Basil Brown ’24, a friend and former Hamilton student, took his life a few weeks ago. We would like to dedicate this edition of Collection magazine to Basil. Basil worked as a docent at the Wellin Museum, sharing in that time his creativity, love, and intelligence. On page thirty-four, we’ve put together the many beautiful ways in which you, the Hamilton community, are remembering and honoring Basil. Thank you for your meaningful contributions.

This semester, we’ve worked to make something that wholly represents its team: something creative and colorful—a collection of shapes, patterns, words, and art. We hope that in this edition, you get to discover not only the Wellin Museum, but also the people who shape it.

Our very first magazine, Collection, no. 1, began when Marjorie, who has advised and guided us throughout this process for the last few years, reached out to the docents asking for a Wellin Newsletter team. Hearing of this opportunity, we decided we wanted to work as a team, making something more than just a newsletter—we wanted to develop a magazine. With this publication, we hoped to connect the Hamilton community to the Wellin Museum that we knew and loved. We aimed to shed light on all of the wonderful people, projects, and events created and supported by the Wellin. Throughout the years, Collection has evolved into a publication that encourages each one of us to be creative, pushing and supporting as we explore different designs, writing styles, and ways of thinking. We’ve practiced working in a group in various ways, from near and far, learning to inspire and vitalize each other’s ideas to produce something meaningful.

In this edition of Collection, we explored history, space, and camp æsthetics alongside exhibiting artist René Treviño, put docents and their all-black outfits in the spotlight, and learned about the precise planning that goes into producing the Wellin’s publications. With our Visual Mixtape, we once again combined our love for music with our interest in the Wellin collection, hoping to provide an experience that surpasses just the visual. This magazine is a culmination of our time working at the Wellin through exhibitions, including Yashua Klos: OUR LABOUR, Dialogues Across Disciplines, and Rhona Bitner: Resound, as well as creative events, including Art Yoga, Wellin Kids, art walks, and concerts. This edition explores not only this semester’s happenings, but the impact the Wellin has had on students throughout the past four years and beyond.

We’d like to thank Marjorie Hurley for her consistent support, dedication, and kindness. not exist without you. We’d also like to thank Tracy Adler, Alexander Jarman, Liz Shannon, and Laura Laubenthal, for their generosity toward our team and all of their meaningful contributions throughout the years.

1

2

3

4

By Sae GleBa

By Sae GleBa

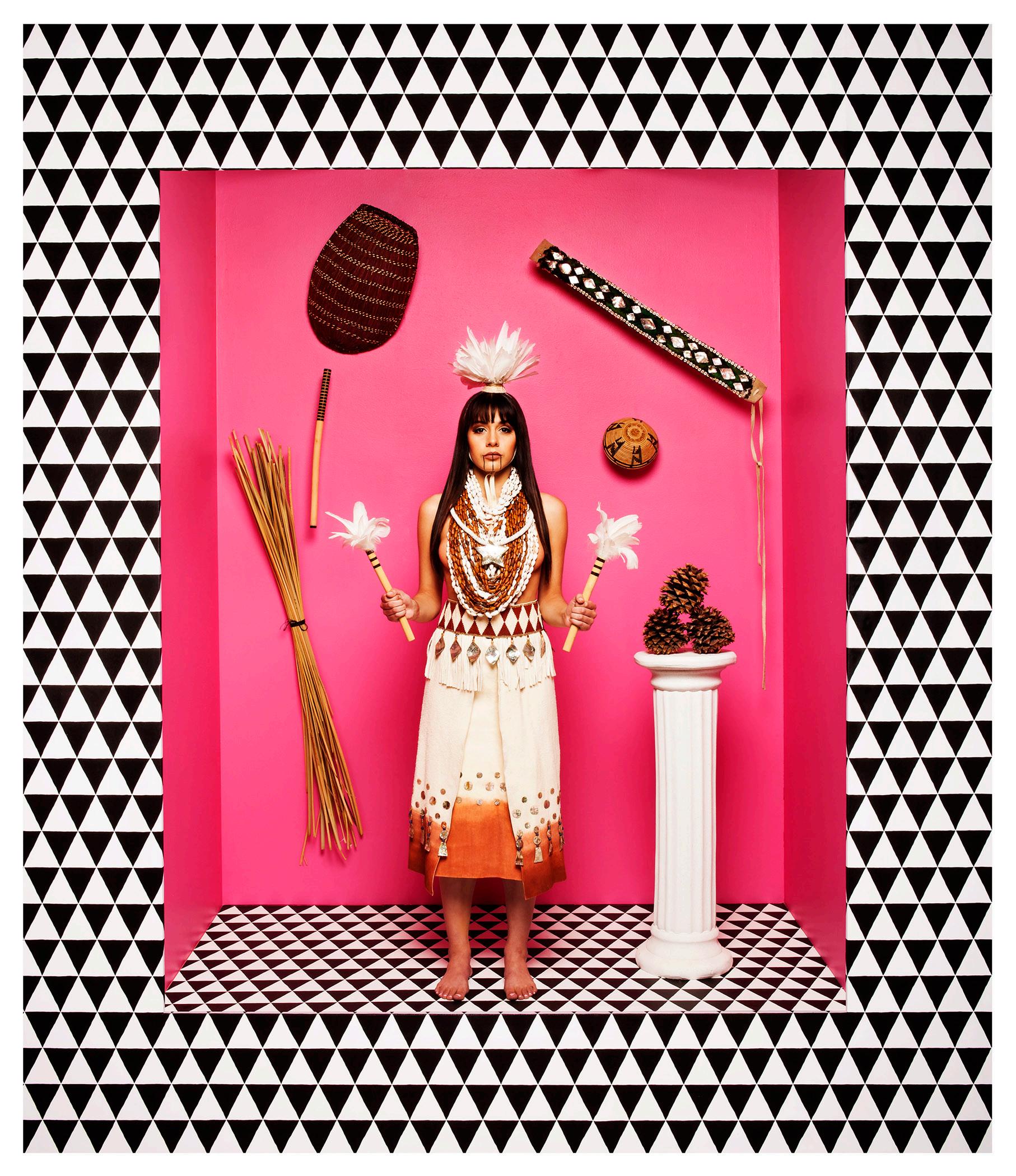

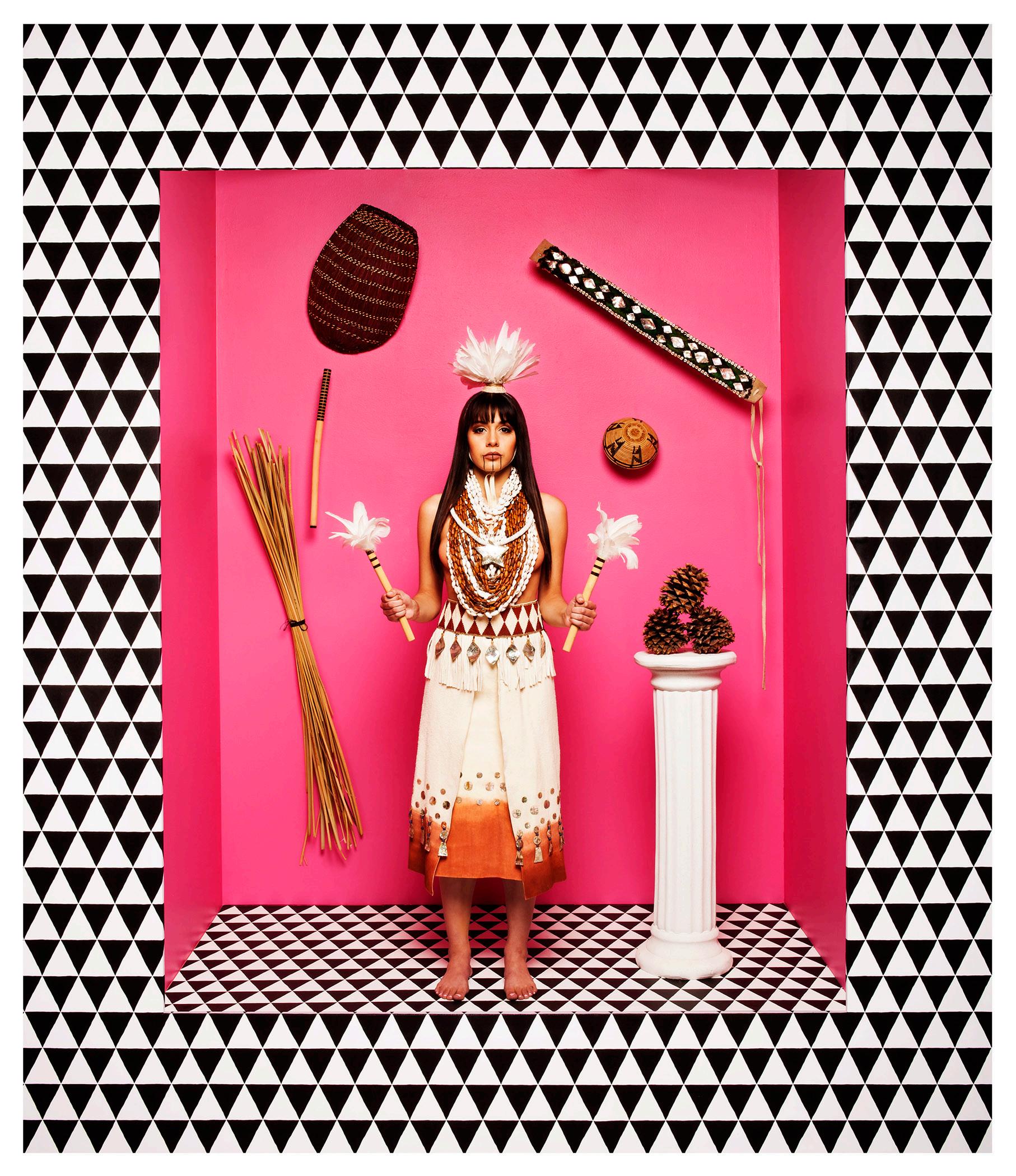

Cara Romero has spent her nearly 30 year career as a contemporary fine art photographer crafting her unique narrative storytelling style as told through photography. Raised between the Chemehuevi Indian Reservation and the urban sprawl of Houston, Texas, the disparate worlds of her early childhood deeply influenced Romero’s identity, shaped by a blend of Indigenous and nonIndigenous cultural memory, collective history, and lived experiences. In Romero’s early days, she was a trained basket weaver, an art form with deep historic and cultural ties to the Chemehuevi peoples. In many ways, Romero’s photography mirrors the intricate and detailed work of weaving – intertwining stories and heritage as willow and devil’s claw, plants commonly used for traditional basket weaving, would be woven.

