S TILL I RISE

What does ‘mental wellbeing’ mean to you?

Our theme of this edition is mental health. This is a big subject, and there are so many different ways our mental health can be affected. But how can we keep a balance?

We would like to hear about your experience of mental health and the things you do or know about to achieve mental wellbeing. Things you’ve learnt, things you’ve reflected on, or things others have done to support and maintain your mental wellbeing. Mental wellbeing can be about how you feel about yourself, your life, what you feel you can do, and good mental wellbeing helps you to cope with the things that happen in your life.

What helps you? Is it time in the sun, reading a book, yoga, working out, chatting with friends, or do you receive professional support. Whatever it is we want to hear. We have themed this edition’s competition around this so you can share your artwork, writings, or other means of expression. We’ll select entries to be published in the next edition and there will be a prize for the winning entry. We hope you’ll take part.

Rules for entering the competition:

• Feel free to give your own interpretation of what mental wellbeing means.

• If it’s a story, essay, interview, or article (fiction or non-fiction) please write 500 words or less. When handwritten, this is between 1½ and 2 pages of A4.

• An entry can also be a poem, drawing, painting or a collage

• Please include a completed consent form (see page 65) with your entry and send it to Freepost – WOMEN IN PRISON (in capitals).

Without the consent form we are unable to include your submission in the magazine.

One entry will be selected as a "Star Entry" with the writer receiving £20 (only entries that include the consent form on page 65 can be considered for "Star Entry").

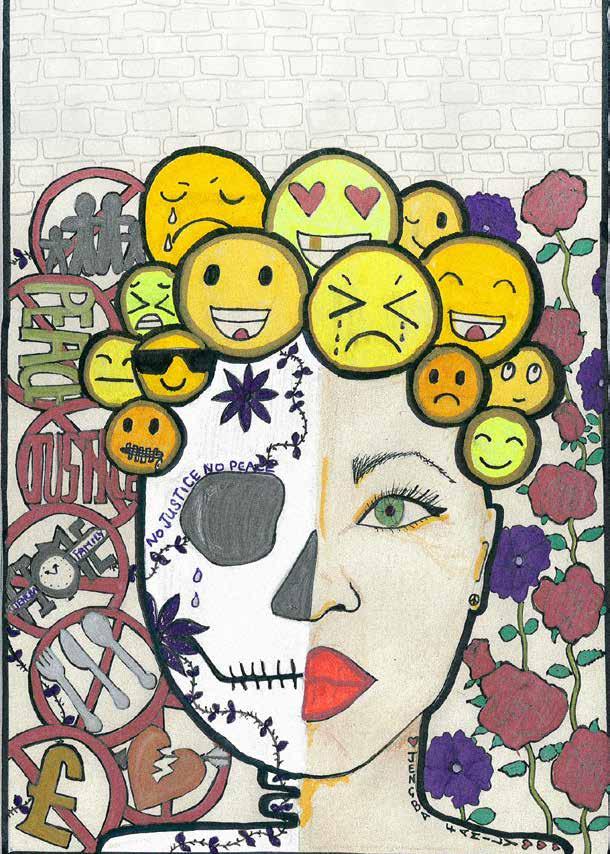

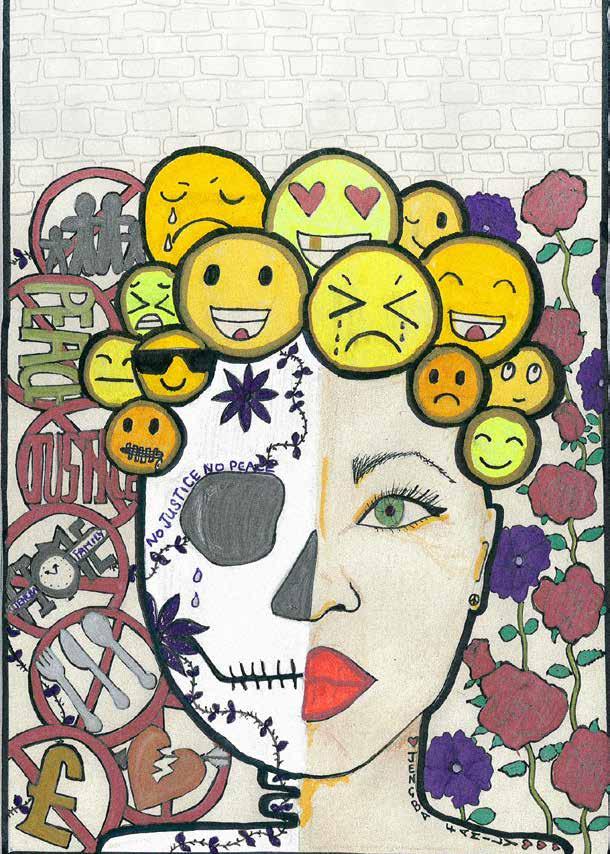

Cover artwork by Kelly, HMP Styal.

Women in Prison (WIP) is a national charity founded by a former prisoner, Chris Tchaikovsky, in 1983. Today, we provide support and advice in prisons and in the community through hubs and women’s centres (the Beth Centre in London, WomenMATTA in Manchester and in partnership with the Women’s Support Centre in Woking, Surrey).

WIP campaigns to reduce the number of women in prison and for significant investment in communitybased support services for women so they can address issues such as trauma, mental ill-health, harmful substance use, domestic violence, debt and homelessness. These factors are often the reason why women come into contact with the criminal justice system in the first place.

WIP's services are by and for women. The support available varies from prison to prison and depends on where a woman lives in the community. If WIP is unable to help because of a constraint on its resources, it endeavours to direct women to other charities and organisations that can. WIP believes that a properly funded network of women's centres that provide holistic support is the most effective and just way to reduce the numbers of women coming before the courts and re-offending.

WIP’s services include...

• Visits in some women’s prisons

• Targeted ‘through the gate’ support for women about to be released from prison

• Support for women in the community via hubs for services and women’s centres in London, Surrey and Manchester

• Still I Rise A magazine written by and for women affected by the criminal justice system with magazine editorial groups in some women’s prisons

Got something to say?

Please contact Women in Prison at the FREEPOST address below. Please include a completed consent form with your query; turn to page 65 for more details.

Email us on: info@wipuk.org

Mail us on: FREEPOST Women in Prison

If you enjoyed reading the magazine and want to donate towards the production of our next edition, please scan below:

Please know that whatever you are going through, a Samaritan will face it with you, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Call the Samaritans for free on 116 123.

CONFIDENTIAL

Our service is confidential. Any information given by a service user to Women in Prison will not be shared with anyone else without the woman’s permission, unless required by law.

In this edition we look at at mental health.

This is such an important subject as we know there’s an increasing number of women in prison with mental health issues – read page 28 for more information on these figures.

On page 10 we have a fantastic interview with Lord Bradley who came into HMP Styal to be interviewed by a group of women in prison. If you don’t know Lord Bradley, he’s a Labour peer who wrote a government report on mental health in prison, which although sometime ago now, is still hugely influential. He continues to work to see his report recommendations actioned – many of which have already been successfully implemented.

We have personal stories from Kelly and Lee, both women in prison, about their own mental health experiences

on pages 16 and 22.

And we have more of your thoughts on what mental health means to you as part of a photography exhibition working with photographer Eva Fraser and influenced by the Japanese thinking of Kintsugi – putting broken pieces back together with gold.

We also have opinion, support, and news pieces about mental health, physical health, recipes and more of your creative work in our All Yours section.

We hope you enjoy this edition in which so many of you have contributed.

Please do reach out to someone if you are struggling with your own mental health, support is there for you.

Kate Head of Prisons and Co-Production

Project Manager: Kate Fraser

Art direction & production: Henry Obasi & Russell Moorcroft @PPaint

Production Editor: Jo Halford

The magazine you are reading is free for all women affected by the criminal justice system in the UK.

We send copies to all women’s prisons and you should be able to find the magazine easily. If you can’t, write to tell us. If you are a woman affected by the criminal justice system and would like to be added to our mailing list for free, please contact us at Freepost WOMEN IN PRISON or info@wipuk.org

The publishers, authors and printers cannot accept liability for errors or omissions. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of Women in Prison. Applications should be made directly to Women in Prison.

