Sir Stephen Jenyns and his family

This account has been produced by Dr Chris O'Brien to mark the 500th anniversary of Jenyns’ death on 6th May 1523, and draws on a wider range of sources than were available to Gerald Mander when he wrote The History of the Wolverhampton Grammar School

Contents Ancestry Apprenticeship, Early Career and Marriage Merchant Taylor Merchant of the Staple Later Career Property Benefactor Family and Legacy Appendix 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Front Cover: Merchant's Mark of Sir Stephen Jenyns. Design by Emma Bowater, based on an example of his seal.

03 07 13 17 22 28 37 45 53

Graphic design by Matt Overton.

Illustrations

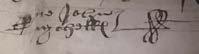

Signature of John Nechells, from a document of 1525. Staffordshire RO

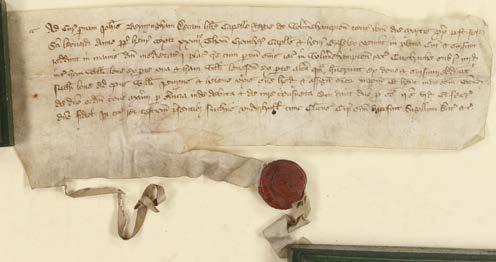

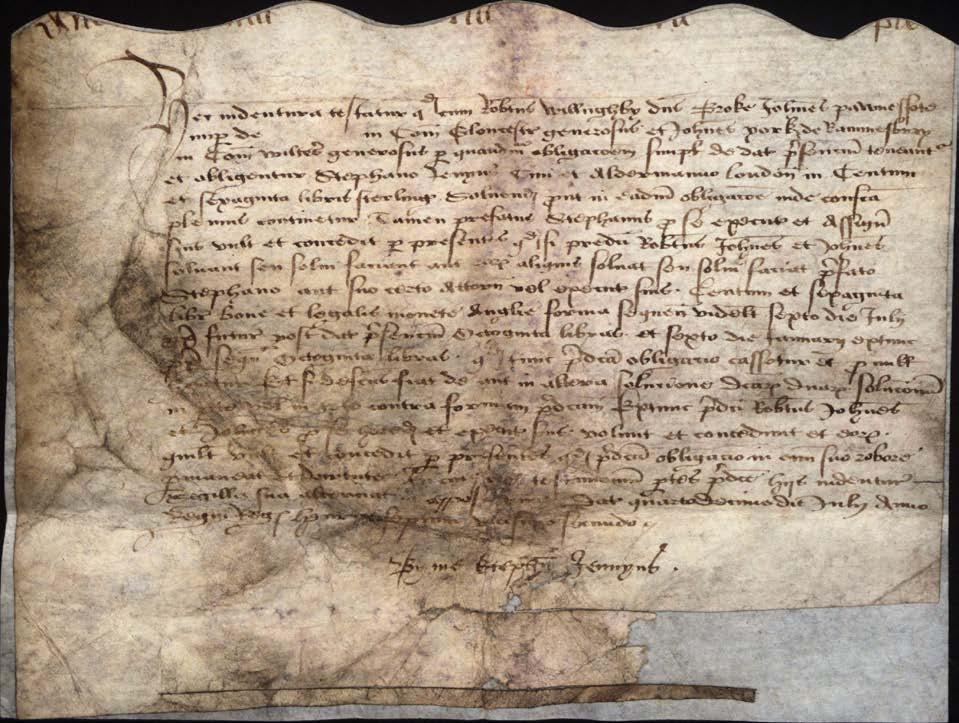

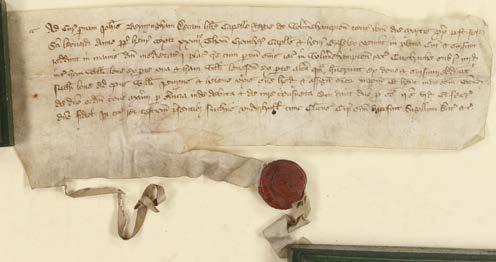

Land transfer to William and Ellen Jenyns, 1445. Cheshire RO

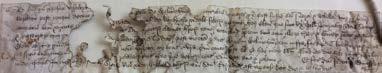

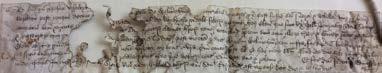

John Jenyns claims his mother’s lands in Wolverhampton, 1495. Cheshire RO

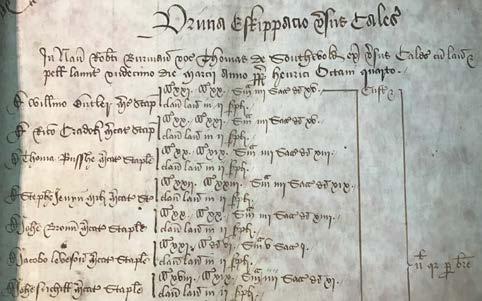

Some imports of Stephen Jenyns, August 1495. National Archives.

The Arms of Goldwell, from the window at WGS

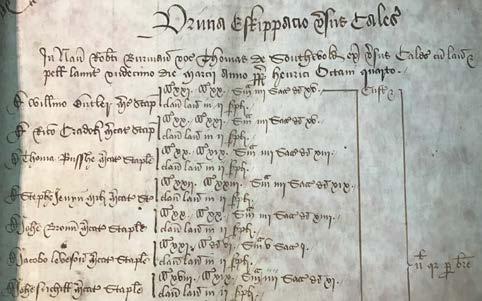

Extract from Wool Customs & Subsidy Particulars of Account, 1512/13.

National Archives

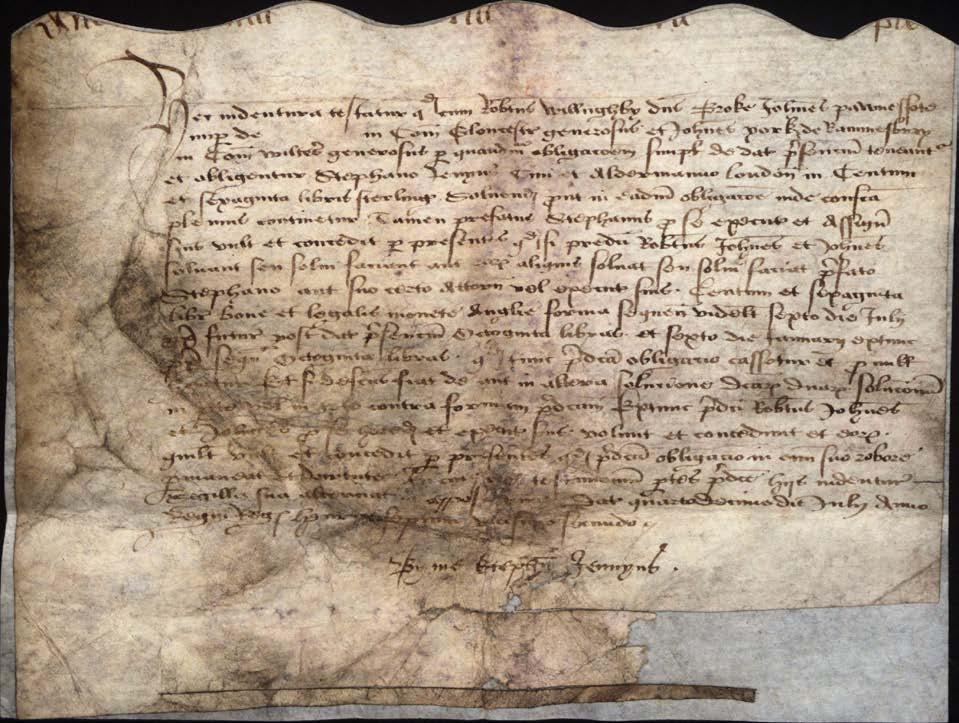

Signature of Stephen Jennyns from TNA C146/5525, 1507. National Archives

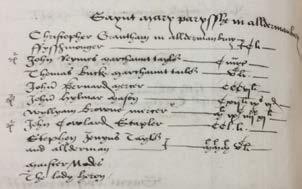

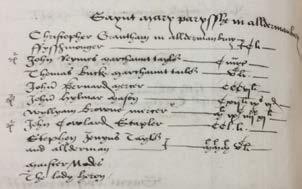

London Tax List for the parish of St Mary Aldermanbury, c. 1522. National Archives

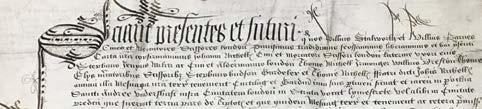

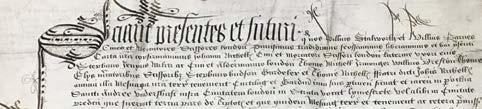

The opening of the deed conveying property in Lime Street to John Nechells, 1509. WGS

Heading to the Court Roll of Perywood for 12th October 1507.

