Hi everyone!

We are so excited to be sharing the 4th edition of Collection magazine with you! Our museum team has grown to six members, which has helped us make this the longest edition to date. This edition is focused on the theme of construction and materiality, drawing inspiration from the Wellin’s 10–year anniversary show, Dialogues Across Disciplines, and Close Quarters, the Class of 2023 senior art thesis show.

Part of our mission as a magazine is to demystify the museum and reduce the fear and intimidation that so many people can feel in art museums. Over the past semester we had the opportunity to interview visiting artists Jamea Richmond-Edwards and Donté K. Hayes, both of whom have works in the Wellin’s collection. These interviews focused on their art-making processes and inspirations.

We wanted to make this truly a community-driven collaborative edition so we have sought out artwork submissions from Hamilton students, faculty, and staff. We also spent time with two senior art majors to learn about their work and process. This collaboration with the Hamilton community has helped expand what we thought possible for Collection magazine.

Putting this issue together was an incredibly rewarding experience and we hope you enjoy!

Hannah, Olivia, Juju, Dani, Sydney, and Holly

Hannah, Olivia, Juju, Dani, Sydney, and Holly

Jamea Richmond-Edwards, a contemporary mixed media artist, draws on her childhood growing up in Detroit, her African American and Native American heritage, and American pop culture to create vibrant and compelling paintings, drawings, and prints. Richmond-Edwards is a Detroit native, where she currently lives and creates art full time. Previously, she worked as an art educator, aiming to bring representation to the classroom. She taught at the Jim Henson Academy for Visual and Performing Arts in Maryland, where she was given the opportunity to inaugurate the school and establish its admission process. Richmond-Edwards notes that teaching was a reciprocal relationship for her, in which she gained inspiration and insights from her brilliant young students. After spending thirteen years in art education, she felt that it was time to step away. For Richmond-Edwards, thirteen is a sacred number, symbolizing good luck and change. This sign led her to step away from teaching to embrace other projects.

In 2020, the Wellin Museum of Art acquired a print of hers, 7 Mile Fly Girl, which received positive feedback from students and faculty alike. The museum subsequently purchased a large-scale painting, Devotional for the Divine Mind, which is featured in the exhibition Dialogues Across Disciplines: Building a Teaching Collection at the Wellin Museum. During her recent visit to Hamilton College as a visiting artist, Richmond-Edwards shared that she loved being back in an academic setting, talking with students and engaging in insightful conversations. While Richmond-Edwards learned from her interactions with our community, we were privileged to learn from her about her studio practices, her inspirations, and what she is looking forward to in her career.

Richmond-Edwards describes her artistic process as an improvisational experience. She begins with collecting her materials, which could consist of found objects, leftover materials from students, or items with familial importance. When looking at her work, it is easy to recognize many of the materials she uses, from glitter to construction paper. Richmond-Edwards describes her art materials as “everything an art teacher would have in her classroom.” When asked about her art making process, Richmond-Edwards shared how she wants to be more transparent about the artmaking process and change the way we see and understand artwork. To her, art making is a spiritual process and consists of the many rituals that come with creating art, like washing brushes and preparing the canvas. In a form of meditation and therapy, “the painting is a prayer” that Jamea participates in as a method of self discovery.

Richmond-Edwards’s artistic process is nonlinear; she doesn’t begin each work with all of the ideas and meanings ironed out. Instead, she begins by drawing or painting the faces of her figures. She then lets her artwork teach her, as she listens to the empty canvas and each face. Richmond-Edwards spoke to us candidly about how she often learns from her own work and how it reveals things to her that she had not intended originally. Richmond-Edwards’s studio could even be called a university as her artistic journey is a series of “investigating ideas” and discovering meaning during and after the completion of a work.

Having the opportunity to meet and interview Richmond-Edwards in person was awe-inspiring and motivating. Her creativity is admirable and her dedication to telling her family’s story and the stories of Black and Indigenous peoples alike is inspiring. As students interested in art and museums, we often become acquainted with an artist’s work long before we become acquainted with the artist themself, which can sometimes create an exclusive focus on the process and materials instead of an appreciation for the artist and their goals. Meeting Richmond-Edwards reminded us that artists are humans too, with stories and ambitions to help their communities and the world around them through art. At Hamilton, Richmond-Edwards made it her mission to interact with as many students as possible by hosting a seminar open to the entire campus, meeting with senior art majors in their studios, offering classes on her artworks in the Wellin’s collection, and even allowing us to interview her for this magazine.

