We are excited to bring you edition nine after a semester-long hiatus. During the pause, we learned new skills on InDesign, developed potential article ideas, and grew individually and as a team. With the graduation of former contributor Eliza Berhke, we welcomed two new members: Sydney Cagnetta and Luka Kelava.

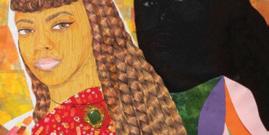

This year, we welcome another year-long exhibition, Jamea Richmond-Edwards: Another World and Yet the Same. Through vivid color palettes, sequined collages, and serpentine motifs, the Wellin Museum has been transformed into an immersive story of identity and imagination. Drawing upon Bishop Joseph Hall’s Mundus Alter et Idem, the exhibition follows Richmond-Edwards and her family on a fantastical expedition to Antarctica, a journey that blurs the line between myth and reality.

Alongside Jamea Richmond-Edwards’ solo show, the Wellin Works space has been reimagined as a gallery dedicated to the artist’s creative community. EXODUS features work by Stan Squirewell, Larry W. Cook, Wesley Clark, Akili Ron Anderson, Shaunté Gates, Hubert Massey, and Felandus Thames, highlighting a powerful network of artistic exchange and collaboration.

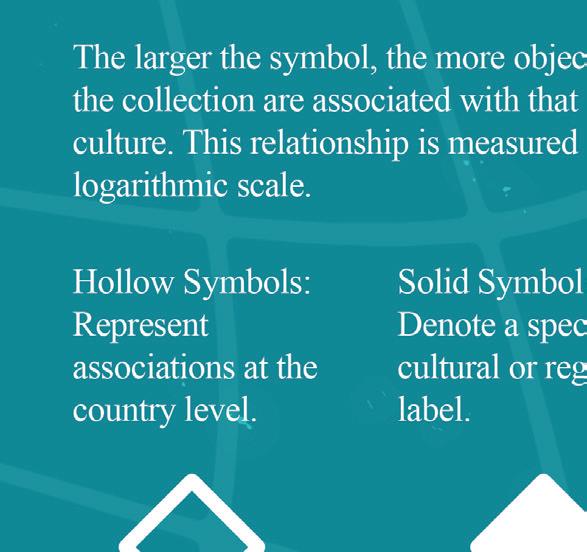

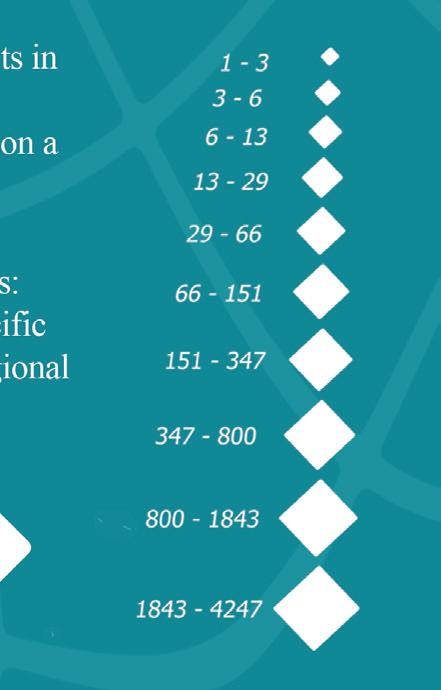

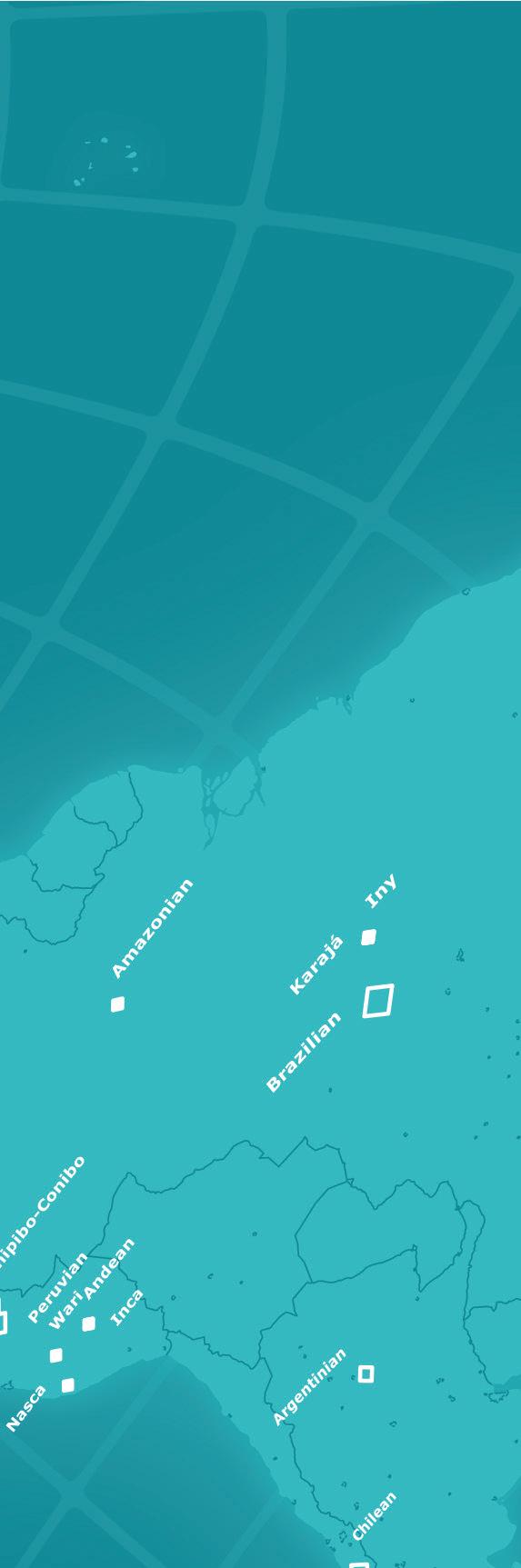

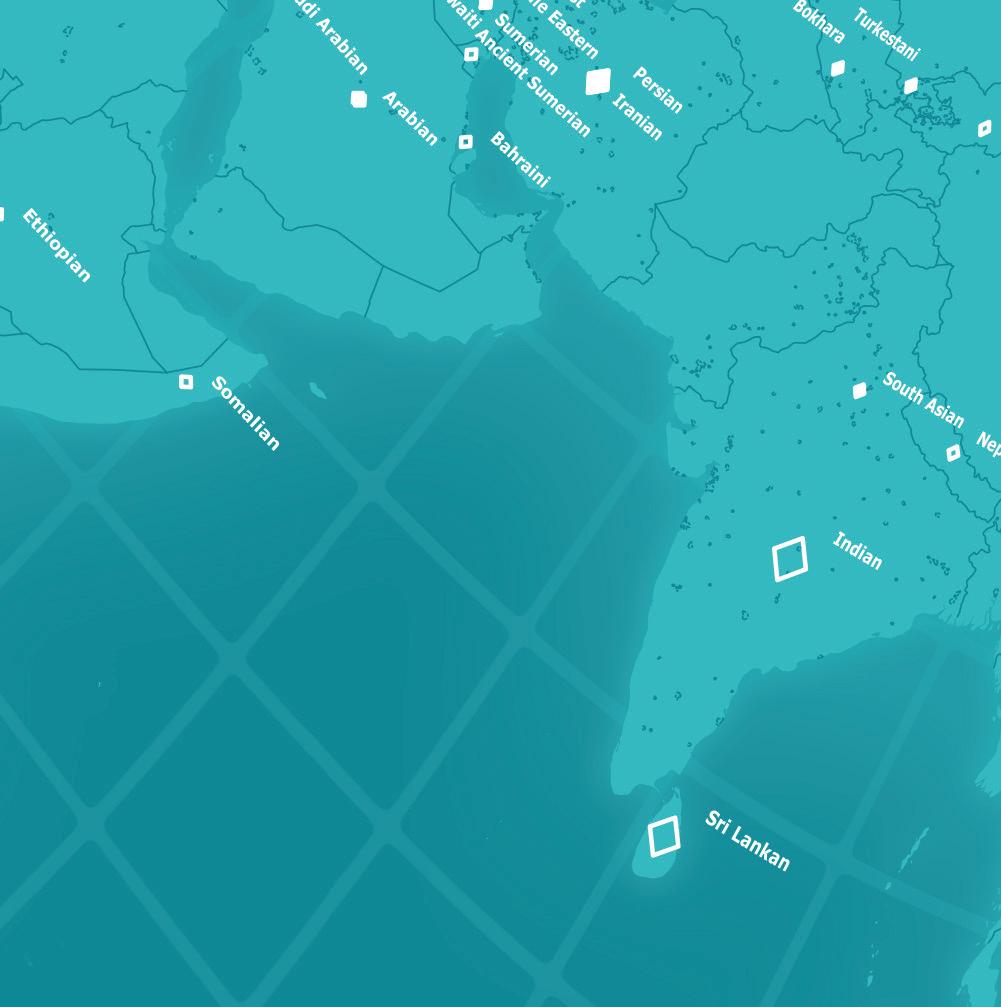

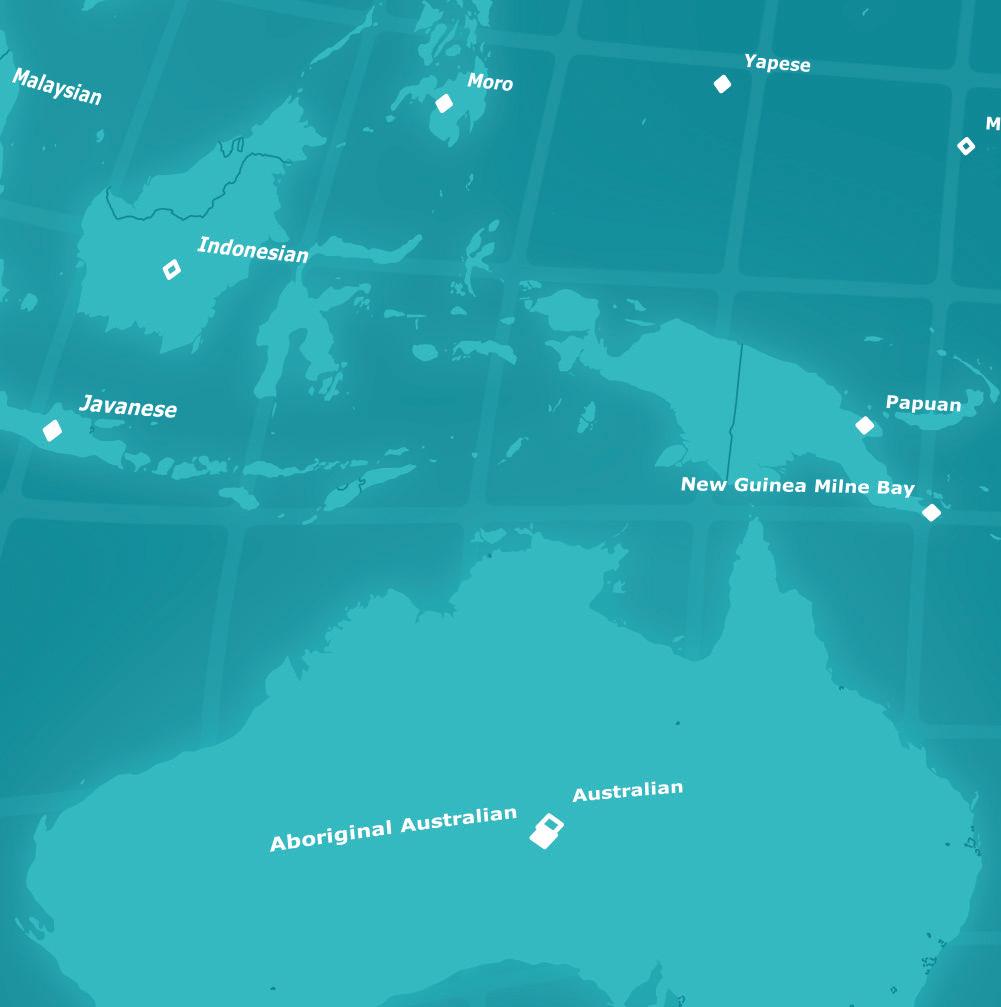

Just as Jamea Richmond-Edwards’ work could not have been realized without the mentors and peers featured in EXODUS, Collection magazine would not have been possible without the guidance and support of many. We extend our gratitude to Curator Liz Shannon and Registrar Laura Laubenthal for their expertise on our study collection article; to Emily Girard for graciously accepting our interview request; to Renée Cox for kindly sharing an image of her artwork with us; to Laura, once again, for fulfilling all of our image requests and information on the origins of the Wellin’s collection used to create the Map of the Collection; and to Marjorie, our faithful editor. And, of course, our heartfelt thanks to the Wellin Museum for nurturing and inspiring our creative spirits.

We hope this magazine takes you on a journey of your own—finding joy alongside Lily’s interactives, exploring the world of mapmaking with Luka, uncovering the history of photography with Sydney Cagnetta, questioning ambiguous titles with Liv, navigating Afrofuturism with Sydney Piccoli, and examining the relationship between advertising and art with Kenna.

Now, it’s time to turn the page...

Happy reading!

Sydney P. ’26

Major: Art History

From: Scarsdale, NY

Fun Fact: I’m an avid clog wearer!

Lily W. ’26

Major: Environmental Studies

From: Saint Petersburg, FL

Fun Fact: I took two semesters of Chinese at Hamilton for fun!

Kenna S. ’26

Major: Art History

From: Austin, TX

Fun Fact: I love inter-library loan!

Sydney C. ’28

Major: Art & Physics

From: Wake eld, RI

Fun Fact: I make jewelry out of sea glass!

Liv P. ’27

Major: Art History & History

From: Oneida, NY

Fun Fact: I’m taking a U.S. history class in Edinburgh!

Luka K. ’27

Major: Art

From: Dania Beach, FL

Fun Fact: I like the smell of printer paper!

By: Lily Watts & Sydney Cagnetta

Earlier this fall, the Collection team had the pleasure of sitting down with exhibiting artist Jamea Richmond-Edwards to learn more about her personal life and journey as an artist. Our goal was to ask questions we’d been formulating since first meeting her during docent training at the beginning of the semester. Richmond-Edwards has spent ample time on campus, between the opening reception, lecturing in different classes across departments, participating in artist talks, and much more. As we learned more about her upbringing and career over the semester, our list of questions grew. We were fortunate to have interviewed Richmond-Edwards and spent time with such an inspiring artist.

We first wanted to learn why, of all museums in the world, Richmond-Edwards chose the Wellin specifically to collaborate with and show her work. Her art has been exhibited at major institutions nationwide, including the Brooklyn Museum, California African American Museum, Frist Art Museum, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, among many others.

Richmond-Edwards shared with us that she worked as an educator for 13 years, primarily in secondary and some higher education, and loves teaching more than anything. Because the Wellin is connected to a college institution and is a teaching museum, she has greatly appreciated interacting with students like those at Hamilton. RichmondEdwards shared, “I really miss education, so me being here and speaking to the students is really the highlight for me [...] I love just meeting quite literally the future. You all are the future so [...] that’s why I was really excited about it [...] it’s helping push me forward as an artist.”