Romero’s baskets and her photography share another commonality—being both decorative and functional. Romero studied cultural anthropology at the University of Houston, and was disillusioned by the treatment of Indigenous Americans as a “bygone” vestige of the past. Romero was inspired to create images that countered the prominent cultural narratives she saw surrounding Indigenous Americans—images made in black and white with serious, unsmiling faces, donning traditional garb. She saw these as static, archaic representations of her modernized, dynamic community. Romero recognized the inherent power

in photography and the power of art and imagery to counterbalance the words of anthropologists and academics, a realization which led her to study film, digital, fine art, and commercial photography.

Romero’s images are, at their core, stories. Stories told by the woman behind the camera and acted out by the subjects in front of the camera. Romero, as a Native woman, takes on the role of a storyteller, staging painterly compositions enhanced by deep color, using contemporary photography techniques to depict the modernity of Native peoples while illuminating Indigenous worldviews and cultural heritage, imbued with a sense of supernaturalism and theatricality.

Naomi is a part of a series titled First American Girls, a play on the iconic American Girl Doll brand. Romero wanted to create dolls that reflect the culture, beauty, and diversity of Indigenous life in America, seeking to go beyond the misrepresentative, “pan-Indian” look she saw portrayed in children’s toys and dolls. Romero creates images that celebrate resistance and empowerment, applying her attention to detail to craft intricate scenes highlighting regalia and traditional items. Romero photographed multiple women within constructed “doll boxes,” photographing them clothed in diverse regalia and surrounded by objects important to their cultural heritage.

Naomi is a photograph of Naomi Whitehorse, daughter of celebrated regalia and traditional arts maker Leah Mata Fragua, who are members of the Northern Chumash people of California. Whitehorse, Fragua, and Romero worked together to create a photograph that expresses their contemporary love of “California Pop” and their desire to make visible the traditional arts and Indigenous people of California, all within the same frame. Naomi is a celebration of tradition and resilience, a reminder to the viewer of the existence of the contemporary alongside the traditional amongst the Northern Chumash people of the Northern Chumash people, who continue to create traditional art and regalia.

StaB of Guilt

fillinG the SpaCe

By hannah Dillon anD Sae GleBa

6

Wrhinestone sparkle, fantastical figures and imaginative forms. A sharp departure from the dreary and gray winter, René Treviño: Stab of Guilt offers a respite and welcomes you in, all while bringing “a little Las Vegas to Clinton.” After René led a whirlwind week of class visits and public programming, we spoke with him about his experience at Hamilton and his reflections on collaborating with the Wellin. Our conversation allowed our team to gain a better understanding of Treviño’s work and process, all while learning more about him.

the role guilt plays in our lives, both collectively and individually. During a phone conversation

alking into René Treviño: Stab of Guilt brings you into a whole new world. It is a world full of rich and bright color, metallic sheen and with his mother who lives in his home state of Texas (Treviño now lives and works in Baltimore), she chided him that she would probably only see him twenty more times before she died. At that moment, Treviño was struck by an immediate, palpable stab of guilt. “I think about how powerful the emotion of guilt is,” Treviño shared. “Guilt is something that should be used, because we all have it, to make better choices for the future.” Guilt thematically permeates much of the meaning behind his work, encompassing Catholic guilt, familial guilt, and historical guilt. Treviño grappled with thinking about his first solo show at a museum. “This is my first museum exhibition, so I am also thinking about museums, and how museums should have some guilt… they have to think about where their collections came from, who they’re serving, and whose work they are showing.”

For many coming to visit René Treviño: Stab of Guilt, there is a memorable moment of impact when first viewing the gallery space. Dominating the entrance is a large stage, adorned with a gold shimmer wall, dotted with footlights illuminating three large robes, each richly decorated with hundreds of intricately beaded patches, hanging tassels, and layered feathering. It’s a powerful space to walk into, energized and electrified by color and texture. The influence of camp, an aesthetic sensibility codified by exaggeration and artifice, is palpable throughout the exhibition, from the luster of the works on leather to the rhinestone adornment on the Circumference series to the bright colors that swirl around the space. While standing amidst the wall-to-wall artwork, it is impossible to believe that one of Treviño’s biggest concerns was his ability to fill the space with his work. Treviño built a world that all visitors can immerse themselves in.

So why Stab of Guilt? Treviño knows

One of the communities the Wellin serves most closely is Hamilton College students and faculty. As a teaching museum, the Wellin Museum works in close collaboration with artists to plan a programming week where students can engage directly with the artist through museum tours, artist talks, and class visits. Treviño shared that he was initially nervous about his packed schedule and the variety of classes he would speak to,

from Hispanic Studies to Physics. Admittedly, Treviño explained, he knew nothing about physics. But after those conversations, he

7

jokingly remarked that “now I feel like I can be a physics professor.” The robust week of programming brought new ideas and events to campus but also was an entirely new experience for Treviño himself. This exhibition is his first survey show, exhibiting work from 2008 to today. Treviño reflected on the reception of his work, “Once you put art out in the world, you can’t control everything, when it’s up on the walls, who knows how people are going to respond to it.” He shared that he was surprised by just how hard the students would look at and think about his artwork. When asked what he learned from working with the Wellin, Treviño responded practically and frankly about the hard deadlines and the organization required to pull an exhibition together. Treviño recalled the process of collecting and organizing his artwork and that he had to go back in computer files to uncover and recall what all the 119 circumference works were referencing. Moving forward, he explains that he will document his files in a more detailed way to avoid this.

While initially intimidated by the size of the 5,000 square foot gallery space, Treviño now finds inspiration in his accomplishment of not just filling the space but commanding it with color and movement. He explains that “this exhibit has been game-changing. You can sit in your power for a second and be like, wait, I filled the space.” Even so, many other works didn’t make it into the show. Thinking about the future, Treviño wants to work bigger and explore costume design further. “I

feel like the floodgates have opened,” Treviño says, referring to Regalia: Intuition, Regalia: Premonition, and Regalia: Foresight, the series of lifesize capes and headdresses, custom fitted to his measurements, that absorb the visitor’s attention upon entering the exhibition. With the confidence and experience bestowed by mounting a solo exhibition, Treviño wants to get back to his theater roots and possibly design a show. Treviño began his artistic journey in the theater world and transitioned to painting later on, sharing that “life is long, I had a whole theater career, now I’ll dip my toes back in.”

Rene Treviño: Stab of Guilt explores history, identity, astronomy, and queer culture. All his work is generative; from the artist’s studio to the experience that occurs within the exhibition, the work builds on itself. Treviño also reminds us that art expresses one’s lived experience as he infuses his gay Mexican-American identity into this colorful, campy exhibition. Through this art, Treviño not only explores

his own identity but also challenges viewers to think about themselves and how they interact with the art and world around them.

8

9

Photo by John Bentham

Photo by Joseph Hyde

10

11

By SyDney piCColi

By SyDney piCColi

12

hen I think of artists engaging with their environment, my first thought is the prominent land art movement. During the 1960s and 1970s, artists began physically engaging with the natural world in a way that had not been seen before. Artists like Richard Long and Andy Goldsworthy only used natural materials, while others, such as Robert Smith, carved sculptures from the land. Distinct from her counterparts, Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta explored the relationship between the female body and the natural world. In Árbol de la Vida, for example, Mendieta, completely covered in mud, leans on a tree with her arms raised, implying that they are one. The land art movement demonstrates how each artist’s experience with what they consider their environment has uniquely shaped their practice.

Ceramics professor Rebecca Murtaugh connects the natural environment and art right here on campus. She is currently experimenting with making abstract sculpture from locally-dug native clay, including clay obtained from the ground just outside the science center! Alongside exploring her own artistic relationship with the environment, she teaches a class called Art and the Environment focused on botanical dyeing, ceramics, and environmental intervention. “My class challenges students to think about their surroundings in a way that they might not have before. There’s so much richness in the way that we interact with what we might consider the environment,” remarked Murtaugh. The class was born out of the COVID-19 pandemic: “Anytime you walked near someone you were thinking about the air you share. Or the railing you don’t touch. All of a sudden the objecthood of the world became something that could damage the bodies and put our families at risk. How do we think about our relationship to the environment when we are in an environment where we’d rather be apart from it?” However, Murtaugh does not define the environment for the students. “The students define what the environment means to them. That’s the most beautiful part because it means something different to every person,” she concluded. Art in the Wellin’s collection further demonstrates how each artist’s distinct experiences with the environment inform their creative practice. For example, artist vanessa german uses objects that she finds in her neighborhood of Homewood, in Pittsburgh, to create power figures, including “i

will never smile again” in the Wellin’s collection. Her power sculptures are inspired by nkisi power figures, which are intended to heal and protect the Kongo peoples of central Africa. In a similar vein, german designed “i will never smile again” to protect herself and others against contemporary injustices, such as racism and gun violence. She describes her sculptures as “an army of healers. an army of weepers. an army of protectors. armed and dangerous upon the lie.” As a queer black woman, german has never felt or been safe in her environment. In her own words, she uses her artistic practice to “[fight] to create a sustainable, whole existence for myself; to be safe to use my imagination. In an environment for your body and soul to thrive, the tools, tactics, and strategies of true sustainability cannot be separated from hope, love, creativity, goodwill, and transformation.”

Similar to many artists working during the land art movement, sculptor Donté K. Hayes engages with his environment through natural materials. Although he used to utilize clay that he made himself, he now grounds his practice in stoneware clay—a specific type which, once fired, transforms from brown to black. “Clay from the ground is a part of us. When you’re working with clay, you can smell that material. You know when it needs to be rewetted because it starts to get dry in your hands and it starts to give like these little crumbs on your hand,” described Hayes. “It’s slower. Things are slow and you become one with something,” he furthered. In his own words, his sculptures “preserve, empower, and document the past and present to initiate healing and understanding for the future,” marking a similar purpose to german’s. When I look at Hayes and german’s work, I feel as though they are both imagining a future—an environment— where a love ethic and shared humanity prevails. Although the land art movement was pivotal in shaping how artists thought of their environment, Murtaugh and artists from the Wellin collection remind me that the environment is ultimately ours to define and explore. For artists like Hayes and Goldsworthy that means working with natural materials and for artists such as german and Mendieta that means thinking critically about how their identities shape their creative practices.

