39 AMAG

INTERNATIONAL ARCHITECTURE

INTERNATIONAL ARCHITECTURE

INTERNATIONAL ARCHITECTURE

and

and

to

Mainly in 3 different series: MAGAZINE, BOOKS and

with a deeply conceptual approach, each collection represents a challenge and a new opportunity for the production of unique and significant books, meeting the highest quality standards and a differentiating design, absent from standard trends, representing significant values and content to inspire each reader and client.

AMAG MAGAZINE (AMAG) is an architecture technical magazine, in print since December 2011, published from March 2023, quarterly and concomitantly, in two series: AMAG (international architecture) and AMAG PT (portuguese architecture). AMAG

É MAIS ARQUITECTOS AMAG 38 AFF ARCHITEKTEN AMAG PT 09 RICARDO CARVALHO ARQUITECTOS AMAG 37 CHRIST & GANTENBEIN AMAG PT 08 CAMILO REBELO

AND

ARCHITECTS school pfeffingen

LB 09 BRANDENBERGER KLOTER ARCHITECTS culture hall laufenburg

POCKET BOOKS (PB) is an assemblage of small publications which compile theoretical texts by various architects or institutions in different collections. These writings reflect different areas of interest and performance in the architectural discourse.

PB 07 ÁLVARO SIZA UNBUILT WORKS | NOTES ON ARCHITECTURE

PB 06 IN CLASS WITH TÁVORA TEACHING AND LEARNING (LIVING) TODAY

PB 05 PAULO DAVID | THE LESSON OF THE CONTINUITY

PB 04 DOING GOOD FAZER BEM DOING WELL

PB 03 NOTES ON ARCHITECTURE BUILDING AROUND ARCHITECTURE FRANCESCO VENEZIA OUTSIDE THE MAINSTREAM

PB 02 FORM, STRUCTURE, SPACE NOTES ON THE LUIGI MORETTI’S ARCHITECTURAL THEORY

PB 01 EDUARDO SOUTO DE MOURA LEARNING FROM HISTORY, DESIGNING INTO HISTORY

Since 2023, AMAG international architecture is out together with AMAG PT portuguese architecture. AMAG SUBSCRIPTIONS grants the OFFER of AMAG PT free of charges, 20% DISCOUNT at all titles from the LONG and the POCKET books COLLECTIONS and EXCLUSIVE PROMOTIONS.

LONG BOOKS brings together a unique selection of projects that establish new paradigms in architecture. With a contemporary conceptual graphic language, the 1000 numbered copies of each title document works with different scales and formal contexts that extend the boundaries of architectural expression. Each title features one single work, from one single studio.

4

4

POCKET BOOKS are an assembly of small books that compiles theoretical texts by different architects. Writings that reflect different areas of interest and performance, in a timeless book collection.

Nestled at the base of a rugged rockside in Henderson, Nevada, Module One is the personal residence of architect Daniel Joseph Chenin, FAIA. Designed as a study in restraint and resilience, the home draws its power from material honesty and a deep-rooted connection to its desert terrain.

Constructed from stacked concrete block and blackened steel, the

structure mirrors the geological formations that surround it, anchoring into the land with quiet force. To achieve a sense of both enclosure and transparency, Titoni Window Steel Systems were selected for their precision craftsmanship and minimal profiles. The slim sightlines allow the architecture to remain the visual focus while enhancing the fluidity between interior and exterior. Their raw steel finish

harmonizes with the material palette, reflecting the same elemental rigor that defines the home itself.

More than a residence, Module One is a personal manifesto, a place where architecture becomes a lived philosophy, shaped by climate, light, and landscape. Rooted in place, it stands in elemental dialogue with its environment: enduring, quiet, and undeniably of the desert.

These are some of the adjectives that define the wellness space at Herdade

designed by the

and with exclusive facial treatments in the

by the

THOUGHTS FROM THE EDITOR by

Ana Leal

by José Manuel Pedreirinho

ABOUT

AMBIVALENCE ORQE

ALADINO HOUSE

CASA

ENFERMEDADES

Pedro Livni (Montevideo, 1973). Curator of the Uruguayan Pavilion at the 2012 Venice Biennale, he is an architect from the University of the Republic of Uruguay (2002) and holds a Master’s degree in Architecture from UC (2011). He currently teaches at Torcuato Di Tella University in Buenos Aires, and is the founder of livni+, based in Montevideo, the architecture criticism platform VOSTOKPROJECT, and the exhibition space 8 ½.

In practice, most architects design. However, some architects both design and build. As Robin Evans noted, the appropriate translation between design and construction lies at the heart of the architectural act. Those of us familiar with the work of Iván Bravo Arquitectos, a studio founded by Iván Bravo in 2002, know that it stems from a particular way of working: the world of construction. Despite the diverse interests of the multifaceted Iván Bravo — who moves fluidly across architecture, design, art, and photography — this assertion is grounded in the fact that, prior to developing his own projects (up until the first decade of this century), the studio primarily focused on building the work of others. This particular way of practicing — and surviving — has led to a condition where Iván Bravo Arquitectos not only develops projects, like most architecture studios, but also, as in most of the works presented here, handles their construction. A dual condition that allows for greater control over the translation and material execution of projects, but which also demands mastery of a wide range of skills and competencies not always found in architects who only design.

Among the works presented here, one aspect that stands out — and can serve as a guiding thread to approach the practice of Iván Bravo Arquitectos — is the presence of what appears to be a dual, seemingly contradictory condition, which I will provisionally call ‘ambivalence.’ To address this, I will begin by commenting on some of the attributes of the project ‘Macizo,’1 which, for me, served as a Trojan Horse to discover Iván Bravo. This work also speaks to the expanded field within which the studio operates, where the boundaries between architecture, art, and execution begin to dissolve.

Contrary to the name of the work2, ‘Macizo’ is a mold made on-site using metal foil on the base and shaft of one of the monumental Corinthian columns that

mark the entrance to the former National Congress building in Santiago, Chile. Two hundred and fifty-four sheets of metal foil were later reassembled — like a puzzle — in a small exhibition space in Montevideo. The resulting piece, an echo of a previous material presence, appears from afar as a massive fragment of a large column. However, upon closer inspection, a careful eye reveals an extremely fragile and hollow object, composed of meticulously assembled fragments. A piece whose origin is stereotomic in its stony quality, yet tectonic in reality due to its resemblance to a textile patchwork. This ambivalence becomes the substantive foundation for the construction of meaning.

This ambivalence also persists in the proper architectural work, and it is arguably the distinctive trait that situates the production of Iván Bravo Arquitectos within the Chilean architectural context. I refer to the body of work to date — mostly singlefamily houses — which could be perceived as a series of carved solids. Yet in their materially ambivalent reality, they result from the intrinsic logic of timber construction. Clean exterior volumes that, in their reverse, reveal the mechanisms that make them possible.

By dispensing with eaves and avoiding the overstatement of structure — a theme prevalent in contemporary Chilean architecture — the body of work by Iván Bravo Arquitectos is reduced methodologically to a repertoire of geometric operations that model volumes. In turn, the work can be read as a continuous series, evolving from project to project. The rigorous autonomy in formal construction is always altered and challenged by a phenomenological sensitivity to the contextual conditions of each commission and site. Orqe House may be described as a chamfered prism; El Gauchal, as two chamfered prisms; Aladino, as the simple

Santiago, Chile

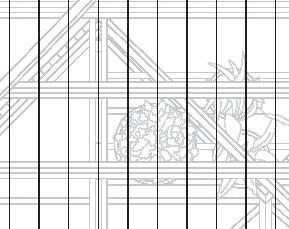

Orqe House is located in a residential neighborhood in northern Santiago. The project explores the essence of a house as a shelter, defined by a single continuous envelope. The design abstracts the traditional gabled roof, enclosing an interior with a familiar spatial organization. Every functional element is positioned in a logical and anticipated manner, allowing the house to integrate seamlessly into daily life.

Built on uneven terrain, the house is partially buried toward the street and opens to the north, where a common space extends into an outdoor terrace. This configuration reduces the distinction between inside and outside, with a beam framing the patio as a flexible transitional space. It can be covered for shade, left open in colder periods, or simply remain exposed, allowing life to unfold between the built and natural environments.

The house consists of a single wooden shell, where walls and roof merge into one continuous surface. The volume encloses private spaces to the south while opening communal areas to the north. Its compact and unadorned form recalls traditional barns in southern Chile, designed for protection rather than ornamentation.

The structure is built from rough, unplaned wooden slats resting on a concrete base. The untreated wood allows for natural aging, changing in texture and color over time. This approach prioritizes structural clarity over decorative finishes, reinforcing the house’s elemental character.

The roof, as the project’s defining feature, serves as both shelter and enclosure.

A singular surface, it protects against wind, rain, and sun while unifying the entire structure. By minimizing extraneous components, the house functions as a straightforward, adaptable space.

Orqe House is conceived as an unfinished piece, completed by its inhabitants. It is a structure that does not impose itself but facilitates habitation, balancing openness and protection. Half cabin, half refuge, it remains a flexible space where life unfolds naturally.

