water

IN THE WEST

May Term Final Projects

HOW CAN WE CREATE AN EQUITABLE AND SUSTAINABLE RELATIONSHIP WITH WATER?

HOW CAN WE CREATE AN EQUITABLE AND SUSTAINABLE RELATIONSHIP WITH WATER?

May, 2023

AsweeddiedoutoftheGreen River,wehoppedontoamuddy river bank and began our short journey to find the Anasazidwellings.Thetrailto the dwellings was slowly fading, making the rough Tamarisk scrape against our legs, leading me to believe that this trail was not used often. Chris Carithers, our teacher, led us through this dry sandy terrain in a single fileline.Icouldfeelthehot

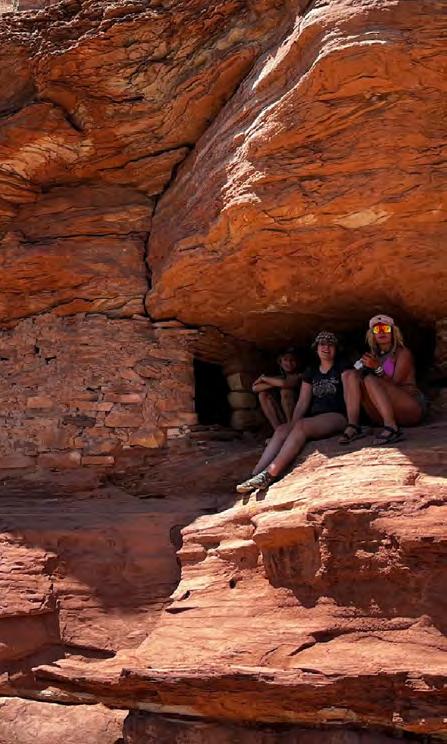

peoplewithinourlittlegroup, including myself, had to scramble back down the rocks to a place we had overlooked, andthere,hiddenbetweentwo rock ledges was an Anasazi dwelling. We rushed to glance at this small structure made with blocks of sandstone held together by mud mortar. Inside, the dwelling was dark with a smooth floor of loose sand. As I glanced up at this miraculousstructure,IknewI had to search for more. My mind yearned to learn more about what happened to the Anazasi,especiallybecausethe same disaster that destroyed them, now seems to be on the vergeofdestroyingus.

The Anasazi put extensive amounts of demand on an arid piece of land where, “"environmental resources weredecliningandpeoplewere livingincreasinglyclosetothe margin of what the environment could support” (Diamond,2005,P.156).This

sand continuously plunging into my shoes as it gave way beneath my feet, giving me the creeping feeling that spiders might find their way into my shoes. After walking for a little while, we found our way to a light red and sandy-colored rock formation. As we climbed up this rock formation we heard a shout coming from the end of our line, someone had seen an Anasazidwelling.Acoupleof

TheAnasaziwerebestknown for building spralling rock cities taller than any other city until the 1880s, when Chicago built skyscrapers (Diamond,2005,P.156).They also built a strong thriving community where they mastered architecture, made pots, and lived peacefully. However,thesepeacefulyears didnotlast.Theircivilization collapsed due to horrible things like drought, deforestation, and overpopulation. So, their society thrived and then abruptlydisappeared.

continued until the water was so sparse that the Anasazi could no longer cultivate the resources they needed to fuel theirsociety.Asscientistsand archeologists have looked into whathappenedtotheAnasazi, ithasbecomeabundantlyclear that creating thriving communities in the harsh environment of the American Southwest is immensely difficult. This is reflected in the problems currently facing theAmericanSouthwest.

and many more are prime examplesofcitiesthatarenot able to survive without assistance. Like the Anasazi, these cities have flourished within an environment that is notcapableofsustainingthem. Theyneedloadsofwatertobe imported to keep their cities running.Thishasprogressively become more and more of a problem, especially with the drought that started back in the early 2000s. The drought has continued to gnaw at the edgesofoursociety,whileour demand for water is rising, causing the water to decline, leaving us with fewer and fewer resources to survive. This could ultimately lead to the destruction of our civilization, just like what happened to the Anasazi. So, wecandecidetofightagainst thisdroughtanduseourwater sustainably, but this would take everyone working as a united force which is not somethingwehavebeenableto accomplishsofar.

This leads us to a question that Heather Hansman, the author of Down River, asked. The question was whether, “"human behavior is able to change before we have to resort to building new technologies to fix human mistakes” (Hansman, Personal communication, May 22, 2023).

Hansmanhasalsogivenusways tosolvesomeofourchallenges when it comes to water management.Thefirstsolution

she introduced was to change thewaythatwaterrightswork byputtinghumanneedsfirst.

Brad Udall, a climate scientist that Hansman interviewedsays,“"thatifhe could completely flatten the waterrightssystemandbuild it back up, he would put criticalhumanneedsfirst,the entireenvironmentsecond,and allotherusesinathirdtier. Forexample,you’renotgoing to grow alfalfa and not get water to Denver” (Hansman, 2019,p.194).Thisisimportant becauseifwedonotputhuman needs first our societies will start to crumble which would inturnmakenaturefallapart. Another solution that Hansman offeredwaslearningtomanage the basin as a connected systemthisway,“"watercould bemovedaroundtowhereit’s needed most” (Hansman, 2019, p.194).Thethirdsolutionthat HeatherHansmanprovidedwas finding a way to construct water management by conserving the water. She ascertainedthat,“"conserving canlooklikealotofdifferent things: water markets, leveling fields to maximize crop absorption, cutting energy use in cities, and finding ways to reduce reservoirevaporation,”areall things we should be doing to conserve our dwindling water supply(Hansman,2019,p.196). So, there are multiple ways that we can create a sustainableandevenequitable relationshipwithwater,butso far we have not been able to cometogetherasoneandfight forourfuture.

AsIcontinuedtoclimbthe

twisting path formed on this red sandy-colored rock formation,Isearchedformore Anasazi dwellings. I rounded thecornerhopingIwouldsee

an Anasazi dwelling. Sometimes,Iendedupspotting one and sometimes I did not, but every time I saw a little Anasazi dwelling tucked between a rock ledge, hidden from the outside world, I wouldbeoverjoyed.Ourwhole groupwouldagainrunrightup to the rectangular rock opening and look inside. We could have gone looking for Anasazidwellingsforhours

andhours.Inmyexcitement, Iroundedcorneraftercorner, ignorant of how far I had come. This made me wonder how many corners we were going to round until we start conserving our water and overallthenaturalworld.Will we get swept away by ignorance and not take action to save our dwindling water supply? Or will we stop rounding corners and start to fight for our water, our nature,andourworld?

