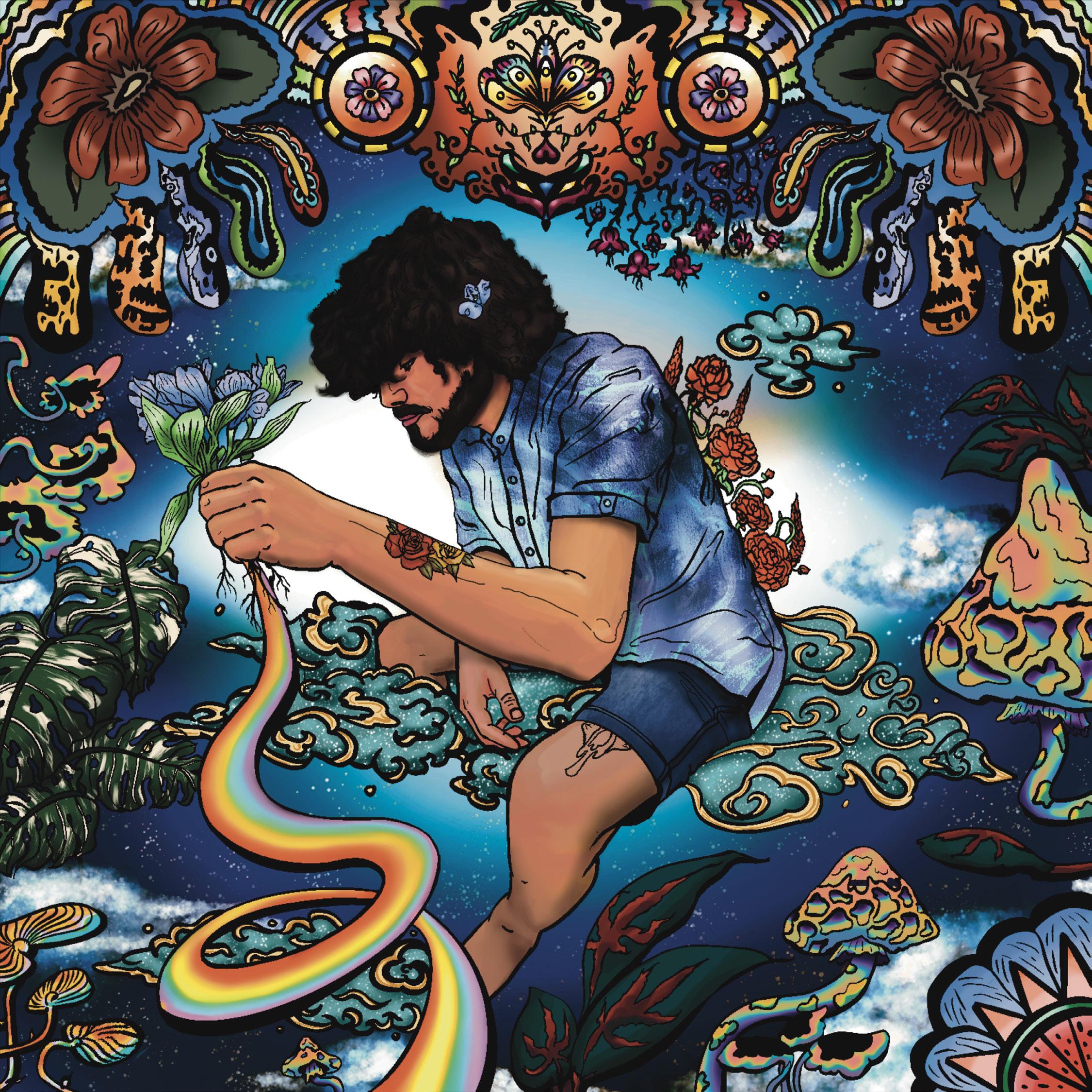

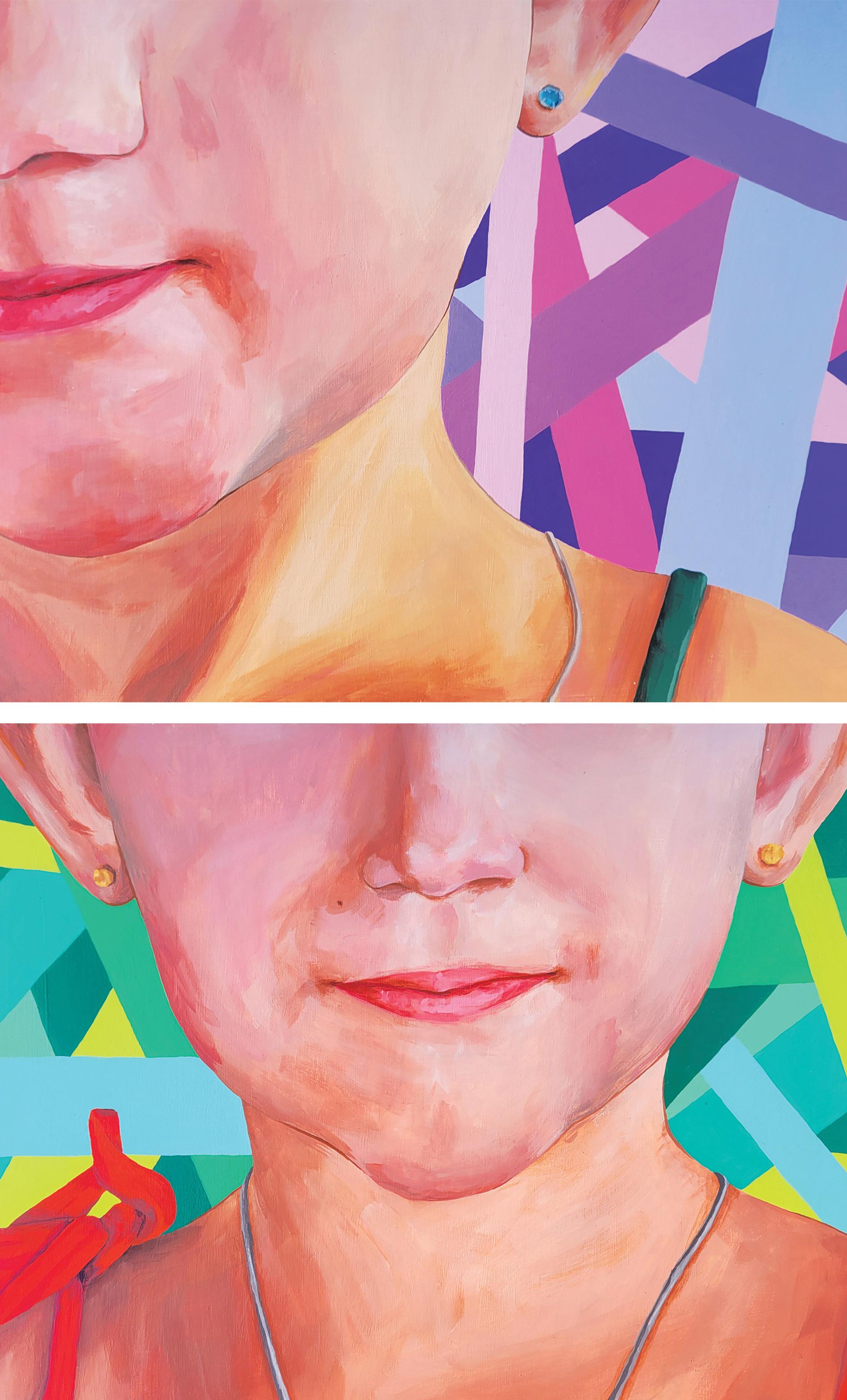

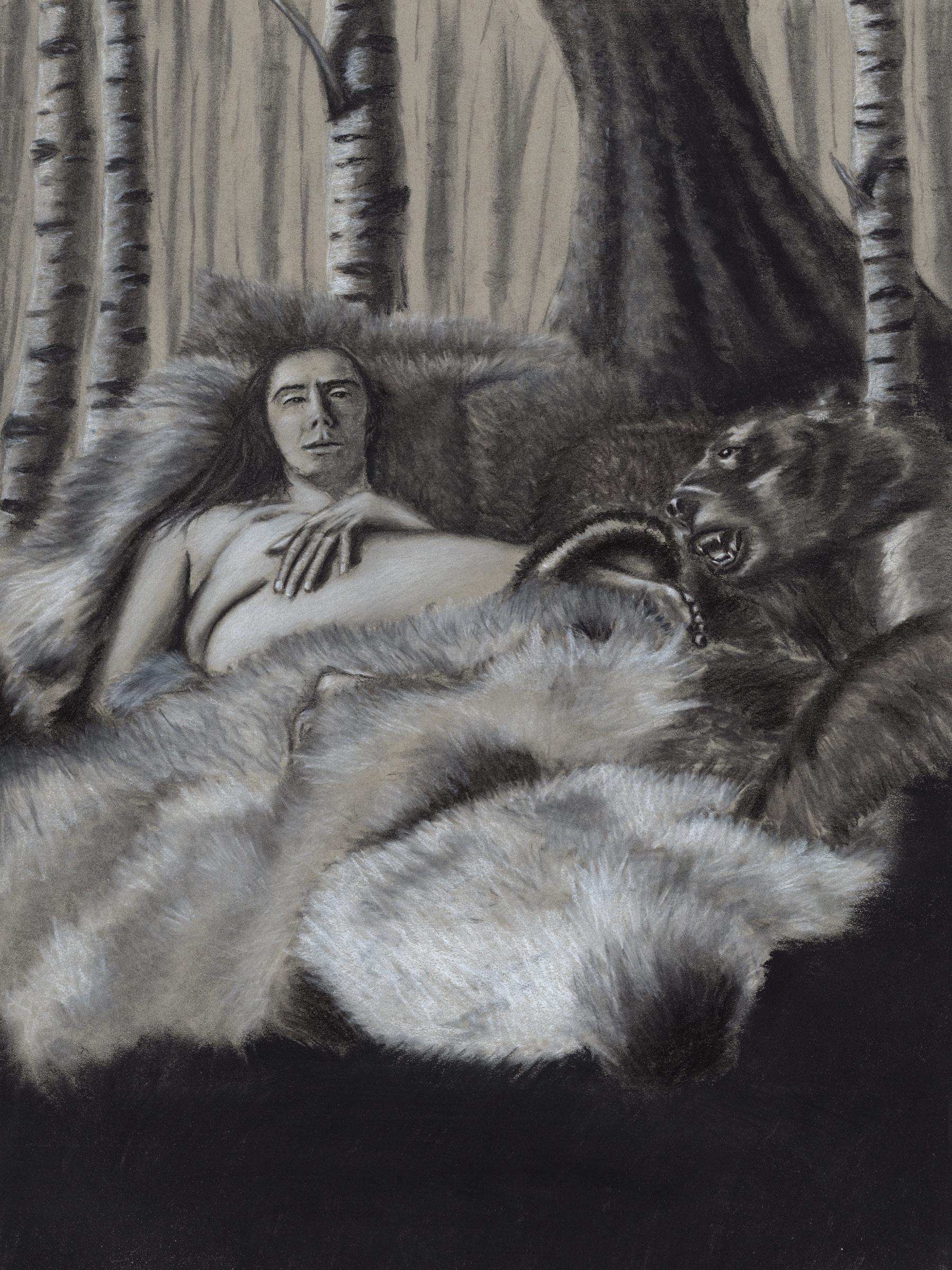

The mission of Illumination is to provide the undergraduate student body of the University of Wisconsin-Madison a chance to publish work in the fields of humanities and to display the talent of emerging creators. As an approachable portal for creative writing, art, and scholarly essays, the diverse content in the journal intends to be a publication for academic and community interests alike.

