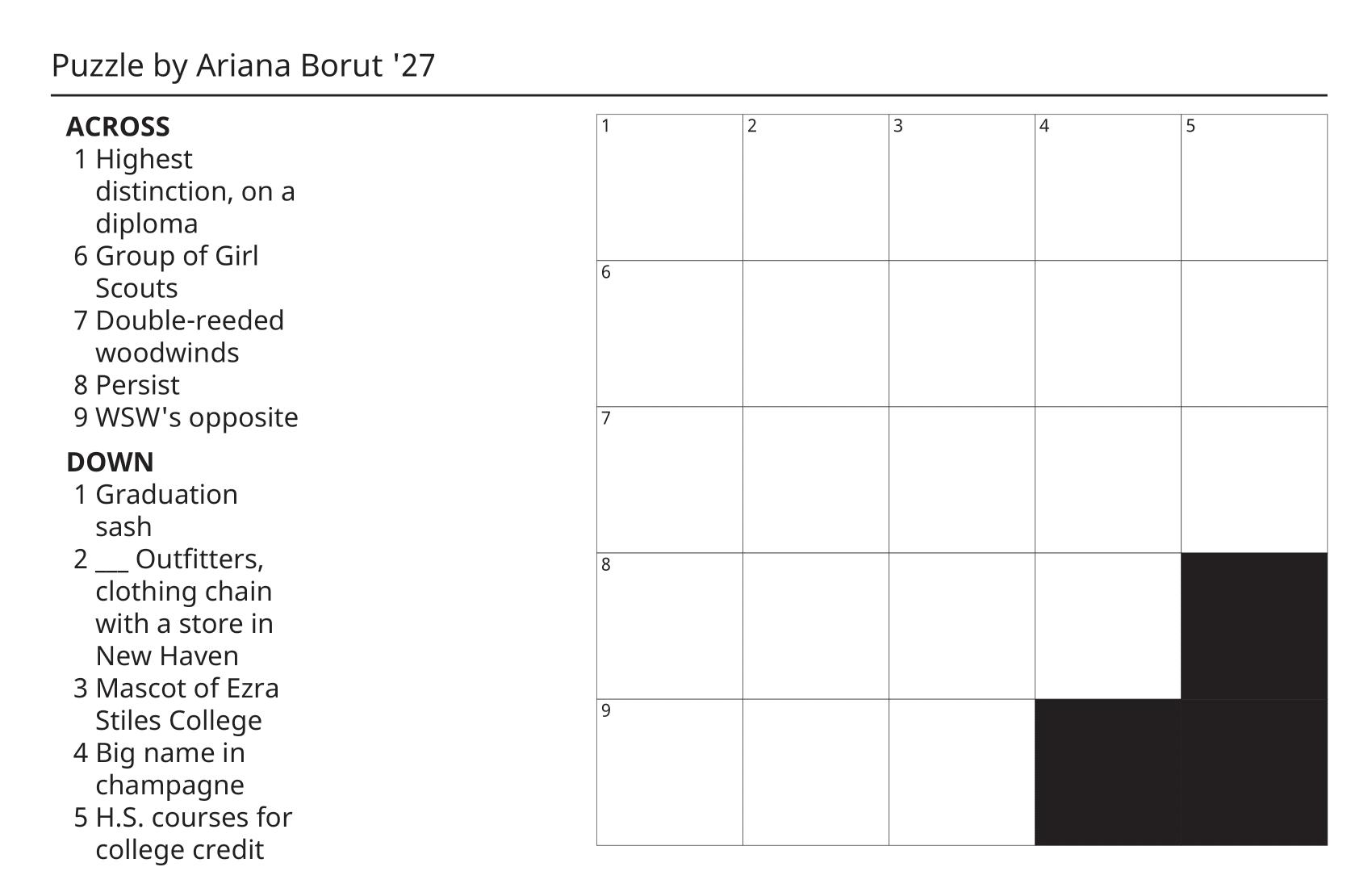

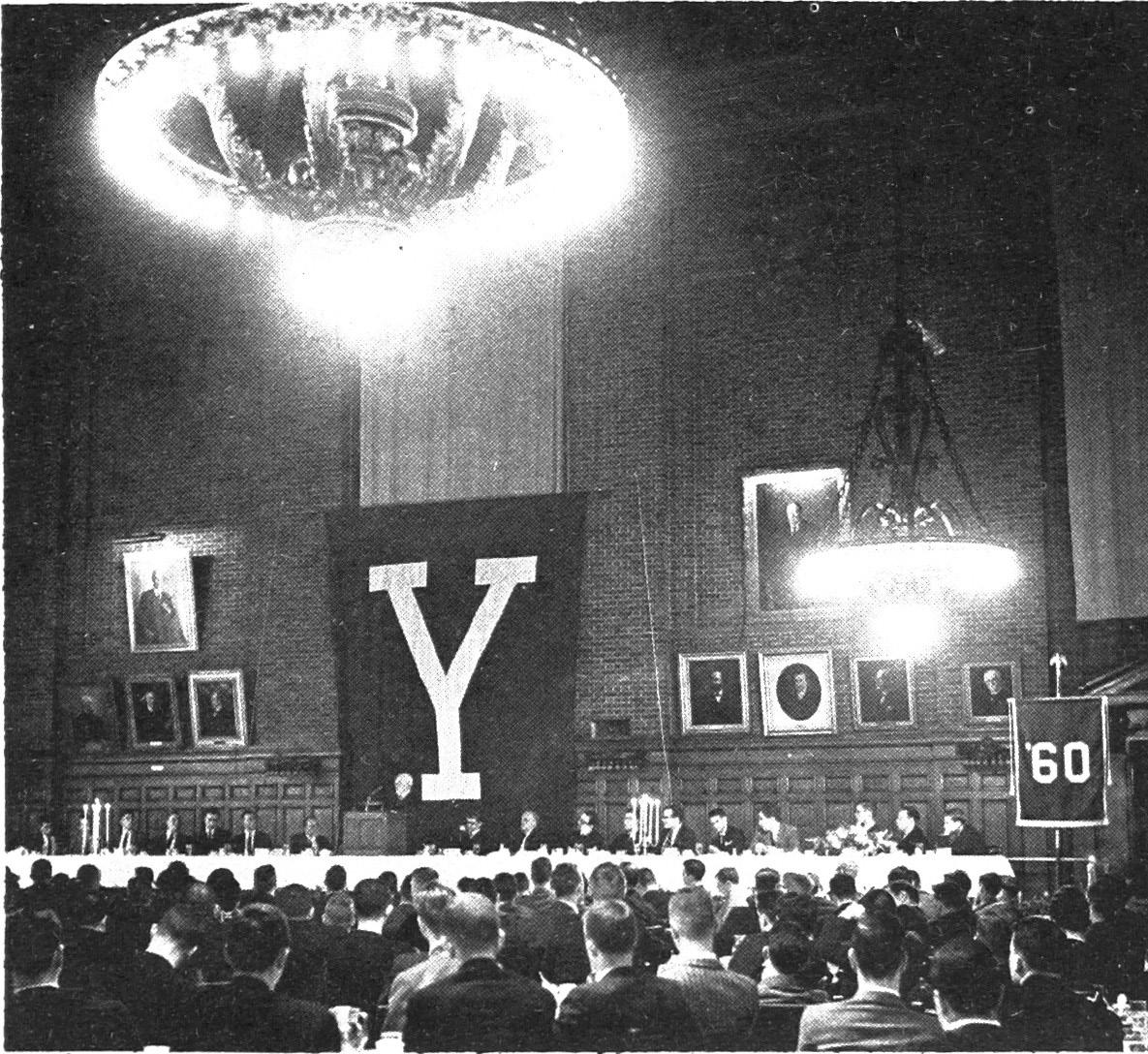

FEBRUARY 10, 1960

Gathering as a class for the first time in three years, the seniors witnessed the dedication of the class book and a talk on the liberal arts, at their class banquet in the University Dining Hall last night. Monroe E. Prince, 1960, editor of the class book, commented in his presentation speech, that the seniors were “pretty much a collection of dedicated men.”

The Reverend William S. Coffin Jr., University chaplain, delivered the invocation for the senior dinner. After the banquet, Price announced the dedication of the class book to Donald K. Walker, former associate director of admissions and freshman scholarships, and Richard C. Carroll, associate dean of Yale College.

Price introduced Mr. Walker as the man most responsible for the acceptance of the original class of 1,037 members, while Dean Carroll was presented as the man most responsible for the “913 who are

still with us.” Nothing was said concerning the responsibility for the other 124.

Sugar-Coated Pill

After the dedication, Brand Blanshard, Sterling professor of philosophy, spoke to the class, concerning that “sugar coating on the educational pill,” the liberal arts. Attempting to refute this “sugar coating” misconception of the liberal arts and approaching the true value inherent in them, Professor Blanshard discussed “Uses of the Useless Knowledge.”

Unlike the practical training in pre-business, pre-medicine, etc., with the relatively immediate material gain, the usefulness of a liberal arts education is more di ! cult to ascertain. It is not, he maintained for the purpose of evening conversion ability.

The chief arguments against a liberal education include its “dreariness and drudgery,” the resulting cost in joie de vivre, and the seeming futility. History, for

instance, has been characterized as “events that probably never happened, or if they did happen, were probably of small importance.”

An End in Itself

The usefulness of liberal knowledge, stated Professor Blanshard, lies in the dimension of the soul, in satisfying both directly and indirectly, “the elemental wants” of the spirit. Money “has no value in itself,” but only as a means to awakening the spirit.

“The pursuit of truth for its own sake is most admirable,” he maintained, and people pursue it because “they want to know the world and their relationship with it … the old and impregnable problems” of existence.

“Mass production is almost fatal to our individual spirits.” The cure for this, Professor Blanshard concluded, in the words of Matthew Arnold, is exposure to “the best that has been thought and saint in the world.”

FEBRUARY 1, 1965

The history of parietal regulations at Yale over the last 30 years presents a picture of continual change and often out-right confusion.

However, there has been a progressive trend toward liberalization, culminating in Saturday’s action by the Yale Corporation. Christopher W. Walker, 1966, did a good deal of research on the background of Yale’s parietal hours as part of a report which he submitted to George A. Schrader, chairman of the Council of Masters.

