EDITION2 EDITION2

TV

Sharlotte Thou

Eliz So

Lucy Spencely

Niall Fleming

Kerry Jiang

Claire Oberdorfer

Khanh Linh (Kaylie) Nguyen

Bohong Sun

Sarah Patience

Yulia Liu

Kaz Marsden

Benjamin Springhall

Content

Aala Cheema

Manny Singh

Luca Ittimani

Perpetual Nkatiaa Boadu

Ruby Smuskowitz

Holly McDonell

Claudia Hunt

Emmanuelle Dunn Lewis

Olivia Chollet

Lara Connolly

Zoe Christofides

Daniel Pavlich

Radio

Maya Johnson

Nat Johnstone

Alexander An

Bridget Fredericks

Natasha Kie

Cate Armstrong

Punit Deshwal

Art

Max Macfarlane

Xuming Du

Hassan Alanzi

Cynthia Weng

Vera Tan

Amanda Lim

Fuz Buckley

Bob Fang

Management

Photography

Chris Jackson

Hima Panaganti

Benjamin Van Der Niet

Events

Jeffrey Liang

Arabella Ritchie

Social Media

Brianna Collett

News

Rosie Welsh

Zelda Smith

Dina Luate-Wani

Sophie Hilton

James Donnelly

Raida Chowdhury

Shebani Jeyakumar

Eleanor Rowland

Holly Johnson

Jasper Harris

Sam Kearney

Siobhan Perry

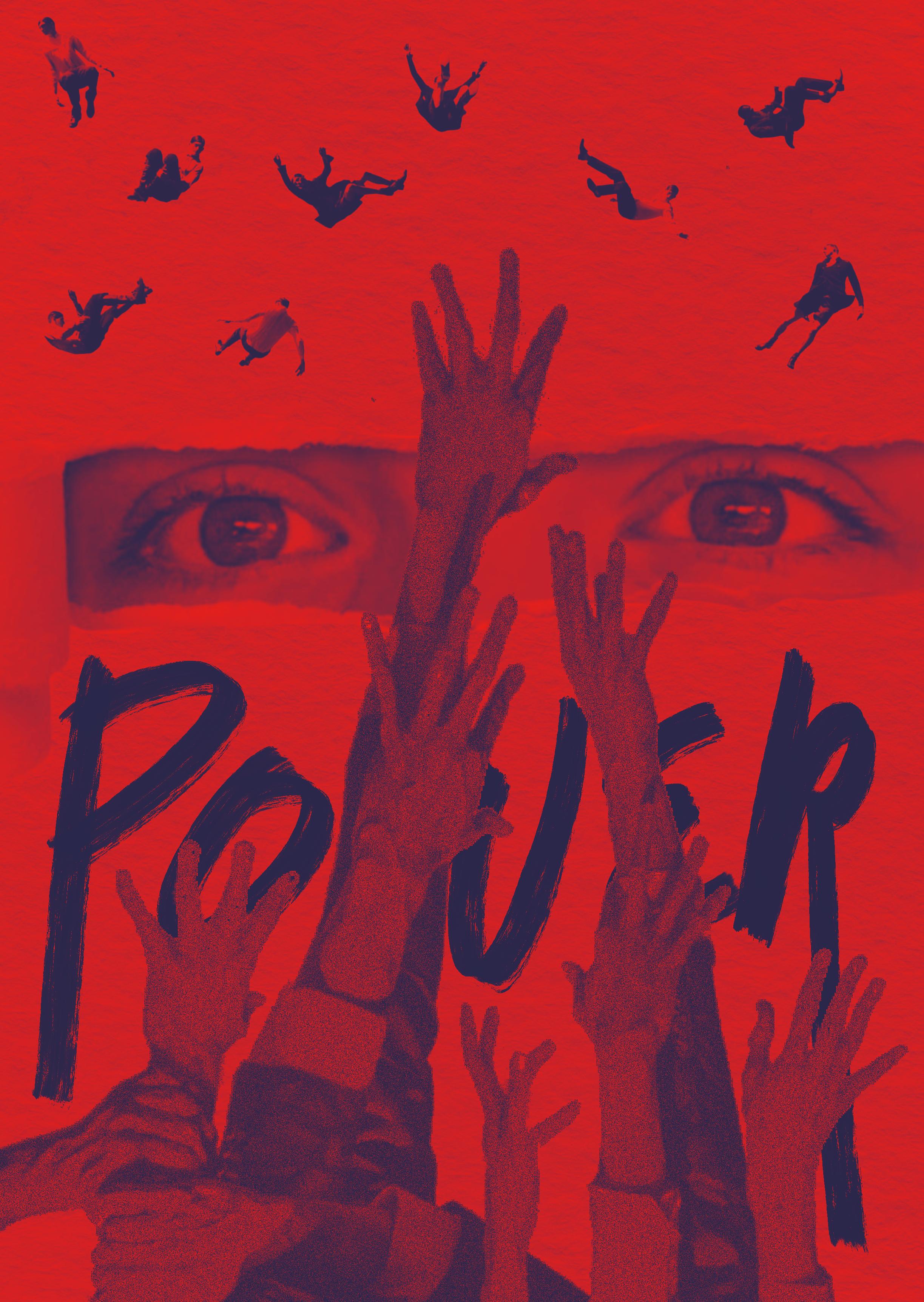

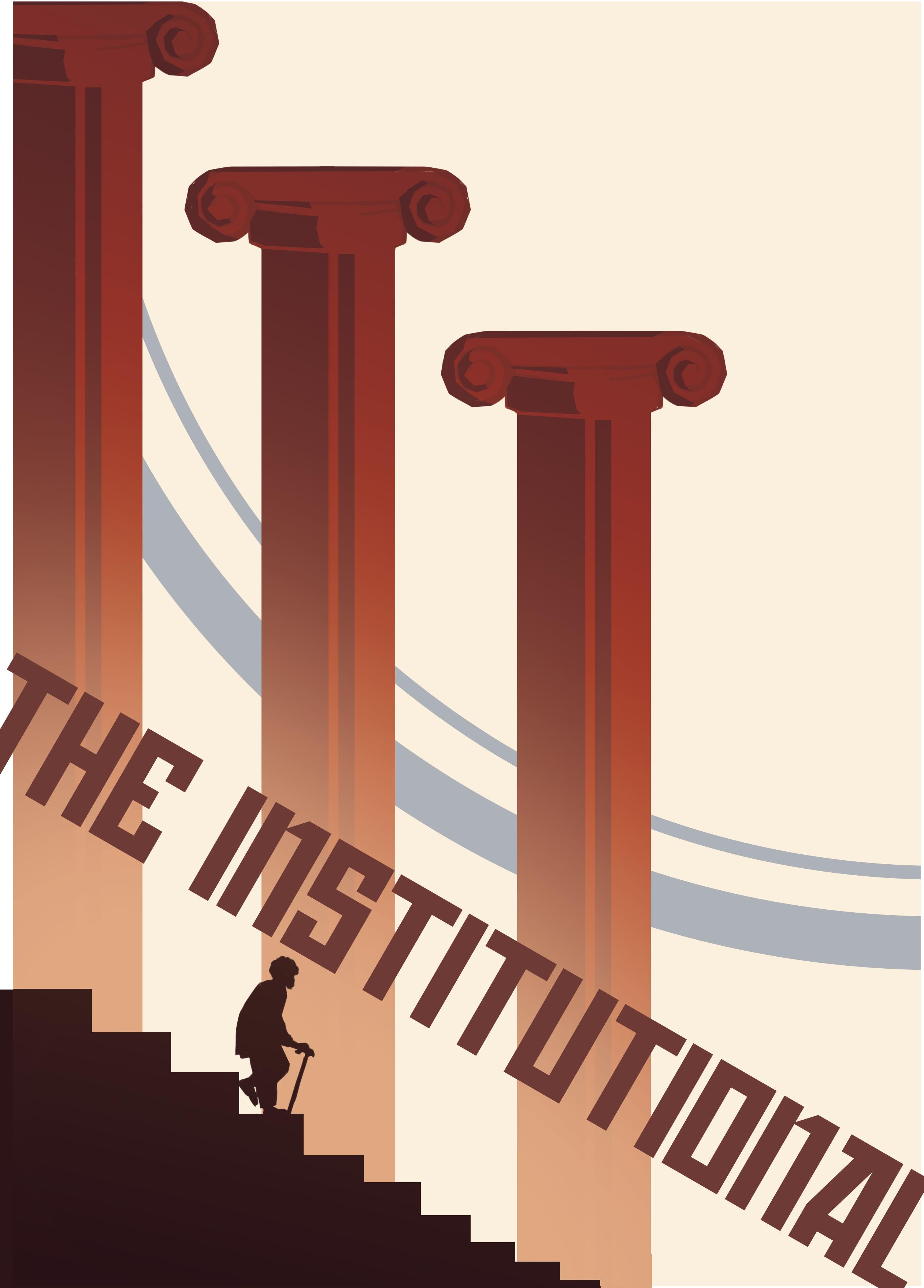

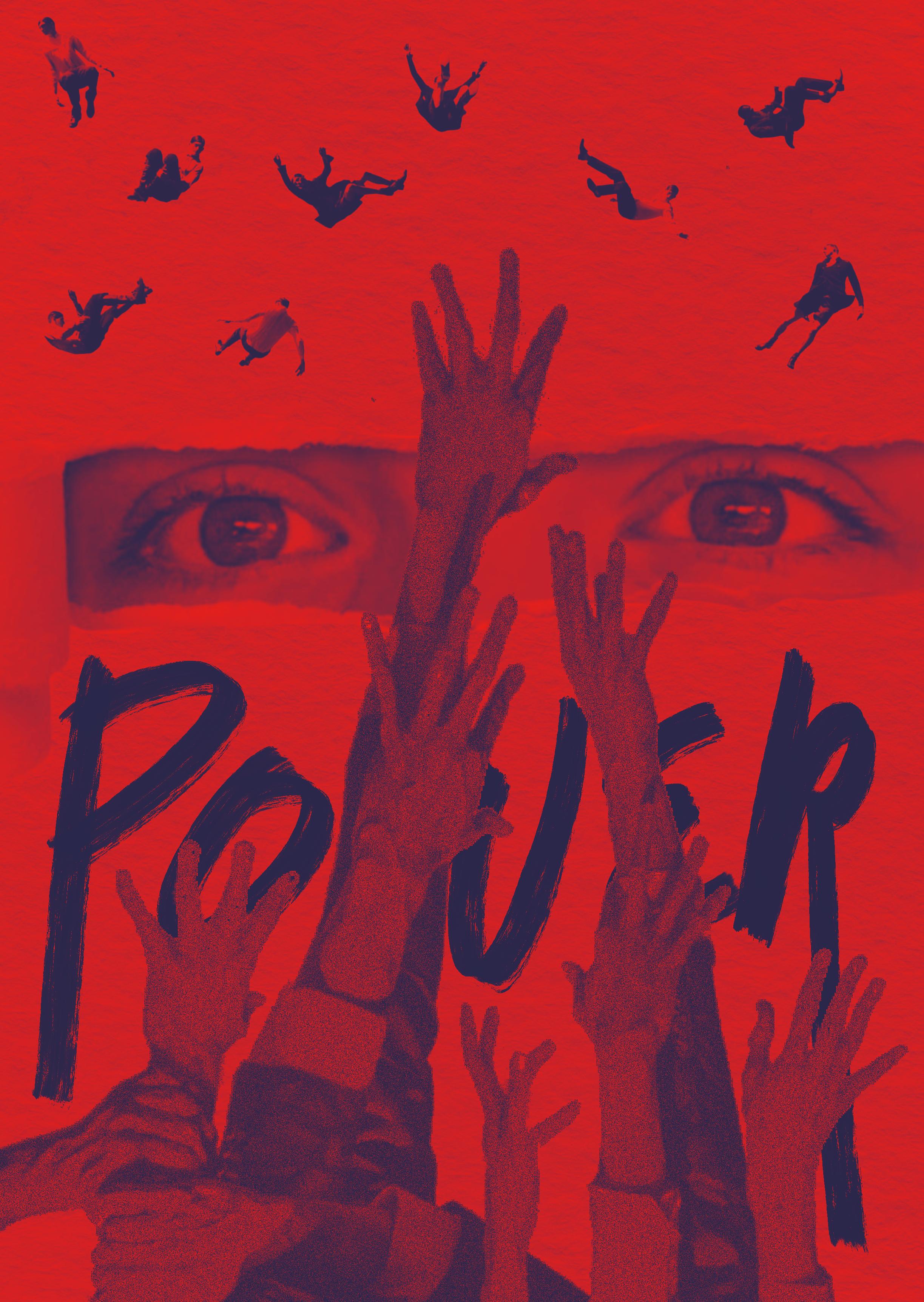

Cover art was created

By Bob Fang

1.