Registered charity number 1118727

Women’s Centres run by WIP

Women’s Centres where WIP staff are based

WomenMATTA – Manchester

The Beth Centre – Lambeth, London

Women’s Support Centre – Woking, Surrey

Women’s Prisons

HMP Low Newton – near Durham

HMP Askham Grange – near York

HMP New Hall – near Wakefield

HMP Foston Hall – near Derby

HMP Styal – near Manchester

HMP Drake Hall – Eccleshall, Staffordshire

HMP Peterborough

HMP Eastwood Park – near Bristol

HMP Downview - Sutton, Surrey

HMP Send – Ripley, Surrey

HMP Bronzefield – Ashford, Surrey

HMP East Sutton Park – Maidstone, Kent

HMP Cornton Vale – Scotland

Linda Poindexter

Supporting your mental health

Katie Fraser, Women

in Prison Head of Prisons

and Co-Production, talks about the theme for this magazine issue, and shares what we mean when we talk about mental health and how this differs from mental illness.

It seems like everyone is talking about mental health these days. Stormzy shared his decision to give up smoking weed due to the impact on his mental health, and he raps about depression in his single Lay Me Bare. Zayn Malik opened up about having an eating disorder and struggling with anxiety, and Prince Harry has given interviews about the loss of his mum and how not grieving properly has affected his mental health.

But it’s not just celebrities talking about mental health. Spending time with women in prison our conversations often turn to mental health and how, in some cases, having poor mental health and being unable to access the right community services has led to their involvement in the criminal justice system. That’s why we’ve chosen mental health as our theme for this issue.

What is mental health?

What do the words ‘mental health’ really mean and how much are we able to control our own mental health? The World Health Organisation describes mental health as ‘a state of mental wellbeing that enables people to cope with the stresses of life, realise their abilities, learn well and work well, and contribute to their community’*. But having poor mental health is often confused with having a mental illness, which is quite different. Mental health refers to a person’s state of mental wellbeing whether they do or don’t have a psychiatric condition. Everyone has mental health, sometimes good and sometimes not so good, but not everyone has a mental illness. This is where things can seem confusing. We can make lifestyle changes to improve our mental health, like eating and sleeping well

or taking exercise, but with mental illness often these changes alone may not help, and you may need to take medication to manage the condition. Mental illness covers a huge range of conditions that include eating disorders like anorexia nervosa and bulimia, trauma related conditions such as post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and psychotic disorders like schizophrenia or personality disorders.

Over the past few years, there have been lots of high-profile campaigns to reduce stigma around mental health but less discussion around mental illness. A lot of focus has been around recovery and wellbeing and how to prevent poor mental health, but this may not be possible if you have a mental illness. Many people still feel a sense of shame talking about a diagnosis of mental illness.

Your mental health and being in prison

When you come to prison, you may start to feel like your mental health is deteriorating and it’s hard to manage it in jail, where you can’t do things like go for a walk in the park or have a long soak in a bath to help. The important thing is to not keep all these feelings inside and to talk about symptoms you might be experiencing. All prisons have a dedicated Mental Health In Reach Team who can help and refer you for specialised support, if that’s what you need. There will be other women feeling the same way and being able to talk about it together can go a long way to making the length of your sentence a little easier. Speak out – you have nothing to be ashamed of.

*Source: www.who.int/health-topics/mentalhealth#tab=tab_

Getting to know Lord Bradley

Words:

Women at HMP Styal

Lord Bradley is a Labour peer whose review of people with mental health problems and learning disabilities in the criminal justice system, and its recommendations, continues to influence work in this area. He recently visited women in HMP Styal and they interviewed him about his work.

Becky: You’ve had an interesting career, mostly focused on public and community service. What drives you to do this work? At school, I spent most of my time running around playing sport and studying wasn’t my priority. I then went into accountancy which I found uninspiring. In the late 60s I watched Cathy Come Home, about homelessness, which was shocking. A new charity called Shelter held a meeting to talk about Cathy Come Home and I went along. At that meeting it was suggested we start a Shelter group in Sutton Coldfield and I became the committee treasurer.

We fundraised for homeless people and engaged with housing associations and social housing groups. Taking families out into the countryside and seeing these children made me realise I didn’t want to be an accountant, so I went on to study Social Sciences and then Housing Research. I got a job in Manchester as a housing researcher, following which I chose a political career as I wanted to make a difference quicker for homeless people.

Nicole: What do you feel was the most important recommendation in your report when considering it nearly 15 years later?

In 2007, I was asked by the Labour Government to do a review of people with mental health problems, learning disabilities and other complex needs. To look at why so many ended up in prison and how we could stop these people being in prison rather than getting help in the community.

The most important recommendation implemented was to create teams of people − mainly learning disability nurses, mental health nurses and other health professionals − based in police custody. So at the first point of contact on arrest someone’s mental health could be assessed and any issues taken into account before making charges.

Should a decision be made to charge, this information is then available in court to help them decide the most suitable sentence. There is now 100% coverage of these Liaison & Diversion teams nationally in custody suites and in court, alongside the probation service and the Crown Prosecution Service.

When I handed in my report to the government with my recommendations. I said to them that if you accept the recommendations, I’m not going away until they’re implemented. And here I am 17 years on, and I’m working on them.

I said to them that if you accept the recommendations, I’m not going away until they’re implemented. And here I am 17 years on, and I’m working on them.’

Stacey: You proposed building up services in communities to stop people going into the CJS. My offence came about because of a lack of mental health support. How much has work in the community advanced?

Not as far and as fast as I’d like. If you’re on a waiting list, your health will likely deteriorate while you’re waiting to be seen. That’s a danger as one of your responses might be to get involved with the criminal justice system during that time. The capacity in mental health services is poor compared to physical health. Most resources in the NHS go into physical health and not mental health. It’s getting better, but until we build up that capacity it’s a problem.

There’s a draft bill before parliament to have a new Mental Health Act, with a number of good recommendations, including prison should never be used as a place of safety. There are too many people who end up in prison because nowhere else will take them at that point.

I’m a strong advocate for community sentences. At the moment we have a community sentence rolling out that has a mental health treatment requirement and this would run alongside a drug treatment

or alcohol treatment requirement where necessary. But the Courts still need to be convinced there’s capacity in the community for those community sentences to be successfully completed.

Nadia: As a cancer survivor with long term post chemotherapy issues and as a diabetic, I recognise the link between nutrition and wellbeing. One of the recommendations in your report was Primary Health Care must include a range of non-health activities to support wellbeing in prisons. Would this include access to better nutrition and activities around food and wellbeing?

Yes, absolutely. When I was doing the report, wellbeing wasn’t talked about much, and it now is. It’s the link between mental and physical health. Poor mental health can often be a consequence of poor physical health. Poor physical health can be as a result of bad sleep, poor food, and little exercise. So there should be a range of activities available in prison along with other wellbeing sessions that provide an opportunity to talk.

Rachel: Why do you think so many people with mental health problems still end up in prison?

‘Poor mental health can often be a consequence of poor physical health. Poor physical health can be as a result of bad sleep, poor food, and little exercise. So there should be a range of activities in prison along with wellbeing sessions.’

It’s the same point around the capacity of services being able to deal with the amount of people who need the services. And crucially, it’s about providing an early assessment, not waiting until people are involved in a criminal justice pathway before recognising they have a mental health issue, a learning disability or other complex needs. That early intervention should be there before getting into police custody. There should be more preventative and early intervention.

For a few years now we’ve been trialling street triage, with police officers and mental health nurses working together in communities − a police officer is either with a mental health nurse in their car or has one available from a call centre. When someone shows symptoms of a mental health crisis the nurse can access their records and tell the police they should be on meds etc. and can reconnect them to relevant mental health services, and take them to a place of safety and not a prison.

Stacey: That’s what should happen, but I don’t think it does. Police are just not properly trained on mental health. I’m not expecting police officers or prison staff to be experts in mental health, but it’s about being aware and being given sufficient training. To gain an understanding of mental health and the role different agencies and organisations play in mental health, really all these agencies should be trained together. They’re all often working with the same person, and all those organisations understanding what each other does would have huge benefits in the long term.

