Index -Connecting imagined sides of the Mediterranean 2

-Mapping lost homes to harbor: 5 archiving for a new Syria

-Excerpt making stories from interviews by Sammy Zarka 7

Index -Connecting imagined sides of the Mediterranean 2

-Mapping lost homes to harbor: 5 archiving for a new Syria

-Excerpt making stories from interviews by Sammy Zarka 7

Fragmented scenes have long been used to pave the floors of Mediterranean homes. Mosaic tesserae, the small square tiles that were used to construct and assemble such scenes, aspired to explain the mysteries of both human and natural life through the depiction of mythological images and geometric patterns signifying specific symbolic meanings.

Syria is home to some of the world's oldest mosaics, dating back to as early as1500 BC Thirteen years into the ongoing war, millions of Syrians are today scattered across the globe, carrying and sharing their craft with their new communities. In ancient times, during the first five centuries AD, a multitude of Syrian artisans traveled the Mediterranean, sharing their skills and contributing to varied cultural and artistic scenes. Highlighting how experiences of displacement are shared across millennia, the exhibition also points to resilience of creativity of these communities.

What remains of Villa Gallo Romaine in Loupian is an epitome of how displacement contributed to building homes around the Mediterranean Both the technique of mosaic bedding and the way the topics are pictured point to the identity of the Syrian mosaic makers who brought with them their craftsmanship to France; working on several mosaics of villas in the region.

Villa gallo Romaine’s initial construction dates back to the second century. A time that witnessed a rise in identity awareness, among different populations, on both sides of the empire; the Gaul in the west and Palmyra in the east. In a relatively short time, Palmyra grew as a glamorous commercial cultural center, an oasis in the Syrian desert, classical in its architectural elements yet oriental in its details A Roman body with an Arab soul. Exposing in its details a cultural mix of Greco-Roman and Semitic local craft and belief. Palmyran funerary busts embody this reflection, following the classical overall tradition yet paying significant attention to details of cloth folds, jewelry distinction and hair styles

3

Throughout the past decade a number of studies on Palmyrene polychromy investigate funerary portraits from Palmyra. Particularly, the collection of the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, reveal through imaging techniques the lost color of these displaced faces. Lapis lazuli, pyromorphite, mimetite and red ochre are among the pigments found in their limestone carvings.

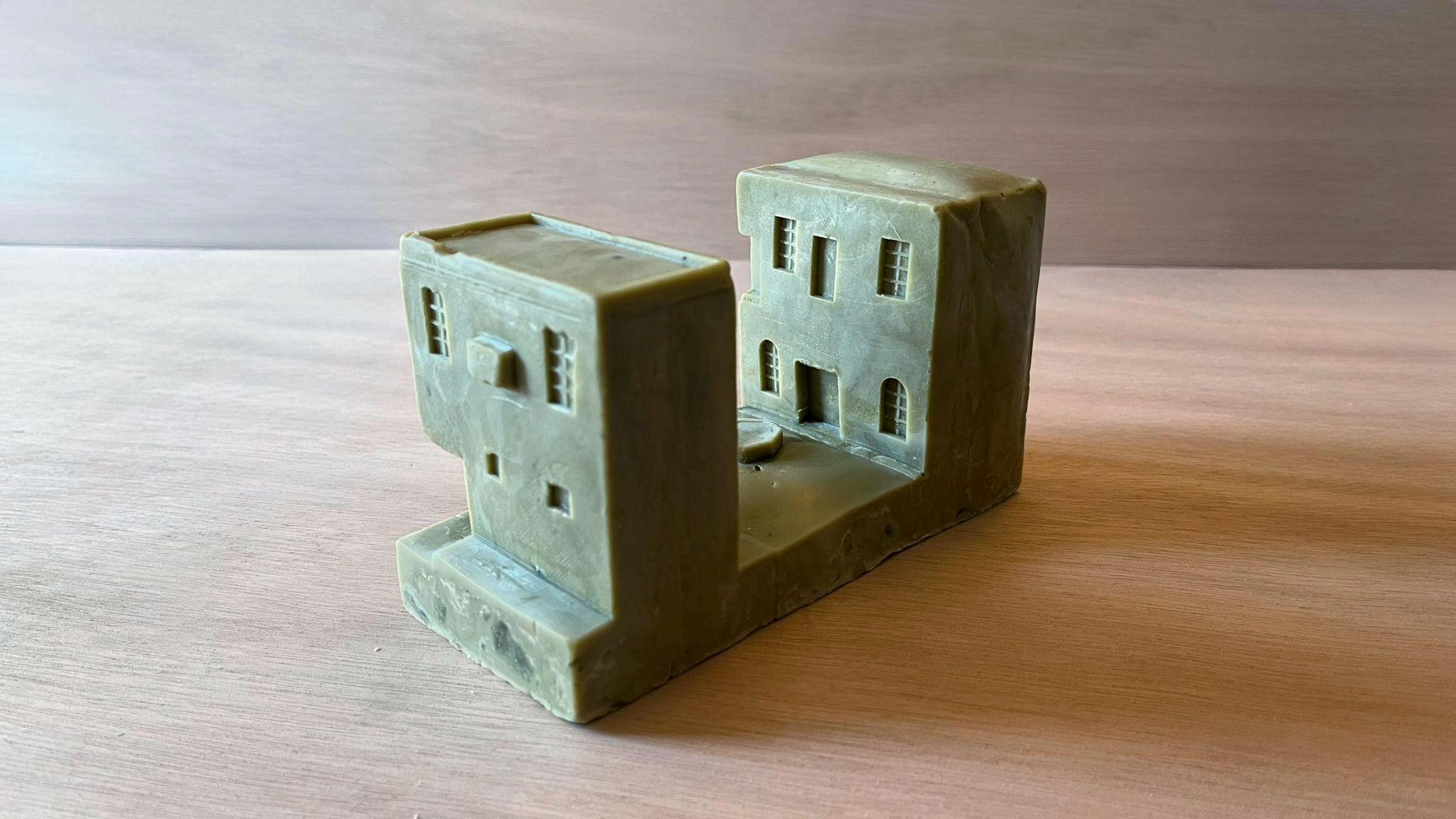

Roaming the widely destroyed Syrian suburbs, colorful intact plastic flowers pierce through the gray rubble Now plastic waste, once a radiant ornamental element in living rooms and hallways. In a syncretic approach and with the use of 3D scanning, the artist reproduces lost and scattered Palmyran reliefs using recycled plastic from war debris. Cracks in fired clay bricks reveal vibrant plastic petals, infusing color into the copied faces that once adorned the towers of the Palmyran necropolis Now looted and largely destroyed.

The late 19th century, marked by intense colonial and imperial activity, saw Western collectors and institutions frequently removing cultural artifacts from their countries of origin A notable example involves the hundreds of Syrian faces from Palmyra shipped to Copenhagen, creating the largest repository of Palmyran artifacts outside of Syria. The absurdity of this custodian relationship becomes even clearer when considering Denmark's present-day approach to Syrian refugees, which has attracted substantial international criticism The Danish government has begun revoking the residence permits of Syrians, potentially endangering the lives of about 20,000 individuals a policy viewed as a violation of the non-refoulement principle of the 1951 Refugee Convention, a fundamental aspect of international law. This action positions Denmark as the first European country to move towards such a measure

The study of archaeology is intrinsically multidisciplinary, as it provides valuable insight to reimagine intertwined layers of history that shape our lives today. Viewing archeology purely as a science prevents us from instrumentalizing it to justify narrow-minded narratives or territorial claims based solely on the imagined contexts of physical artifacts 4

Today, selective narratives continue to cherry-pick data to support specific political and economic ideals; effectively manufacturing consent for agendas that are responsible for the large-scale displacement and dispossession of millions annually This demonstrates a continuing legacy of influence and interference rooted in historical precedents.

Providing contemporary context to the Syrian mosaics at the Villa Gallo-Romaine in Loupian aims at unveiling these dynamics, offering a lens through which to observe the intertwined legacies of cultural heritage and human rights issues

While millions of Syrians leave their homes to embark on the journey of creating new futures, a new Syria is already being conceived; as the daughter of the memories of their lost place of origin, of the trauma of displacement, of the culture-clash, the hyper-adaptation and their will to survive.