Art by Vera Tan

-

Art by Jasmin Small

Letter from the Editor: Question Everything

Universities should be places of enquiry, investigation and questions. Not a place where knowledge is necessarily fed to us, but where students cultivate the skills to ask the right question, at the right time, and to the right person.

It is when we do not question the events and decisions around us that we give way to forces of power. Complicity and obedience are the bread and butter, not only of autocratic regimes, but also of simple institutional malfeasance and abuse.

The robodebt inquiry, which continues to plod along, reflects this. Every person brought before the inquiry reveals a hidden culture, flourishing beneath the public service’s unthinking, unquestioning obedience. Yet, the very principle of robodebt, of oppressing and abusing the poor, rests on a raft of unanswered questions about humanity, kindness, and what it takes to survive in life. The inquiry began with the oldest of questions, which ought to drive us, “is this right?”

Universities are no longer places of enquiry. Investigations and questions are asked too infrequently. We may learn and study in class, but the big questions are no longer asked. Activism, debate, and concern have fallen by the wayside, lost somewhere between neverending funding cuts, and the need to sell out as the cost of living gnaws away.

There are important questions to ask of the ANU. What is happening to our degrees? Why do we, the students, the public, or the customers, have no say in the direction of our learning and of future generations’ learning? Why do our residences cost so much and why do we have so few rights when we live in them?

The ANU functions on the formula of not answering student questions. We still do not have a clear answer as to why the lock-out fee was increased with no warning, no consultation and no apparent due thought. Leaving questions unanswered leaves the structures and principles of immoral decisions intact and unchallenged. True answers are not single sentences, and they reflect the hierarchy of decision-making. An unanswered question is weaponised incompetence.

But, if we are to revitalise the practice of asking the right question, then there are questions for ourselves. When did we decide to let ANU make all the decisions? Our student elections suffer from incredibly poor turnout, compared to our past, and compared to other universities across the country. When did we decide student representation didn’t matter?

Such self-interrogation should not be self-flagellation. Consciousness and turning up are vital, but so is balance. Activism sustained by the community means we do not have to devote our lives to it, but merely speak up when needs be.

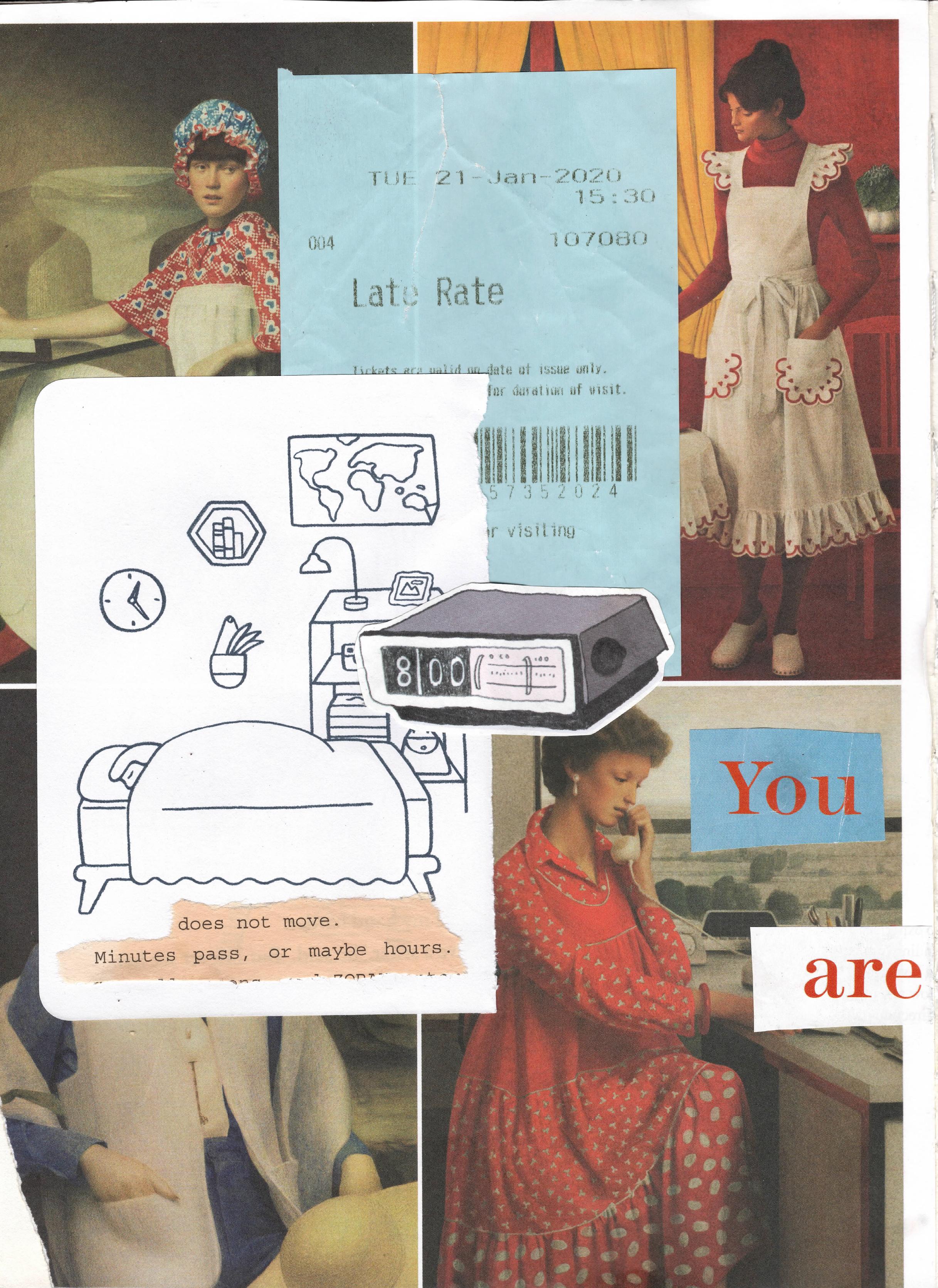

Sometimes, the ANU reminds me of a hot, stifled summer, where nothing moves, not even the grass. And I think of Camus and his empty humanity:

“My degree was cut today. Or maybe yesterday, I don’t know. I received an email from the ANU: ‘Degree cut. Funeral tomorrow. Very sincerely yours.’ That doesn’t mean anything. It might have been yesterday.”

Finally, a thank you to Lizzie Fewster and Jasmin Small, who are their own forces of power. I hope you enjoy the magazine they and their teams have laboured over. Ask us, have we asked the right questions?

Alexander Lane, News Editor

2.

Art by Jasmin Small 3.

4.