A Orqe House localiza-se num bairro residencial no norte de Santiago. O projecto explora a essência da casa como abrigo, definida por uma única envolvente contínua. O desenho abstrai a tradicional cobertura de duas águas, encerrando um interior com uma organização espacial familiar. Cada elemento funcional é posicionado de forma lógica e expectável, permitindo à casa integrar-se naturalmente na vida quotidiana.

Implantada num terreno desnivelado, a casa encontra-se parcialmente enterrada do lado da rua e abre-se a norte, onde o espaço comum se prolonga numa varanda exterior. Esta configuração reduz a distinção entre interior e exterior, com uma viga a enquadrar o pátio como espaço de transição flexível. Pode ser coberto para criar sombra, deixado aberto em períodos mais frios, ou simplesmente permanecer exposto, permitindo que a vida decorra entre o construído e o natural.

A casa é constituída por uma única casca de madeira, onde paredes

e cobertura se fundem numa superfície contínua. O volume encerra os espaços privados a sul, enquanto abre as áreas comuns a norte. A sua forma compacta e despojada evoca os celeiros tradicionais do sul do Chile, concebidos para a protecção e não para a ornamentação.

A estrutura é composta por ripas de madeira bruta, não aplainada, assentes sobre uma base de betão. A madeira não tratada permite o envelhecimento natural, alterando-se em textura e cor com o tempo. Esta abordagem privilegia a clareza estrutural em detrimento dos acabamentos decorativos, reforçando o carácter elementar da casa.

A cobertura, enquanto elemento definidor do projecto, serve simultaneamente de abrigo e de invólucro. Superfície singular, protege do vento, da chuva e do sol, ao mesmo tempo que unifica toda a estrutura. Ao minimizar os elementos supérfluos, a casa funciona como um espaço directo e adaptável.

A Orqe House é concebida como uma peça inacabada, completada pelos seus habitantes. Trata-se de uma estrutura que não se impõe, mas antes facilita a habitação, equilibrando abertura e protecção. Meio cabana, meio refúgio, permanece um espaço flexível onde a vida se desenrola naturalmente.

Navidad, Chile

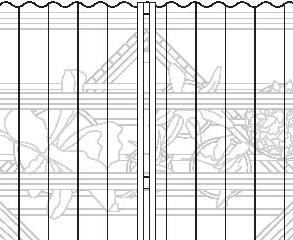

El Gauchal House is located a few meters from the coast, overlooking Navidad Bay in central-southern Chile. The site is where a typical forest of the region meets a previously industrial coastline, now being redeveloped as a holiday destination. The project was commissioned by four families — 14 people in total — who decided to share a second home. Their diverse requirements are brought together in a single volume, constrained to 111m².

Unlike the typical low-rise beach houses in Chile, this structure rises vertically to maximize views from the upper terrace while avoiding obstructions from neighboring homes. Elevating the house alters conventional spatial organization, shifting the relationships between spaces along a vertical axis.

The project follows a repetitive logic in both plan and section, creating symmetry that dissolves a single dominant orientation, like the silhouette of the house that remains identical in plan and elevation. A central void runs through the entire house, accommodating circulation while expanding the perception of shared spaces. Four identical private rooms — one per family — are placed at opposite ends of each level, ensuring equal proximity to the core. The uniform room sizes eliminate exclusivity, making the house function like a shared retreat.

Externally, the massing is defined by a single design move that folds the main façade and roof, blending them into a continuous form. This operation obscures the usual distinction between walls and roof, unifying the structure.

Perpendicular and oblique axes interact, guiding the placement of openings, site boundaries, and external pathways.

The house is entirely built of wood, with concrete floors that vary in texture — smooth and polished outside, rougher inside. The walls are clad in untreated wooden planks with distinct finishes: an inert gray interior, softening the sense of newness, and a bright white exterior that shields against coastal conditions, acting as both a protective shell and reflective surface.

A El Gauchal House situa-se a poucos metros da costa, com vista sobre a baía de Navidad, na zona centro-sul do Chile. O terreno marca o ponto de encontro entre um bosque típico da região e uma linha costeira anteriormente industrial, actualmente em processo de reconversão como destino veraneio. O projecto foi encomendado por quatro famílias — catorze pessoas no total — que decidiram partilhar uma segunda habitação. As suas exigências diversas são reunidas num único volume, limitado a 111 m².

Ao contrário das habituais casas de praia de um só piso no Chile, esta estrutura ergue-se verticalmente para maximizar as vistas a partir do terraço superior, evitando ao mesmo tempo as obstruções provocadas pelas habitações vizinhas. A elevação da casa altera a organização espacial convencional, deslocando as relações entre os espaços ao longo de um eixo vertical.

O projecto segue uma lógica repetitiva, tanto em planta como em corte, criando

uma simetria que dissolve qualquer orientação dominante — tal como a silhueta da casa, idêntica em planta e em alçado. Um vazio central percorre toda a casa, servindo simultaneamente de zona de circulação e elemento que amplia a percepção dos espaços comuns. Quatro quartos privados, todos iguais — um por família —, distribuemse nos extremos opostos de cada piso, assegurando igual proximidade ao núcleo central. A uniformidade na dimensão dos quartos elimina hierarquias, fazendo com que a casa funcione como um refúgio p artilhado.

Exteriormente, a volumetria é definida por um único gesto formal: o dobrar da fachada principal com a cobertura, fundindo-as numa forma contínua. Esta operação dissolve a distinção habitual entre paredes e cobertura, unificando o volume. Eixos perpendiculares e oblíquos cruzam-se, orientando a disposição das aberturas, os limites do terreno e os percursos exteriores.

A casa é inteiramente construída em madeira, com pavimentos em betão de texturas variadas — suave e polido no exterior, mais rugoso no interior. As paredes são revestidas com tábuas de madeira não tratada com dois acabamentos distintos: um cinzento inerte no interior, que atenua a sensação de novidade, e um branco brilhante no exterior, que protege contra as condições marítimas, actuando simultaneamente como invólucro protector e superfície reflectora.

Santiago, Chile

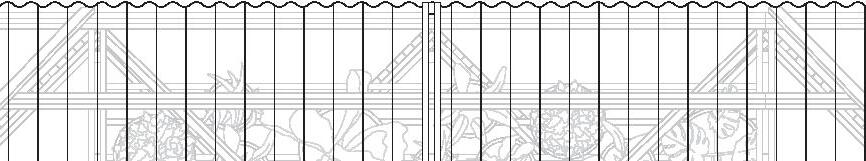

Aladino House is the articulation of two kinds of architectures: residential and utilitarian; contemporary and rural; contrast and mimesis. Both are expressed in a single monumental structure that stands over the landscape.

Located in a clearing in southern Chile, the house is elevated on posts nearly a meter above the ground, allowing streams to flow toward a lagoon in front of the main façade. Its sharply triangular geometry, juxtaposed with the organic surroundings, highlights the contrast between nature and the built environment. The program is divided into two equal halves: one side serves as a reception and storage facility for a private park, while the other houses Aladino, the park ranger. The structure’s geometry dictates that each space follows an identical section, with circulation occurring through a series of central doorways extending from one end to the other.

The absence of corridors eliminates spatial hierarchy, making every part of the building visible as it is traversed. Interior differentiation is achieved through a restrained palette of colors and textures. Materials are sequentially revealed along the house, exposing every joint and construction detail.

On the exterior, the 30-meter-long volume maintains a silent presence through a neutral, monochrome façade with minimal openings, recalling the traditional larch shake barns of the region.

The structural system is fully expressed both inside and out, composed of a uniform dimensional lumber section

spaced 60 cm apart. Transversal beams placed every two modules define spatial rhythm and mezzanine levels.

The rigidity of this system eliminates the need for walls, creating an uninterrupted interior where two roof planes support each other, extending the house’s height to accommodate habitable.

A Aladino House constitui a junção entre dois tipos de arquitectura: a residencial e a utilitária; a contemporânea e a rural; o contraste e a mimese. Ambas são expressas numa estrutura monumental que se eleva sobre a paisagem.

Implantada numa clareira no sul do Chile, a casa encontra-se elevada sobre estacas a quase um metro do solo, permitindo o escoamento natural das linhas de água em direcção a uma lagoa situada diante da fachada principal.

A sua geometria acentuadamente triangular, em justaposição com o carácter orgânico da envolvente natural, acentua o contraste entre natureza e construção. O programa divide-se em duas metades simétricas: um dos lados funciona como área de recepção e armazém de apoio a um parque privado; o outro acolhe Aladino, o guarda-florestal responsável pelo mesmo. A geometria da estrutura dita que cada espaço siga uma secção idêntica, com a circulação a ocorrer por meio de uma sucessão de vãos centrais que se prolongam de uma extremidade à outra.

A ausência de corredores elimina qualquer hierarquia espacial, tornando visível a totalidade do edifício à medida

que se percorre. A diferenciação interior é obtida por uma paleta contida de cores e texturas. Os materiais são revelados de forma sequencial ao longo da casa, expondo cada união e detalhe construtivo.

No exterior, o volume com 30 metros de comprimento mantém uma presença silenciosa através de uma fachada neutra e monocromática, com aberturas mínimas, evocando os celeiros tradicionais de revestimento em madeira de lariço da região.