As a teaching museum, the Wellin facilitates student engagement with its interdisciplinary exhibitions through tours, interactive programs and campus events, artmaking workshops, and work opportunities to be docents and student assistants. It is valuable to have a space for students

Photographer: Janelle Rodriguez

to gather and appreciate art through a diverse teaching collection and engaging programming. With this, and considering Richmond-Edwards’s background as a teacher, we were curious if she ever reminisces on being in the classroom everyday. She shared, “I actually would rather be in the classroom most of the time and I’m okay with saying that. I really do.” Richmond-Edwards says she doesn’t appreciate those who speak negatively about today’s younger generations, as she feels blessed to be around such bright minds and students. “When I’m speaking to [...] students, it helps inform me and [...] give me refreshed ideas [...]. So, yeah, I miss it a great deal.” Her ties to education are evident.

One of Richmond-Edwards’s bodies of work is currently displayed at the Wellin and is entitled Another World and Yet the Same, depicting the journey of a set of characters, inspired by her family members, on their voyage to Antarctica and settling a new society. The ending of the series, with the arrival of the mothership to Antarctica, leaves the body of work open ended, sparking our curiosity in the direction Richmond-Edwards will take this series next. She shared some of the practices she uses in creating her art, stating that she doesn’t like any limitations, even those of humanity, leading her to create exercises to stretch these limits. “One of the exercises I like to do is how far can I think, like what’s the most far out imaginative thing that I can think of.” She also shared some of the direct inspiration she is planning to use for the continuation of the journey of Iceberg, the main character of her series, inspired by her son Yikahlo. “When you look at older maps, [...] a lot of those maps suggest that there’s realms outside, beyond the [ice] wall.” Richmond-Edwards has begun to create those worlds for her body of work, while also incorporating ideas from different media such as films and television shows that represent those outer realms.

The Wellin is also host to several other pieces

by Richmond-Edwards, including a set of threedimensional figurines and the beginnings of a map, displayed in the Object Study Gallery. We were curious to understand how those objects played into the current exhibition or RichmondEdwards’ future plans for Another World and Yet the Same. She divulged that when developing ideas, she thinks about how they can manifest beyond the two-dimensional. This led to the creation of the figurines and films displayed within the exhibition, which include costumes that she designed, and a sound element commissioned by her friend Sheefy McFly. “I’m thinking from a very immersive lens, [...], what does it look like when you wear it, what does it taste like? So I’m always thinking [...] how expansive can the idea get?”

Considering how all the subjects of RichmondEdwards’ portraits are based on her family and friends, we were also curious about some of their reactions to her work. We asked her if anyone has ever shared comments that resonated with her, whether positive or negative. RichmondEdwards said that none of her portrait subjects have ever shared any criticisms of her work. “To be honest when I’m creating a work, I’m like, ‘I

don’t care about y’all’s feedback!’ [...] That’s why I work typically with family because it’s like, I’m y’all’s child, and sister, and mom! [...] You know? You can’t attack me! [Laughing] And interestingly, my sons, they’ve been okay with it [...] even with my son Yikahlo, [...] who I used his likeness for Iceberg, [...] he was okay with being filmed and playing this role and this character. So they’ve been very supportive and I’ve been an artist [...] literally my whole life. So they’re kind of like, used to my shenanigans.” Richmond-Edwards’s work is deeply personal, and she makes artworks that depict her lived experiences. Richmond-Edwards shared that her family is supportive of all her works because, “I made it for us! Y’all gonna be okay, this is all for the better.”

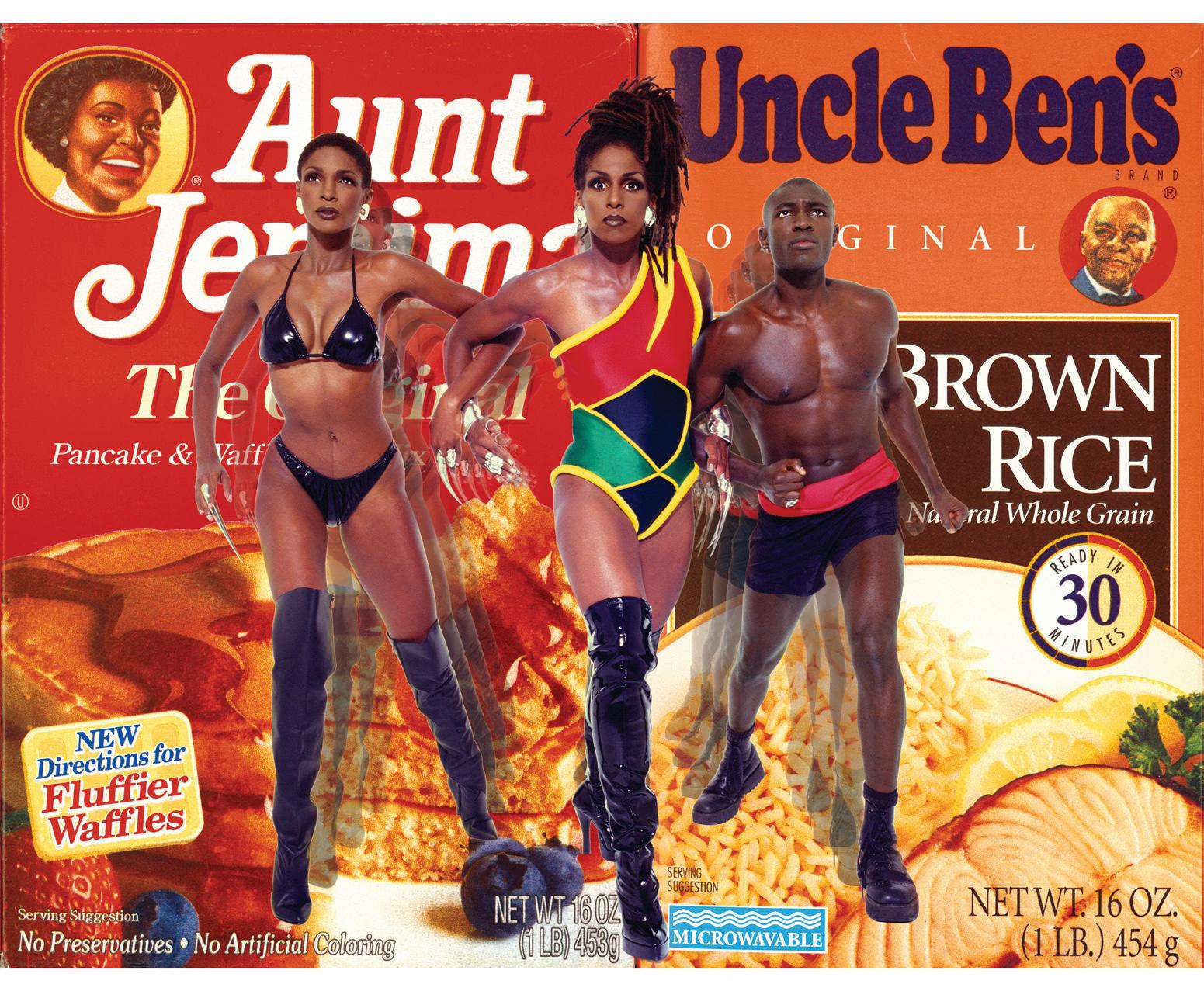

We inquired about the influence any artists had on Richmond-Edwards in order to gain a broader understanding of her background and where she draws inspiration from. In 1998, during a gifted and talented class in high school, RichmondEdwards visited an exhibition featuring a work by American photographer Renée Cox, titled The Liberation of Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben. “That was my first introduction to [...] contemporary art

particularly from a black woman and the work [...] has a very radical tone to it.” Prior to this, Richmond-Edwards’s artistic upbringing focused on classical artworks, studying European artists. Cox’s artwork was also particularly engaging for Richmond-Edwards, as the artist featured herself as one of the main figures, a theme now seen in Richmond-Edwards’s work. Outside of contemporary artists, Richmond-Edwards pointed to Michelangelo as another big inspiration to her journey. She was 19 years old when she saw her first Michelangelo piece, Pietà, depicting Mary holding Jesus after he was taken off of the cross, which evoked a particularly emotional reaction from her. Richmond-Edwards also mentioned that, as her mentor Hubert Massey stated to her, Michelangelo was working in a variety of mediums from sculpture to fresco, and wasn’t limited to any single material. “That really stood out to me, [...] I’m gifted at many things, so I don’t have to just [...] paint or draw, I can do film, music, dance, etc.”

In addition to our formal interview, we also wanted to ask Richmond-Edwards a series of fun, rapid fire questions to get to know her better on a personal level.

Outside of the Wellin, what is your favorite museum that you’ve been to?

“I’m gonna have to say the Detroit Institute of Art (DIA) because they have the Diego Rivera murals and it’s [...], a masterpiece. And every time I go to that museum, [...] and I look at that mural, [...] it’s a fresco, I’m just like astonished by it [..].”

The DIA collection is regarded as among the top six museums in the United States with an encyclopedic collection which spans the globe from ancient Egyptian and European works to contemporary art. The DIA is home to over 65,000 works, with one of the most notable acquisitions being Mexican artist Diego Rivera’s Detroit Industry murals, which he considered to be his

most successful work. The murals span the upper and lower levels to surround the central grand marble court of the museum.

What would you say you’re most proud of in life?

“I would say being a mother of three sons. [...] One of the highest honors is being a parent. And to [...] witness your children doing what they love and pursuing their dreams, [...] to me that’s the highest honor.”

When in your life did you decide to incorporate your children into your artmaking? Was it something you knew you wanted to do immediately, or something that developed over time?

“So I’ve only recently just added my sons to the work—like literally this body of work. But, for me I believe that children [...] chose their parents, and so I’m like ‘You all chose me so buckle up, y’all are on this ride with me.’ So I had my first child at 21, I was a young mother, and they have been a part of my journey, you know what I mean. [...] I’ve always done art and they learned [...] even when they were toddlers, don’t step on the painting that’s drying on the floor, walk around it, and they just kind of grew up immersed in that environment.”

What are your favorite things to do when you’re home in Detroit, and where do you like to eat?

“My favorite thing to do is research. I read [...] a lot of scholarly papers [...] I just love research. [...] And right now [...] it’s a restaurant called HIROKI-SAN which is a Japanese fusion restaurant, and I just love it. It’s so yummy.”

Where do you do your research when you’re home?

“[...] My library is [...] the architecture, the cities, the buildings, and [...] my friends’ studios, and because we have the archives online, I haven’t

really had to go into the archives since I’ve been in Detroit. So I’ve been in the library but I like researching the architecture itself.”

What is your favorite concert that you have been to?

“I recently went to a Theo Croker concert, who is a jazz musician, and he just played at [...] Ann Arbor at the University of Michigan at the film festival and my son was his bassist. It brought me to tears. They sound so good they were just playing some amazing jazz. So I’m really into jazz, I mean I love all music, [...] I went to an amazing Kamasi Washington [concert]. [...] I’ve been in a jazz way the past seven to eight years, and now I’m leaning back into hip hop [...].”

Are there any contemporary artists that we should

look out for that you’re really interested in or inspired by?

“I would say Mario Moore. He’s a contemporary Detroit artist. You all just acquired one of his pieces here in your collection. He’s an exceptional artist and a good friend of mine but I’m really inspired by his work.”

Moore, a Detroit native, has exhibited work across many museums, including the DIA. The Wellin acquired his oil on linen painting entitled Garland of Resilience earlier this year. When asked what about his work inspired Richmond-Edwards, she told us, “just his skills, he’s an oil painter, we paint completely differently. He started creating [...] these winter scenes which inspired in part this body of work. [...] The brother can just paint really well. He’s just really good.”

Are there any other artists that you’re interested in currently?

“So I’m really interested in architecture and I’ve been interested in car design [...]. I’m in the art world, I’m not of the art world, which means that I [...] don’t really mess with the art world. I’m really moreso into design and [...] my favorite artists are [...] my peers. I don’t look up art online, I typically experience it when I go to museums. [...] There’s a Detroit artist named Tiff Massey who does metal work. She had a great exhibition at the Detroit Institute of art, [...] monumental, just brilliant.”

Another Detroit native and exhibiting artist at the DIA, Massey’s jewelry, sculptures, and performances examine race, class, and Black culture. Trained as a metalsmith, she creates largescale metal sculptures that celebrate Detroit’s evolving neighborhoods and the history of West African and Black American culture and style.

Do you have any other words of advice, pieces of information, or just thoughts in general that you haven’t yet shared with us?

“What I would say [...] for your generation, just to be courageous. That’s all I can say, you know? Because I feel that we are in a time where we’re being heavily edited, censored, and [...] we gotta fight the good fight in terms of being true and it all revolves around gumption. It’s so much. That’s all I can say at the moment because I’m working through it myself.”

When Lin Manuel Miranda came to campus, he voiced the same opinion as you, and spoke on how to navigate being an artist in the 21st century. Especially considering today’s political climate. He talked a lot about censorship and making art unapologetically, for yourself and what you stand for.

“That’s it, and you just have to be honest. [...] I feel especially as [...] women, they try to intimidate us and scare us and [...] nope. [...] The beauty about art, I don’t have to talk about anything. The artwork is speaking for me. I don’t have to make a political post, I don’t do anything. My artwork says everything that I need it to say. So I’m kind of lucky in that sense. [...] Stand ten toes down.”

Caretakers walking the greyhounds - each “lad” has 6 to 8 animals each and walk about 10 kilometers each time, Le Coudray, France - Denise Bellon

Are You Sleeping? - Harry Nilsson

Two Sisters and the Horned .

In March of 1949, the Museum of Modern Art in New York held its 28th annual exhibition of advertising and editorial art. The exhibition featured ad art hand selected by the director of MoMA, the art director for FORTUNE magazine, art historians, and other prominent art directors and leaders at the MoMA. Advertisements of Lifesaver candies set up in football formation, Navy recruitment, and an insect extermination company all graced the walls of the fine arts institution, to name a few—and hundreds more ad agencies applied. These images, obviously intended for consumer consumption, to sell something, contrast with the traditional selfperception of the fine arts as something with a

more complicated relationship to money. And yet, a major institution like the MoMA put advertisements on display as art.

This uneasy relationship between “high art,” art which supposedly transcends monetary sway, and advertising which is “art” for a quick buck is pervasive. Ideas of “selling out” and art without soul persist in the contemporary tension between artists and advertisers. However, the overlap is apparent. Some of photography’s most renowned artists, Richard Avedon for instance, was wellrespected in the advertising and the art world. The two realms, undoubtedly, overlap and take from one another. Artists like Barbara Kruger or

Julia Jaquette gather inspiration from advertising, and advertising, subsequently, takes back. As Monroe Wheeler said in the guide to MoMA’s 28th ad-art exhibition “Art and commerce have frequently been linked in our own day as in the past, and cooperation between them is a satisfying achievement but by no means an easy one.”

Art historian Jackson Lears argues that the tense relationship between advertising and art stems from their growing closeness—an overlap that artists are not sure how to handle. As the 20th century progressed, so did tastes in advertising. Companies began to search for a new look. Historically, the pervasive aesthetic in advertising was what literary critic Northrop Frye called “stupid realism.” This style, a saccharine and aspirational way to advertise any product, had grown old for many corporations who began to eye modern art as their next inspiration.

though tense, became mutually beneficial.