13

15

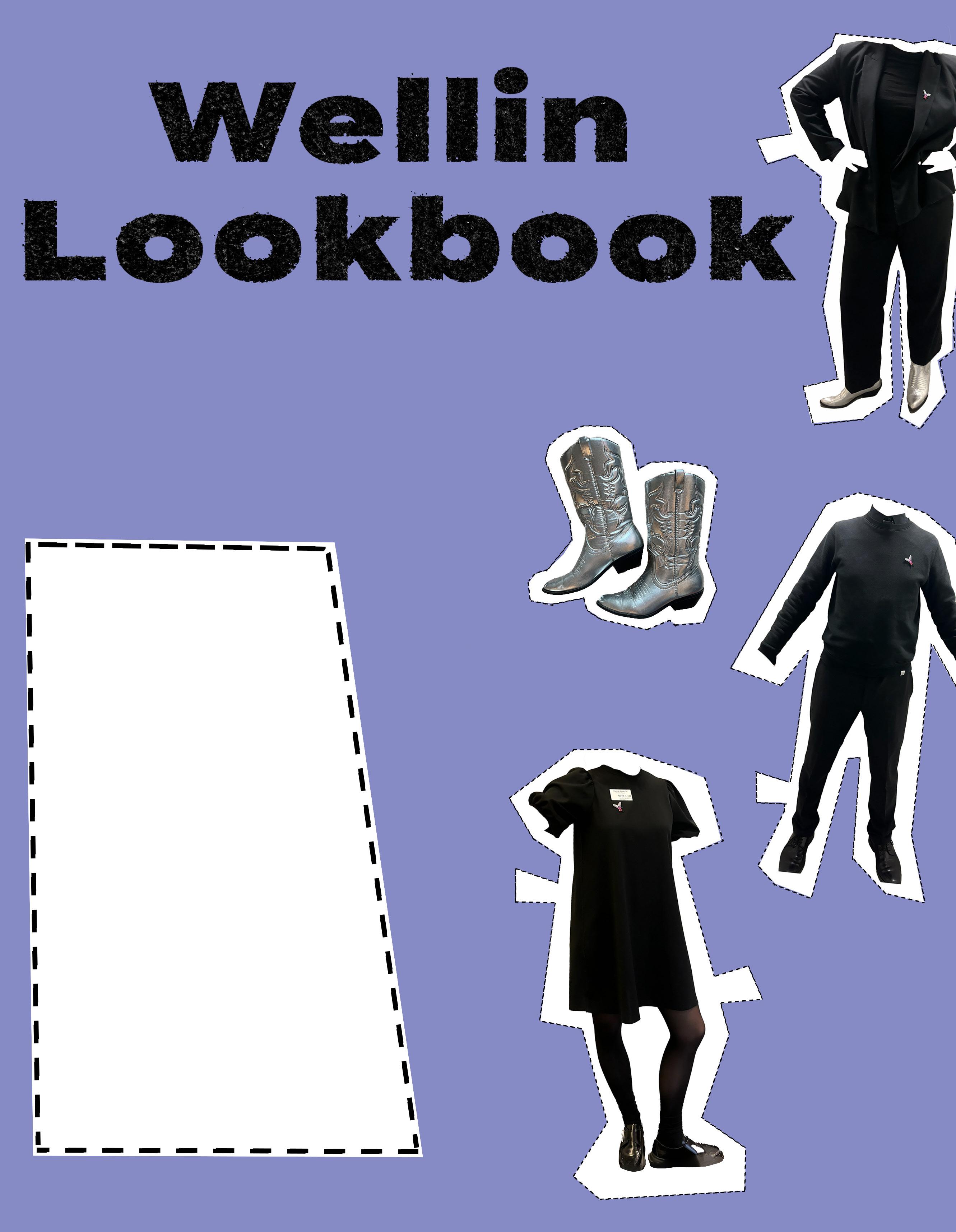

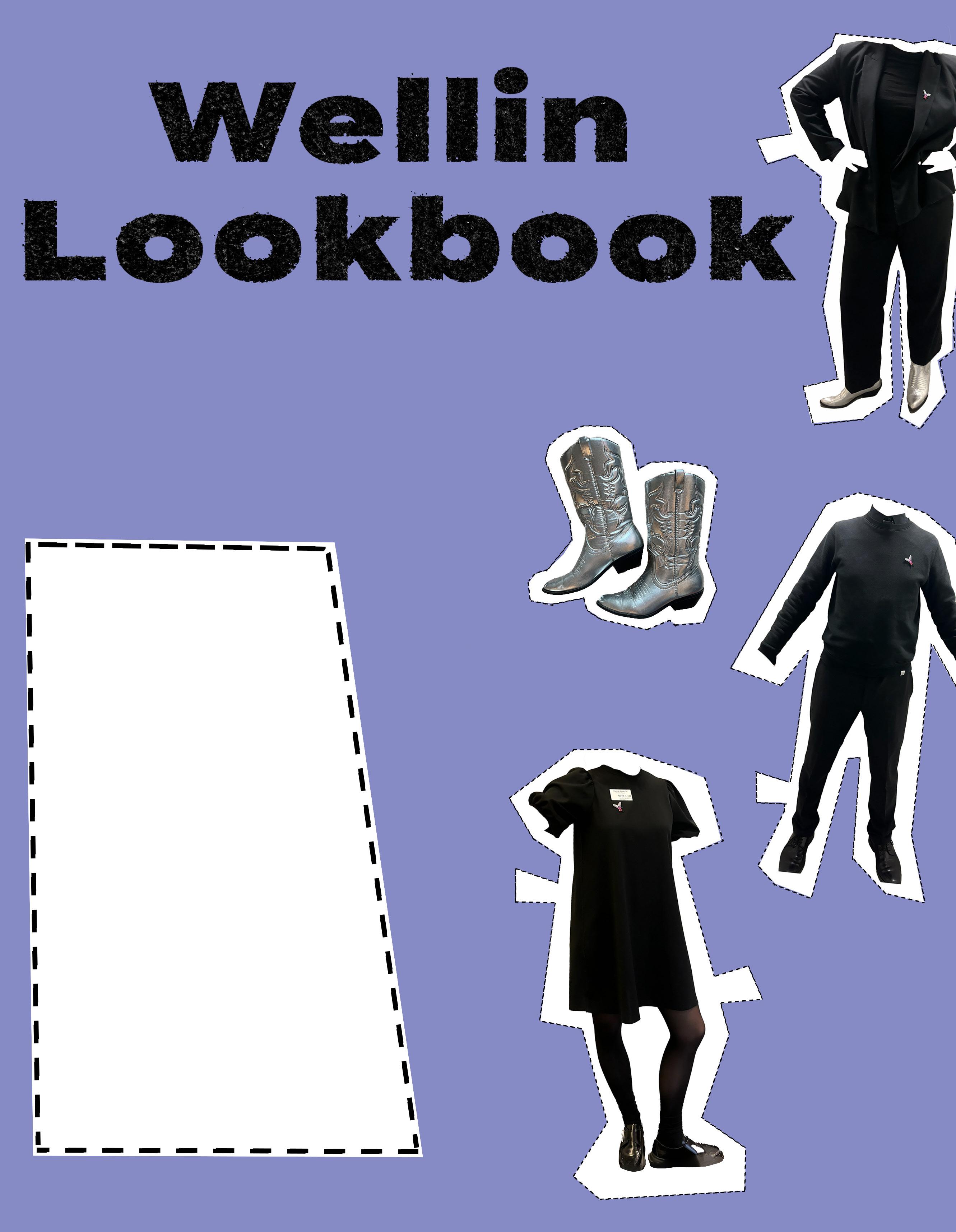

Each day, the Wellin is filled with lively and vivid students, professors, artists, and art. The gallery and hall are imbued with color, each painting, print, and sculpture animating the space. Through required to wear black, docents don’t restrict themselves to drab or dull outfits. Their colorless outfits remain full of dynamism, from their sparkly shoes to geometric jewelry. On the opening day of René Treviño’s Stab of Guilt, we photographed the vibrant looks of docents, from head to toe!

Which look would you choose?

Cut out your favorite outfit and pair it with any accessory!

16

17

The Collection team sat down with three graduated Hamilton students

who worked at the Wellin. We captured their reflections on what the Wellin meant to them during their time at Hamilton College and now that they are well into their professional lives. Here are the interview highlights, which have been edited for clarity.

Jane taylor GraDuateD from hamilton in 2022. She maJoreD in art hiStory anD BioloGy anD WorkeD aS a Wellin DoCent.

I did not have an inclination to go into art when I started college. I was planning on being pre med. When I started taking an art history class the idea was I’ll minor or major in this and it will be the fun creative thing I do to make sure I don’t go crazy in pre med classes. The more I did it, the more it became the opposite where the bio and the science stuff was really fun, but I knew I did not want to do that going forward. The art history was something I became more and more kind of enamored with.

I started working at the Wellin in my sophomore spring, and actually it’s so funny. I was so excited about it, and I had an interview with Marjorie before I was hired and I literally missed the interview. I just remember I was mortified because I was like ‘Oh my God, how did I do that?’ It was also when we got sent home for COVID, so there was no excuse. I wasn’t doing anything. Thank god she gave me a second chance, and I got hired because I do think of the Wellin as one of the most impactful parts of my college career.

I moved to New York City in August of 2022, and I did not have a job. I had very limited savings, so I got a job at a coffee shop for a little bit. And then in between that, I was just applying to so much stuff, just throwing my name in everywhere I could. At first, I was really picky about everything, because I wanted a museum and I wanted to just do that. It was a lot of hard feeling, a lot of rejection from places, especially because I feel like with Wellin and other jobs I did in college I felt very qualified, which was frustrating. Then, I actually stumbled upon one of those Hamilton emails that I usually never go through, but this one was something about Tracy Adler, and that she had given this interview where her kind of advice to young people trying to get into the art world was basically, like, ‘don’t be picky, just do whatever is somewhat related, it will help you’ So then I started just expanding my applications and searches a little bit. And I applied to a bunch of galleries, and I started working at a gallery in December, then in November I got a promotion.

18

mattheW tom GraDuateD from hamilton in 2020. he maJoreD in StuDio art anD literature anD WorkeD aS a Wellin Summer StuDio aSSiStant, SoCial meDia aSSiStant, anD DoCent.

