Staff

EIC

Alice Van Haaften

Fiction

Lauren Downham

Sophia Tourdot

Art

Grace Zhang

Emma Atschul

Poetry

Lauren Pickel

Jane McCauley

Marketing

Peyton Hennig

Meredith Schadrie

Alice Van Haaften

Fiction

Lauren Downham

Sophia Tourdot

Art

Grace Zhang

Emma Atschul

Poetry

Lauren Pickel

Jane McCauley

Marketing

Peyton Hennig

Meredith Schadrie

The mission of Illumination is to provide the undergraduate student body of the University of Wisconsin-Madison a chance to publish work in the fields of humanities and to display the talent of emerging creators. As an approachable portal for creative writing, art, and scholarly essays, the diverse content in the journal intends to be a publication for academic and community interests alike.

1 --- Letter from the Editor

2 --- Cloak of Red, Mandy Choy

3 --- Chasing forever, Noah D’Souza

6 --- We have always been, Sandrine Biagul

7 --- Metanoia, Alina Schwartz

8 --- Digitized-Encrypted-RecievedUploaded-Burned, Valerie Babenkova

9 --- Birdfight, Miriam Hayes

10 --- Pest Pen, Julia O’Hagan

12 --- The Monforth Mail, Bryce Dailey

14 --- Definitions, Sophia Tourdot

15 --- Speechless, Mandy Choy

16 --- Miigwech, Wrigley Bastian

17 --- Memory Bank, Leah Maitland

18 --- Fruit and Vegetable Cans, Jessica Sharp

19 --- The Hunger Within, Zoe Nelson

23 --- Nostalgia, Miriam Hayes

28 --- Emergence, Laila Smith

