The Issue Bird

Staff

Editors-in-Chief

Gavin Guerrette

Audrey Kolker

Managing Editors

Ana Padilla Castellanos

Harper Love

Kinnia Cheuk

Olivia Wedemeyer

Associate Editors

Brunella Tipismana

Emily Khym

Everett Yum

Fatou M’Baye

Isabel Maney

Jonas Loesel

Owen Curtin

Andrew Lau

Sophia Ramirez

Sukriti Ojha

Layout

Adam Bear

Head Illustrator

Thisbe Wu

Illustrators

Anna Chamberlin

Neve O’Brien

Davianna Inirio

Columnists

Eli Osei

Keya Bajaj

Chela Simón-Trench

This is the bird issue. We at the Magazine have long been enticed by all things avian, so when it came time for us to decide a theme for this issue, our bird brains hatched this egg.

Think flight. Think freedom. Think song. Think ducks! Think death, bread, and trash. Think old and new systems of scientific classification. We’re so excited for you to fly through the pages of this issue.

We are, as always, endlessly grateful — to our tireless managing editors, our brilliant associate editors, our extraordinary illustrators, our wonderful layout team, and our aeronautical, soaring writers. Enjoy this issue of the Magazine, and when you’re done, be sure to look up.

Gavin and Audrey April 2024

Illustrations by Thisbe Wu

Illustrations by Thisbe Wu

Pin-Up #3: Three True Things from Buenos Aires column | Chela Simón-Trench

Short Story Long #3 column | Eli Osei

Lyle & Ophelia & Betty & Dupree feature | Audrey Kolker

Birdwatcher Watching feature | Suraj Singareddy

The Moth Collector feature | Nicole Viloria

Morning Walk essay | Gavin Guerrette

Naming Birds feature | Lazo Gitchos

Feeding the Birds essay | Sophia Ramirez

Trash Birds

| Molly Hill

Prum’s Great Search

CONTENTS

feature

Richard

profile

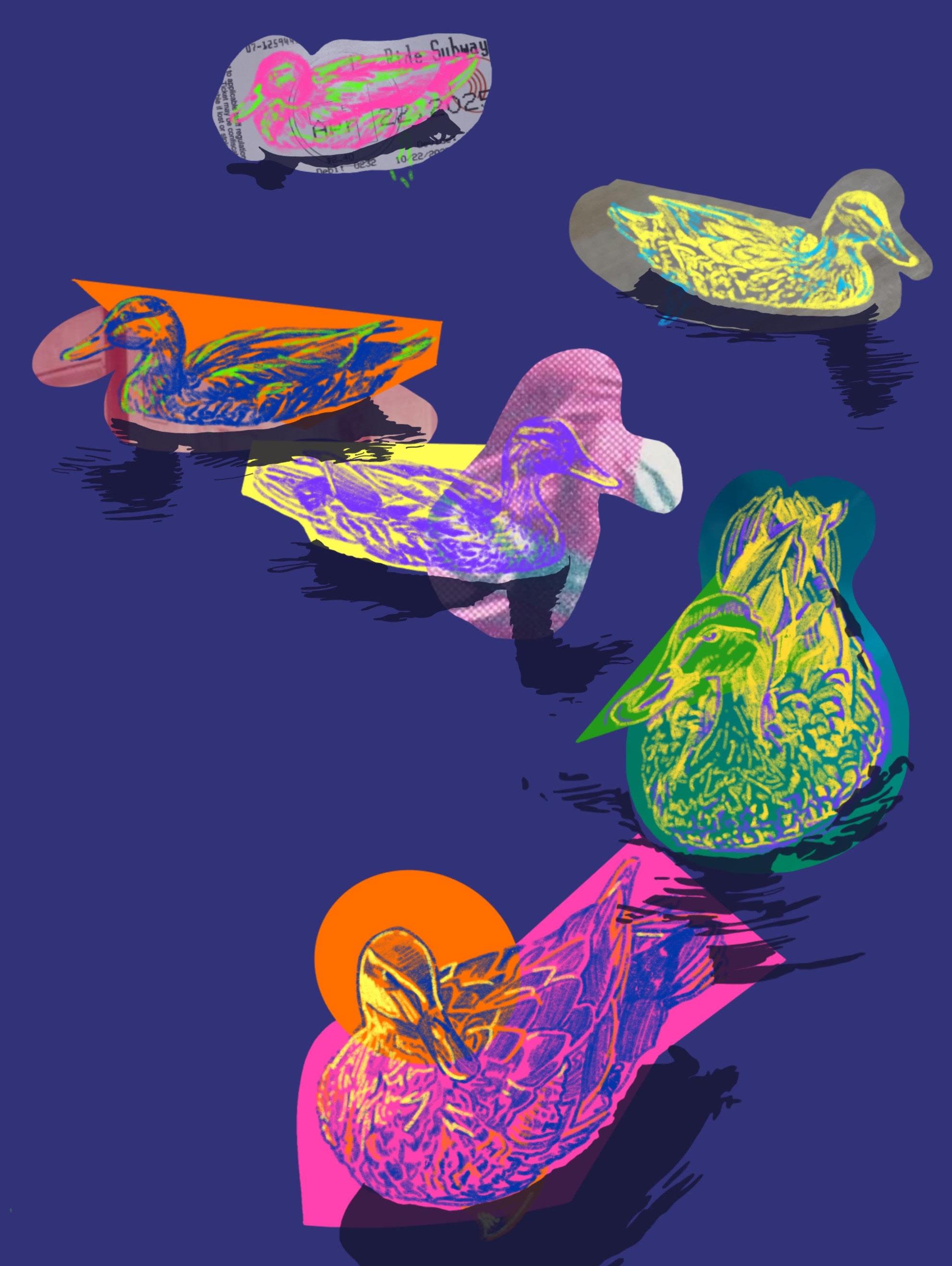

cover

back cover | Anna Chamberlin 4 5 6 8 13 14 16 20 21 24

| Harper Love

| Davianna Inirio

PIN-UP #3: Three True

Things from Buenos Aires

Chela Simón-Trench

This is Pin-Up, a column where, inspired by the informal architectural tradition of presenting designs, I “pin-up” subjects that interest me. Previously, I pinned up The Pietà and obituaries. For this Pin-Up, I decided to do something strange. I am abroad and discombobulated in Buenos Aires, and everything feels like a dream. True things feel surreal. This time, I will Pin-Up three true things from my first month in Buenos Aires, which I have written into a short, surreal, fictional story.

Here are my tHree true tHings:

1. I keep spilling food and drinks on my only white dress.

2. I spent a Sunday in a neighborhood called San Telmo.

3. Buenos Aires has the highest number of bookstores per capita—735 bookshops.

Here is my short story: A rule I live by: when you walk by a bookstore, you should go in because it is sure to be delightful. In San Telmo, I followed a sign, Walrus Books. The bookstore was wooden and dark red; it smelled wet and the books were used. The store clerk spoke to me in crisp English—an English bookstore. Two tourists bumbled in,: a couple in their seventies wearing a lot of khaki, circular glasses, and camelbak packs with straws attached and all. They were looking for any book about Anthony Bourdain. As one of them squeezed past me, their straw caught on a nail sticking out of a nearby bookshelf. I felt my left side get cold and wet—a big, blue stain dripped from the armpit of my white dress to the frill of the skirt. I snapped my exasperated expression towards the tourists but they were already at the counter, berating the clerk about Anthony

Bourdain. It was so strange. Who the hell walks around San Telmo with a camelbak full of blue gatorade?

My feet scuffed softly as I walked the cobblestone street. I turned right or left whenever I felt like it. I found some tall, open windows—another bookstore. There were three big rooms inside, each hotter than the last. The second room was the biggest. Two girls with microbangs clicked on computers at massive, piled desks on either side of the room. Neither of them looked up when I entered. In the last room, I found a bright yellow book on the floor—Conversations with David Foster Wallace in Spanish. It was warm and slick when I picked it up, its waxy cover half-melted in the heat. Without thinking, I wiped my hand on my skirt and froze at the sight of a big, bright yellow handprint on the right thigh of my white dress. I beelined for the door. The microbanged girls never looked up.

I felt strange; it was very hot. I followed a whiff of conditioned air into Libros del Mundo. It was like a spaceship in there: minimalist style, everything gray, coffee tables that looked like massive, perfectly balanced pebbles. I faced the air conditioning unit and leaned back on a curved wall, looking up at a bright skylight. The wall felt cold and prickly; where was the shopkeeper? My eyes drifted closed and my rule rang true: this was delightful. When my eyes opened again, the light in the store had changed. I shifted off the wall, but my dress remained stuck. I pulled and it peeled off slowly, like duct tape. I turned to look; the back of my dress was coated in a muted gray. The paint was wet. The bookstore was closed. How had I gotten in there?

I clomped straight into the courtyard of a cafe. Nina Simone was playing loudly, and it sounded good. A group of musicians and two

young Argentinian boys shuffled at nearby tables. Nina Simone stopped, and suddenly the musicians struck up a loud tango. One of the boys stared at me through his plume of cigarette smoke; he rose and moved towards me.

Do you know how to dance? He asked me in Spanish.