Walker points out in his report that the trend toward liberalization has been repeated in other areas of Yale life — automobile permission for upperclassmen, unlimited cut, refrigerators, telephones, vacation cuts and motorcycles. Even marriage follows the trend; for in 1927, married students were finally permitted to continue at Yale.

“All Live Animals”

Only the rules governing pets run counter to the pattern. In 1906, all dogs were forbidden, and in 1937, “all live animals” were forbidden.

Prior to 1931, the regulations regarding visiting hours for ladies in college dormitories were simple and direct — there were none. Only upon the written permission

of the Dean of Yale College would certain exceptions be made, and these were usually very rare. And after 6 p.m., there were no exceptions granted at all. Then, in 1938, the first big step was taken. Ladies were permitted in rooms from 12 noon to 6 p.m., seven days a week. The first Sunday afternoon cocktail party was born. But Sunday afternoon can often be an awkward time for informal get-togethers, and it was 16 years before the new traditional Saturday night dormitory festivities became legal. In 1954, upperclass hours were

extended to 12-7 p.m. Sunday through Friday, and 12-11 p.m. on Saturdays. Four years later, upperclassmen were again given an extension — the Friday night deadline was pushed up to 8:30, and the hours for Saturday were increased to 11 a.m.-12 midnight.

Alas, the poor freshmen had been neglected. But in 1959, the Old Campus overflowed with celebration — freshmen were permitted to entertain ladies 12-6 p.m. Sunday through Friday, and 12-8:30 p.m. on Saturday. And furthermore, taking into consideration that Saturday night par-

ties do not always end at 8:30, the freshmen were permitted to extend their Saturday night deadline to 10 p.m., provided that they register with the Campus Police at Phelps Gate. Then, in 1961, this bright picture of progressive liberalization met its first setback. After the unfortunate incident involving a teenage girl from New Haven, all week day (Sunday through Thursday) visiting hours were eliminated. However, with this curtailment of weekday visiting came also an extension of weekend privileges. Freshman hours were extended

to 12-7 p.m. on Friday and Sunday, and 12-11 p.m. on Saturdays. The College privileges were also increased — 11 a.m.-12 midnight, Friday and Saturday and 11 a.m.-7 p.m. on Sunday.

Thus, a dramatic step backward was countered by a significant step forward. One year later, in 1962, freshmen were given the same privileges as upperclassmen, and so it stood until Saturday’s announcement.

Yale’s parietal hours are more liberal than most other colleges. For instance, Harvard has weekday visiting 4-7 p.m. On Saturdays, freshmen may entertain ladies 12 noon-8 p.m. and upperclassmen have a midnight deadline. However, when a House is holding a social function on a big weekend, no girls are permitted in the dormitory rooms.

Some Extremes However, there are some extremes in liberalized parietals. Haverford, for instance, can entertain women guests “at any time” except a) between 2 a.m. and 7:30 a.m. Monday through Friday; b) between 3:30 a.m. and 7:30 a.m. Saturday and Sunday mornings. There is another restriction. A student may not entertain women guests in dormitory rooms or the adjacent halls between 7:30 a.m. and 9 a.m.

BY PAUL TAYLOR SEPTEMBER 15, 1969

The Yale University campus awoke from an annual summer siesta this weekend to discover that its 268 years of celibacy have come to an end.

Nearly 600 women, half of them freshmen, have poured onto the ancient campus this past week and brought with them the o!cial beginning of coeducation at Yale.

The Old Campus, which is never fully prepared for the hectic Fall arrival of 1,000 freshmen, seemed totally at a loss to cope with the coeds.

Nathan Hale, who for centuries has guarded the entrance to Connecticut Hall, apparently became self-conscious about his appearance and left.

He is reportedly tidying up for the women, and will be back in his accustomed spot shortly.

Least affected by the historic presence of women on campus, of course, are the women themselves. They are going about the di!cult business of arriving at a new campus and trying to fit into an alien

environment with the same apprehensions and self-doubts characteristic to all entering freshmen.

New Burden Vanderbilt Hall, oft-scarred in decades of presiding over freshman arrivals, must now shoulder the additional burden of entertaining upperclassmen. It houses 250 curiosities and will continue to do so until the natural course of time returns its tenants to the more fitting status of just-plain-women.

“You can’t believe all the boys around here,” one coed counselor said. “They hang around in the courtyard and when they spot an attractive girl, they help her in with her luggage or something.”

Similar scenes have been played out in the residential colleges all week. Most upperclass girls arrived several days before Tuesday registration, and there has been a healthy complement of upperclassmen on hand to ensure their first week on campus runs smoothly. The freshmen males, like freshman males anywhere, are talking about the freshman girls.

There were the usual snipes — “I wouldn’t have come to Yale if it weren’t for coeducation,” one said. “But the girls are atrocious!” And the usual laments of inadequacy — “lot of good coeducation will do me. How many of these girls’ll be going out with freshmen?”

Freshmen of both sexes report everyone they have met has been “very friendly.”

Test Each Other

Many of the newly arrived males could be seen romping on the Old Campus with footballs and frisbees yesterday, testing the athletic prowess of their roommates.

Others have been roving amidst the gothic architecture in groups of three and more, discovering the landmarks together.

“I think that’s a statue of Dwight Hall,” one was overheard saying, his finger pointed towards the statue of President Woolsey.

“Who was Dwight Hall?” his companion asked, dead earnest. Which is the way things will be for freshmen of both sexes for a while, anyway.

JAMES F. SMITH

JANUARY 13, 1975

Yale should guarantee the right to speak and should impose sanctions whenever disruption occurs, the Woodward Committee on Freedom of Expression recommended in its final report published last week.

To prevent repetition of the student disturbances which caused last spring’s cancellation of an appearance by Stanford physicist William Shockley, the committee called for a “program of reeducation” to strengthen the community’s appreciation of free speech principles.

“The first need is for effective and continuing publication of the University’s commitment to freedom of expression,” declared the committee.

Headed by the distinguished history professor C. Vann Woodward, the group was established last spring in the wake of the Shockley incident.

The committee’s report urged that all catalogues and handbooks include “explicit statements on freedom of expression and the right to dissent.”

The 13-member body, which includes undergraduates, faculty, and administration officials, outlined clearly-defined limits of protest in its report: “When a speaker has been invited to the campus by one group, other groups may seek to

dissuade the inviters from proceeding. But it is a punishable offense against the principles of the University for the objectors to coerce others physically or to threaten violence.”

The report emphasized that the nature of the speech does not, even if it is “deemed inflammatory or insulting, entitle any member of the audience to engage in disruption.”

The only exception noted by the committee is “if the speech advocates immediate and serious illegal action, such as burning down a library, and there is danger that the audience will proceed to follow such an exhortation.” In such a case the speech “may be stopped, and then only by an authorized University o!cial or law enforcement o!cer.”

The committee criticized Brewster’s handling of the Shockley invitation, especially in the president’s May 1974 Baccalaureate address, in which he “did not assert the primacy of free expression over competing values.”

“This committee’s account has revealed instances of faltering, uncertainty, and failure in the defense of principle on the part of various elements in the University community.”

“In specific instances,” the report said, “statements by the president and the Corporation have been interpreted as assigning equal if not higher value to law and order,

to town-gown relations, to proper motives, to the sensitivity of those who feel threatened or o ended, and to majority attitudes.”

The president and other o!cials may attempt to persuade a group not to invite a speaker, the committee advised, but they should not attempt to have the invitation rescinded after it has been made public, the report said.

“There is a risk that the public or private attempt will appear as an effort to suppress free speech, and also a risk that a public attempt will lend ‘legitimacy’ to obstructive action by those who take o ense at the speaker,” the report continued.

The committee suggested that the sponsoring group should be free to decide whether the meeting is open to the public, and that the sponsors may require college ID’s at the door.

The report asked that all events be given prior publicity so that any objections or special arrangements may be made “that will best promote order.”

The committee recommended firm action when a speech is disrupted. “The administration must undertake to identify disrupters, and it must make known its intention to do so beforehand.”

Discipline of disrupters, the committee said, should be handled by the University-Wide Tribunal, a board designed to decide cases

within the community.

One member of the committee dissented. Kenneth Barnes called the majority report’s “statement of principles too facile and simplistic, its historical section full of value judgements, and its recommendations vague and expedient.”

Barnes, a law student and graduate student in economics, objected to the committee’s willingness to rely on “moral suasion” to prevent “severe short-run costs in terms of other values which the University is interested in promoting.”

“Under certain circumstances,” Barnes wrote in his 15-page dissenting opinion, “free expression is outweighed by more pressing issues, including liberation of all oppressed people and equal opportunities for minority groups.”

“The report has been distributed to all faculty members and to the administration for consideration and advice,” according to Woodward. The faculty will discuss the report at a meeting next Thursday, and will vote on adoption of the committee’s proposals.

BY NICHOLAS LOBENTHAL AND BEN WATSON

JANUARY 31, 1980

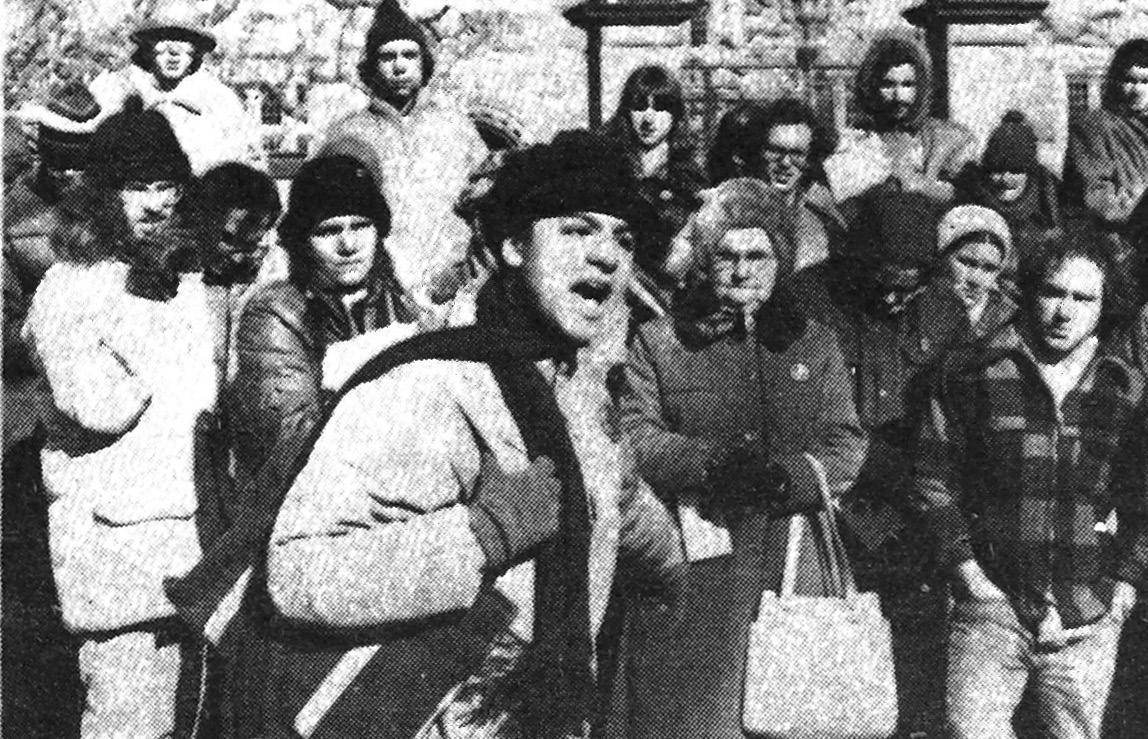

Anti-draft speeches and songs drew 200 students and professors to protest the draft yesterday afternoon at Cross Campus.

