STILL I RISE

If not prison... what?

If not prison... what?

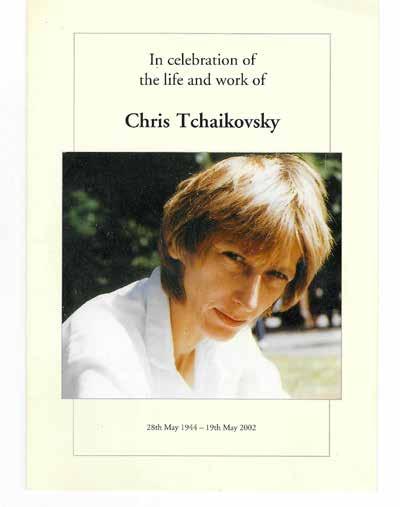

This special edition celebrates 40 years of our journey at Women in Prison, founded on the lived experience of Chris Tchaikovsky who started the charity. Chris believed that true and lasting change could only be achieved by including the voices of women with lived experience of prison in seeking justice and reform. She dedicated her life to lifting up these voices, knowing they were essential to building a better world.

We invite you to shareyour own vision of justice and change.If you could help others understand what real justice looks like, what would you want them to know? What changes do you believe are needed to create a kinder, fairer society? This is your chance to share what justice means to you, ideas that could inspire a better future for others.

Your entry can be in the form of a letter, poem, story, or artwork that captures your vision of justice and change. Like Chris, we believe that your voice has power and that your views are vital to creating lasting change.

We’ll select some entries to feature in the magazine, with a prize for the winning entry. We hope you’ll take part and share your voice with us.

Rules for entering the competition:

• Feel free to give your own interpretation of what mental wellbeing means.

• If it’s a story, essay, interview, or article (fiction or non-fiction) please write 500 words or less. When handwritten, this is between 1½ and 2 pages of A4.

• An entry can also be a poem, drawing, painting or a collage.

• Please include a completed consent form (see page 73) with your entry and send it to Freepost – WOMEN IN PRISON (in capitals).

Without the consent form we are unable to include your submission in the magazine.

One entry will be selected as a "Star Entry" with the writer receiving £20 (only entries that include the consent form on page 65 can be considered for "Star Entry").

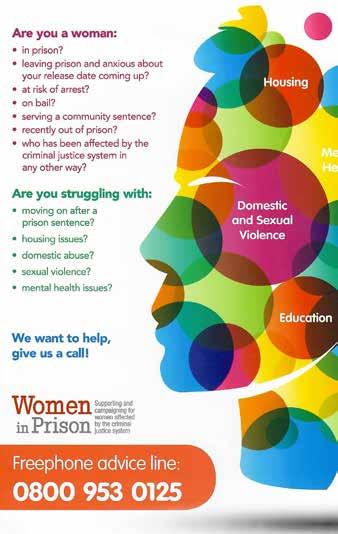

Women in Prison (WIP) is a national charity founded by a former prisoner, Chris Tchaikovsky, in 1983. Today, we provide support and advice in prisons and in the community through hubs and women’s centres (the Beth Centre in London, WomenMATTA in Manchester and in partnership with the Women’s Support Centre in Woking, Surrey).

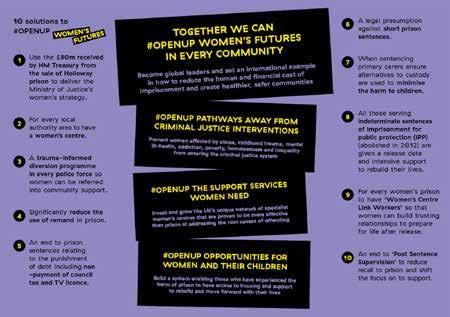

WIP campaigns to reduce the number of women in prison and for significant investment in communitybased support services for women so they can address issues such as trauma, mental ill-health, harmful substance use, domestic violence, debt and homelessness. These factors are often the reason why women come into contact with the criminal justice system in the first place.

WIP's services are by and for women. The support available varies from prison to prison and depends on where a woman lives in the community. If WIP is unable to help because of a constraint on its resources, it endeavours to direct women to other charities and organisations that can. WIP believes that a properly funded network of women's centres that provide holistic support is the most effective and just way to reduce the numbers of women coming before the courts and re-offending.

WIP’s services include...

• Visits in some women’s prisons

• Targeted ‘through the gate’ support for women about to be released from prison

• Support for women in the community via hubs for services and women’s centres in London, Surrey and Manchester

• Still I Rise A magazine written by and for women affected by the criminal justice system with magazine editorial groups in some women’s prisons

Please contact Women in Prison at the FREEPOST address below. Please include a completed consent form with your query; turn to page 65 for more details.

Email us on: info@wipuk.org

Mail us on: FREEPOST Women in Prison

If you enjoyed reading the magazine and want to donate towards the production of our next edition, please scan below:

Please know that whatever you are going through, a Samaritan will face it with you, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Call the Samaritans for free on 116 123.

ur service is confidential. ny information given by a service user to Women in Prison will not be shared with anyone else without the woman’s permission, unless required by law.

I’m so pleased we are

celebrating the 40th anniversary of Women in Prison with this justice themed edition. We hope you enjoy looking back at our timeline and reading about Chris Tchaikovsky our founder who continues to inspire our work.

It seemed like a great time for the HMP Styal editorial group, collaborating with the Manchester Women’s Justice Collective, to take over this edition and look at Chris’ legacy. To see what has and hasn’t changed for women in the criminal justice system over the past four decades.

Our theme of justice also led the editorial group to explore the impact of prison on loved ones, with Amy and Maureen taking us through their stories on pages 18 and 20.Along with the issue of health injustice and how, despite a national call for change, it continues to fail women who are imprisoned. Lee shares her health journey on page 60.

The editorial group also took time to

Project Manager: Kate Fraser

Art direction & production: Henry Obasi & Russell Moorcroft @PPaint

Production Editor: Jo Halford

The magazine you are reading is free for all women affected by the criminal justice system in the UK. We send copies to all women’s prisons and you should be able to find the maga ine easily. If you can’t, write to tell us. If you are a woman affected by the criminal justice system and would like to

imagine a different future and you can read about their vision in the article, ‘If not prison, what?’ In this, they challenge the way the system has always worked and reimagine a world with a radically different approach to justice – one that is centred on community and support over punitive punishment.

As we mark this milestone, we renew our commitment to fighting for a ustice system that serves rather than harms the women within it. Thank you to our readers, supporters and contributors – especially the HMP Styal editorial group and the Manchester Women’s Justice Collective for being part of this journey. Together we continue to rise.

With solidarity and hope.

Kate Head of Prisons and Co-Production

be added to our mailing list for free, please contact us at Freepost WOMEN IN PRISON or info@wipuk.org

The publishers, authors and printers cannot accept liability for errors or omissions. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of Women in Prison. Applications should be made directly to Women in Prison. Registered charity number 1118727

Women in Prison’s 40th Anniversary Project is made possible with The National Lottery Heritage Fund. Thanks to National Lottery players, we have been able to realise our ambition to chronicle re ect on and celebrate, the history of WIP’s achievements, representing a unique perspective on women’s experiences of the criminal justice system over the last 40 years.

Women’s Centres run by WIP

Women’s Centres where WIP staff are based

WomenMATTA – Manchester

The Beth Centre – Lambeth, London

Women’s Support Centre – Woking, Surrey

Women’s Prisons

HMP Low Newton – near Durham

HMP Askham Grange – near York

HMP New Hall – near Wakefield

HMP Foston Hall – near Derby

HMP Styal – near Manchester

HMP Drake Hall – Eccleshall, Staffordshire

HMP Peterborough

HMP Eastwood Park – near Bristol

HMP Downview - Sutton, Surrey

HMP Send – Ripley, Surrey

HMP Bronzefield – Ashford, Surrey

HMP East Sutton Park – Maidstone, Kent

HMP Cornton Vale – Scotland

“Never give up hope. If we do, they win!”

Chris Tchaikovsky, Women in Prison founder

Words: The editorial group: Amy C, Maureen, Kelly, Leanna, Rachel, Natasha, Jennifer, Amy P

We are the editorial group for this edition of Still I Rise magazine.

We are a group of women serving time in HMP Styal, each of us is affected by (in) justice in different ways. Between us we are in prison on different sentences, for recall, joint enterprise and the new extended determinate sentences. We got involved in this editorial group to have a voice, to get stuff off our chest and be part of speaking our truths to other women in prison and people on the outside.

This edition has ‘Justice’ as its theme for two reasons. Firstly, we are doing a takeover of the Manchester Women’s Justice Collective (more about that in the next article). We’re also using the 40th anniversary of Women in Prison to challenge ourselves and the organisation to think about what it would mean to ‘serve’ women justice.

