HONEST ARCHITECTURE

A few years ago, it was still common to hear architecture referred to as honest.

An adjective that has gradually faded into obscurity, overshadowed by the transformations we have witnessed in the manipulation of image, transformations which the advent of new technologies has amplified to an unprecedented degree, enabling modes of expression and dissemination that are still difficult to quantify. One of the most evident consequences of this shift is the emergence of what we might call authorial architecture.

At the same time, it is well known that the vast majority of architectural projects and built works are, in fact, small in scale and receive little public attention. This everyday architecture demands a heightened sensitivity, in responding appropriately to context, in resolving programmes with rigour, and in the way architectural intentions are ultimately expressed. More than the exceptional works, it is often these modest interventions that assume a pedagogical role in affirming the relevance of architecture in our collective lives.

This is not a commentary on Coderch’s text¹, but rather an observation of how much we are lacking that today.

It is within this category that the architecture of ATELIERDACOSTA should be situated, one of the many small practices that have emerged across the country in recent years.

These are practices that persist despite uninspiring commissions and limited opportunities, operating under constraints of time and resources. And yet, they manage to uphold a fundamental quality that is essential to all architecture: the capability to be honest.

Há alguns anos ainda, eram frequentes as referências à arquitectura como honesta.

Uma adjectivação que foi ficando esquecida perante todas as transformações a que fomos assistindo na manipulação da imagem, a que as novas possibilidades vieram dar uma expressão e divulgação ainda incalculáveis. Uma dimensão de que a arquitectura que podemos chamar de autor é uma das consequências mais óbvias.

Paralelamente sabemos que a maior parte dos projectos e das obras que se fazem, são, na sua maior parte de pequena dimensão, e sem grande visibilidade. Toda una arquitectura corrente que, até por isso, exige uma sensibilidade atenta na adequação aos sítios, na correcta resolução dos programas, e no modo como tudo se exprime. Mais ainda do que as obras de excepção, estas são as que assumem um papel pedagógico para o reconhecimento da importância da arquitectura na vida de todos nós.

Esta não é qualquer reflexão sobre o conhecido texto de Coderch1, mas apenas a constatação da falta que essas obras nos fazem.

É neste grupo que devemos incluir a arquitectura feita pelo Atelier da Costa, um dos pequenos gabinetes que nos últimos anos têm proliferado pelo país.

Gabinetes que persistem, perante oportunidades de trabalho e programas quase sempre pouco estimulantes, em situações onde escasseiam os meios e o tempo, mas que, ainda assim, conseguem manter uma qualidade essencial a toda a arquitectura: ser honesta.

Nuno Melo Sousa (1988) lives and works in Penafiel, northern Portugal, since 2012.

He draws and sometimes paints too, but he mostly draws: on walls, on papers and on tables as the slowness of the act of building leaves him yearning for the immediate. Some of these drawings have been exhibited around Europe - most recently at Premio Lissone 2024.

Nuno has taught at INDA - Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand, at the Accademia di Architettura di Mendrisio, Switzerland and is currently teaching Projecto IV at the Porto School of Architecture - FAUP.

He has led workshops like Porto Academy 2021, UdGirona International Workshop 2025, and has lectured at several universities and venues.

Nuno and Hugo Ferreira won the 2023 BigMat International Architecture Award for small scale with casa no Tâmega.

Writing and playing music is a therapy and Nuno plays drums and synth with Muay, a non-stop feeling of relentless sleeping-bag tours and half-empty shows.

Nuno likes to sit alone at the building site and prefers to draw on-site rather than in CAD.

UNTITLED

I enjoy talking with Hugo about everyday things—about site discussions and how issues get resolved there, about clients who are more or less radical, about unfinished works, about interests, stubbornness, and obstinacy (both urgent and necessary).

What he draws follows a path of memory — reaching back to the classics — and I would not dare engage him in discussions about what the masters, some more anonymous than others, said or did, nor even name authors or their works. I simply understand, in what he thinks and builds, that classical coordinates and ideals are transfigured into the new things he creates: between galleries, porticos, colonnades, cornerstones, pediments, shafts, plinths, terminations…

And I take great interest in the drawing of the flashing detail, in stereotomy, in the transitions between materials. All with a balance of obsessive care and an understanding that we can only draw as far as we are allowed. These days, more and more, it seems best to draw directly on site. Because on white sheets, with title blocks, legends, hatches, and lines neatly contained, the cost of building goes up.

I feel an affinity with Hugo in the shared awareness that the backstage of drawing and construction is made of many lives, and unfolds across many places: in the theatre, in cinema, at concerts, in the garden — and, of course, around the table, eating and having good conversations.

Gosto de conversar com o Hugo sobre as coisas do dia-a-dia — do fazer: das discussões em obra e do que por lá se resolve, de clientes mais ou menos radicais, de obras inacabadas, de intenções, teimosias e da obstinação (urgente e necessária).

O que desenha segue pelo caminho da memória, indo lá atrás - aos clássicos -, e eu não me atrevo a falar com ele sobre o que os mestres, uns mais anónimos que outros, disseram e faziam, ou sequer nomear autores e respectivas obras! Apenas compreendo - no que pensa e constrói - que coordenadas e ideais clássicos se transfiguram neste novo que ele faz: entre galerias, pórticos, colunatas, cunhais, frontões, fustes, embasamentos, remates…

E anima-me o desenho do rufo, da estereotomia, das transições entre materiais, com tanto de obsessivo como de permeável à compreensão de que apenas conseguimos desenhar até onde nos deixam, e que nos dias que correm, melhor mesmo é desenhar em obra. Porque em folhas brancas, com rótulo, legendas, tramas e linhas dentro, o custo da obra aumenta.

Nutro uma afinidade pelo Hugo na consciência de que os bastidores do desenho e da construção são feitos de várias vidas e desenrolam-se em vários lugares: no teatro, no cinema, no concerto, no jardim e claro, à mesa a comer e a conversar bem.

STUDIO

Póvoa de Varzim, Portugal

The studio spans two floors: the ground floor and the basement. We worked on the ground floor and held meetings with clients and internally in the basement. As work takes up most of our time, we required a more comfortable environment, initially with more light and less privacy. There was limited freedom for the workspace to also be a creative space. However, opening a ‘crater’ in the floor slab allowed us to have more privacy and still have more light than in the windowless basement. Much has changed since then. As a founding act of our work — this work that shapes the work itself — it enabled us to link the ideas of disorder and creation. Messing up the basement without anyone noticing has become a metaphor for our ability to disrupt the established order of each project. This requires the intimacy that is finally found in subverting an established convention for workspaces.

Opening up the crater at a time when everything was being laid down, including the prosaic descriptions of the materials, made us appreciate those containing the verb more, such as ‘deactivated concrete’, ‘smoothed concrete’ and ‘polished granite’, because they declare themselves to be transformed by an action. Here, the material is concrete broken up with a jackhammer (2.1 m³). Breaking it up over several days was a foundational tectonic act. Touching the hot, tense iron of the slab, hearing the noise it made when cut and seeing the more or less well-crafted pipes crossing the filling – all of that was the work, the only truth of the project, which is a kind of fiction. This archaeological

notion of work as the ultimate truth, the only truth that matters, associated with destruction that is, in essence, construction, forced us to reconsider everything. The force of the material we built with was that of light, with its intensity and colour, and air, with its temperature and movement. This was the real lesson because apart from this, we only did what was strictly necessary: a metal frame to support the fungiform slab; a metal guard; and a plaster layer corresponding to the height of the filling.

O atelier tem dois pisos: o térreo e a cave. Trabalhávamos no térreo e reuníamos, entre nós e com clientes, na cave. Trabalhar ocupa a maior parte do tempo e, portanto, exigia maior conforto - à partida: mais luz, mas menos intimidade. A liberdade para que o espaço de trabalho fosse também de criação estava condicionada. Abrir uma “cratera” na laje era o que permitia optar por menos luz - ainda assim mais do que na cave não fenestradae por mais intimidade. Muito mudou desde então. Como acto fundador do nosso trabalho - este trabalho que molda o próprio trabalho - permitiu ligar os conceitos de desarrumação e criação. Desarrumar a cave sem que ninguém note é, agora, metáfora para o poder de desarrumar as coisas que encontramos em cada projecto e arrumá-las numa ordem diferente. É algo que exige a intimidade finalmente encontrada na subversão de uma convenção estabelecida para os espaços de trabalho.