Tina: What would you say to women with mental health issues in prison who might be struggling?

We have to stop, where appropriate, women going to prison in the first place. To divert them either into a community setting where they can be supported by Women’s Centres, or not charge them at all. But inevitably some women will end up in prison. Some for the severity of their crime, but too many served with sentences for less serious crimes would be better serving community sentences where they can be in contact with their families.

Emma: A recent HMPPS Inspectorate report highlights that the criminal justice system is seriously failed by mental health services in England and Wales, what are your thoughts?

I one hundred percent agree and that is just another impetus to try and speed up change. There are far too many women on short term sentences which are of no benefit and far too many women on remand which we know causes immense damage.

Rebecca: What do you think the current government should be doing now to help people in prison with mental health problems?

I would like to see the Mental Health Reform Act go through parliament so we can ban prisons being used as a place of safety. We need to tackle short term sentences and make sure there is capacity to support people effectively in the community and one way of doing this is to invest in Women’s Centres. And if people have to go to prison, we have to ensure they get the services they need when they need them.

Mental health & me

Words: Kelly Illustrations: UP Studio

As a child Kelly suffered physical insecurities. On leaving school she began drinking and smoking weed to mask her paranoia. And during both her pregnancies she fell into a black hole of depression. Now in prison, convicted under joint enterprise law, she shares how she’s learnt to do things that are good for her mental health.

Iwas a kid who could play by myself all day long, always getting lost in my thoughts. At the age of 11, I was put into boarding school and had to grow up fast. I remember being on diets from the age of 12, and hating my body; feeling fat and just wanting to be like the other kids who could eat whatever they wanted. I started to hate being around other people. The only way I could cope was to become the joker but inside I was really struggling. I couldn’t even eat in front of people. I would sit with my back to everyone in the dinner hall.

When I left school it was another new world to deal with. I connected with a mate I grew up with. We started to drink and then smoke weed. It was a good escape as it made me relax and forget my paranoia. By the time I went to college I was smoking weed every day. I wasn’t the fat kid any more but I was still struggling. I would get anxious if men paid me attention and I started being rude so they would leave me alone. All my friends had boyfriends, but I kept men at a distance. Then at the age of 18 I had my first kiss. But only because the drink had made me brave enough.

Just before I turned 19, I found out I was pregnant. I was scared to tell anyone, but my sister told my boyfriend and my parents who said they would support me and the baby. This was a huge weight off my shoulders. My boyfriend was scared and told me to get rid of the baby, so that was the end of him. I was excited at the thought of being a mum but I was also dealing with the changes in my body, and with all the hormones and the relationship break up I was broken hearted. I felt like my mum and

‘Take the time to really see and understand how people could be feeling. It might be you one day.’

dad didn’t listen to me, and alone and pregnant I became the joker again.

I went into a long four-day labour and gave birth to the best thing that’s ever happened to me. I should have been happy, but it felt like I was going deeper and deeper into a black hole. I had a good life and an amazing baby but I still couldn’t escape the negative thoughts in my head. I got meds from the doctor and saw a psychologist, but I still felt stuck, so I went back to my old way of smoking weed to cope and it kind of worked.

I did the same when my second baby was born nine years later. I was still fighting for my brain to work and appear normal, faking a smile on my face. The blacker the hole I was in, the more weed I smoked and the more I drank. I just pretended I was okay.

I had a house, kids, paid my bills. To the outside world everything looked perfect. Anxiety, depression and paranoia were an everyday battle, but I masked it by spoiling my kids with everything they wanted or needed. They were like meds for me − they never knew what my brain was doing to me.

Then the nightmare happened. I was convicted under joint enterprise law for something I didn’t do. Knowing I was innocent and being separated from the kids broke me and all the black thoughts came rushing back. All the old symptoms returned and I was back to being the joker again.

But over time I’ve learned how to support myself and do things that are good for my mental health. I know when I need time alone and I take myself away until the tiredness leaves me. I keep myself afloat by fighting the injustice of my sentence and by helping other women in here; being a Peer Mentor and showing them that life is still worth living, even in jail.

I have an amazing dad who keeps me going and a little queen, but the nights

when the sleep doesn’t come are still hard. I would say to you that just because someone looks okay on the outside, it doesn’t mean they are. Take the time to really see and understand how people could be feeling. It might be you one day.

‘Over time I’ve learned how to support myself and do things that are good for my mental health.’

My mental health journey with bipolar disorder

Words: Lee Illustration: PPaint

Lee, a woman in prison, shares her experience of growing up with a father who had bipolar disorder and her own journey in discovering she too has bipolar disorder.

I’m a 30-year-old Irish Traveller and I got married at a very young age. I grew up in a household where I didn’t know anything about mental health. I didn’t know anyone who was so called ‘crazy’that’s what my family thought you were if you suffered with mental health issues.

Growing up, I started to notice I was a bit different from everyone else, that I could have periods where I felt manic, followed by periods when I felt low and depressed. I felt like I was ‘one of them crazy people’ but I was too afraid to say anything to my family. So I kept it to myself, which looking back wasn’t the right thing to do. If I knew then what I know

now about mental health, my life might have been so different.

My father was an alcoholic who could be the best father in the world. At times he would buy whatever we wanted, but sometimes it was way too much and he would spend ridiculous amounts. He would buy everyone everything, basically just giving his money away and displaying manic behaviour. But the drink was my father’s mask, and we all put his behaviour down to his drinking.

When I turned 16, I started to realise I was doing similar things to my dad, but I thought nothing of it. I thought it was normal. When I was 17, my dad went to

have treatment for his drinking and a doctor diagnosed him with bipolar disorder. It made him really upset because men aren’t supposed to talk about what’s going on with their mental health and he’s from a generation where, ‘if there’s something wrong with your head, you need the county home’ − that’s what we called the mental hospital. My family were embarrassed and ashamed there was something wrong with the head of the family.

When I was a newlywed, I turned to my father-in-law and told him I thought there was something wrong with me. As a new bride, it should have been the happiest time of my life, but I was so up and down − and I was still afraid to tell anyone. The first person I told was my brother’s wife. She sat me down and told me not to be ashamed or embarrassed, and that mental health problems can happen to anyone. She took me to a doctor and I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

years things have changed in our culture. It’s come out that more Traveller men and women are dying from suicide because they feel they can’t talk about their feelings.

I was terrified to tell my dad, but I did. It took me a long time to be okay with the person I am. I can’t help who I am and I can’t help being bipolar. It’s not my fault my community are old-fashioned in their views about mental health. In the last few

It used to be that a man’s got to be strong and look after the family and show no weakness. Luckily, times are changing and in 2024 there is less stigma attached to mental health. I don’t feel ashamed anymore because I understand it and you shouldn’t either if it happens to you. Things are starting to change and we have to be the ones to stand up and be proud of who we are..

‘I don’t feel ashamed anymore because I understand it and you shouldn’t either if it happens to you.’

PUTTING BROKEN PIECES BACK TOGETHER WITH GOLD A PHOTOGRAPHY EXHIBITION ON MENTAL HEALTH IN PRISON

In our own words: putting broken pieces back together with gold

Words: Women from HMP Styal Photos: Eva Fraser

A group of women in prison have spoken about what mental health means to them, words which photographer Eva Fraser has powerfully captured in accompanying photography on their behalf. Influenced by elements of the Japanese Kintsugi, putting broken pottery pieces back together with gold, this has been brought together as a thought-provoking exhibition which we’re excited to share with you.

There’s constant talk about mental health but not everyone’s voice is being heard. As a group of women in prison, we see and experience the impact of poor mental health on a daily basis. We are the statistics discussed by commissioners and strategy leaders.

With the support of Women in Prison we’ve created this exhibition to let you know what we think about when we hear the words mental health. We want to share our fears and frustrations and let you know what sustains us.