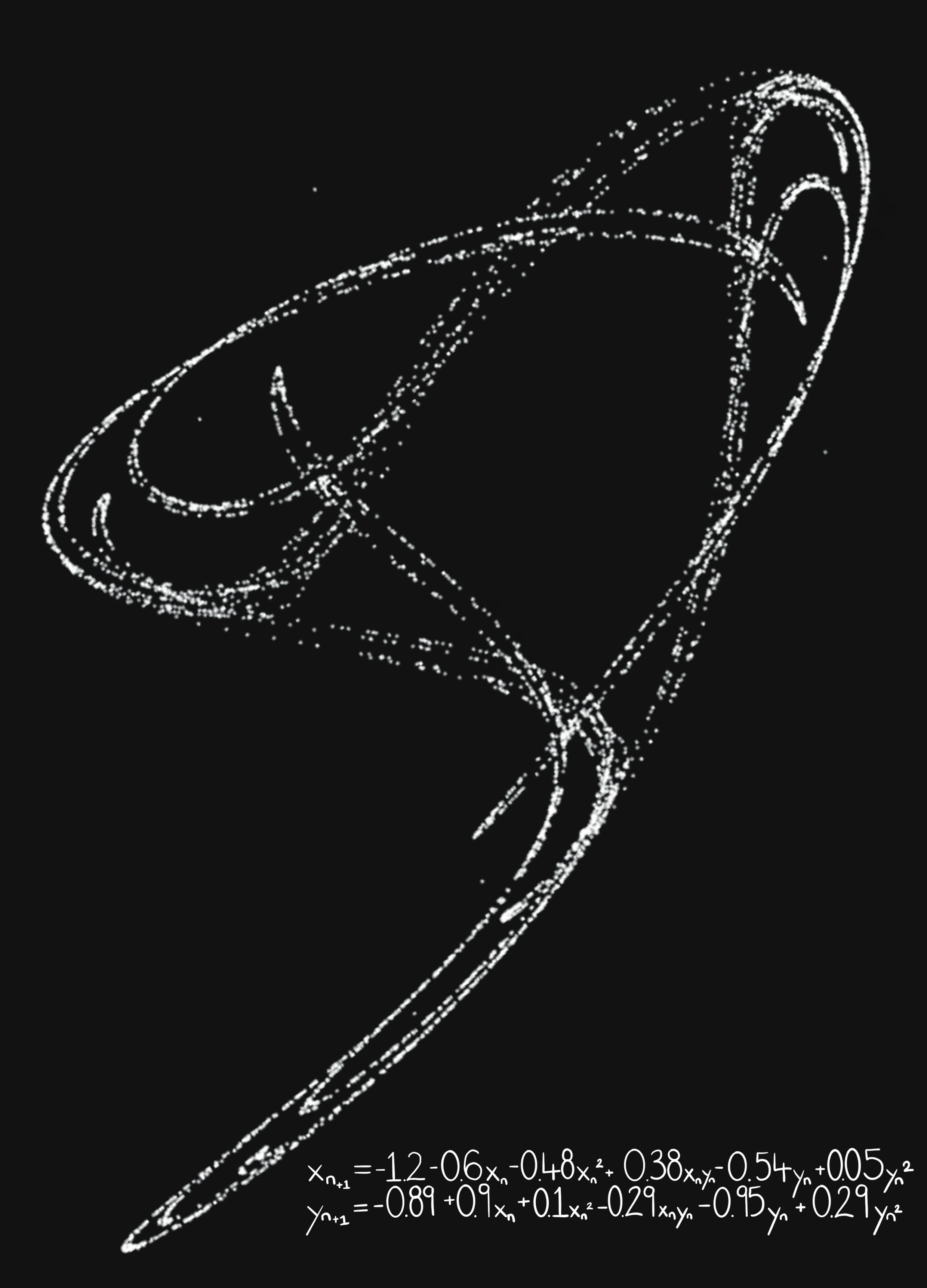

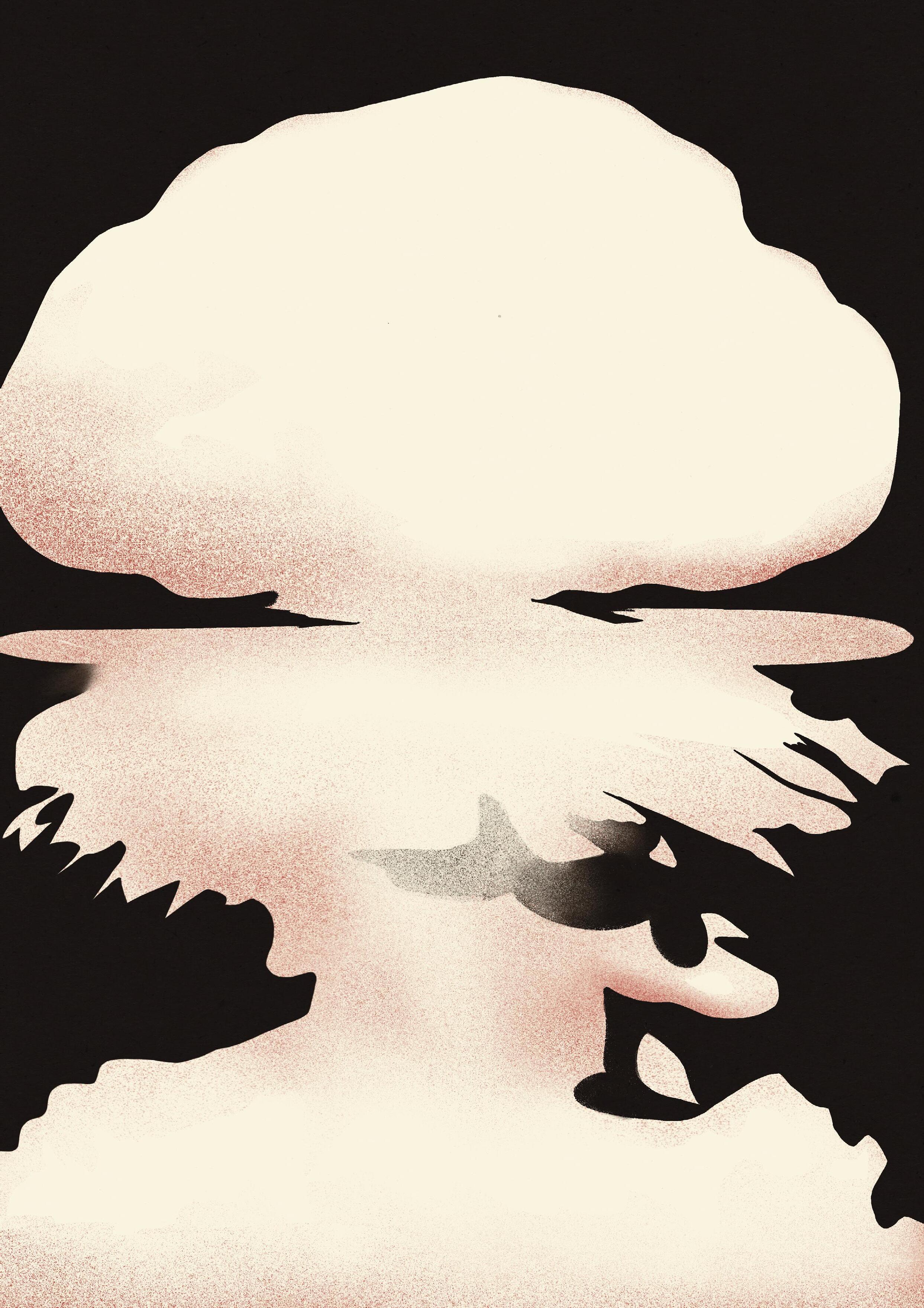

Art by Max Macfarlane

Election Analysis: We Can Go Back to Pretending NSW Doesn't Exist Jasper Harris

On the 25th of March NSW, Australia’s largest state, went to the polls and decided its next government and premier. The incumbent Coalition under Dominic Perrottet had been in power for 12 years and came up against Labor under Chris Minns, looking to return to power.

On election night, Chris Minns led the Labor party to a 6.5% swing and to a minority government. The Coalition lost 13 seats to Labor and independents statewide, a defeat that leaves big questions not just for the Liberal party in NSW but around the country. Labor now runs the continent, on a state and federal level, with only Tasmania home to a Liberal government.

The Coalition minority government was only two seats short of a majority and entered into 2023 seeking a fourth term. Yet, they also carried the baggage of losing the popular leader that took them to victory previously in 2019, Gladys Berejiklian, who resigned following the opening of a corruption inquiry.

On top of this, the Nationals lost charismatic leader John Barilaro, who was later embroiled in a ‘jobs for the boys’ scandal - a controversial appointment to a plump trade envoy job in New York he helped create. Even if people in NSW generally didn’t have an issue with new leader Dominic Perrottet, there was vast, apparent apathy and a momentum for change in the electorate.

The Liberals’ plan to win the election focused on the benefits of incumbency, portraying themselves as the better economic managers, while pledging to invest more into schools and hospitals, along with increased funding for public transport like Sydney’s new metro.

Under the leadership of Chris Minns since June 2022, Labor came into the election with 36 seats, having rebuilt to that point after their 32-seat loss in 2011, when they last held government.

Labor was looking to finish rebuilding its path to power and campaigned on a simple platform of anti-privatisation of government assets, and capping tolls in line with a broader cost of living agenda. The Coalition capped public sector worker wage rises at 3 percent, and Labor promised to repeal that, along with promising further funding for new schools, hospitals, and public transport. Labor also plans to invest $1 billion in a new government-owned body to fund renewable energy projects.

5.

Art by Jasmin Small

Art by Jasmin Small

Labor’s path to victory on election night was startling. With a swing of over 6%, Labor won many of the most marginal seats in the west and south of Sydney, and the South coast, building off the Bega byelection win last year. On the ABC’s election night coverage, just two and half hours after counting had started, the data was in, and there was no path for the Coalition back to power. However, despite the swing, it is not a resounding victory, as Labor has fallen two seats short of a majority government.

The big takeaway from election night was the Coalition’s story. Another major blow for the Liberal party, you now have to cross a sea to find a Liberal jurisdiction.

This means there is now a national issue for the Liberal ‘brand’. Dominic Perrottet resigned as leader of the NSW Liberals, and there’s now talk of a possible move to federal politics for him. The future discussion will focus on what the Liberals need to do after such resounding defeats across the country. Do they move to the centre to get back their metropolitan ‘heartland’ seats, like Kooyong, or North Sydney? Do they move further to the right as Peter Dutton and others in the party want? Right now though, the party of Menzies is struggling to attract a broad enough spread of voters to win back power anywhere.

The Nationals lost two seats in the election and have received another notice that they are falling out of favour with the rural electorates they traditionally represent. With Labor and other independents taking seats away from them, there is a need for a revamp among the nationals as to what the party stands for, as they can no longer bank on being the only country-focused political party.

With the Aston by-election coming up in Melbourne, in what should be one of the safest Liberal seats, there will be a big test for Peter Dutton’s leadership of the Liberals. For the Liberals to win again, there has to be a significant shift in focus back to core values and addressing the issues that led them to tumble from power all over the country. What exactly those core values are, though, remains contested.

Labor, for its part, now has momentum nationally. Though it occupies the traditional “left” of mainstream politics, the Greens and other progressive independents continue to challenge Labor and its more centrist policies. With the Liberals out of contention for the moment, the question is, will they go further on new policies? Will they revisit old challenges like capital gains and negative gearing? Will there be further changes to combat climate change?

Now in 2023, this feels like a new time in Australian politics. Between Labor so dominantly in control nationally, the Liberals having been so resoundingly defeated up and down the ballot, and the rise of minor parties and independents, it’s never been a more exciting time to follow politics. What happens next will be anyone’s guess. But at least we don’t have to read about NSW anymore.

6.

FOI Reveals Details of Ex-Senator George Brandis' Appointment as Professor Sophie Hilton

A Freedom of Information (FOI) request has revealed details about the appointment of former senator, George Brandis, as Professor in the Practice at the ANU in July 2022.

Brandis, who served as a Liberal Senator for Queensland until 2018, was a cabinet minister under the Abbott and Turnbull governments, Attorney General from 2013-2017 and most recently as High Commissioner to the United Kingdom. His appointment at ANU consists of a three year role as Professor in the Practice of National Security, Law and Policy, split between the National Security College and College of Law.

The email chain included in the FOI release reveals that his appointment was driven personally by Brian Schmidt, beginning with the Vice-Chancellor proposing his hire to other senior ANU staff. Schmidt proposed the appointment was beneficial to the ANU on the basis of Brandis’ ability to help “...us [ANU] better understand and engage the political process” and “...help us [ANU] raise money…through philanthropy.”

Brandis’ appointment also appears to have been well under way by the time the first email was sent. Brandis himself told an ANU employee: “...our [Brandis and Schmidt] discussions have been fairly advanced in terms of sorting out the details.”

Schmidt deemed the appointment “high priority”, and it was done without advertisement or the use of a selection committee. The documents cite “Identified Position” as the reason for doing so.

From: FOI Document 202200031

According to ANU’s appointment procedure, all appointments must be completed in a “fair and transparent manner” and are typically advertised, with some exceptions, including under the ‘Identified Position’ procedure. This procedure defines such a position as one “...with an essential personal requirement with the aim of promoting equality of opportunity for disadvantaged groups.” It goes on to list the circumstances in which positions may be presented as Identified Positions:

7.

“1. as part of special measures aimed at increasing representation of Aboriginal and/ or Torres Strait Islander staff to meet the employment targets under the ANU Enterprise Agreement; and

2. as part of special measures aimed at increasing representation of women in areas of the University where women are under-represented.”

Brandis is neither a woman nor of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Island descent.

Despite the recruitment documentation, a spokesperson for ANU has attested that Brandis was not appointed via the Identified Position policy, but “...at the discretion of the University”. The university has commented that while “not typical”, these appointments are “not uncommon”, noting that there are more than 10 Professors in the Practice at ANU.

They have highlighted that the justification for the hire is strongly rooted in Brandis’ extensive professional experience - political and diplomatic - making him “...amply qualified for the role.”

In his political career, Brandis was involved in several controversies, including the 2013 approval of an ASIO raid on the office of East-Timor representative Bernard Collaery, and the use of $20,000 of taxpayer money to build bookshelves for his parliamentary office.

Brandis also asserted, in relation to accusations against Andrew Bolt of racial vilification, that “... people do have a right to be bigots.” Online, the ANU states that “We do not tolerate or accept any form of racism or bigotry.”

While the FOI documents make reference to a donation to the University to create a Professor in the Practice position, the ANU has since confirmed that Brandis will be paid not from a donation but from central administration’s budget.

ANU is also entitled to hire without advertisement under an “exceptional case” which includes hiring by invitation, although approval must still be sought in writing to Human Resources under clause nineteen of the procedure. This writing, if it exists, is not included within the FOI release which covers documents “...related to the appointment of George Brandis as a professor at ANU” including “...contact between Mr Brandis and the University regarding any employment opportunity.”

For students, the FOI raises the question of whether the ANU hires high-profile professors for the benefit of the University’s finances and lobbying. It remains unclear which employment policy the ANU used when hiring Brandis beyond its own discretion.

The FOI also highlights the power of the Vice-Chancellor to personally fast-track appointments, at a time when the revolving door between politicians and public appointments remains a

8.

9. Art by Xuming Du

"Without Protests, We Have Nothing" - A Look into ANU's Student Activism Raida

Chowdhury

Content Warning: Oppression, misogyny, homophobia, racial discrimination, sexual assault and sexual harassment (SASH) and police discrimination

On the 19th of April, 1965, Prime Minister Robert Menzies announced the deployment of Australian combat troops to Vietnam. In July of the same year, 800 students attended the first ever teach-in protest at ANU.

In a 1968 edition, Woroni would later recall, “Menzies announced that Australian troops would be sent to Vietnam and the first of the huge ANU demonstrations began. It was rapidly being realised that the ANU’s position in the heart of the National Capital afforded an instant and massive press coverage to the activities of the ANUSA and our impact upon world events assured.”

Throughout the years, ANU students would channel the same enthusiasm for activism. By 1976, after months of demand and protest, the University offered the first Women’s Studies course. In 1978, Women’s Officer Gaby wrote in her Officer’s report, “I hope campus activists realise how difficult it is for women to do anything worthwhile—because as soon as we hit the scene we’re attacked”. Feminist activism would remain resilient, since the next year saw “Wimmin on Campus”, the first feminist club being established.

In 1989, the Hawke government introduced the Higher Education Contribution Scheme (HECs) and the National Union of Students launched the first of many campaigns against it. The Tjabal Indigenous Higher Education Center opened the same year. The ‘90s would see campaigns against increasing fees and

course cuts and the first ever pro-choice awareness campaigns held by ANU Women’s Officer Kate Harriden.

By the 2000s, students started protesting against refugee camps and established the ANU Refugee Action Collective. A student declared in a Woroni opinion piece, “The protests have begun. They will escalate and they will continue until all refugees are free.”

In the 2010s, student activism steered towards environmentalism and pride protests. After 500 pride posters were torn down on campus, students from the Queer* Department dressed in camouflage and staged a stakeout to defend and re-decorate posters. In 2013, the Fossil Fuel Divestment campaigns began and by 2014, after protests and campaigns, the ANU partially divested from the fossil fuel sector.