Working at the Wellin was great because it’s such a small organization, so I really had the ability to wear different hats. In the first role that I had, I was working more so with the permanent collection and database entry. And then, I realized that that perhaps wasn’t the angle that I was looking for within my own career and life. So I was fortunate enough to stay on board working as a social media assistant and creating content that was outward facing about the museum, but also trying to connect the museum with the local Hamilton community and audience. That was really exciting because I had the opportunity to speak to my peers through the voice of the Wellin and see how I was able to translate all the great things that were happening inside the museum to these audiences. Using that social media lens, I was also able to explore education and how to work with local communities, which really established me to get further internships down the line.

To me, the Wellin Museum was really what brought cosmopolitan life to my Hamilton

experience. I felt like I was in dialogue with other institutions with the contemporary art world because of the work that I was doing at the Wellin and the familiarity I was getting with different artists in the permanent collection. The Wellin is also such an intimate setting. We see the artists and work with the artists. It’s also pretty unusual to have this entire staff of college students as opposed to other young professionals, but we get this breadth of experience and can really do what we love.

I loved the docent culture because I would walk in and wave at the person at the desk and talk for a little. Also, something that somebody once told me too was that if you work at a museum, the works in the galleries will become your friends. I feel the same way about the Wellin. Like, the Jeffrey Gibson punching bag, A VERY EASY DEATH, that was acquired before my time, but you still talk about. The docents are connected in the things that we know and shows that are putting on. There are markers of time, which I think is really exciting.

Charlotte SimonS GraDuateD from hamilton in 2016. She maJoreD in StuDio art anD WorkeD aS a Wellin DoCent.

I started working as a docent at the Wellin the semester it opened for the campus. I worked there through all the first iterations and baby steps that the Wellin was taking on campus. And it was cool to be a docent. On some days I got to sit and do my homework and count the number of visitors. And on other days I got to teach children about art. It was a whole range, but I really got to explore a lot of what I was interested in the museum and gallery world. It was also great for public speaking.

I even took a curatorial class with Professor Knight, where we dove into documentary photography and photojournalism. He invited a few photographers to present their work with the

Wellin and the students got to curate and organize the exhibition, including the write ups and audio components. So my work was ultimately presented in the Wellin, which was really cool.

I was doing a lot of internships at museums and I ended up deciding that that path was not for me. It feels very white gloves like you’re on the other side of the glass. You can arrange the art, but you’re not making it and as an art student, that was the part that I ultimately gravitated towards. So I ended up deciding to go into the direction of advertising where I could use my creativity to get a stable paycheck.

19

By miriam lerner

By miriam lerner

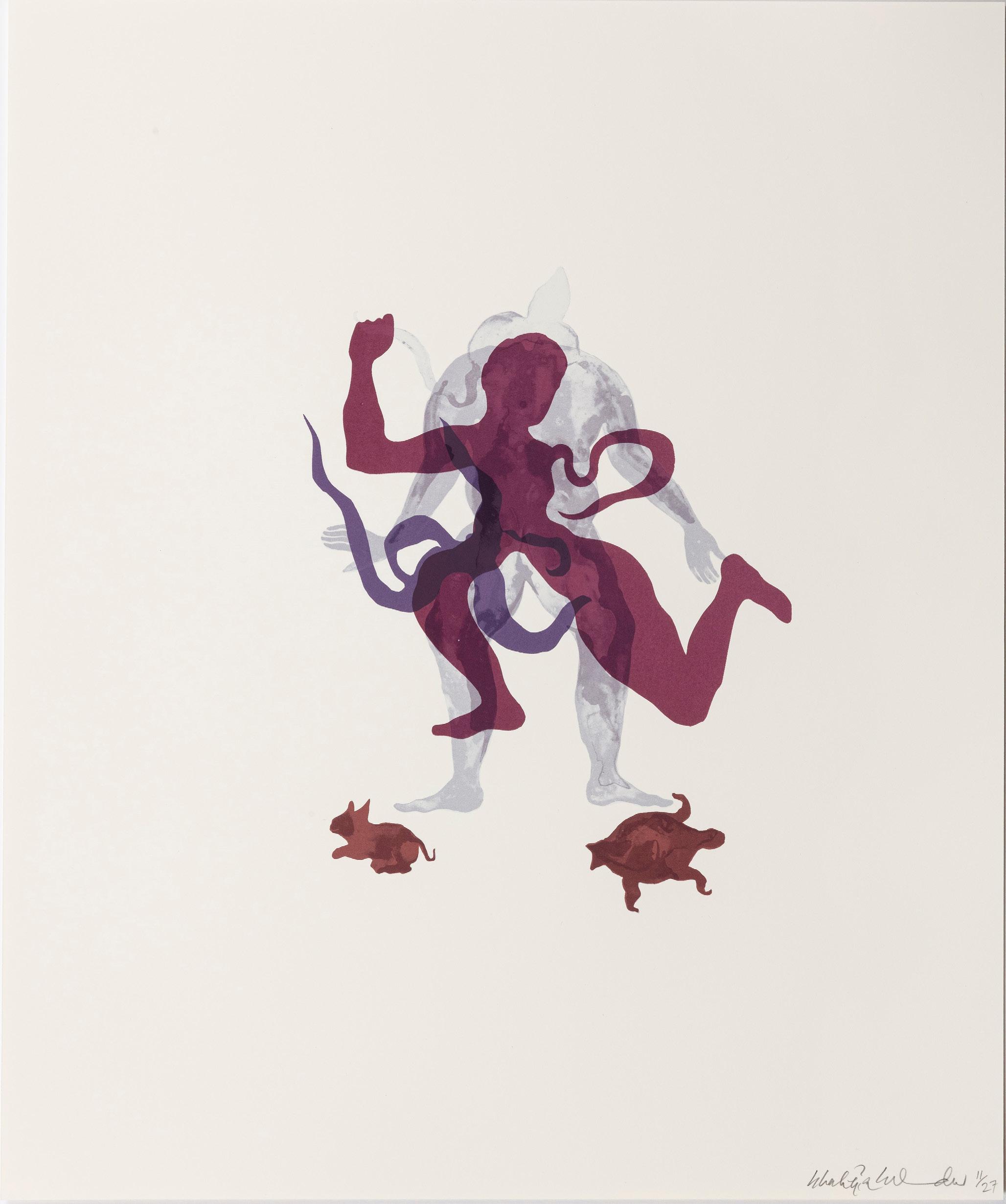

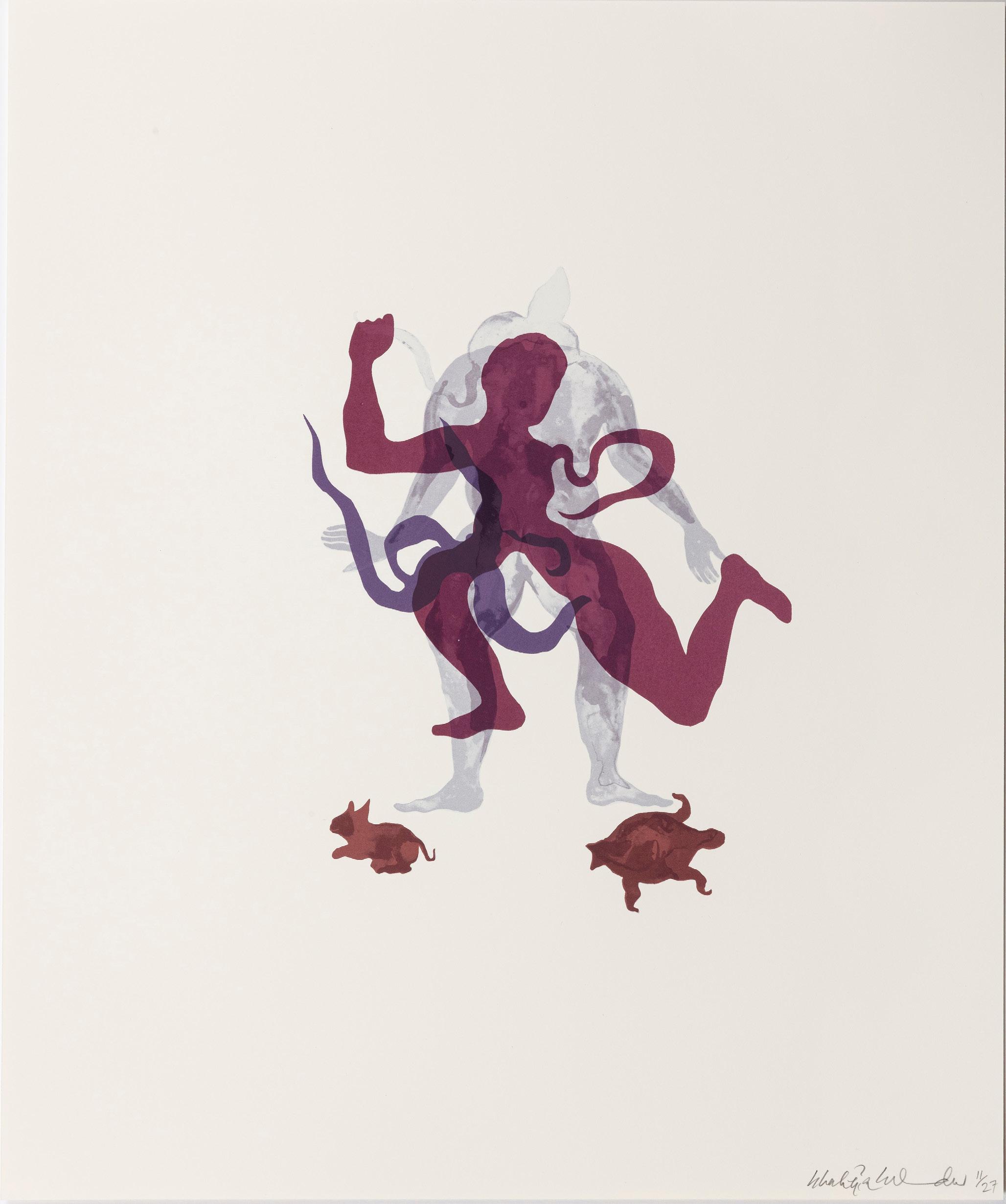

embark/Disembark IV, a lithograph by Shahzia Sikander, is a recent acquisition from 2023, and is part of the Wellin’s initiative and emphasis on collecting global contemporary art. This lithograph is exemplary of the cross-cultural and intersectional work made by contemporary artists today, as geographic and linguistic boundaries between artists around the world are dissolved due to continual technological advances. At the Wellin, works of art that demonstrate the processes and ideologies behind art-making are valued —they serve as tools for teaching about the intersections of global art throughout history.

