Whether you, or the people you know and care about, are recovering from trauma, mental health issues or addictions, finding the right kind of support is key to getting better and living life to its full potential.

For some people, this support might take the form of talking therapies, while for others mindfulness might help, and for most of us strong supportive networks are really important. Research has found that a positive and encouraging support network makes recovery both easier and longer lasting.

We would love to hear about what support means to you. We’ve created a competition on the theme of support for this edition so that you can share your thoughts on support with others – we hope you will take part.

• Feel free to give your own interpretation of what support means.

• If it’s a story, essay, interview or article (fiction or non-fiction) please write 500 words or less. When handwritten, this is between 1½ and 2 pages of A4.

• An entry can also be a poem, drawing, painting or a collage.

• Please include a completed consent form (see page 65) with your entry and send it to Freepost – WOMEN IN PRISON (in capitals). Without the consent form we are unable to include your submission in the magazine.

One entry will be selected as a "Star Letter" with the writer receiving £20 (only entries that include the consent form on page 65 can be considered for "Star Letter").

Women in Prison (WIP) is a national charity founded by a former prisoner, Chris Tchaikovsky, in 1983. Today, we provide support and advice in prisons and in the community through hubs and women’s centres (the Beth Centre in London, WomenMATTA in Manchester and in partnership with the Women’s Support Centre in Woking, Surrey).

WIP campaigns to reduce the number of women in prison and for significant investment in communitybased support services for women so they can address issues such as trauma, mental ill-health, harmful substance use, domestic violence, debt and homelessness. These factors are often the reason why women come into contact with the criminal justice system in the first place.

WIP's services are by and for women. The support available varies from prison to prison and depends on where a woman lives in the community. If WIP is unable to help because of a constraint on its resources, it endeavours to direct women to other charities and organisations that can. WIP believes that a properly funded network of women's centres that provide holistic support is the most effective and just way to reduce the numbers of women coming before the courts and re-offending.

WIP’s services include...

• Visits in some women’s prisons

• Targeted ‘through the gate’ support for women about to be released from prison

• Support for women in the community via hubs for services and women’s centres in London, Surrey and Manchester

• Still I Rise A magazine written by and for women affected by the criminal justice system with magazine editorial groups in some women’s prisons

Please contact Women in Prison at the FREEPOST address below. Please include a completed consent form with your query; turn to page 65 for more details.

Email us on: info@wipuk.org

Women in Prison

2ND FLOOR, ELMFIELD HOUSE

5 STOCKWELL MEWS LONDON SW9 9GX

Please know that whatever you are going through, a Samaritan will face it with you, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Call the Samaritans for free on 116 123.

CONFIDENTIAL

Our service is confidential. Any information given by a service user to Women in Prison will not be shared with anyone else without the woman’s permission, unless required by law.

We are a group of women currently living on Bruce House – an incentivised substance-free living unit at HMP Styal in Cheshire. We were excited to be given the opportunity to work on this edition of Still I Rise. When asked to choose a theme it seemed like a no brainer to choose recovery and support as we all have our own experiences with addiction. And as everyone else in prison – not just us – is on their own journey towards recovery and resettlement, we thought it would be a theme that might interest many.

No matter where you are in your journey, information and support from other women experiencing similar issues is vital, and goes a long way in helping you through your journey until you are out the other side. In our unit, we all support

one another and offer advice.

We can all learn from each other’s stories, and you can read some of our stories inside the magazine. We also have an interview with Dame Carol Black who led the independent drug inquiry, which resulted in a significant increase in funding for drug-related services, the story of Twitter’s infamous Secret Drug Addict, and research findings on the negative health impact of prisons across the world, along with lots, lots more.

Some of the women who have contributed and worked on this edition are no longer on Bruce House, some have been transferred internally, some to other prisons, and others have been released, but it really was a team effort by all of us.

We hope you enjoy this magazine.

The HMP Styal editorial group (All women, past and present, who have been residents on Bruce House)

Project Manager: Kate Fraser

Art direction & production:

Henry Obasi & Russell

Moorcroft @PPaint

Production Editor: Jo Halford

The magazine you are reading is free for all women affected by the criminal justice system in the UK.

We send copies to all women’s prisons and you should be able to find the magazine easily. If you can’t, write to tell us. If you are a woman affected by the criminal justice system and would like to be added to our mailing list for free, please contact us at Freepost WOMEN IN PRISON or info@wipuk.org

The publishers, authors and printers cannot accept liability for errors or omissions. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of Women in Prison. Applications should be made directly to Women in Prison. Registered charity number 1118727

We are super excited to have handed over much of this edition of the magazine to an editorial group from HMP Styal’s Bruce House incentivised substance-free living unit, who have worked with us to produce this issue. Here, they introduce their edition of the magazine.

Women’s Centres run by WIP

Women’s Centres where WIP staff are based

WomenMATTA – Manchester

The Beth Centre – Lambeth, London

Women’s Support Centre – Woking, Surrey

Women’s Prisons

HMP Low Newton – near Durham

HMP Askham Grange – near York

HMP New Hall – near Wakefield

HMP Foston Hall – near Derby

HMP Styal – near Manchester

HMP Drake Hall – Eccleshall, Staffordshire

HMP Peterborough

HMP Eastwood Park – near Bristol

HMP Downview - Sutton, Surrey

HMP Send – Ripley, Surrey

HMP Bronzefield – Ashford, Surrey

HMP East Sutton Park – Maidstone, Kent

HMP Cornton Vale – Scotland

“It’s your road, and yours alone, others may walk it with you, but no one can walk it for you.”

Rumi, 13th-century Persian Muslim poet, jurist, theologian, and Sufi mystic

Having worked with the women on Bruce House substance-free living unit at HMP Styal, Katie Fraser, Women in Prison Head of Prisons Partnerships and Participation, went in search of information about how di erent countries approach addiction and recovery. She shares her findings with us.

Working with the women on Bruce House at HMP Styal really got me thinking about addiction and recovery, and how society views and treats those struggling with substance misuse issues. This led to me looking at how other countries differ in their views, and I found that globally the difference is massive.

The USA, for example, only see substance misuse as a criminal issue. They have waged a ‘War on Drugs’ for the past 50 years which has often been criticised as an excuse to declare war on people of colour,

poor Americans, and other marginalised groups. People who are more likely to be imprisoned after arrest than diverted into drug treatment.

In Saudi Arabia, the practice of Wahhabist Islam means that there are no bars or off-licences, and that visitors are forbidden from bringing any kind of drugs into the country. People caught using drugs by the religious police can be sent to jail, flogged in public, and deported. Drug traffickers can be executed.

At the other end of the scale, in 2001 Portugal chose to view substance misuse

and heroin addiction in particular, as a number one public health issue. The government created a task force of doctors, judges and mental and social healthcare workers who came up with an unexpected plan. A plan to decriminalise drug use and create new policies and programmes to treat addicts and prepare them for reintegration into society.They argued, that if addiction is a disease then why arrest sick people? They worked under the assumption that the addiction epidemic was medical in nature and not an issue of criminal justice. To this end, Portuguese citizens caught with drugs were offered therapy instead of jail sentences, which are more costly to taxpayers.

Not everyone agreed with these changes, but five years after the personal possession of drugs was decriminalised in Portugal the effects across the country exceeded their expectations. They found that Illegal drug use by teenagers had

dropped; rates of HIV infection from sharing contaminated needles had dropped; and the number of people seeking treatment for substance misuse had more than doubled.

Switzerland, the Netherlands, Denmark and Germany all offer heroin clinics funded by the government as part of their national health programmes to treat addicts with serious heroin problems. This is in clinics where chronic heroin addicts are given daily injections of heroin as part of a treatment programme aimed at gradually getting them off heroin and reducing their drug use and drug-related crimes.

Working with the women on Bruce House and listening to their stories about how they’ve struggled to access help and support at the right time to help them recover, it has become clear that the £700m pledged by the government as part of their new drugs strategy in 2021 isn’t making its way to those who most need it – or at least not fast enough.