Prison can take away our ability to think. It takes away the feeling that we have skills and something to say. Prison can rob us of any confidence we might have had. question we started to ask ourselves is, when do we stop feeling the power of prison in our head?

In the editorial group we created a space that tried to challenge some of this. There were some interesting convos, we didn’t always agree! But it’s good to hear what other people think, to be challenged, or even just to say what you think and be heard.

s women in prison our voices matter. We have an understanding and power of thought that doesn’t exist elsewhere. We can make a positive contribution. We can challenge and inform policies about us. We can drive the ideas and work of organisations like Women in Prison.

‘The justice system brought me to justice, it has not served me justice’

Freya – Stories of Injustice*

Oregon State University

‘We fight the same battles over and over again. They are never won for eternity, but in the process of struggling together, in community, we learn how to glimpse new possibilities that otherwise would never have become apparent to us, and in the process we expand and enlarge our very notion of freedom’

Angela Davis, 2009 Political activist (cited in Davis, 2012: 198)

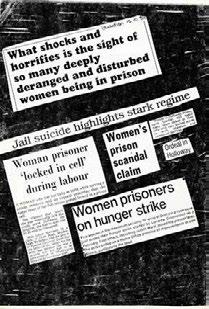

As a group we looked at some of the Women in Prison archive materials to see what Chris Tchaikovsky and the founders were so angry about and challenging in the 1980’s. It was shocking… so much is the same, really not much has changed for women in prison. We need to keep campaigning, calling the problems out and demanding justice for women. In

building communities, like our editorial group, we can see new possibilities for how we might do this.

It’s been a blast. We hope you enjoy this edition, and who knows the next edition could have your voice in it.

*Stories of Injustice, Manchester Metropolitan University, November 2020 Stories of Injustice.pdf

Words: Becky and Zara

For this edition the HMP Styal editorial group did a takeover over of the Manchester Women’s Justice Collective so they could work together on the magazine. The collective look at justice in the community, providing spaces for the voices of women. This takeover has allowed the HMP Styal editorial group to take up this space in a similar way but while in prison. Becky and Zara from the Manchester Women’s Justice Collective talk through their experience of this joint work and tell us more about the collective.

omen from the Manchester Women’s Justice Collective and the HMP Styal editorial group came together to create this special issue of the magazine. We met every Friday in HMP Styal over a couple of months. We talked, we ate, we made brews. We talked some more. There was a lot of laughter, and a few tears. It was all about connection.

We felt very blessed to have been part of the editorial group. The Styal takeover of the collective has enabled us to connect the ideas that have come from community spaces to a group of amazing women inside HMP Styal.

The Manchester Justice Collective In 2022, a London based project StopWatch asked us to help hold a day

event in Manchester where women and girls could share their experiences of the police. A small group of young women, all with experiences of being policed –arrested, searched, held in custody – came together and spoke. Rather than be talked about by others, women spoke for themselves. They called out what had been happening to girls and women in the city and started to say what needed to change. ince then we have had five more events. These spaces have become known as the Manchester Women’s Justice Collective.

We believe in justice, and we think this can only be achieved if we make sense of it and fight for it collectively. ur ustice is not defined y others not y systems or by people in power. Justice is something we must define that wor s for us and represents our life experiences. This collective exists to be on the ground with women, whether in the community, prison, or anywhere else. We are all about

making space for the messiness and reality of women’s lives. That might include frustration, anger, hurt, but also includes care, joy, and jokes.

We are at the start of our journey and who knows where we will end up, but that’s okay. This issue of the magazine is a testament to what can be created when space is made for the voices of women in prison.

40 years ago, Chris Tchaikovsky, Pat Carlen and others founded Women in Prison out of a desire to demand change. Right now, we see the Women’s Justice Collective as pushing to do the same. We are asking different questions, in new ways, to demand change – what is justice for women?

In our spaces sometimes someone sings or writes a poem or we watch a film or a play. There’s a lot of talking. Someone will tell a story, something that happened to them or someone they know. Sharing their take on it, and why they see it that way.

Our justice is not defined by others, not by systems or by people in power. Justice is something we must define.’

Words: Maureen and Jodie

Children, families and loved ones are impacted on when someone is in prison. Two women share their stories about this and how it a ects their relationships.

Words: Maureen

When my kids come to visit, I struggle. Its hardest for my boy, it breaks his heart coming.

Knowing they’re searched, some kids are affected more by this.

Who picks up the pieces for kids on the outside? Yes, there’s the family, we’re lucky my dad cares for them all, but it’s not enough. They can be anxious for weeks after and emotionally affected. I know from my dad it affects their lives.

I love seeing them, but I really hate visits. You lie to each other, you do. Try smiling at each other and seem okay. It’s a big lie and its heartbreaking. Oh at the end it’s the worst finish the visit now”, again those smiles and that walk out for them. It destroys me, and it destroys them.

We were lucky the family days were so different; time felt more natural and we relaxed and ate together. We could share gifts. Such small things but they really matter.

But they’ve stopped them, the family days. The kids were happy to come to them and so we didn’t pressure them about the other visits. We were happy to have them. First, they stopped the meals and gifts and now they’ve stopped them all together. It’s about drugs, I get it, but this isn’t the answer.

The family days are a lifeline, the thing that stops women going under in here.

When I was 14 and my dad was sent to prison, it wasn’t just his absence I felt—it was the shame and stigma that settled around me. I came home that day to a house full of grief and chaos, with my sister taking on the role of my carer and friends’ parents not wanting their kids to be around me.

y life ecame defined y silence and the views people held about my family, which meant I never got a chance to truly share what I was going through.

i e so many kids experiencing this now, I felt invisi le in a system that had no understanding of the pains of imprisonment—both from the inside and the outside. This experience has shaped everything I’ve done since. It’s driven me as a campaigner to push for change so that kids and their parents inside have the support understanding and agency that I desperately needed.

When the pandemic hit in 2020, I was in my early twenties. eople ept tal ing about the pandemic as this ‘great e ualiser’ where everyone up and down the country was dealing with isolation and staying indoors ut that couldn’t

have been more misleading.

When I heard all prisons had suspended visits and shut down contact with the outside world, I felt a pang of grief thinking back to when I was 14—coming home from school to find out my dad had been sent to prison and I didn’t know when I’d see him again.

‘I felt invisible in a system that had no understanding of the pains of imprisonment’

In response, me and my mate set up Our Empty Chair, which grew into a mutual aid group supporting families separated by prisons and immigration detention during the pandemic. We organised with families, collecting images of the empty chairs left behind by loved ones inside prison, to show how pandemic restrictions had worsened the impact of this painful separation. We worked with barristers to raise concerns with the government about how children’s human rights were not being upheld due to suspended prison visits.

Knowing what it’s like to have a parent inside, combined with being a campaigner, brings into focus the big and small things that can ease the pain of imprisonment for people inside and their families. Release on Temporary License (ROTL) was a lifeline for my dad and our family as it stopped us having to cram all life’s important conversations into short, infrequent and painful visits. It’s the same with family days—even if I felt teenage embarrassment watching my dad try a tug-of-war in the prison yard, having a full afternoon of quality time outside a cramped visiting hall made such a difference.

In my campaigning work, I often think

In my campaigning work, I often think about policies that could reduce the need for prisons’

about policies that could reduce the need for prisons in the first place. o me that means addressing root causes like poverty and mental ill-health as starting points, not as afterthoughts once people are already in crisis. We need bold, systemic change that keeps families together, addresses the struggles that lead to imprisonment, and ensures that kids, like I once was, don’t have to carry the weight of shame, secrecy and separation.

Campaigns and organisations raising awareness of the impact of prison on children and providing support.

The Collective Punishment Campaign. Set up by brilliant young activist Jemmar following her own experience of parental imprisonment, it works towards securing the policy changes needed to meaningfully support kids with a parent inside.

Email: info@collectivepunishment.uk

Time-Matters UK. Working in local communities, they provide support directly to kids with parents in prison, as well as to whole families.

Email: info@timemattersuk.com

Out There. Based in Manchester, they support families with a person in prison. They offer support and information; referral to access other support, like welfare advice; and opportunities to meet other families going through the same.

Call: 0161 232 8986

Children Heard and Seen. They work in local communities, providing support directly to children who need it.

Email: info@childrenheardandseen. co.uk

Words: Maureen and Kev Illustration: Up Studio

Maureen interviews her dad, Kev, about the impact on his life of her and her sister being in prison.

Maureen: What was the impact for you Kev and Sue (our mam) as our parents when we got convicted?

e aureen’s a It was the worst experience of our lives. It hit me when you were found guilty of murder, knowing you never did it. But when you got the sentence, it was like watching somebody else on tv. I have always been a level headed person but that day nothing sunk in. All I could think about was how was I going to tell your mum. I can even remember driving home, hoping someone else had told her so I didn’t have to break her heart.