EIC: Fiction/ Non-Fiction Editors:

Poetry

Editors:

Keara T. Wood

Avianna Hite

Emily Laskowski

Lauren Downham

Evan Randle

Jane McCauley

Paige Dixon

Art Editors:

Hailey Maynard

Mandy Choy

Sophie Schultz

Jay Lee

Layout Editor: Marketing Coordinators:

Grace Zhang

Meredith Schadrie

Peyton Hennig

Memorial Union

Memorial Union

Dear reader,

Whoever you are (student, contributing author/artist, proud parent of said author/artist, roaming Martian who crash-landed in Wisconsin and has recently discovered the many wonderful things that can be done with cheese), I would like to formally welcome you to the Spring 2024 edition of Illumination Journal.

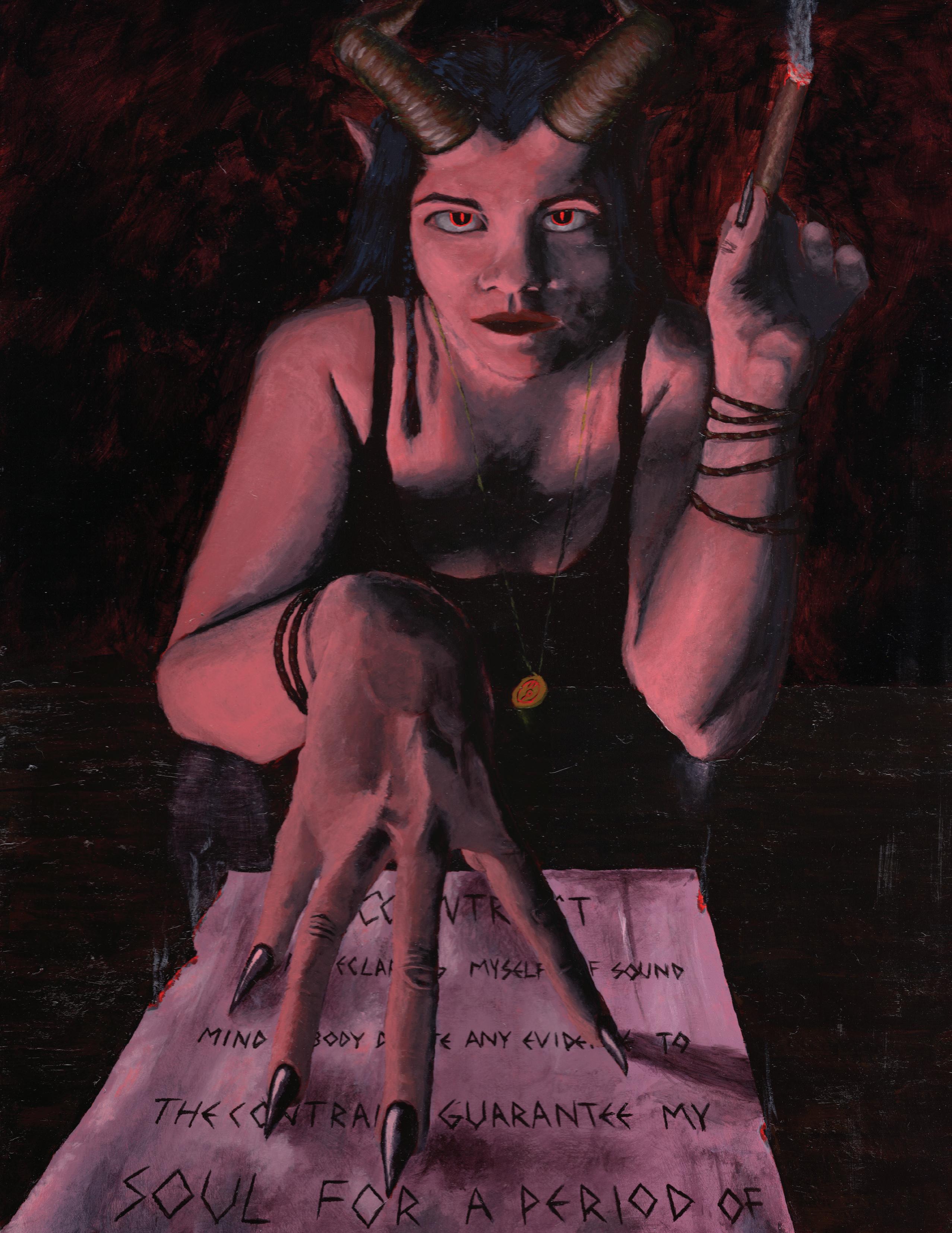

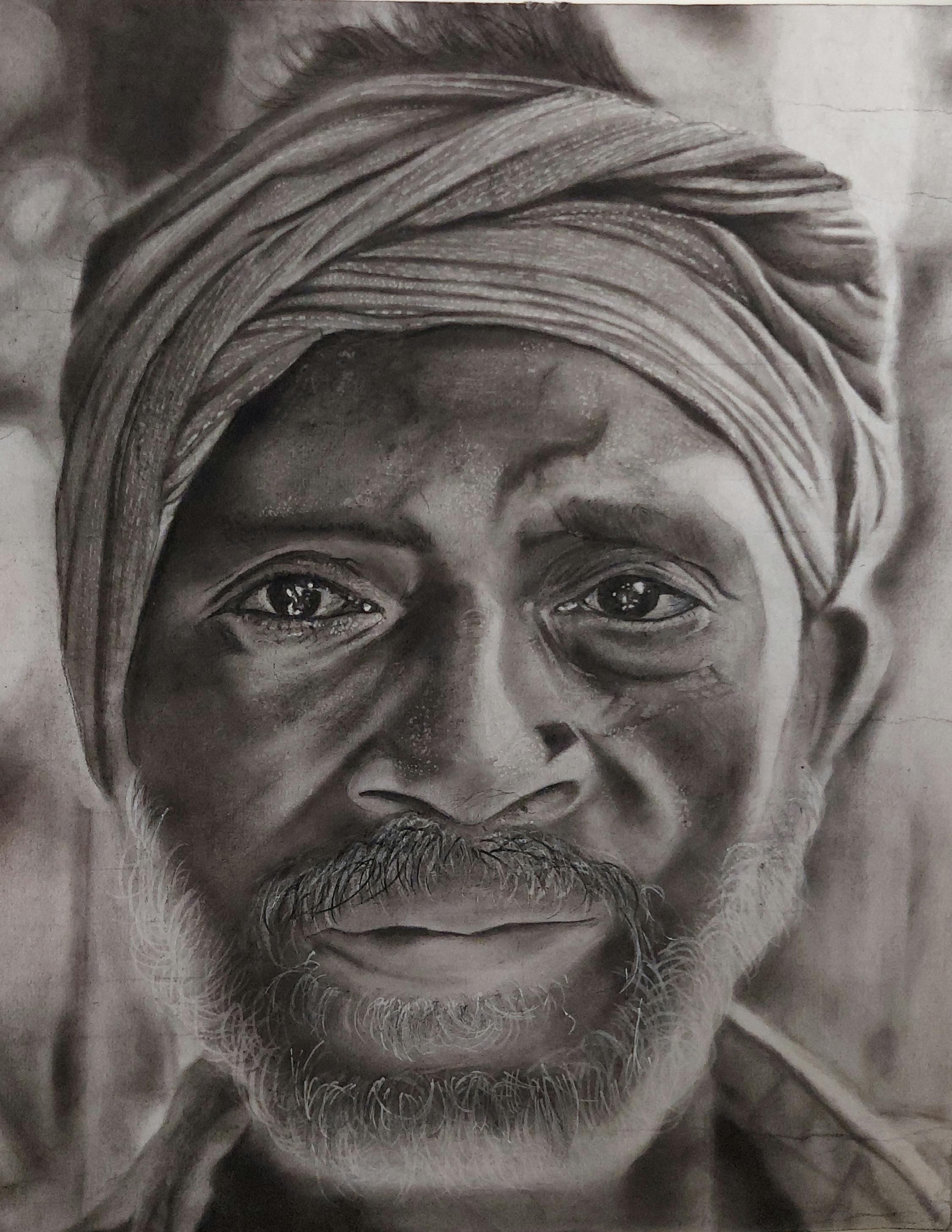

This journal is about showcasing and publishing the UW-Madison student body’s work, and frankly, the works contained within these pages are stupendous. We’ve got pottery; we’ve got School Committees for Interspecies Relationships; we’ve got experimental emoji-inclusive poetry. In sum: we’ve got it all. And the best part? It’s all student-made.

This entire journal is student-made from cover to cover. The cover itself? Student work. The layout? Student work. The blood, sweat, and stress-tears poured into this bad boy to meet the print deadline? Student work.

That’s not to say we didn’t have a little help. It would be remiss of me not to give a huge, ginormous, all-caps THANK YOU to, first and foremost, our contributors. Thank you for baring your hearts to us. Making any kind of art (literary or otherwise) is painful. Sharing it can hurt even more. Thank you for trusting us – without you, we are nothing.

My second all-caps THANK YOU is, of course, to my staff. Thank you for bearing with me as I navigate the role of Editor-in-Chief. Thank you for investing the time and work necessary to make this happen. Extra-special shoutout to you, Grace Zhang, you wonderful wonderful person, for taking on the role of Layout Editor. With zero prior experience, you stepped up to base, you swung, and you hit one glorious home-run.

My third all-caps THANK YOU goes to our PubCom Director, Katerina Stuopis, the PubCom Executive Team, and our Advisor, Robin Schmoldt. Thank you for your unwavering support and also for answering the millions of silly little questions I had along the way.

My final all-caps THANK YOU goes to YOU, dear reader. Whether you be Earthling or otherwise, it is Illumination.

