From the famous ocean walks of tourist hubs Newport and Ogunquit to lesser-known paths through wilder landscapes, we share our 12 favorite places to stroll by the seashore.

For the fifth year running, Yankee readers picked up their cameras to look at our region in fresh new ways. We think you’ll agree they succeeded.

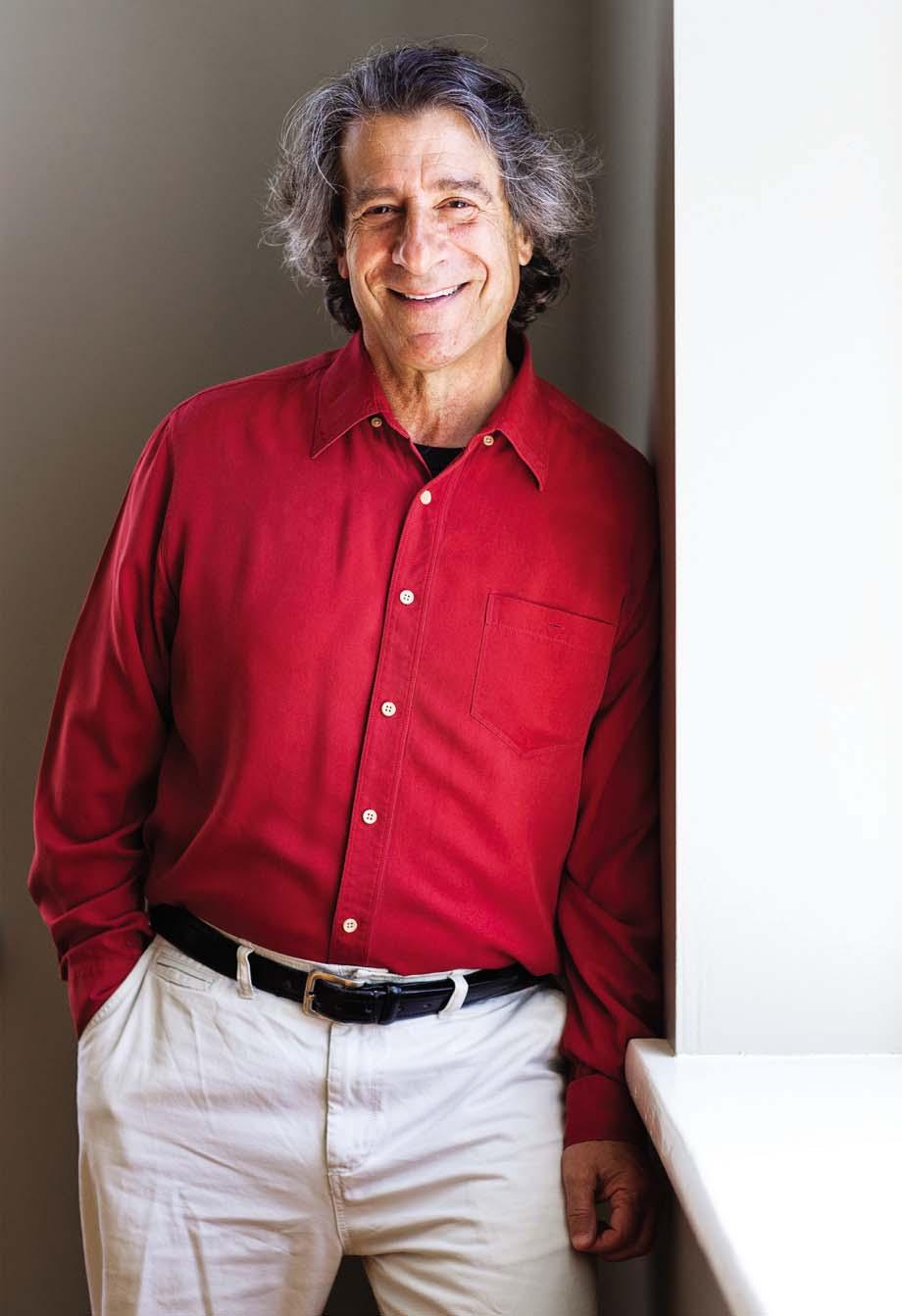

Tom Stuwe’s decades-long career as a Vermont country vet has given him experience with creatures great and small— and insight into those who care for them. By Ben Hewitt

114

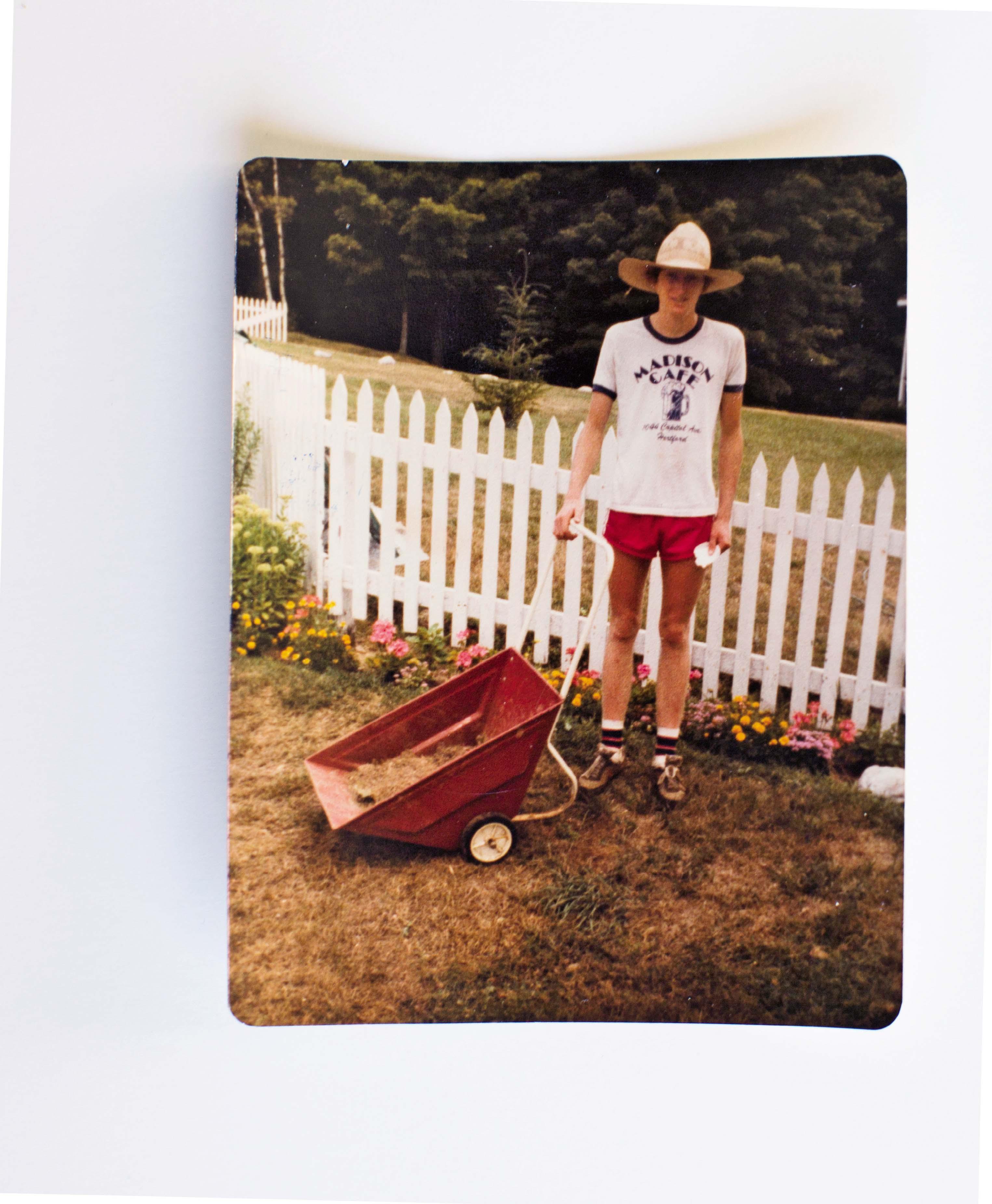

They said it would be a chore, and it was. But tending to a broken-down old fence also became a way to honor a home’s generations of caretakers. By Bill Donahue

118

In Lewiston, Maine, thousands of African immigrants are making a brighter future for themselves. In the process, they’re doing the same for Lewiston. By Cynthia Anderson

Originally from Somalia, friends Ali, left, and Faysal are now fourth-graders in Lewiston, Maine.

Originally from Somalia, friends Ali, left, and Faysal are now fourth-graders in Lewiston, Maine.

Travel along the epic route forged by Lewis and Clark in complete comfort aboard our elegant new riverboats. Experience our award-winning guided excursions that give you an insider’s perspective of the most captivating destinations including Multnomah Falls, Mount St. Helens, and the Columbia River Gorge. Small Ship Cruising Done Perfectly.™

Call today for your free cruise guide.

