08

Shelly Kagan: The Making of a Public Philosopher PROFILE | EDWArd seol

21 30

A Hard Pill to Swallow feature | lekha sunder

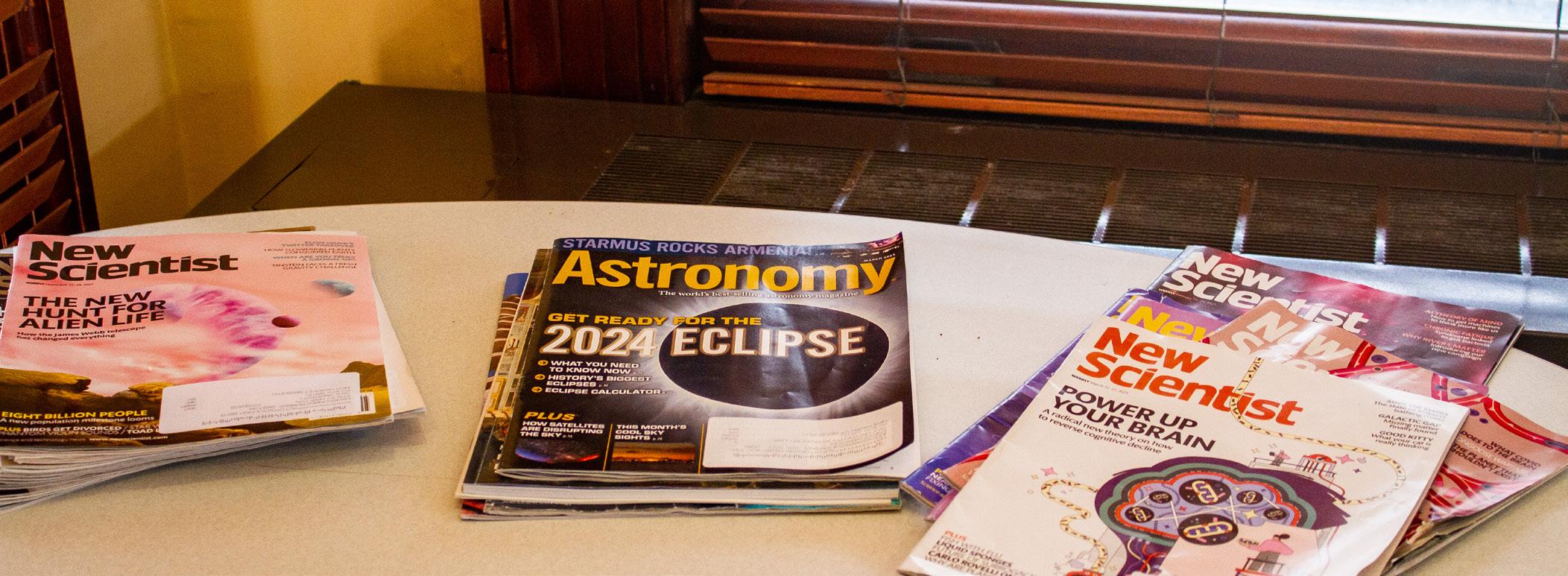

TL;DR Who Wants to Read This? culture | olivia wedemeyer

08

Shelly Kagan: The Making of a Public Philosopher PROFILE | EDWArd seol

21 30

A Hard Pill to Swallow feature | lekha sunder

TL;DR Who Wants to Read This? culture | olivia wedemeyer

Davis

Magazine Editors

Michelle Ampofo

Ana Padilla Castellanos

Kinnia Cheuk

Abigail Sylvor Greenberg

Gavin Guerrette

Wilhelmina Graff

Zack Hauptman

Hannah Han

Audrey Kolker

Margot Lee

Harper Love

Isabel Maney

Idone Rhodes

Olivia Wedemeyer

Creative Director

Catherine Kwon

Design Editor

Christy Lau

Clarissa Tan

Photography Editors

Gavin Guerette

Yasmine Halmane

Tenzin Jorden

Tim Tai

Giri Viswanathan

Illustration Editors

Jessai Flores

Ariane de Gennaro

Editor in Chief & President

Lucy Hodgman

Publisher

Olivia Zhang

They say it takes a village to raise a child, and I think a magazine is similar. The product in your hands (or on your screen) has been formed by many many people working together and apart—writers and editors and photographers, the trusted friends whom those writers and editors and photographers consulted for advice, a robust team of illustrators and designers, moms we called on the phone to vent and complain.

A lot of pieces in this issue are also concerned with various proverbial villages—structures of community care which succeed and fail in varying degrees.

Krishna Davis’ cover story, “Barriers to Entry,” probes at the drawbacks and promises of urban renewal in New Haven’s developing Winchester Center. In “A Tough Pill to Swallow,” Lekha Sunder takes on Yale Health’s overprescription of psychotropic medications, illuminating a new dimension in an ongoing conversation about the university’s approach to mental health. And in Bluebelle Carroll’s piece of short fiction, “Duty Bound,” a layperson becomes a quasi-professional ‘emergency contact’ for strangers in dire straits. At stake in all of these pieces, as well as many others in the issue, is a question about community. What do institutions owe us, and what do we owe each other? How do we make good on those responsibilities? If it takes a village to raise a child, what does it take to create and sustain a village? (Has this metaphor outlasted its use??)

As I near the end of my tenure as Editor-in-Chief at the YDN Magazine, I am deeply grateful for every person who has offered their vision and time to this magazine.

Enjoy.

Abigail Sylvor Greenberg

Illustrated by Catherine Kwon

Society has long moved past ripped jeans and pole-sitting as the core tenets of youth culture. Who needs those when 40 minutes of music can do the trick? Each issue, this column will explore the intersection between the youth experience and a brand new album.

Throughout indie singer Samia (Samia Najimy Finnerty)'s sophomore album Honey, we meet what feels like dozens of characters. Amelia’s the one with the half smile. Caleb—he’s by the fire pit, scaling the beyond. Everything with David is totally fine. These are brief, lyrical introductions that leave the listener with no more than one or two details. In the album’s tight 40-minute runtime, particulars like these offer us a fleeting glimpse into Samia’s world.

These “who’s who” moments make Honey both a profound piece of sonic storytelling and a narrow look into Samia’s individual experience. She has been honing her indie-pop craft since breaking out in 2017 with a string of standalone singles including “Welcome to Eden.” She has since earned a reputation among indie listeners as an powerful alternative vocalist with a penchant for poetic lyrics and catchy melodies. (Find her sandwiched between acts like Lucy Dacus and Soccer Mommy on any algorithmic

gets personal, but she loses the audience a little on the way. After all, as relatable as the circumstance might be, we’ll never know exactly what Amelia, Caleb, or David are supposed to mean to us.

Samia shines on Honey when she addresses her intimate—yet relatable—experience as a twenty-something navigating heartbreak, growing pains, and newfound freedom. In the opening track, “Kill Her Freak Out,” Samia croons about love lost over a bare-bones synth pad progression. She doesn’t need intricate instrumentation to hammer home the severity of her sentiment: “I hope you marry the girl from your hometown, and I’ll fucking kill her, and I’ll fucking freak out,” she recites calmly. Samia gives voice to the passionate anguish familiar to any young victim of heartache.

On the flip side, Samia estranges her audience in the hyperspecificity of songs like

“Pink Balloon.” In the album’s vinyl notes, she describes the song as an ode to the complex nature of close friendships: “I wanted to tell [the story of a friendship that got too close and complicated] from a bird’s eye perspective… Even when you think you know someone really well you only have your vantage point.” But ultimately, she leans too heavily into her own “vantage point,” hindering the listener’s ability to access the experience that she’s trying to capture. Extraneous details about Los Angeles family dinners and the nerves that Samia gets during a full moon leave the artist’s exact meaning unclear. Especially when placed atop a backdrop of spare piano balladry, the song leaves the listener with little to grab onto beyond a pretty melody. What could have been a painfully relatable serenade is little more than a wash of particulars.

A rousing instrumental palette lifts the album out of the occasional lyrical rut. Tracks like “Mad at Me,” an early album single featuring Minneapolis-based artist papa mbye, best showcase the depths of Samia’s sonic experimentation. “Mad at Me” places the artist into unfamiliar territory—glitch-pop drums with pulsating bass grooves and shimmering synth keys are a departure from her typical guitar-driven indie sound. She deftly croons over the danceable syncopation which culminates in one of the catchiest hooks of the year. “Are you still,” she begins, wailing over choppy snares and watery guitars, “mad at me?” The song, which leans on modern references (“Clear the cache, watch your feet, keep going”), has equally contemporary instrumentation to back it up.

Samia’s softer serenading and her pop-infused grooves intersect in “Sea Lions.” The track begins as a tranquil piano number, reeling in listeners with low-filtered keys and spare atmospheric pads. But the composition begins to morph as listeners advance through the five-minute runtime. A quiet wave of crunchy synth risers provides the audience’s final warning before a shout—“Why does your phone keep going to voicemail?” A cascade of instruments floods the mix. Plucky bass groves, glitched-out synth brass elements, staccato percussion, and reverb-soaked swells fall on the listener all at once, giving the entire album a necessary halftime kick. In moments like these, it doesn’t matter whether you understand Samia’s niche, autobiographical references or not. She lets the music carry the emotional weight.