Shahzia Sikander, a Pakistani artist based in New York City, works to subvert the traditions of Central and South Asian manuscript painting. Throughout her career, she has won numerous prestigious awards, including the MacArthur Foundation Fellowship ‘Genius’ Award, granted to her in 2005 (D’Souza). After spending several years studying traditional miniature painting, an artform often neglected in the art world, Sikander decided it was in need of reconstruction. Sikander then launched the “neo-miniature” artform, with the intent to question and remake traditional miniature paintings (D’Souza).

Through her “neo-miniatures,” Sikander exposes the Western gaze in historical miniature painting, bringing attention to the role of Eurocentric perspectives in diminishing and neglecting studies of Central and South Asian art. By using this artform,

Sikander both indirectly and directly questions the systems of power that surround her, including the dictatorship of Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq in Pakistan, and the American government after September 11th, 2001 (D’Souza). She considers the role of 9/11 particularly in constructing the notion of Muslim women as powerless, an idea which served as justification for the brutalities and losses caused by the American-led War on Terror (D’Souza). Through her “neo-miniatures,” Sikander works to destabilize contemporary biases toward Islamic societies and Muslim women, undoing some of the ideological harm done in the past few decades.

Embark/Disembark IV considers the notion of womanhood and the mythical woman, using art to reconstruct the Western ideals shaping representations of women and the female body. In this work, Sikander formulates a fantastical and fluid body, one which intertwines traditional myths with the traditional manuscript style, and yet makes room for contemporary definitions of personhood. Through her layering of translucent, yet vivid forms, she brings life to an ancient style, blending art historical traditions with new ones, and collapsing notions of time and space. Embark/Disembark IV encourages viewers to look beyond the present toward spaces and times that subvert contemporary understandings of power, gender, and art.

20

21

22

You can tell a lot about a person seeing what they keep at their desk! We had the opportunity to meet with Marjorie Hurley, Museum Educator, and Docent Program Supervisor at the Wellin, to get a peek at her office.

For Marjorie, her office prioritizes functionality while sparking joy. Her office serves as the materials supply closet for art-making events, and so she keeps the space organized so that student docents can access materials. Likewise, she keeps personal notions, including pictures and postcards, to brighten up every day.

Artist Rene Treviño, while visiting Hamilton College, was struck by the star charts mapped by astronomer C.H.F. Peters, who dedicated his life’s work to tracking and mapping the stars at the Litchfield Observatory at Hamilton College. Formerly standing in front of the current Suida house, the building was torn down in 1918. We dove into the college archives to find images of his historic building, as now all that remains is the pedestal which once held up the second largest telescope in the United States!

By Hannah Dillon

The Wellin Museum of Art mounts original exhibitions bolstered by rigorous research and scholarship. Long after the artists and exhibitions leave Clinton, New York, the shows live on through their exhibition catalogs. I sat down with Tracy Adler, Johnson-Pote Director of the Wellin, to learn more about the process and intention behind these beautiful catalogs that boast international acclaim.

For over 25 years, Adler has collaborated with the NYC-based design team, Tim Laun and Natalie Wedeking, to design the didactics and the graphics for the shows at the Wellin. Together, the team creates a graphic identity specific to each exhibition. Adler notes that “the design is always in support of the work.” From the color of the walls to the typography of the didactics, the graphic identity of the show considers style, history, context, and mood in meticulous detail while centering the artist and the themes of the exhibition. There is an “intellectual grounding to every selection that goes into the graphic identity and into the exhibition,” Adler explains.

Beyond the aesthetics of the books, each catalog contains scholarly writing about the exhibiting artist and their work. This academic writing furthers the scholarly efforts of the Wellin and is very significant for many of the artists who have yet to have critical writing about their work. The process of choosing essayists begins with conversations with the artist regarding which scholars, curators, and critics are familiar with the artist’s work. Once the contributors write their content and the exhibition has been documented through photographs, the final layout and printing processes begin.

Adler explains that she and the design team are focused on every aspect of each catalog, to the extent that “there is not a margin that we have not discussed or labored over, there is not a word that we have not questioned.” Just as the writing, design, and layout demand significant attention to detail, so too does the materiality and printing of the books themselves. The Wellin works with a printer in Italy, recommended by the Wellin’s longstanding publisher DelMonico Books,

26

to ensure the quality of the printing matches the intentionality of the book. From the type of paper to the spot colors and varnishes, every decision is made with the artist and their work in mind. When working on the Yashua Klos book, an artist whose primary medium is paper, designers Tim Laun and Natalie Wedeking worked directly with the printer to invent a new paper technique inspired by the custom wallpaper from the exhibition for the endpapers and section breaks. Quality and attention to detail are at the forefront of every decision, including the reproductions of the images. There could be six rounds of color correction before a final image is ready for print. Adler explains, “Editing a book is as much work and maybe even more work than curating an exhibition. But the books are the thing that endures. The show is very temporal and comes and goes but the book is there forever. The book tells the story of the exhibition.”

Each book celebrates and showcases the exhibition and acts as a record of that specific

show at the Wellin Museum. Adler explains the importance of these publications, saying “We feel a responsibility to the artist, the show, and the contributing authors to make sure it is the best it can be. It’s also a way to raise the profile of the college through our publication programs because the books are distributed all over the world.” The Wellin collaborates with DelMonico Books, a leading art book publisher, to copublish and distribute the books. As a small museum, the Wellin does not have the staff or the network to effectively distribute the books independently. Partnering with DelMonico Books, an imprint at Distributed Art Publishers, allows for the exhibition, recorded in print, and the generated scholarship to reach a global audience. The Wellin’s books can be found at major museums and international book fairs.

While the exhibitions are only up for a finite period, the catalogs enable the Wellin’s exhibitions to expand beyond the walls of the museum and allow the shows to live on far beyond their closing date.

