SECTION

SECTION C: SPORTS

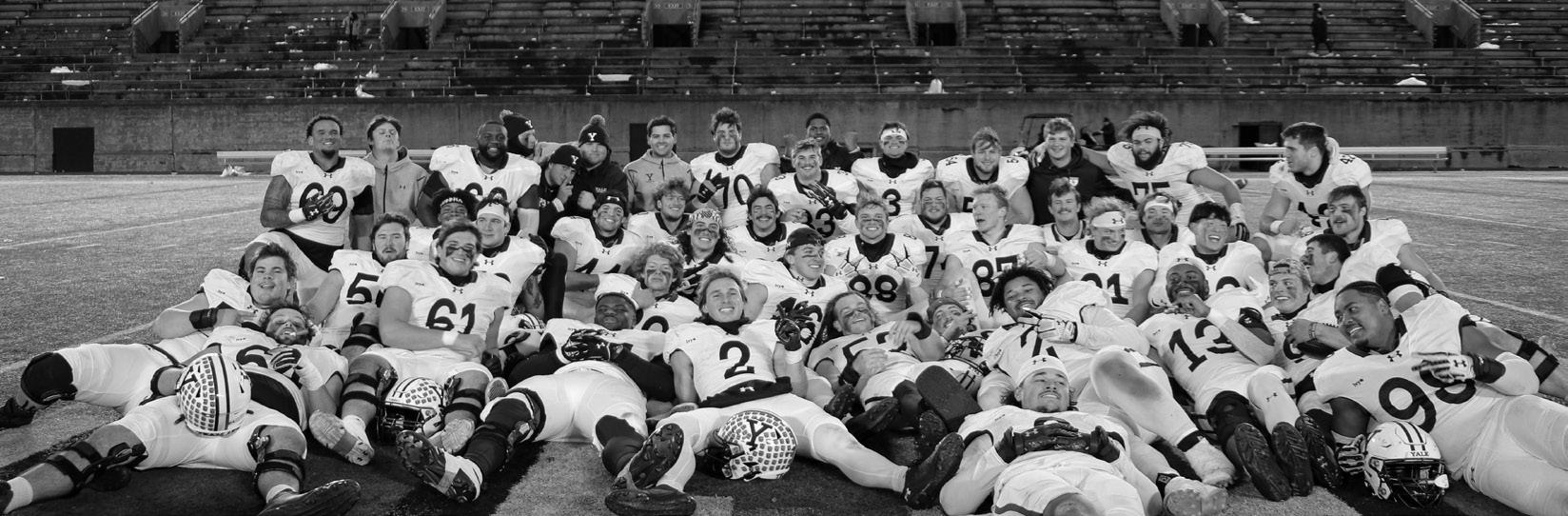

C2 — Transfer Portal Scramble? No Sweat for Yale Football

C3 — Recaps: Men’s Squash, Men’s Tennis and More

C4 — Recaps: Volleyball, Women’s Hockey and More

C5 — Recaps: Gymnastics, Women’s Lacrosse and More

All commencement ceremonies are scheduled to take place regardless of weather conditions. In the unlikely event of a cancellation due to severe weather, an official notice will be posted on the university’s commencement website.

In the case of inclement weather, Yale advises guests to prepare by bringing rain ponchos rather than umbrellas.

Any guest can watch the commencement ceremony live stream in the Humanities Quadrangle at 320 York Street, Rooms L01 and L02. All ceremonies will be stream on the Yale 2025 website: Yale2025.yale.edu .

Friday, May 16

11:00a.m — Middle Eastern & North African Graduation Celebration Brunch: Middle Eastern & North African Cultural Community Suite, 305 Crown Street

3:00p.m. — Asian Graduates

Ceremony: Omni New Haven Hotel Grand Ballroom. 155 Temple Street

6:00p.m. — Yale Symphony Orchestra Commencement Concert: Battell Chapel, 400 College Street

8:00p.m. — Yale Dramat

Commencement Musical: The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee: University Theatre, 222 York Street

Saturday, May 17

2:00p.m. — Service of Remembrance: Dwight Chapel, 67 High Street. This service is o ered for those who gather this weekend at Yale to celebrate a graduation, yet for whom the circle of celebration is incomplete. It is a chance to remember and include those who have died.

2:00p.m. — Yale Dramat Commencement Musical: The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee: University Theatre, 222 York Street

3:00p.m. — Yale College Senior Reception: Commons Dining Hall, 168 Grove Street. President McInnis will welcome Yale College seniors, their families, and their guests for a reception in Commons Dining Hall, Schwarzman Center.

4:00p.m. — Afro American Cultural Center Stoling Celebration: Woolsey Hall, 500 College Street

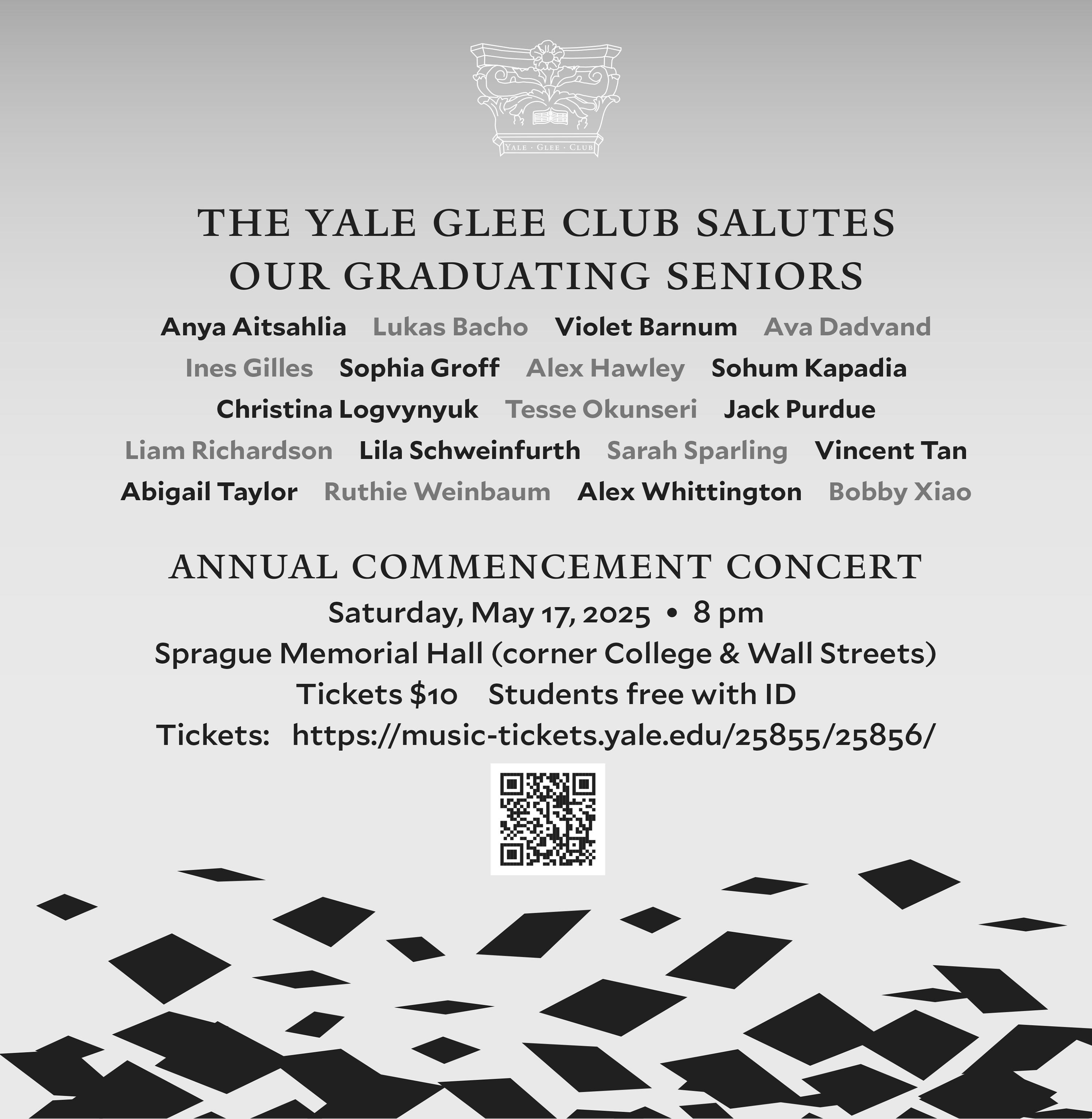

8:00p.m. — Yale Glee Club Commencement Concert: Sprague Hall, 470 College Street

8:00p.m. — Yale Dramat Commencement Musical: The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee: University Theatre, 222 York Street

Sunday, May 18

10:00a.m. — Baccalaureate Ceremony: Old Campus, 344 College Street. This one-hour ceremony features an address by President McInnis, as well as remarks by the Dean of Yale College.