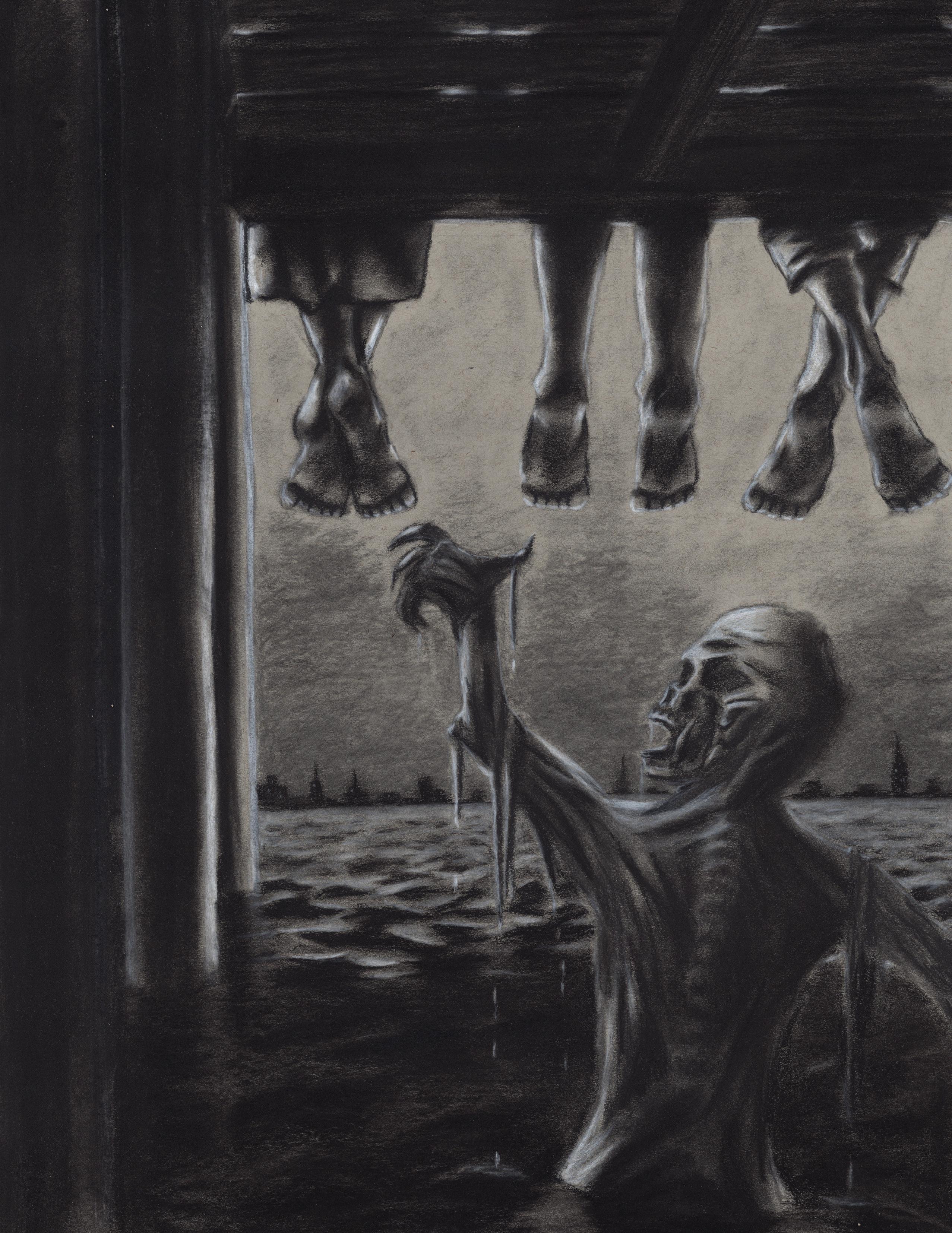

Beneath the Tent Taylor D’Andrea

*prize winners in purple

Singularity

When is it Time

Emily WesoloskiMy great grandmother lived to be 101, but my mom will tell you she really only hung on to make it to 100. I was thirteen years old when I attended her open-casket funeral.

Shortly after her 100th, she fell onto her living room floor and laid there for hours. She broke her hip and her favorite vase. My great uncle found her as he dropped off her groceries, and the family decided it was time to transition to the nursing home.

Her husband had built the house where she’d lived alone for as long as I knew her. She ran a beauty parlor out of the front room for 60 years. Its backyard was the river, and she’d sit at her perch by the kitchen’s massive window and point out the muskrats and deer and eagles to us. She’d watch us fish off the dock in summer. In rare moments, for July barbecues when my father and great uncle would help her down the rotting stairs, she’d join us for lunch next to her untamed rose bushes.

She never forgave the family for making her leave that behind. After a few months in the nursing home, she no longer pushed herself in her wheelchair.

When my grandma and mom were busy talking to nurses, she’d ask me — by my mother’s name — to take her down the hall. There was one window where you could still see the river. I’d push her there, and we’d silently watch the water flow by. I’d wonder where the wrinkled and formidable woman I grew up with went. The woman who loved lime vodka and always had a witty comment prepared. The woman who slept in blue curlers and cleaned her collection of costume jewelry weekly.

In that woman’s place was someone with weeping bedsores and unwashed, unstyled hair and used tissues stuffed up her sleeves. Someone small and quiet who eventually never wanted to leave her bed. The last time we saw her, she slept through the visit.

The night she died, my mom told us it’s a good thing. My great grandmother had outlived all of her friends, her husband, her sister, and one of her children. She was tired, and she’d made it so far.

When we went up to her casket in the stuffy, foreign church where descendants of her and her friends gathered, her hair was styled and her favorite pink lipstick had been applied. She wore the dress she had picked for this day seven years ago, and her eyes had been closed.

I stared at the butterfly. I nearly crushed it with my car as I attempted, then awkwardly re-attempted to parallel park. I didn’t know what to do — its wings were still perfect; it could’ve just been resting on the soggy blacktop. What if it wasn’t dead, and I’d kill it by touching it? Crouched, I searched for signs of movement. Two people passed by.

Nothing about it changed when I grazed its antennae. Its legs were curled in on themselves, and its thick, white-spotted body was still. It was the type of bug that would audibly crunch if you stepped on it. I never liked that sensation — it’s why I started trapping spiders instead of squishing them.

It had been raining the past two days — I was kidding myself by hoping the butterfly was still living. A monarch. I couldn’t leave it on the street like a McDonald’s wrapper. The body was furry, like if I stroked its back it’d feel like a cat. The wings were velvety with skinny black veins through the orange. It was something my great grandmother would have painted for me.

Trying to touch as little of the creature as I could, I pinched a wing. Once I picked it up though, I realized I had nowhere to go. I wasn’t going to bury it. Who buries a butterfly?

Another person walked by with their music so loud I could hear a guitar solo leaking from their headphones. They stared blankly ahead.

I had read a book about monarchs — the news said they were endangered. This little guy was supposed to be on its great, impossible migration to Mexico, where its grandfather would have been born. It was supposed to rest for the winter before making more caterpillars to start the cycle over again. Instead it ended up dead on a midwestern side street. In a neighbor’s lawn sat a broken couch that had been decaying for months. Another few feet down the road, a packet of barbeque sauce had exploded.

Without a more respectful resting place, I set the little monarch’s body into the grass and mud. I left it near flowers. It wouldn’t wake up, but I wanted it to be near something it might’ve liked. Its wings splayed out, flat in the center of a ring of Queen Anne’s lace like it was sunning itself. I hoped its little body wouldn’t blow back onto the street.

My grandma gave me her car for my 16th birthday. She drove us around in it for years, taking us on field trips in the summer. I loved that car. When she passed it along, she left everything in it for me. The towels to sit on when the dark leather got too hot in the summer. The emergency umbrellas. The koozies in the cupholders. And, in case of emergencies, a massive hunting knife remained in the center console. It was already open and ready because no one had taught me to re-sheath it. I stumbled over to him, passing it handle-first.

Do you know what you’re doing? I asked.

I have to.

I know, I told him, because I understood. It’d be cruel to let it suffer any longer. Thank you. He knew I’d never be able to do this myself.

I screamed as my brother tried to brake in time. We hit the deer still going 15 mph. That was the last time I’d ever let him drive my car. We pulled onto the gravel shoulder, and he got out. It’s still alive, he told me as he squinted through the darkness. Unconscious, but alive.

The doe was massive and shallowly heaving. I’d never seen one so close. Usually they were plastic toys in corn fields. Entire families of them would stand far out into the dusk. Why did this one cross the highway tonight? And why did it have to leave such a massive dent in my little red car? Her coat had empty, scarred patches in it, and her eyes were wide and dark but cloudy and old. She reminded me of our dog.

My dad taught us only conscious deer could close their eyes. They were like mom in that way — they slept with their eyes open and always knew what their babies were up to.

The knife, my brother shouted from the body. I need the car knife

With the precision of a kid who’s been hunting for years, he buried the knife into the atlas joint at the back of the doe’s head and wiggled it to sever the spinal column from the brain stem. It felt like there wasn’t enough blood involved. The head hit the ground. The eyes didn’t even flutter. They just kept staring.

Help me drag it off the road? He asked. Together we took its skinny legs and tugged. We left it near tall grasses, where no one could re-hit it before it was collected by, well, whoever took care of those things. Then my brother wiped the blade on the ground and closed it. Who knew if it’d be needed in an emergency again.

I apologized to the stiff little mouse as I nudged its body away from the path. It was flat in a way I couldn’t wrap my head around, it must’ve been dead for a while. There weren’t any ants crawling around it, no eyes in its sockets. Just the empty shell of a mouse, a delicate costume.

I was pushing it with a flimsy stick from off the trail, and it was an ugly sort of push. The body was frozen, curled into a little disc that kept shifting away from the stick. It took me at least a minute to get it into the foliage.

I wondered why a bird hadn’t gotten it yet. Part of me felt offended on behalf of the mouse. Was he not good enough for the birds? Did they find him lacking in nutrition? He was small . . . but food is food, isn’t it? I’d watched a hawk pick a baby bunny apart in my backyard when I was five, it wasn’t a pretty process. Why’d they let him go to waste?

I used the stick to cover him in leaves — the best I could do to give him a burial. This way, maybe he’d never have to worry about birds again.

A runner went by as I did this, glancing my way only to avoid me as they passed. I must have looked ridiculous, flinging leaves into a pile with a flimsy branch along the hiking path. I stepped back, and before I went on my way, I wondered if I moved this little mouse’s body so that no one would step on him, or so he wouldn’t get stepped on.

I’d also fractured my femur, so even if I had tried, I couldn’t have stood and saved myself. But I laid there in the water and stones thinking it was the end for me. I wished I hadn’t gone out alone, even though I’d hiked that trail a million times before. I wished I hadn’t spotted litter trapped in the weeds and let my curiosity get the better of me. I wished I was still 20 feet up on the structurally unsound wooden bridge that the DNR wardens or forest rangers or whoever was in charge of this place definitely had not checked recently.

Could I really blame the DNR though? The state has over 600 county parks, how often do they have the time to check every trail at every one of those? My brother wanted to work for the DNR at one point. He’s always loved to fish and hunt and be outdoors. That’s the exact reason he stopped wanting to work for them though — he didn’t want to be the one to take care of the land and animals, he just wanted to enjoy them.

I lay in the creek bed broken and alone. The water was gentle as it ran away with my hair, just barely whispering to me at ear-level. Under my back I could feel every terrible, raw stone I hit in my fall. I stared upwards, comparing the feeling to the sight of the grabbing, naked branches of the forest trees. I watched those branches for hours in the cool air.

Later, the emergency room doctors would explain to me how my head cracked open. Where the creek’s current hadn’t washed it, my hair was sticky with blood. They’d shaved some of it to staple everything back together near my crown, and that was what brought me to tears. I’d been growing my hair out for years, and it was finally long enough to pull back. As a little girl, I’d always wanted my hair to swish back and forth while I walked.