"THE DROUGHT HAS CONTINUED TO GNAW AT THE EDGES OF OUR SOCIETY, WHILE OUR DEMAND FOR WATER IS RISING, CAUSING THE WATER TO DECLINE, LEAVING US WITH FEWER AND FEWER RESOURCES TO SURVIVE".PhotoofAnasaziDwellingtakenbyChrisCarithers PhotoofcanyonstakenbyChrisCarithers WildFlowersdrawnbyLillyGillespie PhotoofcanoesandsunsetbyChrisCarithers LELAH HERRINGTON

After getting out of our aluminum canoes on the Green River in search of ancient Anasazi granaries, wewereabouttoclimbanauburn,orangerockyslab to get to the next level of rock, when one of my classmates spotted the small structure. The granary was a small hut constructed using sandy colored rock slabs held together by thick dried mud built into the side of a shelf of rocks. As I looked at the ancient structure, my interest in the lives of the people who lived there before us grew. What problems did they have, and were they similar to ours?

The Anasazi, or Ancestral Puebloans, inhabited the Green river hundreds of years ago before disappearing. Jared Diamond, the writer of Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, stated that a drought was fatal to the Anasazi's disappearance,arguingthatbyusingdendro-

chronology, scientists can now see that the Chacoan population changed with the rain. Annual corn harvests, annual tree rings and soil studies provide information about the falling groundwater levels and extreme drought. While the Anasazi's collapse may have happened many years ago,weasWesternstatesmaybemaking the same mistake today. The fall of the Anasazi echoes some of the events in current society, such as how we have had seasonsofheavyrainfallandsnow,butare stillonthevergeofawatercrisis,“aseries of good years, with adequate rainfall or with sufficiently small groundwater tables, may result in population growth, resulting in turn in society becoming increasingly complex and interdependent and no longer locally self sufficient” (Diamond, 2005, p.143). Therefore, the Anasazi couldn't provide enough water and food for their population that was growing at a fast rate during good rain years. SimIlarly, our population in the Western states is still fast growing while our water supply is quicklydwindling.

Paddling down the maze of stone towers and beautiful rock walls on the Green, we saw few other groups completing the same voyage as us, most of them were olderandhadalovefortheriver.Goingto a place to better understand how it helps people care about it more, paddling down theGreendidthatforme.

BeingontheGreenRiverhelpedmeunderstand whythistopicissoimportantandwhyweneed toprotecttherivernotjustbecauseitwillcome back to bite us, but if we don't we will also be destroyinganecosystem.

Our trip was a recreational paddling trip, recreationalpaddlinghasbeenaroundsincethe mid 1950s and is an industry that generates around646billiondollarsyearly.Recreationisa businessthat,likemost,needswatertorunand it shows that not just farmers and cities need water. Recreational paddling is a great way for people to see the river that is giving all of the Western states their water and cultivate a desire to protect this precious resource (Hansmen, 2019, p126-150). While we paddled down the river, we passed cliffs of rock with swirling indents, and rock amphitheaters that echoed our voices back to us. As we moved further down the river, the walls of the canyon towered high above us like skyscrapers as the blisteringsunbeameddownonourskinburning it. As the long stretches of canyon progressed dark oranges and purples streaked across the rock.

It intrigues me that this massive river is providing water for seven states. It is a strong, mighty river, but if we can't properly distribute our water, the strong mighty river we see today will grow weak and disappear, repeating history as we know it. The bottom lineisthereisenoughwaterforallofusifwe reassess and everyone makes cuts. Not just one group, state or profession has to cut their water. We should see the basin as a wholeandlearnhowtoproperlymanagethe way that we are using our water. In the beginning, water allocations were based on false math and now we need to make the corrections. Our water can be conserved if we use it sustainably and divide it equally, locally, and statewide. While we need to improve the technology we are using to be more efficient in water usage, we more importantly need to improve how we are using our water now as a society (Hansmen, personalcommunication,May22,2023).

On the jet boat out of the river, I looked out at the water's chocolate brown color as it rushed swiftly past me. I learned to love this riverafterspendingeightdaysonit.Ilooked at the rocks shaped like sculptures in a museum, perfect and made by nature. This placehastobeprotected,Ithought.

The bottom line is there is enough water for all of us if we reassess and everyone makes cuts. Not just one group, state or profession has to cut their water.Sketches from the Canoe Day 8 by Lelah Herrington

We are running out of water. Sorry, let me rephrase that. We have the water, but we aremisusingit.WaterlevelsinLakeMeadhaverecentlybeenverylowbecausethere is not enough supply of water for the amount of demand that is coming with all the population growth in the West. Lake Mead’s water levels have been so low in the past twenty years that the two water pipes that are in Lake Mead that lead to Las Vegas were just below the surface of the water, so there was need for the construction of a third, bigger pipe that was constructed way deeper down in the lake. There was a question of if the pipe would be done before the water level went below the other two pipes. The project was called “The Third Straw” and was built twentyfeetbelowLakeMead’s‘Deadpool’anditwascompletedin2013.

It was the morning of day two. I had just woken up in my hammock. At first I was confused about where I was, looking up at the towering walls and layers of rock. To the left of me was the kitchen that my campmates and I had set up the day before. To the right, all my classmates and campmates were still resting in their sleeping bags, with the occasional head popping up in the morning light. Every day, I always wash my hands when I wake up. Although, on that day, I wasn’t sure if I should. We had a limited supply of water, with only fourteen water jugs, each holding seven gallons, to share over the span of eight days with ten others. It felt selfish to use up this limited water supply to wash my hands, which I had no real reason to do. I knew if I did my hands would get just as dirty at the end of the day. I decided against washingmyhandsthatmorning.

In order for this issue to be resolved, we have to change our human behavior before we fix anything else. We all have to work together. Realistically, I don’t think most people, if just told to save water, will do it. I have hopes that the government will add some sort of fine when people are overusing their water. A small fine, one that people wouldn’t be super mad at but also one that it is annoying to pay. I also think we should have this fine as a percentage of people’s salary, say 0.5%, which if someone’ssalaryis$50,000,thatwouldbea$250fine.

