Welcome to the newest edition of Western Hunter Magazine. I have been waiting six months to write that line! Even though you are only on page 4, you can already feel some of the changes; even the paper is different. The one thing that has not and will not change is the original content that has always set Western Hunter apart from other publications.

For 25 years, we’ve done more than just tell hunting stories; we’ve told the whole story of the hunter. Western Hunter has always aimed to entertain, educate, and inspire, but we’ve also taken bold steps that others wouldn’t, tackling topics like skin cancer, mental health, suicide prevention, and nutrition, because hunting is just a part of who we are. Through gritty adventure stories, honest gear reviews, and thoughtful takes on current events, our mission remains the same: to celebrate and preserve the legacy of the western hunter.

Western Hunter is part of a family of companies that includes Wilderness Athlete, Outdoorsmans, and The Western Hunter TV. Within this family, we have a motto of “improving our customers’ lives every damn day.” That phrase underlies each decision we make regarding our products and customer service, and it guides our team as we build each issue. By the time you reach the last page, I hope this first page makes even more sense. By the way, when I talk about “being different from other publications,” this does not come from a spirit of competition. I currently subscribe to nine different hunting-related magazines, not because I am trying to keep up on them, but because I truly want to read them and, hopefully, learn something new. Your subscription to Western Hunter is $40 per year and includes access to over 120 episodes of Western Hunter TV. We can all agree

You burned a lot of points on some good hunts last year, do you plan to restart the point-building process in states, or are you going to start doing more lower-point hunts in those states?

My application strategy is based on two important facts. First, I am 62 years old, so I am only looking at hunts that I can draw in the next 5-10 years. I would like to think I will still be able to handle difficult hunts into my 70s, but I am not counting on that. Secondly, I love to hunt and want to spend as many days in the field as possible, so I am willing to take my chances on what may be perceived as a low-quality tag. Last year, I had tremendous success with this philosophy, but I realize that it is unlikely I will ever be able to duplicate that. I’m okay with that, and I will be in the field giving it my best and enjoying every moment.

You have been a pretty religious 6.8 Western guy in recent years. What is it about that you like so much? Do you foresee yourself changing from that anytime soon?

The 6.8 Western checks every box for western hunting. The heavy-for-caliber bullets (up to 175 grains) launching around 2900 FPS deliver plenty of energy for big game, with very manageable recoil. I have hunted with multiple 6.8 Western Browning X-Bolts since the cartridge was intro-

BY CHRIS DENHAM

that amounts to pocket change in today’s world. When you hold each issue of Western Hunter, we want you to feel like it was not pocket change, but instead, it was money well spent.

I met Wayne Carlton 35 years ago, and to this day, he is still one of the most creative and inspiring people I have ever met. A few years ago, I drove to his Colorado home and hunted with Wayne and his son Marc. Even ravaged by the symptoms of advanced Parkinson’s disease, his sense of humor was still fully intact as we talked about “the old days.” While one article cannot encapsulate the life of a legend, Marc lets us into their family kitchen in this issue.

Speaking of legends, Randy Ulmer is back! Randy has been fighting his own battle with cancer. His ongoing series, starting with this issue, is as personal as anything I have ever read. We are honored, and I mean honored, to have his contribution. Grappling with your mortality is scary; letting the world in on your battle takes courage and humility. I ask that you don’t just read this series but truly ponder it and make yourself the main character of this story as well.

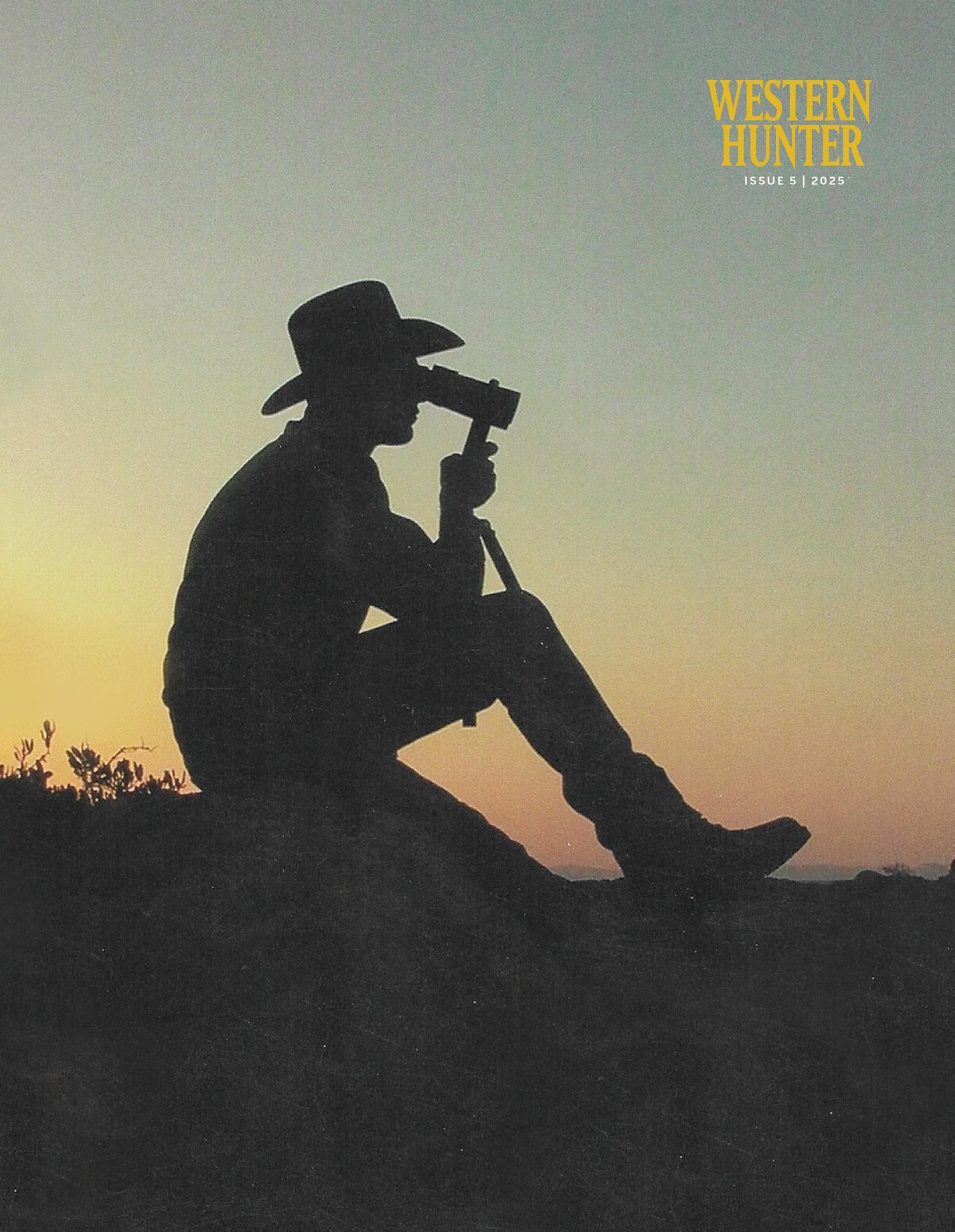

Every time I look at this cover, I’m reminded just how far we’ve come, and how many people made the journey possible. Each issue brings together 30 to 50 voices, stories, and perspectives. Do the math, and that’s over 6,000 contributors who’ve helped shape what Western Hunter is today. But numbers only tell part of the story. The truth is that you, the reader, are part of this legacy too. Every time you take something from these pages and apply it in the field, whether it’s a tactic, a mindset, or a moment of reflection, you validate everything we do. That’s the real reward. WH

duced, and all have been extremely accurate (under one MOA with factory ammo). The 6.8 Western may be a dream come true; excellent accuracy, plenty of energy, and pleasant to shoot.

You’re known for your “Chris Denham” Breakfast Mash Ups where you throw everything and the kitchen sink into a big pan for breakfast, and it comes out amazing, but when you’re on the road for 40-60 days per year, what’s a normal breakfast look like, assuming you don’t have a ton of time? All of my best hunting camp meals seem to start with bacon, onions, and peppers. With those basic ingredients, it doesn’t really matter what else you put in the pan; it is going to taste good! On early-season deer and elk hunts, breakfast usually comes after the morning hunt, so everyone is good and hungry. A balanced meal with plenty of protein and quality carbohydrates is always my goal. So, eggs, bacon, and sausage for fats and protein, combined with sweet potatoes, red potatoes, or my wife’s homemade bread, lightly fried in butter.

Folks have watched you hunt all over America for what seems like every species in every environment, but what’s one place or one animal that you really want to hunt? Honestly, my checklist is complete. But I would really like to hunt in Hawaii again; the scenery

and the hunting community there are exceptional, plus, the weather is pretty nice too. If I had one wish, it would be that I could hunt every species in Arizona every year. I truly love my home state.

From traveling around the country as a rep to now traveling around the country to hunt, where have you found the weirdest people to live? What about the nicest?

Alaska is hands-down the winner for the strangest people! In my opinion, people who don’t quite fit in down here in the lower 48 end up in Alaska, and they’ve been doing that for 100 years. But that’s exactly what I love about them. And they are proud of their uniqueness! I’ve traveled all over Alaska on nine different trips, and the people never cease to amaze me with their individuality and adventurous spirit. Wyoming would get my vote for the most polite people. I wouldn’t call them all “nice,” but they are respectful and look out for each other.

