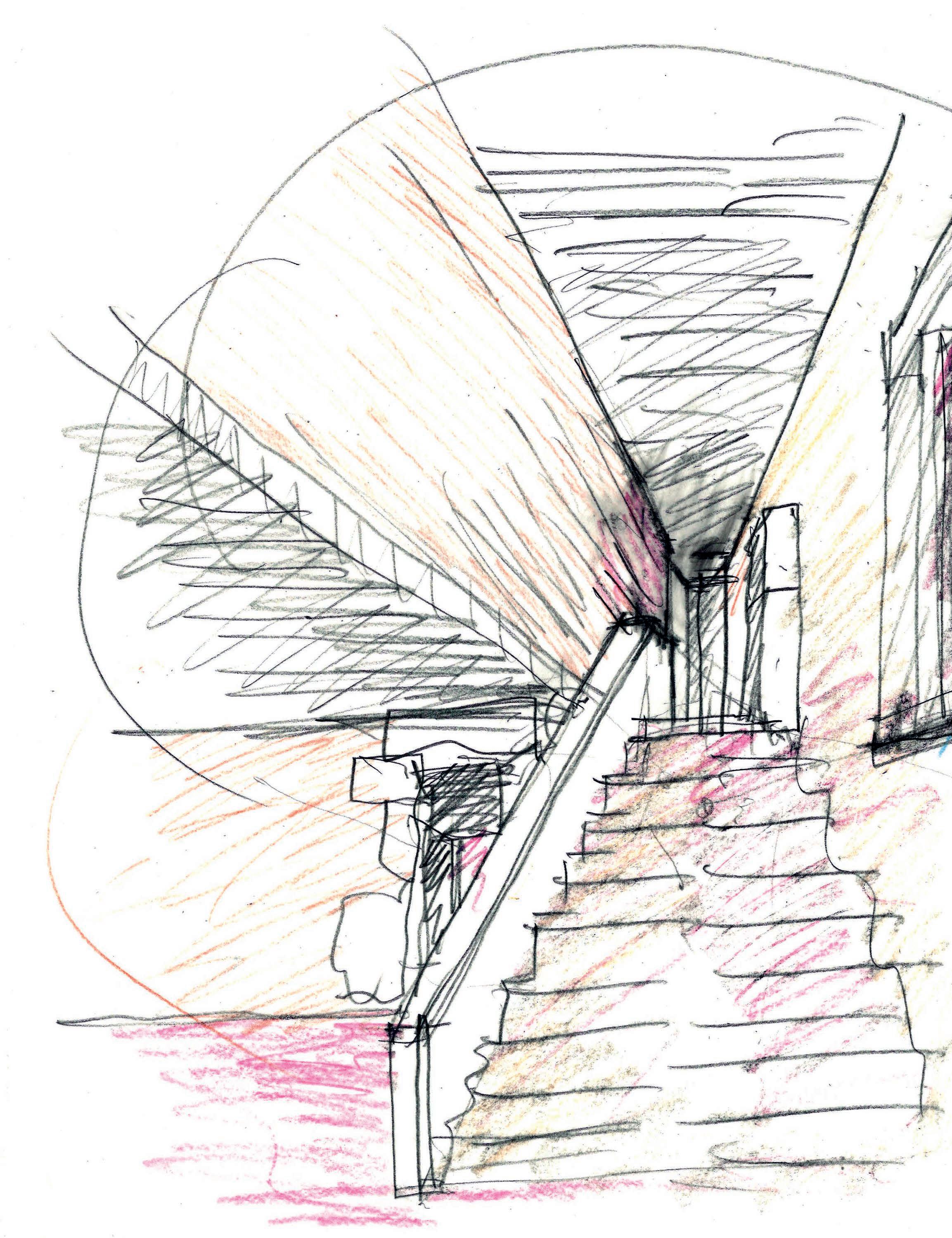

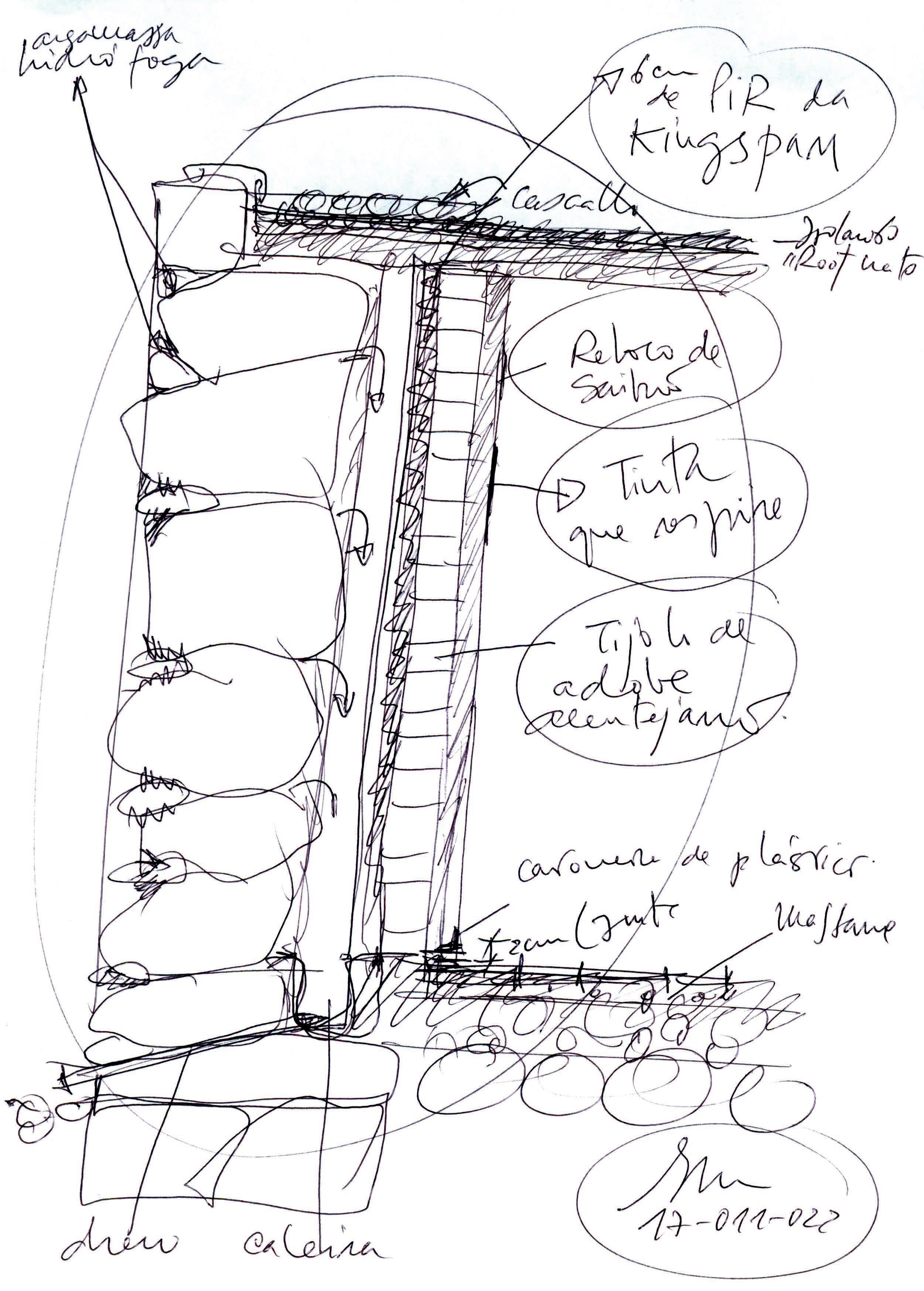

The unpopular conclusion reached by Arquitectura popular em Portugal seems to have been taken to heart by Eduardo Souto de Moura in his reconstruction of a ruined house in Braga. The majority of construction features distinguishing the ruins that inspired him correspond to the descriptions of the constructions typical of “Zone 1” where Braga is situated, a region made of granite, according to the section of Arquitectura popular em Portugal entrusted to Fernando Távora. Souto de Moura merely rebuilt the walls of his ruin, following the suggestions provided by the parts that had not collapsed, reproducing their tectonics. He has emphasized a characteristic typical of vernacular constructions in this region, regarding the function of the jambs comprising parallelepiped ashlar blocks mounted vertically and mainly monolithic architraves that interrupt the fabric of the differently sized blocks and forms of the walls where there are no schist inserts. To highlight the play of voids and volumes created by the apertures and walls, Souto de Moura adopted slim frames, whose uprights were inserted into channels running through the side ashlars. He built an ashlar course to align the upper sections of the perimeters of the volumes forming the house, now protected by a reinforced concrete roof. A small separate building was constructed using the same technique, which involved respecting all pre-existing features even when no longer associated with a function.

As in the case of the external staircase, now a surreal ready-made with no other purpose than to declare its own presence, the stone brackets jutting from the masonry, and the columns belonging to what was formerly a pergola. Inside, the essential distribution has been maintained.

