Africa is stepping into the global spotlight as a continent of solutions, not just challenges. Across its diverse regions, breakthroughs in renewable energy and grassroots innovation are redefining what is possible for development, resilience, and sustainability. From rural villages where inventors are building homemade generators to billion-dollar initiatives backed by global institutions, the story of Africa’s energy revolution is one of creativity, urgency, and unstoppable momentum. The world’s fastest-growing population and one of its largest energy access gaps are colliding with falling technology costs, rising investment, and a new generation of innovators who refuse to wait for traditional infrastructure. Africa is not only catching up to global energy standards—it is setting new benchmarks. The projects highlighted in this issue showcase how African talent, resources, and vision are lighting the path toward a cleaner, more inclusive energy future.

Power from Air – Malawi

An 18-year-old school dropout, Ernest Andrew, has stunned the world by building an air-powered generator from recycled parts, lighting homes in his village without fuel, batteries, or oil. His device, assembled from bicycle components, bottles, and magnets, has given families light and power for the first time, proving that innovation can flourish even without access to formal education or expensive laboratories.

Solar Minigrid in Goma – DRC

In the conflict-affected city of Goma, the company Nuru has built a 1.3-megawatt solar minigrid that delivers reliable electricity to thousands of homes and businesses. Unlike fragile diesel generators that dominate in the region, the system uses solar panels and battery storage to provide stable power even during periods of instability.

Solar Boom from Chinese Imports – Africa-wide

Africa imported a record 1.5 gigawatts of Chinese solar panels in 2025, dramatically reducing costs and accelerating the spread of renewable energy. With Chinese manufacturers driving global prices down, African governments and private developers have been able to deploy solar projects faster and at a scale unimaginable just a decade ago.

Mission 300 Electrification – Africa-wide

Mission 300, a six-billion-dollar initiative backed by development banks, aims to connect 300 million Africans to electricity by 2030. The program blends grid expansion with decentralized solutions like mini-grids and solar home systems, recognizing that universal access requires multiple strategies working in tandem.

Electricity from Plants – Congo

Congolese inventor Vital Nzaka has pioneered a bold experiment: generating electricity directly from plants and soil. By capturing electrons released during natural microbial processes, his system demonstrates that vegetation itself can become a source of renewable power for rural communities.

Pay-As-You-Go Solar – Kenya

Kenya has become a global leader in off-grid solar, thanks to payas-you-go systems that allow families to purchase solar kits through small mobile money payments. Companies like M-KOPA and d.light have provided millions of households with affordable, clean energy, replacing kerosene lamps and candles.

Ampli Energy Renewable Platform – South Africa

South Africa’s energy crisis, marked by rolling blackouts and overreliance on coal, has spurred innovation in corporate renewable supply. Ampli Energy, a platform backed by Discovery and Sasol, allows companies to access clean power on a flexible month-to-month basis, with cashback incentives for participation.

The Oya Hybrid Power Station combines solar, wind, and battery storage to provide dispatchable, on-demand renewable power. Located in the Western and Northern Cape regions, the project is designed to add reliable capacity to South Africa’s grid, addressing the intermittency challenge that has long been cited as a weakness of renewables.

The Green Giant Solar Project aims to add up to 1,000 megawatts of clean power in the Democratic Republic of Congo, beginning with an initial 200-megawatt phase. As one of the largest solar undertakings in Central Africa, it represents a monumental step toward diversifying the country’s energy mix.