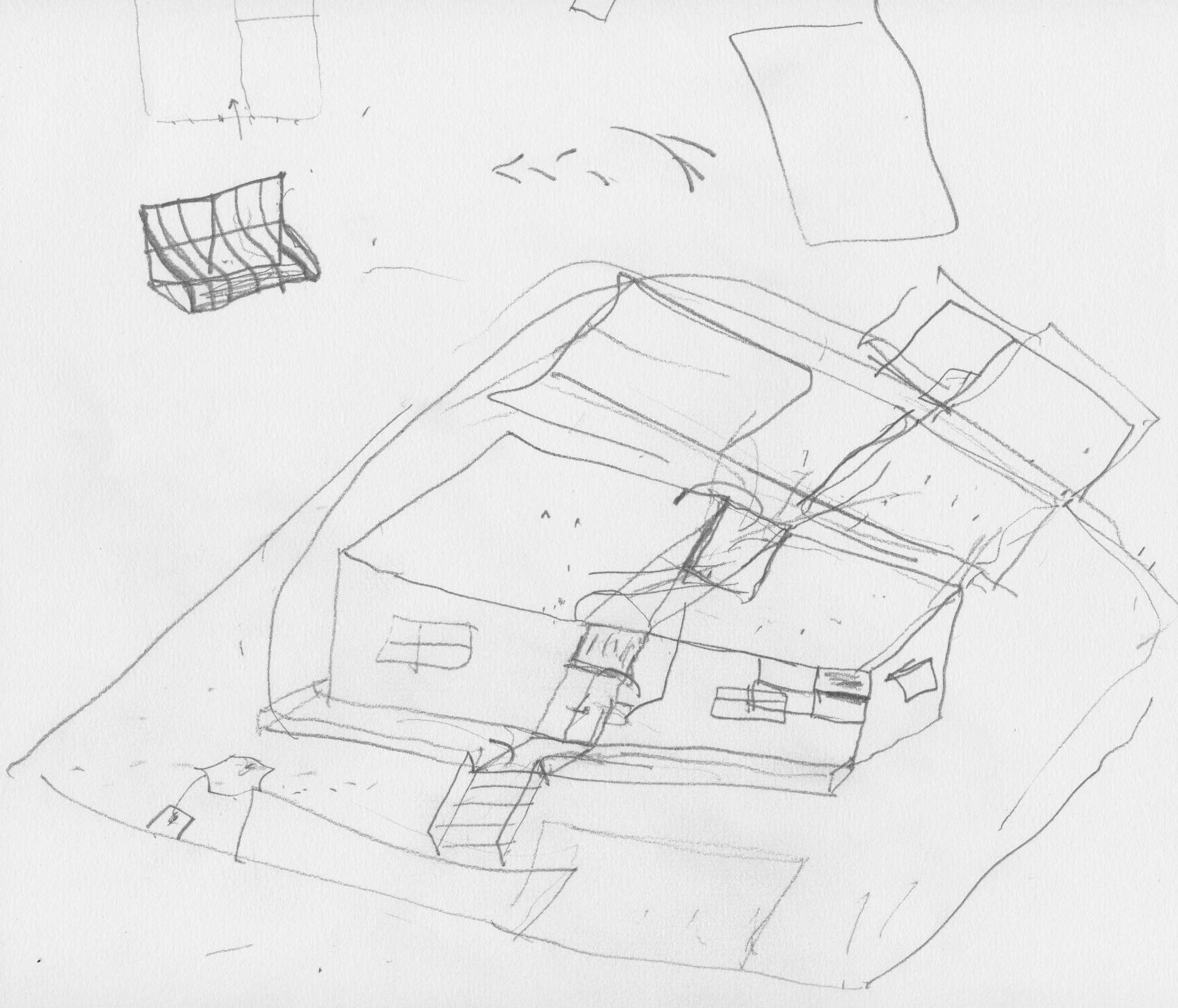

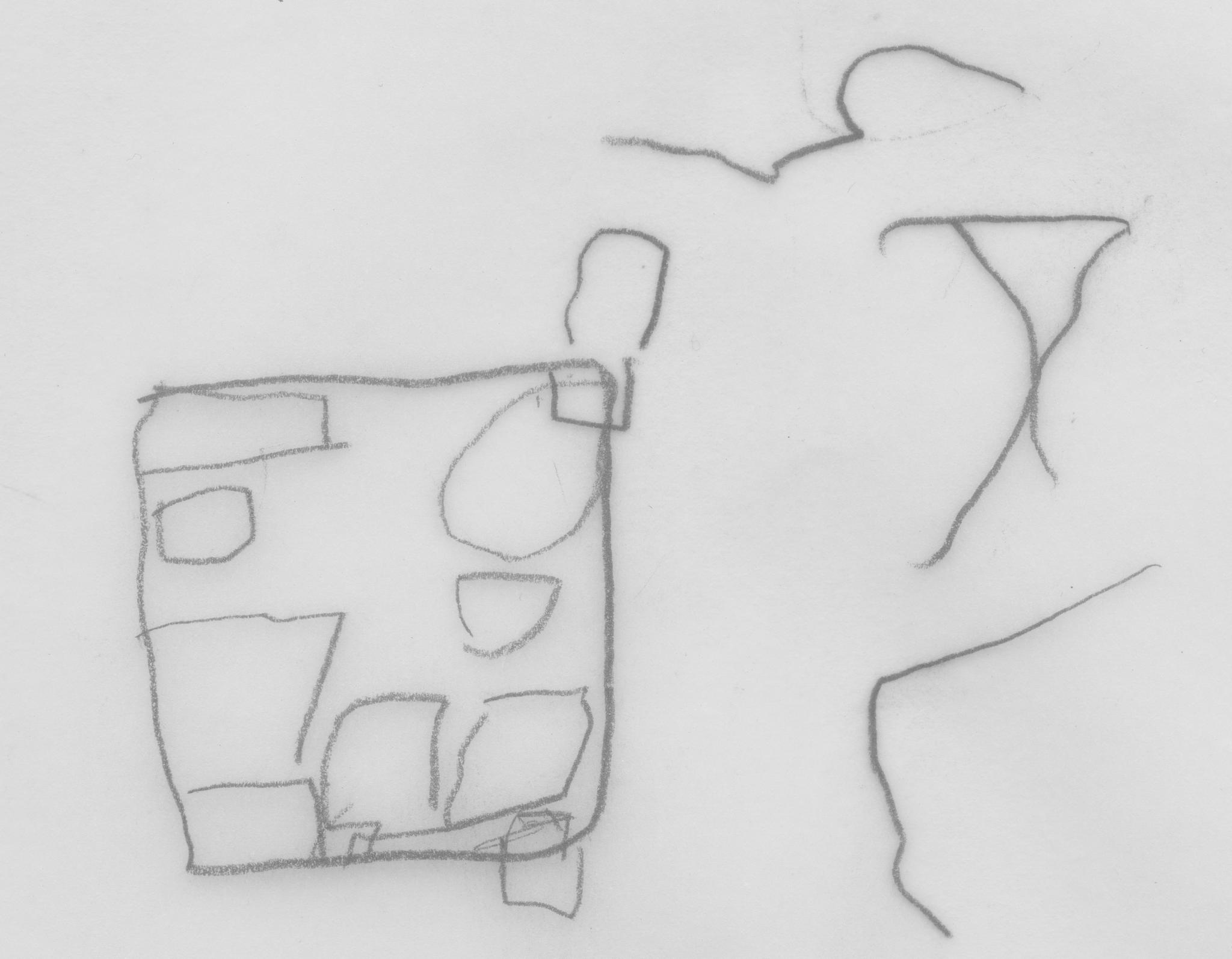

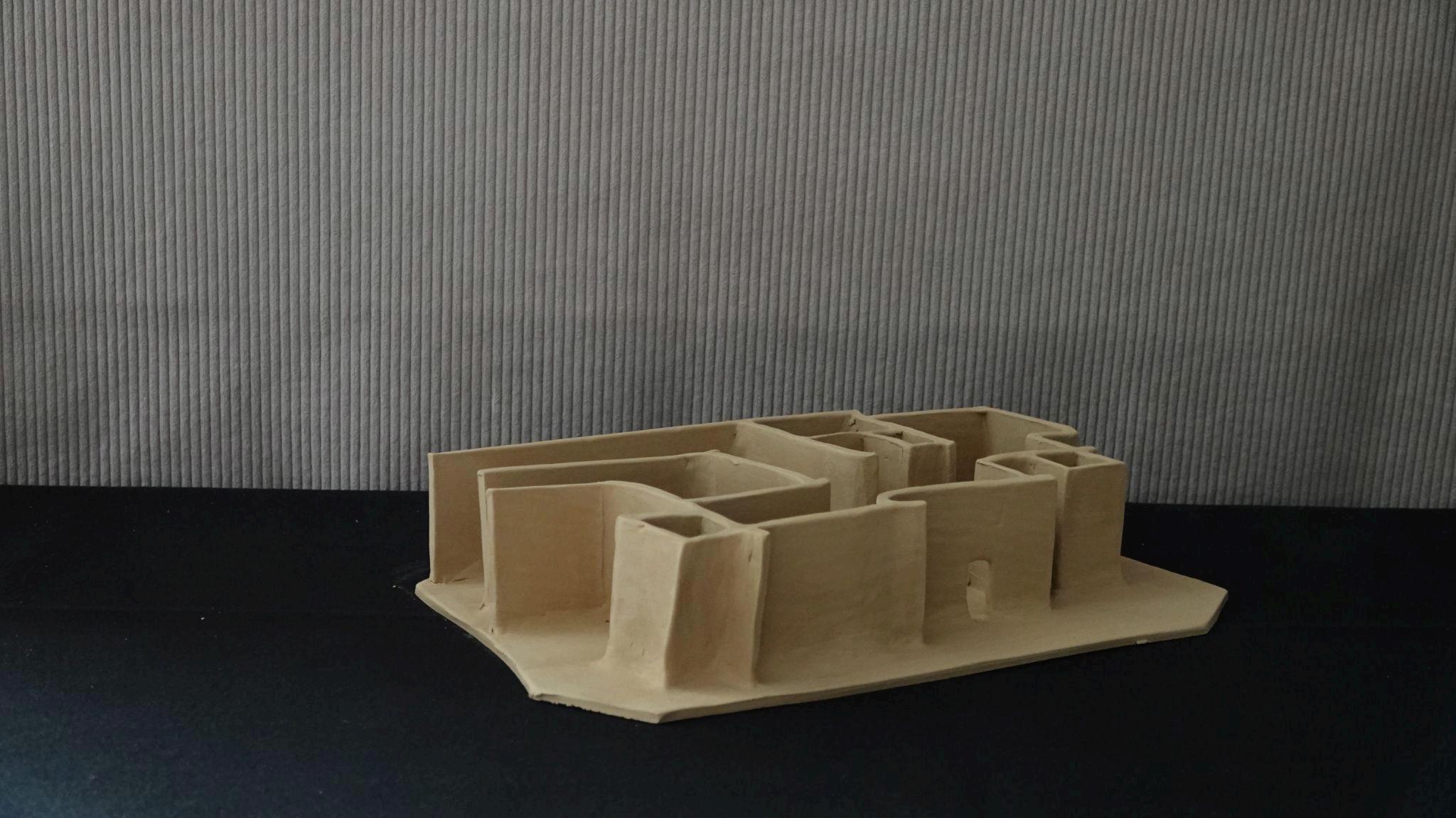

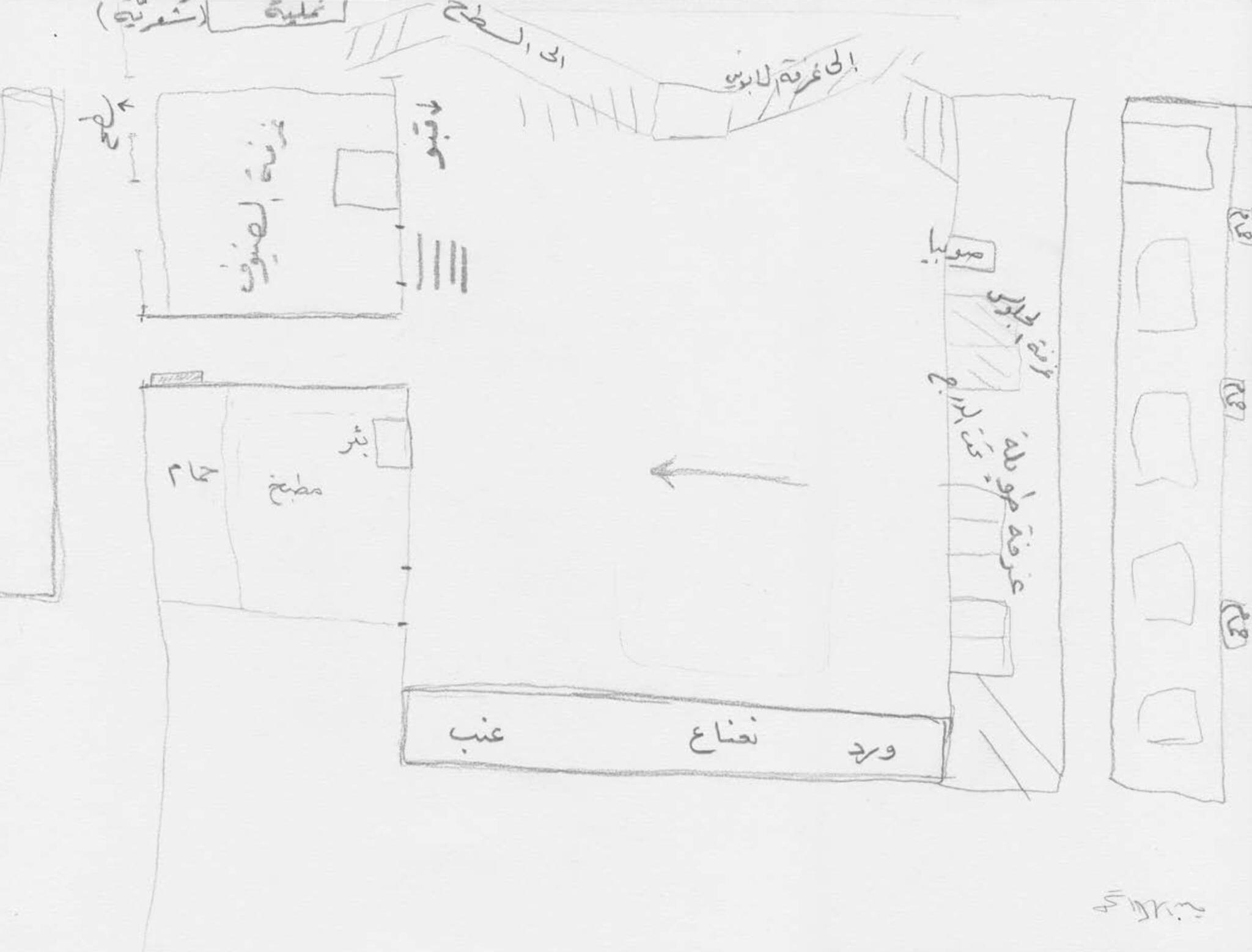

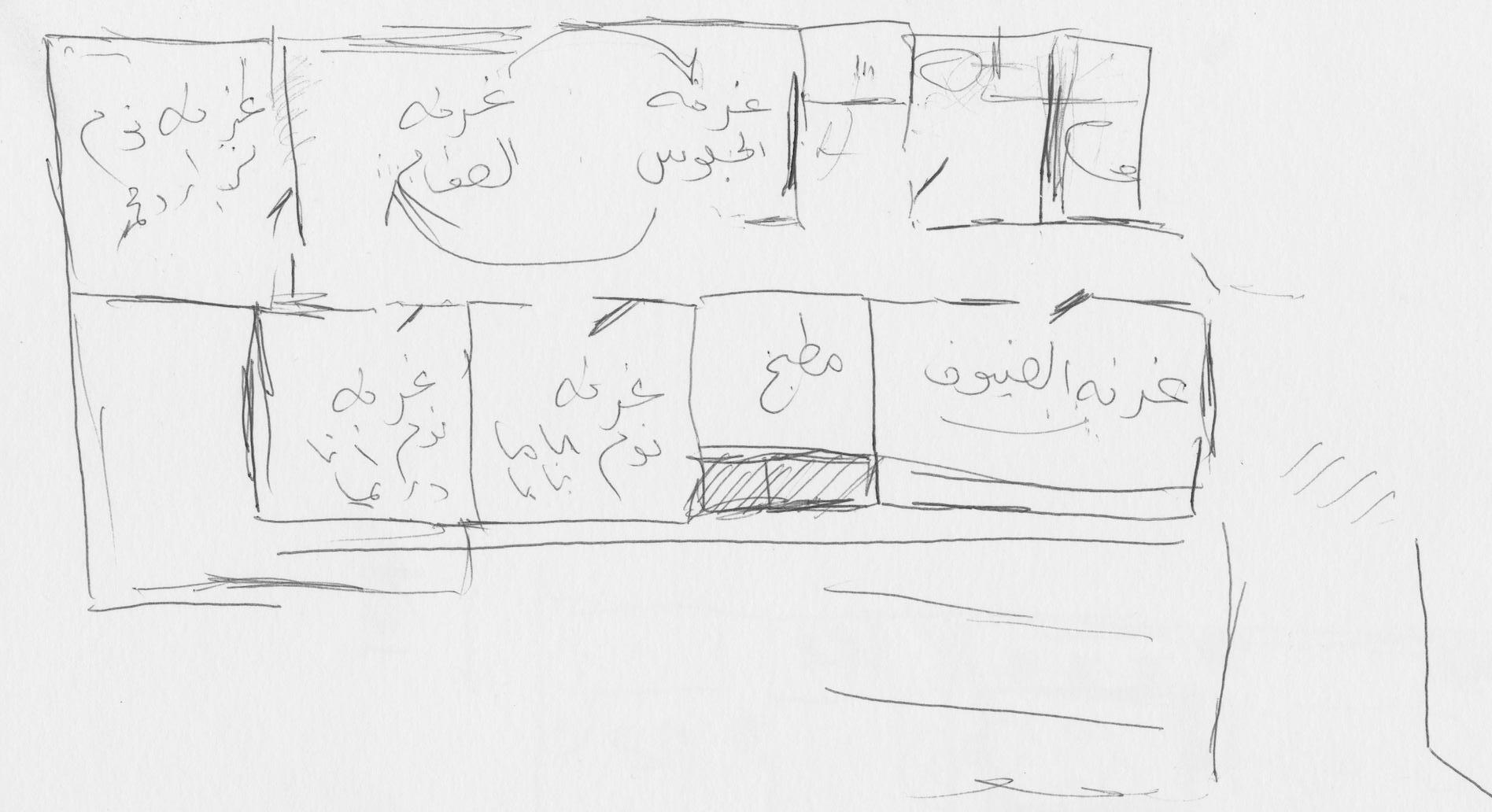

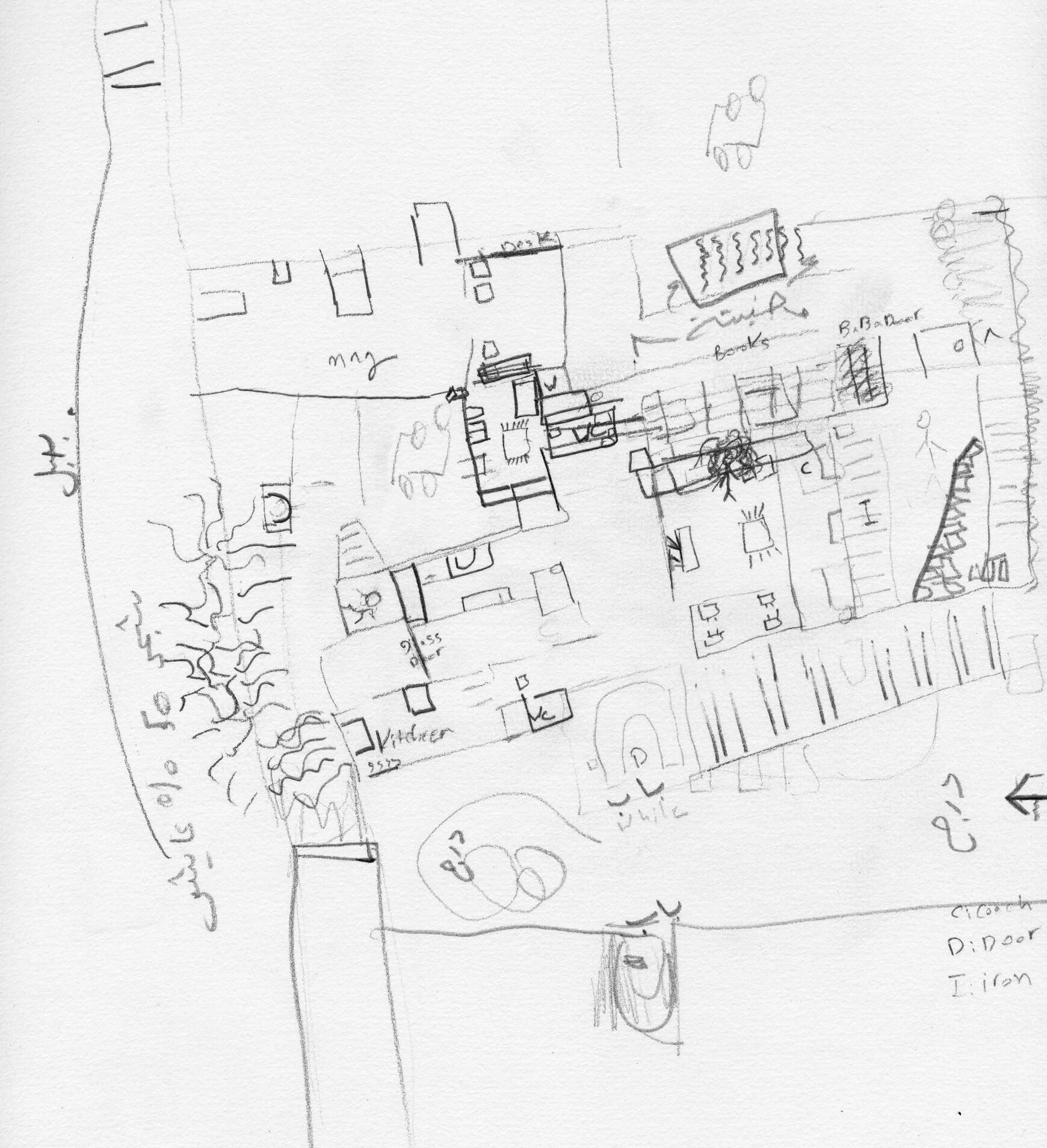

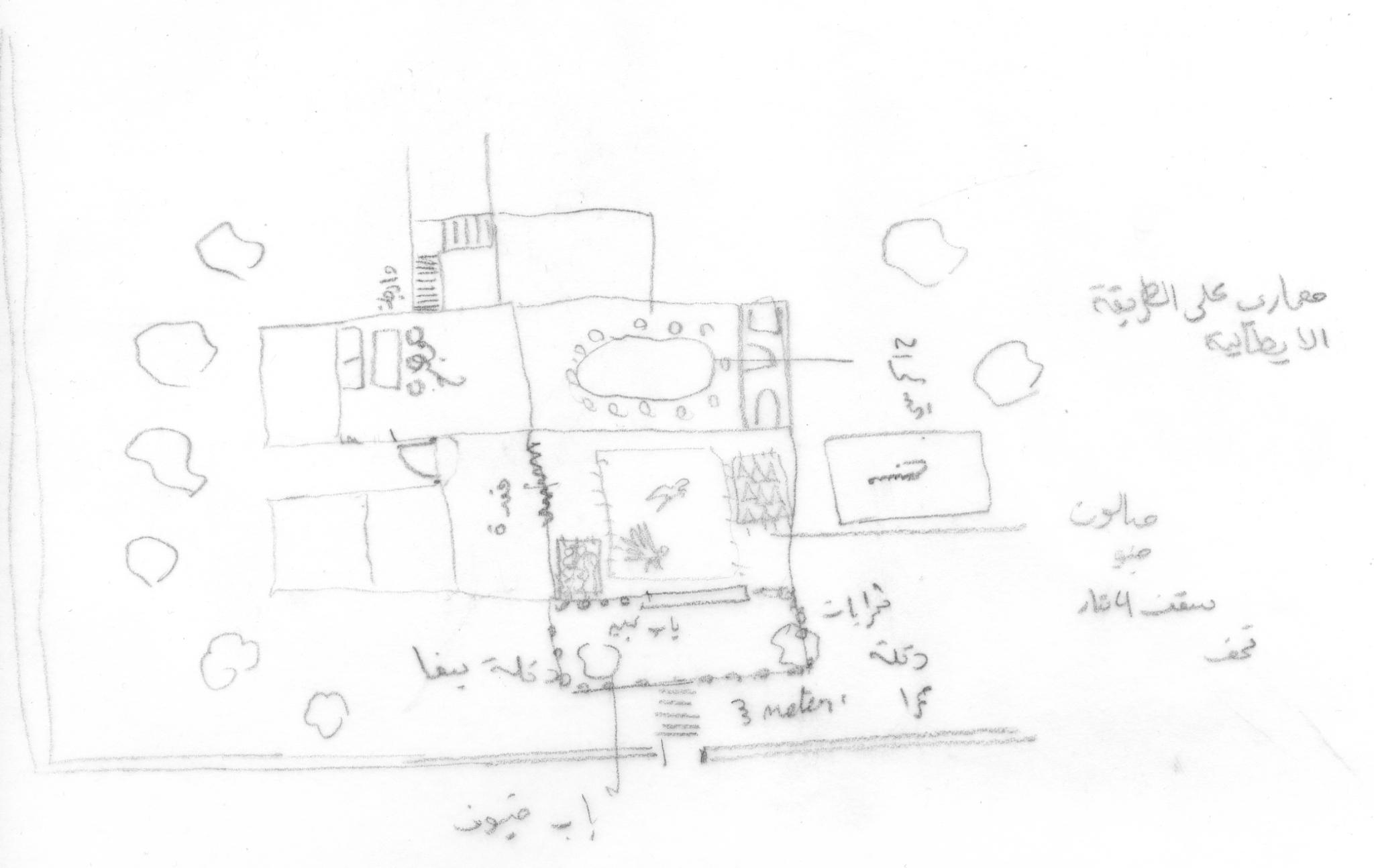

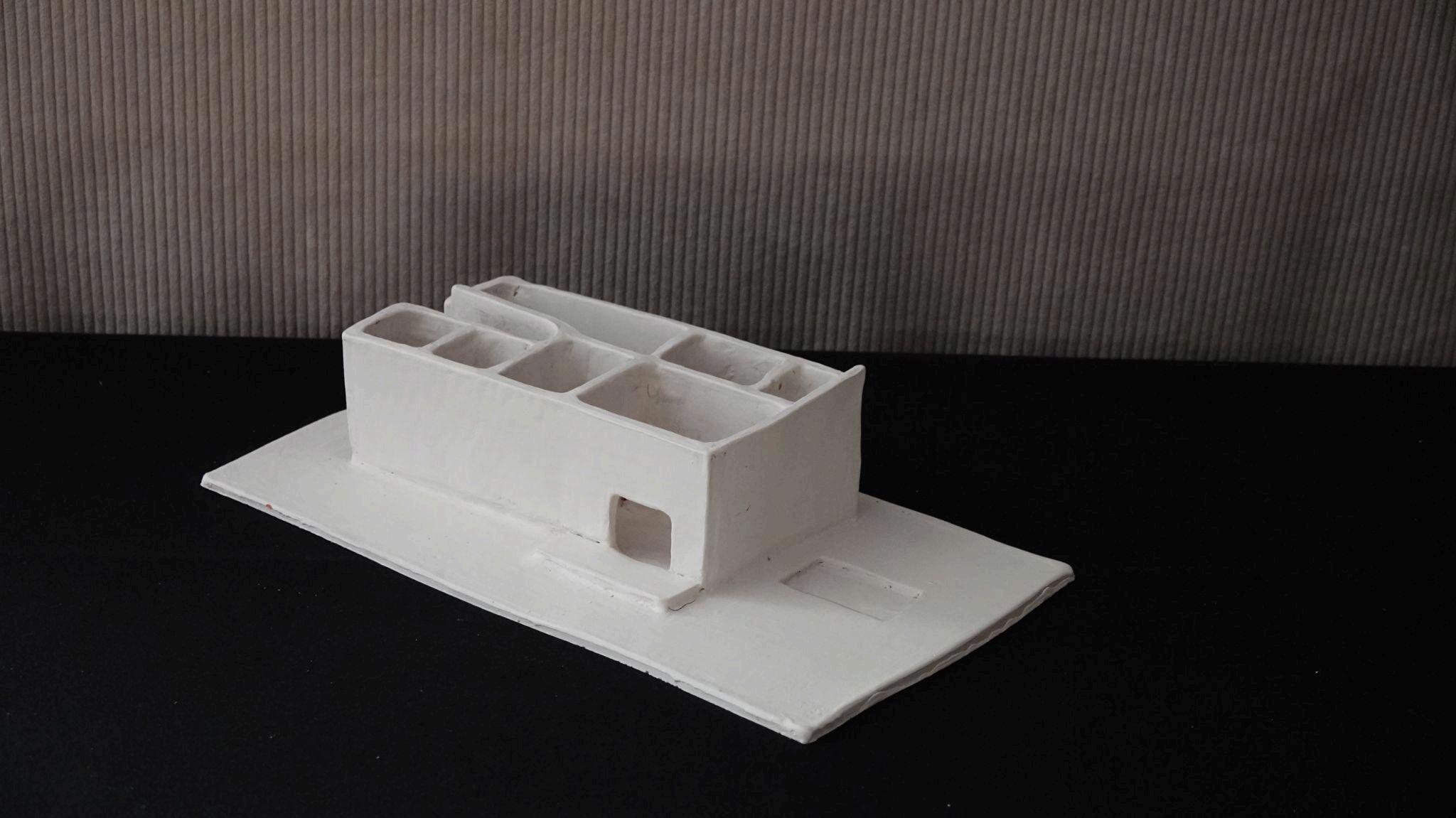

The urge to archive memories of lost homes stems from a need to provide a blueprint of how the memory of home transforms as the displaced processes new environments. This juncture in the exhibition presents a user perception survey where I interviewed some of the Syrians who left their homes during the conflict It encourages them to tell stories of their lost homes by means of drawing maps which in turn begin the dialogue of comparing their past and current homes.

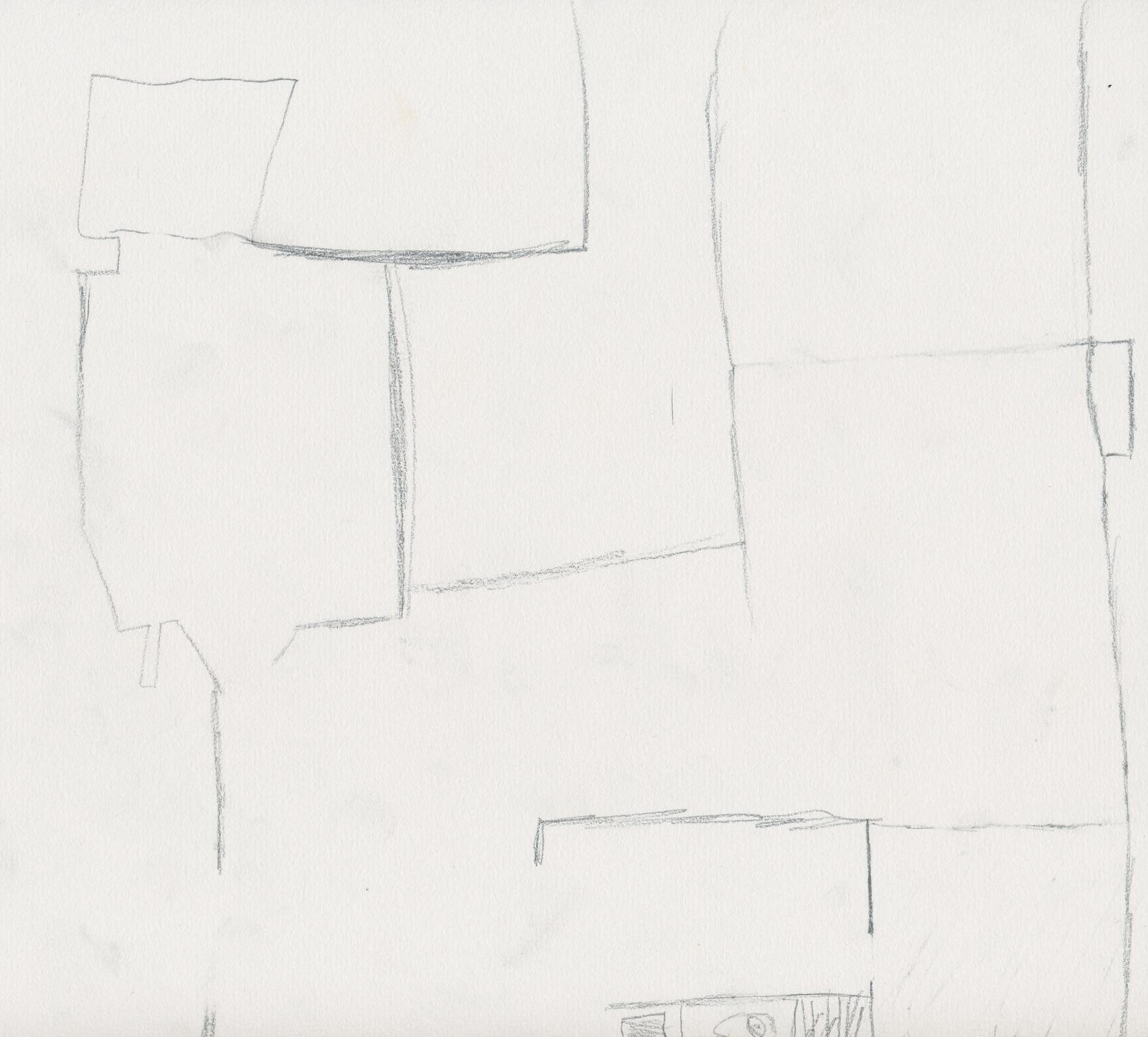

The general assumption is that maps are a subjective two-dimensional representation of reality. However, mapping the past is an attempt to understand the transformation occurring in our identity today. Past homes live on as memories of places which belong to individuals who inevitably question their identity as they go inhabiting new homes in new countries. Their drawings