Abrir a cratera num momento em que tudo era fundado - inclusive os prosaicos descritivos dos materiais - fez-nos gostar mais daqueles que contém o verbo: betão desactivado, betão afagado, granito polido, etc, porque é matéria que se declara transformada por uma acção sobre ela. Aqui, seria betão partido a martelo pneumático, 2,1 m3. Parti-lo (literalmente e durante demasiados dias) constituiu um acto tectónico fundacional. Tocar no ferro da laje quente e em tensão, ouvir o barulho que fez ao ser cortado, ver as tubagens que cruzavam o enchimento, mais ou menos bem amanhadas - tudo aquilo era a obra: a única verdade dessa ficção que é o projecto. Essa imagem arqueológica - da obra enquanto verdade última, a única que realmente importaassociada a uma destruição que é, afinal, construção, obrigava a rever e inverter tudo: a força da matéria que realmente construímos era a da luz - com a sua intensidade e cor -, do ar - com a sua temperatura e movimento. Essa foi a lição real, porque, de resto, apenas cumprimos com o estritamente necessário: uma armação em perfis metálicos para suporte da laje fungiforme, uma guarda metálica e um plano de reboco correspondente à altura do enchimento.

CARMO BUILDING

Porto, Portugal

When we first visited the building, there was no building left. Only the front façade, with its three storeys, which was mandatory to preserve. It was possible, however, to add another floor and an attic beneath the roof void. The programme called for three residential units and a commercial space on the ground floor.

Despite the extreme narrowness of the plot, it had two entrances, which allowed for a rethinking of the circulation system, designed entirely through the exterior, as a kind of ambulatory of stairs wrapping around the shared courtyard of the rear yard (logradouro). The concrete lift shaft would come to structure the new rear elevation, being the only volume that projects beyond the dominant façade line along Viela dos Poços. Its footprint is a softened pentagon, with two curved sides, interior and exterior, which demanded a more delicate formal resolution. Given the fragmentation of platforms at different levels and their articulation with the staircases placed in the courtyard, the intention was not to construct a conventional rear façade. Thus, the lift projection is stitched together only by iron and glass panels, forming a glazed atrium or veranda. A transitional space that leads to the interior of each unit. This same logic was extended to the exterior staircases, which rest lightly against the existing party wall, further reinforcing the complete deconstruction of any strong rear plane or volumetric reference to the original building.

The project research also focused on another complex aspect: how to allow a new floor and roof to emerge within a dense urban block, one largely untouched by recent vertical extensions

and marked by a strong metric and volumetric unity, defined by the repetition of stone cornices and window openings. We proposed a new floating façade in enamelled wood, visually detached from the original façade by means of a slender metal balcony that rests atop the existing stone cornice. Internally, with no vertical circulation cores within the units, the layout was conceived with maximum simplicity. The only spatial determination comes from the central placement of the service core, bathroom and kitchen, generating two nearly equivalent living spaces on either side.

Quando visitamos pela primeira vez o prédio, já não havia prédio - apenas a fachada frontal com 3 pisos, que seria obrigatório manter. Era possível ter mais um piso e um sótão no desvão da cobertura. Pretendia-se instalar 3 fogos e um comércio no Rés do Chão.

Apesar de extremamente estreito, o lote tinha duas entradas o que permitiu repensar o sistema de acessos, feito exclusivamente pelo exterior, como um “deambulatório” de escadas em redor do pátio comum do logradouro. O elevador em betão havia de estruturar o novo tardoz, sendo ele o único volume que se projecta além do alinhamento dominante de fachadas da Viela dos Poços, com recurso a uma planta pentagonal suavizada com curvas em dois dos seus lados - interior e exterior - que exigiam um remate mais delicado. Dada a fragmentação de plataformas a diferentes cotas e a sua articulação com as escadas implantadas

no logradouro, não se pretendia construir uma fachada de tardoz formal. Por isso, a projecção do elevador é cosida apenas com painéis de ferro e vidro que formam um átrio/ marquise, espaço de transição para o interior de cada fogo. O prolongamento desse tipo de construção metálica às escadas exteriores, simplesmente apoiadas na antiga parede meeira, reforçam essa desmontagem absoluta de um plano marcado ou referência volumétrica do edifício original.

A pesquisa do projecto concentrou-se ainda noutro aspecto difícil: a maneira de fazer emergir um novo piso e a sua cobertura, num quarteirão bastante compacto e sem novas ampliações recentes, com uma grande unidade métrica e volumétrica, dada pela repetição de cantarias e janelas. Fizemos flutuar uma nova frente em madeira esmaltada, desligada da fachada antiga pela presença de uma varanda metálica que encima a cornija de pedra. Os interiores, livres de qualquer acesso vertical, queriam-se com a maior elementaridade possível, em que a única determinação espacial é a posição das infraestruturas - casa de banho e cozinha - ao centro, gerando dois espaços praticamente equivalentes.