“Stupid realism” never went away, but it began to be overshadowed by ads that looked more and more like contemporary art. Not only did companies borrow motifs, designs, and aesthetics from modern artists, they employed them. Artists resisted corporate assimilation intellectually, but often worked for companies alongside their personal ventures. Photographers, illustrators, and painters alike found that they could make quick and relatively easy money. The relationship,

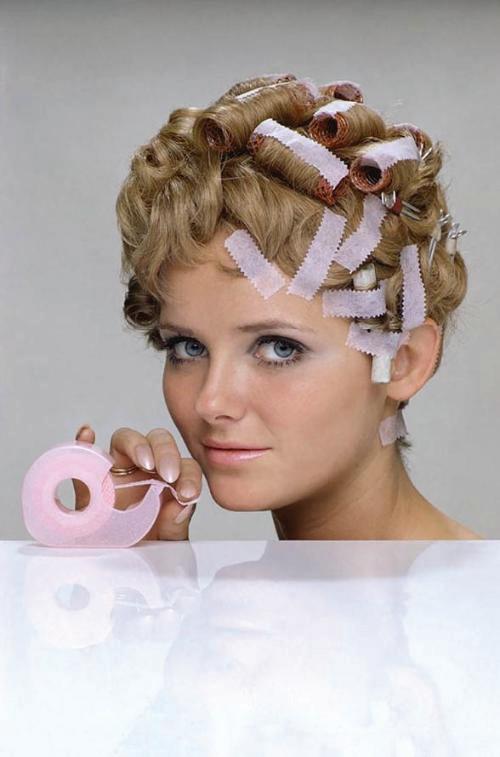

William Helburn’s Cheryl Tiegs Hair Tape, on view now in the Wellin’s Object Study Gallery, reflects this dynamic and tension. Stripped of its advertisement captioning and lettering, the photo stands on its own. The model, Cheryl Tiegs, stares out at the viewer with a slight smile. She gently pinches a piece of pink tape, as if to use it in her already well-taped hair. The background is unadorned, a simple white wall and a reflective white table which the tape sits atop—Avendon’s influence perhaps. A similar image, from the same photoshoot no doubt, can be found on the actual packaging of the hair tape. Both images are art, made by an artist, despite their distinct forms and intentions. Art and advertisements differ, primarily, in aim. Images like Cheryl Tiegs Hair Tape can exist in both worlds, as many of the advertisements shown in the MoMA’s exhibition can serve a double purpose — as art and a compelling sales tool. Despite the tense relationship, advertisements and art seem to only grow closer and closer. Without a doubt, we will see more art objects in museums that serve a double function and continue to blur the line between two already ambiguous fields.

Photographer: Janelle Rodriguez

Teaching, though rewarding, was demanding. “You’re responsible for your students’ wellbeing all day—emotionally, physically, everything,” Emily said. “I loved it, but it was exhausting. So many days I wasn’t teaching—I was managing crises.” When she and her husband moved to the Clinton area, she decided to take a step back from the classroom. Her mother encouraged her to look at local colleges for job opportunities. “I checked the website and saw a position for ‘Art Museum Educator,’ and I thought, Would love to! It just made perfect sense. I had no idea these kinds of jobs existed.”

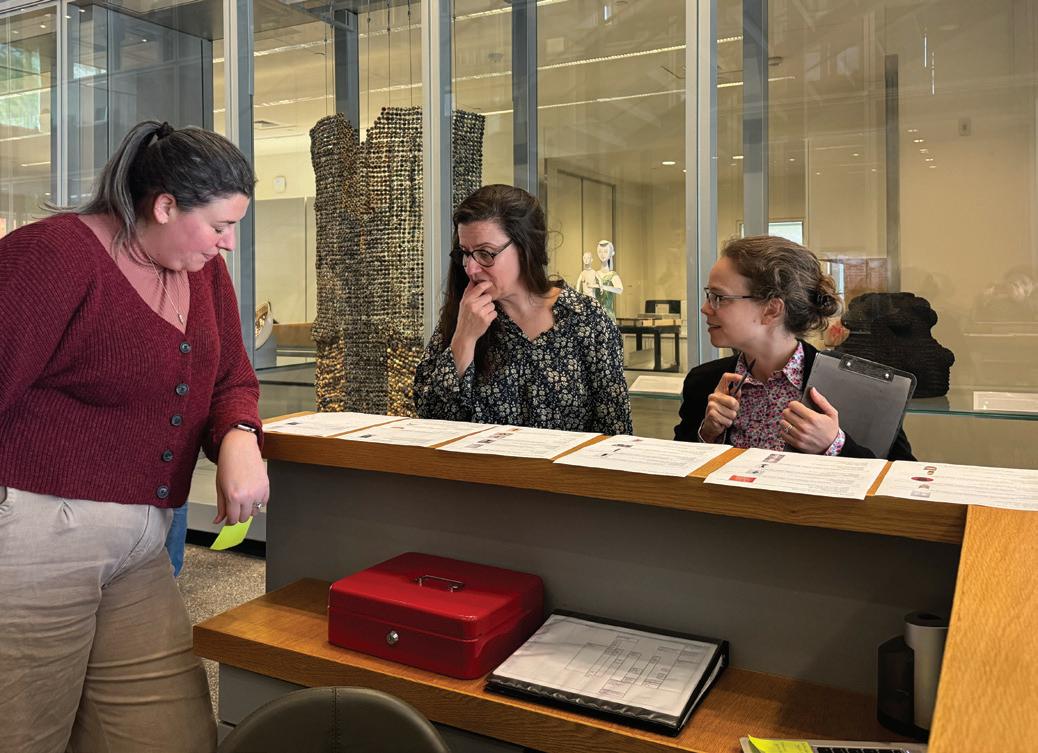

In September 2024, Emily Girard joined the Wellin Museum staff as Education Assistant and Office Coordinator. Over the past year, the Wellin community has watched her grow as she brings energy, compassion, and creativity to every project she touches. Recently, the Collection Magazine team sat down with Emily to learn more about her journey from the classroom to the museum, her love of crafting and gardening, and what makes Clinton feel like home.

After earning her undergraduate degree in anthropology from Haverford College, Emily returned to her hometown of Plattsburgh, New York, where she taught ninth and tenth-grade history at Beekmantown High School. “Everyone used to ask me what I was going to do with an anthropology degree,” she said. “I wasn’t super interested in researching artifacts like an archaeologist—I was always more into people, which is why I studied cultural anthropology and went into teaching.” She added that as a kid she went back and forth between being an art teacher and a singer. We’re glad she chose teaching.

Emily started part-time at the Wellin, working closely with the education team on K–12 programs. Her background in public education proved invaluable. “One leg up I had was knowing the New York State standards,” she explained. “Teachers have to show what standards a field trip hits for it to be approved, so I could help with that right away.” It was a skill set that complemented the team perfectly.

Her dedication and versatility quickly became apparent. When the opportunity arose to combine her education role with administrative responsibilities, the Wellin rewrote the position to fit her strengths. “It meant so much to me,” Emily said. “They did all that work so I could stay here full-time. I felt and still am so supported.”

Now, Emily divides her time between education programming, office coordination, and event planning. “I think of my role in thirds,” she said. “A third education assistant, a third managing the office, and a third event coordinating. I love that no two days are the same.” Emily continued, “I love the days when we have programming here, and I also love the days when I can sit on my computer and just dive into a spreadsheet.”

One of Emily’s goals is to expand the Wellin’s programming to include adults and senior citizens—a development we are excited to see come to life.

Outside of work, Emily brings that same creative spirit into her home life. “What don’t I craft?” she laughed. “My husband and I DIY everything in our house. I love making things look the way I want using whatever materials I have.” She used to paint often in college—“flowers mostly,” she said—finding the act of painting as much an emotional outlet as a hobby.

These days, her creative energy goes into her garden. “When we moved to Clinton, we suddenly had land—and the world was my oyster,” she said with a grin. “We’ve planted over a hundred trees and shrubs, plus three raised flower beds. Gardening makes me happy, and it’s my responsibility to take care of my mental health. I see it as an investment in my future happiness.”

When not working in her garden, she can be found watching the Vampire Diaries. “I never watched the series the whole way through, I finally am and I love it. I was definitely team Stefan at the beginning,” she said.

Clinton, she added, has been a delight. “I’m from the middle of nowhere, and I always knew I wanted to go back to the middle of nowhere,” Emily said. “Having open air has always felt really peaceful. I love trees, my yard, my flowers. I love being by myself with my small family and our two Australian shepherds.” She laughed as she described the local farmers market, Lucky Dog Bistro, and Utica Coffee as “little gems I was not expecting.” She was only expecting a post office!

When asked about her long-term goals, Emily didn’t hesitate. “I have no desire to leave the museum world,” she said. “I love the Wellin. If I

ever moved on, it would only be to the Strong Museum of Play in Rochester—it’s like a mix between an amusement park and a museum. It’s magical.”

As we wrapped up, Emily reflected on Jamea Richmond-Edwards: Another World Yet the Same, the Wellin’s current exhibition. What excites her most, she said, is sharing the artist’s journey of self-confidence and selfrepresentation. “I love how Jamea’s figures became more personal over time—how she gained the confidence to paint herself as herself,” Emily said. “That growth and self-assurance are things everyone can relate to. Figuring out who you are is hard, but it comes with time and support. I want young people to know that.”

For Emily, the Wellin has been more than just a workplace—it’s a space where her love for art, education, and people have all found a home. “I kind of stumbled into this,” she said, “but now I can’t imagine being anywhere else.” So far, Emily has planned nine docent and community events, been part of 18 K–12 visits and Wellin Kids, and organized 29 public programs and 35 campus events.

When asked for her biggest accomplishment, Emily concluded, “I’m proud of the person that I've grown into. I’m proud of how much I care for other people and things that don't affect me directly. I want everyone to have the opportunity to have a good life and feel cared for.” We’re proud of her too, and grateful that she is part of our Wellin community.

A title can reveal details about an artist’s process, experience, or intention. Some titles are direct, anchoring the viewer’s expectations in recognizable subjects, colors, or settings. Take Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night (1889) for example. From the title alone, the viewer anticipates a nocturnal scene—swirling stars illuminating the darkness. Van Gogh’s painting fulfills that expectation, forging a clear and satisfying link between name and image. It is a promise kept between artist and viewer. But what happens when that promise is unfulfilled? Why would an artist choose to subvert expectation by naming a work in a way that obscures rather than clarifies?

Ambiguity in titles can serve many purposes. It might preserve the anonymity of a subject, gesture toward a more abstract idea, or leave interpretation open-ended. In these cases, titling becomes its own act of creation—an extension of the artwork rather than a label for it. This raises key questions: Is the act of titling itself a creative gesture? Is it on par with making the work? What power lies in calling something Untitled? Does a title that explains or entices help a work to endure?

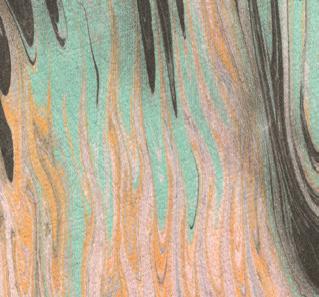

Comparing works that align with their titles to those that seem misaligned highlights the expressive potential of naming, as we can see in several examples of artworks in the Wellin Museum’s collection. Robert Motherwell’s Springtime Dissonance (1980), an etching and aquatint, contrasts a stained yellow-green field with jagged black contours that suggest multiple interpretations—a natural form, such as a bird or branch, or possibly an architectural entity, like a floor plan or a staircase. The word “dissonance,” evoking musical discord, creates an abstract visual echo, but the use of the word “springtime” pushes the viewer towards imagery from nature. Meanwhile, Corita Kent’s this beginning of miracles (1953) offers a softer ambiguity. Her screenprint, resembling a patterned Persian rug, is composed of layered vignettes that hint at narrative and ritual. We glimpse an obscured figure holding a chalice, but the “miracle” remains elusive.

Ambiguity extends beyond printmaking into painting as well. Dorothy Shakespear’s War Scare (1914) offers a striking example of a title that bears little visual relation to the work itself. The composition is dominated by a cool blue background that might suggest open sky, with angular, abstracted forms rising like skyscrapers. Nothing in the image conveys the chaos, violence, or tension implied by the title. Instead, War Scare is serene, geometric, and introspective—qualities seemingly at odds with wartime anxiety. Painted in London at the onset of World War I, shortly after Shakespear’s marriage to poet Ezra Pound, the work may reflect the industrial urban environment surrounding her. Yet the looming black and gray square in the upper left corner, while visually weighty, offers only the faintest echo of menace. The disconnect between name and image invites speculation: is Shakespear’s “war scare” psychological rather than literal—an unease rendered through abstraction rather than narrative?

An even more ambiguous example appears in Christoph Schellberg’s I Will Drive Slowly (2017). Despite its title, the work depicts neither a vehicle nor a journey, but rather a flag-like abstraction. The painting is especially intriguing for its quiet negation of the human presence it names: the “I” of the title vanishes within a field of pastel color dominated by a single black triangle.

This idea extends beyond painting and printmaking into other mediums as well. Consider Al H. Qöyawayma’s terracotta vessel—what does it mean to name a functional object? The title In the Beginning evokes origins, continuity, and return. Its spiral motif suggests both movement and timelessness, reminding us of cyclical beginnings and the enduring nature of creation itself. According to the artist, the vessel embodies “the mystery and timeless beginnings of the Hopi,” symbolized by the impression of an ammonite fossil. The artist explains that the spiral represents “timelessness,” radiating outward to encompass humanity’s earliest origins within prehistoric structures. The carved doorway serves as a metaphor for passages—our entrances and exits through life’s experiences. The vessel’s smooth, balanced form and serene profile convey a sense of peace and harmony, reflecting the calm, contemplative spirit of the Southwest.

Another example of ambiguous titling appears in Betty Parsons’s wooden assemblage House Store (1977). Composed of seven painted wooden blocks, some rectangular, others wedge-shaped, the sculpture bears little resemblance to either a house or a store. Parsons created such constructions from driftwood that had washed ashore beneath her Long Island studio. She explained, “All of my wooden pieces were shaped by the hand of man. They were pieces of houses or docks or boats or signs. And something happened and they were lost. . . . And then they washed ashore, broken and changed, and I find them.” In this way, Parsons drew her inspiration from found materials and the world around her. The title House Store thus deepens the work’s ambiguity. It may allude to the origins of the wood itself, once part of man-made structures, or to a structure Parsons perceived within the abstract composition.

One through line connecting each of these works is their position within the modern and contemporary genre. This sample of the Wellin’s collection, then, invites further research into the history of naming artworks to see if this ambiguity indeed begins in the period of the avant-garde and abstract expressionism. While we can make generalized assumptions about how artists title their work, the answer often lies in the viewer’s own experience with the work before them.

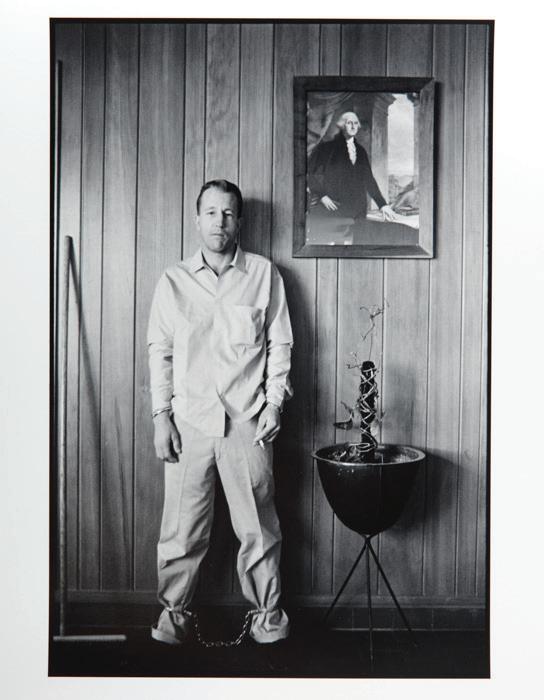

Photographer Danny Lyon made his career by photographing outsiders—prisoners, bikers, protesters, outlaws, racers, and rebellious youths. Looking where others shied away, Lyon found compelling subjects and compositions which earned him acclaim over the course of his relatively short photography career. Committed to capturing the reality of non-conformists, Lyon’s images define his era not in neat easily digestible packages, but as a transitory time where people and things seemed to be fraying at the edges.

