Please note that the following is a digitized version of a selected article from White House History Quarterly, Issue 80, originally released in print form in 2026. Single print copies of the full issue can be purchased online at Shop.WhiteHouseHistory.org

No part of this book may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

All photographs contained in this journal unless otherwise noted are copyrighted by the White House Historical Association and may not be reproduced without permission. Requests for reprint permissions should be directed to rights@whha.org. Contact books@whha.org for more information.

© 2026 White House Historical Association.

All rights reserved under international copyright conventions.

the national celebrations explored in this issue have marked pivotal moments in American history. These occasions not only honor our past but also remind us of the long view of history, providing essential context amid our focus on the present. In an era dominated by the immediate, remembering these milestones fosters a deeper understanding of our nation’s resilience and evolution. The White House, as “the people’s house,” has served as a profound stage upon which so much of American history has been decided, directed, and determined—from declarations of war and peace to joyous commemorations that unite the nation.

As early as 1801, President Thomas Jefferson marked the Fourth of July by opening the White House to the public. Diplomats, officers, citizens, and Cherokee chiefs gathered in the oval saloon— today’s Blue Room—while the Marine Band played, setting a precedent for inclusive national commemorations.

In 1876, when the nation commemorated the one hundredth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, President Ulysses S. Grant issued a proclamation from Washington urging citizens to celebrate with gratitude for the Union’s preservation following the Civil War. Then the main festivities unfolded at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, the city where the Declaration of Independence had been signed. Grant and Emperor Dom Pedro II of Brazil inaugurated the event by activating the massive Corliss steam engine that

We Hold These Truths . . .

STEWART D. M C LAURIN PRESIDENT, WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

powered exhibits celebrating the nation’s unity and progress.