Perhaps the ethos of Honey is best summed up in the chant that Samia sings at the end of the title track: “It’s all honey, honey.” Her tone dances between cathartic and sarcastic as she repeats the phrase 18 times. After so many minutes spent parsing heartbreak, disappointment, and emotional strain, it’s challenging for listeners to take her at her word; however, countless repetitions of the phrase begin to unveil new meanings. It seems that all the long nights and turmoil that have comprised Samia’s youth thus far have culminated in something messy, sweet, and tough to swallow. Over the course of 11 tracks, the album’s characters, places, and names flow into a glossy, fluid image of youth. Even if we haven’t lived Samia’s life and can’t understand every reference she makes, we can agree: It’s all honey, honey.

They are everywhere.

By “they” I mean the bells—at least if you’re walking, eating, or hoping to nap within a quarter mile of Harkness Tower. But I also mean the perpetrators of the pealing: the Guild of Carillonneurs. Maybe you didn’t know that there were actual people playing the bells. (There are 24.) Maybe you didn’t know that every year, undergrads line up for a chance to play the carillon, an instrument that requires perfect quadrupedal coordination to play and usually still sounds kinda bad. Maybe you didn’t know that after an exhaustive (five-week!) heeling process, the Guild turns these hopefuls away in droves.

I am tortured by the chimes. If I cannot outrun them, I must consume them. Who are these carillonneurs? What is their problem? What are their secrets? Are they evil? Tonedeaf? Do they simply wish to be heard?

I needed the truth: So I climbed a bunch of stairs.

Like many inspirational feats of dauntless investigative journalism, my tour of Harkness Tower began with personal failure. Zoe Pian ’25 led me up the endless spiral staircase, each step (first stone, then metal) labeled with how many calories we’d burned so far—5.6, 9.6, etc.— and then I remembered I was afraid of heights. I decided to distract myself from mortal terror by focusing on the great many objects of anthropological interest which I beheld.

I learned from a placard in the tower’s unfinished (and, in my opinion, haunted) second-floor museum that the Freshman Bell-

ringers Heeling Competition of November 16, 1964 offered its participants free beer. A Christmas list from December of 2013 hung on the wall of a room in the middle of Harkness Tower: “Dear Santa, I have been very good and extra nice this year. I would really like to find one of these under the tree….” Someone had written “soft, nice high bells.” Another had written “ESCALATOR.” There was a poster of Harkness Tower, on which a large overlapping printout of Drake Bell (from the seminal Nickelodeon sitcom Drake & Josh) was leaning insouciantly. “Ringring,” said a little speech bubble next to his mouth. I shivered.

I asked Kimie Han ’23, one of the Guild’s co-presidents, whether or not the bells had any secrets. Kimie pointed out that the bells were pretty loud, so it would be difficult to hide any sinister goings-on from the public. This convenient, rational answer would not impede my investigation. I searched for further mischief.

And further mischief was revealed. Every other year—with a notable pandemic hiatus—the Guild travels to the Royal Carillon School in Belgium (Bell-gium!) like moths to the flame. While in Europe, they travel to monasteries and commune with the monks, who also play bells. This made sense to me as an activity for a monk. Less so for a bunch of twenty-one year olds.

“Is it fun?” I asked.

“It’s intense,” said Evan Hochstein ’23. “It was mostly just going from belltower to belltower and playing the bells.”

Still, there was thrill: “Lots of climbing on very concerning staircases, I have to say.”

Fun fact: the word carillonneur is very difficult to spell. It’s pronounced care-ill-onUR. (“If that guy we met in Belgium wasn’t lying to us,” says Zoe.)

Zoe was full of fun facts. I asked for a complete history of bells everywhere; she complied immediately and with gusto. “If you imagine carillon as an art…” she began. I imagined. I was swept into a world where every year, bell-ringers across the country flock to attend the Guild of North American Carillonneurs Conference (or simply “Congress,” to those in the know).

I learned that the Yale Guild is not only prestigious, but the first and only student-run guild in all of North America. GCNA isn’t fond of their spunky and revolutionary presence, but Yale is the sole reason the average GCNA member isn’t 79 years old, so there exists a grudging peace.

Matching Yale’s reputation is an equally large endowment—entirely student run. So what kind of money were we talking? “I don’t think I’m going to give that to you,” said Julia Zheng ’23, the other co-president of the Guild. Like a child with divorced parents, I went back to Kimie for what I wanted.

“Just give me a number,” I pleaded. “I won’t tell anyone.” This was not going to happen. Then I had a stroke of genius. “Could you give me an over-under? Is it more than 30,000 a year?”

“Yes,” Kimie smiled. I realized I was probably low balling it and had totally wasted my over-under.

What do they do with all that money? At least some of the budget, I learned, goes toward “Bell Maintenance”: a massive bill sent to the creepily-named company Meeks and Watson, whose minions have

shown up twice a year since 1912 to perform their sorcery on the machines. My sole attempt at serious journalistic inquiry was foiled immediately by my complete lack of patience for their janky website (and my admittedly unimpressive investigative spirit). I decided instead to examine the bells themselves.

Each bell has been carved with the phrase “For God, For Country, and For Yale,” probably in case they wander off and need to be returned. But it was too dark in the tower to tell anything, except that the bells were big. Really big. Their shadows loomed. I worried for my health.

“How big is the biggest bell? Is it bigger than you?” I asked Zoe.

“Oh, that’s for sure,” said Zoe. It turned out that the bells weigh a total of 54 tons. I did not enjoy learning this fact.

“How does it not all fall down?” I asked.

“I don’t want to think about it,” said Zoe. She smiled. We continued the tour.

The carillon is, to speak architecturally, weird. Each bell produces a minor third overtone, which is what makes them sound “sort of…” Evan trailed off, searching for the right phrase. “Out of tune,” he finished. Didn’t they ever try to give the bells a different overtone? Like, a major one? Yes, said Evan, but the short answer was that the bells just didn’t sound right without the tragic resonance. I nodded. It would be terrible, the bells not sounding right.

Zoe explained that the bells didn’t have dampers—once a note is hit, it will play until it’s ready to stop. I already knew this, because I have ears. But I didn’t know that the higher bells are so much smaller than the lower bells that their relatively shorter resounding period means a song with too many lower notes sounds terrible. And as the weather changes, the metal dictating the distance between the clappers and the bells begins to warp. It will deliver a harsh, tinny sound if too contracted and a deafening toll if too expanded. The bells offer no variances of timbre or texture, “so there are certain pieces that will never sound good.”

Does the Guild then dictate what kind of piece can be played on the carillon?

“Nope.”

Was there any predetermined order to what songs were performed, setting some kind of tone or flow for the day, so that one might not have to experience the whiplash of, say, hearing Doja Cat’s 2021 hit “Kiss Me More” right after a Beethoven transposition?

“We say to play whatever you feel like.” How long do members practice their pieces on the console before subjecting the immediate public to their talent?

Well, said Zoe, the thing is that you can practice to perfection on the console, but once you get on the real bells it will “sound like crap.” Sometimes they just give up and improvise.

This information filled me with white hot rage.

So what did Zoe think of the bells as an instrument? “They’re neat.”

Many Yale students have no idea real people are up in Harkness Tower playing the carillon twice a day. When they learn, they react rather strongly.

“If a person lives in Branford I usually get, like, complete vitriol,” said Zoe. “I realize how loud it is. They’re not lying.” Julia agreed.

“A lot of people in Branford hate us.” Evan was dismissive. “So you’re the ones who keep waking me up from my naps. If you’re taking a nap at dinnertime, that’s kind of on you.”

The bells are a public instrument. They mix with the noises of the world around them, forming a unique soundscape each time they chime. Everyone in the vicinity of Harkness Tower hears the carillon as it rings—the tone-deaf heartbeat of Old Campus.

So even when they won’t sound fantastic

on the bells, some guild members like to play popular or recognizable music for their wide and often unappreciative audience. Evan has added a Minecraft song to his repertoire: “If I know that someone is going to be hearing what I’m playing and be like I know that song! I grew up with that song!, brightening someone’s day…”

I smiled. I remembered leaving a grueling class in LC one afternoon and perking up to hear that someone on the carillon was playing the Pink Panther theme, my grandfather’s favorite song to hum in the mornings.

This sentiment was a moment of weakness. It was exploited at once.

“I’m glad you’re writing about us,” said Julia, innocently. “We’d have overall better relations with people in the community if they knew about us.”

Much like the bells, I had been played.

To end our tour, Zoe treated me to a song she’d been working on called “American Gothic.” It was stately and peaceful. I leaned on the corner of the little blue room high up in Harkness Tower. I’d caught the beautiful, terrifying views of Old Campus and the Branford courtyard and the last of the orange sunset, and now I watched. Zoe at the carillon was a whole-body experience: she pounded at the handles with her fists and feet, torso swiveling, submerging the room in sound waves with each hit. It reminded me of a very excessive core workout.