Born in 1943 to a middle class family, Danny Lyon attended the University of Chicago as a history major. In Chicago, Lyon began to study photographic images from the Civil War along with photographers like James Agee and Walker Evans. Influenced by this photographic lineage, Lyon went out into the world looking for subjects. In 1962, before graduating, Lyon traveled to Georgia to photograph civil rights demonstrations. Here he became a member and photographer for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). For Lyon, SNCC was just the start. Turning towards Chicago biker gangs, white nationalists, and the destruction of Lower Manhattan, the photographer finally looked to the East Texas prison system in 1967.

For 14 months between 1967 and 1968, Danny Lyon spent his time photographing inside six Texas prisons. Aligned with contemporary writers like Truman Capote and Hunter S. Thompson, Lyon was a pioneer of ‘New Journalism.’ He dedicated himself to immersion in the environment— creating close personal relationships with prisoners and spending extensive time within those four walls. The product of his project was , a photobook containing images of prisoners, official documentation, and writing and drawings from the inmates themselves.

This photo, , is one of many that communicates Lyon’s hauntingly intimate experience documenting the prisons and engaging with their residents. Captioned without the prisoner’s name, only his circumstance, the viewer is confronted by the man’s penetrating gaze. Unflinching, casual, and resigned, he loosely holds a cigarette between his fingers. His pants pucker where shackles bind his ankles. Behind the prisoner, a painting of George Washington looms, reminding the viewer where we are—the offices in a high-security prison.

Lyon’s personal relationships with the inmates was pivotal in the making of

Not only did the photobook include Lyon’s work, it was coupled with letters and artworks by inmates. Throughout the project, Lyon developed a close relationship with prisoner Billy McCune. McCune’s poems, writing, letters, and drawings are wrapped up in the pages of the book, providing devastatingly personal insight into the lived experience of the men trapped inside. Often imprisoned for extended periods of time for relatively small crimes, McCune tells the stories of his fellow inmates. Their lives are regimented, surveyed, and controlled, and Lyon often captures the inmates in formation ready to march off to work or back to their confines.

Always haunting and thought-provoking, Lyon’s work rejects detached photography, opting instead to dive into the deep-end head first. Personal relationships and emotional and physical closeness with subjects, is what makes Lyon’s work so powerful, and allows us to get a glimpse into someone else’s world—a world that we wouldn’t have seen without Danny Lyon.

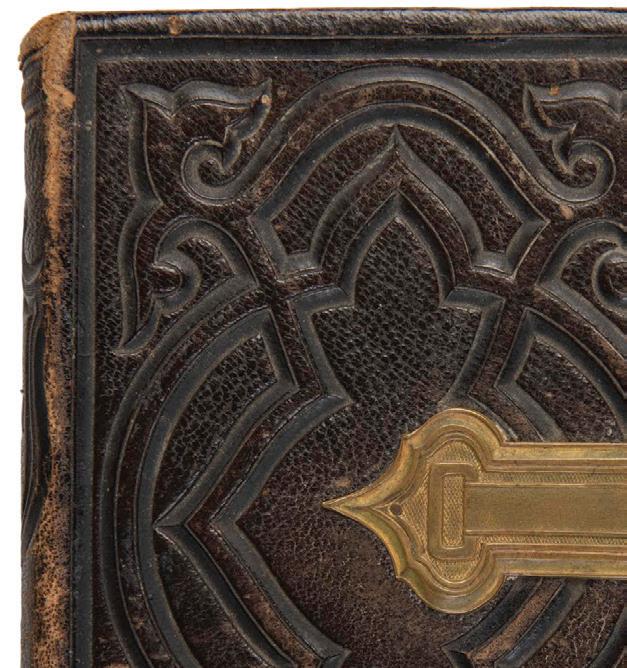

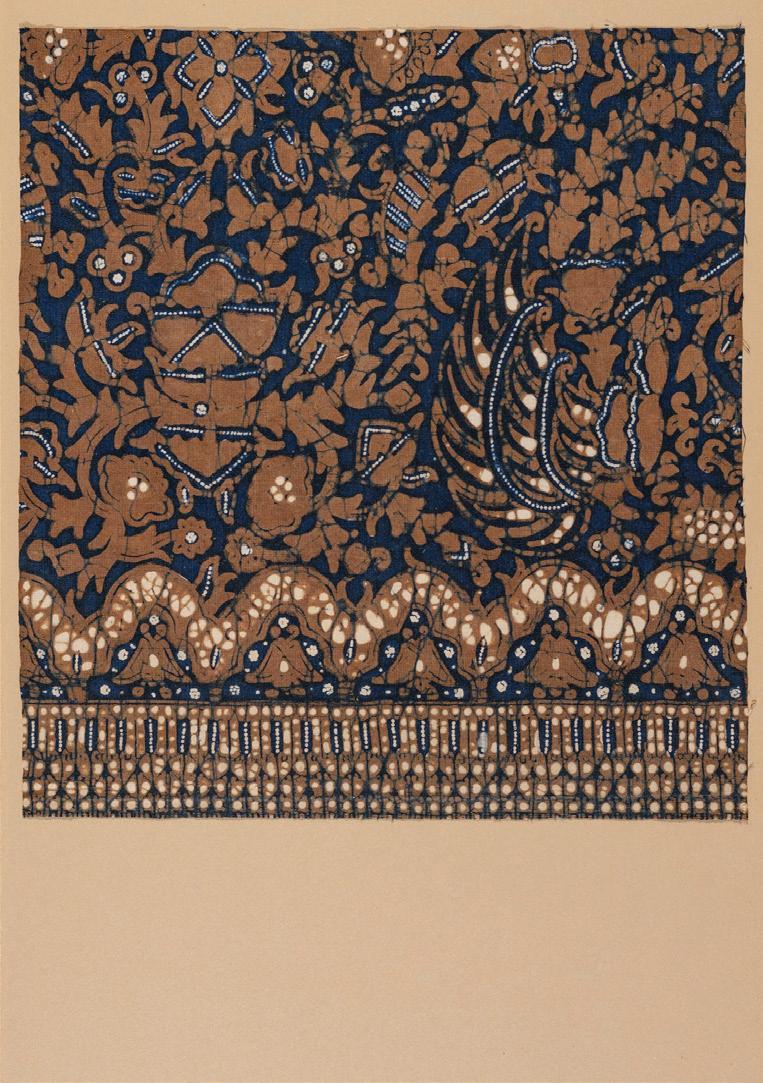

Encompassing almost 2,000 objects within the Wellin’s collection, the museum’s Study Collection serves as a resource for Hamilton College, furthering education through close engagement with objects. Materials in the Study Collection allow students and faculty to explore the techniques, histories, and physical qualities of objects through the direct examination and handling of objects. Selected for their educational value, with a consideration for rarity and conservation status, the materials provide a tangible link between theory and practice, providing opportunities for experiential learning, interdisciplinary inquiry, and object-based study. Composed of a range of materials from photographs to textiles and archival documents, the collection is observed during class visits and guided sessions, serving as a dynamic educational environment that encourages curiosity, close looking, and appreciation for the objects themselves.

The Wellin Museum’s Study Collection composition lends itself to the illustration of the different photographic processes used in the nineteenth century, as many photographs and prints are housed within the collection. This particular album contains tintypes, albumen prints, gelatin silver photographs, and small cartes de visite. It was purchased from a local antique shop specifically for the Study Collection in 2021. Composed of photographs of varying individuals, photo albums provide a window into how nineteenth century photographic albums functioned as carriers for multiple processes and formats as pedagogical or display objects. Parts of the album were likely mass produced, such as the binding, page layouts, and mounting apertures, whereas the ordering of photographs, inscriptions, and mountings were likely personal, handmade features. Collecting various photographic processes side by side, as seen in the album, serves to illustrate the differences between them in terms of visual effects, tonal ranges, and material characteristic.

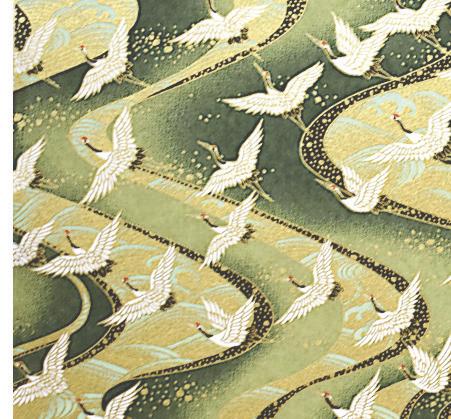

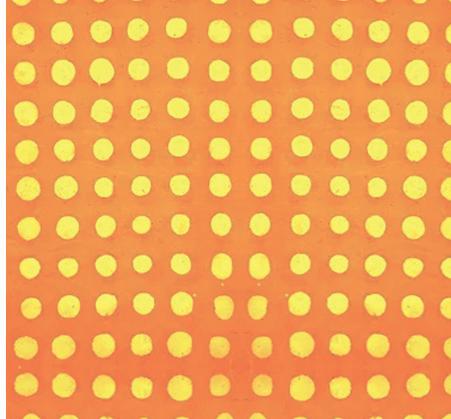

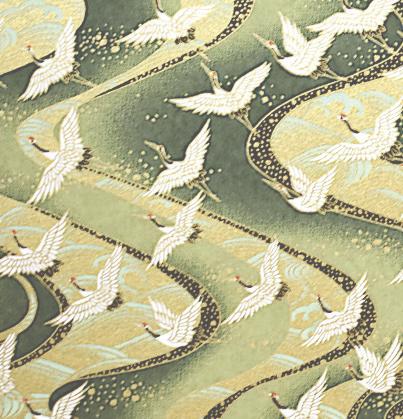

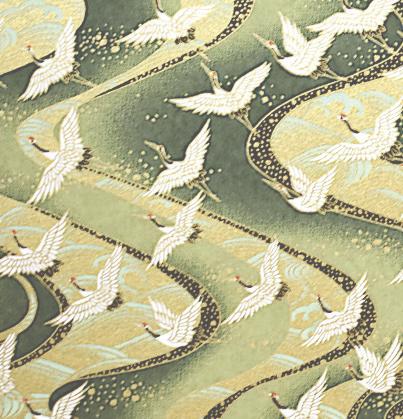

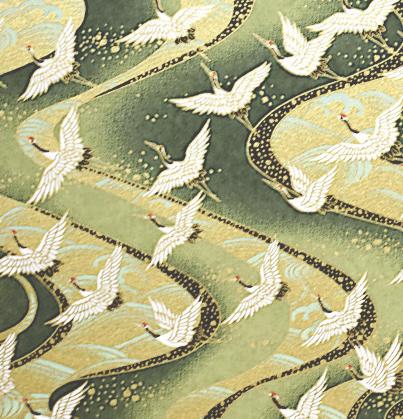

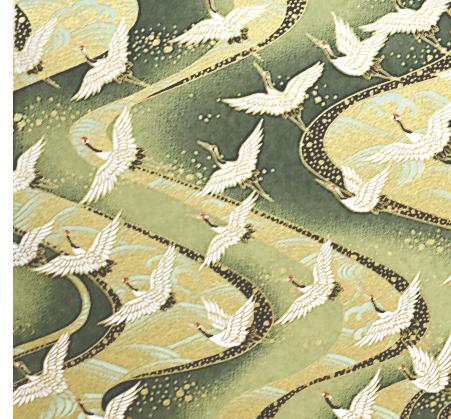

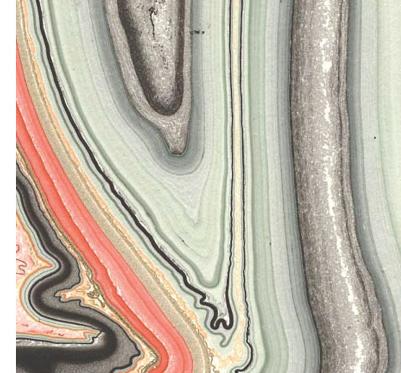

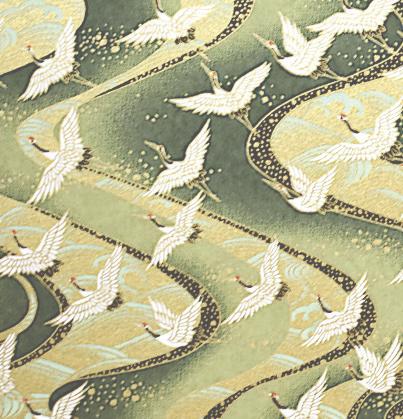

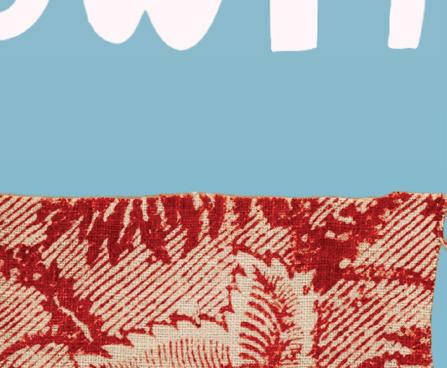

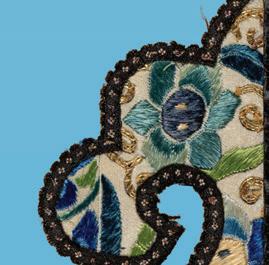

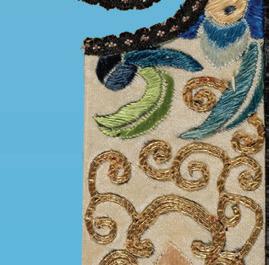

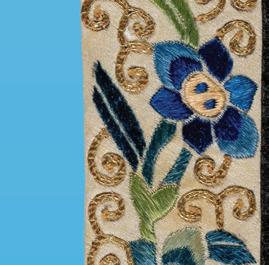

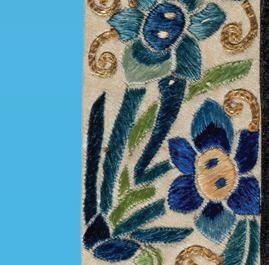

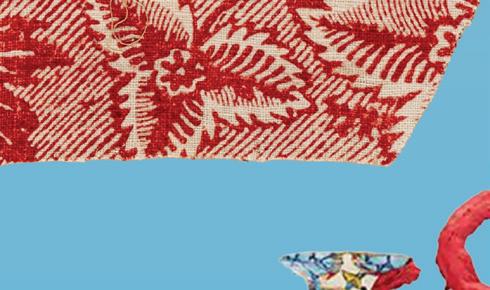

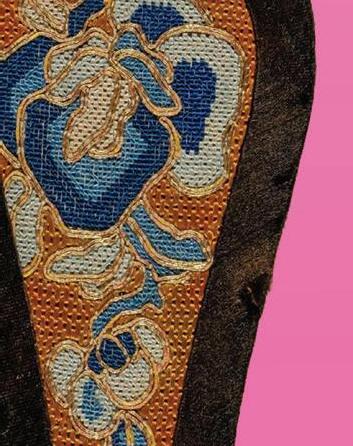

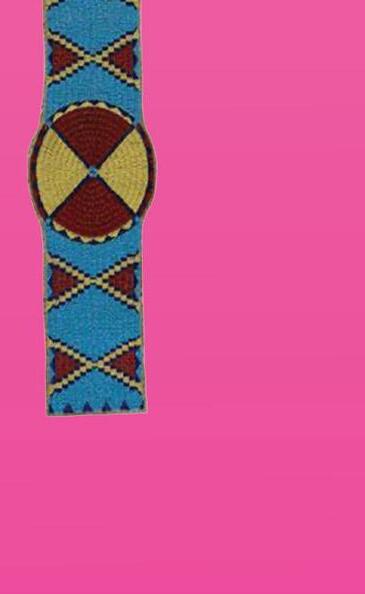

Accessioned with the intention of becoming a part of the Study Collection, the series of textiles held at the Wellin were donated by the Carnegie Corporation, originally from the Eliza M. and Sarah L. Niblack Collection.

