62 /// Autumn from the Top

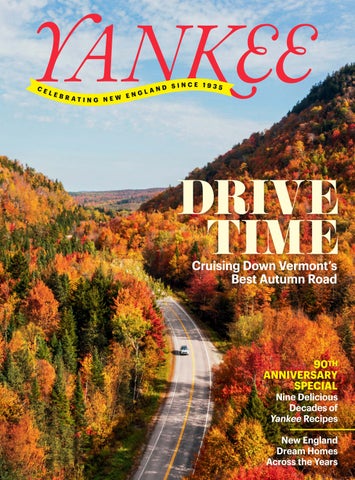

Starting just shy of Canada and unspooling down the length of Vermont, Route 100 drops leaf peepers into the heart of fall foliage. By Bill Scheller

72 /// Here in New England

Few have explored the soul of this region quite like former Yankee editor Mel Allen, whose new book says as much about the author as it does about his subject.

80 /// Window on an Island Soul

For Jamie Wyeth, the ability to create art relies on being left alone. Yet he continues painting masterworks in the company of his family legacy, his muses and memories, and his dreams. By Philip Conkling

84 /// The Garden That Keeps Growing

Michael and Kathy Nerrie believe that taking care of their own backyard makes for a better world. And what a backyard it is. By Mel Allen

Fall is the best time of year to visit South County, Rhode Island. September is still warm enough for a swim in one of our 20 public beaches. Catch a show or a movie at The United Theatre. Dine, stay or have a photo shoot at The Preserve’s Hobbit Houses. Visit the completed Thomas Dambo Troll Trail. Learn more at SouthCountyRI.com.

26 /// Property Values

For seven-plus decades, Yankee ’s wide-roving “House for Sale” column offered readers the chance to dream about moving to the country.

By Bruce Irving

32 /// Made in New England Coastal beauty entwines with artisan weaving traditions at Swans Island Company. By Virginia M. Wright

anniversary special FIRST LIGHT

38 /// Birthday Plates

As Yankee turns 90, we unearth recipes from the archives that have stood the taste-test of time. By Amy Traverso

46 /// Weekends in the Kitchen Fall mornings are sweeter when they begin with apple recipes inspired by our TV show, Weekends with Yankee. By

Amy Traverso

52 /// Weekend Away

A visit to Brunswick, Maine, shows how fall foliage only adds to the abundant local color in this bikeable college town. By Brian Kevin

60 /// View Points

Yankee ’s foliage expert, Jim Salge, makes the case for six less-expected spots for leaf peeping.

A decade before Yankee ’s launch in 1935, this tour company was already getting people revved up about visiting New England. By Ian Aldrich

anniversary special UP CLOSE

How this magazine’s founder built an empire of words, one clickety-clack at a time. By Jamie Trowbridge

112

LIFE IN THE KINGDOM

A father’s journey out west shows that sometimes the best part of an adventure is the chance to return home. By Ben Hewitt

ADVERTISING RESOURCES

[ COLE HAUSER × THE BARN YARD ]

AUTHENTIC POST & BEAM BARNS

Publisher Brook Holmberg

Senior Managing Editor Jenn Johnson

Executive Editor Ian Aldrich

Senior Food

Editor Amy Traverso

Senior Digital Editor Aimee Tucker

Travel/Branded Content Editor Kim Knox Beckius

Associate Editor Katrina Farmer

Contributing Editors Ben Hewitt, Rowan Jacobsen, Nina MacLaughlin, Bill Scheller, Julia Shipley, Kate Whouley

Editor at Large Mel Allen

Art Director Katharine Van Itallie

Senior Photo Editor Heather Marcus

Contributing Photographers Adam DeTour, Megan Haley, Corey Hendrickson, Michael Piazza, Greta Rybus

Director David Ziarnowski

Manager Brian Johnson

Senior Artists Jennifer Freeman, Rachel Kipka

Vice President Paul Belliveau Jr.

Senior Designer Amy O’Brien

E-commerce Director Alan Henning

Digital Manager Holly Sanderson

Marketing Specialist Jessica Garcia

Email Marketing Manager Eric Bailey

Customer Retention Marketer Kalibb Vaillancourt

E-commerce Merchandiser Specialist Nicole Melanson

Vice President Judson D. Hale Jr.

Media Account Managers Kelly Moores, Dean DeLuca , Steven Hall

Canada Account Manager Cynthia Fleming

Senior Production Coordinator Janet Selle

For advertising rates and information, email jdh@yankeepub.com or go to newengland.com/adinfo.

ADVERTISING

Director Kate Hathaway Weeks

Senior Manager Valerie Lithgow

Marketing Assistant Natalia Rivera

PUBLIC RELATIONS

Roslan & Associates Public Relations LLC

ESTABLISHED 1935 | AN EMPLOYEE-OWNED COMPANY

President Jamie Trowbridge

Vice Presidents Paul Belliveau Jr., Ernesto Burden, Judson D. Hale Jr., Brook Holmberg, Jennie Meister, Sherin Pierce

Editor Emeritus Judson D. Hale Sr.

CORPORATE STAFF

Vice President, Finance & Administration Jennie Meister

Human Resources Manager Beth Parenteau

Information Manager Gail Bleakley

Assistant Controller Nancy Pfuntner

Accounting Associate Meg Hart-Smith

Accounting Coordinator Meli Ellsworth-Osanya

Executive Assistant Christine Tourgee

Facilities Attendants Ken Durand, Bob Sardinskas

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Andrew Clurman, Renee Jordan, Joel Toner, Jamie Trowbridge, Cindy Turcot

FOUNDERS

Robb and Beatrix Sagendorph

NEWSSTAND

Vice President Sherin Pierce

NEWSSTAND CONSULTING

Linda Ruth, PSCS Consulting

SUBSCRIPTION SERVICES

To subscribe, give a gift, or change your mailing address, or for any other questions, please contact our customer service department:

Mail: Yankee Magazine Customer Service PO Box 37900, Boone, IA 50037-0900

Online: newengland.com/contact-us

Email: customerservice@yankeemagazine.com

Toll-free: 800-288-4284

Yankee occasionally shares its mailing list with approved advertisers to promote products or services we think our readers will enjoy. If you do not wish to receive these offers, please contact us.

Yankee Publishing Inc., 1121 Main St., PO Box 520, Dublin, NH 03444 / 603-563-8111 / editors@yankeepub.com Printed in the USA at Quad Graphics

Hosts Amy Traverso, Richard Wiese

Directors of Photography

Corey Hendrickson, Jan Maliszewski

Editor Travis Marshall

Executive Producer Laurie Donnelly

Senior Producer Mercedes Velgot

Associate Producer Nora Kirrane

Sponsors

Maine Office of Tourism • Massachusetts Office of

and

New Hampshire Division of Travel and Tourism Development • American Cruise Lines • Country Carpenters • Grady-White Boats • New Smyrna Beach Area Visitors Bureau

Follow Lewis and Clark’s epic 19th-century expedition along the Columbia and Snake Rivers aboard the newest riverboat in the region. Enjoy unique shore excursions, scenic landscapes, and talented onboard experts who bring history to life.

Cruise Close To Home

Freedom 345

LIMITED-EDITION NEWSLETTER! Stunning colors, festive harvests, small-town celebrations—New England’s foliage season packs a lot into its short run. And so does our brandnew Fall Newsletter. Sign up, and each week we’ll send you an up-to-the-minute snapshot of this spectacular season:

■ Exclusive foliage reports from Yankee expert Jim Salge

■ Inspirational fall destinations in every New England state

■ Delicious seasonal recipes & can’t-miss regional events

But hurry! Just as with fall foliage, you won’t want to miss a bit of this special newsletter before it ends. To sign up, scan the code at left or go to: newengland.com/fallnewsletter

From classic novels and children’s books to memoirs by Yankee contributors and New England cookbooks, the Yankee Bookshelf is an editor-curated collection of the very best writing that our storied region has to offer. Discover your next great read at: store.newengland.com/bookshelf

Great Pumpkin Recipes

One of fall’s most versatile ingredients takes center stage in 10 sweet and savory recipes to brighten any meal. newengland.com/pumpkin

40 Fall Farmers’ Market Destinations

Turning leaves means harvest time, which finds New England farmers’ markets at their colorful autumn best. newengland.com/fallmarkets

Follow in our experts’ footsteps as they explore both hidden and well-known fall destinations, and get their top picks for where to go and what to do. newengland.com/fallweekends

Foliage Train Tours

Make tracks for a leaf-peeping thrill of a lifetime on New England’s historic railroads. newengland.com/foliagetrains

Want more Yankee? Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and Pinterest: @yankeemagazine

Our hotels range from luxurious and elegant to charming and retro. Witham Family Hotels offers the perfect lodging options for your adventures in Acadia National Park.

like to think it was a forward-looking Yankee reader who ended up buying the 85-acre lakeside farm in Warwick, Rhode Island, featured in our May 1939 issue for a mere $2,250. Two decades later, a fast-acting subscriber did scrape together the $3,500 for the ocean-fronting home on the Maine island of Matinicus described as being set on “eight acres of spruce, lilac bushes, and an aged apple orchard.” And after Yankee wrote in May 1981 about a sprawling piece of Maine’s moose country that included eight sporting camps (asking price: $150,000), more than 90 readers from 26 states made inquiries—among them, the man who eventually bought it.