for me do not display how their home actually was but rather how its loss is experienced This is why rather than pointing to actual places the maps become a tool to reveal and explore the transforming identity of the displaced.

As such, new questions begin to arise Can the mapping of homes from afar help with processing loss? Could it sustain a grass-roots method in narrating and redrawing Syria's past and future? The stories collected for this exhibition reflect on the power of collective memory; discovering how scattered individual trajectories uncovers a fragmented, unique image of Syria’s past and present.

As an architect it is humbling to see - through these stories - how instinctive homemaking is for all people. Abu Mulham tells me as he draws the plan of his home how he contemplated and then oriented the kitchen to include a storage for the goods he produced from his backyard trees; on the land that once was the family farm. Atef tells me, as he draws his map, the emphasis he placed on the traditional choices he made as he designed and built his home with a courtyard and recollects a full set of Damascus mother of pearl furniture.

In the process of tapping into the rich waters of mapping one’s home; it becomes apparent how we ourselves are woven into the very fabric of these built spaces and what it, in turn, takes to create a new home away from home.

Throughout the 90s I grew up in a small neighborhood in the mountainous area of Barzeh in Damascus. Our home was in a four-story building, one of ten identical structures surrounding a park where I played with the other children Today marks a decade since I left that neighborhood; but I still bring my worries and new friends there in my daily dreams, revisiting that familiar context where past and present meet

Each memory of Damascus I know seems to drift into the next, yet none truly vanish There's the Damascus where I first found my footing as a high school student in the old city, the Damascus of my childhood, the Damascus I reluctantly left at twenty, the Damascus I searched for years later only to find it had changed, the Damascus I explored with one person and then revisited with another and the Damascus that, despite everything, I am never quite finished with. How can one truthful map point out all these Damascus cities? Or can they map out the Europe I had imagined growing up? Did that image affect my understanding of myself and my city?