We incorporate elements of Kintsugi

into our images – the Japanese art of putting broken pottery pieces back together with gold – built on the idea that in embracing our flaws and imperfections we can create an even stronger, more beautiful piece of art. Some days we feel broken in a flawed system, but we survive, stronger and more beautiful. And still hopeful.

We hope you enjoy our images taken by Eva who was our ‘lens’ in the community. She took our words and interpreted them into the images you see before you.

Eva Fraser

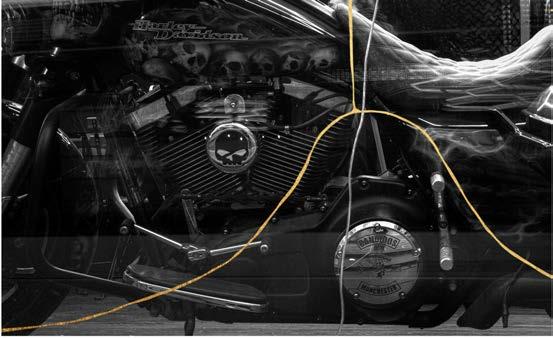

“When I

hear the words mental health it makes me think about doctors chucking tablets at people without actually understanding or knowing why they are feeling that way.

I go on my motorbike to get release from my mental health!”

emma

“When I hear the words mental health it makes me think about services letting people down and not helping them with their thoughts or feelings.”

charlotte

Some days we feel broken in a flawed system, but we survive, stronger and more beautiful. And still hopeful.

“Something that helps my mental health when I’m down is putting my headphones on and listening to music while I paint or draw pictures. It calms me and takes my mind to a better place.” kelly

“Mental health means to me, drinking as a teenager to cope with what was going on at home, drinking until I passed out. Then as I got older it seemed as if my problems got worse. So I began to use cocaine. Then when that became normal I went to harder things like heroin and crack. Just using to feel normal, committing petty offences, just to get my fix to feel normal.” louise

“When I hear the words mental health it makes me think about being trapped inside my head, travelling around in the labyrinth of thought until I am lost to all sane reasoning. Travelling ever, but reaching nowhere. In the end, a prisoner of my mind, still and standing just where I started.” natalie

Eva Fraser

“To help my mental health I meditate and take my mind to my safe place, a beach, waterfalls, hot sun. Laying just listening to the birds sing and the waves crash. Not thinking of anything else.”

maureen

“When I hear the words mental health, it makes me think about being broken inside and feeling lost, keeping everything to yourself and thinking you are on your own.”

nicole

“When I hear the words mental health, I think there’s not a one size fits all. It’s unique to each individual person, and it takes time to work through. My mum was a counsellor and I have so much respect for her and the people who help people with mental health issues. For me personally, I’ve always been a positive person, but coming to jail I’ve experienced a form of anxiety. Probably down to having lost control of my own life.” nadia

“When I think of mental health, I think of all the challenges and struggles I have had growing up and spiralling into a dark, lonely place.”

sarah

“When I hear the words mental health, it makes me think about severe depression, not wanting to get dressed or out of bed. The doctors keep changing your medication, usually a sedative.”

tina

“When I hear the words mental health it makes me think about being let down by the services. My voice not being heard when trying to explain my symptoms, which are hard enough to live and deal with, never mind speaking to deep unhelpful ears.”

rachel

Eva Fraser

When I think about mental health, I think about past trauma and negative relationships growing up. But that doesn’t mean you can’t achieve your goals and rise above all the hurt and pain caused. Stay strong and keep going, we can do this.”

rebecca

“When I hear the words mental health, it makes me think of suicide, depression and anxiety. It also makes me think of my mum who suffered with it back in the day. She was traumatised from the electric shock treatment she received, so has a massive phobia of hospitals due to the treatment she received for her mental health.”

stacey

“When I hear the words mental health, I think of the NHS over run with young people desperate for hope.” sasha

This exhibition will be on show at HMP Styal and online on our website.

Are we criminalising mental health?

Words: Dr Maria Leitner IIlustration: Kee

Dr Maria Leitner the Research Lead for Open Justice, formerly in prison at HMP Styal, talks about the high number of women suffering from mental health issues in prison and raises questions about the criminalisation of mental health.

Numbers for mental health in prison are poor. Last year there were 93 deaths by suicide and 67,773 incidents of self-harm1. Suicide numbers have doubled in the past ten years and self-harm by women increased by 38% last year2. It’s estimated that 9 out of 10 people in prison now suffer from a mental health disorder or learning disabilities 3 . Care and Supervision Units (CPUs) are being used as places to keep people because mental health needs can’t be met in the main prison. Women are sent to prison as a ‘place of safety’ under the Mental Health Act, or for their ‘own protection’ under the Bail Act. With prisons fast turning into mental health wards we need to look at the key causes. But addressing structural failings within prisons will not solve the main

issue, we need to find out why so many people with mental health problems are being sent to prison.

Having done time in HMP Styal myself, I can personally say quite how ‘insane’ levels of mental ill health are in prison. Not just subtle, difficult to diagnose conditions, but obvious mental disturbance. I came across many stereotypes of mentally disturbed people. One woman held long conversations with flowers; failed to recognise the need to eat and, in spite of her extremely large bump, denied she was pregnant. So what was the judge thinking sending her to prison?

The idea that a person is of sound mind and can choose rationally to carry out a criminal action (Mens Rea) is supposed to be at the heart of a guilty verdict. With 90% of those in prison potentially with one or more mental health disorders are we

really punishing the intentionally guilty, or just criminalising mental health?

Looking at 60 years of data, researchers 4 have found that a 93% decrease in the number of NHS psychiatric beds has contributed to a 208% increase in the prison population. The number of women prisoners has increased more than four times.

My astonishment at an unknown judge’s decision to imprison the woman who talked to flowers is echoed in both the Corston Report 5 and in an RCP position statement 6. Both highlight an obvious solution that treatment is a more effective mechanism of crime prevention than punishment. Knowing this, wouldn’t the ‘rational mind’ focus on mental health provision rather than on sending people with a mental health disorder to prison?

For more information: www.openjusticeinitiative.com

1. Safety in Custody Statistics England and Wales: Deaths in Prison Custody to December 2023 Assaults and Self-Harm to September 2023, published online 25th January 2024

2. Open Justice (2023) The ‘Special Case’ of Women in the Criminal Justice System in England and Wales www.openjusticeinitiative.com

3. Durcan, G. (2023) Prison Mental Health Services in England, 2023 Centre for Mental Heath

4. Wild, G., Alder, R., Weich,S., McKinnon, I. & Keown, P. (2022) The Penrose hypothesis in the second half of the 20th century: investigating the relationship between psychiatric bed numbers and the prison population in England between 1960 and 2018–2019 The British Journal of Psychiatry (2022) 220, 295–301. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2021.138

5. Corston, J. (2007) The Corston Report: a review of women with particular vulnerabilities in the criminal justice system London: Home Office. https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ ukgwa/+/http:/www.homeoffice.gov.uk/documents /corston-report/

6. Royal College of Psychiatrists (2021) Mental health treatment requirements (MHTRs) Published online

Cooking together & sharing cultures through recipes

Sharing food and eating together is proven to have a positive impact on our mental and emotional wellbeing. Both in the act of cooking and in socialising with others as we nourish our bodies. Two women in prison kindly share their recipes with us.

ELISHA’S CORNED BEEF HASH

An easy meal to make, which is both comforting and filling.

Makes four portions

3 tins of potatoes

1 tin corned beef

3 carrots

1 onion

1 tub gravy granules Salt Pepper Method

l Chop your carrots into either slices or cubed pieces

l Peel and chop your onion

l Then cut your corned beef into cubes

l Bring a pan of water to boiling and add your carrots

l Cook your carrots for 15 minutes then add your onion and potatoes and boil until soft

l Add your corned beef to the mixture and season with salt and pepper to taste

l Add your gravy granules but not too much as they will thicken as they cook

l Cook for a further 10 minutes until the whole thing is thick like a stew. Add more gravy granules if necessary to thicken and for taste.

Enjoy!

by

OLGA’S PANCAKES

Who doesn’t love pancakes, they’re simple and go with so many different things, These sweet pancakes will go well with lemon, jam, or whatever you fancy.