The kitchen space has maintained its central position while the main work space has been transformed into a living room with an adjoining patio, and the bedrooms have been provided with en-suite facilities. The internal surfaces are whitewashed throughout while the original stone walls emerge in correspondence to the doorways and pre-existing wall niches. What is striking about this construction where everything seems to have been done as in the past, in a manner that is exemplarmente rude, franca e expressiva (exemplarily crude, frank, and expressive, Arquitectura popular em Portugal), is the absence of any complacency along with – paradoxically – a complete lack of anything coyly traditional.

FIFTY-ONE HOUSES PLUS ONE

He had conceived houses, fifty-one of which have been built at the time of writing (I counted them), but none yet for himself. He even said that he was incapable of doing so, much like he had long claimed not to know how to draw windows.

It’s on the second floor of a small building – that he in fact drawn – in a peaceful part of Porto, in Foz, that he lives. Devoid of any sense of ownership, I believe; not inclined to possess things, it seems to me, and yet he is at home there. This is his home, their home. Creating houses for others, yes, that he could do. But becoming his own client, that was another story. The architect knows, more than anyone perhaps, that intention does not always lead to the expected outcome, and often he finds rather than seeks them. That may have explained it: that the dream house only exists in the mind. A utopia that should not be tampered with too much.

Visiting together, in Nevogilde or maybe it was Maia – I do not remember – a house he had built, the lady of the house had made a few remarks to him, judging, in her words, that he had often sacrificed convenience for the drawing. Eduardo had agreed, to be sure, but would nonetheless insist – pleading his case with humour – on the number of divorces averted at the cost of a few concessions to convenience; it was the husbands, he would claim, who had asked him to make them, shifting onto their wives, in truth, what they themselves – with a certain weakness – had not dared to say outright.