Some simple things you can do at home: Use less water washing hands, take shorter showers, don’t leave your faucet running for a while, use your dishwasher less, etc. Over my time on the river, whenever I washed my hands, I would open the water valve for a second, cup it in my hands, and wash my hands that way. I know that is a very extreme thing to do, but if our situation worsens,thatmightbewhatwehavetodo.

I made a connection between our situation on the trip and the situation happening with water in the West. We had limited water, in which I had two options. I could either ignore the fact that it was limited, splurge and wash my hands, or I could contribute to the cause and save the water. This is similar to the situation we have with water in the West. As Heather Hansman said, “It’s not that we don’t have enough water. It’s how we are using it” (Personal Communication, May 22, 2023). All of us are guilty of it - even if we don’t know it - of using too much water. I sometimes catch myself leaving the sink on while I'm brushing my teeth. I sometimes take showers for more than five minutes. I know it’s nice to take long showers, but that should be left as an occasional thing, not everyday.

‘Deadpool’ is not what you think. It is not your favorite Marvel Villain. ‘Deadpool’ is a term used to describe when the water level of a reservoir is so low that the water can no longer flow downstream. The current elevation of Lake Mead’s water from sea level is 1,050 feet as of January 8th, 2023. That's twenty-three feet lower than reported at the same point in 2022, and thirty-eight feet lower than levels reported at the same point in 2021. Lake Mead’s ‘deadpool’ is 895 feet. If we continue using our water like we are rightnow,wehavelessthansevenyearsuntilwereachLakeMead’s‘deadpool’.

In order for this issue to be resolved, we have to change our human behavior before we fix anything else. We all have to work together. Realistically, I don’t think most people, if justtoldtosavewater,willdoit.Ihavehopesthatthegovernmentwilladdsomesortof fine when people are overusing their water. A small fine, one that people wouldn’t be super mad at but also one that it is annoying to pay. I also think we should have this fine as a percentage of people’s salary, say 0.5%, which if someone’s salary is $50,000, thatwouldbea$250fine.

Photo Taken by Chris Carithers, 2023

Photo Taken by Chris Carithers, 2023

IF WE CONTINUE DOWN THIS PATH, WE MIGHT END UP JUST AS THE ANCESTRAL PUEBLOANS DID.

Photo Taken by Chris Carithers, 2023

Photo Taken by Chris Carithers, 2023

We paddled down the snaking riverwiththebirdschirpinginthe distance, and then finally eddied out where the brush separated. The canyons above us were glowing red, just like they had thousands of years ago. We tied up our boats, and started bushwackinguptowhatIlearned laterwasanAnasazigranary.The Anasazi, or the Ancestral Puebloans, were a group of people who lived in the Green Riverareafromaround600ce,to 1300 ce, when they mysteriously disappeared due to drought and other environmental factors (Diamond, 2005, 134). The drought that impacted the Anasazicouldverywellimpactus again. The Ancestral Puebloans were a thriving group of people untilthedroughthitthemin1275 (Diamond, 2005, p.135). The Anasazi relied on the river to survive, and most of their food source came agriculturally, for example,“The U.S. Southwest is a fragileandmarginalenvironment foragriculture-asisalsomuchof

It has low and unpredictable rainfall, quickly exhausted soils, and very low rates of forest regrowth” (Diamond 2005 p.137). This shows that without the river, the Anasazi were not able to grow crops, and feed their people.

Like the Anasazi, today we are facing a drought in the Southwest. We can either decide to keep using thewaterinthewaysthatwearecurrentlyandmake the problem worse, or we can change the ways we think and act around water to save it. Heather Hansman stated, “there is enough water to go around, it's the way we are using it that's the problem”(Hansman, personal communication, May 22, 2023). As people, we need to rethink the way we are using our water domestically, and agriculturally if wewanttostaylivingintheWest.

IntheWest,conditionscanchangeyear toyear,andwedon'tknowwhenwewill have a steady amount of rainfall and snow to sustain the river's flow each year. As humans, we become accustomed to a comfortable lifestyle lacking awareness of where our water is coming from, and wasting water. As previously stated by Hansman, there is enough water to go around, but it's the way we are managing it that is the problem.

The difficult but comforting part about the situation of water in the West is the fact that we are in control. We can choose the outcome of the water crisis. We can either choose to preserve the beautiful place that theAmericanSouthwestis,orwecanchoose toruntheriverdry,andfallliketheAnasazi.

As I hear the birds chirp, and the river run, I take a breath of the dry desert air, and hope that as people, we can learn to take care of this beautiful place. We stumble down the loose rocks from the Anasazi granary and get back into the metal boats that carry our livelihood on the river, and I say a silent prayer for the American Southwest.

THE

Inthebook, Collapse, byJaredDiamond, he explained that “we forget that conditions fluctuate, and we may not be able to anticipate when conditions will change. By that time, we may already have become attached to an expensive lifestyle, leaving an enforced diminished lifestyle, or bankruptcy as the sole outs” (Diamond, 2005, p.156). This shows that we can either choose to perish like the Anasazi,orwecanlearnhowtolivewith lesswater.

“Thereisenoughwaterto goaround,it'sthewaywe areusingitthat'sthe problem”

HEATHERHANSMAN

After traversing up the steep cliff for a while, we got to the top overlooking two sides of the river that looped around a large cliff. A long time ago, the river used to just turn right, but over time, the steep terrainblockedthewaterandmadeanew route.ItformedagiantUshape,andonce

yougottotheotherside,whichtookhours onasmallcanoe,itlookedlikeyouwerein the same spot. The view at the top was breathtaking. Sharp orange cliffs extended to the horizon where pillowy gray storm clouds were forming. We stayed up there for hours, tucked into small crevasses in the rock to hide from the wind, drawing, and writing. When we finally decided to hikedown,theweatherwasgoodforafew moments, until storm clouds came in. We had to gunnel up on the side of the Green tiedtoabigrock.

We stayed there for a little while, eating PB&Js wrapped in tortillas before the weather calmed down and we continued on.