29 --- Powwow in my Room, Wrigley Bastian

30 --- Summer Camp for Sinners, Julia Smith

32 --- Impure, Rhushil Vasavada

33 --- Thadd, Hailey Johnson

34 --- Sieve, Emily Sautebin

35 --- Discomfort, Charlotte Knihtila

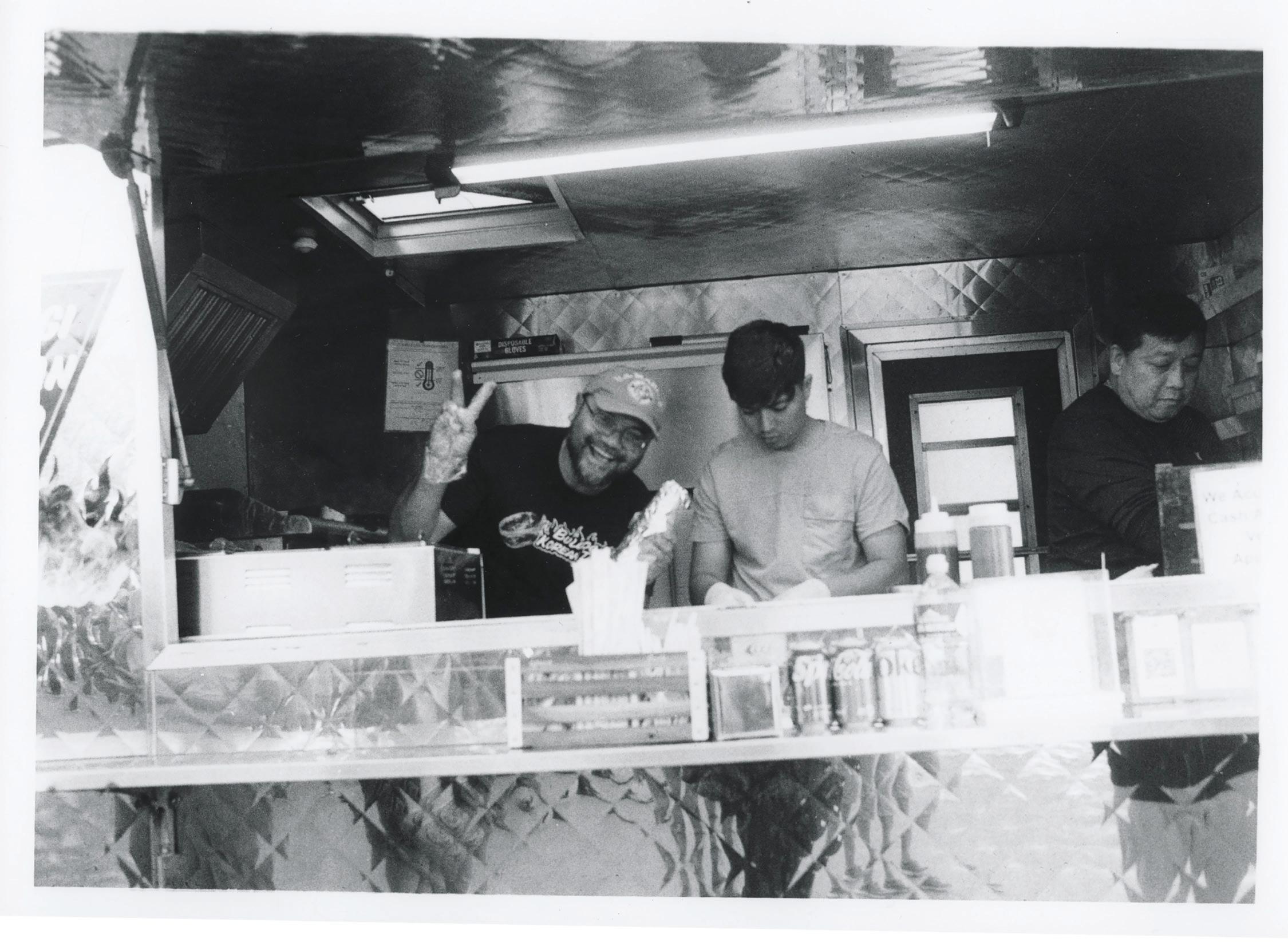

36 --- Market Price, Laila Smith

37 --- A Night at the Movies, Natalia Zeise

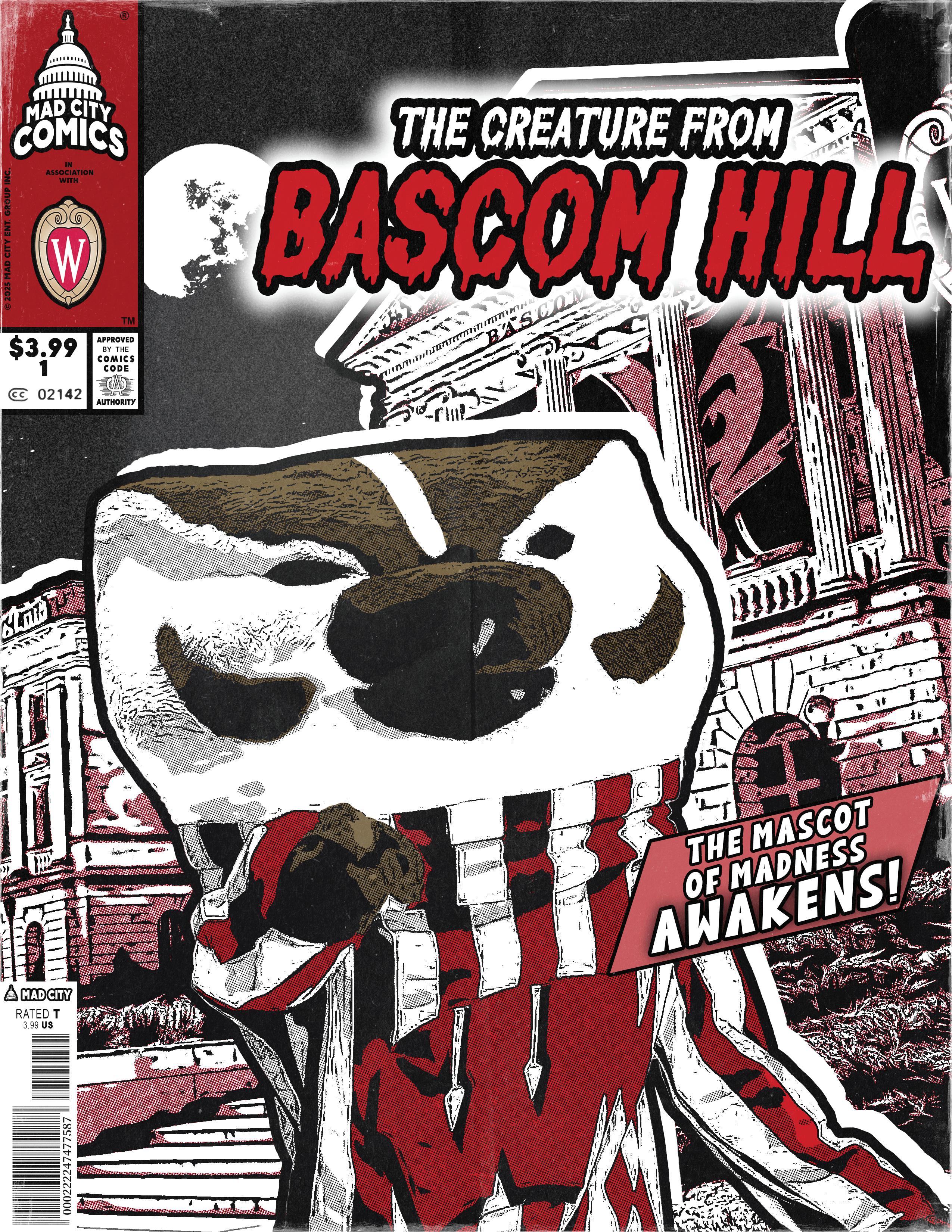

39 --- The Creature from Bascom Hill, Billy Powel

41 --- From Mother to Daughter, Jessica Yang

42 --- Fish Watchin’, Anna Bitoni

43 --- A Kind Sea, Anna Bitoni

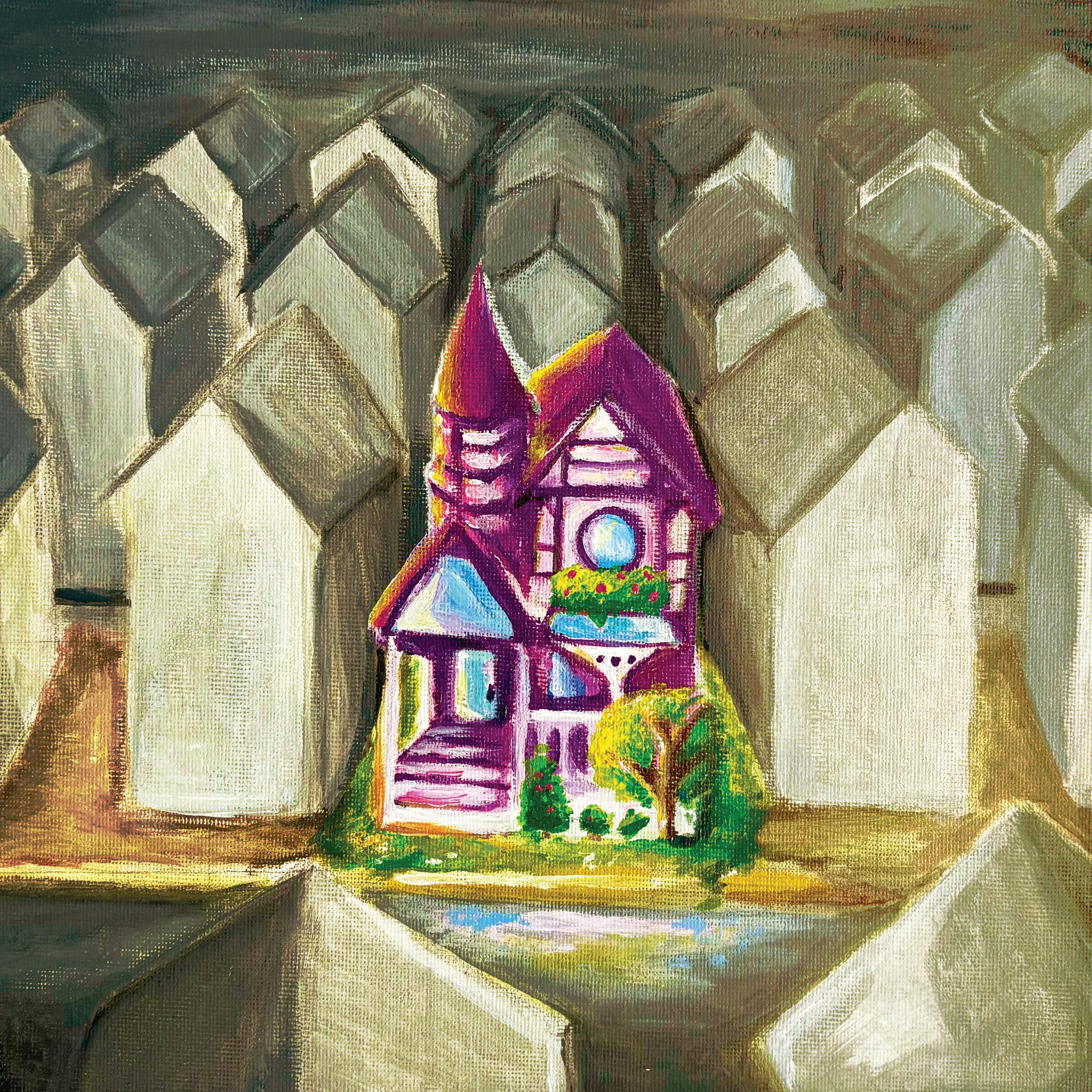

47 --- Little Purple House, Anna Bitoni

48 --- Someone’s Smile, Yolitriz Aca Martinez

49 --- Untitled, Elizabeth Thao

50 --- The Old Farmhouse, Brooke Andersen

51 --- I’d Rather Be Quiliting, Jessica Sharp

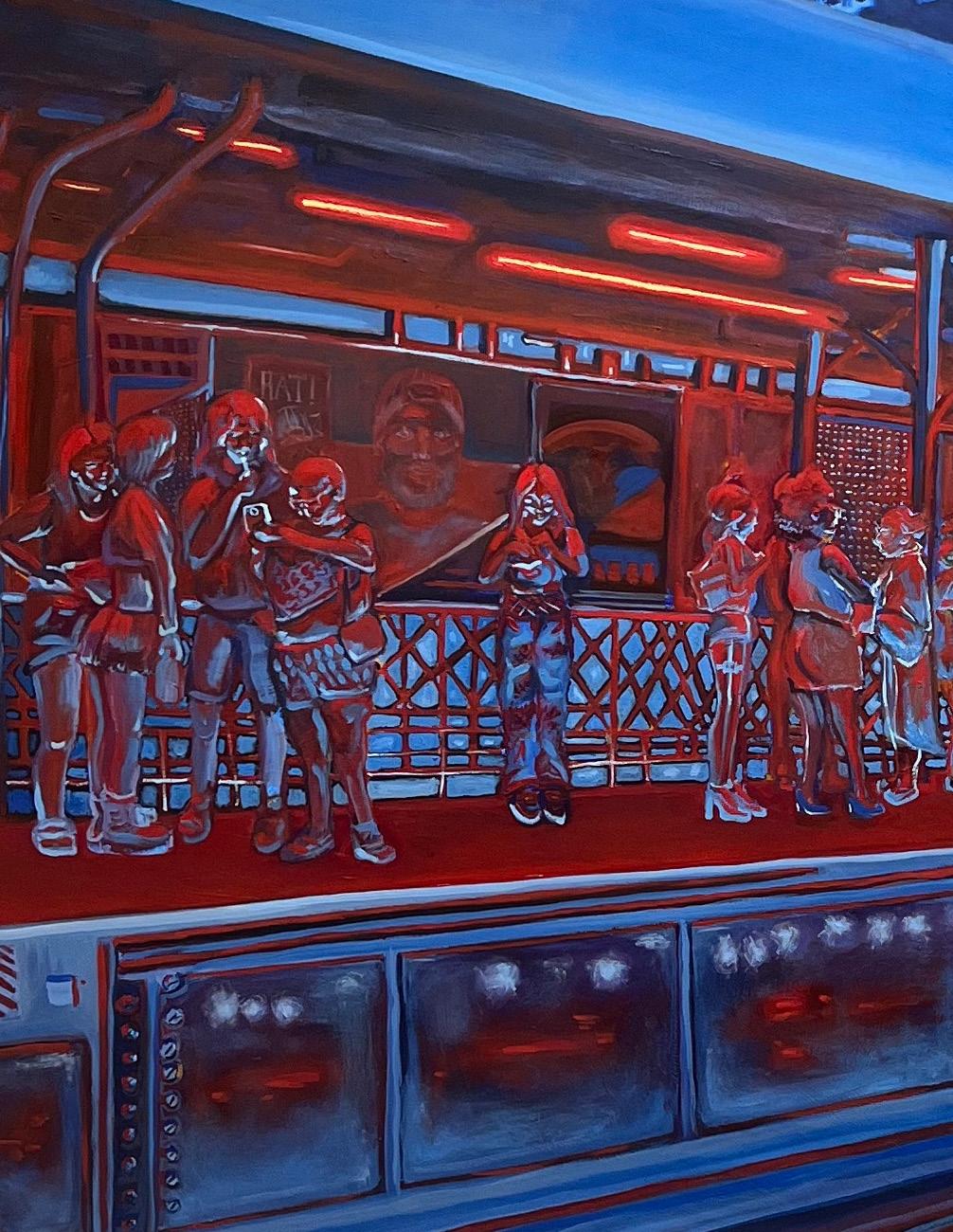

52 --- Blue Line, Rachel Hunter *Cover Art

54 --- Red Silk, Kataline Lee

57 --- Earth, Joy Kim

58 --- Spiraling, Anna Bitoni

59 --- Celestial Bodies, Leah Maitland

60 --- Cerulean Eyes, Hailey Johnson

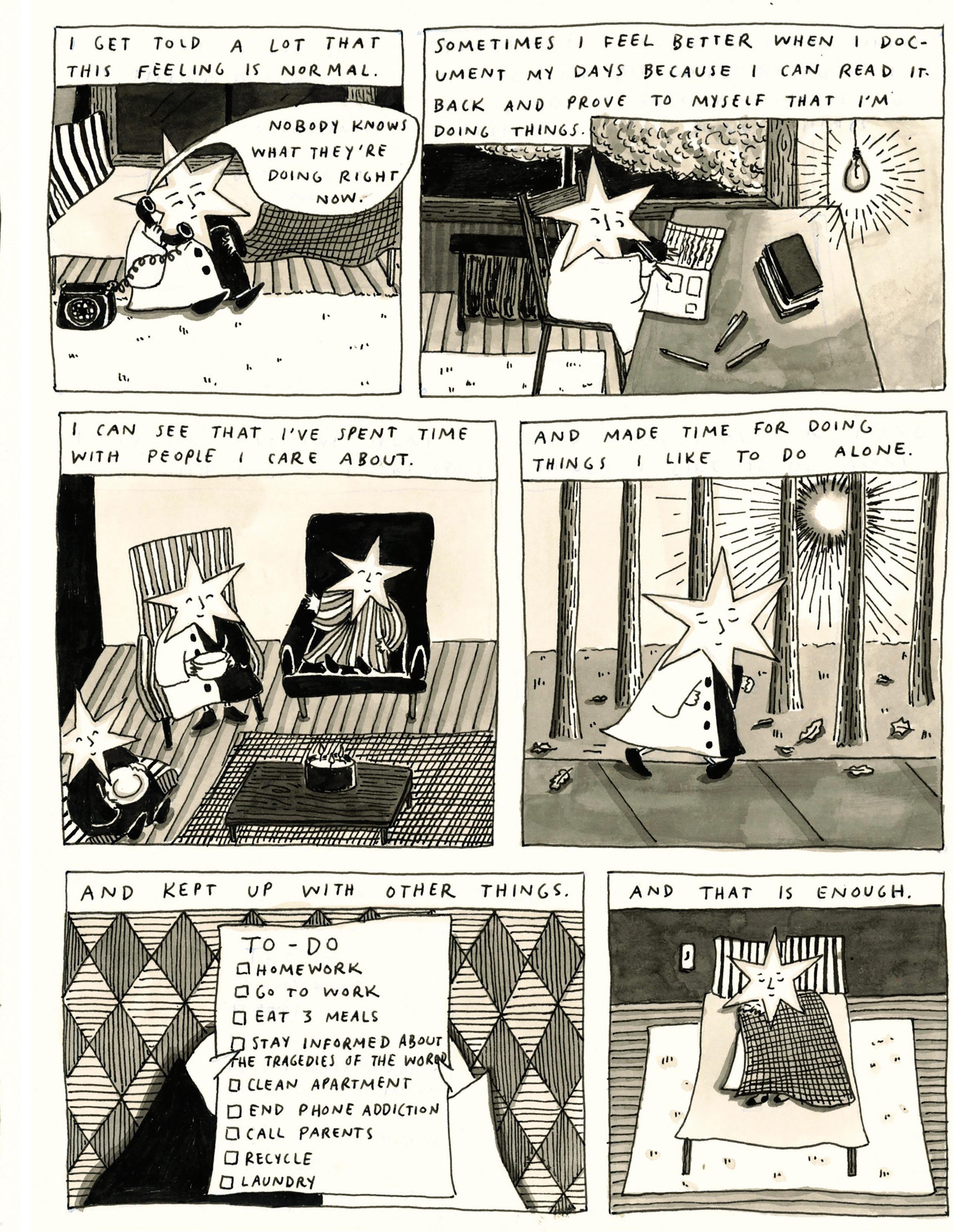

62 --- Doing Enough, Katrina Koppa

63 --- The Water Always Wins, Liv Abegglen

70 --- On the day my mother dies, Mal Virch

71 --- A fifteen-year-old learns about mortality

72 --- Make some noise, Mal Virch

Dear reader,

Welcome one and all to the 2025 edition of Illumination Journal!