A little, but my car’s coming in three minutes.

However you want…three minutes is enough time.

Another rule: when someone asks you to dance, you should say yes because it is sure to be delightful. The boy took my hand in his and pressed my back towards his potbellied stomach. His smile was gap-toothed, stained, and the smell of his last cigarette was so strong I could taste it. He was maybe twenty three, but his grip was firm. We went on until the song ended: he led me forgivingly, I kept clipping his toe. When we pulled apart, he bowed his head. I went to do the same and noticed a warm, red stain blooming from my chest. My dance partner continued to look at me softly. The red tendrils spread. He didn’t see it.

Illustration by Thisbe Wu

4

Photos by Chela Simón-Trench

by Thisbe Wu

about a guy who wants to sell all his furniture before he kills himself. About a man on a park bench pretending to drive a car. About a man who loses his girlfriend so he follows women who look like her. About piecing together who you’ve been to know who you are.

Am I doing my work?

Ask everyone to send in a video where they pretend to be me. Ask for tracking number from depop. Business as usual. But maybe that’s just because I don’t have much to talk about these days. Committee of selves. Cool concept but something is missing. David was trying to remember this. Do not cry, please! Each of our truths must have a martyr.

Email Daphne. Even our barriers are stuck. Existentialism. Finish YDN. Force yourself into the conditions of art-making. Give yourself a break after this CRAZY week. Gasparra Sampa, Italian poet. Go to post office. Go to student accessibility. Good but something is off. Guilt consumes me. He carried it to the tomb and let it rupture his insides. He feels guilty about it, and yet he can’t stop. He hated their eyes rummaging through his soul. He laid the card down, and the light stayed red. He said, Eli, you can shout at me. He said, God, he has no conscience. He tapped it again, and nothing changed. He was born in the same house he was raised in the same house he was wed in the same house he regressed. He was surrounded by people leaving for the world. He’s slept on a single

Short Story Long #3

Eli Osei

A column about my short story. An Installment about its fodder. Arranged in alphabetical order. Inspired by Sheila Heti. Journal entries, notes app lines, my essays, and the story: stripped for parts to make a new whole. Look at my mind:

mattress his entire life, but he can’t roll off of it now. Her words became mine. His tea gets cold. Hold on to you. How fascinating. I am not bad. I am soon to accept this. I got this story from a fella out west who said he could make me cry with his words. I hate my bedroom. I have wronged many people! I know the feeling. I love black tea. I read on. I spent the first six months of this year pretending to be a Jehovah’s Witness. I want to carry the cross for reasons I can not name.

I will see you! I will understand the world. I’d gone into my first semester of college looking for meaning. I’ll phone again next week. I’m catching up on sleep and emails. I’m in tears.

Is it vain to make carbon copies of your letters? It was all the same thing. It was why he turned towards the Light when his tea began to sour. It’s enjoyable to have something to do. It’s nice to be part of something that people enjoy.

Jonah and the whale. Jonah had to leave. Leave this country? Leave your phone at home today. Less time to do whatever it is I’m supposed to do. Less time to read. Less time to write. Life is long; beauty is everywhere.

Mary was the first Christian. Message Brunella. Message Cal. Message Kanyinsola. Noooo. Now was here, it was there, it was gone, it was fleeting, running, slipping through his hands, it was crushing, a weight on a weight on a weight on a weight, all of which looked like air. Office

of career strategies. Office of fellowships. Oops.

Perhaps those few months of blankness are exactly what I need. Pitch Brink. Remove the man. Return fliphones. Richard Siken and the shrinking gap between writer and reader. Reply to MC.

She is the reader and the writer. She misinterprets your questions because you misinterpret her. She said, We know why we’re apart. She said, Make your own Hollywood. She was marching to the sound of her own splitting hairs. She was mixing her metaphors, and mixing them well. So since we’re human, we have to face it. Someone dreams of moving pictures. Something that means everything. Start small. Stay right-sized. Story about a forensic artist who falls in love with someone she draws. Story about a silent town. Surrealism with Camille! Take Jonah, for example. Take our future out the can!

Talk about the job like it’s yours. Taxes. The body will not be tricked. The courage to be disliked. The future is now. The gaze would not budge. The light went green. The train moved on. There would come a day when all this was gone. Tomorrow. Tomorrow the world begins.

Write Charlie Kaufman a letter. Yes, I would like that very much.

You will die in your bed if you refuse to leave it.

5

Illustration

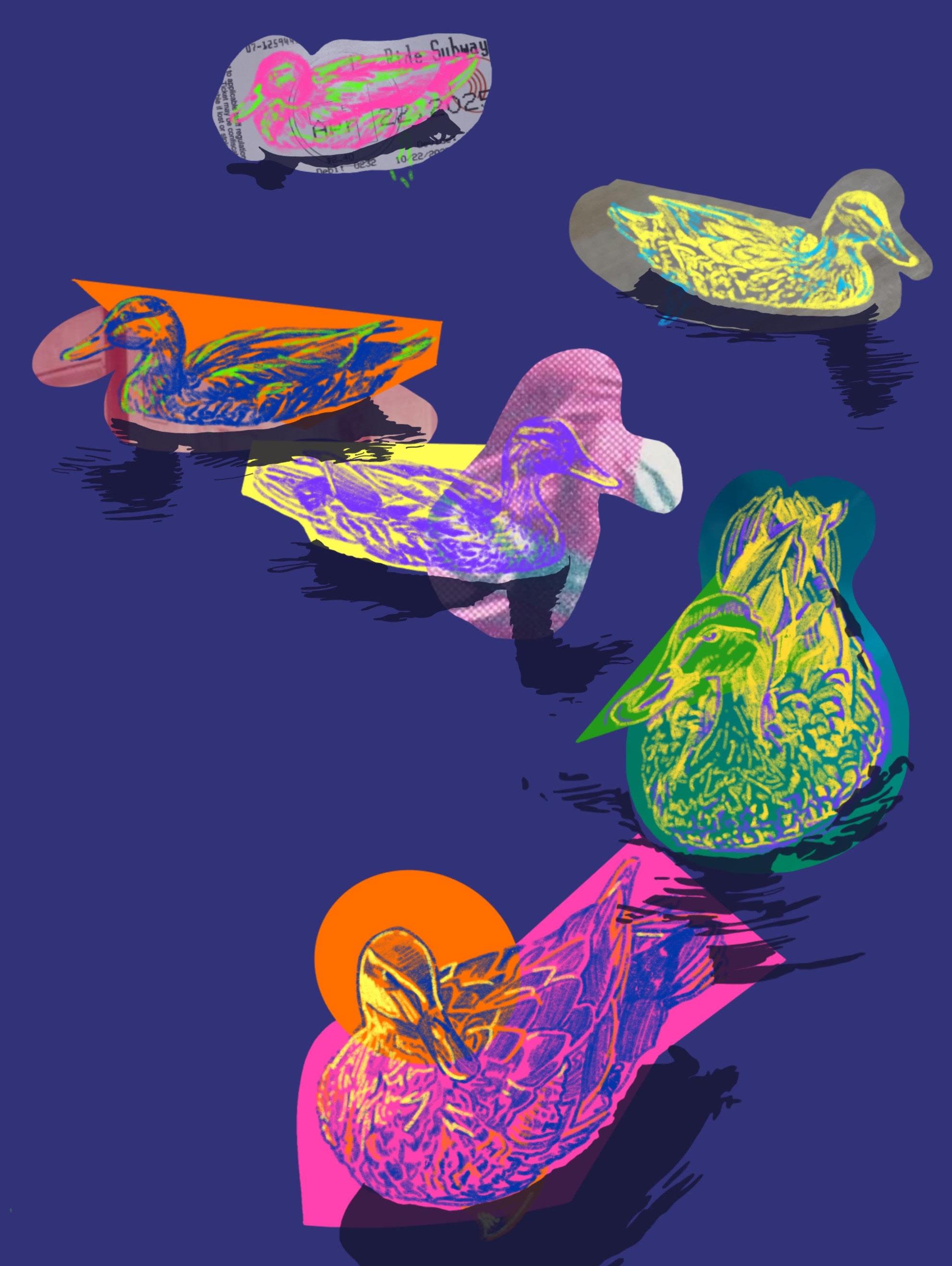

Lyle

& Ophelia

& Betty & Dupree

Audrey Kolker

yDn magazine Co-eDitor-inCHief and amateur bird appreciator Audrey Kolker ’25 talks to banjoist and bird owner Lyle Griggs ’25 about ducks.

AK: Hi.

LG: Hi.

AK: This is Lyle. Lyle has ducks.

LG: I do.

AK: Discuss them.

LG: Okay.

AK: What are their names?

LG: Their names are Betty and Ophelia. These ducks reside in the backyard of TUIB house, or

6

Illustration by Davianna Inirio

Tangled Up in Blue, Yale’s premier American folk music group. And because of that they’re named after characters in songs that we sing. Originally it was Betty and Dupree, but Dupree was killed by a red tailed hawk. Last November, I believe.

AK: Oh dear.