10:30a.m. — University Church in Yale Commencement Worship: Marquand Chapel, 409 Prospect Street

2:00p.m. — Class Day: Old Campus, 344 College Street. Class Day, a Yale College tradition, includes the awarding of academic, artistic, and athletic prizes; the celebration of undergraduates; and an address by a notable speaker.

3:45p.m. — Receptions in the Residential Colleges. Receptions are held after Class Day in the residential colleges for Yale College seniors.

7:00p.m. — Yale Concert Band Twilight Concert: Old Campus, 344 College Street.

8:00p.m. — Yale Dramat Commencement Musical: The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee: University Theatre, 222 York Street

8:00p.m. — Whi enpoofs and Whim ‘n Rhythm Commencement Concert: Woolsey Hall, 500 College Street Monday, May 19, 2025

Monday, May 19

10:30a.m. — University Commencement: Old Campus, 344 College Street. All university degrees are formally conferred during the Commencement ceremony on Old Campus. During the ceremony, the dean of Yale College and deans of the Graduate and professional schools formally present their approved candidates to the president. The ceremony lasts approximately 1 hour 15 minutes. Tickets are required to enter Old Campus.

12:00p.m. — Residential College Diploma Ceremonies. Diploma ceremonies in each of the residential colleges take place immediately after university Commencement on Monday. These ceremonies last approximately two hours, and an optional Commencement luncheon follows in each college.

3:30p.m. — All School of Engineering Reception: Sterling Courtyard and Lower Becton Courtyard, 1 Prospect Street

4:30p.m. — Joint ROTC Commissioning Ceremony: Battell Chapel, 400 College Street

COVID Limits Recede; Mental Health Resources Swell

B9 — COVID Rules Receded; Mental Health Resources Swelled

B10 — Growing up Under President Trump, Again

SECTION D: WEEKEND

D2 — Class Day, Dr. Seuss and the Hats of Yale College

D3 — A Tribute to Yale Brunches

D4 What’s to Come: Commencement Horoscopes

D5 —

D6

C6 — Recaps: Heavyweight Crew, Sailing and More

C7 — Men’s Basketball’s Winningest Class

University lots will be open to the public from 5:00 p.m. on Friday, May 16 through 12:00 p.m. on Tuesday, May 20. A full list of lots can be found on Yale’s Commencement website.

To access Old Campus, guests should enter via Whitman Gate or Dwight Gate on High Street; or Cheney Ives Gate or Phelps Gate on College Street.

At the end of the commencement ceremony on Monday, May 19, shuttle service will be provided to transport guests from Phelps Gate on College Street to a number of residential colleges and schoolspecific celebrations. Each shuttle route will be marked by a distinct, color-coded feather flag to assist attendees in identifying the correct bus to their destination.

The shuttle lines and their corresponding stops are as follows:

Green Line: Divinity School

Yellow Line: School of the Environment

Orange Line: Medical School

Pink Line: School of Architecture, School of Art, David Ge !en School of Drama, Pierson College, Davenport College, Ezra Stiles College, Morse College, Timothy Dwight College and Silliman College

Purple Line: Pauli Murray College, Benjamin Franklin College, Jackson School of Global

The world’s most expensive concert is coming to an end and the audience doesn’t know what to do. Some have been packing their bags. Others have been taking photos of what they will miss. All have been waiting for the silence, the absolute stillness that follows the very last movement, for which no one feels ready. All are afraid because that silence means something: the show is over. It’s dark out. We’ve got to find the car.

Yale really has felt like a fouryear-long concert. I’ve watched students on the streets and chefs in the dining halls sing Lauryn Hill and George Frideric Handel. Walking to my dorm at night in the rain, I’ve heard violins in WLH, and while trying to fall asleep, I’ve heard from across the street the winds of the Newberry Organ. A hundred times I’ve stepped to the beat of the bells of Harkness Tower, and a hundred times I’ve witnessed spontaneous piano concertos in all the places pianos reside — classrooms, art galleries, butteries.

It’s no surprise, then, that at least twice a week, I’ve felt at Yale a familiar but fleeting sensation. It’s the same feeling I got when I first listened to Gustav Holst’s “Jupiter”

GUEST COLUMNIST

JUSTIN CROSBY

in fourth grade band, and the same feeling I got when the girl from Unorthojocks sang “Billie Jean” in SSS 114. I’ve heard people call it “chills.” It’s a feeling of limitlessness. It’s a happiness so overwhelming that one might explode from it. Before college, I thought only music could induce it, but I’ve felt it at Yale the times we got dizzy from laughter, during the game nights the courtyard could hear, in that cultural criticism class we all loved.

It’s the sense that life has become impossibly wonderful. And it’s the fear that it might never get this good again. During those moments, I’ve tried to press pause, to slow time, to hold onto that feeling forever, and of course that’s never worked. Until now, that’s been alright. The promise of any long concert is that the chills will come back. Slow movements might come — that science credit, that bad election, the first semester of junior year — but then they go. The momentum rebounds. Until it can’t anymore. The silence is coming and we all know what it means: there will be no more chills at this concert because this concert will be no more. For this reason, graduation has felt

ARIANE DE GENNARO

At the end of my first year, I wrote an opinion piece on a whim.

“In Defense of the Western Canon” was the culmination of my time in Directed Studies and my reflection on the value of studying Western history in a rapidly changing present. At the time, publishing an article was quite a bold thing for me to do. I had grown up shy, hesitant to share my thoughts even among the classmates I had known for years. Now, I was professing my opinion for all the world to see — or at least, the readership of the Yale Daily News. In publishing such a piece, I was consenting to any number of responses, from praise, to criticism, to outrage.

To my surprise, I received many positive responses from Yale students and alumni alike. One message led to the beginning of a relationship with one of my most important mentors at Yale. Writing for the News ended up being one of my most meaningful experiences in college. Through my column, I not only honed my writing, but I practiced the skill of expressing even my most unpopular opinions. Now, with my time at Yale coming to an end, I am all the more grateful for this lesson than nearly anything else. In an increasingly polarized world, it can feel harder than ever to deviate from the ideological mainstream. Freedom of speech has long been a hot-button issue on college campuses. For at least the past decade, the Right has heavily criticized academic institutions for fostering environments perceived as hostile to conservative views. More recently, the Left has invoked freedom of speech to defend campus protests opposing the war in Gaza. In the past year, responses to these protests, debates over institutional neutrality and the presidential administration’s actions against Yale’s peer institutions have all brought questions of free expression to the forefront of our shared discourse. There is broad agreement that free expression is essential to a liberal arts education, but there is little consensus on what it should look like. Regardless of what stances Yale takes, students will always be able to speak up, to agree or disagree with the institutions around them. We can help shape the intellectual climate of our campus ourselves, fostering diversity of thought from the ground up. Protest is one way to do so, but so is writing. The Yale Daily News o!ers undergraduates an opportunity typically reserved for professional journalists or public intellectuals. The chance to publish and be widely read should not be taken for granted, and I would urge all students to make use of this platform.

deathlike. I tried writing a “thank you for college” note to my parents and found myself thanking them for life. I’ve gone on very sad goodbye walks during which everything said could’ve come from an offbrand dirge. “And so it ends,” they muttered, “but at least it happened.”

As though watching the reel that flashes before one’s dying eyes, I’ve broadcast in my mind reruns of chills past: the night we sang karaoke and played “Vienna” on the keyboard while a strange fellow in the corner kept shouting “woooo,” the time we played manhunt in the yard of that house in Weston.

That’s done now. People say “life goes on,” and I know it does, but I’m not so easily assuaged. I’ve seen what getting older looks like. I don’t want to be chronically bored, tired, in pain. I don’t want to spend my nights watching television and listening to bad theme songs. I’m a little worried that life has peaked, that I’ll never find a better way to spend Halloween than huddled with everyone in Woolsey Hall, dressed in costume, listening to the Yale Symphony Orchestra.

Nevertheless a small piece of me knows that there will be more concerts, just different ones with different chills. A friend from my

But the spirit of opinion writing goes beyond publication. There are countless ways to embody the values of thoughtful, opinionated discourse. It begins with simply sharing your opinions, listening to those of others, and being willing to disagree. It means everything from contributing a hot take on Shakespeare in seminar to hearing out the person who, you discover, voted for the presidential candidate that you despised. It means listening to the person who supported last year’s encampments and the person who hated them. It means listening to them all the way through, before deciding whether their position is wrong, illogical, or morally reprehensible.

I’m not asking you to agree with everyone you meet or to stop becoming upset over beliefs you find indefensible. I’m asking you to talk, to write and to listen. The antidote to ideological conformity, on any side of the political spectrum, is to remain ever-critical, self-assured and radically empathetic in how we engage with ideas and each other. It is because opinion writing embodies all of these traits that I have so valued it. Over the years, I have touched on everything from the controversial, to the silly, to the sentimental. I have commented on October 7 and the presidential election, a cappella, my love of Christmas and reflections on entering my senior year.