I took a second to tune in—to stop thinking about my thwarted naps, or my overdue readings, or the fact that I had failed to unearth even a little hard evidence of the Yale Guild of Carillonneurs’ completely obvious cunning and deceit. I felt the thrum of the walls, the floor, and the air. I thought of the whole campus: people listening, people stopping to listen. Just as the Guild planned, I liked what I heard.

— Audrey Kolker Illustrated by Catherine Kwon

Illustrated by Catherine Kwon

Shelly Kagan sits cross-legged on a table at the front of the room, introducing the trolley problem for the thousandth time. He wears blue jeans and black converse sneakers. He asks that his students call him by his first name. All is at peace. Suddenly, a hand goes up. He bounces off the table, responding with a joy and earnestness befitting the expectation of discovery.

This exuberant style captures what makes Kagan charming to audiences around the world. He treats philosophy not as an ivory tower indulgence, but as a lively activity for everyone.

Every year Kagan’s “Introduction to Ethics” course draws over a hundred undergraduates; his Bulldog Days lecture causes Battell Chapel to overflow with prospective students. His recorded lectures on the philosophy of death have been viewed more than thirty million times in China, and his book based on that lecture series, Death (2012), was a national bestseller in South Korea. In a word, Shelly Kagan is the closest figure Yale has to a public philosopher.

Kagan did not carefully sculpt his persona or make detailed career plans. In fact, sitting down with Kagan reveals one striking quality: spontaneity. His speech is off-the-cuff, with an intonation that makes each string of sentences feel like a journey of grasping a kernel of the truth, losing it, and starting over again. Kagan is like this at all times, from a casual conversation in office hours to the seminar room. The free-wheeling approach is completely natural to him.

At the root of Kagan’s energetic demeanor is a deep love for his craft. Philosophy for him has never been a mere occupation defined by his contribution to academic literature. Instead, Kagan’s motive

has always been to seek the answers to big, enduring questions. It is from this original curiosity that everything—his style, his analytic rigor, his love of intellectual community—follows.

Kagan was interested in Jewish religious thought from an early age. Philosophy first drew his interest in high school after struggling to understand Martin Buber and Søren Kierkegaard’s commentaries on Genesis. “There was a considerable discussion of philosophical ideas that I was unfamiliar with,” Kagan said, “so I started reading philosophy.”

Kagan entered Wesleyan College in 1972 as a religion major and had plans to become a rabbi. Yet, a strong sense of community brought philosophy from the periphery to the center of his thinking. Kagan explains that at Wesleyan, philosophy majors often hung out in their department’s lounge talking to one another. In contrast, the religious studies building did not have a common area. As a result, he spent most of his intellectual life with fellow philosophy majors.

Kagan’s love of philosophy is inextricably linked to community. During his childhood, Kagan had a propensity to ask questions which sometimes left him on the social margins. “Finding philosophy was discovering there are other people who think the way I do and share my interest in thinking about ethics and the meaning of life,” Kagan said. After completing his studies at Wesleyan, Kagan pursued a PhD at Princeton, where his community grew. “We'd hang out and argue philosophy together constantly,” Kagan said of his doctoral cohort.

At Princeton, Kagan studied under two prominent philosophers: Thomas Nagel and Derek Parfit. “Tom really worked hard to teach me about philosophical depth, to not be satisfied with scoring quick superficial points,” Kagan recalled. This included cultivating Kagan’s ability to work through and understand the heart of a philosophical problem. During this time, Kagan practiced seeing issues from different perspectives, including ones he didn’t necessarily endorse. He frequently asked himself, “What kind of assumptions would make that an attractive position? What would it look like to view the world that way?”

After graduating from Princeton, Kagan taught at the University of Pittsburgh and the University of Illinois Chicago (UIC), before eventually making his way to Yale.

Kagan began his career focusing on debates in moral philosophy such as the nature of well-being, the limits of morality, and the role of desert in our ideas of justice. He first developed an interest in death during his time at UIC, when the department asked if he wanted to revive a past class on the subject. Death affects everyone and connects to numerous other topics in philosophy such as personal identity, value theory, and the nature of emotions. Kagan believed it would make a wonderful introduction to philosophy. After devising a new syllabus, he began teaching the class at UIC and continued teaching it at Yale.

When Open Yale Courses approached him about recording his lecture course on death, Kagan did not expect much. Launched in 2007, Open Yale Courses was a project

of Yale University to provide free and open access to video and course material from undergraduate courses. At the time, few universities were publishing class lectures on the internet for free. “Nobody had a real idea for the audience for them. I thought maybe about a half dozen kids in some dorm may look at the videos,” Kagan says.

Just a few years after Open Yale Courses published them, Kagan’s lectures had millions of views. His 2012 publication of Death, the book written after the course, sold over 230,000 copies in foreign editions and became a national bestseller in South Korea. The response was stunning. Kagan received emails from people around the world, from all walks of life. These messages ranged from brief thank-you notes to detailed refutations of arguments he referenced in his lectures. “I was completely blown away by how popular my death lectures had become,” Kagan said.

The interest around Kagan’s work snowballed far beyond the classroom. In 2010, China National Radio reported, “[Kagan’s] image, resembling that of an ‘immortal’ in Chinese mythology, has made him a ‘star’ closely followed by the youth in China.” His weekend workshop at the Yale Center Beijing was streamed live by 25,000 people, and during his visits, people lined up around blocks to get their books autographed. Kagan also appeared on South Korean radio and television, including a game show with a sold-out crowd of 3,000 people. To mimic the style of his lectures, the hosts even laid out a box on which Kagan could sit cross-legged.

Kagan’s likeness also began to be used in the arts—in rather unexpected ways. In New York, there was an experimental 2014 play about him called PHIL 176 / OBIT. “The play basically consisted of somebody being me,” Kagan

explained. Each day in the play, the actor gave one of my lectures. So for two weeks he gave half of the lectures from my death class.”

Japanese manga writers have planned to make a manga inspired by his course. Yale University Press and then Dean of Yale College Marvin Chun contacted Kagan to see if he approved of the usage. While Kagan anticipates the writers will only capture a fraction of his course’s content, his response was emphatic. “Are you crazy? Of course, I'm going to let them do this. Who's ever wanted to make a graphic novel about me before?”

Kagan remains grounded amid the uptick in profile. Even now, the interest in his work surprises him. Most of all, though, he feels appreciative: “The thought that the things that I published could have made a difference to people—it has just been an amazing, gratifying experience.”

Fame has not changed Kagan’s scholarly agenda. He still concentrates on moral philosophy, though he has explored new subjects like the ethical status of animals and moral skepticism.

His attitude towards academic work is distinctive. “There's a spectrum in terms of how much one’s philosophizing is a reaction to the literature, and how much it's just being spun out of their own mind,” Kagan explained. “I'm much more of the latter. And that means I don't spend a lot of time reading literature, which includes people that are responding to me.”

This attitude is a departure from a tendency in academia to emphasize contributions to existing literature and journal citations. Yet, it attests to the way Kagan has maintained his cu-

riosity throughout his work. Even as he maneuvers the minute details and arguments of a topic, he never loses sight of the purpose of the endeavor—to ultimately answer an important question. This approach has helped Kagan drive meaningful conversations with different audiences.

“Almost every philosophical problem grows out of a certain kind of puzzle that any ordinary person will, at one time or another, ask themselves,” Kagan said. “How do we know anything? What's the world really like? There's a part of you that is still pulled by these questions. If you want answers to them, you'll do better to try to explore them.”

This reasoning forms the basis for Kagan’s belief that philosophy is important for Yale students. The discipline offers a systematic way of studying and thinking about human nature and obligation.

“In college, you’re trying to decide who you are going to be,” Kagan explained. “You try on different worldviews for size. You check out different ideas and build up a set of values. Philosophy gives you alternative pictures that some of the greatest minds in history have come up with about what is a person? How should we live? What do we owe one another?”

Philosophy demands that we bring our actions in line with our beliefs. Kagan has taken this to heart. He became a vegetarian, for example, after “reading certain philosophical essays talking about the moral standing of animals.”

“It turns out fish are far more intelligent than I've ever given them credit for. So when I combined that with my moral views on why you should not eat beef, pork, chicken—suddenly, I

had to give a face. So I gave up fish,” Kagan said of his dietary switch. The spirit of moral philosophy is not abstract argumentation but searching for truths. They create our obligations.

While Kagan runs classes with his own flair, it took a few years at Yale before he found his rhythm. Kagan admits that in seminars he had to learn to give students space for discussion. “I love to talk. When students say something interesting in class, my knee-jerk reaction is to jump in and start talking with them. But since my goal in class is to get the students talking to each other, I need to constantly remind myself to keep more of my thoughts to myself.”

Lecturing has always come more easily to him than facilitating discussion. He does not read from a paper. Instead, he has a set of notes that he reviews before class. Otherwise, he’s just “thinking out loud in front of students.” As a result, his lectures change from year to year.

“I think of it a little bit like being a jazz performer. There's a basic score that you're riffing on, so any given performance will recognizably have the same melody as the last one, but on different occasions you expand on a part or cut an element out.”