Corpus Christi College, Oxford

Seals from a deed dated 6th December 1506. Corpus Christi College, Oxford

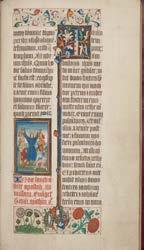

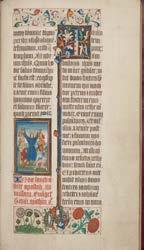

Pages from Gospels presented to St Mary Aldermanbury, 1508. British Library

The remains of Elsing’s Spital as they stand today

St Andrew Undershaft, St Mary Axe

Windows from St Andrew’s Undershaft, now in Big School at WGS

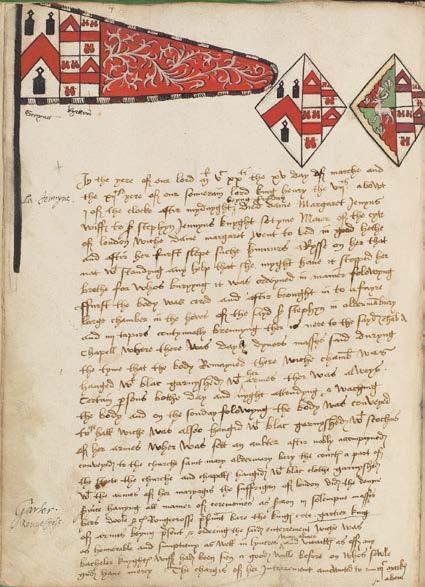

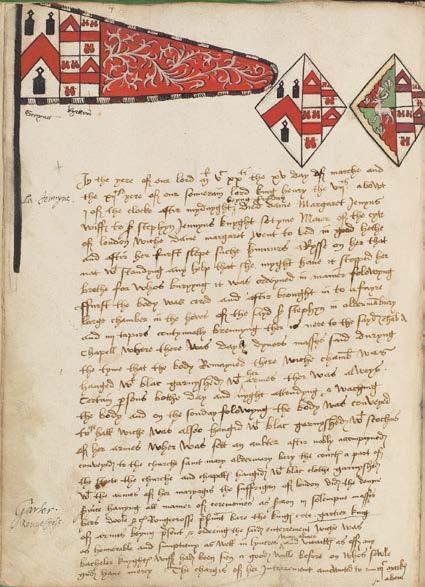

Account of the Funeral of Margaret Jenyns. British Library

Tomb of Sir Stephen Jenyns, drawn By Sir Thomas Wriothesley. British Library

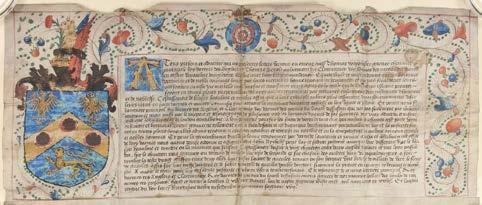

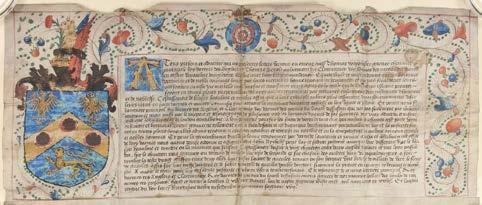

Grant of Arms to John Nechells, 1526. Cheshire RO

The Memorial to Thomas and Joan Offley, in the chancel of St Andrew Undershaft

Stained glass window representing Stephen Jenyns in Big School, WGS

Tables

Cloth exported by Stephen Jenyns, 1477 – 1513

Occupations of tradespeople taken to court for debt by Jenyns

Wool exports of Stephen Jenyns compared with total exports, 1495 – 1522

Total Wool Exports through London, selected years, 1495 – 1522

Wool exports by Staffordshire families, 1495 – 1542

Early Masters of Wolverhampton Grammar School

Family Trees

Ancestry of Stephen Jenyns Descendants of Stephen Jenyns Part of the family of William Offley

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 02 03 04 09 10 17 24 27 33 34 38 37 39 40 40 42 44 50 52 56 08 10 18 19 20 53 05 46 57

Introduction

This account, produced to mark the 500th Anniversary of Stephen Jenyns’ death (6th May 1523), is designed to expand on the details of his career given in Mander’s The History of the Wolverhampton Grammar School. Mander made extensive use of material in the possession of the Merchant Taylors’ Company and of records at the (then) Public Record Office. Much more is now available.

One important source is the Crewe Collection at Chester Record Office. When a descendant of Thomas Offley married the heiress of the Crewes, he changed his name. Thus many of the Wolverhampton documents in the collection relate directly to the Jenyns family. The publication by the Hanseatic Historical Association of the surviving London Customs Accounts has allowed Jenyns’ trading activities to be explored in considerable detail. Online access to records of the Court of Common Pleas also shed light on his world.

Finally, Stephen Jenyns’ probate accounts, discussed in a recent thesis and now available online, supply astonishing detail about the administration of his estate.¹

Acknowledgements

Gerald Mander’s account is the essential starting point for any study of Jenyns and avoids errors concerning his marriages which are present in Clode’s history of the Merchant Taylors and have been repeated elsewhere. I am grateful to Dr Stephen Freeth, the Merchant Taylors’ Archivist for his guidance regarding their archives at the Guildhall Library, to Ellie Wilson for introducing me to the Probate Accounts and to Dr Richard Asquith for allowing me to see his PhD thesis which discusses them in considerable detail. I am grateful to St Helen’s Bishopsgate for allowing access to photograph the Offley monument in St Andrew Undershaft.

I am grateful to Dr Simon Harris and the King’s Benchers group of the Keele Latin and Palaeography Summer School for much help with the reading and understanding of Latin documents, also to Duncan McAllister at WGS for assistance with aspects of the Latin encountered. Nevertheless, all remaining errors of translation are mine.

I thank the following for permission to use images of documents:

No 1, Sutherland papers, reproduced courtesy of Staffordshire Record Office. Copyright reserved.

Nos 2, 3 and 18 from the Crewe Collection, Cheshire Record Office. Reproduced with the permission of Cheshire Archives and Local Studies and the owner/depositor to whom copyright is reserved.

Nos 4, 6, 7 and 8, from The National Archives. Crown Copyright. All rights reserved.

Nos 10 and 11 from the Archives of Corpus Christi College Oxford. Reproduced by permission of the President and Fellows of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, to whom copyright is reserved. I thank also the archivist, Dr Julian Reid, for his guidance in accessing the documents during two visits.

Nos 12, 16 and 17 from the British Library, Copyright, British Library Board. All rights reserved.

Finally, I should like to thank many colleagues at WGS, especially Tina Erskine, John Johnson and Zoe Rowley for their encouragement in pursuing this project over several years.

Chris O’Brien, WGS, May 2023

1

¹Asquith, R M, Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Piety and Trust: Testators and Executors in Pre-Reformation London

Surnames

The School refers to Stephen Jenyns, and this is the spelling most commonly encountered, though Jennyns, Genyns and Gennyns also occur. John Nechells is another matter. In a series of documents relating to purchases and sales of lands in Kent, his name is given in 18 different forms. Treating ‘i’ and ‘y’ as interchangeable, ‘i’ occurs in the great majority of cases for the first vowel and ‘e’ on a little over half the examples for the second. So Nichells is preferable but School usage has been followed. In two surviving signatures, he himself writes Nychelles.

1 Signature from SRO D/593/A/1/30/14.

© Reproduced courtesy of Staffordshire Record Office, 2023. The ‘p’ is short for ‘Per’ and the final loop is an abbreviation for ‘es’: Per me John Nychelles

Margaret Jenyns’ first husband, William Buk or Buck appears with both spellings (and Bukke), but in his lifetime Buk seems to be more common, so that has been used.

Dates have been given in modern form with the year beginning on 1st January, rather than 25th March as it did in Jenyns’ time, so a document dated in the original ‘3rd February 1508’ would be given as 1509.

Money

Money has been given in the original form, pounds, shilling and pence. A mark was two thirds of a pound, i.e. 13s 4d.

The Bank of England inflation calculator suggests that prices in 1500 should be multiplied by about 900 to give a modern valuation. The multiplier does fluctuate quite considerably during Jenyns’ lifetime and is an average. Some quantities require smaller or larger multipliers. The WGS Master’s salary was fixed at £10 per year in 1512, for example!²

²www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator (March 10th 2023)

2

1 Ancestry

The earliest pedigree records Stephen’s parents as William Jennings of Tenby, Pembrokeshire and Ellen (or Helen) Lane of Wolverhampton. His date of birth is not known, but Mander’s suggestion that he was born in about 1448 is consistent with his apprenticeship in the year 1462 or 1463.1

Stephen’s parents were certainly married by 1445. On 9th November that year, in the manor court, Thomas Crouther, chaplain, and Henry Grassley surrendered half of a piece of land in Wolverhampton called Catebruche to the use of William Jenyns and Helen his wife and their heirs. Crouther and Grassley held the land by the gift of Nicholas Lone, and it is said to lie between the property of William Lone on one side and of William Leveson on the other.2

1314. In that year, Robert, son of John in le Lone of Wolverhampton quitclaimed to William, his brother, a messuage in Wolverhampton. Thomas en la Lone and Edith his wife are mentioned in 1345 and 1352. In the latter year, William in la Lene, chaplain, son of Petronilla also occurs. But these names have no obvious link to the main Lane family, as recorded in 1910.4

Stephen’s father’s name is all that is known of his Jenyns ancestry. In about 1495, John Jenyns, by his attorney, Richard Sutton, appeared in the Dean’s Court at Wolverhampton to claim, as the son and next heir of Ellen, who was the wife of William Jenyns, all the lands and tenements which she held of the Dean in Wolverhampton. He is described as ‘Johannes Jenyns de Denbyghe’ which raises a question as to whether Tenby in the pedigree is accurate.5

3

¹Grazebrook, H. Sydney, Visitations of Staffordshire, pp 224-225; Mander, Gerald P., The History of Wolverhampton School, 1913, p 1; GL, Records of the Merchant Taylors’ Company, Wardens’ Accounts, 1453 – 69, MS 34048/2, Apprentices for 1462/63

²CRO, Crewe Collection, DCR 26/3b/9

³SRO, Sutherland Papers, D 593/J/22/7/30(b). This is a 17th century summary of information from a Court Roll which does not survive. 4Mander, History, pp 1 and 365; CRO, Crewe Collection, DCR 35/8/3; DCR 19/11/2&3; DCR 26/3D/13; the Lane pedigree is given in Wrottesley, G, History of the Lane Family, in Collections for a History of Staffordshire, Third Series (1910), in particular pp 141 – 163. 5CRO, Crewe Collection, DCR 19/8C/4

3 CRO DCR 19/8c/4 – John Jenyns claims his mother’s lands in Wolverhampton © Cheshire Archives & Local Studies, 2023, Used by permission. The date is probably 1495 (‘decimo’ in line 2); John Jenyns de Denbyghe is just legible in the third line.

Stephen Jenyns’ probate accounts make several mentions of Nicholas Jenyns, described as the son of Sir Stephen’s brother, and always ‘of Tymby’, i.e. Tenby. The brother is never named, so may not be the John Jenyns mentioned above. The family link to Tenby is, however, clear; perhaps the clerk in the Wolverhampton court misheard the name as the more familiar Denbigh.6

Mander’s argument that the Lane who married William Jenyns was not a descendant of the Wolverhampton Lanes is based on the quarterings given for the Offley family in the Staffordshire visitation of 1663-64. The Lane coat there given corresponds to a Lone family of Kent and Essex. Jenyns does seem to have had a connection to Kent, but this may have come through marriage. The simple explanation that William Lane was connected with the main Lane family of Wolverhampton, however distantly, gains some support form the Crewe documents. The arms given for Joan Offley in the London visitation of 1568 include quarterings for Nechells and Jenyns only.7

In 1418, Robert Bryd of Eccleshall and Richard Calowes acknowledged themselves bound in the sum of £40 to William Lone of Wolverhampton, the obligation being void if the wedding took place before the feast of St John the Baptist between William and Margaret, daughter of Robert Bryd. This seems likely to relate to a planned marriage of Ellen Lane’s father, though there is no direct evidence that it took place. The early pedigree gives Ellen two sisters, Isabel and Agnes and suggests that both died without children, leaving Ellen her father’s sole heiress.8

There is some evidence to contradict this. A document dated 29th June 1461 records that John Dauson and Ellen his wife appointed an attorney to give seisin to William Wrottesley, knight, Hugh Wrottesley, Richard Leveson, John Salford and others in a third of the lands which once belonged to William Lone in Wolverhampton. Ellen is appointing trustees for her Wolverhampton lands following a second marriage (a marriage confirmed by the appearance of William and Robert Dauson, described as half-brothers of Jenyns, in the probate accounts). It implies that, by this date, William Jenyns had died and also that Ellen’s two sisters (or their heirs) were still living.9

6Lambeth Palace Library, MS 1102, Probate Accounts (e.g. f. 8r); The College of Arms has also confirmed that the original of the pedigree has Tenby.