I have longed all my life to live in the west. Funny enough, that created a nostalgic nature to how I related to Damascus, home I would float amid the old city with the mind of a tourist, excited by seeing everything for the first time, getting lost in orientalist art and memoirs of trips with their assumptions and judgments

The few French toys left from my sisters and my early childhood years. These are an embodiment of the name of the Parisian suburb that would mark my identity cards

This obsession with the west, I learn later, as E Saiid describes it, is an internalized Orientalism. A mindset where I look for myself in articulated perceptions and fantasies of how the west views me. Am I choosing to be the mystic poet they see in Rumi and Joubran? Or the pan arabist Nasir with strong opinions about the west. Facing these projections I am led to embark on a journey trying to map my own, and interviewing others to help me see how they do that

Excerpt making stories from interviews by

Sammy Zarka_ Rabab

Interviewed in October 2023 - Displaced from Damas, Afif.

Rabab lived in a ground floor apartment in the densely populated neighborhood of Afif; a late Ottoman neighborhood in Damascus at the foothills of Mount Qassayoun.

The two storey building is a 50s modernist white apartment building, situated beside a chicken grill, a bakery and Homsani (falafel stand) I imagine their backyard always to be filled with the aromas of local fare

“I grew up in this apartment with my parents, sister and brother. When I got married I moved away, then moved back again before leaving for the states and then to Montpellier

The apartment had 2 doors; one leading to the kitchen, while the other took you to the entrance leading to the living and guest rooms in the front of the house and the three bedrooms at the back of the house. The living room faced the Qibla (the direction to Mecca) and had two wide windows with a door in between that led to the front yard.

The religious side of our family did not approve of having paintings of creatures with a soul; so none of the objects we had depicted animals or humans, apart from the Romeo & Giulietta Style guest room furniture that depicted scenes from the lovers legend.

A big window overlooking the yard is opened at the depth of the guests room while to the left of the entrance stood a three segmented Chinese paravent that my parents shipped to Damascus from the house they lived in Kuwait. The paravents had flowers painted on them.

Our bedrooms had high windows that overlooked the low end of the street behind, we could see and hear people’s feet as they walked past. In contrast to the apartment I live in now, our kitchen did not have windows and was at the opposite end of the yard, this led us to build another outdoor kitchen and a small toilet.

In the early 2000’s we started experimenting with having others rent our apartment with us. I still fondly remember an Algerian couple who shared our apartment with us for three years. There was space in the girls 8

bedroom as my brother and sister had moved away to live with their spouses.

We spent most of our time in the yard; It was fenced with elegant minimal metalwork and then covered with panels of bamboo that we had painted green.

My fondest memory of the yard was a vine that we planted at one corner; it shaded most of the front yard. We used its leaves to stuff and make Yabraa (stuffed vine leaves).

Next to the vine we had pomegranate and loquat trees that hung over into the street The children would carefully pick the fruits in the summer I would see them and encourage them to do so.

At some point we decided to cut down the tree to terrace that side of the yard so we could place a swing; here I would happily spend summer evenings watching people in the street through the bamboo

An established jasmine flowered at the other corner and framed the entrance of the building.

After I moved away we sold that apartment and I had never been back to Damascus since.”

I have personal memories in Afif and had eaten many times at these places adjacent to Rababs front yard. I was always curious to imagine the lives of others; always contemplating the lives that were being lived behind that bamboo covered fence, as I stood in line waiting for my falafel.

Interviewed in October 2023 - Displaced from Aleppo, Al Zahraa compound.

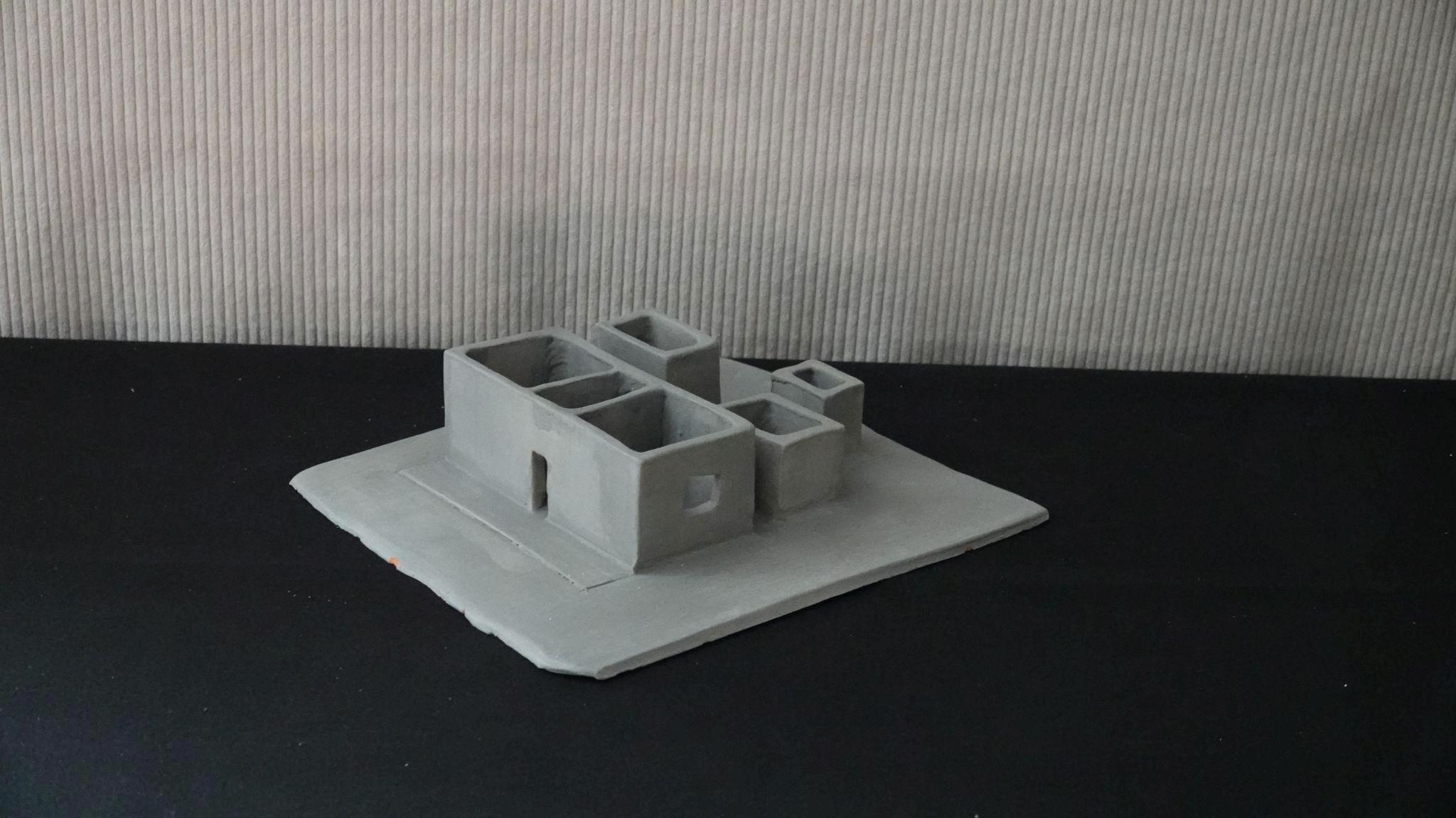

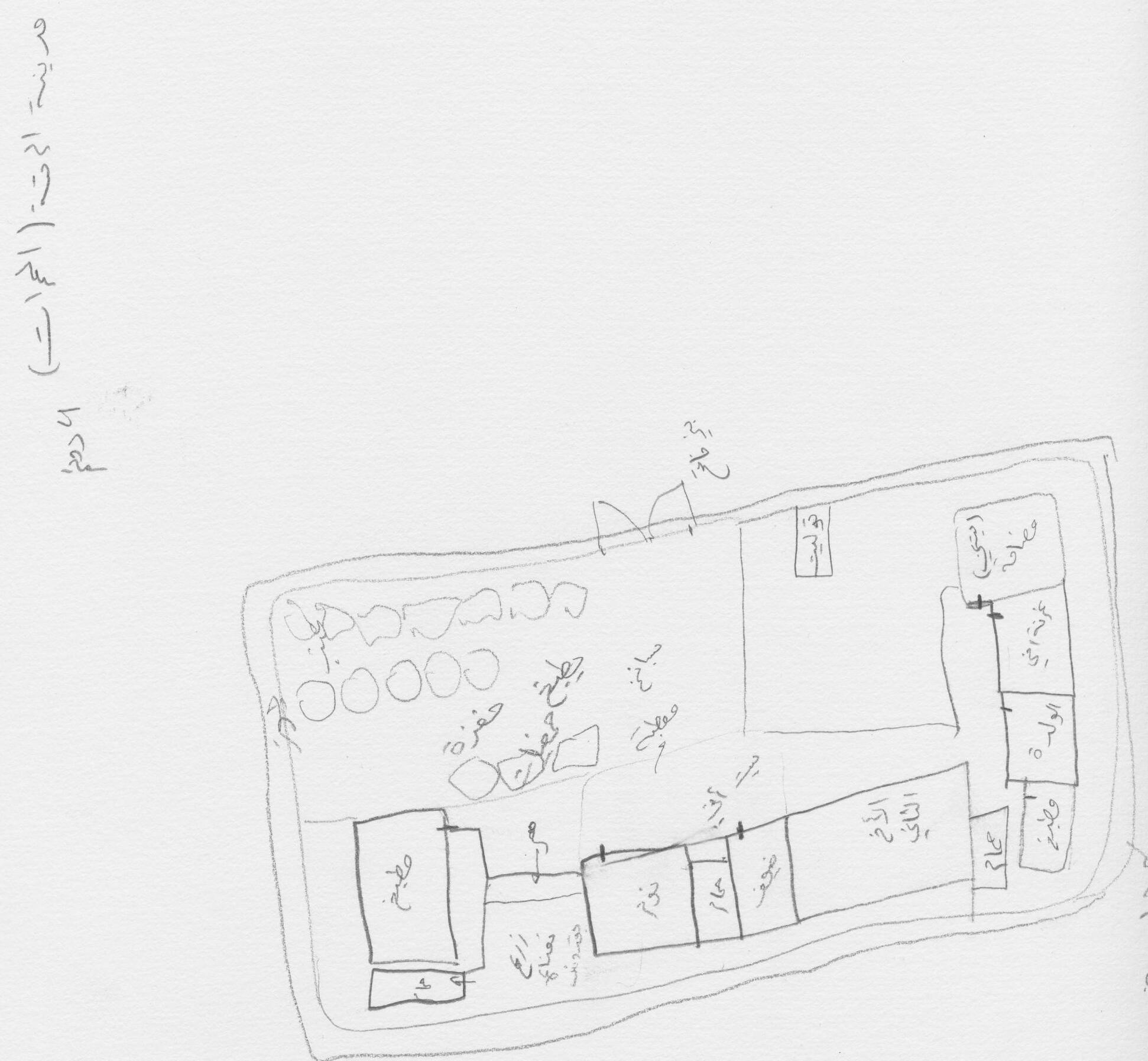

In a very elaborate manner Ramez described to me the process of his home's construction; explaining construction techniques, old and new in the region

The Zahraa compound is a neighborhood north of New Aleppo that, as with most development, was at the expense of agricultural lands. Ramez’s home was in a buffer zone between Zahraa and a village called Alleramoon. He described the home he grew up in and built on until perfected before he left Syria for Turkey In Turkey he worked on making another home before ultimately moving to Montpellier, where he reopened his hair salon and, once more, built a home.