We were always drawing. Almost every day, I drew something. Every day the landscapechanged,andtherewasalways somethingnewtodraw.Ontheninthday, wehadatwo-hourjetboatridealltheway

up the Colorado River back to Moab. I looked at the rocks and decided to open my sketchbook and draw. I had been drawingthingspreciselyasIsawthemthe wholetrip,andwantedtomakesomething moreofmyown.Itookinspirationfromthe rocks,butprimarilyIwasdrawingfrommy imagination. The boat droned on, and people were talking and yelling, but I foundawaytotuneitalloutandjustdraw forawhile.Idrewfantasticalrocksthatthe terrain around me had somehow inspired. The landscape had affected me. In Hansman’s book, Downriver, she talks about a raft guide who often stated, “We save what we love and we love what we know” (2019, p.150). I had come to know the Green River. I want to protect it so otherscanlearnfromittoo.

Throughout the trip, we occasionally saw small remains of Anasazi homes and towers, evidence of a civilization that mismanaged water and paid the ultimate price.Smallstoneigloo-typebuildingswith pieces of wood holding the entrances could hold up to two or three people uncomfortably. Why would they abandon their homes and go somewhere else? No one is entirely sure, but people have their guesses. Jared Diamond, the author of Collapse, believes they overused the water they had. They farmed too much duringthewetseasons,overworking

Thelandcouldnolongerprovideforthem, forcing them to leave. They used up all theirresourcesuntiltherewasnothingleft. Ifwearenotcareful,wewillendupinthe sameplace.Ifwecontinuetousewaterat the rate we are, our dams will reach Deadpool,whichiswhenthewaterlevelis so low that water can't pass through the dams. We need to learn to conserve water,andbuildasustainablerelationship withit,soitcancontinuetoprovideforus, foryearstocome.

Sharp orange, Wingate cliffs extended to the horizon where pillowy gray storm clouds were forming.

The question of how to have a more sustainable relationship with water is a tough question to confidently come up with a solid answer for. I think there are a few solutions that can help. Water banks are an effective way to conserve water. Of the 1.9 trillion gallons of water that the Colorado River basin provides annually, agriculture consumes 80%. Since agriculture is themainuseofwater,ifwetacklethisproblem,it will have the biggest impact. What a water bank does is it works just like a bank, but for water instead. People can put water rights in the bank whentheydon'tneeditandcangettheirincome fromthat.Farmerscanselltheirwatertobeused forotherthingsandcanmakemoneyfromthatif theydecidenottofarmthatyear.Theycouldput their water that normally would go to growing crops and feeding animals into a water bank, which would be a new source of income. If there was any water left over, or some wasn't used, putting it into a water bank would go back to the earth to be used again, and would give the farmerssomemoney.

Waterbanksare,“easytouse,profitable,yetan effective mechanism that enables transfers to both direct flow and stored agricultural water rights” (Heather, 2019, p.190). Things like water banksareagreatstepforward.Peoplecansave water and have reason to do so. It is very importantthatwecontinuetomakethesestepsin the right direction, which is something the Chacoansdidn'tdo.Backthen,theylivedwithout thinking about what the outcome could be. A lot of time has passed since then, and we have a betterunderstandingofwhatwillhappen.Itisour responsibility to make sure we can keep our water.

The tricky and most important part of conserving water is giving people an incentive. I think that this is the most important thing we can do in ordertochangeourrelationship with water. In order for things like the water bank to happen, people need incentives to do so.Nothingisgoingtochangeif no one cares. If we can incentivizepeopletocare,that's when things change. Getting peopletodosoisdifficult,andI don't have a solid answer. Therearelotsofdifferentways.

At the outside of a horseshoe bend in the river, we spotted an openinginthetamariskand eddiedout.Aftertyingup

ourcanoes,wehikedupafainttrailthat ledtothebaseofasandstonewall.Then wesawit:Asmallcavefifteenfeetabove usthatwasjustlargeenoughforasmall family. Flat, irregular stones, held together with a mud-like mortar, enclosedthe dwelling.I scamperedup a steep slab of rock in my sandals before carefullytraversingtowardstheopening. Juniper branches had been cut to frame the door, and over seven hundred years later, the rectangular entry was still intact. I turned upriver and saw a columnar structure across the wash that waswithinyellingdistance.Perhapsthey positioned a lookout there to watch for marauding enemies drifting downstream insearchoffoodduringtryingtimes.

The Anasazi, otherwise known as The Ancient Ones or the Ancenstral Puebloans, are responsible for constructing North America’s largest buildingsuntilChicago’sskyscraperswere erected in the 1880s. However, after managing to survive in the fragile environment of the desert Southwest for hundreds of years, this same group of people eventually ‘disappeared’ Archaeological evidence suggests that they abandoned the area between 11001300CE. Their story is one that is being repeated today as population growth, climatechangeandalackofconservation have all contributed to an uncertain future for people living in the American Southwest.

The Ancestral Puebloan’s story makes it clear that living in this arid region requires an understanding that water is scarce; therefore, when managing water tremendous foresight, cooperation and sacrificeisrequired.TheU.S.southwestis a fragile environment and a, “marginal environment for agriculture,” and as a result the Ancestral Puebloans had to experiment with dry land agriculture, planting close to the water table, and collecting water runoff in irrigation ditches (Diamond, 2011, p.137). As their population grew in places like Chaco Canyon,“itbecamedangerouslytempting toexpandagriculture,inwetdecadeswith favorablegrowingconditions,into

THEIR STORY IS ONE THAT IS BEING REPEATED TODAY AS POPULATION GROWTH, CLIMATE CHANGE AND A LACK OF CONSERVATION HAVE ALL CONTRIBUTED TO AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE FOR PEOPLE LIVING IN THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEST.

marginal areas with less reliable springs andgroundwater”(Diamond,2011,p.141). Inessence,theypushedthelimitsofwhat was possible and then paid a heavy price when their agriculture needs exceeded what the land could provide. Simultaneously, as the population increased, the demand for wood for building and heating needs expanded as well.