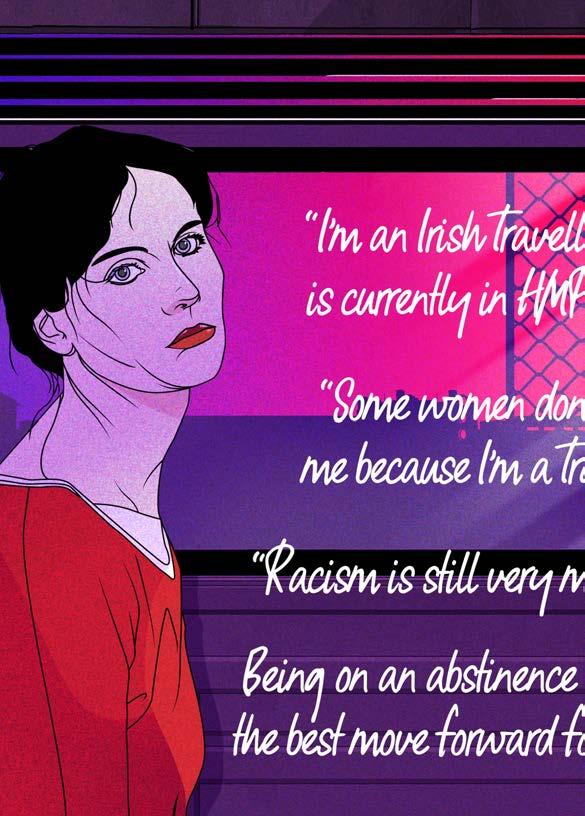

Words: Lee

Illustration: PPaint

Lee is on an incentivised substancefree living unit at HMP Styal, she tells us about her positive experience of living on that unit, and her sometimes not so positive experience of being an Irish Traveller in an English prison.

My name is Lee. I’m an Irish Traveller who is currently in HMP Styal. I’m a recovering heroin addict. I came into jail 11 months ago, and I’m awaiting sentencing for aggravated burglary. I never thought I’d end up in jail again for something that’s going to change my life. I’m 29-year’s old and I’m looking at a long sentence. When I got onto the wing, I couldn’t believe I was back again – we all know that feeling of what I am doing back here.

I began using heroin at the age of 13. Soon after, I started getting into trouble; hanging around with different people and picking up charges. People say you need that light bulb moment to know that it’s time to stop doing drugs, and all the madness that comes with them. I hit my low when I landed back in a police cell and the judge remanded me. Before coming to Styal, I had been using heroin and crack flat out. When I came to the prison reception and saw the nurse, I was really shocked to be told I was 8-stone, when only five months earlier I had been 13-stone.

I put an application in with my Drug and Alcohol Recovery Services (DARS) worker to get onto the incentivised substance-free living (ISFL) unit. Things have really changed for me since moving

into one; usually when I come to jail I take drugs and get into trouble. I’ve been in and out of jail since the age of 14. Since coming to HMP Styal, I’ve decided it’s time to change.

Moving onto the ISFL unit is truly keeping me clean. The officer comes in twice a month to do drugs tests. There are incentives to stay clean, and you don’t want to let the other girls down. Everyone is doing the same; everyone wants to be drug free. I’m on methadone, but I’m going to start coming off it once I’m sentenced.

The women on the unit are a great support, we all look out for each other and want one another to do well, and on bad days we’re there for each other. Nobody wants to be in prison, but I truly believe all prisons should have ISFL units for addicts. I didn’t want to come back to prison but I’m here, and it’s only me that can make the change.

This is my first time in an English prison. I was in prison in Ireland and Northern Ireland previously, which is completely different from here. I thought it would be difficult because I’m from Ireland, but generally people have been nice and showed me what to do. Some women don’t like me because I’m a Traveller. They have fixed ideas about

‘My whole life I’ve had people saying things behind my back. You’d think that in 2023, people would realise how much racism hurts people. It’s not just about being a Traveller, but also being Irish.’

gypsies; they put you into a category of being a liar and a thief. That you’ll rob them, and even put a curse on them. Racism is still very much alive. I had an officer say to me, while putting on my accent, “Do I want to buy any dags”. He was trying to embarrass me in front of the other girls. He used this saying as it’s from the film Snatch, where Brad Pitt plays a Traveller. My whole life I’ve had people saying things behind my back. Calling me things like pikey – a racist slang for the Traveller community. You’d think that in 2023, people would realise how much racism affects and hurts people. It’s not just about being a Traveller, but also

being Irish.

Being a Traveller and on drugs, life has been hard for me. My family are embarrassed about me being an addict, they never thought their little girl would end up on drugs. For them it’s shameful, they expected me to be like the other Traveller women, married with children and living in a nice house or trailer. I’ve been married since I was 15, going on 16, but I have no children. My family are now proud that I’m in the middle of turning it all around. Being on an abstinence wing has done that, this house is the best move forward for an addict.

I’m 29 and it’s time for change.

Words: Sammy

Sammy shares her experience of being in recovery from substance addiction, and how living on an incentivised substance-free living unit she’s working to stay clean.

The road to recovery is a long, bumpy one, and sometimes you can get stuck. I have been in and out of addiction and recovery for 20 years. I’ve gone from being a drug user to becoming a drug and alcohol worker, and then back to being a drug user and dealer again – it’s like being on a roundabout, and taking a different turn every few years.

I currently live in HMP Styal on the incentivised substance-free living (ISFL) unit. I’m giving recovery another go. I won’t lie, it’s not been easy. It still isn’t, but I’m trying. People who know me and my story can get frustrated because they think I should know better, having done courses and completed training as a drug and alcohol worker. During my longest period in recovery – three years – I worked in an alcohol detox centre. But the one

thing about addiction is that it doesn’t discriminate. It doesn’t matter who you are, or what you do, once you’re clean you’re always in recovery and at risk of slipping – you can never be complacent.

Managing triggers is a big challenge for me. When government cutbacks led to the closure of the alcohol detox centre where I worked, I lost my job and had to go back to relying on benefits. That was a major trigger, which resulted in me using again – heavier than before. Eventually my savings ran out and with a huge heroin and crack habit to keep, I started selling drugs to fund my addiction. It seemed like a good idea at the time and recovery was not a word in my vocabulary then.

After I was sentenced to eight years in prison, I decided to try again. I completed my methadone detox and got a place here

in the ISFL unit. But life is no fairy tale and recovery is hard work. I have slipped a few times, but that is part of the journey. With support from the other girls in the ISFL unit who are going through the same thing, it helps–we are all taking it one day at a time.

When you’ve used drugs on a daily basis for years, the idea of recovery and dealing with day-to-day life with a straight head can be scary. You get used to feeling numb, and the thought of not being like that is frightening. But if I can manage it, I’m pretty sure that anyone can.

Don’t beat yourself up if you slip, it doesn’t matter if it’s drugs, alcohol, gambling, or just getting through your sentence – pick yourself up, give your head a wobble and keep going. It can be done!

‘Don’t beat yourself up if you slip, it doesn’t matter if it’s drugs, alcohol, gambling, or just getting through your sentence –pick yourself up, give your head a wobble and keep going.’

Interview questions: Bruce House editorial group

We sat down with Dame Carol Black who led the government-commissioned two part independent review on drugs, and asked her some questions from this magazine’s Bruce House, HMP Styal, editorial group.

Can you tell us a bit about how you came to be doing what you do today?

I come from a large working class family. I’m an only child but both my parents were members of large families. No one in my family had been to grammar school or university before me. My first degree was not in medicine, but I found I had a passion to become a doctor so I came to it later.

I practised as a hospital doctor, then I became the President of the Royal College of Physicians. This got me interested in the wider issues of health, which is how I came

to be the National Director for Health and Work. In this role, I became interested in the subject of work and the problems that keep people out of work – addiction was one of those problems.

In one of my reviews for government, I recommended a national trial of what’s called Individual Placement Support (IPS) as a means of helping people with addiction get back into work. I visited prisons, and I started to get an understanding about addictions and work, and how few people with addictions could

work. I then advised government for several years on health, wealth and wellbeing, before the home secretary asked me to do the review on drugs.

A lot of women end up in prison because of drug addiction and related o ences. How do you think women in these situations should be treated?