Got a question of your own?

Send us your queries to info@westernhunter.net and you might see them answered in a future issue.

Browning redefines Total Accuracy yet again with the new X-Bolt 2 and Vari-Tech stock. This new stock design is engineered with three-way adjustment that allows you to customize the fit of the rifle to meet your specific needs, helping you achieve consistent, tack-driving performance while retaining the silhouette of a traditional rifle stock.

Internal spacers lock in length of pull. Adjustable from 13-5/8" to 14-5/8" right from the box, this system is sturdy and rattle free. LENgth of pull

Two interchangable grip modules are available for the Vari-Tech stock: The traditional Sporter profile and the Vertical profile. Both let you optimize finger-to-trigger reach and control.

Achieve consistent eye-to-scope alignment and a rock-solid cheek weld even with large objective lens optics. Six height positions offer 1" of height adjustment. COMB HEIGHT

“Our ability to perceive quality in nature begins, as in art, with the pretty. It expands through successive stages of the beautiful to values as yet uncaptured by language.” ~ Aldo Leopold

The Big Picture

BY CHRIS DENHAM

It was 2002. There was no Facebook, no YouTube, no Instagram. The iPhone was still five years away. America was reeling from the aftermath of 9/11, the dot-com bubble had just burst, and unemployment was sky-high. It wasn’t exactly a great time to start something new. Marketing options for small businesses were limited, expensive, and often out of reach, especially for a company selling high-performance, high-dollar gear with razor-thin margins. Even keeping basic inventory on hand was a major financial stretch. But Floyd Green, owner of Outdoorsmans, isn’t the type to back down from a challenge. Instead of waiting for better times, he created his own advertising tool: a magazine.

“We rolled the dice, poured in every dime we had, and launched Season 1 of The Western Hunter.”

At the time, desktop publishing was exploding. Thanks to Apple and Adobe, a determined graphic designer could lay out a full magazine on a single machine. Enter Clay Delcoure. He was just 20 years old, fired up, wildly determined, and completely untrained in graphic design. He had never done anything like it before. But what he lacked in experience, he made up for in stubborn grit. With guidance from our friends Rusty and Lesa Hall, owners of Trophy Hunter Magazine, and more than a few brutally long days, Clay somehow pulled off the first issue of Western Optics Hunter in the fall of 2002.

We called it a “matalog,” a mix of magazine and catalog. Outdoorsmans had just launched the first lightweight hunting tripod ever made, and we needed to get the word out about this revolutionary product. Premium optics were our bread and butter, but this new gear changed the game. Back then, we could still purchase hunter mailing lists from several western game departments. So we built our strategy around that concept: mail the magazine, free of charge, to hunters who applied for big game tags in multiple western states. These were serious hunters, the kind who would recognize quality gear when they saw it.

So that’s what we did. Outdoorsmans produced, printed, and mailed over 30,000 copies of Issue One, completely free. No paid advertisers, no subscribers, just a bold leap of faith. It was a massive gamble, especially during uncertain economic times, but Floyd believed in the plan, and it worked. Western hunters were hungry for information on cutting-edge gear, and their response proved we were onto something.

I wrote an article for each issue and served as an advisor to Clay, whom I had known since junior high. After a few years, Clay decided it was time to get serious about his education and wanted to enroll in college full-time. “Working from home” wasn’t really an option back then, so Floyd and I sat down to figure out a plan for the magazine’s future. We decided to spin it off into its own business, and I would take over as editor.

There was just one problem: I had almost zero computer skills. My first move as editor was to find a graphic designer. Through my conservation work, I had met Randy Stalcup, who had formal design training and was working at an ad agency. He was also a serious hunter, which made him a perfect fit. Randy jumped at the chance to help build the magazine as a side gig. That was over 20 years ago, and to this day, he is still our lead designer. With Randy on board, everything leveled up. The magazine went from simply functional to visually sharp and even more effective. Before he even wrapped up his first issue, Randy pulled me aside and said the title Western Optics Hunter was just too much for a cover. He was right. We shortened it to Western Hunter, and with that small but meaningful change, a new era began. Not long after, privacy concerns started changing the game. One by one, western states stopped selling hunter mailing lists. We held on for a while, but eventually the quality of our list dropped off. It became clear we could no longer rely on that strategy. So, we pivoted. We became a true magazine, offering subscriptions, selling ad space, and finding new ways to reach our audience. It wasn’t easy, but it forced us to grow up fast.

Mike Duplan had been a friend and trusted mentor for many years. Some of his photos appeared in our earliest issues, and one day he called with a new idea: start a second publication, Elk Hunter Magazine. I knew right away this was outside the limits of my self-taught editing skills, so I brought in Ryan Hatfield, a trained and experienced editor. With Ryan handling content and editing, I was finally able to shift more of my focus to marketing and sales.

We launched Elk Hunter Magazine alongside a refreshed Western Hunter in late 2011. We published four issues of each title every year. For a threeman team, that was a tall order. Then, Ryan pitched what I thought was his worst idea yet: a TV show. Every hunting show I had seen was campy, overproduced, and honestly, hard to watch. I wasn’t interested–until he told me Nate Simmons was available.

I didn’t know Nate well. We had crossed paths once or twice, but everyone who knew him had nothing but respect for his work and who he was as a person. That was enough for me to give it a shot.

The pilot episode that Nate’s team produced blew me away. We started drawing up contracts with the Sportsman Channel. We rolled the dice, poured in every dime we had, and launched Season 1 of The Western Hunter.

The response was immediate and bigger than we expected. Nate and his partner, Randy Rockey, had the rare ability to turn a simple deer hunt into an unforgettable story. The visuals, the music, the pacing–it all just worked. The technology has changed, but 13 years and over 150 episodes later, the

formula is still the same. We drive our own trucks, set up our own camps, cook our own food, hunt on our own, and pack out our animals, just like the people watching at home.

Our contributors have always shared that same philosophy. They are not professional writers. They are serious hunters with real-world experience and a passion to share what they have learned. People like Randy Ulmer, Remi Warren, George Bettas, Zach Bowhay, Kristy Titus, Mike Duplan, Nate Simmons, and dozens more have helped make this whole thing work. They pay to hunt; they don’t get paid to hunt. That distinction matters.

For six years, we kept grinding, producing eight magazine issues and 13 TV episodes every year. But by the end of 2016, Elk Hunter Magazine was ning on fumes. We found ourselves covering the same ground and reold topics. In spring 2017, I made the call to fold Elk Hunter into Western Hunter and shift to six issues a year. Looking back, I am still not sure it was the best business move, but it gave us more time to focus on each issue and made the content better.

Today, our team runs four companies: Western Hunter Magazine, The Western Hunter TV, Outdoorsmans, and Wilderness Athlete. Each of them has grown and brought new talent into the fold. Earlier this year, we decided it was time to give Western Hunter Magazine a full-scale remodel, not just a facelift, but a complete rebuild. You are holding the result of that effort in your hands.

To say the world is changing fast is an understatement. With AI tools, anyone with a laptop can look like an expert. But we have built this brand on something real, and we intend to keep it that way. Hunting is about as real as it gets. Sure, we have gear our grandfathers could not have imagined, but the soul of it has not changed. We still draw tags. We still count the days to opening morning. We hike into the mountains with hope in our hearts and camp on our backs. That part is timeless.

And I hope to God it stays that way. WH

“We hike into the mountains with hope in our hearts and camp on our backs. That part is timeless. And I hope to God it stays that way.”

BX-4 PRO GUIDE HD

EDGE-TO-EDGE CLARITY FOR ALL-DAY GLASSING

Deep in northern Nevada’s high desert lies the Independence Mountain Range.

These rugged peaks sit within the Carlin trend, a 60-kmlong strip considered the most important gold-producing area of north-central Nevada. Once hallowed ground for the Shoshone, for centuries this has remained a place for sustenance and spiritual practice.

More recently, the range’s looming, craggy escarpments have served as a beacon for miners seeking fortune and gold. Needless to say, this place is rich in history.

Now, with tough draw odds and solid trophy potential, the Independence Range is, again, a highly sought after place for hunters–those of us who seek fortune and spirituality of a different kind.

Fleece has been the go-to mid-layer for hunters this century. Previously, it was wool, and previous to that, it was the skun hide of the last critter you killed. Now, synthetic hybrid jackets dominate the market. This new jacket from First Lite is the latest version to hit the market, and with its extremely weather-resistant face and quick-drying insulation, it checks all the boxes for nearly any western hunter.

FirstLite.com

A sun shirt is a sun shirt is a sun shirt. Sure, but some of them suck. Many are way too heavy and accomplish the goal of getting your skin out of the sun but leave you soaked in sweat. This new piece from SG gets you out of the sun, but it also keeps you cool and stink-free thanks to Polygiene.

StoneGlacier.com

Most people don’t think about passing down a shooting bag to their kids, but that’s because they haven’t seen one of these bags. It’s basically a work of art, even though the name is extremely long for a leather bag full of beans. Oh, and it’s great for shooting off of.