“The house I grew up in was built by my father on our land that was surrounded by olive trees When I got older and my business prospered I decided to enlarge the property, doubling the rooms vertically In a later phase extending to the back, adding three more rooms for the growing family.” Ramez told me about the building tradition in the region; how the foundations are laid, and what ways there are to manage both underground water and rocks in the same building lot “I definitely think that local building labor in Syria is one of the best in the region For my home, I followed every step of construction and micromanaged it myself. I wasn't surprised when Aleppo’s informal suburbs resisted the earthquake better than its Turkish counterpart.” I often had to guide the conversation to focus on the spaces of the home and the memories, as he insisted on teaching me all about the construction traditions “And what are these rooms for?” I would say. “Private rooms,” he answered. “Bedrooms?” I said. “Yes, private rooms.” “Do you want to share anything about your memories there; your choices in design, color, orientation?” I added. He pointed away from the rooms and went back to the main guest room “You see, I also made sure the details of the stone finishings were fancy, framing the windows and doors with particular ornaments The metalwork of the windows included a curved extrusion so that kids can take out their heads to be almost outdoors while being inside.”

While taking the tram after leaving Ramez I worried that I had pressed him too hard to share his memories. During the ride, I realized that his focus on building techniques was very personal. He connected to his home through each decision he made about its materiality to the methods of construction. This form of engagement, focusing on the physical aspects of construction, is as meaningful as the memories that fill a home. It’s a reminder that we all value our homes in different ways. Some through the stories and moments shared within their walls; and others, like Ramez, through the very act of creating those spaces

Interviewed in October 2023 - Displaced from Raqqa, Al-Hamrat village.

Abu Mulham was twenty when he left Syria. He lived in Al-Hamrat village at the Euphrates river bank in Raqqa province in North East Syria.

“Our home was a four acre fenceless land, in the past, even the rooms we built on our property had no doors. Everyone knew their neighbors’ land limits and respected them.''

Out of curiosity months after interviewing Abu Mulham I tried to find his land on google maps, to no avail Aerial views only showed half of the village while the other half appears to be wiped out. What was visible is a dream-like village with fenced lands shouldering one another with patches of orchards and streams cutting through. Each portion of land seemingly had rooms scattered and connected to one another with terraces There were no labels or location markers on google maps

“But then we did fence it. A big entrance on the long side was the only way in, a four meter wide light brown painted metal gate. I moved away in 2015 after living in that house with my mom and my three siblings My dad passed away when we were kids

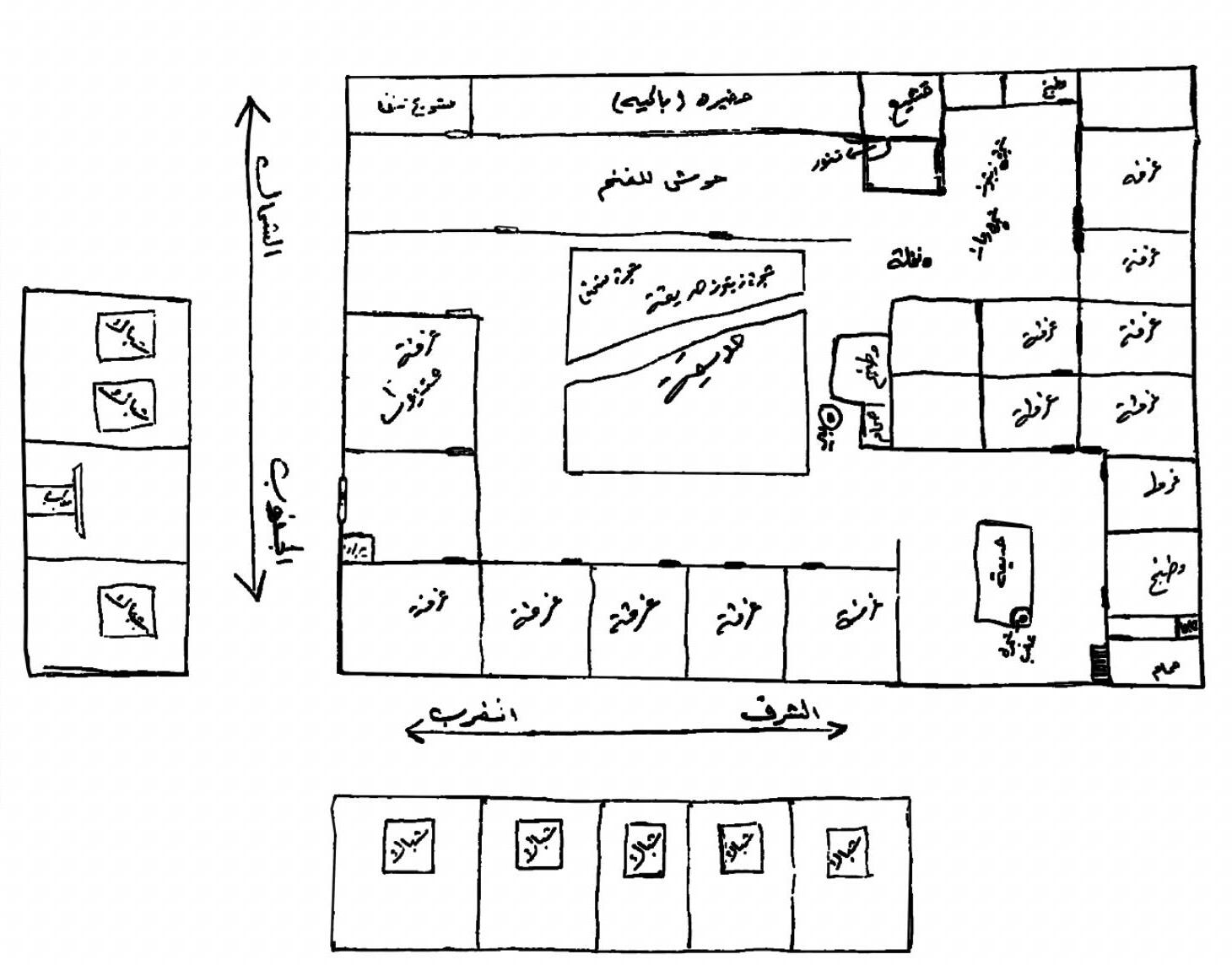

To the left of the gate there is the first guest room followed by the second that is a bigger “Madafa”, a 9x4 meter room that fits about a hundred guests. It later became my home.

The room adjacent was a bit smaller and is where my brother lived with his wife and two children.

Later a brother of mine married and had many kids, he then built his own rooms on the opposite end of the land. A few rooms with a separate bathroom and his own guest house. These rooms would overlook a terrace that he paved with thick stone tiles. In the daytime it was unbearably hot as there was no shade; but we all enjoyed gathering there on late summer nights, wetting the tiles helped in making the dry weather more pleasant The kitchen and toilet were connected to the terrace with a narrow paved passage that bordered a kitchen garden. As the youngest of the brothers got older he made the last addition by building a couple rooms that connected both wings of our little family

village. These rooms sat at the long side of the terrain and were built very close to the wall that surrounded it. Only later people started building walls. The walls had to be free on each side leaving corridors between the closely built ‘patches’ ”

I asked a few times whether they had any trees. Everytime he would tell me I will get to that.

“As we gradually built the terrain the existing plants were never compromised; At the gate at the western end; we had grape plantations which were bordered by huge walnut trees and of course lemon and orange trees, which were closer to the houses. A fenced portion was dedicated to vegetable plantations, we grew peppers, cucumbers, lettuce and the watermelon that Northern Syria is famous for We used to eat what we produced and shared the rest with the neighbors. We didn't sell our products, but my uncle Khalil did. I remember one spring he planted his ten acres with watermelon. It produced double the expected amount. That summer is still remembered by the village as everyone ate their daily share of Khalil watermelons for a month At that time I was a student returning home to the village from France; he asked me about the fruit and vegetable culture there. I mentioned that they sold cucumbers by the piece and watermelon by the slice. I think I gave him the shock of his life “no blessing in industrial production” he said.

The last of the farm animals we had was around the time we were kids, back then most of our land was for our sheep and a little spot was for the two buildings where we lived.”

As Abu Mulham shared his story, it became evident that "home" encompassed much more than just the walls of his house Not even the terrain itself could encapsulate it fully. For him, home was the entire village its people, trees, water, and animals. This sense of home was deeply intertwined with the community and the natural environment, reflecting a profound connection to both human relationships and the land

Interviewed in October 2023 - Displaced from Aleppo, then from Gaziantep.

I was surrounded by all six family members when they invited me to sit at a coffee table in their small temporary apartment in Montpellier. They welcomed me warmly, bustling about to ensure that I was comfortable and as if I was visiting family

Majida and her family began their search for a new home in 2013, a few years into the Syrian war. When I asked them about the home they had left, they exchanged glances and responded sarcastically, “What home would you want us to refer to?”

Their journey had taken them from Aleppo to Latakia, then to Lebanon, followed by a move to Egypt and finally they settled in Gaziantep a Turkish city on the opposite side of the Syrian border from Aleppo. “The home you felt most comfortable in” I suggested. Without hesitation, they all said, “The house in Gazi!”; their faces glowing with smiles

No one seemed to agree on how the other drew the house; each drawing was quite different and highlighted its own unique details. Amid the discussion, Majida, who had been busy making and pouring tea, took a pencil and paper and left the room She returned with a hand-drawn map which seemingly resembled a map of one of the pyramids; rooms connected by corridors, and none of the rooms sharing any walls. The four boys and her husband looked at the map and exclaimed “YES! This is exactly how it was.”

Majida explains:

“I am about to tell you about the house where I lived the happiest days of my life. The house was spacious, with three bedrooms and a large living room. My spiritual dimension influenced how I arranged our living space. In a corner of the living room facing the Qibla—the direction towards Mecca—I placed a photo of the Kaaba next to a bookcase that was filled with copies of the Quran and prayer books. I often sat there alone, praying.