Kagan has taught introductory ethics for over three decades. When asked if he ever gets tired of it, he smiled. “I only get to give a specific lecture once a year,” he reminded me. “A single lecture is like a piece of music I’m fond of and which I only get to play once a year. Far from being boring, it’s something I look forward to.”

While Kagan is a beloved educator, many students hesitate to register for his courses, especially the seminars. In the past, almost half of students have chosen to Credit/D/Fail his classes. Kagan is aware of his reputation as a difficult grader. He recognizes that his grading methodology demands certain responsibilities from him, including clear and detailed feedback.

Kagan’s support on papers carries the same spirit as when he stays up to an hour after class to answer every person’s last question. He has often “written more comments in terms of sheer number of words than the paper itself.” Kagan offers directions a paper could have taken, objections it might have considered, and comments on the specific aspects of the argument that succeeded and failed. “If I'm going to hold people to serious standards, I need to give them sufficiently detailed feedback so that they can meet those standards,” Kagan said.

It may seem an odd fact that some of the greatest philosophers, from Aristotle to Epicurus, have spilled ink on the subject of friendship. Yet, it is an important reminder that some of the ideas we take for granted can be the sustaining force behind our passion. Not only does friendship fulfill our basic desire to be accepted, but it clarifies our beliefs and how we understand ourselves.

Looking beyond his reputation and his storied quirks, what defines Kagan as an academic is a sincere love of discussing ideas with others.

This fact shows when he talks about his former students. His voice softens. Teaching philosophy has a meaning that transcends the halls of winning or losing a debate. Kagan says that his most rewarding moments come when alumni—ranging from one year to twenty years after graduation—write to tell him that his class impacted their lives. “When students tell me, ‘your class taught me how to think’ or ‘you changed my views in ways I didn’t appreciate at the time,’ I am moved beyond words. I am touched,” he said.

When asked if he had any plans to retire, Kagan smiled. Grateful to read books and discuss philosophy with curious and eager students, Kagan said he would like to teach for as long as possible. After all these years, the flame of his curiosity burns strong, with the same vigor of his own college years. “Philosophy is a never-ending feast of things to think about—an endless source of amazement, challenge, and bafflement.”

KRISHNA DAVIS

Photos by Matias Guevara Ruales

Cover Photo by Gavin Guerrette

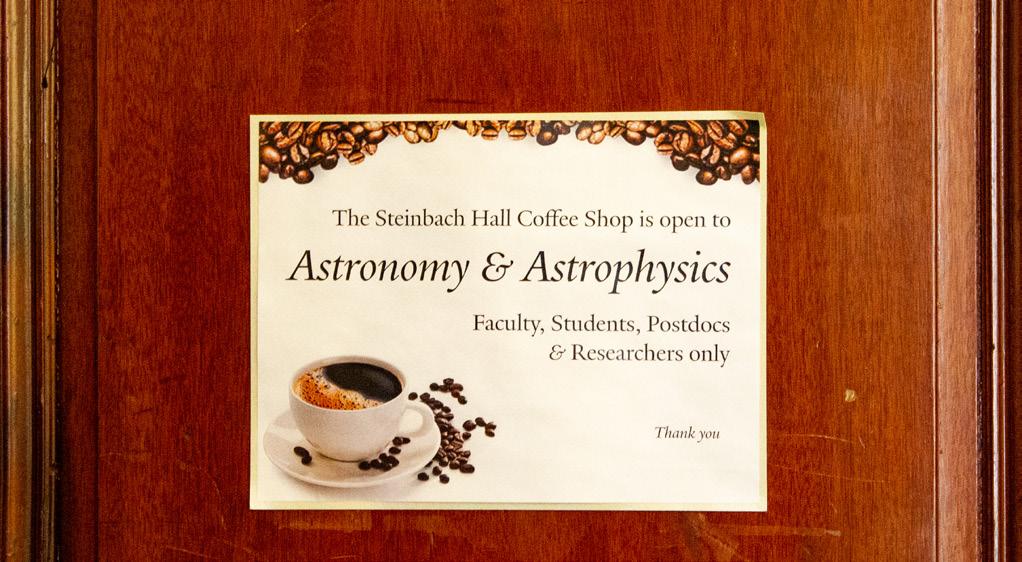

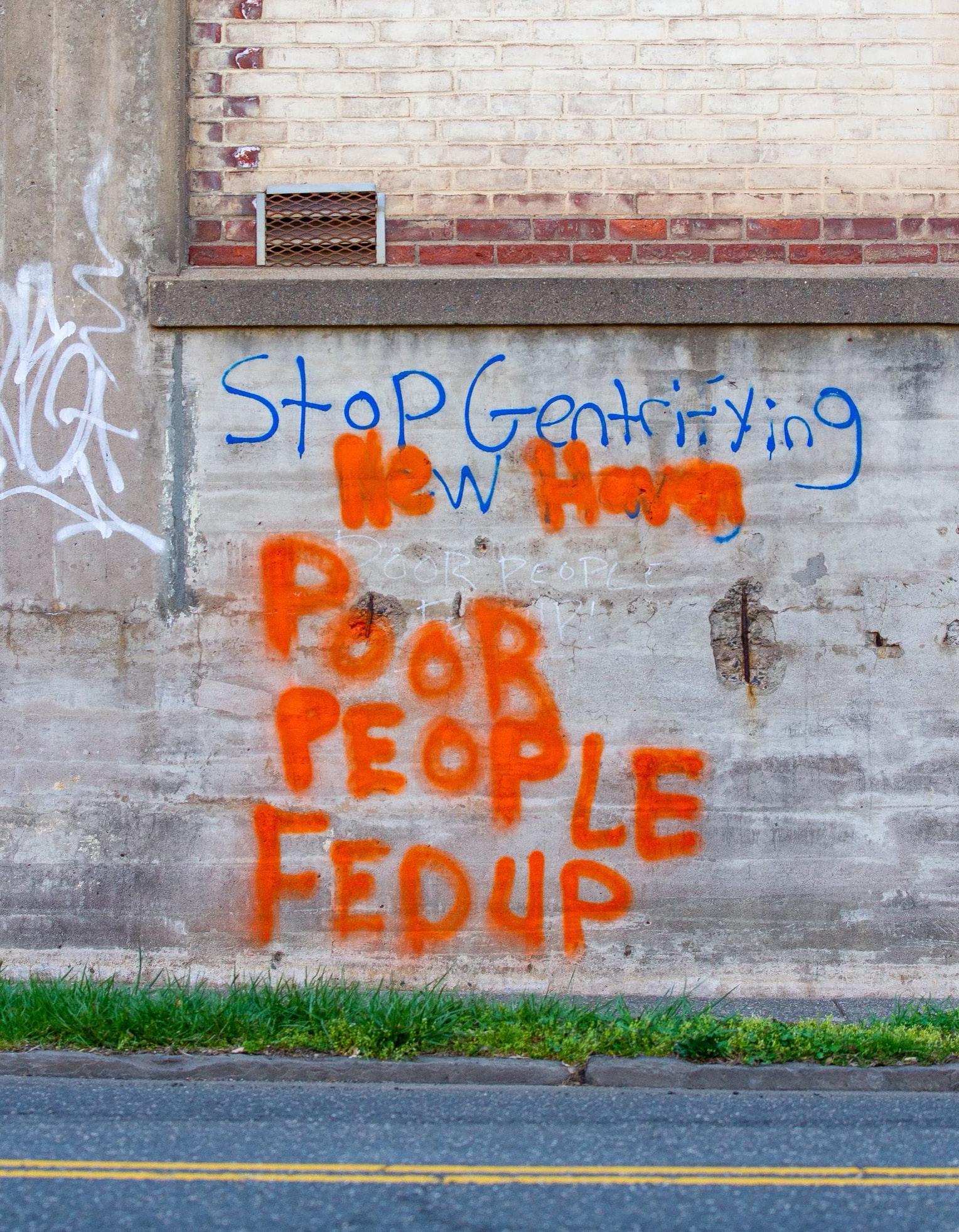

Property redevelopment is gripping a former industrial district at the edge of Yale’s campus. Will it turn into an opulent extension of Yale’s campus, a resource for New Haven communities, or a bit of both?

The ruins of the Winchester Repeating Arms factory stand at the corner of Munson and Mansfield streets, a twenty-minute walk from downtown New Haven and just steps from Yale’s Science Hill. Four stories of massive rectangular windows, framed by chipped concrete and faded brick, are cracked and missing from the building. The structure is rusty, quiet, and heavily contaminated.

Winchester Repeating Arms employed thousands of New Haven residents throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Most employees lived in Dixwell and Newhallville, two predominantly Black neighborhoods to the north and west of the manufacturing district where the building is located. Many long-time New Haveners from Dixwell and Newhallville have had some form of involvement with the factory, whether it employed a parent, a grandparent, or a great uncle. But decades of development—which began with the 1981 rebranding of the area as “Science Park at Yale—have given the district a new purpose as a hub for biotech startups and keep Yale graduates in New Haven. In the process, many former ties between New Haveners and the neighborhood have dissolved.