These were just a few of the many bargains I unearthed in Yankee ’s archives during the research for Bruce Irving’s tribute to our long-running “House for Sale” column [p. 26] and the big dreams it inspired. Of new beginnings. Of a change of scenery. Of chucking it all and moving to the country. Along with senior food editor Amy Traverso’s

this issue’s “Weekend Away” [p. 52], and reports that he’s really looking forward to his next one.

A photojournalist long based in Portland, Maine, Rybus was in the process of moving to a more rural home when she visited New Hampshire’s Michael and Kathy Nerrie [“The Garden That Keeps Growing,” p. 84]. “They told me how they had discovered their own creative practice in gardening and land work,” she says. “That resonated deeply as I did trail work this winter and built my first major garden this spring.”

nine-decade-spanning collection of recipes [p. 38] and an excerpt from former editor Mel Allen’s new anthology of his best Yankee stories [p. 72], it anchors this anniversary issue.

Ninety years. That kind of longevity doesn’t happen by accident. As New England has changed and evolved, so has Yankee. Today it is not just a magazine; it’s also an awardwinning public television show, Weekends with Yankee, and a website, NewEngland.com, and social media channels and newsletters. And on it goes. Yankee now produces more stories and reaches a wider audience than it has at any other time since its founding in September 1935.

Yet even as we engage with our readers and viewers in ever more dynamic ways, Yankee ’s role in the life and culture of New England remains the same. That bond was deeply felt as I sifted through the archives—along with my regret that in April 1962 nobody in my family ponied up the paltry $15,000 for a 23-acre Nottingham, New Hampshire, property that included “one of the best panoramic views” in the region. —Ian Aldrich, executive editor

Of his fall foliage assignment [“Autumn from the Top,” p. 62], Parini says: “Route 100 has always held a special place for me—it winds through so many of the landscapes and towns I grew up exploring. Photographing it during peak foliage season felt like coming full circle.” Parini grew up in Weybridge, Vermont, and now lives there with his family, working as a commercial and editorial photographer.

met more than 30 years ago, Conkling could see that the artist “was an islander by disposition, as was I.” Conkling cofounded Maine’s Island Institute with Peter Ralston in 1983 and is founding publisher of Island Journal and the author of Islands in Time

In the comfort of our well-appointed fleet, enjoy the most personalized exploration of the Great Lakes region on a 7 to 15-night journey. Led by our engaging local guides, immerse yourself in the rich history and vibrant culture of charming harbor towns and admire the wonders of nature up close.

Explore Well ™

A decade before Yankee’s launch in 1935, this tour company was already getting folks revved up about visiting New England.

BY IAN ALDRICH | ART BY ANDREW DEGRAFF

e were on the hunt for foliage. It was early October, and for several days our group of 40 or so had motored through New England on a bus tour with Connecticut-based travel company Tauck. There had been bucket-list stops along the way—Fenway Park, the Mark Twain House, a Vermont sugarhouse—but the autumn color we were seeking had proved elusive. And depending on who we talked to, local chatter made us feel as if we were either a million miles from our destination or oh so close

“I live 45 minutes north,” one Vermont store clerk told us. “And up there the leaves are amazing.”

Tamping down the foliage anxiety was the Tauck team itself, a guide-and-driver duo who never doubted we’d finally catch the color. Experience helped: Not only had they presided over decades of autumn trips, but they also worked for a company that had been leading these kinds of trips since 1925. Roads changed, sights came and went, but October, we were promised, always delivered the color.

In Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom, we got the first whiff that maybe we were on the verge of something special. It wasn’t just the big maples or hashtaggable town centers. There was a nip in the air. Wood smoke curled from chimneys. It felt like fall. Even better: We were headed to New Hampshire and higher elevations.

At the sugarhouse stop in Vermont, one of my fellow travelers emerged from the evaporator room, practically breathless. “I was speaking with a fella who was just up north, and he said the White Mountains are on fire,” he said, opening his hands wide.

At lower left, a Tauck foliage-tour bus in its familiar yellow “Yankee” livery (no relation to this magazine, incidentally, but we approve) plunges into the heart of New England leaf peeping in this 2017 Yankee illustration.

Tauck passengers in 1925, with the company’s advertised “spacious

TAUCK’S ORIGIN STORY IS AN UNUSUAL one. The company’s founder, Arthur Tauck, was an idea man with an entrepreneurial bent. Trained in the banking business, he was in his mid-20s when he struck out on his own with a patented design for a coin tray, crisscrossing New England to sell his invention to banks.

But it was at a scenic lunch stop on the Mohawk Trail in North Adams, Massachusetts, in the fall of 1924, where Tauck observed an absence—and maybe a new opportunity. A glaring uniformity defined the restaurant’s patrons: They were all traveling salesmen like himself. Even with the fall colors out in full effect, there was not a single tourist in sight. Tauck wondered, Would that change if they had an expert guiding their way?

The next summer, the 27-year-old rented a Studebaker wagon and launched his first trip: an ambitious six-day, 1,000mile itinerary on largely dirt roads that cut through three New England states and included side routes into New York and Canada. Six customers paid $69 each to join in the sprawling trek. At a time when most Americans didn’t even own a car, Tauck’s tour was a revelation. Upon returning home, his guests spoke glowingly about the trip, and inquiries about future itineraries soon poured in. By 1929, Tauck had a new business. He bought a fleet of buses, hired staff, and developed several different New England itineraries that showcased the region’s

premier hotels, cultural destinations, and local history. One century after its founding, Tauck now boasts a global footprint. Still family-owned, the company operates out of a gleaming glass-and-steel building in Wilton, Connecticut, where it oversees more than 170 different trips across all seven continents and in 70-plus countries. There are African safaris, land journeys through Israel and Jordan, and an 18-day excursion through Nepal and northern India. Over the past decade and a half, Tauck has partnered with filmmaker Ken Burns to produce a series of guided itineraries through the American West and elsewhere that explore the themes of Burns’s films.

“We truly believe that travel is a force for good in the world,” says Jennifer Tombaugh, Tauck CEO and the first non-family member to head the company. “I remember hearing from one of our guests who had traveled with us to Egypt for the first time about how moved they were at what they saw. Yes, we come from different religions, different cultures, and different backgrounds, but ultimately we have this shared humanity. Travel reminds us of that.”

That holds true for the New England trips, too. Even as Tauck has greatly expanded its lineup over the decades, this region is still at the center of what it does. Every year the company offers four distinct tours—54 trips altogether— including a 12-day “grand” excursion that

would have made Arthur Tauck proud. There are covered-bridge photo ops and general-store stops, of course, but also visits to museums and historical properties. On my tour we visited Ken Burns’s Florentine Films studio in Walpole, New Hampshire. In Vermont, we sat for a lecture on the history of the New England landscape. In Boston, we spent part of an afternoon on a foodie tour of the city.

Then there’s the unexpected pleasure of traveling with a group of strangers. On many vacations, we are often solo actors. We eat at the same restaurants as other travelers, swim in the same pools, go back to the same kinds of hotel rooms. Typically, there’s little engagement with strangers—there’s no incentive to engage. When you’re thrown together with a bunch of unfamiliar faces on a bus, however, there’s no choice but to socialize. You’re exploring together. You’re seeing places and meeting people for the first time together. There’s a shared experience to draw from, and that can also deepen the meaning of what you’re seeing.

IT’S AT THE SUGAR HILL MEETINGHOUSE, on the western edge of New Hampshire’s White Mountains, that we finally find autumn. All the boxes are checked: The white clapboard meetinghouse decked out with pumpkins and cornstalks. The near-peaking maples on the front lawn. The blue-sky day. The tidy farmhouse across the street. Nothing—not even the private tour of Fenway Park—elicits the same excitement in my fellow travelers as this tiny town green.

I remain in my bus seat and watch the others take in the moment. One couple does a quick dance, several people pose for photos with the trees, one woman actually hugs a maple. On the steps of the meetinghouse, a round of selfies is produced. There is euphoria in the air.

Following a solid 10 minutes of picture taking, the crew then files back onto the bus. “That’s the best selfie I’ve ever taken,” says a woman from Florida, pausing in the aisle to look at her phone.

She laughs with approval. “That’s so good.”

Autumn in New England is pure magic. From fiery sugar maples to golden hills, there's no better way to witness the season's transformation than on the road-especially with charming inns along the way. Let the Boutique Inn Collection guide your ultimate fall foliage road trip, where every stop invites you to slow down, savor the scenery, and experience true New England hospitality.