LG: They’re Muscovy ducks. Which is convenient, because that’s the one domestic variety of duck that doesn’t quack. The neighbors haven’t complained. As for why we have them, which tends to be the more pressing question—I grew up breeding poultry. So my family shows chickens and ducks, primarily chickens. So I’m very accustomed to having animals around.

AK: Can you describe the death of Dupree?

LG: Well, the death of Dupree was an interesting moment for me because it reminded me of how accustomed I became during my childhood to animal death. Because I went out and I saw—I didn’t see the hawk hit, but I saw Dupree lying there dead. And I saw a hawk, you know, perched on the edge of their enclosure. My reaction to that situation is pretty muted. My housemates did not have muted reactions to the death of the duck. Which made me feel—so they asked, for example, if I was going to bury it, at which point I had already… disposed of Dupree, in the typical sort of ceremonious way.

AK: In the trash?

LG: In the trash, yeah. But it was a very sad day for everybody.

AK: How did Betty behave?

LG: That was the saddest part. Betty was young. And they had been only with each other for most of their lives. And ducks are very gregarious, and they really pair bond. So Betty stayed by the corpse and sort of kept vigil. And that was pretty sad to watch. And that’s why it was urgent, it was

important that I get Ophelia as soon as possible. Because after an event like that they can’t be alone.

AK: How soon after the death of Dupree was Ophelia purchased?

LG: I think Dupree died on a Tuesday and I purchased Ophelia on Thursday. It was a good excuse to go to Western Massachusetts.

AK: Are there character differences between Ophelia and Betty?

LG: Those dynamics are evolving because when I got Ophelia, Betty was still pretty young. So they sort of had like a younger-brother-older-sister relationship. She was sort of taking care of him. But now he’s enormous. So, I don’t know…. I mean, they’re inseparable.

AK: Well, they’re in a cage.

LG: They are in a cage. But I mean, like, they’re always within like, an inch of each other.

AK: What have you learned, other than…hawks? In this experience of duck-having in New Haven?

LG: I’ve learned that Muscovys are good at flying. One day, I got a call from one of my housemates. And she said, you know, Ophelia has flown away. She was wandering around on Howe Street. The problem was that she didn’t have any interest in being recaptured. But she also didn’t have any interest in leaving. She just flew out, I think, because she was bored.

AK: What’s in store for them?

LG: What’s in store for them? So that begs a couple of questions. First of all, what am I doing with them over the summer? Answer is, I don’t know. But it definitely complicates leaving New Haven because I can’t just leave them behind.

AK: It’s like having a baby.

LG: It is sort of like having a baby. It’s fortunately a little easier than…

AK: You can’t take it on a plane.

LG: Well, probably not.

AK: Do you have words of wisdom for people who would seek to raise ducks?

LG: They can be eaten by hawks. That’s the most important logistical note. As your drunkenness increases, their friendliness does not. As much as you want that to happen. Um, let’s see…they eat a lot.

AK: What do they eat?

LG: Chicken feed.

AK: Where do you get chicken feed?

LG: Tractor Supply.

AK: Where is Tractor Supply?

LG: The one I go to is on Boston Post Road, but Boston Post Road is the closest thing that you can get to hell on earth. I do genuinely think that Boston Post Road—if you keep driving, I haven’t been that far west, but if you drive on Boston Post Road far enough, you will reach hell. There are things that make Connecticut wonderful and there are things that make Connecticut awful. And Boston Post Road is what makes Connecticut awful. It’s like if you were to design an urban space to make people who occupy it want to throw themselves off of the I-95 Quinnipiac River Bridge, this would be the place. Especially on a cold rainy February day.

AK: Mm. When you’re some poor soul buying straw.

7

Birdwatcher Watching Suraj Singareddy

tHere are Certain expeCtations that come along with turning 21. You’re expected to become more mature and to know what you want in life. Really, though, those are distant expectations. The most immediate expectation of turning 21 is, of course, that you will get absolutely, completely wasted. This was my friends’ demand for me on the night of my 21st birthday party. Over and over, they approached me and asked “How drunk are you getting tonight?” To their confusion, and to my mild amusement, I answered, “Well...only drunk enough that I can get up at eight A.M. to go birdwatching tomorrow.” Maybe I was maturing.

The birdwatching trip I had planned was not your average, walk-through-EastRock, see-one-or-two-birdsaffair. No, I was tagging

Photos by Gavin Guerrette

along with a team of skilled birdwatchers as they took part in the Mega-Bowl, an 11-hour bird-watching competition that takes place throughout Connecticut each February. The competition is held by the New Haven Bird Club, one of the nation’s oldest birding organizations.

Chris Loscalzo, a Professor at the Yale School of Medicine and an NHBC member since 1990, would be my guide. He was also the competition’s organizer and the one who founded it eight years ago. He’s ranked 60th in the state on E-Bird — an app where birders track the number of species they’ve seen.

So, armed with less than 6 hours of sleep and the tenacity of a (newly turned) 21-yearold, I woke up at 8:30 AM and got ready to find some fowls. Joining me on the trip were

my friends (and Mag editors) Audrey and Gavin. Chris had texted me to meet him and his birding team — the “Winter Wrenegades” (badum-tss) — by the Amistad Schooner Replica’s home pier at Long Wharf. One quick breakfast stop later, we arrived. We get out of the van and look out at the rocky coastline and the Herring Gulls (yellow-beaked and gray-winged birds) swooping overhead. Audrey wonders out loud which of us will be the first to get pooped on. We make our way towards the pier, walking past a man surrounded by a flock of about thirty or so gulls. He tears off palm-sized chunks of a baguette and lobs them into the waiting crowd.

Chris and his three teammates — Marianne Vahey (his wife, 76th on E-Bird), Judy Moore (71st on E-Bird), and Jack Swatt (58th on E-Bird)

]

8

— have already set up at the pier’s end, where the narrow path broadens into an outlook. With them, they have two spotting scopes, low-powered tripod-mounted telescopes that birders use for spotting otherwise indistinguishable birds. One is pointed out towards the horizon, and the other is pointed towards three birds rocking on the waves, about 50 feet away.

As Audrey, Gavin and I approach, Chris introduces us to the team and launches into an explanation of the competition’s rules; Mega Bowl competitors are tasked with finding as many species of birds as possible within the hours of 6:00 AM and 5:00 PM on a designated day. The birds range in point value, with the most common valued at only one point and the least common valued at seven. “And then seven — touchdown! Seven points is if you find a bird that’s, like, never been seen in Connecticut, in February, before,” Chris tells us. On the scorecard, the 7 point slots don’t even have birds listed next to them. They all read “7 ______________.”

Chris gestures towards the scopes. He takes a look in to adjust the lens for us. “Might be able to see — oh, wow — there’s a whole flock of birds that are called lesser scaups.” They are black-headed ducks with wings striated in black and white. “That’s a three point bird,” he adds.

For each point that a team earns, Chris and Marianne donate 50 cents to an organization of the team’s choice. By the end of this year’s competition, they’ll have donated 1,050 dollars to various organizations including the Connecticut Audubon Society, A Place Called Hope (a bird rehabilitation center in Killingworth), and the New Haven Bird Club itself.

Having logged all the birds at this location, the Wrenegades pack up their scopes and begin walking back to their car. Along the way, I ask Chris how long he’s been birding. “I started 50 years ago, I’m 64 years old.”

“I was about 12 or 13 years old, and I lived near a horse farm,” he says. “Anyways, there’s this little old lady who owned a horse, and she couldn’t take

care of it. So she asked me and a friend ‘Hey, can you take care of our horse for us?’ We said ‘Sure, of course.’ Anyway, as a way of thanking us, she invited us to her house [...] and she had bird feeders. She was putting birdseed in, and I was amazed at all the different birds right there. I’d never seen so many birds.”

He goes on to tell me about his spark bird — the species which got him invested in the activity. “It was probably the Red-bellied Woodpecker, and after that it was Evening Grosbeak. That was the one that really got me going. A really spectacular looking bird.” Later, after getting home, I google the Grosbeak. It is a small, terrestrial bird of gold and black. A yellow line traces across its forehead, and its mustard underbelly comes up into sharp, black wings. I forget, sometimes, that there are things more vibrant than paint.

We head next to the Sound School — a self-described “regional, vocational aquaculture center” located 1.5 miles away — and see a few Red-breasted Mergansers, black

9

ducks with long, red beaks and mussed feathers along their heads. “Doesn’t it look like they’re having a bad hair day?” Chris says.

We stay for a few more moments, and then we pack up and head to Oyster River Point, a suburban street that comes up right against the ocean. A woman living in the neighboring house comes out to ask what birds we’re seeing.

“I only see the ones closer because I have regular binoculars,” she says.

“You can come and see him in my scope right now,” Chris replies. He waves her over, and she begins to look at a few Wigeons — brown ducks with black-tipped wings and brilliant green streaks across their heads. They bob on the waves, occasionally tipping their body over to search for food underwater.

While Chris points out more features, Marianne waves me to the other scope so I can get a look. I ask her about how she and Chris met, and she

tells me they met in medical residency. At the time that they met, Marianne was not a birder. However, a few months into dating, Chris began to pish — a bird call used to bring out hiding birds — while on a walk. An Eastern Towhee jumped right out. It was (birding) love at first sight.