Makes 10 portions

3 eggs

400ml milk

Pinch of salt

50g sugar

2 teaspoons sunflower oil

200g self-raising flour

Method

l Mix your eggs, milk, and sugar together in a bowl

l Add the flour and keep mixing, making sure there are no lumps

l Add the salt and oil and mix together

l Pour just a small drop of oil into the frying pan and heat until hot

l Pour a thin layer of the mixture into your pan

l After a few minutes ease away the side to see if the bottom is cooked

l Once the bottom is cooked flip it over and cook the other side before removing to eat.

Illustrations

Camille

Doing Porridge: how women in prison experience food

Words: Doing Porridge project team

Illustration: Nifty Fox Creative

The Doing Porridge project team from the University of Surrey have for the past two and a half years been exploring how women experience food in prison. They share details about the Doing Porridge project and tell us what they discovered.

We’ve spoken with over 80 women across four prisons to explore the role of food in prison. We’ve held art workshops, focus groups, interviews, and have asked women to keep food diaries. Through this we’ve gained an important understanding of how women in prison experience food. We hope these findings will help bring changes for the better through the policy and practice recommendations we’ve put forwards.

Why we did the project

The purpose of the Doing Porridge project is to understand and explore women’s perceptions, experiences, and feelings about food in prison.

Our aims were to:

Explore the relationship between food and social identities such as gender, social class, ethnicity, religion, and nationality.

Understand the different places where food is eaten in women’s prisons.

Look at how far women have opportunities to make decisions in their food choices and practices.

Examine the ways in which food is used as ‘illicit currency’.

Assess how much food is a point of discontent and dissent in prison.

To make policy and practice recommendations to improve food practices in the female estate.

Recognising each person’s differences

By talking to women about the different things that help to form their identity – like race, religion, age − we were able to see how these affected their experiences around food and how they might also lead to people being treated differently or unequally. For example, some women discussed how being a mum, along with their own cultural identity, meant that food was a part of their and their families social world. It was more than just eating and was a role they took responsibility for, this then shaped their relationship with food in prison. Others talked about how they have access to money and can afford items on the canteen menu and because of this their diet looks different to people who can’t afford things.

What we found

Food used as social control in prison

We found that food was often seen as a way to control people in prison with many

women seeing the quality of food as part of their punishment. With little choice about when or what to eat, due to tight food budgets in prisons. There were further conversations about portion sizes as well as food being fit for people to eat (or not).

A lack of cultural awareness

Women shared examples about the lack of cultural awareness from staff in as far as including different types of meals that reflect the cultural backgrounds of the wider prison population. They shared concerns that menus considered culturally diverse were tokenistic, inconsistent, and only used for certain celebratory months, like Black History Month.

Cultural awareness and taking back control

Women also shared examples of taking back control in what they prepare and eat; coming up with creative ways of cooking − cooking together with others. Cooking in their cells was an opportunity to embrace religious/cultural needs. Many women also spoke about their identities by reflecting on memories before being in prison, which gave an understanding of the value and absence of food for them, and their attitudes towards food when they entered prison.

‘There were conversations about the relationship between food and mental health, with women who had faced traumatic experiences prior to prison finding these had affected how they felt about food when inside.’

Food inequalities before and in prison

We found that food inequalities contributed to the experiences of women both before and during their time in prison. Many women spoke about food inequalities in affordability, costs, and access to ‘quality food’ and found that the same inequalities affecting them in prison had affected them outside of prison.

Needing to maintain a healthy lifestyle

Many women shared feelings about needing to be healthier or to maintain a healthy lifestyle in prison. There were conversations about the relationship between food and mental health, with women who had faced traumatic experiences prior to prison finding these had affected how they felt about food when inside.

One woman said, ‘ Cos of my mental health and the abuse that I went through with an ex-partner, I’ll only eat food that I’ve cooked myself or watched it being cooked cos my ex-partner used to spike my food and drinks with drugs and then he’d get me addicted…’

Some women spoke about issues around anorexia and bulimia, and some about having been victims of domestic abuse, which led to worries about the prison tampering with their food.

How our findings can help women in prison

We’re currently developing a toolkit for prison staff, which will share our findings and main recommendations.

We’re working in partnership with Food Behind Bars so our findings can support the development of a food education programme led by them.

We’ve shared our findings with the governors meeting and have created resources that we can show to influence policies on budgets in prison.

We’ve created a short animation that summarises our findings which we’ve shared with a range of charities and organisations. Food in Prison - University of Surrey on Vimeo https://vimeo.com/893541558.

We’re aware change can be slow; however, this research project has been an important conversation starter for many people.

Getting to know Laurie Buckton

Words: Jo Halford

We sat down with Laurie Buckton the Strategic Lead for Safer Custody across the female estate who told us about her job, the work the Safer Custody team is doing to support women in prison, and how you can access their support.

Can you tell us a bit about yourself and how you came to be doing what you do today?

I’ve been in the prison service for nearly 18 years. I’ve worked with women my whole career and that’s where my passion lies. I started at HMP Foston Hall as a prison officer. I went through the ranks at Foston and when I left in October 2020, I was the Head of Safety. I then moved into the

Prison Group Directorate (PGD) team. I was originally the Equalities Lead, which gave me a bigger picture of the prison service as I just had Foston Hall as my view point. Then the Group Safety Lead role came and I took over as Safety Lead. I’ve been around safety for a lot of my career, it’s very important within women’s prisons. Safety is where my heart is at. I love my job.

What does your day-to-day work/job entail?

I lead on all things safety within women’s prisons, so that’s violence, self-harm, use of force, segregation, making sure processes are done to a really good standard. Listening to women in prison is also a major part of my job as I can say well I think that would be good for women but actually I’m not living it, and the managers in the prisons aren’t, but the women are and they can give us a really good insight into what would make them feel safer and for prisons to be safer.

I’m lucky to have a team. I’ve got two deputy safety leads and a group safety analyst. We regularly visit all the women’s prisons. We help to support the safety teams in the prisons to make sure the right processes are in place and they’re doing what they should be doing. We have lots of forums with women in prison and we also report to the PGD on how prisons are performing safety wise. Can you talk about Safer Custody teams and how women in prison can access them?

Every prison has a Safer Custody team. The make-up of these differs because all prisons are different, for example some prisons need a bigger team. Many teams have peer mentors who work with them;

they are a really good avenue of support for women. Safer Custody teams can offer distraction activities; distraction packs for women who are struggling, like when they’re locked in their rooms. And for those women who are at risk of self-harm or suicide, or are in crisis in any way, Safer Custody teams can help coordinate support using all of the support available in the prison, bringing them together to help a woman through that particular crisis.

Who can women go to as a first point of contact?

Some of our prisons have safer custody mentors who have been trained locally, and they’re a really good avenue through which to get advice or support, but any wing officer or prison staff will be able to make sure the Safer Custody team knows you want to speak to them.

There are huge issues with mental health and self-harm in women’s prisons, can you tell us more about this and why you think this is?

It is a huge issue for us, but I think it’s important to say that it isn’t just a prison issue, it’s an issue that’s in the community as well as custody. Many of our women come into custody with mental health issues and use self-harm in the community as a survival strategy for many different reasons. Many are trauma survivors and

‘We try to understand why individual women are self-harming, what is the trigger for you, what is happening that has made you feel your only option is to hurt yourself.’

self-harm helps them survive; this can then continue into custody. We have a lot of support available for those women. We try to understand why individual women are self-harming; what is the trigger for you, what is happening that’s made you feel your only option is to hurt yourself. There’s a huge range of support that women can access in mental health teams, substance misuse, chaplaincy, psychology teams, and many more within each prison. They wrap around a woman to help her through the crisis.

What advice would you give to women in prison to support their mental health?

The main thing I would say is ask for help. Speak to people whoever that might be. It might be the officer on your wing, it might be another woman, one of the listeners, one of the peers, just a friend of yours − reach out if you can, it’s really important. Don’t suffer in silence because there’s so much support available. I would also say, embrace the support and opportunities available in prison. Try to make the most of your time with us, there’s lots of opportunities. There’s lots of training, qualifications, different interventions you can take part in. I genuinely believe these can make a difference. Also in terms of reaching out, families can contact prisons, so if you feel there’s absolutely no one in prison you can talk to, talk to your family, we will listen to them. They can pass on any concerns on your behalf.