The fabrics were donated to educational institutions roughly around the same time period as Carnegie was constructing libraries across the country. The textiles were initially collected by the Niblack sisters in Chicago, obtained from their brother, a well known admiral in the Navy, who collected a variety of garments from his time sailing around the world.

Andrew Carnegie acquired the fabrics for educational purposes, the goal of the collection being to explore and appreciate what different cultures created and how they produced them. However, The Carnegie Corporation cut the garments into smaller pieces in order to share the physical fabrics with more institutions, effectively removing the cultural context and understanding of the original function of the fabrics.

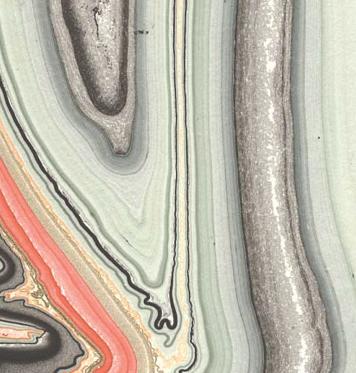

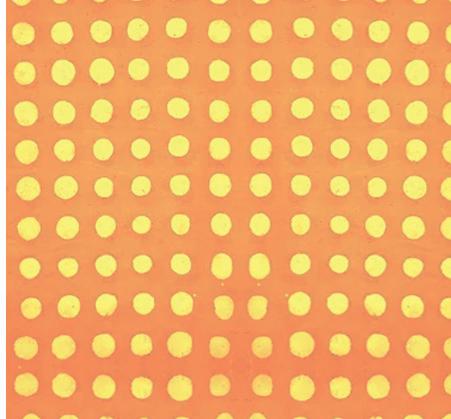

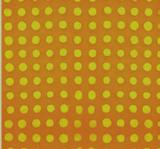

Some textiles in the series originate from organic materials such as straw, grass, or tree bark with pigment, and therefore do not classify as fabrics. This specific textile pictured here uses a wax resist dying technique called Batik, originating from the island of Java in Indonesia between the 18th and 19th centuries. The larger group of textiles now serve in the Wellin’s Study Collection to further the understanding of different cultures and their histories.

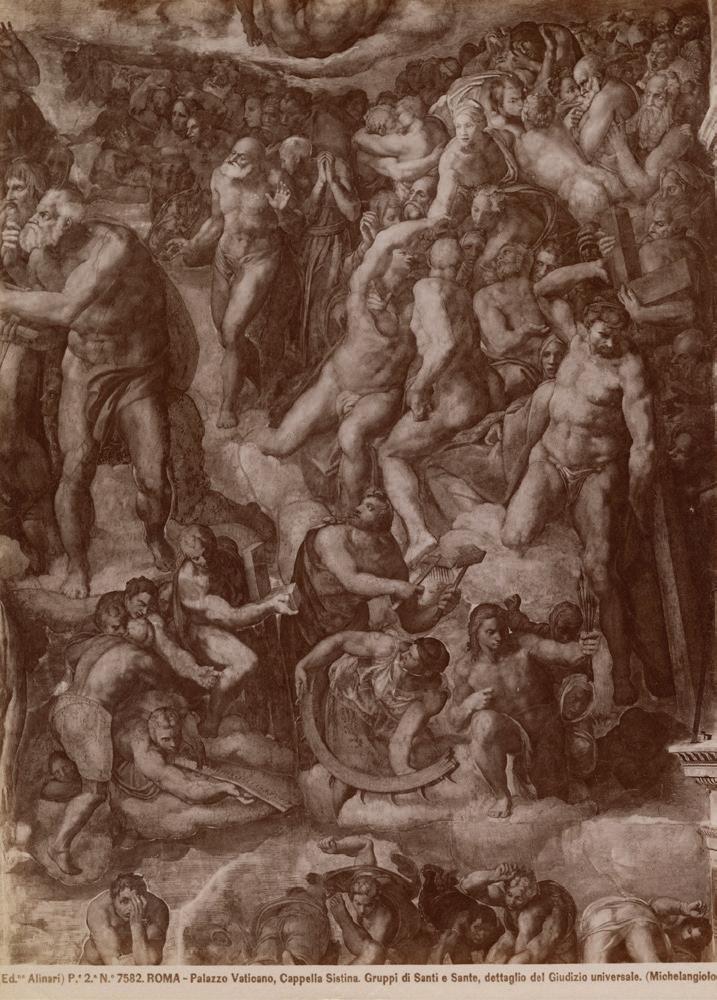

These photographs in the study collection collection were donated by James Garfinkel, Class of 1980. He gifted more than a thousand prints representing the later phase of the Alinari firm’s photographic production. These images are part of the massproduced visual culture of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Founded in Florence in 1852, Fratelli Alinari is among the world’s oldest photographic studios and was central to the distribution of artwork reproductions and architectural views across Europe. Travelers often purchased such photographs as mementos of sites they had visited, or received them from friends and family who had undertaken similar journeys. Typically, these prints were mounted in albums or scrapbooks, making it unusual to encounter such a large number of unmounted examples.

The photographs are thin albumen prints—extremely delicate, light-sensitive objects that require careful handling. To ensure their longevity, institutions such as the Wellin Museum mat prints using archival photo corners before display to protect them and facilitate viewing. However, the photographs in this collection remain unmatted, as they are not currently slated for exhibition and mounting all 1,113 prints would be cost-prohibitive.

The images primarily depict works of art and architectural subjects—such as the Sistine Chapel and the Vatican Palace—photographed using large wooden cameras on tracks with glass plate negatives. Most date to around 1880, with later examples extending into the 1910s, coinciding with the period when the Alinari firm was most active in marketing its large-format photographs to the public.

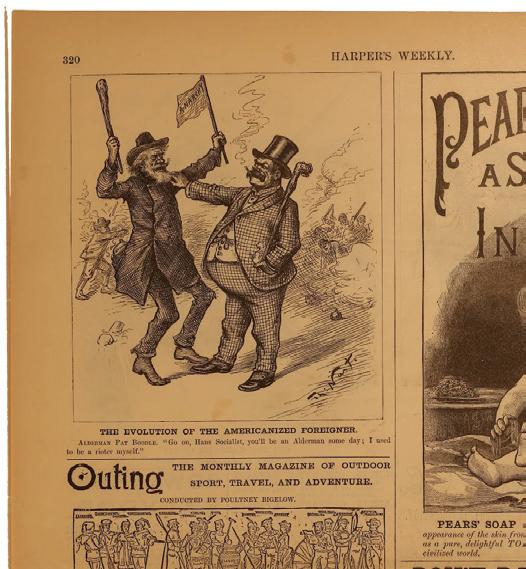

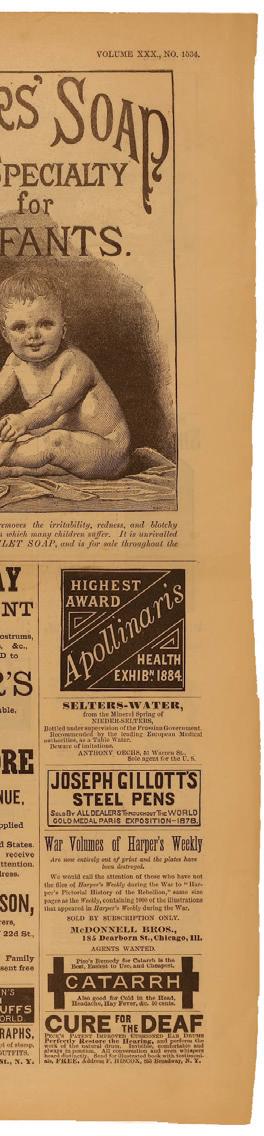

This issue of Harper’s Weekly was donated by Professor Emeritus Jay Williams, Class of 1954, as part of his broader interest in nineteenth-century graphic works. Printed on acidic, wood pulp–based paper, these periodicals were not made to last— reflecting their role as mass-produced, disposable media rather than enduring art objects. Their survival today offers valuable insight into the visual and political culture of the late-nineteenth century.

The issue includes illustrations by Thomas Nast, one of the most influential political cartoonists of the era, featuring works such as The Chinese Puzzled, The Evolution of the Americanized Foreigner, and Oh! The Garland of It imagery reflects the complexities and contradictions of American identity in this period: his cartoons often combined biting satire with deeply ambivalent or exclusionary portrayals of immigrants and racialized groups. Viewed today, these prints illuminate both the persuasive power of illustrated journalism and its role in shaping public opinion during the Gilded Age in the decades following Reconstruction.

. Nast’s

While the front of each page carries the primary published content, the reverse sides often feature equally compelling imagery, offering rich material for interpretation and study. For this reason, the piece is housed in the Wellin Museum’s Study Collection, where it can be examined and discussed in an educational context.

The Wellin Museum’s Study Collection serves the larger educational community by providing objects and artworks, such as the ones highlighted, and enhances understanding by allowing a hands on learning experience with such pieces.

Afrofuturism is a cultural movement that envisions the future through the experiences of Black people, blending science fiction, fantasy, and history. At its core, Afrofuturism challenges dominant Western narratives of progress and modernity by imagining worlds where Black communities lead innovation and liberation.

Cultural critic Mark Dery coined the term Afrofuturism in his seminal 1993 essay “Black to the Future.” He describes it as:

Jamea Richmond-Edwards pushes the boundaries of Afrofuturism in her vibrant paintings and collages. In the painting In Search of Mu, she brings Dery’s concept to life through a vivid visual narrative. Using acrylic, ink, glitter, graphite, rhinestones, spray paint, and mixed-media collage, she centers Black women and families in imagined futures rooted in ancestral memory. The central figure—a selfportrait of the artist—stands resolute, embarking on a journey to Mu, the legendary lost Pacific continent linked in Hawaiian folklore to the Pleiades star cluster. The painting blends science fiction, fantasy, and history to imagine liberated futures, reflecting RichmondEdwards’s personal resilience as she navigates parenthood alongside her artistic ambition. Its shimmering surfaces and layered textures evoke wonder and spiritual depth, demonstrating that Afrofuturist visions are intimately connected to memory, ancestry, and lived experience.

Jamea Richmond-Edwards’ work draws on the Afrofuturist cosmology of jazz musician Sun Ra—whose “Space Is the Place” monologue appears in her film Ancient Future. Inspired by his cosmic philosophy, she merges ancestral pasts with speculative futures to construct visionary Black worlds. This fusion becomes a transformative framework that reclaims Black presence across space and time and imagines Black freedom through myth, futurity, and cosmic possibility.

Akili Ron Anderson’s work, featured in EXODUS, also engages with Afrofuturist ideas. Anderson celebrates Black culture, history, and community while imagining futures of empowerment and cultural affirmation. Drawing on his experiences with the AfriCOBRA collective, he emphasizes bold color, rhythmic composition, and symbols from the African diaspora to inspire and uplift Black audiences. As Anderson explains in his artist statement, his goal is to create “a cultural mirror” that uses art not only for beauty but as a source of nourishment, grounding, and inspiration.” By evoking emotion, memory, and social connection, his work aligns with Afrofuturism’s mission to center Black experiences and imagine worlds where Black communities flourish.

Together, the works of Jamea Richmond-Edwards and Akili Ron Anderson demonstrate that Afrofuturism is more than a visual style—it is a framework for reimagining Black life, history, and possibility. Their art invites viewers to envision worlds where Black communities thrive and imagine new futures.

When I was a kid, I used to beg my parents to buy whatever the newest cereal was at the grocery store. Not because I was particularly a big fan of cereal, but because I was, and still am, a huge fan of trinkets. A new cereal typically meant a new prize stuffed somewhere inside, and I was determined to collect them all (or, less ambitiously, as many as I could get my hands on). As much as I would like to believe my cereal-prize craze was one of a kind, marketers have been taking advantage of this urge since the early 1900s.

In the mid-1800s, after the advent of photography, Oliver Wendell Holmes improved and popularized the stereoscope—an inexpensive handheld device that was an early predecessor to the modern camera. When someone put a stereograph containing separate left and right photographs of the same scene into the stereoscope, the image emerged as 3-D. The American Stereoscopic Company, active from 18901915, produced and sold stereographs—often featuring impressive monuments or breathtaking views that people could not afford to visit in person.

In 1906, the American Stereoscopic Company partnered with Quaker Oats Company to produce their “Around the World” series. As part of this series, American Stereoscopic Company hid different stereographs in packages of Pettijohn’s Breakfast Food, like the stereograph pictured here. This stereograph shows pedestrians at a marketplace in Santiago, Cuba. On the right side of each stereoscopic view, a woman stands wearing a purple skirt and a maroon shawl, holding a basket. She glances down at two children in front of her: a young boy wearing an all light blue outfit and a slightly older girl wearing a pink pattern dress and holding a basket. The two stereoscope views are framed by an offwhite border: the left credits The Quaker Oats Company of Chicago, Illinois, as the issuer, while the right notes that it derives from an original stereograph copyrighted in 1906 by the American Stereoscope Co., New York.

On the stereograph’s backside, the American Stereoscopic company describes their “Around the World” series as “Without Leaving Your Home—Just Like Being There.” Viewers could slide a stereograph into a stereoscope and suddenly see National Parks or a faraway landscape they might otherwise only have imagined. This sentiment demonstrates photography’s power not just to grab a viewer’s attention, but to suspend them within the image itself.

Photography had already become well established by the time this stereograph was produced. In 1888, George Eastman had introduced the Kodak camera—so user-friendly that its slogan promised, “You press the button, we do the rest.” It is curious, then, that stereographs like this one were still being produced in 1906. Perhaps it was an attempt to keep an aging technology relevant, or a testament to their enduring popularity. This stereograph clearly illustrates the advances and limitations of photography. Its images possess shadows and depth, yet they are also distinctly hand-tinted, produced before the widespread use of color photography. From its earliest days, the history of photography was bound up with commercial strategies—finding ways, as with these stereoscopes, to encourage consumers: “Save these colored stereoscopic views from Pettijohn packages; arrange them into series and shortly you will have a library of World Tours of Original Views ” At the same time, they tried to expand their appeal to education, claiming that “such a collection or library of views is a great education for children.” This raises the question: what kind of education can be gleaned from this stereoscope or others in the same “Around the World” series?