ArmageddonGear.com

A 12-power binocular is normally a great happy medium for a guy who wants to be able to handhold his binos out of the truck as well as set them on a tripod and digest a landscape for hours. The SFLs not only fill that niche, but they also don’t break the bank, fit in any average-sized bino harness, and punch well above their weight class when it comes to glass quality. Think Swarovski EL, but maybe a little better.

Outdoorsmans.com

The yellow wrench that you keep in your range bag, which now only has two out of the ten bits it came with, is tired and begging to be replaced. This wrench allows you to be more precise with your torque specs and allows you to use a ¼" wrench for when you really need some extra leverage. VortexOptics.com

This is not a sexy piece of equipment; it’s a couple of pieces of .51 oz/sq yd Ventum Ripstop Nylon sewn together with 900-fill Muscovy down in between. What that means is it’s extremely light, ultra-packable, and will keep you warm in just about any situation. A quality sleeping bag doesn’t need useless features to do its job. ZPacks.com

Skeletonized rifle chassis have been around for several years, but they’ve always been on the heavier side for hunters. MDT changed that with this chassis. You get all the benefits of a chassis-such as the ability to have a folding stock, ARCA forend, and a vertical grip-without adding any additional weight to your rig. The chassis is rigid enough for any cartridge and will be a staple for guys building lightweight rifles for years to come. MDTtac.com

BY JAKE HAVLICEK

“Are you still afraid of heights?”

“Uhhh, yeah?”

“Well, it’s looking like I might not be able to go to Alaska for my mountain goat hunt... and I was thinking of sending you.”

That was the conversation I had with my boss, Steve Speck, just three weeks before I headed out for a mountain goat hunt in Southeast Alaska.

Many of you may recognize Steve’s name. He has been in the hunting industry for years and has helped build several notable brands, including S&S Archery, Pure Elevation Productions, Solid Broadheads, and, most importantly, Exo Mtn Gear, where we design and build pack systems for backcountry hunting. Steve has been a huge influence on me and has done more than most would for a young employee, including sending me on this once-in-a-lifetime hunt.

In 2024, Steve had planned three Alaska hunts–caribou, moose, and mountain goat–with the goal of capturing them all on film for a new video series we called The Experience Project (available on our Exo Mtn Gear YouTube channel). After successfully completing the caribou and moose hunts, he had to sit out the goat hunt due to business obligations. That’s when he asked if I was still afraid of heights.

Despite my lingering fear of exposure and vertigo, I said yes. It’s not the kind of opportunity you turn down.

I’ve struggled with a fear of heights for as long as I can remember. My dad has it even worse, so I’m pretty sure it runs in the family. For me, the feeling hits when I’m on open slopes without trees or cover–the kind of country mountain goats live in.

I had three weeks to prepare. Every day after work, I strapped 40 lb to my Exo pack and hiked the local hills. My goal was to show up in the best shape possible, mentally and physically, knowing I’d be pushing my limits.

I flew to Southeast Alaska with two of my coworkers: Mark Huelsing, who also had a goat tag, and Justin Nelson, who would be documenting the hunt on camera. Weather delays forced us to take a ferry to our final destination, which gave us our first look at the terrain. The mountains were steep, rugged, and intimidating. As we cruised past them, my stomach turned, but I knew I’d have to get comfortable with being uncomfortable.

Once we landed, our guide, Mark Rowenhurst of Limitless Alaska Guiding, picked us up and brought us to his cabin. We got settled in, checked rifles, reviewed our game plan, and packed our gear.

This was uncharted territory for all of us, including our guide. He had picked out a remote spot he’d never been to before. I’ve packed for backcountry elk, mule deer, and moose hunts, but Southeast Alaska goat hunting is another level. Rain gear wasn’t optional–it was essential. I was told I’d only need one pair of pants: rain pants. Everything was recommended to be synthetic to avoid soaking up moisture. We debated crampons, reviewed gear one last time, and packed carefully. My pack weighed in around 80 lb.

We woke early the next morning and started shuttling up the river in a small boat–four guys and a pile of gear. Eventually, we reached our jumping-off point and set up a base camp near the river. We had enough daylight to glass, so we started picking apart the terrain. We spotted some nannies and kids, along with a few lone goats we assumed were billies–too far to confirm, but promising.

The next morning, we hiked 1.9 miles and gained 2,700 vertical feet through thick brush and timber. It took nearly six hours. The spot we had marked on OnX turned out to be the only flat area around–just big enough for a couple of tents. We spent that evening glassing, spotting a few goats across the basin. We planned to go even higher the next day.

At sunrise, we emptied our packs and left camp light, climbing another 1,200 feet. The higher we went, the sketchier it got, especially for someone like me who doesn’t do well with heights. We traversed around a bluff that made my knees wobble. I was grateful to have Mark and Justin there for encouragement as I picked my way across.

Eventually, our guide Mark stopped and whispered, “Goats.”

Two billies, standing about 300 yards away, skylined against the slope. Justin set up the camera and confirmed what we suspected–Roman noses, thick horns, large scent glands. No doubt. Billies.

We quickly discussed options. Should we try to shoot both, or take one and hold off? Weather was coming in, and our guide was concerned the river could drop too low for extraction. We never made a firm decision. We just dropped our packs and got into position.

Mark had already insisted I shoot first. That’s the kind of hunting partner he is–selfless.

I found a good prone spot and began getting steady, ranging, dialing, dryfiring, and adjusting for wind. I wasn’t focused on which billy I wanted–just whichever one gave me the best shot.

I looked left at Mark. “I’m going hot.”

Then I glanced right at Justin. “You rollin’?”

He gave me a nod. I chambered a round, clicked off the safety, settled into my breathing, and squeezed the trigger. Impact. The billy dropped immediately. I stayed in the scope, ready for a follow-up, but it wasn’t needed.

Emotions started to rise–I had just shot a mountain goat. Then I noticed the second billy standing from his bed, looking down toward the one I had just dropped. Our guide’s voice came through quietly, “You can shoot the other if you want to, Mark.”

A few seconds later, Mark squeezed off a shot. His billy dropped in its bed. We looked at each other in disbelief. Two goats. Two clean shots. One unforgettable moment.

We high-fived and hugged, but knew we had work to do. As we climbed to the goats, we hit the snowline around 4,000 feet. I started getting dizzy again–the steep slope and exposure triggered my vertigo. I had to sit down, eat, and drink before I could safely move again.

Eventually, I laid my hands on my goat–a moment I’ll never forget. We snapped a few photos, then got to work quartering and packing. With just over an hour of light left, we loaded our packs, each of us carrying part of both goats, and began the descent.

That hike back to camp was brutal. Thick brush, uneven footing, and navigating in the dark made it slow going. We didn’t roll into camp until well after dark. We ate, talked about the day, and tried to rest–because the hardest part was still ahead.

We woke to colder temps and snow. The mountains were covered, and the trail was slick. We packed up, loaded our heavy gear, and began the long descent to the river.

It was one of the hardest packouts I’ve ever done. Falling multiple times in the brush, struggling to stay upright on slick slopes, and trying to beat the daylight added to the challenge. Eventually, we made it down.

We loaded the boat again and started the shuttle. The water had dropped noticeably since we went in, and new stumps had appeared in the channels. While navigating one of the tight stretches, our guide made a last-second decision. Too late. We hit a submerged stump, hard.

The impact threw Justin out of the boat. I reacted fast and grabbed his legs before he went under. It could’ve gone bad in a hurry, but we got him back in and made it the rest of the way without further incident.

Back at the cabin, we checked our goats in with Alaska Fish & Game. The biologists were impressed–my goat was aged at 12 years old, which they said was rare. Most billy goats they see are 8-10. As it turned out, I was our guide’s youngest client, and that goat was the oldest he’d ever packed out.

This hunt pushed me out of my comfort zone in every way–mentally, physically, and emotionally. From exposed climbs to intense weather and long days under load, I was challenged at every turn. But I’m grateful that I said yes.

Sometimes the best memories come when you lean into discomfort and say yes to something that scares you. And lastly, thank you again to my boss, Steve Speck, for sending me on this hunt. WH

COMPACT SPOTTER WITH OPTICAL IMAGE STABILIZATION™

Meet the OSCAR6™ HDX PRO — the most advanced image-stabilized spotting scope ever built. Powered by SIG SAUER’s next-gen OmniScan™ Optical Image Stabilization, a digital accelerometer kills shake in real time. Pair that with our most advanced HDX PRO™ glass system the OSCAR6 delivers rock-solid clarity no matter the conditions.

It’s not just a spotting scope. It’s a force multiplier.

BY MARK “COACH P” PAULSEN

Much has been written about the importance of fitness for the modern hunter. Multiple podcasts, websites, and countless individuals are currently dedicated to guiding and instructing in all things pertaining to backcountry fitness. This attention to fitness is a wonderful thing, since it pays dividends not only for the actual hunt but for a better life in general.

It appears that the days of Gordon Eastman trekking through the Yukon in a pair of blue jeans and a cowboy hat are over. And to some degree, I miss it. Not Gordon per se–although I have much admiration for Gordy–so much as the simplicity of his approach, drive, and determination.

Certainly, times have changed for all of us, and most things have evolved to the benefit of safer and more enjoyable hunting. Most of you remember picking up topo maps and using your woodsman skills to navigate between peaks and drainages. Now, with the push of a button, the map systems on your phone bring all things unnerving into a more manageable perspective.