When asked about what’s next on her agenda, Richmond-Edwards stated that her artistic journey is only just beginning. She is currently part of an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum from March 3rd to June 25th, 2023 entitled A Movement in Every Direction: Legacies of the Great Migration. She also shared that she is currently working on launching her clothing line and eating less cookies.

Her wisdom is undeniable and before leaving, she shared a few pieces of advice with students, especially those hoping to be artists someday. “Make work about you because your work is always about you. Don’t detach yourself from your work and take responsibility for your creations. Remember that just because it is in the museum space, that it does not remove the sacredness of your work. Don’t oversaturate yourself with other artists. And learn to be okay with being patient.” For students interested in learning more about Jamea Richmond-Edwards and her art, we highly encourage visiting the Wellin Museum to see her art in person. If you want to stay informed on her current and future endeavors, check out her instagram @JameaRichmondEdwards.

Donté K. Hayes is a research-based artist living in New Jersey, who uses art as a vehicle for exploring the African diaspora as well as his interests in history, science-fiction, and hip-hop culture. He views ceramics as an art form that balances honoring the past with building room for future growth. He graduated from Kennesaw State University in Georgia with a BFA in ceramics and printmaking with a minor in art history, and later received his MFA and MA with honors from the University of Iowa. Before Hayes was a sculptor, he painted and drew. His art was his income, and he worked with hip-hop artists in Atlanta. His life changed drastically, though, after he and his first wife suffered a miscarriage.

“I ended up not just divorced, but homeless,” he said.

Then, in 2008, Hayes’s mom fell ill and he became her caretaker. Looking back on how this time influenced his art, Hayes remarked, “A lot of my work deals with me taking care of my mom. It’s crazy when you have to take care of your mother and you have to clean her feces and stuff like that. Guys, we never feel like we have to do that. I’m coming from that way, like what does it feel like to be a man? And then lose what you thought was going to be your daughter?”

To support himself and his mother, he started working at Michael’s and Sherwin Williams. It was one of his coworkers from Sherwin Williams who encouraged him to go to college for the first time. There he had his first experience working with clay, sparking the career he has now.

While in college and graduate school, Hayes developed his unique artistic process. Before Hayes even touches any clay, he spends months researching. His studies involve interacting with the world, absorbing information through a quasi-osmosis of creativity. Books, conversations, documentaries, podcasts, and music are all sources of knowledge and inspiration for Hayes, providing him with a deep reservoir of ideas to draw upon in his own practice.

When it is time to apply his research, Hayes enters a “trance” where he sculpts for up to sixteen hours consecutively for multiple days at a time. He does not plan what type of form he will make, instead letting intuition take over.

“I don’t ever take a break,” he said. “I don’t go to the bathroom. I’m not hungry when I’m doing work and as soon as it’s over, I am. I’m parched because I get into it, I become one with that form.”

Once the object is complete, Hayes makes a “field guide,” reflecting on the influences that emerged in the piece and sketching the finished sculpture. He likens himself to an archaeologist, learning about the object and form he has found from it directly instead of imposing a meaning onto it. In this way, he sees his pieces as “future artifacts.”

Hayes’s work appears atemporal. His pieces simultaneously look ancient, modern, and futuristic, giving them a universality across time. Hayes emphasizes the connection between us and people of the past.

“They were thinking about the same things that all human beings have always thought of,” he explained. “Like, why am I here? Am I doing something important?”The atemporal nature of his work also expresses the merging of the past, present, and future — a state that Hayes asserts we all live in.

Hayes’s primary material, clay, contributes to the sense of time periods colliding. He stated, “This medium has been a part of humanity all our lives. We started with clay from the ground. That’s a part of us.” The clay finds its way underneath fingernails and, as Hayes remarked, “You become part of that material… That’s very important to my work, the idea of being one with something.”

In its initial state, the clay is brown, but once it is fired to 2,167 degrees fahrenheit the clay becomes black, which is how Hayes wants it to remain. “I feel like if I glazed the work, then I’m putting a mask on it. I want my work to always feel that it’s unmasked,” added Hayes. Another part of Hayes’s practice is flipping his vessels upside down, introducing the theme of reversals into his work.