Autumn in New England is pure magic. From fiery sugar maples to golden hills, there's no better way to witness the season's transformation than on the road-especially with charming inns along the way. Let the Boutique Inn Collection guide your ultimate fall foliage road trip, where every stop invites you to slow down, savor the scenery, and experience true New England hospitality.

Plan your fall foliage escape today at BoutiquelnnCollection.com and JacksonlnnCollection.com.

Plan your fall foliage escape today at BoutiquelnnCollection.com and JacksonlnnCollection.com.

COLLECTION

Begin your journey in the heart of the White Mountains at Thayers Inn. With views of golden treetops lining Main Street, this historic inn offers a cozy base for exploring nearby Franconia Notch and the Kancamagus Highway-two of the most iconic foliage destinations in the region. In the evening, return to timeless charm and small-town warmth.

Begin your journey in the heart of the White Mountains at Thayers Inn. With views of golden treetops lining Main Street, this historic inn offers a cozy base for exploring nearby Franconia Notch and the Kancamagus Highway-two of the most iconic foliage destinations in the region. In the evening, return to timeless charm and small-town warmth.

Wind your way back into New Hampshire and land in Jackson Village, where The Inn at Thorn Hill sits perched above the mountains. The views? Unbeatable. The wine list? Award-winning. Treat yourself to a couple's massage in the spa, then watch the sunset paint the hills in gold from the comfort of your room.

Wind your way back into New Hampshire and land in Jackson Village, where The Inn at Thorn Hill sits perched above the mountains. The views? Unbeatable. The wine list? Award-winning. Treat yourself to a couple's massage in the spa, then watch the sunset paint the hills in gold from the comfort of your room.

Cross the Connecticut River into Vermont's Northeast Kingdom, where Rabbit Hill Inn welcomes you with candlelit charm and sweeping views. This adults-only inn is the epitome of fall romance. Take a country drive through vibrant hills, stop by roadside farm stands, and return to luxurious comfort, a gourmet dinner, and the flicker of your in-room fireplace.

Cross the Connecticut River into Vermont's Northeast Kingdom, where Rabbit Hill Inn welcomes you with candlelit charm and sweeping views. This adults-only inn is the epitome of fall romance. Take a country drive through vibrant hills, stop by roadside farm stands, and return to luxurious comfort, a gourmet dinner, and the flicker of your in-room fireplace.

Experience the charm ofJackson, NH, with access to all three of our boutique inns-featuring spa treatments, fine dining, and seasonal experiences. Our complimentary shuttle makes it easy to explore them all.

Experience the charm ofJackson, NH, with access to all three of our boutique inns-featuring spa treatments, fine dining, and seasonal experiences. Our complimentary shuttle makes it easy to explore them all.

Just down the road, The Inn at Whitney's Farm offers a cozy retreat on 12 private acres. Fall foliage hikes start right outside your door, and the slower pace ofJackson lets you really soak it in. This is your go-to for crisp air, forest trails, and evenings by the fire.

Just down the road, The Inn at Whitney's Farm offers a cozy retreat on 12 private acres. Fall foliage hikes start right outside your door, and the slower pace ofJackson lets you really soak it in. This is your go-to for crisp air, forest trails, and evenings by the fire.

Wrap up your journey at Christmas Farm Inn, where families and couples alike can relax and recharge. Enjoy hearty New England fare, unwind in the full-service spa, or take in the vibrant colors from the Adirondack chairs on the lawn. It's the perfect place to end your foliage tour on a high note.

Wrap up your journey at Christmas Farm Inn, where families and couples alike can relax and recharge. Enjoy hearty New England fare, unwind in the full-service spa, or take in the vibrant colors from the Adirondack chairs on the lawn. It's the perfect place to end your foliage tour on a high note.

Autumn feels a bit like nostalgia: achingly beautiful yet familiar and comforting, like time is slowing down for you to savor every color, sound and serene moment. This is when Maine transforms into a masterpiece of vivid beauty. Quiet, misty mornings give way to golden-hued afternoons, inviting scenic drives, long hikes and field trips to nearby farms.

Meander through Maine’s mountain towns and seaside villages alive with the energy of harvest season. This is where craft breweries and cocktail bars harness local flavors, from orchard-fresh ciders to small-batch spirits infused with wild herbs, and lauded chefs showcase the best of fall ingredients: buttery lobster, plump mussels, creamy potatoes and just-picked heirloom vegetables. This is where the raw beauty of nature shapes our very experiences—and the stories we bring home.

As leaves crunch beneath your boots and crisp air carries the scent of woodsmoke and fallen leaves, autumn in Maine casts a cozy kind of spell. Here, the pace is unhurried, and the pleasures are grounded in simplicity. Start your morning with a leisurely drive through forests awash in fiery reds, golden yellows and deep purples, set against a backdrop of evergreen pines and cobalt skies. Hike to panoramic overlooks, pick your own apples in sun-dappled orchards and pull over at farm stands for freshly pressed cider and cinnamonsugar doughnuts. Follow the call of the coast to experience its quieter, more contemplative beauty— rugged vistas, salt-scented breezes and weather-worn lobster boats returning with the day’s catch.

Maine’s regions take on a new glow in autumn, o ering unforge able ways to experience the season.

GREATER PORTLAND & CASCO BAY

This foodie haven celebrates fall with warming cocktails, artisanal pastries and award-winning farm-to-table dining. Don’t miss the vibrant arts and maker scene, on display throughout independent boutiques and galleries.

THE MAINE BEACHES

wander through amber woods and explore 200 waterfalls framed by blazing foliage.

Mount Katahdin and Moosehead Lake o er awe-inspiring hikes to take it all in.

MAINE LAKES AND MOUNTAINS

Mirror-like glacial lakes, sky-high summits and incredible wildlife beckon. Explore several scenic byways to discover hiking trails, mountain villages and perfect picnic spots.

MIDCOAST & ISLANDS

Autumn quiets the coast, revealing its reflective beauty. Explore artists’ studios, indulge in freshly caught seafood by the shore and wander coastal trails by foot or bicycle.

The end of summer swaps sunbathers for solitude along the sandy shores. Take a brisk walk by the surf and learn about local history and culture in eclectic museums, antique shops and working waterfronts.

THE KENNEBEC VALLEY

Fall festivals, harvest markets and spectacular drives along the Kennebec River showcase this region’s charm. Hike amid fiery foliage and then explore welcoming riverfront towns.

DOWNEAST & ACADIA

Acadia National Park is ablaze with fall color. Quiet hikes, mountaintop overlooks and boat tours o er stunning sights, while local inns welcome leaf-peepers with warmth.

How Yankee’s founder built a world of words, one clicketyclack at a time.

At its start in 1935, one man and one typewriter was all there was of Yankee.

Robb Sagendorph founded the magazine in an act of frustration. He wanted to write for his favorite publications, but his ideas for articles were rejected. So, he tore out the pages of those magazines and used them to insulate the walls of the one-room studio he built next to his home in Dublin, New Hampshire. And if he couldn’t write for other magazines, he’d sit down at his typewriter in that little building and start his own.

He had a good idea for a magazine. Sagendorph worried that the growing homogenization of life in America at that time would overwhelm the characteristics of New England he trea-

sured—“its independence, its wisdom, its humor, and its resourcefulness.” Celebrating the values that make New England distinctive is what Yankee was and is all about.

There was a lot to type. Letters to friends and family, asking for support. Letters to local authors, inviting them to submit articles. Typing and retyping manuscripts, preparing them for typesetting. Volume 1, number 1 of Yankee featured works of fiction and poetry, articles about industries in New Hampshire, instructions for contra dancing (“General grace and willowness are to be sought after as the dances are anything but slip shod”), the script for a short play, and a rambling screed titled “Dreams and Observations” with “The Collector” as its byline.

Today, magazines are designed to be visually engaging. But in 1935 it was all about the words. Sagendorph needed more people—and more typewriters— to produce the second issue of Yankee And after that, even more people and typewriters.

Business success was a long time coming. Sagendorph could never have made it without the family money provided by his wife, Beatrix, a talented artist who also produced Yankee cover art and illustrations. Yet it was still all about the words, pounded out on typewriters until one day in the mid-1980s when Yankee ’s photo editor, of all people, brought the first word processor to the office. Yes, the computer age had arrived—but Sagendorph’s enduring vision would continue. —Jamie Trowbridge

Discover the best of New England in Foxborough, Plainville, and Wrentham — just 30 miles from Boston and 20 miles from Providence. Whether you’re cheering at Gillette Stadium, testing your luck at Plainridge Park Casino, or finding deals at Wrentham Village Premium Outlets, there’s always something more to explore. And that’s just the beginning. Hike scenic trails, browse charming boutiques, enjoy farm-fresh dining, or unwind in cozy local inns. From outdoor adventures to indoor escapes, FPW invites you to linger, laugh, and make the most of every moment. Your getaway is closer than you think. VisitFPW.com Visit FPW. Stay a Little Longer...Play a Little More!