7Howard and Armytage (Ed.) The Visitation of London in the year 1568, p 64. The Jenyns’ arms are stated incorrectly, being given 4 rather than 3 ‘tassels’.

8CRO DCR 35/9/19 for the bond; Grazebrook, Visitations.

4

9CRO DCR 35/9/22; LPL MS 1102, Probate Accounts, ff. 6v., 20r.

Ancestry of Stephen Jenyns

Figure 1: Ancestry of Stephen Jenyns. Unconfirmed links shown with broken lines.

Attempts to identify John Dauson have been unsuccessful. It is possible that he was a Londoner and had an influence on Stephen’s apprenticeship. Roger Dawson appears as a London tailor at about this date and might be related, but nothing definite has been found. A third marriage is also possible: in 1491, Richard Reynolds and Ellen his wife, formerly the wife of Richard Dauson, citizen and barber of London, took an action for debt against four Wolverhampton yeoman and one of Birmingham, alleging debts of £8. Not convincing in itself, especially given the difference in the Dauson forenames, but there is also a record that in 1479, Richard Reynolds, citizen and brewer, made a gift of all his goods to Stephen Jenyns, tailor. The latter is a legal device, but the connection makes the idea of a marriage more plausible.10

The Staffordshire pedigree indicates that Isabel Lane’s husband was named Swerder and that Agnes Lane married a man named Michell, both dying without surviving heirs. This detail is not included in the (earlier) London pedigree. Swerder is an unusual name; John Swerder, a London goldsmith, in his will dated 2nd April 1500, mentions his present wife, Isabel, who was living in September 1501, when she quitclaimed her dower rights in her late husband’s lands to his son Robert Swerder. John Swerder’s sons were probably from his first marriage, so Isabel is likely to have died without heirs.11

5

10TNA CP40/917, Trinity Term 1491, accessed via AALT CP917 F0086 and AALT CP917 D1633; Ledward, Close Rolls, 1476 – 1485, No 573. 11TNA, PROB 11/12/138, Will of John Swerder; Surrey History Centre, Loseley Manuscripts, LM 1659/19 (Details via Discovery website; original not consulted).

As to Agnes Lane, who married a Michell, no definite conclusions can be reached. It is interesting, though, that Thomas Michell, citizen and ironmonger of London, has a connection to Jenyns which long predates his marriage to one of the Offley sisters. In 1509, when William Stalworth and William Barnes (who were holding the property as trustees) conveyed premises in Lime Street to John and Katherine Nechells, Stephen Jenyns and others, to the use of John and Katherine Nechells and their heirs, the first feoffee listed after Stephen Jenyns is Thomas Michell, Ironmonger. It is probable that he also witnessed Stephen Jenyns’ will, though the register copy says ‘Thomas Nychell, ironmonger’. The very large number of names in a pardon roll of Henry VIII’s first year includes ‘Thomas Mychell, irnemonger, of London, late of Wolverhampton, Staffs’. Thomas Michell’s will makes John Nechill, described as his brother-in-law, one of his executors. Finally, the records of the Court of Husting contain a reference to a provision in Thomas Michell’s will (a provision which does not appear in the registered copy) stating that he left a tenement called The Ship in St Mildred, Poultry and £140 for the maintenance of a chantry chapel in the Church of St Olave, Old Jewry for himself, and for William and Agnes Michell, his father and mother, amongst others.12

The fact that Thomas’s mother was Agnes and that he had links to Wolverhampton, together with his early link to Stephen Jenyns give some support to the view that he might have been another Lane descendant. He was a successful man. A portrait of him in the Court Room at Ironmongers’ Hall was described in 1851 as ‘in a black gown and small ruff, with chestnut coloured hair and heavy countenance’ and said to have been painted in 1640, probably from an earlier picture.13

It is not clear whether Stephen Jenyns had any full siblings besides John. Nothing definite is known. Simon Jenyns who is mentioned in Stephen’s will, Robert Jennyns, a London grocer with Wolverhampton connections and William Jenyns, father and son, both resident in Dudley Street in 1532, may all have some link. But if they are connected, it is not possible to say whether they descend from John or from another brother of unknown name.

6

12Document in the possession of WGS; TNA, PROB 11/21/141, Will of Stephen Jenyns; Letters and Papers of Henry VIII, Vol 1, No. 438 (Part III), p. 252; TNA, PROB 11/22/308, Will of Thomas Michell; Sharpe, R.R., Court of Husting, London (1890), Wills for 19 Henry VIII. 13Nicholl, John, Some Account of the Worshipful Company of Ironmongers, London, 1851, p 473 (consulted via Internet Archive)

2 Apprenticeship, Early Career and Marriage

The Wardens’ Accounts of the Merchant Taylors’ Company record that Stephen Jenyns (Janyn) was apprenticed to Thomas Pye when William Person was Master (1462/63), by which time Stephen’s father had died and his mother had remarried. Thomas Pye was a freeman of the Company of Tailors and Linen-Armourers of the City of London, which became the Merchant Taylors’ Company in 1503. He paid the standard 3s 4d to register his apprentice. Thomas was fined 4d in the following year for an unspecified offence. The records of apprentices in the Accounts are damaged and partly illegible, but he took at least two further apprentices, Roger Holbek in 1472/73 and Thomas Bowyer in 1474/75.1

There is a little evidence as to Thomas Pye’s history. He appears in the Hustings in 1446 with Thomas Gresham, both of them recorded as churchwardens of St Michael Le Querne. He is recorded as one of the wardens of the Tailors’ Company about the time that John Prynce was Master (1456), and makes a few appearances in the Close Rolls. Stephen had been apprenticed to a man who was significant in the Tailors’ Company, having served as Warden, but who never served as Master. Thomas Pye does not feature in the records of overseas trade in which his apprentice later made his mark.2

After the brief entry recording his apprenticeship, Stephen Jenyns disappears from the written record until 20th November 1477, when he exported cloth through the port of London. During approximately half of the intervening time, he would have remained an apprentice. Whether he then continued to work for Thomas Pye or for some other master more actively engaged in the export trade is not known. The recently published London Customs Accounts give a good picture of his activities once he began to trade overseas himself.3

The accounts are based on a year commencing at Michaelmas (29th September). Names of the merchants exporting or importing goods can be found only when the Particulars of Account or Controlment Roll have survived. In the Petty Customs, charged on exports of cloth, Stephen Jenyns does not appear in 1473/74, but is present in the next two surviving records, for 1477/78 and 1480/81. He is missing from two short accounts covering periods in 1483 and 1485, but probably exported cloth at other times in those years. He then appears in all the surviving accounts up to that for 1512/13. Fewer of the Tunnage and Poundage accounts, which cover imports, survive. He appears in the four complete sets of accounts which survive between 1487 and 1520 (there are no earlier complete years within his likely trading life). These records can give only an indication of his import activities over a period of more than 30 years.4

Stephen Jenyns first appears as a Merchant of the Staple in the Wool Customs and Subsidy accounts for 1495/96, having been absent from those for 1493/94. This aspect of his career is discussed later.

7

¹GL, Merchant Taylors, Wardens’ Accounts: MS 34048/2 (1453 – 69) and 34048/3 (1469 – 84, damaged) ²Chew, Helena M (Ed.) Calendar of assize rolls: Roll FF, in London Possessory Assizes, pp. 116-129, No 261 for the case involving the churchwardens; Clode, C, Memorials, p. 49, for the reference to John Prynce late master and (among others) Thomas Pye late warden.

3Jenks, Stuart, London Customs Accounts, published online by the Hanseatic History Association, 2016 – 2019. All are part of Vol 74. Referred to here as LCA, with volume and part number as appropriate.

4For the Petty Customs, LCA Part 3 No 3 (1473/4), No 4 (1477/78), No 5 (1480/81), No 6 (1485 – part only); Part 4 Nos 2, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 10 (1490/91, 1502/03, 1506 (part), 1506/07, 1507/08 and 1512/13 respectively); For the Tunnage and Poundage, LCA Part 3 No 6 (1485, part, no appearance); Part 4 No 1 (1487/88), No 3 (1494/95), No 11 (1513/14) and No 13 (1519/20)

Cloth Exports

Cloth was described according to the extent to which the expensive dye kermes (also known as granum) had been used in its manufacture. The great majority of the cloth exported by Stephen Jenyns was made without kermes (described as ‘sine grano’) and taxed at the lowest rate. Higher rates were charged for cloth which was ‘cum dimidio grano’ (dyed partly with kermes) and for cloth dyed completely with kermes (‘cum grano’ or ‘de scarleta’). The dye kermes was composed of the dried bodies of the insect coccus ilicis, gathered in large quantities from a species of evergreen oak in South Europe and North Africa. On at least one occasion, Stephen Jenyns imported this dye.5

A typical entry for a shipment of cloth reads:

‘1 bala cum 17 pannis 8 virgis sine grano’, meaning ‘One bale with 17 cloths, 8 yards of cloth without granum’

‘Bale’ is one of a number of terms used to refer to packing units which have no set size; A standard ‘cloth’ was 24 yards long, so 8 yards is one third of a cloth. The rate of petty customs was 14d per cloth for ‘sine grano’, 21d per cloth for ‘dimidio grano’ and 28d per cloth for ‘cum grano’. In some records, the charge is stated alongside each merchant’s goods, but in other cases only the total quantity is given. In these cases the charge has been estimated using these rates.6

Type of cloth/ Number of cloths (1d.p.)