I must admit–I like the new system better.

My admonition today is not to try and turn the clock back on any of the current technology that we’ve all come to know and love. It’s simply to remind you that mental toughness plays a key role alongside fitness, and I pray that we never get to a point where that rugged spirit is lost or marginalized.

So let me ask you–how tough do you think you are between the ears?

Since you can’t really quantify toughness, that is probably a difficult question to answer. You just know it when you see it.

Now to be sure–paraphrasing John Belushi–“Tough and stupid is no way to go through life.” And there’s no doubt, tough can get you killed if you don’t balance toughness with intelligence. But most of us stand in awe of the folks who just flat out consistently get things done

Decades ago, I stumbled across a formula that I’ve never forgotten due to its simplicity. The formula came to me through a lecture by an 85-year-old lady named Cheryl Adams.

Cheryl was a wild child–an orphan surviving on her own in the mosquito-infested swamps of Florida from a very young age. She pulled herself up through grit and toughness and went on to raise nine children while serving as the lead secretary in the White House under four Presidents, starting with Harry Truman.

Talk about tough. And I never forgot her words:

DESIRE = ENERGY ÷ PURPOSE

What exactly does that mean?

Well, if I’m asking you to train your brain for mental toughness as well as your body, there needs to be sufficient motivation in your wheelhouse to accomplish the task.

Allow me to serve up a scenario that might help you understand:

Let’s say I come home from putting in a long, tiring day at work and I’m bushed. So much so that I just want to sit in my La-Z-Boy and try to forget about the last 12 hours. So tired that I don’t even want to turn on the TV. Please–no one talk to me. I’m gassed.

“I DON’T LOOK FOR THE MOST TALENTED GUY IN THE DRAFT, I LOOK FOR THE TOUGHEST.”

– Bill Belichick, former New England Patriots Head Coach

Let me frame it another way. Which hunter would you rather take into the woods?

A) A fit hunter who is mentally soft?

B) An unfit hunter who is tough as nails?

Not sure what your answer would be, but mine would be B

So what’s my point?

Simply this: as you take time to physically prepare your body for the hunt, don’t forget to challenge yourself mentally.

Are you mentally prepared to pack out moose quarters?

Are you mentally prepared to drop into a canyon after a bull, knowing what a dead bull would mean?

Are you mentally prepared to spend the night on the mountain?

Prepare your brain for toughness like you prepare your body. Run through potential scenarios in your head–good and bad–and address any potential problems before they happen.

Navy SEALs are trained under extreme conditions to control their blood pressure and emotions and think things through. Emotions affect clear thinking. You might take a page from their playbook. It’s been my experience that the tough guys I’ve come to know, like SEALs, don’t get rattled easily. They navigate difficult situations and keep their cool.

Physical and mental toughness, it seems to me, is being systematically removed from our society. But we don’t play by the rules of a soft culture. Just like stupid can get you killed, mentally soft can get you killed.

So how do you mentally fund this added piece of the puzzle?

Easy. You just have to want to.

Then, my cell phone rings. My spouse runs to pick it up before me so as not to disturb me. Didn’t work. I put the device to my ear and say, “Hello.”

The voice on the other end launches into an excitable diatribe that results in me vaulting out of my chair and yelling to my wife to throw something on a plate for me to eat in the truck.

Unbeknownst to her, my hunting buddy Bob just called to tell me that one of their hunters backed out on an elk hunt in a great unit–and the hunt starts tomorrow. Bob said that if I can meet him at the gas station in the morning in Pagosa Springs, the tag is mine.

“Count me in!” I excitedly respond.

Sure, it’s an eight-hour drive and it’ll take me an hour to get out of the house–but I can do it. It was as if a triple espresso was just injected into my veins and the meaning of life became crystal clear.

Five minutes ago, I was despondent. Now, I’m alive.

DESIRE = ENERGY ÷ PURPOSE

In this scenario, my desire was always there–I love to hunt. The purpose came in the phone call. And with that came the necessary energy it would require to pull it off.

If you are going to toughen up, you have to have enough desire to make it happen. To train for mental toughness, simply tap into the ultimate fuel source–your brain.

Back when I was coaching young men and women around the country, I always emphasized: “If you motivate the mind, the body will follow.” Or, put another way, “Your head creates your world.”

We humans have a tremendous capacity to suffer if we have a passion for something. You simply need to identify it, bottle it, and use it as the daily inspiration you need to get better–physically and mentally.

You should look at it as another challenge to improve yourself. And strangely enough, that’s where the fun is.

So, let me encourage you to identify your desire. Tap into the inherent power it provides. Continue to work on your fitness, for sure, but build in some mental toughness training and go write the next chapter of this everevolving process called life.

Long may you run. ~ Coach P

BY BRODY LAYHER

In 1992, Leica invented the world’s first laser rangefinding binocular. It was a large, blocky optic with no hinge to change your IPD (eye width) and would absolutely not fit in any modern binocular harness. If you’ve ever seen a pair of Pulsar thermal binoculars, they resembled those in many ways. The Geovid 7x42 BDA was jet black, featuring the classic red Leica logo in the lower right-hand corner. Leica must have been pretty happy with that name and design because 33 years later, they’re still using both. That is, until the Geovid Pro AB+. Instead of the classic black, they’ve gone with a beautiful shade of baby-poo brown. They’re not the most pleasant binoculars to look at, but much like their great-grandfather, they are innovative.

The “AB+,” as I have come to know it, features the same chassis, glass, display, and app as its predecessor, the Geovid Pro, with two major upgrades: Applied Ballistics Elite built-in and new software called Shot Probability Analysis (SPA). The “AB” part allows you to skip the $3.99 per month for Applied Ballistics Elite. SPA gives you the ability to see what your first round impact probability is on a variety of targets at any yardage, in any condition.

Now, SPA may not seem like something you need or would ever use, but once you start to mess with it a little, it can be a great tool for comparing different bullets, calibers, and cartridges. SPA can also give you an important wake-up call when it comes to figuring out why you may have missed an animal or target. I can tell you for certain that it’s made me a better shot and not because it’s physically helping me in any way, but because it’s telling me I am the problem and not the gun.

As I mentioned above, the meat and potatoes of the binocular are the same as the 2023 released Geovid Pro in the 42mm objective model. The glass in them is great for a rangefinding binocular, but it is not as easy on the eyes as something like a Noctivid or NL Pure. The edges can have a slight blur, but anytime you add a display to the barrel of a binocular, you’re going to degrade the image.

The Leica Ballistics App has seen tons of updates in the past few years. It’s gone from a clunky, crashing nightmare to an easy-to-use, intuitive masterpiece. I can easily add different ballistic profiles, change settings in the binocular, and make accurate wind calls using the HUD feature.

It’s hard to speak on the durability of a binocular after only six months of use, but so far, so good. I dropped them off of a tripod at sitting height

and it does look like the focus wheel might have bent slightly, but nothing has changed on the binoculars. They still focus without any issues. I stuck them in the freezer for a couple of hours to see how they handled the cold and, short of a low battery sign, (which is a flashing reticle indicating you have 50 ranges left before the binocular dies... yeah, maybe not the best way to show that) they still functioned quite well. Normally, I would expect to see the ranging and solutions to lose some speed, but that wasn’t the case.

The AB+ has onboard temperature and pressure sensors just like its predecessor to ensure you get the most accurate solutions possible. After the aforementioned freezer time, when I checked the temp on the HUD in the app, it matched my Kestrel, which I trust. The one issue I did notice is that it took a long time for the optic to read the correct temperature once removed from the freezer. I could only see this being an issue if you’re doing something like truck hunting in eastern Montana in November. If that’s the case, maybe take a click or two off your data.

Overall, I think this is one of the top three rangefinding binoculars on the market. They may not be the prettiest binoculars to look at, but they will absolutely allow you to find your target, give you an accurate range, and show you a correct solution. WH

TECHNICAL SPECS:

Magnification: 10X Objective Lens Diameter: 42mm

Battery Type: 1 x 3 V / Lithium-type CR2

Battery Runtime: Approximately 2,000 Measurements

Weight: 34.2 oz Dimensions: 4.6" x 6.0" x 2.8" Cost: $3,849

Learn More: Outdoorsmans.com 1-800-291-8065

Scan to watch my full video review of the Geovid Pro AB+ and get a taste of how SPA works.

BY CHASE HARRIS

This deer season was short and sweet–a few incredible days packed with adventure, set in some truly remarkable country. My wife, little brother, and I drew amazing tags and were fortunate enough to harvest three incredible bucks! But the story of how this season came to be actually begins back in 2020.

Four years ago, my father, wife, brother, and I drew the same tags as a party. Riding the high of that rare luck, we launched into a season of intense scouting. My dad and I e-scouted and camped nearly every weekend, trying to learn every detail of the unit. Each trip turned up countless bucks and only fueled our anticipation for opening day.

We had a couple of archery elk weekends planned before the deer season started. Over Labor Day weekend, we were up on the mountain, chasing bugles with some close friends and family. On the night of September 6th, my dad took the four-wheeler down the road, looking for grouse. Less than a mile from camp, he rolled the quad and tragically passed away before the paramedics and Life Flight could arrive. Just like that, my best friend was gone. The hunt we had spent so much time dreaming about together was now just a couple of weeks away. All the wind had been taken from my sails.