27

Photo by Janelle Rodriguez

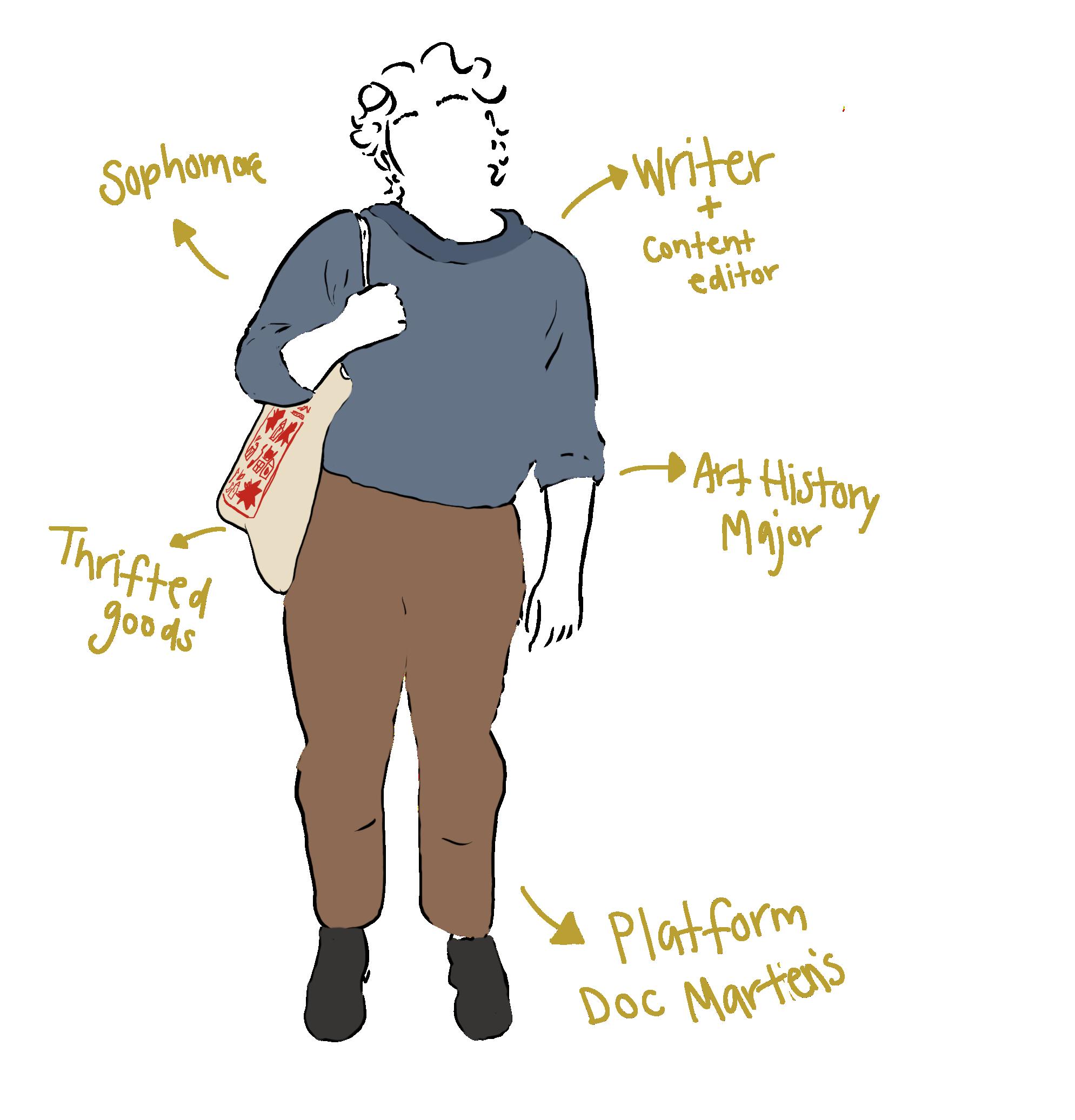

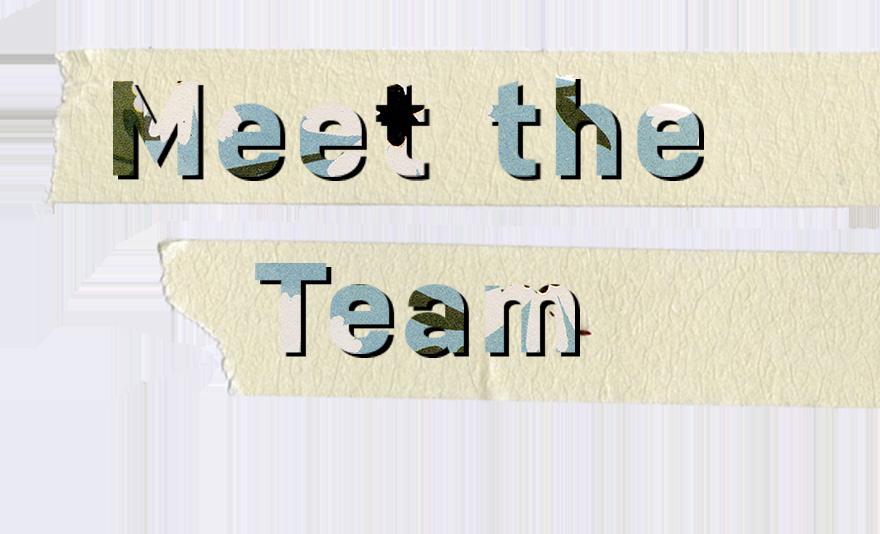

William hayneS

Collections Assistant & Docent

Beginning of my sophomore year, Liz had me do a task where I had to draw up a mock exhibition for the Object Study Gallery. I ended up choosing a collection of photography. I had to write the wall text labels and find out how to organize all the artwork in a way that makes sense in a cohesive narrative. I got to learn about the intentional choices that curators make and how their narratives support artwork in a meaningful and productive way.

Working at the Wellin entirely changed my trajectory. I was not an art history major before I started working at the Wellin. In fact, I didn't even seriously consider it. My experiences at the Wellin also ended up getting me a position at a gallery in Edinburgh last year over the summer, which I wouldn't have had before. And now it's affected the fact that I decided that I want to go work in the art industry following my Master’s of Art History graduation.

docents to see the positive impact the Wellin has had on their college experience as well as their post graduate plans.

Celia DorSey

Communications Assistant & Docent

The magazine has been really important for me finding a role as a leader on campus as well as finding confidence in working in a professional environment. I think the staff members at the Wellin have been super influential in my time here. I feel like if I needed support in any kind of facet I would be able to get it at the Wellin. My ability to have a portfolio from Collection has really immensely helped me with my interview process for full time jobs and for internships the past couple of summers as well. It is definitely helpful in terms of growing my ability to talk about how we give tours and how we work in collaborative environments. After college, I will still be in the creative world and I think there are a lot of things that we learn in this Wellin’s setting that can be applied to all sorts of different industries.

JaCoB piazza

Docent

When the position for the docent was posted I rushed to apply and was lucky to get an interview. The Wellin has been one of the most consistent parts of my experience at Hamilton, and was one of the things I missed the most while abroad. To me, the Wellin represents the best things about Hamilton: curiosity, academic excellence, and uniqueness.

After leading one of the K-12 tours, a kid wrote a reflection on his time at the Wellin and addressed it to me. It felt very rewarding. The Wellin has also provided me with important experiences in pedagogy that will assist me in my future career in education, and I am open to museum education, although I lean towards secondary school currently.

maDeline pittel

Docent

The Wellin has been such a home on campus because I love the docent group that I work with. I've enjoyed watching myself gradually become more comfortable giving tours and learn to be present to people in a way that is accessible and engaging.

The Wellin is a really open place. I am working at an auction house after graduation, and auction houses tend to not be super accessible. The Wellin has flexible hours and does not require any money to enter, which I think really speaks to the ethos I want to bring to the auction world.

Sae GleBa

Communications Assistant, Student Liaison & Docent

Beyond school, working at the Wellin is the single most impactful thing I’ve done at Hamilton. I found a role that I feel very comfortable and confident in and a true passion for museum education.

When we work with local art educators, we really get to see their engagement with art in the community and it allows the Wellin to reach beyond Hamilton students. During the fall of sophomore year, we had a number of our educators come in to look at the Sarah Oppenheimer show. It was a tough moment and people didn’t really click with the installation. Getting to sit and talk through that experience with a bunch of art educators fostered my passion for museum accessibility work.

29

eliana GooD

Docent

I was motivated to apply after my freshman spring. I went to the Michael Rakowitz exhibition and had a tour that was led by Alexander Jarman. I was just blown away by the exhibition — how interdisciplinary it was and how there were opportunities for students to meet and interact with the artists. As an art student, it was really cool to me. I wanted the opportunity to meet these amazing artists and see what it takes to put on a show like this.

Since working at the Wellin, my public speaking skills and ability to facilitate a group learning experience has drastically improved. I find myself being able to think better on my toes and communicate more effectively and thoughtfully.

anna o’Shea

Education Assistant & Docent

The Wellin has generally been super central to my Hamilton experience. It has been a space for community, for learning about myself, and for continuing to expand my understanding of art and artmaking practices.

I think one moment that has really stuck out to me has been in one of the K-12 programs I worked where we were trying to get middle schoolers to draw sound in congruence with the Rhona Bitner exhibition. I remember having so much fun really trying to challenge them to expand their understanding of visual depictions of concepts.

I would say that the Wellin has impacted my post grad plans really heavily. I’m currently in the process of applying to positions in museum education and my role as student education assistant at the museum has definitely fostered my understanding of children’s programming.

katie rao

Docent

I've always loved being able to learn directly from the exhibiting artist about the show before the opening. I remember speaking to Yashua Klos about his tree sculpture that stood in the center of the gallery and gaining a new perspective about how his work functioned as a collective.

Having worked at the Wellin for nearly three years, I find that it continues to inspire me to pursue a career in the arts. The Wellin has been a special place on campus that allows for the intersection of various disciplines.

30

hannah Dillon

Communications Assistant, Student Liaison, and Docent

At the Wellin, I’ve really made connections with adults and people outside of my normal circles, including other docents and people that I wouldn’t normally run into. It’s also been a place where I can kind of grow within my position. I’ve learned about teamwork just from interacting with people when I have to give a tour for a class and when I am paired up with someone I don’t even know.

Whenever the magazine gets published, it’s a really rewarding moment. Seeing the printed final copy and being able to say we wrote this and did it for the Wellin and students at Hamilton is super cool. It is also great to see the lesson plans that I made over the summer implemented into our programming events.

I’ve learned that I want to be in an environment that allows me to keep learning and where people want to have conversations and are excited to be there. That’s what I’ve felt at the Wellin for these past three years. I also want to work in an environment, whether it’s in a museum or classroom, where it’s a place of movement and learning. Even just the fact that we have new shows each semester is exciting.

miriam

lerner

Communications Assistant & Docent

When I first visited Hamilton, I came to see the museum with my dad. It was the Elias Sime show, so they had the rose sculpture outside made of computer parts. I thought that it was really cool, and that I wanted to come and work here. I have also always really loved art and going to museums, so I thought it would be really special to work hands-on with the art and get to know the artists.

The Wellin has been a place where I have been able to make lots of friends, be creative, and work toward something that means a lot to me. Sae, Celia, and I came up with the idea for Collection magazine and have since been able to go really far with it. It has been so meaningful to see it grow as much as it has, as we learn from our mistakes. I have also really loved learning about the museum and the artists through our many conversations and experiences with them.

I am pre-med, so it is definitely a very different kind of work from the work I will be doing, but it has taught me to communicate with a variety of people from little kids, to local teachers, and working artists. It has also taught me to work really hard, manage my time, and be creative, which will definitely help me as I move forward.

We would like to thank Marjorie Hurley for her unwavering support over the last few years as we have grown into the docents we are today. We would also like to thank Tracy Adler, Alexander Jarman, and the entire Wellin Staff for creating an environment to learn, explore, and grow. We are forever grateful for our experiences working at the Wellin.

31

Green DreSS maDonna With CloGS

Green DreSS maDonna With CloGS

moDern maternity: explorinG Contemporary interpretationS of the timeleSS mother anD ChilD

By miriam lerner anD Sae GleBa

throughout history, there have been hundreds of representations of the Virgin Mary and Child. Depictions of this subject have ranged from Italian Renaissance paintings to twelfth century golden plaques. Mary’s image is iconic and idealized; she represents perfect divinity, acting as a standard impossible for women to achieve. Today, her representation has been shaped to encompass a range of experiences of womanhood. Spanning a variety of mediums, artists such as Ann Agee, Elizabeth Catlett, Declan Haun, and Carrie Mae Weems each provide their own interpretations of the conventional Madonna and Child. Dealing with questions of feminism, motherhood, race, and domesticity, these four contemporary artists subvert the traditional image of the Virgin Mary.

Ann Agee’s Green Dress Madonna with Clogs depicts a woman in a green dress, seated, holding her child. Made of red earthenware, this artwork provides a representation of the Madonna that is modern, intersectional, and feminist. Agee draws from hundreds of idealized depictions of the Virgin Mary, which center around religious themes of motherhood, domesticity, and chastity. Rather than perpetuating the gender norms that accompany traditional portrayals of Mary, Agee molds her work into a woman who opposes and works against the constraints of religious, patriarchal expectations for women. Instead of holding a male child, Agee’s Madonna holds a baby girl—an explicit undoing of the gender norms sustained by Christian art and ideology. This work is part of a larger series entitled Madonnas and Handwarmers. This series consists of a range of female figures, holding their female children, wearing an assortment of colors in non-traditional poses. It depicts the range of women’s experiences, while demonstrating the collectivity of womanhood.