After telling her she seemed to age before my eyes. The spark went out of her. It changed us both. I stopped trusting people. I couldn’t get my head around how the police and CPS [Crown Prosecution Service] lied just to win the case. It broke our hearts. I felt inadequate as your dad, I had no control over what

was happening and I guess I just didn’t know what to do to help you.

Maureen: How has it changed you Kev? I know you joke saying you got four kids for your 60th birthday.

e aureen’s a Well, I feel it has kept me younger. I mean it didn’t make a big difference cos the kids were always in our house. I’m 72 now and the kids they all keep me on my toes, I wouldn’t have it any other way. I always thought I’d end up a grumpy old man, like Victor Meldrew, but I am good for my age, young like, and the kids have done that. So it’s a win-win for me.

Maureen: How do you manage with the kids, especially at Christmas and stuff?

e aureen’s a I can’t do Christmas anymore, because your mum and you aren’t there. I can’t pretend it’s a happy time. Your mum did Christmas, she was

Mrs Christmas, without her the spark’s gone. We go away or do something different. I let the kids live their lives but they know I’m always there for them. Even when I ask them if they want to come up and see you I let them have the choice. I’m there for them when things go wrong or they need comfort, they know that.

Maureen: What are you most proud of Kev, and how have you found the stren t to stan up an keep tin for us?

e aureen’s a I am most proud of you and Kelly, my brave daughters. You have adapted to your lives there. I always tell you they have your body but don’t let them have your minds, and you have stuck to that. That makes me the proudest dad ever. I would never give up, it’s not in my nature and neither have you. Even when I’m dead I’ll be back to haunt them all. I’m never ashamed. I go out and buy your clothes, even your underwear and that. I tell them in the shops, this is for my girls they’re in prison. Your mum always said I was stronger than her, and she said she didn’t think she’d be here when you finally come home. I told her you’re not leaving me on me own with these four kids.

Maureen: Our dad always turns everything into a joke, his heart is broken but he can make us laugh still. We just want you to know dad, our big Kev, we would be lost without you. You’re the most amazing dad and we are so thankful for you and me mum. All your love and how you took over and looked after our kids. You walk tall big Kev, we love you so much, thank you for everything.

‘I can’t do Christmas anymore, because your mum and you aren’t there. I can’t pretend it’s a happy time.’

Amy shares how over the years she has lost contact with her family as an impact of being in prision, in particular her grandma who she was closest to.

“Hiya Grandma, are you okay?”

That is the depth of conversation I have on the phone call with me and my grandma. Over the years it’s got gradually less and less. I tried so very hard to keep our relationship going.

I knew I couldn’t pull away from the fact I felt safer in prison, but I was always open and honest with my grandma. I used to get out of prison and tell her I was going ac to tyal. he first thing I did was go to her house, she hated hugs and was very uptight about things, but she was the one person I could rely on. Let’s just say people show love in different ways I moved to my grandmas in 1996, my mum was a heroin addict, so me and my brother was better off with her and my grandad. In 2011 when I came to Styal for

criminal damage I had all the family support I needed. My grandma, my dad, brother, all missed me when I came to prison. But as the years passed and my custodial sentences were getting bigger and bigger, the more times I came to prison the more I got a sense of belonging here at Styal. As sad as it sounds, I’m okay in prison. I felt like I had lost my family but gained a new one in Styal.

In 2023, I got the biggest sentence I’ve ever done. I’ve been here 10 months now and I don’t get any visits from my family. I’ve completely lost them; I don’t know them anymore. That’s the impact I’ve had on my “FAMILY”.

I asked my grandma what’s it done to her, my coming to prison? “I just get on with it now I know you’re safe in there” she

“In 2023, I got the biggest sentence I’ve ever done... and I don’t get any visits from my family. I’ve completely lost them; I don’t know them anymore.”

said. I was gob smacked at that reply, she never said we all miss you and can’t wait to see you. I’ve een so selfish over the years, committing crime to feed my drug habit, not thinking of anybody else. So it’s come as no surprise that I’ve become a stranger to the one person I love the most – my grandma.

If it’s your first time in prison use this

time to re ect on what’s happened and never come back to prison again, accept all the help you can. I wish I would have taken my own advice and listened to all the professionals who try to help people like me and you. Don’t lose out on life coming to prison if you have a family or even loved ones outside of prison, cherish them.

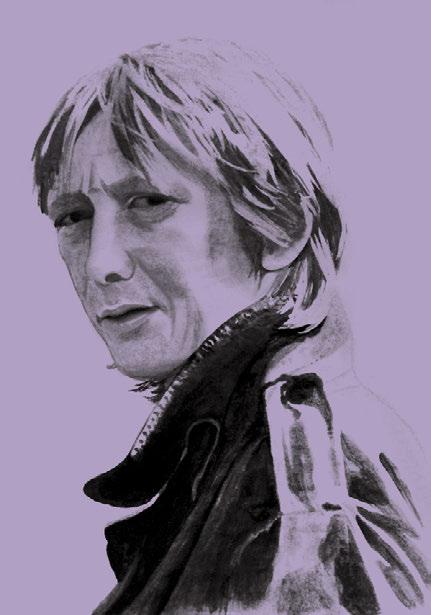

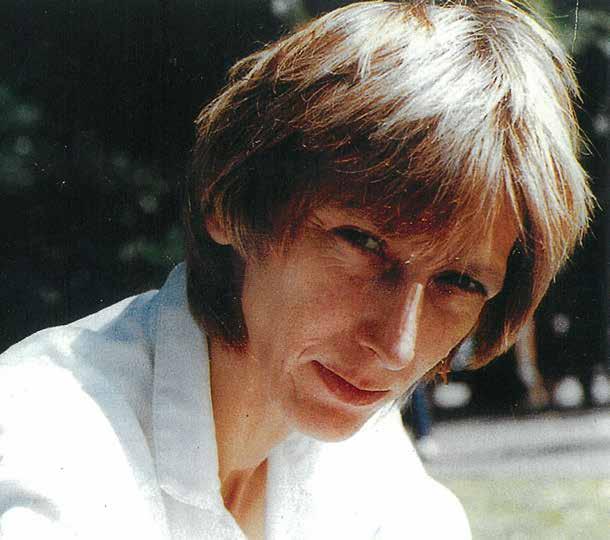

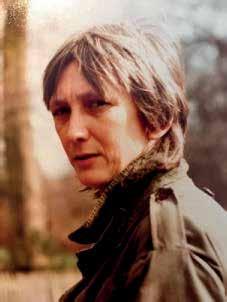

hris Tchaikovsky was a strong leader whose life and work changed the support for women in the criminal justice system. Shaped by her own life experiences, she had a deep understanding of the challenges women in prison face. Her journey from a rebellious young woman to a leading voice for change impacted on the lives of many women affected by the harms of the criminal justice system.

Chris’ early life was marked by a strong sense of independence. She often clashed with authority figures and was expelled from several schools due to her rebellious spirit. Looking for a life free from what was traditionally expected of her, she moved to London during the 1960s and formed a gang known as the ‘Happy Firm’.

Chris stood out with her impressive height, six feet tall, and magnetic personality. She was known for her sharp wit and ability to connect with people from any background. Her intelligence and

passion for learning drew others to her, and she connected with people on the edges of society. This connection to people who experienced life differently would later inform her commitment to helping women within the justice system.

In 1974, Chris was sentenced to prison, where she experienced the harsh life faced by women in the criminal justice system. She saw the cruel treatment and routines that were part of prison life, including poor healthcare and a general lack of respect for the dignity of women. This experience set off Chris’ determination to fight for change and to make sure the voices of women in prison were heard.

In 1983, Chris started Women in Prison to campaign and provide support for women affected by the criminal justice system the first campaign group to do so. She became a force for change, committed to bringing the stories of women directly to politicians. Chris

organised protests and pickets outside prisons and the ome ffice demanding the harsh life faced by women in the system be acknowledged. She would even follow Members of Parliament (MPs) to their cars refusing to let them ignore urgent issues.

Chris was relentless in her pursuit of ustice elieving that if she could share women’s stories she could change the hearts and minds of those in power. She personally brought the experiences of women in prison to s advocating for reforms and better treatment. Her unwavering dedication and passion made

her a respected and formida le figure.

Despite the challenges of running an underfunded organisation hris remained committed to her mission. Her charisma and determination inspired many and her a ility to connect with others made her a eloved figure in the movement for prison reform.

Chris Tchaikovsky passed away in ut her legacy remains today. Women in Prison carries on her mission. Chris’ life serves as a powerful reminder that true change begins with compassion and a commitment to uplifting the voices of those often overlooked.

On the 40th anniversary of Women in Prison, people who knew Chris share their memories of her and talk about the work of Women in Prison – Chris’ legacy.

athy first wor ed at Women in rison WI from to . he started as a volunteer and went on to do several different roles including a casewor er researcher and pro ect manager for the Education and raining onnection. he returned in as cting irector. It was under athy’s directorship that Women in rison started this maga ine.