The U.S. must choose between the “discredited” practices of war or a “simpler way of life — longterm self-sacrifice,” University Chaplain John Vannorsdall said at the rally billed “Perspectives Against the Draft.”

Draft resistance is not unpatriotic, Vannorsdall said. “Our macho image of military strength was not part of the vision of America. Our future lies in new uses of strength.”

“What the Russians are doing in Afghanistan we can’t condone,” Professor of English Michael Ferber, who resisted the draft in 1968, said.

According to Ferber, the U.S. is overreacting to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

When the American ambassador was murdered in Kabul two years ago, the U.S. did not react, he said. And the U.S. has resisted invading Angola, Nicaragua, and Iran in recent crises, he said, drawing laughs from the crowd.

“What Carter is doing now,” Ferber said, “is what Kissinger has been trying to do for years: cure the U.S. of its allergy toward invasions.”

Commenting on the freezing “Afghanistan weather,” Ferber said that a prolonged war in the Persian Gulf is cheaper than converting this country from oil to solar, wind, and other sources of energy.

According to speaker Joan Cavanagh, a member of the New

Haven Anti-Nuclear Task Force, Carter’s call for registration is an excuse or not doing anything about pressing problems.

She said the 100,000 victims of the shot of Iran’s regime, the installation of new missiles in NATO countries, and the development of nuclear power plan in the US should be the U.S.’s top priorities.

“Now is the time to keep our country’s leaders cool!” a representative of the 65-year-old Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom said.

Mentioning U.S. intervention abroad in World Wars I and II, she said, “You are young and do not remember how many times we have been deceived.”

Sophomore Cliff Cunningham opened the demonstration with Phil Ochs tune, “I Ain’t a Marching Any More.”

Student demonstrators criticized Carter’s call for registration.

“I’m against the draft in any form because it always leads to people getting killed. Especially me,” Branford freshman Mike Bellacosa said.

“We cannot comply with laws and policies in the formulation of which we’ve had no say,” said another student.

Later yesterday an anti-draft group met in Vannorsdall’s o!ce to plan a nation-wide anti-draft e ort.

The group, “Campaign against the draft,” will sponsor “teach in” with formal University Chaplain William Sloane Co!n, who led antiwar movements at Yale, February 12 in Battell Chapel.