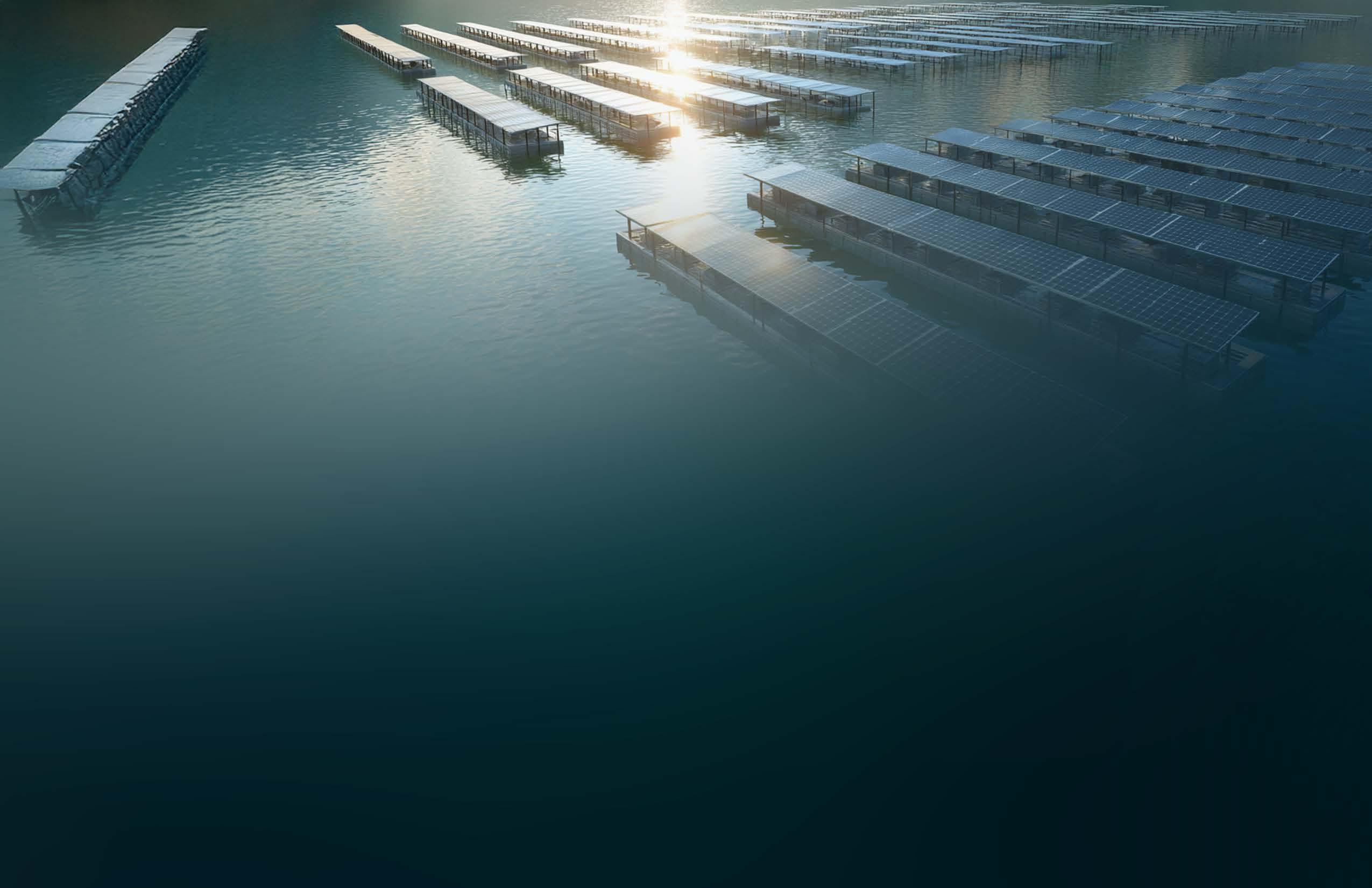

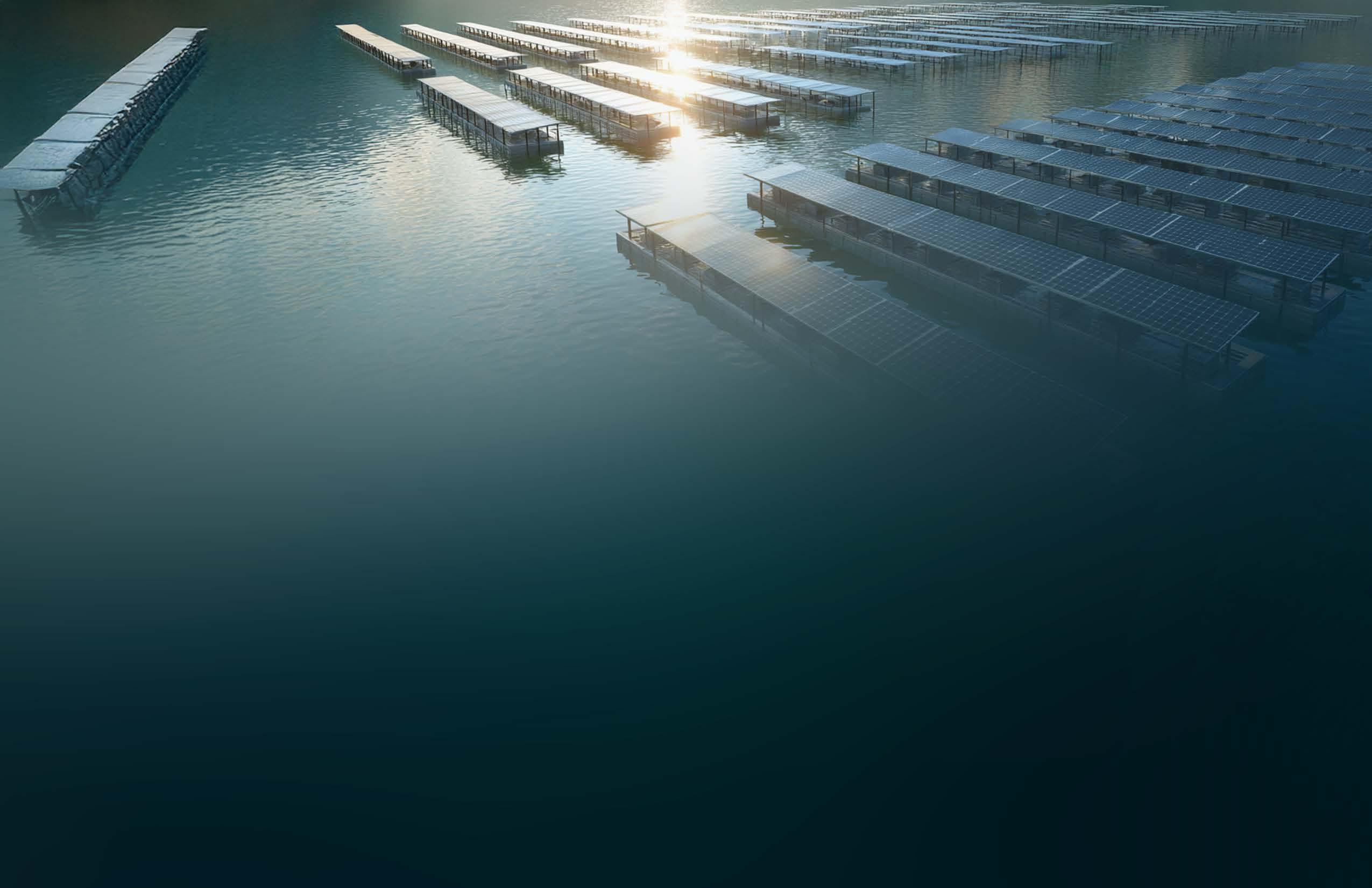

Kenya’s KenGen is developing a 42.5-megawatt floating solar farm on the surface of the Kamburu hydropower reservoir, making it one of East Africa’s first large-scale floating solar projects. By placing panels on water instead of land, the project maximizes space while tapping into synergies with existing hydro infrastructure.

“Influential Magazines, driven by its unwavering aim and mission, strives to be a catalyst for global business transformation. Our commitment extends beyond the conventional, as we envision Unlocking vast business potential in emerging economies. This endeavor creates an unparalleled opportunity for worldwide expansion and knowledge exchange. The emerging nations, marked by dynamic markets and untapped resources, beckon entrepreneurs, investors, and enterprises globally to partake in mutually beneficial ventures. Influential Magazines serves as the conduit for this transformative journey, shedding light on the visionary growth strategies, infrastructure development, and burgeoning consumer bases within the emerging nations. As these economies evolve and innovate, our mission is to foster international collaboration, creating a vibrant space where industries thrive, and insights are shared. Embracing the business potential in these emerging economies not only unlocks doors for unprecedented growth but also nurtures a global dialogue, enriching our collective understanding of diverse business landscapes and strategies. The emerging nations, through Influential Magazines, transcend being mere destinations for business, they also become dynamic hubs for cross-cultural learning and collaboration."

In the quiet village of Chinguwo in Malawi’s Dowa District, an extraordinary story is unfolding. A young man named Ernest Andrew, who dropped out of school in Form Two, has built an invention that is changing lives in his community. Using little more than recycled materials and an insatiable curiosity, Ernest constructed an air-powered generator capable of producing electricity without fuel, batteries, or oil. His prototype, which incorporates bicycle parts, magnets, old transformer components, and plastic bottles, reportedly generates enough power to light up multiple homes and even a primary school. For villagers who once relied on candles or kerosene lamps, this device has meant a profound shift in daily life. Radios now play in the evenings, children can read after sunset, and households experience conveniences long taken for granted elsewhere.

Ernest’s motivation was simple: to address the hardship of living without power. Though he lacked formal engineering training, he tapped into intuition, persistence, and creativity. What emerged was an invention that

many residents initially doubted, only to later embrace after seeing its effects first-hand. His generator has not only illuminated homes but has also sparked a sense of pride in what local innovation can achieve.

At the core of Ernest’s device lies a process he describes as converting air currents into usable electricity with “magnetic power stored in bottles.” While this explanation remains scientifically unconventional and has drawn skepticism from technical experts, the visible results cannot be denied. Villagers report functioning lights and working appliances connected to his generator. What stands out is not just the technical novelty but the ingenuity behind it. With no laboratory and no advanced tools, Ernest relied on discarded scrap, trial and error, and a determination to solve a problem affecting his entire community.

This is not the first time Malawians have made headlines for grassroots innovation. Years earlier, William Kamkwamba’s homemade windmill gained global recognition for powering his village. Ernest’s generator carries

forward this spirit of resourcefulness, proving that transformative ideas can emerge even where resources are scarce. These stories challenge assumptions about where innovation originates and underscore the importance of empowering local problem solvers.

Support from Government and Institutions

The impact of Ernest’s generator has drawn attention beyond his village. Malawi’s National Council for Science and Technology has stepped in to offer mentorship, training, and safety improvements for his invention. Government officials have praised his creativity, pointing to its potential as a cost-effective and sustainable energy solution for rural communities. Some leaders have suggested helping him secure intellectual property protection so that his work can be formally recognized and scaled. Community leaders too are urging him to expand the reach of his device, envisioning a time when more households, schools, and clinics could be powered by his innovation.

Such recognition is critical. Too often, grassroots inventors remain unsupported, their ideas fading for lack of resources. In Ernest’s case, the encouragement and backing of institutions may provide the foundation he needs to refine his prototype, test it rigorously, and potentially transform it into a scalable technology.

The story of Ernest Andrew is more than a tale of one boy’s invention. It is symbolic of a larger trend across Africa: the rise of community-based innovators solving problems with limited means but unlimited determination. In countries where large portions of rural populations remain off the electricity grid, such solutions carry enormous value. They prove that innovation does not always need hightech labs or multi-million-dollar budgets. Sometimes, it springs from necessity, creativity, and the willingness to experiment.

This grassroots ingenuity points to the potential of Africa as a frontier for technological breakthroughs that are both affordable and sustainable. From bio-robotic prosthetics built from ewaste in Kenya to plant-based electricity experiments in Congo, there is mounting evidence that innovation is thriving on the continent. Ernest’s generator is part of this renaissance, highlighting how localized solutions can address global challenges like energy poverty.

The significance of Ernest’s generator is not just technological but also financial. For investors, philanthropists,

and development organizations, his story illustrates why supporting grassroots innovation can generate meaningful impact.

One key opportunity lies in providing seed funding and micro-grants. For inventors working in rural areas, even modest financial support can make a transformative difference. Small investments allow innovators to purchase safer materials, refine prototypes, and expand their reach. Development funds could be structured to specifically identify and support such individuals, offering both capital and mentorship.

Another investment pathway is the creation of incubators tailored to local conditions. Conventional tech hubs often cater to university-trained entrepreneurs in urban areas. By contrast, rural innovators like Ernest operate outside traditional systems. Mobile or hybrid incubators that provide access to tools, training, and engineering expertise could bridge this gap. Investors who support such initiatives would not only nurture talent but also open pathways for scalable businesses rooted in real community needs.