The decrepit building on the corner of Munson and Mansfield is the only Winchester Repeating Arms building in New Haven that has not already been torn down or converted. The area is a superblock of massive, mostly empty parking lots, decades-old lab buildings, Yale buildings, and the remaining factory buildings, as well as a K-8 school called the Highville Charter School & Change Academy. On nearby Winchester Avenue, the development of housing, retail, office, and lab-space is evidence of a district-wide master plan overseen by the Science Park Development Corporation and implemented by private developers.

After years of sluggish progress, Science Park at Yale will soon be reimagined yet again as “Winchester Center.” The area is finally poised to undergo another round of significant development in the next decade, similar to what can be seen on Winchester Avenue. The City Plan Commission approved plans in the spring of 2022 to build new housing, retail, and lab space in the district. The effort is to be led by Twining Properties and L+M Development Partners, real estate developers based in New York. When complete, the area will include hundreds of high-end apartments, as well as retail space and more office and lab facilities for biotech startups.

Twining Properties CEO and Yale graduate Alex Twining (’74), hopes the new development will reignite economic activity for Dixwell and Ne-

whallville. However, the development which has taken place incrementally in the Science Park area since 1981 has proven, at its core, to advance the interests of industry and Yale. With this in mind, the new project’s impact on the surrounding New Haven community is uncertain. Is “Winchester Center” poised to be a resource for the New Haven community, or will it become another luxury extension of Yale’s campus and force of gentrification?

The Science Park biotech vision took shape in 1981 with the establishment of the Science Park Development Corporation (SPDC), a non-profit organization. Created by Yale, the City of New Haven, the State of Connecticut, and the Olin Corporation, which used to own most of the industrial property in the area, the SPDC has the mission, according to its federal tax filings of completing the redevelopment of Science Park for the purpose of increasing employment in New Haven, especially the Dixwell and Newhallville neighborhoods. It also aims to deepen the city’s tax base by attracting research and technological enterprises, and to diversify housing options in and around Science Park. Tucked away in a small office stacked with papers at 5 Science Park, a lab building built in the 1990s, David Silverstone and Clio Nicolakis work as the SPDC’s only paid employees, President and Executive Director/Controller, respectively. Private developers, government stakeholders, and Yale representatives are heavily involved with the SPDC. Notably, although they are occasionally consulted, community members and local organizations do not have a seat at the SPDC’s decision-making table.

After seeking out funding and partnerships for decades, weathering the 2008 financial crisis, and reacting to the perpetually volatile demand for lab space, the SPDC has finally aligned stakeholders—including private developers, city officials—and found the financing necessary to make the next phase of development at Science Park happen.

Silverstone explained that eventually the SPDC will sell its property and dissolve, meaning that Silverstone and Nicolakis work every day toward a future in which neither of them has a job. The nonprofit structure of the SPDC is intended to be a legally and financially beneficial vehicle for the development of the area. The organization’s property holdings will eventually be turned over to private sector ownership. Once that happens, Silverstone said, “we will have done our job.”

The vast parking lots and patchwork of new and decrepit buildings in Science Park physically represent the painstakingly slow progress of the SPDC since 1981. “People speed through there, pass a bunch of parking lots, and barely know there are any lifeforms inside,” Alex Twining, the developer, said, as he defended his development plans.

Even among the ruins in the area, Yale has a palpable presence: at 33 Winchester, a massive facility housing dozens of Yale departments, including printing and publishing, facilities operations, Yale Hospitality, and library services; the Science Park Garage, currently home to Fussy Coffee, Ricky D’s Rib Shack, and thousands of square feet of unoccupied retail space; university offices in 25 Science Park; and a new a mechanical facility, a chiller plant serving Benjamin Franklin and Pauli Murray Colleges. Several of Yale’s properties in the area, including 344 Winchester, are exempt from property taxes.

By buying up retail property around campus, Yale has already fundamentally changed New Haven’s downtown. It has made pedestrian walkways and altered the city’s map to make room for new residential colleges. Similarly, the transformation of Science Park into Winchester Center centers Yale’s interests, often at the expense of the surrounding community.

The history of Science Park and the Winchester Repeating Arms factory hides in plain sight. The corner of Munson and Winchester is bookmarked by a refurbished portion of the Winchester factory, directly adjacent to the condemned portion, that was recently converted into loft apartments and high-end lab space.

“Craft Your Life,” the Winchester Lofts website instructs, as it advertises “authentic” homes “created with history, character and passion.”

A tall, rusting black fence encloses Science Park along Mansfield and Division streets. There are a few pedestrian gates along Division Street. At at least one, near a medical executive office building owned by Yale, swiping a Yale ID will grant access. The fence is a relic of the 1980s, when Science Park’s occupants feared crime from the surrounding area. Nicolakis, the SPDC’s Executive Director, showed me a photo from that era: a guard booth at Winchester and Division, flanked by curved brick walls and emblazoned with “Science Park.” A sign with red lettering hangs on the booth, assuring Alexion Pharmaceuticals shareholders that they are, in fact, in the right place for their meeting.

Today, the guard booth is gone, but the brick “Science Park” signs remain, marking a point of physical separation between Science Park and Newhallville. Twining plans to tear down the fences and extend Sheffield Avenue from Newhallville into a Science Park parking lot to physically open the development to Newhallville residents. The developers hope that the Sheffield Avenue extension will make Winchester Center’s amenities more accessible to New Haven residents—even those who will not live in the new apartment buildings.

When Science Park was established 40 years ago, Silverstone said, “Yale was trying to fashion itself like MIT or Stanford,” institutions which had robust support for student entrepreneurs. While Yale was building support for student entrepreneurship and strengthening its science efforts in general, chunks of the Yale bureaucracy moved into new Science Park facilities built by Winstanley Enterprises to support the Park’s development projects.

Lauren Zucker, Associate Vice President for New Haven Affairs and University Properties at Yale wrote in an email that “in spite of many years of effort [by SPDC], there was not enough demand for space from potential tenants.” Therefore, Yale’s move into the area was an important catalyst for development, providing a new source of traffic, energy, and potential patrons for businesses. Yale partnered with Winstanley Enterprises, another property developer, to build the Science Park Garage and the 344 Winchester facility. “All this activity,” said Zucker, “caused residential and other real estate developers to get interested in the area.” Despite the volatility of demand for life sciences space, both 4 and 5 Science Park—buildings owned and managed by the SPDC—are currently fully leased.

John Keogh, a Senior Broker at Colliers International Realty and the leasing agent for the SPDC, is well-versed in the dynamics of commercial life sciences space in New Haven. “Yale is spinning off about one company a month now,” he said. The idea is that those startups, many of them biotech, will move from Yale labs over to Science Park to get up and running. Many startups have already outgrown Science Park, including Arvinis and Alexion (now owned by AstraZeneca)—both pharmaceutical companies—and HigherOne, a fintech company founded by Yale students which was bought out after facing regulatory problems.

The continual cycle of new companies in and out of Science Park embodies the spirit of the area as a launching pad for new biotech businesses in the midst of Newhallville and Dixwell whose residents, on the other hand, value the longevity of the community.

Science Park today is already worlds away from the Winchester Repeating Arms campus that once stood tall. The development of Science Park thus far has proceeded without centering its neighbors in Newhallville and Dixwell, two New Haven neighborhoods that suffer from systemic disadvantage.

According to DataHaven, a research organization with offices in New Haven, 34% of Newhallville residents live in poverty, and 71% are considered low income. These are the highest rates in the city; 48% of New Haven residents overall are low income. Dixwell is slightly better off than Newhalville, with a poverty rate of 30% and a low-income rate of 54%. Additionally, 68% of Newhallville households are cost-burdened when it comes to housing—meaning that they spend more than 30% of their income on housing. Housing prices are increasing throughout New Haven—53% of New Haveners overall are housing cost-burdened—but Newhallville tops the list with Dixwell close behind at 57% of residents being cost-burdened.

The challenging economic conditions in Newhallville and Dixwell are not just about the cost of rent. Newhallville’s life expectancy is 71.7 and Dixwell’s is 73.2—both over 10 years lower than the 83.9 year life expectancy in Westville, one of New Haven’s wealthier neighborhoods. The numbers make clear that Newhallville and Dixwell are underserved and in need of thoughtful investment by the city to close substantial gaps.

The developers claim that investment flowing into Science Park will benefit residents of Newhallville and Dixwell. But the flow of funds, mostly from the Goldman Sachs Urban Investment Group, could materialize into something else. The City Plan Commission approved plans submitted by Twining Properties last spring to construct a 287-unit residential building over an existing parking lot, with 12,000 square-feet of ground floor retail space. Twining also plans to demolish remaining Winchester buildings on Munson Street, carve out two new perpendicular streets between Winchester Avenue and Mansfield Streets, and create a public plaza called Mason Place at the intersection of the new streets.

These new streets and the destruction of the rusting black fence are meant to open up the amenities of the future Winchester Center to current Newhallville residents. True, the new public green space will be open for all to use, but the development could lead to rising rents

on Winchester Avenue and along Munson Street. Inclusion of the surrounding community will largely be contingent on the number of housing units designated as affordable housing and the type of retail that moves into the area. If Fussy Coffee is any indication, Winchester Center could soon be home to expensive shops that are inaccessible to members of the surrounding community.