O sistema estrutural é totalmente exposto, tanto no interior como no exterior, composto por perfis uniformes de madeira serrada com espaçamento regular de 60 cm. Vigas transversais colocadas a cada dois módulos definem o ritmo espacial e os níveis de mezanino.

A rigidez deste sistema torna dispensável a construção de paredes divisórias, permitindo um espaço interior contínuo, onde dois panos de cobertura se sustentam mutuamente, conferindo à casa a altura necessária para albergar espaços habitáveis.

Futrono, Chile

This house was designed for a couple who have never lived together, each residing in their own flats just meters apart in the capital. This holiday home marks their first time sharing a roof.

Located in southern Chile, the house sits in a natural clearing on a long plot ending at a lake, bordered by trees and a small stream. The dense vegetation obscures the surroundings, with only the river’s flow hinting at the lake’s direction.

Humo House explores domestic dichotomies. An 11m cube, split along two facades, organizes the home around contrasts. The larger facades open to distant lake views, while the smaller ones remain mostly closed, sheltering the entrance.

Public areas occupy one half in an all-height open space, while private spaces are stacked across three levels in the other half, designed for the owners and their guests. A central element, a long larch table, dominates the ground floor, serving as both a dining table and kitchen unit. A lowered section allows for comfortable cooking while sharing the same surface as diners.

Two master bedrooms on the first floor — one for him, one for her — are separated yet connected via facing doors and a shared corridor, allowing intimacy without sacrificing independence.

Above, a study overlooks the open space, where the roof’s geometry narrows dramatically before expanding to reach the entire height of the house.

Both interior and exterior are clad in raw timber slats, stained individually to create a rough, weathered appearance that blends into the foggy surroundings.

A winding path connects two ponds, passing through the entrance and terrace before crossing the stream to a fire pit. Beyond the trees, a secluded bay offers the first glimpse of the lake, framed by dense vegetation.

A Humo House foi concebida para um casal que nunca viveu junto, cada um habitando o seu próprio apartamento, separados apenas por alguns metros na capital. Esta casa de férias assinala o primeiro momento em que partilham o mesmo tecto.

Localizada no sul do Chile, a casa implanta-se numa clareira natural de um terreno longitudinal que termina num lago, ladeado por árvores e um pequeno curso de água. A vegetação densa obscurece a paisagem envolvente, sendo apenas o som da corrente a sugerir a direcção do lago.

A Humo House explora dicotomias domésticas. Um cubo de 11 metros, seccionado ao longo de duas fachadas, organiza a casa em torno de contrastes. As fachadas maiores abrem-se a vistas distantes para o lago, enquanto as fachadas menores permanecem maioritariamente encerradas, protegendo a entrada.

As áreas públicas ocupam uma metade da casa, num espaço aberto de pé-direito total, enquanto as áreas

privadas se organizam na outra metade, empilhadas em três níveis, destinados aos proprietários e aos seus convidados. Um elemento central — uma longa mesa em madeira de lariço — domina o piso térreo, funcionando simultaneamente como mesa de jantar e unidade de cozinha. Uma secção rebaixada permite cozinhar confortavelmente, partilhando a mesma superfície com quem está sentado à mesa.

Duas suítes principais no primeiro piso — uma para ela, outra para ele — estão separadas, mas ligadas por portas opostas e um corredor comum, permitindo intimidade sem abdicar da autonomia.

No nível superior, um escritório com vista sobre o espaço aberto acompanha a geometria da cobertura, que se estreita abruptamente antes de se expandir para alcançar toda a altura da casa.

Tanto o interior como o exterior são revestidos com ripas de madeira em bruto, tingidas individualmente para criar uma aparência áspera e envelhecida, integrando-se subtilmente no nevoeiro característico da paisagem.

Um percurso serpenteante liga dois pequenos espelhos de água, atravessando a entrada e o terraço antes de cruzar o riacho até chegar a uma área para fogueiras. Para além das árvores, uma enseada recôndita oferece o primeiro vislumbre do lago, enquadrado pela vegetação densa.

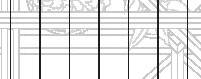

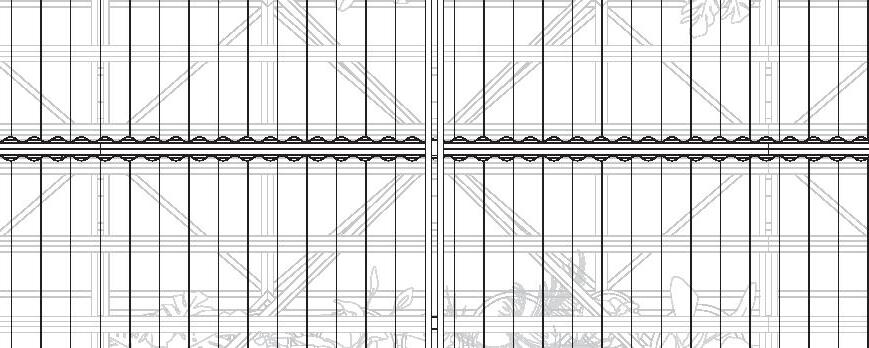

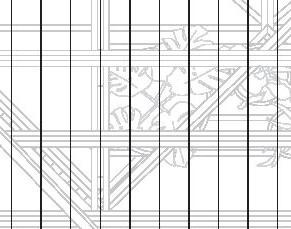

Double layer of Fisiterm insulation, thickness: 4 cm

18. Vertical batten in impregnated pine 1”x2” @ 40 cm centres

19. OSB board, thickness: 12 mm

20. Horizontal bracing (ledger) in dry-dimensioned pine 2”x4”

21. Horizontal batten in dry-dimensioned pine 2”x2” @ 40 cm centres

22. Vertical cladding in dry-dimensioned pine 1”x4”

23. Bottom plate in dry-dimensioned pine 2”x4”

24. Dry-dimensioned pine 2”x2”

25. Perimeter steel beam, double channel 200x50x4 mm

26. Dry-dimensioned pine 2”x8”

27. Lintel in dry-dimensioned pine, double 2”x6”

28. Vertical cladding in native timber, face-fixed

29. Dry-dimensioned pine 2”x3”

30. Steel angle profile 40x40x4 mm

31. Sheet metal with drip edge

32. Window frame as specified

33. Double-glazed (thermopane) glass

34. 4” nail @ 12 cm spacing

35. Polished concrete slab (helicopter finish), thickness: 6 cm

36. ACMA mesh as per structural design

37. Polyethylene sheet

38. Dry-dimensioned pine 1”x4”

39. Dry-dimensioned pine 2”x8” with rebate

40. Composite beam Va4-1+1 Ca 200x50x3 mm

41. Intermediate floor beam in dry-dimensioned pine 2”x8”

42. OSB board, thickness: 12 mm

43. Horizontal cladding in native timber, face-fixed

44. Bottom plate in dry-dimensioned pine 2”x4”

45. Connection bracket to be defined with structural engineer

46. Timber beam Vm1 – 2”x8” impregnated @ 57 cm centres

47. Fibre cement board, thickness: 8 mm

48. Concrete G-17 (90% characteristic strength)

49. Steel reinforcement Fe 4Ø10 mm @ 20 cm centres

50. Steel reinforcement Fe Ø8 mm @ 20 cm centres

51. Natural ground

El Arrayán, Chile

Casa Tam is one more iteration in a sequence of rewritings. It is a comprehensive renovation of a house already expanded and altered on two prior occasions. Somewhere between new construction and palimpsest, the project takes fragments of original layouts and extends them into new spatial continuities, intertwining them with axes from later interventions.

Located on the foothills of the Andes, on the outskirts of Santiago, the house raises its front façade — a gesture of urban character — while turning its back to the mountains. Its roof mirrors the slope it faces, descending nearly to meet the ground and reducing the rear elevation to a thin, semi-buried strip intimately connected to the garden.

The open, double-height area facing the interior garden contains the living-dining room and the main bedroom. The other half, facing the street, accommodates service areas like the kitchen and the owner’s ceramics workshop.

Upstairs, two children’s bedrooms are joined by a central shared studio. In the lower level, the intervention uses reinforced concrete elements that tie together the various construction systems layered across the house’s history. The upper floor is a lightweight construction to avoid overburdening the original foundations, designed for a single story.

The contrast between the different layers of the house’s past remains visible in its interior. Shifts in material appear on surfaces, unified only by a coat

of white paint. Openings — cut through interior and exterior walls — reveal their original wall past, embracing the honesty of the intervention. Outside, the entire house is clad in a standing seam metal skin. While the interior exposes the layering of time, the exterior reads as a monolithic, single-material volume.

In front of the main façade, the only entirely new addition emerges: the kiln room. Clad in wood and painted white, it stands as the signature of this most recent reinvention — a plastic and programmatic trace of the latest rewriting of this home.

A Tam House é mais uma iteração numa sequência de outras reescritas. Trata-se de uma renovação abrangente de uma casa já ampliada e alterada em duas ocasiões anteriores. Em algum ponto entre a construção nova e o palimpsesto, o projecto recolhe fragmentos das plantas originais e prolonga-os em novas continuidades espaciais, entrelaçando-os com os eixos das intervenções posteriores.