Now, as I write my last piece as an undergrad, I feel certain it will not be my last ever — maybe not even my last in the News. Commencement is not the end — it is, literally and etymologically, a new beginning, the so-called start of our real adult lives. Any skills I have learned from writing for the News are ones that I take with me into my real adult career. With any luck, my column may even help me professionally — already, it has been a subject of discussion in various interviews during my time at Yale.

But all of that is in the future, over the horizon that is my graduation ceremony. For now, I am simply grateful that I had the opportunity to write and to be read. I encourage faculty, students and alums alike to take advantage of these pages, of this platform that remains available to the entire Yale community. What a privilege it is to be a part of this intellectual world, now and forever. These are the conversations that can fill lifetimes.

ARIANE DE GENNARO is a senior in Branford College. Her column “For Country, For Yale” provides “pragmatic and sometimes provocative perspectives on relevant issues in Yale and American life.” Contact her at ariane.degennaro@ yale.edu.

poetry class just went to the United Kingdom to meet his first nephew, and an alumna pen-pal of mine just went to DC to see the wedding of her former roommate’s son. So that small piece of me has bought kitchen supplies, has acquired a jar for making kombucha, has made the next bucket list — the Derby, the caves, the county fairs. But the other pieces of me still want to hold on, want an encore. During this past season of final exams, I overheard someone in the Silliman common room telling his friend, “Earlier, I played ‘Ode to Joy’ in my headphones, full volume, and I ran around a lecture hall in WLH.” He went on, “I stood on the desk and moved my arms like I was conducting.” All his friend asked was, “So you’ve gone crazy?” This is precisely what I don’t want to leave, all this brilliant craziness. All this beautiful noise.

After that conversation ended, and after the quiet resumed, a man came in and played the piano. For half an hour, he filled the room with a certain verve, with “Moonlight Sonata,” with chills. Then he stopped. Before his performance, the silence in the room was unnoticeable, but now that we were reminded of what life could

GUEST COLUMNIST ASHER ELLIS

feel like, the silence we were left with was absolutely imposing. It was near paralyzing. We stayed, and felt sad, and eventually got up and left.

The ending of the concert that is Yale will be more consequential. Life after graduation will probably feel, at least initially, quiet and inadequate and lonely. It’s bound to; our time here has set the bar for future concerts very high. We can only hope that that’s a good thing, hope that we are better o! for knowing just how impossibly wonderful life can get, hope that someday we will achieve elsewhere a similar frequency of chills.

But that’s regarding the long term. What are we to do in this impending silence? I read this in the news a while ago, and I’ve very slowly realized its moral lesson: at a concert in Boston some years back, at the end of Mozart’s “Masonic Funeral Music,” when the silence fell and the audience didn’t know what to do, a nonverbal boy said aloud what none could articulate, said aloud the only thing left to say: wow.

JUSTIN CROSBY is a senior in Silliman College studying Political Science. He can be reached at justin. crosby@yale.edu .

Every Thursday at 6:00 a.m., while most of campus is still asleep, I’m at Payne Whitney for physical training, known as PT. By 9:10, I’ve logged an hour-long workout and another 100 minutes of military training. Afterward, I stay in uniform all day — class to class, meeting to meeting. No skateboard. No jaywalking. No earbuds in. Most days, I’m just like any other student. But the moment the uniform goes on, I’m reminded — and so is everyone else — that I’m slightly di!erent. This is the double identity ROTC cadets at Yale carry. On one hand, I’m a normal undergrad. But I’m also contracted to become a military officer. Yale celebrates academic freedom and encourages exploration; military training demands discipline and adherence to standards. We rarely talk about this tension explicitly. Only once a semester, we briefly review guidelines about balancing academic freedom with the responsibilities of wearing the uniform. Navigating these two worlds can be complicated, but it’s precisely this tension — this constant negotiation — that makes my time at Yale uniquely valuable.

Unlike my classmates, I already know my employer after graduation. I don’t scramble for internships or chase job offers. I won’t choose my first city. Oddly, it feels liberating. I can spend my summers on work that genuinely interests me rather than padding my résumé. I can take risks others won’t. My career path is set in one sense, yet out of my control and uncertain in another.

I HAVE ACADEMIC FREEDOM, BUT I ALSO HAVE A COMMISSIONIN-WAITING. THE “VIEWS ARE MY OWN” DISCLAIMER ONLY GOES SO FAR.

Wearing the uniform also makes me a de facto ambassador. I’m not here to recruit. I don’t want to be a walking press release. But every comment I make — in class, online, or passing through Cross Campus — reflects on the Air Force, fairly or not. I have academic freedom, but I also have a commission-in-waiting. The

“views are my own” disclaimer only goes so far. You can see Yale’s military heritage just by walking around campus. On Old Campus, Nathan Hale, a member of the class of 1773 and arguably America’s first spy, stands immortalized above his famous words: “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.” Nearly 19,000 Yalies served in World War II, including President George H. W. Bush ’48. That legacy is a big part of why I applied: Yale is a place where service matters, where I can train as a cadet without living inside a service-academy bubble.

But Yale’s relationship with the military hasn’t always been easy. In 1969, amid protests during the Vietnam War, the faculty voted to strip ROTC courses of academic credit. By 1972, all ROTC programs were gone. It took four decades before ROTC returned in 2012, after “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” was repealed. Yale is now one of the few places where you can get a top-tier liberal arts education and train on campus to become an o cer.

Tensions still exist today. Last spring, during protests over the Gaza war on Beinecke Plaza, someone tore down the American flag while others in the crowd cheered. Out of caution, our cadre told us to switch into civilian clothes after our military training sessions for a few weeks. That felt like a low point, although some faculty who’ve been at Yale for decades reminded me that Yale’s relationship with the military has seen many ups and downs — and it was once much worse. In the early 1970s, cadets had to commission in private, and enlisted sta! were sometimes spat on while walking around campus. We’re nowhere near that now.

Today’s reality is surprisingly mundane. Most students are either supportive, indifferent, or just curious about my military path. “Why did you join the Air Force?” has become the default conversation starter — not asked in judgment but as a simple icebreaker. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, I’ve noticed a rise in student interest around national security and defense. Perhaps it’s selection bias in my friend group, but the shift feels real. More students approach me with questions, and several of my nonROTC friends have pivoted their careers towards defense tech or policy. I’m not naïve — for every student who wants to “support the mission,” there’s someone with a “Books Not Bombs” pin or someone who silently disapproves of ROTC’s

I’M BIASED, BUT I BELIEVE YALE IS THE BEST PLACE IN AMERICA TO EARN A COMMISSION.

presence at Yale. But that’s not just fine — it’s necessary. Studying alongside people who question the military’s purpose makes us better cadets and better humans.

Yale’s administration has been unambiguously supportive. When President McInnis took office, we continued our annual President’s Review tradition, marching for her just as we did for President Salovey. Last fall, the newly created Office of Veteran and Military A !airs hosted Yale’s first-ever Veterans Day reception, where they handed out Yale sweatshirts with the American flag, now regularly spotted around campus. They organize barbecues connecting ROTC cadets with veterans, art gallery tours, study breaks, mentorship chats and more. Sometimes the attention feels uncomfortable, like unearned recognition for service we haven’t yet provided. But the message is clear: we belong here.

I’m biased, but I believe Yale is the best place in America to earn a commission. The dual identity — immersed fully in Yale’s liberal arts environment and the structured world of military training — creates an experience impossible to replicate elsewhere. We cadets bring a fresh military perspective to campus, reminding fellow students that service members are just regular people pursuing a particular career path. And we, in turn, benefit enormously from studying alongside students from around the globe, including those who don’t understand or even disagree with our career choices. It’s in these exchanges that real growth happens. Whether you’re left or right, military-family or first-generation service, Yale will challenge you — and you’ll graduate with both a diploma and a gold bar. You’ll thank me later.

ASHER ELLIS is a senior in Ezra Stiles College studying Applied Mathematics. After Yale, Asher will be attending graduate school and serving as an Air Force officer. He can be reached at asher.ellis@aya.yale.edu .

GUEST COLUMNIST

PETER TRAN

GUEST COLUMNIST

TREVOR MACKAY

Rümeysa Öztürk, Mahmoud Khalil, Kilmar Abrego Garcia, Merwil Gutiérrez, Badar Suri Khan, and Mohsen Mahdawi: these names and faces of the many who have been illegally, unjustly and unceremoniously detained have been seared into my mind in recent months. Some were involved in pro-Palestine protests; others were just at the wrong place at the wrong time. As of this writing, only Rümeysa and Mohsen have been released from detention. What were their crimes that they should be snatched from the street and whisked away?