In recent years, the ANU student body participated in an average of seven protests each year. Protests regarding the University’s management of courses and student wellbeing, organised by ANUSA departments, tend to have the highest student turnout. Woroni spoke to Women’s Officer Phoebe Denham (they/them) who explained, “Activism is integral to the role of Officer. It ranks highly (with service provision) since community work and activism go hand in hand.”

10.

Art by Jasmin Small

They also revealed that historically Departments autonomously select protest issues and political actions, while the ANUSA executive provides logistical support to the initiatives, including financial aid and resource provision, such as first-aid. Departments often organise protests that relate to student wellbeing issues, including protests against campus racism and sexual assault and harassment (SASH), usually inspired by Department reports. However, this can lead to burn-out amongst Department staff. At the final SRC last year, many Department Officers condemned the workload and burnout that autonomous activism can cause.

ANUSA Education Officer Beatrice Tucker (they/them) acknowledged that ANUSA has lacked a whole-of-union approach to activism and has “attempted to solve issues bureaucratically, behind closed doors in meetings with [university] management, rather than through popular support and activism.”

On-campus groups, such as Socialist Alternative, often organise on-campus protests, including protests for climate action, such as the National Day of Action. The National Union of Students (NUS), which ANUSA is affiliated with, also organises protests on issues such as climate change and abortion rights. Protests against course cuts are organised by the college students themselves in conjunction with the ANUSA Education Committee, such as the protests against CASS program disestablishments last year.

Mass advertising of campaigns and the effort of organisers both help to increase student turnout. An ANU student who attended the 2023 Invasion Day protest and the International Women’s Day protest told Woroni, “There are always posters around campus for upcoming protests and…emails from ANUSA [with invitations] to join protests.”

Phoebe explained protests can be inexpensive with the main costs being posters and banners. However, the labour can be taxing, especially for department officers who spend time organising protests. Beatrice told Woroni, “I had been working with my classmates for

the School of Arts and Design (SOAD) for 18 months…raising expectations for what is possible, regularly discussing similar fights and successful organising campaigns.”

The SOAD had three years of closed workshops and online attendances, even after the ANU and ACT government both lifted restrictions. After a three-day sit-in organised by the students, at the main foyer of SOAD, SOAD management allowed students access to low risk studios on weekdays.

Student activism has increased in the past decade due to accessible organising through social media. However, consequences remain severe. Luke Harrison recalls feeling “unsafe” at a protest against the corporatisation of pride, “The police have a long history of oppressing queer people, and they kept snickering and sneering at us.”

In 2014, then Foreign Affairs Minister Julie Bishop was met with thirty student protestors when she came to speak on campus. The protests were part of a bigger opposition to the Abbott government’s university deregulation initiatives. Police arrested three students despite protesters claiming to be nonviolent and pleading that the broken window of Bishop’s car was an accident. In 2016, ANU students were arrested for blocking a coal train from NSW’s Whitehaven’s Maules Creek Mine, while protesting the climate effects of coal mining.

This year in February, after protesting against the rising cost of housing, the interest rate and bank profits in front of the RBA, Cherish Kuelhmann, a UNSW student was arrested and taken into custody at midnight before being set strict bail conditions. The University of Sydney also suspended students Maddie Clarke and Deaglan Godwin for their involvement in a protest against Malcom Turnbull when the former PM visited the USYD campus. ANUSA’s first Ordinary General Meeting of this year echoed concerns of whether similar circumstances could occur for ANU student protestors, as a motion calling for ANUSA’s support for the two students passed unanimously.

11.

Although peaceful protests are not illegal, police can arrest students with charges such as obstruction, trespass, offensive behaviour and property damage at protests. Arrest records can be detrimental to a student’s career, since many jobs require police clearances. Graduates may find they are denied opportunities, promotions, or are subjected to prejudice for their arrest record. This is of particular concern at the ANU, where many students seek to work in fields requiring government clearance. For international students, arrests can lead to the termination of visas and deportation.

According to the Australian Human Rights Commission, Indigenous Australians are 17.3 times more likely to be arrested than nonIndigenous people, especially in situations with assault occasioning no harm, such as offensive language or resisting police arrest. These are charges often used to make arrests at protests. Attending protests also threatens individual anonymity as Denham explains, “It’s scary stuff (to see) photos of other people at protests (and) seeing yourself.”

In light of such statistics, the ANUSA/ANU Law Reform and Social Justice Legal Observer program launched at the Invasion Day protests this year. The program involves training by staff from Legal Aid ACT to observe interactions between protestors and police enforcements at protests and detect any encroachment on the right to protest.

Trained lawyers and students will attend protests to observe and report the conduct of police and private security. Luke Harrison also explained, “Police Liaisons who are [at protests] are trained to engage with police on behalf of protestors and Marshalls who are trained to direct the crowd away from dangers and in directions of the protests [are also present]”. Departments have also requested protestors to wear face masks at protests, for health reasons and to anonymise identities. The Women’s Department also co-operated with SAlt to organise a long distance, bird’s eye camera for the International Women’s day protest.

Despite challenges, student activism is at the core of students and departments. An ANU student told Woroni they attended protests because, “It was invigorating and you feel like you’re a part of something very powerful. The chants, the posters, the walking together, it feels like something bigger than life.”

Tucker compares student activism to “detonators of success,” saying student activism provides, “students with tools to take with them into the future to fight [for] their own rights as workers.” Denham stresses the importance of “showing up when you can,” for students who cannot attend protests. They explained, “I feel a lot of solidarity with other students and I know I have the student body behind me.” An ANU student protestor emphasised, “Without protests, we have nothing. Changes may not be tangible and visual yet, but protests are the only way to create change.”

If you or anyone you know is affected by the content of this piece, please contact one of the support services below:

Beyond Blue

1300 22 4636

24/7 – Depression, anxiety and suicide prevention

1800 RESPECT

1800 737 732

24/7 – National sexual assault, domestic and family violence counselling service.

Editor’s note: the history of student activism listed here is not comprehensive. For a more in-depth timeline, refer to the ANU website, Woroni archives, Marie Reay wall and the banner along the BKSS railing.

12.

13.

Art by Max Macfarlane

Art by Jasmin Smal

Charlie Crawford

In his desire to maximise efficiency within the prison system with minimal guards, Jeremy Bentham settled on a structure that he would call the ‘Panopticon’. A central tower of guards surrounded by a ring of prison cells facing inwards, Bentham argues that prisoners begin to discipline themselves under the idea that someone could always be watching – to the point where the guards needn’t be. Over time, what was simply a model of efficient prison management, has become a symbol for the never-ending expansion of infinite measures of social control. In the same way that you stop at a red light even when no one is around, society has normalised these mechanisms of selfregulation that you don’t even notice you’ve made a habit of.

Whilst some look more prison shaped than others (sorry Ursies), it’s hard to ignore the similarities between Bentham’s panopticon and the social dynamics of living at college. There are very few other scenarios in life in which you will live in a fun little Soviet-esque commune of 300+ people all within 100 metres of one another. It’s almost a given, then, that you begin to make observations about the people that you see everyday. First, you’re intentionally trying to learn more about them, then you’re naturally picking up what they talk about and how they do it. It slowly becomes more personal as you learn their mannerisms and quirks, until all of a sudden, you’re an expert at reading their body language even if you didn’t intend to be. College forces you to speed-run relationships.

14.

This has its benefits. I know Jess is having a bad day if she turns down an offer for tea in the dining hall; I know Harry has classes all day Tuesday because that’s the day he’s not at lunch. But it also presents its own very unique set of disadvantages. The eventual realisation of how well you can understand the people around you leads to the inevitable conclusion that those people are also seeing you under the very same spotlight. The knowledge that at any one point, someone can understand or recognise you in ways that may forever remain unknown to you is terrifying. This is only compounded by how fast information can travel – share good news with your best friend – people you’ve never talked to before will be congratulating you at dinner. Share bad news…you get the picture. Hyper surveillance is puppeteering our interactions in a way that means all our conversations revolve around each other.

This keen awareness of just how perceived I am at any one moment has made me feel as if I have to be a perfect version of myself every time I open my door. I’ve become a person that almost demands others to know how put together I am. I portray a version of myself that I hope will be the most interesting and entertaining to those that are watching me and reflect favourably upon me as it inevitably gets passed down the gossip chain – if I slip up, the guards will notice. In an environment in which everyone is acutely aware of what everyone says and does at any moment, I’m determined to make sure people only see the version of myself that I want to put out there. Because if I do that, then I’m beating the panopticon, right? I need to have total control over the narrative people have about me, because now that I’ve gotten ahead of it, I can make sure it’s only the good stuff. Right?

I worry about what this surveillance is doing to me. Am I just tolerating it, or have I begun to ask for it?

I lap up the attention as I walk to work in my brand-new corporate chic attire (I intentionally loitered around at breakfast so people could see how responsible I looked). I mock TikToks of people videoing themselves doing good deeds (I hope that none of mine go unnoticed). It could be easy to throw away the real weight this Orwellian lifestyle can have on you, file it under “exhibits narcissistic tendencies’’ and move back onto gossiping about other people. Yet I can’t help but worry about the way this mask I’m wearing might become permanently welded to my face. More importantly, I don’t know what’s scarier – the thought that my friends can’t see through it, or that they can.

In the never-ending performance that is living at college, how is anyone supposed to feel seen when we’re made to enjoy the ordeal of keeping up appearances? I want to feel as if my relationships with the people around me mean something – like they know me – but how can I ever be sure? How can I be sure what knowing me even looks like? College is a perpetual balancing act of attempting to put on your best performance of yourself, whilst also wanting to maintain some semblance of authenticity. Are we all just patchwork caricatures of the traits we think people will find the most interesting about us? Isn’t there, too, some sincerity in that.

15.

Art by Jasmin Small

Repression, Respectability, and the Right to Protest

Carter Chryse

The author of this piece is a member of Socialist Alternative ANU

16.

Art by Jasmin Small

The last peak of protests across Australia is now some years behind us. Across Australia, the ruling class is now taking the chance to hit back.

The climate movement of 2019 and early 2020 was huge. Hundreds of thousands attended School Strike protests in late 2019. Extinction Rebellion protesters shut down traffic in major cities across the country week after week, and promised there was more to come. More than a hundred thousand rallied during the bushfires which choked Eastern Australia in smoke, calling for the sacking of Scott Morrison.

There was a frenzy of op-eds calling for calmness, politeness, respectability, getting off the streets and calling your local member. But in the face of hundreds of thousands across the country participating in loud, rowdy, angry protests, the protestations of the establishment weren’t much more than words on paper.

That’s changed now. With the ebb of the climate movement, brought to a halt under COVID-19 and now struggling to rebuild under the federal Labor government, there’s been a slew of attacks against protesters. Victimisation of all activists who dare to disrupt business as usual is climbing. I want to highlight three cases.

The most outrageous and high-profile of these is the charges placed against Violet Coco. Violet, associated with an Extinction Rebellion offshoot group, stopped a single lane of traffic on Sydney Harbor Bridge for less than half an hour. For this supposedly heinous crime, she was arrested, intermittently placed under house arrest on remand, and originally charged for 15 months with thousands in fines (the charges and penalties were dismissed on appeal). She was charged on laws introduced in NSW in 2020, which sought to punish those who block major roads or the like with up to two years jail time and/or $22,000 fines. These laws were introduced directly to intimidate and repress climate protesters blocking traffic, some tens of thousands of whom had occupied the Sydney CBD just months earlier. Awaiting trial in Brisbane are twelve other Extinction Rebellion protesters, charged with blocking roads there, where similar anti-protest laws have been in place since 2019.

It’s in the context of the ebb of the climate movement, the distaste for such disruption by the respectable establishment and sections of the protest movement, such as the organisers of School Strike for Climate, that the state feels emboldened to hit back against protesters. However, the right to disrupt and impede the very ‘business as usual’ approach that is killing the planet should absolutely be defended. There is no similar jail sentence or fine for those fossil fuel bosses who are causing the climate crisis, which is responsible for blocking the roads with floods in Lismore or bushfires across 20 million hectares in 2019. The only criticism to make of the stunt-based tactics used by Violet Coco and others associated with Extinction Rebellion is that they should be focused on drawing as many people as possible out onto the streets with them.