From stereoscopes in oatmeal boxes to the prizes tucked into the cereal I grew up discovering, the strategy remains the same: entice people with the promise of something beyond the product itself. These stereoscopic cards remind us that photography was never only about seeing—it was also about selling, collecting, and imagining new worlds.

Kenna Smith ’26 & Ellie Roberts ’26 working on their Student Assistant shifts

Nawar Kazi ’27 answering questions about the artwork after a Hamilton College class visit

Annie Pearson ’27

working her Greeter Desk shift

Education Manager

Marjorie Hurley, Collections

Curator Elizabeth Shannon, and Office Coordinator and Education Assistant Emily Girard designing a class tour

Carter Megalli ’26 designing a craft for a Wellin Open Studio Event

You’ve probably seen them around dressed in all black, moving in mysterious little packs between the Wellin and McEwen. Are they part of a secret society? A performance art collective? Just really committed to minimalist fashion? Not quite. They’re the Wellin Museum’s student docents: the ones giving tours, chatting about art, and somehow balancing class, work, and caffeine dependency all at once. If it weren’t for the museum, they’d be eating meals at normal hours and getting a full night’s sleep. Probably.

Technically, its “professional attire,” but the aesthetic does give off a faintly intimidating energy. Think less “goth club” and more “art history final at 9 a.m.” Still, it works—black hides coffee stains and looks great in museum lighting.

For reasons no one fully understands, McEwen is the unofficial docent dining hall. Commons may be closer, but somehow it just doesn’t have the same vibe. Maybe it’s the lighting. Maybe it’s the soup. Either way, you’ll find them there talking about an exhibition while eating vegan chili.

So, next time you see a cluster of black-clad students walking across campus with tote bags and slightly frenzied eyes, don’t be intimidated. Say hi. They might tell you something interesting about art or at least recommend you a good coffee spot. Either way, they’re essential to the life of the Wellin, and we wouldn’t want it any other way.

Sydney Cagnetta

Since its invention in the 1800s, photography has evolved into a widely accessible means of producing art, with the mass production of digital cameras, cell phone cameras, and photograph editing software. Not even 200 years ago however, photography had just begun to emerge as an artistic medium, requiring hours of work and the manipulation of expensive, sometimes dangerous materials to produce a single photograph. Today, the ability to take a photograph, which is essentially the act of capturing light as it enters a lens, requires low effort and material. The Wellin Museum of Art’s collection holds thousands of photographs that illustrate this historic progression, from the earliest photographic forms to digital imagery.

In 1839, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre published the first photographic process: the daguerreotype, a handheld, high clarity, positive image on polished copper tucked into elaborate casings. A positive refers typically to the final version of a photograph that reflects the same tones as the original scene being captured, with light areas appearing light and dark areas appearing dark. The daguerreotype process included the copper being thinly coated with silver, exposed to iodine, placed in the back of the camera, and fi xed with mercury fumes. Daguerreotype of Dog is a 1/9 plate daguerreotype taken in 1855 by an American photographer. By this time, the addition of bromine to the process allowed for a significant reduction in the exposure time, ranging from seconds to just under a minute. Capturing animals in photographs remained

difficult, oftentimes lending photographers to use taxidermied animals, making this reproduction of a sleeping dog unique in nature.

Simultaneously, British photographer Henry Fox Talbot was developing the first negative-positive photographic process, published officially in 1841 as the salt paper calotype. Photo negatives are defined as an intermediate stage in the photographic process, where the tones of the scene being captured are reversed, allowing positives (images with the true tones) to be produced from the tonally reversed image. The negative was produced on paper by coating it with silver nitrate and potassium iodide, which was then sensitized, exposed, and fi xed, then placed onto another piece of sensitized paper and exposed to sunlight to create a positive. Characterized by their hazy,

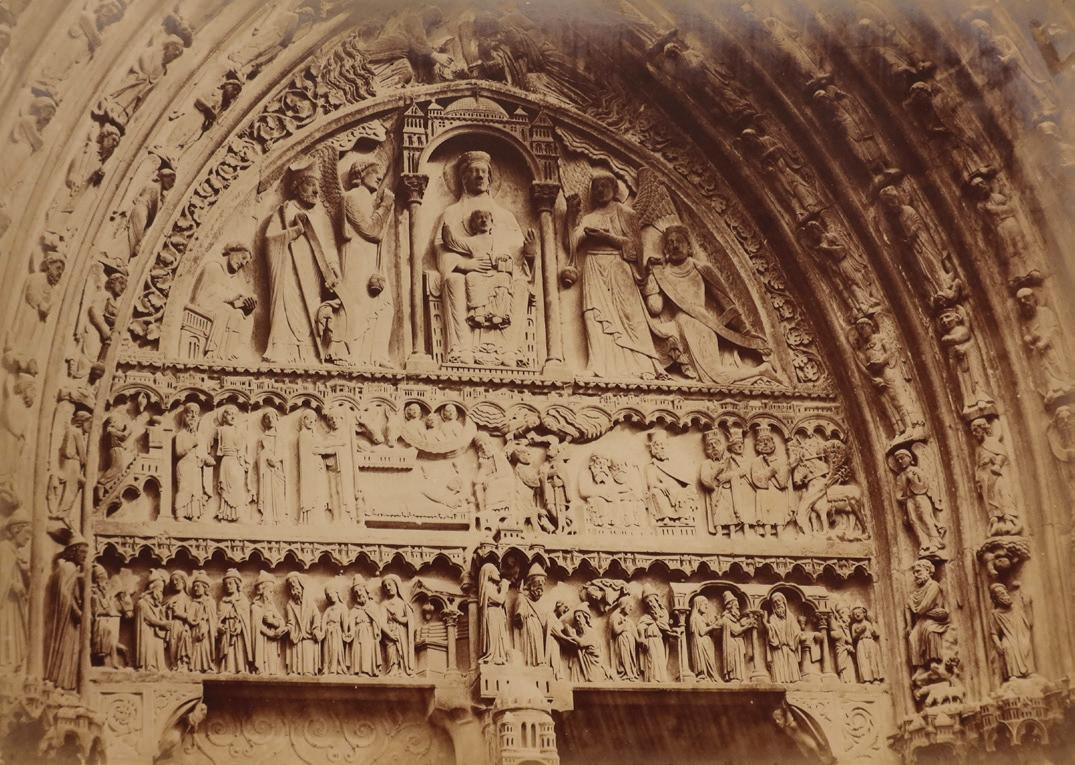

amber-toned appearance, calotypes allowed for multiple prints to be made from a negative. The salt print from a calotype Ensemble du Timpan was taken by Bisson Frères in 1850, capturing one of the front archways of the famed cathedral of Notre-Dame. The print rests in a collection of other calotype prints, of which the Wellin has one other print from the series, taken by the Bisson brothers depicting Notre-Dame.

The early 1850s brought about two major technological developments that changed the medium of photography altogether: the albumen print and the wet plate collodion process. Albumen prints were invented by Louis Désiré BlanquartEvrard in 1850, the process using egg whites to coat the fibers of paper to make a more stable, high contrast, detailed print. Frederick Scott Archer introduced the wet plate collodion process in 1851, a method of coating glass negatives with wet collodion, a thick liquid composed of nitrocellulose in alcohol and ether, and a layer of silver nitrate. The negatives were almost immediately exposed, then the photographer would develop, fi x,

and wash the plates before the collodion dried. Requiring less time and cheaper materials, while also allowing any number of extremely detailed, high clarity prints to be made from the negative, this became the predominant process. Men with elephant, Ceylon is an albumen print made from a wet plate collodion negative from 1880 taken by Charles T. Scowen, depicting one man riding a chained elephant while the other rests against its front leg. The photograph displays the high level of clarity produced by this process, while also demonstrating the fact that exposure times continued to endure for a few seconds with the blur of the elephant’s tail and trunk.

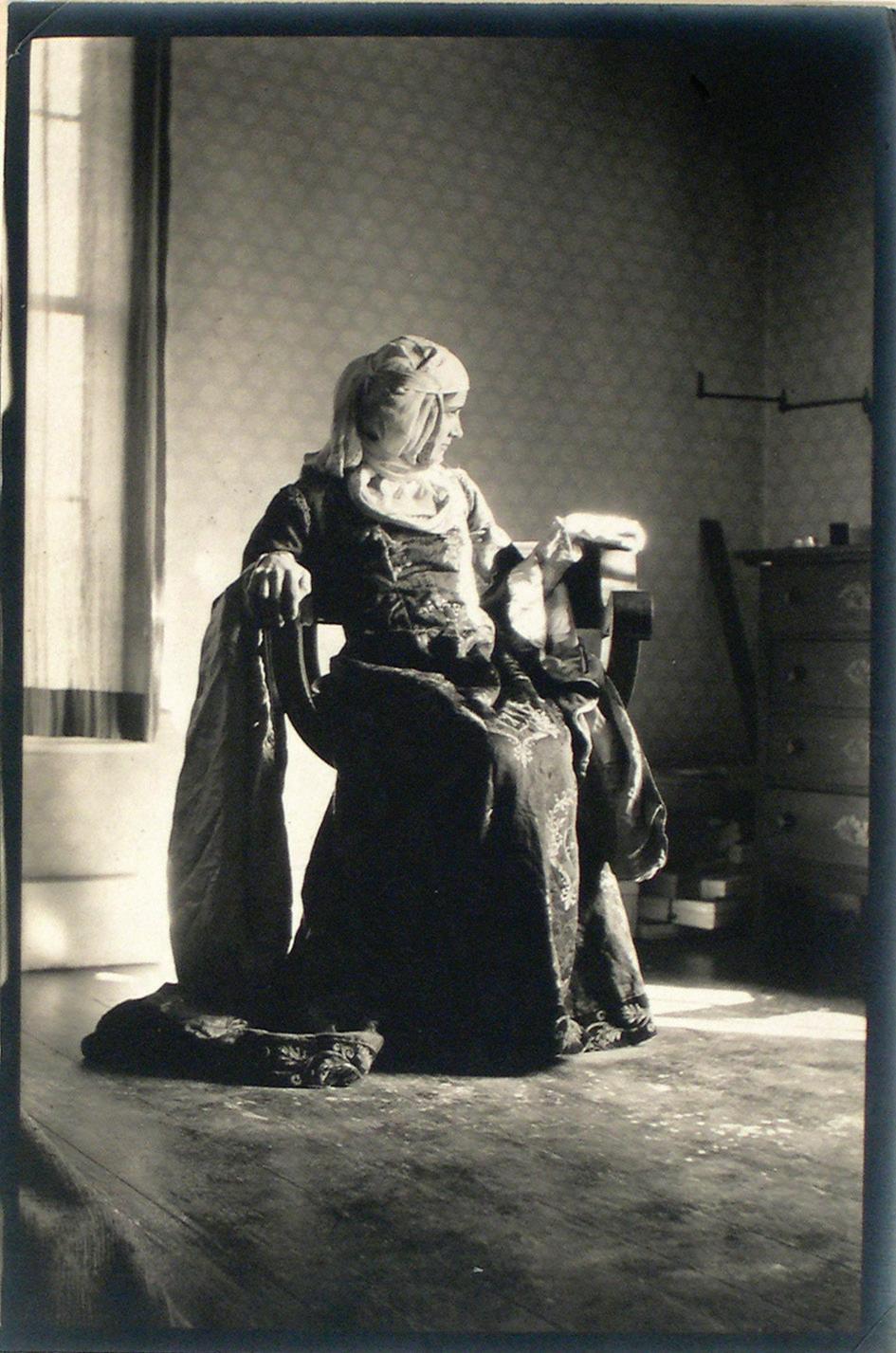

Invented in the early 1870s, the invention of both the dry plate negative and the silver gelatin printing paper greatly widened the reach of photographic accessibility. Dr. Richard L. Maddox invented the dry plate photographic process in 1871, coating glass negatives with a light sensitive gelatin emulsion and allowing them to dry prior to use, providing more stable negatives and leading to the mass production of dry plate negatives. The invention of the silver gelatin photographic process is difficult to credit to one individual, yet became one of the most important photographic printing inventions of the 20th century, due to its greater print stability, higher quality, and ease of use. Jessie Wilcox Smith took the photo Gertrude, Shakespeare before 1922 presumably in preparation for later illustrations by Elizabeth Shippen Green that used the photograph as reference. The photograph was taken prior to roll film, during the time of mass dry plate production, and held the purpose of illustrative reference. The print itself additionally has uneven darkened edges that come from

the sensitized emulsion on the glass plate. The combination of these factors point to this silver gelatin print coming from a dry plate negative.

Kodachrome, the first commercially successful subtractive color film, was developed by the Eastman Kodak Company in 1935. Subtractive color film refers to the dyes in the film absorbing certain colors from white light to produce an image. The process, initially developed for movie film, coated the film base with three emulsions, each sensitive to a different primary color. The dominant color printing process of the 20th century, also known as chromogenic printing or “C prints,” was used and branded by multiple different companies, including Kodak and Fuji. It emerged in the mid-1930s. The paper was coated with three different gelatin layers containing organic magenta, yellow, and cyan dyes that produced full color images, though they were prone to fading.

The photograph He’s a typical Californian who doesn’t know how to relax is a chromogenic print, likely from some form of color film, made by Bill Owens in 1971. The photograph belongs in Owens’s series that documented suburbia and how residents constructed their lives, aiming for direct and sensitive communication with his subjects.