When

an exclusive sneak peek at the property and garnered national media coverage.

For seven-plus decades, Yankee’s wide-roving “House for Sale” column offered readers the chance to dream about moving to the country.

BY BRUCE IRVING

Starbucks on every corner, a new car in the driveway, an embarrassment of entertainment options out on the town—the pleasures of urban and suburban America are hard to ignore or resist. But every so often, the heart longs for a dirt road and a star-filled night, and one partner turns to the other and says, “Honey, have you ever thought of chucking it all and moving to the country?”

That’s how the “House for Sale” column got its hooks into Yankee readers, sinking deep into this kind of blacktop discontent. It was a part of the print magazine from the early days up until 2023, with hundreds of editions churned out over its long run. That’s a lot of dreams fanned.

The basic concept has been in Yankee ’s DNA from the very start. Founder Robb Sagendorph, though he may have looked the part of “a tall, lean Yankee,” as his New York Times obituary put it, was no rural character himself. He was born in Newton Centre, Massachusetts, the son of a Boston steel manufacturer. After graduating from Harvard, he spent seven years in the steel business in Boston and New York, until moving to Dublin, New Hampshire, to become a farmer and freelance writer. As the Times reported, “He succeeded at neither.” Instead, he started a magazine in 1935 dedicated to limning the rural life.

Even before the column began, Yankee advertised rural properties: In 1939, for example, a “Handsome Home, Equipt Farm” located 55 miles outside Boston came with 110 acres and “13 cows, heifers, bull, machinery, 1½-ton truck, milk route, etc.” for $4,400. For a time in the ’90s, an ad repeatedly exhorted readers to “Escape to an island off the coast of Maine.” But “House for Sale” took all that country dreaming to another level. In the May 1981 issue, the column featured nine acres, a store with an apartment, and eight sporting camps, all under the name Kokad-jo, “up in Maine’s moose country.”

Who were the seekers, these aspiring escapees, that responded to such descriptions? A 1985 update on the Kokad-jo property reported there had been 93 inquiries from 26 states, including seven from California. The first person to call—the day the magazine hit newsstands—was apparently inebriated, according to the seller. A pair of folks from Washington, D.C., said they wanted to move to Kokad-jo because “we are a couple of burnt-out executives.” The man who ultimately bought it had

FROM TOP: The March 1971 issue featuring the entire 19th-century mill town of Harrisville, New Hampshire, for sale; the first-ever “House for Sale,” printed in the April 1950 issue and starring a four-bed, three-bath home in Groton, Massachusetts, for $16,900.

bicycled through the area with his son a year before and thought how wonderful it would be to live there. The day before he arrived in Maine to buy Kokad-jo, he walked into his boss’s office at the Con Edison plant where he’d spent decades working on public relations, and he quit. “You don’t just sever yourself from a corporation after 25 years like this,” said his boss. “You don’t, huh?” he replied. The man and his son embraced and danced for 10 minutes after the papers were signed—the best he’d felt in 48 years. “Free,” he said. “Free at last.”

Through the years, “House for Sale” featured a number of properties that had already been through round one of dreamer-occupation, the sellers’ descriptions of how they found it and what they did to it serving as inspiration, almost daring the next owner to continue the dream. In the July 1990 column (“Chasing Sunbeams at ‘Hidden Wells’”), we meet Bill and Betty Noble at their 1729 Rhode Island Colonial, which, when they first saw it in 1958, was full of cats and had a first-floor ceiling so sagging

that a chandelier was within a foot of the floor. They bought it, and 22 acres, for $10,000 and proceeded to fix it up, more or less by themselves, in a process they describe in harrowing detail (digging silt out of the bottom of the well; dodging snakes; pulling down plaster; modernizing the heating, electrical, and plumbing systems; restoring the grounds; working in the first year “until midnight or beyond”). They even put in a pool. Did they have any advice for young couples thinking of restoring an old house? the writer asked. “Do it!” they said. Unspoken but implied: Or just buy our place for $499,000 and avoid all the grunt work.

“Do it!” was not the answer the magazine got when it paid a follow-up visit to the first-ever “House for Sale,” published in April 1950. In that earlier article, the not-yet-christened Moseyer (as the column writer would come to be known) observed a house in Groton, Massachusetts, that was “a dwelling with rooms blithely located at five different levels” and concluded, after chronicling its many more quirks, “If you’re an imaginative family, this house could be fun.” Returning in 2010, Yankee found the latest owners (it had sold several times since 1950) ensconced in a home they’d spent seven years straightening out, among other improvements. Would they have taken on the house if they’d known the time and money involved?

“Never,” the owner said. “I would have been scared off.”

While the Moseyer stayed incognito, the column bore the firm imprint of longtime Yankee editor Judson Hale. The Moseyer’s pen would go on to change hands a few times, but the basic tone of piqued curiosity—leavened with a touch of Yankee skepticism—remained. Every so often, you can tell he or she is just as tempted to chuck it all as their readers are.

In a rare bylined “House for Sale” in 2017, Mel Allen, then Yankee ’s editor, stepped in to write what would result in the magazine’s closest brush with virality. E.B. White’s house in North Brooklin, Maine, was being put on

North of Portland and south of Bar Harbor, Maine’s MidCoast region is a vibrant and stunningly beautiful natural destination dotted with charming villages for dining, shopping, and exploring. Experience our worldclass museums, enjoy our theaters, stroll our beaches, visit our vineyards, and hike our rocky coast. Find travel ideas for families, foodies, adventurers, history buffs, and even relaxation seekers at MainesMidCoast.com.

the market, and Allen was given a tour for the September/October issue. The resulting column drew attention from The New York Times, Town & Country, and other media outlets, and went on to be the most-read “House for Sale” in the magazine’s history.

The Charlotte’s Web author had purchased the 44-acre saltwater farm in 1933, doing his own version of chucking it by leaving New York City and moving to Maine permanently four years later. The latest owners were a couple who’d purchased the property on a handshake from White’s renowned boatbuilder son Joel in the early 1980s. They, too, were escapees, seeking a quiet life of gardening and sailing, away from their business life in South Carolina. The tour included the barn where Charlotte may have spun her web, complete with Fern’s rope swing, and “the trim boathouse where, when the weather was right or there was too much going on in the house, E.B. White would retreat with

his black Underwood typewriter,” Allen wrote. “There he built a simple table and bench, placed a barrel for waste and an ashtray by his side, and with the sea breezes for company typed some of the most elegant and memorable sentences in the English language.”

The listing agent was Martha Dischinger of Downeast Properties. “I must have gotten 35 to 40 inquiries a day back then,” she says. “The farm sold for full asking price a week after it came to market, but the phone just kept ringing. I probably got five or 10 calls a year for five or six years afterward.” The phone still rings occasionally, and schoolchildren sometimes write, asking about Charlotte and the barn. The new owners are a family from the Philadelphia area who spend time year-round at the farm. “They’re

great people, well integrated into the community, and the husband sometimes writes down in the boathouse,” Dischinger reports.

Over the decades, “House for Sale” has highlighted stores, inns, and once even a whole town (the brick mill village of Harrisville, New Hampshire, was ultimately acquired by a nonprofit that now hosts living and work spaces in its store, church, and mill buildings). Each sale is someone’s dream come true—and I’ll bet Robb Sagendorph smiles down each time a new owner packs up and, ahem, steals away.

Head over to Yankee’s website, NewEngland.com, to read a selection of classic “House for Sale” columns—and if there are properties you remember fondly from years past, let us know in the comments: newengland.com/HFS

Located along the Southern Maine coastline, our active, engaged community combines worry-free independent living with priority access to higher levels of on-site care—all for a predictable monthly fee.

Residents enjoy apartment, cottage, and estate home living in a community of friends, with all the benefits of Maine’s first and only nonprofit life plan retirement community.

(207) 883-8700 • Toll Free (888) 333-8711 15 Piper Road, Scarborough, ME 04074 • www.pipershores.org

Swans Island was founded on the allure of heirloom-quality wool blankets, which remain the company’s signature offering more than 30 years onward.

BY VIRGINIA M. WRIGHT

The people who make Swans Island Company blankets work a quarter-mile upshore from Penobscot Bay in a 235-year-old farmhouse fringed by a border of Solomon’s seal and lady’s mantle. Their daily commute encompasses working harbors, placid lakes, forested mountains, and wild blueberry barrens. “We live in a place where you can open your window, and a cloud will drift in off the ocean,”

says company president Bill Laurita. “Nature is close at hand; it’s part of our lives. This is not a fancy, complicated, plasticized place, and our designs aren’t like that either.”