How could I return to the places that we had just spent so much time in without him?

I had no intention of going on opening day. With friends and family in town for the memorial, I had pretty much written off the first few weeks of the season. But the night before the opener, a few great friends told me they had taken the day off work and that we were going, no matter what. They picked me up early, and we hit the road. That day is still a blur, but after a couple of blown stalks, we got on a great 4x5 that I punched my tag on. By mid-afternoon, we were back in town after a very emotional pack-out.

My wife and brother both took really nice bucks that season, but we didn’t hunt nearly as hard as the tags–or my dad–deserved. Still, we made sure to spread his ashes throughout the unit so he could keep tabs on the monster bucks he always dreamed of chasing.

“I

laid down, glassed them again, and saw one with a hook cheater and good mass. He was a shooter. After ranging and dialing the scope, I got him in the crosshairs.”

I put the three of us in for the same tag, not expecting much with just a 3% chance. But when the results came out, there it was: “SELECTED” in green letters. I had to triple-check the hunt number to make sure it was real. Somehow, we had drawn this once-in-a-lifetime tag again.

Scouting began, and just like before, we found nice bucks everywhere. Excitement, eagerness, and a little stress built as the opening weekend approached. Before we knew it, it was time to load up the truck and head for the mountains.

We had one day to scout before opening day. After striking out at a few spots, we climbed to a high vantage point for the evening. About 10 minutes before last light, I spotted a four-point buck well beyond “shooter” status. He became the morning’s target.

A good friend from work met us a few hours before daylight, and we staked our claim on the glassing knob. As the sun rose, the buck was nowhere to be found. Over an hour of glassing later, we finally spotted a worthy buck bedded a couple of ridges away, and we set off.

It took some time to reach the ridge, and we worried the buck might have moved. But through a small gap in the trees, I spotted his antlers sticking out of the brush. At 230 yards, Sarah made a perfect shot–her biggest buck, down within hours on opening day!

Because of work and school, I brought Sarah and my brother back to town the next day so they could finish their week. I turned around and headed back to the unit for two more days of solo hunting. That afternoon, intermittent storms and strong winds kept the deer bedded. I didn’t lay eyes on a single buck.

RAISED LOAD LIFTERS

SOFT ADJUSTABLE LOAD PANEL

INNOVATIVE SHOULDER HARNESS & HIP BELT

MODULAR BUCKLE PLACEMENT

EASY FORWARD PULL ADJUSTMENT

LASER-CUT MOLLE

For nearly four decades, Eberlestock has pushed the boundaries of high-performance gear—born in an Idaho garage where Glen Eberle, an Olympian and veteran, set out to build equipment that could go further and carry more. What began with a rifle scabbard evolved into a revolution in how people move through the world. That same relentless drive led to the Mainframe and the launch of our EMOD™ system—a modular, chassis-based platform that gives users complete control over how they use their gear. We’ve refined our systems alongside operators and adventure seekers who demand performance in the harshest conditions.

MODFRAME™ is the next evolution. Built from the DNA of the Mainframe but forged through years of real-world experience, it’s a lighter, stronger, and more adaptable foundation engineered for any environment. Whether you’re deep in the wilderness, navigating rugged terrain, or preparing for the unknown, the Modframe is designed to adapt and endure. This isn’t just another pack—it’s the result of decades of innovation, miles under load, and a mindset that refuses to quit.

WE DIDN’T START HERE. BUT EVERYTHING WE’VE BUILT HAS LED TO THIS. GET OUT THERE •••

The next morning was forecasted to be clear before more afternoon storms. I chose a ridge to cover as much ground as possible at first light. As the darkness lifted, deer began appearing all around me. Every drainage held bucks. I even found one of the biggest three-points I’d ever seen, and it took all my willpower not to pull the trigger.

By noon, I’d hiked six miles and passed on over 30 bucks. With storms rolling in and lightning getting closer, I slowly made my way back down and cruised a few more spots. But just like the evening before, everything had hunkered down. I had one more day before I needed to be back in town.

A fire a few weeks earlier had closed access to some areas, but after the recent rain and containment, I hoped the roads were open. I woke up early, drove 40 minutes, and was relieved to find the barriers gone. I appeared to be the first one in.

I reached the first main ridge and hiked up about a mile to glass the first big drainage. Just as it was getting light enough to use binoculars, I scanned the finger ridges across from me and saw two deer moving through the sagebrush. I set up my spotting scope and saw enough antler to know I needed a closer look.

I hustled down the hill, across the ravine, and up onto a knoll 300 yards across from the bucks. I laid down, glassed them again, and saw one with a hook cheater and good mass. He was a shooter. After ranging and dialing the scope, I got him in the crosshairs. Just then, he lifted his head and revealed a matching hook cheater on the other side. The gun went off–solid hit. He moved just 10 feet before I gave him a follow-up shot and watched him drop.

A wave of emotion hit me.

I left my rifle and spotting scope and walked back to the truck to grab my pack. I called a buddy from the office, and he started heading up to meet me, take photos, and help with the pack-out.

Still unsure what I had just shot, I made my way to the deer... and was floored. He was one of the coolest character bucks I’d ever seen. I admired him for a while and propped him up for pictures. As I waited for my buddy, I climbed a hill that overlooked the valley. I sat alone and watched the sun come up over the country my dad and I had explored together just four years earlier. I know he was there, taking it all in with me.

It was bittersweet. After months of scouting and preparation, the hunt was over in just three days. But this will always be one of the most memorable seasons of my life–not because of the buck I shot, but because I got to spend quality time with the people I love and watch both Sarah and Trey tag

CRITICAL GEAR LIST:

Rifle: Tikka T3 300 WSM

Scope: Vortex Viper 6-24x50 HST

Ammo: Winchester

Deer Season XP 150-grain

Binoculars: Sig Sauer ZULU6 16x42

Stabilized Binoculars

Rangefinder: Vortex Razor HD 4000

Clothing: Eberlestock Lochsa Merino Hoody, Eberlestock Camas Pants

Boots: Crispi Mid-Attiva

Pack: Eberlestock Mainframe with Batwings and Lid

Knife: MKC SpeedGoat

Nutrition: Wilderness Athlete

Hydrate & Recover – Peach

BY KEVIN GUILLEN

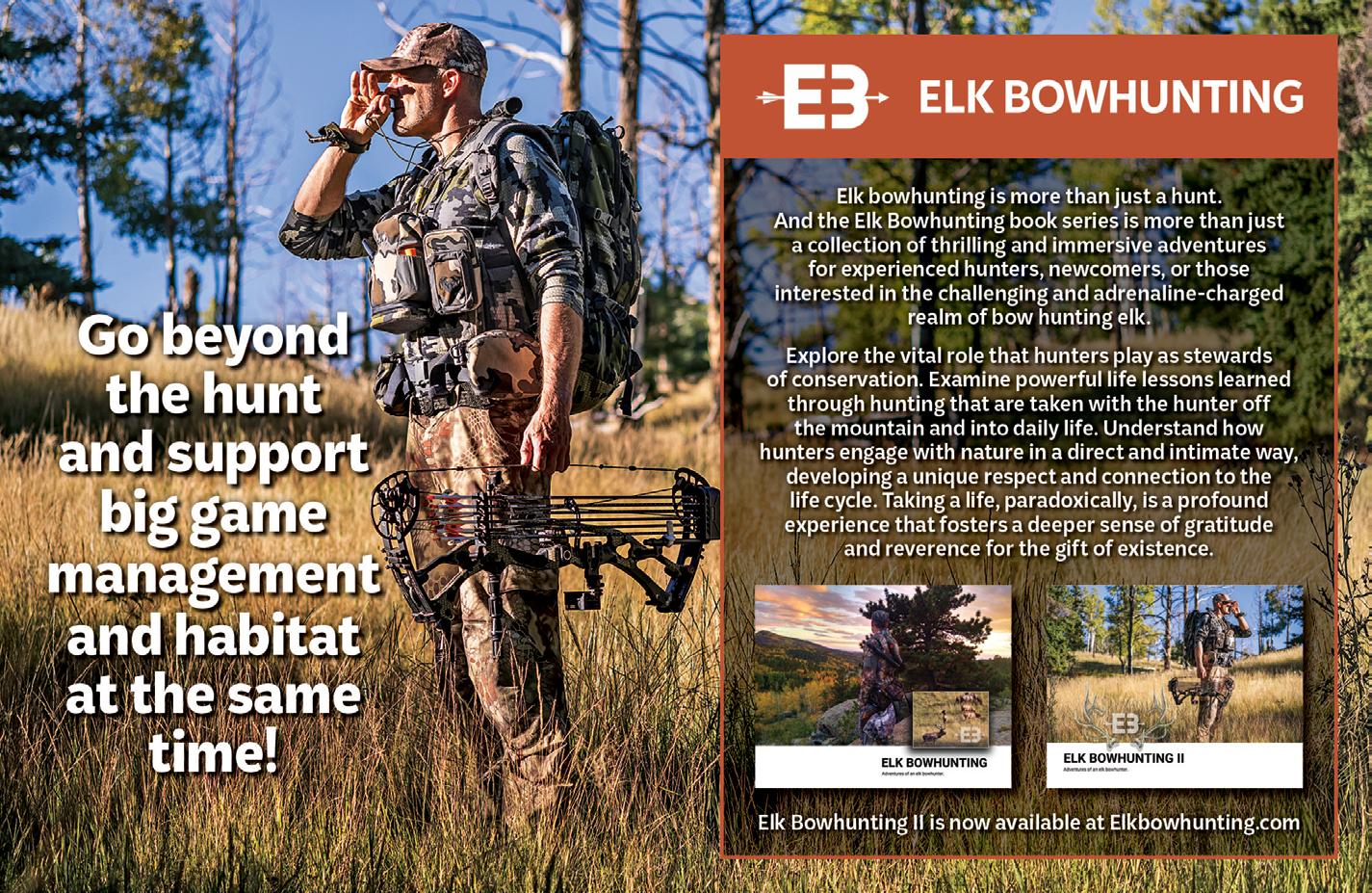

When it comes to image-stabilized optics, SIG Sauer has set the bar high with their new OSCAR6 HDX Pro. Having spent time in the field, at the range, and running around town with this high-tech unit, I can truly say it redefines what I thought was possible with a spotting scope.