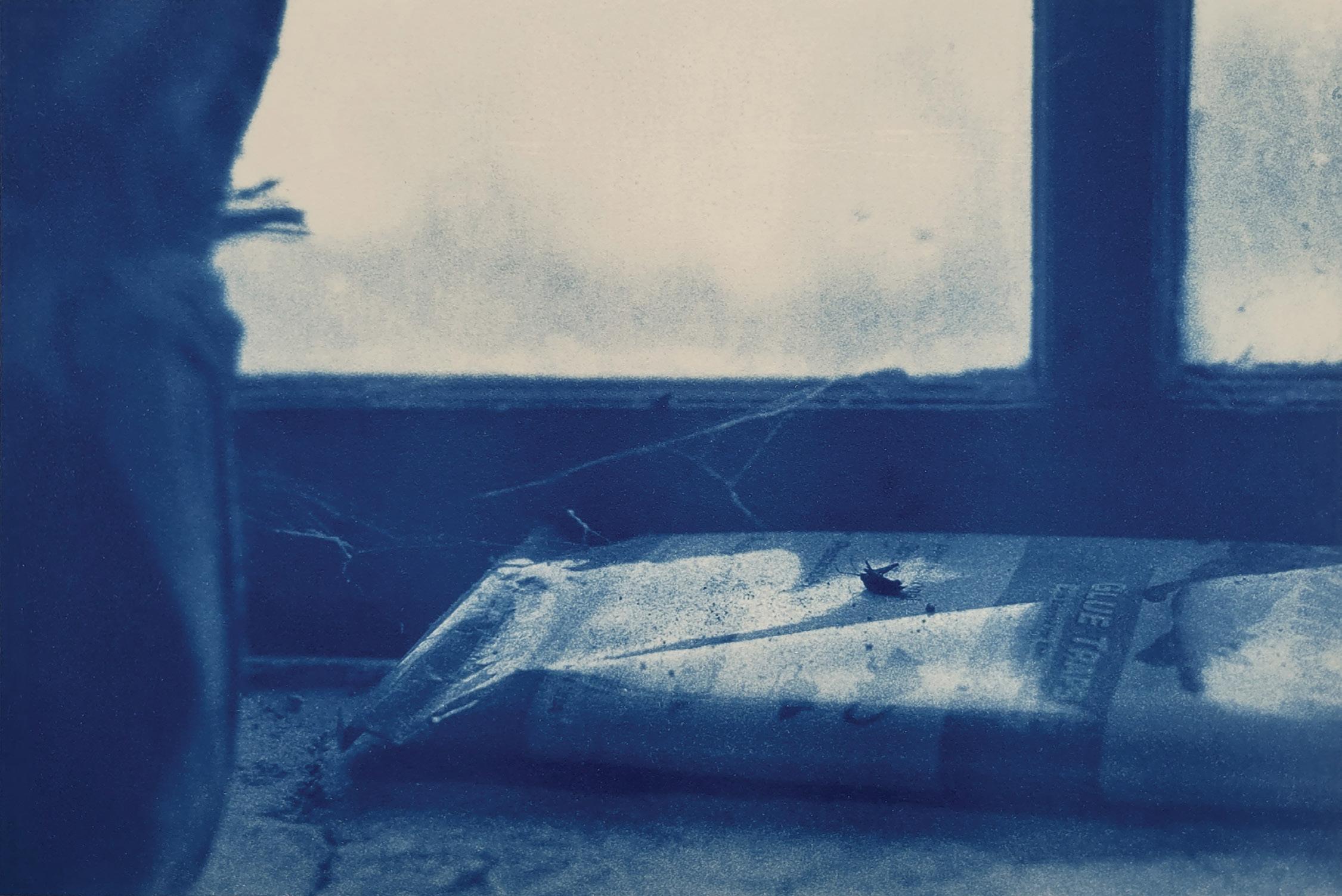

Really, I should’ve known better than to lean over a nearly empty riverbed while by myself during the hiking off-season. I’d just wanted to know what was glittering below. As soon as I recognized the Busch logo though, the timber gave way.

I think I was crying when the two elderly women found me. They were out for their weekly walk, gossiping about soon-to-be widows and old high school classmates. They almost walked right past, but the broken railings made them pause.

Oh my, we better call emergency services, one said.

She sure looks rough, I wonder if she’s awake, the other took out her phone and dialed. They chatted about me like I wasn’t there until a rescue arrived. When they moved my body, everything inside screamed.

Who do the angels go home to?

Do they stand in the windows of mortals, envious of the arm cradled beneath the baby’s head, fingertips grazing the condensation on the panes of glass?

They are envious of the fevered forehead resting on starched white sheets, drops of perspiration dabbed by a damp cloth, the weary body, its wet tears, wet mouth.

The grains of sand mirror the heavens, but the heavens cannot scald bare feet. They cannot harbor glass tumbled by the tide, scattering beer bottles and plastic dolls.

Nearing the sun, there may be heat, but there is no warmth. Angels cannot eat, but still hunger lingers.

Midnight Flora Stolzenburg

Off in a nameless town, with valueless people, someplacethere’s a circus

Notamovingcircus; they put down the pegs for the big tent years ago there are only five members to the circus and it’s funny people still come to watch

Maybe it’s because everyone loves the lion tamer sincewhodoesn’tchampionthestrongandfearless?

He’s an old little man with a big hat and a long rope and large jacket and a little nose He watches the lion as it stalks across the dirt; waiting, always waiting winning because everyone else is too afraid

And of course everyone loves the joker butwhodoesn’tadmiretheyoungandignorant?

He’s a lanky young boy with a big stupid hat and a sloppy grin He completes silly stunts and is covered with bruises we can’t see happy because at least everyone else is laughing

They also love the magician butwhodoesn’tappreciatetheskillfullydeceitful?

He’s a stout man with slender hands and shifty eyes and a small mouth He changes the laws of nature in front of their eyes disappointed in how willing they are to believe in what isn’t real

And what a wonderful ringmaster sincewhointhisworlddoesn’tlongforauthority?

He’s a tall man with a loud voice and a wide smile and small ears He leads the whole show; pretending he knows exactly what to expect relieved because no one has questioned the choices he has made

Then there’s the tightrope walker the stands are usually cleared by the time she comes on the stage alwayssavedforlast

She’s a pretty girl, tall and kind and knowing how to put one foot in front of the other, she never looks down, but she also never looks up She looks straight across the expanse to the other platform

If she gets there, they will clap for her if she falls, they will gasp The weight of the show is on her shoulders, the big lights beaming down on her face A few in the crowd yawn

She holds her breath don’tstop,don’tthink,don’tfeel One misstep and she collapses

And that is the most miraculous thing about the circus if the lion tamer loses his whip, he will be replaced if the joker forgets his tricks, he will be replaced if the magician doesn’t pull a rabbit out of his hat, he will be replaced if the ringmaster doesn’t capture the crowd, he will be replaced

But if the tightrope walker falls the act will be left out from the show it will be deemed too dangerous and no one will ever walk where she did

She cannot fall

They are, though, from a nameless town, with valueless people, someplacethe circus doesn’t matter a whole lot

In a few years, no one will remember them at all Some will come, buy their peanuts, laugh, stand up, and move away from the stands but the performers will stay, wait for another show

And though there may be performers after them, and after them, the circus, the Circus will go on.

en route to South Beloit

Completely unforgiving, the bug bite on my leg will not go away. Right above my knee—the spot I have always wanted a tattoo—it resumes, watching me stumble through the treks that I call My Life. Every two months, I scratch my bite so much that it bleeds and bleeds until I take a shower and stop picking at it. This fleeting feeling consumes my mind that I mean nothing to You. You are everything and I am nothing, but You wander so casually that I think I may be invisible to You. I tell You that I love You, I miss You, I think that my existence needs You. You say it back with a carefree breeze and we do not speak again for weeks. I long to see You so much that my legs become jittery. When returning, it is an Love You, maybe someday. After three weeks of forgetting to text You and realizing my bug bite did not disappear, my realization dawned: I am Your bug bite on Your leg that will never go away if You asked.

The residue of a dream.

Kai LiAfter Xi Chuan

Li Bo listened to the heaving of the river. Beside his feet, a pot of wine & the swollen wood of a quiet boat.

In old dreams I imagine he did not flail when he drowned. But today I reject old dreams and old myths. (What the fuck do poets know? They have never drowned!)

Instead: he rises up to touch the moon. Stupidly, his feet fail, and Li Bo falls into the river, finding his son’s eyes among the sturgeons swimming by in the Yangzi…

The residue of a dream in my garbage bin, in which a mangled fish looks at me.

I close the lid.

Strangely, it reminds me of a scene from my childhood: What kind of fish is this? I asked my father by the lapping edge of the lake. Largemouth bass and walleye, he said. His scalp gleamed.

I need to pee, I said.

Pee in the water, he said.

Pee where the fish don’t swim and hurry before the storm washes in and I pee in the wind, pee on myself, I thought.

We were poor. We sometimes caught fish ourselves, the sky raining and thundering. When we brought them home, he would cut their bellies open and I, hiding from behind the wall, would see a mass of color in his palm. I never dared look in the garbage bin.

And I thought:

Father always had the answer. He knew the fish better than his father—his father’s father’s father’s father, perhaps.

A boy like me must have stood on that ledge in that manner a thousand years ago, pissing into the lake and the fish. Mother told me: father, when he was a boy, fell into the lake near his home and saw catfish so big, eyes so piercing, that he never forgot them.

i)

My mother is a cold person.

I know she loves me.

I know she does.

I was what, four or five, and as always, very talkative. The kindergarten teacher hated that about me.

- “Denise, be quiet ��!”

That day, teacher Kelly had had enough. She put tape over my mouth: “And you don’t take it off until you get home!”

As an exemplary student, I obeyed. I walked home.

(My town doesn’t measure distances by blocks or time. It is estimated from house to house) I arrived, and immediately, my mother ripped the tape from my mouth.

- “What happened?”

And once again, I spoke.

My mother grabbed my arm, and we got in the red Ford. She left after passing a few houses until we got to Kelly’s.

I was still crying.

I did something wrong: talking.

I deserved the duct tape.

- “And next time, Kelly, you come shut me up before you tape Denise.” I didn’t finish kindergarten...

My bean �� didn’t germinate either. It must be life.

ii)

Lupita ran to the door of our house with my niece in her arms, both bathed in blood. We are Jehovah’s Witnesses.

This is settled as a family. They arrived, and in the twin beds we shared before him, like islands, the two families discussed how and why to help the young couple.

Willy was crying - how ironic!

Exasperated, Betty, his sister, launched herself at Lupita. But But But

Before crossing the aisle, my mother stopped her hands and pulled her out into the street.

- “In my house and in front of me, NO!

iii)

“Mom, Jose left”

- “No way. That’s life. And it’s very nice.”

- Mother: “Don’t be a coward! Pay the rent.”

iv)

- “You have your house and your room! Leave that school and learn that when they love you, it shows, and when they don’t... it shows even more! Go home!”

v)

My mother worked all day long in a hairdresser’s shop on Noche Triste Street: to $10 a cut, come on in! Come on in! Come on in!

Tired, she would come in and open a Coke. Then we would watch the news on Channel 44 together.

“Poor woman.”

“Poor woman.”

“Poor woman” Marisela.

I don’t remember if it was me or my mother saying it as we watched Marisela, again, as the focus of attention.

(((“I broke Rubi.” She was found in the pig sties))))

“Poor woman”

“Poor woman”

“Poor woman” Marisela

vi)

I have always been a bad feminist.

My Mother

Never

She didn’t have to read Beauvoir to know her gender. She didn’t have to study Butler to understand systemic violence.

She never heard of Marx, but she understood the importance of surplus value. What does she care who Bauman is if, at the age of 16, she understood that love is liquid? The first time that my father was unfaithful. The first of many. All of them, to this day, she forgives.

- “He’s your father, I did it for you. I don’t want you to grow up not knowing who your father is.”

I am that terrible feminist. I was raised, guarded, protected, trained, loved, accepted... by one who is good.

Start your car. Drive. Find something to do—make sure it’s something worthwhile. Let’s go over our options: walk in an empty mall food court, loiter in a nursery, take a lap around the lake on your bike, or end up smoking in the same park district parking lot, the one next to the old public swing set, the one you always say you won’t go to. None of this seems appealing. I know. Do it anyway. Repetition is better than resigning to do nothing. You’ll regret wasting a weekend later.