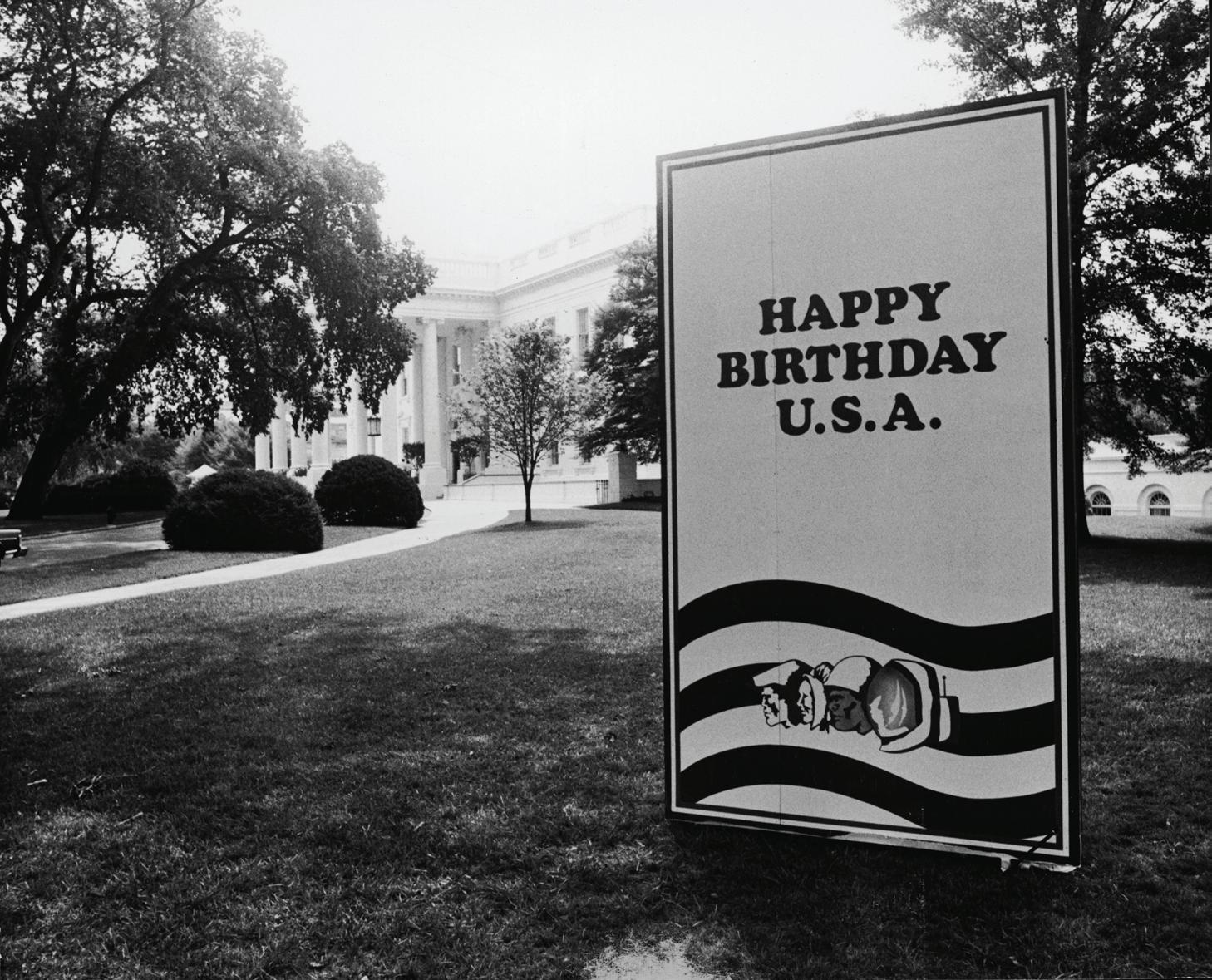

A century later, the American Bicentennial in 1976 amplified this spirit under President Gerald R. Ford. Official events peaked on the Fourth of July, with Ford addressing crowds at Independence Hall in Philadelphia. At the White House a few days later, a State Dinner hosted Great Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip in a specially erected tent in the Rose Garden, blending international diplomacy with national pride.

The two hundredth anniversary of the White House in 2000 was a grand affair under President

Stewart D. McLaurin, President of the White House Historical Association

In 1976, a giant birthday card on the North Lawn (opposite) wished a “Happy Birthday” to the U.S.A., and in 2009 (above), the public was drawn to President’s Park to watch a fireworks display. Such observances of Independence Day have been celebrated at the White House for as long as it has been home to the presidents. President John Adams moved into the White House on November 1, 1800. The bicentennial of his arrival was celebrated in 2000 with a reenactment of the occasion (right).

on Lawn (opposite) wished “Happy U.S.A., and public drawn to to watch a fireworks celebrated at the for as it has home the November 1, was occasion (right).

Adams successor, Thomas Jefferson, welcomed the public into the White House to celebrate the Fourth of July in 1801.