Our penultimate stop is Merwin Point in Milford. We get out of the car to find ourselves in yet another suburban neighborhood on the coastline. Black rock juts out along the shore like it was made of liquid and frozen midair.

I walk with Judy along the shoreline as the others go ahead. She began birding later than Chris and Marianne. “One day I left my son at nursery school, which was right next to the woods and a park,” she tells me. “It was early and I just sort of stepped inside the woods, and all of a sudden all these birds surrounded me and we had what we call a fallout of spring warblers.” A fallout is when many birds descend from

the sky and onto land, usually caused by rain. “There must have been species of these… and I was just smitten,” she says.

Suddenly, Judy points in front of us. “Sandpiper at the very tip of that rock.” 3 points. Chris and Jack dash to set up the scopes to see if they can spot it, and Jack realizes that there’s actually a whole flock of them lurking on the rock’s other side, only visible from further back.

We wait for a few more seconds to see if they’ll walk out to the front, but they refuse. So the scopes are packed and we begin to walk back to the cars.

About a street away, a brown streak shoots overhead. “Cooper’s Hawk!” Chris shouts. We rush around the corner, hoping that the whole team will be able to see it, but it isn’t there.

The next day, I walk out of LC to find Cody Limber, my ride to the celebratory dinner

10

who’s ranked 55th on E-Bird. On the 27-minute drive to the dinner held in Derby, he told me about his research as a PhD candidate in Richard Prum’s Ornithology lab. Cody had taken his love of birds full time. By day, he researches the categorization and development of feather cells in chickens, and by night and by weekend (and sometimes by day, instead of work), he chases birds. “Birders do very silly things, and sometimes that means driving like an hour each way to see one individual bird,” he said. In fact, that’s what he’d been doing before he picked me up. He had driven an hour north in search of a Hermit Warbler which another birder had spotted and was returning victorious.

As we drove, Cody craned his head close to the dashboard each time a bird passed overhead, pointing out each one. I asked Cody how far away he could identify a bird from.

“Depends on the birds,” he answered, before admitting, “Yeah, pretty far.”

We arrived at the dinner’s venue, the Kellogg Environmental Center. Inside, past a small, wood-paneled lobby, laid a large room filled with taxidermied birds, wooden, whale models and, curiously, a small pond. In it, two turtles — one the size of my palm and the other the size of my head — bobbed around.

We walked past the turtle pond and into the center’s banquet hall, just as Chris was telling everyone about the food. Marianne had made it all: rice, meat and vegan chili, vegetable stir fry, pumpkin soup and chicken noodle soup for about thirty people. Flannel, as well as patterned shirts and puffer jackets, was popular among the gathered birders. I was one of the only people of color. Later, Chris attempted to find out who the oldest and youngest birders in the crowd were.

When he said “keep your hand up if you’re over 60,” half of the crowd’s hands were still up.

These demographics aren’t news to Chris. The day before, as we walked along Merwin Point, he’d told me “It tends to be somewhat affluent, Caucasian people that tend to be birdwatchers. You know, it’s hard to be a birdwatcher if you’re just working every minute just to make a living and put food on your table. Yeah, it’s a privilege to be able to do this on a day off and have fun.”

In addition to a difference in free time, birding’s lack of diversity also seems to stem from the racism of its pioneers. John James Audubon, a pioneering naturalist and the Audubon Society’s namesake, was a slave owner. William Cooper, the namesake of the Cooper’s Hawk, was also a slave owner. That’s why, last November, the American Ornithological Society announced that it was taking Cooper out of the hawk,

11

along with changing the name of every bird named after a human. They hoped this change would “engage far more people in the enjoyment, protection, and study of birds.”

Although the change isn’t without its detractors, Chris instead sees it as an opportunity to give birds more appropriate noms de plume. “Some of the best bird names give you a clue as to either what habitat they like, color, or, you know, plumage feature. They have a purple head, you can call it a Purple-Headed Warbler.”

Cody and I sit down at a table near the front of the banquet hall, next to other birdwatchers who were friends of Cody’s. There’s a bowl of m&ms in front of us, and I feel a bit like I’m eating birdseed as I pick up a few in my fingers. The three birders begin to chat about owl feather evolution, before switching topics to chicken plumage and then to bird banding.

Soon, Chris comes to the front of the room and begins a small speech about

the competition’s history and where this year’s donations were headed. Then, he moves on to the competition’s results. Cody’s team — “Egrets, I have a few…” — had won one of the top prizes. The rest of the room groaned in response to the announcement. This was a yearly occurrence, I guessed.

After Chris hands out the prizes — bird paintings and suet feeders — for the top teams, he thanks everyone for coming, and people begin to pack up. At Chris and Marianne’s insistence, I pack some food to go while Cody talks about his Costa Rican birding experience with Chris.

Campus is cold compared to the warmth of the birding dinner — indoor heating and people who know each other. The generosity of the birders is not lost on me. Allowing three college students to tag along on their birding expedition and pelt them with endless questions is a kind act. These birders, like anyone else, want more people to love what they love. Despite this kindness,

though, I don’t know how long it might take to feel part of this community. There are the facts of representation, racial or otherwise; and there are the facts of dedication. If I started now, I would be 71 by the time I had as much birding experience as Chris. Maybe this will just be the story I tell myself in 20 years when I try to remember how I spent my 21st birthday — I saw some birds, I met some people, and I tried something new.

A few days later, the weather is nice enough for running, so I slip on my sneakers and jump outside. The birds — tucked, out of sight, on some tree branch — are especially loud today. I pull out my phone and open MerlinID, a bird call identification app. I press record. American Bluejay. I try looking for their blue feathers again, but I can only hear their caw

12

The Moth Collector Nicole Viloria

one sunny afternoon in their Miamian second-floor apartment, a big black moth paid Nathalie and her dad a visit. Nathalie thought the moth was beautiful. She said to her dad, “I want to get that tattooed on me!” She later found out that their little visitor had been la mariposa de la muerte, the Black Witch Moth. According to the Aztec myth, the first person in a room who sees the flying animal will die.

Illustration by Neve O’Brien

Illustration by Neve O’Brien

Nathalie didn’t think much of the incident until the prophecy came true. Her dad passed away the following Christmas. The moth is now drawn on her stomach. For many people, butterflies are a sign that a loved one is watching over you, but not Nathalie. For her, the sign is a moth. Every time one enters a room, she thinks of her father.

Nathalie Saladrigas is a Latina activist for LGBTQ+ rights, Community Organizer, and Miami native with Cuban and Colombian roots. She also commemorates the deaths of animals, from rats to lizards, pigeons to moths. Nathalie and I briefly spoke about her appreciation for the morbid when we first met at Miami Dade College, but. Hearing more details about dead creatures triggered me. So while we got closer, I’dve always been a little hesitant and, frankly, scared to know more. Now, reflecting on the loss of my uncle, I felt brave enough to bring up the topic again. So, I called her on Zoom, and I got the chance to put all the pieces together to discover another side of my dear friend.

NICOLE

What is the origin of your interest in moths?

NATHALIE

Yes, moths are very special to me. When I was younger, my professor gave us this jar of dead moths, which is the one that I kept since middle school. He made me sort through them all to check for different types of moths. I asked him if I could keep the jar. And I

kept it for years and years. So, that’s when it started. I started doing my graffiti tags with moths. I think they’re really beautiful. I liked how they keep coming to the light, and how they are just there floating around all of the time. I really liked them because they were everywhere.

NICOLE

Could you share a little bit more about your experience with grief?

NATHALIE

My first experience with grief was during the deportation of my mother. My mom being deported, having to stay in Colombia, and grieving not being able to be with my dad. That was the second instance of this pain and separation: Grieving the idea of what a family is supposed to be.

And then, my grandma passed away. I remember when I was in elementary school, I told the school therapist, “I don’t want to get close to my grandma because I’m scared she’s gonna die.” I think I took more of an avoidance stance, where I don’t want to get close to people because I’m scared, if I get too close, they’re gonna pass away.

Even through my grandma and my dad passing away, the stance I always took was a form of appreciation. I would get things that they gave to me and keep them. Like jewelry, photos. And commemorate them in that way. With everything; animals, insects, anything. I try to keep from them, so I can commemorate them in that way.

NICOLE

What do you think happens to the essence of dead beings?

NATHALIE

I never think that the essence goes away. For me, essence is the energy that they leave behind and the energy that they are. Their physical selves are not gonna be there ever again. But you know how they were, you have experiences with them, you lived with them, you were able to experience their love. And that’s their essence. That’s never gonna go away because you are always gonna feel them, in any way. For me, a moth comes into my room and I’ll say, “Wow, that’s my dad.” To this day, I know my dad is protecting me and is looking over me. I never killed him. I never did that. I never thought I lost my connection with him. I still have that.

NICOLE

Could you talk about your views on death and what deathit means to you?

NATHALIE

Death is sad. My parents used to tell me: you don’t know anything. All you know is that you’re gonna die. And that’s it. I always took that to heart.

It just happens. Things happen. You live, you learn, you love. You live this life, understand a lot of things, and then you die. It’s something really natural to me. It’s something I don’t try to fight against. I am just happy I am here right now and I know I am gonna die one day and that’s it.