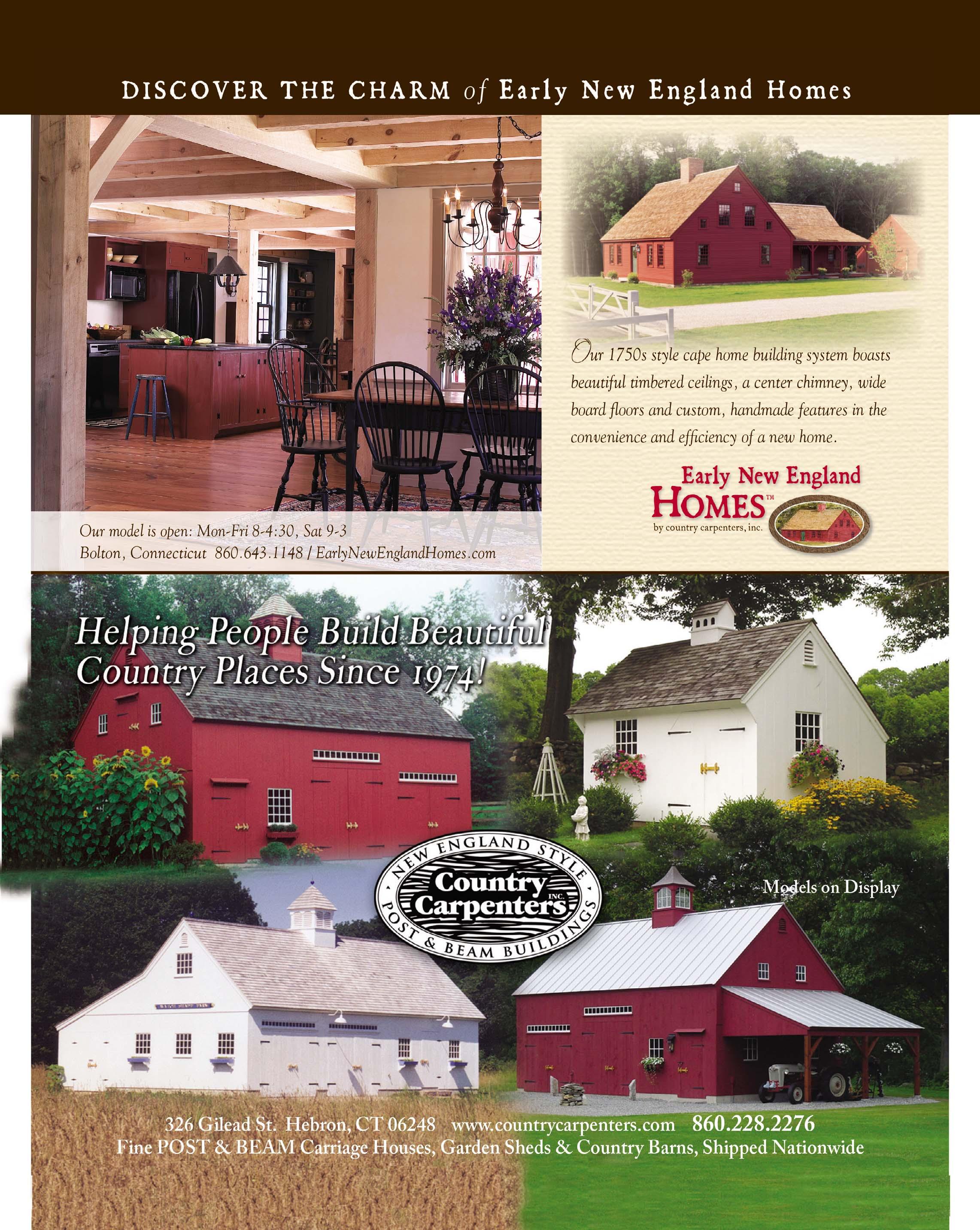

30 /// The House That Changed Everything

Architecture fans everywhere mourned the loss of the iconic seaside mansion Kragsyde, but only two decided to honor its memory by replicating the 1880s masterpiece—from scratch. By Jane Goodrich

40 /// Open Studio

Using the forest as his palette, Craig Altobello takes marquetry to new artistic heights. By Annie Graves

44 /// House for Sale

We thought this Connecticut River property sounded too good to be true. We were, happily, dead wrong.

By the Yankee Moseyer

By the Yankee Moseyer

50 /// “Weekends” Warrior

Go behind the scenes of our new TV show, Weekends with Yankee, with intrepid food editor Amy Traverso.

64 /// New Vintage Cooking

The marvelous soothing power of old-fashioned maple dumplings. By Amy Traverso

68 /// Could You Live Here?

Step back in time in the highly walkable enclave of Old Wethersfield, Connecticut. By Annie Graves

74 /// The Best 5

At these eco-savvy New England inns and hotels, it’s easy being green. By Kim Knox Beckius

76 /// Local Treasure

In Boston, two Kennedy museums illuminate the enduring promise of democracy. By Joe Bills

80 /// Out & About

The sweetest maple festivals this season, plus fairs, concerts, and other events worth the drive. 68

10

DEAR YANKEE, CONTRIBUTORS & POETRY BY D.A.W.

12

INSIDE YANKEE

14

MARY’S FARM

The surprisingly patriotic past of a humble backyard shed. By Edie Clark

16

LIFE IN THE KINGDOM

On a newly built homestead, winter survival gives way to springtime revival. By Ben

Hewitt

Hewitt

20

FIRST LIGHT

Walking with memories on the Appalachian Trail. By Christine Woodside

24

UP CLOSE

How the Segway scooter navigated the road to fame. By Heather Tourgee

26

KNOWLEDGE & WISDOM

An ode to slushy skiing, tips on evicting squirrels, and celebrating 20 years of Good Will Hunting

144

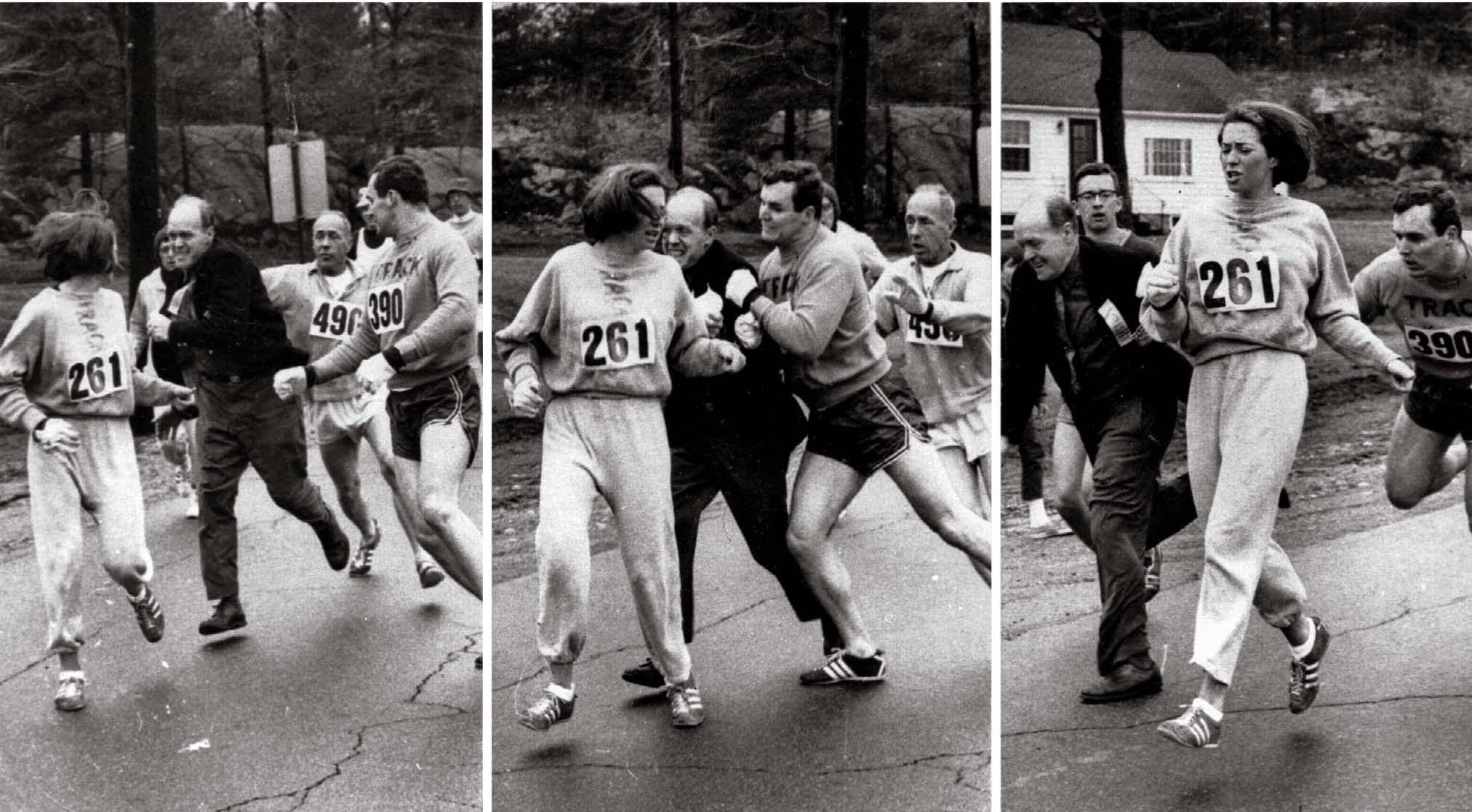

Looking back at the Boston Marathon moment that became a milestone.

1121 Main St., P.O. Box 520, Dublin, NH 03444. 603-563-8111; editor@YankeeMagazine.com

EDITORIAL

EDITOR Mel Allen

ART DIRECTOR Lori Pedrick

DEPUTY EDITOR Ian Aldrich

MANAGING EDITOR Jenn Johnson

SENIOR EDITOR/FOOD Amy Traverso

PHOTO EDITOR Heather Marcus

SENIOR PHOTOGRAPHER Mark Fleming

DIGITAL EDITOR Aimee Tucker

DIGITAL ASSISTANT EDITOR Cathryn McCann

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Joe Bills

HOME & GARDEN EDITOR Annie Graves

INTERN Montana Rogers

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Kim Knox Beckius, Edie Clark, Ben Hewitt, Julia Shipley

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS Julie Bidwell, Kindra Clineff, Sara Gray, Corey Hendrickson, Joe Keller, Joel Laino, Jarrod McCabe, Michael Piazza, Heath Robbins, Carl Tremblay

PRODUCTION

PRODUCTION DIRECTORS David Ziarnowski, Susan Gross

SENIOR PRODUCTION ARTISTS Jennifer Freeman, Rachel Kipka

DIGITAL

VP NEW MEDIA & PRODUCTION Paul Belliveau Jr.

DIGITAL MARKETING MANAGER Amy O’Brien

YANKEE PUBLISHING INC.

established 1935

PRESIDENT Jamie Trowbridge

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Judson D. Hale Sr.

VICE PRESIDENTS Paul Belliveau Jr., Jody Bugbee, Judson D. Hale Jr., Brook Holmberg, Sherin Pierce

CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER Ken Kraft

CORPORATE STAFF Mike Caron, Linda Clukay, Sandra Lepple, Nancy Pfuntner, Bill Price, Christine Tourgee

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

CHAIRMAN Judson D. Hale Sr.

VICE CHAIRMAN Tom Putnam

DIRECTORS Andrew Clurman, H. Hansell Germond, Daniel Hale, Judson D. Hale Jr., Joel Toner, Cor Trowbridge, Jamie Trowbridge

FOUNDERS

ROBB & BEATRIX SAGENDORPH

PUBLISHER Brook Holmberg

ADVERTISING: PRINT/DIGITAL

VICE PRESIDENT/SALES Judson D. Hale Jr.

SALES IN NEW ENGLAND

TRAVEL, NORTH Kelly Moores (NH North, ME) KellyM@yankeepub.com

TRAVEL, SOUTH Dean DeLuca (NH South, CT, RI, MA) DeanD@yankeepub.com

TRAVEL, WEST David Honeywell (NY, VT) Dave_golfhouse@madriver.com

DIRECT RESPONSE Steven Hall SteveH@yankeepub.com

SPECIAL PROJECTS Rebekah Valberg, 617-733-2768 Rebekah@maxradius.net

CLASSIFIED Christine Anderson Yankee.MyAdPortal.com

SALES OUTSIDE NEW ENGLAND

NATIONAL Susan Lyman, 646-221-4169 Susan@selmarsolutions.com

CANADA Alex Kinninmont, Françoise Chalifour, Cynthia Jollymore, 416-363-1388

AD COORDINATOR Janet Selle

For advertising rates and information: 800-736-1100, ext. 149 NewEngland.com/adinfo

MARKETING

CONSUMER

MANAGERS Kate McPherson, Kathleen Rowe

ASSOCIATE Kirsten O’Connell

ADVERTISING

DIRECTOR Joely Fanning

ASSOCIATE Valerie Lithgow

PUBLIC RELATIONS

BRAND MARKETING DIRECTOR Kate Hathaway Weeks

NEWSSTAND

VICE PRESIDENT Sherin Pierce

DIRECT SALES

MARKETING MANAGER Stacey Korpi

SALES ASSOCIATE Janice Edson

SUBSCRIPTION SERVICES

To subscribe, give a gift, or change your mailing address, or for other questions, please contact our customer service department: Online: NewEngland.com/contact

Phone: 800-288-4284

Mail: Yankee Magazine Customer Service

P.O. Box 422446

Palm Coast, FL 32142-2446 Printed

Seasons: Best Spring Flower Festivals

Craving color? Check out these bloom-filled ways to kiss winter good-bye.