Crowdfunding and global mentorship also represent viable avenues. Stories like Ernest’s resonate widely, and platforms that allow people around the world to contribute small amounts could fuel development while raising awareness. Pairing these campaigns with mentorship programs involving engineers, scientists, and business experts would accelerate progress and ensure inventions meet safety and efficiency standards.

Finally, there is the critical question of intellectual property. Many local inventors do not know how to protect their ideas, leaving them vulnerable to exploitation. Establishing legal aid

services for inventors could help secure patents and negotiate fair licensing agreements. For investors, this means opportunities to partner with innovators on equitable terms while ensuring they benefit from commercialization.

The Bigger Picture: From Villages to a

What Ernest Andrew has achieved in his village is both inspiring and instructive. By creating a generator that harnesses air and magnets to produce electricity, he has delivered immediate relief to families living in darkness. But the implications stretch further. His story demonstrates the untapped potential of grassroots inventors to contribute solutions to some of humanity’s most pressing challenges.

Africa’s innovation narrative is often overshadowed by global technology centers. Yet stories like Ernest’s reveal that the continent is not just catching up—it is pioneering its own path, rooted in local realities and creative resilience. As investors, governments, and institutions take notice, the possibility emerges of scaling these innovations from villages to entire regions. Supporting inventors like Ernest is not charity; it is a strategic investment in sustainable solutions with global relevance.

In a world striving for affordable, renewable, and accessible energy, a young man from rural Malawi has shown that answers may come from unexpected places. His journey reminds us that brilliance knows no borders and that the next wave of transformative technology could very well be born in the most unlikely of workshops.

A new kind of utility in a city shaped by crisis

On the western edge of Lake Kivu, the city of Goma in the Democratic Republic of Congo has become an unexpected pioneer in Africa’s energy transition. A private solar minigrid built and operated by the Congolese company Nuru has been quietly transforming daily life. The system, which began operating in 2020, delivers reliable electricity to homes, small businesses, and vital services in a city that has long suffered from unreliable power and conflict-driven instability.

This 1.3-megawatt facility has proved to be more than a technical project. It has provided a lifeline to families who once relied on costly, polluting diesel generators. Even during times of insecurity, when parts of the city have been disrupted, the minigrid has continued operating as a beacon of resilience. Streetlights now shine in neighborhoods that were once pitch dark, giving residents a sense of safety. Local shopkeepers keep their doors open later, welders and carpenters work longer hours, and children are able to study at night.

The symbolism of this achievement is powerful. In a country where only about one in five people have access to

electricity, any model that can deliver reliable power today, not decades into the future, carries enormous importance.

The Goma minigrid is based on a straightforward but transformative concept: generate electricity locally, store it, and distribute it through a neighborhood-scale network. Nuru’s “metro-grid” consists of thousands of solar panels spread over a few hectares of land, paired with battery storage that ensures electricity is available even after sunset. When needed, small diesel units can provide backup, but the system is primarily solar and storagedriven. The setup functions as a selfcontained utility. Households and businesses are connected through local distribution lines and pay for electricity via prepaid and postpaid systems. This ensures a revenue stream that supports operations and encourages responsible energy use. To increase resilience, Nuru has also interconnected its solar site with nearby hydropower infrastructure, creating a hybrid model that reduces risks associated with relying on one source alone.

For years, diesel was the default power solution across off-grid African cities.

It was relatively easy to deploy but came with punishing costs. Families in Goma once spent more on diesel each day than they now pay for solar power from the minigrid. Diesel fumes, constant breakdowns, and the unpredictability of supply were part of daily life. With the minigrid, customers enjoy a cleaner and more reliable alternative.

The economic benefits are visible on the streets. Night markets operate into the evening, cinemas can schedule shows after dark, and restaurants keep refrigerators running without fear of sudden blackouts. The health benefits of reducing diesel fumes add another layer of value, particularly in densely populated neighborhoods. Perhaps most striking is the sense of safety created by new solar-powered streetlights. Residents note that crime has declined in lit areas, with evening life now safer and more vibrant.

Projects like Goma’s require creative financing structures to succeed. The initial investment came from a mix of development finance institutions, philanthropic climate funds, and private backers willing to take risks in fragile environments. To diversify revenues, Nuru also pioneered the sale of Peace

Streetlights now shine in neighborhoods that were once pitch dark, giving residents a sense of safety. Local shopkeepers keep their doors open later, welders and carpenters work longer hours, and children are able to study at night.

Renewable Energy Credits, or P-RECs. These are premium renewable energy certificates that include verifiable social benefits. Buyers, including global corporations, purchase them at a premium, knowing their funds support projects in conflict-affected regions. Early P-REC revenues financed dozens of streetlights in the Ndosho neighborhood, a visible sign of impact that residents quickly embraced.

On top of innovative revenue streams, Nuru secured results-based financing from international programs dedicated to off-grid power. These arrangements pay developers for every new household or business connected, ensuring that the company is rewarded not just for building infrastructure but for delivering measurable outcomes. Such mechanisms de-risk projects for investors and bring in co-financing that would otherwise be difficult to access in volatile markets like eastern Congo.

The Democratic Republic of Congo liberalized its electricity sector in 2014, creating a legal pathway for private companies to generate and distribute power. While challenges remain with licensing, tariff approvals, and currency volatility, the reforms marked a turning point. Without them, projects like the Goma minigrid would have been impossible.

The urgency is clear. With roughly 80 percent of the population still lacking electricity, the DRC has one of the world’s largest access gaps. Expanding the national grid is slow and prohibitively expensive in many regions. For secondary cities and urban peripheries, decentralized minigrids are often the least-cost solution. By pairing solar with storage and, in some cases, small-scale hydro, developers can deliver power faster than large infrastructure projects that may take decades to complete.

Electricity is the invisible backbone of development. In Goma, reliable power has improved water pumping and treatment, stabilized internet and mobile services, and made it possible for small manufacturers to justify investing in new machinery. Schools can plan evening classes, and clinics have reliable refrigeration for vaccines and medicines. Families that once struggled with candles and kerosene lamps now enjoy brighter, safer homes.

Community involvement has been another unexpected success factor. When instability threatened the area, residents themselves helped protect the facility from looting or vandalism. That sense of ownership reflects the project’s visibility and direct benefits. People are more willing to defend infrastructure that they see improving their lives daily.

Investing in energy projects in eastern Congo comes with undeniable risks. Armed conflict has at times damaged infrastructure, including unexploded ordnance that once hit panels at the Goma site. Currency depreciation can erode returns if tariffs are not adjusted, and inflation adds pressure to household affordability. Construction timelines often stretch due to security incidents or supply chain disruptions.

However, developers like Nuru are building a playbook for managing these risks. Diversifying generation sources, such as interconnecting solar with hydropower, improves resilience. Community engagement helps protect sites during instability. Insurance products, though costly, can cover political risk, currency inconvertibility, and conflict-related losses. International development partners are increasingly offering guarantees to bring down financing costs, recognizing that risk-

sharing is essential to scaling access.

Investment insights for global readers

For impact-minded investors, Goma offers several lessons. First, backing proven developers with strong local teams matters more than backing technology alone. A reliable operator who hires and trains local staff, runs responsive customer service, and maintains spare-parts supply chains is the difference between a thriving utility and a failed experiment.

Second, blended finance remains the most effective pathway to scale. When public or philanthropic funds take the first-loss tranche, commercial capital can enter with greater confidence. Results-based financing and targeted subsidies reduce demand risk by ensuring developers are compensated for verified service delivery.

Third, instruments like Peace Renewable Energy Credits offer corporations an opportunity to meet climate commitments while producing measurable social impact. Companies that purchase these credits can demonstrate a dual win: reducing carbon footprints and improving community welfare in fragile regions.

Fourth, portfolio-level strategies are essential for managing currency risk. Because end users pay in local currency while many investors require returns in dollars or euros, developers must hedge across multiple sites or anchor revenues with customers who earn in hard currency, such as telecom towers or international NGOs.

Finally, investing in minigrids is not charity. When structured well, these projects generate stable cash flows from paying customers who value reliable electricity.