8

Year Sine Grano Cum dimidio grano Cum grano Worsted (pieces) Tax Due (nearest £) November 1477 - July 1478 50.5 0.3 £3 1480/81 87.7 3.0 £5 1490/91 92.4 3.6 24 £6 1502/03 148.7 1.4 0.6 £9 January to September 1506 196.7 2.5 4.5 £12 1506/07 120.9 £7 1507/08(*) 151.5 1.0 £9 1512/13 46.0 £3

Table 1: Cloth Exported by Stephen Jenyns (*) - one of these shipments was shared with Matthew Boughton

5Jenks, Stuart, LCA, Vol 74 part ii, No 9, Introduction, p xlviii, note 106 for the descriptions of the cloth; OED under ‘kermes’ for the details of the dye. The beetles from which cochineal was made were coccus cacti. 6The quoted entry is from Jenks, Stuart, LCA, Vol 74 part iii, No 5, page 131. Customs rates from part ii, No 9, Introduction p. xx. Entries summarised from part iii, Nos 4 & 5; part iv, Nos 2, 5, 6, 7, 8 & 10. The quantity of ‘dimidio grano’ in 1478/9 has been amended to match the tax charged; entries for Stephen Jamys and Jannys have been assumed to refer to Stephen Jenyns.

Imports: The accounts for Tunnage and Poundage

The nature of the items imported by Stephen Jenyns changed considerably over time. At his first appearance, in the accounts for 1487/88, he imported:

Wine 29.5 tuns (if a tun is taken as 252 gallons, that is 7434 gallons)

Oil 16.5 tuns

Wax 1200lb

Figs & Dates Less well-defined quanities

Almonds More than 550lb

Salt A 'vaga' (about 300lb)

Scarlet Grain (the red dye, kermes, referred to above) 2 hogheads and a bag

The total value of these imports (apart from the wine) was £146 11s 8d, on which poundage of £7 6s 7d was due. The tunnage due on the wine (at 3s the tun) was £4 8s 6d

Seven years later, he imported:

Wine 38 tuns (9576 gallons)

Oil 9 tuns

Wax 5850lb

Woad 85 bales

Iron Approximately 9 tonnes

Osmund (a superior grade of iron from the Baltic) 3 lasts

Flax & Rosin Less well-defined quantities

Bowstaves 1000

De Stephano Jenyns indigena, de navi Tyll Blank [pro] v balis lini iij lastis osmond ml bowstaves j straw cere continente xC lb ........................................................................................................................lxvj Li

From Stephen Jenyns, denizen, from the ship of Tyll Blank [for] 5 bales of flax, 3 lasts of Osmund, 1000 bowstaves, 1 ‘straw’ of wax containing 1000 lb (price).....................................................................£66

The poundage due on this load would have been £3 6s. For the year, the total value of the goods (except the wine) was £292 6s 8d, giving rise to £14 12s 4d in poundage; the tunnage was £5 14s.

Three points may be made here. First, the food items have disappeared. Secondly, he seems to have extended his trading activities to the Baltic. Finally, the total value of his imports (apart from wine) has very nearly doubled, so his trading ventures appear to have prospered.

In the next full account, for 1513/14, he was much less active. His imports were limited to wine (16 tuns), wax (900 lb), woad (31 bales) and 141 ells of ‘verder caddez’ – ‘a rich tapestry ornamented with representations of trees and other vegetation’ (verdure), the ‘caddez’ indicating that it was decorated with caddis, a worsted yarn. The imports, apart from the wine, are valued at £57 10s, attracting poundage of £2 17s 6d, with £2 8s due for the wine. At his final appearance, in 1519/20, his only import ws a small quantity of packing canvas.7

9

4: TNA E122/79/5 m. 21 Imports of Stephen Jenyns, August 1495. © Crown Copyright, 2023

7Jenks, Stuart, LCA, Vol 74, part iv, Nos 1, 3, 11 and 13 for the Tunnage and Poundage accounts; the definition of verder caddez is given in No 11, page 587. The entry shown above is in No 3, page 212

It seems reasonable to suppose that the value of his imports rose steadily between 1487 and 1495. But it is hard to be sure at what stage it began to decline. It was in about 1495 that he became a Merchant of the Staple; the export of wool then began to dominate his trading activities.

The records of the Court of Common Pleas shed further light on his trading. Details here are taken from modern indexes to a selection of records. Stephen Jenyns is absent from those for 1486 but pursues debts in the next, for the Hilary Term (January) of 1489. He appears similarly in the indexes for terms of 1492 and 1498, but not in those for 1490 or 1495 (though in the latter he is engaged in two actions regarding property). His actions for debt in the three available terms of 1489, 1492 and 1498 are summarised in Table 2.

Links between the trades represented in this summary and the items imported are clear. He imported dyes and prosecuted clothmen and a dyer for debt; he imported wine and prosecuted innholders and vintners; he imported bowstaves and prosecuted bowyers. Many of these early cases seem to be connected with payments due for goods supplied, though that has not been found explicitly stated in the court records. Native places recorded for the defendants range from Kent to Chester and from Bristol to Bishop’s Lynn (now King’s Lynn). Many of the clothmen lived in Kent.

The debt claimed from a tailor in 1489 was just £2, putting this claim in the same category as others from tradesmen. But two debts claimed from the son of a Bristol tailor in 1498 totalled £114. These, together with the £40 claimed from a fishmonger in the same year may fall into a different category of debt which dominates cases from 1500 onwards.8

Trade of defendant

Number of actions

Marriages

Stephen Jenyns was married three times. A grant of 1518, in which he gave property for the benefit of the bedeswomen of Elsing’s Spital, asks prayers for:

‘my soule and also the soules of Dame Margarete my wife Margarete & Johane late my wyves Willm Jenyns & Helen his wif my fader and moder Willm Buk late husband to my said wif Dame Margarete & their childres soules’.9

10

Table 2: Occupations of those against whom Stephen Jenyns took actions for debt

Mean

(nearest

Clothman/ Clothier 11 £10 Dyer 1 £4 Innholder/ Vintner 3 £24 Bowyer 2 £7 Brazier/ Ironmonger/ Scythe Smith 3 £5 Merchant/ Mercer 4 £8 Yeoman/ Husbandman 2 £4 Goldsmith 1 £10 Tailor 3 £39 Woolman 1 £15 Fishmonger 1 £40 Esquire 1 £4 8AALT Law CP40 indices for indices to some terms of Common Pleas rolls. 9The Elsing Spital grant (or ‘will as to the disposition only of my viii tenements ...’) is TNA LR ¹5/5.

value

£)

There is no doubt as to the identity of his third wife, Margaret. His first and second wives were another Margaret and Joan, probably in that order. But there is limited evidence as to their identity, none of it conclusive. The suggestions made here are speculative. His two daughters, Katherine and Elizabeth, married between 1498 and 1506 and are likely to have been born in the late 1470s or early 1480s, when he was beginning his trading activities. His first marriage must have taken place in this period.

The Materdale connection

The wills of John Materdale, Master of the Tailors in 1480, and of his wife Katherine both mention the Jenyns family and suggest a close relationship. John Materdale, who made his will on 22nd September 1497 and died between 5th and 15th November 1498, bequeathed to Katherine Jenyns 10 marks in money and a gilt cup. He also gave to Elizabeth Jenyns a cup of silver and gilt ‘the felow of that cup which I gave Anne Jenyns’. His wife was made executrix and one of the supervisors was Stephen Jenyns, who was given £10.

Katherine Materdale’s will was made on 25th May 1506 (proved 12th July). She gave to Stephen Jenyns, Alderman of London, her six best cushions with lily pots and wreaths and a plain salt of silver and gilt, with a cover, weighing 30 ounces. To Elizabeth Stalworth she gave her best carpet, a standing cup with a cover, silver & gilt chased with oaken leaves and a columbyne in the bottom, weighing 35 ounces, and a brass pot ‘that she desyred’.

She gave to Katherine Nechells 2 great brass pots, a washing basin of latten, her great cauldron bound with iron having 2 rings and the great trivet thereto, her coverlet with basil pots lined with blue buckram, a pair of fustian blankets, 2 pairs of her best sheets, her best towel and best table cloth of diaper, her long settle in the chamber with the carpet thereon, a brazen mortar with a pestle thereto, a great spit, a great dripping pan, the great carved chest in her chamber by the window and a ‘potte hings’. She gave to John and Katherine Nechells 6 bowls chased of silver and gilt with a cover with her husband’s mark in the bottom of them, weighing 125 ounces. She made John Nechells and William Barnes (or Barons) her executors, giving them 40s each for their trouble. The witnesses included Stephen Jenyns, citizen & Alderman of the city of London and William Stalworth (the husband of Elizabeth). No relationship with the Jenyns family is stated in either of these wills. John Materdale mentions his son Thomas as ‘Sir Thomas’, which suggests that he was a priest, and his own sister Elizabeth (no surname given). He also mentions a cousin, Joan Huchon. Katherine Materdale also mentions Joan Huchon, referring to her as her servant and confirming her husband’s bequest which has clearly not yet been passed on, as well as bequeathing other items. A number of other individuals are given items but their relationship is not stated. Elizabeth Pellisworth of Epworth is referred to as Katherine’s sister and a number of other people of the same surname receive items; a Pyllesworth or Pilsworth family occurs at Epworth (Lincs) at this time and later, but no Materdale

link has been found.10

The second will mentions Stephen Jenyns, his two daughters and their husbands either as legatees or witnesses. No mention is made of Stephen’s present wife. The relationship is clearly close (the comment about the pot that Elizabeth Stalworth ‘desired’ being particularly interesting) and the bequests are significant. It seems possible that one of Stephen Jenyns’ wives, probably the mother of his children, was the daughter of John and Katherine Materdale, or one of them. Either could have been married before, but when requesting prayers for their souls in their wills, neither mentions another spouse. Katherine specifically requests prayers for herself, her husband and her parents without referring to any other marriage. It is not surprising that the term ‘granddaughter’ is not used in the wills; Stephen Jenyns calls Margaret Stalworth, who was undoubtedly his granddaughter, his ‘cousin’ in his will.

The only known daughter of Katherine Jenyns, who married John Nechells, was Joan (Offley). If Katherine’s mother was Joan, and the daughter of Katherine Materdale, a neat pattern of naming daughters after their grandmothers is created. On the other hand, one of Elizabeth Stalworth’s daughters was named Margaret.

There is an interesting, early link between Materdale and Jenyns. In December 1483, Peter Pemberton, gentleman, of Eltham, Kent, released and quitclaimed to Stephen Jenyns and John Matyrdale, tailors, Henry Lee, fuller and William Lettres, scrivener, citizens of London, and two others, their heirs and assigns, all his rights in a messuage called Le Keye opposite Romeland in St Albans and in 40 acres of land, 32 of pasture and 10 of woodland in the towns and parishes of Tytenhanger, Burstowe and Park in the county of Hertford, which Stephen Jenyns had bought from him and which he and other feoffees now held.11

That Jenyns was connected in this way with John Materdale at about the time his daughters must have been born supports the idea that his wife could be a Materdale daughter. Unfortunately, no further evidence as to the eventual disposal of this land has come to light; it is possible that the transaction had something to do with the Company rather than an individual.