NEWENGLAND.COM/ FLOWERFESTIVALS

Recipes: Saint Patrick’s Day Favorites

Ten sweet and savory dishes to satisfy the Irish in all of us.

NEWENGLAND.COM/ STPATRICKSDAYFOOD

Travel: Mad About Maple

We’ve got your cravings covered with a state-bystate guide to the region’s top maple fests.

NEWENGLAND.COM/ MAPLECELEBRATIONS

Crafts: Naturally Vibrant Easter Eggs

How to create colorful, natural egg dyes from common kitchen ingredients.

NEWENGLAND.COM/ EASTEREGGS

MARK

“Riding shotgun with a large-animal vet definitely lands in my all-time 10 favorite assignments,” Fleming says of shooting “A Farmer’s Best Friend” (p. 104). A proud resident of Portland, Maine, who studied photojournalism at the Rochester Institute of Technology, Fleming recently joined Yankee as senior photographer after working for the likes of Down East and Boston magazines, REI, and L.L. Bean.

Growing up in western Maine in the ’70s, this author and journalist spent a lot of time in Lewiston (“City of Hope,” p. 118). For 12 years she’s been writing about the city’s new immigrants—and its transformation. “When I’m with friends drinking chai in a downtown café,” she says, “I have a feeling of having come full circle.” Her in-progress book, Isbedal, follows seven new residents up to and beyond the 2016 election.

BILL

In “Painting the Fence” (p. 114), Donahue describes just part of a larger effort to reinvigorate the New Hampshire house that’s been in his family for more than a century. “It’s all about making the house stand up and survive for—let’s say at least 30 years, at which point, I hope, I’ll hand the task off to the next generation,” says Donahue, who has also written for The New Yorker and The Atlantic, among others.

CINDY

An award-winning oil painter with a BFA from the New Hampshire Institute of Art, Rizza found a bit of serendipity in illustrating “Painting the Fence” (p. 114): Turns out, she’s friends with some of the author’s neighbors at Gilmanton Corners. “It seems like a truly special community where everyone knows each other,” she says, “especially those tasked with maintaining the charm of the old homes there.”

A veteran photojournalist who previously worked for the Washington, D.C., bureau of The New York Times, Toensing brought a unique perspective to documenting the African immigrant community in Lewiston, Maine (“City of Hope,” p. 118). Through the nonprofit VisionWorkshops, she has helped teach photography to Somali and Sudanese refugees in Maine, and Burmese refugees in Baltimore.

CHRISTINE WOODSIDE

Woodside, a Connecticut-based writer and editor, says the experience of hiking the Appalachian Trail has changed a lot in the 30 years since she first tackled it (“Trail of Memories,” p. 20). In many ways it’s less challenging, a fact that she mourns: “Carrying our own gear and being truly out of touch with the home front, as we were back in the pre-cellphone 1980s, made me a more resilient and grateful person.”

Your article on Joel Woods [“A Hard Life Made Beautiful,” January/February] speaks volumes on what it takes to become an artist in photography. The real artist is self-taught and schooled by reality; gets his photo ops in the rough, instantaneously, while being extraordinarily alert and balanced; and uses any camera he can get his hands on. The wannabe buys a Canon or Minolta, signs up for a course or curriculum, and then rides around during foliage season to be delivered photo ops on a silver platter. (By the way, I’m more the inbetween type....)

David

SöderbergGlastonbury, Connecticut

I really enjoyed the January/February issue, especially Ben Hewitt’s column, “The Wheel Deal.” I chuckled when it mentioned that the Subaru was the unofficial state automobile of Vermont. I, too, own a Subaru, a 2011 Outback with just under 140,000 miles. They are great cars and run forever. We have owned many vehicles, from hand-me-downs to former police cars, but I have a feeling we will be driving our Outback until the wheels fall off.

Smart, those Vermonters.

Gretchen Becker Albuquerque, New Mexico

Thanks so much for the piece on the Sacred Cod [Up Close, November/ December]. When I was a kid in the ’50s, my grandfather was a court officer in the Massachusetts Statehouse. He always told me it was his job to guard the Sacred Cod. Now I have something to prove to my doubting friends that the big fish exists!

Elizabeth E. Brown Lancaster, PennsylvaniaPS: He also told me it was his job to paint the dome gold.

I was delighted to see mention of Calvin Coolidge’s 1924 campaign in Yankee [“Getting Out the Vote,” November/December]. However, the accompanying photo actually shows President Coolidge’s father. (Both were named John Calvin Coolidge.)

Coolidge’s father had a great influence on his son’s life, and one can only imagine his thoughts as he contemplated this election, which Coolidge would win in a landslide.

Apartment and cottage living at Piper Shores offers residents fully updated and affordable homes, with all the benefits of Maine’s first and only nonprofit lifecare retirement community. Located along the Southern Maine coastline, our active, engaged community combines worry-free independent living with priority access to higher levels of on-site healthcare—all for a predictable monthly fee.

Calvin Coolidge

Diane Kemble Education director, Presidential Foundation

Presidential Foundation

Plymouth Notch, Vermont

The feature “Curious About George” [January/February] incorrectly identified a Portsmouth, New Hampshire, church where George Washington attended services in 1789. Then called Queen’s Chapel, it is today known as St. John’s Episcopal Church.

t’s been nearly a century since a 7-pound baby boy was born at 83 Beals Street in Brookline, Massachusetts, on May 29, 1917. His parents named him John Fitzgerald Kennedy, and it’s almost inconceivable that he would have turned 100 this year, since we know him forever as a president with youth, vigor, and optimism, standing on a Cape Cod beach, hair tousled by a salt-filled wind. In “Beyond Camelot” (p. 76), we remember JFK, his brother Ted, and an era when politics was defined by civil discourse as we visit the two adjacent Boston museums that speak to the Kennedys’ legacy at a time when understanding history has seldom felt more important.

JFK loved the ocean. Indeed, visitors to the smaller John F. Kennedy Museum, in Hyannis, will see his statue outside, caught midstride among tufts of beach grass. For most of us, a walk by the ocean remains one of life’s great levelers. When you stroll beside the wave-rippled water with seabirds fluttering all about, it matters little if you are young or old. Life seems better then. It just does. In “Walks Worth Their Salt” (p. 86), we take you along on some of our favorites. But it’s far from an exhaustive list—so much coastline, so few pages—and intrepid seekers of coastal walks no doubt have their own special trails and beaches. We want to hear about those, too, so email your personal picks to editor@yankeemagazine.com.

Our lead story (“City of Hope,” p. 118) centers on a small Maine city filled with recent arrivals from distant shores. More than almost any other community in the country, Lewiston has seen a seismic shift in its identity: Of its nearly 36,000 residents, some 6,000 emigrated in the past 16 years from African nations beset by strife. Many are Muslim. They want to work, raise families, and thrive in New England. Writer Cynthia Anderson follows some of these new Mainers, who have known hard pasts and now face a future that seems a bit more brittle than it did a few months ago.

As you get to know these newcomers, ask yourself if their hopes and dreams are all that different from those of two families who arrived in New England in the mid-19th century, driven from Ireland by the potato famine. The Fitzgeralds emigrated from the village of Bruff, in County Limerick; at the same time, a cooper named Patrick Kennedy set sail for the United States from Dunganstown. Years passed and marriages happened and generations followed, and on May 29, 1917, a baby boy was born in Brookline.

Mel Allen editor@yankeemagazine.com

ore than 30 years ago, I bought a little cottage called Bide-a-wee in the woods off Seaver Pond. Along with another, larger outbuilding, there was a small shed beside the remains of a stone foundation. That shed was tall, with a hip roof, bigger than an old phone booth but not by much. Despite the sturdy construction, it seemed to me the shed must have been an outhouse.

My only neighbor, Paul Geddes, lived up at the Seaver farm. Also known as Silver Lake Farm, it once was owned by Edgar Seaver, legendary for his bachelor lifestyle and Yankee thrift. At one point Bide-a-wee had been part of the Seaver farm, even if just as a rental; Edgar, who ran the rural mail route by horse and buggy, gave the cottage its name, which means “stay awhile” in Scottish parlance.

Paul, who worked for Edgar as a kid, became a great friend to me, and over the years he’s provided me with stories about Bide-a-wee and Silver Lake Farm. He’s the one who told me that the structure I thought was a mere outhouse began life as a government-issued “spotter shed,” where citizen volunteers would sit to watch for enemy planes during World War II. Having never heard of such a thing, I found this intriguing.

In order for my shed to have been a spotter shed, Paul explained, it couldn’t have started its life in the Bide-a-wee woods. Instead, it sat up on the high point of Silver Lake Farm, in that wonderful open meadow that offered views of both our beloved mountain and Silver Lake, which sparkled and beckoned in the near distance.

At that time of war, there were many other spotter sheds across the country. In fact, almost any high hill with an unobstructed view was crowned with such a structure. The Ground Observer Corps—all volunteers who wanted to help the war effort—occupied these sheds. Ranging from teenagers to senior citizens, these vigilant observers sat in the sheds for hours at a time, in shifts, scanning the skies for Axis planes. Usually there were charts on the walls, bearing the profiles of enemy planes so that they could be easily identified. Apparently the sheds were also equipped with a phone (which for me solved the question of why there were wires stapled to the outside of my little outbuilding); if a plane was spotted, it could be reported to the number written on the wall.

No enemy aircraft was ever identified over the continental United States during World War II; still, this plane-spotting program was part of everyday life back then.

Paul was not on the farm during the war—he was in San Diego, serving in the Navy—but he does know about the shed. “It was a government building,” he recalled. “They provided it when the war began, and after the war it was Edgar’s to keep. Perfectly good building.” He doesn’t remember exactly when, but at some point the little shed gravitated down to Bide-a-wee, where it has spent the intervening years. And yes, he said, one of its many uses was as an outhouse.

Who would have guessed that an old shed, once used as an outhouse, sitting now at the edge of the forest, could reveal such an interesting tale of national security? History is hidden in the oddest places.

Dear Reader,

The drawing you see above is called For Now and Ever. It is completely composed of dots of ink. After writing the poem, I worked with a quill pen and placed thousands of these dots, one at a time, to create this gift in honor of the the love of two of my dearest friends.

Now, I have decided to offer For Now and Ever to those who have known and value its sentiment as well. Each litho is numbered and signed by hand and precisely captures the detail of the drawing. As an anniversary, wedding, or Valentine’s gift for your husband or wife, or for a special couple within your circle of friends, I believe you will find it most appropriate.