Across Africa, a quiet revolution is unfolding as the continent rapidly scales up solar power. The transformation is driven by record imports of solar panels, particularly from China, which remains the world’s dominant manufacturer. In 2025 alone, African nations imported more than one and a half gigawatts of Chinesemade solar panels, a figure that represents not only growing demand but also a profound shift in the economics of electricity across the region.

The timing could not be more critical. Africa continues to grapple with one of the world’s most severe electricity access deficits, with hundreds of millions living without reliable power. At the same time, surging urban populations, new industries, and growing digital infrastructure are placing unprecedented pressure on national grids. Against this backdrop, Chinese solar imports have arrived as a lifeline— cheaper, more efficient, and quicker to deploy than traditional centralized power stations.

China has achieved a level of scale and efficiency in solar manufacturing that no other nation can match. Years of statebacked investment, technological refinement, and cost optimization have made Chinese solar panels some of the most affordable in the world. For African governments and private developers, these low prices reduce barriers to entry, making large-scale solar farms and decentralized mini-grids financially viable.

The appeal goes beyond cost. Modern Chinese panels boast higher efficiency rates, longer lifespans, and better performance in hot climates compared to earlier generations. As a result, projects across Africa can generate more power

per square meter and maintain stable performance even in challenging environments such as deserts or tropical zones. For nations racing to electrify rural communities or reduce dependence on fossil fuels, these imports have become indispensable.

While panel imports are spread across the continent, a few countries have emerged as leaders in scaling solar. Algeria has recently become one of the fastest-growing markets, accounting for a large share of Africa’s total imports. Driven by government tenders and private investments, Algeria’s shift reflects both energy security concerns and a desire to diversify away from hydrocarbons.

In East Africa, Kenya and Ethiopia continue to integrate solar power into their grids while also supporting off-grid solar programs for rural communities. South Africa, with its energy crisis rooted in unreliable coal plants, has turned increasingly to solar as a backup and long-term alternative. Nigeria, Africa’s most populous nation, is expanding imports for both utility-scale projects and decentralized household systems, recognizing solar as a critical tool to reduce dependence on costly diesel generators.

Each of these markets demonstrates that the solar boom is not limited to one corner of Africa. From North Africa’s deserts to sub-Saharan rural villages, imported panels are being deployed across diverse landscapes and use cases.

One of the most transformative aspects of the solar boom is how it lowers the cost of electricity for households and small businesses. Diesel, long the mainstay of off-grid

power, is both expensive and environmentally damaging. By contrast, solar panel imports allow communities to install systems with predictable operating costs and little fuel dependency. Over time, households pay less for energy, and businesses can reinvest savings into expansion, job creation, or new equipment.

Utility-scale projects further demonstrate the economic appeal. Large solar farms built with imported panels now produce electricity at some of the lowest tariffs in African history. In competitive auctions, developers are bidding record-low prices, often undercutting fossil fuel plants. These savings ripple through the economy, improving competitiveness, reducing government subsidies for energy, and making industrial growth more feasible.

The rise of Chinese imports is not only about generating electricity but also about creating an ecosystem for renewable energy. Local companies are increasingly involved in the logistics, installation, and maintenance of imported systems. Training programs have sprung up across Africa to prepare a workforce capable of servicing solar infrastructure. This integration of foreign technology with local labor and entrepreneurship creates durable value, ensuring projects are sustainable in the long term.

Governments are also beginning to explore opportunities to localize parts of the value chain. Although full-scale manufacturing of solar panels in Africa remains limited due to cost disadvantages, there is growing momentum in assembling panels locally, producing mounting structures, and developing domestic inverter manufacturing. These industries create jobs while reducing import dependence and transportation costs.

The surge in Chinese imports has opened a wide spectrum of investment opportunities. One key area is financing for solar developers. Projects require significant upfront capital, and international investors who can provide equity or debt financing stand to benefit from steady, long-term returns tied to power purchase agreements. Given the falling costs of panels, project margins are improving, making solar an increasingly bankable sector. Another promising avenue is off-grid solar. Companies providing household kits and mini-grids are growing rapidly, serving millions of customers who may never be reached by traditional grids. Investors can back these firms through venture capital, impact funds, or blended finance structures that combine concessional funding with commercial capital. With consumer demand rising and repayment rates often strong, this sector offers scalable opportunities.

There is also space for corporate buyers and institutions to engage through renewable energy credits. Purchasing clean energy certificates from African projects helps companies meet sustainability commitments while channeling funds directly into the sector. For socially responsible investors, the double impact of emissions reduction and energy access expansion is particularly compelling.

Finally, ancillary industries connected to solar growth are ripe for investment. Companies providing storage solutions, smart metering, and financing platforms for pay-as-you-go solar systems are integral to the ecosystem. Each layer of the value chain presents its own opportunities for returns while supporting the broader clean energy transition.

Despite its promise, the solar boom is not without risks. Currency fluctuations can challenge project economics, as

many imports are denominated in dollars while revenues come in local currencies. Investors must account for exchange rate volatility and, where possible, hedge against it.

Political risk is another factor. Regulatory environments in Africa vary widely, and sudden policy shifts—such as tariff changes or restrictions on imports—can disrupt markets. Careful due diligence and diversification across multiple countries help mitigate exposure.

Quality control is also a concern. With the influx of panels, not all imports meet the same standards. Ensuring that panels come from reputable manufacturers and are installed by trained professionals is critical for long-term performance. Investors should prioritize developers and suppliers with proven track records.

Lastly, infrastructure constraints remain. Even with cheap panels, bottlenecks such as inadequate transmission networks can limit the ability of solar farms to feed power into the grid. For off-grid systems, distribution logistics and aftersales service are essential to ensure customer satisfaction and system longevity.

The influx of Chinese solar technology into Africa is not only an economic development but also a geopolitical one. As China deepens its role in Africa’s energy transition, it strengthens ties with governments across the continent. This dynamic brings opportunities for rapid deployment but also raises questions about dependency. African policymakers must balance the benefits of affordable imports with strategies to develop local industries and maintain control over their energy futures.

For Western investors and institutions, the solar boom represents both a challenge and an opening. While China dominates manufacturing, there is significant room for capital, expertise, and innovation from Europe, North America, and regional African players to shape how projects are financed, built, and sustained. Collaborations that combine Chinese hardware with African entrepreneurship and international finance could unlock even greater potential.

The record imports of solar panels highlight a turning point in Africa’s energy journey. What once seemed impossible— deploying large-scale renewable energy at competitive costs —is now becoming the norm. Villages, towns, and cities that struggled with darkness and diesel dependence are stepping into a cleaner, more reliable energy era.

The momentum shows no signs of slowing. With continued support from investors, development finance, and innovative entrepreneurs, Africa’s solar sector could become one of the fastest-growing in the world. The combination of abundant sunlight, falling panel costs, and rising demand for energy makes the continent uniquely positioned to leapfrog traditional fossil fuel pathways.

For investors, the message is clear. Africa’s solar boom, powered by Chinese imports, is not a passing trend but a structural shift. Those who position themselves now— whether through financing, off-grid ventures, or ancillary industries—will not only capture financial returns but also contribute to reshaping the continent’s future.

Powering Africa’s Future through Bold Electrification Goals

Africa is standing on the cusp of a defining energy transition.

In early 2025, the Islamic Development Bank and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank pledged more than six billion dollars to support an ambitious initiative known as “Mission 300.” The goal is straightforward yet monumental: bring electricity access to 300 million Africans by 2030. This effort, coordinated with the World Bank and the African Development Bank, signals the largest collective financing push ever targeted toward solving Africa’s energy poverty.

For decades, the challenge of electrifying Africa has been one of scale and sustainability. Roughly six hundred million people across the continent still lack access to power, making Africa home to the largest share of the global electricity access deficit. The implications reach far beyond energy itself. Without reliable electricity, education is hindered, healthcare services remain constrained, small businesses cannot expand, and entire regions struggle to attract investment. Mission 300 is designed to address these challenges head-on with the urgency that the problem demands.

The initiative arrives at a time when the global energy landscape is rapidly shifting. The cost of renewable technologies, particularly solar and wind, has plummeted over the past decade. Decentralized energy solutions such as mini-grids and solar home systems have matured, proving their ability to provide reliable electricity at scale. Meanwhile, global development institutions are under pressure to demonstrate tangible progress toward the Sustainable Development Goal of universal access to affordable and

reliable energy by 2030.