I am incredibly excited to share with you all this year’s edition of Illumination. Whether you are a disparate reader from state street or a close to home artist on campus, we are so excited to have you!

Illumination Journal is the center for undergraduate humanities. Illumination’s goal is to showcase and publish UW Madison’s student work—connecting artists and their art not only on campus, but also the community as a whole. Art connects and invades all of what we do now more than ever. Like art, it serves as a bridge of creativity and craft. This edition is a testament to the community and connections that are made through these wonderful bridges.

I’d like to first say to all the artists—thank you for sharing a piece of your heart. We received one of the highest numbers of submissions that we’ve had in the past couple of years. All of these pieces, chosen or not, were full of the life and time that created them. So thank you for your passion, your talent, and for trusting us with these wonderful pieces.

As a student-based journal, Illumination not only relies on our artists, but a talented team of editors and supporters. They have been hard at work over the course of the year not only making connections for this magazine, but also within our community. This edition of Illumination would not be possible if not for the patience, hard work, and thoughtfulness of so many.

So, to my editors, thank you for dedicating yourselves to this wonderful magazine, to these artists, and Illumination’s dream. To my executive team and WUD Lit director Brianna Rau, thank you for your unwavering support, open wisdom, and for always looking for ways to help.

This issue would never have been possible without our community, which includes you, dear reader! This magazine may have been about weaving the connections, but it’s only the beginning. The power of this print isn’t just about the connections it has made, but the connections it can be making, here in your hands. So my final call to you all is to read and connect. With the art pieces or the artists. The images or the message. Perhaps even with the person sitting next to you. I hope you enjoy this edition of Illumination, together! Happy reading!

Alice Van Haaften

She/Her/Hers Editor-in-Chief

Mandy Choy

Four pairs of bare feet pound the ground. With each landfall, they sink slightly into the moist earth before once again launching the small bodies to which they are connected into flight. Four lungs ache and burn, stabbed by chilly air and overworked by four pairs of feet. Four childish faces smile, shriek, and laugh as a father chases his four children in mock pursuit. Eventually, four children are overtaken, their legs too short and their lungs too small to run for long. They are scooped up, screeching and screaming, punching and kicking. Their voices, already inhibited by their father’s arms, descend into primitive grunts and shouts as the tickling begins. On that autumn afternoon, as if caught in a spell, four children were lost in time. Swirling leaves and clouds of breath completed the enchantment. None of the four felt a need to cherish this moment. No one told them to take note of the emotions, the feelings, the sounds, or the surroundings. This game was sure to last forever. The mindless exuberance and innocent intentions of the players would never end.

Four pairs of legs bend and stretch, now strong enough to propel the awkward bodies to which they are attached over fences and across hills. Despite the complaints of tired

lungs, four minds stay the course and hold true to their goal. Four faces, shaped by experience and burdened by knowledge, maintain expressionless focus as they race away from their father, who follows in intense pursuit. The blinding ecstasy of the past has been replaced by maturity of thought and a desire to win. Four hearts pound as they near the finish line, just ahead of their father. Finally, four children slow to a stop. They are halted - not like in years past by the failures of their bodies - but by the shouts of their father conceding defeat to the children he once easily overtook. Four siblings relish their victory as they return to their panting father. None of them recognized the melancholy of their accomplishment, the finite nature of the game. No one told them that their father could not chase forever, that they could not be chased forever. Something was changing. The magic of the moment rippled and contorted, resisting the inevitable. No one told the children to fear this change, to delay it as long as possible, and to savor every second of freedom before it arrived. In their exuberance, they let the moment slip away.

Four pairs of muscular legs sprint across fields and through forests, strengthened by years of training. Four young adults easily outrun their father, who stumbles behind gasping for breath. Four minds are distracted by worrying thoughts of homework, friends, grades, and sports. The

complete focus on the chase that once came so naturally now eludes them. Four blank faces do nothing to betray their waning interest in the game. They do not hear the cries of their father as he is forced to give up, his aging legs no match for those of his children. This time, none of them care about their victory. The game had lost its meaning. The magic was gone, lost in the folds of growing up. Eventually, the teenagers return. The sight of their father, so quickly defeated and clearly outmatched, unearths in them a faint memory of years past. It awakens them; a cold splash of water on their distracted minds. They recall an autumn afternoon, swirling leaves, and clouds of breath. Somewhere deep inside their conscience, a longforgotten feeling of unimpeded recklessness and unknowing innocence calls out. The call is just a whisper; the feeling impossibly far away. Four heads fall and four eyes close as four minds stretch as far as they can and then some, frantically trying to recapture the magic of the past, to recast the spell and stop time once again, to stay forever in that extraordinary moment. It was not to be. Four small children all those years ago had not savored the time spent racing away from their father in the crisp autumn air. How could they have known to? Back then, the chase was infinite, the joy everlasting. Standing in a circle around their father, locking eyes with one another in understanding, four

teenagers finally realized otherwise. Infinity had come to pass. Forever was now.

A father sits alone at his desk, reminiscing about days spent chasing his young children, scooping them up in his arms and tickling their little bodies. His knees creak. His back hurts. In the silence of the empty office, he can almost hear their shrieks and giggles. In the harsh, artificial lighting he can all but see swirling autumn leaves and puffs of breath. He would give anything to go back to that time all those years ago, to see his children once again lost in youthful ignorance, unworried and unknowing. He wished that he could chase them across moist fields and over fences, that his back and his knees would put aside their grievances for one more hour, one more moment of unbridled joy with his children. But he knew that it was not to be. The four pairs of feet would run no more, the four once-childish faces were now adorned with facial hair and worry lines, and the four minds were preoccupied and hardened. So instead, the father, sitting alone at his desk, hoped that his four children had cherished the chase. He hoped that they had taken note of the emotions, the feelings, the sounds, and the surroundings. If they had captured just a little of the magic, saved just a little of the moment, that would be enough.

Sandrine Biagui

I am my Dad’s daughter.

Creation of holy, divine.

He says we are chosen people

I’ll admit we are proud

Worn in our braids

And walk

We wear it in gorgeously time managed patterns

Embedded into the scalp

In the bright colors and elaborate designs

Sewn to our skin

As if we outwardly project what my father so brightly loves to remind me. To seek greatness in our heritage

Despite this I believe divine isn’t just what we are

As behind the red and yellow and green dashikis

Laid bare before the world

My skin

The people that hold the divine

That do or don’t take the time in their stride.

That can define as I do

And all people with my complexion do.

My father says we are designed to be holy people. So he inclines me to say his prayers before every meal

But I’ll admit I’ve seen him take more than a sip of wine on a Friday night.

He gets down to a beat

Turn on some Biggie and see him out of his seat

After claiming him as one of his own

Sharing more than just their color of skin

We first had to be people to be holy. To be the divine then is to be this:

I was my father’s daughter. Before I became part of a chosen people

I walked Before I strode. Rocked a Fro before braids. The black beret before color

To be black is his kin I’m divine as I am

Valerie Babenkova

1. I delete myself: shatter into pixels. I soar through solids on wings of Wi-Fi, to retinas in visible A single drop of water thrown into a cloud. And I am unseen. Unformed by my animating of the keys.

2.

I am images, encoded in decade-old JPEGs. Sandwiches upon a cloth-checkered picnic table. Sunbeams stream through sap-soaked needles dense spruces smother it smother someone no longer there.

Perhaps if you magnify a single pixel of me remains unerased forever.

3.

The resolution on a government surveillance satellite is about 10-15 cm. A fullgrown common shrew is just small enough to be invisible.

4. In another iteration I am caught in CVS security camera I blur between aisles of cough drops and tortilla chips. It snares a glance the blue of my eyes encoded into the foreboding terabytes of a hard drive.

5. A bonfire loses itself in the intangibility of an uncontrolled inferno.

Bryce Dailey

Bridge noun

1. A card game with the standard 52 card deck in which tricks are collected in order to win

“When I was very young we used to play bridge but now that I’ve grown and left town we seem to be strangers.”

2. A method of moving over a normally uncrossable expanse; a construction connecting two or more destinations

“I was able to take the bridge across the city to see her instead of risking the frigid and tumultuous waters on a boat.”

verb

1. To reach out across a distance that seems insurmountable

“I took the trip because I wanted to bridge the gap between us in a way I didn’t know how to over the phone.”

2. To combine seasons of life or experiences in a way that mends an otherwise disjointed soul(s)

“I’ll never regret that as it bridged our two formally, fragmentary lives once more.”

Thank you

Was thrown at those who they tried to destroy

So abrasive, so different, for those who survived

Thank you

Nothing but salt in the wound

For they took everything that could have been taken

Thank you

They said, as they took kids away

Never again would those kids ever play

Thank you

They said, as if that would suffice

For the land that they spliced

Thank you

Was an insult

For it had no backbone

Thank you

No never again

Let’s change the story, the Native Nations said Away with your thanks

Away with your lies

Let us below our own words

That you tried to scrape form the sky

Miigwech

Was passed tentatively from a pair of lips

Miigwech

And you could not disguise, the gleam in their eyes

Was passed around a table

Full of genuine food and big belly laughs

Miigwech

Was said to the water as it flowed

And you could almost hear them sighing, for their people still know

Miigwech

Not only conveys gratitude, but also carries a deeper meaning of acknowledging someone’s kindness and the interconnectedness of all beings

Thank you

hardly

Leah Maitland

My papa was built of stacked coins sheathed in orange pill bottles, a dementia relic stuffed great depression style; I’d search the cavity beneath his dresser for dropped memories, loose dimes.