What Cathy said about Chris and Women in Prison:

hris was a huge character uite imposing as a person and uite a presence. charismatic woman rilliant and generous and uncompromising. he too people in and loo ed after them. hris used to sit and tal to me for ages a out her experiences. I loo ac at that

and some of those conversations were a solutely formative in my life. I had my consciousness raised at Women in rison. here is still a lot of stigma a lot of udgment and a lac of understanding a out the context of why women are criminalised. When I was irector we started the maga ine and I was really proud of that. It’s great to see the maga ine is still going.

uthenticity and Integrity were really important to hris and you can see that in WI now.

LIZ HOGARTH

i wor ed in olloway during the s efore ecoming the inistry of ustice policy lead on women in the riminal ustice ystem in . i wor ed closely with hris chai -

‘Chris was a huge character… imposing as a person and quite a presence. Brilliant, generous, and uncompromising’ athy tancer

‘She was funny, passionate, fearsome to those in authority. She was so bright and articulate they didn’t stand a chance’ Liz Hogarth

ovsky during her time in HMP Holloway and with Cathy Stancer during her work on the Corston Report – she continues to work closely with Women in Prison today. Liz retired in 2011, but still works with The Corston Independent Funders’ Coalition and women’s sector to bring about lasting change for women caught up in the CJS.

What Liz said about Chris and Women in Prison:

Chris was the whole gamut [all things], I have never met anyone more passionate. After her prison sentence she came out knowing as a more middle class woman she could have had an easier life, but instead it was going to be all about fighting for those women who hadn’t had the right sort of support. Her passion was infectious. She was funny, passionate, and much to my delight she was fearsome to those in authority. She was so bright and articulate they didn’t stand a chance. If I was concerned about a woman, the next day Chris would be in there.

Lived experience was at the heart of whatever Chris did, her whole thing was about giving a voice to women. It’s only in recent years that some women’s project are talking about lived experience being important, but for Chris it was there from the get go. So for me WIP has always been ahead of the game on that. WIP always speaks with authority because they use what they learn from women every step of the way.

I do see the same passion in staff, the same sense of hope, the same sense of

never giving up. That could be WIP saying to women we’re here for you but it’s also a out fighting the system to ma e things better. I know Chris would have loved to see today how much women with lived experience mean to WIP.

I think there is hope for greater change and WIP could and should be front and centre of that because of their deep knowledge for and with women. When WIP work for women they stand alongside them and do not tell them what to do.

Charmaine is Women in Prison’s Peer Mentor & Training Coordinator. Charmaine has worked with Women in Prison for nearly a decade, working with women both in custody and in the community.

What Charmaine said about working at Women In Prison:

I don’t know if I can pick a favourite thing, because it’s been all the little wins to support women, and that’s been amazing to have that happen. To have women say, “Charmaine, I am doing this now” and see that pride they feel in themselves and wanting to share that with me…that, to me, tells you you’ve made a positive impact on somebody.

Women in Prison is trusting in allowing you to grow a service, because they’re quite small. If you can think outside the box they’re here for it because at the end of the day they want to find many different ways to support women in their different journeys.

As we celebrate the 40th anniversary of Women in Prison (WIP), we want to show you how WIP came to exist and take you through the last four decades. We start with Chris Tchaikovsky, one of this country’s most effective campaigners for prison reform for women. From a middle class family, Chris was repeatedly expelled from school and said she found herself drawn to ‘outlaws’. Moving to London in the sixties she ran a criminal gang known as the Happy Firm – specialising in cashing cheques with forged ID. In 1974 she served a sentence in HMP Holloway where a woman burned to death in her cell – it was rumoured her alarm bell had been disconnected so staff could sleep.

When Chris left prison, she began a degree course and ran a women’s disco but in the early 80’s she heard a second woman had burned to death in HMP Holloway, and Women in Prison was born. With criminologist, Pat Carlen, Chris gathered a group of like-minded women, most with experience of prison, concerned about the conditions at olloway. t that time no one was fighting for reforms in women’s prisons and Chris understood that what women needed in prison was very different to what men needed. She set out to tell people about what was happening and to get changes made.

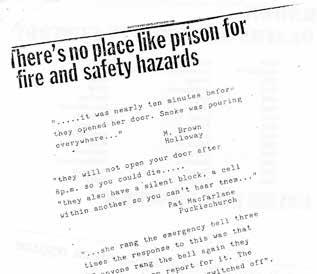

WIP’s campaigns had a clear focus, which was to raise public awareness about the harsh conditions in women’s prisons; of how women were often held in brutal and isolating conditions living under strict and harmful rules; and looking at the challenges women faced when they left prison such as finding somewhere to live.

WIP looked at other issues, HMP Holloway’s C1 Unit was operating as the prison psychiatric wing. ecause it was part of the prison it was staffed y prison officers who had no medical training and nurses who often had no psychiatric training. Women were locked up 23 hours a day in a bare cell – which just made sick women sicker. Women in Prison also shone a spotlight on the treatment of women at HMP Durham’s H Wing where women had to endure intense security measures such as strip searches, restricted visits and 24-hour surveillance. And WIP started to raise awareness of mothers and babies in prison and the alarming number of deaths of women. Women in Prison were picketing outside prisons, talking out on radio and television and pushing MPs and prison governors to make changes. Everything that WIP did, every campaign they wrote and every change they demanded was based on what women told them and the lived experience of their staff and volunteers.

In the 1990s, WIP received bigger amounts of funding to develop and deliver services that worked directly with women, providing one to one support while women were in prison and when they got out.

WIP services were a new and radical way of working with women, based on what women were telling WIP they needed. The Holloway Remand Scheme was set up in May 1994. It looked at the ways women could be kept out of prison, working with women on remand who intended to plead guilty. Bringing together the woman, probation and her legal team to look at the reasons why they had committed their offence in the first place.

A woman would write her own plan that considered the reasons they committed their offence and how to tac le the issues it could e getting into detox or finding somewhere to live. his plan would then be presented to the Judge at court. If the plan was accepted, WIP would continue to support the woman with her plan. WIP had other projects, including an Education Connection project that provided funding and education support for women in prison, which could be continued at colleges on release, and a postal service providing advice and information to women writing from prison. Nowadays, with so many different support schemes it’s hard to realise just how radical these services were for their time.

Even though WIP was growing bigger and now providing different types of support to women, Chris remained focused on her commitment to changing the criminal justice system for women. Just as she did in the 1980’s, Chris was always out there, raising the banner for women, speaking their truth. She did TV and radio and helped academics with research about women in prison. She attended conferences and events and lobbied MP’s and prison governors for real change. At the centre of all of this was the voices of the women themselves – bringing their stories into the public eye and to the attention of people who could change the laws and the systems.

WIP also started working with other charities who were pushing to change things for women in prison. Organisations like Inquest who look at deaths in custody; Clean Break who use theatre to transform the lives of women who have experienced the criminal justice system; and Hibiscus Initiatives who support black women and migrant women, amongst others, in prison.

By the 2000’s, WIP had been supporting women and campaigning for change for twenty years. Some changes had been made based on WIP campaigns, in particular the end of the Prison Medical Service and the start of healthcare in prisons being handed over to the NHS and private health care providers paid by the NHS. This might not sound like a big deal, but it was a huge achievement for a small charity with little funding, still struggling to support thousands of women in and out of prison to overcome the challenges that result from going to prison. For example, finding housing getting a o help with addiction getting the mental healthcare women needed and were entitled to. Reuniting women with their families and ensuring that women knew their rights in prison and on the outside. espite this the fight still had to go on as the num er of women being sent to prison was increasing every year. Chris used to quote a Joan Baez song. “Little victories and big defeats”.

In 2002, Women in Prison were devastated by hris’s death at the early age of . ut the fight didn’t end. WIP continued to grow and to develop more services for women. ro ects li e oving n oving ut’ which supported women while they were in prison, picked them up at the gate on their day of release and carried on supporting them for as long as they needed. There was also the London ro ect and Women which provided a safe space for women on pro ation at Women’s Centres and hubs across Manchester and London.

Most importantly, Women in Prison started THIS magazine. It used to be called Ready, Steady Go and was written for women in prison y people on the out. ver the years it changed to what it is today: Still I Rise, a magazine written by women in prison, for women in prison. Women serving sentences now design, write articles and develop ideas for every edition including this th nniversary edition. our voices and your stories are still eing shared. ou tell us what’s important to you and we make sure that people are listening.

From our radical roots with just Chris and a few determined women shouting from the rooftops, Women in rison WI has grown into a national organisation who have in uence around issues affecting women in the criminal justice system (CJS). WIP talks and people listen and that includes s and the . taff may have come and gone offices have moved and different services we offer have opened closed and grown ut as an organisation our fight has remained the same. We stay focused on what you tell us, sharing your stories and demanding the change required to end the oppressive system of hundreds of women being sent to prison every year, causing harm to them, their children, families and communities.

