29 November – 2 December 2024

Edited by Nico Steytler

Eva Maria Belser holds a Chair in Constitutional and Administrative Law at the University of Fribourg in Switzerland and a UNESCO Chair in Human Rights and Democracy. She is also the co-director of the Institute for Federalism.

Jennica Beukes is a Post-doctoral Fellow at the Dullah Omar Institute for Constitutional Law, Governance and Human Rights, University of the Western Cape

Susan Booysen is Director of Research at the Mapungubwe Institute for Strategic Reflection (MISTRA), a Professor Emeritus at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, and a visiting professor at the Wits School of Governance

Tinashe Chigwata is an Associate Professor and Head of the Multilevel Government Project at the Dullah Omar Institute for Constitutional Law, Governance and Human Rights, University of the Western Cape

Anél du Plessis is a Professor of Law and the Chair in Urban Law and Sustainability Governance at the Faculty of Law, Stellenbosch University

Jaap de Visser is the South African Research Chair in Multilevel Government, Law and Development. He was formerly the Director of the Dullah Omar Institute for Constitutional Law, Governance and Human Rights, University of the Western Cape

Ebrahim Fakir is a Consultant Analyst at the Electoral Institute for Sustainable Democracy in Africa (EISA) and a Research Associate at the Centre for African Diplomacy and Leadership at the University of Johannesburg

Gaopalelwe Mathiba is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Private Law at the University of Cape Town.

Benyam Dawit Mezmur is a Professor and head of the Children’s Rights Project, Dullah Omar Institute for Constitutional Law, Governance and Human Rights, University of the Western Cape.

Paul Mudau is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Public, Constitutional and International Law at the University of South Africa (Unisa)

Christina Murray is a senior member of the Mediation Support Team of the United Nations’ Department of Political Affairs

Xavier Philippe is Professor of Public Law at Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne University, France, and an Extraordinary Professor at the University of the Western Cape.

Theunis Roux is a Professor of Law and Head of the School of Global and Public Law, University of New South Wales, Australia

Nico Steytler is a Professor Emeritus and the former South African Chair in Multilevel Government, Law and Development at the Dullah Omar Institute for Constitutional Law, Governance and Human Rights, University of the Western Cape

Karin van Marle is the Research Chair Gender, Transformation, Worldmaking at the Faculty of Law, University of the Western Cape.

Yonatan Fessha is a Professor of Law and the Research Chair in Constitutional Design for Divided Societies at the Faculty of Law, University of the Western Cape

Zemelak Ayitenew Ayele is an Associate Professor at the Centre for Federalism and Governance Studies, Addis Ababa University, and an Extraordinary Associate Professor at the Dullah Omar Institute for Constitutional Law, Governance and Human Rights, University of the Western Cape.

After successfully holding the first Mont Fleur Conversations event in December 2022, the South African Research Chair in Multilevel Government, Law and Development (SARChI Chair) at the Dullah Omar Institute of Constitutional Law, Governance and Human Rights held the next edition two years later in November / December 2024 Whereas the first Conversation was on the broad topic of constitutionalism, the second meeting narrowed down on one aspect of constitutionalism – democracy and development: government by the people, for the people.

Building on the model of the first Mont Fleur Conversations, the aim was not to pursue the usual format of presenting papers followed by a Q&A, but to engage in conversations and blue-sky thinking on the fundamentals of democracy Given the challenges emerging from both the theory and practice of democracy, what new thinking does they prompt? Is there an orthodoxy that needs to be challenged? How could we look innovatively at the various aspects of democracy implied by ‘government by the people, for the people’?

Blue-sky thinking involves a group of people looking at problems and opportunities with fresh eyes; more ambitiously, it is the activity of trying to find completely new ideas regardless of practical constraints It is the proverbial ‘thinking outside the box’ It may entail radical, visionary thinking that questions the very premises of orthodoxy The purpose was thus to have in-depth conversations on the current orthodoxy in the field of democracy, reflect on whether it is still fit for purpose, and consider what future research agendas should be.

To enhance the quality of the conversations, the conference was limited to a small group The participants all have a deep interest in democracy, given the perilous state of democratic governance across the world. In the end, 17 persons could attend. Some were participants of the first Conversations, but the majority were new minds. There was a balance of experienced academics and up-and-coming younger scholars The majority were from South Africa, but the necessary broader international perspectives were given by Xavier Philippe (France), Eva Maria Belser (Switzerland), and Zemelak Ayele (Ethiopia)

The participants were mainly lawyers, with a sprinkling of political scientists among them

As no formal papers were delivered, the usual format of a volume of peer-reviewed conference proceedings was not envisaged However, the lead-in pieces, comments on them, and fireside stories were of much value and the intention was to capture them in a publication of some kind Unfortunately, the oral discussions could not be included in the publication due to difficulties in recording them This is, hence, an informal publication intended to document the conference by presenting the written contributions as well as a pictorial rendition of the event.

Neither the Mont Fleur Conversations nor this publication would have been possible without the support and engagement of a number of institutions and persons

The National Research Foundation, through the SARChI Chair, provided the resources and space for such a gathering to be held

The Mont Fleur Conference Venue was ideal for this venture The management and staff excelled in providing an environment conducive for blue-sky thinking; they accommodated any request – whether for a sundowner in the mountain or one on Kogel Bay beach – with warmth and a smile

The staff of the Dullah Omar Institute were at their usual best in the organisation of the event and the production of this publication: Laura Wellen, Keathélia Davids, and Kirsty Wakefield Particular mention should be made of Curtly Stevens for all his organisational work

A number of volunteer photographers admirably captured the spirit of the event and kindly gave permission for their images to be published: Gaopalelwe Mathiba, Paul Mudau, Tinashe Chigwata, Jaap de Visser, and Eva Maria Belser Thanks also go to André Wiesner for his incisive editorial eye

Finally, the success of the gathering (and this publication) must be attributed to the participants Their enthusiasm, energy, and embrace of a new format of academic engagement and willingness to share a fireside story, made it happen Thank you!

Nico Steytler

Cape Town

October 2025

The Conversations explore democracy along two themes The first is the development of democracy: government by the people. This focuses on the procedural aspects of democracy – how is the will of ‘the people’ formed? The second theme hones in on more substantive aspects – how can the elected representatives govern ‘for the people’ as a whole?

‘unelected’localpower Yet,atthesametime, localgovernanceisseenasthebasisonwhich ademocraticcultureisbuilt–democracyfrom thebottomup

Questionsincludethefollowing: How can local democracy anchor or supportanationaldemocraticethos? Howcanlocalgovernmentexperimentwith newmodesofdemocraticrepresentation? Istherestillscopeforcollectivevillage-like government?

The second theme of the Conversations focuses on the more substantive aspects of democracy–howcanelectedrepresentatives govern‘forthepeople’asawhole?Therecan nolongerbeanassumptionthatgovernment ‘by the people’ automatically leads to a government‘forthepeople’.Inthiscontext,we usetheconceptof‘development’:governance that increases the material and social wellbeingofthepeopleasawhole

Democratic governance and inclusive development

The experience of liberal democracies is that they often serve narrow political interests Party-driven majoritarian decision-making is not delivering inclusive development. It is at this juncture that the democracy sceptics of theGlobalSouthcometothefore.Theyclaim

demographics yet the actual governing institutions and outcomes do not align with them

Theparadoxofundemocratic representation:Acontradictioninterms

Just as representative democracy may yield unrepresentative governance, the inverse is also conceivable: undemocratic systems may produce representative governance. An authoritarianregimemightincorporatediverse representation even though representatives are not held to account through periodic plebiscites, do not exercise oversight of its performance, and are not required to be responsive and answerable Elections may occur but be heavily controlled and manipulated, or representative institutions may be constituted through diverse appointments, prescribed quotas, reserved seatsandallocatedposts