I am glad to have been here for this long, I am glad my dad was here for this long. I am glad this animal was here for this long. You just appreciate it and find ways to connect with it. Like I’ll wear this moth-shaped necklace holding a locket with a photo of my dad and of the moth that came into my house. I did a tattoo based on my dad. I take pictures of animals. I commemorate it and then I accept it.

I know death is there and that it’s coming, but meanwhile I just accept it and appreciate it.

13

Morning Walk Gavin Guerrette

in tHe gray morning light, I walked through the forest behind my father. I dragged my hands across the moss that grew up the sides of trees while stepping over stones and logs. The barrel of my father’s rifle bounced atop his shoulder with his stride. I had no gun and preferred it that way. I possessed a serenity, then, only possible until one’s parents are rendered fallible. That first look of fear upon the face of one’s mother or father is the wellspring of all uncertainty.

My father had come into my room earlier that morning, and pulled a hunting cap onto my head while I rubbed the sleep from my eyes. Wear two pairs of socks, he whispered. And lace those boots nice and tight. In the kitchen, I watched him fill a canteen from the sink. He turned to me and said, We’re gonna shoot ourselves a deer. I fought to hide my smile. My father crossed the kitchen and pulled my cap down over my eyes. You’ve got a mean look about you. It’s a bad day to be a deer. I laughed then, and the smile remained.

Once we left, I faded in and out of sleep as the headlights of my father’s truck cut a bright path through the dark. He woke me to watch the sunrise. We looked out in silent awe as the truck cabin filled with orange light. You were up before the sun. I slept once more and awoke to my father closing the driver’s side door. Around us, tall trees were steeped in pale light. I hopped out while my father drew his gun from a long green bag. Then he slung it over his shoulder and

we trudged deeper into the woods.

With a furrowed brow, my father tracked us a deer while I collected sensuous facts; he inspected the trees, and I caressed them. After an hour of walking, we reached the edge of a clearing. Golden sunlight illuminated the morning fog which hung just above the grass. My father knelt and I did the same. He extended a finger down towards a mound of black pellets. Deer droppings. He then brought that finger to his lips. I nodded. He rose from his knee but remained crouched, sliding the gun from his shoulder into his hands. We crept along slowly, eyes peeled for a deer.

After a moment of hushed prowling, my boot fell upon something with a crunch. Lifting my foot, I shrieked and quickly covered my mouth. Amidst the clearing, a deer’s head lifted above the grass. It turned to face us and vanished in three bounds. Between my boots, there lay a twitching little bird, its wings cracked and jagged. My father approached. Ah, just a baby. He lifted my chin with his hand. My eyes met his, but he kept on lifting. I followed his other hand, which pointed towards a nest in a nearby tree. Three chicks sat with their small beaks open towards the sky. Above them stood a larger bird looking down. Must have fallen from there. Go and grab me a rock. I looked to him in terror; he set his jaw and nodded. I fetched a rock and turned my back as he took it from me. I felt his hand fall gently on

my shoulder. I was taught this is merciful. You may disagree, but it makes no difference unless you’ve seen for yourself. I turned back around slowly. He raised the rock overhead. The little bird twitched below. He brought it down hard with a grunt. I winced. A limp wing protruded from beneath the stone, utterly still. Peace in exchange for life. Though the peace was ours to enjoy, which disgusted me. I heard chirps and squeaks from the nest above. Did you see where the deer ran off? I pointed in the direction I had watched it flee. My father hoisted his gun back onto his shoulder and we continued our tracking. Moving for some time through the woods, we came upon the freshly mauled carcass of a deer. It was laid haphazardly to rest against a mossy tree. I retched on my hands and knees at the sight of it. My father stood at my side until it ceased. I looked at his face; even then, his jaw remained set and his eyes stared straight ahead. How about we head home? Today isn’t our day. I nodded, feeling my shirt wet with cold sweat against my back. He handed me the canteen and I drank greedily, still on my knees. I’ve got some food back at the truck. Should make you feel a little better.

We retraced our steps, and I watched my father looking around as we walked. He moved with subdued haste, so I had no time to touch the trees. I only remained at his heels with great effort. The morning haze waned now, and the forest stretched itself awake.

14

by Anna Chamberlin

Animals rustled in the brush beside us and birds sang in the trees above. The day was kind to me and offered many sensations to distract from thoughts of the deer. Sunlight reached us with greater conviction, illuminating the once shaded path we had walked. In places where the ground was soft, I could see our footprints pointing opposite the way we now went.

I lagged at the sight of our own tracks. My boot prints looked so small next to my father’s. I found it odd how big I felt in my own body. I moved to continue walking and saw my father many strides ahead. I hastened to catch up. Hearing my footsteps, he looked back over his shoulder. Our eyes met for an instant. Then out from the trees, a hulking brown mass swept my father to the ground. His gun fired as he landed, causing the beast to flee. I ran to my father, who lay sprawled on the ground—a red mound atop a bed of lush green. I forced my eyes to meet his. They

were open and frantically alive. His face was as I had never seen it, wrought into a look of pure, desperate terror. I crumpled to the ground. He made shaky wet gasps for air. I listened to that sound, until I could take it no more.

My father’s rifle laid beside him. I crawled to it and clutched the woodgrain tight. Rising to my feet, I reloaded the gun as I had seen him do many times. I leveled it to his face and looked down the sight. Not even a wince from the barrel leveled between his eyes. I looked once more at his mangled torso, then back to his face. I shut my eyes tight and pulled the trigger. Click. Nothing. I tried again. Click, click. It wouldn’t work. I threw the rifle to the ground.

My pulse beat deafeningly loud in my ears. Falling to my knees beside my father, I took his blood-soaked hand in mine. While the sun crept across the sky and his grip became faint, I stared into his fear-stricken eyes. When the strain had left his face, I released my father’s hand and stood. Following our path through the woods, I walked back to the truck.

15

Illustration

Naming Birds Lazo Gitchos

a HarD rain rips at my tent. It sounds like Velcro. It’s hot inside but my feet are cold. The summer days are impossibly long between white Arctic nights. The wind blows like the sky has been slashed open and is deflating, filling the wet emptiness below with more air than it can hold. In a place already scoured there is nowhere to hide from the wind, and the rain falls out of the bottom of thick fog. It feels as if my clothes may never dry. The flowers on the grass airstrip are saturated purple. There are more than yesterday. The tundra is “greening up,” cottongrass blooming little white poofs in their flattened, ancient toupees of dead plant matter. Some tussocks are tall, 18 inches or more, and the buds on shrubby willows are just now shooting. It’s late June and I am in Alaska’s Brooks Range, counting birds. On survey, I look down

to avoid crushing the pink and blue and purple flowers, or else I look across the valley at the mountains colored by the clouds on the horizon; Jeremy looks down at the GPS, or else at the bushes for birds. He identifies the species by song. I record it on a clipboard. He told me the birdsongs we heard from golden-crowned sparrows might be unrecognizable from members of the same species a few hundred miles south. They have regional dialects, accents, he says. These birds are song-learners: they pick up their song from adults of the same species when they are young. Geographically separate populations, if apart long enough, sing different songs.

I ate dinner with John A. Nash in Fairbanks in late May, a few days before we went into the field. We were both on our way north to look at birds; John

to Utqiakvik, Alaska (the northernmost town in the United States) to study nesting shorebirds, I to a field camp in Noatak National Preserve to count migratory songbirds. I was headed to Noatak to ask questions about bird science, John to answer them. He reminded me to keep an eye out for the gray-headed chickadee, presumed locally extinct in the Western Hemisphere but last sighted in Noatak in 2016.

Since last summer John has, like me, returned to Yale for his senior year. He co-published a paper in the International Journal of Avian Science with other ornithologists including Richard Prum, author of The Evolution of Beauty, presenting evidence that a pigeon collected on Negros Island in the Philippines in 1953 constitutes its own unique species: Ptilinopus arcanus, the Negros Fruit Dove. John and four

16

Photos by Lazo Gitchos

other scientists gathered this evidence through analysis of DNA collected from the toe pads of the preserved bird, the only known sighting of the species, which is held at the Peabody Museum.

John, the sweetheart of Yale’s ornithology department (due in equal parts to his outsized contributions to the field as an undergraduate and his epic mullet), says that one of the most important debates in genomic analysis right now surrounds the species as a base unit of taxonomic analysis. The most widely shared definition, called the biological species concept, holds that two organisms belong to the same species if they can reproduce viable offspring. But John says that definition doesn’t account for species like the Brewster’s warbler which, though morphologically distinct from its two parent species, the golden-winged and bluewinged warblers, can breed back into either of its parent species, and is also viable on its own or with another variation known as the Lawrence’s warbler. Biologists, including ornithologists, have a hard time agreeing on what constitutes a species; reproductive isolation,

geographic isolation, morphology, and behavior are all individually insufficient to differentiate species.