Women in prison has supported thousands of women over the last 40 years, created new services in prisons and in the community and has seen campaign victories. A big win came in 2016 when HMP Holloway – the prison that WIP had campaigned about right from the start –was finally closed. hrough its year history it was nown for a rutal and inhumane regime that saw the force feeding of suffragettes on hunger strike and the UK’s last execution of a woman in . he a andoned site where olloway once stood serves as a reminder that he nswer Is ot rison. Women in rison’s latest campaign he nswer Is ot rison calls on the UK Government to focus and invest in services that look at why women are getting caught up in crime and to stop them from going to prison. Our goal is to make sure that women who might be facing challenges such as poor mental health, addiction battles, homelessness, abuse, and other issues receive the support they need in their communities, when they need it. hris chai ovs y would have een delighted to see the recent drama Time which told the stories of three different women sent to prison. It highlighted the mental suffering of women, how they are viewed by society and the ripple effect of their imprisonment on the families they are ta en from. he acted as a consultant on I ’s Bad Girls back in the late 90’s and believed that the programmes reminded the public that most women in prison have experienced some form of trauma and abuse before they got there.

So, 40 years down and who knows how much more is to come? Keep reading.

Words: Women on Bruce House, HMP Styal

Illustration: PPaint/J Bucknall

Women on Bruce House, HMP Styal, share their experiences in a single person story of how long punishment goes on once you leave prison in the way both people and society treats you.

As a woman who has served time in prison I often find myself struggling with a uestion that affects hundreds of women who have served time at one of is a esty’s finest esta lishments when does the punishment really end

While I’ve served my sentence and finished my time on pro ation the conse uences of my past carry on shaping my life in ways I would never have imagined when my sentence was handed down in court.

The stigma attached to having a criminal record is li e a constant weight on my shoulders. ociety seems to view me through a lens of udgment often reducing my life to the worst decision I’ve made at a time when I was oth in crisis and crying out for help and support.

In this article I’m going to spea some truths they’ve all happened to me ut I also need any women reading this to now it hasn’t stopped me re uilding my life. eople need to hear a out what we are facing, how punishment can be neverending. Remember though, whatever we face eep getting up and fighting.

Finding a job can be hard

Every time I fill out an application and have to tic the previous convictions ox my mouth gets dry my heart races a little and I feel li e putting my pen down and ust not othering. If I’m luc y enough to get a o interview I can almost feel the unspo en eliefs a out me in the room. Employers

loo at my application with uncertainty ma ing it clear my record is more important to them than my ualifications and my eagerness to earn my own living pay my way and provide for my ids.

I’m never sure how much information an employer needs a out the worst time in my life a time that in my mind seems so long ago ut eeps getting dragged out in front of me. Is it ust eing nosey I now they’re going to oogle me when I leave and some old news story will pop up and give them what they’re loo ing for. ad ad ad I can almost hear the whispers as I wal out the door with my head held high ut the red lush of shame creeping up the ac of my nec .

Finding suitable housing can be a struggle

inding suita le housing has een another struggle. any landlords carry out ac ground chec s and the moment they see my record they loo at me li e I have a disease. he fear of eing turned away ma es searching for a home feel li e a cycle of re ection. Who wants to live next to me ot in my ac yard

in in insurance can e i cult inding insurance is also difficult. ar and home insurance providers see my history as a red ag leading to higher insurance costs for a car that’s only worth or a straight out no for any insurance at all. his constant reminder of my past mista es affects my a ility to re uild a normal life.

‘The stigma attached to having a criminal record is like a constant weight on my shoulders.’

Push through, get your life. At times, isolation has become my unwelcome companion. Friends and family often struggle to deal with my past, leading to difficult relationships and sometimes abandonment. It feels as if I’m trapped in some kind of weird time warp, no longer part of my old life, yet not fully accepted in the new one.

I often wonder how society can claim to prioritise rehabilitation while at the same time keep barriers that stop women like me from moving forward.

When does the punishment end?

I thought going to prison was the punishment, I didn’t know it would follow me, every day, year after year. I have re uilt my life. ot giving up finding good people and services like Women in Prison who were willing to give me chance – I’ve got a job, a home, a car. All of this in spite of things. It’s time to let women leave punishment at the gate.

Help and support is available if you experience any of these problems on leaving prison.

Unlock

Unlock support people with a criminal record to move on positively in their lives. They provide advice on employment, business and volunteering, housing, travel and insurance, an ing and finance.

Unlock helpline: 01634 247350 from Monday to Friday, 8.45am to 4.45pm.

Write to Unlock: The Helpline, Unlock, Maidstone Community Support Centre, 39-48 Marsham Street, Maidstone, Kent, ME14 1HH

Women’s entres

Women’s centres provide support across a range of issues including housing, domestic abuse, substance misuse and much more.

ou can find your nearest women’s centre on the website of the ational Women’s ustice oalition www.womensservicesmap.com

As this issue’s magazine editorial group, we share our thoughts and discussion on the magazine theme of justice.

Talking about getting rid of prisons is hard. It’s a pretty weird thing to try and make sense of, but when you’re in prison it gets harder. As prisons are part of the criminal justice system they are seen as a way of delivering justice through punishment.

When we tried to work out ‘what is justice?’ for women in prison, we got to the question ‘if not prison, what?

What is justice?

As women in prison, we know what injustice feels like. It’s being controlled and hurt by people or services. It’s feeling shame and judgement. It’s being silenced, unable to speak our truth.

There are loads of injustices in prison and for women when they leave prison. The healthcare in prisons is a joke. There’s no housing for women on the outside. Discussing these injustices, in a matter of hours we had listed so many direct experiences.

Being able to speak our truth is a big one. So often stories are told about us, in the courtroom, in the media. That’s why this magazine feels so important. It’s a space for us to speak our truths.

l Justice is where the truth matters.

l Justice is forgiveness, of ourselves and others.

l Justice is being able to be safe.

Sadly, for some of us we feel safer inside prison than out in the community.

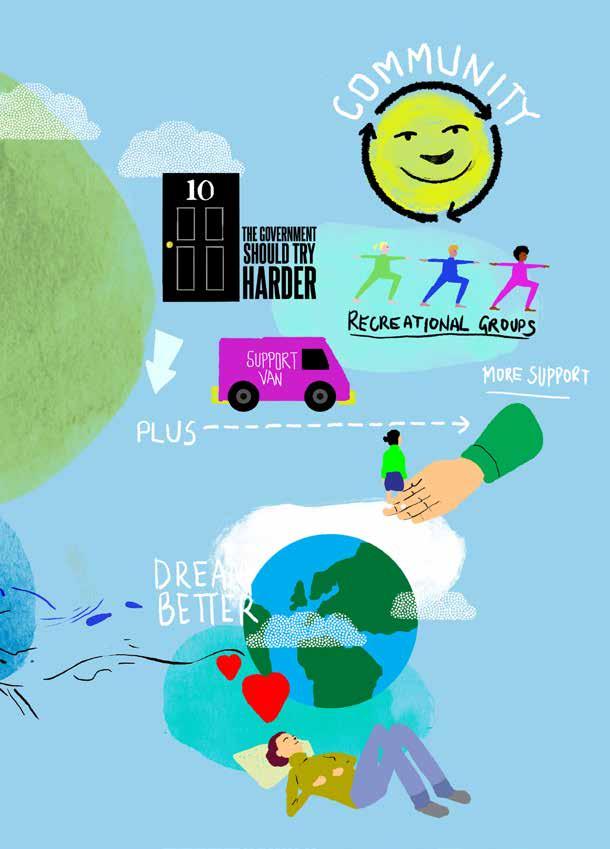

If not prisons, what?

In thinking about ‘what is justice’ we started to talk about what would need to be there to stop us, and other women like us, ending up in prison.

We talked about what the Government should be responsible for in our lives, what things everyone should have a right to? We talked about how everyone should have a home, be able to access healthcare, the opportunity to have a well-paid job … BUT we quickly said how much injustice there is in who gets any of these basics in life.

People are not treated equally, and our rights and needs are often not being met. We called these state (Government) failings. Any response to ‘if not prison, what?’ would need to be a community response to these state failings.

The community is people. It isn’t about a service’ that can fix everything. It’s a out people who care and who are brave enough to do things differently. When we think about what could have happened before prison, or the moments in our lives when someone did help us in ways that made a difference, they stepped outside the box, maybe even broke the rules.

A big thing for us is that any support for women should not mean you have to tick oxes and see if you fit’. lso it should not feel like charity, or like you’re begging.

It should be a community of people –us, me and you – working together and believing in more. We want the best for our

‘It should be a community of people – us, me and you – working together and believing in more’

community. We would work to create a new language about how women support each other. Yes, it’s needs and rights, but it’s more than that too.