When might free-flow be coming back in?

Free-flow is a decision for each individual governor of each prison. Restrictions on movement in some of our prisons have gone back to pre-Covid, but there is a balance to be had. Some women told us they felt safer having that extra support or officer when moving through the prisons.

We appreciate that’s not everybody, so I think it’s for individual prisons to understand what that balance is for the women they’ve got.

Have you seen a deterioration of women’s mental health in prisons because of Covid or since Covid?

I think we’re seeing more women coming into prison with mental health issues, whether this is linked to Covid I’m not sure. Lockdown was a tough time for all our women, and prisons did a lot to make sure women felt safe and were safe. Extra pin credit was given, extra distractions packs were given out. But having said that, it must have been an awful time to have been in prison. Thankfully that’s all behind us now but we continue to take good bits from Covid, not from the lock down but from what we’ve learnt.

What further things do you think need to be done for the mental wellbeing of women in prison?

We’re constantly working to do more for the wellbeing of our women. There’s lots of work taking place around the regime and making sure it’s as purposeful and rich as it can be because we know that purposeful activity or gaining qualifications can help make changes later on. We also understand how important a community feel is in women’s prisons. We’re seeing more and more prisons restarting things like staff and prisoner rounders and netball matches. Things that bring the staff and women together really helps. For me staff and prisoner relationships are absolutely vital within women’s prisons. There’s also therapy dogs coming into our prisons. There’s lots we’re doing to try to improve the wellbeing of our women. It’s a constant goal of ours to make it better and better.

ALL YO

We received some really great creative pieces drawing on your own experiences and reflections for us to share in this edition. Here are some of the best poems and artworks you sent in.

From now on

Words: Stacey

Star Letter

From now on I want people to listen, To listen to the voices of us in Prison, You see we’re not just part of a broken system, Where justice is served and people dismiss us. We are wives, mothers, brothers and sisters, Where life has unfortunately turned and we’ve blistered, Blistered in a way where some of us have popped, Popped into a life of crime where eventually it has been stopped. But we still have our dreams, our hopes and aspirations, We’ve all got different stories and we’re all here hoping, That our lives aren’t defined from this moment in time, And we shouldn’t carry the burden of being labelled for our crime. So from now on I do hope people will listen and encourage Our voices to be heard in prison.

HMP Foston Hall Girls: Artwork by Serena

OURS

Motherhood

Words: Miss Saffron

Being a mother it fills me with pride, Although it’s not always an easy ride, From the very first moment I saw them you see, My heart and soul it shone with glee, I wanted to give the very best of me.

Nobody talks about the bad days, You’re tired, drained; your heads in a daze, You really don’t know what to do, Don’t feel as though you’ll make it through, Just hold on; it’s called the baby blues.

From their first step; to first word, My God it’s quite absurd, Just how much they will grow, How you were once in my belly I’ll never know, It’s going too fast, please make it slow.

From your first day at school, To be now using a tool, Soon you’ll be leaving home, I really don’t mean to moan, I just can’t believe you’re nearly grown.

I will never forget, The very first time we met, It doesn’t matter just how big you are, Me always your mother and you my shining star, Whether you find yourself close or afar.

Although I don’t always get it right, Sometimes it really is quite a fight, You’ll always be my baby you see, Only when you have your own bundle of glee, Will you realise it was you who saved me.

Inside

Words: Nadia

Clink, clink goes the officer keys, At first it brought me to my knees, Thoughts of out there playing on my mind, Some form of peace was hard to find. Thinking of my family with tears in my eyes, Staring at the walls, can’t even see the sky, Heart pounding when I think of what’s ahead, Mind whirring when I think of what’s been said. Wondering how long I’ll be here for, Maybe just a year, maybe more, Knowing it’s right, what I did was wrong, Still praying it won’t be for too long. Smiles on my face hiding sadness inside, Moving each day when I want to hide, Then the routine set in, and I got into my stride, Learned a new way, rolling with the tide. The smiles and laughter became more real, Little joys I allowed myself to feel, Found a new norm, got used to this, Sadness is there, but also some bliss. You find a way to face each day, Coping methods are here to stay, Pick myself up, dust myself down, Learn a new way to erase that frown, Find a peace inside of me, Until the day I walk free.

Illustration: Camille

I know son

Words: Lisa

I know a smile I’d love to see, A hand I’d love to touch.

I know a voice I’d love to hear, And a face I love so much. I’ve never asked for miracles, But today one would do. That’s to see my door swing open, And for you to walk on through. I’d wrap my arms around you, And kiss your smiling face. Then the pieces of my broken heart, Would fall back into place.

Short sentences destroy women’s lives: it’s time for change

Words: Lucy Russell

Lucy Russell, Head of Policy and Public Affairs at Women

in Prison, tells us about a new Bill* going through parliament with the proposal to reduce the number of people being given short sentences and sent to prison.

At Women in Prison, we know short sentences can destroy a woman’s life and often those of their children and families. Most women are sent to prison for just a few months for non-violent offences, and yet in that time they could lose their children, their homes, their jobs, and get into increasing debt and poor mental health. Whatever the length of time spent, prison can be a harmful and distressing experience.

What’s worse is women are sometimes sent to prison before they’re sentenced − put on remand. Of particular concern is the higher number of black, racially minoritised and migrant women who find this happens to them. Some women on remand don’t go on to get a prison sentence when sentenced but the damage to their lives has already been done.

Changes to short sentencing?

A new Bill is currently going through parliament which has some interesting ideas for change. The Bill has largely been put together by the current government to

reduce the prison population − prison numbers are going up so fast there isn’t space for everyone in prison.

The Bill suggests that the amount of short sentences being given out should be reduced by those sentencing and they should instead go for suspended sentences – sentences where you serve your time in the community, generally following a set of rules or doing unpaid work. This change could be HUGE for women. While women would still be criminalised, which creates barriers for things like employment, it’s an improvement on the current situation.

If this goes ahead and those making sentencing decisions dramatically reduce the number of women going to prison for short sentences, hundreds and maybe even thousands of women will be given sentences in their community instead of prison. This would mean they could care for their children and get help from community services for things like mental health, substance misuse, and abusive relationships.

Will these changes work?

This is the big question! And the answer is maybe. The women’s prison population is continuing to rise, and there’s a clear motivation to make a change and stop this worrying increase. A major problem is that some people believe prison is the right ‘solution’ when you’ve been found guilty of committing an offence. So there’s a risk those deciding on sentences might think, ‘So I can’t give out a sentence of 12 months or less? I’ll give out longer sentences instead!’ This is called up-tariffing.

A nother problem is sometimes those sentencing don’t know about the alternatives available in their local area. Or they don’t believe those options are

appropriate to the offence.

To make these changes work, probation services and Women’s Centres, like those provided by Women in Prison, will need funding to be able to support the increased number of women on suspended sentences. Our staff are speaking to politicians and our partners about this Bill and pointing out how we can make a positive change in the system. If these changes are going to work, they will need investment. But these things are possible, meaning that real concrete change that could help women is possible.

*A Bill is a plan/suggestion for a new law, or a plan/suggestion to change an existing law, which is presented to Parliament for debate.

‘The Bill suggests the amount of short sentences given out should be reduced and replaced by suspended sentences.’

The National Women’s Prisons Health and Social Care Review

Source: Health and Justice NHS England IIlustration: Chi

In 2021, NHS England began work with HM Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS), supported by Association of Directors of Adult Social Services (ADASS), alongside women with lived experience of prison, to review health and social care outcomes for women in prison and on their release. Here are the review findings and recommendations.

Areport with the findings and recommendations of this review was published in November 2023. Importantly, a lot of the recommendations have been accepted by NHS England and HMPPS and a budget has been put in place to deliver on these.

Women with lived experience were involved at every stage of the review, with over 2,250 responses received from women in prison. The review also heard from those who provide care and support to women in prison.