This is not the America that I was taught to love. This is certainly not the promised land my family fled to as refugees from Vietnam. Least of all, the neverending cruelties the current White House administration dishes out to ordinary working class Americans and our undocumented neighbors run counter to the Catholic faith I was raised in. My faith does not allow me to look away — nor does my Yale education.

“Justice, justice you shall pursue,” goes the famous line in Deuteronomy. The Lord Himself commands me to work in whatever way I can to advance goodness in this world. Who am I to dare refuse His call? This dearly cherished commandment forms the bedrock of the type of person I strive to become. As I prepare to graduate and take my leave from Yale, I can only hope that my privileged education can be used to help bring light into this often cold, unforgiving world.

The road ahead will be anything but easy. Catholic theologian Thomas Aquinas centuries ago wrote about the four idols of money, power, pleasure and fame that each take us further and further away from God. In today’s world, we have at our fingertips ample access to the many social media influencers, celebrities and politicians who flaunt these idols while most of us could only dream of such luxuries. Closer to home, many of our own are hell-bent on using Yale as a springboard to climb the social ladder in pursuit of any one of these idols.

It’s not that we should deny ourselves the simple pleasures money can buy. Moreover, not all who have power and fame wield them for selfish reasons. What I’m trying to say is that the blind and unabashed pursuit of these idols hampers any attempt at answering the fundamental question: “Am I not made for more?”

Several years ago, Father Ryan Lerner of St. Thomas More gave a

homily in which he invited us to contemplate what kind of legacy we want to leave behind. When our obituaries are written, would we want our loved ones to harp on about the wealth and prestige we had accumulated or would we want to be remembered by the lives we have touched? To the little ones yet to be born, I hope to be an ancestor that they can be proud of.

Whether you come from a faith tradition or want nothing to do with religion, I encourage the class of 2025 to find a moment of solitude and think hard about what your unique talents can o!er to the world. No one is obligated to reach the heights of Malala Yousafzai, Greta Thunberg or any other young visionary. Yet we all have something to pitch in. After all, when we all received those acceptance letters all those years ago, Yale made no mistake in choosing us. There was something in us that Yale recognized even when we didn’t see it. Imagine the combined e!ort of humanity in pursuing “Lux et Veritas” and what that could do for our topsyturvy world.

As I graduate, I still have doubts about whether I myself am up to this task. I am not musically gifted so that I may soothe the brokenhearted with my melodies. I certainly have no aptitude for anything STEM-related in which I could help engineer healthier cities or contribute to cutting-edge biomedical research. People say that my writing isn’t half that bad, so that’s all I have going for me. Yet, the funny thing about faith is trusting that the universe recognizes our sincerity and moves accordingly to have all of our actions fit like interlocking pieces in the grand scheme of the Creator.

So yes, even as our climate turns into our worst enemy and far-right governments globally collude to hasten the apocalypse, I doggedly hold onto revolutionary optimism. It’s an active commitment to the hope that a more just world is possible through solidarity and action within and between communities. Certainly, my Yale education has prepared me to take on this task. Let us lean on and have empathy for each other. Let us move mountains out of love for one another. “Lux et Veritas” — light and truth — may not seem so far o! after all.

PETER TRAN is a senior in Davenport College studying anthropology. He can be reached at peter.tran@yale.edu.

GUEST COLUMNIST

AYA OCHIAI

The name “Yale” was once synonymous with American statesmanship, intellectual rigor and cultural pride. Today, Yale’s reputation stands diminished in the eyes of the public. The erosion of public trust confronting our grand university arises from a drift toward intellectual abstractions and ideological utopianism divorced from the historically rooted traditions of the United States.

At Yale, academic departments elevate only those who challenge conventional truths and Western ideals. These departments have lost serious scholars of the classics, military history and the West, and chosen to replace them with scholars who reject the very validity of our great heritage. We must recommit our institution to engaging thoughtfully with our civilization’s founding beliefs and history, rather than recklessly deconstructing them and casting students into the wide maw of “progress,” expecting they will somehow emerge fulfilled and morally prepared to be engaged citizens.

A university and a society cannot live in self-hatred. Yale should remember that it exists not outside of time or a nation but within a civilizational context — one grounded in Judeo-Christian, classical and constitutional traditions. Yale must serve our civilization, not posture against it.

Intellectual inquiry and the pedagogy of the academy are, by nature, conservative. How can we even begin to learn without looking to the knowledge of the past? Our current refusal to acknowledge this truth has fostered serious errors in thinking in the academy. Edmund Burke captured the essence of this tragedy by lamenting the collapse of reverence for tradition and inherited wisdom in favor of “sophisters, economists, and calculators.” Abstract rationalism, divorced from historical continuity, has come to undermine the very foundations of our culture.

Restoring trust in Yale and recovering it as the great American institution that it should be demands a restoration of that dignity and reverence for the past that once defined its intellectual mission. In this way, intellectual conservatism not only teaches respect and gratitude for our civilizational inheritance, but sustains both society and scholarship into the future.Yale dooms itself and our society to obsolescence if it does not.

Yale worships so-called “rationalism” — embracing systems of thought prioritizing abstraction, critique, and

Recently, a friend asked me, “Would first-year you be proud of you now?” The question made me cry. Of course she would be proud of me. Nearly four years ago, I arrived in a city and a state I’d never been to before. I came from a place wildly different from Yale, but so did most of us. I wasn’t naive or inexperienced. There’s a lot I learned in my hometown that I couldn’t’ve at Yale and places like it. I graduated from an incredibly average American high school in rural-ish Washington, where football players and cheerleaders reigned, and most kids didn’t go to college, much less fancy schools like Yale. Back home, I learned to be a person outside of academic and career achievements, something I fear that many Yalies didn’t get to do before, or even during, college.

At Yale, I got to be a kid again. The first snow day, I had a snowball fight with friends and held a boy’s hand. I didn’t worry about how I would drive to work or take my mom to the hospital like I had during snow days the year before.

I still worried and cared for my family, but I couldn’t be there to take responsibility anymore. I cried a lot, missing home and feeling insecure. I embroidered a blanket that represented a tree by the observatory that I often cried under. The falling leaves made me miss the evergreens of the Pacific Northwest. I cried walking down Science Hill after my first physics exam. I struggled in school and still do.

I told stories about my ruralish hometown to mostly urban and suburban Yalies: lawn mower races at the Berry Dairy Days, working at McDonald’s, the grocery store’s trash compactor, Friday night football concessions, selfserve honor-system roadside corn stands. I shared about the annual Skagit Valley Tulip Festival and that my hometown grows the most tulips in the U.S. Every year at Yale, I’ve chosen a day in April, the first day that feels like spring, to be Tulip Day, a day on which I buy a bucketful of tulips from the grocery store and hand them out to whoever I see that

day, whether I know them or not. First year, I did Tulip Day because I missed home so damn much and I wanted to feel close to it here. The years since, I’ve done Tulip Day because I wanted to share a piece of my hometown, a piece of my heart, with friends and community at Yale. It’s become my favorite day of the year. Yale indulged me and allowed me four years to think about the world and my place in it. Classes, dining halls, and butteries gave me the tools, time, and space to think, talk, and learn. I learned about the ways and places where others grew up and reflected on my own background. My experiences at Yale expanded the limits of my world and contextualized the places I’d been before. I admit I can be self-centered and perceive the world through main character syndrome, in that I narrativize the seasons of my life, but I think Yale encourages it. So, what have I learned in college? All the cliche things — the world is bigger and more complicated than I ever knew —

deconstruction above all others. This rationalist drift is evident in the Yale Art History Department’s decision to eliminate its renowned European art history survey course because of the prominence of white, male artists. And in the English Department, students can graduate without ever reading Shakespeare or Milton. These are not isolated instances of ideology; they reflect a deeper commitment to abstract, progressive, rationalist systems that claim to know better than the moral and intellectual authority of hundreds of years of civilizational inheritance.

Today, Yale is rightfully held in suspicion and distrust for its shameful discarding of the past, as evidenced by Yale’s negative relationship with its own namesake. Elihu Yale was once honored as a foundational benefactor whose generosity enabled the existence of the college we hold dear. Today, he has been relegated to near-silence in official discourse. Despite never actually owning slaves, his portrait was subjected to controversy regarding even being displayed at the Yale Center for British Art. At the same time, his legacy has been quietly minimized in o cial narratives.