There’s work to do here and it starts with us, women who have experienced prison and other services. The good, the bad and the ugly.

For some women their immediate needs are related to being able to use drugs safely, to get access to a dentist or a doctor, even just to have access to toilets, warm food or a coat.

Some of what the response must do, is to be there for women in their moment of need, when they are rattling or on the run. A supportive person there in your darkest hours. It’s not even about the service most times, it’s the person, how they treat us, with care and not judgement.

But we also want a response that dreams bigger for us. At times we can feel like we’re living in another world, how do we get back to your world?!

We want to love. We want to thrive, not just to exist and battle.

What a fantastic selection of creative pieces you sent to us for this latest edition, sharing your experiences and reflections. We’ve selected some of the best poems, letters and art you sent.

Words: Marnie

When you’re not feeling yourself, You start to not look after your health. In a place like prison you don’t know where to turn, Everyday there is something to learn.

Most people seem to lose all hope, And really don’t know how to cope. There will always be light in the end, But it’s down to you to get your life on the mend.

The hope you once had seems to vanish away, But all you have to do is to change your ways. I know this will be my last time, I feel it in my bones, As I know now I’m not alone.

The hope I once had has come back to light, nd I will not go down without a fight.

by Elaine

Words: Daisy Di

I landed in jail late on a Tuesday. I had never been to jail before or even been in trouble. I was scared not knowing what will happen. I’ve seen the movies, watched the prison shows. What I didn’t expect, and what got me through in the first days and weeks, is the Early Days team at Styal. They were always there in birght yellow to help. Nothing was too much trouble, nothing surprised them. The Early Days team mentors deserve a mention. No matter what state you come into jail, no matter how many times you return, they are there helping you over and over.

A simple smile, a hug, a kind word, a helping hand. The Early Days team are a credit to Styal. A go between from prisoner and prison officer. Thank you Early Days and also the mentors, you work so hard and really do care. You work so hard in your own time. You are appreciated in so many ways, without all of you Styal would be a hard place.

Words: Jennifer

To my unborn baby,

This is possibly the hardest thing that I’ve ever had to write, but I’d like to start by apologising for the circumstances, and promising you that I will only ever do my very best in loving and protecting you. You have given me light at the end of a pitch-black tunnel. Little did I know that I was pregnant with you when I came to prison and what a journey we have had together so far. You were around four weeks in my tummy when I came to prison, and I have prayed for your health every night since.

With the stresses of coming here, having to leave your brother and sister, battle in court for a crime that I didn’t mean to commit, I have worried greatly that you would make it through. But 20 weeks later, you’re happy and healthy now kicking away inside me. You’re a fighter and I cannot express how loved you are. I wonder what you will look like!

Being in prison is only temporary but it’s just the start of our new life together for now. There is a great deal of support for you both in here and at home. You have mummy (me), daddy, a brother, a sister, nanny and grandad. But not only family, you have a whole bunch of officers supporting you too. ou will only ever now the officers as their first names and you will never ever remem er your time here.

We’re a long way from home my beautiful baby but we will have forever and a day together at the end of it all. You truly are a blessing and I’m so proud to call you mine. We will be living in a big house together with other mummies and babies! You will have a cot right next to mummy’s ed you will go and play in the nursery with all the toys, you will go on days out, you will be going home to have sleepovers with daddy and so much more!

I’m a strong believer in what’s meant to be will be, and you my sweet child are meant to live a long, loved, happy and healthy life. I love you.

Always & forever,

mummy xxx

Words: Rachel

For women in and out of prison it’s the opposite, here’s the reasons. You lose your integrity and all your credibility, You lose your stability and your sanity. You lose your health, You lose your job and all your possessions.

You lose your pride, And you slowly lose your mind. You lose your freedom and your time. You lose your name.

You lose your friends, and you lose your family. You lose that time with your kids, looking at their faces, And seeing them grow. You lose hearing them laugh and the times they have cried, You lose experiencing their joys, all the memories.

You lose too much when you’re inside, but that’s prison life. It leaves you out of sight and out of mind, With no help, no support, no purpose, And this isn’t the worst of it…

Imagine our power though, we the women who survive. We lose it all, but still we rise.

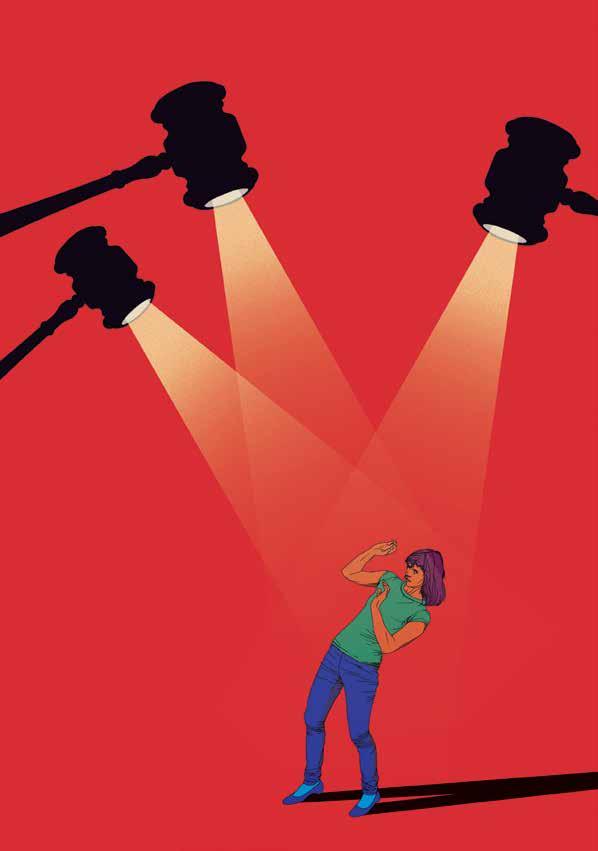

By Ben Jennings – in his own words

We were lucky to have the well-known illustrator Ben Jennings, a regular illustrator for the Guardian newspaper, illustrate the front cover for this special edition.

t the very first meeting of the editorial group when we were talking about the concept of justice, we looked at Ben’s Broken justice Guardian cover illustration. The women liked it so much they asked us to reach out to Ben to do the cover for this edition.

Ben shares his approach to our front cover brief

The brief for the cover was about questioning ‘justice’ and the numerous injustices - such as homelessness, lack of support for victims of domestic violence and systemic racial injustices - that can lead to someone becoming incarcerated in the first place. I thought having ady Justice herself imprisoned symbolised some of these contradictions, with her iconic scales smashed and scattered across the cell oor suggesting that something in the justice system is broken. isually I wanted the image to feel dar and evoke that loss of freedom, with the

only light being that which is beaming through the bars of a cell window, casting ominously over the inmate. eyond the issues relating specifically to women in prison, there is also a sense more broadly that – like many other aspects of the public sector – the entire prison system is broken. This has led to the controversial early releases due to overcrowding. So now seems a perfect time to question justice and what it means in practice.

“Justice for women means a criminal justice system that protects and understands women’s needs. It would stop the criminalising of abuse survivors with harsh sentences that punish not only the woman but destroy families and leave children with a legacy of trauma. Justice for women would break the cycle of violence, abuse and discrimination.”

Maxine Peake, actor

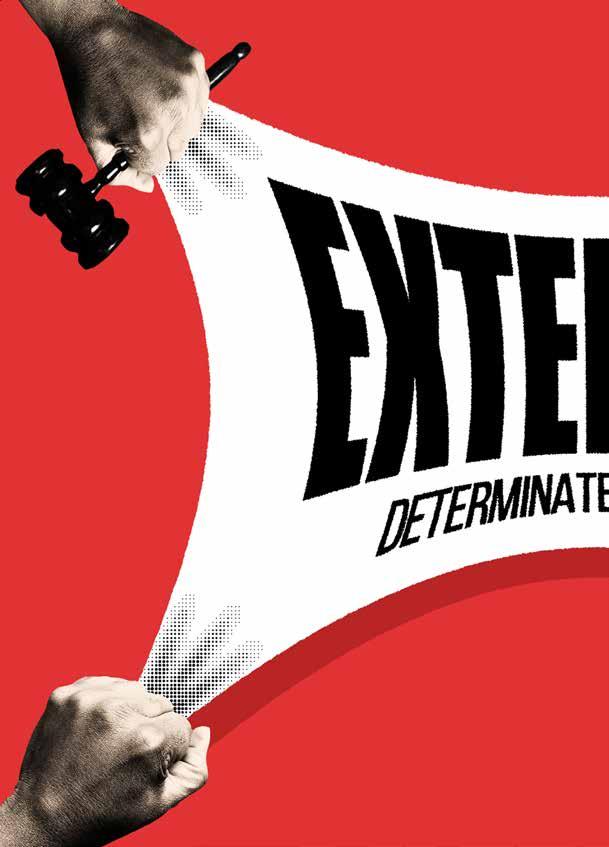

This article was written to respond to some questions the editorial group asked,

two of whom are on an EDS sentences and felt not enough is known about this new form of punishment.

you need to know

Women Prisoners’ Caseworker at Prisoners’ Advice Service (PAS), Kate Lill provides legal advice and representation to women in prison. Here she explains about Extended Determinate Sentences and how they work.