John Materdale’s will also mentions an Anne Jenyns, to whom he says he had given a cup. This may suggests that there was a third daughter, but it is also possible (since the source is the register copy of the will rather than the original) that the clerk made an error and Katherine Jenyns is intended.

11

10TNA: PROB 11/11/509 Will of John Matirdale; PROB 11/15/188 Will of Kateryn Materdale. The term 'lily pottes' refers to decoration showing a lily growing in a flower pot, symbolic of the Annunciation (OED); basil pottes must have a similar meaning. The term 'potte hings' is unclear. 11Ledward, Close Rolls, 1476 – 1485, No 1328

The Goldwell connection

Mander points out in The Wulfrunian that part of the heraldic glass from St Andrew’s Undershaft now in Big School at Wolverhampton represents the arms of Goldwell. A survey of the glass in St Andrew’s made in the 1920s shows that one window on the south side then had Stephen Jenyns’ merchant’s mark, the arms of Jenyns impaled with Kyrton, the arms of Goldwell impaled with Watton and the arms of the Merchant Taylors’ Company. Elsewhere, in the north aisle, the arms of Goldwell (alone) appeared with those of Nechells. Mander suggests that this could imply that one of Stephen Jenyns’ wives was descended from the Goldwell family. The impaled arms should suggest a Goldwell married to a Watton.12

Goldwell and Watton were both significant families in Kent, the Goldwells being based around Great Chart and the Wattons around Addington. The most prominent of them was James Goldwell, Bishop of Norwich (1472 to 1499) and Secretary of State to Edward IV.

A link between Jenyns and the Goldwell family can also be made through some of his property transactions. Between 1502 and 1509 Jenyns built up an estate in and around Selling (near Faversham) in Kent. Most of the property purchased had at one time belonged to Reynold Dryland. Reynold’s wife Christian, born Christian Haute, was the sister of Alice, the wife of William Goldwell of Great Chart. In addition, Jenyns bought from John Haddes of Rochester, a Dryland heir through his mother, eight London properties near St Paul’s. When he gave these to Elsing’s Spital in 1518, he asked prayers not only for his own family but for eight named members of the Haddes family. It has not, however, been possible to identify any specific Goldwell descendant who could have been the wife of Stephen Jenyns.13

No firm conclusions can be drawn. The tentative suggestion made here is that Stephen Jenyns’ children were born to a wife who was the daughter of John and Katherine Materdale and that his other wife was a member of the Goldwell family. It may be significant that his granddaughter, Joan, made no claim to the arms of Goldwell. But there is insufficient evidence to give any real confidence in these conclusions. It is possible that the surviving children were born to different wives. It is certain, however, that Jenyns had a wife who died after 1496 and that his third wife was not the mother of his children.14

12Note on the Old Glass from St Andrew Undershaft (unsigned, but almost certainly GP Mander) The Wulfrunian, Vol XXXV, No 2, pp 89 - 90. Historical Monuments, Vol 4 ‘Plate 15: Painted Glass, 15th-17th Century’ and ‘Aldgate Ward’, p. 15 and pp 4-13. Consulted via British History Online; Eden, F. Sydney, Heraldic Glass in the City of London, in The Connoisseur,Vol 93, pp 249 - 255 The Connoisseur via Internet Archive which has a good illustration of the Goldwell and Nechells arms together 13These land sales are discussed later. For the relationship between Christian Dryland and Alice Goldwell, see TNA C1/9/1 and C1/39/106, in both of which they are stated to be the daughters and heirs of John Haute of Pluckley. The Haddes family are mentioned in TNA LR 15/5..

14Rose Swan, in her will (TNA PROB 11/11/346) made on 1st December 1496, gave £4 and a black gown to the wife of Stephen Jenyns, tailor. This was not Margaret Buk, whose first husband was still living.

12

5 The arms of Goldwell Window originally in St Andrew Undershaft and now at Wolverhampton Grammar School.

3 Merchant Taylor

It is not known when Stephen Jenyns became a freeman of his company and a citizen of London; nor can it be established when he was granted the livery of his craft. At the time of the earliest surviving minutes of the Tailors and Linen Armourers, in 1486, he was already a member of the Court of Assistants, the senior members. It was usual to serve as warden before becoming master, so he was probably a warden before 1486. In the minutes for Monday 17th April 1486, though not listed as present, he is one of six appointed to ‘commune with the Drapers’ concerning the ‘sheeting in of Blackwell Hall’.

The minutes of 405 meetings between 1486 and 1493 survive (though most of 1487 is missing) and names of those attending are given for 82 of the meetings. Jenyns attended 36 of these, the first being on 7th August 1486. In many other cases, either nothing is said of the attendance, or the phrase ‘in the presence of the master and wardens’ is used. He would have been present at almost all the meetings held in his year as master. He attended just under half the meetings in the year before he was master (9 out of 20) and more than half between 1491 and the end of the records in 1493.

Jenyns was elected Master on St John the Baptist’s day (24th June) 1489, to serve for the ensuing year, in succession to William Buk, whose wife he was later to marry.¹

The minutes show that he was appointed to deal with a number of specific matters for the Company. In 1490 and again in 1492, he was one of two men appointed to arbitrate in a dispute between fellow tailors. This was a common practice; there is no record of the nature of the disputes or of the results. On 22nd November 1490, Jenyns and William Galle (Master, 1471) were assigned to supervise the repairs and rebuilding of the Saracen’s Head, a property of the Company in Friday St, adjoining St Matthew’s Church.²

On 17th July 1492, he was one of four masters (including William Buk) assigned to ‘prosecute the bill against foreigns’, meaning that they were to urge the City government to do more to introduce tighter controls on those who had not been apprenticed in London (whether from overseas or elsewhere in the kingdom). He and Buk were retained in this commission in the following April, to ‘pursue the bill and petition’ put to the Mayor and Aldermen ‘for the reformation of all foreigns that they hereafter work with no freeman and citizen of this city’.³

In July 1493 Jenyns was one of three former masters, along with the present and immediate past master and others, required to be ready on Wednesday 10th at 6 am to meet at St Peter Westcheap to view all the lands owned by the tailors. At the same time, it was agreed that he should be one of those who were to go to the house of William Hert (master, 1491/92) to hear his accounts for his mastership.4

When Jenyns himself accounted for his term of office in 1490, he inspired a major change in practice. He declined the allowances previously given to masters (namely 13s 4d for gathering in of the apprentice money, £4 for wine, 26s 8d for a dinner, 6d for garlands at the feast and £6 10s for the clothing of the master, wardens, clerk and beadle), returning £12 which he had been allowed, and the court agreed that these sums should not be allowed to masters in future.5

13

1Much of the detail in this section is taken from Davies, Matthew The Merchant Taylors’ Company of London: Court Minutes 1486 – 1493, Richard III and Yorkist History Trust, 2000, including his biography of Stephen Jenyns, pp 293-4; summary of attendance at meetings is p 51, pp 12 – 14 (Table 1); p 135 for election.

2Davies, Minutes, p 170, p 194, p 173

3Davies, Minutes, p 200, p 243. Spelling in quotations has been modernised for clarity in this section.

4Davies, Minutes, p 255

5Davies, Minutes, pp 166 - 167

Disputes

This public profile did not come without controversy. On 8th April 1489, Richard West, Stephen Jenyns and Thomas Randall (all past or future masters) each promised under oath, on behalf of himself and his household, ‘to behave and conduct themselves rightly and honourably towards Ralph Bukberd and his household, in words as well as in deeds’. Richard West was Thomas Randall’s father-in-law. Randall’s career followed a very similar pattern to Jenyns’; both first occur exporting cloth in 1477/78 and importing wine and other items in 1487/88. Both exported wool as merchants of the staple in 1495/96, but in the case of Randall that was his only appearance in the wool accounts, and he disappears from other customs records by 1509. Ralph Bukberd was also involved in the overseas trade, importing alongside Jenyns and Randall in 1487/88 and 1494/95 and exporting one load of cloth in 1502, but not dealing in wool. In 1506/07 he became one of the Customers, responsible for collecting the customs in the port of London. The dispute may, therefore, have a connection to overseas trade. On 29th March 1490, Master Galle and Master Pemberton with two others were appointed to arbitrate between West, Randall, William Green and Ralph Bukberd – which sounds like a continuation of the same dispute, except that Jenyns no longer appears and is, in fact, appointed to supervise the arbitration. The dispute was settled on 7th April, when it is described as being between Randall and Bukberd.

In March 1493, William Barton, who had been summoned to the Hall in a dispute about an apprentice, complained that ‘he had never had right justice in this place’ and that ‘Master Jenyns served him like a false Judas when he was Master of this fellowship’. This was described as ‘ a great infamy and slander to this worshipful place and company’. No detail of his complaint about Jenyns is known.

In August 1492, a dispute between Master Hede and William Bunt was put to the arbitration of Willliam Grene and Nicholas Nynes, with Master Jenyns as ‘umpire’. If the arbitrators could not agree, Jenyns was to decide. When Hede came to the court he said ‘Stephen Jenyns should not be his judge, nor the Master neither, for Stephen Jenyns had caused him to lose £38’. Master Povey then said that he must be his judge – but Heed objected to him as well. The case was then referred to the Mayor, who committed Heed to prison for five days ‘in which time he sobered and mollified his impetuous agony and ire’. Then he submitted himself to the court, and to the arbitration. The alleged £38 loss remains unexplained.6

A dispute about Jenyns’ actions at a later stage of his career brought him into the courts. He had been appointed executor, with Nicholas Nynes, tailor (Master, 1496) and John Peynter, grocer, of the will of Rose Swan, widow of John Swan (Master, 1470/71). She made her will in 1496 and the executors proved it in March 1497. One of her bequests was to an orphan, John Story, who was then living with her. She gave him £40 and a considerable quantity of household items, including a gilt standing cup, a dozen silver spoons and a bed with hangings. As John was only 9 years old, she committed him and his inheritance to the care of Nicholas Nynes until he came of age. John Story, Merchant Taylor, was one of the witnesses to Jenyns bequest to Elsing Spital in 1518, but In or after that year, in the Court of Requests, he claimed that Jenyns, the only surviving executor, had retained money due to him. He also suggests that the executors shared large sums of money from Rose Swan’s estate and has a tale about ‘a bote with golde the wiche whas hid in the grounde’. He based his claim, in part, on the fact that Jenyns has paid him £3 10s, which he said was part of his legacy. Jenyns said that the money and goods were committed to Nynes and his wife in accordance with the terms of the will; he had employed John Story as his servant and agreed that he paid him £3 10s in salary. In response, Story said that if Jenyns had paid the legacy to Nynes, he should have made Nynes give a bond for payment to Story. He also said that he had been given other sums of money. The records of the decisions of the court at this period do not survive. It seems that the dispute was still going on when Jenyns died; an entry in the Probate Accounts for 2nd December 1523 shows that John Nechells gave Story as ‘a recompense for certain bequests of Mistress Swan’ six and a half yards of black cloth and four and a half of black lining to make gowns for Story and his wife and 20s 8d in money. On Easter Eve in 1524, Story was given a further 10s ‘for his comfort to pray for Master Jenyns’ soul’. Clearly Nechells wanted to settle the matter and leave no bad-feeling.7