No one, and that includes women, are treated well enough. For example, we don’t have good enough services for women, the LGBT community, or ethnic minorities. One of our biggest problems is ensuring that whatever sector you are dealing with, whether it is women, whether it’s young people, is that we have got the right workers in the right place to do the right thing.

Another problem is that we don’t get in early enough to break the cycles that people go through. We have far too many people going to prison when we should be having good diversion/alternatives. Quality treatment with all the support services around, and not just getting people into treatment but also housing; enabling them to train if they need to; enabling them to work if they want to; making sure they are in a recovery community. The work for this to happen can’t be done in one year, but I’m hoping with my report and where we are now that we can start to bring about change.

First of all, I think it’s about what the government

Much drug addiction is based in early years: it’s based in families; in education and keeping people in school and not expelling them. The government needs to provide better joined up services for families in need and beyond that.

It also needs to pay more attention to

prevention. Things like, how do you help young people and therefore young girls stay out of the drug trade, or gangs, which leads to other problems. How do you support drug-dependent women with children, who may be single mums. How do you make it comfortable for them to admit they have a problem and to seek help.

The government can help by making drug addiction a public health problem, reducing the associated stigma. Drug addiction should be treated like diabetes, a chronic condition. If you have insulindependent diabetes, there will be occasions when you are not in good control, and nobody persecutes you, they support you to get back in control. It should be the same with drug addiction. What were the main recommendations from your independent review on drugs that relate to women in prison?

The review didn’t look at the treatment of drug-dependent people in prison. I was only allowed to look at what I could recommend to reduce the number of women going into prison, and what should happen when they go out – often on a Friday with nowhere to live and only a 24-hour supply of medication, with no work, and probably going back to the life they led before.

What I said is that there should be no discharges on a Friday – they are trying to put this in place. That before people leave prison they should have their benefits sorted. They should be in touch with, and know, when they are going to see their treatment provider. As much as can be done beforehand should be, and no one should leave prison without a connection. Some things are beginning to happen, but not fast enough.

I’ve been in prison in Ireland and there are so many more resources to get you

into detox and rehab. Why is the situation in England so di erent?

The problem is that since 2012/13 the local authority public health budget was reduced year-on-year. The resources available for addiction went down, the workforce went down, and therefore the expertise disappeared. In prison in England the resources are provided through the NHS, and I suspect the NHS hasn’t increased the amount of money that’s devoted to treatment in prisons, and therefore the providers have not been able to give a full service. Whilst we are all able to live in an abstinence house in Styal, we know we could be transferred to another prison at any time where we don’t have the same opportunity. What could be done about this?

There has been money signed off following my review recommendations that will be going into providing more drug-free facilities in prison. These won’t be available in every prison, but I would hope they will be available in a lot of them.

What has changed following the recommendations from the independent drug review reports?

What has pleased me the most is the change in attitude everywhere I visit. At last there’s hope, there’s enthusiasm, there’s determination to really try and turn things around. We now have drug partnership boards in every local authority, with a senior

responsible person. I’ve seen much better collaboration. The police working with the DWP, with the mental health provision from the NHS, with the local council etc. There are proper recovery pathways. Recovery communities where the housing money is beginning to be used to get safe housing, and where they’ve got a good IPS programme helping people to get into work. Drug-free wings or houses are happening. We are getting more money for health and justice coordinators – people who are there to ensure that as people take their journey through prison and then out of prison, that there is much better coordination.

Our job now is to get the new strategy to work, and to show the treasury that we are beginning to make a difference. To show them areas of good practice, and what is possible. Because this is a ten year journey, it isn’t going happen in one year. So my job and other people’s is to push as hard as we can to see change, record that change, and use it to get the next years of money.

It is really important to have a go, not to give up, and not to let people push you back. I know it’s tough because the whole system isn’t good enough. It’s never too late to make changes. It’s just getting the right combination of support in at the right time.

‘It’s never too late to make changes. It’s just getting the right combination of support in at the right time.’

The Secret Drug Addict’s popular Twitter account has 400,000 followers. Remaining anonymous, he tweets about addiction, mental health, and social issues, among many other things. Here he shares his personal experiences of addiction, recovery and Twitter.

My background was pretty normal working class stuff. I was obsessed with music, so it was the stereotypical rock and roll stuff, like sex, drugs and music. I always struggled to fit in. I think most teenagers do, but I maybe overthought it more than most; looking to find my place,

my personality, where I fitted. I turned to drugs and that became my personality. I couldn’t stand out for being clever, or good looking, or creative, but I could be that guy.

I went to work in the music industry after I left school at 14, and I did well. I ended up working with bands like

Jamiroquai, Oasis, Primal Scream, the Beautiful South, Texas, and Super Furry Animals. I wasn’t what you’d call enormously successful, but in terms of being a kid I was doing well compared to my peers. I had my own house, and I was earning decent money.

A lot of people talk about not being able to cope with failure, but I struggled with success and the sort of pressure that comes with it – that maintaining and not losing it. I started to do more drugs because they were fun and an escape. At first, I was still managing to get to work and things were okay. But over time it became a problem, missing days at work, messing things up. My mental health began to suffer, and gradually it was all just problems. I couldn’t connect this with my drug use at the time because for a long time drugs had worked for me. I blamed things on the girl I was seeing, my boss, my dad. It was everybody and everything else. I didn’t want to be accountable for my own behaviour, the mistakes I was making.

I lost my job and I went to work for a smaller record company. The money wasn’t as good, and my drug use got worse. When they let me go things unravelled. I drifted out of work and I was stuck with a drug habit and no income. I started selling drugs and getting into trouble with the police.

I’m approaching 16 years of abstinence this June. It can be easy to forget what it was like: the last days, years of my drug use, and how bad my mental health had become. How suicidal and aggressive I became.

In early recovery, I couldn’t sit still. I’d come out of Narcotics Anonymous (NA) meetings and I would see people outside

pubs, drinking, smoking, lads starting their night out having fun, and I’d be walking out of the West End to go home. By 11.30pm, I’d be rocking on the sofa. I found it really claustrophobic being in, and I was very anxious. So I’d go running at midnight for an hour, as fast as I could. I’d do two/three NA meetings a day. I didn’t have a job, or a girlfriend. I was just trying to keep busy, getting through the days. Then after about eight months, things started to get easier.

After about two to three years of being clean, I lost my house. I ended up in a single room in a hostel for 18 months. It felt like I was in a worse place than before, as even throughout my drug using days I’d had a house.

That’s life – you get stu back, and you lose stu

A couple of years into recovery, I met my partner and had kids. I thought I had life beyond my wildest dreams in my early music days, but I realised this was it. I lost my mum in recovery; I lost my house in recovery; and my little brother died from a drug overdose five months ago. You get stuff back and you lose stuff, that’s life. That’s what I didn’t understand those times when I sat in my house with the curtains drawn for months on end, doing drugs, not engaging with life. Then one day you open the front door and you realise that they’ve built something new across the street and a shop has opened at the end of the road. Life goes on, it’s happening whether you choose to engage or not. And that’s the thing, if you want to engage in life, in recovery, you have to take the good and the bad.

There’s an authenticity to my joy now it’s not chemical related. It’s the same with pain, I’m going to feel it, and in a perverse way I kind of like it.

When I first started on Twitter, there wasn’t’ that many other people doing similar stuff. The most famous person I can think of would have been Russell Brand.

I put stuff out that I think has some truth, rather than tweeting things you hear in meetings like, ‘My worst day in recovery is better than my best day using drugs’, because it’s not. I had some great times doing drugs. We need to be honest, and then we can maybe get a better understanding of what the issues are, as individuals, that we can work through. A mate of mine texted the other day jokingly saying that everyone on Twitter’s now in recovery. Recovery influencers are now running parallel with the fitness/wellbeing influencers. I’m not interested in making money out of this, people trust me.

I thinks it’s important to keep a sense of humour in recovery. I tweeted a Frankie Boyle joke a little while ago about, ‘If you do something you love in life, you’ll never work a day in your life, my uncle did heroin’. I thought that was quite funny. I also tweet ironic, inspirational stuff like ‘I’m in charge of my emotions, today I choose to feel anger’. Then just articles, stuff other people are saying. I tweeted an article the

other day about people who work volunteering in harm reduction services to the point of burnout.