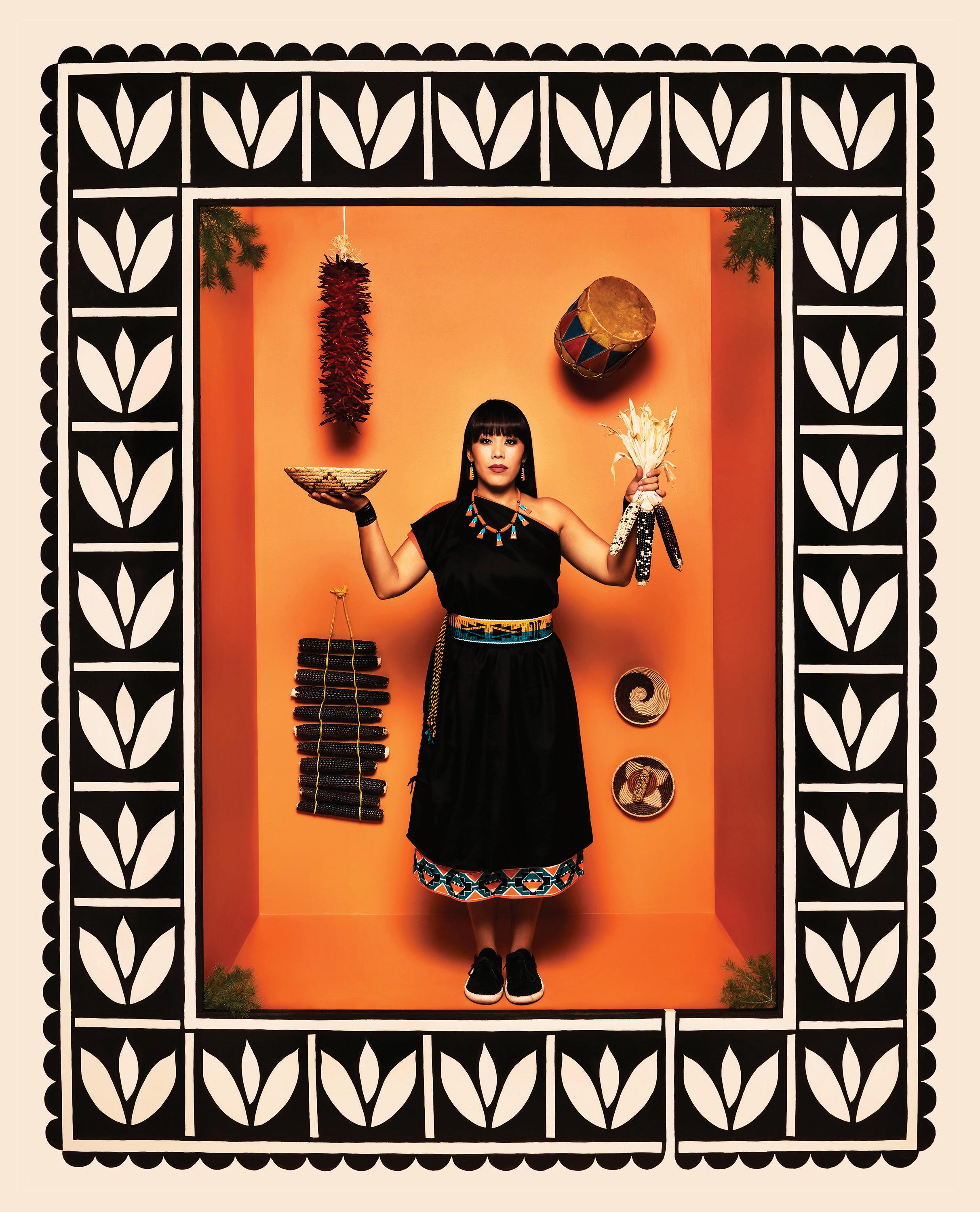

Digital photography was initially developed in 1975 by Steven Sasson, an engineer at Kodak, who used a magnetic cassette tape to create the first self contained digital camera. In 1986, Kodak invented the first digital camera with a megapixel charge coupled device, which turned light into an electronic signal to create a digital image, and in 1991 the DCS-100 was released by Kodak as the first fully digital single lens reflex camera for commercial use. By the mid- to late-1990s, digital photography became widely accessible for public use due to technological advancements and lower costs. Cara Romero created the digital image Julia as a part of her First American Girl series, depicting indigenous women in life-size boxes

to add complexity to narratives around Native women. The resulting photographs represent the individuality and resilience of each woman, rooting each photograph in tradition and the modern world through Romero’s use of items specific to her subjects.

From the delicate, time consuming daguerreotypes of the 1800s to the instantaneous digital pictures of the present, the historical timeline of photography mirrors the larger story of artistic and technological innovation. Every evolution—from silver coated copper plates to wet plate collodion negatives to the

pixel—has led the medium towards accessibility, immediacy, and creative freedom. Despite these large transformations, photography has endured as the same essential act: the capturing of light and the preservation of moments in time. The Wellin Museum’s collection traces this development as both a record of the technological progress and an exploration of the continuous redefining of how photographers see, represent, and remember the world.

Page 8: Diego Rivera, Detroit Industry, West Wall, 1932. Fresco, image (upper register, left side): 101 1/2 × 84 inches (257.8 × 213.4 cm), image (upper register, center panel): 101 1/2 inches × 26 feet 1 1/2 inches (257.8 cm × 7 m 96.3 cm), image (upper register, right side): 101 1/2 × 84 inches (257.8 × 213.4 cm), image (middle register, left side): 26 7/8 inches × 73 inches (68.3 × 185.4 cm), image (middle register, center panel): 52 1/2 inches × 26 feet 1 1/2 inches (133.4 cm × 7 m 96.3 cm), image (middle register, right side): 26 7/8 inches × 73 inches (68.3 × 185.4 cm), image (lower register, left side): 17 feet × 66 1/2 inches (5 m 18.2 cm × 168.9 cm), image (lower register, right side): 17 feet × 67 inches (5 m 18.2 cm × 170.2 cm). Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, MI. Gift of Edsel B. Ford. Public Domain. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Page 10: Mario Moore. Garland of Resilience, 2025. Oil on linen, 53 1/2 × 44 × 2 3/4 in. (135.9 × 111.8 × 7 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Purchase, William G. Roehrick ‘34 Art Acquisition and Preservation Fund. © Mario Moore. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Page 11: Renée Cox, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben, 1998. Diasecmounted dye destruction print, 48 3/4 by 61 3/4 in. (123.8 by 156.8 cm). © Renée Cox. Image courtesy of Renée Cox.

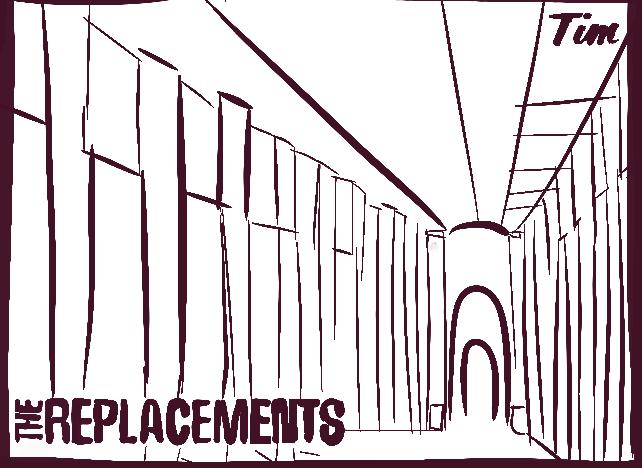

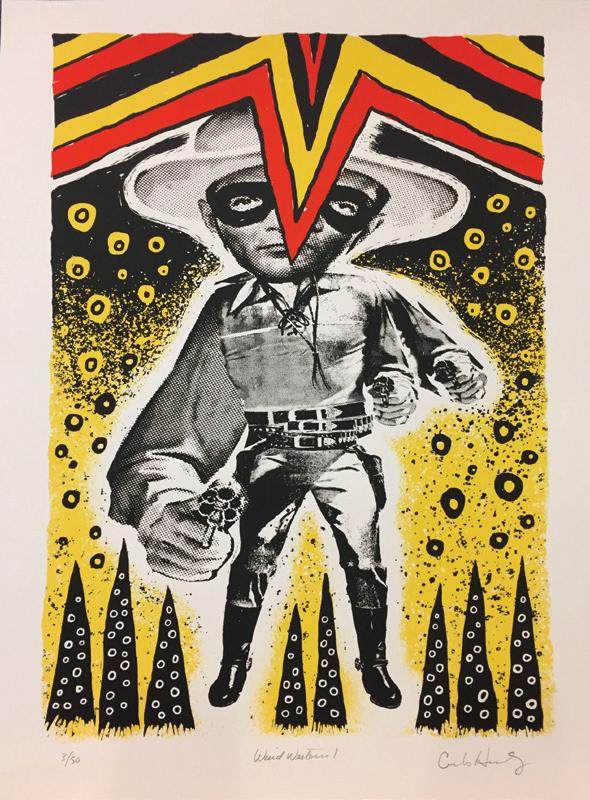

Page 12: Carlos Hernandez. Weird Western 1, 2018. Screen print, 24 1/16 × 18 1/16 in. (61.1 × 45.9 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Purchase, The Wynant J. Williams ‘35 Art Collection Fund. © Carlos Hernandez. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Photo by John Bentham.

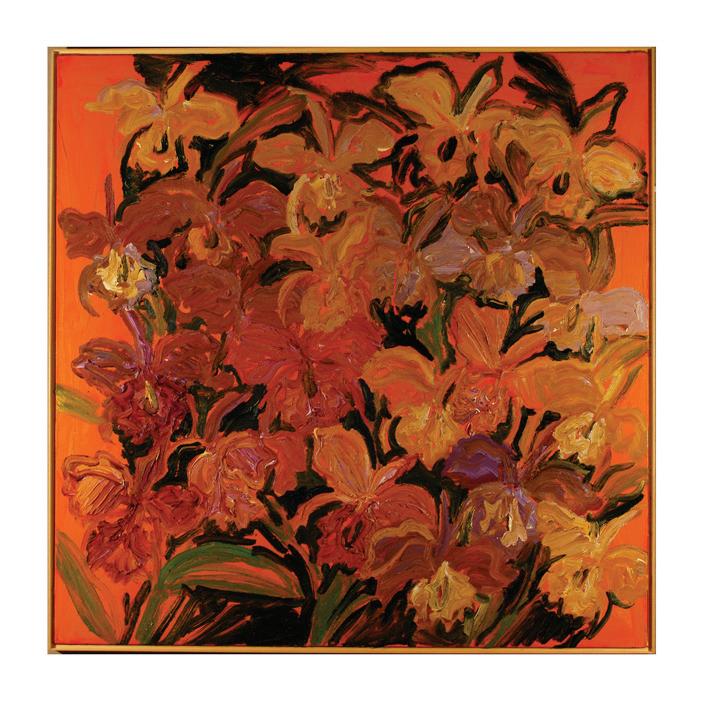

Hunt Slonem. Catelaya, 2002. Oil on canvas, 51 1/8 × 51 1/4 × 2 1/8 in. (129.9 × 130.2 × 5.4 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of Jeffrey Slonim. © Hunt Slonem. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Carl Frederick Gaertner. Land’s End Road, 1948. Oil on canvas, 36 3/4 x 56 1/2 in. (93.3 x 143.5 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of Dr. Stephan J. and Mary Craven, P’99. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

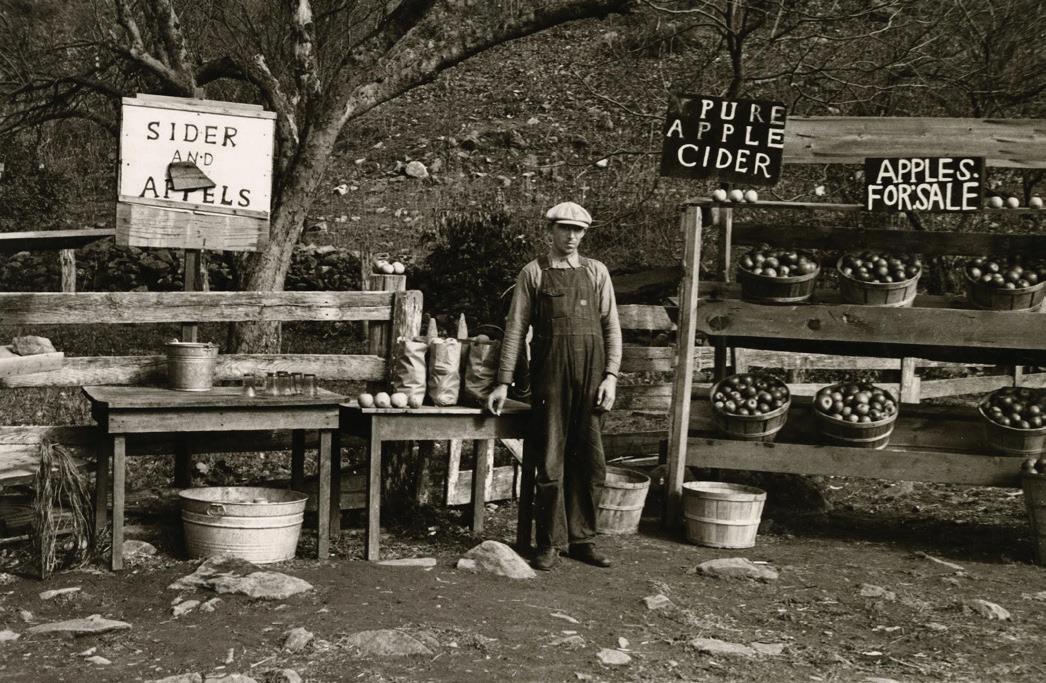

Page 13: Arthur Rothstein. Cider stand, Blue Ridge Mountains, Virginia, 1935 (printed later). Gelatin silver print, 11 in. × 13 7/8 in. (27.9 × 35.2 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of Thomas J. Wilson and Jill M. Garling, P2016. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

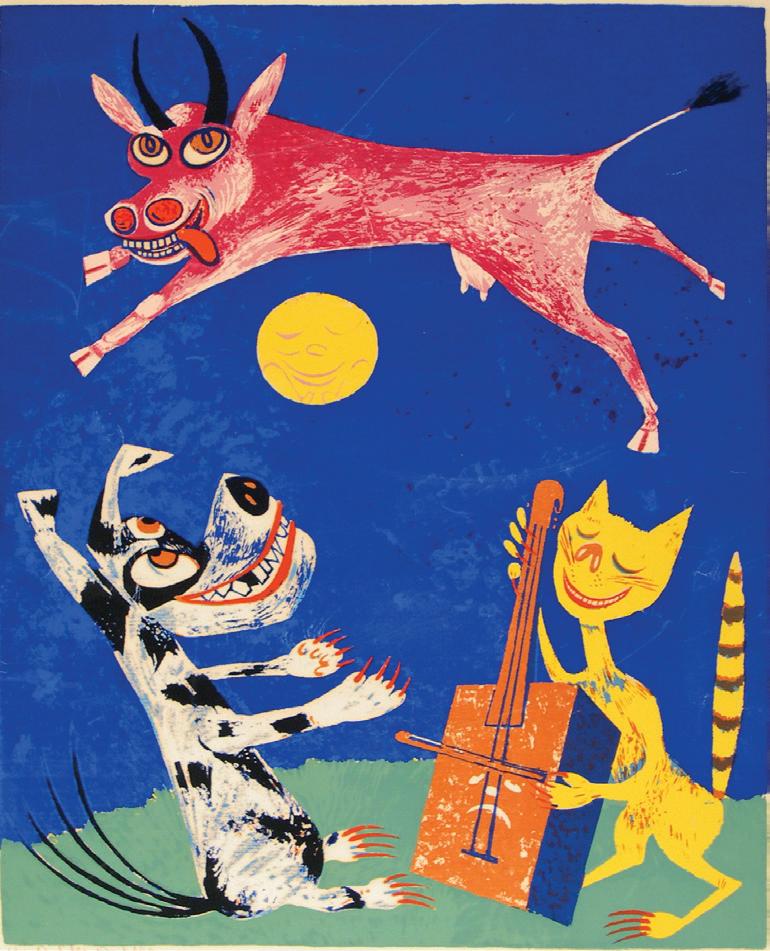

Chet La More. Hi Diddle Diddle, 1941. Color screenprint, 25 1/2 in. × 20 in. (64.8 × 50.8 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of James Taylor Dunn, Class of 1936. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Denise Bellon. Caretakers walking the greyhounds - each “lad” has 6 to 8 animals each and walk about 10 kilometers each time, Le Coudray, France, 1938. Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of Thomas J. Wilson and Jill M. Garling, P2016. © Estate of Denise Bellon. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Page 17: William Helburn. Cheryl Tiegs Hair Tape, 1968. Archival pigment print, 20 × 16 in. (50.8 × 40.6 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of Hardy Helburn, Class of 2001. © The William Helburn Archive. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Page 24: Robert Motherwell. Springtime Dissonance, 1980. Etching and aquatint,

20 1/4 × 27 11/16 in. (51.4 × 70.3 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of Philip W. Abell, Class of 1957. © The Dedalus Foundation / Artist Rights Society (ARS). Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Corita Kent. this beginning of miracles, 1953. Screen print, 16 × 20 in. (40.6 × 50.8 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of Elbert Lenrow, Class of 1923. © Corita Art Center, a project of Immaculate Heart Community / Artist Rights Society (ARS). Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Christoph Schellberg. I Will Drive Slowly, 2017. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 68 7/8 × 56 7/8 × 1 1/4 in. (174.9 × 144.5 × 3.2 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Purchase, William G. Roehrick ‘34 Art Acquisition and Preservation Fund. © Christoph Schellberg. Image courtesy of the Linn Lühn Gallery.