BY LISA PIROZZOLO

SEPTEMBER 27, 1984

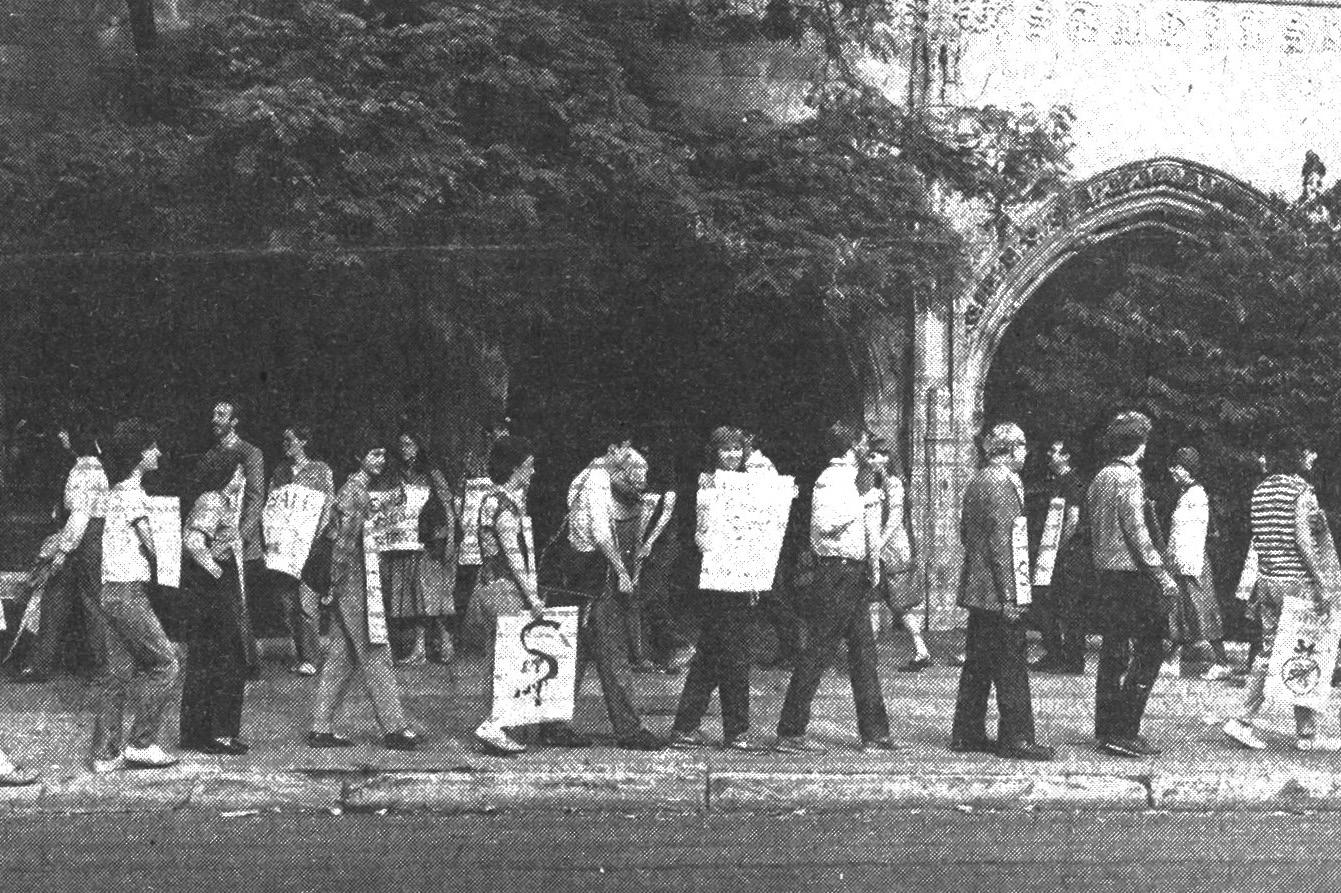

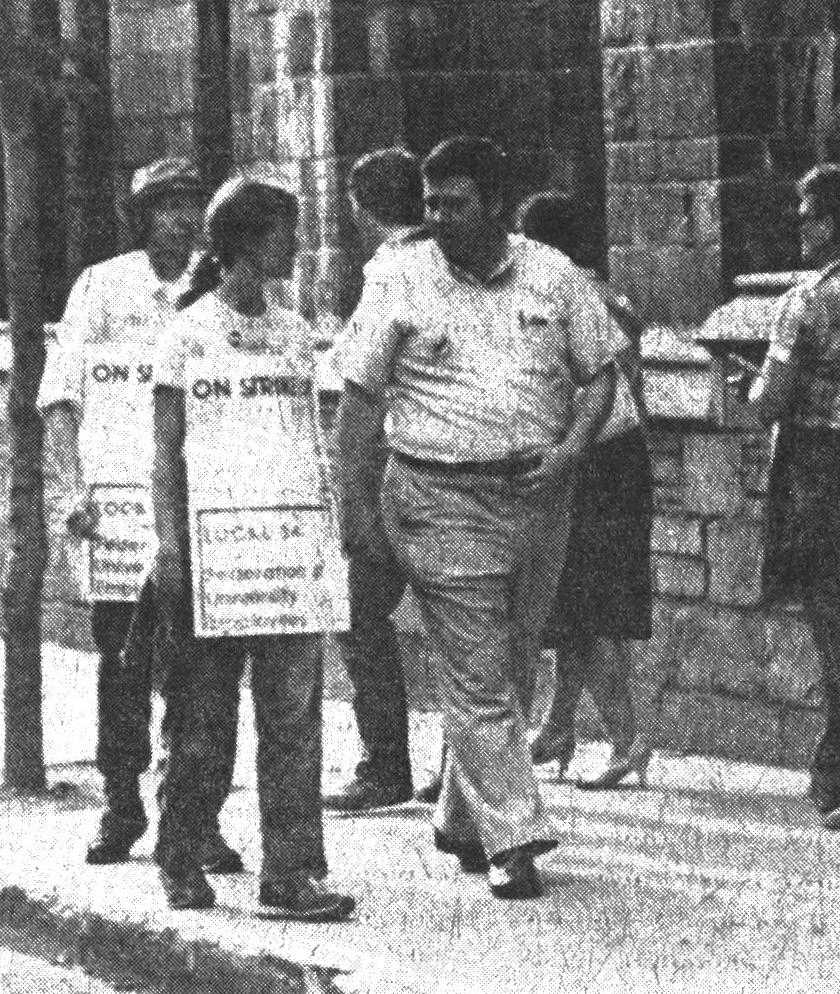

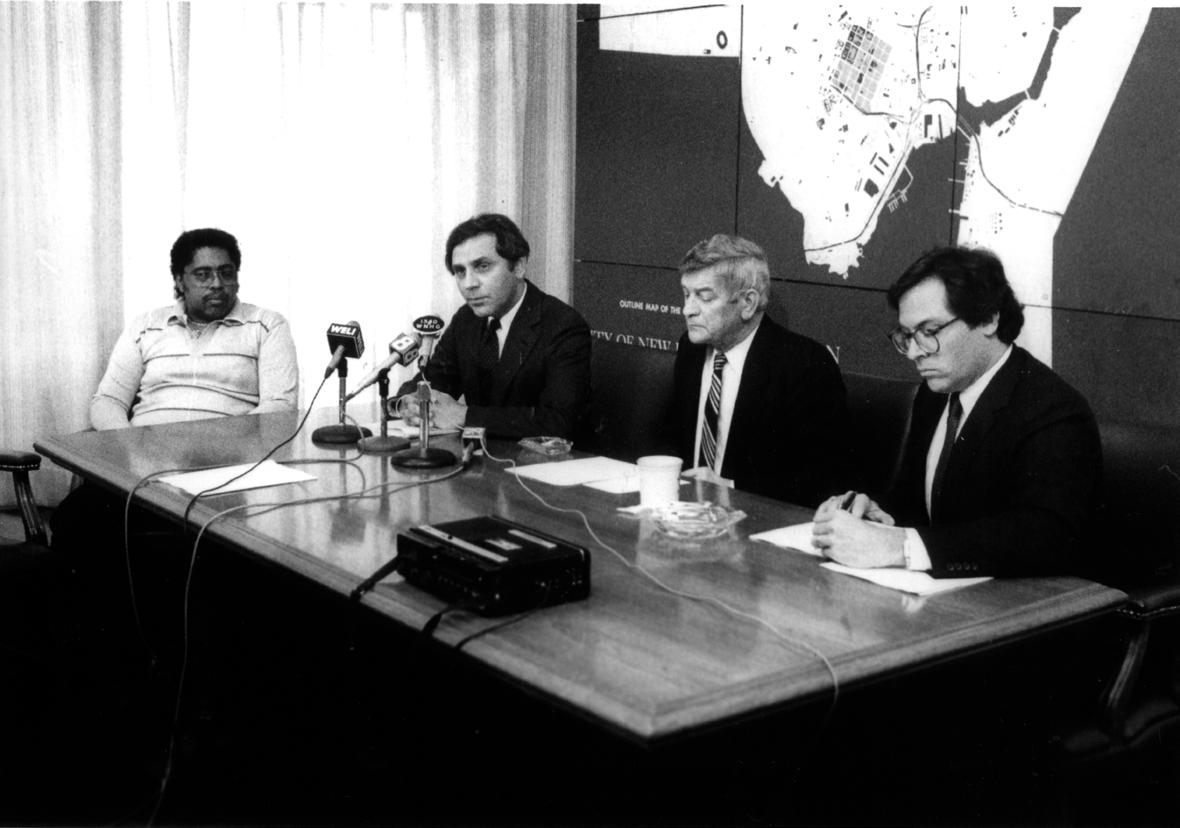

Negotiations between Local 34 Federation of University Employees and the administration are at a standstill, with each side accusing the other of breaking up the talks.

The administration presented Local 34 with a final contract

proposal at 5 p.m. Tuesday afternoon, only twelve hours before as many as 1,700 striking workers hit the streets.

Calling the administration nor Local 34 plans to initiate further bargaining.

“They said that no compromise proposal from us would produce any counterproposal at all. That being the case, there’s

nothing more to negotiate about,” Local 34 Chief Negotiator John Wilhelm said yesterday.

“We are not going to move toward the economic package demanded by the union,” Vice President of Administration Michael Finnerty told reporters yesterday.

“We have already stretched the University’s resources to the limit,” he said. “It’s a generous offer, and there are limits to how much money we can come up with,” Finnerty said.

But the administration will consider modifying the structure and language of its proposal, Finnerty said.

“We’re prepared to go into further talks if we have reason to believe they will be productive,” Finnerty said, adding that the administration would also resume negotiations at the request of private mediator Eva Robins.

But Wilhelm says Local 34 will talk only when the University administration says it will consider compromise. “We’ve said that if they’re willing to give and

take, we’re ready to meet around the clock,” he said.

Presently, Local 34 and the administration disagree on the economic consequences of the administration’s proposal.

Finnerty claims that under the proposal, the average Yale C&T now earning $13,473 would receive a $3,262 increase over the next three years. The entire proposal would cost Yale about $18 million over the next three years, he said.

But Local 34 has challenged the University;s claims, saying that the increase over 3 years would total less than 20 percent, and the entire package would cost the University less than $8 million. In what Wilhelm called an effort to clear up the discrepancy in figures, he requested a public debate with Yale President A. Bartlett Giamatti. But Giamatti refused, saying a public debate “exacerbates the divisions on this campus.”

“The reason the president refuses to debate me is that he’s lying, and he know he’s lying,” Wilhelm said.

BY NANCY E. FURMAN MARCH

2, 1990

Tom Hanks has wised up and decided to go back to school.

To Yale, in fact. The actor, whose success began with a Splash and then skyrocketed with Big, visited the campus yesterday as part of a crash course on Yale atmosphere and the Ivy mentality.

Hanks’ intellectually stimulating lunch revolved around interpretations of the novel’s protagonist with sundry Yale community members, according to lunch guest Joni Barnett, the director of the community and state relations.

Although Hanks offered no reaction to the quality of his Oxfordesque meal, a beaming member of the class of ’72 who served as first-hand research material proudly emerged from the entourage with an autographed copy of the Mory’s menu. Hanks’ tour continued down York Street to Davenport College. Once inside the college’s gate, the beleaguered star attempted to negotiate with his paparazzi: “If I stop here and let you take photographs, will you leave me alone?” he pleaded.

by the old-fashioned typewriters in the windows of the Whitlock Typewriter Shop. He then browsed, and only reluctantly he emerged without a purchase. But Hanks did purchase two large Yale corduroy baseball caps next door at The Game. Hanks’ penultimate stop at Sterling Memorial Library did not go unnoticed by the student body. After shaking hands with one starstruck student, Hanks admonished him to “get to work.” Hanks dealt with the wide-eyed stares by explaining, “I’m waddling like I have a duck on my head.”

After a peek inside Woodbridge Hall, Hanks had seen enough of Yale and declared himself ready to return to “the city.” His research completed, it will be up to Yale students to decide whether Hanks deserves and A.

Despite his theoretical earnestness to absorb the essence of Old Blue, Hanks was resentfully recognition shy. He emerged from lunch at Mory’s at close to 2:30 p.m.

He shunned the expected wantto-be preppy attire in favor of a heavy black coat, a woolly gray mu er, tortoise-shell sunglasses, and a grey felt fedora — hiding himself like an Artic film noir detective.

Hanks will play Yalie Sherman McCoy in the film version of Bonfire of the Vanities, the bestseller by Tom Wolfe Ph.D. ’57.

After a brief survey of junior John Musto’s room, Hanks was led by tour guide Lucy Clark ’90 to the Davenport dining hall and common room. On the way, he reiterated that the purpose of his visit was to research the Yale background which influenced the character he will portray.

But Hanks also played a Yale graduate in the comedy Volunteers.

Reminded of this fact, Hanks momentarily lit up in recognition. “Yeah, that guy went to Yale, too, but I didn’t come here for that movie,” he said.

With this newly found attention to detail, Hanks was immediately struck

BY JULIE HIRSCHFELD

APRIL 11, 1995

At about 10:00 Thursday morning two Yale police detectives wearing suits approached Lon “L.T.” Grammar ’95 in his Davenport College room saying they had a warrant for his arrest.

They arrested Grammar, who allegedly falsified his Yale application, on charges of first degree larceny after the University withdrew his admission.

Grammar, who was on financial aid, is accused of fraudulently obtaining $61,475 worth of grants and loans from the federal government and from Yale, the police report said.

He will enter a plea of “not guilty” at his 9:30 arraignment this morning but will apply for a continuance until April 20, said Norman Pattis, Grammar’s attorney.

Grammar’s financial aid files revealed he had received $25,000 in federal loans and grants and $35,875 in loans and grants from Yale during the past two years, police reports said.

If convicted, Grammar will face between one and 20 years in prison, Yale Police Sergeant Michael Patten said last night.

The arrest occurred after Grammar met with Yale College Dean Richard Brodhead and Davenport College Dean Janice Murray.

Brodhead said Grammar “is no longer a student at Yale,” but would not speak further about the specifics of the case.

After Grammar’s former roommate in California overheard him bragging about being admitted to Yale under false pretenses, detectives investigated Grammar’s record.

Police investigators discovered the senior, who transferred to Yale as a junior from Cuesta Community College in San Luis Obispo, Calif., had forged and altered many of the documents in his Yale admissions files.

According to police reports, Grammar’s admissions file contains two different copies of Grammar’s college transcript: the one he sent to Yale, which showed a 3.91 grade point average, and the one Cuesta Community College sent Yale just one month ago, show Grammar’s true 2.077 GPA.

Grammar’s file also contains several forged letters of recommendation and endorsements signed by nonexistent Cuesta Community College instructors, the report said.

Associate Director of Admissions Chris Murphy declined to comment on Grammar’s case.

Yale officials said the documents were well falsified and the fraud was di!cult to detect.

“I would say that they were of good quality,” Assistant Chief of Yale Police James Perrotti said last night. “They originally went through undetected, and there is reason to believe they would have been.”

Grammar, who was released from police custody on bond Fri-

day, could not be reached for comment last night.

As his Davenport roommate packed up all of Grammar’s possessions and shipped them to his native California, friends of Grammar said they were saddened, but not necessarily surprised to learn of his expulsion and arrest.

“He was a nice guy and a good friend, but he was kind of very shady, and we were all suspicious of him,” Mike Ciaschini ’95 said. “He was 26, there were a lot of years unaccounted for, and the stories we all heard about those years just didn’t match up.”

But others said Grammar, who was a member of the men’s rugby team and the Beta Theta Pi fraternity, was just like any other Yale student.

“We saw him every day for two years. We played cards with him. He was a good guy to hang out with and nothing fishy about him, really,” Andy Allen ’95 said. “I guess you just never know anybody.”