To the left of my prayer corner; adjacent to the window, stood a large dining table with six chairs, one for each family member. Every evening when my husband and children would return home, I would rush to the kitchen and serve the hot meal I had prepared that day. The big kitchen also housed a “Mouneh” (a food storage area). I always moved from room to room, ensuring everything was kept just the way I liked it; so anyone visiting would feel the tranquility and love nestled into the spaces I adored that house; it brought me immense joy The house also had a guest room with curtains I particularly liked

My favorite day was Saturday. My husband would return early to a sparkling clean house, and I’d be dressed up for a dinner date. Sometimes the kids would join us, other times we’d drive them to their grandparents The entire floor was carpeted, always clean and perfumed I devoted myself to preparing traditional Syrian meals. We had two fridges in the kitchen and a smaller fridge in our big bedroom for desserts and ice cream; necessary for our big family and the many guests we hosted. I was truly happy in that house, but we had to leave it and come here to France Nine months after leaving, I still remember every detail that made everyone lose track of time when visiting us in our home. I pray that one day I will manage to create a space here in France filled with love like that home was.”

As Majida shared her memories, everyone jumped in with their treasured recollections, pointing to the maps they had drawn “Oh no... you are making us think of our lost home now,” said Mahmoud. “Imagine living in a house that had walls covered with flowers! It had beautiful wallpaper that I will always remember,” he added.

At 4:17am on the third of February 2023; a devastating earthquake struck Turkey and Syria, severely damaging many of the walls in their apartment. Mahmoud marked these walls with an X. "It was my birthday. I remember waking up to my brother walking into the room and leaning against the wall beside us, trying to prevent it from falling on our beds." Mahmoud recalls with a laugh

Majida’s husband added, “The corner next to the entrance had a large vetrina where we placed a fancy set of china passed down from my late grandmother a set 200 years old." “Did you bring them here?” Hassan, the youngest, interrupted “No, we took them everywhere from Aleppo, but before moving to France I left them with the neighbors,” he replied.

They were curious about my background and began asking me about my own home. I shared my story; which, like theirs, involved repeated displacement They again emphasized how comfortable they had felt in their home in Gaziantep, comparing it favorably to the three different houses where they had lived in Cairo. I dreamt later that night that I was living with them in Cairo. That feeling of disorientation stayed with me for days.

Interviewed in May 2024 - Displaced from Palmyra.

Palmyrans continued to live among the ruins of their ancient city up until the mid-20th century. Izzat recounts Palmyrans displacement to the 1930s newly established urban settlement just outside of the old city of Palmyra He moved on to explain how he grew up there before his departure to France following its final destruction in 2014.

“My grandfather’s generation was the one that left the temple. Bel, the god revered by Palmyrans, was adapted to gain oracular functions in addition to being the mesopotamian cosmic deity, matching Bel’s central role in Palmyrene religious and social life, the centrality in position and scale (210x205 meters) reflected the importance of the temple dedicated to his worship.” Being built at its earliest stage in the 2nd century BC as a religious and social center of Palmyran life, it carried on that role as a Byzantine church then a mosque after Aurelian’s destruction of the city in 273AD

Palmyrans continued to inhabit the ancient city within the temple's borders, despite the various destructions that took place. The French archaeologist Henri Seyrig then completely removed its inhabitants to a French-built village adjacent to the site in 1932 Izzat’s grandfather was among those displaced and was to build his own house at the South East end of the village.

“It was a 600 sqm home, its mud bricks would define large rooms with high ceilings

One would enter the house into a Liwan; a vaulted 16 sqm hall leading to the Manzoul. My grandfather was a fabric trader so would often have bedouin producers visit and at times spend a few days as guests. They were hosted at the Manzoul that had a bathroom attached to its entrance

I remember the strong Tembak; Paan Shisha smell The smell was ingrained in the rooms floors, walls and fabrics. Like most Palmyran houses the Liwan led to the courtyard. The courtyard was surrounded by different rooms like the beit-el-mouneh (food

storage), kitchen and a bathroom. The many rooms that surrounded the court had large windows, I remember how the light would flood in.

Windows were positioned higher than eye level, preserving privacy and sort of making the rooms look like the Temple’s cella The high roof would lay onto a long straight palm trunk beam that supported the secondary wooden finished beams and the palm leafs which the final mud and lime finish was placed over.

The house also had a traditional matwi-hajar well (Arab stone-built well);. Roses and fruit trees filled the courtyard and to one side there was a stable that sheltered a camel and some sheep

The courtyard was marked by a palm tree that was adored by our family. Today as I scrolled through google maps I was happy to see that it appears intact amid the remains of our home damaged by a shelling in 2014 That year marked the last destruction of the historical site and its city and the beginning of my journey to settle in France ”

Interviewed in March 2024 - Displaced from Damascus, Dahdah.

This is one of the stories of chain displacement. Sarah describes the home that she remembers her grandmother lived in and how she came to live there; she joined and lived with her there during her first year at university

Zakyeh and Thakiyeh are two similar names in Arabic that are often confused. The first meaning pure and the second meaning intelligent. Zaki/eh is a common word used in Palestine. It extends in meaning to describe good in a wider concept; mostly referring to food, nature and bliss.

Sarah explains sharing the story of Zakyeh:

“My grandmother was born during the 1930s in Gaza, a Palestinian city. In 1948 as a teenager, my grandmother and her family were forced to leave their home as a result of the large-scale ethnic cleansing of Palestine. This catastrophe saw over 800,000 Palestinians displaced from their homes and stripped of their possessions; each still holds keys to their lost homes. My brother keeps ours.”

The Southern Syrian city of Daraa expanded to include a 40 000 sqm palestinian refugee camp, this is where Zakyeh and her family were displaced to after being expelled North out of Palestine. When she married a Syrian man she moved to Qunaitra. Here Zakyeh and her family built a home next to a small river in the Golan heights, Syria. In 1974 Israel invaded Quneitra and left it in ruins; Zakyehs newly found home was destroyed, driving her away once more. This time to the densely populated dynamic capital Damascus.

Michel Ecochard was an urban planner that played a major role in the transformation of the planning of Damascus In his radio-centric road system proposal he created a ring road around the old city This layout disregarded the Arab city planning in its socio-ecological conscious tradition; thus destroying parts of Damascus and implementing a classist system of neighborhoods and property ownership. Affirming the French

modernization vision on its mandates. Saroujah was a neighborhood that widely resisted the French mandate. In Ecochard’s plan the neighborhood underwent a devastating transformation, being divided by the Thawra eight lane road and inserting a major transportation hub

Just east of this road, in the Dahdah neighborhood, is where Zakyeh would finally make her home.

North of the Old city and on the opposite side of Barada river, the old city overflows beyond its ancient walls and is still composed of a dense network of courtyard houses “Why dont you buy your house instead of renting?” Her friends would ask. “I always worry the Zionists will steal it again.”

Sarah reminisces back to that house by means of vivid images: “Many are the images that cross my mind as I come to remember Tete’s house.

I fondly remember the courtyard with its lemon tree; each spring its blossoms perfumed the air, drawing us to gather more often in the courtyard.

The old tiles always caught my eye; adorned with a wine-color, white, green, and earthy brown floral geometric patterns. Whenever we discussed renovating the house I remember how important it was to me that we preserve the tiles..

I remember sleeping in the front room with wide windows overlooking the courtyard I would feel Tete’s hustle at dawn I would hardly open my eyes to see the dawn's dark blue hue gently seeping through the window The entire home would be asleep but Tete would be up praying. The call for prayer would echo through the courtyard while the rhythmic ticking of the old clock’s pendulum as it struck the hour often lulled me back to sleep; allowing me to dream endlessly about my future and where I might be.

I remember fondly the window in the room on the first floor. This was the room my mom grew up in. I remember it was always locked and Tete and Jiddo hid their stuff there. On rare occasions they would open the room and I would seize the moment to sit at the window. The window had a Mashrabyeh (screened window) overlooking the alley. I would tell them to leave me alone and sit for hours observing the neighborhood I could see

everything, but nobody could see me. I remember watching everyone who came and went and who received visitors. I would gaze at the bread seller on the corner, watching him spread the bread to dry. He would lay the bread on white sheets on the sidewalk in front of his shop The man was very sweet and he was almost 90. All this would take place amidst the urban clamor of confused footsteps, donkey carriages, people shouting for one another and the cooing of pigeons”

Interviewed in October 2023 - Displaced from Aleppo, Al-Kallaseh.

Aleppo was once Syria's largest city and economic capital. It is Known to be the world’s oldest surviving city. Its ancient neighborhoods consisted of a dense mix of residential courtyard houses, covered markets and public buildings; including mosques, khans, Madrasas and Bimarstans

The neighborhood of Al Kallaseh was one of the many areas that succumbed to severe damage during the war between 2012 and 2016.

Abu Ziyad was a resident of Al Kallaseh neighborhood. He shared his memories and the story of his departure; tears intermittently disrupted his narrative.

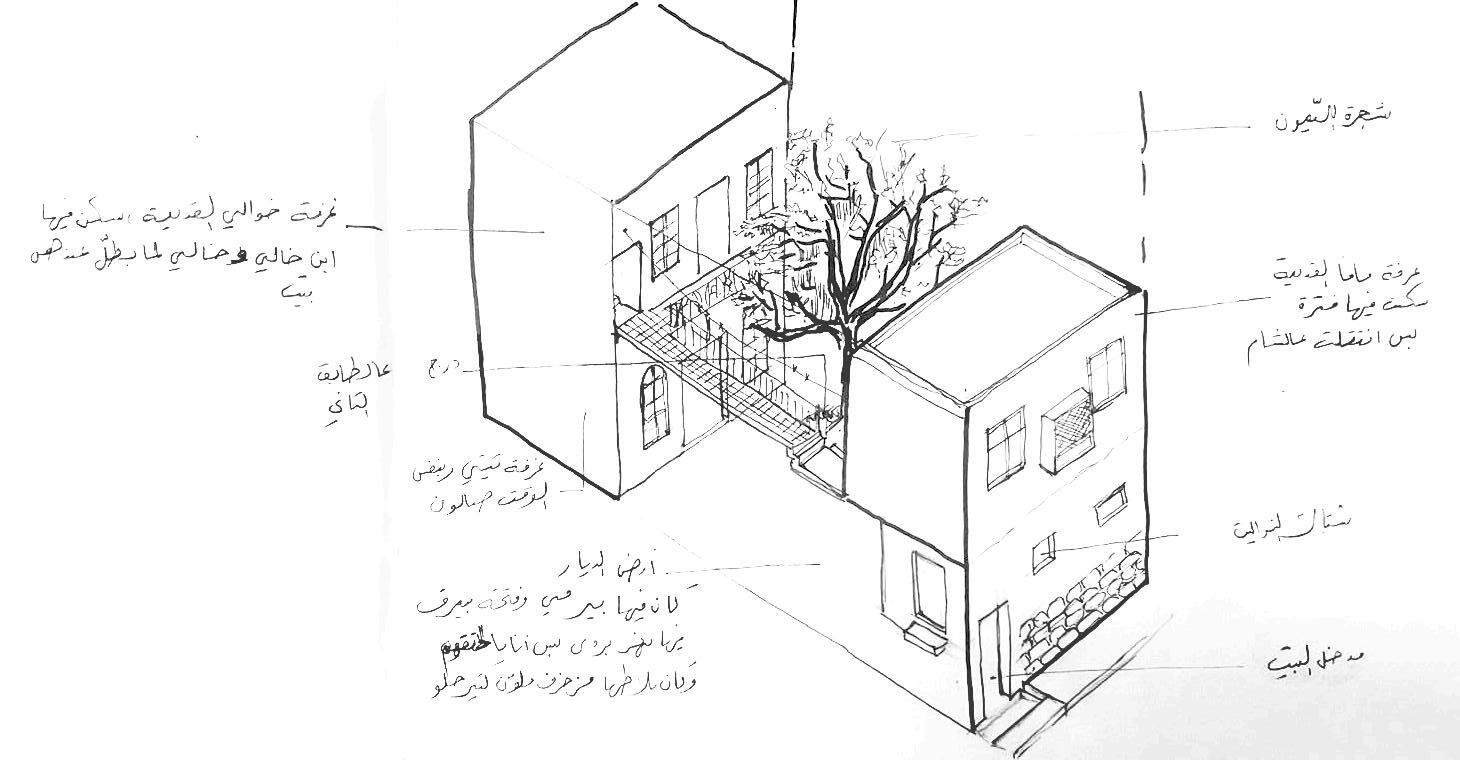

“Our alley was three meters in length at its widest. On one side of the alley there were newly built five storey buildings and to the other side was our house; a Housh Arabi, an Ottoman 17th century two storey courtyard house The narrow alley would lead you to a black iron door that would open to the Dahleez (a corridor guaranteeing privacy) breaking the visual connection between the entrance and the courtyard. As most of our relatives lived close by, our door was often kept open for them to come in whenever they pleased