Sharing about your life

I sometimes share about my life. I did mention my brother’s death about three or four weeks after. I knew a tweet like that would get engagement, and I know that whenever I tweet stuff that goes viral I feel good because of all the pleasure endorphins going off in my head. Then I felt guilty because I didn’t want to turn his death into content. I felt quite ashamed. I ended up saying about it, and then muting any responses.

I’m secret because I don’t want to be Twitter famous. I don’t want the ‘Secret Drug Addict’ to be my personality. It’s part of who I am, just like my addiction is part of who I am. I jump on Twitter, I do what I do, I put my phone away and I’m not that person anymore.

Finally I want people to see that just because you are in recovery you can still go and do stuff, have a normal life. I got clean at 29, and I thought I was gonna miss stuff. My mate was Djing at a club the other week and I went down and was there until 4am. It’s important to let people who want to get into recovery, or who are in early recovery and don’t’ feel safe going out, know that your life can be whatever you want it to be.

‘If you want to engage in life, in recovery, you have to take the good and the bad. There’s an authenticity to my joy now it’s not chemical related.’

Illustration: PPaint

Lyndsey from HMP Styal shares some guidance on prison slang.

My local prison is HMP Low Newton. All the prison slang in Low Newton I understood. However, I now know that slang changes from jail* to jail (that’s slang for prison to prison).

I’ve lost count of how many words I’ve heard used for a prison officer – Screw**, Kanga, Scubby, XR2.

This magazine gets looked over and words sometimes get changed to what they should be, rather than what we relate them to being. However, as the editorial group for this edition are from Bruce House in HMP Styal, I think it’s important that the women reading it can know a lot of it has been written by women in prison.

I get that for some people it might be your first time in jail, and you might not know what some slang words mean. Don’t’ be scared, just ask someone on your wing. In fact, if you are finding your first time all a bit overwhelming and you don’t know what

to say to people, this could be a really good convo (conversation) starter. Just explain it’s your first time and that there are words you don’t understand. Even ask people if there are any more they can think of that might help you along in your first sentence. Even ask your pad mate if they know of any more. Most prisoners use a lot of slang and that’s why we thought it was important to include this piece in the magazine.

* The slang word jail comes from the French word jaiole (meaning cage)

** The slang word Screw comes from Victorian times, when a prison warden would give a person in prison a pointless task as punishment. One was to crank a handle attached to a large wooden box, the cranking did nothing other than turn a counter. The prisoners had to do 10,000 cranks in eight hours, one every three seconds or so. As an extra punishment the prison warden would tighten the screw to make turning the machine more difficult.

A FEW WORDS TO GET YOU STARTED

C.S.U Seg, block, chockie, slammer

Time/bird/porridge Jail sentence

Oil/cap Vape pen

Jam/jam roll Parole

Lie down Remand

L plates Lifer

Mate/fam/bro/cuz Friend

Aggro bell/riot bell General alarm bell

Webs/wheels/sneaks Trainers (trabs)

Garms/threads Clothes

Film floor/Sky TV Basic

Go behind the door Fight

Keep deeks Look out

Stack/wedge Money

Nicking Adjudication

Twisted Up C &R (Control & Restraint)

Blower/clog Phone

50/plod/bops/bizzies Police

Pad/damper Cell

Scran Food

Sharing food is often a way we show that we care about one another, and a way of providing support. We hope that these recipes from around the world inspire you to celebrate our similarities and differences in the way that we can support one another.

A tasty, popular way of serving chicken, and often a takeaway treat. This recipe for southern fried chicken goes well with rice, fries and/or salad.

Makes approx. 10 portions (half the recipe for less)

Ingredients:

1 kg chicken

2 cups self-raising flour

3 onions

2 peppers

1 egg

2 cups of milk

3 spring onions

Cooking oil

Seasoning:

l For the seasoning, mix all of the ingredients listed below together, make enough to cover the chicken pieces – use quantities according to taste.

Cayenne pepper; cajun spice; chilli; cumin; curry

powder; five spices; garlic; mixed herbs; paprika; parsley; pepper; salt

*If you can’t find all of the ingredients above, you can use what you can find.

Method:

l Place two cups of flour into a bowl with one spoonful of your seasoning spices (mixed together) and stir well.

l Pour your milk into a separate bowl and break the eggs into it. Mix these two together.

l Now, place the chicken into your milk and egg mixture.

l Remove your chicken, one piece at a time, and place it into your flour and spice mix.

l Turn it around until it is fully covered in the mixture, then place it on a plate ready to be cooked.

l Heat your oil in a large pan, have enough to fully cover the chicken pieces.

l Once your oil is hot, put your chicken pieces into the pan and fry until crispy, and a golden brown colour, then place on a plate ready to serve.

l While your chicken is frying, cut your onion and peppers into strips, place some oil and paprika on them, and put them into the oven for five minutes.

l Once cooked, mix the peppers and onions with your cooked chicken and serve.

JinJin’s Chinese spring rolls make a tasty starter/ snack for sharing, or an accompaniment to a main meal.

Makes approx.: 30 spring rolls (half recipe for less)

Ingredients:

1 packet of spring roll sheet pastry (13cm x 13cm)

1 large chicken breast (boiled and shredded into strips)

1 packet of pork mincemeat (16 ounces)

1 bunch of spring onions

1 large packet of beansprouts

2 onions

3-4 medium carrots

Cooking oil

Sesame oil

2 garlic cloves

Soy sauce

Salt and pepper

Method:

Stage 1

l Chop the spring onions and carrots into strips.

l Chop the garlic and onions into small pieces.

l Heat the oil in a large deep pan, or wok, over a high heat and place the chopped spring onions and garlic into the pan and cook for a minute, stirring as they are cooking.

l Add the pork mincemeat and chicken strips and cook until golden brown.

l Once cooked, add the carrots, spring onions and lastly the beansprouts to the pan and cook for a couple of minutes.

l Sprinkle black pepper and salt onto the ingredients, and stir occasionally.

l Add one tablespoon of soy sauce and one tablespoon of sesame oil.

l Remove the pan with the ingredients from the heat, drain any excess sauce/ moisture from the mixture, and leave to cool.

Stage 2

l Remove the spring rolls sheets from the packet.

l Place a sheet on the table in front of you in a diamond shape, with one point facing away from you and the other facing towards you.

l Place a small amount of the cooled ingredients into the middle of the sheet.

l Then, starting with the

bottom end of the diamond (nearest to you) start rolling upwards, when you are half way fold in each end, then continue to roll all the way to the top.

l Tap water under each end at the point where you are sealing the roll, to stick it together.

l Repeat this, to make as many rolls as the ingredients allows.

l Preheat a fryer with cooking oil.

l Deep fry the spring rolls for 10 minutes until golden brown.

l Remove from the fryer and serve hot.

Words: Jenny Thomas and Jo Halford

Photography: Holly Dwyer

The Clink Charity provide an opportunity for women in prison to gain qualifications and experience working in hospitality. Read this article to find out more.

Partnering with HMPPS, The Clink Charity offers the opportunity for people in prison to gain experience and qualifications working in hospitality (restaurants/catering) and horticulture (garden growing and management). It has three training restaurants open to the public for meals in HMP High Down, HMP Brixton and HMP Styal; a bakery at HMP Brixton; two gardens at HMP Send and HMP High Down where some of the food for the restaurants is grown; an events production kitchen at HMP Downview which provides a catering service for

events outside of prison; and 27 prison kitchen projects across England and Wales. All of which provide career building opportunities for people in prison.

Over 200 people in prison a day are trained by the Clink project to gain their Level 2 NVQ in either Food and Beverage Service, Food Preparation, Food Hygiene or Horticulture. Having gained qualifications and workplace skills while in prison, people who graduate from the project are also supported for up to 12-months after their release.

Jenny Thomas who works as the General Manager Trainer at The Clink Restaurant in HMP Styal says of the project:

“The Clink is not only about receiving a fully accredited qualification. We offer a variety of training courses - some of which would cost up to £2,000 if taken outside of prison – but the real value is the support our resettlement team can offer women on their release. The Clink can

assist in securing a recovery home for women with addictions, accommodation, debt management and support employment opportunities. The support is there to get graduates ready for release and then for as long as they need it after, although it typically reduces after a year.