Through his knowledge of clay and intuitive sculpting style, Hayes has experimented with unique forms. As part of the Wellin Museum’s Creative Commission series, he undertook a two-week residency at the Wellin Museum, creating six pieces inspired by Native American baskets in the museum’s collection. The residency was also supported by Professor Rebecca Murtaugh, the art department, and KTSA. Although made of clay, the works appear to be woven. He achieved this by using a Ghanaian technique involving pinching coils of clay to create his vessel and then using a needle tool to make the individual marks that create a woven effect.

Baskets have a symbolic resonance for Hayes. Weaving, the creation of baskets, speaks to how we “weave in and out of worlds.” For both the Chickasaw and Oneida people, baskets represent “the welcoming of a new home.”

Hayes connected with this interpretation on a personal level because of his own Chickasaw heritage and the fact that he and his wife were in the process of building a new home during his time at the Wellin. Furthermore, he expressed that “we put things that will nurture other people into baskets,” such as food and blankets.

The symbolism of non-Western cultures, like Native American and African cultures, are crucial in Hayes’s work. Hayes never learned anything about the history of Africa in school, only hearing snippets here and there of Egypt because of its ties to the Western world. Due to lack of exposure, Hayes became motivated to use his art as a vehicle for exploring African art and obtaining knowledge that is regarded as insignificant in everyday schooling. Even so, Hayes often finds his work in Western spaces, which causes tension to emerge. In Hayes’s eyes, however, the tension proves powerful as it allows conversations and learning to take place that would not otherwise.

He said, “In Western culture, what’s the first thing that we think when we hear the word white? We think it means purity. So when someone sees my work, that’s the first thing they think. But I’m thinking about it in a different way. In other cultures, white is the color of death and black is the sign of intelligence and enlightenment.”

Although cultural symbolism is important in his art, Hayes perceives his work as something more significant than the accumulation of his identities.

“It’s okay to be Black. Just like it’s okay to be white. That has nothing to do with the work. What has something to do with the work is like we all go through things….My work speaks to humanity,” remarked Hayes.

When Hayes described the Black body, he is not talking about the outer body, but rather the inner body. He described, “I am not talking something superficial and I’m not talking about outer, I’m talking about inner because really the architecture we are is inside. We have control of all of our ways we think, and the ways we talk, the ways we say things, the ways we think about other people, right?”

Due to his strong beliefs in authenticity, Hayes retains a sense of autonomy over his work. He said, “Sometimes, someone asks me to do a show, I say, no thank you. I don’t want a show there.” Hayes’s mission is to live authentically and to convey to other people that they, too, can be open. He hopes that people can learn to live without the masks we feel compelled to put on. Through pouring his vulnerabilities, knowledge, and experiences into his artwork, he carries out his mission.

To see his artwork, visit dontekhayes.com or visit the Wellin Museum. Protector (2022) will be on view in the exhibition Dialogues Across Disciplines until May 20, 2023.

The process of creating art is not eminently apparent when viewing a finished work, as the many steps taken and layers within a piece coalesce into something greater than its combined parts. Sometimes, though, we can get a glimpse of what happens during production.

The piece Study for La fileuse chevrière auvergnate (The Spinner, Goatherd of the Auvergne) by Jean-François Millet is a preliminary sketch made before a painting, providing us a look into the artist’s process. The finished painting currently resides in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, France.

Millet was a founder of the Realist movement and a participant in the Naturalist movement. Together with Théodore Rousseau and Charles-François Daubigny, he formed the Barbizon School. He was atypical amongst this group, though, as he was more focused on portraying countryside life than the vacant landscapes his peers painted. His depiction of peasants, laborers, and ordinary people was seen as scandalous because it broke from established artistic and academic traditions regarding the subjects of paintings. Traditionally, subjects were mythological, historical, rich, or famous. Thus, Millet’s quaint and idyllic countryside scenes became politically charged.

When Millet made this sketch, he was visiting Auvergne and Allier with his wife. The thermal waters at Vichy, which were said to have healing properties, were the primary reason for their trip. Millet, however, found the trip formative in his artistic endeavors. He was inspired by the local scenery and drew a series of sketches, including the one in the Wellin’s collection. Millet was particularly struck by the peasant folk of the area, who seemed to possess a different aura than those from his area.