Mission 300 represents a convergence of these trends. It acknowledges that large, centralized grid projects alone will not be sufficient to close Africa’s access gap quickly enough. Instead, the initiative emphasizes a mix of grid expansion, renewable energy projects, and decentralized systems tailored to rural and peri-urban communities. By aligning finance, policy, and technology, it aims to create a coordinated pathway to universal access within the decade.

At the core of Mission 300 is a financing model that blends concessional funding with commercial capital. The six billion dollars pledged serve as an anchor, attracting additional investment from bilateral donors, private sector players, and regional development banks. This layered approach reduces risk for investors while ensuring that projects remain financially viable in challenging environments.

The funds are earmarked for a diverse set of interventions. In some regions, resources will flow toward grid extension projects that connect villages and towns located near existing transmission lines.

In others, the emphasis will be on building renewable energy plants, often solar or wind, to increase generation capacity for national utilities. Perhaps most transformative is the focus on decentralized solutions: mini-grids, micro-grids, and solar home systems capable of powering communities far from the grid.

This multi-pronged strategy acknowledges the continent’s diversity. In densely populated Nigeria, for instance, expanding existing grids is more feasible than in sparsely populated regions of the Sahel, where stand-alone systems may be

the only cost-effective option. By tailoring solutions to local contexts, Mission 300 avoids the one-size-fits-all approach that has limited past electrification drives.

The benefits of electrifying 300 million people go far beyond simply turning on lights. Reliable electricity transforms every sector of society. In healthcare, clinics gain the ability to refrigerate vaccines, power diagnostic equipment, and provide emergency services at night. Schools can extend teaching hours, integrate digital tools, and improve student outcomes. Small and medium enterprises—the backbone of most African economies—can expand operating hours, reduce costs, and access new markets.

Women and girls stand to gain in particular. Energy access reduces the burden of household chores by powering clean cooking solutions and water pumps, freeing up time for education and incomegenerating activities. Access to electricity also enhances safety, with street lighting and household lighting reducing risks associated with darkness in rural areas.

Economically, electrification is a direct enabler of industrial growth. Manufacturing plants require stable power to operate efficiently, and investors are more likely to commit capital when they can rely on an affordable energy supply. Mission 300 thus positions itself not just as a social program but as a cornerstone of Africa’s broader development and industrialization agenda.

Despite the optimism, Mission 300 faces significant hurdles. Financing is one piece of the puzzle, but implementation is

Mission 300’s scale and ambition create fertile ground for investors seeking both returns and impact. Financing utility-scale renewable energy projects is an obvious pathway. With concessional capital de-risking many ventures, private investors can enter with greater confidence. Power purchase agreements signed with utilities or government agencies provide long-term revenue certainty, making these projects attractive to institutional capital.

equally critical. Many African utilities are financially distressed, struggling with high debt, poor billing systems, and transmission losses. Without reform, grid expansion projects risk being undermined by inefficiencies.

Security is another challenge. In fragile states, energy infrastructure can become a target for conflict or vandalism, deterring private investment. Currency volatility also complicates project economics, as many investments are denominated in dollars while revenues are collected in local currencies. These risks highlight the importance of blended finance structures that can absorb shocks and reassure investors.

Policy frameworks will be decisive. Countries that streamline licensing, provide transparent tariffs, and support private sector participation are far more likely to attract investment. Conversely, bureaucratic delays and unpredictable regulations could slow progress. Mission 300 will need to work closely with governments to create enabling environments that balance consumer affordability with investor confidence.

Renewable energy lies at the heart of Mission 300. Africa is blessed with abundant solar potential, significant wind corridors, and untapped hydropower resources. Falling technology costs have made renewables the most cost-effective option for new generation capacity in many markets. Solar mini-grids, in particular, are emerging as the fastestgrowing solution for rural communities.

The initiative’s emphasis on clean energy also aligns with global climate commitments. By leapfrogging to renewables, Africa can avoid the carbon-intensive development pathways followed by industrialized nations. This not only supports the fight against climate change but also attracts climate finance from global funds eager to back projects with strong mitigation and adaptation benefits.

For African nations, the shift toward renewables reduces dependence on imported fossil fuels, improving energy security and protecting economies from volatile oil and gas prices. Local communities benefit from cleaner air and reduced health risks associated with pollution.

Mission 300’s scale and ambition create fertile ground for investors seeking both returns and impact. Financing utility-scale renewable energy projects is an obvious pathway. With concessional capital de-risking many ventures, private investors can enter with greater confidence. Power purchase agreements signed with utilities or government agencies provide longterm revenue certainty, making these projects attractive to institutional capital.

Off-grid and mini-grid companies present another significant opportunity. These businesses are often nimble, innovative, and deeply connected to local communities. Investors can support them through venture capital, private equity, or debt financing, with the potential for strong growth as millions of new customers come online. The pay-as-you-go model has already demonstrated success in countries like Kenya and Uganda, with repayment rates often exceeding expectations.

Ancillary services also deserve attention. Companies providing storage solutions, smart metering, or digital platforms for energy payments are integral to making electrification

For investors, Mission 300 offers a rare alignment of financial opportunity and social impact. It opens pathways to participate in Africa’s growth story while contributing to one of the most consequential development goals of our time. Those who engage early, structure investments wisely, and partner with credible actors stand to benefit from both steady returns and the satisfaction of driving meaningful change.

efficient and scalable. By investing in these enabling technologies, financiers can capture value across the supply chain.

There is also room for impactfocused instruments. Green bonds, sustainability-linked loans, and renewable energy credits allow investors to channel capital into Mission 300 projects while meeting environmental, social, and governance goals. Corporate buyers can engage by purchasing renewable energy directly from African projects, offsetting emissions while supporting electrification.

While the opportunities are compelling, investors must carefully manage risks. Currency volatility remains a major concern, with local revenues often collected in weaker currencies. Investors can mitigate this by seeking projects with partial hardcurrency revenues or by employing hedging strategies at the portfolio level.

Political risk insurance, offered by multilateral agencies, provides another layer of protection. Coverage against expropriation, breach of contract, or conflict-related losses

makes it easier to secure financing and lower the cost of debt. In fragile markets, guarantees from development banks can be decisive in bringing projects to financial close.

Due diligence on partners is critical. Working with established developers, local companies with community ties, and institutions with strong governance records reduces the risk of project failure. Investors should also prioritize countries with clear and supportive regulatory frameworks, as policy uncertainty can erode returns.

Finally, diversification is key. Spreading exposure across multiple markets reduces the impact of country-specific risks and allows investors to benefit from Africa’s diverse energy landscape.

Mission 300 is more than just an electrification initiative; it is a blueprint for how Africa can mobilize global capital, leverage renewable resources, and empower its people through energy. By targeting 300 million new connections by 2030, the program sets a benchmark for ambition and urgency.

The initiative demonstrates that large-

scale development goals are achievable when governments, multilateral institutions, and the private sector work in concert. It also reflects a broader recognition that solving energy poverty is not just about social equity but about laying the foundation for economic transformation. Reliable power is a prerequisite for industrialization, digital growth, and the creation of millions of jobs.

For investors, Mission 300 offers a rare alignment of financial opportunity and social impact. It opens pathways to participate in Africa’s growth story while contributing to one of the most consequential development goals of our time. Those who engage early, structure investments wisely, and partner with credible actors stand to benefit from both steady returns and the satisfaction of driving meaningful change.

At its heart, Mission 300 is a call to action. It is a recognition that the future of Africa, and indeed the world, depends on unlocking the potential of its people through access to electricity. By mobilizing resources, fostering innovation, and building resilient systems, this initiative could redefine the continent’s trajectory for generations to come.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, a young inventor named Vital Nzaka has captured global attention with a bold claim: that electricity can be generated directly from plants. Nzaka, sometimes referred to as Vital Vitium in reports, represents a wave of African innovators who are experimenting with unconventional approaches to power generation. His work taps into the idea that the natural processes within living plants and soil can be harnessed to produce usable energy for households and communities.