An Extended Determinate

Sentence (EDS) is a sentence made up of two parts:

1) A custodial term, which is the time you may spend in prison.

2) An extended period of licence.

It’s like a standard determinate sentence, where you spend time in prison and then on licence in the community, however the rules on release and length of licence are different.

EDS sentencing

A judge can sentence you to an EDS if:

You plead guilty or are found guilty by a jury of certain violent, sexual or terrorism offences.

They assess you as being a significant ris to the pu lic of committing further similar offences.

A life sentence is either not available for your offence or is not right in the circumstances.

You have a previous conviction for certain serious offences or the circumstances of your current offence ustifies a prison sentence of at least four years.

The judge must decide whether they believe you are dangerous, and if so, whether an extended period on licence is needed to protect the public from risk of serious harm. They must then decide how long you should stay in prison and determine the extended licence period.

EDS and release

Extended sentences were originally introduced in 2012, but there has been a number of different types since. When you are released and how complicated it is depends on:

The offence

Sentence length

When you were sentenced

For women now in prison serving an extended sentence, it’s most likely they were convicted after April 2015 when the current rules came in. Under this law, someone on an EDS is automatically released at the end of their custodial term, but they are eligible for early release when they have served two-thirds of the custodial period. This is known as their Parole Eligibility Date (PED).

‘Extended sentences were originally introduced in 2012 but there has been a number of di erent types since’

‘Sadly, your licence cannot be ended early unless you appeal your sentence and it’s successful’

Each case must be referred to the Parole Board to consider if the person’s continued detention is necessary to protect the public from serious harm. Only the Parole Board can direct release before the end of the custodial period, and depending on the length of sentence, a prisoner may have more than one parole review if the first does not lead to release.

EDS after release

Once someone is released, they will spend time in the community on licence. The length of time will depend on at what point of the sentence you were released – either as decided by the Parole Board or at the end of the custodial period. You will be on licence until the end of the custodial term if released before it ends, plus the extended period ordered by the court.

As with other sentences, a woman’s licence may be taken away from her if she breaks any of the conditions of her licence and she can be recalled to prison. However someone on an EDS can only be recalled if their behaviour shows they present an increased risk of serious harm or reoffending. They will only be released again before the end of the extended licence if the Parole Board directs release.

The end of an EDS sentence

Although extended sentences were introduced to replace Indeterminate Sentences for Public Protection (IPP) once abolished, they operate differently. Those sentenced to an IPP are subject to

a life licence with restrictions and supervision by probation unless the licence has been terminated. They can be recalled to prison at any point in their life.

An EDS ends once you have completed the extended licence period – the end date being known as the Sentence Expire Date (SED) - unless you have spent time unlawfully in the community before being returned to prison if you have been recalled. This time is added onto your sentence.

Sadly, your licence cannot be ended early unless you appeal your sentence and it’s successful.

How sentences work is complicated and when you are released, and how, can depend on your specific circumstances. PAS can advise you on your sentence and release, along with many other prison law related issues.

Speak to our specialist Women Prisoners’ Caseworker on our freephone advice line (Tuesday mornings, 10am to 12.30pm)

0800 024 6205

Legal aid is available for parole reviews and PAS strongly advises you to call them or contact a solicitor if you are an EDS prisoner who is soon to go before the Parole Board.

The Prisoners’ Advice Service offers free legal advice and support to prisoners throughout England and Wales regarding their human, legal and healthcare rights, conditions of imprisonment and the application of Prison Law and the Prison Rules.

Words: Miriam Minty

Miriam Minty, the Deputy Ombudsman at the Prisons and Probation Ombudsman (PPO), and her team are responsible for investigating complaints from people in prison. She shares an update about the introduction of new peer Prison Ambassadors to support you through the complaints process.

You might remember a year or so ago, my team came out to visit all of the women’s prisons in the country. We were concerned we didn’t get many complaints from women in prison, and lots of the ones we did get weren’t eligible for us to look at.

So we came out to ask you how well you knew the complaints processes in your prison, and your experiences of this process. We also asked you if you had heard of the PPO, and whether you had ever used our complaint resolution service.

You told us our name ‘Ombudsman’ was not easily understood and using the words ‘prison and probation’ in our title added to confusion about whether we were part of HMPPS (and we are not!).

In response, a year ago, in November 2023, we launched Independent Prisoner Complaint Investigations (IPCI), which makes it much clearer that we are

independent and we investigate your complaints.

Following our visits to all the women’s prisons, we’re pleased to see more complaints reaching us from women so we think the publicity about IPCI is reaching you. But we are still concerned about the large number of complaints we get from women in prison that we can’t look into, mostly because you have not been through your prison’s complaints process first.

IPCI Prison Ambassadors

We know that many of you found it helpful to talk to other prisoners who knew the complaints process in your prison. They could tell you where to get forms, let you know what to expect in terms of timescales for the prison to respond, and to let you know about us if you were still not happy when you had completed your prisons local complaints process.

So we decided to launch IPCI Ambassadors. These will be/are women in prison who may already help out in prisons, for example on Prisoner Information Desks, Induction wings etc., so they have a great knowledge of how things work in their prisons. As an IPCI Ambassador, they will also be the ‘go to’ person to help you through the prison complaints processes and help you know how and when to take it further to include IPCI.

20 prisons went live with IPCI

Ambassadors in November, including two women’s prisons, HMP Send and HMP Askham Grange, further prisons will be taking up the programme in the Spring.

IPCI Ambassadors in your prison: My teams are back out again in all women’s prisons over the coming months. Do go and speak to them, let them know if you think IPCI Ambassadors are a good idea and if they would work well in your prison, and how else we can support you in getting things sorted quickly, if things go wrong.

‘20 prisons went live with IPCI Ambassadors in November, including two women’s prisons, HMP Send and HMP Askham Grange, further prisons will be taking up the programme in the Spring.’

Illustration: Drawkit

As this edition’s editorial group we share our thoughts on the health injustice women in prison face, and a health story of one of our group, Lee.

We know people in the community are struggling.

The NHS is on its knees. Tragically people are dying while they wait for operations or treatment.

Imagine being in prison with health problems. It’s a total disaster. When we need a doctor, assessment or hospital treatment, it seems beyond impossible.

One year ago, November 2023, the NHS and HMPPS’s joint review of Health and Social Care in women’s prisons found that ‘the way in which health and social care services are delivered is not always gender or trauma informed re ective of protected characteristics or consistent across the women’s prison estate. Too often, women in prison must access available services rather than services that meet their individual needs’.

We accept all the findings and recommendations in this important report, which was highlighted in the last edition of the magazine. Yet when we read it, while sat in prison with the health problems we and other women around us are experiencing, we feel like it’s missing some of the obvious everyday healthcare injustices.

Just in our small group there are lots of experiences of delayed access to treatment, with a lack of access to information which is scary. We often don’t know what’s happening inside our own bodies, we wait for the prison to allow us medical advice and care. Appointments are cancelled and the prison blames the hospital, but we know it’s also about prisons and the poor organisation and staffing tal ed a out in the report.

‘The Health and Social Care report clearly outlines that women are being failed by healthcare provision across the women’s prison estate. Up at policy level there isn’t a plan to build what is needed, but for us it’s the everyday injustices that are felt so harshly.’

Lee: I’ve been having problems with my bowel and stomach for just under a year; I keep bleeding every time I use the toilet. When I eat food, it feels like it’s stuck. I get really bad heartburn, so bad I panic that I can’t breathe. I keep asking to see the doctor in the prison. hen when I finally get there he tells me, “I think you might need to lose weight”. I left thinking I didn’t come for weight advice, and as a woman it really upset me he said that. What about the symptoms, nothing was done.

I keep going back, complaining and telling the officers this can’t e right. ne day the officers come and get me for the hospital. I go and start from the beginning, telling them my symptoms. They decide I need a camera down my throat. I’m waiting for appointments, all the time worrying about this. I asked the nurse in prison about it and she said it feels like you’re cho ing. I was terrified. he waiting continued, months passed. It gets rescheduled again, I end up having a pre-op appointment over the phone. The nurse from the hospital tells me the jail cancelled six appointments! She also says how urgent it is that I get it checked, as the blood tests they have done have come back as abnormal. I keep chasing, being told “we’re not sure” or “it will be soon”.

I am given another appointment with the jail doctor, she looks on the computer and tells me that all the tests are abnormal and it

is looking like bowel cancer. That I should prepare for the worst because of the results. I didn’t even know what to say. I’m put back in a busy waiting room with all the other girls, my head was falling off. I’m crying but I don’t want anyone knowing my business. They take me back to my pad and yeh I’m just left there with my thoughts, my head all over.