Piles ever-growing, I’d swallow pennies in prayer, one by one; dear Father, may the cents of his mind outweigh cognitive change conversion rate made weary in old adage.

When he died having forgotten my name the slit entrance of my mouth echoed piggy bank overcrowded with oxidized teeth; Grief choked behind copper bulging cheeks.

Jessica Sharp

Zoe Nelson

Come to the Forest.

It’s not actually a forest, of course, but it’s not like we have a better name for it, and besides, who decided what a forest has to be in the first place? It talks in a voice that isn’t a voice, in a place that isn’t a place, so honestly, the forest semantics are the least of my worries.

I pause at the counter, hovering over the half-kneaded bread. Flour dusts my clothes and hair, giving me a matching crown to my mother working outside. Wind and snow howl through the mountain pass, coating everything in their path. My mother digs out the henhouse, her dark hair and red scarf bright against the landscape of white.

Come to the Forest. Come back to us. The words slide over my ears, down my spine, their caress familiar yet unwanted. I shudder. The Forest has been growing more insistent since winter arrived. That’s nothing new. It’s more difficult to tame desire when hunger slices against your stomach, when cold beats down your door.

“When will it be finished?” Mariya asks me. She sits below me, absently dragging a scrap doll across the floor.

“It has to rise first.” I fold it over again, the soft dough sticking to my fingertips. I add another pinch of flour and continue the motion.

“But I’m hungry now.” A familiar tug against my chest.

“I know. Mama is out looking for some eggs. Does that sound good?” Mariya looks at me, unconvinced, but she eventually nods. I glance out the window again. The snow is coming down heavier now, less a curtain than a wall.

The door opens, a gale preceding my mother’s entrance. “Hens aren’t laying,” is all she says with a rough cough before tugging off her boots.

No dinner then. I refocus on the bread, covering it in a thin cloth and placing it on the window sill. Vasya, the voices restart again, Vasya, come to the Forest.

This time, I don’t ignore them. Stepping around my sister, I step into the storm.

Six berries is all it takes. It’s the easiest way I’ve discovered to enter, though some of my earlier attempts were memorable. I’ve kept a stash handy, tucked away in the pocket of my woolen coat. Reaching inside, I press the dark circles to my lips, wincing at the bitterness that floods my mouth. The pain hits my stomach soon after.

Within a minute, I am inside of the Forest. No birds call, nor leaves rustle. The snow is unmarred but for where I stand.

There are no trees.

Instead, gnarled icicles reach from the ground, reflecting enough light to look like a beam itself. Hundreds of them surround me, their arms reaching out, stretching across the frozen plane.

Vasya. My name is a whisper, caught between branches and ice. I take a step forward, then another. Reaching a hand out towards the nearest trunk, I hum a lullaby beneath my breath.

The threads of tone suddenly coalesce into a voice that is real, whole. Icy cold burns up my finger, but I do not draw away. “Come to make another bargain?” it asks.

“This is the last time.”

“Everyone says that.” It is silent for a moment. “What do you want this time?”

I pause, running over my phrasing. “I want you to grant luck upon both my family and myself. Our food won’t run out, nor will our room cave under the snow. Fever will be banished from our home, and until spring, no other misfortune will befall us.”

It’s more ambitious than anything I’ve asked for before, and by the sound of its surprised laugh, the creature knows it too. “Soon,” it mutters gleefully.

The cold has turned to a burn,

and I’m choking down air as fast as I can get it. “Do we have a bargain or not?” I yell back, throwing my weight against the glowing icicle.

It sighs contentedly. “Of course, dear Vasya.” I yank my hand away, and in the same instant, wake up facing the sky.

My clothes have long grown damp, and my once-dark braids glisten white. I push myself back to standing, noticing the sun now hovering low over the mountainous horizon. Distantly, I hear Mariya call out with delight.

“They were just buried, Mama! Look, I found another.” A chicken scampers by me in a flurry of feathers, chased out by Mariya’s excitement. I snatch it quickly, cradling the hen’s warm body towards my own frozen chest.

The Forest works quickly. We eat eggs for dinner, the once struggling fire burning brightly beside us. It only improves from there. Father returns the eve after, caribou carcass slung over his fur-clad shoulder. I help him skin and salt it, hanging each strip carefully in the small shed. Winter continues on in the usual way, long nights and bitter days, but there is food aplenty, and for a time that is enough.

Few of our neighbors fare similarly. The frost came on early this year, most of the harvest dead before it could be dried and saved. Hunting is an option, but only for those brave enough to challenge the wolves for what little prey remains.

None are willing to venture into the Forest.

I keep my own journeys there secret, though my mother suspects. The first visit was an accident. I slipped from a mountain ledge while trying to collect the moss that grew there. Its gossamer strands are pungent, but it works wonders for curing pain. I woke up in the clearing. Even now, I cringe at the first time, my bargain unpracticed and sloppy. Still, I returned home with more moss than what grows on the whole mountain. My mother shot me the same look she did then as she does now. Yet it’s difficult to be angry on a full stomach. We eat bread and porridge, sprinkled with cinnamon from a jar a trader exchanged for a mere bauble. When our closest neighbor, a young widow carved of porcelain painted with a fraught hand, stops by, baby poised on her hip, I hesitate for only the briefest of moments before ducking into the house and emerging with six precocious eggs. The woman tucks them close to her chest, moving her baby out of the way to fit them.

Winter falls to spring, and for once, it is met without jutting ribs, the torso of the mountains that surround us. No, it is a spring of rolling hills and soft stomachs. When I see the thaw, my first thought is not of starting the vegetable garden. No, I think of flowers.

Yet the wanting does not fade. It is hunger in the deepest of the winter, always craving, never satisfied.

No matter how much I eat, it always returns.

“You’re back,” the voice says, sounding pleased. I inspect my chest, finding it smooth and unbroken. There is no hint of blood, no sign of the knife I plunged through my chest to return here.

“I just missed you so much,” I deadpan, finally looking up at the icicle. It’s grown larger since the last time I’ve been here, yet twists in that familiar way that I know it is the same.

It practically cackles, light bursting out of the ice in sharp bursts. I shield my eyes, waiting for it to stop. “And what is it that you want now? Luck ran out?” Its voice reminds me of church bells, a cacophony of different tones that make it impossible to pinpoint what it is, a harsh yet melodic boom that echoes through my skull and into the very marrow of my bones.

“I require a dowry,” I say, “for both myself and my sister, once she’s grown.” “Hoping to enchant some poor farmer into marrying you?” It pauses, and a cool wind passes over my body, inspecting. “Or are you ensnaring yourself a greater catch?”

I straighten, fighting off the growing chill. “I fail to see how that’s any of your business.” In truth, I do not know the answer myself. It would be easy to find someone in the village to take me, even without a dowry. A steady man, a simple life. That’s what awaits me outside of the Forest.

Or I could become more. Want more. Why should I become a simple farmer’s

wife, when I could be a baroness? A tsarina, even? “I just require the dowry,” I repeat.

“You ask for much while giving little in return.” Its voice is suddenly more brittle. The temperature in the glen drops further, and I shiver into my shawl.

“I stabbed myself in the heart to get here! What more could you want?” I shout back.

“You can not imagine what I want,” it hisses back. Snow sweeps up from the ground, stinging my face. I drop to my knees, shielding my face. The storm eases just as fast as it speaks again. “Still, I will grant your request.”

I imagine my mother’s shocked face when I return, dowry in tow, my father’s lack of worry, my sister’s freedom to marry whoever she chooses. I imagine another winter without worry, of full stomachs and goosefeather blankets. Most of all, I think of my future, a life I carved out of myself, blood and all.

“But simply coming here is not enough.”

“What?” This is new. In every whispered tale of the Forest, the cost is paid just getting there. The icicle rattles, further catching me off guard.

“It was easy enough for you to sacrifice your heart once. All I want is for you to do it again.”

“I don’t understand.”

“You can have your dowry,” it says. “But you will never find love.”

I pause for a moment. There was a time when I dreamt of soft love, one

I could call my own. Then I remember my sister’s ragged dress, my mother’s waxen face. All I need is a bit more. Love is a small price to pay. “Done.”

The cottage is uncomfortably warm compared to the Forest. I stare at the wooden ceiling, feeling an uncomfortable wetness beneath me. Blood.

While the wound is gone, it still coats the floor in a sticky pool. I don’tdidn’t think about that. The scrub brush is quickly found, and I remain on the floor until my knees sting and the floor glistens. My family hasis all gone to market day to trade our leftover grain for a new goat. Mariya told me quite solemnly this morning that the cutest goats produce the best milk, and she’s the best judge. I braided her hair back for her so she could see the goats clearly, and sent her on her way. I’m glad she didn’t see the blood. This trip to the Forest wasn’t a planned one. The voice had been getting louder for months, pleading and offering. I thought about it often, of course. There’s so much to want, so much to gain. But I’d resisted, until last night, when I heard news of my cousin Irina’s own marriage. She was homely, but rich, living just outside of the capital city with her merchant father. I have never met my uncle, but Irina stayed here once, complaining of the work we made her do, and when she was released from her chores, of boredom.

I was not sad she never returned.

Why is it that Irina should marry, and not I? The question plagued me as I washed the morning dishes, soapy water biting into the fresh blisters that decorated my hands. Why shouldn’t I have more?

With my family gone, I barely remember even lifting the knife. A loud knock from the door. I open it to find a soldier, dressed in fine wool and holding a chest. “Are you Vasya Kozlova?” he asks.

I nod wordlessly, and he extends the chest. It’s heavy, sending me stumbling forward under the weight. “A gift from your grandfather.”

Inside, gold coins sit in stacked uniform, bordered by thick strands of pearls and hearty rubies. White linen lays tucked beneath, only the golden corners of what I assume to be a bridal cloth peaking out. It is a king’s sum, and most certainly not from my grandfather.

But I’ve learned not to question the Forest’s methods, and send the soldier on his way.

I haul it inside and grab a second wooden box from the shed. A box for me, and one for Mariya. It is not an even split. I find myself collecting more and more of the delicate necklaces, taking larger chunks of coins. But I cannot stop.

Mariya has time. Years before she will marry, and she will not likely go beyond the village. I settle another large jewel into my own box. Besides, if I marry rich, she will not want for anything already.

“Vasya!” I shove the two chests beneath my bed, and run out to greet my sister. The next time they journey to the market, I go along, a bag laden with coin tucked into the deep folds of my cloak. Vendors shout loudly, fighting to be heard over the animals and crowd commotion. I whisper to my mother, then slip into the crowd.