Pattis accused Yale administrators of being too severe with Grammar and “hypocritical” in their handling of the case.

“I think it was unduly harsh and ill-befitting a self-confident and secure liberal arts institution,” the attorney said. “He should have been permitted to graduate with the members of his class, even if those allegations are true.”

Pattis would not comment further on the allegations and said he

“had no knowledge” that his client illegally obtained financial aid. Although Grammar was just one month away from graduation, even sympathetic friends said he deserved to be apprehended.

“I think it’s a shame it had to happen, but if what I’ve heard is true, I think it’s great they caught him,” Nick Shields ’95 said. “Everyone’s got their skeletons, and I guess his have just come back to haunt him.”

BY JAY KANG

JANUARY 10, 2000

Yale, and much of the world, entered the Year 2000 not knowing what to expect from the mysterious Y2K bug. But the hype surrounding the YDK bug ended up as largely that — hype.

Yale began Y2K preparations in 1994, and it appears that the large amounts of manpower and money devoted to this program were well spent, with the Year 200 arriving without even a whimper.

The Year 2000 bug, known as Y2K, could have a ected computer sys-

tems because of complications with the date 2000. In the past, computer programmers used two digits instead of four to represent years. Many worried that this could have caused confusion between the years 1990 and 2000 in computer systems.

But these worries quickly disappeared as the new year arrived at Yale without any reported problems.

“There was nothing,” Yale President Richard Levin said. “It was a non-event.” The United States and Yale had the benefit of seeing the new year arrive in much of the world before it hit the eastern seaboard.

“Having watched the year change all over the world, first in Australia and New Zealand, we were increasingly confident that there would be no problems,” Daniel Updegrove, director of Information Technology Services, said.

Even with the growing reassurance that the millennium bug would not cause any problems, Yale still had more than 75 people on staff during the rollover.

100 Church Street was the site of a Command and Operation Center in charge of coordinating Y2K e orts, headed by University Secretary Lina Lorimer.

Starting at around 11 p.m. on Dec. 31, teams went to different locations around campus to check all mission critical systems such as the heat, electricity and water. By 1 a.m. on Jan. 1, teams had confirmed that there were no problems.

“The biggest issue was checking di erent facilities like heating and making sure they worked,” Updegrove said. “It was a pretty cold night.”

On the morning of Jan 1., additional teams came in to check critical systems that could wait until the morning such as payroll and

the banner computer system. By around noon, these teams also verified that everything was in working order.

University and ITS o!cials warn that there still might be a few problems specific to personal computers and advise taking precautions by using new anti-virus software and avoiding suspicious e-mail messages, for example. There was a small glitch in the medical school voice mail system on the morning of Jan. 1, but this problem was not Y2k related. This occurred because of an overloading of the system.

BY AMANDA RUGGERI NOVEMBER 29, 2004

The “Harvard Pep Squad” ran up and down the aisles of Harvard Stadium at The Game Nov. 20. They had megaphones in hand and their faces were painted as they encouraged the crowd to hold up the 1,800 red and white pieces of construction paper they had handed out. It would read “Go Harvard,” they said.

But the 20 “Pep Squad” members were actually Yale students. And when the Harvard students, faculty and alumni held up their pieces of paper — over and over again — they spelled out “We Suck” in giant block letters the whole stadium could read.

The brainchild of Pierson students Michael Kai ’05 and David Aulicino ’05, the “We Suck” prank was originally designed for the 2003 Harvard-Yale Game. But rather than hand out the paper in person to the crowd, they taped the paper to the stadium seats before the game began. The prank derailed when security guards, trying to clear the stadium out during a pre-game bomb scare, asked Kai, Aulicino and their cohorts to leave.

Rather than forget the prank, though, the pair became only more determined to have it succeed as seniors.

“We knew we only had one more chance at it,” Kai said. “To have to think about it for an entire year was really painful.”

But the elapsed time also gave the devious duo an opportunity to rethink logistics. Rather than tape the papers to the seats, they created a system to have the Harvard crowd pass out the 1,800 cards themselves. The “Harvard Pep Squad”

BY ESTHER ZUCKERMAN AND MARCUS SCHWARZ

OCTOBER 12, 2009

Since early September, Yale was abuzz with rumors of the return of bladderball — the notorious campus sport that was banned in 1982. Last Wednesday night, under the cover of darkness, representatives from a handful of residential colleges secretly convened in the center of Old Campus. Brought together by a mysterious e-mail, sent from an anonymous Gmail account, they hoped to learn the truth behind these rumors. Once members of various colleges had gathered, one student pulled out a notebook and began reading o details about the game.

On the ground

The game would begin at 4 p.m. on Old Campus, he said. The new bladderball, six feet in diameter, had been given as a gift from an alumnus to an unnamed campus organization. Though the gathered students asked the messenger questions, he seemed to know nothing more. Then the students went their separate ways, according to two students who were there.

On Thursday, the time and place began to trickle out to the Yale community. An e-mail sent to Davenport students about the game told Gnomes to be on Old Campus at 4 p.m. Fliers on tables in Saybrook also told students of the imminent game. On Friday, posters appeared in Stiles’ bathroom stalls. But many were skeptical: Would the game actually happen? Yale College Dean Mary Miller said she thought the game was a “hoax” and University President Richard Levin said attempts to reestablish bladderball had failed before.

The game begins

So even as a thousand people descended on Old Campus Saturday afternoon — students with painted faces and residential college t-shirts, bewildered or amused parents visiting for the weekend — no one was certain whether a ball would actually emerge.

Students chanted their college cheers and stretched their quads,

went to each row and handed out a pre-ordered stack of the red and white papers. In five minutes, Kai and Aulicino said, all the papers were passed out. It took a great deal of planning, however, including a road trip to Boston. Kai and Aulicino attended the Oct. 9 Harvard-Cornell football game in Cambridge, simply to scout out the stadium and count the number of rows. And then there were the disguises, which included “Harvard Pep Squad” T-shirts the Yale students designed themselves and red and white face paint. Cohort Dylan Davey ’05 said they even had Harvard student identification cards, created by a fellow Piersonite. Kai and Aulicino declined to say exactly how much money they spent on the prank, except that it was “too much.” Davey estimated it to be a few hundred dollars.

“If it didn’t work, it would have been pretty sad that we put so much e ort and money into it. But all that money was totally worth it,” Kai said.

Without the expenditures, the leaders said, Harvard suspicions may very well have won out, especially because many in the crowd had heard of a similar prank at the Harvard-Yale Game of 1982. MIT students tricked Harvard fans into holding up cards that spelled out “MIT.” Kai and Aulicino were unaware of that prank when they designed theirs, they said.

The first student to whom Aulicino handed a paper was suspicious, he said. First, he asked Aulicino, wearing a Harvard Pep Squad T-shirt, whether Harvard had a pep squad. He then asked if Aulicino was from MIT.

Security guards also approached “Harvard Pep Squad” members several times, they said, but between the Harvard student ID’s, T-shirts and red and white face paint, the guards were convinced.

“It was almost sad,” said Davey. “There were all these grandfather and grandmother types — and they all had big smiles, saying, ‘Oh you’re so cute, I’m so glad you’re doing this.’ I felt bad for about two minutes. Then I got over it.”

The Harvard side first held up the signs 4 minutes, 47 seconds before halftime. Then they held them up several more times, Aulicino and Kai said, as the “Harvard Pep Squad” ran up and down the aisles, cheering them on.

“We had more Harvard spirit than any Harvard student ever has,” Kai said.

The “We Suck” prank was not the only prank at the game. The senior class hired an airplane to fly over the stadium, trailing a sign that read “Too Many Can Tabs, Not Enough Kegs. Love, Yale ’05.”

Another group of students orchestrated a plan to steal the Harvard flag. This plan had its complexities as well, involving a decoy running around with a residential college flag to distract security guards and police o!cers.

Whether Harvard launched a prank is still unknown.

“See, we’re really above that sort of thing,” Lisa Goodrich, a Harvard sophomore, said jokingly. “Harvard doesn’t do pranks.”

The absence of pranks shows something about Harvard’s school spirit, Davey said. A “genuine difference” between her high

waiting for the appointed hour, 4 p.m., to see if all those mysterious e-mails and fliers heralding the return of bladderball were not one big joke. But right on time, a multi-colored six-foot ball bobbed through Phelps Gate. There was no mistaking: ban or no ban, bladderball was back.

Never making it into Old Campus, the ball bounced on a sea of outstretched arms out to College Street where students continued to move it towards Cross Campus. Soon the game had blocked tra!c on Elm Street, bloodied a few noses and brought out the police for about 40 minutes until the bladderball deflated.

A family in search of a parking space found one — in the middle of Elm Street. Metro Taxi 147, which was also detained, left the meter running, much to the chagrin of the passengers in the back seat.

And as students chased the ball, bouncing over cars, through

the middle of Elm Street, confused motorists honked their horns or, like New Haven resident Corrie Poland, took pictures on their cell phones.

“It’s not every day you run into the middle of a riot,” said Poland, who was on her way to go shopping.

Dangerous Fun And at 4:24 p.m., three police motorcycles and two officers blocked o Elm Street from York Street to College Street, pushing students and parents o the road.

“Get out of the street,” they shouted.

Indeed, though students said the game was exhilarating, some left with battle wounds.

Ricky Johnson ’12, who was wearing sandals, said he broke his pinky toe when someone stepped on his foot during the game. He added that he would surely play again — but with more durable footwear.

Max Budovitch ’13, who emerged with blood on his face, said he was “smacked” right after the game began. Alice Walton ’10 said her feet were trampled multiple times, but she enjoyed the game.

“It’s a break from taking ourselves too seriously,” she said.

Still, some students said the game sometimes got out of hand.

Josh Pan ’12 said he thought the game was fun until he saw an elderly man being shoved against a car.

“Usually everybody’s so under control,” Jack Li ’12 said after exiting a crowd of students fighting for a part of the ball. “But on this occasion, everyone just shows their wild side.”

Groups of parents stood on the sidewalk along College Street, some confused and disapproving, others with video cameras in hand.

One parent, Laurie Lieberman, said she thought the event seemed

school friends who go to Harvard and those who go to Yale, she said, is that people are just happier at Yale.