Measuring 14" by 16", it is available either fully-framed in a subtle copper tone with hand-cut double mats of pewter and rust at $145*, or in the mats alone at $105*. Please add $16.95 for insured shipping and packaging. Your satisfaction is completely guaranteed.

My best wishes are with you.

All major credit cards are welcomed through our website. Visa or Mastercard for phone orders. Phone between 10 a.m.-6 P M PST, Monday through Saturday. Checks are welcomed; please include the title of the piece and a contact phone number on check. Or fax your order to 707-968-9000. Please allow up to 5 to 10 business days for delivery. *California residents- please include 8.0% tax.

Please visit my Web site at

when you are not a part of me; you hold my heart; you guard my soul; you guide my dreams so tenderly. And if my will might be done, and all I long for could come true, with perfect joy I would choose to share eternity with you.”

n the first of February, we begin our move into the house. It is a mild morning, as many this winter have been; the ground is snow-covered, but only just, and in the process of moving we track a slurry of mud and melting snow onto the wide pine floors I’d sanded and finished a mere week before. At first this makes me tense, but I determine to let it go: These floors are going to see a heck of a lot more abuse than this over the coming years. Might as well break them in a bit. Naturally, the house is not finished. For instance, the stair treads consist of rough-sawn boards temporarily screwed to the stringers. Although we have arranged the upstairs into three rooms— one for each of the boys and another for Penny and me—there are no dividing walls, so the separation is mostly theoretical. There is running water at the kitchen sink, which after three months of hauled water seems a minor miracle, but the counters consist of old tabletops laid over rough framing. And in defiance of every building code ever written, our electrical power arrives via a homemade 400-foot extension cord running from an outlet at the meter, along the driveway, and through a window we leave open just enough for the cord to pass. For those of you rightly questioning our common sense or even sanity, please know that the outlet is what’s known as a ground-fault circuit interrupter, which continuously monitors current and shuts down if there’s any deviation.

Soon after we move, Penny and the boys embark on a road trip to Minnesota, where they’ll snowshoe half a dozen miles into the wilderness to spend a long week in a wall tent with similarly afflicted friends. “House living a little too comfy for ya?” I joke to the boys on the morning of their departure. They answer in the time-honored fashion of children the world over: with a silent roll of the eyes that speaks volumes.

With my family away, I soon fall into rural bachelor habits, eating when and what I wish from the same unwashed plate, if I use a plate at all. I stay up late, but strangely I wake even earlier than usual, my entire schedule thrown off-kilter by the solitude. Though of course I’m not really alone: With Penny absent from the bed, our dog, Daisy, takes up residence to my right, and Fin’s cat, Huck, tucks himself into the crook of my left arm.

To help pass this lonely time, I build shelves for the pantry, then fill them with the multitudes of jars and cans that have until now been piled in boxes. It is pleasing to stand back and see our stores of food arranged in neat rows, and it occurs to me that although the shelves were a relatively minor project, they are a big step in transitioning our house to our home.

Just as I finish the shelving, it becomes cold—the first real cold snap

As winter slides into spring, maple sap flows and a comforting ritual says welcome home.As Huck the cat looks on, the author heads to the second floor of the home that he and his family have built from scratch in rural northern Vermont. The stairs are trimmed in spalted maple boards that were pulled out of a friend’s barn.

It is pleasing to see our stores of food arranged in neat rows, and it occurs to me that although the shelves were a relatively minor project, they are a big step in transitioning our house to our home.

of the winter, an intense and clarifying cold, stripping life down to water, wood, and food, in repeating cycles. I make the animal rounds every two hours, flipping their troughs to stomp out the ice, then refilling from a bucket, calling to the cows as I do, because if they don’t come drink in the next hour the layer of ice atop the water will be too thick for them to break with their soft noses. Spittle freezes in my immature beard (shaving: another thing I’ve let go during my family’s absence) as I yell to the beasts, who seem not to appreciate my efforts in the least.

Before the cold snap ends, on a late morning when the sky is clear and the sun high, I walk the woods to the height of our land. Down low, just past the barn and brief expanse of pasture, the trees are dense and predominantly coniferous, but as I climb, the hardwoods increase in number, and soon I come to the sugar bush that composes the upper swath of our property. Here the understory clears, and the light courses past the leafless upswept limbs, casting long, serpentine shadows. The effect is almost cathedral-like.

or female or both. They lead me to the stream that runs almost the length of our property, and where the deer crossed, I turn onto the stream bed. The intense cold has created a layer of ice just strong enough to support my weight, so I walk directly down the stream’s center, following the bends, clambering over a big cedar that’s fallen from one bank to the other. From beneath the ice comes the sound of water folding and churning into itself. I break through once, but the pool is shallow, and the water does not breach my boot tops.

For a time, I follow a set of fresh deer tracks—a small animal, young dearth of snow will result in a truncated season, while others declare with unequivocal certainty that the conditions will have allowed the frost to settle deep into the soil, setting the stage for a record crop. Everyone agrees that the bare ground has made for easy tapping.

Near the bottom of our property, right before the stream flows through a large culvert to cross under the road, I hop onto land and trot through the orchard. I’m in a hurry now, feeling as if I’ve frittered away too much time, knowing the animals’ water will be frozen over yet again.

The cold does not last, and the arrival of March soon brings a stretch of ideal sugaring weather. For months, sugar makers have speculated about what the relatively warm and snowless winter will mean for the sap run. Consensus is elusive, with some claiming the

We’d promised ourselves not to sugar this year, to instead apply ourselves to the long list of tasks forsaken in last summer’s quest to get a roof over our heads. But then the days begin to stretch at both ends, and clouds of steam appear over neighboring sugarhouses, and, perhaps most threatening to our intentions, we step outdoors to feel the warm sun on our sallow cheeks.

“I think we should hang just a few buckets,” I say to Penny near the end of the first week of March. “A half

dozen or so. No more than 10.” We’ve already missed the early sap runs, but with any luck there will be a few more.

She agrees, and by that evening there are 40 buckets hanging from the sugar maples populating the fringes of the old skidder road that accesses the upper reaches of our land. When pressed, I am forced to acknowledge that 40 is a wee bit more than 10, but Penny says it’s near enough to consider it a mere rounding error. And anyway, I never was too good with math.

Since we don’t yet have a proper sugaring setup at our new homestead, we boil atop the wood cookstove, the windows of our unfinished home thrown wide to expel heat and steam. This year we’ve determined to make as much maple sugar as the season allows; we’ve made sugar in years past but only in small quantities, just enough to whet our considerable appetite for this traditional sweetener (for best results, sprinkle atop the homemade butter you’ve spread on a slice of toast fresh off the cast-iron top of the wood cookstove before the sun has cleared the eastern horizon). Besides, around these parts, maple syrup’s as common as mud on a lateMarch back road. But sugar? That’s as special as hen’s teeth.

We turn the first sap run into sugar, then the second, then the third. The fourth, too. And the fifth. Indeed, the trees just keep giving and giving; in the unofficial rural debate between deep snow and deep frost, the deep-frost argument has claimed the title by a country mile.

I gather the last of the sap on Sunday, April 17, carrying two near-tooverflowing 5-gallon buckets down the hill from the sugar bush and through the fenced-in pasture, the cows watching me in that skeptical way they always do. The old fool, at it again. Frodo, our 3-day-old bull calf, totters on spindly legs. He eyes me briefly before returning his attention to his mama’s swollen udder.

My arms ache from the weight of all that sap, and I will myself another 50 steps before stopping to rest. But I make it 55.

BY CHRISTINE WOODSIDE

BY CHRISTINE WOODSIDE

ne bright Monday afternoon, I step onto the Undermountain Trail below Bear Mountain, in northwest Connecticut. I climb east. The trail rolls mostly straight up, but because this is an old hill it feels smooth, with only one fast jog north, up steeper rocks. Traveling on a dirt and boulder track widened by many boots, I push upward through mountain laurels. I have come out today because I needed that periodic reconnection with the Appalachian Trail, the 2,190-mile forest highway that links Georgia to Maine. Once I reach the ridge, I will intersect the AT—which pulls me, like a force, back into the pilgrimage of my past.

At age 28, I walked the entire AT with my husband and our friends Phil and Cay. After about a month, our other hiker pals called us the Eight-Legged Thing; that is, it didn’t matter what our names were. I let the other six legs, so to speak, drag me along, and they and this trail gradually taught me that I could press on through all weather, pain, and exhaustion. I grew up here.

It’s been decades since my “thru-hike,” but I am still a changed person, one who pauses with surprise at water coming out of a tap. One who doesn’t care about rain or stale bread, who doesn’t wish for new carpeting, shiny cars, or cruises. Any point along the AT delivers that power. It pulls people back to simplicity. That makes the AT different from any other trail in the East. I don’t have time for more than a three-hour round trip today, yet I know that is enough for the AT to reconnect me.

At Riga Junction, I stare up at a giant signboard of faded and chipped light-green paint with routed yellow letters. A million people have gaped up at this sign:

Appalachian Trail South North

A world-famous walk leads back into the past— and deep into a hiker’s soul.On the Undermountain Trail with her poodle, Talley, Christine Woodside treks toward its intersection with the Appalachian Trail. RIGHT : Woodside and her husband, Nat Eddy, on the AT 30 years ago. COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR (VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPH) PHOTOGRAPHS BY JULIE BIDWELL

If I turn right and walk for two months or so, I will reach the placid rumble of Maine landscape and the giant massif Katahdin, where the trail ends. If I point my scuffed leather boots in the other direction for, oh, three months, I will stumble into former gold-mining country and onto the treed top of Springer Mountain in northwestern Georgia.

I turn right. I jig from rock to mud. As soon as I start, I have no name, send no texts, make no lists; I’m just leaping across a jumble of sediments that 450 million years ago tumbled this rock onto older marble and other material. Riga Mountain, as the locals call it, is Connecticut’s only example of this geologic drama. The first blackfly of the year heads for my eye.

Sitting quietly on a mount of rock that once was a fire tower foundation, a grizzled man in a red sweatshirt, hood up, stares out over the green fields and the Twin Lakes of Salis-

ing out anymore, so I decided I would prove this theory wrong. Of course I chose this rocky, open ridge up here near the Connecticut-Massachusetts border. But on the way in, I scared her: We’d left late, dark came, she wanted

bury, called Washinee and Washining. We get to talking. His name is Joel Blumert, he’s a guitarist and singer, and he’s been climbing the Undermountain Trail onto the AT and to the top of Bear Mountain for decades. Two years ago, he promised himself he’d climb it once a week for a year. At the end of the year, he bumped it to twice a week, indefinitely.

He’s met long-distance hikers up here a lot. I’m not surprised by how easily we talk. That’s the way it is on the AT. Pretension vanishes.

I meet again, in memory, all sorts of pilgrims I’ve encountered on trips up here.