I head towards the horse merchant. Makeshift fences have been erected, half a dozen stallions rearing and trumpeting in one, while mares and foals crowd another. I sidle up to the edge, peering at a silver horse.

“Pretty big horse for a peasant girl,” a voice behind me says. A slight smirk graces my lips, but I force it away.

“Somehow, I think I’ll manage.” I spin to face the boyar’s son, a tall man with a thick beard, thicker eyebrows and an oily smile. He’s only a few years older than myself, but he towers over me by at least a head. “He just requires a firm

hand.”

“And that hand is yours?” he asks, sliding closer.

I pull out the bag of coins, watching his eyes widen. His family is by no means poor, but it takes an enormous amount of money to maintain an estate. I lean closer, my braids brushing the button of his woolen jacket.

“Want to bet on it?”

When I finish unsaddling my winning horse, I leave the market with more than just a heavier coin purse. The boyar’s son’s gaze burns into my retreating back.

Three days later, I receive a marriage proposal of my own.

For a time, the Forest feels far away. The marriage itself is short, a mere prelude to the days of feasting that follow. On the wedding night, I sneak the chest out from under my bed and give it to my new husband. It is not typical, but I cannot bring myself to care. What does it matter if he draws away from my skin, finding it cold?

I’ve carved this life out for myself, and I’m not giving it up now.

My family doesn’t understand what happened, my father particularly. It should have been his job to find me a suitable husband, even for a soft spoken man like him. But nobody denies a request from a boyar. I conveniently leave out my own hand in the matter. They stay behind, and I find myself not caring.

“Can you sign this?” It’s a servant girl, no older than fourteen, with a face as wan as fresh butter. I sign the

scroll wordlessly, sparing it little more than a glance. The routine is easy. Ilya, my husband, spends most days away. In his place, I sign the tax laws. It’s exceedingly dull, but the fares must be collected from the peasants. Occasionally, some old maid or crumpled son will come to the manor to beg. Desperate for a lord’s coin, and unwilling to make the sacrifices I did for it.

“We haven’t the money!”

“There’s barely grain to last till spring, and my oldest boy just took sick.”

“Please.”

I’ve taken to barring the front gates, directing servants to leave round back instead. The saved time allows me to go back to the Forest. At first, it’s just to secure more money. Then again to soften my calloused hands, soften my jagged corners. Ilya doesn’t comment on the changes, but his overnight travels to town decrease in frequency. They stop altogether once the boyar is dead.

It takes the sharp bite of an ax against my neck, the wood knotted and torn beneath me. The groundskeeper does it for me, though I have to pay him an outrageous sum. He mutters about witch women and devils, but lifts the shining blade all the same.

The Forest sputters and hisses, but agrees to kill the boyar. In exchange, I will never bear a child of my own.

The choice is easy.

After I return, I kill the groundskeeper, using the fallen bag to hire a new one. I catch whispers from the other

servants, but I offer no explanations, and after a while, the whispers stop altogether.

They watch me and my husband through pressed lips and slitted eyes.

“We should leave behind the village,” Ilya says one night as I slip into bed.

“Visit the capital for a winter.”

I pause, considering. The tsarevich has taken a liking to him, as increasingly rich and noble men so often do. I have given him both, with a beautiful wife to boot. Ilya holds power.

I hold power.

“And who will watch the house?”

“The servants will manage. Besides, I have already been invited to partake in the Grand Hunt this year. It would be a shame to miss it.” He grips my wrist tightly.

“I’ve always wanted to see it,” I say lightly, tugging my arm away. Ilya releases it, rolling over with a sigh.

“I’ll ready the sleds in the morning. We’ll leave by evening.”

My finest dresses are readied for the occasion, every ostentatious shoe polished. Three servants pack my things, never meeting my eyes. They hover and peck about, reminding me of the chickens from my old home. I wrinkle my nose and turn away. A loud shout comes from outside. Ilya. I walk towards the window, gesturing for it to be open. But the lever never turns.

Instead, I feel the cold press of a knife against my spine.

“I’m sorry Lady,” she says. “But we cannot face another winter of this.”

There are more shouts from outside, the loud trumpet of the stallion I purchased so many months ago.

The other two grab my arms, tearing me away. My dress catches and rips, imported silk and saltwater pearls wasted upon ill-gotten grievances.

“I’m sorry,” my sister repeats, the knife tip penetrating the fragile skin. Betrayal burns heavy in my chest. I inhale deeply, then fling myself towards the floor. I use her brief shock to kick her feet from beneath her. Mariya falls to the ground in a noisy clatter, the knife spilling away. I snatch it, briefly measuring its weight. She gasps at me and scrambles away. But I do not make a move towards her. Instead, I press the blade to my neck, and make a smooth cut across. My choked gargle turns into a breath of freezing air. The Forest stretches out in front of me, devoid of life. It’s now a comfort as I turn to face the icicle.

It has grown as any other tree would, twisted and gnarled, branches like hands reaching out. It scarcely looks like ice, brilliant light pulsating out of it. I press my hand against it, savoring the bitter bite of cold against my flesh.

“Vasya,” it greets, as any friend would. “What is it this time? More jewels? A new husband?”

“I’ve grown tired of jewels. And I believe my husband has been taken care of already.”

It laughs, voice clanging. “Ah, so that’s what it is. You want him back then?”

I frown towards the tree, before readjusting my woven braids. One hangs loose, an aftermath of the scruffle. “No, I most certainly do not.”

“Did you kill him yourself?” Delight radiates off of it. “Or did you use that fancy dowry of yours to pay someone off?”

“Neither,” I say. “But that’s irrelevant.” It pauses, waiting for me to continue. I stroke along the ice.

“I never want to die.”

“You wish for immortality.” Its tone has gone flat, the light quickly fading from inside the twisted ice. I press closer, trying to draw it back out.

“Yes,” I whisper. “I have everything else I could ever want. Power, money, status. But I need more time.”

“Then that is what you will have.” Glee has crept into its voice now, and I draw back slightly. “You will live forever, just as you are now.”

Cold sweeps up my arm. I pull it away from the ice, but it continues up my arm, over my shoulder. The glen begins to laugh around me, echoing, trapping me in a ringing haze.

“What’s happening to me?” I ask, taking another step back.

“You’re getting what you wanted.”

I try to take another step back, but my feet are frozen into the ground. Pain radiates as my legs fuse together, flesh peeling and reshaping. I scream, but my tongue freezes to the roof of my mouth. Even as I tear at my skin

with my hands, feeling begins to flee from them. I let out a choked groan, before the sound cuts out completely.

“After all, you wanted more. You want and want and want. Well now, you can want for an eternity.”

A tear escapes, freezing on my cheek. The droplet of ice spreads, covering my body until I can no longer see, no longer move. I let the darkness swallow me. When I wake up, I find I can talk again. It is no longer the same, but nothing is. I am the tolling bells of a forgotten church; I am everything and nothing. My words roll across the land, waiting for the right ears to listen. I feel a ripple of cold over my skin as a young boy perks up to listen, discarding his plow.

Come to the Forest.

Wrigley Bastian

There’s a Powwow in my room

Drum beats bounce off the walls

With singers bellowing songs

There’s a Powwow in my room

And once I grasp the tune

There no stopping what’s going to happen soon

There’s a Powwow in my room

And though it may seem there’s only me Ancestors dance around encouraging me

There’s a Powwow in my room

As I bounce around on my toes

I can feel restoration in my bones

There’s a Powwow in my room

Dancing for those who could not May the jingles reach those who forgot

There’s a Powwow in my room

And though the room may be small

The good energy goes beyond the walls

Others knock on my door complaining of noise

If only they knew

There’s a Powwow in my room

Julia Smith

Toes across rough, hot asphalt, kick up dirt used in buckets with pebbles and bricks signed with a second grader’s signature.

The door swings, and the air’s thick with scrambled eggs stuffed in the mouths of babes reciting scripture forged in chicken scratch and branded into hot, red faces doing their best to catch a breath.

Holy water and sermons on Mary–The Virgin…

In the fluttering eyes of babes picking at scraped knees and whispering to thy neighbor.

But blood runs dark. It runs red faces out of town past the city limits over two cliffs connected by James Avery necklaces gifted for pastors’ hands against heads and backs, drowning in water with open eyes and whispers of the Holy Ghost.

Rubber bracelets chafe, and trunks crush toes, seconds, hours, years in crowded gyms of sweaty socks and brains inside skeletons subconsciously working overtime with no pay to rid broken hearts of sin prescribed by the hands of

men whose lips etch words in your skin.

The Virgin Mary may have had the immaculate conception, but at least Mary Magdalene got paid to STOP because everyone has porn in their pockets and can’t stand the fact that camp is for sinners with issues and lost souls, but how’d you get lost when you were looking at the map?

Will y’all please bow your heads on shoulders shrug up and down in the 9th circle, Lucifer waits and plots on the highest point of the high dive where toes dangle over the possibility of eternal life with Jesus Christ, my Lord and Savior.

And all God’s children said:

Amen.

Rhushil Vasavada

In the most populous nation in the world, there lies a population who are invisible and untouchable. Their sorrows and sufferings are cast in the dark, compounded further and further like rocks aging into fossils. The pain has not been for years, nor centuries, but rather millennia; emerging from a society of superiority and inferiority, in the name of false religion.

He walks around in the endless fields of shacks and huts and trash, scavenging, just like his siblings, parents, grandparents and ancestors. They don’t have any hope left, when others around them don’t have hope either; they are shunned, branded as unlucky and inauspicious. The rich relax in their high-rises, selfish, offering heaps of sweets and riches to idols of god, turning a blind-eye to virtues of compassion and to those who really need it.

The vast diaspora, too, lives in the comforts their counterparts can’t dream of–yet even they cannot stop judgement when it’s subtler than looks and names. It continues because it has been this way for so, so long, and change carries the burden of altering our identities. Waste has always been associated with the notion of caste purity, and in a country so large, it will never stop being produced.

And so, we dream of a time when someone’s caste is not determined by their birth, but rather how they lead their life.

We envision of a time where caste is no longer synonymous with money or lack of it, but instead what one does with their wealth. When our focus is directed inwards to what pure really means, only then can change occur, for those who hail from the most populous nation.

Emily Sautebin

I am a prisoner of my own body and its cruel idea of a man whose words to me are nothing but water through a sieve.

Nothing honest catches— it all falls to the drain.

Is freedom the brave hand cupped beneath the sieve or the one that turns the faucet off?