He wrote to the writer Alfred Sensier, “the inhabitants of the countryside are rural in quite a different manner than those of Barbizon… In general, the women’s faces indicate quite the opposite of meanness.”

Millet portrayed this characterization of the country folk in his depiction of the goatherd. Her facial features are gentle and the clouds around her in the finished painting appear almost like a halo, making her appear kind and sweet.

The purpose of the sketch was to help Millet transfer the image to a larger canvas for painting. The grid system overlaying the drawing and the contour lines used to make the figure would make it easier for him to scale the image correctly.

Millet’s sketch illustrates the planning that goes into a piece of art. The act of creation, from the moment of inspiration to the final brushstroke, is an intensive endeavor, requiring diligence as well as imagination.

As a part of the Wellin’s collection, Millet’s sketch stands out amongst our many finished pieces. It is a unique opportunity to get a glimpse behind the curtains, witnessing a moment in the process of creation that underlies all artworks.

Gouache

17in x 22in

2022

“The fish market is a central hub of activity in my dad’s hometown near the sea. This painting captures one of my favorite scenes from my trip to China in 2019; My mom and my uncle at the fish market sifting through shrimp.”

The Trans Experience, 2023

Mixed media on canvas

26in x 38in

“The Trans Experience is about the weight and confusion that come along with navigating transition period. I used art as a theraputic process to explore my identity and existence and hope that the work contributes to increasing trans representation. I also hope it makes people feel they are not alone, think about the struggle that trans people face, and engage with spirituality, creativity, consciousness, and presence.”

Benjamin Zhao, Class of 2026 Fish Market, Dani Bernstein, Class of 2024Sophie Christensen, Class of 2023

Sacré Cœur Geometry, 2022

Photography

5in x 7in

“The Sacré Cœur is such a visually pleasing building. I’ve taken countless photos of it, but this one is my favorite. It’s carvings are so intricate, and I love the Middle Eastern-influenced architectural style.”

Michael Kealy, Wellin Lead Safety Officer

Michael Kealy, Wellin Lead Safety Officer

Nature’s Irony, 2023

Digital Photo

5in x 7in

“I watched the oak leaf fall from the tree, finally free from the branch. It landed directly in a crack in the terrace and it was stuck again.”

Skater, 2013

Paper and thread

8in x 10in

“I started making collage in 2013 after searching for a creative outlet. I am fascinated by color, motion, line and texture and work to incorporate these in my work.”

Vige Barrie, Senior Director of Media RelationsRoot Glen Slope, 2021

Watercolor on Yupo

20in x 26in

“I love walking through the Root Glen in all seasons and the verticals on the slope across from the creek always catches my attention as I walk down into the glen.”

What’s the title of your piece?

FullResImage.JPEG

Why did you choose this?

Because when you download a picture it always gives you that name and it’s kind of funny. It’s probably going to be the final title.

What inspired you to create this work?

In the other art classes here at Hamilton, there wasn’t really space for me to use the materials I wanted to and be a nerd. I like collecting things that would be interesting to make art with: packaging, CDs, DVDs. I appreciate the work that goes into product design as much as it is consumerism, there is an art to it.

Tell us about your process from start to finish, in the simplest way possible.

For years, I have collected interesting bits of products and packaging, things from newspapers and thrift stores to use in my art. I also had this canvas which I restretched and gessoed. I took some mod podge and glued stuff on and kept adding layers. I also added gold leaves in the shape of a dragon, glitter, resin, and I’m probably going to add more glitter.

What are some obstacles you have encountered during this process?

I think the process I’m doing is very non-traditional and it’s very different from a lot of the work that some of the professors gear their classes toward or encourage, so sometimes their advice is not always the most specific to what I’m trying to do. Not to say that all the professors weren’t helpful, I just feel like I had to figure a lot out myself.

Tell us about your studio space & how you prepare it for your artmaking process.

I put a bunch of stuff up on my walls, I really like maximalism, like in my room there are just so many posters on my walls, and I just like being surrounded by images, so I printed out a bunch of stuff…other art from traditional art in a museum and things from the internet and pop culture that inspire me.

What is your favorite part of the process?

The end results, and being very satisfied with making a cool object that I just couldn’t foresee. You have no idea what it’s gonna look like in the end, it’s a cool process.