The first thing you’ll notice with the OSCAR6 HDX Pro is its robust build. It’s not lightweight by any means, but for its intended purpose–whether window-mounted, hand-held from a vehicle, or used for long-range shooting–the weight feels justified. It’s like holding a precision instrument built to take a punch, not a toy. The integrated ARCA-Swiss base is a wellthought-out addition, allowing seamless attachment to tripod heads like the Outdoorsmans Gen 2 Pan Head or a window mount. The electronics and batteries add some heft, but I wouldn’t call it extremely heavy. SIG’s OmniScan optical image stabilization software is the OSCAR6’s party piece. This scope can truly be used handheld with almost the same level of stability as if it were on a tripod. Fortunately, unlike the ZULU6 binoculars, with which I often found myself battling a touch of motion nausea, the OSCAR6 delivers a buttery-smooth image without the disorienting

shake. This is likely because it’s a single-eye system. It’s not an overwhelming effect, and it almost feels like cheating–like the scope knows what you want to see and locks it in place.

The optical system of the OSCAR6 impresses with enhanced light transmission and glare reduction. Even with a relatively small magnification range of 16-32x and a 60mm objective, the image is sharp and clear. As with the ZULU6, the stability certainly increases the perceived optical performance. On a recent bear hunt, I was particularly impressed with its low-light performance–details remained sharp even as the sun hid behind thick and overcast rain clouds most of the trip.

The OSCAR6 comes equipped with a hand strap that, while a good idea in theory, leaves something to be desired in execution. It reminds me of the Peak Design Clutch strap I use with my camera but falls short in terms of comfort and convenience. Still, it adds a layer of confidence when handholding this otherwise hefty unit. I appreciate the thoughtfulness, even if it’s not quite there yet.

The detachable eyepiece is another forward-thinking design choice. This modularity hints at future compatibility with varying eyepiece configurations, adding an element of future-proofing that’s rare in the optics market. SIG is building for what’s next, not just what’s now.

Waterproof and fogproof with an IPX-7 rating, the OSCAR6 is built for harsh environments. It runs on two AA batteries, delivering an impressive 50 hours of continuous runtime. SIG recommends alkaline over lithium for optimal performance. Reliability with electro-optics is always a concern, but so far, I have had no issues. If the alternative is a “regular” non-imagestabilized scope, why not have the option to use it handheld? If the stabilization or batteries were to fail, you would be left with a good spotting scope that just needed to be used on a tripod.

Overall, the OSCAR6 is a remarkable addition to SIG Sauer’s lineup. It is a very solid spotting scope with one of the most interesting and useful new functions we’ve ever come across. It works well on a tripod, but when you need it in a hurry, it works nearly as well without one. The idea of stabilized

optics is becoming more and more appealing to hunters, and the OSCAR6 is likely the first of many spotting scopes to utilize this technology. At a $2,000 street price, it’s not cheap, but you’re paying for reliability and innovation in a piece of equipment that is built for war. It’s competitively priced with other spotting scopes in the category, disregarding the stabilization factor. Add that in, and it starts to seem like a bargain.

For those ready to embrace the latest technology on the market and rethink what a spotting scope actually is, the OSCAR6 HDX Pro is well worth the investment. This isn’t just a tool–it’s an experience. WH

TECHNICAL SPECS:

Magnification: 16-32X Objective Lens Diameter: 60mm

Battery Type: Two AA Alkaline Batteries

Battery Runtime: Up to 50 Hours Weight: 55.2 oz

Dimensions: 11.5" x 3.70" x 4.32" Cost: $1,999

Learn More: Outdoorsmans.com 1-800-291-8065

Outdoorsmans Gen 2 Aluminum Tripod

Outdoorsmans Fluid Head

Outdoorsmans Tripod Holster

Outdoorsmans Self-Timing Muzzle Brake

PROOF Research Carbon Barrel - 6.5 PRC

Leupold Mark 5HD 5-25x56

RCM Short Action

Unknown Munitions Premier Scope Rings

Rise Reliant Pro Trigger

MDT HNT26 Chassis

Gunwerks Elevate Bipod

Salmon River Solutions Fore End Weights

A

BY CONLAN McCONNELL

“I stopped him quickly with a loud cow call with my mouth reed, guessed that he had walked four yards further, held at the top of his shoulder, and executed what felt like a perfect shot. One second, the pin was where I held it, and the next, the bow surprised me by going off.”

Apparently, after 25 years of bowhunting elk, I was due for a Hail Mary to finally work out in my favor...

Montana is my Disneyland, and the last three years have been nothing short of amazing. I’ve been bow hunting elk in Montana since I first backpacked into my favorite range with my pops at 19 years old. Since then, my hunting partner and I have taken countless bulls in the Treasure State and plan to keep going back every year we are able.

For the last decade, we’ve loved going late in the bow season. It means tons of bugling and rutting activity, broken-up bulls, and very little calling unless it’s a last resort. I always keep my favorite Phelps reed in my mouth and ready to stop an elk at a moment’s notice, but we’ve found that calling truly big bulls has always been a high-risk, low-reward strategy. In open country and with vocal elk, I’ll take my ability to use stealth to get into bow range undetected any day. Sure, it’s not the same rush as when Scott called in my WA Roosevelt bull this year to 15 yards, but I’ll take success and the chance of a giant over potentially eating my tag.

On day three of the hunt, I was cruising the top of the mountain, glassing and listening for herds transitioning from bedding to feeding areas. I reached a known glassing point where I could cover miles and spotted a stud bull with 8-10 cows moving about a mile below me, headed toward a huge meadow to feed. With about an hour before dark, I doubted I could get there in time, but I figured, why not? What better option did I have but to try?

I tore down the mountain, closed the mile in about 30 minutes, and positioned myself with the best possible wind. But as I crept to the edge of the meadow, I realized the herd was halfway across and 200 yards from any edge I could get to. I could hook around and close the distance, but there was no way I would get a shot based on where they were. My only hope was that they would turn back and move toward the timber’s edge they had come from.

I moved as quickly and quietly as possible, but by the time I reached a high point overlooking the meadow, the elk had simply disappeared. With just 15 minutes of light remaining, I figured I would sit and enjoy whatever nature would provide for the last minutes of light. I was not disappointed. Shortly thereafter, and 80 yards to my left, two whitetail bucks came out of the Quakies and started alternating between sparring and feeding.

As I watched them, dejected that I had lost the elk, I eventually heard a bugle rip off below me. It seemed to be coming from the meadow’s edge, out of sight below me. Somehow, the herd had circled back, and the elk were feeding in a sheltered undulation I hadn’t been able to see. I quickly crawled 80 yards to a cluster of trees overlooking the hidden pocket below, where I could finally see the elk moving back across the meadow in the opposite direction.

By the time I got into position, the elk were 150 yards out, way out of range. I was very frustrated with myself for not checking this edge earlier, where I would’ve had a 40-yard shot at the most. Now, with only about 10 minutes of light remaining, I was stuck behind a few trees with no good options. I quickly realized it was time to try a Hail Mary.

If you had asked me the odds of calling the bull back into bow range, I would’ve said 1%, and I would have bet my life savings against it working out. I figured he would bugle back, the cows would eventually get nervous when they couldn’t see an elk, and they would all walk away, never to be seen again. The story of my life when it comes to big bulls.

My goal was to call in a cow–just one would work–10-20 yards closer. Then, I might have a chance. I gave two loud regathering cow calls, a sound I’ve only heard when elk get split up and a cow tries to bring them back together or relocate the herd. This is my go-to sound for calling cows. The bull immediately screamed back but didn’t move, and neither did his cows. I waited a minute, then gave two louder calls. He turned and bugled again, but still didn’t budge.

That’s when God gave me a bit of a miracle. Just as I was about to call again, a bull a third of a mile above me started screaming and glunking; something I only heard thanks to my enhanced hearing. I could not believe it. I told myself, “You’ve just been given a gift, don’t F this up!”

I responded with the same two cow calls, and this set off the herd bull below. He took a few steps my way but stopped. Meanwhile, the bull above had closed 200 yards and was clearly getting angrier and more interested. I cut him off with two more cow calls, and that’s when the bull in the meadow started charging toward me.