Physical characteristics can diverge very quickly within the same species in response to changes in environment, remain very similar in isolated populations without species divergence, or even converge from distant evolutionary paths based on evolutionarily-conserved structures. The February 19, 2024, New York Times article “What Is A Species, Anyway?” addressed the discordant ideas in the field. Newer biological inquiry, John said, increasingly focuses on the subspecies because less is known about the finer distinctions. “A bogeyman in evolutionary science is defining ‘what exactly is a species?’... there’s not necessarily agreement over what that threshold of difference is.”

The airstrip, where we were dropped off and made our camp, showed off a smattering of purple flowers which had cropped up on the stems of the low rhododendrons. They were delicate and thin-petaled with woody sprawling stems. They made the place feel less hostile to life, but the stems only es -

cape the incessant grazing of Caribou because the leaves are toxic. The rhododendron family is an empire of species, its thousand-plus members extending across much of the arable land in the world. Here they are low and crawling, punctuating gray-green grasses. Labrador tea, an aromatic shrub in the rhododendron family, is common.

The process of classification by which all rhododendrons have come to be associated under one genus isn’t particularly recent; taxonomy as we know it has been around since 1735, when Carl Linnaeus articulated the binomial latinate naming system which we still use. Taxonomy, for plants and animals, relies on the observation of physical characteristics and behavior, properties of reproduction, and similarities in the structures of organisms. For hundreds of years, taxonomy was the best available scientific tool for classifying organisms in the natural world. But recently, with the introduction of genetic analysis, a new field of classification has emerged. Genomics, which seeks to track the evolutionary origin of organisms through DNA, often aligns

17

with taxonomy and has been incorporated into the existing categorization system. While taxonomy was about understanding the natural world, genomics seeks to advance our understanding of evolutionary history. Compared to taxonomy, genetic analysis aims at a deeper, clearer understanding of the natural world—“evolutionary history is not necessarily the accumulation of externally perceptible differences,” John told me. Genomics can help expose evolutionary history that may not present itself to the human eye. Still, John reminds me, “there’s no such thing as a perfect [phylogenetic] tree.” All the best analyses rely on assumptions and inferences, including the level of difference at which a group of organisms qualifies as a new species, and the level—species or something smaller—at which the organism is worth studying. These are human decisions, subject to incomplete understanding.

In Alaska, Jeremy, Jared (a field technician) and I start the count before 3 a.m. To the north, the sun is still sinking towards a high ridge, boiling in the clouds over the continental divide. As the morning gets on, the temperature drops. The light does not change. By 3:15 the process slows, reverses, and the sun imperceptibly begins to rise. It is always cloudy over that ridge to the north, so it does not warm until nearly 6 a.m., by which time the survey is nearly half done. We walk back to camp as the sun climbs the hill to the west, away from the notch to the north that

marks solar midnight. When the surveying day is done, Jared’s eyes stay glued to his binoculars, hoping in vain for a little gray-headed flash in the shrubs.

Jared told me that his dream vacation is to go to Argentina and look at Pumas. Pumas, he said, are the same as mountain lions, which are the same as cougars, and they have the widest geographic range of any terrestrial mammal in the western hemisphere. Linnaeus, our original taxonomist, creatively called it Felis Concolor, which means ‘uniformly-colored cat.’ It holds the world record for most names given to a single species, at over 40. Early genetic analysis in the ‘80s discouraged the idea that there were multiple species, but divided the existing population into six geographically-defined subspecies, including the Florida panther (which is not a member of Panthera). But genetic testing has advanced a lot in the last few decades. “If you did [additional] genetic testing,” Jared said, “you might find that the ones in Argentina are different enough from the ones in North Carolina which are different enough from the ones in British Columbia to be considered multiple species. But for now, we’re in a beautiful moment where they’re all one species in a huge diversity of ecosystems and climates.”

On a ridge up the valley from camp, past the 1982 US Geological Survey marker, there is a midden of rusting steel barrels painted army green. They predate the survey marker and the National Preserve designa-

tion. And, because they were discarded more than 50 years ago, there is no imperative to remove them. Such is the rule on federal land: if it’s been there long enough, it’s a part of the landscape. So, the trashed fuel barrels of a bygone petroleum prospecting expedition have joined the caribou skulls, willow shrubs, and marine fossils as federal property. Dave Swanson, a soil and vegetation ecologist with the Park Service who joined for a part of the survey expedition, was born around the time the barrels were emptied and tossed. “I better retire soon,” he told me, “before there’s litter from my early career that I’m not allowed to pick up.”

Land conservation designations are as impactful, and as human-delineated, as the fine grained species questions. Both make subjective, relational experience more concrete and universal. “Phylogeny always has a purpose… especially as the Tree of Life [the evolutionary history of all organisms on Earth] gets worked out, there wouldn’t necessarily be a reason to just keep sequencing,” John said. But we’re still at a point in our understanding of phylogeny that finer and finer analysis is useful to biologists.

A plant that was common near our camp has recently been reclassified as a kind of rhododendron, or else is no longer considered a kind of rhododendron, I can’t remember. Nothing about the plant changed in the process. It happens with birds, too. Some of the birds we saw may be genetically distinct enough from other,

18

more southern populations to be distinguished at the species level. But without thorough genetic testing, it’s moot. According to current scientific classification, the Siberian tit and the grey-headed chickadee are both subspecies of Poecile cinctus. But in Alaska, the grey-headed chickadee is presumed extinct, while the Siberian tit is still common in Europe, which via the Bering Strait is not all that far. Depending on other thresholds for genetic distinction, the two might be independent at the species level. If so, the grey-headed chickadee would likely be treated far differently.

The morning we flew out, it was calm and sunny, and the pilot brought a bigger plane to get us in one trip, rather than the three it took to drop us off. It was his first time landing the 1953 De Havilland Otter on the grass Kelly Bench strip. We loaded gear and steel food

barrels, tubs of data sheets and finally ourselves. We plugged our helmet headsets into the overhead jacks. The pilot taxied down to the end of the bench, the plane canted up toward the sky, its tail dragging on its wheel. We sat a moment. The pilot reached down for the throttle and we began to move. The wind was ahead, blowing down the Kelly River valley and across the bench and under the Otter’s wings. The throttle and the wind were barely enough. We neared the end of the strip. The bluff approached, and the pilot pulled the throttle forward, and forward. The plane pitched forward as the rear wheel lifted, and we saw that we were approaching the edge. The bumping lessened then ceased and the wheels left the ground. The pilot’s voice fuzzed over the headsets: “looks like we had about 25 feet.” He laughed. The Anchorage airport, 600 miles south, is named

for Ted Stevens, an Alaska senator who died in a plane crash, in the same kind of plane.

In three weeks we had seen 50 kinds of birds. Golden plovers, jaegers, and whimbrels made nests on the tundra near our camp. Harriers dive bombed us, defending their nests. We saw short-eared owls and rough-legged hawks hunting for lemming in the little trenches the rodents make by their constant running. We counted sparrows and warblers and bluethroats and other singing birds in the shrubby creek bottoms and on the barren ridges. We saw bears and caribou and a porcupine; we didn’t see the gray-headed chickadee.

19

Feeding the Birds

Sophia Ramirez

WHy is it alWays only old people feeding birds? They’re reclining the morning away on a bench, while we’re here, prime of youth, cramming for tests and running clubs and busy-busy-busy—it’s so played out. There ought to be at least one college student out there, on a bench, sitting silent, just tossing some bread around. Switch up the age demographic. So today I’m walking through the Green, a stash of dining hall pita bread in my pocket, on a mission to find birds.

There aren’t many, on account of it being winter. We’re deep into stiff-ground, stick-naked migration season, and maybe a more professional ornithologist would’ve taken that into account but c’est la vie. I wander birdless for a solid five minutes. That might not seem long but it is, especially with passer-bys about casting glances, and then more glances, because there’s no one on the grass but me. And also I suppose someone playing with his dog, but at least he has an excuse, a dog, while all I’ve got

is some pocket pita, and he doesn’t even know about that. All he sees is some college student that’s been wandering in circles for an awful while now, dare he say five minutes, staring inanely up at the sky like she’s lost something in the trees.

But then finally I spot one, a bird, up in a branch. She’s a cardinal. I know she’s a she because she’s got all the color drained out of her and that’s what the females look like, just a bit of red on the nose and the wingtips like someone out in the cold for too long. The rest of her is this gray, not a nice soft one but pretty dull, brownish, like a rusty nail, a rain pipe, a fork that’s been through it. But I’m not going to be picky—I tear up the pita bread and scatter a couple of pieces on the ground in front of me. No response. I toss a couple more down. She turns her head to give me the side-eye, and I know that’s just where birds’ eyes are but this one feels pointed, and when I reach into my pocket to grab some more bread she’s gone,

she’s done with me. I watch her flap away to another tree a couple feet away. It’s a low moment, I know it, when I bend down to pick up the bits of bread I put on the ground, walk a couple yards, stand below a new tree, and throw the bits of bread back on the ground again. Still: not a chirp of a reaction. Maybe I seem too alert, standing up? Too ready-to-pounce? The old people usually have their benches. There are no benches around, so I sit down on the ground beneath the tree, stare up at the bird, and I wait, zen-like.