Inthelatterinstance,theprocessofacquiring power might be unrepresentative and exclusive,but,counterintuitively,theprocessof administering power can be representative and inclusive, even though its eventual outcomes may not be – as the apartheid-era tricameral parliament and bantustan system demonstratedintheirshamrepresentivityand inclusivity.Apartheidwasunderpinnedbythe ideaof‘separatebutequal’,butitwas,of

democracy facilitates the capture of power through popular participation, democratic governance constrains and regulates the exerciseofthatpower

Theimperativeofdemocraticpolitics

Democracyhasmanyparadoxesduetoits simultaneouscontradictorycommitmentsto: majorityruleandminorityprotection; individualrightsandcollectivewelfare; politicalequalitybut‘economicfreedom’to exploit; aspirations to equality perpetuating inequality; facilitating the capture of power but imposingconstraintsonitsuse;and enablingrepresentationyetfailingtoreflect the full diversity of societal values and opinions

Yettheseparadoxesalsoaffirmitsenduring value as a system that creates space for contestation,redistribution,andthepursuitof equity.Ultimately,thesuccessofdemocracy dependsnotonitsstructuresalonebutonthe politicalcultureandpracticesthatsustainit. So, despite these contradictions, democracy hasthecapacitytomediatetensions,foster participation,andenableredistribution–and thismakesitpreferabletoalternativesystems. However,itsefficacydependsonwhowieldsits toolsandinstruments,andtowhatend.

Poor(asinbad)politicsorundemocraticpoli-

Theparadoxesrevisited:Representative democracyandrepresentative government

In contemporary politics, these tensions are exacerbatedbysystemicelitecapture,where influenceoverthepoliticalprocessbecomes concentratedinnarrow,self-servinginterests Thisphenomenoniscompoundedbyashortterm orientation that prioritises immediate gains over long-term sustainability Furthermore, the complexities of technomodernityalienatepeoplefromtheinstitutions meanttoservethem,erodingtrustandpublic engagement.

Representative democracy, historically celebrated as the pinnacle of democratic government,nowfindsitselfundersiege Its foundations appear increasingly illusory, inadequate, and even dangerous While premised on the delegation of decisionmakingtoelectedrepresentativestaskedwith actinginthepublicinterest,itparadoxically disempowerstheverypeopleitismeantto serveThisdisempowermentarisesnotmerely from procedural deficiencies but from structural flaws that breed disengagement, alienation,andacrisisoflegitimacy

Electedrepresentativesareoftenperceivednot asagentsofthepublicwillbutasmembersof adetachedpoliticalclass–onethatoperates ‘initself’and‘foritself’(withapologiestoMarx)

The participation problem also centres on disillusionment with unresponsive political institutions, which are seen as corrupt or dominated by elite interests This perception fosters both disempowerment and disengagement Global and regional integration,supra-nationalinstitutions,andthe rise of technocracy mystify already complex processes of governance, rendering them opaque.This,coupledwiththedelegation(or outsourcing) of key decision-making to unelected bureaucrats and technocrats, or to supranationalinstitutions,hasalienatedpeople from the political process even further; meanwhile,thepowerandauthoritygivento unelected bureaucrats, technocrats and consultants locates decision-making and accountabilityawayfromthelocusofelected publicinstitutionsandrepresentatives.Where supervision and oversight by elected representativesoverbureaucrats(officials)and outsourced or subcontracted consultants is weak, accountability and answerability are furthereroded.

Contradictorily,digitaldisruption(AI,machine learning,robotics,apps)hasmadethisworse. Although digitalisation and technology platforms have democratised access to information and expanded avenues for participation,theyhavefragmentedpublic

hegemony of the African National Congress (ANC) Once unassailable, the ANC now faces theerosionofitsdominanceandriskslosingits position as the majority or even the largest party Itsdeclineismoststrikinglyillustratedin KwaZulu-Natal,whereitisnolongereventhe second-largestpoliticalforce

This erosion of political dominance is not inherently negative On the contrary, it underscoresanencouragingdynamicinSouth Africanpolitics:nopartycantakevotersupport for granted. In a system of almost pure proportional representation, this dynamic provides an opportunity to recalibrate the accountability-responsiveness nexus, provided electoralreformcanincentivisegoodpolitical andgovernancebehaviourwhileinhibitingand disincentivising errant governance behaviour manifested in maladministration and malfeasance

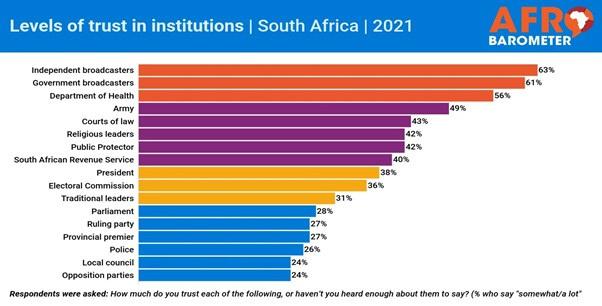

South Africa evidently does not have a democracy problem, but it certainly has a democraticgovernanceone Thelegitimacyof its democratic institutions is unquestionable buttheircredibilityisnot.Sincetheadventof democracy, the promise of a responsive and representative government has been continually deferred, undermined as it has beenbyself-servingpoliticsamongstboththe governingpartyandtheoppositionandthe

Table 1: Confidence in select institutions 2017-2023

officialsingovernmentadministration,aswell astheover-politicisation,evenfactionalisation, of the public service, has enabled malgovernance,corruptionandtherepurposingof the state and public institutions towards private,predatoryends.

The configuration of the electoral system incentivises this by giving license to the anomalousabuseofmajoritiesincrudeways, thusinhibitingeffectiveoversightandallowing apoliticalcultureunderpinnedbyimpunityin theexerciseofpowerandauthoritytoflourish

Theelectoralsystem:Representation andresponsiveness

SouthAfrica’selectoralsystem,designedinthe early post-apartheid era, employs closed-list proportional representation (PR) to ensure inclusivityanddiversityinasocietyscarredby segregation While this system has brought diversevoicesintothepoliticalarena,ithasalso fostered fragmentation. Although the 2024 elections were conducted under a new electoralsystem,itisadeficientonereplicating the dysfunction wrought by the pure PR system in which party loyalty supersedes publicinterest MandatedbytheConstitutional Court to accommodate independent candidates, the new electoral system has remainedessentiallyaparty-list,compensatory PR system that simply accommodates independentcandidateswithinthisframe

The electoral system’s design has privileged ‘proportionality,inclusivity,representativityand diversity’ at the expense of ‘oversight, accountability and responsiveness’, as well as sacrificing citizen ‘voice and choice’. System designcantrytoprivilegeallequally,butthat would result in a system of such complexity that it would be almost impossible to administerandmanageit,creatingproblems fortransparencyandoversightmechanismsin theelectoralprocess Itwouldalsolenditselfto gerrymandering, process manipulation, and procedural abuse This would open up new spaces for conflicts and flashpoints, as has beenthecaseintheDRC,Kenya,Malawi,and Lesotho, where the tabulation of results can cast a pall of doubt on the credibility of electoralprocessesandconsequentlyserveto delegitimiseelectoraloutcomes.

Two frames should be borne in mind when changing the system First, altering the incentive structure for political behaviour for people(voters)andpoliticalparties,individuals andorganisationstofosterdeliberation,voice and choice at the most proximate level; and secondly, improving the architecture of representation, oversight, accountability and responsiveness architecture To this end, the followingcouldbedone:

councillors Thisisshoredupbyasystemthat allocates each PR councillor to a ward in addition to the ward councillor, ostensibly to complementtheroleandfunctionoftheward councillor In practice, this tends to breed competition and conflict rather than cooperation (especially if the PR councillor deployedtothewardisfromadifferentparty to the ward councillor), sowing the seeds of suspicion and the perception that the PR councillor is in some way a supervisory overlord Even if the councillors are from the sameparty,withfactionalisedandfragmentary partiesbeingrife,thisremainsaproblemWard councillorsandindependents,whocanonlybe ward councillors, serve as community communicationconduits,yetthoughthisisan importantroletheyarenottakenseriouslyby headsofserviceunitsandutilities,whooften undermineorignorethem

The system is thus exclusively party-centric, andchangingthiswouldrequireachangein theConstitution.