It was more than thirty years ago – nearly forty now – and things had changed since then, in terms of drawing, just as they had changed between men and women, between wives and husbands, between partners – so as not to exclude anyone, or discriminate against anyone’s way of being together. The world had changed, and so had its houses. At first binary – day/night, ‘black and white’ as they call them – they had become, he said, more ‘natural’ and, as a result, less ‘composed’; more complex, in short – more like life itself.

The familiar space when it is soutomourian, when rather than a space, it is walls, stairs, bay windows, corridors that we inhabit, life; we who know this, know that Eduardo pushes comfort and cosiness to the limits of drawing so that it gives way to habitable houses with curtains like Távora’s. But also the opposite: when he pushes drawing to the limits of comfort so that it cracks, leaning towards Mies this time, for houses that are uninhabitable except by aesthetes who are indifferent to the notion of comfort, who even find it, without saying so, very ordinary, like curtains.

And as time goes by, one wonders whether use, convenience, life or drawing, art, has the final say, the leading role now that Eduardo, tired of overly rich language, advocates for anonymous architecture.

It so happened that the building in Foz, where he lives, was initially occupied by three owners, who were also behind the project. One of them still lives there, on the ground floor. As for the other two, they decided one day to sell, so Eduardo and Pi bought the second apartment, while Siza took the first one, which became available at almost the same time.