Archaeologists have been able to examine mouse excrement from middens to get a more clear view of how the environmental conditions changed during that time. Evidence suggests that, “middens date[ing] after A.D. 1000 lacked pinyon and juniper, showing that the woodland had then become completely destroyed” (Diamond, 2011, p.147). This date coincides with a big spurt in constructioninChacoCanyon,whichtook

place in 1029CE, the same decade when conditions were particularly wet. The rise and fall of their population matched a rise and fall in agriculture, which in turn matched a rise and fall in precipitation levels. In Collapse, Jared Diamond concludes his investigation into the disappearanceoftheAncestralPuebloans from this region arguing that the, “people came to be living increasingly close to the margin of what the environment could support,” but the, “proverbial last straw that broke the camel's back, was the droughtthatfinallypushedChacoansover theedge;adroughtthatasocietylivingat a lower population density could have survived”(Diamond,2011,p.156).

Five hundred years later, as Americans migratedwestinthelate1800s,theytoo

quickly became the key to survival in the West… because to grow anything substantialwestof,say,Kansas,youcan’t depend on rain” (2019, p.24). In the early 1900s as more and more dams were built and engineers were able to transport water from the Colorado River basin to faraway places like Los Angeles, modern enginuity allowed population densities in theWestthateventuallytaxedthecarrying capacity of the land. Today, “the unmitigated forces of growth and drought exacerbate the problem. The Colorado River Basin has been in what the Department of the Interior calls a 'historic extended drought' since 2000 and a good numberof the fastest-growingcitiesin the country,likeSaltLakeCity,dependonthe basin, and on the Green in particular” (Hansman,2019,p.32).

when it came to water, and one where changes in climate and an inability to adapt to changing times led to conditions that became so taxing that the Ancient Ones had to abandon the place they calledhomeforoverfivehundredyears.

In one hundred and fifty years we are approaching that same limit. As Hansman argues,"it'stimethatwefindnewwaysof thinking about living in this arid land, because the old ways will lead to our demise".

Afterreturningtoourcanoes,wepaddled back into the main current of the Green. Theserpentinenatureofthecanyonwalls and the river's course made it hard to knowwhatmightbearoundthenextbend, fortheriverandforus.

quickly came to realize that existence in the American Southwest is impossible without reliable access to water. They immediately surmised that rerouting and storing water, as well as eventually ‘securing’ access to it with legal rights were essential needs in the West. In her book,Downriver, Heather Hansman notes that,"Irrigationandaccesstowater

Today, California, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, Colorado and Wyoming are all scrambling to figure out what legislation needs to pass to ensure that no cities become cut off from the water they have come to rely on. Both Lake Powell and Lake Mead are literally drying up and approaching 'dead pool' where water levels will not be high enough to pump waterthroughtheturbines.Asaresult,we find ourselves in similar situation to the one that befell the Ancestral Puebloans, onewheredemandswellexceededsupply

They quickly surmised that they needed to find ways to reroute and store water, as well as eventually ‘securing’ access to it with legal rights.

JARED DIAMOND, THE AUTHOR OF COLLAPSE, ARGUES THAT THE ANASAZI CIVILIZATION, WHICH, “FLOURISHEDFROMABOUTA.D.600 FOR MORE THAN FIVE CENTURIES,” WAS ABANDONED DUE TO HUMAN IMPACT ON THE ENVIRONMENT, DROUGHT, OVER-POPULATION AND THE FACT THAT, “PEOPLE CAME TO BE LIVING INCREASINGLY CLOSE TO THE MARGIN OF WHAT THE ENVIRONMENT COULD SUPPORT”

(DIAMOND, 2005, P. 143, 156). THE CAUSEOFTHEANASAZICIVILIZATION COLLAPSE, WHICH WAS A MYSTERY FORYEARS,CANBEATTRIBUTEDTO, “THEMESOFHUMANIMPACTSONTHE ENVIRONMENT AND CLIMATE CHANGE, “WHERE THE SOCIETIES SLIPPED FASTER THAN EVER DUE TO DEFORESTATION AND AN UNSUSTAINABLE POPULATION THAT EXCEEDED WHAT THE LAND COULD PROVIDEFOR(DIAMOND,2005,P.137).

“WHATDOWEWANTOURFUTURETO LOOK LIKE?” HEATHER HANSMAN, THE AUTHOR OF DOWNRIVER, ASKS AT THE END OF HER BOOK (2019,P.204).THISQUESTIONLIESAT THEHEARTOFMANYMOMENTSTHAT WE EXPERIENCED ON THIS TRIP. DURINGMYSECONDTRIPDOWNTHE RIVER,THERIVERWASFULLANDTHE FLOWERS WERE IN BLOOM, WHICH GAVE ME A GLIMPSE INTO WHAT A HEALTHYWATERBASINCOULDLOOK LIKEIFWATERWASMANAGEDWELL. YET,WEARECAUSINGTHESEISSUES BYMISMANAGINGTHERIVERS.DOWE WANTTOBEPARTOFTHEISSUEOR PART OF THE SOLUTION, WORKING TO FIX WHAT WE HAVE ALREADY BROKEN.

THIS JOURNEY STARTED WHEN I WAS IN SEVENTH GRADE ON A RAFTING MAY TERM TRIP, WHERE THE SCENERY AROUND ME APPEARED TO BE DRY AND DEAD. THIS JOURNEY CONTINUED THREE YEARS LATER, AND I WAS ABLE TO RELOOK AT THE SAME SURROUNDINGS, THINKING TO MYSELF ABOUT HOW MUCH A PLACE CAN CHANGE IN SO LITTLE TIME. THE CHANGE CAME FROM THE DIFFERENCE IN THE HEIGHT OF THE WATER, THE COLOR ON THE CLIFFS, THE ABUNDANCE OF FLOWERS, ETC. THE COLORADO RIVER BASIN IS A VOLATILE PLACE WHERE IT’S HARD TO PREDICT HOW MUCHWATERWILLBEINTHESYSTEMINANY GIVEN YEAR. WHAT WE DO KNOW; HOWEVER, IS THAT REGARDLESS OF HOW ONE YEAR LOOKS, WE ARE STILL IN A TWENTYYEARDROUGHT.

WECAN'TCHANGE NATURE,BUTWECAN CHANGEOURSELVES,OUR CHOICES,ANDOUR DECISIONS.

LYDIAANDSASHALOD'SONRIVERWITHCHRISANDBIZWHENWELOOKBACKATTHEDISAPPEARANCE OF THE ANCESTRAL PUEBLOANS, WE CAN SEE THAT A MAJOR PART OF THEIR COLLAPSE WAS DROUGHT. SCIENTISTS STUDIED TREES TO MAKE ACCURATE DATA. THIS DATA SHOWS THAT “WIDE RINGS MEAN A WET PERIOD AND NARROW RINGS MEAN A DRY PERIOD”(DIAMOND,2005,P.139).