“I think that came out in this prank,” Davey said. The “Harvard Pep Squad” has launched a web site commemorating the prank at harvardsucks.org. The site, which Kai designed, went online at 2 a.m. Sunday morning. As of 10 p.m. Sunday, it had 5,560 hits. And a handful of 18-by-24inch posters of the Harvard side holding up “We Suck” have already been sold, Kai said.

Even so, Harvard students still aren’t very aware of the prank, Goodrich said. “I’ve gotten wind of it from a couple of e-mails,” she said. “But it’s not something that’s widely discussed right now.”

dangerous. But others, like Cliff Levine and Katrin Czinger, both with children in Timothy Dwight College, joined the mass of students chasing the ball.

“TD will ultimately win it,” Levine declared.

Just minutes after the police halted traffic, students tore the covering off the ball. It wasn’t long before the ball was popped and eventually ripped into shreds. But even after the ball had collapsed, some students continued fighting over the scraps, hoping to glean trophies for their respective colleges.

“This is the most amazing event ever,” Freddy Ketchum ’13 said from atop the Women’s Table as throngs of students tugged at the remnants of the ball below. “I have never been a part of something so glorious in my life.”

Although it was unclear which college “won,” most claimed victory in e-mails shortly after the event. Davenport, for one, said it posted 27,000 points.

Soon, the contest moved elsewhere on the Internet. After the game, the Wikipedia entry for “bladderball” was edited more than 160 times. The name of the winning college changed constantly until one editor locked the page at 5:51 p.m. because of “excessive vandalism.”

Stilesians managed to bring back the largest pieces of the ball which they brought to Ezra Stiles Master Stephen Pitti’s house, where parents had gathered for a Family Weekend reception. Sweaty students displayed the ball’s carcass on the banister.

Pitti said he hadn’t seen the article in the News on Friday and had not heard “any rumblings” of the bladderball game.

“Essentially, I was surprised and amazed,” he said. “I was really thrilled they were so happy.” Later that evening, Pitti sent an e-mail to the Stiles community offering “con-blad-ula-tions,” and to ignore rival claims of victory. Still, two blue pieces of the ball hung above the entry to the Pierson dining hall servery Saturday night — a call to arms for future generations of Yalies.

BY LARRY MILSTEIN APRIL 17, 2015

With cranes already towering above and workers bustling around the site, the University o!cially broke ground on the two new residential colleges yesterday.

“Two years from now, in 2017, this bustling construction site will have been transformed to a place of architectural splendor and a thriving hub of student activity,” University President Peter Salovey said. “And the year 2017 will be a particularly auspicious one for this particular moment in Yale history.”

On Thursday afternoon, roughly 150 alumni, administrators, faculty, students and members of the Yale Corporation filled into a tent outside of Ingalls Rink to celebrate the official start of construction on the two new colleges, a project set to be completed over the next two and a half years. The invite-only event included speeches from Yale College Dean Jonathan Holloway, former University President Richard Levin, project architect and Yale School of Architecture Dean Robert A.M. Stern, and former Senior Fellow of the Yale Corporation Edward Bass ’67 ARC ’72. The groundbreaking was an opportunity to acknowledge the donors who supported the project and to further outline the vision of this “new Yale,” Salovey said in his remarks. Still, some details, most notably the names of the two colleges, are yet to be disclosed.

“As you can tell from the heavy equipment and the amazing construction towers across the street, the ground for the project has already been broken,” Holloway said. “We are not actually at a groundbreaking … but I like to think of this moment instead as a celebration.”

Work on the site began in the fall. Though the original ground-

breaking was slated to occur in February, the event was moved to the spring to due to concerns of weather and convenience, Salovey told the News in February.

However, with temperatures in the 60s on Thursday, University leaders — hard-hats and shovels in hand — were able to walk around a portion of the construction site and pose for ceremonial photos with the mounds of dirt and concrete foundations in the background.

New Haven Mayor Toni Harp said the construction will make a “huge economic difference” in the city.

“I think we are very excited about the construction and what it means to the vibrancy of the city,” Harp told the News. “One of the things we are pleased with is the agreement we have with Yale … [that means] New Haven residents and contractors of color [and] small businesses can participate in this project.”

For major construction projects such as the two new residential colleges, city policy mandates that a certain percentage of construction jobs must go to city residents, minorities, women and small businesses from the city. For the new colleges, at least 125 New Haven residents will be employed on the construction site in some capacity, Nichole Jefferson, executive director of the Commission on Equal Opportunities, told the News in March. Levin described the groundbreaking as a “dream come true” following years of planning and delays following the 2008–09 financial crisis, which brought a halt to the project in 2008. He thanked major donors in attendance such as Len Baker ’64, Roland Betts ’68, Bass and most notably, Charles Johnson ’54, who donated $250 million to the proj -

ect, the largest gift in University history, in 2013.

Despite the a particularly difficult winter in New Haven, Senior Fellow Margaret Marshall LAW ’76 said she was proud of how much progress had been made on the site.

“When the people mentioned today were first talking about [the creation of two new colleges], it seemed like an enormous undertaking, which it is,” Marshall said. “My only regret is that I won’t be here for the 50th reunion of the first graduating class.”

At the end of his speech, Salovey announced that the Uni -

versity would be putting together a time capsule of mementos and memorabilia, the contents of which would be opened on the occasion of the 50th reunion of the first graduating class from the colleges. Some of the object to be placed in the large metal case — which will be located in a wall in an underground corridor connecting the two colleges — include Thursday’s issue of the News, the New Haven Register, the architects’ renderings of the colleges and photos from the groundbreaking. With all the pomp and circumstance of the event and

many of Yale’s most influential leaders all gathered under one tent, the anticipation of whether Salovey would use this opportunity to announce the names was palpable. However, he dismissed the idea that today would be that occasion.

“[The two colleges], like their 12 predecessors, will become unique communities with their own tradition and identities, with their own mascots with their own nicknames, with their own rivalries and with their own camaraderie,” Salovey said. “And sometime soon, their actual own names.”

BY VALERIE PAVILONIS AND MATT KRISTOFFERSEN

MARCH 10, 2020

Amid the rapid spread of COVID-19 — the disease caused by the coronavirus — the University announced on Tuesday evening that classes will be held online until at least April 5 and that students should remain home after spring recess.

“We will provide information sufficiently in advance of that date to allow for planning.”

The website added that while some students may not be able to leave the University by Sunday, Yale will “provide separate instructions for these students.”

Yale College Dean Marvin Chun wrote in a later email to Yale College students and their parents and guardians that students living on campus without “a suitable place to stay through April 5” should inform their respective residential college heads and deans, so that the College can continue to o er them support through dining and health services.

The announcement came in the wake of similar moves from Ivy peers — including Columbia University, Princeton University and, as of earlier on Tuesday, Harvard University and Cornell University. Posted to the website of the Office of Public Affairs and Communications, the notice said that classes will be held through Zoom, Canvas or other online platforms. The website also said that students who are currently on campus should “make every effort” to return home by March 15. “As we approach April 5, we will reassess the situation and communicate next steps,” the notice read.

“It matters greatly to me that if you are in the very di!cult position of not having a safe place to go to o campus, you know that we will take care of you,” Chun wrote. Graduate and professional students are also being encouraged to remain o -campus and will complete their most of their coursework digitally.

Following in the footsteps of some peer institutions, Yale’s announcement also said that all University-sponsored international travel is now prohibited, and that the University urges that all sponsored domestic travel be postponed.

Earlier on Tuesday, the Office of Undergraduate Admissions also emailed students announcing the cancellation of Bulldog Days, the three-day event during which admitted students explore the University. In the mass email, Dean of Undergraduate Admissions and

Financial Aid Jeremiah Quinlan wrote that his o!ce will be working on a “new experiment in online engagement this spring,” and that more updates will be forthcoming. On Sunday, University Provost Scott Strobel and Yale Health Director Paul Genecin encouraged coordinators to “postpone, cancel, or adjust,” all events expected to attract over 100 attendees, other than classes. According to a flyer posted to the front door of the admissions o!ce, all information sessions, campus tours and student forums are cancelled until April 15.

A Monday email sent to faculty members from the Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning provided links with detailed guides to online course software. According to a statement sent to the News by Patrick O’Brien-Sevilla, Communications Officer for the Poorvu Center, the Center is “rapidly developing” resources to help faculty members teach online. In an email to the News on Wednesday, O’Brien-Sevilla wrote that the Poorvu Center has logged 1,360 views on their academic continuity website since March 2.

Yale’s policy change comes amid a growing crisis, which has forced a national lockdown in Italy as well as an ongoing international stock plunge. Coronavirus — responsible for the respiratory disease, COVID-19 — can spread from person-to-person standing within about six feet of one another, according to the Center for Disease Control. The CDC believes the virus travels through droplets from an infected person’s coughs or sneezes, but the Center is still learning how it spreads. According to National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Anthony Fauci, the process for creating and

approving a coronavirus vaccine will take at least 12 to 18 months.

Earlier on Tuesday, Harvard President Lawrence Bacow wrote to students in an email that online instruction would begin on March 23. He added that students would also be encouraged not to return to campus following spring break, which begins on Saturday. Later on Tuesday, Harvard also asked students to vacate their dorms by March 15 — giving students five days to leave campus. On March 8, Columbia University president Lee Bollinger wrote that classes would be suspended for the following Monday and Tuesday, to give the university time to organize online classes for the remainder of the week. The measures came after a member of the Columbia community was exposed to COVID-19, though Bollinger stated in a press release that the individual had not yet been diagnosed with the disease.

Princeton University will move to virtual instruction on March 23, and the university instructed students to to practice “social distancing.” Cornell University followed suit and told students that instruction would go digital for the remainder of the semester.

Institutions on the West coast, including Stanford University and the University of Washington, made similar announcements regarding online classes as early as last week. Several other schools across the country — including the University of Connecticut — announced that all university-sponsored international travel would be cancelled.

As of Tuesday morning, the CDC has confirmed about 800 cases of COVID-19 in the United States. New York, Rhode Island and multiple other states have now declared states of emergency.

BY ISOBEL MCCLURE STAFF REPORTER

University President Maurie McInnis’ first year in o!ce has been marred by threats to Yale’s federal funding and faltering confidence in higher education. In response, she refrained from bold public statements, prompting dissatisfaction from some students.