Once I took a radio reporter up onto this ridge. She’d read that fewer hikers were carrying gear and sleep-

to stop, and I said no, we had to reach a certain campsite with a locking metal box that bears could not break into. That quieted her. It also cemented our friendship.

The next morning, we encountered a soft-spoken man followed by his Welsh corgi. “I find God out here,” he said.

We met a man and a woman from New Zealand thru-hiking the AT in honor of her 60th birthday. She asked why she wasn’t seeing more animals. I considered assuring her that hawks and fisher-cats and coyotes and newts and black snakes and the rest were hiding from the procession of hikers, perhaps only a few feet back from the trodden dirt. But I didn’t have to explain anything to anyone.

I repaired a relationship up here. I followed him, watching his strong legs in baggy blue gaiters fade in and out of fog, sliding over wet rocks. He picked me blueberries on the ridge. That night we camped near a group of boys who were part of a state program for juvenile delinquents. As their mentors stirred a vat of stew, the boys asked if they could meet our poodle, Talley. I could see that they were nervous out here, and they could see that I wasn’t.

I’ve been hiking on the AT for so many years that these memory companions make a crowd. But it doesn’t feel crowded. And I always forget what I have to do after I go back down the mountain. The sun begins to sink. I must go down. I jump from rock to rock.

The Undermountain Trail leaves Route 41 north of Salisbury, CT, and intersects the Appalachian Trail roughly 2 miles up; almost another mile on the AT leads to the summit of Bear Mountain.

The trail taught me that I could press on through weather, pain, and exhaustion. I grew up here.With the Appalachian Trail’s increasing popularity, the experience of hiking it has changed dramatically since Woodside’s 1987 trek. But its power to transport her is as strong as ever, she says.

With a satiny luster and sheen, our 10-11mm pearls resemble sought-after South Sea pearls with rich hues and substantial size. Beautifully crafted with dozens of genuine cultured freshwater pearls and a ne 14kt gold ligree clasp, our timeless strand delivers the look you desire at a price sure to delight.

$150 Signature Pearl Necklace with 14kt Gold Clasp 10-11mm pearls. 18" length. Also available in black item #469070.

Ross-Simons Item #469069

Free Shipping. To receive this special offer, use offer code: PEARL106

1.800.556.7376 or visit www.ross-simons.com/PEARL

On any list of today’s most prolific inventors, Dean Kamen’s name would be slotted near the top: The Bedford, New Hampshire, resident is the brains behind such things as insulin pumps and all-terrain electric wheelchairs. He is also, for good or ill, the man who gave us the Segway PT, the selfbalancing, battery-powered scooter that doubles as cuttingedge transportation and cultural punch line. After it debuted in 2001 with a $5,000 price tag, consumer sales flopped— as did some high-profile riders (President George W. Bush and Piers Morgan took tumbles early on; more seriously, in 2010 the company’s new owner, James Heselden, died after accidentally riding off a cliff). However, this so-called personal transporter found second life in police and private security fleets. Tour operators also recognized its potential, and these days more than 1 million Segway-mounted visitors can be seen puttering about cities worldwide—with helmets firmly fastened, of course. —Heather

Tourgee

If you’re tired of having your outdoor enjoyment rained on...baked out...or just plain ruined by unpredictable weather...

At last there is a solution! One that lets you take control of the weather on your deck or patio, while saving on energy bills! It’s the incredible SunSetter Retractable Awning! A simple...easy-to-use...& affordable way to outsmart the weather and start enjoying your deck or patio more...rain or shine!

The SunSetter is like adding a whole extra outdoor room to your home... giving you instant protection from glaring sun...or light showers! Plus it’s incredibly easy to use...opening & closing effortlessly in less than 60 seconds!

So, stop struggling with the weather... & start enjoying your deck or patio more!

For a FREE Info Kit & DVD email your name & address to freedvd@sunsetter.com

he weather is getting warmer every day, it seems, and there’s still plenty of good snow. But for some reason a lot of skiers have hung up their boots for the year. Why not take advantage of the sunshine, short lines, and off-season rates?

On February 21, 1985, it was 14 degrees with flurries at Killington Ski Resort in Vermont, and there were more than 11,000 skiers. On April 21, 1985, it was 40 degrees, and there were barely 2,000.

As for me, spring is now my favorite time. The sun comes out, the ice and lift lines disappear, and the amusement picks up, as the people who do show up take to wearing downright silly clothes.

Man-made snow melts slower than the real stuff, and Killington makes lots of its own. April snow is much different from February snow yet still affords great skiing. Some have likened April’s slopes to skiing on a Slurpee, which makes falls wet—but less bruising.

—Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1860–1935). Born in Hartford, Connecticut, Gilman is best known for her short story “The Yellow Wallpaper,” which since being published 125 years ago has become an early feminist classic. As both writer and lecturer Gilman dedicated herself to social reform—a natural calling, perhaps, for the grandniece of Harriet Beecher Stowe, whom Gilman joined in the Women’s Hall of Fame in 1994.

“Each generation of young people should be to the world like a vast reserve force to a tired army. They should lift the world forward.”—Adapted from “Spring Skiing Blooms Again,” by Rollin Riggs (March 1986)

Compiled by Julia Shipley

20th Anniversary that Good Will Hunting marks this year (released 12/5/97)

40

Estimated number of pages in Damon’s oneact play, written at Harvard, that inspired the screenplay

46 Combined ages of Matt Damon and Ben Affleck when they sold their screenplay

one

Number of movie scenes taken verbatim from Damon’s play (the scene in which Will meets psychologist Sean Maguire)

$600,000

Amount that Damon and Affleck each received for the script

$10,000

Amount that Damon and Affleck paid the friend who came up with the movie’s title

nine

Number of weeks spent filming Good Will Hunting

FOUR Number of years between the script’s completion and the first day of shooting

2

Number of Oscar wins (best supporting actor and best screenplay)

$10 million

Amount Good Will Hunting cost to make $226 million Amount it has grossed to date

ive in an old New England home long enough, and you’ll hear the rattle and roll of what sounds like a game of acorn hockey being played directly over your head—or, worse, the subtle sound of burrowing that, once you’ve focused on it, seems to echo incessantly through a quiet house. If squirrels have claimed your attic as their home, removal expert and wildlife biologist Bob Noviello of Windham, New Hampshire, is happy to offer some advice on how to evict your uninvited guests.

If a squirrel breaks into your house, Noviello says, it’s usually looking for a place to give birth. A female squirrel can have a litter of three or four babies twice a year: once in late summer, once in winter. Baby squirrels are weaned in about 10 weeks.

While squirrels are perfectly capable of building their own nests, they often prefer to look for an existing shelter to use. Like bats and other occasional home invaders, squirrels are able to detect minute variations in air pressure that indicate the presence of a gap or void in a structure. They love attics because they’re protected and warm, and there’s storage space

and often food. Attics offer lots of options for chewing, too, like beams, wires, ducts, and even pipes.

Squirrels typically don’t carry diseases that harm humans; however, they are known to carry potentially disease-bearing parasites. Squirrels also leave droppings, which pose health risks such as leptospirosis and salmonella. More urgently: Squirrels can create a major fire hazard if they chew on a home’s electrical wires.

Although there are people who claim to have had success with mothballs or repellents that use some kind of predator urine, Noviello says that none of these remedies will consistently drive squirrels away. Highpitched noisemakers don’t do much

there; it’ll try to find its way back to familiar territory and its food supply, exposing it to predators and traffic and all manner of distress. “Nobody likes to hear it,” Noviello says, “but often relocation kills the animal, one way or another.”

The best way to evict squirrels, Noviello says, is to close up all of your home’s potential critter entry points except one. At that last remaining exit, install an “excluder,” which is essentially a one-way door that will allow squirrels to go out but not to reenter. Be careful, though, not to “exclude” a mother squirrel before her babies have matured. And never close off all openings while squirrels are still inside: They’ll do damage attempting to get out, and may even end up in the living quarters of your home.

The good news, according to Noviello, is that if you can be patient, Mother Nature will do some of the heavy lifting for you. “Wait for them to raise their young in the attic,” he says, “and by late June or early July the heat will drive them out.”

“Little Friends”8”x10”$110 Ltd. edition print

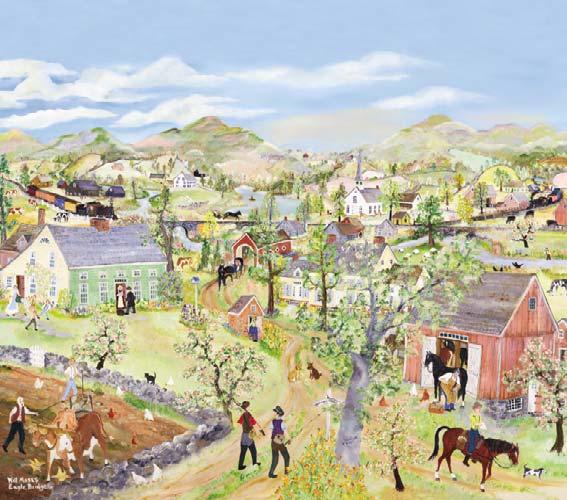

Plan a visit to Mt. Nebo Gallery. We offer a great selection of framed and unframed Will Moses art. Also books, cards and puzzles. Open 7 days a week. Closed major holidays.

either, and while a strobe light might annoy your furry visitors, they won’t be discouraged for long.

Poisons, on the other hand, may work—but they’re a bad idea for a couple of reasons. First, there are none that specifically target squirrels, so whatever toxic bait you decide to use may well be ignored by the squirrels and end up killing something else. Second, odds are high that if you do poison a squirrel, it will die in your house in a hard-to-reach place. “There are situations where extermination is appropriate,” Noviello says, “but only when it is done humanely by a professional.”

Many think that trapping and relocating the squirrels is the kindest strategy. Noviello disagrees, pointing out that any animal you relocate to the woods won’t simply take up residence

Getting squirrels out of your attic is step one. The ultimate goal, of course, is to keep them out. If the conditions that initially attracted them persist, your squirrels—or their friends— will soon return. To help prevent that from happening, replace any old screens on end vents and repair any areas of rotting wood. (Squirrels are very adept at finding even the smallest of entry points.) Seal up openings with material that will be unpleasant to chew through, like wire mesh or steel wool. However, don’t expect your furry friends to give up without a fight. “Once a squirrel has learned how great it is to live in a house,” Noviello says, “they can get pretty determined.”

ISBN 0-399-24233-5

Book$17.99 “Art

Puzzle$17.25

Getting squirrels out of your attic is step one. The goal, of course, is to keep them out.