Situada nos sopés dos Andes, na periferia de Santiago, a casa eleva a sua fachada principal — um gesto de carácter urbano — enquanto vira as costas à montanha. A cobertura espelha a inclinação que enfrenta, descendo quase até tocar o chão e reduzindo a elevação traseira a uma faixa fina e semi-enterrada, intimamente ligada ao jardim.

A zona aberta, de pé-direito duplo, virada para o jardim interior, alberga a sala de estar e de jantar e o quarto principal.

A outra metade, virada para a rua, acolhe as áreas de serviço, como a cozinha e a oficina de cerâmica do proprietário.

No piso superior, dois quartos infantis são unidos por um estúdio partilhado central. No piso inferior, a intervenção utiliza elementos em betão armado que articulam os vários sistemas construtivos sobrepostos na história da casa. O piso superior é uma construção leve, para evitar sobrecarregar as fundações originais, concebido para um único piso.

O contraste entre as diferentes camadas do passado da casa permanece visível no seu interior. Mudanças de material aparecem nas superfícies, unificadas apenas por uma demão de tinta branca. Aberturas — cortadas nas paredes interiores e exteriores — revelam o passado das paredes originais, abraçando a honestidade da intervenção. No exterior, a casa inteira é revestida por uma pele metálica de juntas de topo. Enquanto o interior expõe a estratificação do tempo, o exterior lê-se como um volume monolítico, de material único.

Perante a fachada principal, surge a única adição inteiramente nova: a sala do forno. Revestida a madeira e pintada de branco, ela ergue-se como a assinatura desta mais recente reinvenção — uma marca plástica e programática da última intervenção nesta casa.

Santiago, Chile

To a certain extent, this project is more a geometric challenge than a conventional commission: fitting a regulation-size tennis court into a residential urban plot. Only then — and within the space left over — does the architectural brief begin: a house for ten people.

The irregular shape resulting from the court’s placement suggested a compact, perhaps vertical, program. As if the project’s catalyst had become its main obstacle. Casa Cruz seeks to do the opposite: to grow from the geometry of the court itself.

The court’s two open edges stretch across the site, becoming the main axes of an eccentric cross. Each arm hosts a part of the program: public areas, children’s rooms, main suite, and leisure. In turn, four distinct patios are formed: entrance, contemplation, relaxation, and tennis. A continuous walkway and overhang run along the entire perimeter, creating a uniform exterior — nearly indistinguishable — acting as neutral boundaries to the space they enclose.

The four short ends of the cross form blind façades, merging with the perimeter walls. The roof is fully walkable, serving as a tennis viewing deck and a hardscape terrace that preserves the surrounding greenery. Inside, each room is defined by the courtyard it faces and the profile of its extrusion. Openings allow windows to slide completely along the facade, dissolving the boundary between interior and exterior. In section, the house becomes a sort of catalogue

of vaults — curved, angular, flat, transverse, longitudinal — while subtle floor shifts reflect programmatic needs. In this way, the interior is experienced as a continuous sequence of diverse spaces, despite the invariable frame that runs along the entire project.

All structural elements are made from solid CLT panels. Exterior components include an insulation core, that along the wood ensure interior comfort without thermal bridges. Exposed faces of the panels are left unpolished, highlighting the raw tectonic character of the material and situating Casa Cruz within the studio’s broader commitment to material expressiveness.

Até certo ponto, este projecto é mais um desafio geométrico do que uma encomenda convencional: encaixar um campo de ténis de dimensão regulamentar num lote urbano residencial. Só depois — e no espaço que sobra — começa o programa arquitectónico: uma casa para dez pessoas.

A forma irregular resultante da colocação do campo sugeria um programa compacto, talvez vertical. Como se o catalisador do projecto tivesse-se tornado o seu principal obstáculo. A Cruz House procura fazer o oposto: crescer a partir da própria geometria do campo.

As duas arestas abertas do campo estendem-se pelo terreno, tornando-se os eixos principais de uma cruz excêntrica. Cada braço acolhe uma parte do programa: áreas públicas, quartos infantis, suite principal e lazer.

Por sua vez, formam-se quatro pátios distintos: entrada, contemplação, relaxamento e ténis.

Um passeio contínuo e um beiral passam todo o perímetro, criando um exterior uniforme — quase indistinto — que actua como limites neutros para o espaço que encerram.

As quatro extremidades curtas da cruz formam fachadas cegas, fundindo-se com as paredes do perímetro. A cobertura é totalmente acessível, funcionando como um miradouro para o campo de ténis e como uma esplanada dura que preserva a vegetação envolvente.

No interior, cada divisão se define pelo pátio que enfrenta e pela forma da sua extrusão. As janelas deslizantes dissolvem a fronteira entre interior e exterior. Em secção, a casa revela um catálogo de abóbadas — curvas, angulares, planas, transversais e longitudinais — enquanto subtis desníveis no piso respondem às necessidades do programa. Assim, o interior é vivido como uma sequência contínua de espaços distintos, apesar da estrutura constante em todo o projeto.

Toda a estrutura é feita de painéis sólidos de CLT. Os elementos exteriores integram um núcleo isolante que, com a madeira, garante conforto térmico sem pontes térmicas. As faces expostas mantêm-se brutas, destacando o caráter cru do material e alinhando a Cruz House com o compromisso do estúdio com a expressividade material.

52.

58.

59.

60.

GAM - Santiago, Chile

Wolf house is a pavilion that houses an exhibition on the creative process behind the eponymous film by León & Cociña. The stop-motion animated film tells the story of a young girl’s escape from Colonia Dignidad, a religious sect in southern Chile.

The architecture of the pavilion translates the oppressive and dark atmosphere of the film, and the real story behind, into a tangible spatial experience.

The pavilion is a labyrinth. Its layout follows a strict mathematical sequence, with a centralized plan and double symmetry, yet all this rigor exists solely to disorient. Turns and counterturns, arranged in a choreography of leftward rotations, confuse those who navigate through it. Four sections surround the central courtyard; two have no exit, while the other two contain a single door that restricts movement in one direction. Four staircases cross the courtyard, altering the circulation pattern, though in practice, they only add to the complexity.

Wolf house is a compressed labyrinth. Instead of relying on vast length, confusion arises from the narrowness of the passages and the repetition of spaces — never identical, yet always similar. Eight square windows allow glimpses into the central courtyard, the only fixed reference point within the blind box that forms the pavilion. Its exterior, made of rustic, austere wood, conceals the meticulously ordered chaos inside.

Four entrances,

corners of the box, break the continuity of the

facades. At the center of the exhibition hall, the pavilion reaches the full height of the space, as if it had always been there or as if it could never be removed.

Wolf house is trapped, and at the same time, it is a trap: an exhibition contained within a courtyard, a courtyard contained within a house, a house trapped inside a building.

A Casa Lobo é um pavilhão que alberga uma exposição sobre o processo criativo por detrás do filme homónimo de León & Cociña. O filme de animação stop-motion narra a fuga de uma jovem da Colonia Dignidad, uma seita religiosa do sul do Chile.

A arquitectura do pavilhão traduz a atmosfera opressiva e sombria do filme, assim como a história real por trás dele, numa experiência espacial tangível.

O pavilhão é um labirinto. A sua planta segue uma sequência matemática rigorosa, com um plano centralizado e dupla simetria, mas todo este rigor existe apenas para desorientar. Voltas e contravoltas, organizadas numa coreografia de rotações para a esquerda, confundem quem o percorre. Quatro secções rodeiam o pátio central; duas não têm saída, enquanto as outras duas possuem uma única porta que restringe o movimento numa só direcção. Quatro escadas cruzam o pátio, alterando o padrão de circulação, embora, apenas aumentem a complexidade.

A Casa Lobo é um labirinto comprimido. Em vez de recorrer a uma grande

extensão, a confusão provém da estreiteza das passagens e da repetição dos espaços — nunca idênticos, mas sempre semelhantes. Oito janelas quadradas permitem vislumbrar o pátio central, o único ponto de referência fixo dentro da caixa cega que forma o pavilhão. O seu exterior, feito de madeira rústica e austera, esconde o caos meticulosamente ordenado do interior.

Quatro entradas, localizadas nos cantos da caixa, quebram a continuidade das fachadas. No centro da sala de exposição, o pavilhão atinge toda a altura do espaço, como se sempre lá tivesse estado ou como se nunca pudesse ser removido. A Casa Lobo está presa e, ao mesmo tempo, é uma armadilha: uma exposição contida dentro de um pátio, um pátio contido dentro de uma casa, uma casa presa dentro de um edifício.

CCU gallery - Santiago, Chile

There are many reasons why we find vegetation inside architectural spaces, yet in almost every case, it highlights architecture’s desire to differentiate itself from nature — reducing plants, at most, to mere ornamentation within an autonomous structure called a building. In doing so, it erases any trace of a shared origin. The museum hall is one such space where architecture strives to conceal its natural reality, transforming it into a backdrop that hides everything we believe we know. A place where the planet itself disappears, leaving behind only representations of it.