BOUTIQUE AND BARBERSHOP

Viana do Castelo, Portugal

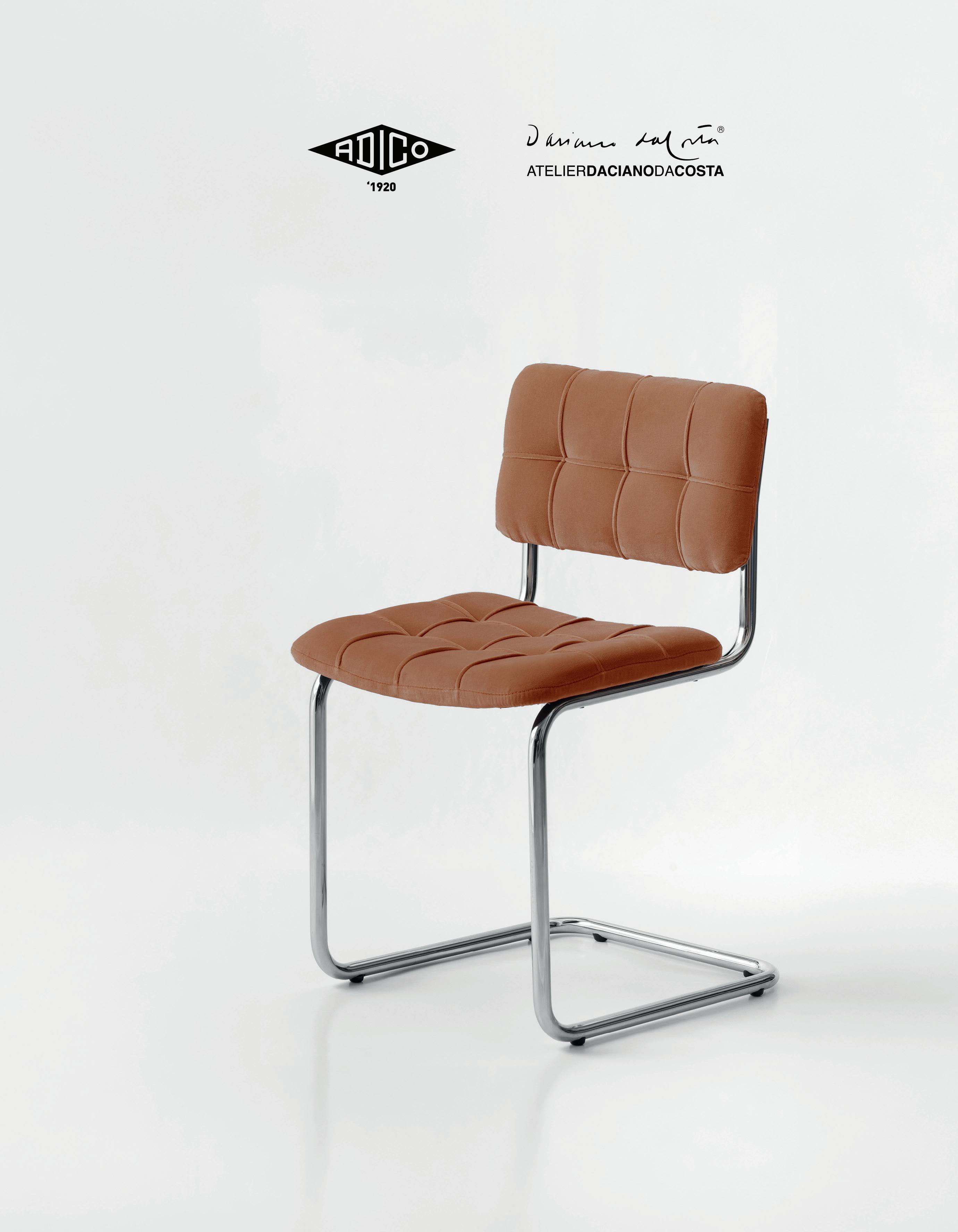

Faced with the client’s brief and the visit to the corner site in the historic centre of Viana do Castelo, the hypothesis emerged that the programme could be resolved by designing only a kind of single device, a wooden and metal cabinet as a container placed within the space.

The client’s central idea was the reconciliation of the functions of barbershop and boutique, demarcated yet not segregated, including fitting rooms, display units, a small storage area, counter—all of them subspaces or niches. This led us to retain the masonry as found (essentially the bathroom) and to adapt the aforementioned device, even while adhering to a highly recognisable structural grid, facilitating its construction in wood and metal.

This piece, placed at the core of the shop, frees the perimeter of the façade and shapes the space between them. Thus, the device had to be designed as if resting upon continuous floor (in marmorite) and ceiling (painted blue). The piece may be divided into three parts, from the heaviest to the lightest: the wooden structure, creating the primary and regular support; the semi-open metallic mesh with irregular, curvilinear contours, accommodating the clothing storage and technical space with the stainless steel HVAC ducts, which project beyond its limits and invade the “exterior” space. The piece is, therefore, the “machine” that concentrates productivity and serves the empty space it defines and in which consumption takes place. Establishing a relation with the surrounding public realm, a street and a square, the heavy external shell of stone and windows functions as an informal

shopfront, punctuated with new red awnings and large industrial bell lamps.

The second layer, defined by the designed device, is perceived from the outside as an interior within an interior, a collection of niches for display, and the lighting is warmer and more golden than that of the façade perimeter. Between the two “shells” one wanders through a “threshold” space, between white and gold; stone and wood; inside and outside; public and private.

Perante a descrição do pedido do cliente e a visita ao espaço de gaveto no centro histórico de Viana do Castelo, emergiu a hipótese do programa poder ser resolvido projectando apenas uma espécie de dispositivo único, um armário de madeira e metal como contentor colocado no espaço.

A ideia central do cliente era a conciliação das funções de barbearia e de boutique, demarcadas, mas não segregadas, contemplando provadores, expositores, um pequeno armazém, balcão, todos eles subespaços ou nichos. Isso levou-nos a manter a alvenaria como encontrada (essencialmente a casa de banho) e a ajustar o referido dispositivo, mesmo que obedecendo a uma malha estrutural muito reconhecível, auxiliando a sua construção em madeira e metal.

Esta peça, colocada no núcleo da loja, liberta o perímetro da fachada e molda o espaço entre ambas. Portanto, o dispositivo deveria ser projectado como se pousasse num piso (em marmorite) e tecto (pintado a azul) contínuos.

A peça pode ser dividida em 3 partes, da mais pesada à mais leve: a estrutura em madeira, criando o suporte principal e regular, a malha metálica semi-aberta com contornos irregulares e curvilíneos para albergar o armazém de roupas e o espaço técnico com e a tubulação de AVAC em aço inox, que se projecta para fora dos seus limites e invade o espaço “exterior”. A peça é, portanto, a “máquina” que concentra a produtividade e serve o espaço vazio que define e onde o consumo se manifesta. Estabelecendo a relação com o espaço público ao redor, uma rua e uma praça, a pesada casca externa de pedra e janelas funciona como montra informal, pontuada com novos toldos vermelhos e grandes campânulas industriais.

A segunda camada, definida pelo dispositivo projectado, é percebida do exterior como um interior dentro de um interior, uma colecção de nichos para exposição, e a iluminação é mais quente e dourada que a do perímetro de fachada. Entre as duas “cascas”, deambula-se no espaço “limiar”, entre branco e dourado; pedra e madeira; dentro e fora; público e privado.

HOLIDAY HOME

Gemeses - Esposende, Portugal

The brief was clear: the house could be ephemeral, built entirely in timber. Coincidentally, that same year I visited the wooden churches of Maramures, a constructions over 300 years old. This house, however, was not expected to last more than 20 or 30 years; it was to be designed in response to a specific phase of life, a child’s, and to accommodate the gatherings of an extended family. In counterpoint to those expansive time scales, the construction needed to be extremely fast. On a teardrop-shaped triangular site, we placed a two-storey volume in order to preserve as much of the land as possible. The floor plan is a 10x10 metre square, oriented to take advantage of all quadrants of the surrounding landscape — both in terms of solar exposure and, for example, the vast expanse of forest to the north. The entire ground floor, with a solid concrete perimeter, was dedicated to social and outdoor functions. This solution was, in part, a pragmatic response to the unavailability of structural carpenters at the start of the construction.

The base and boundary walls were cast in concrete using horizontal 12cm timber formwork boards. The same direction in which the concrete was poured, from top to bottom. Above this base, only a timber volume is visible, assuring the same footprint and housing the sleeping quarters. It is clad in untreated, thermally modified vertical timber boards, also 12cm wide, left to weather naturally and blend into the landscape over time. Unlike the concrete base, the timber cladding is installed by hand from scaffolding, following the logic of a craft-based, incremental assembly.

The ground floor accommodates the kitchen, laundry, and bathroom, as well as a series of living spaces, organised around a central concrete column.

To the south, an indoor solarium opens out to an exterior terrace via a wide and sheltered threshold; to the north, a living area and dining room project outward through a bow window. The deep southern porch allows an 8-metre glass opening to remain comfortable in spite of the region’s often disruptive winds.

O pedido era claro: a casa poderia ser efémera, construída inteiramente em madeira. Coincidentemente, nesse mesmo ano, visitei as igrejas de Maramures — construções de madeira com mais de 300 anos. Esta, no entanto, não precisava de durar mais de 20 ou 30 anos, mas sim ser pensada em função de uma infância — a do filho — e para acolher o convívio de uma família mais alargada. Em contrarrelógio com esses espaçostempo, a obra teria de ser muitíssimo rápida. Neste triângulo em forma de lágrima, implantámos um volume com dois pisos para libertar o máximo de terreno. Desenhámos uma planta quadrada, de 10x10m, aproveitando todos os quadrantes da paisagem em redor, tanto pela sua orientação solar, como, por exemplo, pela maior vastidão dos bosques a perder de vista a Norte. Para o espaço social, interior e exterior, reservámos todo o piso térreo de perímetro sólido em betão, prosaicamente resolvido pela indisponibilidade de carpinteiros de estruturas para iniciar a obra.

O embasamento e os muros de vedação foram então cofrados em tabuado de madeira de 12cm, colocado na horizontal, assim como é o sentido do seu processo de construção, betonado de cima para baixo. Acima disso, espreita apenas um volume em madeira com a mesma implantação albergando os espaços de pernoite, forrado num tabuado termotratado sem qualquer verniz, esperando que a natureza misture as suas cores. Também de 12cm, é colocado na vertical, colaborando na montagem do material que, ao contrário do betão, o operário vai aplicando a percorrer o andaime. O piso térreo aloja os espaços de produção/serviço da cozinha, da lavandaria e da casa de banho, e todos os outros espaços que, através da colocação de um pilar de betão, se conseguem organizar: a sul, um solário interior prolongado em esplanada exterior, por via de um largo e protegido umbral; a norte, pelo contrário, uma zona de estadia e uma sala de jantar através da projecção de uma bow window Graças à profundidade e desenho do umbral/alpendre, a abertura de 8 metros de vidro permite ainda assim estar no interior sem o desconforto do vento que pode tornar-se perturbador.