What is your least favorite material to work with?

I did too much painting and I got tired of doing lots of little details, it takes forever. I really don’t like plaster, it can be cool, but it makes my hands dry and it cracks and crumbles when it’s not supposed to.

What is something people wouldn’t know about you or your work just by looking at it?

The amount of work that goes into it, I feel like with all art there is so much invisible labor. I deliberated where to place all the little bits of packaging, how to arrange things, picking the right color glitter. Collecting the materials takes a while as well. Someone might not guess that I’ve done a lot of traditional painting and photography and I like photography a lot. It’s not very apparent in this work because this is very sculptural, but I wanted to try something new for my thesis.

What kind of materials do you use and why?

Anything that I think looks interesting, I use a lot of garbage, things that are not necessarily seen as valuable, but I don’t care because I like the aesthetic. I look at something and I imagine it in a different way. So like pony beads are for kids and cheap, but they are so brightly colored and can be sparkly, or pop tabs, they are sort of like little collecting tokens.

Who is an artist you are interested in right now?

The guy who took pictures for I Spy [Walter Wick], I really like his photographs they are very maximalist and they’re fun and playful, which I try to emphasize in my work, just a lot of details and a lot of things going on.

How has your experience being a student at Hamilton influenced your work?

The other art majors are really cool, there is a lot of amazing work. I got to see everyone’s style grow and become more them. Taking classes together in years prior, I can follow how this person’s style developed. And also obviously my friends and stuff have been supportive and great.

What do you want others to take away from your work?

An appreciation of things that are not necessarily valuable… This work is very much our generation so someone might remember Lisa Frank stickers, playing with toys, the packaging. Maybe a sense of nostalgia, also maybe they can see things in a new way.

What’s the worst thing somebody has said about your art?

That is so funny because it’s a professor. Someone telling you with a straight face that you don’t bring anything new to the table is like a matter of fact. Like you can’t refute that, even if it’s not true. How do you be like ‘no it is original can’t you tell?’ I feel like my work is very me and it’s very original. So that sucked.

How has your art grown over the last four years?

With taking a lot of classes I have significantly improved my technical skills. I have also become more comfortable being as me as possible. Freshman year me probably wouldn’t have thought that I could put dragons on things. Now I can be a nerd and say ‘yeah I read manga and it’s good and I watch fun movies.’

What do you want to do after graduation?

I think it would be really awesome to make money by being an artist, I hope that can happen. I think, at least right now, the plan is to be a photographer because I can see that path more clearly.

What’s the title of your piece?

(Non)Rigid Motion I

What are you thinking about with this piece?

I want this to be subtle … it is kind of a reflection of its environment and the light and lighting conditions around it. I want it to be reflective and subtle.

What inspired you to create this work?

I’ve been really interested in creating spatial experiences for people, but this particular piece is going to be in the museum so we do not have that amount of space for creating immersive experiences like my previous works in KTSA and CJ. Those are really site-specific. I’ve been playing with the transformation between shapes and using acrylic sheets and monofilament. This piece is an exploration of material, it adds in a harmonic feeling because it is a hanging piece so it will shift with the movements around it.

What is your favorite part of this process?

Sketching can be frustrating but also fun because you are just drawing whatever is in your mind. It is also fun making models to see the actual thing. I also listen to podcasts while working; it’s fun!

Tell us about your studio space & how you prepare it for your artmaking process.

I try to keep it as clean as possible so I can focus on each part that I am working on.

What kind of materials do you use?

I use acrylic sheets which are recycled from the dividers used during the pandemic. Those materials are stored on a truck somewhere on campus and I sorted and polished them to use in my work. The monofilament lines you can buy online, its fishing line so its approachable, cheap and transparent so it can play with light.

What is something people wouldn’t know about you or your work just by looking at it?

I am not really picky about the details in the installation, but I do love textures and more organic feelings like what other people are doing with their artwork. For these pieces I am not showing that side of me.

Who is an artist you are interested in right now?

Naum Gabo because he was dealing with similar materials and a lot of things he used I am playing with. I was so shocked to see an artist doing something that I was already thinking of and doing it better, I had to shift it a little bit. He is the artist that is most related to what I am doing now.

Tell us about your process from start to finish, in the simplest way possible.