From this perspective, the presence of a greenhouse in the basement of a building that proudly embodies this false autonomy becomes unsettling. A space filled with plants and soil, contradicting the notion of a controlled, artificial environment. Like the precious diseases in Cecilia Avendaño’s work — immaculate yet parasitic plant-like figures invading the exhibition hall — the pavilion interprets this condition through a habitable volume. The dirt in the substrate, the marks left by slow but persistent growth, the nearly imperceptible movement of plants seeking the scarce light that filters underground — all of these expose what the museum hides.

The greenhouse embraces its precariousness unapologetically. It is built using the weakest materials available, avoiding any superfluous elements beyond its fundamental role: to shelter and protect plants. This extreme austerity pushes the limits of architectural expression, elevating a large roof, twothirds of which projects outward, unifying

its base. This base consists of three cubic volumes stacked in alignment along a central axis. Resting on top of them is a massive transverse beam, bearing the weight of the 28 floors of reinforced concrete that rise above it. For a few months, deep beneath the city, the weight of modern development rested upon a modest and fragile greenhouse filled with plants — a quiet yet powerful reminder of our own vegetal state.

Existem muitas razões pelas quais encontramos vegetação dentro de espaços arquitectónicos, mas, em quase todos os casos, ela realça o desejo da arquitectura de se diferenciar da natureza — reduzindo as plantas, na melhor das hipóteses, a mera ornamentação dentro de uma estrutura autónoma chamada edifício.

Ao fazê-lo, apaga-se qualquer vestígio de uma origem partilhada. O hall do museu é um desses espaços onde a arquitectura se esforça por ocultar a sua realidade natural, transformando-a num cenário que esconde tudo aquilo que acreditamos saber. Um lugar onde o próprio planeta desaparece, deixando para trás apenas representações dele.

Desta perspectiva, a presença de uma greenhouse no rés-do-chão de um edifício que orgulhosamente encarna esta falsa autonomia torna-se inquietante. Um espaço preenchido por plantas e terra, contradizendo a noção de um ambiente controlado e artificial. Tal como as doenças preciosas na obra de Cecilia Avendaño figuras imaculadas, mas parasitárias semelhantes a plantas que invadem o hall de exposiçõe, o pavilhão

interpreta esta condição através de um volume habitável. A terra no substrato, as marcas deixadas pelo crescimento lento, mas persistente, o movimento quase imperceptível das plantas em busca da escassa luz que filtra do subsolo — tudo isto expõe aquilo que o museu esconde.

A greenhouse abraça a sua precariedade sem desculpas. É construída com os materiais mais fracos disponíveis, evitando quaisquer elementos supérfluos além do seu papel fundamental: abrigar e proteger as plantas. Esta austeridade extrema ultrapassa os limites da expressão arquitectónica, elevando um grande telhado, dois terços do qual projeta-se para fora, unificando a sua base. Esta base consiste em três volumes cúbicos empilhados em alinhamento ao longo de um eixo central. Sobre eles repousa uma maciça viga transversal, suportando o peso dos 28 andares de betão armado que se erguem por cima.

Durante alguns meses, profundamente sob a cidade, o peso do desenvolvimento moderno repousou sobre uma greenhouse modesta e frágil, cheia de plantas — um lembrete silencioso, mas poderoso, do nosso próprio estado vegetal.

Gallery 8½ - Montevideo, Uruguay

Macizo is the vestige of a monumental form stripped — and emptied — of its context. It is the embellished memory of a palace that has lost its identity.

A white elephant in the historical and administrative center of Chile’s capital. The building of the former National Congress of Chile housed the country’s parliamentary functions for nearly 100 years, until the military coup of September 1973 brought its activities to a halt. Since then, it has hosted a succession of bureaucratic agencies attempting to make use of a space that lacks a clear purpose.

Macizo replicates the base of one of the columns at the palace’s main entrance using a thin metallic foil. Like a child’s embossing on a chocolate wrapper, the work’s technique puts the solemnity of the original in tension with the fragile and ephemeral nature of the replica — shiny and precious, like an object of veneration or a death mask for the remains it evokes.

The gallery, just 8½ m² in size, is overfilled by the column’s base. The intrusion of this out-of-place object into what used to be the garage of a residential building in Montevideo — now emptied and completely exposed to the street — challenges notions of dimension and scale. At the same time, it forces a reinterpretation of monumentality and urban significance as seen in the original.

A series of lines and numbers etched onto the metal surface document the creation process, reinforcing the non-material nature of the duplicate. Like a sewing pattern, they suggest the existence

of alternate combinations. Yet they also resemble scales — ready to fall one by one, product of a prolonged decay.

A form without content, echoing the building it replicates. Macizo translates into a spatial and aesthetic operation an architectural reflection on the loss of identity — a memory of an urban ruin, once a symbol of republican pride, now awaiting its next occupation.

Macizo é o restia de uma forma monumental despida — e esvaziada — do seu contexto. É a memória enfeitada de um palácio que perdeu a identidade. Um elefante branco no centro histórico e administrativo da capital do Chile.

O edifício do antigo Congresso Nacional do Chile acolheu as funções parlamentares do país durante quase 100 anos, até ao golpe militar de Setembro de 1973 que interrompeu as suas actividades. Desde então, tem recebido uma sucessão de organismos burocráticos que tentam aproveitar um espaço que carece de um propósito claro.

Macizo replica a base de uma das colunas da entrada principal do palácio usando uma fina folha metálica. Tal como o relevo de uma criança numa embalagem de chocolate, a técnica da obra coloca a solenidade do original em tensão com a natureza frágil e efémera da réplica — brilhante e preciosa, como um objecto de veneração ou uma máscara mortuária para os restos que evoca.

A galeria, com apenas 8½ m² de área, é dominada pela base da coluna. A intrusão deste objecto fora do lugar no que costumava ser a garagem de um edifício residencial em Montevideu — agora vazio e completamente exposto à rua — desafia as noções de dimensão e escala. Ao mesmo tempo, força uma reinterpretação do monumento e do significado urbano tal como visto no original.

Uma série de linhas e números gravados na superfície metálica documentam o processo de criação, reforçando a natureza não material do duplicado. Tal como um molde de costura, sugerem a existência de combinações alternativas. Mas também escamas — prontas a cair uma a uma, produto de uma decomposição prolongada.

Uma forma sem conteúdo, que ecoa o edifício que replica. Macizo traduz numa operação espacial e estética uma reflexão arquitectónica sobre a perda de identidade — uma memória de uma ruína urbana, outrora símbolo do orgulho republicano, agora à espera da sua próxima ocupação.

The best part of the myth of Atlas isn’t his punishment, but his ending.

After carrying the sky on his shoulders for centuries, Perseus confronts him with the gaze of Medusa. He doesn’t die. He transforms. His body hardens into stone, his beard turns to forest, his head becomes a summit. He becomes mountain. Since then, the sky rests upon him.

I like the idea of becoming a mountain — of carrying the sky and also looking at it. Something impossible that, with the right technology, sometimes becomes barely possible.

This is not a retrospective, nor does it explain a method. It gathers certain ideas I’ve been working through over ten years of studio practice. Houses, installations, competitions. Projects developed in different conditions but crossed by similar concerns: how to make architecture from what’s possible — situated and contemporary.

How to let what is often an excess — program, regulations, climate, available materials, construction technologies — become decision, construction, and hopefully, good landscape.

Chile is a country where contemporary architecture maintains an active dialogue with the world, but its construction industry does not. In our office, we work with sophisticated digital tools — and with others that are not. Some highly technical, others analog. Yet buildings are still made almost entirely by hand, often without anyone really looking at the drawings. That friction — between critical ambition and real availability — is not a problem. It’s fertile ground. It’s where ideas are tested. And from there, we move forward.

The solution shouldn’t be conformist, but operate within tension. Instead of applying closed systems, we work with partial assemblies — fragments that function together. This way of making calls for a different character. Not the modern engineer, nor the demiurge architect, but the tinkerer. I like that word. In Spanish it doesn’t have an exact translation. It’s something like a backyard inventor — someone who tests, adjusts, mixes what they have at hand without waiting for guarantees. A minor character, but deeply attentive.

A tinkerer doesn’t follow a method. They assemble what’s available. They fine-tune. They don’t seek total control, but the contingent precision that each case requires.

Sometimes, it’s not even about building something new. Just corrected.

I’ve taken part in several public competitions — some awarded, some developed, but still unbuilt. Sometimes due to the slow rhythm of Chile’s public system. Sometimes just because not enough years have passed. But if I’m going to talk about landscape technologies, I have to talk about built work. And in my case, that means houses and installations. Because it’s in those projects that ideas face the concrete: weight, scale, climate, and the contradictions of execution. That’s where ideas become material, and decisions stop being theoretical.

The building process doesn’t confirm an idea — it tests it. It forces you to think from what’s available. From invention. From trial and error.

I often photograph construction processes with a Canon FX, a 1964 SLR. Not out of nostalgia — I wasn’t even born when it was released — but because there’s something fascinating about documenting a project in progress with a technology that’s over sixty years

Punta Pite, Chile

The house is located on a rocky and stormy cliff between two small bays facing the Pacific Ocean. This situation between seas to the east and west can be felt on the ground, but not seen.