17.

by Vera Tan

This year, also in NSW, was the case of the arrest of Cherish Kuehlmann, a Socialist Alternative education officer from UNSW. Kuehlmann was dragged out of her home at midnight and charged with aggravated trespass – for protesting outside the Reserve Bank of Australia for about 15 minutes. Neither Cherish nor her fellow protesters at a cost of living protest in February ever entered the Reserve Bank. The charge was considered “aggravated” as it “disrupted the flow of business” for the 15 minutes – as Cherish said, “apparently, [sic] I’ve supposed to have stopped them from raising interest rates further”. When she was released on bail, the cops tried to implement restrictions to prevent her from attending protests at Sydney Town Hall, in a clear attempt at intimidation and an attack on the right to protest. These were ultimately overturned, as there does not (yet) exist any law preventing people from coming back to protest.

The laws Kuehlmann was arrested under were introduced in 2016, specifically to target disruptive climate activists, so it’s no coincidence they’re being employed in this recent suite of attacks. The calculation that is being made by NSW Police and the state is the same: without a movement and the full support of the left for disruptive protests, such laws can be used to victimise activists without backlash. Their judgement was largely correct: in an appalling turn, the UNSW SRC, of which Cherish is Education Officer, voted against a motion calling for the charges to be dropped against her.

Lastly, I want to go to the example of the suspension of two members of Socialist Alternative from the University of Sydney. Former University of Sydney Education Officers Deaglan Godwin and Maddie Clark were suspended this year for their part in leading a 2022 protest against former Australian prime minister Malcom Turnbull’s appearance at an event at the university. They were charged with infringing on Turnbull’s freedom of speech by disrupting his event for a few minutes – and “making him [...] afraid.” Turnbull called the disruption “fascism” and a “dreadful state of affairs”, and university administration backed him. Deaglan was suspended for 6 months and Maddie for a full year.

University administration is distinct from the government of NSW or Queensland. But the judgement is the same: unacceptable infringements such as students exercising their democratic right to protest will be pushed back against when the university feels secure that there will be no fightback. Again, ebbing protest movements have encouraged repression.

Surrendering to intimidation to dissuade the conduct of rowdy protests is the highest form of self-sabotage for those who would fashion themselves as activists. Of course, the first victims of anti-protest repression are those who block traffic, glue themselves to roads, and block the Reserve Bank. But any concession on these grounds, that perhaps we should be less objectionable, quieter, more appealing to the state – is a concession against the right to protest at all.

More broadly, even where there is rightful outcry against these repressive measures, it’s not big enough. Many scornful columns were written about the treatment of Violet Coco, the other Extinction Rebellion activists, and even about the suspension of Deaglan and Maddie. There were counterprotests, supported by sections of respectable society like the Greens and NGOs.

But overall, this is not enough. We’re now in a situation where protests are being painstakingly rebuilt, in gatherings of 50, 100, 150 protesters – not thousands or tens of thousands. The way to fight back is not to concede the point of aiming for more respectability. It’s by having too many of us engaged in protest to be able to repress in the first place.

18.

Opposing art

19.

20.

zthi Art by Jasmin Sm all

supremacy of markets.

I thought I was correct. Right up until I had to study the economics courses that form the final, pretentious syllable of PPE. Because there is something seriously flawed both in economics as a field and in how the ANU teaches it.

I do not know how the College of Business and Economics likes to brand the economic ideology of its professors, but I struggle to find how it differs from neoliberalism. I distinctly remember learning in my first Microeconomics class that humans are rational individuals, who always reason through their choices and who always choose the option that maximises their utility. From here, we steadily built up models to show us how markets work most of the time, and when they didn’t, we learnt why government intervention was risky.

Then we studied Macroeconomics. Because my lecturer made reference to Thomas Piketty – a French economist whose writing explores a third economic model between socialism and capitalism – I thought this would be better. Yet, we still fell into similar pitfalls. Climate change was an externality which taxes would internalise, not a reflection of the fundamental problem of an economy that must grow to survive on a planet that cannot ever accommodate it. I lost all hope when we learnt why some countries have different levels of economic growth. The explanation did not stop, nor begin with “Because some (Europe) enslaved and colonised the others” and was instead chalked up to different levels of capital. A neat way of hiding the centuries of plundering, violence and literal exploitation required to build a Eurocentric economy. I asked the lecturer about this once; he said that we had to draw the historical line somewhere. Convenient place.

None of this is new. I have not re-invented the wheel. But when life meets the expectations that everyone and everything set for you, it can still be annoying and disappointing. And I think that while we study at the ANU, it is still worth talking specifically about what we learn. To beat the dead horse, economics matters. Almost every political crisis we face has an economic dimension. From the victories of the far-right to tensions with China or to the ongoing oppression of First Nations Australians, none of these problems can be solved without engaging with the economy.

But the teachings of the CBE will draw the line, arguing that, at some point, economics stops even though capitalism insists the world keep on turning. Real economics, that puts the person, not their utility, first, can interweave ethics, history, environmental science and politics. It helps us better understand the world we live in, and to solve our distribution and production issues. I am going to go ballistic if I see another supply and demand diagram.

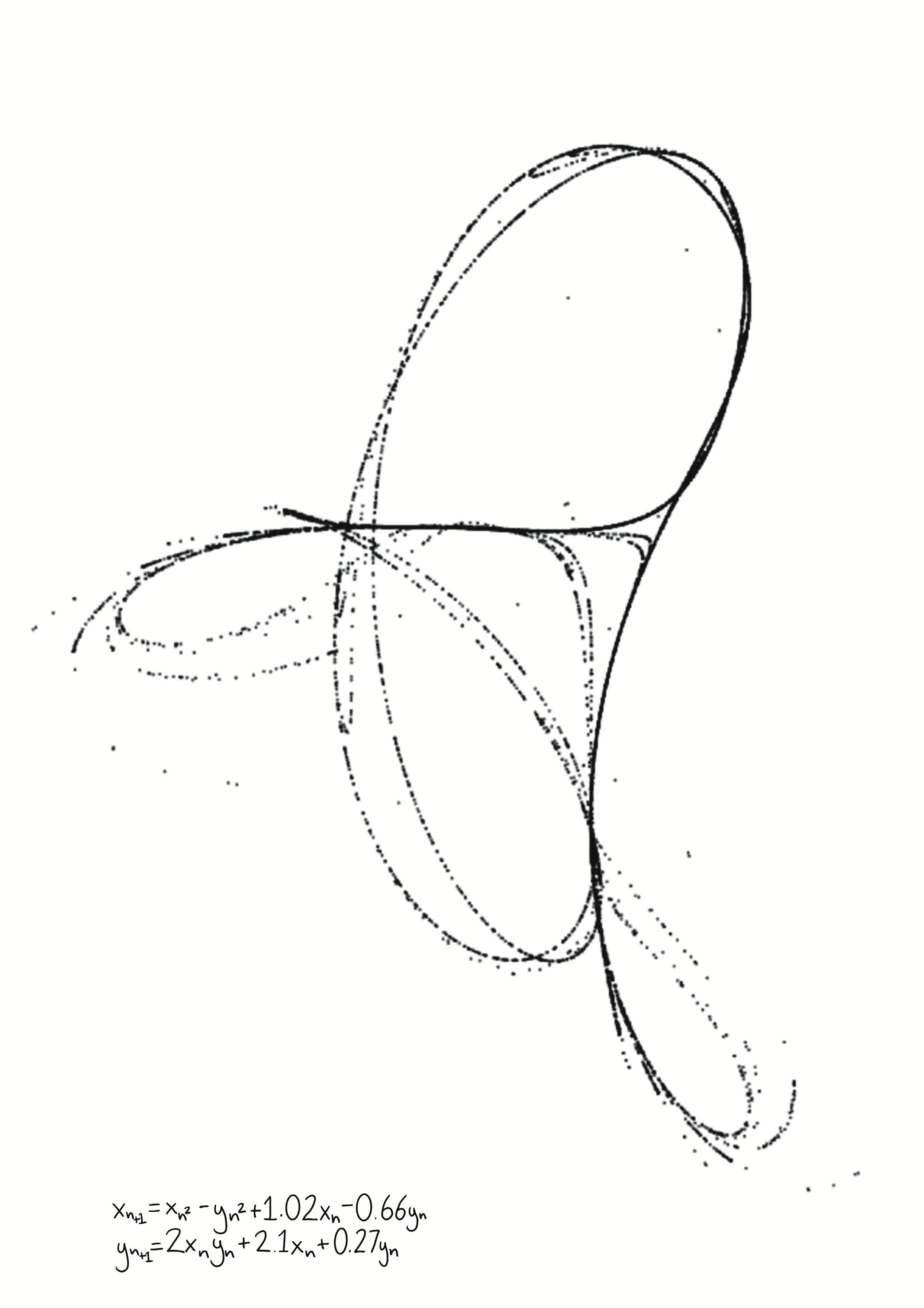

The major problem I see – as a completely unqualified undergraduate – is the inability of the CBE to teach heterodox economics. Heterodox teaching, broadly, means to teach multiple theories and perspectives, not just conforming to one. Eleanor Ostrom is a Nobel laureate economist who pioneered key ideas in the school of institutional economics, arguing that solving collective action problems requires context-dependent solutions, not the blankets of neoliberalism or socialist thought. I learnt about her in a politics class, then again in an environmental studies class. Never did I hear her name in economics. Piketty – the Frenchman mentioned above– has created a statistical hellscape to show that the only other time the world has had so much wealth inequality was on the eve of World War 1. Daniel Kahneman has demonstrated empirically that humans are irrational creatures who cannot compute their own utility, or even straightforward questions of probability. I learnt about him in a politics class as well. The CBE teaches one single vein of economic thought: the simplest.

This neoliberal vein has become a force for the rich and the powerful, an incredible means to stop any true reform of the economy. It does this by creating a theory and a model of the world that renders socio-economic issues inexplicable. The debates had in an economics classroom are locked in the context of the 1980s. Inflation is chalked up to demand in the economy – even though research shows this isn’t true in the modern economy – and that demand is blamed on consumers, even as report after report finds that company profits are driving current inflation. Each new issue, no matter how much it shows that profits are antithetical to human and ecological interests, gets tacked on as another externality. Until you have some lumbering, Frankenstein-like model of the world in which the supposed good of the market is hidden beneath each example of market failure that just somehow happens to nearly all markets.

There are countless other problems with modern economics and the CBE, but heterodoxy is the starting point. It would include embracing the historical nature of economics, allowing students to see how the modern world is built off racism and colonialism. It can also help pull economics away from its physics envy, to talk more about the economy as a system and to talk about the system that underpins the economy: the environment. It’s not a silver bullet, but by god it’s somewhere to start.

It may feel mean and short-sighted to single out the CBE and it probably is. Most Western economics departments have fallen into the same trap, and some have it far worse than the ANU. But I would like to tell my dad that I’m not a Tory, so can we not just talk about something new for once? I would encourage the CBE to think about the ground-breaking researchers they quote, the Pikettys and the Raworths. Understand that you can start teaching students those concepts now. That students need to learn older concepts before they learn new ones is a convenient lie for instilling the old ones and painting the new as novel and unproven.

Yet, at the end of the day, the CBE, like all colleges, must produce graduates ready to enter the workforce. After all, what EY partner wants a grad who actually thinks?

For the other PPE students out there, I can only recommend ENVS2007 - Economics for the Environment by Rebecca Pearse. Our current exalted convenor will let it count as economics. It really is a breath of fresh air, before we run out of that too.

22.

Leading SAlt Member Says Campaign Complaints "Overblown"

Luca Ittimani

Socialist Alternative (SAlt) member Wren Somerville has defended the faction’s reputation for belligerent campaigning as essential to the work of anti-capitalist activism.

In an interview with Woroni, Somerville claimed that criticism of SAlt for its style of campaigning is disingenuous and is fundamentally due to “political disagreement”.

“Some people are put off by our politics and don’t like us and are not for socialists organising in an open, active way,” he said. “What it comes down to is actually an argument against socialists.”

Somerville, who has been with the political faction for five years, claims the method is essential to finding sympathetic students and prospective members.