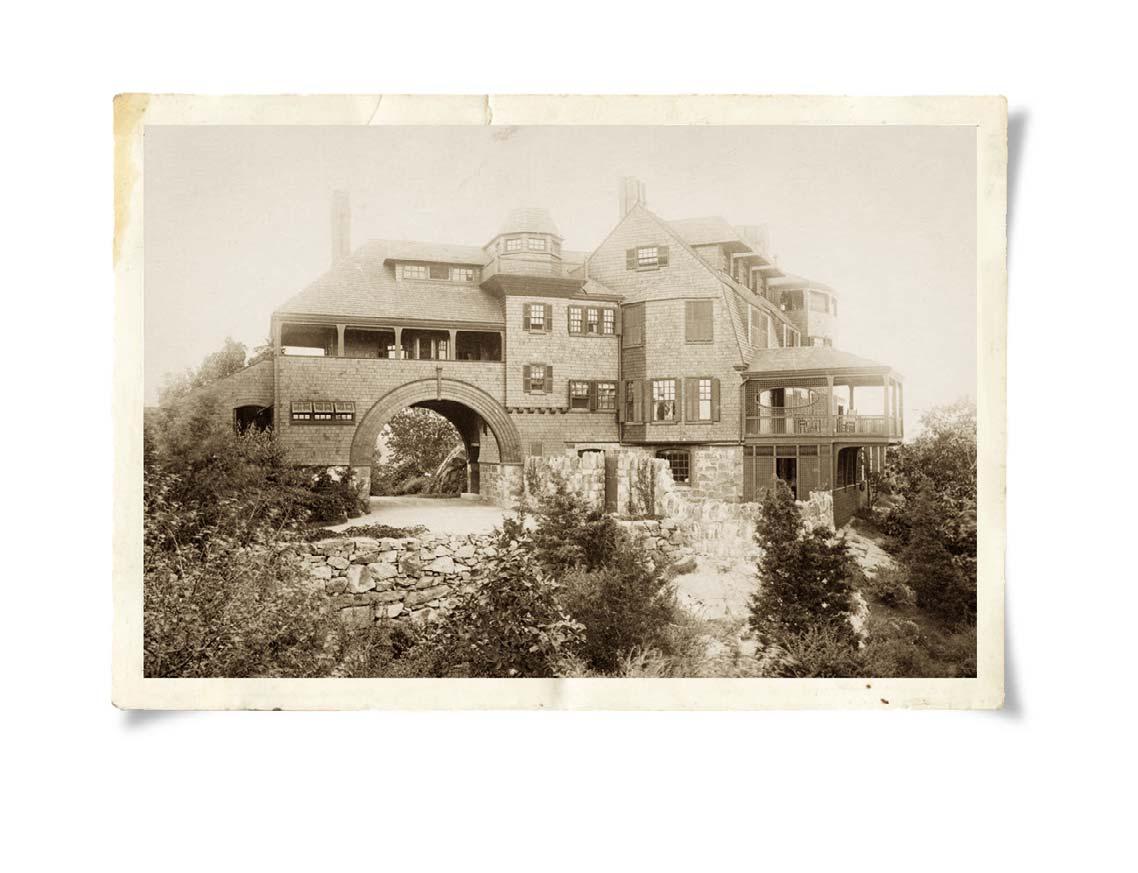

LEFT : The cozy “reading porch” outside the library of Jane Goodrich and James Beyor’s loving replica of Kragsyde (the original is shown inset at right).

There was only one way a young couple with little money could build a replica of a storied 19th-century Massachusetts mansion: They had to believe they could.

BY JANE GOODRICHBY BRET

The tale of Kragsyde—and what happened when a young couple first traveled to see the legendary shingled mansion in Manchester-by-the-Sea, Massachusetts—unfolds like an O. Henry short story. Except, that is, the events stretch out for 15 years, as Jane Goodrich and James Beyor re-create the turn-of-the-century beauty from scratch. In the afterword of Goodrich’s forthcoming novel about original Kragsyde owner George Nixon Black, The House at Lobster Cove , she tells her real-life story of encountering Kragsyde and then building the extraordinary replica now perched on Swan’s Island, Maine. —Ed.

oup de foudre , the French say, literally “bolt of lightning” but meaning love at first sight. How better to describe the instant when a chance meeting alters a life? For who can ever expect the sudden place, or glimpse, or turn of the page that will change everything?

I first met Kragsyde in an old box of books my father brought home. I was barely a teen, and paid little attention to the text or the title of the book, but the photographs and drawings gave me goose bumps. These were the most beautiful houses I had ever seen. Not impossible fantasy castles, nor the monotonous ranch-style structures of my own time. Shingled and playful and shaggy, like a favorite dog, full of mysterious rooms placed at odd angles. Fanciful windows I longed to peer from, deep cool porches, turrets with pennants flying from spires, promising endless summers. And the names: Grasshead, Sunset Hall, Wave Crest, Seabright. I studied them all, but even then my eyes could discern the masterpiece: Kragsyde. With its fantastic arch large enough to drive through, its beautiful stones, its romantic perch above the sea, this was the pinnacle. Completely beguiled, I clipped the photograph from the book and pasted it into a scrapbook. The sepia photo, held in my hands for the first time, was both a daydream and a seed.

Seven years later, in 1979, I was working in a sunny window in my college library. I was a sophomore, engaged to be married to a man who was already on his path to becoming a master builder. We often talked about the house he hoped to design and build for us. I was studying graphic arts and photography, but on that day I was awaiting the delivery of several books for an art history project. When the stack slid off the library cart, the top volume, The Shingle Style and the Stick Style , by Vincent Scully, had a familiar photo on its cover. Once again, the attraction was instant. Lightning had struck in the

by-the-Sea, in Massachusetts, to find Kragsyde. We became more excited about our own house plans as we drove, devising ways in which elements of the style could be incorporated into our own house. But our

Frances Burnett, that Kragsyde had been torn down in 1929. Sensing our disappointment, she offered to take us to the original site. Rounding the edge of Lobster Cove and seeing the bare cliff top where I had always envisioned the great house standing was like witnessing an extinction.

“The building plans can still be found in the Boston Public Library,” Ms. Burnett told us, consolingly.

In a small diner in Manchester, James and I ate lunch and commiserated. It was an easy first step to our mutual complaints that the world of 19th-century beauty was slipping away, to be replaced by the cheap and poorly crafted. It was frighteningly easier to come to our next wild thought. Why not rebuild Kragsyde? We knew how. It was a leap, a whim, an oath, an ambition, a naïveté, and a motif for the long marriage that followed.

The next day in the Boston Public Library, we encountered our first reality. We never thought about our jeans and longish hair, or our obvious poverty, when we entered the rarebook area where the plans for Kragsyde were housed. It never occurred

to us that simple interest would not be enough of a key to open the archives. But since we had no academic credentials, the vault remained closed. “You might want to call the man who donated the plans,” the librarian suggested.

Wheaton Holden, professor of architectural history at Northeastern University, was an expert on Kragsyde’s architects, Peabody & Stearns. As an educator, he was also no doubt accustomed to youthful exuberance and possessed the wisdom to foster it.

“We’re going to rebuild Kragsyde!” I told him over the phone when I reached him that day.

“I think that’s just great,” he replied.

In a matter of weeks he gave us copies of the plans and all the relevant photographs and drawings he’d amassed in his years of research. If Kragsyde was a seed planted in my childhood, it was Wheaton Holden who watered it.

By 1982, when I graduated, we’d saved as much money as we could, built a little model of the house, and bought an affordable seaside property in a too-small town in Maine. The daydream was about to be replaced by work—15 years of it, performed entirely by us, mostly on nights and weekends after coming home from our day jobs. We embraced it with diligence and no small dose of delight, using old techniques and traditional materials. As finances waxed and waned, the progress was sometimes slow, but each month brought advances and

Seeing is believing. Microsun™ lamps produce vibrant light that makes it easier for people to read, work on a laptop, or do needlework. Our lamps reduce glare and eye strain by delivering light that’s as natural feeling as the sun itself, so that you can spend more time doing the things you love. See what you’ve been missing with a Microsun lamp.

Why is Microsun the world’s best reading lamp? Just look under the shade. Our patented Microsun lighting system combines full spectrum rare earth metals with unique LEDs to help you see more vivid contrast and brighter colors. The Microsun light source is an electronically controlled Halide-LED system that uses a mere 90 watts of power, yet produces an incredible 7000 lumens! No other lamp features this revolutionary technology.

Patented** Halide/LED lighting system

Proprietary Microsun bulb

Uniquely brilliant lighting

Two SunStyle™ LED bulbs

Warm ambient lighting

Three light levels

Choose Halide, LED, or both

“My eyes aren’t what they used to be–this is like reading in sunlight!”

– Susan A., Long Valley, NJ

hard-won satisfaction in seeing the sepia photograph become tangible, as beautiful in our own century as it was in the century it was designed. We could look out the fanciful windows and walk under the fabulous, legendary arch, and we had built them ourselves.

Together with a college classmate named James van Pernis, Goodrich launched Saturn Press in 1986, producing greeting cards and stationery printed on antique presses. Her “day job” was paralleling the evening work of resurrecting traditional construction methods. At the same time, Goodrich found herself becoming increasingly fascinated with George Nixon Black, the original owner of Kragsyde.

To my 19-year-old self, George Nixon Black was no more than the original owner of Kragsyde, but as we rebuilt his house, I felt his ghost in every corner. It took 10 years of research on this elusive man to realize his life was as romantic and compelling as the house he occupied, and that his was a story worthy of being told.… The curious thing was how in searching for Black, I also found myself.

And in that seeking, she recalls, a bit of ephemera floated up from the past:

It came from the Manchester Historical Society, and from the pen of Frances Burnett, the docent who was the first person we met on our long journey. Buried in their archives was a copy of a letter she’d written in reply to someone who had sent her a newspaper article about our rebuilding of Kragsyde:

“I well remember this young couple who visited the Society back in 1979. I took them to the site of the old

house and told them it had been torn down. They had an old rattletrap car and I remember wondering how they could ever contemplate building such a mansion, but they have done it, and more power to them.”

In fact, we never went back to the Boston Public Library to see the plans; with the help of Wheaton Holden, there was no need. Yet even though I never laid eyes on those original elevations, I know every line of the house. How could I not, after building it, after laying the rafters of those familiar roof lines, and mixing the mortar for the enormous chimneys?

I know how the shingles travel the eaves, and where the snow builds up in those valleys. I know both its past and its present. The huge shadowed porch where Black played billiards, where I today hang a hammock, and the bow window where I find a sunny place for a blue and white bowl of flowers.

Adapted from the afterword of The House at Lobster Cove , a novel about George Nixon Black by Jane Goodrich, to be published this spring by Applewood Books. To learn more, go to houseatlobstercove.com.

are HANDMADE using the finest quality ingredients, and are fully cooked before packaging. One dozen delicious pierogi are nestled in a tray, making a one pound package of pure enjoyment!

You can get Millie’s Pierogi with these

Turns any day into an occasion – order today!

Our Timeline Growth Rules are hand crafted in Maine using traditional materials and methods continuously practiced since 1869. The rules are heirloom quality. Each 6ft 6in blade is milled from select Sugar Maple, markings are engraved into the blades and filled with pigment, and the inlaid ends are machined from solid brass.

Record your child’s growth as it happens directly onto the face of the rule and record milestones and special events on the back.

Your child’s formative years pass quickly. The growth and personal history recorded on the rule will become a symbol and celebration of your child, a memento made more precious by time.