The dog darts by me. The owner chases after it. Deep down, I know: this bird’s not coming down. She whistles, and I get a sense that she knows what’s going on. That I’m trying to get something out of her. The old people, they don’t have an angle, an agenda, a plan of action that they started executing in the bread section of the dining hall. The old people don’t contrive or force it or run—they let it all come gently to their palms. Whatever they’ve got, that patience, that ease with time, I don’t got. And the bird knows it.

I get up, pick up the pita pieces for the last time, and turn to leave. Maybe I’ll try again when I’m older: I’ll wake up and pull my tired body out of bed, in the cold light, in the quiet morning, and take yesterday’s loaf to the park to feed the age-softened, long-feathered birds there. Not you, though. Bread snob.

20

Illustration by Davianna Inirio

Trash Birds

Molly Hill

like many birDers, I have a particular fondness for hawks. Each fall, migrating raptors often gather by the dozens or hundreds, and dedicated observers count them at hawkwatches along their migration routes. Lighthouse Point Park in Connecticut is home to one such hawkwatch, and I spend as much time there as I can during the fall.

But when I visited one morning in early October, the hawks weren’t flying. So instead of standing at the hawkwatch, I headed towards the beach. Despite being possibly the last warm Sunday of the season, the beach was abandoned to seagulls. There were seven Herring Gulls, who were starting to replace their crisp breeding plumage with ratty winter feathers. One Great Blackbacked Gullstood a few feet apart –a hulking, caped giant. A few Laughing Gulls, thin and graceful, flew over the water. The rest of the beach was taken by about thirty Ring-billed Gulls. These little ones, with their rounded heads and big dark eyes, were dwarfed by their larger cousins. By contrast, the herrings seemed all angles, giant proportions, and long sharp wings: they looked almost raptorial. The hawkwatchers, staring up at empty skies, were missing out.

“Most birders don’t care about gulls at all,” Andrew Birch, a prominent Southern California birder I’ve known since high school, told me. “Even among experts there’s a shocking lack of interest.” Birch, however, has spent years watching gulls, and when I asked him why, he smiled and said with no hint of irony, “They’ve got great personality! They’re maybe the only family of birds that are really playful.”

Yet it is precisely their playful antics that are reviled by much of the general public. My dad calls them “rats with wings.” Asked about gulls, a friend shook her head: “They steal my food… Also a seagull peed-slash-shitted on my cousin’s head.” And for ornithology professionals these days, gulls are a risky subject. Yale

ornithologist Liam Taylor, who recently submitted a paper about the history of gulls in the United States, isn’t sure if he hopes it’ll be published or not, because if it is, he and the coauthors might face ‘negative consequences.’ One of his coauthors, Wriley Hodge, agreed, with a wink, that if it’s published, “the Seabird Institute will never hire [them],” and they might both be “blacklisted” by East Coast waterbird researchers.

Gulls, I have learned, are inherently contradictory. Their lives are webs of violence, yet they care for their partners and chicks with affection. They’re smelly, fishy, trash-eating, aerodynamic wind-dancers. They feel fury, and, apparently, have fun. They are loved and hated. I struggle to describe them in any meaningful way without equivocating: they are a bird associated with such intensity, yet for many people, they are nothing more than set dressings for a beach.

I entered the world of gulls this May, when I spent a month studying a Herring Gull colony in New Brunswick, Canada, at the Bowdoin Scientific Station on Kent Island. My first impression of the colony was its magnitude: thousands of gulls crammed together on a mile-and-a-half long island, fighting and courting and feeding and swooping and all of them, at any hint of disturbance, screaming. The other researchers and I were offered hard hats for protection when the gulls dove at and kicked us with – literally – stunning strength, though the hats did little to protect us when the gulls shat on us from above. On my second day, a gull bit my hand badly enough to leave a scar. Even when I wasn’t being assaulted by gulls, Kent was freezing and wet and perpetually windy; the rocky, muddy, jagged beaches were alarming to maneuver across; I was disturbed to discover the ground littered with gull bones, evidence of the brutality of their lives there. I don’t even like nice beaches. Why had I decided to spend my summer studying seagulls?

Out of necessity, though, I settled into the rhythm of research. One of my assignments was to track the development of a single nest: every day, I visited it and recorded the growth of the developing embryos. I became

familiar with its parents and the aggressive rituals they’d display while I worked. They looked comically furious, throwing back their heads, puffing out their necks, and bellowing a “trumpet” call. The eggs hatched on my last day at the station, and I marveled to hold the chicks in my hands. They were little more than mops of spotted fuzz, still damp from their eggshells. I was sorry to leave them and their parents behind.

I met Wriley Hodge months later. A student at the College of the Atlantic – a college in Maine prone to producing gull-enthusiasts – Wriley had spent the past three summers researching a similar Herring Gull colony at the CoA field station on Great Duck Island, Maine. When I asked them why they loved gulls, they turned reflective: “You can have all these preconceived notions about them as a nuisance. And then you live with them, and you see them building their nests, flirting with each other and raising their young and being such good parents… I think that when you live with something, like a colony of gulls, it’s hard not to fall in love.”

I had gone to Kent Island to perform research with the aforementioned Liam Taylor, a doctoral student in Yale’s Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Department. I first met him on a cold day last winter, while looking for a field biologist to do summer fieldwork with. He fit the bill: bearded and beanied and prone to soliloquies, he wears sweaters in earth tones, orange-khaki pants, and a big waterproof watch.

When we met, Taylor explained that he studies a particular aspect of gull adolescence: delayed plumage maturation. Gulls don’t breed until they’re a few years old, and during this time, the young molt through a series of distinctive

21

immature plumages before growing the definitive feathers of breeding adults. The purpose of these plumages is not known, as gull adolescence has received “shockingly” little attention from ornithologists. Taylor, who had witnessed young gulls visiting the Kent Island colony despite not breeding themselves, believes their feathers might function as social signals. By signaling their age, young birds might deflect aggression from breeding adults, giving them space to develop social skills necessary for colony life. Essentially, their immature plumages say Don’t mind me, I’m just here to learn.

On Kent Island, we used plastic birds painted like different Herring Gull age stages to test this social signaling hypothesis. We’d walk to a stretch of beach, place a model close to a nest, and record the response of the parents. We used gull decoys at three different ages, plus a goose decoy as a control, so we returned to each nest once a day for four days to present each model type at every nest.

It was hard work. The first day of experiments began discouragingly. After lugging the models through a cold drizzle a mile down the beach, all of the first twelve trials involved the younger gull model types. Every nest reacted differently. Some gulls seemed unconcerned, some attacked the decoys, a few attacked us instead. We began our first trials with adult models in terse silence, but to our amazement, almost all of the adult models were swiftly attacked by the breeding gulls. Already, our results supported Taylor’s hypothesis: the gulls were more aggressive toward the adult models than toward the immatures.

We conducted hundreds of trials over the next month, with promising results: adult models were attacked twice as often as young models. Our sample size is not quite statistically significant, so

we plan to perform another round of trials next summer, but they are encouraging. It seems young gulls really must develop social skills at colonies, and immature plumages pave the way for them to do so.

The same age-related variations in plumage that Taylor studies make gulls some of the most difficult-to-identify birds in the world. Gulls also have a tendency to hybridize, smudging the already blurry lines between species. But Andrew Birch is part of a small community of birders – the gull enthusiasts – with a special dose of dedication, verging on obsession, that drives them to brave landfills and pour over gatherings of gulls in search of rare species.

For Birch, it is the very challenge of identification, the “mental exercise” of “sorting through many birds and trying to find one different one” that makes gulls so exciting. Because so few birders undertake the challenge of gull-watching, much less is known about their basic demographics and movements than for other birds. This “frontier aspect” also draws Birch. Unlike other birds, he says, “it feels like there’s maybe some discoveries to be made… [Gull identification] is still very much in its infancy.”

I tried to take Birch’s enthusiasm to heart. The next time I visited Lighthouse Point, I paused with the clump of gulls. I considered all the subtle features necessary for gull identification – the shades of their coverts, the angles of their bills, the quality of their wingtips. I found no rarities that day, but I could understand the appeal of gull-watching. With gulls, each flock is a puzzle. The more you look, the more you learn, and the more you see.

But Birch’s primary reason for watching gulls is not to challenge himself: it is simply to enjoy observing them. Even when describing the time a Herring Gull stole his daughter’s ice cream cone, he seemed less annoyed than amused by the gull’s gumption: “It didn’t spill a drop!” He told me about their often-inexplicable behaviors. “They play with tennis balls, you see that a lot,” he said. “I’m anthropomorphizing, but there seems to be a lot of play. They remind me of my dog.”

I had noticed a similar

playfulness on Kent Island. On windy days, the gulls would lift up into the air and hover in place, apparently for no reason other than to enjoy being buffeted. It seemed clear that they were doing it for fun, but the mere idea of fun is a controversial one for animals like gulls.

Back at Yale, I hesitantly asked Taylor how he felt about the word anthropomorphism.