Wasting time. Get good at it. Here, there’s tons of time to kill. A lack of urgency slows life down. There is sanctuary in sleep. Lay in bed until noon and nap again at four. Watch the sun rise and set through plastic blinds as you waste the day away, wrapped in white bed sheets. Examine the topography of the sheets, the mountains, the valleys you’re missing here in the Great Plains. Dream up plots worthy of the big screen, but never actually go to the movies. The popcorn’s overpriced and soon you’ll be able to predict the resolution to each story. Don’t do that to yourself. Your life, like the movies, comes with an ending that’s predetermined. Save yourself the hurt of getting good at guessing.

Time to run errands. Mow the lawn, clean the house, and trim the hedges. These are the perks of being a homeowner. Now, go grocery shopping. Pick up milk. Remember that your brother prefers Oat and your mother likes Almond. Resist the urge to crash your car—full of plant milk—into a roundabout. Be a good person. Good people don’t crash their cars on purpose. Take it easy, it’s the Midwest.

Abide by tradition. Value hard work. Do what others did before you and figure out how to have a good time while doing it. There are no high expectations, just fixed occupations—teaching at the same high school you went to, or finding an office space in the “downtown” that isn’t really a city. Follow the path of least resistance. Don’t think too hard. Be happy.

No, yeah, this makes sense. I’m happy. We’re all happy. How could you not be happy? This is the dream. The American one. Dry in comparison to the ones you conjure up in bed, but the sort of life, safe secure suburbia, your extended family seems to appreciate.

Watch your parents go to wine nights, PTA meetings, and bake sales. Help your mother buy a casserole dish. Question when they fully assimilated. Are they happy? Of course, they are. They lost everything, worked for everything, and wished everything upon you. They made it—successfully immigrated from a place with no street signs, no sidewalks, to a place with a stringent homeowner’s association. Your house has a patio, a lawn. Your school has a high graduation rate. There’s a strong chance you’ll go to college. This was their dream.

In the springtime, let the temperature shifts shock you back to life. First seventy, then thirty. Hot then cold. Dress in layers. Go to carnivals and concerts and kiss under lamp posts. Pretend that the streetlights are thousands of tiny moons. Go “up north,” to the lake. See the real moon. See more than just five stars. Fall in love. This isn’t all that bad.

Go on dates at drive-ins. Make sure it’s not with a boy from high school, or else everyone will know. Remember, here, we have no secrets. Play it safe. Stick to anecdotes and pleasantries: Howareya? Boy, it sure is nippy out. Catchyalater! Call that a conversation. Get a summer job: At the YWCA, the old Dairy Queen, or a waitress at the Olive Garden. Keep yourself busy. Get interested, but never invested. This goes for both boys and jobs. Divest all and any desire. Keep a level head.

Winter chills will freeze both the Earth and your freedom. Try not to panic. Focus on projects (cleaning the basement) and papers (college applications) and promises (college applications out of state).

Buy so many candles. The sun will start setting at a quarter before four. Romanticize working, by dim candlelight, under the cover of darkness. Pray, desperately, you won’t lose yourself to it.

Try to leave. Go to college. End up closer to home than you wanted. Admit you’re from the suburbs when peers ask. They’ll all guess it anyway. Get cultured. Stop pronouncing “milk” as “melk” and “Bagel as “Bag-el.” Sample success. Experience your first ever free flight, a conference. Consider that you’re actually capable of something, being someone—that’s new. Try not to get hooked on the taste, or you’ll be left forever chasing. Come back in Summers and to argue politics at Thanksgiving dinners. This will become your new routine.

Shove personal ambitions into bottles and break them under bridges. Smash plates and heartbreak and any hope for opportunity. Make sure to bring garbage bags and clean up all the broken pieces. Dance with doubt. Get married. Don’t make a mess or wallow for too long.

Yeah no, I’m not okay. Nobody is. How can they be? This is the dream.

[Stop. You’re privileged, comfortable, sheltered, and only just learning to become more self-aware. You don’t know enough. Try leaving, actually leaving. Not to college, but the real world. Try leaving, we all dare you. You’ll last ten minutes. You’ll finally crash the car. You’ll just crash and burn. You’re not smart enough…Don’t dwell on it. Just come home. Darling, come home. Be comfortable. Be content. Take up that job at your hold high school. Marry that boy from your old high school. Live within driving distance of your old high school.]

Get a license to kill. Go to a shooting range. Practice. Go daily. Get good. Tell no one. Never buy a gun— we live in the part of the Midwest that hates those. For the first time, feel powerful. Sometimes, when you wake up to the sound of singing birds, your restlessness will finally subside. You’ll be at peace. Other times, you’ll wish you had that gun to shoot the damn things. Relax. Both reactions are only temporary.

Read stories of peers who “made it.” The girl from high school who actually ended up on Broadway. The divorced neighbor who’s now big in Silicon Valley. Two people we all silently seem to admire but criticize openly—she always thought she was so high brow; he was never a good family man— in conversation. Consider how your definition of success, betrayal, is synonymous with a change of location. Tell yourself they’re not happy. How can they be? Their dreams come at the price of leaving home. This is your home. You owe it to home, to community, to family, to stay. Here, we all owe each other lots of things.

Ownness: Be a good neighbor. Shovel their driveway, then get driven to school. Help one another through blackouts and thunderstorms and injury. Nanny their children and rush them to the basement when the tornado sirens blare. Have those children cheer for you at graduation or anywhere. Adore them. Be adored. You’ll never find this kind of love anywhere else. Savor it.

In spring, a robin builds a nest and lays tiny blue eggs at your windowpane. This is your new project. Get attached. You worry a hawk will break these eggs. Go to Home Depot, buy chicken wire, and encase the nest in it. Cut a hole big enough for a mother bird, but not a hawk. Line the hole with fabric so the mother stays safe. Spent an entire afternoon bent backwards out your bedroom window. Get called crazy by your sisters, stupid by your mother.

The mother bird never returns. You’ve confused her. Remove your makeshift cage and hope she changes her mind. She doesn’t. You stare at the eggs each morning, and feel responsible for their abandonment. For the first time in your life, allow your heart to truly break.

Somehow, the eggs still hatch. Hearing the babies’ cries, the mother returns. Feel joy, pure unadulterated joy. Feel wonder. Get hooked. Find it in car rides and Orion’s Belt. Taste it in cups of tea and at family dinners served in new casserole dishes. Learn to get excited. Look for joy because you need it to persist. Negate novelty, but don’t settle for simplicity.

Become a traveler in your own right. Explore every coffee shop, strip mall, and state park. There’s more— here—in the Midwest than what originally meets the eye. Stop at every strange road-side attraction: World’s Largest Ear of Corn, the rollercoaster a man made in his backyard, small state parks you’ve never heard of. Never ask for directions and always take the long way home. Walk—everywhere. Master footpaths missing from maps. Find harbors hidden in prairies. Trek up knolls with picnic baskets, siblings, and telescopes. Fight off mosquitos with old badminton rackets. Light sparklers with old candles and throw them down the driveway. Create your own shooting stars.

Turn shallow rivers into waterparks. Build tire swings and tree forts. Sneak out with friends to jump into ravines. Hit one hundred on the highway. Stand on the center console to stick your upper body out the sunroof. Scream. Scream over and over— just for the sake of it. Become a protector of baby birds and ladybugs. For once, the story starts to seem more interesting than the ending seems worrisome. This is life, and it’s still far from perfect—you see it now.

Spend a night out on the docks, stay up to watch the sunrise, and skinny dip in the lake afterwards. Score the skin of a friend with an ink dipped sewing needle in a dirty dorm bathroom, twin tattoos drawn out on a Tuesday. Marvel at the marks you’ve made. The mark you still can make. Carefully pour one bottle of ambition into a large wine glass. Drink it. Get too drunk. Share. Realize everyone else smashes bottles too. Of course, they do. So, smash some. Save some. Share some. Survive.

Find book shops and thrift stores and new places to park the car. Get up early. Stay up late. Stretch time far and wide. Drive into the city and see yourself reflected in the window of every skyscraper. Go to the East Coast then Europe, for the Summer, discover you feel homesick. Yes, you’re moving forward.

Yeah no, for sure, you learn—I learn—to be an odd sort of happy. Anyone else here would too. After all, this can be the dream.

Past Cloud Nine

Past Cloud Nine

North Star

Sarah JasimThe place where you are is scrubbed clean and polished. They build bridges to spite the water, and skip rocks to spite the guilt. You spend your time drinking melted snow and brushing off infield dirt. I spent my first few months of college spreading thin, becoming paper, radio waves, paste spread over a collage of old receipts, book pages, letters, pressed leaves, all mod podged to a slab of cardboard in the shape of my body when I’m sleeping.

My head was far from Wisconsin, while the rest of me was here, hiding in stairwells, trying to learn how to breathe in the dark, but I knew then and I know now that there was a light on. They build lighthouses to spite the stars, and stars die to spite the ships.

You have the other half of me, and I’m not sure when I’ll finally be strung together, four eyes becoming two, two mouths becoming one, sitting in the pitch-black, breathing.

My mother holds me, holds me, holds me, Until only a network of her voice teathers me. She holds my cheeks tight–In the palm of her hand… OW

Why are you crying I DON’T KNOW i don’t know

How can you know me entirely While I only know you as a part of me? i don’t know

I have never felt more myself than when I look at you Lift your chin up, I face myself in the mirror

My mom cuts my hair, only ever in one straight line–everything needs to be exactly as it should

Anticipation, concern, frustration, failure And we couldn’t be more proud of you Everything I do is for you

And I think that when I die I will crawl back into my mother

He was never invited inside. He stands across from me, eyes glimmering with joy. Hello again, he says. We haven’t spoken in a while. It was completely intentional on my part; he was not supposed to return. Do you still think about me? He innocently asks. “I’m trying not to,” I grip my bathroom counter. I know what he is here to talk about; I want him to leave. But he stands proudly across from me, grinning at my discomfort. I’ve been happy, he announces. So happy that I fear my teeth may break from smiling too much. I walked around Washington Square yesterday, only feeling bliss. “You moved there, after all,” I stated—because it was not a question anymore. It had always been his dream. When we were younger, he was too scared to say the dream out loud. I did. You can join me, you know. My hands tremble at this thought. It never had to be this difficult. “I’m terrified,” I respond. “It would change everything.” It doesn’t have to; you don’t have to tell anyone. No. “There are people I love. People I would owe an explanation.” If they love you back, they’ll support you. They’ll understand. “It’s not that simple.” He knows I am getting frustrated; he grins at it. You’ve always wanted to be around me. It was obvious from a young age. “You knew back then?” Of course, I did. You were obsessed with loose shirts and long shorts. The only thing that made you different than me was your long hair. “And the girl parts.” And the girl parts, I guess. But does your body define who you are or do you? “I don’t know anymore.” 50 years from now, our bodies will sag the same way. He approaches but does not touch. When your body decays, no one will know who you were born as. I look him dead in the eyes. “Will you go to Heaven or Hell, do you suppose?” I don’t believe in either. But if a priest were to tell me, it would probably be down below. A pause. Is that what you’re afraid of? “I don’t know.” Oh, he can drive me crazy. “I don’t know anything, these days.” My voice is getting louder. “You quite bother me, actually. You show up, uninvited by the way, and you tell me all of the things that will make me feel better.” He looks surprised. Calm, yet surprised. “How do you know it will make me better? You can’t promise acceptance, you can’t guarantee a happy life, and I wish I had never met you in the first place.”