Entre a profundidade do umbral a sul e a filigranar bow window a norte, situa-se, a nascente, a escada de acesso ao piso superior, também projectada sobre o terreno. O espaço de acesso aos quartos é um corredor que rasga o edifício e é deliberadamente sobredimensionado para servir de espaço social mais íntimo, permitindo organizar um escritório e resolver a excessiva colectivização do piso térreo.

Lunawood type

CAR PORCH

Terroso - Póvoa de Varzim, Portugal

At a service station, the aim was to reorganise an area with precarious existing canopies used for car vacuuming and other ancillary services, consolidating them under a single, double-island canopy comprising 10 bays. We proposed a structure with a V-shaped configuration, supported by a single central portal that also houses the technical infrastructure and payment facilities. Given the considerable depth of this central structural element, we introduced a linear skylight cutting through the inclined aluminium ceiling planes.

The structure appears oblique and detached, set within a void defined by the façades of adjacent service buildings clad in metal sheeting and perimeter boundary walls. We designed the metal framework to completely free the underside of the ceiling plane, relying solely on aluminium and enhancing its reflective properties. On the opposite side, particularly visible from the top of the canopy, the entire horizontal truss structure is left fully exposed. The supporting T-shaped portal frame for this truss, repeated six times, is expressed in full at each end, revealing all of its tectonic reality: gussets, bolts, reinforcements, and so on. The perimeter flashing is finished in a mirrored material so that the extremities of the canopy wings reflect the colour of the sky.

Numa estação de serviço pretendia-se reorganizar uma área com precárias coberturas para aspiração de automóveis e outros serviços, centralizando-os num único coberto em ilha dupla, com 10 boxes. Propusemos um coberto com estrutura em “V”, descarregando num único pórtico central que reúne

também as infra-estruturas e áreas de pagamento. Neste pórtico central da estrutura, dada a grande profundidade da peça, incluímos uma clarabóia linear rasgando os planos de tecto inclinado em alumínio.

A peça surge oblíqua e desagrupada no meio de um vazio formado por planos de fachadas de edifícios de apoio em chapa e muros de vedação. Desenhamos a estrutura metálica com o intuito de libertar o plano inferior de tecto, tendo somente o alumínio e potenciado o seu efeito reflexivo. Para o lado contrário, com especial visibilidade no topo do coberto, deixamos toda a estrutura de treliça horizontal. O pórtico em “T” de suporte dessa treliça, repetido 6 vezes, é revelado em cada topo pleno de toda a sua realidade tectónica: pateres, parafusos, reforços, etc. O rufo perimetral é com acabamento espelhado para que os extremos das asas já tivessem a cor do céu.

VILARINHA HOUSE

Porto, Portugal

The existing house, located on a corner lot in the Bairro da Vilarinha, had already undergone a westward extension, the same quadrant where a new expansion was now proposed. The neighbourhood, one of the last Estado Novo-era developments in Porto (1958) focused on single-family housing with small gardens for a predominantly civil servant class, consistently repeats a typological model across a significant area of new urbanisation. Throughout the development, one can observe a clear, albeit late, attempt to reproduce certain modernist public housing models, originally born out of early 20th-century German and Russian experiments.

In response, the proposed extension, which aimed to nearly double the existing built área, sought to preserve two fundamental principles: a certain elemental clarity and constructive modularity. However, it simultaneously intended to radically transform the nature of the interior spaces — in their atmosphere, materials, and relationship to sunlight and the urban surroundings. To the original volume — rendered in plaster and stone, enclosed and monolithic in character — we added a structure that is, by contrast, open and expressive of its own framework, where any surface that is not glazed is likewise reflective and visually absorbent of its context. The structural geometry of the new intervention is essentially resolved through three equidistant metal portal frames, which support both the new slabs and reinforce the existing ones. The limit of the extension aligns precisely with the central frame.

Economic rationality guided the decision to retain the original eastern body of the

house, which was merely reinforced with a metal structure, and this same logic extended into the design approach, informing a deliberate austerity in the treatment of the interior spaces. This imposed sense of elemental restraint was broken only once, following the discovery of a construction error, a misalignment that, although quickly corrected in general terms, left a visible trace: a concrete cornice overlapping the original volume. In the end, we accepted it, amused by the clear, and even welcome, disruption it introduced, as though the project itself acknowledged that a single moment of friction could become a form of resolution.

A casa existente, num gaveto do Bairro da Vilarinha, tinha já uma ampliação a poente, quadrante para onde se poderia ampliar novamente. O bairro, um dos últimos do Estado Novo no Porto apostando na habitação unifamiliar com pequeno quintal para uma classe formada maioritariamente de funcionários do Estado (1958), repete consistentemente a tipologia como modelo numa considerável área de nova urbanização. Em toda a urbanização há uma clara procura em reproduzir tardiamente alguns modelos modernos de habitação de iniciativa pública, saídos, originalmente, das experiências alemãs e russas do início de século.

Procurámos que a ampliação pedida, cujo programa apontava para uma duplicação da área existente, mantivesse dois dos seus fundamentos - uma certa elementaridade e a modularidade construtiva -, mas alterasse por completo

a natureza dos espaços propostos, na sua atmosfera, materiais e relação com o sol e envolvente urbana.

Assim, ao volume de reboco e pedra, tendencialmente encerrado e monolítico da casa original, juntamos um volume tendencialmente aberto e estrutural, onde qualquer paramento que não vidro, é igualmente reflector e miscível com o seu entorno. A geometria de implantação da estrutura é essencialmente resolvida em três pórticos metálicos equidistantes, suporte das novas lajes e reforço das antigas, cujo limite coincide com o pórtico central. A racionalidade económica fundamentou a manutenção das estruturas do corpo original a nascente, tratadas apenas com reforço metálico, e prolongou a sua influência no projecto através de uma certa austeridade com que se abordaram os espaços interiores. A imposta elementaridade do projecto só foi quebrada depois de descoberto um erro de obra que, no grosso, prontamente se corrigiu, mas de que se deixou pequeno registo (cornija de betão a sobrepor o volume antigo), vencidos pela óbvia e jocosa realidade de que um elemento de perturbação seria afinal bem-vindo.

PÓVOA RENOVATION APARTMENT

Póvoa de Varzim, Portugal

What began as a request for a basic apartment renovation, involving painting, varnishing, and minor repairs, became the opportunity for a deeper intervention in the service core, namely the bathroom (entirely redesigned), a bedroom, and the connecting corridor.

The existing sanitary fixtures were replaced and reorganised around the introduction of two new elements: a marmorite tile grid on the floor and a timber-framed cabinet or partition that broke through the original front wall of the bathroom. Rotated in relation to the previous compartmentalisation, it now faces the apartment’s largest window and stitches together two alignments of the corridor walls.

Given the material rupture these new surfaces represented, we sought continuity in the deep red tone of Takula wood, relating it to the pre-existing terracotta floor tiles. The timberwork was ambitious in its profiles and junction details, largely because we quickly realised we were working with a carpenter still versed in naval construction techniques. Drawing is a futile act if one does not know how to build.

And learning to build in order to learn how to draw is, therefore, the only path. Without this carpenter, we would have been mere programmers of space; with him, we become interpreters of his craft.

O pedido de renovação de um apartamento, com pinturas, envernizamentos e reparações, torna-se motivo para uma intervenção

mais profunda no núcleo de serviços, nomeadamente na casa de banho (totalmente nova), quarto e corredor.

As louças existentes são substituídas e reorganizadas a partir da introdução de dois novos elementos: uma grelha de ladrilhos de marmorite no piso e um caixilho/móvel de madeira que rompeu com a parede fronteira existente da casa de banho. Rodado face à compartimentação, ficou voltado para a maior área de janela do apartamento e coseu dois alinhamentos das paredes do corredor.