While still in its early stages, the story of plant-based electricity in Congo speaks to the larger theme of African ingenuity emerging in places with limited resources but abundant creativity. In a country where millions remain without access to reliable electricity, even small breakthroughs hold life-changing potential. Nzaka’s work raises important questions about how grassroots innovations might complement large-scale projects in solving Africa’s vast energy deficit.

The principle behind generating electricity from plants is based on

bioelectrochemical processes. As plants photosynthesize, they produce organic compounds that are released into the soil. Microorganisms then break down these compounds, releasing electrons as part of their metabolic process. By placing electrodes in the soil and connecting them to a circuit, it is possible to capture those electrons as a form of low-voltage current.

In practical demonstrations, Nzaka has shown small systems where plants act as “biological solar panels.” While each individual unit generates only modest amounts of electricity, they are capable of powering lights, charging mobile phones, or running small appliances. With scaling, modular plant-based grids could become a decentralized option for rural communities cut off from national electricity networks.

Globally, the concept is not entirely new. Research institutions in Europe and Asia have experimented with microbial fuel cells and plant-based bioelectrical systems for years. What makes Nzaka’s work significant is that he has taken this science out of the lab and into a local context, building prototypes with accessible materials in a country that needs immediate solutions.

The promise for Congo Congo’s electricity gap is severe. Despite the country’s immense hydropower potential from the Congo River, large-scale projects have been slow to materialize, and access remains extremely limited outside major cities. Millions of Congolese households rely on candles, kerosene lamps, or diesel generators.

Nzaka’s experiments with plant-based electricity point to a different path: small, decentralized systems that can be built and maintained locally. In villages where extending the national grid could take decades, bioelectric systems could offer an interim solution. They are quiet, renewable, and integrated with the natural environment. For farmers, the idea of generating energy directly from crops or surrounding vegetation carries both symbolic and practical weight.

If refined and scaled, this technology could power schools, clinics, and homes in off-grid areas. Even if it never fully replaces conventional power, it could supplement existing systems and reduce dependence on costly fuels.

The biggest challenge is scale. Current prototypes produce low amounts of power—sufficient for basic lighting or charging, but not for high-demand uses like refrigeration or machinery. Improving output will require both technical refinement and investment in better materials. Electrodes, converters, and storage systems must be optimized to increase efficiency.

Durability is another concern. Systems exposed to soil and water need to withstand corrosion, variable temperatures, and heavy use. Maintenance protocols must be simple enough for local communities to handle without constant external support.

Skepticism also remains among experts. While the science behind microbial energy is sound, the leap from laboratory experiments to reliable community-level systems has not yet been achieved at scale. Nzaka’s claims must be validated by independent testing to prove that the systems are safe, efficient, and capable of longterm operation.

For investors and development partners, supporting plant-based electricity at this stage is less about immediate returns and more about long-term positioning in an emerging technology. Early backers of such innovations can help shape the research, build intellectual property, and secure first-mover advantages if the systems prove commercially viable.

Impact investors in particular have a role to play. Small grants or seed funding could help innovators like Nzaka refine prototypes, acquire better components, and test systems under controlled conditions. Universities and research labs could be brought in to provide scientific validation, bridging the gap between grassroots invention and formal recognition.

Another investment pathway lies in hybridization. Plant-based systems may work best when integrated with other renewable solutions. Investors could fund pilot projects where bioelectric setups supplement solar or small hydro, creating diversified micro-grids. This spreads risk and offers communities more consistent power.

Companies that focus on sustainable agriculture and land restoration may also see synergies. Supporting plantbased electricity aligns with broader goals of eco-friendly development, carbon reduction, and circular economies. For corporate social responsibility portfolios, this technology offers a compelling narrative: turning fields and forests into power plants while empowering rural communities.

Broader significance for African innovation

Nzaka’s story, whether ultimately proven scalable or not, represents something larger. It underscores Africa’s growing role as a source of creative approaches to global problems. Instead of waiting for imported solutions, local inventors are experimenting, prototyping, and adapting advanced ideas to their own realities.

The symbolism of drawing power directly from the land also resonates deeply with Africa’s identity. It reflects a shift from dependence on costly imported fuels toward homegrown, sustainable energy rooted in the continent’s natural abundance. For young Africans, Nzaka’s example is an invitation to innovate boldly, even in the absence of formal training or wellequipped laboratories.

Vital Nzaka’s experiments with electricity from plants remain at an early stage, but the concept has captured imaginations across the continent. To move forward, the technology will need rigorous testing, engineering refinement, and the support of institutions willing to fund unconventional ideas. Governments can play a role by creating innovation funds that back local inventors, while international partners can provide mentorship and technical expertise.

If these systems can be scaled up and proven reliable, they could become part of the mosaic of solutions that bring power to millions of Africans still living in the dark. Even if they remain supplementary, they remind the world that answers to the energy crisis may come from unexpected places.

For investors and policymakers, the lesson is clear. Africa’s innovation story is not limited to large infrastructure projects or imported technologies. It is also being written by individuals like Nzaka, whose willingness to experiment with the natural world may light the way toward a more sustainable and selfreliant future.

A revolution built on access and affordability

enya has emerged as one of the world’s leading markets for off-grid solar power, thanks to the rise of pay-asyou-go models that make clean energy affordable for millions of households. In a country where extending the national grid into remote regions remains expensive and slow, innovative solar companies have stepped into the gap with decentralized solutions. By combining affordable solar kits with mobile money payments, Kenyan innovators are proving that universal energy access is achievable without waiting decades for grid expansion. The model is simple but powerful. Families purchase solar home systems —complete with panels, batteries, LED lights, and sometimes appliances—on credit. Payments are made in small installments through platforms like MPesa, Kenya’s ubiquitous mobile money service. Once the system is fully paid off, ownership transfers to the household, which then enjoys free power for years to come. This approach removes the barrier of high upfront costs and aligns with the income flows of rural and low-income families, who often earn and spend in daily or weekly increments.

Kenya’s success is no accident. The country boasts one of the most advanced mobile money ecosystems in the world, with M-Pesa enabling financial inclusion even in remote villages. This infrastructure made it possible for solar companies to offer flexible payment schedules tied directly to customers’ phones. For many households, their first formal financial relationship has been through a solar company.

Government support has also been instrumental. Kenya was among the first African countries to exempt solar products from value-added tax and import duties, reducing costs for consumers. Public-private partnerships, donor funding, and results-based financing programs have created an enabling environment for rapid growth. These efforts have encouraged companies like M-KOPA, d.light, and Sun King to scale rapidly, serving millions of customers across the country and beyond.

The business model thrives because it reflects the realities of rural life. Instead of expecting households to pay large sums upfront, companies allow them to pay in small, manageable amounts. The result is widespread

adoption and strong repayment rates, proving that low-income families are willing and able to pay for reliable energy when the terms are right.

Transforming lives at the household level

The impact of pay-as-you-go solar is visible in every corner of rural Kenya. Children can study at night without the dangers of kerosene lamps, improving educational outcomes. Women running small businesses benefit from longer working hours and the ability to use appliances like sewing machines or refrigerators. Families save money over time, since solar payments are often lower than what they used to spend on kerosene, candles, or diesel.

Health benefits are also significant. Kerosene lamps release toxic fumes linked to respiratory illnesses, particularly in children. By replacing them with clean solar lighting, families enjoy healthier living environments. Moreover, access to phone charging at home reduces the need for long trips to charging stations, saving time and increasing safety.

At the community level, the ripple effects are profound. As more households adopt solar systems, evening markets flourish, social interactions

extend into the night, and communities feel safer under well-lit surroundings.

The pay-as-you-go solar model is not just about individual households; it’s also an engine of job creation. Thousands of Kenyans are employed as sales agents, technicians, and customer service representatives within the offgrid solar industry. Many of these jobs are in rural areas, providing opportunities for young people who might otherwise migrate to cities.

The financial inclusion aspect is equally important. Customers who maintain consistent repayment histories with solar companies often build credit profiles, which can later be used to access loans for education, farming, or business expansion. In this way, solar systems serve as entry points into the broader financial system.

For the national economy, off-grid solar reduces reliance on imported fuels, easing pressure on foreign exchange reserves. It also complements national grid efforts by electrifying communities

that would be too costly to connect in the near term. Together, these benefits contribute to Kenya’s development goals while supporting global climate commitments.