That’s the thing, he responds. You created me in the first place.

Guardian

Guardian

My father never liked me very much, but he carried my second grade photo in his wallet until he died. He blamed himself, really — someone convinced him he wouldn’t truly be alive until he had a project to pour himself into, and where he grew up, a child could just be molded like clay until it was ready to be kilned. But when the oven was 80’s America and the lump which needed to be sculpted was a little brown thing with a full head of hair, he looked down at his shaky hands all those years ago and decided the whole thing was doomed from the start. Nevertheless, he saw his job through. My father did not like any of it, but you couldn’t say he wasn’t a father.

My father decided I was going to be a whore, and then he decided I was going to be the one out of the two of us to have everything. Before he made these diagnoses, however, he thought the best course of action was to throw darts at a landing board and hope they stuck. He dragged himself out of bed at five every morning and shuttled every other New Yorker to and fro until nine, then came home and reviewed my day. My mother had instructions: I would learn this mathematical concept from her two years before I would be taught it in school, I would run laps with our landlady’s boy until I could at least do one to his two. He came home and monitored my progress, either beating me, yelling, or petting my head with some affection. He was mild in whatever reaction he chose, so I grew to hate his love and take comfort in his rage.

Though he saw to this hamster wheel of my early life, initially, my father did not presume I was going to be much of anything. He could explain the deepest intricacies of physics to laymen such as himself, but this mental capacity did not extend to basic science for his eight year old daughter. I was not a child intellectual by any means, nor was I clever. I did not once fan the flames of his miniscule hope that I would be a trailblazing Bengali-American Olympic athlete. The most my father could say for me to his friends was that I was “inventive”, but he

knew that all children were inventive, so my hours of conversations with dolls were not of particular interest to him.

He came to the conclusion that I would be a whore who had everything in seventh grade. It was not the typical fatherly introduction to a daughter’s burgeoning sexuality — there was no boy to chase out of my room one night when he came home early as a surprise. I was actually deemed quite ugly and unlikeable by the Upper-East K-12 private school I had squeezed into through my dad’s carefully constructed repertoire with a wealthy white taxi passenger. No, my father ascertained the facts of my future in a singular instance, a speck of time significant enough to him to change the dynamics of our relationship forever. In eighth grade, he stumbled upon a crumpled up paper with glittery pen marks while deep-cleaning my room after I’d gotten the flu. A lesbian love story. It was a travesty, he cried out loud, and it was going to get me an STD or a sexchange operation. Why was my depraved, atheistic English writing about sex and love as intricate as his own dead father’s Bangla poems about butter and the boy Krishna?

In high school, the years that poor brown man had spent slugging me through whatever task he could scrounge up began paying off. I was wiry and lean, running sub seven minute miles to make cross country varsity and copy-editing for our school paper. By that point, a good portion of my classmates realized there were benefits to be found in feigning disdain for racism, so I even made some friends to go to the piers and smoke with. I hauled my ass like he always told me to, going from thing to thing as if that were going to prove to anyone that I existed in a meaningful way.

I no longer spoke to my father at that point, and after a couple of obligatory attempts to figure out why, the arrangement suited him fine so long as I continued to do well academically and not bring any female friends to the house. Only once or twice, I caught

him looking at me with shiny eyes, before turning away. People tell me there must have been times I hadn’t noticed, that he had been reaching for me all along and had no capacity to admit it. I know this to be untrue. I never stopped looking for him.

In tenth grade, I made the mistake of going to our school’s homecoming game. A benchwarmer for the football team was my good friend, or as good of a friend a girl like me could have, and there was a chance he was going to get some field action. I had a whole group of friends there with me, one of them even vaguely Hispanic amongst all that snow. It was of no consequence. Three of the football players decided they’d seen enough of me in the couple of minutes I spent offsides talking with my friend, so they called me a few names and made a few threats which I remember better than their faces. My friend said to ignore them and not make a fuss. I agreed. For that, I was rewarded with an accidental shove into a barbed wire fence as players excitedly filed out of the field after we won the game. My lip split open and my face got scraped, which was worrisome but not more so than what could happen to their team if I had a different description to my friend’s in describing the incident to the athletic director. I didn’t, and from that point on, I also didn’t have much of a friend.

My settled-upon silence with my father broke out into gunpowder smoke those months after I got beat up, as I stopped going to copy-editing meetings and exchanged running in circles around a track for walking in circles around the Manhattan side of Central Park. I was strong enough by now, and he was worn enough by wear and tear, that he could not beat me. So together we danced around the verbal ring like skittish fifteen-year-old boys at their first boxing practice, landing whichever punches hit without heed of the ones which would invariably land on us. I disgraced him as faint of heart and weak in the mind, undone by singular struggles incomparable to the ones he faced when he first came to this country. He dismayed me as the judge, jury, and executioner of my life instead of as what I’d wanted him to be, a lighthouse with which I could guide my boat to harbor. I was bipolar and he was sociopathic; the two of us were neither of these things. Eventually, the horse we beat became a

carcass. My father threw his hands up and amended our earlier contract, leaving me alone so long as I didn’t bring any female friends to the house.

I was rejected from most of the colleges I applied to as a senior, even though I did wind up picking some of the pieces I had dropped two years prior. I was not wanted by the crimson-jawed shark my father had always hoped private school would feed me through, but CUNY ended up accepting me into one of their dorms for next to nothing. He paid the difference, and thus his eighteen-year stint finished the way he’d always criticized Americans for supposedly doing. A child is assembled, then shipped off to the business of wandering this world.

I graduated CUNY with a 2.7 GPA and a job immediately out of college. I did just fine, truly speaking — once in a while, I even meet up with an old drinking buddy or fellow Promethean writer. My father called me once a month; a year into college I started answering; two years into college I offered to send tri-yearly paychecks from my work-study so he and my mother could have a bit more for retirement. He said he didn’t want anything from me until there was something worth taking, leading me to believe he never stopped holding out hope I would break through the industry. In one of our last conversations, I asked him if he ever read anything I published. He replied that he hadn’t, then asked me if I’d embraced the sick desires which he discovered I harbored all those years ago. I replied I hadn’t.

My father thought I was going to be a whore, and he thought I was going to be the one to have everything. I met him in the middle with a palm outstretched and full of nothing, which was really more disappointing to him than any other possible outcome of my existence. When he died of a stroke a year after I graduated college, I heard from my mother that he believed it was going to be the catalyst of my true beginnings. Now, he promised in the fanciful prose of British-taught Indian English, she will be free to fall down the path of incorrigible greatness. I met someone two months after his cremation.

I never liked my father very much, but I’ve carried his only schoolboy photo in my wallet since he died.

Mother, you will hear my Two Arms and Two Legs when I jump off this rooftop. Two Arms, Two Legs I gotta be grateful for the pieces I’m provided, not scream and shout because I don’t know how to solve the puzzle. Clap with these arms, lay them facing the sun to forget past scars, and feel the guilt in mixing your hands, praying for more. I’m not religious, but I am constantly asking for an existential force to give me an answer because I am never right.

I made my legs selfishly mine and made walking a form of meditation. My knees cry out with clicking air bubbles when I crouch because they need to remind me of my dwindling of my faith. I am twenty, having further than fifty knees.

Two Arms, Two Legs can’t complain about that either, because guess what I still have:

Leaning over the kitchen sink with my elbows on the linoleum, I twist and tear at the stubborn peach, my eyes on the myth that inhabits the yard.

After the record-breaking storm, my mother found a lightning-loved tree. Scattered are the shards of jagged bark; The similarity in our marks is clear to me.

My brother returns like a full moon, his body cleansed by the bone-white walls. He cried over the scheduled plates of food, too tired to fight the leaning.

I saw a blue jay today.

I put some seed out on the windowsill earlier, but I didn’t think I’d see anything,

Mhm,

Mhm, …

I sat near the window for a while, watching it pick at the food,

Mhm, It didn’t notice me. even when I pressed my palm against the glass.

I spoke to the cardinal, and it sifted and sifted through the seed as I poured out my thoughts...

...and for a second. For a second: I thought it was listening. It tilted its beak and peered through the glass,

And I waited for some sort of “Greeting!”

Some sort of response to let me know that it was there with me,

Mhm,

Mhm, But.

“It was only looking at itself.

…

It left as soon as it came,

And here I was: Sitting at the window looking at these empty seed shells! And the wind—oh the wind. It picked them up and away as if they were never there.

It was a lonely sight.

I wonder if it knew who put them there,

Mhm,

Mhm.

I wonder if it even cared. I did. The seed. I put it there!

I mean, I wasn’t expecting the bird to give me a formal courtesy of gratitude, you know?

But it didn’t. even. acknowledge me. It just took what it wanted and left.

I don’t think that it meant to leave me behind, but I doubt that it would have stayed if it were ever - truly - listening…

Maybe the cardinal only saw what it wanted to see, transparent glass into another world, unbothered by a person trying to connect!

Maybe… a few seeds and a glass pane is all it’ll ever want from me. I mean. Can I blame it?

Surely, I don’t need to talk to a bird through a glass pane…

“Do we have any more birdseed?”

with Buttons

NecklaceIseult and Anita returned with the promised water, passing a bottle each to the rest of their group. The four of them sat near the door on the cold stone floor and inspected their progress after two hours of work—an optimistic dent. What was a mound of cutlery, doming about five feet tall and three times as wide, had shrunk to half that with baby piles of various volumes around the room. Sophia, a girl with rings that surely signaled a magical heritage, was the first to get up from their reprieve and continue sorting the chopsticks.

The School Committee for Interspecies Relationships, SCIR, needed a new project and Anita took charge of getting them this assignment. Dealing with the horde of a dragon was a privilege and a resume-building honor. Anita was vying for president in her senior year. If this got good feedback to Mr. Nancy, Anita could get a glowing recommendation and Iseult would be on the fast track for vice president. On that basis alone, she was optimistic about this assignment.

When they arrived as a group of thirty for a day of volunteering, Iseult felt a bit more uncertain. The dragon they were helping had read Marie Kondo’s “The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up” and decided he wanted to de-clutter his horde. His goal was to get rid of six tons of stuff over the course of six hours. He had explained this close to her face, his long neck extending and Iseult tried not to let him see her flinch as she caught a whiff of his vile breath that reeked of burned hair. Anita, Iseult, and three others were assigned to the cutlery room.

Anita elbowed her friend before gesturing toward Sophia, the girl was kneeling at her pile and fluttering her hands in an awkward motion. Iseult smirked. She didn’t know why. It was just something the two girls did. Anita would point at someone and they both would laugh like it was some inside joke. To her right, Vinny belched.

“Ugh, gross!” Iseult teased. Vinny smirked.

“Excuse me,” He said, twisting the cap back on his bottle and rubbing his hand on his handsome chin. He then scrunched the bottle under his armpit and held his hands out delicately to both of his friends.“Feel my hands.” Iseult pressed them between her palms.

“Chilly!” She remarked. Whatever small talk he would have rambled disappeared as a cacophony roused their attention to the back of the room. Sophia had stood, kicking the pile of sticks causing the ruckus. She did so with a reason as she looked speechlessly at the opposing wall. A man Iseult didn’t know was there, looking equally surprised to see them. He wore all-black tactical gear with a matching ski mask. He glanced at each of them before dashing the door. Vinny was the first to react, blocking his way.