During her inaugural year, McInnis established committees dedicated to examining the University’s relationship to the public sphere and prioritized lobbying efforts in Washington. Recently, she signed an American Association of Colleges and Universities statement denouncing the Trump administration’s interference in higher education. Still, she has remained silent on Harvard’s resistance to federal pressure, having previously implemented guidance that advised University leaders to refrain from publicly commenting on topical issues.

“I can understand the strong desire to hear how I might view the actions of other universities or respond in similar circumstances when we see what is happening at other institutions, including Columbia and Harvard,” McInnis wrote to the News on Thursday.

“But I feel strongly about staying true to my principles of being a respectful peer to my counterparts by not commenting on their decisions and trusting that each university is making the decisions that best serve their communities.”

The News asked eight undergraduates about McInnis’ approach to the Yale presidency thus far. The students — involved in various campus organizations — each spoke with the News in an individual capacity. They shared a range of opinions on the University’s response to student protests and approach to campus discourse.

Several expressed disappointment at the perceived absence of a clear articulation of McInnis’ vision for the University.

Institutional voice policy elicits skepticism from students

Just over a month after she was announced as Yale’s president, McInnis encouraged members of the University community to complete a webform that addressed a range of subjects, including the University’s public response to current events.

In September, she convened the Committee on Institutional Voice to determine whether Yale and its representatives should comment on “matters of public significance.” The group hosted “listening sessions” to solicit the opinions of community members.

McInnis told the News this month that institutional voice was a central concern in responses to the webform and her conversations with community members, which prompted her to form the committee.

The committee released its report, which advised that University leaders should refrain from taking positions on “matters of public, social, or political significance,” on Oct. 27, nine days before the 2024 U.S. presidential election. In a move that drew both support and criticism, McInnis adopted the committee’s recommendations in full.

During the fall semester, students appeared divided on the

decision, with some asserting that the recommendations were too ambiguous.

“It shouldn’t be some sort of blanket silence that applies universally to any sort of political issue,” Evan Lu ’27 told the News this past week. Lu added that he believes the University has a “responsibility” to make public remarks on matters that a ect Yale directly, including issues that may impact “academic freedom and the value of higher education.” Lu acknowledged that it is “tricky” to decide when the University should comment publicly.

The report advised that statements on behalf of the University are appropriate when “the university’s core mission, values, functions, or interests” are directly implicated. It acknowledged that expressing empathy on subjects of “transcendent importance to the community” may similarly be acceptable.

McInnis cited these remarks when announcing that she would accept the committee’s recommendations and emphasized that the report’s guidelines do not apply to individual students nor faculty members. The institutional voice report provides only guidelines, and University leaders who diverge from the suggested restraint will not face o!cial consequences.

Students concerned about McInnis’ vision for Yale

In October, McInnis told the News that she did not present “an academic vision that [was] that distinct” during the presidential search process that culminated in her selection. In that interview, McInnis instead emphasized her plans to pursue the University’s long term goals of further developing its science and engineering programs.

When asked this month about her vision for the University, McInnis cited her inaugural address, in which she spoke of five areas of focus for Yale’s future: increasing educational opportunities; maintaining Yale’s reputation; developing international partnerships; establishing “ever higher” academic expectations; and expanding faculty projects’ “collaboration and impact.”

She also encouraged the University community to have an “open mind” and “compassionate heart” in the speech, while drawing attention to free expression and rebuilding trust in higher education.

Manu Anpalagan ’26, who currently serves as the president of the Yale Republicans, wrote that he was unsatisfied with McInnis’ “lack of vision” for the University, which he found “disappointing and discouraging.” These remarks were echoed by Kai Padilla-Smith ’25, who told the News that he found McInnis’ policies “uninspiring.”

Meanwhile, Trevor MacKay ’25 — a former student president of the Buckley Institute — told the News that he appreciates that McInnis has not “rock[ed] the boat” in terms of policy decisions, while acknowledging that other students might have preferred more direct action.

University response to student initiatives, activism

Esha Garg ’26, the Yale College Council vice president for the past academic year, met with McInnis at the start of the academic

year for her YCC role. Garg told the News that McInnis expressed interest in student perspectives and in incorporating their opinions into her vision for the University in that meeting.

However, when the undergraduate student body overwhelmingly passed a referendum recommending University divestment from weapons manufacturers, McInnis responded briefly.

In December, the YCC administered a referendum that asked students whether the University should disclose and divest from military weapons manufacturers and suppliers, as well as invest in Palestinian scholars and students based on its mission statement.

Of the 3,338 undergraduates who answered the question, 83.1 percent voted for disclosure, while 76.6 and 79.5 percent voted for divestment and Palestinian scholarship, respectively.

McInnis responded to the results with a five-sentence statement, directing students to Yale’s policies on investor responsibility and procedures of the Advisory Committee on Investor Responsibility, or ACIR.

“Her response to thousands of students demanding change was insultingly brief, and made it clear that she is not really interested in our opinions,” wrote Padilla-Smith, who was involved in the divestment campaign organized by the pro-Palestinian Sumud Coalition.

Sahar Tartak ’26 — who has previously authored opinion pieces that criticize the University’s actions — wrote that it “would have been nice to see a substantive rejection of the divestment proposal as anti-American and antisemitic.” She told the News, “McInnis should embrace our country and all the good it has to offer, as well as what the Jewish people o er the world.”

In an email to the News, McInnis pointed out that she, Yale College Dean Pericles Lewis, Provost Scott Strobel, Secretary Kimberly Goff-Crews, trustees and other University leaders have met with student organizations and individual students about the subjects considered within the YCC referendum.

She added that during the 2025 spring semester, the ACIR communicated to members of the Sumud Coalition that their presentation on military weapons manufacturers “did not include new material information” that would provoke the ACIR to review its previous decision not to divest from such entities.

McInnis wrote to the News that she does not meet with student groups regarding matters already reviewed by the ACIR.

Former YCC President Julian Suh-Toma ’25 said that “it remains to be seen” whether McInnis will demonstrate a commitment to community members’ opinions and at times, criticisms. However, he told the News that he is confident students will continue to call “for Yale to do better” and hopes McInnis will listen with an “open mind and heart.”

McInnis emphasized free expression in her end of year message, in which she stressed that individuals must follow “the rule of law and university policies. These policies — such as neutral time, place, and manner guidelines — do not favor any particular group or viewpoint.”

The end of year message came days after pro-Palestinan protests, which coincided with a far right Israeli minister’s visit to Shabtai — a Jewish intellectual discussion society, independent from the University — on April 23.

Soon after, the University revoked Yalies4Palestine status as a registered student group in a press release that cited violation of protest policy as grounds for the decision and pointed to the group’s social media post calling others to participate, although acknowledging that the demonstrations were not a!liated with Yalies4Palestine or any o!cial student organization.

MacKay praised McInnis’ immediate response to the April encampment and emphasized the need for regulation and order on campus.

“A university, like society, requires rule of law and equal application of its regulations,” MacKay wrote to the News. “I hope that President McInnis continues to show zero tolerance for the disruptive behavior we have seen on Beinecke Plaza and Cross Campus in recent years.”

Federal funding uncertain amidst criticism of higher education

Since President Donald Trump’s inauguration in January, his administration has directly targeted seven universities’ federal funding — including all Ivy League schools except for Dartmouth and Yale. Meanwhile, the National Institutes of Health has slashed indirect research funding and halted grants awarded to at least 17 Yale-a!liated researchers as of April 23.

During the 2024 fiscal year, the University received $899 million in federal grants, with over $643 million coming from the NIH.

Responding to NIH plans to cut funding for indirect research costs, McInnis issued her first statement that articulated an opinion about a contentious subject, in which she condemned the NIH’s plan to dramatically strip funding for indirect research costs.

“The NIH indirect cost cap substantially harms Yale’s core research mission and has severe consequences for institutions of higher education in this nation, and that is why I commented,” McInnis told the News in February.

During her April inaugural address, McInnis emphasized the University’s ability to endure, while acknowledging decreased confidence in higher education which Yale will work to “rebuild.” Just days after that speech, McInnis announced that she had convened a faculty Committee on Trust in Higher Education.

McInnis quiet in public, but pursues lobbying in Washington McInnis has previously said that she believes behind the scenes work is the most influential. In December, she told the News that she would increase her lobbying work and travel to Washington regularly during the upcoming semester, as well as open a Yale office in the capital. She said that she was not certain that “a lot of public pronouncements” would necessarily be impactful in advocating for the “mission of higher education.”

McInnis has refrained from commenting on Harvard’s response to federal pressure, and its refusal to cooperate with the Trump administration’s demands. She emphasized the respect that is demonstrated by not commenting on other universities’ decisions, instead “trusting” that leaders will determine what “best serve their communities.” McInnis also cited her work with the Association of American Universities, a collective of 71 research universities. She noted her commitment to preserving free speech and intellectual freedom at Yale, as well as advocating for higher education’s independence — which she “firmly” believes are “in the strategic interests of our nation.”

Students and faculty have urged the University to publicly denounce Trump and support Havard’s noncompliance with the administration’s demands. In April, McInnis signed a statement amongst over 360 university leaders, denouncing the “coercive use of public research funding.”

“I definitely would want her to take a stand with Harvard. Again, I can understand her hesitancy to do so, given perhaps the funding challenges that we would come under,” said Lu. “But I think at the end of the day, history will look favorably upon Harvard.”

Lu noted that the University has “survived” for over 300 years — echoing McInnis’ own remarks at her inauguration — and has significant financial resources. He said that supporting Harvard was a cause “worth fighting for” and that he hoped McInnis would be more outspoken about the matter.

McInnis is the first woman to serve as Yale’s President in a non-interim capacity.

Contact ISOBEL MCCLURE at isobel.mcclure@yale.edu .

BY YOLANDA WANG STAFF REPORTER

The federal government has reactivated the immigration status records of all four Yale students whose records were previously terminated, according to a Yale administrator.

Ozan Say, the director of Yale’s Office of International Students and Scholars, or OISS, told the News on April 7 that the o!ce had learned that the records of two international students had been terminated in the Student and Exchange Visitor Information System, or SEVIS, a federal database of students on non-immigrant visas. The records of two more students were terminated on April 10.