The idea of the project is to generate a house that allows to work both as a refuge and as the opposite; a panorama. Thus, rather than generating a static relationship with the territory, it creates a medium for change. For this, an intermediate condition is designed between exterior and interior, between a natural and an intimate personal landscape. An intermediate gallery like a traditional Engawa of variable section and different densities of raulí wood creates a spatiality capable of reacting to various uses and impulses, both internal and external.

The gallery contains a regular volume of galss ans black steel, of only one level that advances as it rises from the sloping natural topography. As the volume rises, its form of anchorage to the ground changes; Once fully supported, it begins to gain height on regular pilotis that finally end in a quadruple diamond support. This distancing also changes the relationship from a close environment to a distant one, from a close relationship with the garden to one of an environment between seas, a situation previously impossible to see.

The higher you are from the ground, the more public your program will be, until a public upstairs and a private downstairs are generated. Below, a series of scales, platforms, concrete walls and river stones build the exteriors

and gardens of the house, these follow the conditions of the topography, unlike the main volume. Above, in a completely panoramic situation with three sea fronts, there is an unprotected viewpoint against the windy weather.

A casa encontra-se num penhasco rochoso e tempestuoso entre duas pequenas baías voltadas para o Oceano Pacífico. Esta situação entre mares a leste e oeste sente-se no terreno, mas não se vê.

A ideia do projecto é gerar uma casa que funcione tanto como refúgio como, inversamente, como panorama. Assim, em vez de estabelecer uma relação estática com o território, cria-se um meio para a mudança. Para isso, foi concebida uma condição intermédia entre o exterior e o interior, entre a paisagem natural e a paisagem pessoal e íntima. Uma galeria intermédia, semelhante a um Engawa tradicional, com secção variável e diferentes densidades de madeira de raulí, cria uma espacialidade capaz de reagir a diversos usos e impulsos, tanto internos como externos.

A galeria envolve um volume regular de vidro e aço negro, de um só piso, que avança à medida que se eleva sobre a topografia natural em declive. À medida que o volume sobe, a sua forma de ancoragem ao solo altera-se; uma vez totalmente apoiado, começa a ganhar altura sobre pilotis regulares que terminam, finalmente, num suporte de diamante quádruplo. Este afastamento transforma também a relação com

o entorno: de uma envolvência próxima com o jardim, passa-se para um ambiente entre mares — uma situação até então impossível de ver.

Quanto mais alto em relação ao solo, mais público se torna o programa, até que se gera um piso superior público e um piso inferior privado. Em baixo, uma série de escadas, plataformas, muros de betão e seixos de rio constrói os exteriores e jardins da casa — estes seguem as condições da topografia, ao contrário do volume principal. Em cima, numa situação completamente panorâmica com três frentes marítimas, existe um miradouro desprotegido contra o clima ventoso.

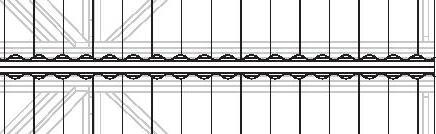

01. Secondary terrace beams UPN 140 (140x60 mm), painted black, RAL 9004

02. Terrace roof decking in lenga wood, 70x15 mm, butt-jointed

03. Pressure-treated pine post 2’’, for roof slope, variable height, spaced approx. every 2399 mm

04. Edge angle 15x15x3 mm for terrace deck, in steel. C-profiles 125x50x5 mm, painted blac, RAL 9004

05. Pressure-treated pine joist for deck structure, 50x63 mm, spaced at 600 mm centres

06. Soffit for north terrace and exterior corridors in lenga wood, 70x15 mm, spaced 70 mm apart

07. UPN 240 beam, painted black, RAL 9004

08. 1+1 back-to-back UPN 240 beam, grid lines B and C between axes 02 and 00, per structural design, in black-painted steel, RAL 9004

09. Bracing 100x50x3 mm, mitred joints at 45º, in black-painted steel, RAL 9004

10. Fixed window in pre-painted matt black aluminium profiles, double-glazing 6+4+6 mm, clear glass

11. Recessed roller blind, 30% openness sunscreen, pearl white colour

12. Edge trim 203x10 mm in timber, painted black RAL 9004, matt finish

13. Pine timber stud 2x3 1/2’’ (50x81.5 mm), pressure-treated

14. Interior ceiling in pine wood 3’’ (70x15 mm), no chamfer, whitewashed

15. C-profiles 110x50x3 mm, with anti-corrosion treatment

16. High-density expanded polystyrene insulation, 80 mm thick, with Tyvek vapour barrier

17. SBS elastomeric membrane, 4 kg/m², over 15 mm structural plywood (1200x2400 mm)

18.

15

19. Adjustable louvre in lenga wood, per Marine Shutters supplier

20. HEB 140 column, painted black, RAL 9004

21. Interior flooring in tongue-and-groove lenga wood boards, 70x15x4800 mm.

22. Composite slab from axis 5 to axis 00, per structural design, Instadeck 12.5 slab, underside painted black

23. Insulation, loose mineral wool mat, fixed to underside of composite slab, 40 mm thick, between axes 05 and 02

24. Radiant floor heating system with PEX pipes, as per project, from axes 05 to 02

25. Lenga wood trim piece at floor level, with chamfered edge

26. Underside ceiling in lenga wood boards, 70x15x4820 mm

27. Lower WF beams 250x44.8 (266x148 mm), longitudinal along axes B and C, painted red, RAL 3000

28. Exterior decking in butt-jointed lenga wood boards, 70x15x4800 mm

29. Transversal beam WF 250x44.8 (266x148 mm), painted black, RAL 9004

30. Capital in metal plates, painted red, RAL 3000

31. Spider foot in HEB 220 profile, painted red, RAL 3000.

32. Staircase in polished concrete, treads and risers.

33. Wall on axis A1 in exposed concrete with formwork in butt-jointed planed timber boards, top surface machine-polished and sealed with transparent QHC.

34. Slab foundation per structural design, machine-finished and polished using Hitek Superfloor system.

35. WF beams 200x19.3 (203x102 mm), painted black, paint as per on-site sample, RAL 9004.

36. Horizontal bracing 75x75x3 mm, painted black, paint as per on-site sample, RAL 9004.

37. UPE 140 beam (140x65 mm), painted black, paint as per on-site sample, RAL 9004.

38. Angle profile 96x200x5 mm, painted black, paint as per on-site sample, RAL 9004.

39. Bracing at axis 00, tubular profiles 100x50x5 mm, painted black, paint as per on-site sample, RAL 9004.

40. Bracing at axis A, tubular profiles 100x50x5 mm, painted black, paint as per on-site sample, RAL 9004.

41. Ø3’’ x 3 mm (Ø76.2 mm) column, painted black, paint as per on-site sample, RAL 9004.

42. Diagonal bracing at axis 00, tubular profiles 100x50x5 mm, painted black, paint as per on-site sample, RAL 9004.

43. Termination piece for Ø3’’ column base, in steel, as per floor detail.

44. Timber handle for louvre in lenga wood, as per detail.

45. Exterior decking in butt-jointed lenga wood boards, 70x15x4800 mm.

46. Ceiling chamfer and bottom edge flat bar, 20x15 mm.

47. Flat plate 270x270x10 mm, recessed in concrete to receive HEB 220 column (210x220 mm), bolted and painted red, RAL 3000, as per on-site sample.

48. Round tubular profile 2’’ x 3 mm (Ø50.8 mm), fixed to concrete wall for support, painted black, as per sample, RAL 9004, end faces sealed with 15 mm lenga wood.

49. Concrete trim 20x30 mm between exposed concrete wall and dark grey polyurethane-based pool coating, as per sample.

50. Wall on axis 01A in exposed concrete with formwork in butt-jointed planed timber boards, top face machine-polished and sealed with transparent QHC, bottom face underground with Igol treatment.

51. SBS elastomeric membrane, 4 kg/m².

Maitencillo, Chile

The project is located on the Chilean coast, between the countryside and the Pacific Ocean, in a Mediterranean climate. In this context, traditional construction technologies typically involve clay brick masonry and wooden trusses.

The house is situated at the edges of a private residential development along the coast. A series of homogenizing regulations, which don’t make much sense to the landscape, are imposed by an architectural guideline. Among them is the requirement for buildings to be white.

Due to its position on the outskirts of the development, the house has the opportunity to disengage from the architectural landscape of the neighborhood, instead focusing on the cultural, natural, and climatic landscapes of the region.

The house is enclosed by a slow, artesanal masonry perimeter with varying densities, creating both interior rooms and enclosed gardens. Horizontally, two CNC prefabricated laminated wood beams measuring 25 meters in length and 60 centimeters in height are placed atop this perimeter. Transversely, 32 CNC prefabricated beams, each 10 meters long and 30 centimeters high with chamfered ends, are installed.

The interaction between these two structures and technologies (masonry and wood) creates a continuous high window that runs throughout the house. This window provides even ambient natural light to all spaces, while offering a singular, uninterrupted view of the sky.

The metallic gutters have a deliberate and exaggerated presence in the house, continuously shedding drizzle due to the region’s climate.