DENDROCHRONOLOGY WAS USED TO FIND OUT HOW OLD THESE DESTRUCTIVE DROUGHTSANDFLOODSWEREANDHOWTHE BIGDROUGHTCAUSEDDEFORESTATION.

TO CREATE A MORE SUSTAINABLE AND EQUITABLE RELATIONSHIP WITH WATER, I BELIEVETHATWECANCREATEABETTER,MORE THOUGHTFUL, RELATIONSHIP WITH WATER. WE CAN DO THIS BY LEARNING MORE ABOUT THE RIVER’SPASTANDITSPOSSIBLEFUTURE. WE CAN'T CHANGE NATURE, BUT WE CAN CHANGEOURSELVES,OURCHOICES,ANDOUR DECISIONS.WEARENOTTREATINGTHERIVERS HOWWESHOULD,ANDWENEEDTOFINDWAYS TOHELP.

DURING OUR 8 DAY RIVER TRIP WE VISITED THE STRUCTURES THAT THE ANCESTRALPUEBLOANSBUILTASWE LEARNED ABOUT THEIR LIFE WHEN THEY WERE HERE MANY YEARS AGO. THROUGH BUSHES AND BROKEN TREES WE MADE IT TO THESE STRUCTURESONTOPOFTHISCLIFF. THESE STRUCTURES MADE OUT OF ROCKS FORMED LITTLE CAVE HOUSES. THE FORMATIONS WERE PERFECTLYINTACTANDDIDN'TLOOK LIKE THEY WERE MADE THOUSANDS OF YEARS AGO. THEY RELIED ON WATERFROMRIVERSJUSTLIKEUS.

THE BEST WAY TO DO YOUR PART IS TO LEARN ABOUT THE RIVER AND HOW TO SAVE IT. BEING EDUCATED ABOUT IT WILL HELP YOU WANT TO SAVEIT.ILEARNEDTHATWEDEPEND ONWATER.IT’SEASYTOTAKEWATER FOR GRANTED, BUT NONE OF US WOULDBEHEREWITHOUTIT.

LYDIAANDSASHA PICKINGOUTCAMP

LYDIAPATTERSONARTPIECEONRIVER

LYDIAANDSASHA PICKINGOUTCAMP

LYDIAPATTERSONARTPIECEONRIVER

Swimming on a hot day, taken by Chris

FOR EXAMPLE IN HEATHER

HANSMAN’S BOOK, DOWN RIVER, SHE STATED THAT “AGRICULTURE USES ALMOST 90% OF THE WATER IN WYOMING…IF YOU WERE TO JUST CRUNCH THE NUMBERS, IT WOULDN’T MAKE A LOT OF SENSE TO ALLOCATE THAT MUCH TO RANCHERS AND FARMERS, BUT THOSE USERS HAVE THE OLDEST, MOST SENIOR WATER RIGHTS” (HANSMAN, 2019, PG.19).

Green River

THEREFORE, BECAUSE FARMERS AND RANCHERS HAVE PRIORITY THEY SHOULD BE DIRECTED TO USE WATER

SUSTAINABLY.

MORE

HANSMAN STATED THAT THERE IS ENOUGH WATER, HOWEVER WE ARE EITHER PUTTING TOO MUCH OF IT IN ONE AREA, OR ALLOCATING WATER TO A SOURCE THAT DOESN’T NEED IT (HANSMAN,

PERSONAL COMMUNICATION, MAY 22, 2023).

EITHER WAY, WE NEED TO BE SMARTER WITH OUR WATER USAGE AND ALLOCATION OR WE MIGHT END

THEREFORE, I WONDER, HOW CAN WE CREATE

SUSTAINABLE

A

UP LIKE THE ANASAZI. ONE OF THE WAYS THAT WE CAN HELP CONSERVE WATER IS THROUGH RANCHERS AND FARMERS. FARMERS AND RANCHERS CAN HELP PRESERVE WATER BY USING THE AMOUNT THAT THEY ARE ALLOCATING MORE SUSTAINABLY. WHEN WE WERE ON OUR WAY TO THE RIVER, I SPENT A MAJORITY OF THE TIME STARING OUT THE WINDOW. I WATCHED THE SUN GO ACROSS THE SKY AS THE DAY SLOWLY MOVED ON, OBSERVING THE MOUNTAINS SLOWLY DISAPPEARING AND THE WATER FROM THE GREEN RIVER GROWING LARGER. EACH TIME I WOULD SEE WATER, IT WOULD BECOME SLIGHTLY BIGGER, STRONGER, WIDER. IT MADE ME THINK WHY ARE WE IN A DROUGHT IF I CAN SEE ALL OF THIS FLOWING WATER. ACCORDING TO HEATHER HANSMAN, WE DO HAVE ENOUGH WATER, WE ARE JUST NOT USING IT IN A WAY THAT CAN HELP US PRESERVE OUR RESOURCES (HANSMAN, PERSONAL COMMUNICATION, MAY 22, 2023).

AND EQUITABLE

WITH WATER? THERE IS NO EASY ANSWER. SOLVING ONE PROBLEM IS NOT GOING TO SOLVE MUCH, WHAT WE HAVE TO DO IS SOLVE ALL THE PROBLEMS, OR AT LEAST ALL OF THE MAJOR ONES.

RELATIONSHIP

ON OUR TRIP ON THE GREEN RIVER, WE HIKED TO ONE OF THESE DEFENSIVE TOWERS THAT DIAMOND WAS REFERENCING.THE HIKE UP TO THE TOWER WAS BEAUTIFUL. WHILE WALKING UP THE ROCKY TERRAIN, YOU COULD SEE A VALLEY SURROUNDED BY CANYONS, IT WAS A SIGHT. THE TOWER WAS WHAT ANASAZI PEOPLE USED AS ONE OF THEIR RESOURCES TO PROTECT THEMSELVES. THE SOUTHWEST IS CURRENTLY IN A DROUGHT SIMILAR

TO THE ANASAZI. AFTER A LONG DAY OF CANOEING, IT FELT GOOD TO JUST SIT THERE IN MY CHAIR AND SIP ON MY HOT COCOA, WHILE STARING AT THE FIRE. I WAS THINKING BACK ON THE TOWER AND THE CURRENT DROUGHT FACING THE WEST, HOPING THAT HISTORY DOESN’T REPEAT ITSELF.