“To get involved in the project you can speak with your OMU, who will liaise with

‘Up to 200 people in prison a day are trained by the Clink project .’

Reducing Reoffending or directly with the Clink team to start the interview process. At HMP Styal, this can either be to start work in The Clink Kitchens or at The Clink Restaurant. To work in the restaurant, you will need to be ROTL eligible as a minimum.In HMP Styal, women on the project work a 40- hour week in the restaurant or within the prison kitchen producing meals.

“We recently had celebrity chef Glynn Purnell (Great British Menu) join us for a masterclass. He spent time with the students in The Clink Restaurant and

taught them how to make one of his signature dishes, duck breast with toffee and cumin carrots. They then had lunch with him and were able to ask questions.

“The best part of my role as an assessor is watching the students grow in confidence and develop their skills. A qualification is how we measure what the student has learnt, but to see a woman arrive with us on day one, who clearly has no confidence or has too much anxiety to look us in the eye, to then be running a shift or producing fine dining food, is something I will never tire of.“

Words: Corinne

Illustration: PPaint

After gaining her enhanced status, Corinne took up the opportunity to cook in the prison kitchens, from there she progressed to working as a chef at The Clink restaurant in HMP Styal. Corrinne shares her positive experience with us.

Ihave been in prison for 17 months. It’s been a bumpy road. When I first came in, I gave staff a lot of attitude. There are different levels of a prisoner. There is standard, which you are when you first come in. From there you can work your way up to enhanced, which gives you more incentives, like earning wages and getting more books out of the library, or ordering perfume from Avon. You can get your enhanced status after three months, but I had to wait longer because of my attitude.

A member of staff who I had a lot of time for gave me my enhancement. After that I decided to take a different approach, and that’s when I started working in the kitchens. I put myself on a cooking NVQ – I have now completed my level 1 and I’m working towards my level 2. When it came up to my tag date, which I was seriously thinking of going for, the staff could see I was doing really well compared to when I came in, so I decided to ask my Offender Management Unit (OMU) worker whether I could work at The Clink restaurant to get more experience.

I thought why not go for it, and I did. The money side was also good to have.

It’s feels amazing that I am now doing what I love, cooking, and in the process becoming qualified as a level 2 chef. I am so proud I’m getting a City and Guilds qualification. It feels good to be doing something positive with my life. I’ve learned a lot of different ways of cooking, I’ve even cooked venison pie and sea bass.

The customers come in from all over Cheshire. They know we are prisoners and the support they show is unreal. I was really nervous at first, as it requires going out of the gate after being in a bubble for so long. But trust me when I say, it’s worth knuckling down and making a new life for yourself.

The women and men at The Clink are there to support in every way possible. Even when you are released, they still work with you for a year, and if you don’t have a place to live they will help you find one too. They will also help to get you interviews. For anyone reading this, wherever you are, you are worth more than this life. Do something positive and change your life.

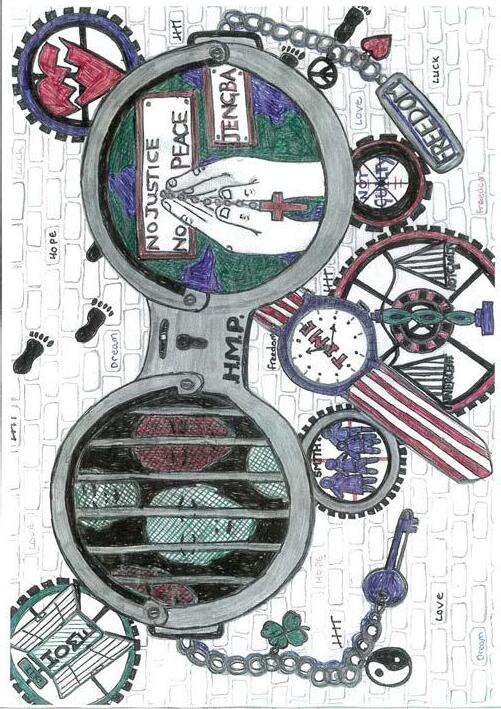

We received some fantastic, creative entries from you following our last magazine edition. Drawing on your own experiences and reflections, here are some of the best poems and artworks you sent in.

Illustrations: PPaint, Nya Moorcroft

Lisa

I was looking for closure but I feel exposed, Like a flower on a hill where nobody goes.

The grass isn’t greener, I’m mindful of that, I’m a prisoner of conscience painting over the cracks. And those walls that surround me, keeping me safe,

Only stand to remind me that I’m losing my faith. I took it for granted that the flower would bloom

Then somebody clicked their fingers And I’m back in my room.

I need a distraction to help me relax, Coz I get no satisfaction from avoiding the facts. Now I’m wracking my brain, so I talk to the quack And say, doctor I think I’m under attack. These walls that surround me are all that I need, But I’m digging a hole with my heart on my sleeve. Then the doctor reminded me that I’m not immune, When somebody clicked their fingers

I woz back in my room.

Everything around me slowly disappears, Looking through the hour glass

Chalking up the years. Oceans full of plastic, rivers full of tears

Strangers in a crowded room answering to peers. Click, click, click, click, Boom!

I’m back in my room.

I look forward to tomorrow, I don’t know what it will bring. I lay my head on the pillow, And soon I am sleeping.

I look forward to tomorrow, Another brand new day. Each days is still very hard and so… I’ll see what comes my way.

I look forward to tomorrow, Always think positive. A day in which to laugh and grow, That’s the best way to live.

Don’t I ever feel sorrow? Are there no reasons to worry?

Of course, but not tomorrow. Tomorrow I will be happy.

In the strip I sat humiliated, defeated, depressed.

It seems that no one cares, do they?

Well it seems not, I am forgotten.

I hear a jangle of keys I bang and shout and swear

It seems as there’s no one there.

Is there?

At last, someone comes, my saviour from this hell – or not.

What do I want the screw shouts at me Just a chat, Guv, I say meekly

Not a chance lad, he grunts.

Is this real or an illusion? Who knows or cares?

In our last edition, Elif from the Left Book Club asked you to share your views on ‘the power of protest’ as part of a writing exercise. Here is an extract of the entry that received a book prize for their thought-provoking submission.

I have been on many protest marches, and some of these have been to Downing Street. I have decided to write on the issue of fighting for the right to vote. As a woman fighting for suffrage*, I reference the suffragettes of the 19th century. Here’s a shocker, I am a woman suffragette, as I am a woman under suffrage who has constantly fought for the right to vote while in prison: in pen, in word, and in legal action against the UK government.

We must be a thorn in the flesh of the government. Anyone who is fighting for the right to vote is by definition a suffragette. The vote was never seen as one thing; it was seen as a gateway issue to addressing all the social ills of the day by giving women a voice. The suffragettes wrapped up all these issues into what they called the women’s cause, the women’s war. I see no difference in this, as all the

issues we are fighting for –as set out in the WIP manifesto – would be addressed more easily if we had a vote in prison.

It has to be noted that anyone who is fighting for a cause they believe in, is by definition a foot soldier of that cause. Emily Pankhurst said that, ‘If it is right for men to fight for their freedom … then it is right for women to fight for their freedom’.

*The right to vote in political elections

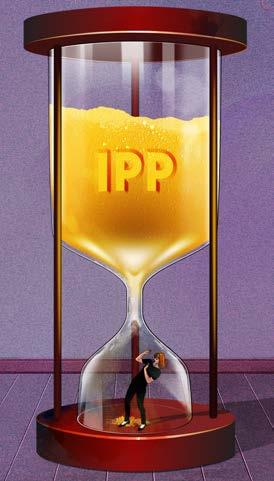

Run by the families of those serving Imprisonment for Public Protection (IPP) sentences, UNGRIPP campaign on behalf of all people a ected by IPPs in England and Wales. Here they explain what IPP sentences are, their demands for change to these sentences, and the role the government should be playing.

Imprisonment for Public Protection (IPP) sentences were introduced in 2005. IPP sentences meant that if a judge considered a person to be ‘dangerous’, and they were found guilty of any one of 153 offences, they could end up in prison for an indefinite period of time beyond the length of the tarriff given for the crime they had committed.