“Hey man, what’s the rush?” Vinny puffed his chest and flexed his arms as he crossed them. Iseult would have rolled her eyes had she not been so frightened. She slowly stood and, in her periphery, saw Anita do the same.

“Look man, I don’t mean any trouble. Just let me through.” The stranger spoke in a grave tone that seemed unnatural and forced. Vinny stared at him suspiciously, not moving an inch. The man tried again, this time sidestepping and moving closer to the door. Vinny blocked his way again, the two of them now in punching range, Iseult thought. Neither of them appeared to be armed in any other capacity but the stranger’s outfit did not assure her of this assumption. Vinny must have thought the same thing because when the stranger reached for his pocket, Vinny went for the tackle, pinning him to the ground almost effortlessly. Screams erupted from everyone.

“What are you doing?” Anita yelled at the same time Iseult shouted “He’s got a gun!” At the same time Sophia screamed nonsense while Vinny screamed in the way you do when you wrestle for

school but have never taken down a real opponent and the man screamed “Cut it out man, stop it! Let me go! Hey!”

The noise stopped when Vinny tore the mask off of the man’s head, wrenching it backward and back down.

“Max?” Sophia asked. The man was silent, shrinking into himself. Iseult turned to Sophia.

“You know him?”

“Yeah, he’s my cousin.” She came closer to confirm and nodded. His hair was blonde and pinned into a messy low bun. His face was scarred around his right cheekbones. It was also scrunched up tight like a child who had smelled something foul. Probably in part due to Vinny sitting on his back. “What are you doing? Why are you dressed like that?” she asked in her gentle, lilting voice. He remained silent. “Vincent, please get off of him.” She requested and the taller boy complied. Max groaned and stretched as he moved to sit on the floor.

“Hands where we can see them,” Vinny demanded. Max complied.

“Max.” Sophia tried again.

“I came to steal a spoon,” He said with his palms by his face and chin defiantly pointed up.

“What?” Anita asked.

“I came to steal a spoon,” He repeated.

“Tell me why,” His cousin demanded. Iseult glanced at the other girl. Her tone was harder than she had ever heard it before. In response, he sighed, closed his eyes, and complied. He told them about a magical ladle that was a precious heirloom. He told them that his mother’s grandmother was the last to own it before it was lost in a bet to the dragon here. His mother told him that the ladle held a magic healing power that would cause the user to instill a healing intention into their brew. It could reduce fevers, induce sleep, clear out sinuses, relieve pain, and more. He heard that the dragon was getting rid of stuff. Max wanted to sneak in and take it back and gift it as a surprise to his mother as

an apology for getting caught hotboxing her car.

Sophia nodded. “That seems fair. Have you located it?”

“No, I just vised in. I didn’t expect anyone else to be here.”

“Hold on, what? You are just accepting that?” Anita turned to Sophia.

“Yeah? The dragon is getting rid of it anyway. Max is doing a favor.”

“No,” Anita disagreed. “If it was a favor, he could have come and asked and wouldn’t be sneaking around or wearing that fugly getup. This is trespassing and attempted theft. Vinny?” She expected him to back her up.

“I don’t know, this is kinda messy, maybe we should get Mr. Nancy. Doesn’t he have a minor in ethics? He’ll know what–”

“We can’t tell Nancy,” Iseult interjected. “He’s a teacher. It’s not his job to be ethical. It’s his job to follow the law. Anita is right. Legally, Max is in the wrong even if ethically there may be a gray area.”

“So what do we do?” Vinny asked.

“I believe ethically he is in the right. It is our civic responsibility to do the right thing which translates to the ethical thing. The dragon won’t know it is gone and is getting rid of it anyway. If there is no harm caused, Max is not ethically wrong and therefore ethically correct.” Iseult thought a lot about stealing in her free time. She also spent a lot of time at various big chain stores shoving nail polish into her big jacket pockets. Still, the logic of Sophie’s statement was not up to par.

“That’s not how it works,” Iseult countered. “Just because nobody is getting hurt, and even if there is no deficit to make the action wrong, that doesn’t make him ethically correct.”

“Additionally, our civic responsibility is to follow the laws, not make our own laws based on the situation. If everyone did that, it would be chaos. Lawmakers are responsible for making laws that align

with ethics. It is not our job to debate ethics either way!” Anita added. Iseult didn’t invite Anita when she felt the urge to shoplift. Vinny looked a little out of his depth.

“I think we should let him find the ladle and take it with him. No harm no foul. None of this ethnic stuff.”

“Ethic, Vinny. Not ethnic,” Anita corrected.

“Whatever. The dragon’s getting rid of it anyway. Let’s help this dude out. Or are you going to snitch?” Anita stiffened.

“I am not a snitch. But I’m not going to help. I will claim plausible deniability. I’m going to sort the forks noisily. Nobody bother me until he is gone.” She stuck her nose in the air and strutted off. Vinnie helped Max up.

“Iseult, you were sorting the spoons, right? Any sign of a ladle?” Vinnie asked. Iseult thought. Did she really want to get involved in this mess? There was a lot more risk involved here because of the many people present. She supposed that the faster she helped, the sooner Max would leave. Then Sophia would owe her a favor, and that was a good position to be in.

“Yes, they are this way.” She showed them to her pile. “I hadn’t sorted the different serving spoons yet, so they’re just separated from the dining spoons.” She pointed to the comparatively little pile.

“How will you know when you found it? If great-grandma was the last to have it, neither of us was born.” Sophia asked. Max narrated his motion this time to his pocket.

“I am grabbing my charm, not a gun.” He pulled out a necklace with a large quartz pendant. He held it up to his eye using his hand to cover the other one. “This pendant reveals enchanted items. I figured there couldn’t be too many enchanted ladles out there.”

As it turned out, a surprising amount of cutlery was enchanted. What it did, they didn’t have any clue.

But Max’s hunch proved correct when only three ladles glowed under his keen eye. It sucked though that they ended up having to search through the big mound as it evidently hadn’t made it to their more organized piles yet.

They debated which one might be correct. Vinny seemed to think the rose-gold one with an intricate handle was the most viable candidate while Sophia argued in favor of the heavy cast-iron one. Max seemed unsure. Their debate froze as they heard footsteps coming down the stone path. The distinctive clack-clack of Mr. Nancy’s shoes. Sophia, Vinnie, and Iseult stood in front of Max, trying to hide his presence. Mr. Nancy swung the heavy wooden door open.

“Now how are things going in here?” He asked jovially.

“Great!” Sophia squeaked.

“Glad to hear it. Only three hours left!”

“We’re working on it, sir,” Vinnie replied. Nancy narrowed his eyes.

“So get working. Don’t let me stop you.” The three stayed huddled together. Anita called him over, taking pity on their plight.

“Sir, can you help me for a moment? I’m having trouble distinguishing between the fruit and fish forks.”

“Anita! Hard at work, I see. Of course, I can.”

Iseult braved a glance behind her. But Max, and all three ladles, were nowhere to be found. Sophia followed her gaze, then sighed in relief.

“He must have vised away,” She whispered. The other two nodded and shuffled back to their piles to continue sorting as innocently as they could.

When Sophie got home that evening, sweaty and grimy and smelling like nickel, she napped in the back seat as her parents drove across the state. Her mother’s sister’s son had found Nene’s Ladle and everyone was going as quickly as possible to celebrate the good fortune.

an endless succession of confessions exchanged between a collapsing body and the bathroom floor weak knees sunken into gelid tile, genuflecting before my reflection, a ravenous demon, and i am nearly humiliated enough to pray for reprieve my head gyrates like a drunken ballerina posed atop a pedestal, eyelids flutter like limp petals and with time, the pressure inside gives way to kaleidoscope skies and bloodshot eyes to an inverted indulgence in the saccharine bliss of cinnamon apple pie yet, i deny my addiction to the friction of delicate skin against teeth coalescing salvation, sin, and sacrifice succumbing to an unabridged temptation, the repulsive compulsion to defy gravity.

Us In Another Life

gonna forget…

Strange woman

Strange woman Nestled into me She moves away clenches my hand

Warm smile Turns into a Furrowed brow

Beauty mark on her left cheek I reach for my own In the same placement

Dull heartache in my chest

Unfamiliar And fragile

I feel I should worry Am I safe?

Oh Strange woman

Her face, angelic And familiar

I must know her name

Something warm fills My chest

I must know her name!

Glazed glances Across the room

This is not my room

Yet, silently I feel relief

A hospital! A hospital?

Well, now I must be safe

Thin sheets snug my skin

A tv in the upper right corner

A man motions and speaks

Weather screen behind him

Charles! My love!

He’ll be wondering Why I have missed dinner I must call

Must Call him!

‘Dinner at 7 o’clock, Agnes!’ Clock. I need a clock

“What time is it?” I must call him! Where is my phone?

Searching

Through thin sheets

My bed feels smaller Lumpier than usual

“It’s eight, mom.” I startle I thought I was alone! Now who said that?

Beautiful girl…beautiful girl! Beauty mark on her left cheek I reach for my own It’s in the same place! My sweet, beautiful girl! What did she say?

There it is

A thick black case that holds what I need

It’s more clunky than I remember His number, muscle memory Six…zero…eight…se-

Sounds jumble in the background I pay no mind

Some light flickers in the upper right corner of the room I pay no mind

My precious child waits her turn

To hear her father’s voice

She must miss him I turn to her, but oh!

My beautiful girl has disappeared!

In her place, a Strange woman

Beauty mark on her left cheek I reach for my own…

Beautiful woman

Her eyes recognize mine I wish to know her name

My daughter

Where is she?

My –Oh…

My Sarah.

My daughter. I have done it again.

Sarah holds the remote, Her eyes are silent waves

They hold a sea of tears.

All grown up, Yet she still needs her mother. And her mother, A strange shell of Who she once was.

My beautiful Woman!

“Sarah, I am…so sorry.”

Sarah’s sorrow boils over I open my arms.

Sarah crumbles into me. I am not…

You’ve Caught Me

Elee Sharp

grief is a five letter word followed by a four letter name. Ray Kirsch

fill a church with children and tell them to grieve their peer who would know to cry to deflate to push him away until he dies in their minds and real life january 24 has become a repeated day wear yourself out rush through it and forget about him forget about years ago and funerals his face

fill a church with people and tell them this was all god’s plan and don’t let their gazes drift from the slideshow of a boy to his stone flesh on display a funeral about a boy’s life is re-examined as your new favorite bible lesson but he doesn’t play a little boy but a disciple, a man no 13 year old boy

fill a church with your god and tell him to look me in the eyes as he replaces my home with a cold basement a child corpse i don’t want god to look me in the eyes but rather his eyes look into his january 24 eyes and tell me if he’s the perfect disciple for your plan the satisfying pawn to play your game

grief is a five letter word followed by a four letter name. my words cannot return him.

In my first few years of life, my shyness was debilitating. I hated the swimming lessons I took at the local YMCA because we were separated into groups by ability so I wasn’t with my sisters. After a few weeks in a given group of swimmers, I was ready (ability-wise) to advance to the next level. Unlike most kids, who would probably be proud or excited to be moving up a level, I dreaded it. A new level meant new people. It was bad enough to be without my parents or my sisters, but to be without even one familiar face? The thought was sickening. Literally. I was once up half the night throwing up because I was so worked up about the thought of my swimming lessons the next day.