Swans Island’s handwoven woolen blankets embody the spirit of coastal Maine—its traditions, its timelessness, even the mutable nature of its tides and weather—in subtle ways. The palettes are soothing, the designs classic and

understated: a few stripes of varying widths, perhaps; some softly contrasting checks; or maybe one glorious colorway that on close inspection proves to be not a solid at all, but rather a marbled interplay of uncountable shades. Some references are more direct. The white-flecked Firefly fabrics are inspired by the spectacle of lightning bugs flickering in a field on a hot summer night. A hue called Seasmoke

clockwise from top left:

Dyeing yarn by hand and in small batches ensures optimal color and texture; a weaver at work in the Swans Island studios in Northport; at one of the small family farms from which Swans Island sources its wool, sheep are outfitted in little jackets to help keep their fleece clean and free of chaff.

draws its soft pearly gray from the fog that spirals and drifts over the bay on bitterly cold winter days. Autumn in New England, a limited-edition throw created in collaboration with Yankee for the magazine’s 90th anniversary this fall, deconstructs an October landscape from earth to sky in bands of crimson, orange, sage, gold, and pale gray.

“We aim to capture the complexity of nature and lay down the colors as simply as possible on the loom,” Laurita says. “But—and this may seem like a contradiction—simple is hard to do. You have to start with really good ingredients.”

Laurita’s office is on the Northport farmhouse’s second floor, in one of the low-ceilinged rooms he and his wife, Jody, called home for a few years after he and his partners bought the company and moved it from its eponymous island in 2004. The founders, John and Carolyn Grace, were lawyers from Boston, motivated by a dream of living year-round on the actual Swan’s Island, where they had a summer home. Taking stock of an island neighbor’s prizewinning sheep, the Graces settled on creating a living around that fleece by reviving the kind of heirloom-quality

wool blankets they remembered from their childhoods. They researched traditional New England styles in the Maine State Museum’s textile archives, installed two floor looms in their home, and sold their first blankets in 1992. Within a few years, they had a national clientele and a coveted spot in the annual Smithsonian Craft Show in Washington, D.C.

An MBA holder who has worked as a Waldorf teacher, carpenter, and blacksmith, Laurita was drawn to the challenge of scaling up the Graces’ cottage business while maintaining the quality and individuality that distinguished their blankets from massproduced textiles. Today, Swans Island Company employs about 25 people, about half of whom are hands-on crafters: the weavers, dyers, and finishers who annually make about 1,000 woolen blankets, the signature product in a line of goods that includes linen bedding, yarn, apparel, and bags. Swans Island buys its Corriedale fleece from family farms in Pennsylvania and Ohio and sends it to Green Mountain Spinnery in Vermont, where it’s spun into soft, single-ply yarn.

Shipping is always Safe, Fast and FREE

There are five states we can’t ship to. Check online to see if you qualify.

Whales Dive on Moonlit Nights

By day, the mysteries slip by just beneath the surface. At night, beneath the moon, beneath the waves breaking the surface, creatures of the deep rise, catch air and glide beneath the stars. Perhaps that is why we hesitate to go swimming in the dark. We have no idea who or what may be out there waiting.

I live at the shore in a 100-year-old cottage 50 feet above the sea. After the sun goes down every night, I go out to the railing to watch the moonlight on the water, to see the boats with their lights as they sail into the night. I listen for the sounds of the waves on the shore. I wait for something… I’m not sure what, but I wait every night.

The Mysteries of the Sea necklace is the size of an American half dollar, 30 mm or slightly more than an inch in diameter. It’s a glistening mother-of-pearl crescent moon. A blue Topaz star in the night sky hangs above. A white whale tail carved from a 15,000-yearold ancient mammoth ivory tusk dives into the sea. The ocean has four silver ripples on the surface. It’s all out there.

Sterling Silver necklace with a 5mm round Blue Topaz and a mother-of-pearl crescent moon and an ancient fossilized mammoth tusk hand-carved whale tail.

Whales Dive Necklace.....X4543.....$235

A. Order online 24 hours a day

B. Order by

9:30-5 EST

Snowy Egret Blue Topaz Necklace Style #: X4566.....$295

Sea Otter Necklace Style #: CA159.....$465

Mermaid Looking to Heaven

Blue Topaz Necklace Style #X4529 $275

Puffin’s Private Island Kingdom Necklace Style #X4493 $225

The Mermaid Mystery Ancient Fossil Ammonite Style #X4646 $385

Puffin Into the Sea, Into the Gale Necklace Style #X4492 $245

Blue Ring Octopus Blue Topaz Necklace Style #X4567 $285

(SHOWROOM NOTOPEN) WEARE NOW EXCLUSIVELY ONLINE!

Swans Island Company and Yankee are partnering to give away one of these handwoven, hand-dyed wool blankets, designed to capture the essence of New England in the fall. For contest rules and to enter, go to: newengland.com/swansisland Giveaway runs 9/1/25–9/31/25.

Presiding over the dye studio is Riley Smith, who concocts dye baths according to the company’s 180 custom-color recipes, using mostly natural pigments, such as blues from the indigo plant and reds from cochineal beetle shells. Smith swishes skeins around in pots and tubs, then allows them a carefully monitored soak before scooping them onto drying hooks. He’s adept at resist techniques, like tying and twisting the skeins to block sections of yarn from receiving dye (that’s how Firefly gets its

Continuing its tradition of designing a limited-edition collection or piece each year, Swans Island is celebrating Yankee’s 90th anniversary this fall with a vibrant handwoven wool throw called— what else?—Autumn in New England.

“light trails” and Watercolors, another blanket style, gets its washy teal and blue currents). Unlike industrial dyeing, which compresses fibers and produces monochromatic colors, small-batch dyeing maintains the yarns’ loftiness and yields multitonal shades akin to the gradients within flower blossoms.

In the farmhouse’s ell, weavers sit at piano-sized looms, pushing and pulling beater bars to lift and lower warp threads as weft shuttles zip back and forth, propelled by compressed air. A skilled weaver can create a queen-size blanket in about eight hours; setting up the warp, however, remains a two-day process requiring 3,456 hand-tied knots. When completed, the blanket is sent upstairs to the finishing room, where artisans use surgical tweezers to remove any remaining bits of chaff, inspect for and resolve flaws, and embroider custom touches like monograms.

Designs are a team effort. Spring Into Summer, a limited-edition throw, took root during a January thaw that found the staff anticipating the lightness and promise of an awakening landscape still some months away. Smith accepted the challenge of expressing that mood in natural white wool crisscrossed with a fresh green, blue, yellow, and pink windowpane plaid.

That in turn prompted conversations about creating a fall blanket. Creative director Michele Orne studied landscape photographs, experimented with groupings of colored skeins, and shared sketches with her collaborators at Swans Island and Yankee. In keeping with Swans Island’s aesthetic, Laurita says, Autumn in New England is not a literal interpretation, but rather an expression of the mellow season’s fleeting yet ever-renewing splendor, one that will provide warmth and nostalgia for generations. swansislandcompany.com

As Yankee turns 90, we unearth recipes from the archives that have stood the taste-test of time.

BY AMY TRAVERSO

f you look at food beyond what’s on your plate, it can be a window through which you learn about history, art, culture, economics, family, and geography. Consider our Yankee recipe archives: Each dish represents a moment in time and offers a glimpse of daily life as it was shaped by forces large and small. In the postwar 1940s, for instance, our editors praised the “wayside inns” serving classic New England fare like chicken potpie. Convenience foods came to the fore in the 1950s, with Ritz crackers being used as the topping for an iconic baked scallops dish. In the 1980s, Yankee ’s recipes became markedly more global, and we see Portuguese dishes like kale and chouriço soup woven into the fabric of regional cooking.

In celebration of the magazine’s 90th anniversary, I’ve compiled a list of favorite recipes from our archives. So join me in a little time travel through the decades, and get cooking! (In the interest of reliability, some recipes did need to be adjusted to appeal to modern tastes, but all remain true to the spirit of the original dish.)

MAINE POTATO DOUGHNUTS WITH CRANBERRY GLAZE

Potatoes are still the primary crop in northern Maine, and in the 1930s, the state was producing about 15 percent of the country’s spuds. Mainers incorporated potatoes into everything, and in the May 1937 issue alone, Yankee featured 100 potato recipes (albeit written in short paragraph form). If you’ve never tried mashed potatoes in doughnuts before, you’ll find that they create a wonderful texture: lighter and more tender.

Note: The drier your potatoes are, the lighter the doughnuts will be, so I bake or microwave them rather than boil them. Also, running the cooked spuds through a potato ricer gives a fluffier texture.