A truly unique shower gift or birth acknowledgement.

$79 .00

Shipped free in contiguous 48 states

SKOWHEGAN WOODEN RULE, INC. (207) 474-0953

www.skowheganwoodenrule.com

Craig Altobello ( RIGHT) launched his woodworking career after taking a 1978 workshop with Thomas Moser; today he specializes in the painstaking art of marquetry, as seen on this page.

Craig Altobello ( RIGHT) launched his woodworking career after taking a 1978 workshop with Thomas Moser; today he specializes in the painstaking art of marquetry, as seen on this page.

BY ANNIE GRAVES

BY ANNIE GRAVES

slice of walnut wood suggests a dark mountain, outlined against a rippling sky of spruce. Chickadees rendered with bits of black acacia flit across a background of pale sugar maple. A heron poses, a study in

the sky, but if I

“This” is a 2-by-6-inch plank of common spruce from the local lumberyard in Peterborough, New Hampshire, where Altobello has lived for the past 26 years. He has shaved off a 1⁄16 -inch slice from this plank and, with the skilled eye and hand of a practiced marquetry artist, coaxed the illusion of a pale-streaked sky from the whims and tempests of nature embedded in the wood. Using its grain and color to best advantage, Altobello has created a sky from spruce.

“I cut each layer of the same piece of wood, sometimes to the third or fourth slice. Each layer is different— but I know it when I see it. That one,” he says, holding it out to me, “suggests ‘sky.’ My palette is the wood. I’m trying to tune in to create a painterly look.”

Once he’s chosen his background, Altobello sets to work sifting through bins of thin veneers to find just the right pieces to, say, craft a kingfisher’s head, or lay out the foreground in a mountain landscape, or create the delicate wings of a dragonfly. The colors, the textures, the varieties of wood are dizzying—a palette of infinite possibilities. Or perhaps he’s simply freeing scenes and images already inside the wood.

In theory, the art of marquetry is similar to that of inlay, with cutout pieces of wood being used to create pictures. In practice, the two are fundamentally different: Where inlay

features wood laid into carved-out trenches, a work of marquetry is created independent of a base, more like a puzzle of perfectly fitting pieces that is finally mounted on a piece of Baltic birch plywood that goes unseen. “Marquetry is more versatile,” Altobello explains. “With inlay you can rarely get the edges so perfect.”

Perfection and play seem equal partners in Altobello’s garage workshop. Tidy, well-organized bins of thinly sliced woods are arranged by color. The woods themselves can sound like bit players in a Wizard of Oz sequel: spalted sugar maple, cherry burl, baked poplar, wenge. The equipment is just as multifarious, from a lovely cherry hand plane made by Altobello to the large DeWalt scroll saw he calls his most important piece of equipment. Though imposing, this saw is “the opposite of intimidating,” he says. “It’s like a sewing machine.”

With it, he cuts the pieces that will all fall into place as a mountain scene or a bird caught midflight. From start to finish, an image can take up to a week to create.

He shows me a piece from the White Mountain series he’s working on, this one called Morning from Zealand Falls Hut , with Mount Kerrigan and Kerrigan Notch in the background. “I do a lot of hiking in the White Mountains,” he says thoughtfully. “I’ve hiked since I was child. It’s where my passion lies the most, so to do artwork based on hiking experiences is dear to me.”

Most of the mountain is rendered in shades of walnut that Altobello found in a lumberyard near Exeter. Creamy baked poplar from a lumberyard in Kingston suggests the mountain on the right. The silhouetted fir trees are made of wenge, a dark African wood with delicate zebra-

like stripes. (Though Altobello tends to favor local wood, when he does use exotics he looks for Forest Stewardship Council–certified pieces or scraps from other woodworkers.)

Is it a coincidence that Craig Altobello’s last name translates as “high beauty”? I’m still caught up in the unfinished mountain scene as he describes his latest idea for a series, depicting the old White Mountain high huts that are no longer there.

His eyes light up, and he’s off, riffling through one of the bins: “I’ve got a piece of wood over here....”

Prices vary: $125–$250 for 5½"x5½" autumn leaves; $375 for small birds; $4,000 for triptych. Altobello’s work is carried at the Sharon Arts Center, Peterborough, NH, and Artisans Way, Concord, MA. For more information, call 603-924-8522 or go to craigaltobello.com.

The timeless rope chain is once again in the trend spotlight. We’ve made the standard sublime by spiraling and twisting this classic for a fresh new look. Crafted in Italy by expert silversmiths, our exclusive design has a rich polished nish that highlights every curve.

$89 Italian Sterling Twisted Rope Chain

Sterling silver. 18" length. Graduates to 3 8" wide. Lobster clasp. Enlarged to show detail. Also available in 20" length $99.

Ross-Simons Item #873338

Free Shipping. To receive this special offer, use offer code: ROPE40 1.800.556.7376 or visit www.ross-simons.com/ROPE

Yankee likes to mosey around and see, out of editorial curiosity, what you can turn up when you go house hunting. We have no stake in the sale whatsoever and would decline it if offered.

o be honest, we didn’t expect much when we accepted an invitation from a young (judging by the photos she sent us) woman to visit the Connecticut River property she’d recently placed on the market. Maybe it was the price, $398,500, that put us off a bit. Most properties on the Connecticut that we know about are worth millions. There must be something wrong with hers, we thought. But her letter describing the trials and tribulations of building on a steep bank above the river back in 2004 was intriguing, and, well, we decided to have a look.

Our attitude totally changed the minute we pulled off Route 10 in Orford and into a parking area in front of a charming-looking contemporary eight-room Cape. The woman waiting for us on the cement sidewalk leading to the house introduced herself as Lynne Fenoff, our correspondent. As expected, she was young, at least to us oldsters.

Lynne led us onto a spacious, brand-new deck overlooking the river and then into a spectacular living/dining/kitchen area with artistically constructed stairs curving up to a bedroom loft. On the ground floor below was the expansive master bedroom and bath, and everywhere, on all three levels, were windows with sweeping views of the river. From several of these windows we noted a substantial grassy road running down to a dock, to which a small motorboat was tethered. So, despite our initial worries about the low asking price, there was certainly nothing wrong with this property. On the contrary, we absolutely loved it.

After hearing Lynne’s story, we had one question: Why in the world would she want to sell? Her answer: pure romance.

For the next hour or so we relaxed on the deck while Lynne told us how she came to create her riverside home. Obviously, it wasn’t always easy…

Lynne: “Growing up in Tewksbury, Massachusetts, I always loved being on or near water. Then, in my twenties, single and working two jobs, I purchased my first home—in Littleton, New Hampshire. It wasn’t on the water, but I could walk to the Connecticut River, and I bought my first kayak. As the years went on, I decided I would love to own property actually on the river and attempted many times to purchase land or a fixer-upper. But everything on the Connecticut was way beyond anything I could manage.

“Then one day I came across this 1-acre lot in Orford, and as usual I made an offer, expecting nothing. But much to my surprise, it was accepted! Shortly afterward I designed this home simply from pictures of homes I admired, and soon my sketches were ready for a builder. It would have large windows facing the river and be completely wheelchair-accessible for my brother-in-law, Ed Clark, who is paralyzed from a long-ago car accident. I wanted him and his wife, Karen, to be able to enjoy my home too.

“My friend, Lee Foster, a retired contractor, offered to build it at a price I could afford—if he could park his huge motor home here so he and his

wife could enjoy being on the river during the building process. All went well, but then came the difficult— and expensive—stuff. I needed to hire a plumber, a well contractor, an electrician, and so forth. The most challenging project was the building of a road down to the water suitable for my brother-in-law in a Jeep.

Building her own home allowed Lynne Fenoff to finally afford the riverfront property of her dreams ( ABOVE ) . She designed it herself— from the window-filled exterior to the modern, open interior ( INSET).We had to comply with a myriad of regulations of the state’s Connecticut River Shoreland Protection Act designed to avoid any erosion of the riverbanks.

“I somehow managed to persevere through it all and eventually sold my house in Littleton and made this my house. Almost every day after work [at various times, Lynne worked at Dartmouth College and nearby Rivendell Academy], I’d come home, take a paddle, and then relax on my dock or up here on the deck with perhaps a glass of wine, watching boaters cruise by. Occasionally I would see a deer swimming over to the opposite shore. It was heaven.”

After hearing Lynne’s story, we had one important question: Why in the world would she want to sell this house? Her answer: pure romance. “About two years ago, I happened to meet a special someone by the name of Ron Fenoff who owns and operates an excavation business. [Ron was away at work on the day of our visit with Lynne.] And guess what? We got married! I now work with him, doing his surveying and pretty much all his computer stuff. He doesn’t like computer stuff. And he persuaded me to live with him on the other side of the river, in Waterford, Vermont, in a mountaintop house he built that ‘looks like it fell out of the sky,’ as he says.”

Eventually, Lynne added, they’ll retire on land they’ve already purchased in Florida. Well, we said, when the Florida part of her story actually comes to pass, we’d love to mosey over to that mountaintop on the Vermont side of the river and write about a house that “looks like it fell out of the sky.”

Lynne promised she would stay in touch.

Celebrating life in New England at some of the region’s best events

YankeeMagazine editors, partners, and advertisers celebrated Yankee’s holiday issue’s“Christmas in Boston” cover story with an event at Island Creek Oyster Bar in Boston’s Kenmore Square and opening night of the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s Holiday Pops season on November 30th.

www.islandcreekoysterbar.com

www.bso.org

n Martha’s Vineyard, a late October cold snap strips away any illusions that the modulating Gulf Stream breezes will keep winter at bay forever. One week it’s roses and a last trip to the beach; the next week it’s frost. The gingerbread cottages at the Martha’s Vineyard Camp Meeting Association are mostly closed up now, as are the Oak Bluffs arcade and the Flying Horses Carousel that so recently thrummed with vacationing children. Circuit Avenue is eerily quiet, though Linda Jean’s is still serving up breakfast sandwiches and morning gossip for the real residents, the ones who stick around even after the winds turn bitter and damp.

I am here with the last of the tourists to capture these final beautiful days for our new public television series with WGBH, Weekends with Yankee (debuting in April; check local listings). It’s not quite dawn, and looking out my hotel window I see a thin line of orange light cracking the horizon over Nantucket Sound. A cold wind is whistling around the window frame, and I’m thinking I should’ve packed warmer socks.

Down in the lobby, I grab a Linda Jean’s sandwich from WGBH associate producer

Adrienne Rahn, who has made a 6:30 run to pick up breakfast for our small crew. Call time is 7, and we sip coffee and wonder how chilly it will be on the water. At about 7:30 we’ll board the 36-foot fishing boat Payback , out of Edgartown Harbor, to dredge sweet bay scallops from Cape Poge Bay. I’ll be cooking on the boat—or at least prepping raw scallops with citrus and chilies, in the style of an Italian crudo. So despite the poor sleep and thin socks, I’m buzzing. It’s another day of adventure, another day of making television.