“All biologists agree that humans are animals,” he said after a pause. “Where they split is that some biologists think that believing a human is an animal means that we can denigrate humanity into a set of animalistic principles, like lifetime reproductive success, fitness, evolution by natural selection. Those people are anthropomorphizing, in my opinion – they’re making the shape of an animal exactly the same as the shape of a human. And they’re doing that by dragging human experience down to the level to which they attribute animal experience. All I’m doing is accepting the same premise, which is that humans are animals, and then saying, human animals do these wild things. Who am I to believe, a priori, that other animals don’t do interesting things?” It is a perspective not without risk in the world of biology. Six months ago I would have hesitated to even bring up anthropomorphism with another scientist. Among gull researchers, it seemed, a new kind of science – trashy science, if you will – was possible.

Even those who grant animals subjectivity don’t tend to go looking for it in gulls. A few high-profile conservation organizations actively engage in gull “culling” to protect other species, as Taylor and Hodge recently described in their paper awaiting review – including the National Audubon Society’s Seabird Institute. In the 1970s, the Seabird Institute, then known as Project Puffin, began a decades-long initiative to coax puffins to found new island colonies in the Gulf of Maine, where they previously did not breed. Maintaining those colonies requires killing predatory gulls to protect the vulnerable puffins. Though this initiative was framed as a “restoration” of historic puffin habitat, the little surviving evidence from those islands before

22

European colonialism suggests puffins had never nested there in high numbers. In fact, the evidence suggests all of the seabirds nesting in the Gulf of Maine today – including gulls – are likely new additions, brought about by the conversion of the historically forested islands to grassy fields by sheep farmers in the 1800s, as well as by the extinction of predatory sea mink.

After the sheep industry briefly increased their numbers, gulls were targeted by the millinery trade in the early 1900s, and their population plummeted. Thus, along with other species used for the hat trade, gulls became a key focus of early twentieth-century conservation movements, including the first local Audubon societies. Indeed, as Hodge pointed out, the National Audubon Society states on its website that it was founded in 1905 for “the protection of gulls, terns, egrets, herons, and other waterbirds.”

But gulls’ time as icons of conservation was short-lived. As conservation increased their numbers in the region again, fishermen complained that gulls competed for their fish; berry farmers in Maine said gulls ate their crops; beachgoers didn’t like their mess. In the 1940s, the federal government sponsored an initiative to reduce gull numbers in the north Atlantic. The effort involved killing gulls and destroying upwards of a million eggs by spraying them with oil. The goal, Hodge quoted from an archival document, was not to eliminate them but simply to “reduce their populations until they no longer posed a serious menace to man’s interest.” Today, that effort continues in practice if not in name and is why, ironically, a century after it was founded to protect them, the National Audubon Society is “one of the biggest killers of gulls in the United States,” Hodge says.

According to Hodge and Taylor, we kill gulls not because puffins are any more natural or even significantly more threatened than gulls – Herring Gulls have themselves declined steeply since at least the 1980s. We kill gulls, ultimately, because we like puffins more: because unlike puffins, gulls sometimes eat at landfills, sometimes steal our food, sometimes even poop on us. I can’t help but

feel that the traits that annoy us about gulls are the very traits that make them similar to us: their commonness, their boldness, their adaptability. Indeed, Hodge says, we hate gulls because we see them “as these trash birds, that benefit from all of the things that we are ashamed of.”

Taylor primarily studies gulls and manakins, both birds considered to be instinctual rather than socially intelligent. Their social behaviors are innate, meaning they can’t learn behaviors like songs from each other, as songbirds can. Traditionally, biologists only define “culture” in species – like songbirds or humans – that learn from each other; instinctual birds like gulls have none.

Hodge, though, believes that gulls do have culture. They have been “continually astonished” to observe how distinct individual gull colonies are. Some colonies are tolerant of human visitors, some aggressive, some particularly nervous. What would those inter-island differences be if not culture?

And Taylor, similar to Hodge, is generous in bestowing sociality to gulls, even while acknowledging the innateness of their behavior. While gulls might lack the kind of culture defined by evolutionary biologists, that definition of culture is not the one understood by “normal human beings.” Gulls, Taylor says, do have a culture – just like us, they have fear and joy, beauty and attraction, anger and confusion, conventions and idiosyncrasies. They are not born knowing everything they will ever know. They develop their sociality, they find mates, they discover how to raise chicks.

On reflection, the difference between gull culture and our own is that theirs is remarkably stable. For millions of years gull society has looked much the same. It reassembles itself with consistency, having landed on a system that works. Each year, the young gulls feel themselves drawn to the windswept beaches. They stumble into gull towns, full of adults who do not care to teach them a thing. Each year, gull society rediscovers itself.

I told Hodge, since leaving Kent Island, that I can’t help but seek out gulls wherever I go. They assured

me they felt the same, preferring to watch gulls over more traditionally charismatic birds. “You can watch [gulls] everywhere. And when you find the magical in the mundane, there’s just so much to see in the world… I think that, in some ways, the world is a more beautiful place if you love gulls.”

When I visited Lighthouse Point in October, the gulls ignored me. No longer breeding, they didn’t care if I approached; there were no trumpet calls, no kicks to my head, no swirling clouds of gull-fury. Whatever was going on within and between them was invisible to me – their winter culture, if it was a culture, was oblique. What were they thinking? What drew me to them, even as they loafed silently on a nondescript beach? What did they think of me?

One young Herring Gull, just a few months old, wandered away from the crowd. It stepped into a puddle of water at the edge of the neighboring parking lot and drank a few sips. Then, for no discernable reason, it started stomping up and down in place. Its feet made a small pattering sound in the water. Later, I learned that gulls stomp on the ground to hunt worms. Their taps mimic the vibrations caused by moles hunting for them underground, which draws worms to the surface in a misguided attempt to escape. Perhaps this young gull hadn’t yet realized that stomping on concrete wouldn’t win it any food.

But the noise did seem to summon the other gulls, who quickly crowded into the puddle. No one else joined in the stomping, but the little Herring Gull persisted, every so often erupting into another splashy burst. Elsewhere in the park, someone was playing cheery festival music. The gull could have been dancing along.

23

Illustrations by Cora Dow

Richard Prum’s Great Search

Harper Love

riCHar D prum got His first pair of glasses in the spring of fourth grade. Near-sightedness directs a person’s attention inward, he says, so the glasses were a “sudden revelation that brought me into the world.” Struck by the vibrant visual details of far-away things, Prum became, within six months, a devoted birdwatcher.

He cannot explain why he chose birds.

He credits his undying passion to an “amorphous nerdiness,” but by that logic he could have easily dedicated his life to trees or airplanes. “Birds,” he admits, “were sort of random.” And yet, 50 years into birding and

40 years into academic ornithology, Prum has never considered doing anything else. “It’s what I live for,” he tells me.

I met with Prum in his office on a rainy Friday afternoon. The office had the frantic energy of an artist’s studio, cluttered with tea boxes and pictures of birds. Prum spoke about his life with the composure and rhetorical ornamentation of a man who has been interviewed many times, and leaned forward in his chair when he spoke about something particularly interesting. I admittedly did not learn very much about birds themselves, but Prum showed me what it might be like to love them.

Prum keeps a collection of orange notebooks in the right hand drawer of his office desk. The notebooks chronicle the birds he has seen, what he noticed about them, and the places he went to find them.

The oldest notebook we look at is his “life list,” a numbered record of all the birds he has ever encountered. He thinks he started it in high school.

“And then I stopped,” Prum says, “In the middle of grad school. Why did I stop? There was just so much going on in life.”

The last number is 1,158.

“You’d be a top EBirder,” I offer, proud to showcase my knowledge of the popular birdlogging platform.

“Well, surprisingly not!”

Richard Prum is now close to having seen 5,000 species of birds in his life. He has abandoned the notebook, but he maintains a life-list on a database where he can alter the taxonomy at his leisure.

He writes more detailed observations in his birding and field journals, which read almost like diaries. Prum does not remember birds in isolation from their environment. A notebook from July ’85, for instance, focuses on manakins but also recounts the trains he took and contains drawings of the town.

24

“This is last March,” he says, flipping through some more pages. “I’m in Sepilok, Borneo.” Though he means that he was in Borneo, I wonder to myself if he feels, in some sense, transported back to his research trip.

Prum stars birds that he has seen for the first time: these are “lifers” and “have a certain kind of status.” He cannot always identify the species of the bird at first glance. For this reason, he describes birds with detail, to reference later.

“Large, tan below, tan and brown above. Long dusty brown tail,” reads one description.

“A little green fruit pigeon. Tree top male. Brown wings, orange breasts, and a gray head,” reads another.

“A lot of the time, I can look at these notebooks like, oh, I remember that bird!”

Prum tells me. “I can see that bird. I can see the rock it was sitting on. I can see the branch. And that goes back to the 70s.”

“Time travel,” I say.

“Yeah! That makes it worthwhile.”

A lot of birding is waiting. Birds do not just appear when you want to see them. Sometimes they hide. I read Justine E. Hausheer’s article on nature.org, “The Lessons of Epic Birding Failures,” and learn that it is possible to leave an intricately planned

birding trip having done very little more than sit, silently, staring at nothing. The author finds this frustrating. “This was my one chance to find the trogon,” she writes, “and the stupid bird wasn’t there.” I gather that the birdwatching life demands an unusual amount of mental stamina.