Fussy Coffee is modern and bright. Pieces of art on the walls sell for $400. And although its neighboring Science Park Garage storefronts are empty, Fussy is bustling with customers. Gabi Cheney, Fussy’s Assistant Manager, has worked at the store since it opened in 2018. When I asked Cheney if Fussy gets much business from Newhallville or Dixwell, she shook her head. “Not really.”

If people who live nearby aren’t buying Fussy Coffee, who is? Fussy’s patrons are primarily doctors, scientists, and businesspeople, Cheney said. The shop also gets quite a bit of business from residents of Winchester Lofts across the street. “When it’s slow,” she said, “it’s usually when Yale is on break.” As I left Fussy, I noticed families with young children who approached the coffee shop after parking their cars. Fussy Coffee has become a popular attraction, but not necessarily for those who have lived in the area for decades.

Crystal Gooding, chairperson of the Dixwell Community Management Team, stressed the importance of inclusive retail as Winchester Center develops. On Broadway, a retail district near Yale’s campus and owned by the Yale-affiliated Shops at Yale, “there are stores that, for the most part, residents of Dixwell and Newhallville can’t afford to shop at,” she said. “I’m hoping that the new retail will provide employment opportunities, and also that residents can afford to shop there – for me, that’s key.”

In November 2022, Twining Properties and L+M Development Partners hosted a community meeting to update neighbors on the project’s progress. It was well attended. Dinner—ribs, cornbread, and mac ‘n cheese—was catered from Ricky D’s Rib Shack, one of the few businesses currently in Science Park. It didn’t take long before community members began raising questions about fundamental components of the project.

“This is a relatively low-income community,” one community member stated. “I don’t see how your design is neighborhood friendly.” Another resident asked how the number of bedrooms in the new apartments would meet the community’s family needs. Most new apartments would have one or two bedrooms, the developers responded—configurations that are most amenable to small families or single people. Others worried about crowding in local schools as new residents move in, as well as increased traffic. Above all, concerns about access to the development’s affordable housing units—that is, units that are deed-restricted and subsidized by government programs— dominated the conversation.

Developers of the Winchester hope to provide a substantial number of affordable housing units to counteract the potential gentrifying effects of their development. Twining and Silverstone are proud that 20% of all new housing units in Winchester Center will be deed-restricted affordable units, according to the approved proposal submitted to the City Plan Commission by Twining Properties last spring. Affordable units are funded by the federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program, which provides tax benefits to developers. This is, Twining said, well above the number of affordable units required by New Haven’s new inclusionary zoning code, which was passed by the Board of Alders in early 2022. The city requires that residential developments in the area which have ten units or more set aside five percent of units

as affordable. Including substantial affordable housing in the development may help counteract gentrification.

21st Ward Alder Steven Winter (‘11), whose ward includes Science Park, emphasized the need for more affordable housing in New Haven. “We need to keep pushing,” he said.

Nevertheless, Alder Winter also expressed his constituents’ excitement about the project’s investment in public green space. Funding from an Urban Act Grant will facilitate the creation of the aforementioned plaza, Mason Place, as well as a new park at the end of Gibbs Street in Newhallville. Winter said these spaces will meet “an important need for the community.”

However, Crystal Gooding, the Dixwell Community Management Team’s chair, noted a disconnect between Science Park and Winchester Center’s continued focus on lab space and the employment needs of community members.

“It’s concerning that they’re building another lab facility without getting more input from the community,” Gooding said.

It is hard to argue that making previously unusable spaces useful is a negative force in cities, yet the problem with gentrification is the displacement it can cause. When a neighborhood becomes more attractive to a higher income group of renters, nearby landlords may raise rents. Over time, this process can price out long-time residents.

John Keogh, the SPDC’s leasing agent, believes that the new development will have a “limited” impact on the surrounding areas. “Gentrification doesn’t happen very fast,” he said.

Both Keogh and Silverstone believe that the landscape of the surrounding neighborhoods will not change. “Most of the two-, three-, four-family houses will remain,” Keogh said definitively.

Despite her concerns about the project, Gooding is supportive of development that is inclusive. “We definitely want development in Dixwell, but we also want current residents to be able to continue to afford to live there and shop there and play a part in the overall development,” she said. “As long as those three points are taken into account, I’m all for it.”

As Science Park transforms into Winchester Center and Yale’s footprint in the city grows ever larger, the developers, Yale, and the city must follow Gooding’s advice. Affordability, from housing to retail, and sustained employment opportunities are key drivers of a community’s longevity.

Elihu Rubin, a Professor of Architecture and Urban Studies at Yale, suggested that there is no definitive answer to the question of if and how development will lead to gentrification. Rubin acknowledged Yale’s “creeping presence” in Science Park, but also that Yale is New Haven’s largest employer. More Yale in Science Park could have a positive impact on job creation in the surrounding neighborhoods. While some argue that new development will cause increased rents for existing residents near the development, Rubin said, others claim that new market-rate housing is necessary to satisfy New Haven’s housing demand and stabilize existing rents. “These are two theories,” Rubin explained. “There is not necessarily one truth.”

Gooding is hopeful for the future of Dixwell and Newhallville. “We want it to be as vibrant as it once was, but we don’t want to push out the residents living here now. We want them to still be able to afford to live here, and shop here, and for their kids to go to school here, and for the seniors to be able to stay here. We want the people we have known for years and years and years to be able to stay and enjoy their lives.”

He’d always had the feeling that his mother would die for him. It still came as a surprise when she actually did—a foot in the dark expecting one more step. Now he was alive and she wasn’t. That had never been true before. He vomited three times on the way to the hospital. They checked for concussion but all was clear.

Claire didn’t know him. She never really would. Usually she wouldn’t answer an unknown call, but it was a slow day in the office and any distraction was something. The paramedic on the other end of the line told her the facts and she said she’d be right there. Wrong numbers rarely offered the chance to be a hero, or to clock out early.

It took 28 minutes to reach the ward, and in that time the boy had fallen asleep. He was older than she’d expected—at least fifteen. She could still remember being fifteen with the sort of discomfort that meant she hadn’t quite recovered. But a boy was a boy and she’d answered the call, so she sat by his bed and thought of comforting things to say. She looked at his hands, palms red with the crescent moons of fingernail marks, and placed one of hers on top. He woke in the morning. She said what she’d prepared.

“What do you need?”

“Nothing.”

Claire had no reply to that. They sat in unquestioning silence. When the forms were signed for his release she offered again to help. He refused and they parted, each to their own lives.

It was too late for hospice. The paramedic’s disembodied voice hung somewhere between bored and judgemental as she described the 89-year-old woman’s solitary suffering. It had been days. Not just hours. Days alone in the pit of her shower, living off the water that dripped from the faucet. Days that would be her last, or almost her last. She had a few hours left, at least, and Claire might like to say her goodbyes.

Two absences from work in less than a month would hardly be treated kindly. The job was still boring, though, and perhaps this time she would be needed. Any surprise she felt at this second wrong number was quelled by some sense that she was, at least, prepared. She made it to the hospital in just 24 minutes. It was a different ward and a different patient, but the same white walls and white smell and background noise of panic. Already the routine felt familiar, the first sketches of a habit.

She found the woman laughing. To make matters worse it was in response to nothing more than a weather report on the outdated TV. The patient in the bed was shrunken and looked, Claire thought, like a mildewed drowning victim who hadn’t yet bloated. The ocean-green of the covers bunched around her seemed to tint her thin hair. Her lips opened and closed like breathing learned from a manual. This was the sort of old age that was fought for and came at a cost.

“You aren’t dying.” Claire tried to regret her words. The woman coughed out another laugh.

“Like hell I’m not. Just give it time.”

Claire didn’t have time. Not if she wanted to get paid. Still, she wasn’t the one in the bed. She breathed, willing herself to be the calm one—the caring one.

“What do you need?”

“Oh, nothing. Unless you think you could swipe some juice from the nurses’ lounge—I’ve heard they have pineapple. Us poor wretches in the hospital beds get saddled with orange.”

“I’ll see what I can do.” Claire turned, choosing not to wonder how this woman could know about some secret pineapple stash. She was alive, at least, and well enough to come up with busy work. Claire knew she should feel glad. Instead, all she could think was that the paramedic had a vindictive streak and she could have stayed at work after all.

Noise was almost always a good thing. A patient bawling in the background of a call meant that they had lungs and minds intact enough to scream. That didn’t make it any less annoying.

The man in front of her had a convincingly stupid goatee. It made it easy to imagine the sort of situation that would cause him to be stabbed in the upper thigh with a fork. His well-tailored suit was ruined, but nothing else seemed to be.

“What do you need?” She asked. The man looked up in surprise, then assessment. His blotchy skin blotched more.

“You could lend a hand pulling this out, if it won’t make you vom all over me.” He gestured down to his leg. There was blood on the hospital sheet, but not much.