Face à ruptura em relação ao existente que estes revestimentos representavam, procuramos no vermelho intenso da madeira de Takula a continuidade com a tijoleira de barro pre-existente. O desenho das carpintarias foi ambicioso nos perfis de caixilharia e soluções de remate, porque cedo percebemos que estávamos perante um carpinteiro que ainda podia fazer construção naval. Desenhar é um acto vão se não se souber como construir.

E aprender a construir para aprender a desenhar é, por isso, a única via. Sem este carpinteiro seríamos meros programadores do espaço, assim somos apenas intérpretes do seu saber.

RATES HOUSE

São Pedro de Rates - Póvoa de Varzim, Portugal

The site faces the street at a lower level and opens onto an expansive cornfield at a significantly higher elevation. This difference in levels creates a strong contrast in orientation, almost two distinct worlds within the same plot. The existing house, built in schist masonry, featured a Romanesque church capital embedded in its façade, which prompted early discussions with local heritage authorities regarding its preservation, especially considering the advanced state of ruin and the intention to more than double the building’s original footprint.

Of the two pre-existing schist volumes, we occupied the one adjacent to the street with the bedrooms, while the other was deliberately “emptied” to create an exterior courtyard. The project aims to consolidate and reinforce the existing fabric, merging with its traces and alignments by building in and around a new concrete “vault”. A core that extends from the street to the secluded edge of the northern fields. This strategy of “preservation by continuation” could, despite clear differences, draw a parallel with the enduring and efficient example of the Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba. The new concrete walls and slabs are designed both to adapt to the footprint of the existing volumes and to accommodate a new organising axis, defining the entrance sequence, technical/service areas, and a covered parking space.

Between these two key conditions, imposed and self-imposed, the project seeks to create a system of four courtyards, more or less open to the surrounding landscapes:

two facing the street quadrant, and two facing the fields.

The absence of any reference to the client’s brief may seem surprising, as it is typically a central part of our process. However, in this case, the alignment between client expectations and the design proposal was almost absolute from the outset. Ironically, the main negotiations only arose at the very end, centred around one major topic: the selection and combination of ceramic finishes.

O lote confronta a rua numa cota baixa e um vastíssimo campo de milho numa cota alta. Esta diferença de alturas gera uma grande variação de quadrantes, quase dois mundos separados no mesmo terreno. A casa existente, construída em xisto, mantém um capitel da igreja românica na sua fachada, o que suscitou um debate inicial com as autoridades locais sobre a sua preservação, face ao estado de ruína total e às intenções de ampliar a casa para mais do que o dobro do seu tamanho original.

Dos dois volumes de pedra de xisto préexistentes, ocupámos aquele situado junto à rua com quartos, enquanto o outro foi “desocupado, dando lugar a um pátio exterior. A proposta visa cintar e consolidar as pré-existências, fundindo-se com os seus traçados e alinhamentos, construindo dentro e em torno de um novo “cofre” de betão, que se prolonga desde a rua até ao isolamento dos campos a norte. Esta estratégia de “preservação”, que procura conservar continuando, poderia encontrar inspiração — apesar das óbvias diferenças — no exemplo super eficiente

e duradouro da Mesquita e Catedral de Córdoba. As paredes e lajes de betão são propostas tanto para se adaptarem à implantação das casas pré-existentes, como para acomodar um novo eixo principal organizador, que define o espaço de entrada e a área técnica/serviços e alpendre dos carros.

Entre estas duas circunstâncias principais, impostas e auto-impostas, o projecto procura criar um sistema de quatro pátios, mais ou menos abertos para as paisagens exteriores - dois deles voltados para o quadrante da rua e os outros dois para os campos. A ausência de uma referência ao pedido do cliente pode surpreender, uma vez que é habitual ser um ponto central para nós.

No entanto, aqui a unanimidade entre pedido e projecto foi quase absoluta ao longo de todo o processo. Jocosamente, a principal discussão e negociação aconteceram no final, em torno de um grande tema: as combinações de cerâmica.

01. Reinforced concrete wall

02. 13x13 green glazed tiles, grouted with red cementitious mortar 03. 70mm mineral wool, 70 kg/m³ 04. Half wall with double B13 type plasterboard.

05. Kambala wood window frames, monorail sliding opening, with colourless water-based varnish finish, standard hardware and milling system. 06. Interior sliding door with pine crate structure treated with Okoumé plywood coating, colourless water-based varnish finish.

CRESPO HOUSE

Póvoa de Varzim, Portugal

We began Casa Crespo with a detailed description of the client’s vision. The social space, specifically the “living room”, was to be spacious enough to accommodate a large dining table, an extra-long sofa facing a wide-screen TV, a billiards table, and even a DJ booth for parties. It was to be open to the kitchen and benefit from a double-height ceiling, inspired by something the client had seen in a Brazilian soap opera a few weeks prior (remarkably close to Hoffmann’s Palais Stoclet, although we personally prefer his rival Loos, as in the Villa Müller).

The Egyptian Hall for Parties, as described by Palladio, became a serious reference in composing this assemblage of spaces: columns supporting the mezzanine floor above, where a continuous wall with half-columns frames the downward view and allows diffuse light to filter in, in our case, achieved through inverted skylights that reflect natural light into the room.

A kind of “anti-domesticity,” as Pier Vittorio Aureli1 puts it, ran throughout the project, a search for an architectural truth that would match the client’s desired “fiction.” Perhaps it’s an exaggeration, but the spirit of this house might well be found in American boarding houses, where communal life unfolded in an open-plan space, structured essentially by the building’s structural grid. Forming a sort of hypostyle domesticity that extends outwards, encompassing nearly every imaginable function.

Accordingly, private and strictly functional areas are relegated to a parallel sphere, clearly separating social life from private intimacy and reproductive labour.

Each of these spheres required its own scenographic logic: the upstairs bedrooms were all designed as suites (much like a real hotel), allowing for individualised theatrical expression, the pink bedroom for the daughter, the oversized window overlooking the master suite, the clinical and washable character of the kitchen/laundry, and so on.

1Andrea Palladio, The Four Books of Architecture, 1570, MIT Press, pp. 41

Começámos a Casa Crespo com uma descrição detalhada e rica da visão do cliente: o espaço social, especificamente a “sala de estar”, deveria ser suficientemente espaçosa para acomodar uma grande mesa de jantar, um sofá bem comprido à frente de uma ampla TV, uma mesa de bilhar e até uma mesa de DJ para os dias de festa. Deveria também ser aberto para a cozinha e usufruir de um duplo pédireito, tal como o cliente tinha visto numa novela brasileira semanas antes (muito semelhante ao Palais Stoclet de Hoffman, embora prefiramos o seu rival Loos na Villa Müller, por exemplo).

O Egyptian Hall for Parties *, descrito por Palladio, foi uma recomendação que levamos a sério na composição deste composto de espaços: Colunas para suporte do pavimento do varandim,sobre o qual uma parede contínua com meias colunas enquadra a vista para baixo e deixa uma luz difusa irradiar (neste caso obtida através da reflexão da luz dos lanternins colocados de forma invertida).

Uma espécie de “anti domesticidade”, como afirma Pier Vittorio Aureli1, atravessou toda a pesquisa por uma verdade arquitectónica que correspondesse a essa “ficção”. Talvez seja um exagero, mas a natureza desta habitação podia ser encontrada nas boarding houses americanas, onde a socialização da vida na área comum ocorria num plano bastante aberto, essencialmente dividido por elementos estruturais do edifício, constituindo uma espécie de domicílio hipostilo que se prolonga para o exterior, com quase todas as funções imagináveis. Posto isto, as áreas privadas e estritamente funcionais devem ser relegadas para uma esfera paralela que separe claramente a vida social da vida privada/íntima e do trabalho reprodutivo. Todos com necessidades cenográficas específicas, os quartos dos pisos superiores eram todos suítes (como num hotel real), permitindo uma performance cenográfica autónoma: o quarto corde-rosa para a menina, a grande janela com vista para o quarto principal, o carácter asséptico e lavável da cozinha/ lavandaria, etc.