FOR THE DOUGHNUTS

3 tablespoons unsalted butter, softened

¾ cup granulated sugar

1 large egg, at room temperature

1½ teaspoons vanilla extract

1 cup lightly packed mashed russet or Yukon Gold p otatoes (leftover potatoes with salt and pepper are fine)

¼ cup buttermilk, at room temperature

2–2¼ cups all-purpose flour (280–315 grams), plus more for work surface

1 teaspoon baking powder

1 teaspoon baking soda

½ teaspoon table salt

½ teaspoon freshly grated nutmeg

Vegetable oil or vegetable shortening, for frying

FOR THE GLAZE

2 cups powdered sugar

5 –6 tablespoons cranberry juice

In a large bowl, cream the butter and sugar with a standing or handheld mixer until fluffy, about 1 minute. Add the egg and vanilla and beat until glossy and pale yellow.

Add the potatoes and buttermilk and beat until smooth. Add the 2 cups flour, baking powder, baking soda, salt, and nutmeg and beat just until evenly combined. The dough should now be fairly easy to handle, but still a bit sticky. If not, add a bit more flour.

Generously dust your counter with flour. Turn the dough out onto the counter and flip to coat with flour.

With your hands, gently press the dough out to a ½-inch thickness and cut into doughnuts and doughnut holes using a doughnut cutter or two biscuit cutters (a large and a small). Gather the scraps and press out again to use up all the dough.

2000s

Fill a Dutch oven with oil or shortening to a depth of 2½ inches. Set over medium heat and bring the temperature to 375°F (check with a thermometer). Working in small batches, cook the doughnuts and holes in the oil, turning once, until puffed and nut brown, 2 to 4 minutes per side. As you fry, you may need to reduce or increase the heat to maintain a steady temperature.

Transfer the cooked doughnuts to paper towels to drain and cool to room temperature.

Meanwhile, whisk together the powdered sugar and cranberry juice to make the glaze. Start with 5 tablespoons of juice, then add more as needed so that the glaze is thick enough to coat but not too sticky. Dip the tops of the doughnuts and doughnut holes in the glaze, then set aside to dry. Yields a dozen each of doughnuts and doughnut holes.

In Yankee’s February 1948 issue, longtime “Food and Household” columnist Nancy Dixon wrote, “You’ll surely want to make plans to visit the delightful White Turkey Inn at Danbury, Connecticut. This typically New England inn caters to the discriminating tastes of New Englanders with true Yankee food!” The original recipe lists “pie pastry” as one of the ingredients—back then, Dixon could assume everyone knew how to make a crust. Worry not, modern reader: I’ll explain how.

FOR THE CRUST

1¼ cups (175 grams) all-purpose flour

½ teaspoon kosher salt

9 tablespoons cold unsalted butter, cut into small cubes

3 – 5 tablespoons ice water

FOR THE FILLING

4 tablespoons salted butter

1 small yellow onion, diced

1½ teaspoons kosher salt

1 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

3 tablespoons (26 grams) all-purpose flour

2 cups chicken stock

2 ½ cups cooked shredded chicken meat (medium pieces)

¾ cup diced carrots

¾ cup peas

1 tablespoon chopped fresh parsley leaves

1 teaspoon fresh thyme leaves

1 large egg

1 tablespoon water

Fresh parsley leaves and thyme sprigs, for garnish

(Continued on p. 93)

1990s

Fall mornings are sweeter when they begin with these apple recipes inspired by our TV show, Weekends with Yankee.

STYLED AND PHOTOGRAPHED

BY LIZ NEILY

Morning fog was still blanketing the Contoocook River Valley when we arrived at Gould Hill Farm to begin a day of filming Weekends with Yankee ’s ninth season. With an elevation of about 1,100 feet, this hillside New Hampshire farm commands views all the way to Maine, and on an early October day, with the foliage tipping from green to orange, yellow, and red, it seemed as though we had found our way to paradise.

In nine seasons of filming Weekends with Yankee, we’ve visited three other apple farms in addition to Gould Hill (Poverty Lane Orchards in Lebanon, New Hampshire; Cider Hill Farm in Amesbury, Massachusetts; and Scott Farm Orchard in Dummerston, Vermont). We’ve talked with farmers and farm stand managers about the finer points of making cider, growing heirloom apples, frying cider doughnuts, and choosing the best apple for a recipe. Having written a book about apples myself (The Apple Lover’s Cookbook , available in the NewEngland.com Store), I found this to be familiar and fond territory.

But there’s always more apple goodness to discover. My morning at Gould Hill even got me thinking about some new apple recipes—specifically, breakfast dishes. The first, a baked oatmeal pudding, is now a staple in my breakfast repertoire. The second, a recipe for doughnut shop–style apple fritters, is a project bake, but boy, is it worth the effort. Give them both a try. And welcome to apple season! >>

This baked oatmeal pudding studded with apples and cranberries is healthy and hearty. I love to bake a batch on Sunday and eat my way through it during the week, always with a dollop of yogurt and a drizzle of maple syrup.

Butter, for greasing baking dish

3 cups milk

4 large eggs

½ cup packed light brown sugar

¾ teaspoon ground cinnamon

¼ teaspoon ground nutmeg

2 cups rolled (old-fashioned) oats

¾ cup halved fresh cranberries

¾ cup diced firm-sweet apples

¹⁄3 cup chopped walnuts

1½ teaspoons baking powder

¾ teaspoon kosher salt

Yogurt and maple syrup, for finishing

Preheat your oven to 325°F. Butter a 2-quart baking dish and set aside.

In a large mixing bowl, whisk together the milk, eggs, brown sugar, cinnamon, and nutmeg. Add the oats, cranberries, apples, walnuts, baking powder, and kosher salt and stir until evenly combined.

Pour into the baking dish, place into the oven, and bake until the center is set and the top is golden brown, between 50 and 60 minutes. Serve warm with yogurt and maple syrup. Yields about 8 servings.

Glazed and studded with bits of tart apple, these fritters have the perfect pullapart texture.

4

– 4¼ cups (480 – 510 grams) all-purpose flour

1 package (2¼ teaspoons) rapid-rise yeast

1½ teaspoons kosher salt

1 cup apple cider

6 tablespoons melted salted butter

2 large eggs plus 1 large egg yolk, at room temperature

Vegetable oil, for coating dough and frying

FOR THE FILLING

2 tablespoons salted butter

1½ large tart apples, cut into ¼-inch dice

¼ cup granulated sugar

½ teaspoon freshly grated nutmeg

¼ cup plus 3 tablespoons all-purpose flour (35 grams plus 26 grams), plus more for dusting counter and dough

2 tablespoons ground cinnamon

FOR THE GLAZE

3¼ cups powdered sugar

½ cup hot water

Large pinch kosher salt

In a large bowl, whisk together the 4 cups flour, yeast, and salt. In a medium bowl, whisk together the cider, melted butter, and eggs. Add the liquid ingredients to the dry and stir with a spatula until the dough comes together in a ball. Use your hand to knead the dough in the bowl, adding the remaining flour, 1 tablespoon at a time, as needed to prevent sticking. Knead for a total of 3 minutes. Pour a bit of oil over the dough ball, then turn to coat. Cover and let rise at room temperature until doubled in volume, 2 to 2½ hours. (You can also refrigerate the dough for up to 36 hours.)

Meanwhile, make the filling: Melt the butter in a skillet and add the diced apples. Cook, stirring often, until the apples begin to soften, about 3 minutes. Add the sugar and nutmeg and cook, stirring, for 2 more minutes. Spread apples on a large plate and let cool to room temperature.

When the dough has finished rising, dust your counter with flour, then turn the dough out. (If it has been refrigerated overnight, it should be covered with a towel and allowed to come to room temperature for 1 hour before the next step.)

Dust the dough with flour, then roll it out to an oval that’s roughly 18 inches

long and 8 inches wide. Position the oval with a short end facing you. Spread the apple mixture over the dough, leaving a one-inch top border at the top. Sprinkle with ¼ cup flour and cinnamon. Roll the dough up from the bottom like a jelly roll, sealing at the top. If any apple pieces come out the sides, tuck them back into place.

Starting from the left side, use a knife to cut the roll diagonally into strips. Then, from the right side, cut on the opposite diagonal, forming diamondshaped pieces roughly 1 inch long. (This will look and feel messy, but it’s essential to achieve a classic pull-apart texture.)

Dust with the remaining 3 tablespoons flour, then gather into a loaf about 12 inches long and press it very firmly back together. (If you don’t squeeze tightly, the fritters can fall apart in the oil.)

Line a rimmed baking sheet with parchment paper or a silicone mat. Using a knife or bench scraper, cut the loaf crosswise into 12 rounds. Press the rounds with your fingers to elongate them a bit, then set them on the baking sheet, cover with parchment paper, and let rise for 30 minutes.

Fifteen minutes into the final rise, fill a Dutch oven halfway with oil and set over medium heat, bringing the temperature to 365°F. Line a rimmed baking sheet with paper towels and set aside.