An IPP sentence is made up of three parts:

A fixed time period of imprisonment called a tariff, which reflects the seriousness of the offence.

Followed by an indefinite time period of imprisonment until the person is considered safe for release by the parole Board.

Followed by an indefinite period on licence of at least 10 years, but possibly life.

The government predicted that around 900 IPPs would be given out. But by the time they were stopped in 2012, a total of nearly 9,000 had been given out.

However, IPPs were not stopped for those who already had them; every person previously given an IPP still had to serve it. Today there are 2,892 people in prison on IPPs, 3,249 of whom are on licence in the

community, and 296 in secure hospitals. Altogether, 247 women were given IPP sentences, and there are still 40 women in prison today serving an IPP.

Prison numbers have been going down since 2012, but this year for the first time this trend stopped. An important part of this, is that over half the people serving an IPP in prison are those on IPPs who have been recalled–staying out of prison can be as hard as getting out.

UNGRIPP campaign on behalf of everybody affected by IPPs in England and Wales. We are run by the families of people serving IPPs, and everything we do is guided by the people that IPPs affect most. Our main goal is to ensure their voices are heard. We educate people about IPPs; campaign to overturn IPPs; ensure those serving IPPs are never forgotten; and support people affected by IPPs. We have three main demands:

That everybody serving an IPP should be resentenced to a sentence available under current law that justly reflects their crime.

That the licence portion of the IPP should be reformed.

That the Government should provide comprehensive support to help everybody serving IPPs to recover from their ordeal, including their families.

In the past year, we have worked alongside parliamentarians to get IPP-related amendments into the Police, Crime Sentencing and Courts Act, and have submitted evidence to the recent Justice Select Committee (JSC) inquiry into IPPs. The inquiry found that a resentencing exercise was the only way to fix IPPs. It also recommended other urgent changes, including licence reform. The government rejected these findings, arguing that IPPs can be managed with an action plan under the present system. It has promised a review of IPP recalls by the Probation Inspectorate. The Parole Board has promised to direct members to take the harm caused by an IPP into account.

The government have ignored the huge amount of evidence calling for change. Despite this, the support to overturn IPPs has never been so strong. It is now widely accepted as a valid policy option that the government has ignored. We will continue to push for this change; holding the government accountable to what it has promised.

We want every person serving an IPP to know that someone is fighting for them outside.

To get in touch with UNGRIPP, write to: UNGRIPP, Unit 76570, PO Box 6945, London, W1A 6US.

‘We want every person serving an IPP to know that someone is fighting for them outside.’

Words: Nicky

Imprisoned for non-violent robbery o ences, Nicky was given an Imprisonment for Public Protection (IPP) sentence, designed for people who present a serious public threat, with a minimum tari of two years and one month. Here she reflects on the enormous impact this has had on her life, and the length of time she has now spent in prison beyond her tari .

Iclass myself as one of the unlucky ones, as between 2005 and 2007 IPP sentences were handed out like sweets; although, they were supposed to only be for violent and serious offences. In the robberies I was involved in, no one got hurt. I’m not saying I shouldn’t be punished because I should, but up until now it’s stolen 16 years of my life.

From my two-year and one-month tariff, I’ve basically ended up serving 13 years because what’s expected of you to be considered for release is pretty impossible. The Offender Management Unit (OMU) will say, “Right, we want you to do this course” – a course that doesn’t run in your jail. Then by the time you get to your parole hearing, they will ask, “Have you met your targets? ‘No’. I’m sorry but I couldn’t get myself into

the jail that runs that specific course. So it’s another knock back and most of the blame falls on your shoulders for not having met the targets.

The same thing happens if the parole board directs you to work with mental health. You put the app in, and do everything you can, but just like everything else there’s a waiting list. So when your parole board date comes around and you haven’t worked with mental health, they defer your hearing until the work is done. It’s like trying to push water uphill with a fork, it’s never going to happen! I wake up every day with no light at the end of the tunnel. Some days I don’t feel like getting up at all, but I do; I do it for my dad.

I think it was in January this year, the government made a bold move to review

the sentencing of IPPs. I was over the moon thinking that I was going to get my life back. It was the first time in a long while that I had ‘hope’, and then the Government declined it.

When you’re on an IPP your life isn’t your own. You’re told how to live your life, what friends to have, what not to do, and what to do. I’m a 41 year-old, and once released I will have a 9pm curfew. I will also have to sign in with probation at 1pm and 5pm every day. You can’t plan a day out because when you’re halfway there it’s time to come back and sign in. I thought that probation were supposed to help you better your life? But all they’ve done is hold mine back.

I finally got released in December 2021. I was doing well, and after living with my dad for six months I had my own flat, which I thought was lovely. I started having problems and I relapsed, smoking crack, and probation recalled me. So I’ve now lost my flat and I’ve got to start over again when I’m released. It’s like all those months of negative drug tests count for nothing, they just looked at the one positive test.

Apparently, I wasn’t ‘manageable’ in the community because I was ‘high risk’. How? I had been out for 12 months, committed no crimes, stuck to my appointments, never breached my curfew and gave consistent negative drug tests. Something needs to change. It’s a joke.

‘I had been out for 12 months, committed no crimes, stuck to my appointments, never breached my curfew and gave consistent negative drug tests. Something needs to change.’

Illustration: PPaint

Catherine Heard, Head of the World Prison Research Programme at ICPR, talks to us about ICPR’s research findings around the fast-growing number of people in prison worldwide and the impact this is having on health conditions for people in prison. Within these findings, Catherine identifies convincing arguments for abolishing prisons for women and replacing them with treatment-based, woman-centred interventions.

Can you briefly tell us about the work of the Institute for Crime & Justice Policy Research (ICPR)?

We’re a small team of academic researchers based in the School of Law at Birkbeck, University of London. Our work informs public and political debate on justice issues and helps create better policy and practice. You recently completed a project looking at prisons in ten countries across all five continents. What issues did you look at? There has been an unprecedented worldwide growth in the number of people in prison, with 11 million people in prison in 2021 compared to 8.7 million in 2000. However, there has been no increase in prison places, staffing, or other resources in line with this growth. As a result, most prison systems are now running way over capacity, leading to cramped, unhealthy and dangerous conditions. Our research project asked two questions. One, what has caused this rise in the number of people in prison? Two, what are the consequences? According to your research, with what health problems do people enter prison? Our research shows that people in prison suffer much more mental and physical health problems than general populations outside of prison. They often have worse health due to socio-economic and health inequalities. Infectious diseases like TB, Hep B and C, HIV/AIDS and syphilis are generally more common. This is likely due to a lower immunity, pre-existing health conditions, poverty, substance use, homelessness, or previous time in prison. People entering prison are also at a higher

risk of diseases you don’t catch from others, like diabetes, cancer, heart disease and respiratory illness. The same social problems behind poor physical health also explain the much higher cases of mental health needs of people in prison. What impact did you find prison has on mental and physical health?

We found that prisons make existing health problems worse – and that they can also create new problems. This is due to poor conditions, a lack of treatment and diagnosis, the availability of illicit drugs, social and psychological stresses, violence and mistreatment. Prison also has an aging effect, research shows that typical age-related illnesses seen in people in their sixties often show up ten years earlier among people in prison. Were there di erences in the health related findings across the countries you looked at?

Perhaps the most striking difference we found was in age. There are some countries – including our own, the USA and Australia – where the number of older prisoners is rapidly rising, mainly because sentences have been getting longer. Older prisoners often suffer from chronic physical health problems or mental health issues. They are vulnerable and often receive none of the care, support and treatment that older people need.

Many women enter prison with drug and alcohol problems in the UK, did you find this to be true of women in prison elsewhere?

Research data from around the world shows clear links between the drug or

‘11 million people are in prison in 2021 compared to 8.7 million in 2000.’

alcohol problems women come into prison with and histories of trauma, abuse, poor general health, homelessness, poverty, debt and unemployment. Life challenges like these can easily push substance-dependent women into often repeated contact with the police because they are more often first on the scene when a woman is experiencing severe mental distress. Situations like this frequently escalate into charges, even prison. In some countries even being drunk in public can result in imprisonment.