1 Andrea Palladio, Os Quatro Livros de Arquitectura, 1570, MIT Press, pp. 41

ENTREPAREDES BUILDING

Porto, Portugal

In the former Imperial biscuit factory, installed within a late 19th-century bourgeois townhouse — everything coexisted: concrete slabs, metal trusses, aluminium windows, asbestos-cement roofing, industrial tiles, and, of course, remnants of the original construction — chestnut timber floor structures, a façade with early 20th-century stonework and ceramic tiles, wooden windows, lath and plaster partitions, and so on.

The factory floor plan occupied the entire plot. The early decision not to demolish everything meant accepting, and even intensifying, this inherent heterogeneity in the new intervention, which was to accommodate five housing units and one office.

The construction would be carried out by small workshops. In some cases, through partial self-build, on which we learned to relativise the role of the architect. Or more precisely: to dilute authorship into the work itself, which is also the project. Locksmith, carpenter, mason, electrician — all become in-situ authors.

To clearly define the project and demonstrate its logic to all parties involved, it became necessary to assemble three horizontal “platforms” (a new floor was permitted), functioning as full-scale printed plans. We reused the original building’s structure all the way to the rear, opening a large, ventilated lightwell at the centre. This void now organises the entire access and service core — kitchens and a metal lift that also supports the timber floors.

In the former backyard, the party walls lacked structural and material quality.

We therefore opted for a new concrete structure with composite slabs, based on a strict metric that allowed us to stitch together the key elements, including the existing stairwell. From that point on, the architectural game became one of assembling stairs, balconies, elevator shafts, niches — all aligned with a 1.2m grid that divides the building’s width into four equal parts. The goal was to allow the bourgeois house and the factory to give way to collective housing with minimal superfluous effort.

No two floor plans are exactly the same, aiming to create spatial diversity in the “exterior” common areas between units. The street-facing apartments expand vertically, with their own staircases connecting two levels. The rear-facing units expand horizontally, forming a volumetric whole that breaks down into patios, terraces, and balconies — all interconnected.

Unlike the apartments, which are sealed “boxes” and organise vertical space through stacked voids culminating in a large skylight, the office functions at ground level as an extension of the entrance atrium, terminating in a framed view of a large boulder, softly lit by diffuse light.

Na antiga fábrica de biscoitos Imperial, instalada numa casa burguesa da segunda metade do século XIX, havia de tudo: lajes de betão, treliças metálicas, janelas de alumínio, telha de fibrocimento, azulejos industriais e, claro, resquícios da construção original — a estrutura de piso em madeira de castanho, a fachada com cantarias de pedra

e azulejos de inícios do século XX, janelas de madeira, tabiques, etc.

A fábrica ocupava a totalidade do lote. Não demolir tudo — opção que tomámos desde cedo — implicava admitir que essa heterogeneidade teria de ser continuada (e até aprofundada) na nova intervenção, destinada a acolher uma habitação colectiva com cinco fogos e um escritório.

A construção seria garantida por pequenas oficinas, senão mesmo por autoconstrução, e nesse processo aprendemos a relativizar o autor. Ou melhor: a diluí-lo na obra, que é também projeto. Serralheiro, carpinteiro, pedreiro, eletricista — todos autores in situ.

Para marcar a obra e demonstrar a todos eles o seu funcionamento, foi necessário montar três tabuleiros horizontais (foi permitido acrescentar um piso), como plantas impressas à escala real. Reutilizámos a estrutura do prédio original até ao tardoz, abrindo um grande saguão ventilado ao centro, que viria a organizar todo o núcleo de acessos e cozinhas, com um elevador metálico que também serve de estrutura aos pisos de madeira.

No antigo logradouro, as paredes meeiras não tinham a mesma qualidade, pelo que optámos por uma estrutura de betão com lajes colaborantes, seguindo uma métrica que permitia coser os principais elementos, incluindo a escada existente.

A partir daí, o jogo passou a ser o de adicionar escadas, varandas, elevador, nichos, todos arrumados segundo uma métrica principal de 1,2m, que dividia o prédio em quatro partes iguais na sua largura.

QUINTA DO FREIXO

Guilhabreu - Vila do Conde, Portugal

At Quinta do Freixo, the client requested from the outset a “classical architecture” to create an event space accompanied by a small support hotel. This was not only a matter of taste, but also because the presence of a Chapel and a Manor with a cloister richly imbued with classical motifs. Continuing that architectural language could only happen with the awareness that, on one hand, that classical architecture can no longer be made as it once was, and on the other, that trying to escape it is futile: we are always repeating it, consciously or not. After many discussions with the client on the subject, we understood that this classicism was neither about treatises nor stylistic mimicry, but about the essence found in many architectures of the past. The client’s demand was simple and could be summarized as: if we can draw inspiration from Pinterest featuring buildings 5, 10, or 20 years old, why not from those 200, 300, or 1500 years old? This gesture, at once revolutionary and conservative, asserts that all architecture belongs to the past, and for him, being “classical” is far broader than a taxonomic definition. The ancestry of trilithic or arched constructions present at Quinta do Freixo, carries an indecipherable transhumance of influences: from the rudimentary to the sophisticated, from the popular to the erudite, from the Espigueiro to the Cathedral. They are all one. Guided by a shared Warburgian map and multiple intersecting archaeologies, we distilled the construction down to six essential materials: stone, wood, tile, copper, steel, and glass.

The colonnade’s metric of the cloister was used as a matrix for the entire

expansion—both in the Manor’s extension, where the hotel is located, and in the new low-level building housing the large event hall. The program is more than a list of spaces; it embodies an entire ceremonial narrative with its complex logistics and choreography—from the arrival of cars at a roundabout at the end of a long, ramada-lined path; through the chapel’s forecourt with its celebratory curved promenade; to the interior spaces where the traditional “copo d’água” unfolds.

We reinforced this great spatial fragmentation by creating resting landings on the stairs leading to the lower floor, where we fit the large nave—the climax of the whole promenade, oriented towards the great lake and forest.

Na Quinta do Freixo, o cliente pediu, desde início, uma “arquitectura clássica” para erguer um espaço de eventos com um pequeno hotel de apoio. Fê-lo por gosto - e porque, naquele conjunto, existia já uma Capela e uma Solar com um claustro plenos de motivos classicizantes. A ideia de o continuar só podia acontecer com a noção de que, por um lado, já não se pode fazer aquela arquitectura clássica e, por outro, de que fugir-lhe é vão: estamos sempre a repeti-la, com ou sem consciência. Depois de muitas conversas com o cliente sobre o tema, entendemos que esse clássico não seria o da tratadística nem o estilístico, mas o de muitas arquitecturas de outrora. A reivindicação do cliente era simples e podia resumir-se assim: se nos podemos inspirar num pinterest com edifícios de 5, 10, 20 anos, por que não ter o meu com mais 200, 300 ou 1500 anos?

Este gesto, simultaneamente revolucionário e conservador, reclama que todas as arquitecturas são do passado, e que, para ele, ser “clássico” é bem mais amplo do que uma definição taxonómica. A ancestralidade de uma construção trilítica ou em arco, ambas presentes na Quinta, carrega consigo uma indecifrável transumância de influências: do mais rudimentar ao mais sofisticado, do mais popular ao mais erudito, do Espigueiro à Sé Catedral. Todos são um só. Movidos por um mapa warburguiano partilhado e por várias arqueologias cruzadas, reduzimos a construção a seis materiais essenciais: pedra, madeira, telha, cobre, aço e vidro.

A métrica da colunata do claustro foi usada como matriz para toda a expansão - tanto na ampliação feita ao Solar, onde localizamos o hotel, como no novo edifício à cota baixa onde localizamos a maior nave para eventos. O programa é mais que uma lista de espaços, deve incorporar todo um novelo cerimonial, com toda a sua complexidade logística e coreográfica - desde o momento da chegada dos carros, numa rotunda ao fim de um longo percurso com ramada; passando pela área exterior do adro da capela, com um passeio celebratório em curva; até aos espaços interiores, onde decorre o chamado copo d’água. Reforçámos essa grande fragmentação espacial ao criar patamares de estadia nas escadas que conduzem ao piso inferior, onde encaixamos o grande volume da nave, apogeu de toda a promenade, voltado para o grande lago e o bosque.