Despite impressive progress, the sector faces challenges. Affordability, while improved, remains a hurdle for the poorest households, even with flexible payments. Companies must balance the need for low prices with the costs of providing quality products and aftersales service.

Sustainability of business models is another concern. Many solar companies rely on continuous streams of investor capital to finance consumer credit. Ensuring long-term profitability requires careful management of repayment rates, currency risks, and operational expenses.

There are also issues around product quality. The rapid growth of the sector has attracted counterfeit or substandard products that can undermine consumer confidence. Regulators and industry associations must continue enforcing

standards to protect customers and maintain trust.

Finally, reaching the most remote communities remains logistically challenging. Distribution networks must be extended, and after-sales support has to be guaranteed in regions where transportation is difficult and costly.

Kenya’s pay-as-you-go solar industry presents diverse opportunities for investors. One of the most attractive is direct investment in solar companies that are scaling operations across East Africa. With millions of potential customers still unserved, the market remains vast. Equity and debt financing can support expansion, product innovation, and entry into new regions.

Another avenue is investment in financial vehicles that support consumer credit. Since the pay-as-you-go model relies on extending loans to customers, companies need access to affordable capital. Investors who provide this capital through structured debt, green

bonds, or blended finance arrangements can earn returns while enabling broader access to solar power.

Ancillary industries also hold promise. The rise of solar adoption drives demand for energy-efficient appliances such as DC-powered televisions, fans, and refrigerators. Investing in companies that manufacture or distribute these appliances taps into a growing market linked directly to off-grid electrification.

Impact-focused investors can participate through results-based financing mechanisms, where payouts are tied to the number of verified connections or the amount of clean energy delivered. This ensures measurable outcomes while reducing risk for investors.

For corporate buyers seeking sustainability opportunities, purchasing renewable energy certificates or carbon credits from solar projects offers a way to meet climate goals while directly supporting energy access in Kenya.

As with any emerging market, investing in Kenya’s off-grid solar sector comes

with risks. Currency fluctuations can erode returns, as revenues are collected in Kenyan shillings while many investors expect returns in hard currencies. Portfolio-level hedging and careful structuring of debt can mitigate this risk.

Regulatory changes are another factor to monitor. While Kenya has historically supported solar, sudden shifts in import duties or tax policies could affect the economics of projects. Investors should engage with local industry associations to stay informed and advocate for stable policies.

Customer repayment risk is inherent in the pay-as-you-go model. Although repayment rates are generally strong, economic downturns or unexpected shocks can impact customers’ ability to pay. Companies with robust data analytics and flexible repayment options are best positioned to manage this risk.

Finally, reputational risk exists if companies fail to deliver reliable products or adequate customer service. Investors should conduct thorough due diligence, prioritizing firms with proven

track records and strong governance.

Kenya’s global significance

Kenya’s pay-as-you-go solar sector has become a global case study in how innovation, technology, and finance can converge to solve energy poverty. By leveraging mobile money and consumer credit, the country has demonstrated a model that can be replicated across Africa and beyond. Its success shows that the last mile of electrification does not need to wait for national grids but can be achieved through market-driven solutions that are both scalable and sustainable.

For investors, Kenya offers more than just financial returns. It presents a chance to participate in one of the most impactful development stories of the decade. Every household that adopts a solar system experiences immediate improvements in health, education, and economic opportunity. At scale, these changes transform communities and contribute to national progress.

Kenya’s story is proof that the intersection of technology and finance

outh Africa has long grappled with the tension between abundant renewable potential and a power sector heavily reliant on coal. As rolling blackouts and grid instability have weighed on businesses and households, the need for innovative solutions has grown urgent. In 2025, the launch of Ampli Energy, a joint venture backed by Discovery and Sasol, marked a turning point. Unlike traditional utilities, Ampli Energy offers businesses flexible, month-to-month access to renewable energy, complete with incentives such as cashback for participation.

The platform reflects a broader global trend: moving away from rigid, centralized power supply toward consumer-centric models that treat energy as a service. By focusing on corporate clients, Ampli Energy taps into both financial and environmental priorities, helping companies lower costs while advancing sustainability commitments. For South Africa, where the energy transition is not only about climate but also economic survival, the emergence of this model is especially significant.

Ampli Energy positions itself as a bridge between renewable generation and end users. The company aggregates clean power from a mix of sources— solar farms, wind projects, and other renewable plants—and delivers it directly to corporate customers through contracts that emphasize flexibility. Unlike long-term power purchase agreements, which typically lock companies into commitments for a decade or more, Ampli Energy offers the ability to adapt month by month.

This flexibility addresses one of the main barriers to renewable adoption in South Africa: the reluctance of businesses to commit to lengthy deals in an uncertain energy landscape. With Ampli, companies can test renewable supply without sacrificing agility, while enjoying financial incentives such as cashback for consistent participation.

For Discovery and Sasol, the platform also creates an opportunity to align brand identity with sustainability leadership, appealing to stakeholders who demand greener business practices.

The South African power sector is dominated by Eskom, a utility plagued by aging infrastructure, financial

distress, and chronic blackouts known locally as “load-shedding.” These outages disrupt productivity, increase operational costs, and discourage investment. While the government has made moves to liberalize the sector and encourage private generation, the pace of reform has struggled to keep up with demand.

Ampli Energy steps into this gap by offering an immediate alternative. Instead of waiting for Eskom’s grid to stabilize, businesses can plug directly into renewable supply, reducing their exposure to outages and volatile costs. The model not only provides resilience but also aligns with South Africa’s climate goals, which require a sharp reduction in coal dependence by midcentury. By giving companies the tools to transition quickly, Ampli accelerates both economic and environmental progress.

Initial uptake of the Ampli platform has been strongest among medium and large businesses seeking stability in the face of load-shedding. Companies in sectors such as retail, logistics, and manufacturing have been quick to adopt flexible renewable supply contracts, seeing them as a way to protect margins and demonstrate environmental responsibility. The promise of cashback

incentives further strengthens the value proposition, turning energy procurement into an opportunity rather than just a cost center.

The platform has also generated buzz in financial and sustainability circles. Analysts note that Ampli’s design reflects a maturing renewable sector in Africa, one where consumers are no longer passive recipients of power but active participants shaping their energy mix. In addition, the partnership between Discovery—a company with deep experience in behavioral incentives—and Sasol, historically a fossil-fuel powerhouse, highlights the evolving nature of South Africa’s corporate landscape. Even legacy players are embracing renewables as central to their future.

Broader economic and social impact

The implications of Ampli Energy extend beyond individual businesses. By driving demand for renewable supply, the platform indirectly stimulates investment in new solar and wind projects. Developers who might hesitate to commit capital in uncertain markets gain confidence knowing that corporate demand exists. Over time, this could accelerate the build-out of South Africa’s renewable infrastructure, reducing reliance on coal and improving national energy security.

Ampli also introduces a new paradigm for how energy interacts with the economy. By rewarding companies for consistent participation, it fosters a culture of efficiency and accountability. This could spill over into other areas, encouraging firms to adopt complementary technologies such as energy-efficient appliances, smart metering, and battery storage. Together, these changes move South Africa toward a more resilient and sustainable energy system.

At a societal level, the growth of renewable energy platforms creates

jobs in installation, maintenance, and operations. Local communities benefit from new infrastructure, while consumers gain indirect advantages through more stable electricity markets. The multiplier effects of investment ripple outward, strengthening the overall economy.

Investment opportunities in Ampli and beyond

The emergence of Ampli Energy signals clear opportunities for investors. One of the most direct pathways is participation in renewable project development. As Ampli aggregates supply from solar and wind farms, developers will seek financing to expand capacity. Equity investors, project financiers, and green bond issuers can all play roles in meeting this demand.

The platform itself presents opportunities for strategic investors interested in energy services. By combining renewable supply with innovative payment structures and incentives, Ampli is pioneering a model that could expand beyond South Africa. Investors who back its growth early may benefit from replication in other African markets facing similar challenges.

Ancillary sectors also hold promise. The success of Ampli will drive demand for storage technologies, as businesses seek to complement renewable supply with backup batteries. Investment in battery manufacturing, distribution, and recycling will become increasingly important. Similarly, digital platforms for smart energy management— tracking usage, optimizing costs, and integrating with corporate sustainability dashboards—are poised for growth.