14

6For the disputes, Davies, Minutes, pp 131, 156 – 7, 202, 207 – 209, 239; for a general discussion of disputes, 25 - 28 7TNA REQ 2/4/91 with Story’s replication to Jenyns’ answer in REQ 2/13/7. The Court records for 8 – 11 Henry VIII in REQ 1/4 have been checked (online, AALT) without success. The bill of complaint addresses Wolsey as cardinal and lord legate, which suggests a date in or after 1518 for the beginning of the case. The limited will is TNA LR 15/5. Probate Accounts: LPL, MS 1102, f.3 and f. 8v

Ceremonies

The minutes also illustrate the ceremonial aspects of the public life of the Company. It was the custom for the Mayor, after his election, to process on the Thames to Westminster, escorted by senior members of the crafts, in order to be presented to the King. Jenyns probably took part in this procession on many occasions. In his year as master, the minutes record on November 13th ‘paid for a barge to attend upon the mayor, 13s 4d; paid for drink for the boatmen, 16d’. Less than a month later, a barge was again required ‘for the encounter with the Prince’, referring to the ceremonial associated with the creation of Prince Arthur as Prince of Wales. In November 1492, the Mayor had written to the master and wardens, requiring them to find 30 horseman in gowns of violet to meet the King when he returned from France following the conclusion of the Treaty of Etaples. Stephen Jenyns was one of four former masters to join Walter Povey and 25 other tailors on this occasion. The masters were allowed 13s 4d for their costs (the other members had to make do with 10s). The King was met at Blackheath on 22nd December by the mayor and aldermen and ‘a competent number of Commoners clothed In violet’ who escorted him to St Paul’s Cathedral and on to Westminster.8

The minutes end in 1493, but Jenyns, as a former master and senior member of the Company must have been involved in similar disputes and events for the rest of his life.

Apprentices and Servants

Stephen Jenyns certainly took apprentices, but his career spans a period when the surviving records are sparse. The Wardens’ Accounts, in which his own apprenticeship is recorded, continue until 1484, but are badly damaged after about 1470. Apprenticeships are recorded in the published minutes between 1486 and 1491 (which do not cover most of 1487), but between then and Jenyns’ death there are no records. Wills and other sources do give clues, but may be misinterpreted.

John Nechells and William Stalworth were probably Jenyns’ apprentices. Stalworth refers to Jenyns as ‘my Master’ in his will. Both certainly worked with or for him. Stalworth could have become free of the Company through patrimony, his father being a freeman, but he may have been apprenticed to Jenyns. Nechells was exporting wool as a staple merchant by 1502, so a date of apprenticeship after 1491 seems unlikely. The most likely possibility is that both were apprenticed before the published Minutes begin in 1486.

One apprentice is recorded in the minutes, Thomas Leek of Granby, Nottinghamshire, the son of another Thomas Leek, gentleman. He was apprenticed for eight years from 1486, but does not feature again.

John Reymes is mentioned as Jenyns’ ‘servant’ in 1506, in relation to an incident which sheds interesting light on the way in which the law operated at this time. There are two cases in the Common Pleas, in which it is alleged that Nicholas Halleswell, physician, John Churchgate, yeoman and John Jones, yeoman attacked Reymes at a house belonging to Jenyns in the parish of St Martin’s, Ludgate, using swords, sticks and knives, and beat, wounded and mistreated him ’so that his life was despaired of’ (these are standard words in the writ and need not be taken too seriously). In one case, Reymes claims damages for his injuries. In the other, Jenyns claims for loss of the services of his servant for a month. As the case proceeds, Churchgate makes a counterclaim that Reymes attacked him and the ultimate outcome is not known.9

Reymes appears in the assessment of 1522 as a merchant taylor living in the parish of St Mary Aldermanbury (100 marks). In December 1523, the Accounts note that £24 13s 4d of a debt he owed to Jenyns had been cancelled, because of his good and long service to Jenyns. He also assisted in the distribution of the estate. At his death, in 1547 or 1548, he held a lease of the parsonage of St Mary Aldermanbury, bought from the Court of Augmentations and owned other property there. His son was named Stephen; his wife was from Cranbrook in Kent and lived at Sissinghurst when she died.

William Barnes is identified as a former apprentice and servant of Jenyns in the probate accounts. He was living in Jenyns’ house in Thames Street when John Benett made his will in 1527. He appears with Reymes in a transaction concerning the Selling lands in 1517 and as a merchant taylor from 1516. Early in 1528, John Nechells gave him £33 from the estate towards ‘the great losses and charges that he has had’.

8Davies, Minutes, Introduction pp 41-43, pp 145, 146 (and n. 250), 221 9TNA, CP40/977, Trinity 1506, AALT Image D1901, AALT Image D1997 and next image, AALT Image_D2094 and CP40/978, Michaelmas 1506, AALT Image F0244 and AALT Image F0248.

15

John Bond (or Bound) and William Smith are described as Jenyns’ servants in the will. Both appear in the 1517 transaction. William Smith later married Jenyns’ granddaughter Margaret Stalworth and was both a merchant taylor and merchant of the staple.

As stated above, John Story is mentioned to have been paid as Jenyns’ servant and was working for him in 1518, but they then seem to have fallen out.

Two apprentices are mentioned in Jenyns’ will: his wife’s nephew, Stephen Kyrton, who married the widow of John Nechells, and John Wethers. In 1528, Nechells paid the Chamberlain of London for Wethers’ freedom. Both were Merchant Taylors and Merchants of the Staple and both died in 1553. Kyrton was Master in 1542 and Alderman for Cheap Ward from 1549 until his death.

These may not all have been apprentices and there will certainly have been others. Nechells, Stalworth, Barnes and Reymes were active in Jenyns work for many years, beyond any apprenticeship term, and must have been trusted associates. Reymes was entrusted with the use of Jenyns’ seal on one document associated with Kent.10

16

10TNA E179/251/15B, f. 57v for the London taxation list. Wills of John and Joan Reames TNA PROB 11/32/152 and PROB 11/44/18; Probate accounts LPL MS 1102, ff. 4v, 8r; CCC Twine vol 26 pp 115 – 116; Wills of Jenyns and Benett given in Mander, History, Appendix 4, pp 353 – 363 Probate Accounts LPL MS 1102, f.22 for Barnes, ff 5v, 6 for identification of Margaret Stalworth’s husband; f.26v for Wethers.

4 Merchant of the Staple

Stephen Jenyns did not export wool through London in 1493/94. He appears as a Merchant of the Staple in the next available Wool Customs and Subsidy Accounts, for 1495/96, and then in every surviving account up to 1520/21 except for 1505/06, which is incomplete, listing only eight shipments.

Exports were made in two forms, wool and wool-fells (sheepskins). Stephen Jenyns traded mainly in wool, but also exported wool-fells in three of the years for which there is evidence.

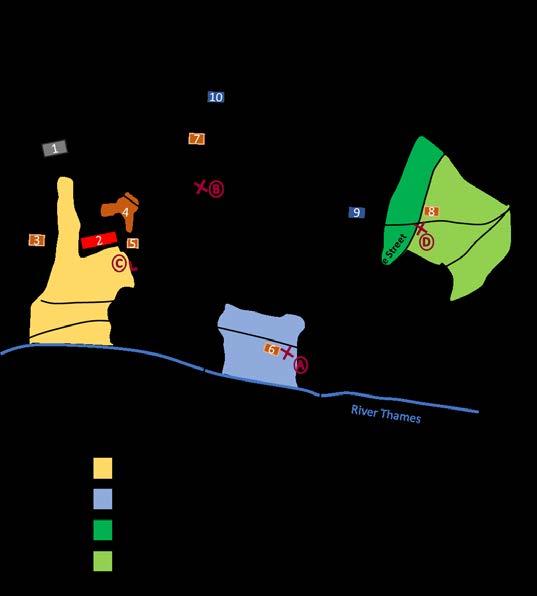

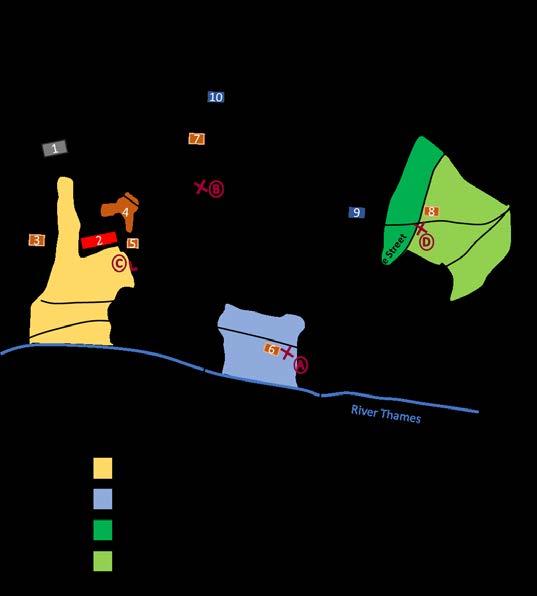

The heading reads ‘The first shipment towards Calais’ and below ‘In the ship of Robert Burman called Thomas of Southwold going towards Calais with wool and woolfells 11th March in the 4th year of the reign of King Henry VIII’

Wool was measured in sacks. A sack was 364 lb and was divided into 52 cloves of 7 lb. Many of the words are heavily abbreviated and ‘2 sacks’ appears as SS rather than using numerals A typical entry, from the account above, reads:

‘De Stephano Jenyn, milite, mercatore stapule, [pro] 2 saccis 22 [clavis]; 2 saccis 23 [clavis]. Summa 4½ sacci 19 clavi in 2 serpleris’

‘From Stephen Jenyns, knight, merchant of the staple, [for] 2 sacks 22 cloves; 2 sacks 23 cloves. Total 4½ sacks 19 cloves in 2 sarplers’

This means that the wool was packed in two bales or sarplers, one containing 2 sacks and 22 cloves (882 lb) and the other 2 sacks and 23 cloves (889 lb). The sarpler was not a measure of weight, but the sack was. Although the units of weight were sacks and cloves, making the total in the above example 4 sacks and 45 cloves, the use of half sacks in the accounts, as in the example, was standard.