Adams’s successor, Thomas Jefferson, welcomed Fourth of

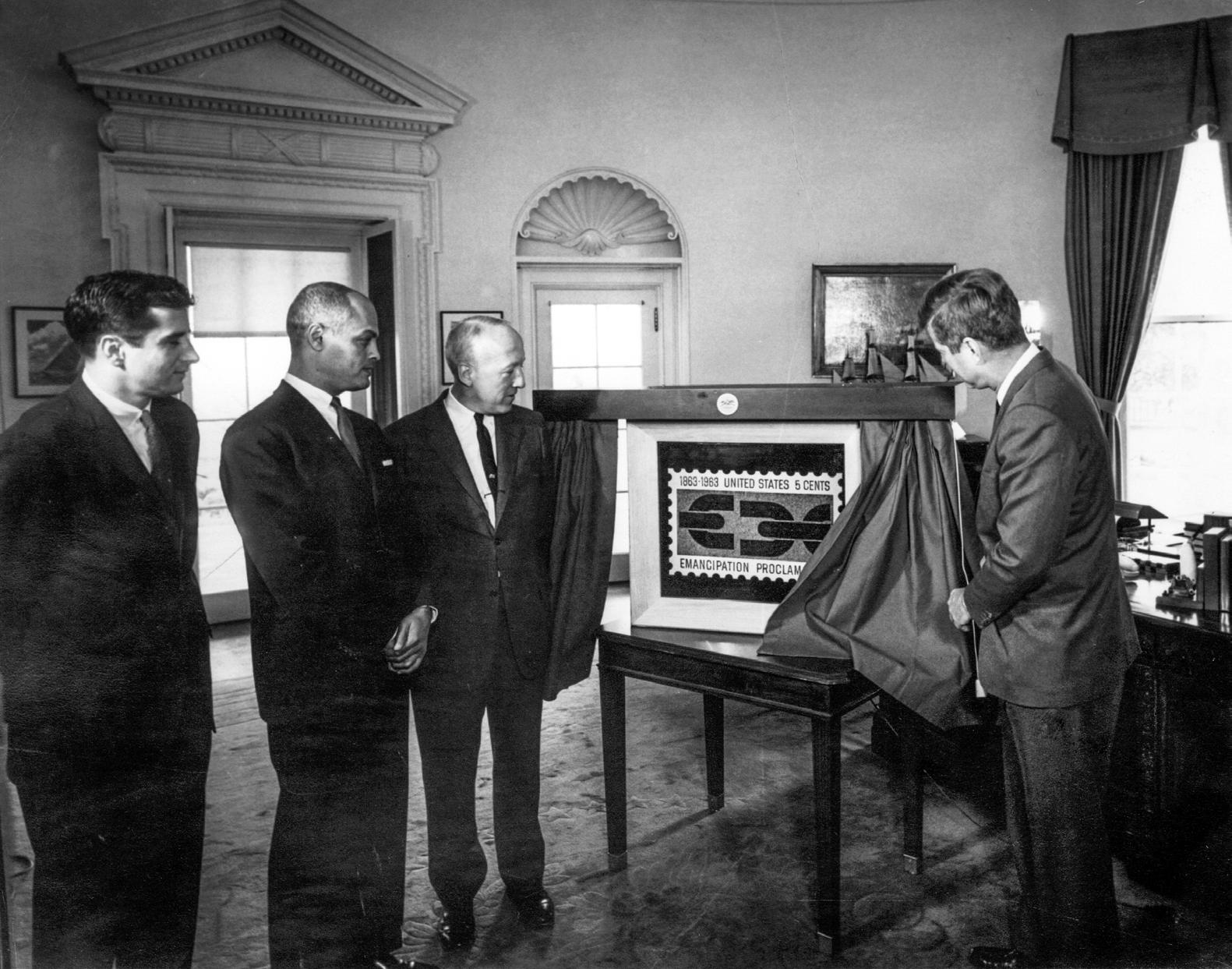

Whether it be a tree planting, an unveiling, or a royal visit, the ceremonial commemoration of milestones in American history are a long tradition at the White House. In 1932, President Herbert Hoover planted a cedar tree (above left) on the White House Grounds to honor the bicentennial of George Washington’s birth. In 1963, President John F. Kennedy unveiled a postage stamp (above right) to commemorate the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation. And in 1976 President Gerald R. Ford welcomed Queen Elizabeth II (left) to the White House for a white-tie State Dinner to celebrate the Bicentennial of American independence.

Bill Clinton. On November 1, a ceremony reenacted John Adams’s arrival, honoring the first occupancy in 1800. A formal dinner in the East Room on November 9 gathered former presidents and first ladies, reflecting on the White House’s history as a home, office, and beacon of democracy.

Beyond these commemorations, the White House has hosted numerous other anniversaries, transforming its halls into venues for national reflection and celebration. In 1932, the bicentennial of George Washington’s birth saw President Herbert Hoover chair the national commission and plant a commemorative tree on the White House Grounds. In the midst of the Great Depression, Americans were reminded of Washington’s leadership and enduring legacy in founding the republic.

The centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1963 brought a poignant reception to the White House under President John F. Kennedy. On the State Floor, leaders and guests honored Abraham Lincoln’s decree that freed enslaved people in Confederate states, blending solemn remembrance with civil rights aspirations during a turbulent era.

For the past sixty-five years, the White House Historical Association has stood as the dedicated keeper and teller of the stories of these commemorations, ensuring that the narrative of White House history endures for future generations. Our Association’s history is inextricably linked to the White House itself, beginning with its founding in 1961 by First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy. Motivated by a vision to preserve the Executive Mansion as a living museum, Mrs. Kennedy established this private, nonprofit organization to acquire furnishings, support restoration efforts, and educate the public about the White House’s rich heritage. Since then, we have published authoritative books, produced educational programs, and curated exhibits that bring to life the stories that began in 1792, when President George Washington selected the site for the President’s House and commissioned the young Irish immigrant architect James Hoban to design and build his vision. Hoban’s neoclassical creation became a home and office for every president to follow, testifying to the stability of the young republic. Just over a century after John and Abigail Adams became the first residents in 1800, President Theodore Roosevelt officially renamed it “The White House”—three words now associated

worldwide with American freedom and democracy. Through our work, we illuminate how this building has evolved from a modest stone structure into a global emblem, surviving fires, reconstructions, additions, and the weight of history. The building itself has changed over time: porticoes and wings have been added to accommodate growing needs, the entire interior was rebuilt during Harry S. Truman’s presidency to address structural failings, and the president’s office has migrated from the Second Floor of the Residence to the West Wing, culminating in the iconic Oval Office—whose name is now synonymous with the presidency itself. These adaptations reflect the practical demands of governance while preserving the mansion’s core dignity.

As the White House Historical Association marks more than six decades of stewardship, we continue to expand our reach through innovative programs, such as The People’s House: A White House Experience and our digital archives and digital classroom resources. Together with our books and the Quarterly you hold in your hands, these efforts ensure that the stories of Hoban’s architectural drawings, Adams’s arrival, Roosevelt’s naming, and national commemorations remain vibrant. They remind us that history is not merely recorded but lived and shared. By preserving artifacts, funding restorations, and fostering scholarship, we bridge the past with the present, inviting all to appreciate the White House not just as a residence but as the heart of American democracy.

This issue of the Quarterly highlights America’s commemorations. Why observe these occasions? They connect us to the sacrifices and triumphs that shaped America, offering perspective beyond the “now.” The White House, as the epicenter of these moments, reminds us that history is not static but a continuum through which decisions echo across time. In remembering, we gain wisdom for the future, ensuring the White House remains a living testament to our shared story.

As we begin the American Semiquincentennial, we embark on a year of celebrations and commemorations. While the White House and the people who have lived in it have changed over its 226-year history, the purpose and standards it upholds have stood the test of time, embodying the unyielding spirit of American freedom and democracy. And so it shall continue.