“If someone’s like, ‘I want to find the socialists on campus,’ they know where to look,” he said. “It would be, I think, a horrible thing if people … didn’t find socialist politics because people felt too worried about, like, doing leafleting on the street [and] trying to stop and talk.”

But the club regularly comes under fire at ANU and across the country for its campaign style. Education officer for Australia’s National Union of Students (NUS), Xavier Dupé, last year fended off questions from NUS officers over accusations that SAlt members have disrupted autonomous spaces and leafleted students while waiting in line for food.

Additionally, despite the historically left-wing nature of students, SAlt tends to be a smaller faction across most university campuses, although they have grown in size over the last few years.

In March’s ANUSA student representative council meeting (SRC 2), right-wing general representative Anton Vassallo suggested that SAlt members had harassed ANU students in their campaigning, which SAlt members strongly denied, saying the accusation was disrespectful to victims of harassment.

23.

Art by Jasmin Small

“If any one of our members was harassing people, we would obviously take it very seriously,” Somerville said. Other students have previously criticised SAlt as being a cult-like organisation. In a now famous essay, University of Sydney Grassroots member and former USYD SRC President Liam Donohoe accused SAlt of recruiting him with cult-like strategies.

The organisation dismisses the idea that its style of activism is viewed as invasive by the student body.

“Most people who come across us on Uni Avenue don’t find us super belligerent,” Somerville attests.

He attributed SAlt’s aggressive reputation to exaggerated accounts of negative interactions posted by irritated students on social media pages like Schmidtposting and ANU Confessions, saying that “stuff kind of gets overblown in online spaces”.

Somerville encouraged those uninterested in engaging with SAlt’s politics to end the conversation. “We’re not mind-readers [but] if people do give very clear indication that they’re not interested, like they say, “no thanks” or if they leave, then that’s that,” he said.

“We’re not trying to waste our time.”

SAlt is politically centred on revolutionary socialism and the theories of Karl Marx, with a focus on preparing and furthering revolutions when they arise.

“We don’t think that our group will, like, start the revolution,” says Somerville. “The condition of capitalism is what creates revolutions…but the thing that we think is important is having a group of people who are organised around the politics of those revolutions going as far as possible.”

But with protests on decline in Australia and no revolution in sight, SAlt focuses on finding and preparing the activists who will push for change when the moment arises.

Somerville says the organisation aims to “reach those people who feel like, ‘something’s wrong with the system, I need to do something about it right now,’ and … convince them that our political orientation is the one that they should be involved with”.

SAlt’s prioritisation of protest extends to its presence in ANUSA’s SRC, where it is sceptical of efforts to expand service delivery and instead pushes the student union to support activist causes.

SAlt-affiliated representatives at SRC 2 claimed education officer Beatrice Tucker was providing insufficient support for the NUS-pioneered National Day of Action climate protest, which Tucker denied.

24.

Art by Jasmin Small

Somerville has called for ANUSA to leave service delivery to the university and put all its funding towards activism.

“I don’t think that the role of a student union should be service provision,” he said. “I think the majority of [funding] should go to campaigning and activism and fighting for students’ rights.”

He insists the union’s provision of benefits such as food, grants and subsidies “lets management off the hook”.

“It would be an embarrassment for the National University if students were all starving or dropping out because they couldn’t afford food and had to work,” Somerville said. “We should fight for university management to put some of their massive surplus into providing services for students”.

This analysis of campus service provision resembles Marxist theorist Rosa Luxemburg’s view of early 20th-century capitalist economies. Luxemburg claimed that government provision of services and income support to workers masked their exploitation by their employers and discouraged them from revolting. She believed that, without government provision, workers would be forced to work excessive hours to survive amid worsening living conditions.

Luxemburg further called for governments to stop providing support for workers, believing that worsening conditions would drive workers to protest against the elites and establish a new world of prosperity. SAlt claim they do not advocate for ANUSA to stop providing services, and instead merely advocate against student-funded bodies, such as the union, being responsible for providing this support, however they routinely criticise ANUSA in meetings for providing such services.

Most SRC members are committed to providing services for ANU students, so SAlt’s ANU revolution appears to be deferred indefinitely, awaiting popular support.

But the organisation’s radical politics, which Somerville acknowledges attracts only a “small minority” of students, and its enduring image problems suggest that the necessary support base is unlikely to be forthcoming.

As a campus-politics-obsessed 21stcentury Marx would say, the dehumanising conditions of corporatised education will inevitably produce mass student protests. If this arises, SAlt will have to ask itself whether pushing protest “as far as possible” will deliver the utopian outcomes it desires, or whether its vanguard position will alienate the bourgeois undergrads who just want a night cafe.

25.

Art by Jasmin Small

26. Art by

Jasmin Small

27.

Art by George Hogg

by Hassan Alanzi

British Strikes and the Return of the Working Class

Nick Reich and Chris Morris

The United Kingdom’s recent strike wave is a shining example of workers’ continued power and strength in advanced capitalist countries. Working-class living standards, confidence, and combativity have been pushed back by neoliberal governments and aggressive employers. Union membership and days on strike have declined so steeply that a generation of workers has no experience of strikes. The British strikes are pushing back those trends and encouraging re-engagement with theories of workers’ self-emancipation such as Marxism.

The return of the working class

The modest uptick in strikes since 2020 gained momentum in June last year when the massive National Union of Rail Maritime and Transport Workers (RMT) initiated rolling strikes over a pay dispute. Rising energy prices, food prices and employer attacks on working conditions in key workplaces fanned the flame, driving the spread of mass strikes across other industries. Tens of thousands of workers in areas including telecom, postal, oil, healthcare and law have gone on strike.

Since then, strike action has ebbed and flowed, notably dipping during a moratorium following the death of Queen Elizabeth. But the crucial nursing sector has continued to drive strike action this year, with February’s nurse strikes the largest in the history of the British National Health Service. Rolling strikes from some unions continue at the time of writing.

Why does this matter?

Disputes and events like this enhance the organisation and the confidence of the working class to use the strike tactic. Public support for organised labour action has been stubbornly high despite the disruption caused by these disputes. Historically, strike waves have dramatically increased union membership and participation.

The current wave follows recent increases in union membership in Britain, signalling workers’ greater willingness to organise and stop production to extract better pay and conditions from their bosses and the government. Production is

central to capitalist society, so workers’ power is immense. When they win battles in their workplaces over issues of basic economic survival, this can pave the way for workers’ power to be used in fights over broader social justice issues or other political questions. Polish Marxist Rosa Luxemburg’s pamphlet “The Mass Strike” highlights how strikes over economic concerns can transform into political strikes and shape their participants into more politically conscious people.

The British conservative government is aware of this potential and fears it. They are pushing for authoritarian laws that would prevent strike activity and limit its legal organisation, while making it easier for employers to replace workers during strikes. They have also cynically and maliciously introduced the so-called Rwanda solution, modelled on Australia’s offshore torture of refugees, in a move that has driven racist scapegoating of

28. Art

When workplace-specific issues spark public class conflict, politicians and state bureaucrats defend the interests of bosses by whatever means necessary. Governments in liberal-democratic countries like the UK will go as far as winding back democratic freedoms and scapegoating the most vulnerable in society to crush protest. British workers have rightly rejected these divisive politics by blockading attempted deportations of refugees and migrants, and holding mass anti-racist demonstrations across the country.

If it can happen there…

The scale of the economic crisis in Britain is immense. Inflation has remained stubbornly around 10% for months, with energy prices particularly high due to sanctions responding to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The country last year experienced a rise in excess deaths, to 20% above the five-year average, after its health system was driven to the brink by long-term underfunding and the COVID-19 pandemic. Survey analysis over December 2022 and January 2023 found that almost 90% of food banks were facing increased demand. But these crises have precipitated resistance from workers, not just submission.

Anxiety over economic pressures is higher in the UK than in Australia, but Australia is not immune from the cost of living crisis impacting workers worldwide. Australian workers have suffered a massive drop in real wages over the past few years, which will only fall further in the short term. Under these conditions, workers’ resistance will almost certainly be resurgent in this country, similar to what we’ve seen in the UK, which would be an immensely positive development.

It is not an act of faith to defend the politics of class struggle and workers’ self-emancipation in a period where strikes and union membership are at an ebb. It’s a recognition that workers’ resistance hasn’t been fully defeated by the neoliberal offensive. Nor are workers invariably narrow-minded, apathetic, prejudiced or selfish. The British strikes show that the working class can still be a powerful political actor in advanced Western economies. They show that workers defending their living conditions isn’t just an economic question but a political action. The British strikes show that workers can fight and win.

29. Art

by Jasmin Small

30.

31.

Art by Fuz Buckley

Power, Unions and Networks of Care: an Interview with Student Ben Wyatt

Interview by Elizabeth Fewster

Ben Wyatt is undertaking the Master of Philosophy at the ANU. His research looks at union organising in the modern economy.

Ben and I spent a challenging year together doing our Honours theses at the University of Melbourne, amidst never ending lockdowns. We got to know each other and our research interests over long hours in the library, zoom writing sessions, and (when permitted) many stress induced pub sessions. I sat down with Ben to chat about the research he’s kicking off soon.

Hey Ben, thanks for sitting down to chat. Can you tell me a little about the research you’re doing?

Well, I haven’t done it yet, so I’m not sure where it’s gonna go. But the idea is that, historically, the economy has functioned because material things were understood to have value, and because of that, workers were able to say either “ we create this thing” or “we helped created this value”. Either way, their refusal to work was an effective way of leveraging that power. So in that context, unions became one form of labour organising that was relatively effective, and it helped working people to get political rights.

32.

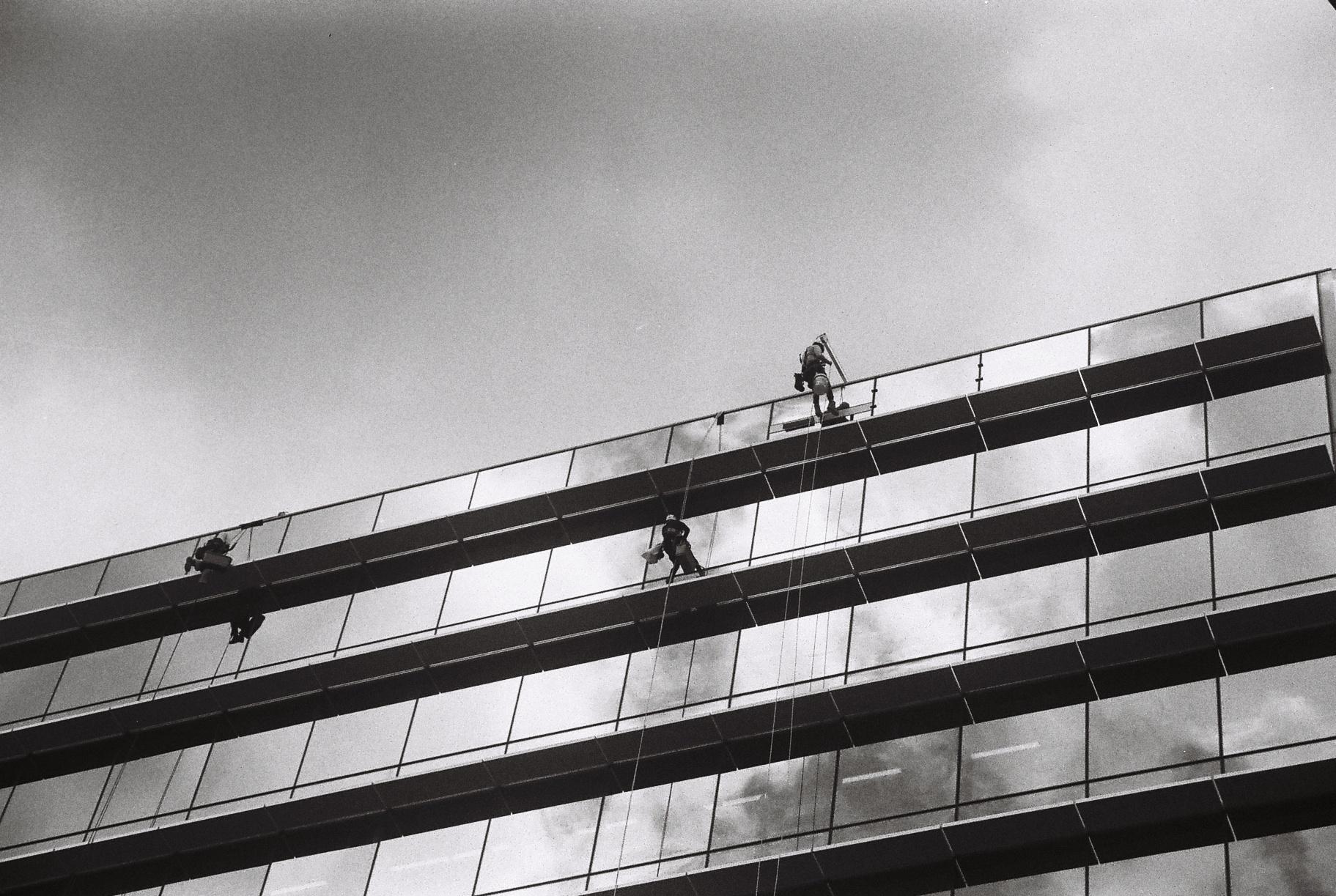

Photos by Hima Panaganti

The economy is very different now and things don’t seem to have value in the same way. Now value is more symbolic and it’s more driven by speculative systems than material goods. So the question is, what is the value of labour in this new context? But also there’s a political question, about what it means for people who labour to gain political power, through their labour, in this new economy.