You talk about a health-informed approach to prison reform, what is this? For most countries, reducing the number of people in prison is the first step to making sure there are better conditions and access to healthcare and treatment in prison. This also means making sure fewer people in poor health enter prison. To achieve that, most countries including our own need to improve healthcare provision in the community, particularly for mental health conditions and addiction and recovery. For those for whom prison is inevitable, there must be proper access to healthcare, screening and treatment, harm reduction measures, and decent living conditions.

The theme of this edition is recovery and support, how does it relate to the work you do?

One issue that struck me from our research was the increased risk of suicide and self-harm within the first weeks and months after release from prison. It’s so important that prison-leavers’ needs are assessed properly, so that community-based services, peer mentor schemes and other

tailored support are in place from the start – and throughout these tough first months. What di erences did you find in relation to men and women in prison?

Since 2000, the numbers of women and girls in prison have increased by over 50%, whereas the numbers of men in prison have increased by about 20%. If you look at the offences women are being imprisoned for, you find striking similarities around the world. Women tend to go to prison for shorter periods, and most are imprisoned either for non-violent property offences or for drug crimes.

Many of the vulnerabilities found in female prison populations – higher prevalence of mental illness, backgrounds of trauma and physical ill-health – mean that prison does them disproportionate, lasting harm. This is the case in developed and less developed countries. I think this is one of the most convincing arguments for abolishing prisons for women and replacing them with treatment-based, woman-centred interventions. Are some countries doing better than others in their approach?

In some countries, including our own, there are examples of schemes created to move people with mental health treatment needs away from the criminal justice system at the earliest opportunity. The problem is that mental health treatment and addiction support services are so stretched and underfunded.

No interventions can be effective when prisoner numbers are too high, or when the available treatment and support resources aren’t properly funded.

‘Since 2000, the numbers of women and girls in prison have increased by over 50%.’

The Prisons and Probation Ombudsman (PPO) carries out independent investigations into complaints and deaths in custody. They tell us about their recent pilot of investigations into people who died within 14 days of their release from prison, and the importance of naloxone kits.

In 2021, we began a 12-month pilot to investigate the deaths of people recently released from prison. We knew that lots of people died quite soon after they left prison, so we decided to focus on deaths that happened within 14 days of release to learn more about the support provided to people when they leave prison.

We continue to investigate post-release deaths today, but during the pilot we began looking into 48 post-release deaths. We found that 50% of these deaths were drug-related, so we wanted to share information about naloxone as it came up during our investigations.

The medicine naloxone can rapidly reverse the effects of an opioid overdose (opioids include heroin and methadone). A dose of naloxone (usually either in a prefilled syringe or a nasal spray) can save someone’s life if they’re given it quickly enough after an overdose – it can also be given before the emergency services arrive.

When you leave prison, you might be offered a naloxone kit. You should also be told how to reduce the risks of a drug overdose, and that your drug tolerance might have changed. Our investigations found that some of the people who died had either not been offered naloxone or had refused to take up the offer of a kit. We don’t know all the reasons why people refused a kit but in some cases people decided they didn’t need one because they were sure they wouldn’t use drugs on their release.

No one will judge you for taking a kit, and it doesn’t mean that you’re going to use drugs when you leave prison.

We would like to see an increase in the number of people leaving prison who are released with a naloxone kit. So please, if you’re leaving prison soon, ask staff about naloxone, and if you are offered a kit, please consider accepting it. It could help save your life, or the life of someone you know.

Some of the women in the Bruce House HMP Styal editorial group share how they find support while on their recovery journey.

Leanna

l What has helped me in my journey has been the house and the girls in here, the friends that I’ve made. My job in the kitchen has also helped because I’m kept busy doing a job that makes me happy – seeing that I have achieved something. I am hoping to get a job in The Clink Restaurant as it will provide me with better opportunities when I go home. Also, my Offender Management Unit (OMU) worker has been great – she’s so easy to get on with and explains a lot of things to me; asking questions has made me feel more confident in knowing what I need to do. Laughing every day with my friends also helps. Seeing my Drug and Alcohol Recovery Services (DARS) worker has helped me stay out of drama and to keep my head down. Getting to know people,

then trusting them makes things easy. I have a long road ahead of me and there will be bumps along the way, but having support really helps.

Emma

l The thing that has helped me along my journey is my job in the kitchens. This gives me a routine and structure every day. I have worked in the kitchens for nearly two years. I think getting a job really helps because you’re keeping busy and it gives you purpose. It has been therapy for my complex PTSD, that, and just having a laugh and talking to the girls. Having support from my peers,keeping a small group of friends is important ‒ I find when you only have a few close friends there’s no drama. I’ve also had lots of help with my mental health.

‘I have a long road ahead of me and there will be bumps along the way, but having support really helps.’

Claire

l The things that have helped me are my family support and friends. My job in the kitchen and doing my NVQ with The Clink charity. Paul, the man that works with The Clink, has put me forward to work in The Clink once I’m outside, which will also help with my new life.

Phooy

l The things that have helped me the most are the support that I get from the girls on the house – just being able to speak freely and know that everyone is

there to help when needed. I came off my methadone on Bruce House and I really don’t think I could have done it on another house as everyone encouraged me. I’ve been an addict for 40-odd years and I’m now free from those shackles, off methadone and drugs in general. My job in the kitchens keeps me busy and I would really suggest a job to keep you busy. I’m doing my NVQ in catering which links into The Clink charity, and it will help me when I’m out. These things helped me, so I hope they help someone else.

We are told it’s important for our health that we get enough sleep. But how do we go about doing this? Karen Smith, WIP WomenMATTA Project Worker, o ers some tips.

any people worry about not getting enough sleep – and that worry can make it even more difficult to fall asleep!

Sleep problems are very common, particularly for women, children, and the over 65s. It is often said that adults need between seven and nine hours sleep a night, but everyone is different, and as individuals we all have different sleep needs during our lifetime.

Understanding sleep, and the different stages of sleep, can help us.

During the night our bodies go through four different stages of sleep – two stages where we sleep lightly; a deep sleep; and then Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep, when we dream. We go through these

stages several times a night, and it is normal to wake several times too. Elderly people tend to have lighter sleep and wake more often.

So what can make sleep more difficult? The charity Mind makes the link between poor mental health and difficulty sleeping, ‘living with a mental health problem can affect how well you sleep, and poor sleep can have a negative impact on your mental health’.

Sleep can also be affected by drug/ alcohol use, or when recovering from drug/alcohol use, and poor-quality sleep can make recovery more challenging.

We can’t sleep if our brains are in ‘fight or flight’ mode – hyper-aroused. This might be because of a present threat to

safety, or because of a history of abuse. This sense of arousal needs to be calmed before we can sleep.

Menopause symptoms, such as hot flushes can also interfere with sleep. So can pain, breathing difficulties, sleep apnoea, anxiety, depression, and restless leg syndrome.

So how can we improve our sleep? This can be challenging in a prison environment where there is little or no control over things like the levels of noise, light, or temperature. But some of the following may help. Each person is different, and what works for one person may not work for another, so it’s important to find out what works for you.

l Try not to worry about getting to sleep.

l Avoid caffeine, sugar and nicotine later in the day.

l Exercise, but not less than a couple of hours before bed.

l Don’t nap after 3pm.

l Try to relax before going to bed – read a book, practice relaxation exercises, try

breathing exercises, such as breathing in slowly for a count of three and then out for a count of six, concentrating on relaxing the body on the out breath.

l Spend time in natural daylight each day if possible.

l Try to stick to a routine, getting up and going to bed at the same time each day.

l Try to keep your eyes open until you can’t keep them open any longer. It sounds odd, but it can work.

l Go through a relaxation exercise when you get into bed. Scan the body in your mind, starting at your feet (or your head) tell yourself, ‘I relax my toes, feet and ankles’, and then carry on working through each part of your body, starting with, ‘I relax (insert body part)’.

If there are any physical or emotional reasons for difficulty sleeping, then speaking with medical staff or a counsellor can help. Otherwise, remember that many people struggle to sleep at times during their life – it doesn’t mean that it will always be like this for you.