The current mixed system is not serving its intended purpose, either in theory or in practice

The local government electoral system should me made an exclusively first-pastthe-post(FPTP)one,orshouldbemadean exclusively PR system (which the Constitutionmakesprovisionfor,butwhich, ifitweremadeexclusivelyPR,would

democratsrepresentingthe‘people’;buttheir aimistoretainpowerwhatevertheprice

ThisfitsperfectlyintoEbrahim’sremarkabout the distinction between representation and governmentbutgoesbeyondit.Thosewho

democracyandtheirimplementation,thereis ahugegapthatmanyoftheargumentsinthe lead-in paper illustrate. However, the crisis seemsmuchdeeper,asthequestiondoesnot concern the difference between what democracyisandshouldbebutrathertheidea ofdemocracyitselfanditsabilitytorepresenta modelasapoliticalregimeandasanidealof governanceToacertainextent,thequestionof goingbacktotheoriginofdemocracyseems unattainable There is a need to reinvent a democratic form of representation and governancethatwouldbebothworkableand acceptable for the people The latter do not necessarilywantaperfectdemocraticsystem but rather one in which they can have their voices heard in one manner or another However,thequestionishowtodothat,and with what kind of toolbox? That is yet to be invented.

The crisis of democracy – I mean liberal representative democracy – also lies in much broaderfactorsthanpolitics:economic,

utilised to respond to diverse interests and structuralinequalitiesthatprevailinsociety. ThereisbroadconsensusthatSouthAfricahas soundlegislationandpolicies,whichareaimed ateradicatingstructuralinequalitiesHowever, it is implementation and compliance with themwhichislackingTherefore,itcannotbe

policiesbytheadministration? Whatresourcesarerequiredtoensurethat top management structures have the capacitytoimplementtheadoptedpolicy? How can the institutional rules of legislatures be strengthened to enhance oversight and accountability of executive politicaloffice-bearersinrealisingthepolicy agendaofthelegislature?

HowcanChapterNineinstitutionsplaya roletoenhancetheresponsivenessofthe legislatureandexecutiveingivingeffectto suchpolicies?

Addressing these questions will lead to the conclusion that achieving responsive governance in South Africa’s representative democracyrequiresamulti-facetedapproach, oneinvolvinginstitutionalstrengtheningand reformacrossvariousgovernancestructures, includingthepublicadministrationGiventhe complexityofdemocraticgovernanceinthe 21 century,thetimehascometoconsider whether access to executive political officebearer positions should be conditional on possessingtherelevantskills,knowledgeand expertise necessary to effectively oversee governmental departments. This, in turn, wouldenabletheexecutivetoidentifyareasof dysfunctionality within government and support top management structures in addressingshortcomingsthatimpedethem

on democracy, citizenship and political decision-making Staying with difference, I recallJacquesDerrida’swritingondemocracy inThepoliticsoffriendship(1997)and,also pertinentfordemocracy,hislaterturntoautoimmunity(2005).Ialsoconsiderhiswriting(in 1997)onthefailureofcosmopolitanismand hospitality and what it discloses about inclusivity

Secondly, I briefly recall Wendy Brown’s critique of neoliberalism and the way it destroys all notions of a public good in its insistenceondecision-makingdrivenbythe market,individualismandself-interest,whichI regardasaninsistenceonsamenessanda disregardfortheethicaldifferencethatisat stakehere.Iturntoherlatestcallforreparative democracy

Lastly,IdrawonexamplesfromSouthAfrican constitutional discourse to read the shift to constitutionalismasanembraceofapublic andaturntodemocracyanddifferenceaway fromthenarrowprivatismofsubjectiverights groundedbysameness.Thisshiftcouldprovide awaytodiscloseopportunitiesforparticipatory livingandtohearandlistentoandrespectthe voicesofall

Difference,democracyandthefailureof cosmopolitanism

IrisMarionYoung’sadviceforthoseinsearchof

[13] [14]

Intimately tied to the idea of impartiality is the opposition between public and private The state insists on impartiality and universal reason, which is related to public reason The private is related to the body, affectivity, desire The expression of citizenship as the ideal of unity based on universality and impartiality results in the exclusion of anyone threatening this very unity of brotherly sameness This expression for homogeneity is based on the necessary exclusion of certain persons and groups, women, black people and other marginalities that are ‘identified with the body, wildness, and irrationality’ In Young’s view (which I support), inclusivity can be best achievedbyinsistingnotonunifieduniversality but rather heterogeneity and difference Instead of ‘consensus and sharing’ being the goal, a public should be open to ‘recognition andappreciationofdifferences’

[15]

‘Oh my friends, there is no friend’ is the introductory sentence of Derrida’s The Politics of Friendship (1997), in which he exposes the betrayal of ‘democratic equality’ by exposing how all friendships turn on exclusion All friendships in fact become nothing but relationsoffraternity,‘naturalizedfriendship’.

interrogated Blame for the failure of democracycan’tbeplacedsimplyonoutside forces but on the inherent structure of democracy that disrupts the distinction betweeninsideandoutside

Arendt’s writings on ‘The Decline of the NationState and the End of the Rights of Man’ (1967), in which she introduces the stateless and the homeless, the deported and the displaced Two specific occurrences should be noted First, the progressive abolition of a right to asylum, followed by the abandonment of the right to repatriation or naturalisation on which the right to asylum depends. Again, Derrida asks if the city, the city of refuge, could stand in where the state fails? Could the city effect a better way to include? Of course, this could be found only in a new idea of the city: ‘we are dreaming of another concept, of another set of rights for the city, of another politics of the city’ [23] [24]

Reflectingoncosmopolitanism,Derridaasksto what extent we can hold on to a legitimate distinctionbetweentheCityandtheStateas twoformsofthemetropolis Heisdoubtfulas towhethercosmopolitanismstillhasanything tooffer.Howcanwe,whenconfrontedwiththe ‘endofthecity’,stillimaginethepossibilityof ‘citiesofrefuge’?Heisclearinhisviewthat‘the merely banal articles in the literature of internationallaw’willnotbeofanyhelp What would‘agenuineinnovationinthehistoryof therighttoasylumorthedutytohospitality’ entail? ForDerrida,theveryideaof‘citiesof refuge’ should bring forth a ‘new cosmopolitics’ and ‘forms of solidarity yet to be invented’ that ‘reorient the politics of the state’ He asks what it would entail to go beyond the historical meaning of the word ‘hospitality’, which includes the duty of hospitalityandtherighttohospitality?Couldit be ‘adapted’ to respond to unforeseen crises thatpresentthemselvesnowtous? [19]

Derrida does not shy away from naming the stateaswellasnon-stateorganisationsasthe instigatorsofviolence Hetellsustoturntothe city rather than the state in this search for a newpoliticsornewmeaningDerridaturnsto

Derrida writes that the notion of the city of refugebridgesseveraltraditions Thefirstis the Hebraic tradition, in which the right to refugewasdevelopedanddefended Herecalls writings by Emmanuel Levinas and Daniel Payot as examples of texts honouring this tradition Secondly, he identifies in the medievaltradition‘acertainsovereigntyofthe city’, where cities could decide how to apply the laws of hospitality Thirdly, the cosmopolitan tradition, initially linked to a Greek and Pauline tradition but later secularised. In this secularised version, Kant’s law of cosmopolitanism, limits are imposed Although cosmopolitan law initially seems to beunconditionedandwithoutlimit,Derrida’s analysis shows the opposite, namely that the earth ultimately is not unconditionally accessible to everyone Two further consequences: hospitality for Kant remains merely a right of visitation, not of residence; and hospitality is ultimately dependent on statesovereignty [27] [28]