Charlotte Knihtila

Just outside of the heavy glass doors, the autumnal sky cries purple and indigo as the sun descends beneath a hill. A few blocks away, stadium lights radiate, and I can hear screams of excitement coming from the field. I wonder who is winning while my nails scrape at a lump of solidified butter on the faux marble countertop. The cinema is not busy this evening, but then again, it is never busy.

Why am I here?

I am working. I am here to work.

In walks a man. He is a shadow. He listlessly walks to the ticket counter with an equally listless smile. I’ve never seen him before. His teeth are pretty.

My feet ache from standing for so long. I wish I was outside. Part of me wishes I was at the game, but I know being there would only make me feel worse. There is an ache in my stomach. No. Below it. Below my stomach. And it’s not an ache, it’s a vacuum. I imagine a wormhole opening in my abdomen, and it’s pulling all my organs into it. It will stretch and strain until every organ pops and rains blood onto whatever world the wormhole leads to. My blood will nourish the plants of this other place, and everything will be so lush I won’t even mind that I’m dead because I will be so beyond happiness that my body has finally proved useful.

The man is now approaching my counter. He is still smiling lazily. His skin looks strange in this lighting. It glistens, yet it is not oily. The neon signs blare, illuminating every blue vein snaking through his face. He looks so strange, and I can’t tell how old he is, but his teeth are still pretty.

“What can I get you?” My mouth is very dry.

“A cola.” I see flames in his pupils, and I wonder how long he has walked this earth. I don’t think I like him. As I pour his soda, he asks; “You like football?”

Laila Smith

“Not much,” I respond. That’s a lie. I don’t mind football. I mind the feeling of loneliness that I get when I stand in the bleachers and realize my classmates like each other a whole lot more than they like me.

The brown cola looks uncharacteristically appealing to me today. Suddenly, my mouth has too much saliva even though it felt dry just a few seconds ago. This machine always puts too much syrup, and I can feel the thick sugar on my tongue. I put a lid on his soda and gave him a straw. “$4.75.”

He digs through his jacket for a wallet. “Don’t you want to hang out with your friends?” There is no concern in his voice. Only curiosity, like I’m a bug stuck through with a pin. He finds the card and I say:

“We don’t like football.” Another lie. My friends like football, just like they like each other more than they like me.

His card is heavy. I bet he’s rich. I feel like he knows I’m lying. I feel like he knows I have nobody. I don’t think I like him, but he is looking at me. Through the halls, on the street, in the grocery store, eyes sweep past me. Nobody stares, and nobody cares. I lie to myself that my solitude is pleasing, but every morning I do my mascara and I hope someone will stare for a moment. I don’t mind that this man observes me like a specimen, there is no harm in looking.

“Would you do me a favor?”

My fingers fumble with the card reader. He lifts a brown paper bag and places it gently on the counter. The bottom looks dark and damp, like something spilled, but it’s hard to tell in this light. When I look up he still has that easy smile.

“Would you look inside and tell me what you see?”

I look over to the ticket counter, but Carrie is gone. She must have gone to smoke out back. I am alone, of course.

“I don’t understand,” I laugh. I laugh when I’m nervous. My teeth chatter and I slide the card back over the counter. The screen asking for a tip pops up but I skip it. I just want him to go. I don’t think I like him, but he just pushes the bag closer to me, slowly, the same blue veins pulse through his fingertips.

“I just need you to look,” he whispers. His voice sounds like butter melting in a frying pan. Maybe I could like him.

Faintly, I ask “Well, what’s in it?” Everything is so quiet, I can hear the two of us breathing, and in this moment I see our breath intertwining in a longforgotten waltz through the stagnant cinema air.

“The eyes of a god.”

The flames in his eyes burn higher, as bright as funeral pyres. Carrie still hasn’t come back. My fingers stretch out and toy with the fold of the bag. I feel ill. Dizzy. When I blink I can see his pretty teeth on the backs of my eyelids. I wonder if he wants to eat me. If he wants to sink his teeth into my flesh and ravish me

until I am nothing but a pile of molars and bones with the marrow sucked clean off. I can’t imagine I’d taste good. In his eyes are now mushroom clouds. I stretch the bag open.

Inside is the wormhole. His fingers are in my hair. There is no air in my lungs. He whispers “Good.” My organs are stretching. Blood is raining from my eyes. My body.

Jessica Yang

The pink hues of the clouds make me think of my mother’s potential. It must’ve felt like falling off a cliff, giving that up for the duty of a nyab. Her story stitched out on the paj ntaub before she decided. I wonder if she would’ve become flight attendant and traveled the world.

Except longans don’t fall far from its tree, and she is still trapped, hanging on by that branch, held on by the responsibilities of womanhood, that are poking at her like needles; Growing babies like a gardener to her seeds, playing the roles of both waiter and cook, being a walking calendar and a list of reminders.

This whir of expectations ties mother to daughter. Yet that sprinkle of hope is our true bridge. That we may change the futures of short, dark haired, and full of potential, little girls who reflect us.

So maybe one day the clouds will not remind me of my mother’s lost dreams. But instead of the things she was able to give memy knowledge, the path I walk freely, and my dreams, which will let me fly, where she had been chained.

Anna Bitonti

They say the sea gives back. In the way memories will ride the waves and tumble on to shore, clawing through damp sand to return to their owners. In the way words spoken long ago will come in with the sea spray, splattering the stone pathways down by the beach. Little pieces of humanity pepper the ocean, and most say they always seem to return.

But Ren knew all the sea did for her was take.

And it was never kind enough to give back.

She skipped another rock into the water, watching as the smooth gray stone sank after two bounces. Two spreading rings remained, rippling outward till they, too, disappeared.

She scoffed. One for my father and one for my brother.

The ocean favored irony—its favored, vicious lash.

“You took them,” Ren whispered. “Must you also mock me about it?”

She filled her hands with rocks and tossed them, one by one, into the still surface, breaking the peace. Cracking its facade.

“Take my family, take my rocks. Take all of them, you can have it all. Take them!” Ren fell to her knees, ignoring the bursts of pain as sharp pebbles dug into her skin. Tears welled behind her eyes, hot and fast, and she quickly lost herself to the tight, withering sensation constricting her chest. She grasped at her heart, as if she could tear it out.

“Take me!”

Screams. They were hers, ripped from her throat.

She pressed her forehead against the sand, its miniscule grains cutting into her eyelids. Into the bridge of her nose. They pressed against her lips and cheeks, and she thought she could feel each one.

“Take me instead,” she mouthed, with nothing but the sand to hear her.

Ren knew the sea could hear her too. It answered in the way the tide tilled the gritty beach, in the way the waves carried her brother and father’s names like precious shells, only to dash them against the rocks. In the way she could still hear their voices in the sea spray.

The sea heard her, and in the hush of its rocking, churning waves, it laughed at her.

One. Two. Three. Four. Five. Six. Seven. Eight.

Ren repeated the sequence to herself again.

One. Two. Three. Four. Five. Six. Seven. Eight. She shook her head; the steps were wrong. But when she lifted onto her toes to try once more, her calf cramped and she fell to flat feet, hand shooting to her leg.

Slower, Ren. It wasn’t her voice reminding her, it was her father’s. Feel the music. Touch it, taste it with each movement.

So she straightened and raised her arms high, reaching for the dusty sun beams emerging through cracked, dirty windows. She lifted herself up to try again, to sweep across the floor as she had always been able to do…and crumbled.

The cement met her with its cold embrace, and this time, Ren stayed down.

“I would love to feel the music, father,” she whispered into the empty space, “Except I cannot. Not anymore.”

There was no music. No beautiful notes twirling in the air. There were no dance lessons, no bar to stretch her cramping calf on, no satin shoes. That all disappeared when the sea had wrapped itself around her father’s fishing dinghy and swallowed him whole. She’d been notified in the middle of her pirouettes at the Fine Arts University and rushed to the beach in her pointe shoes. A fellow fisherman had seen the boat go down,

but it was only after hours of the wind ripping at her and people gazing upon her with a harrowing sort of pity, did something deep and inevitable settle into her soul. It was colder than the chill in the air. That frightful dread—that touch of death—worsened the moment she’d returned home and could not find Jae in his room. Ren had crumbled then, too, understanding that her little brother had stowed away with their father to avoid school, as he often did. And just like her father, had been washed away. She had dropped out after the incident months ago. Ballet never called for her the way the sea did. Ren shivered against the cement at her back and glanced toward the large windows of the abandoned building. Almost sundown. She preferred to try it here, in this decrepit space, so the only thing watching her failure was what had already been forgotten and left to rot. It was easier that way. She rarely spent time at home anymore. Their two-bedroom flat sat on a street corner in one of those unremarkable outskirt-towns, right at the merging of civilization and the sea. It was filled with her brother and father. Ren sat up, brushing the dust from her legs as the room glowed orange. What hurt could it do? The ghost of her father whispered. To try again. To feel it again.

She wondered how it had felt when the water entered their lungs. Wondered if her father knew Jae had

been with him. She unfolded to her feet and raised her arms.

How high had the waves risen before crashing down on them, breaking like thunder?

She swept her shaking leg to the side. What had they thought of? Or perhaps the sea stole those memories too. Ren sagged. Drew her limbs back in. So much hurt, father. Too much, she answered. She gathered her things and left.

***

Ren always returned to the sea. It was as if she couldn’t help herself—and the sea was just as greedy for her pain as Ren was willing to give it.

She stared at the distant horizon, at the line of blue and pale gray, so blurred one couldn’t tell where the sea ended and the sky began. All the sea did was stare back. It spoke to her with its white caps, the way they churned and rose. She responded with the press of her bare toes into damp sand, hoping the sea could feel the hatred seeping from her skin.

The chill often became so cold it transformed into a stinging heat, but she never left.

Ren wanted their memories back. Little boats bobbed miles out, their white sails flapping in the wind. Crabs crawled and dug through the sand. Shells in fragile whites and pinks washed in with the tide, then left with it too.

Nearly beyond her sight, clouds roiled. Ren tasted the storm brewing in the

air. That salty tang and the scent of rain. Wind already circled over the city, threatening. Her hair lashed around her face, black strands catching on her eyelashes, on her lips. Let go, daughter. The haunt of her father’s voice attempted to calm the storm. “Clouds are already forming,” she murmured back.

Listen to what I have always told you. The sea does not forgive, for it has nothing to remember.

“No. It has to.” Ren pressed the palms of her hands against her eyes. “It has to! I miss you. I need you both back. Please…come back to me.” The great blue swallowed her words. “Please.”