AV. 25 ABRIL BUILDINGS

Póvoa de Varzim, Portugal

The urban plan defined a residential block composed of six 8-storey buildings arranged perpendicular to a new street, closed off on the opposite side by a continuous threestorey band. The commission included three of these blocks and half of that band. Except for sun and wind, there was little contextual or referential information in this expanding part of the city. To the west, toward the center, an old national road—still consolidating as a street—is now cut by a major thoroughfare, with buildings clearly disproportionate in scale, delimiting the blocks to the east.

The challenge was to colonize, punctuate, and densify while maintaining the openness that this area offers its inhabitants. For this, not so much due to the physical context but primarily the cultural one, objectivity was essential. A constructive eloquence rooted in Alberti’s Concinnitas. We established a Cartesian grid on horizontal and vertical planes, colonizing the entire intervention area, always subdividing into mathematical multiples to shape forms and objects.

Alberti, especially in the Palazzo Rucellai, sought to establish through the façade a new interface between rising civil power and the city. Using columns as ornament and metric, so that the volume wouldn’t become “excessive” or imposing, he shaped the relations of the triangle urbs, civitas, and polis. How could real estate—so stigmatized, partly by its own fault, amid a widespread fear of “cement”, present a new public face of solidity, far from Koolhaas’s junkspace? That was the problem of the façades. We found the answer in aligning the structure with the minimum module of an interior room, the bedroom, which, aggregated, formed living rooms, or when divided,

generated balconies. We sought a certain structural density and, in perspective, almost only columns and their entablatures are visible, conferring a potentially ornamental character. Yet ironically, given the request for unobstructed interiors with non-standard openings, this rigid façade contour proved essential. Once the scheme was set, the most fun part was programming it: an urban stepped frontage to stitch together the scales of the band and the blocks; a modern stoa crossing the blocks in the form of a pergola and dividing the public gardens created; and a series of resting platforms along those gardens. Because, after all, the grid also subverts itself.

O plano urbano definia um quarteirão de habitação composto por 6 blocos de 8 pisos, dispostos perpendicularmente a uma nova rua, fechada do lado contrário por uma banda contínua de 3 pisos. A encomenda contemplava 3 desses blocos e metade dessa banda. À excepção do sol e do vento, pouco havia de referencial ou contextual neste lugar de expansão da cidade. Para poente, em direcção ao centro, uma antiga estrada nacional ainda a consolidar-se como rua, é agora cortada por uma grande via, com edifícios claramente desproporcionais para a sua escala, que delimita os blocos a nascente.

Havia que colonizar, pontuar, densificar e, ainda assim, manter a qualidade do desafogo que esta zona proporciona aos seus habitantes. Para isso, não tanto pelo contexto físico, mas sobretudo cultural, a objectividade era um valor essencial -

uma eloquência construtiva que poderia encontrar raízes no Concinnitas de Alberti. Montamos uma grelha cartesiana nos planos horizontal e vertical, colonizadora de todo o espaço de intervenção, dividindo-se sempre em múltiplos matemáticos para moldar as suas formas e objectos.

Alberti, no Palazzo Rucellai em particular, procura estabelecer, através da fachada, um novo interface entre o novo poder civil em ascensão e a cidade. Usando colunas como ornamento e métrica, para que a volumetria não se tornasse “desmesurada” ou impositiva, molda as relações do triângulo urbs, civitas e polis. Como poderia o imobiliário - tão estigmatizado, por culpa própria, e num clima de medo do “cimento” - apresentar uma nova face pública de solidez, longe do junkspace koolhaasiano? Esse era o problema das fachadas. Encontramos resposta na correspondência da estrutura com o módulo mínimo de uma divisão interior - o quarto - que, ao ser agregado, formava salas, ou, ao ser dividido, gerava varandas. Procurávamos uma certa densidade estrutural e, em escorço, praticamente só se veem colunas e respectivos entablamentos, conferindo-lhe um carácter potencialmente ornamental. No entanto, ironicamente, dado o pedido de desobstaculização estrutural dos interiores, com vãos não correntes, este contorno rígido das fachadas veio-se a revelar essencial. Montado o esquema, o mais divertido foi programá-lo: uma frente urbana em escada para coser as escalas da banda e dos blocos; uma Estoa moderna que atravessa os blocos em forma de pérgola e divide os jardins públicos criados; ou uma série de plataformas de estadia ao longo desses jardins. Porque, afinal, a grelha também se subverte.

BLOCK A

BLOCK B

BLOCK

DETAIL A

01. Self-protected mineral screen, black in colour, with RivEco-type finishing profile, 30/80, on both sides of the concrete beam, considering the joining profiles

02. Exposed concrete slabs, type a cimenteira do louro, 60x40cm laid on mortar bedding

03. Geotextile blanket, type impersep 200

04. Thermal insulation, type xps 12cm

05. Waterproofing membrane, type polyster 40 t

06. Waterproofing membrane, type polyster 30

07. Sloping formation layer

08. Exposed concrete structural beam

09. Rock mineral wool insulation, SMART ACOUSTIK type 7, by KNAUF, thickness 40mm

10. Mineral wool insulation, 80 mm thick

11. MAD4 acoustic membrane, DANOSA, 4 mm thick

12. 5 fixing points with L-shaped angle brackets 40 x 40 mm

13. ROP, pre-ring in anodised aluminium 120 x 20 mm

14. False ceiling composed of insulation in mineral wool or alternative with fire reaction class equal to or greater than B-s2 d0, thickness 12 cm + cementitious panel with busbar

15. Aluminium frames, 20 microns, fixed and with tilting side panel, type CORTIZO COR 70

16. Removable moulding in 19 mm lacquered MDF

17. Plasterboard moulding B13 plastered and painted

18. Guard in metallic and painted steel, with 8 mm rod balusters and 50x10 mm solid horizontal bars.

19. Leca

20. Levelling layer

21. Waterproof mortar, type MasterSteal 550

22. Draining screen

23. Azengar RC zinc threshold

24. Window frame lintel

25. Plasterboard moulding B13 rough with MAD 4 type acoustic blanket B13 in raw finish with MAD 4 type acoustic blanket

26. Natural-coloured polished anodised aluminium frames, 20 microns, fixed and with tilting side panel, type CORTIZO COR 70

27. Impactodan acoustic screen + lightweight concrete filling + underfloor heating and screed + Confordan comfort screen + multilayer flooring with European oak hardwood

28. Floor finishing profile

29. Blackout

30. ISOLA 2 45 grille, from FRANCE AIR, with self-regulating acoustic air inlet with CE2A and RA, flow rate 45m3/h, finish in Dark Beige RAL 1011

31. Aluminium window frames in matt bronze colour, 15 microns, with projecting opening, type CORTIZO COR 70

32. False ceiling composed of SMART insulation ACOUSTIK 7 40mm insulation + plasterboard

33. 12mm chipboard cladding veneered in oak on treated pine substructure 30mm x 50mm

34. Backing for installation of window frames

35. Anodised aluminium window sill

36. 15 cm thermal block + 2 cm plaster

37. Mineral wool insulation or alternative with fire reaction class equal to or greater than B-s2 d0, thickness 8cm

38. Concrete Pórtico 22 pigmented deactivated

39. Insulation with fire reaction class equal to or greater than B-s2 d0, thickness 12cm

40. Façade frame/cladding in lacquered aluminium substructure with lacquered aluminium rain screens

41. Exposed concrete block, thickness 10cm

42. Low concrete wall

43. Greenroof composed by: Substrate, ZinCo type, average thickness 50cm LECA plus screed, LECA Light Plus 8.82 MPa type filling and density 0.51 Kg/dm3 with 105kg CEM 32.5N cement,