It took this turn of events for Eduardo to become the occupant of a house he designed himself, while remaining unable to do so. He even said, with almost fierce irony towards creative pretension, that when they moved in, they didn’t need to touch anything except the position of the television and reverse the opening of the kitchen cupboards, that was all.

Faced with such an outcome between drawing and practicality, between heaven and earth, one wonders whether it would not be better to always do things this way – the moral of this story – always involve a third party.

Near Braga, in a place resembling one of those old satellite hamlets that people still call villages for contrast, family reasons on his mother’s side had led Eduardo to purchase a plot of land and a ruin with the aim of building a family home, una campagna as they say affectionately in Italy. Something for convenience, one might think, a few days here and there, weekends, birthdays, Christmas and Easter, holidays, children and grandchildren, friends, something resembling a life. Could it be that Eduardo saw something more in this project than just architecture?

The first visit was on a Sunday. The main structure was in place, the house more or less set. And yet it looked like a ruin – not a building, not a work in progress, but a ruin. Like in Vieira do Minho in the Gêres massif, where, for the first time, standing in front of a pile of stones, he, the most talented architect of his generation, had seen his project. And coming across some lines by Guillaume Apollinaire at the same time – he often came across lines at just the right moment – the poet’s words accompanied him: “Prepare, with ivy and time, a ruin more beautiful than the others”1. On condition, he would also say, that it be available and not just made for the mind or for daydreaming.

This is the core of his entire theory concerning the ruin – and by extension, architectural heritage – as in Montreuil with the ‘peach walls’ – remnants of subsistence farming in the Paris suburbs, which inspired Patio houses in Matosinhos. That is his entire theory: that ruins are operative, influential, even beyond the site itself, virtually present, positively absent, if you prefer.

Like at Bouro: a monastery without a roof, discovered with him on the first visit amid near-jungle on a wet market day, with contractor, client, mayor, and priest; and later, once completed, still without a roof.

A ruin at the beginning, a ruin at the end – so that in between, the void left behind might become, rather than a lack, an asset: ‘available’, as he calls it. So that nothing might again be missing from the landscape – positively so; nothing that might appear anachronistic or suspect, even in the absence of a roof. So that what was missing then would no longer be missing. When absence becomes the gesture of a radical operation – without disturbing the existential character of the building, now a pousada, what some would call its soul. But radical, precisely in that by remaining the same, it no longer was at all.

A Miesien architect - which, for me, means, in short, an architect of abstraction, of absence, of the mind, Eduardo Souto de Moura had held in his hands, in order to tame them, the forces, the brutal, real sources, without the mind, that is to say, gravity, thickness, matter. He had become a stone trainer and built walls as if they were tigers or elephants coming to eat from his hand.

If there had indeed been destruction, abandonment and the ravages of time in Bouro, the temperament “of things that fall”2, decline, it was necessary to maintain the decisive character, minus religion, that had wanted these fallen things and kept them going until then. Like the Parthenon in Athens in the state we know it, but virtually intact, and like

the ruins of Tipasa in Noces. And I am surprised that Eduardo did not come across these lines by Camus, written for someone like him.

A ruin - as the end of blind faith in temporal progress, in development – when development yields to the dimension of History that simmers beneath, a low, unbroken drone, an active undertow that holds everything in suspense. Whatever came next, whether we replaced it or not, whether we took positive action or not, the absence as trace is what we call History. Development is not History. And for Eduardo, the absence of a roof is History, much to the regret of Távora, perhaps, who would have liked him to put a roof on the building, for the sake of example, for posterity, which is not History but its closure, its end; to the satisfaction of Siza, on the other hand, who had discreetly encouraged him and would have happily seen him go yet further.

I’m no expert, to be honest, so here, in front of the village house, its campagna, as in Bouro and many other places, I wouldn’t have been able to tell the difference between the remains of the original architecture and the newer additions that have blended in, unless someone had pointed them out to me. I couldn’t put my finger on it, at the junction between the old and the new. And one wonders, deep down, whether the ruin had really existed or whether it was fanciful to take for new what was not new either. This reflects his quest – as a trainer of stone – for anonymity, where language is lost in the night of language, where dust drifts, as it has since we began to build, since we began to speak. ‘Architecture without pedigree’ as I understand what Francesco Dal Co wrote3.