The storm only came closer. ***

The next day, there was no attempt at ballet. There was barely any light. There was only the tempest raging off the coast, the pale-dark night that stared back, and Ren before the sea. The water at the docks was different. Even in the storm, it retained a sense of peace, of purpose, that was lost amidst the frightful deliverance of the open ocean. The docks never drowned anyone. She toed off her shoes and tossed aside her rain jacket. Then she settled at the end of what had been her father’s dock and dipped her feet into the freezing water, relishing its bite.

She knew the wooden posts and swaying boats like the back of

her hand, even in the dark. Even as rain pelted her. Her father had tried to convince her to venture out with him, to watch how a fisherman worked. Ren had always refused, disliking the slippery feel of nothing solid beneath her. She’d volunteered to bring boats in instead, unloading catch, docking and tying off. Jae had been beside himself that she’d passed up the opportunity—he would have given anything to live the sea-life, to breathe nothing but the ocean every day if he could. But he’d been too young, then.

Ren wrapped an arm around the wooden post beside her as the winds picked up, her fingers automatically feeling for the carvings. Near the top were her father’s initials, and hers followed just below. Then a few inches down, in deep, sure gouges, were Jae’s.

Grief was an odd thing. It wasn’t wicked, nor was it malicious. Instead, it…flowed.

It hit her sometimes, the way an enormous wave would form. And other times, it would lap at her feet and caress her skin. Sometimes, grief was a harbor amidst a storm, full of broken boats and fury, and sometimes it was a gentle creature with knowing eyes and strong shoulders.

But always, it was tangible. It would crawl inside her body and curl up, settling itself between her organs, constricting her ribs and playing with her veins like strings of a cello. She’d listened to its music for so

long.

Ren thought that remembering was the worst part. Recalling who her brother and father had been in life and knowing they could be nothing more after death.

Grief was one more thing. It was final.

Slowly, Ren brought her hands to her face. And wept.

Her lungs could not seem to get the air they begged for, and her tears mixed so fervently with the rain that she couldn’t discern the difference. She wrapped her arms around herself and imagined the warmth of a family. The sea watched her. She could feel it, unsettled by the storm as it flowed and shifted and broke toward her.

After all the anger, all the denial…she found herself exhausted. And with the rise of the sea, with the touch of it against her feet, the ghost of her father brushed over her head one last time.

The sea does not forgive, for it has nothing to remember.

Ren gazed into the water as it retreated, taking her father’s words with it.

“Goodbye,” she whispered. The wind became a gentle whistle, and the tall grasses brushed against each other. The rain paused for a moment as the red-crowned cranes cawed in the distance. Moonlight danced, and Ren followed the flickering beams alighting on the sea as it moved. Flowed. Then she rested her head on grief’s strong shoulder and closed her eyes.

Anna Bitonti

Yolitzi Aca Martinez

A small curve upwards on your lips, that was all took for me to feel a sense of relief

A smile that indicated to me that you liked me as well

To you it’s probably nothing, the small movement of your facial muscles to make what we call a smile

To me though, it meant my worries were all for naught, it meant that you would live and love me forever I never got used to that smile a smile that seemed so soft and genuine, so full of love and joy

But let me rephrase, I never got the chance to get used to your smile, a smile I so longed to protect and care for Life works in ways we cannot understand Apparently you weren’t meant for me, or anyone for that matter you left, and I had to watch you came into the world crying you left the world with a smile a smile directed to me carrying a bouquet of flowers in one hand your phone with an ongoing call to me in the other. we were both too excited too excited to see our lives come together, too blind to see the disaster that came next I held you as you took your last breath you smiled you lied the one and only lie you told “I will be alright” and the last thing you saw was me crying unable to return a smile that you so longed to see so I smile today

in hopes that you see it from wherever you are in hopes that you forgive me for not treasuring that smile of yours

Brooke Andersen

When the locals noticed the “For Sale” sign had disappeared from the old farmhouse, the town hummed with speculation. Small towns thrive on gossip, and soon rumors swirled about who might have purchased the place. But no one had expected her. That was years ago, and by now, the initial buzz had settled into quiet disappointment, there simply wasn’t much to say about the young woman who bought the house.

At first, she was a curiosity. The house, long faded and sorrowful, quickly gained a fresh coat of white paint. The lawn was tamed and a sprawling garden sprung up along the side, bursting with all types of greenery. A winding path was carved through the neighboring prairie, circling back to a clear, nearby creek. The locals appreciated her gentle touch, her refusal to modernize or uproot the home’s history. The house remained much the same, a relic of the past lovingly cared for, but she herself remained an enigma.

Whispers about her drifted through book clubs and bar stools. Her odd wardrobe and long, frilly hair caught the most attention, but others remarked on her shy demeanor and the way she avoided town except when absolutely necessary. Over time, people stopped expecting anything new. She became the town’s ghost: visible but unseen, a quiet recluse content to fade into the backdrop of her restored farmhouse.

What the town didn’t know, and might never care to learn, was that her solitude held layers of life they couldn’t imagine. They didn’t know about Daisy, the plump tabby cat who trailed her everywhere like a shadow. They never saw her sink her hands into the cool, damp soil of her garden, breathing deeply as if to inhale the earth itself. They couldn’t picture her at the creek, toes submerged in the chill water, finding calm as it flows around her feet.

No one had stepped inside her house since she moved in. They had no idea about the sheer curtains that waved gently in the breeze or the new screen door she’d installed to let the sounds of spring peepers in on warm summer nights. On a weathered table in the hall sat an antique phonograph, a silent nod to the past. Beneath the bookshelf in her living room lay a stack of her grandfather’s vinyl

Rachel Hunter

records, gathering dust yet treasured nonetheless. They didn’t know she’d claimed the Petersons’ discarded, musty couch from the roadside, its “FREE” sign one day found lonely as if it lost a friend. If they looked through her windows, they’d find it nestled in her living room, softened by an array of crocheted throws and mismatched pillows.

She had a botanist’s heart and the home to match. Orchids adorned her lace-draped dining table, a giant peace lily thrived beneath the picture window, and her bedroom dresser hosted a tidy line of succulents. On sleepless nights, she

would lie in bed, staring out the window at the stars, her mind wandering. Sometimes, she’d hear the distant wail of a train and feel an odd comfort in its predictable path. “It must have crossed the road in town again.”, she thinks, imagining the clank of the wheels along the track.

Her days unfolded in a soothing rhythm. Mornings brought fresh tea and a book, a psychological thriller or a gripping drama, read in the rattan rocking chair by the window that faces the clothes line. Sheets flapped lazily on the line outside, a signal of a good drying day. When the rain came, she curled up indoors with her cat, losing herself in stories while drops pattered softly against the roof.

Beyond the garden and the house, her world stretched in unseen ways. There was a hive of bees in the oak tree at the edge of the prairie, robins nesting in a birdhouse she’d built a year ago, and a creekside path where she strolled, naming plants and fungi like old friends. A tattered book on mushrooms accompanied her everywhere, ready for discoveries. And though she had never seen the ocean, her library was filled with books about its tides and shores, a quiet dream she nurtured.

The townsfolk didn’t know any of this. They didn’t know how often she wished for a chess partner, someone to play cards with on rainy nights, or the way her laughter sometimes startled even herself when she imagined sharing a joke with someone who truly understood her. They didn’t see the longing that flickered beneath her contentment, a tiny ember she carefully kept hidden. They don’t realize how much more she is than what they think of her.

“I don’t mind that they don’t know anything about me,” she might say if someone asked. “I like my farmhouse and my privacy. Maybe one day I’ll let them in, but for now, I have everything I need.”

And so, the young woman stayed a mystery, rooted, serene, and quietly alive in a world only she truly understood.

Kataline Lee

A trail of corpses always follows the Circus of Miracles. They travel the country every weekend, the beast tamers and contortionists, the acrobats and jugglers, showcasing their talents to the common folk and wealthy alike inside a large arena covered by a red-patterned tent. Most of the higher class in their wigs and powdered faces sit in their own sections, separated from the ragged children and families with patchwork pants. Despite the obvious segregation, the Circus of Miracles is for everyone. The fliers always use that slogan. It garners attention, I suppose. Circuses used to be viewed as buffoonery—low-life antics—until the newspapers started publishing articles about them and it caught the eye of the queen. Like ants, the other noblemen and bureaucrats followed her lead and began attending such shows. Unlike the others, the Circus of Miracles became a far better success. Every seat warmed by a bottom. Every inch of the air spiked with thrill and anticipation. One could say they are popular for an assortment of reasons: the host is a tall, conventionally attractive brunette man, for one—the queen loves swooning over him in particular—and the female performers are voluptuous with black-knitted tights clinging to their thick, oiled-up legs.

Those reasons are guises.

This is the fifth show I have attended. At first, I thought the acts were inhumane. People bending their legs above their heads and balancing in the sky on a tightrope—strange, is it not? Bending in such strange ways are for worms. Walking on skinny strings are for spiders. At least the actual animals they have seem to be treated fairly well, as well as you can treat a captured beast, I suppose. At best, they certainly eat well.

Under the headlights, the stage crew continue setting up for the next act, a large black box being placed on a rectangular table beside a handsaw. The previous act was quite the spectacle. Most of the time, they are clean and swift— but the last volunteer squirmed so much.

Like a little pig.

The lights dim and the entire crowd hushes silent. Because the show is free, people get in line hours before showtime to get a good seat at the front, but I do not need that. I get there a few minutes before the gates close and sit far enough to still see the performers. I find myself not really needing to hear what they are saying, see the sweat rolling down their faces. What I want can be given to me from afar.

The queen though, oh, she cackles and speaks with intense volume from her secluded, VIP section, surrounded by a few of her esteemed guests and guards. The guests have uncomfortable and squeamish expressions on their faces—understandable reaction from their status. No one in high nobility ever thought to attend such festivities before the queen. Sometimes, she brings in guests from other kingdoms to the shows, but they do not seem to share the same feelings towards the Circus of Miracles, often removing themselves from the kingdom’s trade partnership and diplomacy.

I wonder why.

It is but a simple circus. Surely, they are not so afraid of worms and spiders?

The first show I attended had been far beyond my expectations. Being of the lower middle class, the show, with the confetti, canons, balance beams, trapeze—they did not seem so suitable for low economic individuals as I had first thought. In fact, it was dramatic and flamboyant. It did not encapsulate the dullness of life, of work, of eating and sleeping for survival, not pleasure, as I am used to. Perhaps that is the reason I keep coming back. This is as close as I can get to this colorful life. Out of all the colors of the circus, red is by far my most favorable.