Facing the street, the house features a formal operation inspired by Kazuo Shinohara’s House under High Voltage Lines, where a boolean subtract operation generates a form that expresses the confrontation between the private interior space and the shapes imposed by the development. This gesture nods to the architectural landscape that the project leaves behind.

O projecto localiza-se na costa chilena, entre o campo e o Oceano Pacífico, num clima mediterrânico. Neste contexto, as tecnologias construtivas tradicionais envolvem geralmente alvenaria em tijolo de barro e treliças de madeira.

A casa situa-se nos limites de um empreendimento habitacional privado ao longo da costa. Uma série de regulamentos uniformizadores, sem grande correspondência com a paisagem, é imposta por um regulamento arquitectónico. Entre estas regras, encontra-se a exigência de que todos os edifícios sejam brancos.

Devido à sua posição na periferia do loteamento, a casa tem a oportunidade de se desligar da paisagem arquitectónica do bairro, focando-se antes nas paisagens cultural, natural e climática da região.

A casa é encerrada por um perímetro de alvenaria artesanal e lenta, com

densidades variáveis, que cria tanto compartimentos interiores como jardins murados. Na horizontal, duas vigas de madeira laminada prefabricadas por CNC, com 25 metros de comprimento e 60 centímetros de altura, são colocadas sobre este perímetro. Na transversal, instalam-se 32 vigas prefabricadas por CNC, cada uma com 10 metros de comprimento e 30 centímetros de altura, com extremidades chanfradas.

A interacção entre estas duas estruturas e tecnologias (alvenaria e madeira) gera uma janela contínua em altura que percorre toda a casa. Esta abertura fornece luz natural ambiente uniforme a todos os espaços, enquanto oferece uma vista singular e ininterrupta do céu.

As caleiras metálicas possuem uma presença deliberada e exagerada na casa, vertendo constantemente a garoa, em resposta ao clima característico da região.

Voltada para a rua, a casa apresenta uma operação formal inspirada na House under High Voltage Lines, de Kazuo Shinohara, onde uma operação booleana de subtracção gera uma forma que expressa o confronto entre o espaço interior privado e as formas impostas pelo empreendimento. Este gesto constitui uma referência à paisagem arquitectónica que o projecto opta por deixar para trás.

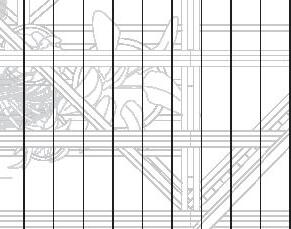

30.

50 mm of white decomposed granite (maicillo blanco)

33. Exterior garden landscaping:

Layer of compost and humus (proportion to be defined)

8 × Quillaja saponaria

8 × Cryptocarya alba

1 × Acacia melanoxylon

12 × Maytenus boaria

4 × Schinopsis spp.

24 × Searsia crenata

20 × Santolina spp.

12 × Jacobaea maritima

12 × Salvia rosmarinus

12 × Salvia rosmarinus ‘Toscany’

3 × Olea europaea

4 × Leucadendron ‘Safari Sunset’

12 × Myrceugenia spp.

1 × Aloysia citrodora

1 × Citrus limon

1 × Vaccinium corymbosum

18 × Westringia fruticosa

8 × Echium spp.

10 × Libertia chilensis

10 × Dietes spp.

20 × Gaura lindheimeri

8 × Gaura lindheimeri (pink variety)

20 × Rosmarinus officinalis ‘Prostratus’

8 × Chamelaucium spp. (interpreted from “Coloenemas”)

10 × Salvia canariensis

8 × Paspalum spp.

6 × Ceratophyllum demersum

10 × Pennisetum advena ‘Rubrum’ (Pennisetum ruppelianum)

Cachagua, Chile

The house is located in the historic part of a classic seaside town on Chile’s central coast. Its history is intrinsically linked to a construction technology, scale, and density that form part of the cultural landscape. Small houses with steeply pitched roofs, coirón coverings, and colihue ceilings are a distinctive feature of this landscape, shaped by both tradition and the demands of the coastal climate.

Facing the sea and the south, the house stands at the meeting point between a humid coastal forest and the Pacific Ocean. In Chile, a south-facing orientation means shade — anything placed in front of a structure will cast a shadow, influencing both the microclimate and the perception of space. This condition, along with the exposure to ocean winds and humidity, defines the architectural strategies employed in the project.

The house is fragmented, positioned perpendicular to the sea, and distributed around a central courtyard open to the ocean. This configuration responds to the site’s density, allowing for a more porous integration into the surroundings while optimizing natural light exposure. The courtyard acts as a thermal buffer, a place of shelter, and a space that strengthens the relationship between interior and exterior.

The ground floor, made of white concrete and galvanized steel pillars, consists of continuous slabs with separate volumes, dispersed across the terrain to generate an internal landscape.

This fragmented footprint allows the house to adapt to the natural topography while

creating pockets of light and shadow. Above this, three roof structures made of CNC-milled lenga wood artesanal laminated beams rise, featuring colihue ceilings and coirón roofs — both traditional landscape technologies used for thermal control, insulation, and waterproofing. Updated and refined, these elements open new technical and formal possibilities through subtle double curvatures that only an organic material can achieve.

A casa está situada na zona histórica de uma clássica vila costeira na costa central do Chile. A sua história está intrinsecamente ligada a uma tecnologia construtiva, a uma escala e a uma densidade que fazem parte da paisagem cultural. Casas pequenas, com telhados inclinados, coberturas de coirón e tectos de colihue, são uma característica distintiva dessa paisagem, moldada tanto pela tradição como pelas exigências do clima costeiro.

Voltada para o mar e para sul, a casa localiza-se no ponto de encontro entre uma floresta costeira húmida e o Oceano Pacífico. No Chile, uma orientação a sul significa sombra — qualquer elemento colocado à frente de uma estrutura projectará sombra, influenciando tanto o microclima como a percepção espacial. Esta condição, juntamente com a exposição aos ventos oceânicos e à humidade, define as estratégias arquitectónicas adoptadas no projecto.

A casa encontra-se fragmentada, posicionada perpendicularmente ao mar, e distribuída em torno de um pátio central aberto para o oceano. Esta configuração

responde à densidade do terreno, permitindo uma integração mais porosa com o entorno, enquanto optimiza a exposição à luz natural. O pátio funciona como tampão térmico, como espaço de abrigo, e como elemento que reforça a relação entre interior e exterior.

O piso térreo, em betão branco e pilares de aço galvanizado, é composto por lajes contínuas com volumes separados, dispersos pelo terreno de forma a gerar uma paisagem interna.

Este traçado fragmentado permite à casa adaptar-se à topografia natural, criando bolsas de luz e sombra. Sobre esta base, erguem-se três estruturas de cobertura em vigas de madeira de lenga laminadas artesanalmente e fresadas por CNC, com tectos em colihue e coberturas em coirón — tecnologias tradicionais da paisagem utilizadas para controlo térmico, isolamento e impermeabilização. Actualizados e refinados, estes elementos abrem novas possibilidades técnicas e formais através de subtis curvaturas duplas que só um material orgânico é capaz de alcançar.

Santiago, Chile

Concrete is poured and molded into its formwork; wood is joined together. Both tasks are done by a carpenter. In the end, it’s the same and opposing technology.

The house is located on the outskirts of Santiago, in the foothills of the Cordillera de los Andes, within a gated community where each home follows its own logic — houses set apart from the property lines, surrounded by gardens. This house seeks to reverse that condition. A 26-meter-long triangular beam supports the front roof, spanning from boundary to boundary, transforming the idea of a “house with a garden” into a “house with a patio.”

On the ground floor, the house is semi-buried, disconnecting from its immediate surroundings. At the back, an intimate patio shelters everyday life. At the front, in contrast, a large 15-by-5-meter open-plan room extends into the main patio.

On the second floor, the house rotates 30° to align with true north (the optimal orientation in the Southern Hemisphere). This shift generates a series of displacements that, like a vortex, are captured by an inclined wall over the entrance patio. At this point, the wall and the skylight open a clean void to the open sky, guiding natural light and its colors into the heart of the house. The open skylight, repeated in other projects, insists on the virtue of contemplating the sky from a domestic interior.

The concrete wall incorporates formwork sleeves, allowing methacrylate

tubes to channel daylight into the interior, while at night, the process reverses, illuminating the street.

In the bedrooms, a folding lenga wood lattice performs the same function: regulating light and temperature inside, while outside, it acts as a glowing lantern.

O betão é vertido e moldado na sua cofragem; a madeira é unida. Ambas as tarefas são executadas por um carpinteiro. No fim, trata-se da mesma tecnologia — simultaneamente idêntica e oposta.

A casa localiza-se nos arredores de Santiago, nas encostas da Cordilheira dos Andes, dentro de um loteamento fechado onde cada habitação segue a sua própria lógica — casas afastadas dos limites do terreno, rodeadas por jardins. Esta casa procura inverter essa condição. Uma viga triangular com 26 metros de comprimento sustenta a cobertura frontal, vencendo o vão de um limite ao outro, e transforma a ideia de “casa com jardim” numa casa com pátio”.