Derrida,ofcourse,doesnotofferanyofthisasa final word, and urges that we should not believe we have mastered any of these complex thoughts. He leaves us with the suggestionthatanybetterwaywillhavetobe

However, we must realise too that neoliberalism can’t be blamed for everything: ‘Ecocide has been intensified by deregulated capitalandstatesincreasinglysubordinatedto institutional finance but is older and bigger thanthese’[31]

Brownreiteratesthatreparativedemocracyisa direct response to the ‘consequential exclusions, violences, and individualist and presentist orientation of modern democracy acrossitsliberal,social,andsocialistvariants’ Shebelievesthatthecurrentcrisispresentsus with possibilities of ‘curiosity, learning, reorienting,transforming’ Thepoliticalrightto beheardshouldbecomemuchstronger She callsforashiftfromspeakingtolistening: [32]

SouthAfricanconstitutionaldiscourse: Democracy-seeking,acknowledgingstreetbasedhomelesspeople

I indicate above that I read the shift to constitutionalismanditsembraceofapublicorientationasashiftaswelltowardsdifference andopennesstoadheretovoicescomingfrom outsidethetraditionalfoldPerhapsherethe

TheyfocusonthecaseofNgomanevCityof Johannesburg and criticise the court for missing an opportunity to interpret eviction legislation in a way that could have included street-basedpeopleinameaningfulway The authorssuggestanumberofaspectsofwhat the right not to be evicted from one’s home may entail. For the purposes of inclusive decision-making, I am interested in their emphasis, relying on PE Municipality, on the ideaof‘nestedness’and‘nestedrelations’ They argueforanevictionjurisprudencethatmakes participation central to its evaluation – the meaningordefinitionof‘home’shouldinclude theviewofthehomeless.

TheNgomanecasetracestheplightofagroup ofabout30street-basedpeoplewhosettledon a traffic island under a highway bridge in downtown Johannesburg and lived there for aboutfiveyears.Duringthedaytheymadea smallearningand,atnight,bymakinguseof cardboardboxesandothermaterial,createda sortofhomeforthemselvestosleepin Inthe mornings,theydismantleditandleftitonthe island One day, Johannesburg Metropolitan Police Department officials arrived at the island,drovetheinhabitantsoftheislandaway, destroyed their homes, and took their belongings away. The Ngomane group challengedthisintheHighCourt,arguingthat

7. Based on Klare, Van Marle advocates for a constitutional duty of democratic societies to nurtureinallhumanbeingstheirinherentbut oftenblockedorunderdevelopedcapacitiesof self-realisationinpoliticalandpersonallife

8. Based on Brown, Van Marle calls for reparativedemocracyreplacingthehistorically exhaustedliberaldemocracycharacterisedby self-interest, violence, and the exploitation of humansandnon-humanresources Reparative democracyovercomestheoppositionbetween humanityandnature,aswellasindividualism and presentism, and allows for the entanglementofhumans,animals,plants,and other non-human entities and the past, presentandfuture

1. If difference must be ‘placed central to all takes on democracy and political decisionmaking’,whatdoesthismean–intheoryand practice? Is there a need for frameworks to adapt, a necessity to create new institutions andprocessesbuiltondifference(andnotjust open to it), or a need for alternative, parallel frameworks interacting with the established ones?

2.Ibelievethatradicalopennesstodifference is not sufficient but requires both – that is, incrementalchangestotheframeworksaswell as their radical redesign. By incremental changes,Imeanadaptationsofthesystem

Solutionstolocalproblemscanbeaddressed more effectively because of better local informationSincegovernmentisclosertothe people, citizens can more readily hold their representativestoaccount

Thanks to the existence of multiple policy decision-makingpointsatdifferentlevelsof government, the prospects for multiparty democracy are enhanced Other than in authoritarian regimes where one party’s hegemony is absolute at all levels of government,amultilevelgovernmentsystem allows for opposition parties to gain ascendencyatsomeorotherlocality This,in turn, fosters political tolerance among governmentscontrolledbydifferentparties–a hallmarkofdemocracy

Finally,giventherelativesmallnessinsizeof subnationalgovernments(SNGs),participatory democracyismoreeasilyimplementable The enthusiasm for the tight coupling of federalismanddemocracyasself-ruleisnot universallyshared,however,asitisempirically suspect

Whilethereismostoftenascrambleby candidates to contest multiple opportunities for elective office, public interestinsubnationalpoliticstendstobe muchlowerthaninpoliticsatthenational level, matching SNGs’ low status and meagrepowersandownrevenue

model has permeated federal thinking ever since.

Thedivisionofpowersispersealimitationon centralpower.Recentexamplesofthevalueof thisaretobefoundinBrazilandtheUSinthe management of the Covid-19 pandemic: the denialistapproachofthefederalgovernment at the cost of citizens could be countered in somestateswithcontrarypreventionpolicies. At executive level, the necessity of intergovernmentalrelationsbetweendifferent levelsofgovernmentinthedeliveryofcrosscutting services allows for co-operation and comprise,thussecuringbroaderacceptanceof policy outcomes Furthermore, SNGs may provide a higher level of human rights protectioninbillsofrightsthatgobeyondthe nationalstandard

Forsomescholars,however,theveryvalueof constraining majority rule is a major flaw in federalism’sdemocraticcredentials Thenotion of equality between states in the second chamber of the national legislature, as is the caseintheUS,isscoffedat,andanumberof federationshaveameasureofproportionality based on population size, as is the case in Germany

Similarly, for some critics, the very notion of sharedruleisnotanindispensableelementof federalismsolongasthereisrobustprotection ofself-ruleNoconstraintsareplacedonthe

counter and resist denialist policy at the nationallevel Wherethescopeofsubnational rule-makingisweak,forexampleinGermany (where the national legislature adopts most legislation,whichisthenimplementedbythe states), the democratic participation of those subjecttotherules,theLänder,shouldhavea sayintheircontent Muchisalsotobesaidfor the principle of broadening decision-making beyondsimplemajorityrule

The South African provincial system of multilevelgovernmentismodelledlargelyon the German system. The most important competences are allocated to the national government, including almost all taxing powers Even in the field of concurrent competences, national legislation predominates. Provinces are thus concerned mainlywithimplementingnationallegislation and are funded almost entirely by national transfers that seek to ensure equalisation of provincial resources Provinces participate in national decision-making through the NCOP andthesystemofintergovernmentalrelations

For the purposes of this conversation, the questioniswhetherprovinceshaveenhanced democraticgovernancealongthethreeaxesof self-rule, minority accommodation, and constraining majority rule. What is the provincialtrackrecordofthepast30years

National Assembly and the NCOP, the ANC retains its control of the NCOP, with direct control of five of the nine provincial delegations, resulting for the first time in a non-alignmentwiththeNationalAssembly What does the GNU hold for provinces and democracy?