Use a spatula to transfer two or three fritters into the hot oil and cook until nicely browned on one side, about 2 minutes, then flip and cook until the other side is browned and the fritter is cooked through, 1½ to 2 minutes more. Transfer to the baking sheet and blot to remove excess oil. Repeat with remaining dough, checking the oil temperature regularly and adjusting the heat to keep it as close to 365°F as possible.

Transfer fritters to two wire racks set over rimmed baking sheets. When cooled, prepare the glaze by whisking together the powdered sugar, hot water, and salt in a medium bowl.

Dip each fritter in the glaze to coat both sides, then return to the wire racks. Let sit until the glaze has set, about 10 minutes. Serve. Yields 12 fritters.

Come visit us today!

Come visit us today!

Come visit us today!

“Your house for all occasions”

“Your house for all occasions”

“Your house for all occasions”

Candies! For over 50 years we have used only the finest ingredients in our candies—cream, butter, honey, and special blends of chocolates. Call for a FREE brochure.

Candies! For over 50 years we have used only the finest ingredients in our candies—cream, butter, honey, and special blends of chocolates. Call for a FREE brochure.

Long famous for quality candies mailed all over the world.

Long famous for quality candies mailed all over the world. Treat yourself or someone special today.

Treat yourself or someone special today.

Candies! For over 50 years we have used only the finest ingredients in our candies—cream, butter, honey, and special blends of chocolates. Call for a FREE brochure. Long famous for quality candies mailed all over the world. Treat yourself or someone special today.

292 Chelmsford Street • Chelmsford, MA 01824 For Free Brochure Call: 978-256-4061 < >

292 Chelmsford Street • Chelmsford, MA 01824

292 Chelmsford Street • Chelmsford, MA 01824 For Free Brochure Call: 978-256-4061 < >

Call 978-256-4061 for Free Brochure

Visit our website: mrsnelsonscandyhouse.com

292 Chelmsford Street • Chelmsford, MA 01824 For Free Brochure Call: 978-256-4061 < >

e View from Mary’s Farm Grace and beauty in every season. Clark’s lyrical essays capture New England through weather, landscape, and independent people. By Edie Clark

Here in New England

45 unforgettable stories from Yankee’s beloved editor. Fascinating people and places from nearly 50 years of writing. By Mel Allen

Summer Over Autumn Hidden stories everywhere you look. Essays about neighbors, yard sales, and other facets of small-town life. By Howard Mans eld

GravestoneRubbingSupplies.com 800-564-4310 GravestoneArtwear.com

In early days bells were used as a way of communication. Sleigh bells were fastened to horses to signal your arrival. With the roads being narrow, pedestrians could hear a sleigh approaching and move out of harm's way. If you broke down and another sleigh stopped to help, it was customary to give the good Samaritan your sleigh bells, for their assistance. Hence the saying “I’ll be there with bells on” means you expect a happy and trouble-free arrival.

To order: email um.press@maine.edu or call (207) 581-1652 See all our books at umaine.edu/umpress/

In this bikeable college town, fall foliage only adds to the abundant local color.

BY BRIAN KEVIN | PHOTOS BY MICHAEL D. WILSON

this page: The salmon-pink gables of Bowdoin College’s 1894 Searles Science Building peek through the fiery fall colors in downtown Brunswick. opposite, clockwise from top left: Bowdoin’s Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum; the pineapple daiquiri at The Abbey, a hybrid coffee shop/ cocktail bar; a passion fruit éclair and a yuzu curd tart at ZaoZe Café & Market; Frosty’s Donuts, a Maine Street landmark for more than 50 years.

Squint at Brunswick, Maine, from a few different angles and you may see a historic mill town, a former military base, or a slightly bougie Portland bedroom community. Nestled between Casco and Merrymeeting bays, at the confluence of the Androscoggin and Kennebec rivers, the town of 22,000 is all of those things. But whatever else you can say about it, Brunswick is a college town—in the lowest-bar sense of having Bowdoin College smack in the middle of it, sure, but also because it boasts the quintessential college-town trappings: a walkable core, café culture, an arts scene, and nightlife.

And never does Brunswick feel collegetownier than in September and October, when the students are settling back in, filling bars and shops along Maine Street (yep, correct spelling) and idling beneath the increasingly vibrant maples and oaks that shade the Town Mall.

On a recent visit, I opted to tool around Brunswick in classic student fashion, posting up at the white-columned Brunswick Hotel, right across from campus, and going only where the front desk’s complimentary cruiser bikes could take me. The stately 51-room hotel, as it happens, is 500 feet from the Amtrak station, where trains pull up from Boston daily, so a car-free Brunswick weekend isn’t just for middle-aged alums reliving their salad days. (Gorham Bike & Ski, two blocks from the station, rents road bikes and e-bikes.)

It was cocktail hour when I got into town, so I wheeled over to the low-key fireplace pub at OneSixtyFive, an 1848 Federal-style inn on a shady lane of 19th-century mansions, called Park Row. This is best-kept-secret stuff: Plenty of Brunswickers don’t know that the inn’s Pub165 is open to all, that its cocktail menu is on point, and that you can enjoy your drink of choice (and perhaps some rosemary-truffle cashews) on the huge wraparound porch. Live

cent Town Mall gazebo. Get another drink and some lobster corn cakes, and voilà, cocktail hour becomes dinner.

The next morning started with strong coffee and a house-baked sticky bun at Dog Bar Jim, just off campus. Narrow and festooned with weird bric-a-brac, including some Seinfeld-themed pieces, it’s the ’90s-throwback coffee shop of your bohemian dreams. Mugs are thrift-store mismatched,

from top: Among the highlights of Maine Street is the revitalized 1870 landmark (left) known as the Lemont Block; made-from-scratch offerings at Wild Oats Bakery & Café include crispy-melty panini and pastries such as classic sprinkle-topped cupcakes.

and espresso drinks are expertly made (just don’t ask for a pumpkin spice latte).

Where did Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Nathaniel Hawthorne get their joe? The two members of Bowdoin’s Class of 1825 are on a long roster of notable alumni. You’ll find their portraits in the vast collection of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, one of the country’s oldest collegiate museums, dating to 1811. Among other things, it’s big on antiquities—the current “Flora et Fauna” exhibit considers how nature is depicted on an awe-inspiring assemblage of ancient Mediterranean figurines, urns, chalices, and more (on view through March 7, 2026).

But only two Bowdoin alums have a whole campus museum named for them. The PearyMacMillan Arctic Museum was once a glorified gallery, filled with artifacts acquired during the polar expeditions of admirals Donald MacMillan and Robert Peary. In 2023, it reopened in a dramatic three-story space, the public-facing half of the new Gibbons Center for Arctic Studies, with an expanded

The Abbey: “Some people expect we’re strictly coffee in the day, then switch to strictly bar, but it’s everything all day long,” co-owner Connor Scott says. “The joke is, if you want it, we’ve got it.” theabbeymaine.com

Dog Bar Jim: Expect a little line when chatty owner Ben Gatchell is working the lovely copper espresso machine. Admire the wall art: a framed Calvin and Hobbes strip, a 1971 Hawkwind album cover, and other curiosities. dogbarjim.com

Flight Deck Brewing: Here’s a strong contender for New England’s best beer garden, with heated gazebos and A-frames, firepits, lawn games, and tasty pizzas flying out of a wood-fired oven. flightdeckbrewing.com

Wild Oats Bakery & Café: An anchor tenant of Brunswick Landing, the redeveloped former military base, Wild Oats is known for piled-high sandwiches and a deep menu of soups (if it’s on offer, try the pumpkin-mushroom). wildoatsbakery.com

ZaoZe Café & Market: PanAsian fare that’s casual in vibe, masterful in execution. Craving dim sum? It’s offered only on Sundays but worth planning for. zaoze.cafe

The Brunswick Hotel: Any closer to campus and you’d be in a dorm. Noble, the in-house restaurant, has its own firepit courtyard, a fine spot for drinks and dessert on a crisp autumn evening. thebrunswickhotel.com

The Federal: Clean modern vibes in an expanded 1810 captain’s home. The inn’s 555 North bistro leans in on cheffy, seasonal comfort food. thefederalmaine.com

OneSixtyFive: The historic Main House was renovated after a fire a few years back. Its eight rooms are crisp New England contemporary, with bold-patterned rugs,

emphasis on arctic ecology and both historical and contemporary Inuit art. Built from eco-friendly prefab mass timber, it’s an airy chapel of exposed blonde wood, tall windows, and angled ceilings from which the occasional musk ox gazes down. Highlight of my morning: running my hand over a gnarly old narwhal tusk.

After a few hours of museums, I steered my cruiser off campus and toward a couple of pillowy steamed pork buns at ZaoZe Café & Market, a mod little cafeteria inspired by convenience stores in China and Southeast Asia. Next, a spin through a couple of Maine Street’s old reliables. Gulf of Maine Books has been a paragon of an indie bookshop since 1979, its well-stocked shelves bordering on cluttered. A short stroll away, Nest has anchored the 1896 Lincoln Building for more than 20 years, a colorful 6,000-square-foot bazaar of home and garden goods. The afternoon’s haul included a copy of Maine novelist Ruth Moore’s Spoonhandle, recommended by Gulf of Maine co-owner Gary Lawless, and a pair of speckled ceramic soap dishes.