Rather than teach complexity and moral conflict honestly, Yale has chosen widespread erasure. This is not isolated; 2017 saw Yale renaming Calhoun College in an act of moral sanitization rather than educational engagement. Historical plaques have disappeared from view, and the living, active commemoration of its alumni that shaped early American civil life is now only found in the statues and plaques that do remain. For the rare commemorations of Yale and America’s past that do exist, they are heavily qualified with apologies and minimization. These acts reflect an institutional posture of disavowal and a disowning of the very history that has given Yale its identity and prominence. A renewed emphasis on practical knowledge, historical consciousness and meaningful application of tradition in Yale’s curriculum and campus life would reconnect the academy to the public and endear our campus to the nation it once served. The survival of Directed Studies is both remarkable and shocking — but it should not be the exception. As a former student in the program, I can attest to its intellectual rigor and formative power as one of the few serious institutional commitments to engaging with the Western canon.

and friends make most things better. I wish I didn’t know some of the things I know now. New Haven landlords taught me that in a big city, landlords can do nearly whatever they want. I learned that if you’re competent and helpful, you’ll be taken advantage of and that institutions that pretend to care about you, often don’t. I worked for the federal government and almost committed to working there my whole career. Now, I’m real glad I chose not to. Our stories don’t fit neatly into marketable TV series with nicely wrapped up narratives and happy ever afters. It’s all messy and fucked up and beautiful.

Today is commencement — most of life is ahead but it’s the close of a chapter. I know my next step — I’m going to be a mechanical engineer working on wind turbines for GE Vernova — and I’m okay with what comes after being a mystery. When I left for college, my dad made me a poster that includes a map and pictures of Skagit Valley, along with photos of my family around the edges. It’s hung above my desk everywhere I’ve lived. When I left the valley, I thought I’d be back as soon as I graduated. It wasn’t until late sophomore year that I realized that I could end up anywhere in the country, doing anything.

We’ve been blessed with opportunities few others are

But there is no guarantee of Directed Studies’ continuation. Every year, it must defend its existence against criticism that it is “too Eurocentric,” “too traditional” or not “diverse” enough. E !orts have been made to create a parallel or alternative curriculum decoupled from Western intellectual history. Programs like Directed Studies were once assumed to be central to a liberal education. Now, it feels like a contested outlier at Yale. My time at Yale let me personally experience this tension between intellectual tradition and institutional culture. In Directed Studies, I discussed and debated the great works of the West. Outside of the classroom, in my role as president of the William F. Buckley, Jr. Program and chairman of the Tory Party, I saw how the broader Yale community and environment treats tradition, patriotism and cultural inheritance as relics to be dismantled, rather than starting points for serious inquiry.

A coherent cultural foundation is crucial to the survival of all that Yale and America hold dear: liberty, justice, equality and republicanism. True intellectual diversity and academic freedom thrive within this tradition — not outside of it. Yale has inherited a moral and civilizational legacy forged in the blood, sweat and sacrifice of generations. We should not be ashamed of that history — nor of our nation’s. It is this disconnect that lies at the root of Yale’s public credibility crisis. Yale must stop treating its deepest traditions as liabilities and begin to once more champion them as strengths.

Yale once cultivated leadership devoted to the common good, as embodied beautifully in: “For God, for Country, and for Yale.” Today, Yale positions itself as a global institution training global citizens. It has distanced itself from national obligations and diluted its commitment to the cultural and moral framework that once grounded its public legitimacy. Yale has severed itself from the nation, despite the fact that this relationship once served Yale and America alike. Is it any wonder that our American system falters, just as our university loses its standing? We must reclaim and restore Yale as the American university.

TREVOR MACKAY is a senior in Timothy Dwight College studying history. He plans to work at McKinsey & Company in Washington after graduation. He can be reached at trevor.mackay@ aya.yale.edu.

afforded. Windows into new worlds have been unshuttered. And while we have potential for incredible academic and career futures, I hope we can also find grounding and meaning beyond shiny achievements and certain visions of success.

In her first speech to us TD firstyears, the iconic Dean Mahurin said, “Go to class and take the class with you.” I’ve taken that to mean, be true to yourself, but absorb and consider the ideas and people around you. I’ve learned to take the opportunities that feel honest and meaningful to me while finding joy in community, in relationships, and in giving out tulips on the first day that feels like spring.

Some part of me is still just a girl from Skagit Valley. This crazy, stressful, exciting place has changed me, but it’s also made me sure of who I’ve always been.

“Would first-year you be proud of you now?” Yes, she would. No matter where the first-year versions of ourselves imagined we might be now, I’d think they’d all be proud of us today.

AYA OCHIAI is a senior in Timothy Dwight College double majoring in Environmental Studies and Engineering Sciences (Mechanical). She plans to work for GE Vernova in South Carolina after graduation. She can be reached at aya.ochiai@yale.edu.

“The last thing the endoscopist asks me before I go under is my ethnicity. Jewish, I say. Already it sounds like a joke out of my father’s old orange jokebook.

Ah, the endoscopist says. Crohn’s is more prevalent in Ashkenazi Jews.

Whoa, I protest. I’m only half Ashkenazi; I’m Moroccan on my mom’s side.

NETANEL SCHWARTZ

tell them. I do not say that it is the first time in my life that I’ve yet to impress, that I’m lost.

My nephew is five days old when I hold him in my arms. He looks up at me with the blue eyes of my late father. At the synagogue my brother explains that his name — Shimshon, Samson in Hebrew — means “little sun.”

take away from this place that’s permanent, the voice says.

It makes no di!erence in the end, half-Moroccan is not protection enough. I tell the joke to my friend who is waiting for me outside the procedure room. I also tell him how angry I am at myself: I could have found out two years ago if I had just done the tests the doctor ordered. But I didn’t do the tests then, for the same reason I’ve avoided them this year: it’s March. When in my last months of school was I going to justify taking two days to, as my specialist calls it, “get scoped?”

I am responsible for you, little man, I whisper. You are worth it. Little sun. I think, if I am to be responsible for him I will have to be responsible for myself, too.

* The infusion center is on the fourth floor of Yale Health. My girlfriend insists she come with me for the first dose. We eat bagels first. It is the kind of kindness you can’t pay back. Any questions? The nurse asks. What if I need to go to the bathroom in the middle?

The joke, the real joke, is that it takes more than two days. The diagnosis comes after two weeks of visits to Yale Health, after which there are only more. Twice a week for a month I stand outside Linsly-Chittenden Hall and decide which class to skip, the 1:00 p.m. or the 2:30. They’re both English classes, I tell myself: skip the one you’ve done less of the reading for. Then one Wednesday I am at the door to LC, not having done the reading for either. That is when the problems start.

* I meet with my thesis advisor over tea every week of the semester. This week he can’t do tea and asks to meet in his o ce instead. I’ve barely touched my project, I say, I’ll have to turn in work I’m not proud of. He lets me talk. He is quiet but sharp and has always looked out for me. When I’ve exhausted myself he does not take over, does not try to change the facts. Don’t beat yourself up over the project, he says. There will be time to write the rest of it. You will. Then he points to the kettle on the shelf behind me, asks me to press the switch. So there is tea.

* It is almost May, two weeks before the end of the term. My brother and sister-in-law in London have a baby boy. I fly to meet him. How am I managing?

My family asks. Managing, I say. I have to find a place to stay for my second and third infusions over the summer, then a job with insurance that will cover the injections to follow indefinitely. Worse are the inquiries after the fellowships I didn’t win: the Cambridge ones? The poetry one? It’ll be good for me to try my hand at real life, I

“You see her?” The nurse asks my girlfriend, pointing to the IV pole where my medication hangs in an amber bag. “This is gonna be his second girl while he’s here. Everywhere he goes she goes too.”

We laugh. “She’s not supposed to know,” I whisper to the nurse. I think, my girlfriend has done more for me than two or three people could hope to do for a fourth.

* My papers are due. The Renaissance paper has not shaped up to the masterpiece I wanted. Neither will the Old English.

Only my paper on Robert Frost’s A Masque of Reason — his parody of the book of Job — comes easily.

Frost’s revision, I argue, is to shift Job’s complaint against God from theological to aesthetic grounds: it isn’t about life being fair, it’s about life exhibiting a form we can appreciate. If all the world’s a stage, Job asks, then why does the drama so rarely hang together?

I run into a student of mine in Sterling nave. I was his TA for Hebrew in the fall. He asks me how it feels to be graduating.