17

6 TNA E122/204/2 f. 1 Wool Customs & Subsidy Particulars of Account, 1512/13 © Crown Copyright, 2023. Used by permission.

The accounts record that no customs duty had been paid, because it was collected centrally by the Company of the Merchants of the Staple. The tax due on wool had two parts, 6s 8d for customs and 33s 4d for the wool subsidy, making 40s (£2) in total for each sack. 240 wool-fells were equivalent to a sack of wool in this calculation.

Fleets of ships sailed to Calais with the wool, usually two or three times a year. Merchants did not load all their wool on one vessel. They spread the risk across several ships. Eight ships sailed on 11th March 1513, and Stephen Jenyns had wool on four of them. Wool on the Thomas was also owned by Richard Cradock (of a Stafford family and connected by marriage with the Offleys), James Leveson (of the Wolverhampton family; his brother, Nicholas, also had wool in several of the ships in this sailing), John Nechells (son-in-law of Stephen Jenyns) and William FitzWillam, master of the Tailors in 1499. Apart from Fitzwilliam, all these names can be seen in the extract above.1

Stephen Jenyns’ exports of wool in the years for which figures are available are given in Table 3, where they are compared with the totals for the year. The figures relate entirely to wool and wool-fells exported from London to Calais. Stephen Jenyns did not export from London to any other place in any year for which records survive. Records available for other ports have not been studied in any detail. The quantity of wool is given to the nearest sack; the customs and subsidy due has been calculated using the accurate figures but is rounded to the nearest pound. Since some folios of the records are damaged and merchants’ names cannot always be read, these figures represent a minimum; some shipments may have been omitted. The first sailing to Calais in the year 1522/23 was on 15th April 1523, three weeks before Stephen Jenyns died, so his absence from the next set of accounts is unsurprising.

1Jenks, Stuart, LCA; the example is taken from Vol 74, part iv, No 10, page 5 and the customs rates from part ii, No 9, Introduction, xix – xx.

2Jenks, Stuart, LCA, Vol 74, part iv, Nos 4, 8, 9, 10, 12, 14. The volumes are indexed by surname etc. The total exports are taken from Jenks, Stuart (Ed.) The Enrolled Customs Accounts, Part 11 and Part 12 for the figures up to 1516/17. Later figures are recovered from the totals in the detailed accounts. Those for 1517/18 are incomplete, as a result of damage to the originals, but it is reasonable to suppose that the proportion exported by Jenyns is approximately correct.

18

Stephen Jenyns’

Customs & Subsidy due Total (wool only) exported via London % sent by Stephen Jenyns Year Wool (sacks) Wool-fells 1495/96 52 1869 £120 5546 0.9 1501/02 93 11251 £280 2875 3.2 1507/08 78 9068 £231 3033 2.6 1509/10 144 250 £288 3965 3.6 1512/13 94 £189 2487 3.8 1516/17 99 £199 3339 3.0 1517/18* 96 £182 2451 3.7 1520/21 25 £50 2126 1.2 1521/22 45 £90 2087 2.1

Table 3: Wool exported by Stephen Jenyns compared with total exports (wool to the nearest sack and customs etc to the nearest £) (*) The total figure for this year is incomplete²

exports of:

Stephen Jenyns was responsible for more than a fortieth of wool exports from London to Calais in all the years between 1501/02 and 1517/18 for which figures are available. Table 4 shows how this places him in relation to other exporters. The records have been investigated in detail for a selection of the above years. Wool was sometimes exported by partnerships of two merchants. In these cases, the quantity has been split equally between them. These figures include wool-fells.

Table 4: Total exports (wool and skins), to the nearest sack, taking 240 skins as equivalent to 1 sack. Before 1517, totals based on Enrolled Accounts; later totals based on LCA.³

On his first venture as a merchant of the staple, Jenyns was (just) in the top one-third of exporters. It may have been a temporary growth in the wool trade which drew him to it. Between 1485 and 1494 the total of wool and fleeces exported through London to Calais was usually between 4000 and 6000 sacks per year, with a low of 1143 sacks in 1490/91. But quantities rose steadily between 1491 and 1495; 1494/95 and 1495/96 were exceptional years, with 8000 and 7100 sacks respectively. The figure did not then approach 6000 until 1510/11 and was usually in the range 3000 – 5000 sacks. Jenyns perhaps saw an opportunity when there was more than enough wool to be managed by the existing merchants. Richard Craddock of Stafford and Jenyns’ fellow tailor Thomas Randall also appear for the first time in 1495/96. Thereafter, Jenyns remained a significant exporter, generally in the top ten, until almost the end of his life.

It seems certain that the Jenyns operation had a base in Calais. In October 1532, Simon Jenyns (who is named in Jenyns’ will) had to lend his house in Calais as part of the accommodation for the retinue of Francis I of France during his visit to Henry VIII there. Thomas Offley is said to have lost lands in Calais when the French took it in Mary’s reign. Jenyns probably maintained an agent at Calais throughout his period of trading. There is no direct evidence that he travelled to Calais himself, but that also seems quite likely. A set of obligations given by staple merchants, promising that they will not leave Calais for any place under the obedience of the Archduke of Burgundy and will return to England by a specified date, includes many of a similar standing to Jenyns and with Staffordshire connections – Richard Evans and Richard Helyn of Wolverhampton, Richard Craddock of Stafford and John Fitzherbert of Wolverhampton.4

Extending this account to other families and beyond Jenyns’ lifetime, three families with clear Staffordshire links exported wool through London to Calais. The Craddock and Jenyns families, who first appear in 1495/96 were joined in 1501/02 by Nicholas Leveson. He was based in London and Kent and began in a very small way with 2.4 sacks. By 1507/08 his exports had climbed to 104 sacks and he had been joined by his Staffordshire based brother, James, with a smaller contribution of 16 sacks.

19

Year Number of Merchants Total Sacks Median per Merchant Stephen Jenyns Position 1495/96 144 7108 27 60 48 1507/08 105 4247 26 113 7 1509/10 114 5205 29 145 10 1512/13 113 3724 21 94 9 1517/18 105 2916 20 96 2 1521/22 96 3033 25 45 27 3See note 2 4TNA E101/517/11. This is

the only reference to a John Fitzherbert in Wolverhampton

Table 5 records the contributions of the three families to the staple exports in the years up to 1542. The following are included:

Jenyns: Stephen; his son-in-law John Nechells; John’s brother Thomas (1509 to 1518); John’s second wife, Margaret (Offley), who exported in her own right while a widow in 1531/32; Margaret’s second husband, Stephen Kyrton, who had been apprenticed to Jenyns; Thomas Offley; Simon Jenyns.

Leveson: the brothers Nicholas and James, Nicholas’s widow Dionisia, who exported in her own right for many years after his death; several of the next generation in both families.

Craddock: Richard of Stafford (d. 1503/04); his son Richard, citizen and draper of London (1501/02 until his death in the 1530s); his son, Edmund, (started 1530/31 but died before 1534). The younger Richard’s daughter, Elizabeth, married another stapler, John Bush of Gloucestershire, but his exports have not been included.5

5The first Richard Cradoke’s will is TNA PROB 11/14/77. The younger Richard’s daughter is mentioned as his heir in several Chancery cases, for example C1/724/42.

6The totals are taken from the Jenks, Stuart (Ed.) The Enrolled Customs Accounts, Part 11 and Part 12 for the figures up to 1516/17 and calculated from the LCA for later years, except that information for 1531/32 and 1541/42 is taken from the original records, Particulars of Accounts for 1531/2, TNA E122 204/6 and for 1541/2, TNA E122 204/9. The printed accounts are in Jenks, Stuart, LCA, Vol 74, part iv, Nos 4, 8, 9, 10, 12, 14, 15, 17 and 18. Volume 16 was not available online at the time this work was completed. Totals for years after 1517 may be underestimated because of damage to the originals.

20

Year Total Sacks Craddock Family Jenyns Family Leveson Family Overall % of total 1495/96 7108 45 60 1% 1501/02 4236 56 140 2 5% 1507/08 4247 31 190 120 8% 1509/10 5205 78 253 215 10% 1512/13 3724 48 157 170 10% 1516/17 4404 60 204 185 10% 1517/18 2916 59 154 150 12% 1520/21 3974 53 91 153 7% 1521/22 3033 51 153 155 12% 1522/23 1841 45 113 149 17% 1523/24 3106 28 119 144 9% 1525/26 2832 22 78 167 9% 1526/27 4342 33 141 213 9% 1530/31 1259 23 118 177 25% 1531/32 1833 15 57 181 14% 1533/34 1151 46 152 17% 1534/35 2330 26 210 10% 1539/40 3699 351 399 20% 1541/42 3367 332 389 21%

Table 5: Total exports of three families with Staffordshire links6

These three families accounted for 10% or more of staple exports through London in the majority of years from 1510 to 1535, with a peak of 25% in 1530/31 when total exports were very low. After the death of John Nechells (1530), the Jenyns contribution, represented by Thomas Offley and Stephen Kyrton, fell markedly for a number of years, but by 1539/40 both were exporting large quantities of wool. Although this exploration has not been taken beyond the published accounts (except for one year from original records), Thomas Offley remained a major exporter throughout his life. The inventory taken at his death includes nearly 62 sacks of wool of various grades, valued at £1445, in his wool house in London with a further 2800 lb of wool, valued at £134 at his manor of Madeley in North Staffordshire. This wool was said to have been ‘received out of Staffordshire from William Burton’. Also at Madeley was ‘one old bay gelding that was accustomed to carry packs of wool’.7

Although the three families mentioned have been treated as distinct, they were related. Early records of the Offley family indicate that one of two sisters named Dorynton or Dorrington married Thomas Offley’s father, William, and the other married a Mr Craddock, probably Richard the elder of Stafford. So Thomas was a cousin of Richard Craddock the younger. The Craddocks had property in Lime Street, as did John Nechells. This may have been the link which brought Thomas Offley to Nechells as an apprentice. No direct link between the Leveson and Jenyns families is known, but Richard Leveson was one of the feoffees when Stephen’s mother, Ellen and her second husband John Dauson put her Wolverhampton lands in trust in 1461. By the 1540s, James Leveson had married Margery Offley, sister of Thomas and formerly the wife of Thomas Michell, ironmonger.