THE ANASAZI WERE AN ANCIENT NATIVEAMERICAN CULTURE THAT SPANNED THE PRESENT-DAY FOUR CORNER REGION OF THE US. THE BEGINNING OF THEIR COLLAPSE WAS DUE TO DEFORESTATION AND A DROUGHT, WHICH STARTED WARFARE. THE BEGINNING OF THEIR COLLAPSE WAS DUE TO DEFORESTATION AND A DROUGHT, WHICH STARTED WARFARE. IN JARED DIAMOND’S BOOK, COLLAPSE, HE DESCRIBED THAT, “WARFARE EVIDENTLY BECAME INTENSE, AS REFLECTED IN PROLIFERATION OF DEFENSIVE WALLS AND MOATS AND TOWERS, CLUSTERING OF SCATTERED SMALL HAMLETS INTO LARGER HILLTOP FORTRESSES”(DIAMOND, 2001, PG.151”).

DUE TO THE WARFARE, PEOPLE STARTED TO EAT EACH OTHER. THE CANNIBALISM TOOK TWO FORMS: EATING THE BODIES OF THE ENEMIES THAT HAD FALLEN FROM THE WAR, OR THE LESS APPETIZING ONE, EATING ONE'S OWN RELATIVE THAT WOULD HAVE DIED DUE TO NATURAL CAUSES.

" I WAS THINKING BACK ON THE TOWER AND THE CURRENT DROUGHT FACING THE WEST, HOPING THAT HISTORY DOESN'T REPEAT ITSELF "A painting of the Green River by River Miller

Contemplating and hoping that nothing bad will happen to civilization,photo taken by Chris Carit

Iplunged my paddle into the water churning mini whirlpools, spinning with force, propelling me slowly but steadily down the GreenRiver.It'sahotday,somy classmatesandIstrapourboats together and we float, as a unit, downriver.removemyshirt,the

sunbeatsdownonme,andtheheatoftherays blast my skin. I jump into the water and a cold rush pulsates through my body, rejuvenating, almost calming the rays of the yellow sun beatingdownonus.Ilookupattherocks,fullof minisculedetails,differentincolors,vastinsize, perfectfordrawing.

During the nights, I stare up at the stars, making up little dots in the sky, like bright lightsinthedarkness.Deepinthesecanyons, I feel protected from the outside world, disconnected from the clutches of technology andotheraspectsofdailylife.ThecalmnessI amexperiencing,nothavingtoworryaboutall the distractions in my life back home, made me feel like I am almost living in the past, possibly similar to the ancient tribes that inhabitedthisregionthousandsofyearsago.

Treerings,whichgrowwiderduringwetyears and narrower during drier years, can tell us varying amounts of rainfall, during drought yearsthetreeringswerenarrower.

Ancient tribes resided in these very canyons, right where I was canoeing. One of the tribes we studied located near the river was the Anasazi, while they had limited access to the Green River, the larger group, the Ancestral PeubloansdidhaveaccesstotheGreen.The Anasazi thrived for a period of time, as recalled in Jared Diamond’s Collapse, “a society numbering barely 4,000 people, and sustainedatitspeakforjustafewgenerations beforeabruptlydisappearing”(Diamond,2005, Pg 137). The Anasazi collapsed due to overpopulation problems that spilled into warfare and violence, but if we take a closer lookwecanseethattheproblemsweretiedto water.

All of the Anasazi’s methods of storing water werenotsustainable,one,forexample,wasto “occupyanareaforonlyafewdecades,until the area’s soil and game became exhausted, then move on to another area”(Diamond, 2005, Pg 141). However, this method only worked at low population densities and became impossible at high population densities, when people filled up the whole landscape and there was nowhere left to move(Diamond,2005,Pg141).Duetothefact that none of the subgroups of the Ancestral Puebloans could obtain water, they fell into disarray which spilled into warfare and cannibalism and ultimately caused their demise.

The problems that the Ancestral Puebloans faced are currently present in the Southwest. The Southwest has grown to such a large extent that they are having issues supporting the population and they cannot distribute and redistribute water evenly. Currently, the US Southwest is facing a dilemma, because it is unevenly populated, as stated in Downriver, “It’s [the Southwest] a divide between increasingly sparse rural populations and increasingly dense urban ones (...) water is being pumped to cities that can pay”(Hansman, 2019, Pg 42)

An idea she puts forth is separating states into natural hydraulic districts, such as watersheds, so that each user would know where their water was coming from and be more likely to conserve it. For example, Las Vegas has reduced its per capita water use by 36% from 2002 to 2017, due to the fact that homeowners get paid 2$ a square foot to get rid of their lawns (cite). In all, I think these are two vital solutions to managing waterintheSouthwestbecausepeoplewillknowwhere their water comes from, how much they have and will be less likely to overuse it. If citizens are getting paid to use less water in daily life, they are incentivized to not use too much water, these are important solutions that could be essential for preserving water in the future. As we eddy into camp, paddling with all our might, in sync, as a unit, we tie the ropes to a strong object, so the ships don’t float away. We get camp set up and boil water for dinner, the water bubbles as heat steams on the top. After dinner I look up at the night stars, calming in nature, and I hear the bubbling of the water, remindingmeofthefutureIwillhavewithwater.

The larger cities receiving water from the Green are taking massive amounts of water from their states allocated water rights, which is causing the sparselypopulatedareastodryup.“Insignificant” towns are being brushed aside for metropolitan areassuchasSaltLakeCityandDenver.Heather Hansman, the author of Downriver, says “Most of the water policy people I've talked to say that there’s enough water to go around; it just needs to be managed in smarter, more equitable ways”(Hansman,2019,Pg180).