I regurgitate the wisdom that is proffered to us at the end of college: good things are not supposed to last forever. I shake his hand, ask him to keep in touch. And the voice of self-pity whispers to me the new word I carry around: chronic. It enters English by way of Latin and French, from the Greek “khronikos,” or “of time.” It should be a neutral word, just as “sonic” means “of sound” and “lyric” means “of the lyre.” But in English we reserve “chronic” for diseases that persist, that stick and poke and ache. Chronic, Crohn’s: it’s in the bones of those words, isn’t it? There’s at least one thing you’ll

Back in the reading room Frost’s Job goes on arguing with Frost’s God. As in the original, Frost’s God fails to explain himself. Finally Job concludes that whatever sense we can make out of life will not be beyond chaos but in chaos itself, in the shapes that chaos takes: “Yet I suppose what seems to us confusion / Is not confusion, but the form of forms, / The serpent’s tail stuck down the serpent’s throat, / Which is the symbol of eternity / And also of the way all things come round, / Or of how rays return upon themselves. . .” Not confusion but the form of forms. At the end of college the illusion of order that brought us here is over, no matter how secure the job or fellowship to follow. We perform ceremonies like commencement to mark the time whose passing we did not control, to give order to the confusion we feel at the base of our experience. Still, some things do ease. I finish the papers. I find a way to keep my specialist without Yale insurance. I close on a sublet for my treatments. In exchange I do not get to say goodbye to everyone I want to, or feel like a serious scholar, or find the job I want with the insurance I need. There isn’t time. There won’t be. Next week my mother and brother are coming from England, along with cousins, friends, professors. My father will look on from his own place; probably he will make an awkward and endearing toast. We will toast to my accomplishments, yes, but I will more readily celebrate the experiences I didn’t curate, the relationships I couldn’t have predicted. I will celebrate that I came to Yale in part to escape my Orthodox upbringing, only to find myself writing my last papers on Jews in English literature. I will celebrate the faculty who have supported me and the best friend I found here who picked me up from my colonoscopy and called me every day afterward. That I and my friends and my friends’ friends find ourselves surrounded this way, that we stumble and are caught — that is cause enough for celebration. It is not that aches alone can be of time, that good things must end. It is that more good things like these must come.

NETANEL SCHWARTZ is a senior in Timothy Dwight College studying English with a certificate in Hebrew. He can be reached at netanel.schwartz@yale.edu .

“When the Son of Man comes, will he find faith on earth?” [1]

The same might be asked by any prospective student about Yale College. The faith of generations past glows everywhere at this institution, originally founded in 1701 to train ministers for the Congregational Church. It is seen in the Commencement Weekend exercises, the residential college namesakes, the alma mater and coat of arms. This light reaches everywhere, everywhere except perhaps, the students. Where then, and in what state, might one find religious life on campus today?

In 1968, at the height of the enormous religious, cultural, and social upheavals tearing through the West and the United States in particular, Pope Benedict XVI, then known as Father Ratzinger, wrote his classic spiritual work, “Introduction to Christianity.”

In the book, Ratzinger explains that both the believer and unbeliever are mutually haunted by each other’s existence; the one’s inescapability from the other creates a persistent, mutual self-doubt in both men’s beliefs, preventing either from being too shut in himself and becoming the “avenue for communication” between the two.

How insightful he was.

On campus today, religion, for both the believer and unbeliever, finds its clearest expression in this uncomfortable tension.

The mutual inescapability of the two sides — their constant, unavoidable dialogue — defines the faith experience at Yale.

I am a practicing Catholic: I arrived at Yale in August 2021 as one and will leave as one four years later. When I first stepped on campus, I came with many preconceived notions about religious life here, almost all negative. I imagined the bulk of my fellow classmates as a great mass of atheistic temptation threatening my soul and my education, spiritual hazards to be avoided during my time of study. But as the months and years passed, my self-constructed fortress, the intentional shutting in of myself, could not, and did not hold in the face of the reality of the unbeliever.

As the token religious friend in many circles, my nonreligious friends and classmates increasingly would ask me questions about doctrine, rituals, and moral or political positions; they came to me when they wanted to know what Catholics thought about this or that topic. I began to have ever deeper conversations, and arguments, with them about the nature of faith and religion. They would challenge me directly.

“Why do you think you’re right and everyone else is wrong?”

“Why does religion matter if I’m already happy without it?” And I would respond with equal force.

“Why are you so sure that this is all that there is?” “What do you stand to lose if you’re wrong?”

Yet, just as my faith perhaps sparked some of their doubt, their doubt, too, led to greater reflection on my faith. From these encounters, I realized these people were not the obstacles or temptations I had so made them out to be, but rather individuals just like me, whose different backgrounds and experiences led them to their current

convictions. In fact, some of the reasons I gave for my belief were the very same reasons for their unbelief: the dogmatic claims, the counter-intuitive paradoxes, the hierarchical structure. My futile attempts to close o! this avenue for communication had ultimately revealed my own spiritual failings: my pride and my lack of charity towards others.

Also, much to my surprise, most of those whom I met at Yale were not hostile to religion, not the atheist caricatures celebrating the death of God that I had envisioned when I first arrived on campus. Rather, many showed genuine curiosity, even openness, toward exploring religious faith. Several friends who had never before been to church have asked to join me for Sunday mass, to check out for themselves the faith which I spoke and argued about so passionately. And in the local Catholic churches, I have witnessed the extraordinary growth of student conversions, reversions, baptisms, and confirmations over the last four years.

The search for that mysterious, unfamiliar Other — which calls out from beyond ourselves — is undeniably alive at Yale. While it is seen most explicitly in the vibrant religious communities and student groups, a quieter spirituality also stirs beneath the surface, an undercurrent of latent faith perhaps moved by the inescapable specter of the believer floating above it.

I cannot help but see the rhetoric on issues such as the environment, the popularity of courses like “The Good Life,” and the widespread embrace of meditation and mindfulness practices as signals of an unspoken yet profound desire for a deeper, more spiritual life. All of this gives me great hope that Father Ratzinger remains correct today: that the believer and unbeliever are simply unable to ignore each other for very long — they exist not as isolated entities, but as mutually dependent participants in an enriching and enduring faith conversation.

Saint Mary’s Church sits prominently on Hillhouse Avenue, its noon bells marking the rhythm of university life. Every day, students head to and from Science Hill, passing Saint Mary’s along the way. They exchange glances with people, like me, entering and leaving daily mass. It is in precisely interactions like this — brief moments of shared curiosity and acknowledgement — that one most clearly sees this religious dynamic, with all its complexities and contradictions, as it exists on campus today.

To the casual observer, Yale may appear as just another secular institution, where religion faded away generations ago, never to return. But beneath the surface, something more nuanced, more mysterious, is unfolding. So yes, when the Son of Man returns, He will indeed find faith at Yale; it just might not look quite like what anyone expects.

[1] see Luke 18:8

EVAN KWONG is a senior in Ezra Stiles College studying History. He can be reached at evan.kwong@yale.edu.

BY CHRIS TILLEN AND BAALA SHAKYA STAFF REPORTERS

Former New Zealand Prime Min-

ister Jacinda Ardern will take the stage on Old Campus to deliver the Yale College Class Day address to the graduating class of 2025.

Ardern, who served as New Zealand’s 40th prime minister from 2017 to 2023, led her country through a series of global and domestic challenges — namely, the Christchurch mosque shootings, a volcanic eruption and the COVID19 pandemic. In the University’s announcement, Yale College Dean Pericles Lewis cited Ardern as “someone who embodies empathy and excellence, character and commitment, innovation and inclusion.”

“Ms. Ardern speaks so candidly about how she has faced her own doubts and struggles, and I expect that her story will resonate deeply,” Lewis wrote to the News.

Class Day, which typically takes place on the Sunday before University commencement, will be held this year on May 18 — starting at 2 p.m. on Old Campus — and is open to the public. Seniors will begin the day with a baccalaureate service featuring remarks from University leaders before gathering for a celebratory brunch.

Previous Class Day speakers have included television journalist Fareed Zakaria ’86, actor Tom Hanks and then-U.S. Vice President Joseph Biden. The 2024 Class Day Address was delivered by United States Surgeon General Vivek Murthy MED ’03 SOM ’03.

“It’s deeply humbling to be this year’s Class Day speaker,” Ardern said in the announcement, “not only for the privilege of spending time with a new generation of leaders who will shape the future of their communities and countries — but because they will also change what leadership itself will look like.”

To many New Zealanders on campus, who praised her leadership back home, Ardern’s selection carries personal meaning.

Violette Perry ’25 told the News that as a Maori woman graduating from Yale, she felt incredibly proud and moved that Ardern was provided such an honor.

“She represents so much of what I love about Aotearoa (New Zealand) — the idea that even from a small nation, we can lead with global impact, integrity, and heart,” Perry wrote. “Her presence here reminds me that the values we carry from home — humility, community, and care — have a place on the world stage.”

During her time in o ce, Ardern became internationally known for her swift response to the 2019 Christchurch mosque attacks, which resulted in a nationwide ban on military-style semi-automatic firearms. She was also credited with helping New Zealand achieve one of the lowest COVID-19 death rates among developed nations through early lockdowns and public health coordination.

Ruby Barton ’26, also from New Zealand, noted how Ardern has “redefined what it means to be a powerful and e!ective leader.”

Echoing Barton, Stephen Liu ’27, a fellow Kiwi, emphasized how

Ardern turned moments of tragedy into opportunities for broader global impact.

Michael Yao ’27 recalled being in high school when the Christchurch mosque attacks happened.

“None of us thought anything like that could happen in New Zealand,” said Yao. “I tuned into Dame Jacinda’s address right after I came home, and her leadership helped the country pull closer together in the aftermath.”

Eva Hofmans ’25, who met Ardern in high school while receiving the Prime Minister’s Scholarship, recalled the former prime minister’s warmth and accessibility.