Then, wouldn’t you know, it was cocktail hour again, and I headed across the street to The Abbey. Opened by Connor Scott and Lainey Catalino in 2023, it’s the too-rare combo of craft coffee shop and cocktail bar, welcoming the laptop set during the day and a lively dinner-and-drinks crowd at night (with plenty of overlap). The vibe is DIY glam—mirror ball, candelabras, zine-like handwritten specials menus—and befitting a college town, the place stays open most days till the scandalous hour of 11 p.m. I ordered a Korean-inflected margarita, with house-made gochujang-grapefruit syrup, and an oh-so-fall roasted delicata squash salad, then sat back on my upholstered retro barstool for some people-watching. Longfellow and Hawthorne never had it so good.

wallpaper, and upholstery offsetting gorgeous antique furnishings. There’s seven more rooms in an adjacent annex and a dog-friendly cottage, too. onesixtyfivemaine.com

PLAY

Bowdoin College Museum of Art: With its columns and Renaissance-style rotunda, the museum’s 1894 building is itself a work of art. Get a selfie with the stone lions out front. bowdoin.edu/ art-museum

Cabot Mill Antiques: In the massive spinning room of a former cotton mill, some 160 stalls worth of treasures: Victorian salvage, deep-cut vinyl, nautical knickknacks— you name it. cabotiques.com

Gulf of Maine Books: Storied indie bookseller with a crunchy shell. Its nature writing and poetry shelves are uncommonly robust.

Harpswell Detour: South of town, back roads traverse the islands and peninsulas that make up quiet little Harpswell—worth a scenic drive, especially when the leaves are poppin’. Get a lobster roll with a view at Erica’s Seafood (open until mid-October). Watch the tide filter through the famed Cribstone Bridge at the end of Orr’s Island. Clamber over rugged oceanside ledges at Giant’s Stairs on Bailey Island. hhltmaine.org

Nest: Two jam-packed floors of eclectic home goods and gifts ... let the browsing begin. Facebook

Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum: Among the highlights here are photos, letters, and artifacts relating to Matthew Henson, Peary’s pole-seeking comrade and one of America’s foremost Black explorers. bowdoin.edu/ arctic-museum

Woodward Point Preserve: This Maine Coast Heritage Trust property has the area’s best birding. Watch for great blue herons, bobolinks, ospreys, and more. mcht.org/ preserve/woodward-point

Yankee’s longtime foliage expert makes the case for six less-expected leaf-peeping spots.

Jim Salge has been anticipating this year’s autumn since, well, last year’s autumn, when a severe drought diminished New England’s normally brilliant foliage. But 2025 will be different, says Yankee ’s veteran foliage reporter. “We’re in a much different place,” he says. “It’s going to feel extra special.” In Salge’s eyes, however, some parts of New England shine just a little bit brighter than others. If you’re on the road this season, you might just find him at one of these scenic autumn destinations. —Ian Aldrich

In addition to a Main Street that’s chockablock with locally owned shops and restaurants, this White Mountains town offers ready access to all things

foliage. “There’s great sightseeing and hiking right in town,” Salge says. “Kilburn Crags is an easy hike that has fantastic views.” Even better: As a regional hub, Littleton can be the starting point for color-filled drives into northern New Hampshire and Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom.

Northern New England isn’t normally associated with late-autumn color, but that’s exactly what you’ll find in Vermont’s Champlain Valley. “This region is pretty much a can’t-miss proposition, because the color is there anytime from late September into late October,” says Salge. “And if you’re looking to go hiking, you can’t do much better than Mount Philo.”

With views of nearby Franconia Notch and Mount Lafayette, the town of Littleton, New Hampshire, is a handy home base for exploring the White Mountains’ spectacular fall foliage.

“Maine’s coast always gets attention,” says Salge, “but there’s so much beauty in the mountains”—in particular, Maine’s White Mountains region.

“You go to a place like Grafton Notch State Park, and you’ve got these amazing waterfalls and hikes. Sunday River ski resort is right there. And if you want to make a long weekend of it, you’re not far from Rangeley.”

New England’s biggest city is packed with green space, which in fall comes alive with seasonal color. “People don’t normally think of the Boston area as a foliage destination, but it really is,” Salge says. “You have the Esplanade, Mount Auburn Cemetery, Blue Hills. And at the end of the day, you’re in Boston—you can’t lose.”

Less than half an hour’s drive north from Hartford is a slice of rural Connecticut that cranks the fall appeal to 11. We’re talking acres of farmland, pumpkin patches, apple orchards, and, of course, foliage.

“There’s also just so much good public land around the nearby Barkhamsted Reservoir,” Salge says. “It’s a place that puts you in the center of it all.”

Sure, Rhode Island’s coastal zones offer lovely late-autumn color, but Salge prefers to head inland. “There are miles and miles of pretty scenic roads and lots of biking,” he says. “It’s a beautiful place to visit to extend your fall.”

For Jim Salge’s weekly foliage reports, go to newengland.com/foliage.

Starting just shy of Canada and unspooling down the length of Vermont, Route 100 drops leaf peepers into the heart of fall foliage.

BY BILL SCHELLER ||| PHOTOS BY OLIVER PARINI

wanted to drive south through Vermont, the same direction the autumn colors were taking as they trickled down from Canada. Yes, they travel slower than I do; they take longer to get to the Massachusetts border. Still, it seemed the right way to take in the great chromatic event. And there’d be bright surprises here and there. Southbound color sends an advance guard, especially at higher elevations.

Along the way, I’d also travel in another direction, back in time, past places that were part of my own Vermont, in all seasons.

I’d make the trip, border to border, along a single road, and there are three such options in Vermont. There’s Route 7, in the west. There’s the twin set of U.S. 5 and I-91, along the Connecticut River Valley. And then there’s Vermont 100. It’s the longest state highway, and the twistiest; the old telegraph cables that ran alongside it used to “travel each bend,” per the lyrics to the state’s unofficial state song, “Moonlight in Vermont.” It goes through the fewest big towns, and through no cities at all. If Route 66 is America’s “mother road,” as John Steinbeck claimed, Route 100 is Vermont’s.

For some reason, 100 doesn’t quite nick the Canadian border; instead, it begins inconspicuously near Newport Center. Close enough. As I set off, Jay Peak rose to the west, its tram house giving the summit its distinctive bent-beak look. The southern shores of Lake Memphremagog were just east. Canada was right over my shoulder.

Route 100 starts off low and lonely, by way of farm country; the first Technicolor forests are a few miles south. The road doesn’t reach settlements of any size till Troy and Westfield, where there’s little more than a Benedictine abbey where the nuns still wear wimples. It would have been nice to start my drive with Gregorian chant, but it was the wrong time of day.

Lowell, which reveals itself on 100 as a gas station and a bowling alley that looks more like a faceless country roadhouse, was where I took a short side trip into the bright autumn woods. A fragment of the Bayley-Hazen Road—a Revolutionary-era military route into Canada that was abandoned when someone realized it went both ways—wanders

from top left: Picking the fruits of autumn at Waterbury’s Hunger Mountain Orchard; Vermont Artisan Coffee & Tea, just a short drive from the orchard, adds its own splash of red to the fall landscape; the postcard-perfect Old Parish Church steeple in Weston.

off as Route 58 from the town green; I drove it for a few miles and headed back to 100, having had my first good taste of color. There was plenty more to come just south in Eden Notch, a pass in this starkly rumpled stretch of the Green Mountains. It brought me to the western shores of fork-shaped Lake Eden, where I met a man with what must be one of Vermont’s loneliest jobs.

He sat on a folding chair next to the boat launch, shaded by a big beach umbrella and drinking coffee from a thermos. I knew he was some sort of state worker, as he’d opened a locked kiosk to get the chair and umbrella. I asked him what he was there for. “To make sure people with boats don’t bring milfoil into the lake,” he replied. It was the tail end of the boating season—no watercraft were in sight—and I hoped he’d brought something to read.

Morrisville, which used to be a railroad stop between Portland, Maine, and Lake Champlain, is now the principal junction along the Lamoille Valley Rail Trail, the longest such trail in New England. This may be the best place to blend a leaf-peeping drive with a leaf-peeping walk or bike ride, and there’s even a trailside brew pub.

If roads could have inferiority complexes, Route 100 between Morrisville and Stowe would be a candidate. It’s a decent enough stretch, but utilitarian: People who want dramatic scenery scoot west on Route 15 to Jeffersonville, where they can approach Stowe by way of Route 108 through Smugglers’ Notch and its hairpin turns.