No piso térreo, a casa está semi-enterrada, desligando-se do seu entorno imediato. Nas traseiras, um pátio íntimo acolhe a vida quotidiana. Na frente, em contraste, um amplo espaço de 15 por 5 metros em open plan estende-se até ao pátio principal.

No segundo piso, a casa roda 30° para se alinhar com o norte verdadeiro (a orientação ideal no hemisfério sul). Este desvio gera uma série

de deslocações que, como um vórtice, são captadas por uma parede inclinada sobre o pátio de entrada. Nesse ponto, a parede e a clarabóia abrem um vazio limpo em direcção ao céu aberto, conduzindo a luz natural e as suas cores até ao coração da casa. A clarabóia aberta, repetida noutros projectos, insiste na virtude de contemplar o céu a partir de um interior doméstico.

A parede em betão incorpora mangas de cofragem que permitem a colocação de tubos de metacrilato, os quais canalizam luz diurna para o interior e, à noite, invertem o processo, iluminando a rua.

Nos quartos, uma grelha dobrável em madeira de lenga cumpre a mesma função: regula a luz e a temperatura no interior, e no exterior actua como uma lanterna luminosa.

Zapallar, Chile

The house sits on an elevated hillside with a panoramic view toward a nearly excessive western horizon, fully open to the Pacific Ocean. 2 km from Casa Engawa, it shares the same climate but is positioned higher and more exposed. The terrain has a uniform southward slope, an unfavorable orientation in the southern hemisphere.

The project counterbalances this openness through protected, domestic patios, creating intimate spaces in contrast to the vast sea. Three concrete walls reshape and reorient the topography. The first two form an inclined garden-patio, making the terrain physically present. Its slope demands effort and speed, reinforcing connection with the landscape.

Its inclination amplifies the garden’s perception from the interior, as if viewed from above. The third retaining wall, parallel to the ocean, acts as a structural pivot for the metal framework. Beneath it, a garden sheltered from sun and wind balances light and shade.

A lightweight metal structure rests on the third wall, supporting a continuous vaulted roof parallel to the ocean, defining the interior and distributing zenithal light. At its center, an inclined garden with glass facing east enhances the perception of the nearby landscape, while to the west, the view fully opens to the infinite Pacific horizon.

Here, where the house is fully exposed to intense afternoon sun, a layered system moderates light and temperature. A galvanized grating eave reflects,

filters, and softens sunlight. An interior linen curtain tempers the landscape. An exterior UV-protected acrylic curtain, inclined and automated, regulates solar exposure, reducing glare and improving aerodynamics.

This performative western facade lets the house moderate its relationship with landscape and light year-round, not imposing upon the site but interacting with it instead.

A casa implanta-se numa encosta elevada, com vista panorâmica sobre um horizonte poente quase excessivo, totalmente aberto ao Oceano Pacífico.

A apenas 2 km da Engawa House, partilha o mesmo clima, embora se situe a uma cota mais alta e mais exposta. O terreno apresenta uma pendente uniforme voltada a sul — uma orientação desfavorável no hemisfério sul.

O projecto contrapõe esta abertura com pátios domésticos protegidos, gerando espaços íntimos em contraste com a vastidão do mar. Três muros de betão redesenham e reorientam a topografia. Os dois primeiros definem um pátio-jardim inclinado, tornando o terreno fisicamente presente. A sua inclinação exige esforço e velocidade, reforçando a ligação com a paisagem.

Esta inclinação amplifica a percepção do jardim a partir do interior, como se visto em escorço. O terceiro muro de contenção, paralelo ao mar, funciona como ponto estrutural de apoio para a estrutura metálica. Sob este, um jardim abrigado do sol e do vento equilibra luz e sombra.

Uma estrutura metálica leve assenta sobre o terceiro muro, sustentando uma cobertura contínua em abóbada, paralela ao oceano, que define o espaço interior e distribui luz zenital. No centro, um jardim inclinado com envidraçado voltado a nascente intensifica a relação com a paisagem próxima, enquanto a poente o olhar se abre plenamente ao horizonte infinito do Pacífico.

Neste ponto — o mais exposto ao sol intenso da tarde — um sistema em camadas modula luz e temperatura. Uma pala em grelha galvanizada reflecte, filtra e suaviza a luz solar. Uma cortina interior de linho ameniza a leitura da paisagem. Uma cortina exterior de acrílico, inclinada, automatizada e com protecção UV, regula a exposição solar, reduzindo o encandeamento e melhorando a aerodinâmica.

Esta fachada poente, de carácter performativo, permite à casa modular continuamente a sua relação com a luz e a paisagem ao longo do ano — não se impondo ao sítio, mas antes dialogando com ele.

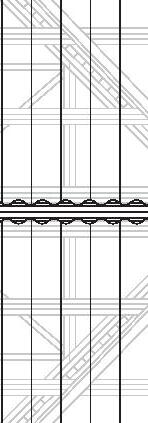

04. C-section steel profile 100x50x3 mm

05. Attic crossbeam in pinewood, 2”x4”

07. 11mm OSB, glued and stapled, with Tyvek condensation barrier

12. Galvanised grating ARS 3

13. VM4 beam, sized per structural calculations, painted per coating protocol and RAL 9002

14. PM1 column, sized per structural calculations, painted per coating protocol and RAL 9002

15. 11mm OSB, glued and stapled

16. Vertical butt-jointed eucalyptus cladding, 19mm

5”, Topwood finish with Cutek + Blondetone 4x EU, aligned with curve direction

17. 142x50x3 mm flat steel bar, painted with Creizet, colour to be defined

18. Rough sawn, impregnated pinewood, 1”x2”

19. Pinewood 1”x2” beneath bituminous membrane

20. Elastomeric bituminous waterproofing membrane, Syntoflex P4 Imper

21. Air cavity for water runoff drainage

22. 11mm OSB

23. Exposed concrete wall, 1”x8” sawn board finish

24. Floor-mounted convector, 30x200 mm, ANWO

25. Rolux outdoor screen blind

26. Window with reinforced matte aluminium frame, Superba33 model

27. 10mm marble flooring + 10mm adhesive layer

28. 50mm concrete topping (screed)

29. 18mm plywood

30. 18mm plywood painted in dark finish

31. Bracing system / structural bracing

32. Retaining wall in exposed concrete, 1”x8” sawn board finish

33. Large boulders for sub-drainage protection

34. Bench in polished concrete

35. Beach shell aggregate paving

Ilihue - Lago Ranco, Chile

HOUSE A IN A SLOPE is located in a forest clearing on a steep slope facing Lake Ranco, in southern Chile. The project draws from the archetype of the “A-frame” cabin, with two fully glazed facades that open the house to the nearby forest to the south and to Lake Ranco with the distant Choshuenco volcano to the north. To preserve the presence of the slope, the interior space adapts entirely to it. The result is a central stairway of seemingly disproportionate scale that transcends its practical role to become a flexible, playful, almost topographic space — an echo of Paul Virilio’s “oblique function.”

As Virilio wrote, “obliquity speaks of instability, links spaces dynamically, and forces the user to rethink things, to re-inhabit the space, to live on the edge… and to tread carefully.”

Above this inclined interior, a large rhombus-shaped skylight opens at the ridge, letting in the color of the sky and the forest’s shifting light and shadows.

Detached from the main volume, a cylindrical structure contains the wet areas. Here, all services and bathrooms are concentrated, also open to the sky, forming a compact, elemental core. The entire structure, made of laminated pine, was prefabricated with CNC machining 280 km from the site and assembled in just two weeks. The exterior, however, was not fast: it was fully handcrafted on site with shingles of Alerce (Fitzroya cupressoides). This technique — tejueleo — has shaped the technological and cultural landscape of southern Chile since the 17th century. Originating during the early exploitation of Alerce forests

in regions like Chiloé, Puerto Montt, Osorno, and Valdivia, tejueleo became a hallmark of rural architecture — resilient, functional, and deeply tied to place.

Today, with Alerce a protected species, its legacy survives through an Indigenous community deep in the forests near Bahía Mansa, which, through conservation agreements, works only with trees that have fallen naturally within protected areas — sustaining a craft that speaks of ecology, technology, and performance.

A House a in a Slope está localizada numa clareira florestal sobre uma encosta íngreme voltada para o Lago Ranco, no sul do Chile. O projecto parte do arquétipo da cabana “A-frame”, com duas fachadas totalmente envidraçadas que abrem a casa para a floresta próxima a sul e para o Lago Ranco e o longínquo vulcão Choshuenco a norte. Para preservar a presença da inclinação, o espaço interior adapta-se integralmente a ela. O resultado é uma escada central de escala aparentemente desproporcionada, que transcende a sua função prática para se tornar num espaço flexível, lúdico, quase topográfico — um eco da “função oblíqua” de Paul Virilio.

Como escreveu Virilio, “a obliquidade fala de instabilidade, liga os espaços de forma dinâmica e obriga o utilizador a repensar, a re-habitar o espaço, a viver na borda… e a caminhar com cuidado.”

Sobre este interior inclinado, uma grande clarabóia em forma de losango abre-se no cume, deixando entrar a cor do céu e a luz e sombras mutáveis da floresta.