Down at the Edgartown docks, we wait. This, I’m learning, is how TV works. We wait for the director, Rennik Soholt, to pre-interview the boat’s captain (Rennik wants us to meet him for the first time on-camera, so that it feels more authentic). We wait for Alan Weeks, the director of cinematography, to adjust his camera settings every time a cloud passes over the sun or to reset a shot from a different angle. It’s fine. We are filming in the most beautiful places in New England, destinations we mapped out over many months with the idea that the series would bring viewers the best of the best. It’s as if we’ve jumped into the pages of Yankee itself. And Richard Wiese, the show’s host—you may know him from his other show, PBS’s

Born to Explore —helps pass time by telling stories of hiking Kilimanjaro at age 11, of skiing to the North Pole, of living among Batwa pygmies in Uganda. I’m the food correspondent, so I’m filming just one segment per show, but he’s always there, ready to share a tip (“Once the camera starts rolling, don’t forget to take five steps before you start talking,” he reminds me— multiple times—yet I still forget).

Rennik signals that it’s time to board the boat. Already my feet are cold. The blood from my better-insulated upper

plus gloves, to layer over my down jackets, but it’s a whole other world among the 4-foot swells. And so, a new challenge: speaking with a steady voice when my body is convulsing with cold. The hair I so carefully styled at 6 a.m. is now a swirling rat’s nest at war with an elastic band. Still, this is heaven. Captain shows us how he drops his chain nets down to the bay floor, where they rake over the eelgrass beds where scallops thrive, leaving the grass mostly intact. Rick Karney, a shellfish biologist and director of the Martha’s Vine-

maturity. And when we haul up our first net full of sea life—crabs, whelks, clams, and a few scallops—he points out which ones are too small to harvest. We toss them back into the water.

After several runs—delayed by the need to move the crew to the harbormaster’s boat for a wide shot, to get the right interviews, to find the fertile beds—we have enough mature scallops to start shucking. Captain easily cracks open the shells and yanks out the viscera with a quick flip of a knife blade, leaving the cream-colored knob of adductor muscle to slice out and eat; I pop one into my mouth and taste a creamy sweetness that underscores

why bay scallops are called “nature’s gumdrops.” With about 40 shucked scallops in hand, I duck into the heated wheelhouse and carve a work space out of a 2-foot shelf. The waves make it difficult to slice evenly, and I have to brace one leg against a bench to stay upright. But I manage to juice two oranges and a lemon, grate some ginger, and arrange the scallops on a plate with the citrus sauce, a little oil, and a sprinkling of chilies, mint, slivered shallots, and sea salt. As crudo should be, the dish is a play on contrasting flavors and textures: hot and cold, silky and crunchy, sweet and sour. The heat from the chilies feels like sunshine. The guys gobble it up— all except Captain, who doesn’t eat scallops raw. Instead, he sets some aside to fry up on a single burner.

Food consumed, we turn around and make our way through the narrow Cape Poge Gut as the tide begins to ebb. Captain has another job to head out to that afternoon, and he’s already given us more time than he had to spare. Back on land, we remove our layers, marveling at all the heat reflecting off the sidewalk, a sensation we wouldn’t have noticed before. “It was a warm day,” Rick assures me. “This is just the beginning of the season.” I wouldn’t dare contradict him. Nor will I ever complain about the price of bay scallops again.

It is the great privilege of journalists to be able to enter the world of a stranger, even live in it for a day or two. Making Weekends with Yankee is a similar experience, only compressed into a high-octane joyride: Today it’s scalloping; tomorrow it might be making cheese in Vermont, baking clams in a remote cove on Mount Desert Island, or cooking on a windjammer in Rockland Harbor. I’m a New England native and have worked at Yankee for nearly 10 years. I’ve covered the region from so many angles, but in making this series I’ve fallen in love with it all over again. If we’ve done our job right, you will too.

The following recipes are just a sampling of the delicious dishes that we

prepared on-camera while filming Weekends with Yankee. For more information, visit the show’s website at weekendswithyankee.com.

TOTAL TIME : 15 MINUTES

H ANDS- ON TIME : 15 MINUTES

Crudo, which means “raw” in Italian, is a preparation in which pristine uncooked seafood is served dressed with citrus, good olive oil, and sea salt (additional seasonings optional). Unlike ceviche, in which the fish “cooks” in citrus juice for several hours, crudo is a last-minute preparation meant to highlight contrasting flavors. I

made this variation aboard the Payback , using scallops just pulled from the sea. As always, you should consume raw fish purchased only from trustworthy sources.

1 serrano chili pepper (or ½ jalapeño)

1 small shallot

Juice of 1½ oranges

Juice of 1 lemon

1 piece fresh ginger root, ½-inch long, peeled ½ pound fresh bay scallops, halved crosswise

2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

6 mint leaves, thinly sliced Chili flakes

Sea salt flakes

Cut the pepper in half and use a straw or chopstick to scoop out the inner seeds and membrane. Next, slice both pepper and shallot into paper-thin slices (a mandolin is a great tool here).

In a small bowl, whisk together the citrus juices. Grate the ginger root into the juice with a Microplane or other fine grater to extract the juice and some pulp, but not the root’s coarse fibers. Whisk to combine.

Divide the scallops among 4 salad plates. Pour the citrus dress-

ing around the scallops, then drizzle with olive oil. Sprinkle with pepper slices, shallot slices, and mint leaves. Sprinkle with chili flakes and sea salt to taste. Serve immediately. Yields 4 appetizer servings

I came by my next seafood feast with far less feigned machismo: While Richard boarded a boat in the early morning with Jay Baker of Fat Dog Shellfish, an oyster farm in New Hampshire’s Great Bay, I slept in

(there wasn’t room on the boat, alas). Around midmorning, we met up at Row 34, the Granite State outpost of the popular Boston oyster bar, where we prepared a fresh take on oyster stew with chef-owner Jeremy Sewall. While I’ll admit I’m a serious apple lover—I wrote a book on the subject— it never once occurred to me to combine apples and oysters. But Jeremy used diced apples as a garnish to delicious effect, adding fennel, thyme, celery, and onion as complementary notes. When he served up the stew in widerimmed bowls over toasted sourdough bread, I savored every bite, despite the total absence of suffering.

OYSTER STEW

TOTAL TIME : 40 MINUTES

H ANDS- ON TIME : 40 MINUTES

2 tablespoons unsalted butter

1 rib celery, thinly sliced, leaves reserved

1 fennel stalk, thinly sliced, fronds reserved

1 small onion, diced

¼ cup dry white wine, such as pinot grigio

2 cups heavy cream

1 bay leaf

3 stems fresh thyme

16 medium oysters, any variety, shucked, with ½ cup oyster liqueur (juice) reserved

Juice of 1 lemon

Salt and freshly ground pepper, to taste

4 slices of sourdough bread

1 tart apple, finely diced

In a medium sauté pan over mediumhigh heat, melt the butter and add the celery, fennel, and onion. Cook, stirring, until the vegetables are translucent, 5 to 6 minutes. Add the white wine and bring to a boil. Turn down the heat and simmer for 3 minutes, then add the cream, bay leaf, and thyme. Continue to simmer until the cream is reduced by almost half.

Add the oysters and their liqueur and bring the stew back up to a simmer. Warm the oysters through, 2 to 4 minutes. Remove pan from heat and let sit for 30 seconds. Season to taste with lemon juice, salt, and pepper.

Lightly toast the sourdough, then place each slice in a small shallow bowl. Spoon the oyster stew over the bread. Garnish with diced apple, fennel fronds, and celery leaves. Enjoy warm. Yields 4 servings.

Allison Hooper is well known among New Englanders who love great cheese and butter. Her company, Vermont Creamery, produces more than 4 million pounds of fresh and aged cheeses, crème fraîche, butter, and other dairy products. You may also recognize her from the pages of Yankee : Our May/ June 2016 issue told the story of Allison and her business partner, Bob Reese, and their newest venture, a model farm called Ayers Brook Goat Dairy, where they work to develop healthier goat breeds and best practices. The goal? To produce milk for the creamery and offer Vermont dairy farmers struggling with the volatile milk commodity market a sustainable alternative to raising cows.

When we visited Allison, we began the day at Ayers Brook, where we were greeted by a herd of 500 beguiling Saanens, LaManchas, and Alpines, then headed north to tour Vermont Creamery’s 14,000-squarefoot cheese-making facility in Websterville. Donning hair nets and sanitation suits, we moved from one

atmosphere-controlled room to the next, each calibrated to optimize milk culturing, curd development, and cheese ripening. Finally, we decamped to Allison’s hillside farm in nearby Brookfield—home to the original milk house where the company began more than 30 years ago— to make a delicious savory tart with her own products. We cooked together and shared stories. It was dark by the time we pulled the sweetsavory tart from the oven, a cozy fall evening enriched with a deeper understanding of what farm-to-table really means.

TOTAL TIME : 2 HOURS

H ANDS- ON TIME : 40 MINUTES

FOR THE CRUST

2 cups all-purpose flour, plus more for counter

2 sticks cold unsalted butter, cut into small cubes

¼ teaspoon table salt

2–4 tablespoons ice water

FOR THE FILLING

1 tablespoon salted butter

1 large Vidalia or other sweet onion, diced

12 ounces fresh goat cheese (chèvre)

¾ cup milk

1 large egg

2 teaspoons minced fresh sage or 1 teaspoon crumbled dried sage

1 teaspoon kosher salt, plus more to taste

lengthwise, seeded, and sliced into ¼-inch half-moons

½ cup dried cherries or cranberries

FOR THE GARNISH

Toasted pepitas

Heat oven to 350° and set a rack to the lower third position. Make the crust: In the bowl of a food processor, pulse together the flour, butter, and salt until the butter breaks down into peasize bits. Drizzle water into the bowl, and pulse until the dough just comes together—don’t overmix.

Turn the dough out onto a lightly floured counter and knead two or three times to bring it together. Form a ball and flatten it into a disk, then wrap in plastic and chill at least 1 hour (up to overnight).

Next, make the filling: In a medium frying pan over medium-low heat, melt the butter, then add the onion and cook, stirring occasionally, until nicely caramelized, about 20 minutes. Meanwhile, in a medium bowl, combine the goat cheese, milk, egg, sage, salt, and pepper. Stir until smooth.

Add the caramelized onion to the cheese mixture and stir to combine. Set aside to cool.

On a floured surface, roll the dough out to a ¼-inch-thick circle. Transfer the dough to a parchmentlined cookie sheet. Spoon the cheese filling onto the center and spread evenly, leaving a 2-inch border around

the edges. Layer the squash over the filling in concentric circles and sprinkle with dried cherries or cranberries. Gently fold the edges of the dough over the filling, pleating as you go. Transfer to the oven’s lower rack and bake until the squash is tender and the crust is nicely browned, 45 to 50 minutes. Top with a sprinkling of pepitas and cut into thick wedges to serve.

Yields 6 servings.

One of our most dramatic days of shooting happened in Acadia National Park on a lesser-known strip of the northern coast, between Eastern Bay