I arrived at his office before dinner to find him drawing a house. The drawing was all black, his sign that something was amiss when spontaneity fails and ease is absent. And I saw him, the most remarkable of architects, darkening the paper. Not that he was Goya at that moment, but that is what I thought.

If it is not from a zero point that we begin, not from some originary departure, some natural state from which all things fall; not from a white page but a black one; if it is not from the Index of God that the spark erupts, then drawing cannot return to the source without losing itself there, without merging into the night of language – what we will vertiginously call anonymity. Origin is a hole where specks of dust float.

That time – our first – we had gone to a well-known restaurant, run by a woman of equally good repute; for her too, life.

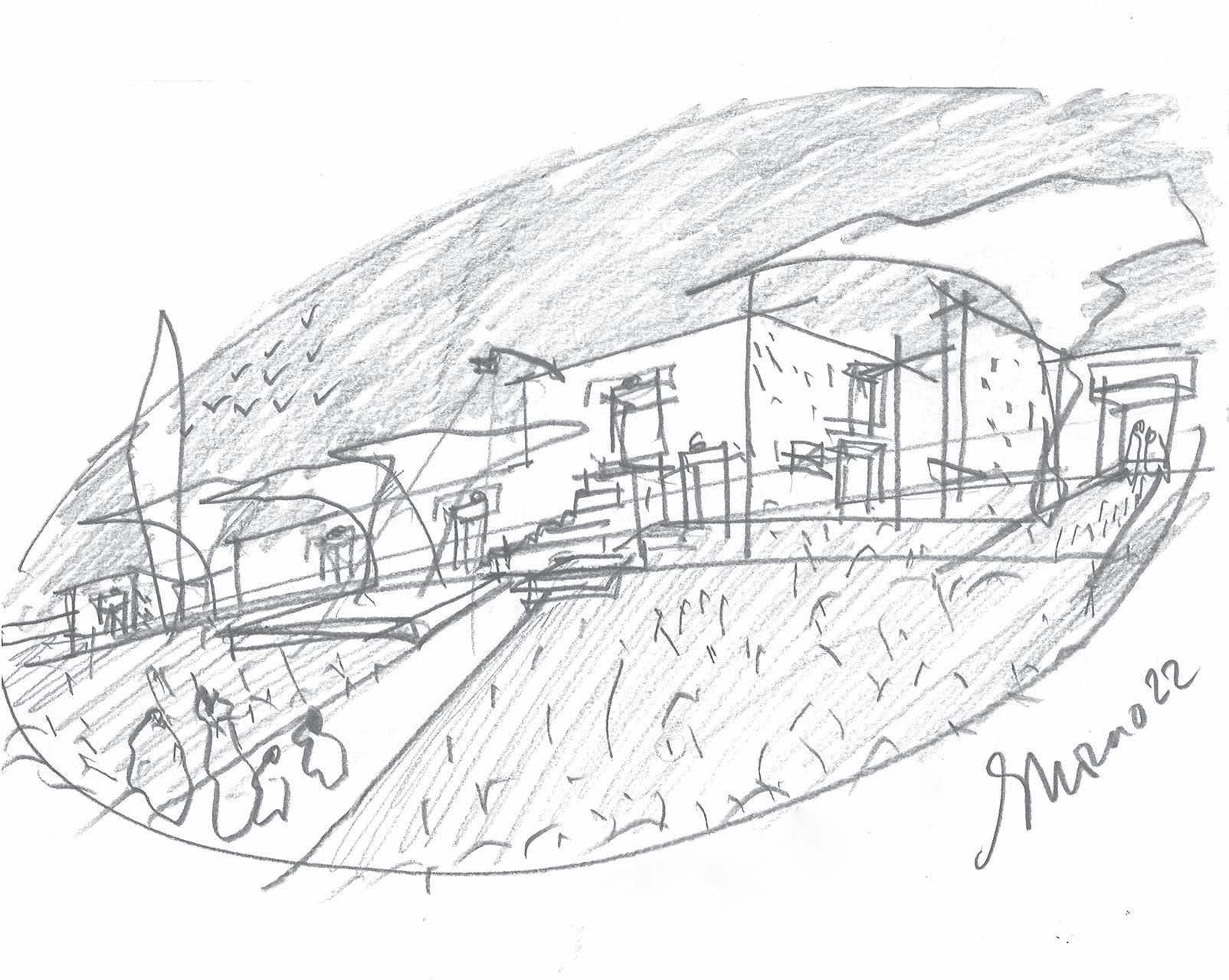

The second time, in summer on a Sunday, we visited the almost finished house. A ruin being patiently constructed. The engineer joined us, and our practical discussion lasted as the sun waned. Then we sat outside on stones awaiting placement.

Sweeping the area with a stick, Eduardo pointed out the small stream in front of us, further away from the farmland, vegetable gardens with someone tending to them – we had come to an agreement with him – the swimming pool on the right, newly planted trees on the left and, on the other side of the road, behind us, a restaurant and a nightclub whose name I have forgotten, as big as the place is small. The Calypso something like that.

Last visit: the ruin was complete. Everything was in place, except for two or three things, some carpets for the bedrooms that he had taken away in his car. It was now liveable,

CASA EM BRAGA

BRAGA, PORTUGAL 2020-2023

A granite ruin, with small adjustments to the openings, so it could respond to the programme. Inside, another house, built in brick, lines the already-manipulated and treated granite walls.

The floor is laid in terracotta tiles, made from the same kind of clay, which we sourced from the Alentejo (S. Pedro do Corval), since in Prado — despite once having had seven ceramic kilns — all of them are now out of use. Nowadays, only drywall partitions are made, as they are more cost-effective.