First,boththeDAandInkathaFreedomParty (IFP), strong proponents of federalism, will pushtheGNUtowardsdevolvingmorepowers toSNGs(forexample,policingandtransport), makingthelattermoreimportantdemocratic decision-makers Atprovincialandlocallevels, theANC’sstrictpartyhierarchyhasgivenway to locally decided coalitions, reducing central party control over subnational decisionmaking This is also likely to result in more vigorousdebatesinprovinciallegislaturesand relationswiththeGNU

On the negative side, the GNU may also impede democracy As far as representative democracyisconcerned,votersforopposition partiesnowintheGNUwereflummoxedwhen their party leadership did not keep their electionpromisenevertoco-operatewiththe ANCMoreover,thecoalitionagreementwasan elite pact without the support of party members

Secondly,theMay2024electionsforegrounded theethnicwatermarkofSouthAfrica’sfederal

direct link between the exercise of political power and local taxpayers is vital for political accountability Given the deplorable state of governance in a number of provinces, these democracy-enablingmeasureswouldhaveto be balanced by nuanced and objective measures of national intervention to protect peopleagainstprovincialineptitude

Secondly,thesoftaccommodationofethnicity should continue to ensure that perceptions that particular ethnic or linguistic groups are marginalised do not take root The prevailing political culture of the major political parties havingnationalvisionsshouldbefostered Thirdly,canandshouldprovincesplaytherole ofconstrainingmajorityruleatthecentre?To theextentthatcapableprovincesareendowed with more self-rule powers than others, provincialsegmentsofthepopulationmaybe protected against the tyranny of national ineptitude Amoredifficultquestionhastodo withthenecessityforandmodalitiesofsharedrulearrangementsthatconstrainmajorityrule atthecentre AprimeexampleistheNCOPas an institution that could veto majority decisionsintheNationalAssembly

TheNCOPisbasedontheUSprincipleofthe equality of states: Gauteng, with 16 million people,andtheNorthernCape,with13,have one vote each Following the May 2024 elections,thefollowingscenarioistheoretically

governing party. It therefore could be that SouthAfricaentersaneraofevenlessdualistic relationship between the legislature and the executive

As far as opposition politics from outside the GNUisconcerned,itishardtopredict.TheEFF,

dividends? I agree with Steytler’s assessment: provinces have not brought significant democratic dividends to the table. This is mainly due to how competencies and taxing powers are distributed between levels of government;itisalsoduetotheelectoral

federal ‘culture’ develops Moreover, the biggest challenges confronting effective provincial governance are corruption, skills

Christina Murray

Andinthatway(andthisismyconcern),the constitutional entrenchment of municipal autonomy has resulted in local democracy becomingatruism,i.e.,soobviouslytruethatit hasbecomeunhelpfulandunnecessary

To examine this further, let’s turn to the practice of local democracy in South Africa What happens in practice in municipal councils? Are locally elected representatives indeed seized with translating community preferences into municipal policy and with conducting oversight of the municipal executive and administration? Are municipal council meetings sites of robust but civil democratic debate, events where local democracyflourishes?Sadly,theanswerisno

First,ourlocalpoliticsishardlylocal,letalone community-oriented Most municipal councillorsrepresentnationalpoliticalparties, and their calculations are influenced, if not determined, by the need to ingratiate the party When the chips are down, instructions from national or regional structures trump localconcerns

Secondly, many municipal councils are dysfunctional Instead of legitimising and checking government decision-making, they oftenfaillocalcommunitiesAttherootofmost municipal crises is a dysfunctional municipal council At times, these councils cannot performthemostbasictasks,suchas

toleratedaspartofatransitionalregime,the acceptable remnants of a prior, centralised regime, or the integration of multiple legal orders.Inthesamevein,countriesthatadopt decentralisationpoliciesbut‘dragtheirfeet’on ensuring that local leadership is elected throughregularandcompetitiveelectionsface verylittlepressure Itisregardedasadomestic matter.Theprincipleoflocaldemocracydoes not(yet)havethesameuniversalmoralforce as the need for the democratic legitimacy of national leaders, and tolerance levels for an absenceoflocaldemocracyarehigherthanfor an absence of democracy at national level It maybedifferentinthememberstatesofthe European Charter on Local Self-Government, theonlyinternationalinstrumentthatpursues localdemocracyasanissuethatisnotjusta domesticaffair

In the South African context, another important marker in our examination of the real,asopposedtodogmatic,currencyoflocal democracy is the incursion into it by private entities and private initiatives, often to the acclaimoflocalcommunitiesandthegeneral public who are exasperated by municipal failure Privateentitiesareincreasinglytaking over public functions that the Constitution expects to be performed by (democratically elected)localgovernments.Thereisatrendof private entities taking over municipal functions,particularlyinresponsetoweak

I argue that, when the all-too-familiar indicators of municipal collapse are present, political discretion as to whether or not to intervene and tip-toing around the preciousness of local democracy should be removedfromtheequation.Thismayrequire revisiting the institutional structure for intervention The current framework makes provincial and national politicians responsible for deciding whether the residents of a collapsed municipality deserve their (continued)protectionagainstadysfunctional council This renders interventions unpredictable at best and their implementation, too reliant on continued political support. In my view, the decision should be made and implemented by an institution that operates at an arms’ length fromgovernment Furthermore,afteraquarter of a century of monitoring and evaluating municipalities, national and provincial governmentsoughttobeabletoformulatea numberofkeyindicatorsthat,whenpresent, resultinautomaticintervention Isitthathard to agree that, when the Auditor-General has issueditsthirdsuccessiveadversefindingona municipality’sfinances,theaxehastofallonits politicalleadership?

Itmaybethatmycynicismaboutaprincipled approach to local democracy is flippant, or coloured by resentment at those politicians whoravagedasystemthatwasdesignedwith

working side by side with councillors. This alternative seems to be suggesting a partial depoliticisation of local governance. Could it work?Perhaps,perhapsnot

Despite its likelihood of success in shifting thingsforthebetter,thisoptionisproblematic if by ‘non-political entities’ we mean private (andright-wingedcapitalistelite)entities–i.e., thetechnocrats Thepropositionisnotonlyat oddswiththeConstitution–whichentrenches

election by universal suffrage. Classic analysis saw democracy, in the sense of election by universal suffrage, as a threat to economic growth, since democracy, just as with autocratic systems, was seen as a threat to privateproperty. Theconservativeviewinthe 19 centurywasthatgrantingvotingrightsto theworkingclasswouldleadtotheeradication ofthesystemthatprotectedprivateproperty

In addition, it was argued that workers, especially when organised in trade unions, wouldpushforsalaryincrements,resultingin reducedprofitandinvestment,whichinturn wouldleadtosloweconomicgrowthor,even worse,economicstagnation

It was thus argued that democratic participation should be restricted to the propertied,sinceonlytheyhaveaninterestin maintainingtherighttoprivatepropertywhich issocriticalforeconomicgrowth.Socialists,by contrast,sawdemocracybyuniversalsuffrage ascompatiblewitheconomicgrowthprecisely because they assumed it was ‘incompatible with private property’; as Karl Marx put it, a country cannot be both democratic and capitalist

Then what Huntington calls ‘waves of democracy’startedemerginginthefirsthalfof the19 century.Thefirstwave,whichbeganin the1820s,resultedinareformthatentitledall whitemalecitizensoftheUnitedStates(US)to

increasedproductionandtotaloutput. Democracy is efficient in allocating production factors as compared to autocraticsystemsandtotalitarianregimes Democracyprovides‘politicalcapital’inthe formofa‘stockofdemocraticexperiences accumulatedbyacountry’,whichiscritical foreconomicgrowth.

A number of studies that, beginning in the 1960s, empirically examined the link between democracyandeconomicgrowtheithercould not find conclusive evidence linking democracy with growth or found that democracywasahindrancetogrowth Most academic works on the interplay between democracy and economic growth that were publishedbetweenthe1960sand2000sleaned towardstheconclusionthat‘theneteffectof democracy on growth performance crossnationally over the last five decades was negative or null’ There were indeed a few who empirically found a direct link between economic growth and democracy For instance,Acemogluetal.,whostudiedapanel of countries from 1960 to 2010, found that democracy does cause growth and that its effect is significant and sizable The authors maintained that ‘a country that transitions fromnondemocracytodemocracyachieves [7]

leaders always seek and work towards achievingeconomicgrowth

Authoritariansystemscouldbe‘corruptand pronetoextravagantuseofresources’,and in the absence of democratic institutions that constrain them, authoritarian rulers couldturnintolooters

Economicgrowthinauthoritariansystems isoftenvolatileandshort-lived. Citizens are motivated to invest and work when they are guaranteed political participation