The review findings

The report found that women in prison have disproportionately higher levels of health and social care needs than men in prison, and then women in the community. High numbers of women in prison experience poor physical and mental health and many are living with trauma.

Findings from the review further showed the vulnerability and adverse life experiences of many women in prison. The

separation mothers experience from their children was felt strongly and highlighted, and also the number of women with poor mental health still being sent to prison.

A great deal has been learnt from the review, with women in prison speaking openly about their experiences and reflections on how services might be improved. The way in which health and social care services are delivered is not always gender or trauma informed, reflective of protected characteristics or consistent across the women’s prison estate. Too often, women in prison must access available services rather than services that meet their individual needs. However, the review noted many examples of good practice from dedicated staff that make a positive difference to the lives of women in their care.

Review recommendations

The following eight recommendations were made and have been accepted by NHS England and HMPPS.

Health and social care services for women in prison should be underpinned by an approach that is gender specific, gender compliant, considerate of protected characteristics, personalised, accessible, equitable, and consistent between all women’s prisons. Fabric improvements across the women’s estate should be made, as needed.

Women who require support with their mental health should be offered timely, equitable access to the most appropriate gender specific treatment interventions and environment. Access to evidence based talking therapies for trauma should be increased, and consistent pathways of care for survivors of domestic abuse and sexual violence ensured.

The national substance misuse service specification should be refreshed to meet the specific needs of women across the care pathway.

Emotional and practical support should be readily available and accessible to all women upon reception into, and during, their early days in prison. Mothers who are separated from their children, pregnant women and young women moving from the children and young people secure estate may require particular support.

A co-produced gender specific Health and Social Care Needs Assessment, performance and outcomes framework should be developed, and data collection of health inequalities enhanced.

Improvements are needed in medicines management and communication with women about their health and social care. Reasonable adjustments should be made for women who are neurodiverse, and information should be accessible for women whose first language is not English.

Improvements in pregnancy and perinatal care, and social care should continue, including support for women who have been separated from their children.

Release planning for all women in prison should be integrated across health, social care, prison and probation services. Continuity of support on release, including access to RECONNECT services should be provided in line with women’s release plans.

The publication of the review marked the creation of a Women’s Health, Social Care and Justice Partnership Board, which will oversee a three-year programme of work led by NHS England’s national health and justice team, to respond to the eight strategic recommendations. Women with lived experience will continue to be part of this work. £21m in health funding has been set aside for this work.

The impor tance of checking your chest

Words: CoppaFeel! IIlustration: CoppaFeel! CoppaFeel! are the UK’s only youth focused breast cancer awareness charity. The charity was set up in 2009 by twin sisters Kris and Maren Hallenga after Kris was diagnosed with stage four breast cancer when she was just 23-years-old. Breast cancer can affect anyone and checking your chest could save your life. Here CoppaFeel! share more information about breast cancer and how you can check your chest.

The word ‘chest’ is inclusive of all bodies and genders. When we need to be clinically accurate we use the word ‘breast’. You might prefer to call your chest something else, and that’s ok!

If breast cancer is diagnosed early, it can be successfully treated.

Here’s some information from us about:

Breast cancer

The signs and symptoms of breast cancer

How to check your chest

Natural chest changes.

What is breast cancer?

Cancer is a condition that causes cells in the body to grow out of control. These cells form growths called tumours.

Breast cancer is cancer that forms in breast tissue. Breast tissue is not only in your breasts. It goes all the way up to your collarbone and under your armpit. Everyone has breast tissue – people of all ages, races and genders.

Some breast cancer facts:

In the UK, 1 in 7 women will be diagnosed with breast cancer in their lifetime.

Around 55,000 women and around 400 men are diagnosed with breast cancer every year in the UK.

Around 2,400 women aged 39 and under are diagnosed with breast cancer every year in the UK.

Source: Breast Cancer Now

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF BREAST CANCER

These signs may look different on your skin tone or your body. It’s really important to know what’s normal for you. Remember to look AND feel when checking your chest.

Signs and symptoms of breast cancer may include:

Skin changes such as puckering or dimpling.

Unusual lump or swelling in your armpit, or around your collarbone.

Unusual lumps and thickening.

Liquid coming from your nipple.

A sudden, unusual change in size or shape.

Nipple is pulled inwards or changes direction.

A rash or crusting on or around your nipple.

Constant, unusual pain in your breast or pec, or armpit.

How to check your chest

Check your upper chest and armpits as well. These areas can also be affected by breast cancer.

Remember to check your nipples. Use any method you are comfortable with. This may be lying down in bed, standing in front of the mirror or in the shower.

Look AND feel every time you check.

Get into the habit of checking your chest every month. If you get to know how your chest looks and feels normally, it will be

‘Get into the habit of checking your chest every month. If you get to know how your chest looks and feels normally, it will be easier to notice any unusual changes.’

easier to notice any unusual changes.

If in doubt get it checked out.

NATURAL CHEST CHANGES

Hormones

Our bodies are always changing. If you have periods, you may notice natural changes to your chest that are linked to the hormone changes during your monthly cycle. It is normal for your breasts to feel tender, sore or swollen around the time of your period. If you are concerned about any changes, speak to a healthcare professional.

Appearance

Chests come in all shapes and sizes. The size of your chest does not affect your risk of breast cancer. You may have different sized breasts, nipples that point in different directions or nipples with hair around them. If they have always been that way and it is normal for you, then you don’t need to worry.

Lumps

Some lumps are perfectly normal, but if you get a new lump or an old lump comes back, speak to a healthcare professional. If you get to know how your chest feels normally, it will be easier to notice any unusual changes.

Remember:

Get to know your normal and talk to a healthcare professional if you have any concerns.

For more information: Visit our website coppafeel.org

Promoting health and wellbeing: the vagus nerve

Words: Toni Hannaway Illustration: PPaint

A qualified psychotherapist, hypnotherapist and energy coach, Toni Hannaway shares information on our all-important vagus nerve, which connects every organ to the brain. She also includes a short exercise you can do to stimulate your own vagus nerve to help bring relaxation and better mental and physical wellbeing.

The word ‘vagus’ comes from the latin word ‘vaga’ meaning ‘wanderer’, and the vagus nerve does just that throughout the human body. As the longest cranial nerve connecting every organ to the brain, it reinforces the mind/body connection and performs a role in promoting health and wellbeing.

Each of us possess this gem of a nerve. It forms part of the parasympathetic branch of the automatic nervous system, the other branch being the sympathetic which triggers our ‘fight or flight’, and stressful states which can lead to poor health if regularly overstimulated and you’re in a constant state of anxiety and stress.

Known as ‘The Ruler of Relaxation’ the vagus nerve not only collects information including feelings and sensations from the body, sending them to the brain for interpretation, but also helps to correct any imbalances by calming and relaxing us.

Some other functions the vagus nerves does include the emotional gut/ brain connection − the ‘gut feeling’ is a real phenomenon. It instructs the lungs to breathe and therefore slows/regulates the heartbeat. It helps to control blood glucose balance in the liver and pancreas and helps to release bile in the gallbladder. It promotes general kidney function and lowering of blood

pressure and eases inflammation in the spleen as well as in other organs. It also helps to control fertility and orgasm in women, influences mood, controls anxiety and depression, and helps with memory. Amongst many other functions.

Signs of poor vagus nerve functioning, known as vagal tone:

l Heart palpitations

l Insomnia

l Chronic fatigue

l Dizziness/fainting

l Brain fog

l Inability to relax

l Allergies

l Digestive problems

Stimulating the vagus nerve

The C1 AND C2 alignment exercise

Developed by Stanley Rosenberg, a chiropractor, to relieve pressure on the vertebral artery and improve the functioning of the the vagus nerve (vagal tone).

l Lie flat on your back (place a cushion under knees or bend them if you have a back problem).

l Interlace the fingers of your hands and place them under your head and neck like a pillow.

l Keep your head still with your eyes open or closed, look to the right without moving your head.

l Keep looking to the right for about 30/60 seconds. You may yawn, swallow or sigh. signalling a shift in vagal tone.

l Then return your eyes to centre.

l Look to the left without moving your head and stay looking to left for 30/60 seconds until you yawn, swallow or sigh. Repeat this exercise as often as required on a regular basis.