“I could, but I’m not a nurse. The fork could be stemming an artery, I shouldn’t risk letting you bleed out.” She imagined doing just that—imagined watching his smirk drip off his face like sweat. Either her fantasies weren’t visible in her expression, or he wasn’t looking. Now granted an audience, he seemed to have forgotten his previous performance of pain.

“Weren’t doing anything else, I hope?” He asked, flashing what he no doubt called his ‘winning smile’.

“No,” Claire ground out, lying.

“Good good. Fancy getting a new nurse, then? This lot are hardly the attentive sort.”

Claire spun on the heels of her smartest, most uncomfortable shoes—the ones she always wore for important meetings. It had been a last chance, a token of trust. She hadn’t deserved it. Behind her the man pulled the fork from his leg. Blood fountained and nurses were there in a beat.

“Zara?”

This patient seemed determined to mistake her for someone else. It was the only word he’d managed since she’d arrived at his bedside. A dreary hospital pamphlet with a picture of a dreary blue balloon in a dreary blue sky had told her that his rasping was the result of fluid buildup in the throat and upper airways. Towards the end a dying person loses the ability to swallow or cough. The excess saliva then begins to block airflow, some mix between drowning and suffocation.

“I’m not Zara. I’m Claire. I’m here to help. Would you like me to look for Zara?”

The man tried and failed to reply. Claire thought he would likely die soon. She adjusted the morphine the way she had seen the nurses do and hoped it would be enough. Nothing much happened. The day stretched on. Horror shifted to boredom. She looked at the clock and tried to calculate how much longer propriety demanded. Her landlord and credit cards didn’t care much about propriety, and temp-agencies didn’t compensate sick days.

He moaned when she left, but it could have just been a rasp. It didn’t matter much, he couldn’t even get her name right.

Claire waited two hours for the 60-something-year-old heart attack victim to show up. She forgot to check the morgue. The only saving grace of the experience was that she successfully evaded the landlord who had decided to bring the rent notice to her apartment in person.

When she was fourteen, Claire had spent all of ten minutes thinking she was a murderer. She hadn’t checked the box’s ingredients list for allergens and hadn’t known her brother could be saved. Whether the man in front of her would live seemed as uncertain as she had been in the kitchen that day—too frozen even to call for help. Now, she knew better. She held his swollen hand and counted his breaths, waiting for the medicine to either take effect or fail.

He eventually woke with the groan of a hangover and not a hint of surprise. He’d found himself here before.

“How can I help?”

“What?”

“How can I help? What is it you need?”

“Well, let me think,” he paused to rasp, “maybe a cashew?”

Claire paused, recalling his notes. She scowled.

“That’s what you did?”

“They taste good!”

“Enough to—fine. How are you even alive?”

“Beats me.”

Claire waited, then gave in to curiosity, asking “Was it worth it?”

“I never want it said that I turned down any worldly experience. No one can say I didn’t give it a go.”

“Give what a go?”

“Life.”

Claire paused again, considering. This time it was the man who spoke.

“I’ll be discharged soon, I expect. You can go if you want.”

Claire thought of where else she could be. She came to a blank.

“It’s fine. You might find another cashew if I leave.”

Claire readjusted in her seat, checked her pocket for her phone. She wouldn’t want to miss it if it rang.

Yale students—desperate for relief from mental health issues—are turning to the University’s psychiatric services, where they are met with reckless prescriptions and inattentive care.

David ‘19 (pseudonym) was a college junior when his friends encouraged him to seek professional help during a severe depressive episode.

After an initial psychiatric consultation, David was immediately sent to Yale-New Haven Hospital. This was his very first interaction with mental healthcare.

Three days later, he was released from the hospital with the expectation that he would enter longer-term, out-patient care—such as therapy—through Yale Health. Instead, David spent weeks on the waitlist for a talk with a therapist he ultimately never received. He was told his situation was “not that urgent,” he recalled.

David was, however, assigned to a psychiatrist.

He had long suspected that he had bipolar II disorder, a condition characterized by oscillations between hypomania and severe depression. His psychiatrist agreed. “That was basically the extent of the real service [he] gave me,” David said, chuckling.

His psychiatrist recommended he take Lamictal, a popular medication used to treat bipolar disorders, but he warned David about one potential side effect: a “deadly skin rash” called Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Worried, David asked his psychiatrist if there were any genetic predispositions that might put him at greater risk.

“He would just Google these questions in front of me. I kid you not, he would literally go on WedMd,” David remembered.

His psychiatrist suggested a genetic test to allay David’s fears. At their next appointment two weeks later, when David brought up the medication, his psychiatrist suggested the genetic test again, as if their last appointment never happened. Two weeks later, the same conversation, yet again. The test was never ordered by the psychiatrist.

For more than a month, David’s bipolar disorder—a condition which, when untreated, dramatically increases the risk of suicide—was left unaddressed and unaided by either talk therapy or medication.

And when David’s psychiatrist finally prescribed him medication, his symptoms only worsened.

A growing number of American college students use psychotropic drugs—drugs that affect the brain’s chemical activity. This group of drugs includes mood stabilizers, antidepressants, and anti-anxiety medication, which are common interventions for mental health issues. Between 2007 and 2018, there was a nationwide increase in the use of nearly every class of psychiatric medication, with the rate of antidepressant use increasing from 8.0% to 15.3%. According to Paul Hoffman, Director of Yale Mental Health and Counseling (MHC), approximately one third of all students who sought treatment through MHC requested to meet with a psychiatrist, roughly 11-12% of the Yale University student body. It remains unclear how many students are actually prescribed psychotropic drugs through Yale Health. Yale Health’s Director of Pharmacy, Bryan Cretella, did not respond to request for comment.

In recent years, Yale Health has been criticized for failing to meet student demand for counseling and therapeutic services, leaving students like David on long waitlists. If they do manage to get off these waitlists, students are often given short and sporadic appointments. The problem is mostly insufficient staffing. With just over 50 employed clinicians and 5,000 students seeking treatment, each therapist would have to see almost 100 students in order to meet current demand—a workload that rules out effective or quality care.

In sharp contrast to the long waits for therapeutic counseling, Yale Health’s psychiatric services move eerily quickly. A survey of 175 students conducted in November 2022 reported that over 60% of Yale students “somewhat agree” or “agree” that it was “easy for [them] to receive a prescription for psychotropic drugs.”

When asked what compelled him to seek psychiatric medication, Michael ‘20 (pseudonym) cited limited access to therapy as one of the reasons. “Spots are so limited, and time is so limited because so many students are ill. I just [felt] like I needed an additional supplement,” Michael said.

Pressure on Yale’s Mental Health and Counseling services reached a peak in late November when two current students and the mental health advocacy group “Elis for Rachael”— formed after the 2021 suicide of Rachael Shaw-Rosenbaum ‘24—filed a lawsuit against the University, claiming discrimination against students with mental health disabilities. While Yale remains in settlement negotiations, the University announced dramatic changes to its medical leave of absence policy in January. Among the changes was a simplification of the reinstatement process for students on mental health leave.

Still unnoticed, however, are the thousands of struggling Yale students driven to psychiatry by a desperate desire to

feel better—to feel happy—only to be met with little support or care from their providers. Students are prescribed serious medications, only to then be inadequately listened to and improperly monitored. Students like David, who need medication for their own safety, but struggle to feel safe under Yale Health’s care.

Robbie ‘22 (pseudonym), was first assigned a psychiatrist during their sophomore year. They struggled to figure out how to pair this psychiatric treatment with talk therapy. “Ghosted” by the first therapist they were assigned by Yale, they saw another licensed social worker on an “emergency basis,” Robbie recalled. After their first meeting with a psychiatrist, Robbie received a prescription for Lexapro, an antidepressant.

This, however, runs counter to what many psychiatrists consider to be best practice. Dr. Yann Poncin, assistant professor of clinical child psychiatry at Yale School of Medicine, argues that—although there are exceptions—a young patient should only consider pursuing psychiatric medication “[if a] good two, three months of quality therapy is not leading to change.” Though medications can be effective without therapy, Yann argues, there are often issues driving symptoms that are worth exploring first.

Many Yale students would consider themselves lucky to see a therapist for two to three months. For students like Robbie and David, psychiatry became an inadequate substitute for psychotherapy. Robbie’s psychiatrist doubled as an “awful” therapist, they recalled, who would “start meetings late, end them early, [and] open a can of worms.”

David never received a therapist, even while coping with his bipolar diagnosis. “It’s critical to see how far therapy can go before medication comes into play… even just dealing with the side effects of medication requires help,” he remarked. “That’s a journey in itself.”

For students like Claire ‘22 (pseudonym), who are fortunate enough to receive both a psychiatrist and a therapist, the two

professionals often fail to work hand-in-hand, to the detriment of the patient. “Frankly, [it] seemed like my psychiatrist and my therapist weren’t in conversation with each other at all, at any point,” Claire recounted.

Research shows that collaboration among healthcare providers can improve patient outcomes and prevent adverse drug reactions. Some experts believe it is, in fact, essential. Dr. Linda Drozdowicz, a specialist in child and adolescent psychiatry at Yale-New Haven Hospital, said that collaboration “is something that all mental health professionals should strive to do, since not communicating well can lead to suboptimal care.”