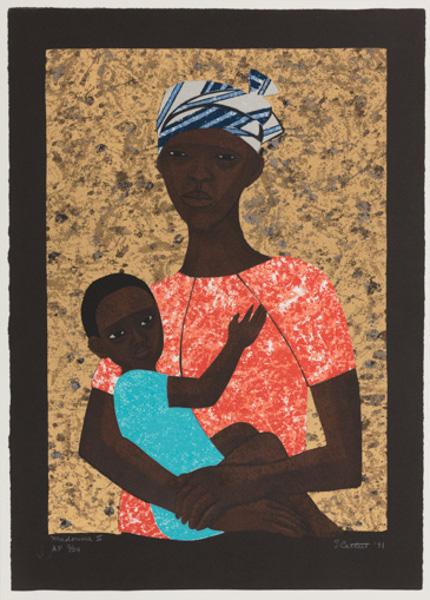

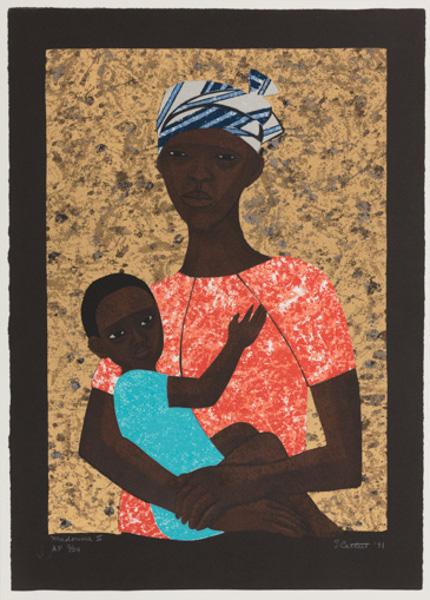

Madonna II, a 1992 screenprint by artist Elizabeth Catlett, depicts Mary and Christ Child in a manner that references both the art of the Italian Renaissance and African representations of mother and child. Catlett references artists like Giovanni Bellini, an Italian Renaissance painter, as her figures breach their frame and enter the space of the viewer. Catlett’s incorporation of this recognizable, eurocentric visual culture highlights what is revolutionary in her own work: the introduction of African American

figures of divinity. She strays from the conventional features associated with the Madonna—rather than the white, blue-eyed, blonde-haired Mary, Catlett portrays holiness as black, working women. She depicts domesticity and womanhood in a way that is recognizable and yet attainable—the ideal of womanhood becomes an illustration of what is palpable and genuine.

Declan Haun, an American freelance photographer, sought to capture in his documentary photographs “simple statements of fact or feeling.” Emerging amidst the Civil Rights Movement, this image is from a series he made at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28th, 1963. The March on Washington brought together over 250,000 people at the Lincoln Memorial to advocate and demonstrate for the civil rights of African Americans. Nearly 3,000 members of the press covered the event, including Haun, who focused on the emotion or story one subject could tell. If Haun’s photographs are simple statements of fact or feeling, then Woman giving bottle to infant, March on Washington captures a “simple” moment of intimacy and mundanity amidst a great historical moment and social movement.

Contemporary artist Carrie Mae Weems embraces activism throughout her work, crafting an œuvre that explores notions of race, gender, family, and class in her largely photographic practice, creating images equally tender and telling. Weems’s academic background is grounded in art and in storytelling, as she studied folklore in graduate school. Her capabilities as a storyteller permeate her photography practice. Narratives, often personal, become inseparable with the art she creates. Untitled (Woman and daughter with make-up), from the “Kitchen Table Series” depicts the process of working through the complexities of Black female self-expression, grappling with her identity as a woman and an artist. This photograph is part of a body of work in which Weems explores herself as a “bodacious” Black woman, a traditionally marginalized figure, fulfilling a range of traditionally feminine roles—as mother, as lover, as friend— that unfold around the domestic realm of the kitchen table. These photographs are accompanied by a series of third person text describing a universal storyline of womanhood.

33

Remembering Basil Brown ‘24

We would like to express a content warning; this page includes mentions of death, suicide and struggles with mental health.

Basil Brown ‘24 worked for one year as a docent at the Wellin Museum, where today he is remembered fondly. We saw this magazine as an opportunity through which to honor Basil’s memory in a permanent, tangible way. We reached out to the Hamilton community, asking for contributions that expressed any thoughts or memories about Basil. We hope that this dedication will provide some comfort to all those grieving Basil, and that it will be a place that preserves his memory, and lets him be seen.

From Hannah Jablons ‘24

I miss Basil so much. I miss his laugh, I miss his hugs, I miss hearing his opinions. I miss asking him something and way too often hearing exactly what I was already thinking. I oftentimes would think about Basil since he transferred and sometimes I would reach out to him and get the same bubbly, kind, energetic Basil that I always knew. I also oftentimes would think about Basil since he transferred and not reach out, I will always regret these times. I’ll always regret not doing enough, which I think I share with other people. But I miss him. And I’m so angry. I’m so angry that this campus is not compliant with ADA guidelines, I am so angry that Basil had to beg the accessibility office to give him accommodations and even those did not improve his quality of life enough. I’m so angry that this school did not take care of Basil the way it should have. That anger will never go away. And neither will the things I miss. I’ll always remember Basil’s laugh, the memories we shared together, I’ll always remember his snapchat stories after he transferred that allowed me to believe he was happier there. Maybe he was. But I’ll never forget him. Basil inspired me when he was at Hamilton and he will continue to inspire me throughout the rest of my life to never stop making noise, to never stop laughing, and to never stop being kind and engaged with those around me for absolutely no reason sometimes. I miss you so much Basil. How could I ever forget about you?

34

From Geneve Halfman

‘25

“Remember, remember, the 5th of November…” Yes, I remember it well. I remember how you drowned in candy wrappers with me as we watched my favorite movie.

Or that time you came bouncing into my party when everyone else had bailed and invited your friends so it wouldn’t be empty.

You didn’t have to bring anyone— you seep into a room like sunlight, painting every surface and wrapping the walls in a warm embrace all by yourself.

I remember your unbounded curiosity— we met stumbling through a muddy Glen when you decided to explore Judaism, just because.

I thought we could talk about it over lunch. You thought we could talk about anything, often.

Just because.

Suddenly we were shivering over stolen sparklers, chasing each other with chalk powder, and eating chicken in the grass with our hands.

These are precious photographs sitting in my gallery of things that feel like the color yellow, the sound of a tricycle bell,

the edge of the brownie pan, and the shape of your smile.

Your fingerprints are all over my freshman year, and I think I found your crumbs on my Seder table.

The extra empty chair is for you, Basil Brown, on Passover and November 5th, in the corner of Pub and that one path in the Glen, in that spot in my heart that was dreadfully barren before you painted it with your laughter lines.

I will remember your power, the way your voice would break down walls, and I will remember your sense of adventure, your wandering soul.

I will remember your compassion, how it seeped through clothes like summer rain, and I will remember your fierceness, your refusal to stand still.

I’ll think of the hum of your voice and the wild, raw things that you’d do, and when I say the poem about remembering, I’ll say this one for you.

From Jane Taylor ‘22

I would never wish grief upon anyone, but I’m comforted knowing that we can grieve together. I think all any of us ever want is to be witnessed — to be seen in our totality and loved for it. I hope that Basil knew he was seen by us. It sounds macabre whenever I write it, but I truly hope he knew he had a community that would grieve for them, not with anger or with spite, but with love, care, and understanding.

35

Page 4

Cara Romero. Naomi, 2017. Archival pigment print, 46 3/4 × 40 in. (118.7 × 101.6 cm). The Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Purchase, William G. Roehrick ‘34 Art Acquisition and Preservation Fund. © Cara Romero. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Photo by John Bentham.

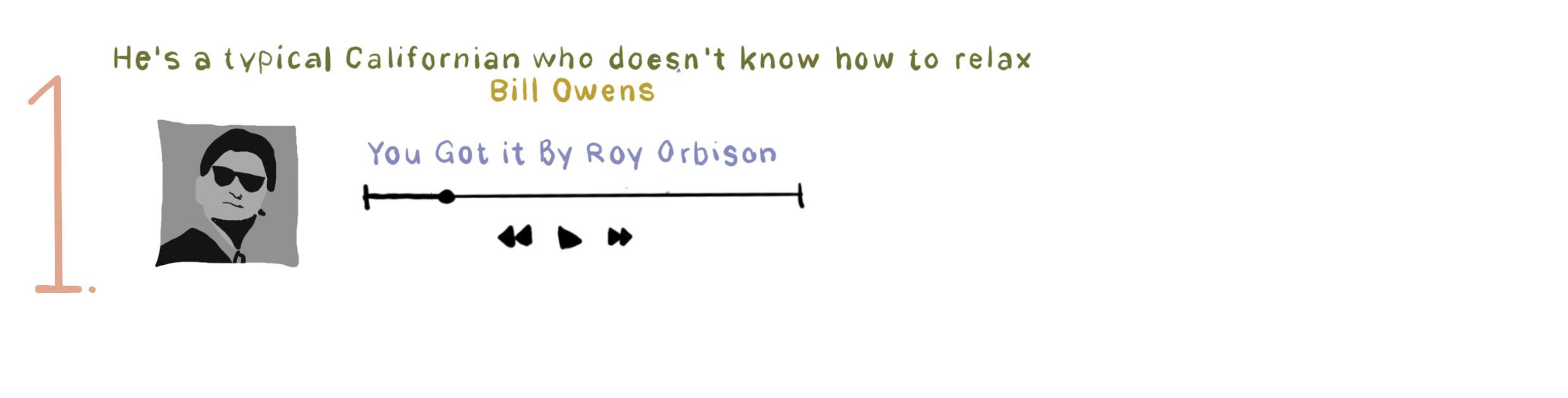

Page 10

Bill Owens. He’s a typical Californian who doesn’t know how to relax, 1981. Chromogenic print, 6 7/8 × 10 in. (17.5 × 25.4 cm). The Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of Thomas J. Wilson and Jill M. Garling, P2016. © Bill Owens. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