On Friday, the Trump administration announced that it would

restore the SEVIS records of thousands of international students, thereby reinstating their legal right to study in the U.S. “I can confirm that as of this afternoon, two of the four Yale community members impacted by SEVIS terminations have been returned to active status,” Say wrote to the News on Friday.

On Saturday evening, Say wrote to the News that the records of the two remaining students had also been reinstated.

While visa status and SEVIS record status are not the same, international students on F-1 visas who have had their SEVIS records terminated are effectively unable to extend their legal status to study in the U.S. and may be forced to leave the country. According to a Department

of Homeland Security webpage, when a student’s status in SEVIS has been terminated, federal immigration law enforcement agents “may investigate to confirm the departure of the student” from the U.S. Say did not specify whether the four international Yale students whose terminated SEVIS statuses he tracked included students employed under optional practical training, or OPT, a temporary work authorization that allows international students with F-1 visas to work for up to 12 months in their major area of study after completing their degrees. Many of the individuals whose SEVIS statuses were terminated in April — including two students in New Haven involved in an anonymous lawsuit against the Trump

administration — are graduates employed through OPT.

Since the government’s Friday announcement that it would restore SEVIS records, federal immigration officials have warned that students who have had their records reactivated may still face the potential termination of their records and visas in the future.

“We have not reversed course on a single visa revocation,” Tricia McLaughlin, assistant secretary for public affairs at the DHS, wrote to the News on Friday. “What we did is restore SEVIS access for people who had not had their visa revoked.”

The status reactivations come after two Yale students, along with two students at the University of Connecticut, filed a class action

lawsuit on Thursday, accusing the Department of Homeland Security of “unlawfully terminating” their SEVIS records. The plaintiffs, represented by the American Civil Liberties Union of Connecticut, argued that the lack of “meaningful explanation” for the terminations violated the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment and the Administrative Procedure Act, which requires a “lawful basis” for any action by a government agency.

Yale has partnered with immigration attorneys who can provide short-term legal assistance to international students, according to the OISS website.

Contact YOLANDA WANG at yolanda.wang@yale.edu .

BY YOLANDA WANG STAFF REPORTER

Over 400 faculty and Yale community members rallied on Cross Campus against political attacks on higher education on Thursday.

The rally, organized by Yale’s chapter of the American Association of University Professors, was part of a national day of action and followed weeks of faculty organizing to urge University administrators to publicly resist President Donald Trump’s policies threatening Yale’s research and values.

“No to the defunding of university research, no to the targeting of international students and immigrant workers, no to the suppression of free speech and protest, no to attacks on unions and on workers,” Adam Waters, president of Local 33 UNITE HERE, Yale’s graduate workers’ union, said during a speech at the rally.

During the first three months of Trump’s presidency, the federal government targeted higher education, citing universities’ failure to address antisemitism as a reason for slashing research funding and detaining international student protesters.

More than a dozen faculty members and union leaders spoke at the rally on the importance of their work as academics and University employees.

Many of the speakers emphasized the need for faculty, students, University workers and other community members to stand together in their advocacy against Trump’s policies.

“These threats are not limited to one part of the university or one field,” professor Daniel HoSang, president of Yale’s AAUP chapter, told the News. “They’re widespread, and we recognize that there’s an intention to try to play different fields against one another, to isolate people.”

According to HoSang, the rally took weeks of planning calls, during which faculty at di erent universities shared ideas for how to mobilize against research funding cuts and the deportation of student protesters.

Faculty speaker Phillip Atiba Solomon extended his attention beyond threats to faculty and students and highlighted how advocacy concerning sectors such as policing and transportation is also necessary.

“If we are just here for ourselves and our students, we are not here for enough,” Solomon said. “That is the easy work.”

Solomon also argued that given Yale’s large endowment size at $41.4 billion, the University is one of the most well-resourced institutions to combat Trump’s attacks on higher education.

A University spokesperson wrote to the News that Yale President Maurie McInnis and Provost Scott Strobel will “continue to engage” with faculty concerns.

Taran Samarth, a graduate student member of Local 33, told the News that there has been a long history of cross-coalition organizing among the local unions for graduate students, technical sta and maintenance sta

New Haven Mayor Justin Elicker was also present at the rally. Elicker told the News that while his views may have differed from those of some pro-Palestinian student protesters in the past, there is “no gap” between him and the rally attendees when it comes to defending free speech, international students and research funding.

“It’s inspiring to see a lot of people coming out publicly to push back against the Trump administration, and I think we need a lot more of that,” Elicker said.

Some students held up a pro-Palestinian banner calling for divestment throughout the rally, while others held up Palestinian flags.

The last major renovation of Cross Campus was completed in 1968–1969.

Contact YOLANDA WANG at yolanda.wang@yale.edu .

BY YOLANDA WANG STAFF REPORTER

Yale is considering selling a portfolio on the private equity secondaries market, a University spokesperson confirmed to the News.

The University did not specify a target size for the sale. However, the transaction could total up to $6 billion in value, according to Secondaries Investor, a site providing industry insights for investors. In the 2024 fiscal year, the Yale endowment grew to a total of $41.4 billion. By selling on the secondaries market, Yale would be able to convert its private equity assets into liquid assets that are more readily spendable.

“The University is exploring a sale of private equity fund interests and is being advised by Evercore in a process that has been in the works for many months,” a University spokesperson wrote in an email to the News.

Evercore is an independent investment bank that provides services such as financial research, institutional asset management and private equity investing.

According to Secondaries Investor, this is Yale’s first known sale in the secondaries market, which allows investors to buy existing assets from other investors rather than directly purchasing stakes from private companies.

Yale’s investment strategy prioritizes the diversification of assets away from traditional U.S. equities and bonds and into alternative investments such as private equity, venture capital, hedge funds and real estate. Last year, the University reported that roughly 95 percent of its endowment is invested in these alternative assets.

“We remain committed to private equity investments as a major part of our investment program and continue to make new commitments to funds raised by our current investment managers,” the spokesperson wrote. “In addition, we continue to actively seek new relationships with private equity firms in the Endowment.”

Yale’s major portfolio sale comes after the University announced that its budget would be “far more constrained” for the 2026 fiscal year due to low endowment returns. While Yale’s 10-year investment return of 9.5 percent places it in second place among the eight Ivy League endowments, its short-term endowment performance has lagged behind. For the past three fiscal years, Yale’s annual investment returns have not reached the 8.25 percent threshold needed to sustain the University’s current level of endowment spending.

Yale administrators also identified proposals from President Donald Trump’s administration to increase endowment taxes and to cut federal funding for research as threats to Yale’s finances and reasons for reductions to spending. Already, the University has announced cuts to spending on faculty raises, faculty and staff hiring, campus construction and other non-salary expenditures.

Elihu Yale established Yale’s endowment in 1718 with a donation of 562 British pounds.

Contact YOLANDA WANG at yolanda.wang@yale.edu .

BY ASUKA KODA STAFF REPORTER

Following an abrupt notification from the U.S. Agency for International Development, Yale researchers lost support for a project establishing Chad’s first National Institute of Public Health and a $15 million award for health education initiatives in Liberia.

The first round of grant terminations revoked funding for five global health projects at Yale, according to an internal survey from the Yale Institute for Global Health in February. The News spoke with two researchers whose projects were suddenly terminated. Some other researchers declined to comment.

Building public health infrastructure in Chad

Amy Bei, an associate professor at the School of Public Health, had been leading two global health initiatives reliant on USAID funding: a program to build Chad’s first National Institute of Public Health and establish a national genomic surveillance system and a separate malaria vaccine project conducted across multiple African countries.

Bei’s work came to a halt after she received a stop-work order from USAID in January. The letter did not mention Bei’s research specifically and stated that the stop-work order was e ective immediately.

However, the letter noted that the “Secretary of State has approved waivers of the pause under the Executive Order, subject to further review, with respect to emergency food assistance, salaries and related administrative expenses for all personal ser-

vices contractors and legitimate expenses incurred prior to January 24th,” among other exceptions.

Unlike wealthier nations, Chad lacks the resources to independently track disease outbreaks. Bei’s program sought to change that by training epidemiologists and laboratory specialists to monitor malaria, dengue, antimicrobial resistance and vaccine e!cacy through cutting-edge genomic tools. This investment, Bei explained, was critical for empowering Chad to identify and respond to public health threats without waiting for external help.

“The whole goal is to strategically build up these platforms and build up the training of people with self su!ciency in mind,” Bei said. Having local genomic surveillance capacity, which is the ability to continuously monitor pathogens to track how they evolve and spread, is about speed, accuracy and survival. During past outbreaks, including COVID-19, countries without in-country genomic surveillance often had to ship biological samples abroad and wait weeks or months for data.

“When we think about public health surveillance, it really has to be ongoing, routine, with quick turnaround times from identification and sequence of the pathogen into actionable information. Otherwise, it’s kind of like historical research,” Bei said.

Bei’s work had already achieved several firsts for Chad. During a dengue outbreak, her team successfully trained local health workers to sequence virus samples in-country, which is much more efficient than sending samples overseas.

When Bei received the stopwork order, plans were underway to extend genomic surveillance to malaria, which would have included drug resistance monitoring and vaccine response tracking.

“We have trained over 200 medical and public health care practitioners through the program, most of whom have participated in deep and repeated training,” she said.

Meanwhile, Bei’s second project, a next-generation malaria vaccine consortium, led by African partner sites, involving Institut Pasteur de Dakar, Yale, Oxford and several African institutions, was also impacted.

Although the consortium itself is primarily funded by the European Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership, its foundational clinical trials were funded through USAID. The sudden halt to those trials has slowed the overall progress of malaria vaccine development efforts in the region.

A Decade of Progress in Liberia at Risk

On Feb. 24, Kristina Talbert-Slagle GRD ’07 ’10, an assistant professor at the Yale School of Medicine, received a similar grant termination notice from USAID. Her project focused on longterm investments in Liberia’s health education, hospital management and workforce training, including a goal to transform education at the country’s only medical school. She started the project when the Ebola epidemic ended in 2015, aiming to rebuild a healthcare system that had been shattered by the crisis.

“Liberia is still a post-war, resource-constrained country, and we have more work to do in rebuilding its still-fragile health system,” wrote Talbert-Slagle. “We can’t put the brakes on health systems that work like this and expect to keep the next global health security threat at bay.”