I have something in my mind, I sketch it out, I make some small models and then I polish my materials and I put them together.

How has your art grown over the last four years?

When I started off, I took a design class with Professor Muirhead and he really got me into the art major, but at that time I wasn’t so sure because I was frustrated by what I was making. My work takes a lot of time and I guess I was frustrated making art because I felt like I needed to stay up late. But now the way I work is totally different, I go to my studio in the morning…So I guess it was a working habit change and I get to enjoy the process more.

How has your experience being a student at Hamilton influenced your work?

If I wasn’t a student at Hamilton I wouldn’t be majoring in art at all. The pandemic played a part in it because during my sophomore year I went back to China to take online courses and I didn’t get to take any art classes. But from my experiences during my freshman year art classes, design and ceramics with Rebecca [Murtaugh], I found that it was a good shift from my other academic work. The best way to take art classes is to become an art major.

What do you want others to take away from your work?

A feeling that they have never seen something like this before. I hope they can see what I am seeing or thinking about this abstract concept.

What’s the worst thing somebody has said about your art?

I was told that I do not have my own philosophy in art making and that I don’t have an emotion, political statement, or a strong view, and that really caught me because I had to think about it and I thought maybe I didn’t and that I just make pieces that are in my mind.

Favorite art class you’ve taken?

My junior seminar helped me find my voice as an artist. Funwise, right now I am taking printmaking which I think is really interesting because you get to draw and to carve and it is kind of like sculpture but you can draw in it.

What do you want to do after graduation?

I want to travel a little bit, go home, see my parents and my dogs and just relax a bit because Hamilton has a really fast paced calendar. I just want to enjoy graduation. I will also be pursuing a Master of Architecture degree at Harvard Graduate School of Design.