"Insignificanttowns arebeingbrushedaside formetropolitanareas suchasSaltLakeCity andDenver"

On the morning of our fifth day on the Green River, I sat serenely in contrast with the anger of the storm the nightbefore.Wehadgottentocamplate.Aswestarted to set up tarps, the sky started leaking, and monstrous gusts caught us by surprise. Lightning inched its way towards us in bursts. We found ourselves in a tug-of-war with the wind. As we shoved the last stakes into the ground and crawled into the safety of our big green tarps,Irealizedhowharshandunpredictablethedesert can be. One moment your skin is aching with heat and blistering from the dry air, and the next the sky has opened up. Canyons flood, rivers jump their banks, and reservoirs fill, but less water is going through the water systems in the West now. We are parching ourselves of water by overusing more of it every year. Additionally, more people are living here than ever, more than water cansupport.

Water management isn’t a new thing. In Collapse, Jared Diamond introduces a new story, but an ancient one. The Ancestral Puebloans lived in many places in the West a millennium ago, including along the Green River. The book shows how an advanced civilization can underestimate the highs and lows of the land. For Ancestral Puebloan tribes, their dense population boomed in wet years, “when more rain meant more food” (Diamond, 2005, p. 148). After a drought struck, or even just as a result of a regularly dry Southwestern climate, the environment would no longer be able to keep up with the necessities of life for tribes like the Chacoans. Their strategy was diverting water into canals that could hold immense amounts of water. (Diamond, 2005, p. 145). These strategies were not designed with disaster in mind, and the fate of the Ancestral Puebloans was to succumbtotheharshWesternconditions.

Watercolor by Sasha Weiner

May 14, 2023

In the afternoon sun of May 15th, the seventh day of our journey, we passed stonestructuressecretlynestledinthe cliffs above. Around every bend, someone would spot a new ruin to wonder about. They could have been homes, storage, or used for something unknown. Regardless of the purpose, Ancestral Puebloan people stood right where we were, thousands of years ago. I would later wonder what drove these people to survive in this bleak, dry, but beautiful place. The answer wasrightatmyfingertips:water.Water has always been the driving force of survival.

Thetribeslivinginthisareahadtoughlives. Localforests’rateofregrowthwas,“tooslow to keep up with the rate of logging”, which meantlongjourneystoneighboringforests. At their high rate of population growth, furtherexpansionwasunsustainabledueto deforestation (Diamond, 2005, p. 147). Additionally, water was scarce and droughts struck frequently. For one tribe, Diamond even writes, “The proverbial last straw that broke the camel’s back, was the drought that finally pushed Chacoans over theedge,adroughtthatasocietylivingata lower population density could have survived”(Diamond,2005,p.156).

Many parallels to this ancient disaster are obvious when examining the current water crisis throughout the Colorado River basin and the seven states that have been strugglingtodividelimitedwaterrightsina way tolerable for cities, agriculture, and the river itself. These seven states would be experiencing only seasonal water flow, and floodingwouldbeuncontrolledifitweren’t for the extensive systems, like dams and reservoirs, that control every drop of water in the West. Like the Ancestral Puebloans, we are now experiencing a drought furtheredbyhighdemand.

The Ancestral Puebloan people had diverted water for their needs thousands of years ago, and the United States did the samething100yearsago.Whentheideaof dams was introduced, it was the obvious solutiontomanagingwater.Sincethedam building boom starting in 1902, 6,575 dams have been dotted across the United States. Thedamsystemsputinplacehereareonly trumpedbythoseofChina(Hansman,2019, p. 61). Dams make desert soil farmable and desert cities survivable. With them comes widespread access to water, but also many issues. They cost the United States millions of dollars and destroy surrounding ecosystems. Some fish species are not able to swim to their spawning beds, and dams are taking a real toll on biodiversity (Hansman,2019,p.123).

was right at my fingertips: water. Water has always been the driving force of survival.Sasha Weiner painting from a canoe Photos by Chris Carithers

Dams, and therefore cities, are running out of water. Over just the last few decades, populations in cities like Salt LakeCity,SantaFe,Denver,andPhoenix have soared. In these areas, “Homeowners…usesomuchmorewater on their landscaping in precisely the placeswherethatwaterislessavailable” (Fishman,2011,p.69).Thereissimplynot enough water to fulfill the exponential demands that the rate of population growth brings. This, combined with the decades-long drought we are experiencing, the supply is shrinking. Heather Hansman, the author of Downriver, says, “We do have enough water.”Shearguesthatwejustneedto allocate it correctly (Personal communication,May22nd,2023).

Thereisnoeasysolution,andnooneis the bad guy. Without water being diverted to agriculture, there would be no food to eat. Without dams, there would be floods and dry seasons. Without water for cities, there wouldn’t beanycities.Thebestsolutionwouldbe to incentivize cities and citizens to cut their water usage. This is already happening in places like Las Vegas, where citizens are being paid $3 per squarefootiftheyripouttheirlawnsand replace them with other landscaping. This‘cashforgrass’programhaspaida sum of $155 million dollars to residents (Fishman, 2011, p. 70). Incentives give people a way to make a conscious choice that they wouldn’t make themselves.

their water is a great way to lessen water usage, and it doesn’t run the riskofdecreasingfarmer’sincomeor frustrating residents, because they are getting paid. There are good people everywhere, but you need motivation to change your way of life.

Since getting off the river, I have felt that a part of me lies in sadness. The routine of the river is so constant and reliable. Within the layers of crimson cliffs and sifting through the mud at the river banks, I found a new perspective. I’ve found that being able toexperiencethisrivermotivatesmeto want to preserve it. Being in this place gavemethedesiretolearnhowtosave it. “We save what we love and we love whatweknow”(Hansman,2019,p.150). I know that if we can preserve these places through sustainable water usage, more people will have the privilege of experiencing the wonders that the Green River carries around everybend.

Anincentivedoesn’tjusthavetobefor your lawn. The government could incentivise not using all the water allocated to an individual with a water right. Another good step towards less waterusagewouldbetaxrebatesforless water used. If your electricity bill was below a certain amount, or you were a rancher conserving water, you’d get a partialreimbursement.Payingpeoplefor

Clouds at 12:26 PM

Watercolor by Sasha Weiner May 17, 2023

Cliffs + Camp Watercolor by Sasha Weiner May 16, 2023

Stranded in an Eddy Watercolor by Sasha Weiner May 11, 2023

Clouds at 12:26 PM

Watercolor by Sasha Weiner May 17, 2023

Cliffs + Camp Watercolor by Sasha Weiner May 16, 2023

Stranded in an Eddy Watercolor by Sasha Weiner May 11, 2023