The roof is flat, made of a concrete slab whose formwork was crafted with pine boards that simulate timber ceilings, using the “tongue-and-groove” system.

To close the exterior openings, we chose steel frames with colourless, non-reflective double glazing. Today, to meet “thermal” standards, glass tends to be green, blue, grey, or mirrored.

Then come the outdoor spaces — arguably the most difficult. We sketched plans that improvised intentions, working on-site like scouts, following the furrows already traced in the ground.

Exterior spaces require time, for we must understand what the land offers and what we wish to propose.

We remain halfway, in no rush to finish, because “Things themselves know when they ought to happen.”¹

We’ll wait and see what happens…

EDUARDO SOUTO DE MOURA

1 David Mourão Ferreira

FEATURED WORK

CASA EM BRAGA

BRAGA, PORTUGAL

2020-2023

Architect

Eduardo Souto de Moura

Collaborators

André Tavares, Elisa Lindade, José Ribau Esteves, Luís Peixoto, Maria Castro, Diogo Guimarães and Pedro Guedes de Oliveira

Structural Engineer

A3R Engenharia – Eng.º Pedro Costa Pereira

Electrical Engineer

GPIC – Eng.º Alexandre Martins

Mechanical Installations Engineer Eng.º João Sousa

Hydraulics

Fluimep – Eng. José Araújo

Acoustics

Inacoustics – Eng. Octávio Inácio

Contractor

Revivis – Rehabilitation, Restoration and Construction, Ltd.

Windows and metal works

Panoramah! – Jofebar

Construction Area

389.66 m²

Site Area

29,779.00 m²

Images

@Miguel Ribeiro

pages 02, 19, 21, 55 , 72 and dust jacket

© Juan Rodriguez pages 04, 10, 12, 22, 26, 29, 31, 34, 40, 43, 47, 51, 52, 59, 63, 67, 70, 77 and 78

@arquivo ESM

pages 11, 17, 20, 36, 38, 56 and 80

AMAG LONG BOOKS COLLECTION brings together a unique selection of projects that establish new paradigms in architecture.

With a contemporary and timeless conceptual graphic language, the 1000 numbered copies of each LONG BOOK will document works with different scales and formal contexts that extend the boundaries of architectural expression.