These commercial ventures were not without their risks. The staple merchants spread their exports across many ships to reduce the risk of losing large quantities at sea. One instance in which Jenyns did lose merchandise is recorded. The Enrolled Account for 1511/12 refers to 7 sacks and 24 cloves of wool, part of a total cargo of 46 sacks, 20 cloves and 400 woolfells which the merchants were permitted to export In replacement for wool shipped on 6th March 1510 and lost when the Anna of Barking was shipwrecked.8

Jenyns’ probate accounts suggest that, towards the end of his life, he became a member of another trading society, the Company of Merchant Adventurers. Alderman Hardy was paid £6 13s 4d to recompense him for money he had paid for Jenyns’ ‘fredome amongist the merchant adventores’. How old a debt this was is not stated.9

21

7Inventory of Sir Thomas Offley, TNA PROB 2/423. The beginning of the inventory is missing, so the date of the inventory made at his London house is not clear. This is followed by an inventory of his house at Hackney, also undated, and by the Madeley inventory, made 23rd October 1582

– the day before his will was proved in London.

8Jenks, Stuart The Enrolled Customs Accounts, Part 12, p 2938 9LPL, Probate Accounts, MS1102, f. 12r

5 Later Career

Stephen Jenyns was elected one of the Sheriffs of London on Midsummer Day 1498, to serve for a year from that September. In 1499, he became alderman for Castle Baynard Ward, moving to Dowgate in 1505 and Lime Street Ward in 1508. He remained alderman for this Ward until his death.

Each of the two Sheriffs had their own court, dealing with small debts. Records of these courts do not survive, but Jenyns is mentioned as Sheriff in connection with one inquest later referred to the King’s Bench. On 14th January 1499, Thomas Bradshawe, the coroner, with Sheriffs Thomas Bradbury and Stephen Jenyns held an inquest in the parish of St James, Garlickhithe, into the death of Thomas Harryson, a brewer. The jury found that Harryson, armed with a long staff, had attacked William Zouch, gentleman and that Zouch, in fear of his life, had killed him with a wood knife. In May, Zouch was pardoned by the King on the grounds that he had killed in self-defence.1

Third Marriage

Jenyns’ third marriage was to Margaret, the sister of John Kyrton, a lawyer who was party to many of his land transactions. She was first married to William Buk, a prominent member of the Tailors’ Company who was master in 1488/89. He had substantial business dealings, not in the export and import trade, but in sales of cloth and clothing in England. He supplied cloth to the household of the Dean of St Paul’s throughout the period 1479 – 1497. For example, in the year 1482/83, ‘Medley-coloured woollen cloth for the livery of the Dean’s servants at Christmas’ and ‘Black woollen cloth bought for the livery of the Dean’s servants for the burial of King Edward IV’. He supplied the Great Wardrobe under Henry VII: ‘The aforesaid William Buk for 340 yards of russet cloth at 4s per yard - £68’. There is also a record of an action for debt which he took against the Receiver General of Elizabeth de la Pole, Duchess of Suffolk (sister of Edward IV), claiming that £34 4s 8d was owed for cloth which he had supplied.2

William Buk died on 28th March 1501; Margaret had married Stephen Jenyns within a year of his death (she is mentioned as his wife in a suit in the Common Pleas in the Hilary term of 1502). The marriage linked two wealthy families. On 7th June 1503, Jenyns, with Nicholas Nynes, Thomas Randall and William Stalworth entered into recognisances in the City Chamber for payment of £740 6s 8d to John, William, Matthew and Thomas, sons of William and Margaret Buk when they came of age. This is rather more than they had been given in Buk’s will (£100 plus some plate each). Buk’s daughter, Agnes is not mentioned in this bond and was probably already married to Christopher Rawson. William owned a capital messuage and other premises in St Mary Aldermanbury, which were bequeathed to Margaret Buk for her life and then to each of their four sons and their heirs in succession. If all died without children, Agnes, was to inherit. The Inquisition Post Mortem for William Buk was not held until 1532. It may be significant that this was after the death of John Nechells.3

22

1TNA KB9/419 No 8, King’s Bench indictments, Easter Term 1499 (AALT Image). TNA KB27/951 King’s Bench Plea Roll, Easter Term 1499, m. 6 (Rex) (AALT Image). The date, obscured in the indictment, is clear in the roll.

2Kleineke, Hannes & Hovland, Stephanie R, LRS Volume 40: Household Accounts of William Worsley; TNA E101/416/9, Imperfect Account Books of the Great Wardrobe, p 26, accessed through AALT Image (image 87). Further references to William Buk (images 86 and 87); TNA CP40/907, dorses, image 1131, AALT Image

3TNA CP40/971 fronts, image 55 accessed through aalt law ; LMA, COL/AD/01/012, Letter Book M (Mf copy); Will is TNA PROB 11/12/299; Fry, GS, Abstracts of Inquisitiones pp. 28-43, accessed through British History site

Connections

In 1503 the Tailors and Linen-Armourers secured a new charter from Henry VII and became the Merchant Taylors, a move which was most unpopular with the other companies. A leading light in the negotiation of the new charter was William FitzWilliam (Master in 1499) who was associated with Jenyns and two other tailors, James Wilford and Richard Hills, in the purchase of a messuage in Thames Street in 1495. He became, like Jenyns, a merchant of the staple as well as a tailor, but did not export wool (in the surviving records) until 1507/08. Henry VII required the City to elect him Sheriff in 1506. The King is also said to have played a part in the election of Stephen Jenyns as Mayor in 1508.

The relationship between Jenyns and leading figures of Henry VII’s reign is not clear. As a wealthy man, he would have attracted the attentions of those intent on gathering income for the King. Some in a similar position were persecuted to extract funds, but there is no direct evidence that Jenyns was treated in this way and the Taylors were in favour during the reign, as the grant of a new charter demonstrates. But Jenyns had links with leading figures such as Sir Richard Guildford, Edmund Dudley, Andrew Windsor, George Neville (Lord Bergavenney) and Robert, Lord Willoughby de Broke.

In 1495, Jenyns and his fellow tailor, Thomas Randall, were connected with Guildford in a transfer of premises called The Antelope in Westminster. In 1501, Stephen Jenyns and Edmund Dudley were two of the five feoffees transferring a messuage in St Leonard, Eastcheap to William Stalworth and Thomas Morys. When a Sussex gentleman, Roger Lewknor, was imprisoned for murder, Dudley sold him a pardon in exchange for his estates. In a common recovery during the Hilary Term, 1508, Lewknor’s manor of Sheffield (in Surrey and Sussex) was transferred to feoffees including, besides Windsor and Dudley, both Stephen Jenyns and his brother-in-law John Kyrton.4

There are other links to Dudley. The house in St Mary Aldermanbury which Jenyns occupied after his third marriage was purchased by William Buk from Edmund Dudley. It had previously been owned by John Middleton, a mercer. Middleton’s oldest son, another John, had confirmed in 1482 that his father had left it to his widow, Elizabeth, for her life and then to his younger children, but later it passed into Dudley’s hands. The younger John Middleton was the first husband of Sir Thomas More’s second wife. William Buk’s will mentions an apprentice, Robert Dudeley, who later worked for Jenyns, but his link, if any, to Edmund is unknown.5

More significantly, an undated list headed ‘Here after folow suche sumes of money as I Edmund Dudley must see the kynges hyghnes paid and answered of’ begins: ‘First two thousand poundys that is to say (£1,000) in crownys and oon thousand poundys in Gold which (£2000) was recevyd of Dauncy by the Kynges Warrant in the name of Rasemus Ford for the which (£2000) Stevyn Jenyns Alderman and other or elles other sufficient persons shuld have byn boundyd by Recognisances’. At the foot of this page there is an additional note: ‘Also I must have delyvered to my handys a lytyll box with three obligations for £2000 of Stevyn Jenyns and other’. Bonds therefore existed which would enable pressure to be put on Jenyns if required. The list is undated but must be after 1504, when Dudley began to work directly for the King. When Henry VII died, three former mayors, including Jenyns’ immediate predecessor, Lawrence Aylmer, were in prison on various pretexts and would probably have had to pay for their release. Is it possible that Jenyns would have been treated in a similar way if the King had not died during his term of office?6

Sir Andrew Windsor was Keeper of the Great Wardrobe, perhaps a natural link for Jenyns, but in the limited surviving records, there is no evidence of Jenyns supplying cloth to the Wardrobe. William Buk and William Stalworth, son-in-law of Jenyns, did. Stalworth supplied ‘four and a quarter yards of tawny cloth, price 5s 6d per yard’ and Buk several items, including ‘two and three quarter yards of scarlet cloth, price 11s per yard’ besides the russet cloth mentioned above.7

George Neville, 5th Baron Bergavenny, appears in several documents relating to the purchase by Jenyns of lands in Kent. In 1502, Neville and his wife Joan quitclaimed to feoffees including Jenyns, John Kyrton and William Stalworth, five messuages in Friday Street and Watling Street, London. It was also Bergavenny who sold the manor of Rushock to Jenyns in 1512. He had been fined heavily for retaining during Henry VII’s reign and may have needed to raise money.8

4Penn, Thomas, Winter King, p 263; TNA CP40/983, Common Pleas, Hilary, 1508, AALT Image D924; LMA, Court of Husting, Pleas of Land CLA/023/PL/01/171 m.20

5TNA C 146/5198; PRO 11/12/299 for the Will of William Buk; LPL Probate Accounts MS 1102 f.6r

6TNA SP46/123 Miscellaneous letters and papers f. 148 Memorandum by Edmund Dudley of debts to the crown. Rassmus (Erasmus) Ford appears in the customs accounts. Amounts in () are in roman numerals in the original. Dauncy refers to John Daunce, one of the tellers of the Exchequer. Penn, T, Winter King, p 347

7Undated account, probably 1490s, in TNA E 101/416/9, consulted via AALT Images 86 and 87

8LMA, Court of Husting, Deeds and Wills, CLA/023/DW/01/229 m. 8&9; for Rushock, see later

23

before him, but there is no evidence to show whether this happened.

9There are two copies of the Chancery Bill: C1/287/38 (AALT Image 0065) and C1/279/41. Details regarding the Queen’s death from Weir, Alison: Elizabeth of York. For Bulstrode as Customer, Jenks, Stuart, The Enrolled Customs Accounts, Part 11, p 2711. The Privy Purse accounts of Henry VII appear in Bentley, Samuel Excerpta Historica (1831), p. 130 (Reference from Wikepedia article Stephen Jenyns.) 10The cases against York and Pawnesfote are in TNA CP40/990, Plea Roll, Hilary Term 1510. r. 334 (dorse) for York and r. 338 (dorse) for Pawnesfote, AALT D0623 and AALT D0632 . The original bond is TNA C146/5525. The Chancery case is TNA C1/348/66, available on AALT Image 117 ; for Broke, Luckett, D.A., The Rise and Fall of a Noble Dynasty, Historical Research Vol 65 (1996) pp. 261-265

24