Hofmans added that she plans to recreate the photo she took with Ardern at the scholarship ceremony in 2019, now five years later, on Yale’s Old Campus.

“Despite being our Prime Minister, she remained personable and down to earth,” Hofmans said. “She broke barriers — leading a country as a young woman, having a child in

o ce — and showed that you don’t need to pause your life to lead.”

Perry said that she “resonates” with Ardern’s authenticity — a trait she believes is especially important for a speech addressed to Yalies who have experienced impostor syndrome and questioned whether they belong.

Te Maia Wiki ’28, on the other hand, cited critiques of Ardern’s ability to follow through on legislation, especially to address a growing housing crisis.

Wiki, however, noted that as an American, she believes “the bar for elected leaders at this level is low” and that as a Native American, “the bar for recognizing Indigenous communities by elected leaders at that level is even lower.”

Wiki added that she is appreciative of Ardern “paving the way” for other women leaders worldwide.

Other students echoed the significance of choosing a global leader amidst political unrest within the U.S.

Josh Ellis ’25, though excited to hear Ardern speak, speculated that her pick “won’t upset Yale’s spot in the fragile political climate of today,” as she is from outside the U.S. political sphere.

Ellis furthered that picking a more decisive speaker would play into the discourse surrounding whether Yale should be taking more of a public political stance, mirroring statements made by Princeton and Harvard.

Most recently, Harvard sued the Trump administration over cuts to federal funding. Princeton’s president, Christopher Eisgruber, has also vowed to fight the Trump administration’s attacks. Earlier, Yale President Maurie McInnis told the News she prefers working behind the scenes rather than making public statements.

Risha Chakraborty ’25 described this pick as a “strong and subtle” message from the institution. She noted that the pick for Ardern is in line with the support of safe expression and academic freedom.

“A lot of seniors were hoping we’d get a speaker who would be cognizant of the world we’re stepping into and give us genuine inspiration and advice,” Chakraborty wrote.

Ardern was previously selected as Harvard’s 2022 commencement speaker. In her speech, she warned of rising political polarization and called for a renewed commitment to democratic dialogue.

“One of the Māori kupu (words) for a leader or chief is rangatira — someone who weaves people together,” Perry wrote to the News. “Jacinda embodies this concept so beautifully. She leads not by commanding others, but by connecting them — by empowering people to move, act, and lead together. That spirit of collective leadership, of binding people through purpose and compassion, is something I believe will deeply inspire our graduating class.” Yale’s 2025 Class Day will be held on May 18.

Contact CHRIS TILLEN at chris.tillen@yale.edu and BAALA SHAKYA at baala.shakya@yale.edu.

BY ISABELLA SANCHEZ STAFF REPORTER

The Yale Dramatic Association’s 2025 commencement musical,

“The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee,” will be showing at the University Theatre this weekend from Friday through Sunday.

The musical features themes of growing up, facing failure and friendship — combining humor with nostalgia for childhood.

“It’s very fun, it’s very silly, it’s very heartwarming, and I love it dearly,” Emiliano Cáceres Manzano ’26, the director of the play, said.

The musical centers on an elementary school spelling bee, with six children competing for the championship. Between spelling words, each character shares sweet stories about their lives.

The show is produced entirely in the period between the end of the semester and commencement

weekend. Producer Rhayna Poulin ’25 called it “a musical in ten days.”

“Spelling Bee” will continue to evolve after opening night, since it involves improvisation and audience participation.

Each night, four different audience members are selected to be part of the show as competitors in the spelling bee. Audience members who are interested in volunteering will have the chance to fill out an application when they enter the theater. From these applications, the volunteers will be selected just before the play begins.

“The script is written in such a way that there are all of these flexible elements, but there’s also a very inherent structure to the show,” Cáceres Manzano said. “So really, rehearsing is a lot about figuring out how to maintain that balance and spontaneity and keeping the show moving.”

Since the audience spellers add an element of unpredictability to each show, the performers must be able to react quickly to anything an audience member could do or say — all while staying in character. Improvisation has been essential to rehearsals, where different members of the production team have stood in for the audience spellers.

Hannah Kurczeski ’26 — who plays Schwarzy, one of the children competing in the bee — described the improvisation as a “fun challenge.”

“It’s sort of like adopting a new set of instincts,” she said. Kurczeski said her character is the most well-read and politically conscious among the young spellers. At one point in the show, Kurczeski must improvise a political speech based on current events. Kurczeski said that her goal is to deliver a slightly di!erent speech every night.

To help the performers develop the right instincts, Manzano said he encouraged them to bring something from their own childhood memories. Whether it’s a certain mannerism or a piece of a costume, Manzano said he wants the actors to “give a gift from their younger selves to their characters.”

That childlike playfulness makes its way into the show’s comedy, which Kurczeski said brings an exciting “combination of humor and heart.” Kurczeski added that “you will not be able to leave the show without laughing your face o!.”

The inner child even shines through in the few adult characters in the play.

For example, the proctor of the spelling bee, Rona Lisa Peretti, played by Nneka Moweta ’27, won the spelling bee herself when she was a child.

“Even though she is one of the adults, she still has that inner child in her, and you see that in the competitiveness and the spiritedness that she has for the spelling bee,” Moweta told the News.

That sense of nostalgia permeates the play — perhaps an apt emotion for commencement weekend. Other themes, such as facing the unknown and defining oneself, also fit seniors’ transition out of college.

“I think the graduating seniors, much like the characters in the spelling bee, are facing pivotal moments in their lives, moments where they’re really defining themselves,” Cáceres Manzano said. Poulin, the producer of the musical and a graduating senior herself, has worked on every commencement musical since her first year.

She said that Yale students, like the children competing in the spelling bee, think a lot about material success.

“I think that a lot of your four years of college, now looking back on it, especially at Yale, is learning that there is more to life outside of the big trophy at the end of the day,” Poulin said. “Maybe the moments that you have with other people are probably what you’re going to remember more than getting a good grade on an exam.”

The University Theatre is located at 222 York St.

Contact ISABELLA SANCHEZ at isabella.sanchez@yale.edu.

BY CAMERON NYE STAFF REPORTER

For a fierce three weeks, Mara Vélez Meléndez’s “Notes on Killing Seven Oversight, Management and Economic Stability Board Members” has dazzled and educated audiences, tucking lessons about self-determination between exhilarating drag shows and bureaucratic assassinations.

As the final production of the Yale Repertory Theatre’s 2024-25 season, Meléndez’s work leaves theatergoers craving more of the show’s queer exuberance — underpinned by its Puerto Rican pulse to reflect the pent-up frustration of an entire country in one person.

The show follows Lolita, a young transgender woman and pseudo-vigilante who seeks justice for her beloved homeland of Puerto Rico. Donning a two-piece work suit with three stripes on the vest — in homage to the Puerto Rican nationalist Lolita Lebrón — Lolita infiltrates the Wall Street o ce of the Oversight, Management and Economic Stability Board for Puerto Rico to kill the seven board members responsible for managing the island’s debt. The debt exceeded $70 billion when the board was created in 2016 by the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management and Economic Stability Act, or PROMESA. Along the way, a flamboyant receptionist transforms the space into a drag-fueled stage where each board member is embodied and symbolically “assassinated.” As Lolita navigates this surreal journey, she is forced to reckon with identity, liberation and the cycles of colonial power.

The set evokes a cold, sterile corporate office: an elevated platform framed by stark white walls, furnished only with a minimalist desk and a staircase descending to a lower level. Below, a wall of glowing security monitors dominates the space — an eerie nod to the surveillance

and government scrutiny faced by generations of Puerto Rican activists under the watchful eye of agencies like the CIA. Lolita is played by the immensely talented Christine Carmela, whose performance is so heartfelt and refined that it is difficult to imagine anyone else in the role. From her somber opening monologue detailing her father’s firearm to an ABBA lip sync, Carmela’s acting caliber shines for the entire time she is on stage. Hysterical and emotional at times while dry and sarcastic at others, the

passionate character is embodied in Carmela’s commitment to the role.

Aside from magnetic emotional highs, Carmela’s talent lies in the way she can fill time. During the inevitable downtime required for numerous quick changes, Carmela was left on stage with the duty of keeping the audience engaged before the story could progress further. She never leaves a dull moment, whether by rummaging through drawers while a soulless bossa nova drones on, hitting a piña

colada-flavored vape or defiantly dismantling the PROMESA sign on the wall. Complementing Carmela is Samora la Perdida, the equally talented actor playing a receptionist-turned-drag queen whose elegance and charisma are only rivaled by drag legends like Tommie Ross, Alexis Mateo and Nina Flowers. Embodying seven different drag personas — from the materialistic mosaic of “Andrea Bags” to the authentic Puerto Rican loverboy Carlos — in just under two hours is no easy feat. La Perdida’s emotional depth and growth over the course of the show are poignant and unexpectedly tender, revealing the quiet strength beneath and the vulnerability behind the bravado and glamour. While the pageantry and spectacle are entertaining, the meat of la Perdida’s performance lies in their journey to explore the receptionist’s identity. By the end of the show, the receptionist has transformed from an ambiguous figure in an identity crisis to a confident nonbinary drag queen who takes the name Lolita after the woman who inspired her.