For impact-focused investors, Ampli represents a compelling case. The platform delivers measurable carbon reductions by shifting businesses away

from coal-based power, while simultaneously supporting economic resilience. These dual benefits align with environmental, social, and governance mandates, making Ampli an attractive addition to sustainable investment portfolios.

As with any emerging model, risks must be considered. Regulatory uncertainty remains a challenge in South Africa’s energy sector. While the government has liberalized aspects of private generation, changes in policy or tariff structures could affect returns. Investors must stay engaged with policymakers and industry associations to advocate for stable, transparent frameworks.

Currency volatility is another concern. While Ampli operates in South Africa’s rand, many investors measure returns in dollars or euros. Hedging strategies and careful structuring of financial agreements are essential to protect against exchange rate fluctuations.

Market competition could also intensify as other energy service providers enter the space. However, Ampli’s early-mover advantage, combined with strong corporate backing, positions it well to maintain leadership. For investors, thorough due diligence on the platform’s long-term customer acquisition and retention strategies will be key.

Ampli Energy embodies the next stage of Africa’s renewable energy journey. It demonstrates that the continent is not just adopting clean technologies but reimagining how energy is consumed, financed, and rewarded. By placing flexibility and incentives at the heart of its model, Ampli reflects the realities of modern business, where agility and sustainability are inseparable from competitiveness.

South Africa’s energy transition is gaining momentum as innovative projects combine renewable resources with storage to stabilize a grid long plagued by shortages and blackouts. Among the most significant of these projects is the Oya Hybrid Power Station, a large-scale development that integrates solar, wind, and battery storage into one facility. Located in the Western Cape and Northern Cape regions, Oya is designed to supply consistent, dispatchable power— bridging the intermittency challenges that have often held renewables back.

With a projected capacity of around 128 megawatts of renewable generation supported by large-scale batteries, Oya is positioned to be a blueprint for hybrid power in Africa. The project’s structure reflects the urgent need for solutions that not only add clean energy to the grid but also ensure reliability. For South Africa, where “loadshedding” has become a daily reality, projects like Oya represent the promise of resilience and economic renewal.

South Africa’s reliance on coal has created a fragile and outdated power system. Eskom, the state utility, operates a fleet of aging coal plants that

frequently break down, leading to rolling blackouts. Although renewable capacity has grown through the government’s procurement programs, the intermittency of solar and wind has raised concerns about stability.

Hybrid stations like Oya address this directly. By combining solar and wind, the project benefits from complementary generation profiles: solar peaks during the day, while wind often performs better in the evenings or at night. Battery storage ensures that excess generation is saved and dispatched when needed, creating a steady supply of power to the grid. This design aligns perfectly with South Africa’s urgent need to reduce reliance on coal while avoiding further instability.

The Oya Hybrid Power Station is part of South Africa’s Risk Mitigation Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme (RMIPPPP), which was established to quickly add reliable power to the grid. With its hybrid design, Oya demonstrates that renewables can meet the criteria of dispatchability, a requirement once thought achievable only by fossil-fuel plants.

The facility is expected to serve tens of thousands of households while

supporting industrial and commercial activity in the region. Its strategic location allows it to tap into strong solar irradiation and wind resources, making the most of South Africa’s natural advantages. By coupling these resources with cutting-edge storage, Oya ensures that clean energy is not just abundant but available on demand.

The construction and operation of Oya will provide economic stimulus to surrounding communities. During the build-out phase, hundreds of jobs are created in engineering, installation, and logistics. Once operational, the project requires ongoing maintenance and monitoring, creating long-term employment opportunities.

Local suppliers benefit as well, with procurement strategies often requiring developers to source materials and services from South African companies. For communities nearby, the arrival of reliable electricity opens doors to improved infrastructure, new business ventures, and social programs funded by the project’s community development commitments.

At the national level, Oya contributes to reducing dependence on diesel peaker plants—expensive, polluting facilities often fired up during periods of peak

The Oya Hybrid Power Station represents more than just another renewable project; it is a test case for how South Africa can transition to a cleaner, more reliable energy system. By proving that renewables can provide dispatchable, round-the-clock power, Oya challenges the perception that coal or gas are necessary for baseload supply.

demand. By displacing these with renewable energy plus storage, South Africa lowers emissions, cuts fuel costs, and strengthens its climate commitments.

Financing and investment signals

Oya’s financing structure reflects the growing maturity of South Africa’s renewable energy sector. Backed by international investors, local partners, and development finance institutions, the project demonstrates that hybrid renewables are now bankable in emerging markets. Its inclusion in a government procurement program provides confidence through long-term power purchase agreements, ensuring predictable revenues.

For investors, Oya signals a shift from single-technology projects toward integrated systems that maximize

efficiency and reliability. The combination of solar, wind, and storage offers diversified revenue streams while reducing risk associated with variability. With the success of Oya, similar hybrid projects are expected to proliferate, creating a pipeline of opportunities across South Africa and the continent.

The rise of hybrid projects like Oya opens new avenues for investment beyond traditional renewable generation. Battery storage is one of the fastestgrowing sectors globally, and projects such as Oya demonstrate how storage can be monetized through grid services, peak shaving, and reliability guarantees. Investors in battery manufacturing, distribution, and recycling can capture value across this ecosystem.

Another promising area is grid integration and digital technology. Managing hybrid systems requires sophisticated software and smart controls to balance supply, demand, and storage in real time. Companies providing grid management solutions, data analytics, and optimization tools are poised to thrive as more hybrid facilities come online.

Local businesses also benefit. Hybrid plants often commit to community investment funds and procurement from local enterprises, creating opportunities for small and medium enterprises to participate in the renewable value chain. Entrepreneurs who position themselves as service providers—whether in construction, transport, or operations— stand to gain as projects like Oya expand.

While the Oya project is groundbreaking, investors must navigate challenges. Currency fluctuations remain a key risk, as project financing is often in foreign currency while revenues are tied to the South African rand. Policy uncertainty also requires caution; while the RMIPPPP framework provides stability, broader shifts in energy regulation could affect returns.

Technical risk is another factor. Integrating solar, wind, and storage at scale requires advanced engineering and operational expertise. Ensuring the system performs as designed will be critical to the project’s success. Investors should back developers with strong track records and experience in hybrid systems to mitigate these risks.

Community relations must also be

managed carefully. While hybrid plants bring benefits, they also require land and infrastructure that can impact local communities. Transparent engagement and fair compensation are essential for maintaining support and avoiding conflict.

The Oya Hybrid Power Station represents more than just another renewable project; it is a test case for how South Africa can transition to a cleaner, more reliable energy system. By proving that renewables can provide dispatchable, round-the-clock power, Oya challenges the perception that coal or gas are necessary for baseload supply. It sets a precedent for integrating multiple technologies to create stability

while reducing emissions.

For South Africa, this model could be replicated across provinces rich in renewable resources. For Africa more broadly, Oya offers a template for how hybrid projects can address energy poverty, reduce dependence on imported fuels, and align with global climate goals. For investors, it provides reassurance that ambitious renewable projects can be financially viable even in markets with policy and currency risks.

The Oya Hybrid Power Station is a symbol of resilience, innovation, and possibility. In a country desperate for solutions to its energy crisis, it shows that the future is not only renewable but also reliable.

A monumental step in Africa’s clean energy story

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is home to some of the richest renewable resources in the world, yet it also carries one of the largest electricity access gaps on the planet. In this context, the Green Giant Solar Project stands out as a transformative initiative. Planned as one of the largest solar developments in Central Africa, the project is expected to generate up to 1,000 megawatts of clean power once fully completed, with an initial phase of 200 megawatts already in development.

The Green Giant is not just about building another solar farm; it represents a significant reimagining of the DRC’s energy landscape. With most of the population still living off-grid, the project signals a shift toward modern, large-scale renewable infrastructure designed to accelerate electrification and reduce dependence on expensive and polluting diesel generators.

The DRC has historically relied heavily on hydropower from the Congo River, which holds immense potential but remains underdeveloped. Hydropower projects are capital intensive, take years to build, and are vulnerable to fluctuations in water levels caused by climate change. Meanwhile, the majority of Congolese people remain in the dark.