What do you think has changed from the inception of unions to now, that makes you sceptical that workers’ power isn’t seen the same way? What do you think has changed?

You can see it in a lot of different facets, but fundamentally things have become more abstract. For example, in Melbourne when there’s a protest, you either meet at the State Library, and protest there, or you walk to somewhere else, so there are certain avenues where you protest, they disrupt traffic to some degree, but the ritual of protest is domesticated.

For the people protesting, it’s a statement, right? They get to externalise that they’re doing something, but it’s not an exercise of power, because the powers that be - the government, corporations, whatever - they’re allowing it. Whereas the significance of a strike historically is the workers are showing through their actions that “you may own this factory, but we’re the ones creating its value, so we are going to get what we want”. I think that, especially for young people today, for all of our engagement with politics, things are very symbolic. We’ve sort of lost that way of thinking about how to exercise ourselves politically. So young people, we’re concerned about climate change, but what do we, as our generation, have that we can mobilise to get what we want?

So obviously there’s a judicial impact on how we can protest. What do you think about Violet Coco who was originally charged with eight months in jail for protesting and holding up the Harbour Bridge for 20 minutes?

Personally, I think it’s important that we strike, but for me, it’s more about civil disobedience and how you gain power. Constitutionalism is important, it’s important that there are rules to society. But I support civil disobedience, for example, the Harbour Bridge person, I support their right to protest and I think what they did is good. But the issue is that it’s still symbolic, right? Even if they’re actually being disruptive, and even if they get a heavy court case thrown at them, at the end of the day, whether they are arrested or they go home, it’s over, it’s an event, it’s a spectacle that comes to an end. It’s not forcing change in the same way.

This is the thing about the broader economy: seventy years ago if a factory shut down, the supply chain would be disrupted and the people that owned factories would be upset because their profits would be hampered. But today that profit isn’t driven by production, so, for example, even if workers shut down the factory to a standstill for a year, profit was driven by speculation on the company that owns the factory, not the goods that get produced.

What do you mean by speculation?

So speculation has a lot to do with credit and debt. Mortgages are a great example of this, we expect that properties will always gain in value. So you take a mortgage out on a property, pay down the mortgage on the expectation that the asset will be worth more when you sell it. People don’t just buy houses to live in anymore, they also buy them as investments. So homeowners support policies which continually push up house prices. New homeowners might be able to still buy a house, because even if their mortgage is expensive, they expect the house will be worth more in the future. So now they also have to support the same policies. All the while, their house was overpriced to begin with, and the longer this carries on, the greater the catastrophe for most homeowners if and when the bubble pops.

So speculation is both the idea that these sorts of assets will keep growing in value, and that that growth is normal. Beyond this pushing more people into insecure housing, it also changes the meaning of housing in society. Housing is a material need, but that need comes up against this financial structure that frames housing not as a need, but as an avenue for profit. Your right to shelter is pitted against my right to profit. But because speculation says profit is guaranteed, and a lot of people have bet a lot of money on it being so, your rights are now a privilege. But more importantly, we’re seeing a massive widening of inequality in society between those who have inherited property and those who haven’t.

33.

But in the broader economy, what speculation means is that investors aren’t saying “you’re creating a useful product, let me invest” or “you’re producing more efficiently, let me invest”. Instead, investment in society and the economy is flattened into short term returns and gambling on stock prices.

You said you support civil disobedience, that you would like to see the ability for people to practise civil disobedience more widely. What does that mean for far-right groups protesting such as those we just saw in Melbourne?

There’s two types of fascists. There are the leaders, and then there are members. In almost every situation, leaders of fascist movement, whether they admit it or not, just want power, and they will do whatever they want to get power, and they’ll use the state and the state structures that already exist - and those that don’t - to get power. They should be criminalised. The issue with the members of fascist movements is that they’re there for a reason. If you look at Germany in the 30s, or America and Australia today, it really is driven by economic anxiety, and the problem is that that isn’t taken seriously.

I’m Jewish. My grandfather moved around the world to fight the Nazis. My friends and I have protested them constantly. History shows that the only way to stop Fascists is with physical opposition. Whether it’s the 43 Group or today’s American antifascists, you can only stop Fascist leaders by stopping any attempt to normalise their presence. So punching Nazis is good precisely because it forces a conversation about violence, a conversation they don’t want to have while claiming they bring security and calmness to people’s lives.

But punching Fascists isn’t enough. You have to find the root cause. If you’re a white working class man, who every day is being fucked over by the economy, and for 50 years or 100 years, you’ve been told “don’t talk about class, talk about gender and race”, or “it’s not your employer , it’s migrants and women taking your job”, that’s the issue. That’s the cause of fascism. The cause of fascism is that there are genuine issues in society and people are given the wrong solutions. Find a scapegoat to protect the status quo, but feel like change is coming. It comes back to structures of power.

So anti-fascism doesn’t begin and end with punching a fascist in the street. It’s about community building and networks of care. It’s a much broader thing about rebuilding a frayed society instead of waiting for the next Fascist march and asking “what should be done?”

What would that look like in practice, community building and networks of care?

Ideally what you need is communities that are marginalised, not just being visible, but developing a public. Politicians and advertisers often talk about or to a public. A sort-of imagined normative community who represents Australia. They are spoken to in the media and in politics, and they’re the people that policy is made for. Marginalised communities developing their own public really means building spaces and discourses that can sustain life, not just moments of protest.

So in my own community, we started a newspaper, we’re trying to foster debate and discussion around important things in my community, and we also run events. We’re soon going to start up mutual aid networks and things like that. There’s a million different things that can be done. But the fundamental point is beginning with the concrete questions like “what do we as a collective need?”, “what structures would help alleviate this?”, “how can we facilitate ongoing dialogue instead of speaking at one another?”

Returning to this sort of grassroots structural stuff isn’t to say that protesting is less important or that things aren’t urgent. But change comes about when people display their power to act. And we can only do that if we can sustain one another. Networks of care are not ready-made models for community, they have to be about the real people in front of you and their real needs. The tediousness of the solutions are important because they unravel our affection for a broken system, and help us to work out what leverage we have to force a change for good.

34.

35.

Art by Max Mcfarlane

by Jasmin Small

sometimes i see a smaller me waving under the filmy surface of the bathwater there are suds clouding her eyes but i recognise her small, sinewed hands grasping out to reach mine and so,

i submerge myself, and i return to her grasp

her glitter speckled nails score deep marks into my skin

i smile.

i guess we still are alike.

the smooth crescent shaped imprints remind me that i am simply half-baked clay

i plead for the sharp pain to mould me

i plead for it to make a new fetus out of my collision of mud but pain slips between the quivering of my own fingers

why does it flee from me?

i put out my hands in front of her again i convince myself i am offering her salvation i convince myself that her power to inflict pain is what makes us similar i convince myself that the pain she causes is life-affirming and my pain is stifling go go hold onto me grip onto my wrists claw onto me and raise yourself from the water dig your nails as hard as you can quickly.

but she doesn’t listen she never does and she never will

her small hands trace the nail marks in my skin

she peppers my hands in tiny kisses she seems worried that she hurt me

but the small red moons that speckled my hands disappear and the small bursts of pain succumb instantaneously to transience

she giggles

i sigh

we go through this every now and then

it’s a pulsating ache that swirls in my gut

why doesn’t she understand this will heal her?

i curl into myself

frantically wrapping my arms around my legs

scrunching up the strands of hair that float in the foamy water

i can’t cry in front of her

i can’t -

36.

Art

her fingerpaint stained palms reach out and she holds my shuddering face she giggles again and her little dimples reach up to her eyes

her fingers pinch my cheeks

she pokes at my dimples and her eyes become glimmering pearls almost as if she’s in awe that we look alike

she reaches for my arm twisting and turning it back to front as if she’s lost something

she shows me her arm and points to a large, bruised scar above her wrist

ah the scar we got from running into a dumpster the first time we rode a bike

i point to my wrist

“it healed, the scar is gone”

she beams we always hated that scar. for a second

i forget that my purpose is to save her for a second

i forget that my purpose is to take her out of this torrent

tiny bubbles tickle my neck as she whispers in my ear

“it’s just bathwater silly.”

i sigh and then i giggle the need to breathe knocks against the walls of my chest it is time to leave i cling tightly to the sides of the bath and finally, i raise myself to the surface goodbye weightless child tethered to the drain

thank you for wringing me dry.

Outer Child

Katriel Tan

Author’s Statement:

Often, we find ourselves hyper focused on this idea of ‘healing’ our inner child – we think we’ll find solace in putting a younger version of ourselves back together. This idea of our inner child being ‘broken and helpless’ is a constant meta-narrative that permeates our mindsets and I sought to write something that reflects the significant extent to which we discredit the inherent power of our inner child to already possess traits we don’t realise can provide comfort to our current selves; a pure innocence, a lighter perspective of the world and a stable understanding of self that is whole and dependable.

Our inner child doesn’t always need salvation or pity, and rather, we should remind ourselves that they are a powerful force of warmth intertwining our temporality, who we should actively seek, not to fix, but to fully embrace our current selves in the solace that they can provide.

Art by Jasmin Small

37.

-K

The Queer Experience: The Nexus Between Sex and Power Rafferty Edis

I think about sex a lot.

And a question I often come back to is: are sex and power inherently linked? Specifically, how do these dynamics play out in queer sexual experiences? Being bisexual, I can’t speak to every queer experience, considering the diversity of our community. However, I do think there are particular challenges that we collectively face due to our sexuality and/or gender identity within a heteronormative patriarchy. One area where this is salient is sex.

Growing up queer, there is limited exposure to positive queer models of having sex. Instead, we are exposed to a very narrow and rigid depiction of sex; one that is heteronormative and propagates this idea of domination and subjugation. The work of radical feminist, Andrea Dworkin, provided insights into the subordinative nature of sex. Dworkin’s theories suggest women are not having sex with men, but are instead being f****d by men. This narrative is fed to us through porn, movies and music, right down to advertisements and the language we use surrounding sex. This in itself is problematic.

Media in this space is produced for a predominately straight male demographic. But if you’re queer, you are left without a model of healthy, safe sex that is aimed at your sexual identity. Progress is being made and representation is getting better. More inclusive, sex-positive portrayals of sex in the media, such as Netflix’s Sex Education, are breaking the stigma and challenging the conventional power politics of sex. But often, the patriarchal-heteronormative model of sex is copy and pasted into queer media and queer porn. One such example is the critically acclaimed Call Me By Your Name, which centres a sexual power imbalance in the form of an age gap.

Most queer porn still propagates a power imbalance where one party is dominating their sexual partner/s. Actors are often stripped of their humanity and reduced to their bodies, vehicles for pleasure. This generates expectations in real sexual experiences; where one partner may feel entitled to sex, or a specific type of sex, one with a power imbalance and domination. I’m not referring to consensual role-play of sub/dom positions, provided boundaries are clear and respected. Instead, I’m referring to the more pernicious exertion of dominance or force over a sexual partner(s). This can be through physical force or emotional manipulation.