Between the opulent entrances and the back-andforth quips lies a genuine lesson for audiences who may be ignorant of the plight of the Puerto Rican people. Alongside the high-energy drag performances are important conversations regarding decolonization and identity: Would statehood equal

liberation? What about the complex role faith plays in one’s life?

Those lessons matter, especially in a political climate where trans people are routinely villainized. Such captivating performances explaining the challenges faced by Puerto Ricans left space for more. There should have been more development of the relationship between Lolita’s Puerto Rican and trans identities. While the receptionist’s character arc felt fleshed out, Lolita’s was less satisfying by comparison.

The true standouts of the production were la Perdida’s lightning-fast costume team. Pulling off such intricate and varied transformations in a matter of seconds was nothing short of extraordinary. Each look emerged flawless, a polished showcase made possible by behind-the-scenes artistry that made clear the team’s precision, creativity and sheer talent.

“Notes on Killing Seven Oversight, Management and Economic Stability Board Members” runs until May 17, offering audiences a few more chances to witness a bold, hilarious, and deeply moving journey. By spotlighting queer Puerto Rican voices, the show is a powerful statement on traditionally underrepresented populations — unapologetic in its politics, rich in its emotions and unforgettable in its theatricality.

The Yale Repertory Theatre is located at 1120 Chapel St. Contact CAMERON NYE at cameron.nye@yale.edu .

BY ADA PERLMAN STAFF REPORTER

With the recent death of Pope Francis, the papal conclave took 33 hours to select Cardinal Robert Prevost, who will be known as Pope Leo XIV, to lead the papacy.

Stephen McNulty ’25, who is involved with Catholic life at Yale, wrote to the News that it is “so strange” to have an American pope.

“To hear the pope of all people speaking perfect English in a Midwestern accent will take some real time to get used to. I’ll be able to understand Pope Leo without being filtered through translation — that is, with a type of direct understanding that English-speakers never had,” McNulty wrote to the News.

McNulty stands as one of many Yale community members shocked at the choice of an American pope. Others reflected on their hopes for the new pope’s stances on inclusivity in the church.

Carlos Eire, a history and religious studies professor at Yale, wrote to the News that he was further stunned by the speed at which Leo XIV was chosen.

“I also laughed out loud simultaneously, for the possibility of an American being elected had been preventively ruled out by all the so-called ‘experts,’” wrote Eire.

Eire suggested that one of the reasons Pope Leo was chosen is that he is not a “full-blown American.” Despite being born in Chicago and graduating from Villanova University, Pope Leo is a Peruvian citizen who spent over two decades in Peru as a missionary and as a bishop.

Eire also emphasized Pope Leo’s multilingual capabilities as a potential reason for his selection. Pope Leo is fluent in some of the most widely spoken languages in the Catholic world: Spanish, English and Italian.

Both Eire and McNulty discussed the various implications that the election of Pope Leo will have on the world political order.

While Pope Francis left behind a progressive political legacy, such as permitting priests to bless gay couples, Leo’s stance on political topics remains to be seen.

“I hope and pray that Francis’s efforts to build a more inclusive Church — with doors open to

everyone — will be picked up and developed concretely, not just with pastoral gestures of warmness, but with tangible action to build a Church that can better serve those who it has too often left on the margins,” McNulty who leads the LGBTQ ministry at St. Thomas More, Yale’s center for Catholic students, said.

Eire stated that Leo has a “clear record of displeasing folks” who lie on the left of the political spectrum regarding issues like abortion and samesex unions. He theorized that this might be due to “cognitive dissonance” that some American liberals have about Catholic consistency on respect for life.

Though Leo criticized Vance and Trump for their immigration policies before his selection as pope, Eire wrote that “it’s very difficult and risky to make any predictions” about how he will act politically during his papacy.

William Barber II, who is not Catholic but leads the Center for Public Theology and Public Policy at the Divinity School, echoed hopes for the Pope in a recent New York Times article. Barber emphasized the importance of

the Pope’s role in the world even beyond the Catholic community.

“We’re in a moment when the moral forces of the world and religious forces of the world have a deep responsibility to say it doesn’t have to be this way,” said Barber.

Beyond hopes for the Pope to be a moral voice in the world, McNulty emphasized his desire to be “challenged” by Pope Leo in the coming years.

“I hope to be challenged by Pope Leo to live in closer service to Christ alongside his Church. I hope he is challenged by the whole People of God, too -- after all, to worship a triune God is to worship the God of dialogue,” wrote McNulty.

Pope Leo XIV was elected on May 8.

Contact ADA PERLMAN at ada.perlman@yale.edu

BY ASHER BOISKIN AND ISOBEL MCCLURE STAFF REPORTERS

Four months into the Trump administration’s tenure, Yale remains one of two Ivy League universities that have not faced targeted cuts to their federal funding.

While the Trump administration has cited a range of justifications for cutting grants to other universities — such as unchecked antisemitism, failures to maintain campus order and a perceived lack of intellectual diversity — Yale has largely avoided confrontation. Although the University has not faced targeted attacks to its federal funding, the Department of Education opened an investigation into antisemitism at Yale on March 19 in response to a discrimination complaint filed in April 2024 by the Brandeis Center for Human Rights Under Law and the Anti-Defamation League.

In early March, the administration froze $400 million in funding to Columbia University after releasing a set of demands for institutional reforms that ask Columbia to enforce disciplinary policies, combat antisemitism and change its admissions standards. The same month, the administration froze $175 million in funds to the University of Pennsylvania over its policies regarding transgender people’s participation in sports. On April 14, it halted $2.2 billion in multiyear grants to Harvard University, citing its refusal to reform programs with alleged records of antisemitism, discontinue diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives and promote more “viewpoint” diversity in academic departments.

Meanwhile, Yale has drawn occasional scrutiny and rare praise from figures aligned with the Trump administration over its handling of pro-Palestinian protests. Simultaneously, University President Maurie McInnis has responded to criticism of higher education by ramping up the University’s lobbying e!orts in Washington and limiting her own public statements.

University response to student protest draws “cautious” praise

In response to an April 22 pro-Palestinian demonstration in which student protesters briefly set up eight tents on Beinecke Plaza in anticipation of a visit by a farright Israeli minister, the University ordered the protest to disperse and referred multiple student partici-

pants to the Executive Committee for disciplinary review. A University spokesperson told the News that the student participants are facing disciplinary action for “failing to comply” with Yale’s policies on use of outdoor spaces.

The following day, the University revoked the club registration status of Yalies4Palestine, a group that promoted the event on social media, citing the alleged violations of campus policy at the demonstration.

On April 24, the federal Task Force to Combat Antisemitism — which has been investigating universities for antisemitism and potential civil rights violations — released a statement expressing that its members felt “cautiously encouraged by Yale’s actions” in response to the April 22 protest.

In a video taken at the brief encampment that garnered millions of views on X, a Jewish student claimed that “Jewish students aren’t allowed to walk through Yale’s campus anymore!” Harmeet Dhillon — assistant attorney general for the civil rights division at the Justice Department — tweeted about the incident, writing that the department “is tracking the concerning activities at Yale, and is in touch with a!ected students.”

The House Education Committee was also quick to also comment on the demonstration. In one post on X, the committee wrote, “Schools like Yale need to follow the law and protect all students—including Jewish students.” In another, posted after Yalies4Palestine’s registration status was revoked, it stated, “Yalies4Palestine brazenly violated campus rules in an attempt to occupy space on Yale’s campus. Schools across the U.S. continue to permit this kind of out-of-control behavior with virtually no consequences to those who break the rules.”

Republican Reps. Elise Stefanik and Virginia Foxx, who formerly chaired the House Education Committee during the committee’s hearings on campus antisemitism last year, have both called to defund elite universities over pro-Palestinian campus protests. In late March, Stefanik credited herself for Yale Law School’s termination of Helyeh Doutaghi, a research scholar who has faced allegations that she was a part of a designated terrorist organization. Similarly, Republican Sen. Mike Lee described pro-Palestinian protesters as “woke fascists.” But while

Lee has repeatedly targeted Harvard — calling it “a mess,” declaring that “we shouldn’t be funding it” and, as recently as April 20, urging the government to not “give Harvard another dime” — he has made no such defunding calls for Yale.

Yale limits public statements, increases lobbying in Washington Amid threats to higher education from the Trump administration, McInnis told the News in January that she would prioritize working with legislators and limit her public statements on the current political climate. In October, she recommended that Yale leaders broadly refrain from issuing statements on matters of public importance.