I leaned to my right as the bull below moved behind a tree, and I ranged him well inside my effective range. I drew my bow, stood up, and shifted to the right for a clear shot. He had already started walking back to his cows, and my heart started to sink. I stopped him quickly with a loud cow call with my mouth reed, guessed that he had walked four yards further, held at the top of his shoulder, and executed what felt like a perfect shot. One second, the pin was where I held it, and the next, the bow surprised me by going off.

I almost couldn’t believe it. The arrow couldn’t have been placed any better; the Trypan punched through his front shoulder, took out the top of his heart, both lungs, and broke his offside shoulder. He took one step, nose-dived, and then plowed 100 yards before expiring. As I watched in a state of euphoria. All I could say was, “Did that just happen? I cannot believe that actually worked!”

When I first glassed the bull, I guessed he was 330". I knew I would be happy with him and that he was a mature bull, but when I walked up, all I could say was, “Are you kidding me!?” over and over. He was the biggest and oldest Rocky Mountain bull I have ever seen, and with 298 pounds of boned-out meat, I figured he was pushing 900 pounds on the hoof. He later ended up being aged at nine years old. The bull’s body size had skewed my

Z5i + 5-25x56

After 25 years of bowhunting, I had finally killed something that I would call a giant, and the feel ing was surreal. It took me days to come down from that high. Even now, I can’t believe that Hail Mary worked out. The bull was a gift from God. He’s also the first Rocky Mountain bull I’ve ever taken on an evening hunt (out of 200+ evening hunts); all my other Rocky bulls were taken in the morning or midday (which seems very odd in retrospect).

The 2024 season was nothing short of a dream come true. Not only did I take my biggest Rocky Mountain bull to date, but I also accomplished a milestone that many dedicated hunters aspire to achieve–the North American Deer Slam.

From the dense rainforests of Western Wash

Conlan McConnell is president and founder of Outdoor Dreams, a nonprofit organization dedicated to making the outdoors a source of therapy and unforgettable experiences for deserving children. Their mission is to grant once-in-a-lifetime hunting, fishing, and backcountry adventures to kids who have faced life-threatening illnesses or come from financially underprivileged backgrounds in need of mentoring and positive influence.

For these children, life has often been defined by hardship; hospital stays, treatments, and challenges beyond their years. But when they step into the wilderness; stalking a big game animal, casting a line, or simply taking in the fresh air, something incredible happens. They are no longer defined by their struggles; they are adventurers, hunters, and fishermen, living out dreams that once seemed impossible.

Beyond changing individual lives, Outdoor Dreams is committed to strengthening the heritage of hunting and the outdoor community. But they can’t do it alone. If you are inspired to make a difference; whether through donations, sponsorships, or volunteering, please reach out. Every hunt, every trip, and every memory they create is because of people like you who care enough to contribute.

Contact them today and become a part of something truly life-changing. Visit OutdoorDreams.us or find them on Facebook and Instagram. WH

BY KEVIN GUILLEN

You can tell a lot about a knife before it ever makes a cut. First with the ocular pat down–does the blade have the right angles, point, length, belly, for the way you like to break down game? Then the grip test–does it seat well in your hand? Is it nimble? Does it tuck clean into your kit? Most importantly, is it going to stay put once your hands are slick with blood?

The Elkhorn Skinner from Montana Knife Company, made in collaboration with Remi Warren, passed both tests before I even got it out of the box. Add the polished stainless steel Magnacut blade and an attention-grabbing G-10 handle, and this knife doesn’t just look the part–it goes to work and makes it look easy.

I didn’t have to wait long to put the Elkhorn to use–on a Coues buck, no less–my first with a bow. Unlike most fixed blades, I never had to reach for a backup to pop joints or work into tight spots. It held its edge and sat naturally in my hand from the first incision to the last pull. After breaking down several animals with it now, I’ve come to appreciate its compact, stout 3.125-inch blade. It’s short, strong, and razor sharp.

Montana Knife Company doesn’t make knives to sit in display cases (even though they look good in one). They make tools that earn their keep. And with Remi’s input, drawn from the hundreds of animals he’s broken down in the field–the Elkhorn was built with purpose. It’s not just a collector’s piece; it’s a hunter’s instrument, plain and simple. WH

BY MARC CARLTON

A Trojan condom, duct tape, and a lead top cut out of a Johnson & Johnson toothpaste tube, fashioned with a file in hand, into a queer sort of horseshoe-shaped sandwich–destined to become the modern-day mouth reed. A pivotal hunting accessory that most turkey and elk hunters would never leave home without. This is one of Wayne Carlton’s (my father’s) favorite recollections as a school-aged redneck kid from Florida in the 1950s.

He first became mesmerized by wildlife language while listening to a turkey-hunting connoisseur (an uncle) found sitting in a corner, formulating bird sounds that no normal human being should be able to replicate while running his Frankenstein-esque turkey call. The audacity of putting the unsafe lead, hardware store duck tape, and a rubber prophylactic in one’s mouth was missing.

Being a descendant of this family tree, I’m unsure if I feel proud or terrified. Like all first ideas, I see and imagine it was a thing, an idea passed through word of mouth from hunter to hunter and adapted and modified, as humanity does with all first tools useful and practical. The beginning was inauspicious for a Bowhunting Hall of Famer and elk call pioneer. A redneck kid that grew up on the railroad tracks in Campville Florida, where real estate was cheapest and trains rattled the windows and front door. By the time he was 20, he’d already lost three siblings to the harshness of life.

Raised by a well digger whose only attributes were being a hard worker but an ass of a person and an abusive father. Wayne’s saving grace was his uncles who lived in the Florida swamps, willing to take an eager kid hunting, changing and saving his future. The palmettos and sand never lacked adventure, from gigging frogs to running blue tick hound dogs that were, back then, the best method for taking down deer and coons. Tree stands had another 10 years before they showed up, so his famed lead dog Snapper usually won the day.

One summer night with a full moon, tagging along with the family legend Uncle Harvey to a tree full of coons that paid a nickel a piece for the pelt, the game calling cause & effect took a permanent seat in Wayne’s young, impressionable brain. Using his natural voice, Harvey let loose an imitation of “an angry dog having a pissed-off raccoon wrapped around his head and fighting for his life.”

Every furry bandit in the tree turned and looked down to bear witness to which one of their friends was dying as Harvey belted out this raspy scream of coon-death and dismemberment, simultaneously shining the light up into their eyes. I’m told that the Cypress tree looked like someone had hung Christmas lights as those beady little eyes lit up. Firing then commenced with little Wayne’s single-shot .22. The lessons and benefits of calling critters were well learned with a decent payday of coon pelts that was better than shucking watermelons into trucks, the usual summer job. A few years later, that kid turned 17, dropped out of school, skipping his last two years, and joined the Navy to get away from home. Six years after that, he was selling services for the Sapp family at Florida Pest Control. Sales was a natural fit for him, foretelling what was to come.

Every year, the boys from Florida Pest Control made a trip out west to do what every southern boy wanted to do. That was to take an adventure after big game. He found his way out to Colorado on these company-justified hunting trips with the boys, which were cherished and preserved in time via the sharing of camp elk meat and Coors beer that you could only buy in Colorado at the time. After a few life-altering encounters chasing elk, those early events turned into the ultimate “here, hold my beer” moment of youthful bravado. Wayne permanently packed up his life and ventured west like one of the Clampetts on TV. He made his way west in 1976 with no job, no prospects, just a desire to be more with a 66 Bronco, a wife, two kids, and one ill-tempered Weimeraner.

Wayne was self-admittedly very fortunate; it’s a crazy story that writes itself so colorfully that it’s unfair, and there are so many pieces of his journey that I’ll never get it all down on paper. Still, I always find the origin story of every person is the best part.

In the early ’80s, the city of Montrose put money toward promoting the area for tourism and hunting as a resource. Wayne had become a known big personality character from Florida who started the first NWTF chapter in Gainesville, Florida, and then the western Colorado chapter. The National Wild Turkey Federation was only a few years old, founded in 1973, and was a very new thing that garnered attention. Wayne, with a creative mind, had also learned to bugle on a turkey mouth diaphragm. One fall he heard a distant elk bugle and thought it was a lost turkey doing a kee-kee run, (a high-pitched, shrill whistle), looking for other turkeys. Hearing the distant bugle and making the connection, he did the obvious thing. If one can make a kee-kee run on a turkey reed, one could probably make and replicate a high-pitched bugle on the same call. The local legend was born–a crazy guy with a southern accent who could bugle like a nut on a turkey call. Wayne, who then owned Carlton’s Pest Control, was drafted to guide a city-sponsored hunt for outdoor writer Rich Laracco. It was the kind of hunt that lasted a lifetime, where bulls were called in and fights broke out in utter mayhem, which rarely occurs in the woods, as a cyclone of elk chaos ensued. The kind of things never to be forgotten in a lifetime. Rich pulled Wayne aside and gave some life-altering advice: “Wayne, I don’t know if you like killing bugs, but you have a unique thing here that will change everything. If you grab it and make something of it, you may have a new career.” Just like that, Wayne Carlton Calls, the Red, the Double Blue, and Triple Brown mouth reeds were born, along with the first bugle tube and a how-to audio tape, Elk Calling with Wayne Carlton. In 1981, our culture was born.