Democracy and the developmental state:ThedebateinEthiopia

The issue of whether and how to sequence democracy and economic growth was at the centreofdebateinEthiopiainthe2000s The Ethiopian Peoples’ Revolutionary Democratic Front(EPRDF),thethen-rulingparty,claimed thatpovertywasthemostpressingchallenge thecountryfacedandthatallattentionhadto focusonreducingit Thepartyemulatedthe ChineseCommunistPartyanddeclaredthatit would follow the ‘developmental state paradigm’. This entailed the state’s active involvementintheeconomicsectoruntilthe economywastransformedfromanagricultural basetoanindustrialone

[15]

MelesZenawi,thethenPrimeMinister,claimed thatthereisnodirectrelationshipbetween

democratise. Under its rule, the country’s economy indeed saw successive double-digit growth for about 15 years. The party used economic growth to justify its authoritarian rule However,thisdidnotlastlong Beginning in 2015, the EPRDF’s rule was faced with unprecedented public protests that went on unabatedforclosetothreeyearsandescalated into violent inter-ethnic conflict This led to divisionswithintheEPRDF,theresignationof

economicbenefitsceasetoflow,theregime’s outcome-legitimacy falters and there is no input-legitimacy(elections)tosustainit

InAfrica,theabsenceoftheruleoflawandthe lack of democratic accountability are negatively linked to economic development Withinthepervasiveethosofthepatrimonial state, and in the absence of democratic restrainingmeasures,thegovernmentbythe people becomes the government for those electedtooffice SouthAfricaduringtheZuma yearsisaprimeexample

Evenwhereeconomicdevelopmentis positivelylinkedtodemocracy,itis hardlyeverinclusive:mostoften, inequalityincreases

A core element of liberal democracies is the protectionofprivateproperty,thecornerstone

Ebrahim Fakir

‘democracy’ itself needs to be fractured into its constituent pieces, since it too comprises many different variables Even if we are merely interested in the relationship (correlation) between one thing (economic growth/economic development/development)

p p incorporatesbasiccivilandpoliticalfreedoms and relates to economic, educational, social, andculturalopportunitiesandtheiravailability and access, such that they contribute to the generalwell-beingofthepopulationatlarge Inherent in this idea is the notion that some kindofdemocracywouldbenecessary–and indeedrequired–foraccesstoopportunityto leadtoincreasingthegeneralwell-beingofa population So, democracy is required for claim-making (re-distribution), for accessing opportunity, and for some element of influence.Butitoughtalsotobeobviousthat ‘democracy’mightenabletheadvancementof theverywell-off,leavingbehindthelesswellofforthosewhoarelesswellorganised

On the question of democracy, it would be useful to bear in mind a distinction between fourbroadaspectsofdemocracy Onerelates to basic minimum civil and political (and, increasingly,socio-economic)rightsenjoyedby citizens; another, to procedures of accountability in the management and administrationofauthorityunderasetofrules; another, to periodic exercises in inclusive, broad-basedelectoralrepresentativeness;and, finally,somelevelof‘participatory’agencythat enables influence, lobbying and advocacy These aspects of democracy have different emphases in different democracies On the otherhand,afewauthoritariancountriesmay displaysomedegreeofadministrative

unwarranted welfare transfers, and special interestdemandsthatmayhamperlong-term investment and growth Conversely, authoritarian rulers who have the capacity to resist such pressures may instead be selfaggrandising,plunderingtheresourcesofthe economy,whiletheSouthAfricancaseshows that democracies that facilitate some sort of capture (and all democracies do) can enable corruption of a kind that facilitates inflated costs, superfluous expenditure, or simple plunder In fact, historically, authoritarian regimescomeindifferentkinds,somederiving their legitimacy from providing order and stability(likeSingapore)andothersfromrapid growth(likeSouthKorea).Ontheotherhand, economicgrowthandeconomicdevelopment throughdiversificationmayflourishwithouta great amount of distributionary benefit, fuellinggreaterinequality

Whatmattersarethefollowing:

High levels of state capacity (regulatory, technical,administrativeandmanagement, extractive and enforcement) and a regulatory regime incentivising the good anddisincentivisingthebad Democracyasasocialandpoliticalpractice for citizen agency for collective action (demand,claim-making,influence) Democracy as a form of exercise of authority(limitsandrestraintsontheuseof power and authority, oversight and accountability)

Through the Looking Glass and Back: Conversations about the Future of Democracy and Democracy for the Future

In recent years, the concept ‘future generations’hasbecomeanevermorepopular discussion point, but its intersection with democracy has been critically assessed by politicaltheoristsforsometime Someofthe viewsthatmayguidefurtherdiscussionsabout democracyasitoughttoengage(theinterests of) future generations and serve such distant generations(ornot)includethefollowing:

‘Assuming that democratic inclusion is conceptualised in legal terms, the representation of future generations is consistent with democracy only to the extentthattheyarelikelytobeboundby the decisions made today … (F)uture generationsarenotboundbythedecisions made today Thus, it follows that representing the interests of future generations in political decisions is not consistentwithsecuringdemocracyforthe living generation The intergenerational problem is therefore one where the demands of justice and democracy may conflict’[4]

Arguments are going up for so-called ‘genuine’ representation of future generations. The counterargument is that these overlook the democratic costs of such representation (for example, violation of political equality, risk of the distortion of deliberation, and undermining autonomy) and seem to ignore the alternative of considering the interests of future generations within current democracy

‘Whether future generations should be granteda“voice”inthedemocraticprocess or not is intimately associated with the broader question concerning the basis for democraticinclusioningeneral Inpractice, no democratic nation extends the legal right to vote and to be represented by political institutions to everyone. Children, residentaliens,prisonersandthementally disabledarerarelyifeverincluded.Less

‘What really matters in terms of the democratic ideal is to ensure an impartial deliberation which takes the interests of all affected parties sufficiently into account.’[6]

‘If future generations cannot be present now, how can they be represented? Present generations, I suggest, can represent future generations by acting as trustees of the democratic process The general principle of the trustee conception that we need to develop is that present generations should act to protect the democratic process itself over time If we believe that the control that citizens now enjoy is inadequate, we may wish to adopt a more demanding version of the principle It would stipulate that any current political generation should seek, up to the point that control over their own decision-making begins to decrease, to maximize the control that future generations will enjoy. Although this would more reliably overcome the dead hand of past generations, it may also place excessive and unrealistic demands on earlier generations’[7]

Political trust is in crisis globally Still, trust is critical for future-oriented governance For example, if people doubt that a policy for which they themselves would have to pay an immediate price will benefit future generations, they are likely to oppose it.[8]

Afewquestionsmayhavetobeexplored,first, in making sense of the intersection between democracy and future generations, and, secondly,withlocallawandpoliticalcontexts inmindTheseincludethefollowing: Do we sometimes perceive democracy as thepanaceaforallsocietalproblems–real orperceived,existingorexpected? Shouldthepursuitofjusticeinrelationto future generations necessarily mean less democracyforpresentgenerations?

Should the political will of future generations be protected? If yes, through which means and by whom exactly?

What does ‘future-oriented democracy’ look like in the here-and-now? When does ‘the future’ start?

What does ‘intergenerational democracy’ mean and is it possible to achieve it? What about the risk of ‘intertemporal tyranny’ and the potential inability of future generations to ‘reverse the law’ or past decisions? Appetite for the immediate is a natural human condition Democracy is therefore government pro tempore What role do the media and other actors play in changing this sentiment, considering modern-day crises such as global climate change? Who forms part of the ‘trustees’ who hold democratic processes in trust for future generations?

In real terms, how viable are ‘trade unions for future generations’, ‘interinstitutional agreements on future generations’, an ‘ombudsman for future generations’, ‘parliamentary representatives for future generations’ and ‘impact assessment for future generations’, for example?