To the side of the Dahleez there was a kitchen with a well What I remember most is the courtyard plants; rose bushes, a vine that surrounded the entire courtyard and climbed all the way up to the roof which was accessible by a staircase to the left of the entrance. Ramadan coincided with summer when I was a child. I remember us breaking our fast on the warm balmy evenings, while the smell of the mint called to be picked and sprinkled on the dishes. Stone tiles lined our big courtyard. More often than not, Housh Arabi houses had fountains to demonstrate the social class of the family. We were an average middle class family, but our large fountainless courtyard hosted most of the extended family’s weddings and celebrations

On the side of the kitchen door a staircase led to a basement where we had our Shaariya, a food storage room. I remember how humid it would be down there, the fridge was also kept there.

At the opposite end of the entrance there was a long living room that also had beds. To get to the room you would descend a few steps, so that from the windows you could directly see the bottom of the courtyard. I remember the smell of warmth in that room as during winters we would light the diesel fueled stove.

In the one corner of the courtyard adjacent to one of the windows there was a drainage pit. I had to manually empty it every time mom would wash the pavement.

The courtyard walls had nooks in them that were purposefully made for the pigeons to nest in I only lived in this house for eight years, I can still remember every detail. I can clearly recall the physical pain I felt when my dad decided to sell it. The family that bought it decided to demolish it to build a five story building in its place It was as if a piece of my little heart was ripped out We moved to live in a second floor apartment in a modern building a few blocks away. For the year to follow I would take a D-tour after school past our old house and wait there in the hopes someone would open the closed black metal door so I could get a glimpse of our courtyard. Once one of the neighbors saw me and managed to sneak me in; I have no memories of what I saw that day

The apartment building we moved to was next to an abandoned construction site that was closed off. I would always ask the adults questions about it as I was extremely curious to see it; it reminded me of our old home One afternoon I jumped from the living room's balcony and climbed down into the site’s courtyard I investigated all the rooms and was most intrigued by the plants taking over the building. I looked for lost familiar memories; I remember finding a football my friends had lost the summer earlier.

I still dream that one day I will buy a home where I can recreate these cherished memories, allowing my children to experience the same enchantment of courtyard universes as I did.”

Abu Ziyad explained his memories as he drew this map, annotating the rooms beautifully with Arabic calligraphy. When I complimented his writing he confessed he was a calligrapher.

“Next time I hope to see you in your dream house” I said as I thanked him and said goodbye.

“You may have to wait a long while! Who knows why I am still attached to the memory of that house Is it because I was so little? The place we moved to next did not leave much impact. Anyway, this material world is not worth much after all.” He says, striving to complete the lingering thought.

Interviewed in October 2023 - Displaced from Damascus, Al Qusour

Unlike the rest of the people interviewed, Maha did not leave for France during the war; but rather observed from afar the transformation of her childhood house She heard about the changes via phone and video calls; such things as how the view to the park was blocked by a new building, that some walls were demolished and the rooms were expanded, the loss of family members’ lives; and eventually the change of ownership.

Maha lived in the Modernist neighborhood of Qusour east of Damascus

The neighborhood was built in the 50s after being planned by the French urbanist René Danger during the French mandate on Syria. It was the beginning of the urban expansion that would eventually wipe out most of the agricultural land that fed the capital.

“Ours was one of the first buildings to be erected in the street I remember it was still surrounded by fields where I used to play soccer with the neighbors’ kids after school; before heading home to sit with my parents for lunch. The kitchen at the time was still not enlarged to include the balcony I can still see the newly planted palm tree through the kitchen’s window that would be veiled with mist as my mom would cook and remember the smell of burnt eggplants that filled the apartment.

I remember the rooms quite well with all their details. Yet, the actual feeling of home and the first thing that comes to mind when I think of it; is my youngest uncle As’ad and my grandmother Hind How I relate to my sense of home, belonging and its rituals I learnt from Tete. I remember as a seven year old girl observing her as she calmly gazed at her reflection and elegantly brushed her thick white hair. I remember being in her presence as her endless eloquence filled the guest room as she entertained the visitors Behind the reason she did not go to school is a story that explains her personality One day, six year old Tete went to the city hall to ask to change her name from Hindiyah to Hind, simply because she did not like it. This confidence intimidated her father who

was known to have said after the incident, “today she changed her name, tomorrow she changes the world, no more school for her!”

I left Damascus in the 80’s when I was still in my twenties This early uprooting must have kept my memories of home as they were as a child. The palm tree I watched from the kitchen never grew and the tall apartment buildings never replaced the fields of east Damascus.”

Interviewed in January 2024 - Displaced from Damascus, Barzeh.

Barzeh, another part of Damascus, was once an agricultural suburb which was developed into a residential neighborhood. It stretches along the northeast side of the city up until the slopes of Mount Qassioun Kareem grew up there in a gated community, a protected reality The area had a large social mixture of people that had come from all fourteen regions of Syria with their families; all from different cities, religious and ethnic backgrounds. Kareems’ mental map encapsulates furniture soaked in memories, the lines that represent the walls are so thin but the rooms are clearly defined by the objects and landscape surrounding the apartment.

“I made friends with most of the neighborhood kids, I had a friend in each one of the ten residential buildings in the Manara; the name of the community

After school, I would hang out in the square playing football and cards with friends until it got dark. Mom would call out to me to return home, her sharp voice would echo through the pines that lined our backyard. Our home was a raised ground floor apartment surrounded by a private garden on three sides, one of which bordered the mountain slope I spent a great deal of my childhood in the garden; discovering the soil, making clay and experimenting with the plants and insects I would find. I would overhear the neighbors' arguments at dinner on one side while I jumped over the other side to reach the mountain at night for a thrill of adventure. When I was grounded the generously leaning peach tree next to my window would be my escape route, allowing me to meet with my friends. Before we moved to that apartment I remember my grandparents would often go to plant trees, care for the rose bushes and water the jasmine that later climbed over the building’s corners. When I was a teenager my parents decided to expand the apartment, they built two extra rooms in the backyard We had to make the sad decision to cut down two of my favorite trees; the loquat fruit tree that strangely made me think of the Jungle Book and the huge apple tree that would fill the floor with white petals every spring. I would pick up the tree's apples throughout early fall and eat them when they ripened, just before the

birds would start picking on them. When the extra rooms were built the garden was split in two parts, after that everyone seemed to neglect the garden.

My mom spent most of her time in the spacious living room surrounded by books. Just like all of our rooms, its walls seemed to solely exist to hold bookshelves.

The soundtrack would switch from AlJazeera during the day to TV5 in the evenings and early mornings. Soap operas and pop music were not allowed at home I had to wait for smartphones to play my own music

My mom passed away suddenly when I was seventeen It became unbearable for us to be in the apartment she loved without her. After the funeral of my mother we never returned and moved in with my grandparents. Just a year later, I moved away from Syria.”

Kareem is my brother, and the rooms that were built in the backyard were mine. I left two years before my mom passed away and only returned to visit five years later, only to find an abandoned apartment and a dead garden. To this day, apart from the metal bars guarding the windows and doors, only the thousands of books stacked in every room protect our memories

Interviewed in October 2023 - Displaced from Aleppo, Radio neighborhood.

Nawal had lived in three different houses in Aleppo before she was forced to move to France. Her last home, which she had painstakingly furnished, was abandoned just two months after moving in Today, that house, as with the previous ones, lies in ruins

“The night we were told we had to evacuate, all I managed to take with me was my pajamas. The very next day, my home was destroyed by an airstrike. The following six years my family and I would move from one Syrian city to another until we finally relocated to Lebanon There, we registered with the UN refugee agency hoping for resettlement. When I received the opportunity to move to France, my initial concern was the dress code, particularly about being able to wear my headscarf to work. I later learned that this restriction was only for government jobs.

Since getting married I lived for the longest period of time at my in-laws' place. We stayed there for 14 years until my father-in-law passed away, the villa was subsequently sold. He was a well-known merchant in Aleppo and wanted his home to reflect his prosperity. To achieve this, he hired an Italian architect to design a grand villa

The villa occupied a vast plot of 1,350 sqm. It featured a swimming pool which was surrounded by a terraced orchard full of bitter orange, kapok, orange, apple, lemon, grapefruit, walnut, and olive trees. An expansive staircase led up to the house, opening onto a terrace which was encircled by a classic cast stone balustrade The main entrance door opened into a large formal lounge that was filled with my father-in-law’s antique collection. A variety of colorful crystal water pipes, Persian silk carpets with forest and peacock motifs, vases and statues were displayed on shelves all around the room. This room was separated from the living room by a sliding door and was only used when we had guests

The living room connected to a corridor that led to the family entrance, the kitchen and the bathroom. Four bedrooms lined this corridor, each

offering different views of the lush orchard. This was all located on the first floor, where my in-laws lived.

My family’s living space was in the basement It was accessed through a back door, you then descended two flights of stairs to three main doors, each leading to an apartment. The spaces were originally intended as guest lofts for the three siblings. My apartment was modestly furnished. Upon entering, you would find the bathroom to your right and the kitchen adjacent to that To the left, a spacious living room extended back to my bedroom, which was separated by a sliding door High-set windows offered views over the lower part of the terrace, from where, during gatherings, we could discreetly observe the elegant movements of our guests below.”

Abu Mulham, Fatima, Iman, Izzat, Abu Wissam, and all those who generously shared their stories and opened their homes to me, Mouna Zarka, who connected me with Syrian families in the region between Sète and Montpellier, Andrew Turpin, for the loving work on proofreading the English texts, Pascale Ciapp of Espace o25rjj, who put her heart into every step of this adventure and shared both her home and family, Sarah Husein, who listened and shared her story,

Nizar Zarka, my father, for his constant support, Muna Imady, my mother, whose soul and books will remain my floating home, Elaine Imady, my grandmother, who sparked my curiosity and gave me a love for archaeology,