Bluebird Ser vice supporting women with personality disorder

Words: Katie Fraser, Tina and Lauren

Illustration: CWB

Read about Bluebird Service along with an interview between project service user, Tina, and project advocacy worker, Lauryn.

Women in Prison previously ran Bluebird Services, funded by NHS England, and it is now run by the organisation Together. Bluebird Service works in partnership with the London Pathway Project, London Probation, and the prison service, to support social inclusion and help women with personality disorder to attain and maintain an improved quality of life and reduce the risk of reoffending, relapse and recall.

The service starts work with women while they’re in prison, and then on release it provides intensive community support focusing on positive progress in things like housing, training, education and employment, health and wellbeing.

To access this support women need to be returning to a London Probation team and either be on the Offender Personality Disorder Pathway (OPDP)* or have a criteria where they could be screened into the pathway.

Tea and a chat about Bluebird Services

Tina, a current service user, and Lauryn, an advocate working in the service, sat down for tea and cake to chat about Bluebird Service.

Tina: Why did you choose to come and work in the Bluebird Service?

Lauryn: I had finished my studies at university and was really interested in working in the field of personality disorders. When this role was advertised and I saw that it was focused on exactly that and was working with women, I felt it could be the perfect role for me.

Lauryn: How do you find the support of our service?

Tina: It’s one of the best services I’ve taken part in, my advocates have been proactive and consistent and just help me with everything. I’ve loads of professionals in my life and you, Bluebird Services, pull all my services together. I feel comfy with you and the other advocates and that allows me to open up.

Lauryn: What makes our relationship different to those you have with other professionals?

Tina: You’re just constantly there and you’re my first port of call. You’re always asking questions on my behalf and not just ticking boxes. You call my doctors and liaise with housing and probation and really sort me out. I feel like some of the other services are lovely, but I feel like other professionals just tick boxes with me. I don’t feel that with Bluebird. I feel like you’re my voice when I find it hard to say what I need.

‘It’s one of the best services I’ve taken part in, my advocates have been proactive and consistent and just help me with everything.’

‘You’ve said to me that going to prison saved your life, but if you’d got the help you needed, when you needed it, you may not have ended up in prison.’

Tina: What are the best and worst things about your job? I know I try and hug you all the time and you’re not keen on that!

Lauren: Haha! The hugging thing isn’t so bad as it reminds us both about boundaries. I really like the fact that the service is flexible. Between us, we can choose the best approach for the support you want. I’m not telling you what to do, we’re deciding together.

Tina: Yeah, I do feel like I’m listened to. I feel like you bring everyone together who is involved in different parts of my life. It’s like having a team looking out for you.

Lauren: I don’t know if there is a ‘worst’ thing about the job. One thing that can be challenging is meeting unrealistic expectations of other professionals. Sometimes they expect us to be doing things that just aren’t part of my role.

Lauren: Is there anything you feel would improve the service and our interactions during our sessions?

Tina: Sometimes with other services, there’s no continuity and I end up having to tell loads of different people the same thing again and again and that gets right on my nerves. I can’t think of improvements to the Bluebird Service, I see you on a bi-weekly and most of the time weekly basis. You’re easy to reach and I can reach out to you about anything.

You also reach out to me as well.

Tina: You say you love your job but is there anything about the service that you would change?

Lauren: It would be great if the contract allowed us to work with young girls. If we could do early intervention work with young women and girls, we might be able to stop them getting involved in the criminal justice system. You’ve said to me that going to prison saved your life, but if you’d got the help you needed, when you needed it, you may not have ended up in prison.

Tina: You know all about me, but how do you manage your work/life balance?

Lauren: I make sure I have a good schedule in place of things to do so that I can switch off when I’m not at work. One example is I go swimming every Friday at 6 o’clock. I started going in winter because I thought if I could make myself go when it’s cold and dark, I would probably carry on going when the weather got better and I am still doing it now, so it worked!

*The OPDP commissions treatment and support services nationally for people with ‘personality disorder’, whose complex mental health problems are linked to their offending. To be referred to Bluebird Service speak to your probation practitioner or resettlement lead person.

Z K K E E W O I I K S B Z

ZN FE VV EE FN

XO NF CP HBGY

EV YA JS RH QI

FX YTTK QO CA

RACX ET GR EE

VO LA U IEI MH

EK CL FX XO PW

CL AE EZ TN IT

KB LR OI JM AE

ML CB OQ AS CV

FY AN ED MH WZ

LB ST QI D SJS

TV NN MI ND PI

How to play? Fill in the grid so that every row, every column and every 3x3 box contains the numbers 1 to 9, without repeating the number.

3 4 7 8 1 4

LEGAL & GENERAL ADVICE

Prison Reform Trust Advice and Information Service: 0808 802 0060

Monday 3pm–5pm Wednesday and Thursday 10:30am–12:30pm

Prisoners’ Advice Service (PAS):

PO Box 46199, London, EC1M 4XA

0207 253 3323

Open Monday, Wednesday and Friday 10am–12:30pm and 2pm–4:30pm, Tuesday evenings 4:30pm–7pm

Rights of Women

l Family law helpline

020 7251 6577

Open Tuesday–Thursday 7pm–9pm and Friday 12–2pm (excluding Bank Holidays).

l Criminal law helpline 020 7251 8887

Open Tuesdays 2pm–4pm and 7pm–9pm, Thursday 2pm–4pm and Friday 10am–12pm

l Immigration and asylum law helpline 020 7490 7689

Monday 10am–1pm and 2pm–5pm, Thursday 10am–1pm and 2pm–5pm

HARMFUL SUBSTANCE USE SUPPORT

Frank Helpline: 0300 123 6600

Open 24 hours, 7 days a week.

Action on Addiction

Helpline: 0300 330 0659

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE

National Domestic Abuse Helpline: 0808 2000 247

Open 24 hours.

LGBTQ+

Bent Bars

A letter writing project for LGBTQ+ and gender non-conforming people in prison.

Bent Bars Project, PO Box 66754, London, WC1A 9BF

Books Beyond Bars Connecting LGBTQIA+ people in prison with books and educational resources.

Books Beyond Bars, PO Box 5554, Manchester, M61 0SQ

HOUSING

Shelter Helpline:

0808 800 4444

Open 8am–8pm on weekdays and 9am–5pm on weekends.

NACRO information and advice line:

0300 123 1999

FAMILY SUPPORT

National Prisoners’ Families Helpline: 0808 808 2003

Open Monday-Friday 9am–8pm and on Saturday and Sunday 10am–3pm (excluding Bank Holidays).

OTHER Cruse Bereavement Care 0808 808 1677

Open Monday–Friday 9:30am–5pm, Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday 9:30am–8pm and weekends 10am–2pm.

Samaritans

116 123

Disclaimer: please be aware that some helplines will be operating under new opening hours due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Women in Prison (WIP) Consent Form

We love to receive artwork, poetry, stories, articles, letters, knitting patterns, recipes, craft ideas etc., for publication in the magazine from women affected by the criminal justice system in prison or the community. Please complete and tear out this form to send along with your piece so that we know you are happy for us to publish your work and what name you would like to use.

Please note that we are unable to return any of the written pieces or artwork that you send to us for publication.

Thank you for your contribution! All the best, the Women in Prison Team.

Please use CAPITAL letters to complete

First Name

Prison or Women Centre (if applicable)

Any Contact Details (email, address, phone)

Title of your piece (If relevant)

Surname

Prison No. (if applicable)

Basic description (e.g. a letter in response to... or a poem or an article on...)

I give permission for my work to be used by Beauty out of Ashes (as outlined in the competition on page 59)

I give permission for my work to be used by Women in Prison (PLEASE TICK):

WIP’s magazine (Still I Rise)

WIP’s online platforms (our website, www.womeninprison.org.uk, and social media, including Twitter, Instagram, Facebook and LinkedIn) Yes n No n

WIP’s Publications & Promotional Materials (i.e. reports, leaflets, briefings) Yes n No n