COMMENT:

cities Since a vast majority of citizens are increasingly residing in urban areas, the representation of present and future generations in South Africa’s democratic governancewouldbeunlikelytoconsiderthe needsandperspectivesofruralcommunities. [13]

Ruralareasareoftencharacterisedbypoverty, unemployment,andlimitedaccesstoservices, while urban areas are hubs of economic activity,innovation,andculturaldiversity More profoundly, in rural areas participation in democratic processes, including elections, is often very low. However, rural areas also provide essential ecosystem services, such as foodproduction,watersupply,andbiodiversity conservation, which are critical for urban sustainability [14] [15]

The future of democracy in South Africa depends on the ability of the government to address the challenges of rural-urban interdependency This requires a more integrated approach to development that recognisestheinterconnectionsbetweenrural

I would like first to present a few thoughts assessing development and democracy globally, and then propose some ideas for discussion

7. There is also abundant evidence that the international human rights framework is not delivering on its promises Resolutions of the UN General Assembly are not binding, and resolutions of the Security Council can be blockedbythevetopowers Actorsthreatening global peace, disregarding people’s right to self-determination,andviolatinghumanrights arethususuallynotheldaccountable

8 The right to development is not recognised as a global (human) right. The holder of the rightand,moreimportantly,theduty-dearerof such right have remained undetermined The scopeoftherightanditscorrespondingduties hasalsonotbeenclarifiedyet

9 At the World Conference Against Racism, RacialDiscrimination,XenophobiaandRelated Intolerance in 2001, it was recognised that colonialismwasacrimeagainsthumanityand that its effects persist and continue to contribute to lasting social and economic inequalities, mostly affecting Africans and peopleofAfricandescent,aswellaspeopleof Asian descent and indigenous peoples The Declarationcallsforanactionplan,warning,in vain,that‘thebesttoolsareonlyofvalueifthey areputtouse’

10 The international discourse on development, including in the field of sustainable development goals, is based on a specificunderstandingofdevelopmentwhich

15 Democraciesarecharacterisedbythefact that the people govern themselves, either directly or indirectly Democratic governance anditscoreprincipleof‘oneperson,onevote’ henceguaranteetheidentityofthosewhorule andthosewhoareruled Theconceptisbased on the idea that all human beings have an inherentandequalrighttoself-determinetheir lives and an inherent and equal right to codeterminetheworldtheylivein Democracies shield human beings from heteronomy and other forms of domination in which other actorsdecideuponaperson’slifeordetermine theworldthepersonlivesin

16 Democraticprinciplesempowerallpeoples togovernthemselves Peoplehavetherightto determine (challenge and amend) the rules that are binding on them Democracy must existwhereverrulesaremade,andwhoeveris bound by the rules, constitutes a people For local rules, the local population must be consideredapeople;forglobalrules,theglobal population

17 Theminimumrequirementforasystemto be democratic is that those who are being ruledchosethosewhoruleingenuineperiodic elections. To comply with such requirement, international law that has direct effects on people must be made by an international parliament composed of directly elected representatives Asindomesticlaw,theroleof theexecutivesmustbelimitedtoexecuting

they are based ‘upon the principle of mutual benefit’ In addition, the norm states that a peoplemay‘innocase bedeprivedofitsown meansofsubsistence’.

25 Human rights and the right to selfdetermination open up many possibilities for refusing to implement unfair economic agreements Intheeventofaconflictbetween the obligations of UN members under the UN Charter and their obligations under any other international agreement, their obligations undertheUNCharterprevail[2]

26 If development strategies and objectives, which are expressions of a country’s right to self-determination, are demonstrably and significantly impaired by (illegitimate) internationalnorms,theprimacyoftheCharter can be claimed and non-compliance with other norms justified The claim to selfdetermined development then becomes a justiciableright

27 The rule that a state may ‘in no case’ be deprivedofitsownmeansofsubsistenceoffers an argument to challenge debts (and, potentially, treaties) that hamper a country’s capability to offer minimum public services Suchanargumentisvalidonlyifacountryuses its means of subsistence to provide such services

28. The ICESC obliges states to undertake steps,‘individuallyandthroughinternational

to produce new evidence, to co-operate across borders, to build and strengthen (transnational) networks, to raise awareness, to lobby, to negotiate, to agree upon and create alternative discourses and realities, to resist, and to rebel The profiteers of the system are few; those in want of change are many. Genuine democratisation at all tiers is thus a priority. It is best planned under the blue sky.

new trend is appearing, developing and lookingunavoidable,representedbytheuseof ‘constitutionallawoutofthestate’ NGOsand mega international companies, such as the GAFAM(Google,Apple,Facebook,Amazon,and Microsoft),arenowdesigningandusingtheir own constitutional law to rule their relations worldwide, using the means and methods of constitutionallawandadaptingthemtotheir needs

Thisapproachofconstitutionallawoutofthe statecreatesnewchallenges,astheseplayers areasdiverseasstatesanddefendtheirown interests:thisisanothertypeofglobal(non?) democracy. Amongst these non-neutral players,someofthemdefendtheinterestsof poor communities and of disadvantaged people (one can think, for instance, of NGOs involved in environmental protection or indigenous-population rights protection). However, others use their ‘own rules of constitutionallaw’todefendandprotecttheir interests, hoping to bypass state rules they consider as not binding This was recently illustratedbyacourtdecisioninBrazilagainst X(formerlyTwitter),whereajudgeaskedfor

government,taskedwithestablishingasociety

fundamental human rights. Yet many of us continue to find ourselves in gang-ridden, poorly serviced and degrading communities thatforceustoremaininourhomes,orrisk losing our lives as a result of rampant gang violence.Wehavebecomeaccustomedtothis life,tothepointthatgunshotsnolongerfaze us. Many born-frees have lost hope that the situation will ever improve, leading to many checkingoutofdemocracybyrefusingtovote –canyoubemadatus?SouthAfrica,you’ve not done a thing for us, save for selling us hopes and dreams. This cannot be the democracyforwhichyou,ourelders,foughtfor 30 years ago Rather, this is democratic backsliding – a serious threat to our democracy

Forced removals by municipalities now termed ‘unlawful evictions’ are becoming increasinglycommon.

Homelessness is ever increasing, and accessibilitytoaffordablehousing,afarce It is becoming questionable whose laws law-enforcement agencies are enforcing and whether SAPS officials are the perpetrators, rather than preventers, of crime.

Allwhileunemploymentkeepsrising,with university graduates falling into poverty becausetheyarenotbeingabsorbedinto theeconomy

Butmyjourneyisnotjustaboutthephysical distance I have travelled. It is also about the personaljourneyIhavebeenon Igrewupina humblehouseholdinNancefield,Musina,with two brothers, Patrick (elder) and Peter (twin), where I was raised by a single mother, Ms Tambu Selinah Sibanda, who worked as a domestichelperuntilshequitherjobdueto illness.Iknewthenthateducationwasthekey tounlockingabetterfuture AndsoIpursued mydreams,andIamproudtosaythatafter obtainingmyLLBandtwoLLMdegrees,Ithen graduated with my PhD in Law from Wits Universityon8July2024.