Weeks pass by, then months, all the time I’m asking, “what is going on?”. I sometimes get told its li e h your appointment had the wrong prison number it had to be cancelled, there will be another one soon”. That was over seven months ago. I’m still waiting to go out now. I’m still here asking the same questions. I’m still here living with the same symptoms, worrying. Do we not have a right to care? Listen to other women like me, look at the healthcare report, see what is happening inside jail.

The Health and Social Care report clearly outlines that women are being failed by healthcare provision across the women’s prison estate. Up at policy level there isn’t a plan to build what is needed, but for us it’s the everyday injustices that are felt so harshly. The delayed access to medication, being given the wrong drug, and just the way we are made to feel as if we don’t deserve access to specialists.

The report refers to a lived experience board, bringing women’s voices from prison into these conversations, no matter how critical they are – this has to happen and urgently. We want to see action.

We are in prison for punishment, yet it feels like the way we are treated in relation to our healthcare is added punishment. We are always a prisoner, never a patient.

My experiences of the appeals process was a total nightmare, which I had to learn along the way. In writing this in conversation with lawyer Naima Sakande, who has lots of knowledge and has been part of a project supporting women in prison with criminal appeals, I hope other women in prison can be better prepared.

Words: Kelly

Illustration: Ikon Images

Kelly: In 2012, my sister and I were found guilty of murder under the joint enterprise law – joint enterprise is when someone may not have committed the actual crime but gets found guilty by association because of what they should have foreseen would happen. We were both absent when the murder happened but were found guilty and sentenced to 22 years. I landed on my sentence and didn’t have a clue. I contacted legal teams and had some bad experiences but have found a way to take my appeal forward. Over the years I have got my head around the law and written more than a few thousand letters to MPs telling them what is happening in our (in)justice system. Campaigners, including my family, all piled down to London in February 2016 for the Supreme Court ruling on joint enterprise. The highest judge in the country said the law had taken a ‘wrong turn’ with the use of joint enterprise in sentencing. We was jumping for joy, and really thought this is it. Our appeal started moving and was heard in 2017. What happened next has been the toughest part of my journey so far.

Kelly: How long does an average appeal take Naima? And from your experience why does it take so long?

Naima: The average wait for a sentencing appeal could be anything up to six months and just over a year for a conviction appeal. But this is just the time it takes for a case to reach the Court of Appeal. Before the case can be heard, there’s a lot of work to be done by the legal team of the person making an appeal (the appellant). The team might have to look at new evidence, instruct new experts and find a arrister who will do the legal work and take the case forward.

Kelly: When our appeal was heard, we thought we would be attending by video link, but the Judge closed the hearing so no one was allowed in. We were not allowed to hear what was being said, never mind being able to speak ourselves. We heard about the outcome from family who read it in the papers. People in charge of the system say they want ‘open and transparent’ justice. Our appeal was heard behind closed doors. A feeling of being totally out of control when the biggest decision of your life is being made. No one has ever given us an explanation for why this happened

Kelly: Why do you think this happens Naima? What can and should women going to appeal expect in how they can take part in their appeal process?

‘I find it appalling that any court should decide someone’s fate without their presence.’

Naima: The actual appeal can feel separate from the person who is requesting it because lawyers can spend a long time arguing over technical points of law. The language used is often very old fashioned and hard to understand if you don’t have any legal training. It can be hard on those waiting for a result that could change the rest of their lives.

You should be allowed to attend your appeal hearing if the right to appeal has

‘It took months to convict us, we’ve spent years to try and fix this wrong. We will never give up the fight.’

Even when our system for fixing the wrongs of the criminal justice system is so broken, it’s important that women continue to fight for their rights. Only by showing up, calling out mistakes and being brave enough to not accept the fate you’ve been dealt can the system ever correct its mistakes. Women are often taught not to complain or make a fuss. It’s important that we use our voices to not allow injustice to happen.

Kelly: How can women access legal aid and support if they want to appeal Naima?

been given by the Single Judge – this is the person who looks at all of the cases and has the power to either allow or not allow an appeal (this is called ‘leave’). If they allow your right to appeal, the appeal is heard by a full panel of three Judges, and you’re able to watch the hearing. If they don’t allow the appeal, you can either choose to drop the appeal, or renew your application to the full court. If you renew your application, you lose the right to attend the full court hearing. I find it appalling that any court should decide someone’s fate without their presence.

While attending court might in some cases be limited by these rules, women appealing can and should be fully involved in preparing their case for appeal. A strong relationship with your legal team should allow you to share information and prepare the strongest possible case. While your lawyers are experts in the technical parts of preparing an appeal, and their advice should be listened to, you remain an expert on your own life and experience.

Kelly: Can women win appeals when they are wrongly convicted Naima? And why are so few appeals successful?

Naima: Yes, women can win appeals.

Naima: There is a wonderful organisation called APPEAL*, that provides free legal aid support for criminal appeals. They are a small charity of lawyers, investigators and advocates. They have a Women’s Justice project that deals sensitively to women’s particular needs. They are not able to take on every case, but they can provide referrals to other services that may be able to help.

Kelly: After the knock back it has taken a lot; we’ve had to put it right to the back of our heads. We are back in a new appeal. The legal team didn’t give up and neither can we. It took months to convict us, we’ve spent years to try and fix this wrong. We will never give up the fight.

For more information:

Write to APPEAL at APPEAL, 72-75 Red Lion Street (6th Floor), London, WC1R 4NA. JENGbA, Joint Enterprise Not Guilty by Association, is a grass roots campaign run by volunteers, many who are family members of people serving mandatory life sentences for crimes committed by others. It campaigns against joint enterprise sentencing.

For more information mail: JENGbA, Resource for London, Office 4, 1A, 4th Floor, 356 Holloway Rd, London N7 6PA Call: 0203 582 6444

F S T H G I R M Q K F M N

Find the words - time yourself!

RSKFK IO QJ N

MN PC OM MU NI

RO PP US AF RI

SE ER ZX AU LG

VW MU EI GA CU

ND PP RH UM LU

KJ ON LQ AG JV

LK EOEO WB XF

SSS YJ BY DD U

SG VUZD NM KT

YTYS LG FY EF

FX MH NE YY EN

JN ZV CL SY RO

How to play? Fill in the grid so that every row, every column and every 3x3 box contains the numbers 1 to 9, without repeating the number.

9 2 3 6 4 7 8 1 2 9 1 4 2 1 2 9 4 8 6 6 7 2 4 2 3 4 2 6 6 3 1 5

LEGAL & GENERAL ADVICE

Prison Reform Trust Advice and Information Service: 0808 802 0060

Monday 3pm–5pm Wednesday and Thursday 10:30am–12:30pm

Prisoners’ Advice Service (PAS):

PO Box 46199, London, EC1M 4XA

0207 253 3323

Open Monday, Wednesday and Friday 10am–12:30pm and 2pm–4:30pm, Tuesday evenings 4:30pm–7pm

Rights of Women

l Family law helpline

020 7251 6577

Open Tuesday–Thursday 7pm–9pm and Friday 12–2pm (excluding Bank Holidays).

l Criminal law helpline 020 7251 8887

Open Tuesdays 2pm–4pm and 7pm–9pm, Thursday 2pm–4pm and Friday 10am–12pm

l Immigration and asylum law helpline 020 7490 7689

Monday 10am–1pm and 2pm–5pm, Thursday 10am–1pm and 2pm–5pm

HARMFUL SUBSTANCE USE SUPPORT

Frank Helpline: 0300 123 6600

Open 24 hours, 7 days a week.

Action on Addiction Helpline: 0300 330 0659

National Domestic Abuse Helpline: 0808 2000 247

Open 24 hours.

LGBTQ+

Bent Bars

A letter writing project for LGBTQ+ and gender non-conforming people in prison.

Bent Bars Project, PO Box 66754, London, WC1A 9BF

Books Beyond Bars Connecting LGBTQIA+ people in prison with books and educational resources.

Books Beyond Bars, PO Box 5554, Manchester, M61 0SQ

HOUSING

Shelter Helpline:

0808 800 4444

Open 8am–8pm on weekdays and 9am–5pm on weekends.

NACRO information and advice line:

0300 123 1999

FAMILY SUPPORT

National Prisoners’ Families Helpline: 0808 808 2003

Open Monday-Friday 9am–8pm and on Saturday and Sunday 10am–3pm (excluding Bank Holidays).

OTHER Cruse Bereavement Care 0808 808 1677

Open Monday–Friday 9:30am–5pm, Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday 9:30am–8pm and weekends 10am–2pm.

Samaritans

116 123

Disclaimer: please be aware that some helplines will be operating under new opening hours due to the COVID-19 pandemic.