Waterproofing membrane in APP plastomer bitumen with anti-root additive in the bituminous mass, reinforced with polyester reinforcement, protected with polyethylene on both sides Waterproofing membrane in APP plastomer bitumen with 3kg/m2 and fibreglass reinforcement, protected with polyethylene on both sides,

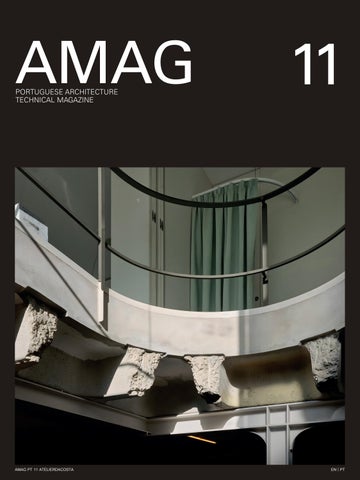

STUDIO COVER PROJECT

project: 2015 - 2018

location: Póvoa de Varzim, Portugal team: Hugo Barros, Pedro Matos, Marcos Veiga and Diogo Silva

client: ATELIERDACOSTA

construction: Autoconstrução + Serralharia Irmãos Rego engineering: GEP - António Matos Ferreira

gross built area: 120 m2 images: © Marc Goodwin, archmospheres

CARMO BUILDING

project: 2016 - 2018

location: Porto, Portugal

team: Hugo Barros, Pedro Matos, Pedro Oliveira, Raquel Bessa Serra and Eduardo Barros

client: Private, Noshi Coffee

construction: Costa Dias & Santos, Craveiro Cozinhas engineering: Torção, OHM

gross built area: 320 m2 images: © Tiago Casanova

BOUTIQUE AND BARBERSHOP

project: 2017 - 2018

location: Viana do Castelo, Portugal team: Hugo Barros, Diogo Silva, Pedro Matos and Raquel Bessa Serra client: Edghe Store

construction: Serralharia António Gomes da Silva gross built area: 85 m2 images: © Tiago Casanova

VACATION HOUSE

project: 2016 - 2019

location: Gemeses - Esposende, Portugal team: Hugo Barros and Pedro Oliveira client: Private construction: Costa Dias & Santos, Portilame engineering: GEP - António Matos Ferreira landscape: Paulo Palma gross built area: 280 m2 images: © Tiago Casanova

CAR PORCH

project: 2020

location: Terroso - Póvoa de Varzim, Portugal team: Hugo Barros, Pedro Matos, Raquel Bessa Serra and Ricardo Fernandes

client: VENDEIRO, SA construction: Manuaço, lda engineering: Manuaço, lda

gross built area: 150 m2 images: © Tiago Casanova

HOLIDAY HOME

project co-authored with Pedro Bragança project: 2017 - 2020

location: Porto, Portugal

team: Hugo Barros, Pedro Bragança, Ricardo Nunes and Eduardo Barros

client: Private construction: T M Construções

engineering: GEP - António Matos Ferreira

gross built area: 180 m2

images: © Tiago Casanova

PÓVOA RENOVATION APARTMENT

project: 2020

location: Póvoa de Varzim, Portugal

team: Hugo Barros and Pedro Matos

client: Private construction: Adelino Amorim + MAAM, lda + Fernando Matos

gross built area: 30 m2

images: © Tiago Casanova

RATES HOUSE

project: 2015 - 2021

location: São Pedro de Rates - Póvoa de Varzim, Portugal

team: Hugo Barros, Pedro Matos and Pedro Oliveira

client: Private construction: Silfermat

gross built area: 320 m2

images: © Tiago Casanova

CRESPO HOUSE

project: 2018 - 2023

location: Póvoa de Varzim, Portugal

team:Hugo Barros, Pedro Matos, Ricardo Nunes and Emanuel Neves

client: Private construction: Construções Mazesi

engineering: GEP - António Matos Ferreira

gross built area: 395 m2

images: © Francisco Ascensão

ENTREPAREDES BUILDING

project: 2017 - 2023

location: Porto, Portugal

team: Hugo Barros, Pedro Matos, Marcos Veiga and Raquel Bessa Serra

client: Private construction: Pedro Matos (construction coordinator), Costa Dias & Santos, António e Bruno Afonseca, Manuel António Amorim Moreira, Ricardo Rodrigues and Adelino Amorim

engineering: GEP - António Matos Ferreira

gross built area: 420 m2

images: © Tiago Casanova

QUINTA DO FREIXO

project: 2019 - under construction

location: Guilhabreu - Vila do Conde, Portugal

team: Hugo Barros, Pedro Matos, Ricardo Nunes, Catarina Salgado, Alexandra Salgado and Eduardo Barros

client: Private

construction: Costa Dias & Santos + New Sky + Hyline/BBG

engineering: GEP - António Matos Ferreira

landscape: Diaplant

gross built area: 2000 m2

images: © Francisco Ascensão

AV. 25 DE ABRIL BUILDINGS INDEX PROJECT

project: 2019 - under construction

location: Póvoa de Varzim, Portugal

team: Hugo Barros, Pedro Matos, Diogo Silva, Marta Nogueira, Carolina See, Marta Miranda, Margarida Martins, Emanuel Neves, Hannah Figliolino, Carine Amorim, Alexandre Brandão, Eduardo Barros and Catarina Dias

special thanks to the whole team developer and contractor, namely Sérgio Vendeiro, Joaquim Vendeiro, João Sá, Susana Pinto, Luís Araújo, Francisco Aguiar, Belmiro Vilar, Eduardo Baptista, among others client: Vendeiro Invest

construction: CCR - Construções Corte Recto engineering: GEP - António Matos Ferreira / TDP / HOOKE / ICONORTE / OHM / Susana Sousa

landscape: Habitat - Tiago Gonçalves

gross built area: 33 000 m2 total phases (phase 1 - 12 000 m2)

images: pages 001, 080, 086-087, 090 and 093 © Tiago Casanova page 082 © Francisco Ascensão

ATELIERDACOSTA

Since its foundation in 2015, ATELIERDACOSTA has received private and public commissions of various scales, both in the centre and on the outskirts, involving different levels of constructive complexity and economic constraints. Each specific request also introduces an apparent social and cultural subjectivity, to which different architectural “echoes” are given. In light of the limitations of the architect-ideologist model, the studio rejects the roles of educator and moraliser of clients. Instead, it embraces attentive listening and undertakes an in-depth, negotiated exploration of each problem, recognising that a project only matters as a document for construction and that it truly concludes — and often even begins — with the built work. This approach often results in the cultural, artistic and disciplinary amplification of the initial request, which at first seemed limited and subjective. Paradoxically, it becomes more objective and less limited. This would not be possible without the contribution of History, understood here as the living embodiment of the past that precedes us, supplying a map for the theoretical assembly of the project. During the development of each of these ‘cocktails’, it enables the request to be ‘geo-located’ as the project progresses. From the beginning, ATELIERDACOSTA has gathered friends to work in the studio, as well as other friends — architects, plumbers, electricians, carpenters and engineers — who discuss everything, including the work itself. The studio is currently made up of partners Hugo Barros and Pedro Matos, as well as Marta Nogueira, Carolina See, Alexandra Salgado, Alexandre

Brandão, Hannah Figliolino and Eduardo Barros. The studio has offices in Póvoa de Varzim and, more recently, in Porto. Hugo Barros, the coordinating architect, holds a Master’s degree from FAUP and also studied at the Accademia di Architettura di Mendrisio. From 2012 to 2013, he worked at David Chipperfield Architects in London. He has been invited to present ATELIERDACOSTA’s work at various events, including classes, conferences, exhibitions, workshops and publications. Notably, the Greek magazine DOMA published a notebook on the ‘villas’ they designed. Hugo Barros has been nominated for several awards, including the National Wood Architecture Award, the “Forma” Awards and the Young Architects Award (Prémio Jovens Arquitectos). He won the latter in 2023 for the “Casa de Férias” project. In addition to his architectural work, he has also designed sets for various theatre and dance productions.