Hoërskool Jan van Riebeeck, the neighbourhood Afrikaans school which I attendedyearsbefore Itwas27April1994,the day of the election, and the school was a pollingstation Onanovercastdaywithaslight drizzle, voters patiently huddled under their umbrellas Ihadtakenmyparentstovote They recognised some of the congregation members Alsomembersoftheprayergroup The previous two weeks they had prayed beseechingly for the Lord’s blessing of the elections

Asthequeueslowlycreptforward,Ithought:

A number of breakdowns in attempts to (re)constitute the country later, and having obtainedmyfirsttwodegrees,Iwasworking on27April1994asanelectionofficeratarural votingstationoutsideofPretoria.Again,vivid memories of a sunny autumn day and seemingly endless lines of people, most of them voting for the first time in their lives. I remembertheuncanninessofitall–‘hoping for the best but expecting the worse’, the soundtrackthathadreplacedtheoptimismof JohannesKerkorrel’s‘GeejouhartvirHillbrow’ (‘GiveyourhearttoHillbrow’) Ofcourse,there was much hope, and holding on to the possibilityofrealchange.

raced as I stepped inside At the desk, I scribbled my name on the voters’ list It was clearthatIwastrespassinginaworldmeant foradults.ThenIenteredthevotingroom.It wassupposedtobeempty,aprivatespacefor conscienceandchoice.Instead,Ifoundtwo

Cornell D Beyond accommodation: Ethical feminism, deconstruction and the law

Rowmann and Littlefield (1999) at xv

Cornell D Legacies of dignity: Between women and generations Palgrave (2002) at xvi

See Cornell (1999) at xx

See Cornell (1999) at xx

Young IM Justice and the politics of difference

Princeton University Press (1990) at 92

Young (1990) at 94

Young (1990) at 94

Young (1990) at 95

Young (1990) at 95

Young (1990) at 96

Young (1990) at 96

Young (1990) at 97

Young (1990) at 97

Young (1990) at 97

Derrida J On cosmopolitanism and forgiveness

Routledge (1997)

Thomson A Deconstruction and democracy:

Derrida's politics of friendship New York: Continuum (2005)

Derrida J Rogues: Two essays on reason

Stanford: Stanford University Press (2005)

Thompson (2005)

Derrida (1997) at 3.

Derrida (1997) at 3.

Derrida (1997) at 4.

Derrida (1997) at 5.

Derrida (1997) at 6.

Derrida (1997) at 8

Derrida (1997) at 16

Derrida (1997) at 16

Derrida (1997) at 17

Derrida (1997) at 21–22

Brown W & Wade F ‘The violent exhaustion of liberal democracy’ Boston 50 Review (21 October 2024) available at https://wwwbostonreviewnet/articles/theviolent-exhaustion-of-liberal-democracy/ (accessed 19 August 2025)

Brown & Wade (2024)

Brown & Wade (2024)

Brown & Wade (2024)

Brown & Wade (2024)

Klare K ‘Self-realisation, human rights, and separation of powers: A democracy-seeking approach’ (2015) 26 Stellenbosch Law Review

Cornell (2002).

Brand D & De Villiers I ‘Street-based people and the right not to lose one’s home’ in De Beer S & Valley R (eds) Facing homelessness: Finding inclusionary collaborative solutions AOSIS (2021) 95

Przeworski A & Limongi F ‘Political regimes and economic growth’ (1993) 7(3) Journal of Economic Perspective 51

Huntington defines a ‘wave of democracy’ as the transition from autocracy to democracy by a group or cluster of nations, regardless of the cause underpinning why those nations chose to transition to democracy According to Huntington, there were three waves of democracy Seva Gunitsky considers the causes of democratic transitions – ‘simple contagion’ (both vertical and horizontal) or ‘emulation’ (both horizontal and vertical) – and claims there are 13 waves of democracy

Ripsman NM ‘Peacemaking and democratic peace theory’ (2007) 3(1) Democracy and Security 89; Placek K ‘The democratic peace theory’ (18 February 2012) E-International Relations available at https://wwweir.info/2012/02/18/the-democratic-peace-theory (accessed 1 August 2025).

Burchi F ‘Democracy, institutions and famines in developing and emerging countries’ (2011) 32(1) Canadian Journal of Development Studies 17. Riley J ‘Authoritarian institutions and economic growth: The case of Singapore’ (Master’s thesis, Lund University 2018)

Riley (2018) at 14

Doucouliagos H & Ulubasoglu MA ‘Democracy and economic growth: A meta-analysis’ (2008) 52(1) American Journal of Political Science 61

Gerring J, Bond P, Barndt W & Moreno C ‘Democracy and growth: A historical perspective’ (2005) 57(3) World Politics 323

Acemoglu D et al ‘Democracy does cause growth’ (2019) 127(1) Journal of Political Economy 47

Economic development is a process requiring huge investments in personnel and materials Such investments imply cuts in current consumption that would be painful at the low levels of living standards found in almost all developing societies Governments must thus resort to strong measures and enforce them

with an iron fist in order to marshal the surplus needed for investment. If such measures were put to popular vote they, would surely be defeated. No party can hope for democratic election on a platform of current sacrifices for a bright future

Riley (2018)

Acemoglu et al (2019)

Funke M, Schularick M & Trebesch C ‘Populist leaders and the economy’ (2013) 113(12) American Economic Review 3249

Funke, Schularick & Trebesch (2013)

This section is adapted from the author’s previous work, Ayele Z ‘Constitutionalism and electoral authoritarianism in Ethiopia: From EPRDF to EPP’ in Fombad CM & Steytler N (eds) Stellenbosch handbooks in African constitutional law: Democracy, elections, and constitutionalism in Africa Oxford University Press (2021) 186

World Economic Forum ‘Meles Zenawi: Accelerating infrastructure investments | Africa 2012’ available at https://wwwyoutubecom/watch?

v= mkHjtpGPaY (accessed 1 August 2025)

Zenawi M ‘African development: Dead ends and new beginnings’ (Master’s thesis, Erasmus University 2006)

De Waal A ‘Review article: The theory and practice of Meles Zenawi’ (2012) 112(446) African Affairs 148.

Fiseha A ‘Development with or without freedom’ in Brems E, Van der Beken C & Yimer SA (eds) Human rights development: Legal perspectives from and for Ethiopia Brill Nijhoff (2015) 101 De Waal (2012) writes: ‘[T]o those who condemned his measures against the political opposition and civil society organizations, [Meles] demanded to know how they would define democracy and seek a feasible path to it in a political economy dominated by patronage and rent-seeking?’

Tadesse M ‘Meles Zenawi and the Ethiopian state’ (nd) available at http://aigaforumcom/articles/medhaneye-onmeles-zenawi-and-powerpdf (accessed 1 August 2025)

After the character Dr Emmett L Brown in the film Back to the future (1985).

Thompson DF ‘Representing future generations: Political presentism and democratic trusteeship’ (2010) 13(1) Critical Review of International and Political Philosophy 17; Allemano A ‘Future generations as Europe’s democratic blind spot’ 1 2

(20 February 2024) European Democracy Hub available at https://europeandemocracyhub.epd.eu/futuregenerations-as-europes-democratic-blind-spot/ (accessed 1 August 2025); Beckman L ‘Democracy and future generations: Should the unborn have a voice?’ in Merle JC (ed) Spheres of global justice Springer (2013); Beckman L ‘Do global climate change and the interest of future generations have implications for democracy?’ (2008) Environmental Politics 610; Jensen KK ‘Future generations in democracy: Representation or consideration?’ (2015) 6(3) Jurisprudence 535

Brundtland G Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our common future United Nations General Assembly document A/42/427 (1987), Chapter 2

Beckman (2013) at 775

Beckman (2013) at 776–777

Jensen (2015) at 535 (emphasis added) Thompson (2010) at 32

See Fairbrother M et al ‘Governing for future generations: How political trust shapes attitudes towards climate and debt policies’ (2021) 3 Frontiers in Political Science 3:656053 Jensen (2015) 537

Statistics South Africa ‘South Africa: Urbanization from 2009 to 2019’ (2020).

Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs ‘South Africa’s national urban development policy – The IUDF: An overview’ (2020) at 2.

Gardner D & Graham N Analysis of the Human Settlement Programme and the subsidy instruments Pretoria: National Treasury (2017) at 46

Hovik S, Legard S & Bertelsen IM ‘Area-based initiatives and urban democracy’ (2024) 144

Cities 1

Mudau P ‘Promoting civic and voter education through the use of technological systems during the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa’ (2022) 22

African Human Rights Law Journal 108

Gebre T & Gebremedhin B ‘The mutual benefits of promoting rural-urban interdependence through linked ecosystem services’ (2019) 20

Global Ecology and Conversations 1

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICPCR), art 1, para 1; International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESC), art 1, para 1 UN Charter, art 103