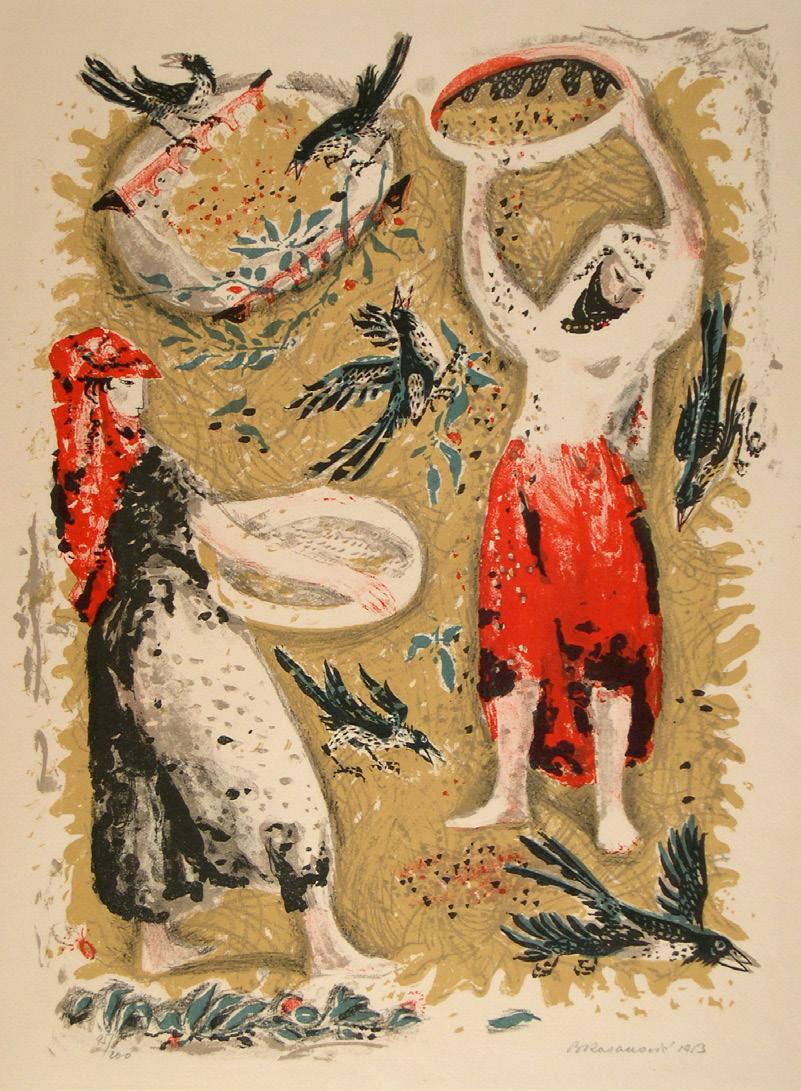

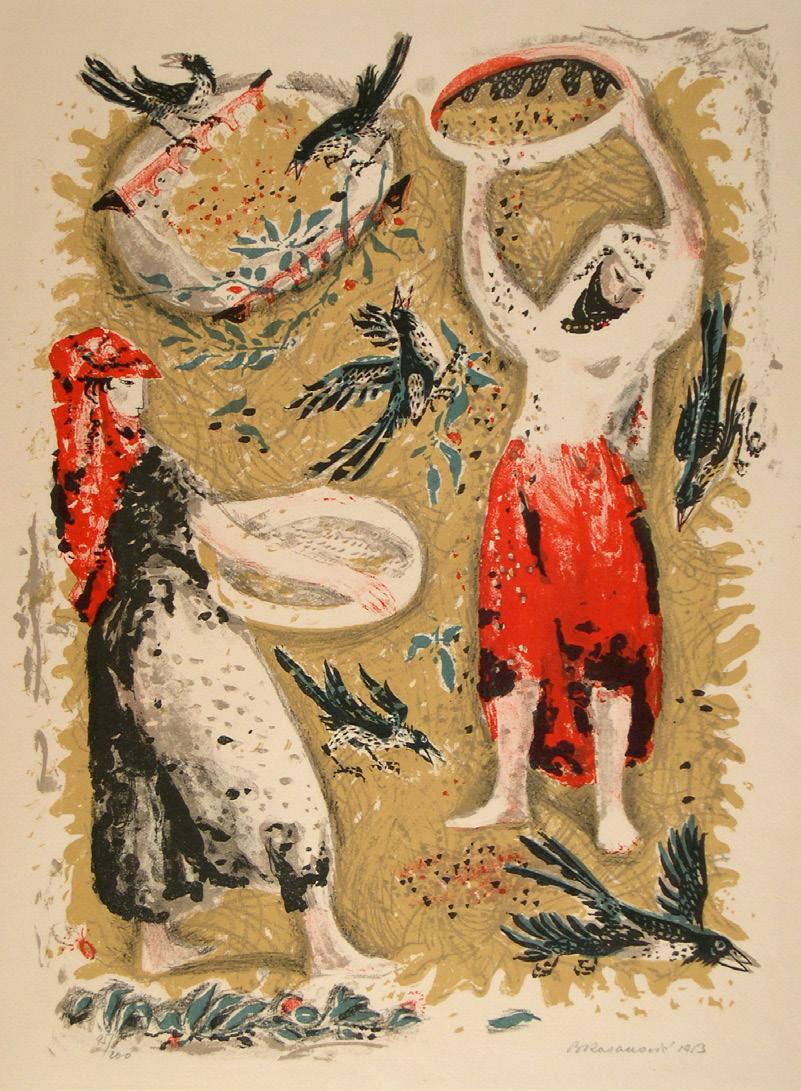

Bosco Karanovic. Wheat, 1953. Color lithograph, 18 1/2 x 13 5/8 in. (47 x 34.5 cm). The Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of Elbert Lenrow, Class of 1923. © Estate of Bosco Karanovic. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Peter Fischli and David Weiss. Coop Zürich, 1992. Artist’s book, softcover with text and images (12 pp.), 8 x 11 5/8 in. (20.3 x 29.5 cm). The Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of the American Federation of Arts. © Peter Fischli and David Weiss. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Page 11

Kenn Speiser. Looking Back, 1991. Woodcut, 30 1/8 × 22 3/8 in. (76.5 × 56.8 cm). The Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Purchase, William G. Roehrick ‘34 Art Acquisition and Preservation Fund. © Kenn Speiser. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Renée Stout. Wall of the Forlorn, 2022. Oil and acrylic on wood panel, 36 × 48 in. (91.4 × 121.9 cm). The Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Purchase, William G. Roehrick ‘34 Art Acquisition and Preservation Fund. © Renée Stout. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Stanley William Hayter. Centauresse, 1944. Engraving and softground etching with stencil inking, 6 × 4 in. (15.2 × 10.2 cm). The Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Purchase. © Estate of Stanley William Hayter/Licensed by Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York, NY. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Page 12

vaness german. i will never smile again, 2016. Mixed-media assemblage, 85 3/4 × 29 × 24 in. (217.8 × 73.7 × 61 cm). The Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Purchase, William G. Roehrick ‘34 Art Acquisition and Preservation Fund. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Page 14

Elihu Vedder. The Boy, 1902. 40 11/16 × 21 1/16 × 23 1/4 in. (103.3 × 53.5 × 59.1 cm) The Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Philip V. Rogers © 1902 by Elihu Vedder Asst by Charles Keck. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Vaness german. i will never smile again, 2016. Mixed-media assemblage, 85 3/4 × 29 × 24 in. (217.8 × 73.7 × 61 cm). The Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Purchase, William G. Roehrick ‘34 Art Acquisition and Preservation Fund. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. Water Carrier, c. 1913. Seravazza and Sicilian marble, 16 1/2 × 4 7/8 × 3 7/8 in. (41.9 × 12.4 × 9.8 cm). The Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of Elizabeth Pound, wife of Omar S. Pound, Class of 1951. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Ibrahim Said. Floating Vase 6, 2021. Earthenware, 20 3/4 × 10 1/2 × 9 1/2 in. (52.7 × 26.7 × 24.1 cm). The Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Purchase, William

36

G. Roehrick ’34 Art Acquisition and Preservation Fund. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Raven Chacon. For Zitkála Šá Series (For Olivia Shortt), 2020. Lithograph, 11 × 8 1/2 in. (27.9 × 21.6 cm). The Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Purchase, The Edward W. Root Class of 1905 Memorial Art Purchase Fund. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Drinking Cup

Unknown. Drinking cup, 325-300 BCE. Terracotta, 7 3/16 in. (18.3 cm) Rim (Diam.): 4 5/16 in. (11 cm) Base (Diam.): 2 1/16 in. (5.2 cm). The Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Bequest of Edward S. Burgess, Class of 1879, H1904. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

David Smith. Belial Figure, 1945. Bronze, 17 1/2 × 7 3/4 × 6 15/16 in. (44.5 × 19.7 × 17.6 cm). The Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of James Taylor Dunn, Class of 1936. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Albrecht Dürer. The Rhinoceros, 1515 (printed c. 1620). Woodcut, 8 11/16 × 11 7/8 in. (22.1 × 30.2 cm).The Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of Omar S. Pound, Class of 1951. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Unknown Artist. Bust of a woman wearing a polos, date unknown. Terracotta, 11 × 8 3/4 × 4 1/2 in. (27.9 × 22.2 × 11.4 cm). The Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Unknown Artist, Censer, c. 450-650 CE. Terracotta, 16 3/4 in. × 19 in. × 15 in. (42.5 × 48.3 × 38.1 cm). The Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Page 20

D’Souza, Aruna. “Shahzia Sikander’s Exquisite, Entangled Worlds.” The New York Times, 19 Aug. 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/19/arts/ design/sikander-morgan-miniature-manuscript. html

Page 21

Shahzia Sikander. Embark/Disembark IV, 2004. Offset lithograph and silkscreen, 18 × 15 in. (45.7 × 38.1 cm). The Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Purchase, William G. Roehrick ‘34 Art Acquisition and Preservation Fund. © Shahzia Sikander and The LeRoy Neiman Center for Print Studies. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Photo by John Bentham.

Page 32

Ann Agee. Green Dress Madonna with Clogs, 2021. Red earthenware with white slip and glaze, 27 1/2 × 13 × 8 1/2 in. (69.9 × 33 × 21.6 cm). The Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Purchase, William G. Roehrick ‘34 Art Acquisition and Preservation Fund. © Ann Agee. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

Carrie Mae Weems. Untitled (Woman and daughter with make-up), from the “Kitchen Table Series”, 1990 (printed 2010). Gelatin silver print, 9 15/16 × 9 7/8 in. (25.2 × 25.1 cm). The Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Purchase, William G. Roehrick ‘34 Art Acquisition and Preservation Fund. © Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Photo by Dave Revette.

Elizabeth Catlett. Madonna II, 1992. Screenprint, 21 3/16 × 15 1/16 in. (53.8 × 38.3 cm). The Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Purchase, The Wynant J. Williams ‘35 Art Collection Fund. © Catlett Mora Family Trust/ Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Photo by John Bentham.

Declan Haun. Woman giving bottle to infant, March on Washington, 1963. Gelatin silver print, 9 5/8 × 6 5/8 in. (24.4 × 16.8 cm). Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. Gift of Thomas J. Wilson and Jill M. Garling, P2016. © Estate of Declan Haun. Image courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY.

37

By Sae GleBa

By Sae GleBa

By SyDney piCColi

By SyDney piCColi

By miriam lerner

By miriam lerner

Green DreSS maDonna With CloGS

Green DreSS maDonna With CloGS