In addition to reporting uninformed and disjointed treatment, some Yale students—such as Sasha Carney ‘23—felt that their providers were apathetic and uninvested. “He was very detached and removed. When he… tried to get me to talk about my feelings, I got the impression that he really did not want to care about them, and I felt no desire or comfort with sharing,” Sasha said of their first-year psychiatrist. “I would often miss my medication or fall behind on my medication because I hated spending time with him, I hated setting appointments with him.”

This sentiment between patient and mental health care provider can have disastrous consequences. The Family Institute at Northwestern University reported that patients who rate their relationship with their provider poorly are more likely to drop out of treatment.

Other students felt that their psychiatrists almost dehumanized them. “Yale psychiatry and medication in general was reductive and not too holistic and healthy in viewing me as a person. They kind of view you as a little chemistry equation,” Michael said.

Students, like Anna ‘24 (pseudonym), experienced suspicion and distrust from their psychiatrists, which prevented them from being transparent about their symptoms. “When I was trying to get accommodations for my classes, my psychiatrist told me that he wasn’t able to do that…because we could be lying about our symptoms. These were the same symptoms he was prescribing me medication for,” she said. “It was jarring to hear that I could get all these drugs from him, but I couldn’t get medical accommodations for my classes.”

Jaclyn Recktenwald, Program Coordinator of Student Wellness at the University of Pennsylvania, believes these concerns highlight a failure of one of the fundamentals of student psychiatry. “For folks to feel seen and heard, they have to feel like the person they are talking to respects them—trusts that their pain is real,” Recktenwald said.

When psychiatrists fail to listen to their patients, they place lives in danger. In the fall of their sophomore year, after experiencing a traumatic incident during a summer abroad, Robbie’s psychiatrist suggested Lexapro to address severe panic

attacks. Almost immediately, Robbie began to feel unsettling symptoms. “I was struggling to swallow, and my tongue was swollen. I thought I was going crazy, but as I kept taking it more and more, it kept happening…and those symptoms were in addition to the rampant anxiety I was feeling from the meds,” Robbie recalled. Robbie’s psychiatrist refused to listen to them, dismissing their concerns and claiming that the medication just “wasn’t at a therapeutic dose.” With no support from their provider, Robbie’s anxiety continued to worsen. Soon after, they ended up in the hospital.

Given his concerns about Lamictal’s potential side effects, David’s psychiatrist instead prescribed him Abilify in the spring of 2018. “That really messed me up,” David confessed. “It made it impossible for me to move my body.” Unable to function over his spring break, David called Yale Health, seeking approval to stop Abilify. He struggled to get a hold of a professional, in large part because his psychiatrist was only in-office three days a week. Eventually, after repeated attempts, the on-call psychiatrist authorized David to get off Abilify.

“The moment I got off, I was just unbelievably unstable. I was having the worst manias, the worst depressions of my life. I was in real danger,” he said. The on-call psychiatrist failed to tell David’s psychiatrist that he had been taken off Abilify, so David suffered through the effects of what he believes was withdrawal without an alternative medication.

Eventually, David’s psychiatrist prescribed him the antipsychotic Seroquel to address his paranoia. “The psychiatrist I saw later, after I went home, said that [Seroquel] was probably one of the worst possible medications he could’ve given me,” David recalls. “I was very unstable and the Seroquel probably made it worse,” David said, likely because it exacerbated his anxiety. As his condition worsened on Seroquel and psychotic symptoms emerged, David knew he had to be hospitalized, but was afraid to tell anyone—even his psychiatrist. He finally made the decision to withdraw from Yale.

Because of attention issues during ‘zoom-school’ her junior year at Yale, Claire ‘22 (pseudonym) reached out to her high school therapist, whom she had previously spoken with about her attention difficulties. Hoping to obtain medication to help her focus through Yale Health, Claire asked her former therapist to write her a letter confirming she had ADHD symptoms.

The letter was enough to get Claire a prescription for Adderall, which derailed her mental health completely. “There would be days where I just wouldn’t eat at all. And I was also having a ton of difficulty sleeping…sometimes I would go multiple days with

a total of about six hours of sleep,” she said. “I would be taking two or three shots [of alcohol] a night in order to sleep.”

Claire’s worsening symptoms eventually brought her to YaleNew Haven Hospital, where she was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. “They thought that a lot of the mental health crisis I was in was because I was being completely incorrectly medicated,” she remembers.

A private psychiatrist later told Claire that being placed on a stimulant like Adderall with bipolar disorder is very dangerous—which is why stimulants should never be prescribed without a psychiatric evaluation.“[A letter] doesn’t count,” Claire recalled her psychiatrist saying.

When asked to comment on Claire’s story, Dr. Victor Schwartz, Senior Associate Dean for Wellness and Student Life at CUNY School of Medicine and former chief psychiatrist at the NYU Student Counseling Service, wrote in a March 8th email that, while a new psychiatrist might feel comfortable relying on a patient’s history to continue a treatment, they should “still meet the student and do their own assessment.” The only exception, he continued, is if a patient has been prescribed a particular medication for a long time and is running out. But this was Claire’s first time on Adderall.

These dangerous errors and lack of standardized procedure may arise from the very structure of Yale’s student psychiatric services: providers are often residents—recent graduates of medical school— who are still in training. Dr. Schwartz wrote in a December 3rd email that “residents are trainees, so by definition less experienced, but often, they have more time to do in-depth assessments too.”

According to Paul Hoffman, Director of Yale Mental Health and Counseling, the program has 12 psychiatrists on staff and 5 advanced psychiatry residents. “MHC sees training the next generation of psychiatrists as vital to its core mission of helping our students,” he wrote in a March 10th email.

For Michael, however, the problem lies not in experience, but in residents’ shorter tenures and, thus, higher turnover. “[O] ver three years—my sophomore year to my senior year—I had four different psychiatrists,” Michael remarked. “With every replacement of a psychiatrist, you would sort of start over with this person and build a relationship.”

Paul Hoffman upholds that Yale’s psychiatrists undergo “weekly clinical supervision, clinical rounds, and clinical teams.” This brings into question, then, how David or Claire faced life-threatening emergencies due to errors their providers made—errors private psychiatrists could recognize immediately.

With SSRIs—selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, the most common class of antidepressant—the most precarious time for a patient is the first few weeks on the drug, also referred to as the initiation period. While antidepressants are associated with having a protective effect on suicide attempts overall, in younger people there can be an increased risk of suicidal thoughts or behaviors during initiation of the medication. Because of this risk, Dr. Drozdowicz says, “the standard of care is to check in…in some way at least weekly for the first month,” when adolescents and young adults are first prescribed SSRIs. But when Michael ‘20 was first prescribed Prozac in 2017—after a brief, 30-minute appointment—their Yale Health psychiatrist only checked in with them a month later. At that appointment, when Michael expressed that their symptoms had not improved, their psychiatrist upped the Prozac dose and added Wellbutrin. “From there, it just kept… incrementing upwards,” Michael recalled.

Dr. Schwartz considers this “incrementing” a common problem within psychiatry. “With SSRIs specifically… the therapeutic effects take a while to happen and there is a tendency to try and push the dose up in order to get it working. The problem with that is it can actually increase the risk of side effects as well,” he explained.

The incrementation Michael underwent made them feel emotionally blunted—flat. “I could actually wake up and go do things… but I’m not like ‘happy.’ I’m not, like, excited to wake up but I can exist, I can function,” they described. Michael conveyed these emotions to their psychiatrist, who dismissed them. “Apparently that was enough of a justification to keep upping the dosages basically… as long as I was a working subject within the university, I guess it was fine,” they recalled.

While hasty dosing can cause unnerving side-effects like emotional blunting, abruptly stopping antidepressant medication can make a student’s condition even worse. “Some medications I describe as… like wearing glasses. You can put them on, put them off—you see or don’t see,” Dr. Poncin explained. “Other medications [are] in your system to make changes, more like muscle building and to come off of them, you have to go more slowly.” Antidepressant withdrawal may lead to “Antidepressant Discontinuation Syndrome,” which causes flu-like symptoms, according to the American Academy of Family Physicians. Worse, withdrawal can cause a relapse—or even an escalation—of depression.

For some students, these dangerous withdrawal effects were not their doing—but the University’s. When Anna withdrew from Yale in 2019 on a medical leave to address her mental

health, she lost the insurance coverage that helped her pay for her psychiatric medication and the provider who prescribed it. At that time, students who withdrew were prohibited from enrolling in any affiliated healthcare. “I called [my psychiatrist], and I said, ‘I think I’m going to withdraw’ and he basically said ‘Yeah I think that’s a good idea.’ It was literally a two minute phone call. There was no discussion of how I was going to continue my medication or how I was going to phase them out,” Anna said. Without a new provider, Anna had to stop her medication.

“I noticed pretty immediately that I was having some sort of withdrawal… and a friend [said] ‘Yeah you’re not supposed to just stop Prozac’... and I was like ‘Oh, nobody told me about that,’” she explained. Her symptoms were severe. “It was a lot of suicidal ideation… very very different from how I’d experienced that kind of suicidal ideation in the past,” Anna described.