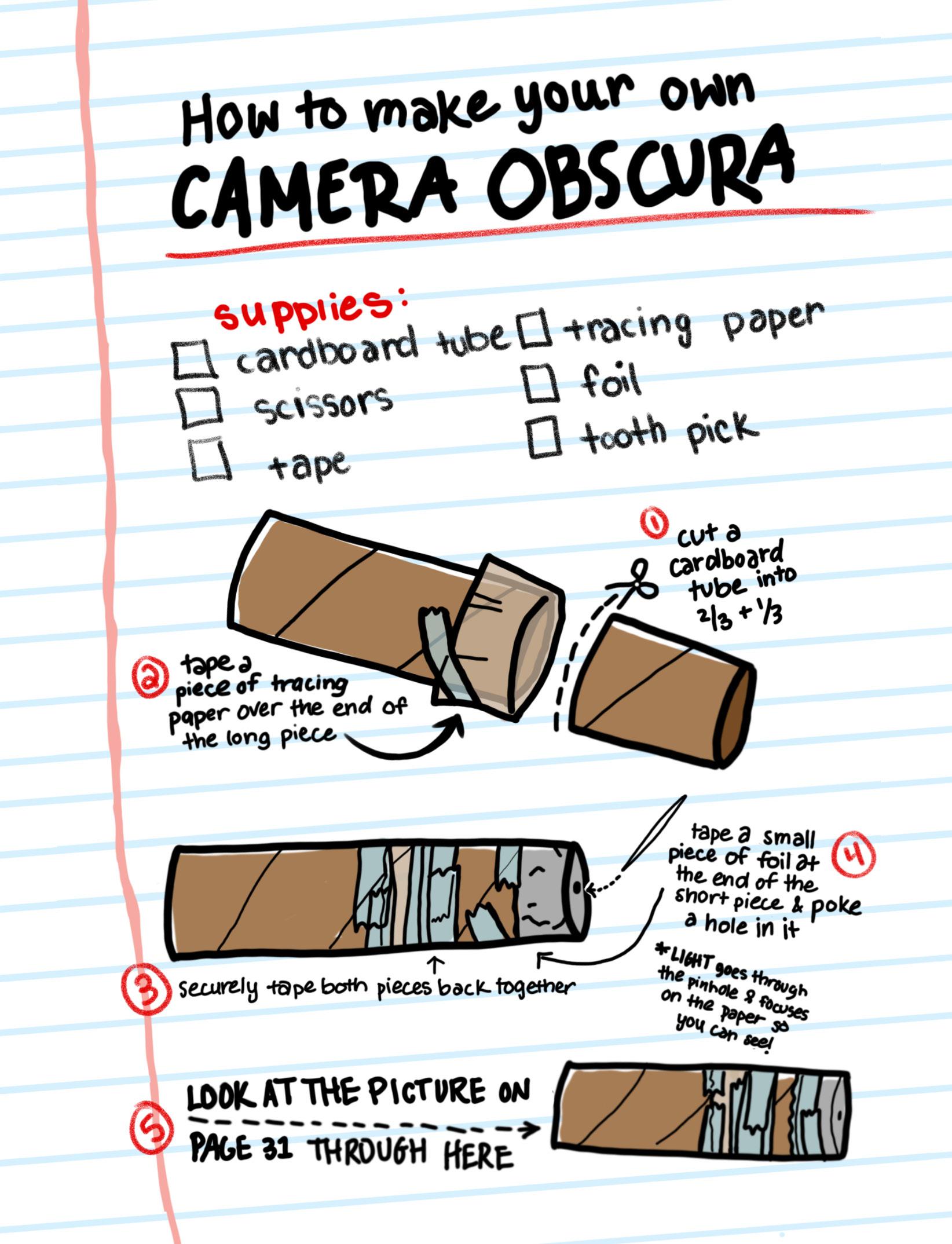

The camera obscura, derived from the Latin phrase meaning “dark chamber,” consists of a small hole piercing a wall in a darkened room. Light reflected by objects in the natural world filters through the hole, projecting an inverted image onto a blank, opposing surface. Scientists first used the camera obscura to study eclipses, but artists later adopted the technology to paint natural landscapes more realistically. As the Venetian nobleman Daniele Barbaro in 1568 described, “There on the paper you will see the whole view as it really is, with its distances, its colors and shadows and motion, the clouds, the water twinkling, the birds flying. By holding the paper steady, you can trace the whole perspective with a pen.”

Although the camera obscura dates back as far as 400 BCE, it is still used today by contemporary artists to produce engaging artworks. One such artist includes Abelardo Morell, who was born in Havana, Cuba in 1948 and immigrated to the United States with his parents in 1962. Morell achieved a Bachelor of Arts from Bowdoin College in 1977, a Master of Fine Arts from Yale University School of Art in 1981, and an honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts from Bowdoin in 1997.

With an extensive education in the arts, Morell began transforming rooms all around the world into camera obscuras. He photographed the images produced by a camera obscura through large-scale formats, depicting the relationship between the interior and exterior and building a name for himself. As Morell writes, “over time, this project has taken me from my living room to all sorts of interiors around the world. One of the satisfactions I get from making this imagery comes from my seeing the weird and yet natural marriage of the inside and outside.”

An example of his prolific series, Camera Obscura includes “Camera Obscura – Late Afternoon View of the East Side of Midtown Manhattan,” an archival inkjet print produced in 2014 that resides in the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art in Clinton, New York. In this artwork, Morell uses a camera obscura to project an image of the New York City skyline onto a blank wall, which he then photographs using a digital camera. Much of his inspiration for this piece draws from his playful curiosity about the world around him. As Morell remarks, “the pictures I made around the house when I first became a father have influenced much of the work that I do today from looking at a book with the curiosity of a child to turning ordinary rooms into giant cameras.”

Morell’s contemporary work, which revitalizes the camera obscura, offers a glimpse into how the history of art continues to influence artists and their work today.

K-12 Programs & Educator Events

The Spring of 2023 was an extremely busy time of year as the Wellin welcomed over 200 students from various local schools in Oneida County. We hosted 8 programs for both students and teachers that aimed at fostering the relationship between the Wellin and the local community. These programs encouraged students to interact with artwork through art activities and discussions. For the educators, their events focused on developing the way in which the museum can best serve an educational audience, not just at Hamilton College, but beyond.

Open Studios

Wellin Open Studio events serve to engage Hamilton students in the art-making process and help them become comfortable within an museum environment. Since they are student-led, many of these events are geared specifically toward the student population and are incredibly popular.

May 4 | Close Quarters: 2023 Senior Exhibition opens

May 13 | Wellin Kids: Fantasy Maps

May 17 | Senior Soiree

May 20 | Close Quarters: 2023 Senior Exhibition closes

September 9 | Rhona Bitner: Resound opens