Back then there was no media, and education on a subject like this was impossible to find. Outdoor magazines were the center of the world to learn from, and at one point Wayne had a featured article in most, if not all of them. Wayne bashfully admits to having to go home after his first elk hunt in the early ’70s to read in an encyclopedia that those big mud wallows in the mountains were, point of fact, made by elk and not some elusive mountain pig Wayne had yet to see because, mistakenly, that was all a Florida boy knew. Pick-up trucks were still rocking eight-track tapes, cassettes were cutting edge, and VCR was still five years out.

Having the outdoor magazines grab hold of you was like going on the Joe Rogan Experience and becoming an overnight sensation. It was a priceless lightning-strike opportunity. Only a staggering 1% of all startup companies make it, so to be in that 1% that rides all the way to the Hall of Fame is a rare story indeed.

“Yes,

we are an odd bunch, proudly fanatical and obsessed. What went unsaid was the unconscious connection between man and nature, in which we became closer as we spoke in some small measure to each other during the real million-year-old Hunger Games in what became a version of Marco Polo to the death.”

Fast-forward a little to 1983. In the first days of Wayne Carlton and Larry D Jones pioneering elk calls, a new passion was sown while chasing buckskin-colored bulls through black timber and aspen benches. The pair were calling elk on an old Double Straight turkey reed that was destined to become the Wayne Carlton Double-Blue. The first mouth reed/diaphragm ever used for bugling, seemingly overnight, started carving out new landscapes in modern-day hunting–creating jaw-dropping reactions, weaving their way into our stories and experiences, and emotionally branding us with each encounter as a new language developed.

We became more than hunters. We became today’s elk callers–connected through new little blue widgets of latex and duck tape, squealing and chuckling through (to my mother’s dismay) vacuum cleaner hose, butchered down and rattled-canned with a child’s pride–all while trying to master the most unnatural of things.

Most people would think it was next-level weird and crazy and, truthfully, it was... How do you even describe it? “Do ya wanna hear me sound like a rutting bull elk in mating season? Here’s my Elk diaphragm made out of duck tape and a condom!” It sounds like the worst pickup line ever... All woke jokes aside, if some woman bites on that one in a bar, you better do a full Crocodile Dundee crotch check, to be safe!

Yes, we are an odd bunch, proudly fanatical and obsessed. What went unsaid was the unconscious connection between man and nature, in which we became closer as we spoke in some small measure to each other during the real million-year-old Hunger Games in what became a version of Marco Polo to the death.

Like a favorite gun or bow and time spent spinning arrows, the calls we used started to tether into our stories, making them more than just things. They became characters and lore. Calls and calling wild game had become the instrument and hymn of a new religion. The Carlton telling is one chapter of many, reaching all the way back to probably Compton. Each story is inspiring but always seeds the next branch of the tree–Pope and Young and Ishi.

Cultural Phenomenon

From there, it was Fred Bear, Tom Jennings, and Howard Hill. Wayne was in that next generation of road pavers of a young and growing industry in the ’80s along with the likes of the Ben Lees and Knight and Hales. Treebark, Realtree, Mossy Oak, Eastman’s, Muzzy, Hoyt, and Mathews’. The boys at NWTF, Brown, Rob Keck, and Kennemer. All RMEF members are called family today. It’s a lineage and culture built on passion and sacrifice by the ones who laid out that road we all walk today. There was and is, and should be, a family tradition, an uncle, a close friend, a strong mother–mentors who inspire and guide all of us to a fraternity of traditions. Wayne’s life was made better by Uncle Harvey and so many more who taught and guided his path–so many that I’ll never find enough room in a magazine article to tell you about it and thank them. He, in turn, passed it along in buckets to the rest of the hunting world.

Wayne’s story isn’t about the rise to the Hall of Fame as the elk guru. It’s rooted in conservation and community as he started the first NWTF chap ters when his name meant nothing. It was just a sincere effort from a Florida redneck with the honest intention to make things better. He was undoubt edly gifted some opportunity, but I credit him for seeing the moment, taking it in a death grip, and never letting go of that fateful offer of chance. God puts things in front of us all the time. It’s our job to grab hold and do some thing with them. Wayne grabbed it.

Within a few years, he was asked to appear as the RMEF Elk Country Journal TV host, bringing what he did best to thousands of new hunters and filling his fall seasons for seven years. Every spring for 17 years, Wayne hosted a turkey hunting school at Vermejo, teaching and educating, all the while developing ideas, building a business, hunting, giving seminars, doing

trade shows, being the key part in magazine articles, etc. Inspiring, mentoring, and passing on the simple traditions gifted by an uncle a lifetime ago. He both taught and entertained–the original influencer.

In 1998, Wayne Carlton Calls was sold to Dave and Carmen Forbes, owners of Hunters Specialties. This allowed him some great years of bringing ideas and making and sharing hunting stories, finishing out a storied career. In 2017, Native by Carlton was established and co-founded by Wayne and Marc in a grassroots rebuild to get back to the hunting core and as a final place for Wayne to hang his hat.

Parkinson’s and Dementia finally caught Wayne in the end after 20 years–no doubt from all the pesticides he used back in the pest control days. Although, in every season, there was, in all honesty, a near-death experience from all his countless crazy adventures. From jumping off aircraft carriers in the Mediterranean Sea during flight drills on a $90 bet in the Navy to calling bears and gators to six feet, harassing rattlesnakes, swimming rivers on mules during spring runoff, and countless other dumb ideas that would challenge any testosterone-filled teenager to do crazier things, we never thought he’d make it this far. And, although he would have preferred a glory-filled ending like Brad Pitt in Legends of the Fall, a bear death with Bowie knife in hand, we’ll have to settle for all the stories of him almost dying instead.

In the end, what makes legends and mentors great are the tangible parts, relatable to things in our own life experience. He was always reachable with a handshake, and he probably gave out more free calls to kids than anyone. Wayne, at the beginning and the end, was just one of the guys who was never far removed from the railroad tracks outside his front door. One foot always in the sand on a single-lane road in Campville, with his single shot .22 and a box of shells in hand, straining an ear for the dogs baying in the dog box, with Harvey just coming around the corner to take an eager kid

“ Best Ruck Frame and Even Better Company!

The Gila Monster is one of the great semi-mythical creatures of the Southwest. Extremely rare to encounter, it holds the title of the largest native lizard species north of the Mexican border–with accounts of specimens spanning 24 inches in length and weighing 35 lb. With skin that both appears and feels to the touch like a brand-new indoor basketball, its appearance is nearly unique in the animal kingdom.

Similar to its desert floor cohabitant, the rattlesnake, a glimpse of this wildly unusual shape invokes a primal, I-had-better-not-get-near-that-sucker kind of fear. Although extremely slow and relatively docile, the Gila monster’s bite is worthy of its cryptid moniker. Its bite contains gut-twisting, skin-melting venom that, while rarely fatal, generally results in a horrific day (or several) for its recipient.

On a positive note, it turns out this venom carries a hormone that is much better at balancing insulin production than the one that naturally occurs in humans. This discovery led to the creation of a new type of extremely effective diabetes drug. So, if you’re a diabetic on the receiving end of a semaglutide injection or you know someone who has lost an inexplicable amount of weight recently, remember to thank the Gila monsters who donated their spit to help create Ozempic.

While shrouded in Native mythology and tales of curses, possession, and man-killing tendencies, the Gila monster is simply a creature that should be observed and left alone. Whether you believe that seeing one brings good luck or marks you for death, as some of our predecessors proposed, one thing is for sure: It’s a wonderful example of the creativity and mystique of nature.

BY KEVIN GUILLEN

There are many beautiful things in the anatomy of a rifle. Its tapered and elegant barrel. The crisp and precise break of its trigger. The fluid repeatability and strength of its action. Its balance, its weight, its sound. And its stock–the component that is both skin and skeleton of a rifle, bringing everything together, turning machined aluminum and steel into a functional instrument of art. Viewing a rifle in this way stems from a handcrafted approach to manufacturing, one that began with Gale McMillan building his first stock in 1970.

During my visit to the McMillan facility in North Phoenix, I could see the same attention to detail and handcrafted perfectionism alive and well today in their commitment to American-made precision rifle stocks. In a world of shortcuts, McMillan still does it the hard way, and that’s why their stocks are trusted from PRS podiums and NRL Hunter matches to combat zones.

The story of McMillan begins the way many great things do–at a workbench, in pursuit of something better. In the early 1970s, Gale McMillan, a benchrest competitor with a relentless eye for precision, began layering fiberglass to build a rifle stock that could meet the exacting demands of his sport. By 1973, he had crafted his first competition stock. A year later, McMillan Stocks was born.

What followed was a ripple effect through the precision shooting world, first with the HTG, the military’s first purpose-built sniper stock, and soon after with the M40-A1 rifle, issued to Marine snipers and built from the same bones. By the 1990s, McMillan’s fingerprints were on rifles carried by Navy SEALs, including Chris Kyle, whose .338 Lapua deployment rifle was built by McMillan Firearms, a sister company. These weren’t just stocks–they were instruments of trust in life-or-death conditions.