Illustrations: PPaint

A qualified psychotherapist, hypnotherapist and energy practitioner, Toni Hannaway has been practising and teaching the Emotional Freedom Technique (EFT) for 20 years. Here she guides you through this life enriching technique.

The Emotional Freedom Technique (EFT) is a simple process created by Gary Craig in 1997. Often referred to as ‘Tapping’, it involves tapping your fingers on certain points of your body to release energy blocks, restoring your body’s energy to a calm and balanced state. Our emotional and mental experiences and many of our physical experiences are recorded within our body’s energy systems, with negative experiences often creating imbalances and uncomfortable sensations.By tapping on the points shown in diagrams 1 and 2 while saying a problem out loud, these sensations can be released to bring about an inner calm. Follow the simple steps below to see if this technique can help you.

GUIDE TO TAPPING

Stage 1

l Think of a specific problem, memory or challenge

l Measure how strongly you feel about this on a scale of 0-10, where 0 = not at all and 10 = extremely strongly

l Create a ‘Set up Statement’ – a statement that includes your problem and your acceptance of it. For example, “Even

though I have this… (insert problem) … I acknowledge how I feel” or “I’m doing my best”. You can use variations of this that feel comfortable for you.

Stage 2

A) Place your hand into the ‘karate chop’ position (see diagram below), hold it here while you bring the fingertips of your other hand up to tap against the bottom edge of your hand in the area below the little finger. While tapping say your ‘Set up Statement’ out loud e.g. “Even though I am sad I acknowledge my feelings”

B) Repeat point A another two times

C) Make up a brief ‘Reminder’ phrase – a shortened version of your ‘Set up Statement’ e.g. “This back pain” “This anxiety”

D) Repeat your ‘Reminder’ phrase as you tap with your index and middle finger (first two fingers) on yourself about seven times on points (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9), as shown in diagram 2.

E) Repeat step D

F) Close your eyes and take a deep breath in, extending your out breath think about your original problem/memory again. Now

rate the intensity of your original issue again, using the 0-10 scale in stage 1

G) If you find your rating is above 2, repeat the tapping procedure again from point A to B adapting it to, “Even though I still feel (relate to your issue)”

H) Adapt your ‘Reminder’ phrase e.g. “This remaining… (your issue)” as you repeat points D and E

I) Repeat point F and repeat tapping until your intensity score is 2 or less. For more serious issues/traumas seek an experienced EFT practitioner.

Beauty out of Ashes has been formed from the ashes of HMP Holloway. Our quest is to bring women and organisations together to provide a holistic, creative and transformative approach to women’s needs and services. Our ultimate goal is to provide a building that will house services beyond the promised ‘Women’s Floor’ on the Holloway prison site.

As part of this project, we are working with Women in Prison to run an exciting art competition in Still I Rise - see the competition details on the opposite page.

Winning and commended artworks will be featured in the magazine and used in the marketing, social media, and website of Beauty out of Ashes to further our cause. We will also hope to hold an exhibition sometime in the future.

There are many prizes for successful submissions!

Artwork by Erika Flowers www.recoededinart.com

Handmade crochet doll by Sara Garcia Menendez

Artwork by Erika Flowers www.recoededinart.com

Handmade crochet doll by Sara Garcia Menendez

How a transformative legacy women’s building could help you?

1 x £20 prizes

3 x £10 prizes

Deadline: August 31st 2023 Results: Next issue

We want to share your creative voice with the world. To enter the competition, we are asking you to use your artistic expression of what Beauty out of Ashes means to you, or perhaps your vision of how an empowered, transformative, future legacy Holloway Women’s Building might help you.

We welcome entries in any medium: painting, drawing, mixed media, craft, or maybe a written piece. The winners will be published in the next issue of the magazine and BOOA will exhibit entries on our website gallery.

Please fill out the consent form on page 65 to give consent for use and acreditation of your work. Please mark the outside of your envelope with ART COMPETITION.

Post to: Freepost Women in Prison

How to play? Fill in the grid so that every row, every column and every 3x3 box contains the numbers 1 to 9, without repeating the number.

Puzzle by websudoku.com

Prison Reform Trust Advice and Information Service: 0808 802 0060

Monday 3pm–5pm

Wednesday and Thursday 10:30am–12:30pm

Prisoners’ Advice Service (PAS):

PO Box 46199, London, EC1M 4XA

0207 253 3323

Open Monday, Wednesday and Friday 10am–12:30pm and 2pm–4:30pm, Tuesday evenings 4:30pm–7pm

Rights of Women

l Family law helpline

020 7251 6577

Open Tuesday–Thursday 7pm–9pm and Friday 12–2pm (excluding Bank Holidays).

l Criminal law helpline

020 7251 8887

Open Tuesdays 2pm–4pm and 7pm–9pm, Thursday 2pm–4pm and Friday 10am–12pm

l Immigration and asylum law helpline

020 7490 7689

Monday 10am–1pm and 2pm–5pm, Thursday 10am–1pm and 2pm–5pm

HARMFUL SUBSTANCE USE SUPPORT

Frank Helpline: 0300 123 6600

Open 24 hours, 7 days a week.

Action on Addiction Helpline:

0300 330 0659

National Domestic Abuse Helpline: 0808 2000 247

Open 24 hours.

LGBTQ+ Bent Bars

A letter writing project for LGBTQ+ and gender non-conforming people in prison.

Bent Bars Project, PO Box 66754, London, WC1A 9BF

Books Beyond Bars

Connecting LGBTQIA+ people in prison with books and educational resources.

Books Beyond Bars, PO Box 5554, Manchester, M61 0SQ

HOUSING Shelter Helpline: 0808 800 4444

Open 8am–8pm on weekdays and 9am–5pm on weekends.

NACRO information and advice line: 0300 123 1999

National Prisoners’ Families Helpline: 0808 808 2003

Open Monday-Friday 9am–8pm and on Saturday and Sunday 10am–3pm (excluding Bank Holidays).

OTHER

Cruse Bereavement Care

0808 808 1677

Open Monday–Friday 9:30am–5pm, Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday 9:30am–8pm and weekends 10am–2pm.

Samaritans 116 123

Disclaimer: please be aware that some helplines will be operating under new opening hours due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

We love to receive artwork, poetry, stories, articles, letters, knitting patterns, recipes, craft ideas etc., for publication in the magazine from women affected by the criminal justice system in prison or the community. Please complete and tear out this form to send along with your piece so that we know you are happy for us to publish your work and what name you would like to use.

Please note that we are unable to return any of the written pieces or artwork that you send to us for publication.

Thank you for your contribution! All the best, the Women in Prison Team.

Please use CAPITAL letters to complete

First Name

Prison or Women Centre (if applicable)

Any Contact Details (email, address, phone)

Title of your piece (If relevant)

Surname

Prison No. (if applicable)

Basic description (e.g. a letter in response to... or a poem or an article on...)

I give permission for my work to be used by Beauty out of Ashes (as outlined in the competition on page 59)

I give permission for my work to be used by Women in Prison (PLEASE TICK):

WIP’s magazine (Still I Rise)

WIP’s online platforms (our website, www.womeninprison.org.uk, and social media, including Twitter, Instagram, Facebook and LinkedIn) Yes No

WIP’s Publications & Promotional Materials (i.e. reports, leaflets, briefings) Yes No

Please note we only publish first names (no surnames) and the name of the prison or Women’s Centre in the magazine (we don’t publish prison names in other publications or online). You can of course choose to be Anonymous (no name used) or write a nickname or made up name.

I am happy for my first name to be published Yes No

Please write exactly what name you would like to be used:

Freepost – WOMEN IN PRISON (in capitals)

No stamp is required and nothing else is needed on the envelope.

Chris Tchaikovsky set up Women in Prison (WIP) over 30 years ago, after serving a sentence in HMP Holloway. Upon her release, she campaigned tirelessly to improve conditions inside prison, to widen the knowledge and understanding of the judiciary about women affected by the criminal justice system, and to end the use of incarceration for all but a tiny number of women.

Chris said: ‘Taking the most hurt people out of society and punishing them in order to teach them how to live within society is, at best, futile. Whatever else a prisoner knows, she knows everything there is to know about punishment – because that is exactlywhat she has grown up with. Childhood sexual abuse, indifference, neglect – punishment is most familiar to her.’