To cope with the stress I felt as a young child, I chewed my nails down to stubs. They were tiny, uneven, and hopeless. It felt bad and looked worse. Of course, my mom wanted me to stop. She explained to me that it was harmful to my nails and teeth, plus unsanitary. But it didn’t matter; I couldn’t seem to help it. It was how I dealt with the stress I experienced in my preschool life. But it wasn’t sustainable; my mom and I both knew I had to stop at some point and the earlier it was, the easier it would probably be. She decided to try a nail-biting deterrent. The clear polish doesn’t look like anything, but it tastes terrible. The idea is that you won’t want to bite your nails anymore because it is so unpleasant. I still remember the sharp, bitter taste. I didn’t enjoy biting my nails then, but I still sometimes did out of habit. At one point, the polish spilled on our table. It completely ate through the wood finish of the tabletop. It was then that my mom decided she didn’t want chemicals that harsh to be anywhere near my mouth, so the nail-biting deterrent was abandoned, and it was back to square one.

My mom told me that if I stopped biting my nails, I could get my nails painted for my fifth birthday. This was very motivational for a four-year-old like me who was obsessed with hair, makeup, and beauty in general. I fought so hard to avoid the

temptation. For anyone, but especially a young child, delayed gratification can be frustrating. But I managed to stay strong.

I had a princess-themed birthday party at a little event space in the neighboring town that specialized in children’s dress-up parties. Disney movie music played throughout the small venue. There was bright afternoon light streaming in through the windows from outside, but the lights inside were dimmed and the colorful light of a disco ball bounced from wall to wall. There was a huge collection of princess accessories we could wear for the afternoon: crowns, dresses, wands, gloves, purses. But that was all merely set up for the main event. I finally had nails that deserved to be painted. I chose a metallic silver nail polish that I thought would tie my whole look together. The woman who ran the business painted my preschool-sized nails with care. I felt elegant. I felt proud. My Cinderella costume, lipstick, and tiny painted fingernails were the height of class. I left my party that day feeling transformed. Sure, being five instead of four was pretty significant. But more so, I had demonstrated self-control. I had wanted to change something about myself and successfully changed it. That, to me, was adult. I still had some social anxiety but at least I no longer had gross chewed-up nails. I haven’t bit my nails since; the habit was broken.

But one bad habit has a way of replacing another. Shortly after my fifth birthday, I began picking at my cuticles. They would bleed and scab and heal and then I’d start all over again. One day when I was in third grade, we were given a writing prompt. My teacher told us to identify our favorite body part and write about why it was our favorite. Then she walked around the classroom and took a photo of each student’s prized feature and the essays and respective photos hung on the hallway wall. This sounds really creepy. I don’t know if that’s indicative of the loss of my own childlike innocence or a sign of a world that has changed

for the worse in the last decade. I have a hard time picturing this happening now, but it was innocent and fun at the time. I, like many other students, wrote about my hands. I don’t remember exactly what I wrote, but I believe I discussed all the activities my hands allowed me to do. I was able to draw, write, color, play with toys, help my mom bake, and that sort of thing. I was proud of what I wrote, though I’m sure everyone else in my class had pretty much said the same thing. I felt good about it. What I didn’t feel good about was the picture. I didn’t choose my hands because they looked good; I chose them despite how they looked.

I was embarrassed by my picked-at, scabby fingers. I only had myself to blame. I wished I had been warned so my hands had the chance to heal. As my teacher walked around the room with her digital camera, I tried to think of a quick fix to make my hands look better, but there was nothing. Time and self-control were the only solutions; at the moment, I had neither. My hands hung up on the wall outside my classroom for weeks, shaming me every time I walked past. For apparently being my favorite part of my body, I wasn’t very happy to see them.

It wasn’t long before I learned that even if I took great care of my hands, they might still not look the way I wanted them to. Growing up, my granddad told my older sister, on multiple occasions, that she had beautiful, elegant fingers. “Those are piano-playing hands,” he told her. “You have such graceful and long fingers.” My fingers were by no means short and stubby, but her fingers were noticeably longer and slimmer in comparison to mine. The widest point of my fingers has always been at the proximal joint, or the knuckle at about the midpoint on the finger. I think this makes my fingers look a bit chubbier than they are. For years, I was convinced that the difference between her hands and mine was just the two-year age gap, as if my slightly thicker fingers were the result of lingering baby fat. If I was patient, my hands would become slender and dainty like hers. I’m still waiting.

In high school, I dated a boy with a bit of a fixation

on hands. He noticed others’ hands and claimed to see correlations between people’s hands and their personalities. The size and shape of one’s hands apparently indicated how extroverted someone was, their sense of humor, or what kind of friend they were, for example. He grouped people by their type of hands, saying that people with similar-looking hands had similar personalities. He would give examples of people we knew who shared hand types. At the time, what he said made sense to me. In hindsight, I don’t know if I agreed because I believed everything he said, or because his examples were valid. At any rate, he seemed to have me and everyone else all figured out; he could know me before we ever spoke, simply because he had observed me gently drumming my fingers on a desk or brushing my hair out of my face. There was no hiding myself; it was written all over my hands.

One day, we sat in his car as he held my hands in his and examined them. His car smelled like him: fresh, woody, and a tad spicy. It was intoxicatingly aromatic, especially to an impressionable sixteenyear-old. “Your nails are too long,” he observed. “I don’t like long nails.” I looked down at my fingernails, natural and unpainted. Trimmed appropriately and lightly filed, they were about the length I liked. Long enough to be feminine, but not so long that they were an inconvenience. With just a sliver of white at the tips, they were perhaps even a bit short for my liking. “This is as long as they should ever be,” he told me. I said okay.

We didn’t date for long. Months later, we were catching up on what had happened since the breakup. He had started college and met a bunch of new people. I was jealous; I was still in high school. It seemed to be a lot easier to move on when in a new city surrounded by new people with a new schedule full of new interests. I was at the school where we met, walking past his former locker in the hallways, talking to people he knew well. But I pushed my frustrations aside and listened to what he was saying. He told me about one new friend in particular. “She has the same hand type as you,” he said.

He never let me in on how to read others’ hands. He never told me what my hand type meant, in

terms of my personality. Because I didn’t have the same weird affinity for hands as him, I could never know him as well as he knew me. He had this handy (no pun intended) knowledge that he didn’t share with me. That didn’t seem fair. He could just figure out the hand type of the girls he liked, then switch us out effortlessly. If you knew exactly what to look for, then replacement was easy. He reignited my awareness of my hands, my yearsdormant concern that my hands were a reflection of myself, in ways I both could and could not control. I then resented my hands. Maybe if they were more dainty and slender, I wouldn’t have been such a provocateur or I would’ve been a better listener. If my fingers were more graceful and elegant, maybe that would also mean that I would have been smart enough or more fun. If my hands made me who I was, then I didn’t like them, because then they were the thing I could point to for why I found myself lonely and heartbroken.

To top it all off, hand shape aside, they still didn’t look good. What had changed since third grade? I didn’t take care of my nails because they didn’t look good and the fact that they didn’t look good meant it wasn’t worth taking care of them. For someone who claimed to appreciate her hands, it sure didn’t look like it. I had written a whole (thirdgrade-length) essay about it but didn’t believe myself anymore. They were chewed up then, and they were chewed up now. Over a decade later, nothing had changed. Five-year-old me wouldn’t be proud of the fact that I continued to let a nervous habit take control of me and eight-year-old me wouldn’t be proud of how my hands remained. When was I going to start taking care of my hands and also make sure they were taking care of me? When was I going to take as much pride in my hands as I claimed to back in third grade?

Years passed by and I grew up. I came out of my shell because I was sick of missing out on experiences due to nerves. I realized that the boy from high school hadn’t been very good to me. I learned to speak up for myself in relationships. I decided to go to a huge university where I would regularly be forced to confront my former worst nightmare of large groups of people I don’t know. Over the previous decade or so, I had gradually

gotten over my once-debilitating social anxiety. I had made huge strides in pushing myself to grow and become a better version of myself. But I still had messed up cuticles.

One day, I looked around at the other students in my lecture. Glossy pale pink nails clicked away at a keyboard to my right. Shiny forest green nails gripped a pen to my left. In front of me, classic bright red nails wrapped around a Starbucks cup. I had heard from other girls that once you start getting your nails done, then you always have to have them done; they can never not be done. If they’re undone, you’ll feel naked or unfinished, as though you are going about your day with bedhead or fuzzy slippers instead of proper shoes. For years, I told myself that I couldn’t start that vicious cycle because it would be too expensive. I claimed to not like having my nails done because it is inconvenient. But maybe that was just an excuse because deep down I didn’t think I could do it.

I made a manicure appointment for three weeks out. That would be plenty of time to break my habit and heal my suffering hands. Unfortunately, it’s also enough time to relapse once or twice. I was sick of not having control. Booking the appointment gave me a deadline for when I had to stop if I wanted to be in good shape going into it. Whenever I remembered to, I applied cuticle cream before bed, to try to speed up the healing process. But I knew the only thing that actually works is to quit doing things that require healing time; stop it at the source. The issue is that when you are trying to quit a bad habit is when you need one the most. Maybe I should take up a new bad habit that destroys some other part of my body. Like smoking. At least my hands would look good gripping a cigarette.

Around this time, I was working on a midterm essay. One of the topics I had to write about was how I define success and failure. To me, you know you’re successful when you’re proud of yourself. Even if you’re not the best, you can take pride in giving it your best effort. All you can do is all you can do, so if that’s not good enough, you cannot blame yourself. On the flip side, failure is when you don’t give your best effort and make excuses

for your shortcomings. When it came to taking care of my hands, I was a failure. I knew I was completely capable of achieving what I wanted to, I just didn’t.

When the day of my appointment finally arrived, I walked to the nail place, fighting against the harsh November wind. When I opened the door to the nail salon and stepped inside, the smell of chemicals hit me in the face like a ton of bricks, almost enough to make my eyes water. I could never get used to this, I thought. But by the time I left, I had. I paged through a thick binder of color samples and selected L134, a deep olive green. The electric drill buzzed, sanding down my cuticles and filing my nails effortlessly but aggressively, bits of fingernail forming a dust cloud around my hands. The nail tech finished filing, then rubbed my hands with an exfoliant scrub with such force that the knuckles of my fingers cracked and popped. I washed away the scrub under the lukewarm tap and admired my nails’ new shape. I watched as he painted my nails with speed and precision I don’t think I’ll ever be able to achieve on my own. I let my eyes wander around the room as much as possible. I didn’t want it to feel like I was watching his every move or reading over his shoulder. No one tells you how awkward getting your nails done is. Crappy covers of mediocre pop songs played through the speakers but the air was still heavy with awkward silence. I left the salon feeling the same, except now I had to be careful cracking open cans and digging through my pockets for my keys. I couldn’t escape the chemical smell of the polish for the rest of the day. It was like a Sharpie perpetually under my nose, a constant reminder of my new but same self.

Before, I hated that my hands weren’t a reflection of myself. Or, rather, they were an accurate reflection and I just didn’t like what I saw. I wanted to start taking care of my hands because it felt like the way to do right by my third-grade self. Hands are important. They are how you greet someone, with a handshake or a wave. I wanted to be proud of them. After, I liked what I saw as my fingers clicked away on the keyboard, pressed buttons on the microwave, and clutched that can of seltzer water. Five-year-old me had felt transformed by