Page 25: Dorothy Shakespear. War Scare, July 1914. Watercolor and graphite, 10 × 14 in. (25.4 × 35.6 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Extended loan from the estate of Omar S. Pound, Class of 1951. © Estate of Dorothy Shakespear Pound. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Photo by John Bentham.

Al H. Qöyawayma. In the Beginning, 1995. Terracotta, 4 3/8 × 6 1/4 × 10 3/16 in. (11.1 × 15.9 × 25.9 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of Juli and Gil Towell, Class of 1950, P1983. © Al H. Qöyawayma. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Photo by John Bentham.

Betty Parsons. House Store, 1977. Acrylic on wood, 18 9/16 × 15 3/16 × 1 1/2 in. (47.1 × 38.6 × 3.8 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of William G. Roehrick, Class of 1934, H1971. © Betty Parsons and William P. Rayner Foundation. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Photo by John Bentham.

Page 26: Danny Lyon. Inmate outside warden’s office, about to be transferred by local authorities, from the series Conversations with the Dead, 1968. Gelatin silver print, 13 7/8 × 10 7/8 in. (35.2 × 27.6 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of Thomas J. Wilson and Jill M. Garling, P2016. © Danny Lyon. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Page 28: Various unknown photographers, American. Photograph album, 18601910. Leather, brass, and paper album containing tintypes, cartes de visite, and gelatin silver print, 5 1/2 × 4 1/2 × 1 1/2 in. (14 × 11.4 × 3.8 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Photo by John Bentham.

Page 29: Unknown artist, Javanese. Batik fragment, 18th-19th century. Cotton, 10 × 9 3/8 in. (25.4 × 23.8 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of the Carnegie Corporation from the Eliza M. and Sarah L. Niblack Collection. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Photo by Mark DiOrio.

Page 30: Painted by Michelangelo and published by Fratelli Alinari Fotografi Editori. Roma - Palazzo Vaticano, Cappella Sistina. Gruppi di Santi e Sante, dettaglio del Giudizio universale, 1875-1900. Albumen print, 9 3/4 × 7 3/8 in. (24.8 × 18.7 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of James Garfinkel, Class of 1980. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Painted by Raphael and published by Fratelli Alinari Fotografi Editori. Roma -

Palazzo Vaticano. Sala della Segnatura, con gli aggreschi di Raffaello, 1875-1900. Albumen print, 7 3/4 × 9 3/4 in. (19.7 × 24.8 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of James Garfinkel, Class of 1980. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY

Page 31: Drawn by Thomas Nast and published by Harper’s Weekly. The Chinese Puzzled; The Evolution of the Americanized Foreigner; and Oh the garland of it, May 15, 1886. Wood engraving on newsprint, 15 3/4 × 11 in. (40 × 27.9 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of Professor Emeritus Jay Williams, Class of 1954. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Page 34: Unknown maker, Portuguese. Floral fragment, c.1765. Block-printed cotton, 9 7/8 × 6 in. (25.1 × 15.2 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of the Carnegie Corporation from the Eliza M. and Sarah L. Niblack Collection. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Photo by Mark DiOrio.

Jeffrey Gibson. I WANNA GIVE YOU DEVOTION, 2019. Digital print, silkscreen, and collage, with gloss varnish, in custom-color frame, 40 1/2 × 36 1/2 × 1 5/8 in. (102.9 × 92.7 × 4.1 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Purchase, William G. Roehrick ‘34 Art Acquisition and Preservation Fund. © Jeffrey Gibson. Image courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Jamea Richmond-Edwards. Devotional for the Divine Mind, 2021. Ink, acrylic, colored pencil, marker, oil pastel, fabric, glitter, glass, rhinestones, jewelry and mixed media assemblage on canvas, 80 × 72 3/8 × 2 5/8 in. (203.2 × 183.8 × 6.7 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Purchase, William G. Roehrick ‘34 Art Acquisition and Preservation Fund. © Jamea Richmond-Edwards. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Photo by John Bentham.

Alison Saar. Congolene Resistance, 2021. Screen print, acrylic spray paint, and gloss varnish on aluminum tin, 18 1/2 in. × 18 1/2 in. × 2 in. (47 × 47 × 5.1 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Purchase, The Wynant J. Williams ‘35 Art Collection Fund. © Alison Saar. Image courtesy of Tandem Press, Madison, WI.

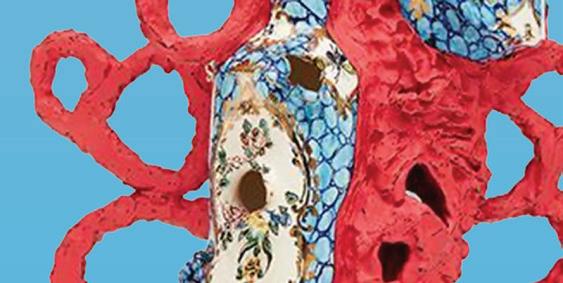

Francesca DiMattio. Sevres II, 2016. Glaze and luster on porcelain and stoneware, enamel, and epoxy, 31 3/4 × 23 1/2 × 10 in. (80.6 × 59.7 × 25.4 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Purchase, William G. Roehrick ‘34 Art Acquisition and Preservation Fund. © Francesca DiMattio. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Photo by John Bentham.

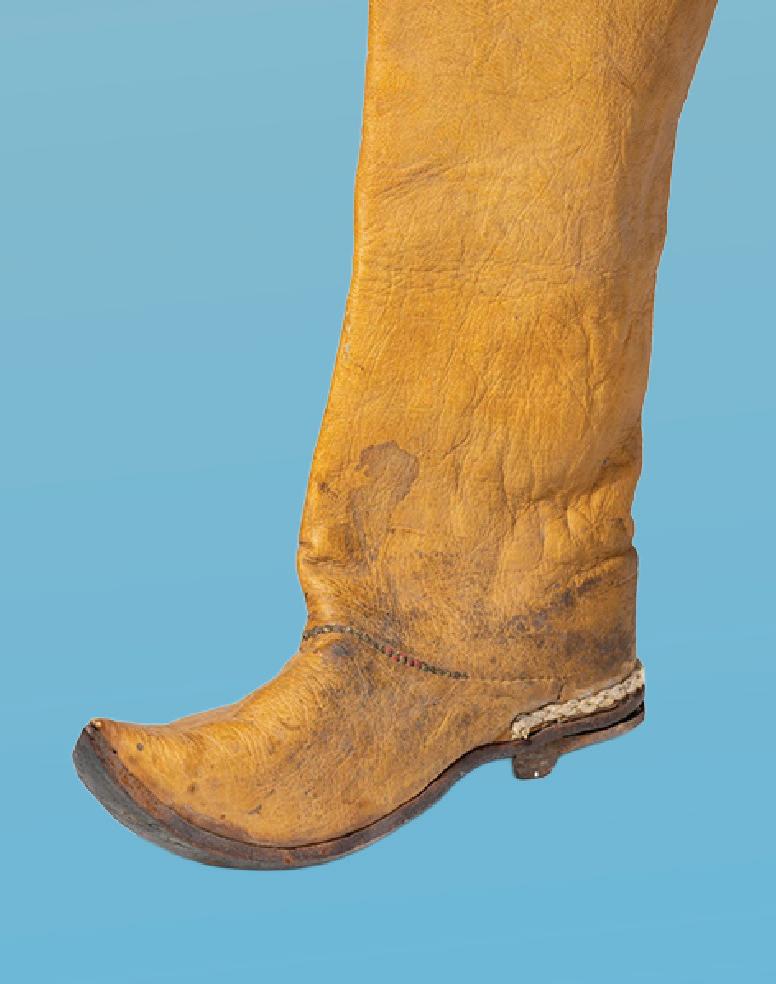

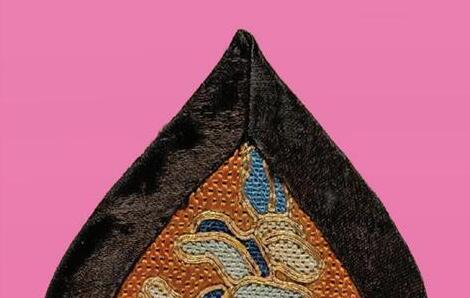

Unknown maker, Turkish. Boot, 19th-20th century. Leather, cotton, thread, iron, blue dye, 11 × 3 1/2 × 13 in. (27.9 × 8.9 × 33 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Transfer from the Hamilton College Anthropology Department. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Photo by Mark DiOrio.

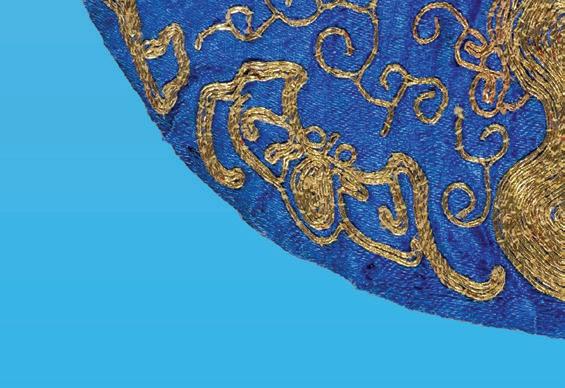

Unknown maker, Chinese. Assorted textile fragments, 19th century. Embroidery and hand woven ribbon, 13 5/8 in. (34.6 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of the Carnegie Corporation from the Eliza M. and Sarah L. Niblack Collection. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Photo by Mark DiOrio.

Page 35: Unknown maker, Chinese. Assorted textile fragments, 19th century. Embroidery and hand woven ribbon, 13 5/8 in. (34.6 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of the Carnegie Corporation from the Eliza M. and Sarah L. Niblack Collection. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Photo by Mark DiOrio.

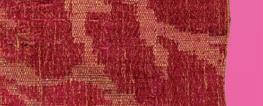

Unknown maker, Spanish or Italian. Brocatelle fragment, 18th century. Silk and linen, 11 1/4 × 7 1/4 in. (28.6 × 18.4 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of the Carnegie Corporation from the Eliza M. and Sarah L. Niblack Collection. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Photo by Mark DiOrio.

Firelei Báez. Amidst the future and present there is a memory table, 2013. Pigmented abaca, cotton, and linen on abaca base sheet with radiograph opaque ink, 39 3/4 × 60 3/8 in. (101 × 153.4 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Purchase, William G. Roehrick ‘34 Art

Acquisition and Preservation Fund. © Firelei Báez. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Photo by John Bentham.

Jamea Richmond-Edwards. 7 Mile Fly Girl, 2018. Pigment print with silkscreen diamond dust and gold foil, 27 7/8 × 23 7/8 × 1 5/8 in. (70.8 × 60.6 × 4.1 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Purchase, The Edward W. Root Class of 1905 Memorial Art Purchase Fund. © Jamea Richmond-Edwards. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Photo by John Bentham.

Unknown maker, Indonesian. Ikat textiles, 20th century. Dyed and woven wool, 45 × 14 1/2 × 1/16 in. (114.3 × 36.8 × 0.2 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Transfer from the Hamilton College Anthropology Department. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Photo by Mark DiOrio.

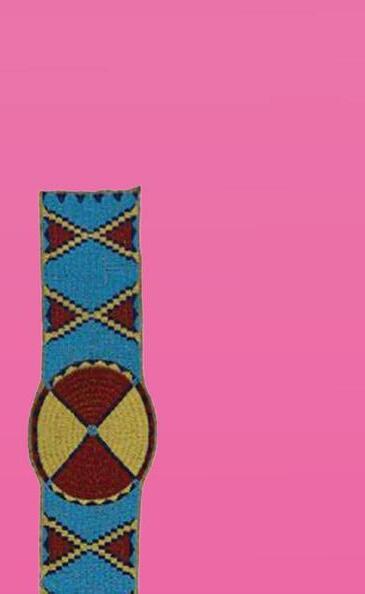

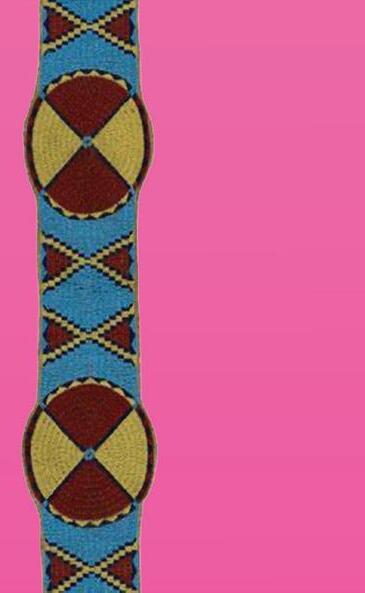

Unknown maker, Native American, Plains. Beaded blanket strip, c.1875. Tanned leather, sinew, and glass beads, 4 3/4 × 56 1/2 × 1/4 in. (12.1 × 143.5 × 0.6 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Transferred from the Knox Hall of Natural History, Hamilton College. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Photo by John Bentham.

Page 36: Published by the American Stereoscopic Company for Quaker Oats. Shopping In the Market, Santiago, Cuba, 1906. Chromolithographs on cardstock, 3 1/2 × 7 in. (8.9 × 17.8 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of Simón de Swaan. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Page 42: Unknown photographer, American. Portrait of a dog, c.1855. Daguerreotype, 2 7/8 × 2 1/2 × 5/8 in. (7.3 × 6.4 × 1.6 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Purchase, The Paul Parker Memorial Fund. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Photo by John Bentham.

Page 43: Photographed by Bisson Frères and printed by Imprimerie Lemercier et Cie for A. Morel et Cie, Paris. Ensemble du Timpan, c.1850. Salted paper print from a collodion negative, 10 1/4 × 14 1/2 in. (26 × 36.8 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of Thomas J. Wilson and Jill M. Garling, P2016. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Charles T. Scowen. Men with elephant, Ceylon, c.1880. Albumen print from a collodion negative, 8 in. × 10 3/4 in. (20.3 × 27.3 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of Thomas J. Wilson and Jill M. Garling, P2016. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Page 44: Jessie Willcox Smith. Gertrude, Shakespeare, before 1922. Gelatin silver print, 6 7/8 × 4 3/8 in. (17.5 × 11.1 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of William Earle Williams, Class of 1973, in memory of William G. Roehrick, Class of 1934, H1971. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Bill Owens. He’s a typical Californian who doesn’t know how to relax, 1971. Chromogenic print, 8 × 10 in. (20.3 × 25.4 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of Thomas J. Wilson and Jill M. Garling, P2016. © Bill Owens. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Page 45: Cara Romero. Julia, 2018. Archival pigment print, 53 5/8 × 43 7/8 in. (136.2 × 111.4 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Purchase, William G. Roehrick ‘34 Art Acquisition and Preservation Fund. © Cara Romero. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

CROSSWORD ANSWERS ACROSS

3. Dragon 6. Collage 7. AfriCOBRA 10. Cartier 12. Fly

Pyramid

Choctaw

Serpent

Prom DOWN 1. Mink 2. Fresco 4. Iceberg

Howard

Coogi

Rivera

Tesem

Detroit 8. Alligator