The audience silences upon noticing the host come into view, who is dressed in an extravagantly blue, red and gold pantsuit, face half-covered vertically by a white clown mask. He

walks with his arms stretched out as the audience re-welcomes him on stage. His long, slender hands are masked by white gloves. Despite his mouth being half-covered, I can still see his lips forming a quant smile. The smell of popcorn and peanuts fill my nose as the excitement inside me stirs once more.

“Thank you for waiting so patiently, my friends!” he yells boisterously, a mic taped to his cheek. His voice ricochets off the walls and into our ears, invigorating. “We appreciate your understanding in allowing us to spend some more of your time properly preparing for the next act. Please welcome the Saw Sorcerer to the stage!”

He swiftly exits, and the audience almost groans in disappointment at his brief cameo, as a different man, yet another fan favorite, rises onto stage from beneath the floorboards.

This man’s aura is far different. He is confident and comfortable and mighty. His tuxedo makes him look taller and slimmer than I am sure he is, but none of those really matter. It is his posture—how straight his back and shoulders are—that make him proud. Cunning. Like the results of the show are absolute and definite. Like death.

His lips and eyes match with the same half-moon smile as he nears the table and gently picks up the saw. He traces slowly the top of the saw with his fingers, as if it is the body of the woman he shares a bed with.

“May I begin with a volunteer?” he says with a silky smooth voice. He knows there is no need to scream or yell. There are plenty who wish to come on stage. After all, who would not? To be touched by a handsome man—I suppose that is one way to go out. Proving me correct, countless hands in the front rise, blocking my view. There are adults and children and old couples raising their arms, snapping their fingers and hooting and hollering. Some even plead, and they plead with grit in their voice, with sobs, with crazed desperation.

“Me!”

“Oh, choose me!”

“Please, I beg of you!

“Give me sweet relief!”

Sweet relief. Yes, I guess that is the true reason why the people volunteer in the first place, why every seat is warmed by a bottom, why every inch of the air is spiked with thrill and anticipation. But then there must be people like me too: mere spectators. The volunteers cry quite loudly, so sitting at the back is no predicament. I can hear just fine. If anything, any closer, the noise may make my skin crawl—and not the pleasurable kind.

The Saw Sorcerer takes the hand of an elderly woman who can barely stand on her own. “Oh, you poor thing. Come slowly with me.”

“She’s gonna die soon anyway!” someone screams.

“Yeah, choose someone else instead!”

Some of the children beside the old woman cling tightly to her floral skirt, pulling with all her might to sit her back down.

“Grams, what are you doing? Come back!”

“You’re not being funny, Grandma!”

But the sorcerer places a pointer finger to his lips and the crowd goes eerily silent within seconds. He had spoken no words, and yet said everything at the same time. “Hush, now. Let us all remember, who is the Circus of Miracles for?”

“Everyone,” the crowd chants. The children slowly let go of their grip. They sit back down. No one retaliates. In fact, no one talks back again. Not even the queen’s bellowing voice is to be heard, her chattering but an echo against the tent’s walls. The queen may be the queen, but here, she is like all of us. Ants.

The sorcerer guides the old woman into the box, laying her down on her back. Before closing the casket, he asks her if she has any last words to say, quiet enough for only a few in the front to hear. I cared not. That is not what I am here for.

The lid of the box closes, and he picks up the saw like it is the hand of an old friend he knows quite well.

“Now, ladies and gentlemen, watch as I turn this woman into a corpse!”

The crowd cheers. Oh, they cheer so loudly. My ears vibrate from people clanging the metal seats. Shut up, I

want to hiss, I will not be able to hear her scream.

The sorcerer places the saw atop the box and moves it forward, the noise like a zipper, echoing throughout the arena, sending chills down my spine. He moves it backward. Forward again. Backward again. Then the saw finally struggles a little, finding the skin, hugging the flesh, kissing the bone. Her scream is a shrilling one:

creaky from age but high-pitched from a pain resembling a warm hug—familiar and distinct, nostalgic and sorrowful. It is as if I can feel arms embracing my back, soft breaths tickling my neck, but there is something else, reminding me of a person no longer in my life. Every emotion I have felt in my entire life that had once begun with a smile or a sob or a laugh, floods in me all at once. Her screams are akin to that of a hand slowly creeping its way up my thigh, fingers twirling through my hair. Forward. Scream. Chills. Backward. Scream. Shivers. Forward.

Scream. Smile. Backward. Scream.

Laugh. I cover my mouth.

Until there is nothing.

Frankly, this is a far better ending than the previous act. The lion was having too good of a time and left blood everywhere on stage, dragging the body every which way only to leave a streak of red in its stead. I could smell it from the top of the stands while the stage crew spent at least thirty minutes wiping it up. Their efforts were wasted. After all, blood from the box is already dripping from the bottom. Now, the box is halved, and the sorcerer separates the two pieces to show the audience an abdomen cleanly cut, organs spilling out and bones clattering to the floor.

Oh, how red is my favorite.

The goosebumps and hairs sticking straight on my arms calm down. The high is gone, the familiar and distinct feelings of sorrow and nostalgia washing away, and I brainwash myself into thinking waiting thirty minutes for that was anticlimactic. I am not one for visuals. The organs and bones and missing limbs and chew marks do not appeal to me, not nearly as much as the sound people make before death. It is dramatic, flamboyant, and above all, their screams are not a result of the pain of the saw or the pain of the lion smashing its teeth against their leg. Inside each crevice of the screams, exist the pain of all they have had to endure while living. Poverty. Unrequited love. Low social status. Loneliness. A warm hug. They do not fear death, rather, they fear life. I do not need to hear their last words to know their reasons.

Their screams say it all. And those very same screams make me feel closer to them than I ever could even if I had known them my entire life.

The Circus of Miracles is for everyone: people who want to die and people who want to see them killed.

“Ta da!” the sorcerer cheers with a big smile on his face. Applause erupts from the arena, and some people cry at the touching act. Even the queen dabs her eye gently with a handkerchief blackened by her eyeliner. On stage, as the Saw Sorcerer bows, as the clean up crew scurries to begin the next act, as the audience cheers, the intestines that had fallen to the ground wrap around each other like worms caught in the web of the circus. A trail of corpses always follows the Circus of Miracles.

The living follow too. Silly ants.

Leah Maitland

I asked the moon if she felt insecure when she was full I prayed to her waning crescent form and dreamt that I too could one day grow to be concave to deplete to curl into myself and never have the contact of skin on skin on skin to forget the idea of chafing altogether to be the slightest sliver in the peripherals of vision cratered I clasped my hands together and wondered if slimness was the reason why I always saw her as smiling cheshire amongst the starlit in-between of disappearance silence I never heard an answer but I felt as she waxed warmth through my windowpane a swelling silvered halo punctuating the darkened skies bursting roundness unabashed a gentle hand cupping my waking cheek a resounding astounding celestial “no”

Liv Abegglen

It’s an hour’s drive out to the pool, but it doesn’t feel so long anymore. I make the drive after dark—the pool is a secret to my wife and Katie—and I’m so familiar with it I can drive it in my imagination.

I drive without music, out of respect.

I park the car in the overgrown yard of an abandoned high school, where the grass is high enough to obscure the headlights. I don’t bother to lock it, as nobody watches but the trees and a velvet black sky. The grass whispers as I wade, and with the flashlight of my phone I find the door with the broken lock I use to get inside.

Washed-out posters on decades-old white block walls are what greet me. I make it down the hallway to the room where the pool waits, and I give my phone a break. There’s a light in here, and it works, sort of, though it’s dim and flickering and I know someday it will fail.

“Hey, Jack,” I say.

I crouch and watch the surface. It ripples despite the stagnant air. It takes him a while to materialize, but when he does he meets my eyes. He’s in a constant state of dissolution, moving with the water, barely there at all. He’s a dark streak beneath the shining surface that reflects the room. The water is blue because everything else is: the minimal light spilling in through the broken ceiling, the dilapidated walls, the remnants of tiles.

I drop in a piece of candy that dyes the water. Next, an interesting rock from the backyard. Offerings.

A drop of water jumps where the rock fell in.

Jack doesn’t speak, but I know what he’d say if he could.

You’re late.

“I’m sorry,” I say. “Julia had a migraine last night, and Katie’s too young to be left alone. I couldn’t make it.”

I visit the pool each month on the twelfth, and this is the first time it’s had to be on the thirteenth. Jack is frozen, forever fifteen and some days, but time is real to him. The wait is real to him.

“I saw your favorite band live last night. It was a good show, Katie loved it. I guess I passed that gene to her. Sad without you though.”

There’s a moment of darkness before the lights sputter back to life.

“Those late nights hit harder when you’re old like me, heh. You’d like Katie. She’s becoming quite the tomboy. Sometimes I think she’d rather live outside.”

But together they will never play, because Jack is confined to the pool.

“I’m sorry,” I repeat, and I toss in a few of my old trading cards.

Leaving Jack is always hard, but I have to go before someone notices I’m gone.

In truth, Jack lives two places: in the pool and in my dreams. In my dreams I hear him breathe. Shuddering, as his lungs are half-full with water from the pool. He’s more of a feeling than a form. He has no face but when I wake it’s with his name on my lips and his presence aching behind my eyes. My wife Julia brushes hair from my face.

“Honey,” she says, “Katie goes to school in fifteen minutes. Are you feeling alright?”

I reassure her I am as I silence the alarm that had somehow failed to wake me. I ready for the morning, but there must be a bleariness in my eyes because Julia continues to watch from the doorway.

“Shit, I forgot,” she says.

“I’m fine. It’s just another day now,” I lie.

On this date, twenty years ago, I died.

Katie’s in the car and I’m joining her when Julie rushes out to me with an orange bottle in her hand.

“Jack!” she cries, “you have to stop forgetting these.”

I take the antiepileptics from her, swallow them down. On the drive

to school I try to bury the memories, but they always creep in.

Swimming alone, fifteen years old, late-night practice for the meet next week.

Losing consciousness. Coming to with burning lungs. Drowning.

Splitting.

I drop Katie off and she disappears behind the gates. I make it to the hospital next. Inside, I pass my coworkers on the way to my office and make only enough small talk to get them to leave me alone. The day begins on my computer, verifying prescriptions and answering messages. An hour later and I’m in the OR, scrubbed in and staring down the unconscious body of a patient. I wash the skin with iodine, painting its chest with a deep brown watercolor shade, but in a way nothing like how an artist might paint. This thing on the table is a project. Maybe when it wakes it will have a mind, but the anesthesia reduces it to a machine to be fixed.