When domination occurs outside the clearly defined parameters of roleplay; there is an easy segue into disrespect, exploitation and abuse. This is because one party’s needs and desires are being privileged over another’s, with little regard for how the latter may be affected.

Visionary feminist bell hooks discusses how domination is conducive to and creates an acceptance of violence. She discusses how sex can be used as a cathartic release for male rage rooted in unmet promises of privilege and power made by the patriarchy. While she is talking about heterosexual dynamics, queer sexual dynamics are not immune from patriarchal influence unless all parties involved are consciously working against it.

38.

Art by Jasmin Small

Content warning: sexual violence and sexual harrassment

Growing up with the internalised belief that sex always entailed domination put me in unsafe situations I came to accept sex as having these concomitant feelings of fear and discomfort. Things came to a head when I was 17; my boundaries were violated and I was left with a damaged sense of self, high anxiety and insurmountable shame. But I still didn’t see the problem with this model of domination and by extension, male aggression, until much later. Because I thought it was normal and just came with the territory. Through more positive sexual experiences, I came to realise that there was nothing biological or innate about this. It was cultural.

Rates of sexual abuse and intimate partner violence within the queer community are appalling. These statistics are even higher for transgender people and queer people of colour. Human Rights Campaign found 44% of lesbian women and 61% of bisexual women experience intimate partner violence (IPV) and sexual assault (SA). 26% of gay men and 37% of bisexual men experience IPV and SA and 47% of transgender people are assaulted during their lifetime, with even higher incidence among people of colour. Additionally, there are barriers to reporting; which is already a stigmatised process in itself but exacerbated with the additional elements of gender (such as emasculation) and/or race (such as racial profiling). Violation can be a way of ascertaining a sense of power at the expense of someone else. Sexual assault and intimate partner violence can derail the lives of the victims and ruin their relationship with intimacy, touch, love and sex.

Another facet of this is homophobia or transphobia held by one or more sexual partners, even if it is internalised. It can be a source of shame for those who aren’t comfortable with their sexuality and seek to reassert control by exploiting the power imbalance during sex. Additionally, we are never provided with a roadmap for how to navigate these situations where a sexual partner is homophobic, transphobic or not out.

Men in the patriarchy are socialised to be homophobic, especially in adolescence. I grew up in a rural community where homophobia was rampant and I saw firsthand how boys used homophobia to divert suspicion from themselves and assert their social power by being a ‘man’s man’. It is tied up in a bigger issue of patriarchal masculinity and rejecting what is thought to be unmasculine.

It has been difficult for me to reflect and see how the homophobic behaviours of others have created internalised homophobia in me. Being surrounded by homophobia in my formative years leaves a legacy that I have to consciously deconstruct. I want to ensure I don’t carry these beliefs into future sexual experiences, where I believe that I am deserving of poor sexual treatment due to being queer.

So within my own sexual experiences, I have seen my conception of sex shaped by a) the media and b) socialisation through my peers. This fostered a patriarchal and homophobic approach to queer sex. But there are more loving ways of having sex, where it is mutual, trusting, and a power imbalance isn’t present. Irrespective of whether you’re having sex for pleasure or intimacy, we need to challenge our ideas of sex and do it on our own terms, as both we and our sexual partners want. Not as the patriarchy tells us we should.

If you or anyone you know is affected by the content of this piece, please contact one of the support services below:

1800 RESPECT

1800 737 732

24/7 – National sexual assault, domestic and family violence counselling service.

Beyond Blue

1300 22 4636

24/7 - Depression, anxiety and suicide prevention

39.

Art by Jasmin Small

Take A Chance

Cristina Munoz

There’s something ridiculously embarrassing about taking up a new hobby as an adult. Recognising that there is something you want to try is the easy part. A quiet thought in your mind saying it would be cool if you could do that.

Putting it into action is harder.

There’s an endless supply of excuses.

I’ll never be as good as someone who started when they were young…

I’ll be so bad at it, everyone will be better than me…

I don’t have enough time, I’m too busy…

But what would happen if you did try?

Well, I can only speak for myself. Let me tell you what happened this year.

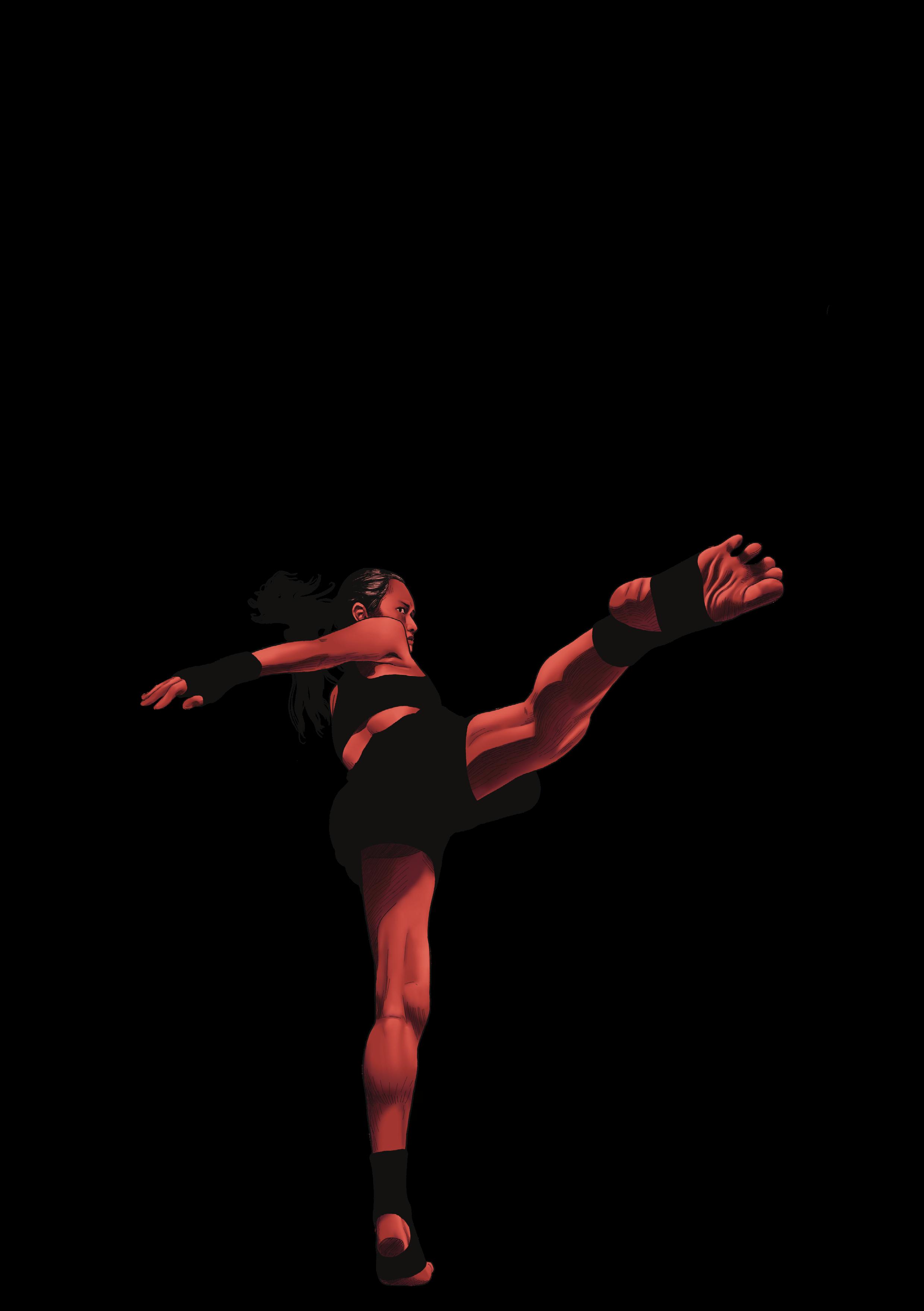

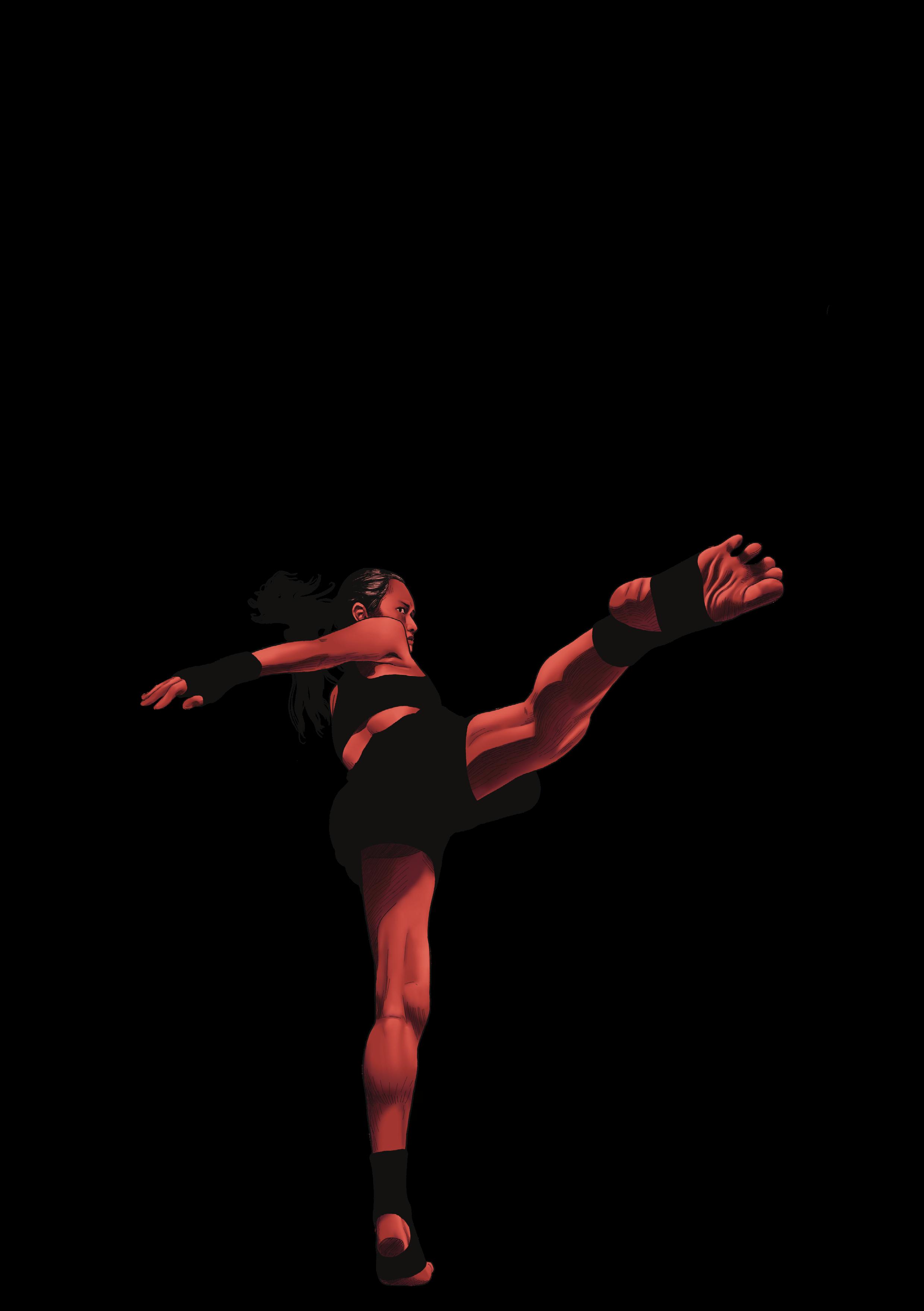

I always thought in the back of my mind that it would be cool to learn a martial art. For years I never did anything about it, because of the ‘reasons’ above. But this year, I figured, why not?

I may never be as good as someone who started when they were a child. But that doesn’t matter when you’re not trying to be the best. I mean, I don’t want to make a career out of this, I don’t need to be the best, I don’t need to be better at it than other people. I just want to try it for fun. To see what it’s actually like, and to be able to do something that I’ve never been able to do before. And if I start today, I’ll already be a little bit better tomorrow. And for me, that’s reason enough to try.